The Paris Review's Blog, page 699

June 2, 2014

Keep on Pushing

We’re delighted to announce that two of our contributors have won Pushcart Prizes: Ottessa Moshfegh, for “The Weirdos,” a story from issue 206; and Susan Stewart for her poem “Pine,” from issue 207. Both pieces are available online, and both will appear this November in Pushcart Prize XXXIX: Best of the Small Presses, an anthology of this year’s winning writing.

We’re delighted to announce that two of our contributors have won Pushcart Prizes: Ottessa Moshfegh, for “The Weirdos,” a story from issue 206; and Susan Stewart for her poem “Pine,” from issue 207. Both pieces are available online, and both will appear this November in Pushcart Prize XXXIX: Best of the Small Presses, an anthology of this year’s winning writing.

Congratulations to Ottessa and Susan!

Reddy Kilowatt, and Other News

Image via Retronaut

Envisioning the brick-and-mortar bookstores of tomorrow: Wide steps double as seating and lead down to a bar and a stage, where a writer performs—‘authors will become more like rock stars’—or a ‘book wizard’ explains the craft of making books. The book you make might be one by the writer on stage, something you’ve written yourself, or any other text the robots conjure up.”

“I think poetry has really rather connived at its own irrelevance and that shouldn’t happen, because it’s the most delightful thing … We have lost the sense that poetry sits halfway between prose and music—that you can’t expect to read it like a novel. We are quite used to downloading an album and listening to certain tracks … poetry needs to be consumed in that way.”

On Tolkien’s 1926 translation of Beowulf, which was finally published last month: “The literary landscape has changed since then in a way that Tolkien would have neither expected nor accepted: he now towers in fame over Beowulf. Last year, Penguin repackaged its Michael Alexander translation as one of five ‘classic [stories] that inspired J R R Tolkien’s The Hobbit.’ but far more people will read the book for Tolkien’s sake than for Beowulf’s.”

“Though their obsolescence has been prophesied at various points, neighborhoods remain a vital—perhaps the most vital—way of thinking about the modern city.”

A 1959 promotional comic touts the glories of atomic energy through Reddy Kilowatt, everyone’s favorite grinningly electric asexual mascot: “I’m a real, live wire and I never tire. Yes, sir—I’m a red-hot shot. I can cook your meals, turn the factory wheels, ’cause I’m Reddy Kilowatt.”

May 30, 2014

What We’re Loving: Dallas, Dubai, Dublin

Three nights ago the eminent record collector Chris King came by The Paris Review loft to launch his new LP, Alexis Zoumbas: A Lament for Epirus 1926-1928. King arrived with several armfuls of 78s, including Greco-Albanian dirges, a Ukrainian wedding dance, and rare sides by Richard “Rabbit” Brown, Elvie Thomas, Amédée Ardoin, and others who have achieved a measure of posthumous renown on King’s label, Angry Mom Records. As a house present, King gave the Review eighteen test-pressings of the Carter Family (“from their most depressing period”), but the song I can’t get out of my head—thanks to our associate editor, Stephen Hiltner, who whistled the first few bars this morning—is “Chasin’ Rainbows,” by the Dallas String Band. Listen at your peril. —Lorin Stein

At a conference on web design earlier this month, Maciej Ceglowski gave a talk called “The Internet with a Human Face”—a cogent look at the bizarre double-lives the Internet forces us to live, the havoc it’s wrought on our concepts of privacy and identity. “A lot of what’s wrong with the Internet has to do with memory,” he says. “The Internet somehow contrives to remember too much and too little at the same time, and it maps poorly on our concepts of how memory should work.” Ceglowski runs pinboard.in, a bookmarking site—unlike too many in the Silicon Valley set, he’s entirely free of techno-utopianism, but he’s not an alarmist or a fatalist, either. Rather, he’s refreshingly clear-eyed about the state of technology and how we can improve it. “I’m tired of being scared of what the web is going to look like tomorrow,” he says. “I realized how long it had been since I looked at a new technology with wonder, instead of an automatic feeling of dread.” —Dan Piepenbring

Dubliners turns one hundred in June. “The Dead” is a masterpiece, of course, but I think the best of the stories is “Araby,” whose child protagonist experiences a kind of anti-revelation—one of the moments of adolescent wretchedness we all pass through to get to adulthood. The whole experience is conveyed in the twenty-four perfect words of the final sentence: “Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.” —Anna Heyward

When I think of Dubai, I think of excess: artificial land shaped like a palm tree, a certain Greenwich Village university cloned in downtown Abu Dhabi, and billion-dollar hotels. Reviewing Rowan Moore’s Why We Build in the New York Review of Books, Martin Filler writes, “In Dubai, the much-ballyhooed botanical symbol of a sheltering oasis gives way to a more mundane reality.” Filler describes his working relationship with the commanding architect Zaha Hadid, who has recently come under scrutiny for her lack of concern for the working conditions of the stadium she designed for the 2022 Qatar World Cup. Are such conditions an architect’s responsibility? More importantly, have we allowed architecture to reach a point where it’s beyond moral consequence? —Justin Alvarez

So many memories of play from my childhood are wrapped up in a hammock that hung between two tulip trees in the backyard: I think not just of the hammock itself, but of all its imagined possibilities—a roof, a raft, a lean-to, a cloud. It’s difficult to describe how this space serves as a cognitive landmark for me, but in 1958’s The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard beautifully articulates this nuanced relationship between space and self. Poetics is about the phenomenology of architecture. It explores intimate spaces in literature, using them to comment on the psychological impact of the places, particularly homes, that we inhabit. The book is full of charming, dreamy moments of insight; Bachelard describes how, in winter, the home becomes one’s whole world. “Snow, especially, reduces the exterior world to nothing rather too easily. It gives a single color to the entire universe which, with the one word, snow, is both expressed and nullified for those who have found shelter.” —Chantal McStay

If you’re nostalgic for Pemberley, try Amma Asante’s new film, Belle. Its heroine, Dido Elizabeth Belle, faces the moral dilemmas of courtship and marriage in an obtrusive social hierarchy. Here she echoes Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet, ushered into a tepid pool of aristocratic men—but unlike Austen’s heroines, Dido is a half-black woman. Belle details the politics of the time with a powerful awareness and insight—the role of women, class structure, and slavery are treated in equal measure, coupling these very real issues with a romance that would make Austen proud. —Yasmin Roshanian

Wiltshire Words

Longleat, Wiltshire: Morris's County Seats, 1880. From Volume II of The County Seats of the Noblemen and Gentlemen of Great Britain and Ireland, by Francis Orpen Morris.

In 1893, George Edward Dartnell and the Reverend Edward Hungerford Goddard published Glossary of Wiltshire Words—it is, as intuitive readers will have guessed, a glossary of words used in the county of Wiltshire. The “Folk-speech,” as the authors call it, is full of evocative terms, some of them familiar—jumble and caterpillar—and others entirely puzzling. (Evidence suggests that Wiltshire residents were often puzzled; they have about three dozen words for the condition.) The best entries tend to be common words with new definitions. Smart, for instance, used to mean “a second swarm of bees”; goggles was “a disease in sheep.”

Here are a few of the most novel words with annotations from the authors.

Ahmoo. A cow; used by mothers to children, as ‘Look at they pretty ahmoos a-comin’!’—S.W. (Som. bord.)

Afterclaps. Consequences, results. Atterclaps (S.).—N. & S.W.

All-a-hoh. All awry (A.B.C.H.Wr.); also All-a-huh. Unevenly balanced, lop-sided. A.S. awóh. ‘That load o’ carn be aal-a-hoh.’—N. & S.W.

Berry-moucher. (1) A truant. See Blackberry-moucher and Moucher (A.).—N. & S.W. (2) Fruit of Rubus fruticosus, L., Blackberry. See Moochers.—N.W. (Huish.) Originally applied to children who went mouching from school in blackberry season, and widely used in this sense, but at Huish—and occasionally elsewhere—virtually confined to the berries themselves: often corrupted into Penny-moucher or Perry-moucher by children. In English Plant Names Mochars, Glouc., and Mushes, Dev., are quoted as being similarly applied to the fruit, which is also known as Mooches in the Forest of Dean. See Hal., sub. Mich.

Birds’-wedding-day. St. Valentine’s Day.—S.W. (Bishopstone.)

Biver. To tremble, quiver, shiver as with a cold or fright (S.). Cp. A.S. bifian, to tremble.—N. & S.W.

‘Bless m’ zoul, if I dwon’t think our maester’s got the ager! How a hackers an bivers, to be zhure!’—Wilts Tales, p. 55.

Blow. Sheep and cattle ‘blow’ themselves, or get ‘blowed,’ from over-eating when turned out into very heavy grass or clover, the fermentation of which often kills them on the spot, their bodies becoming terribly inflated with wind. See the description of the ‘blasted’ flock, in Far from the Madding Crowd, ch. xxi.—N. & S.W.

Blue Cat. One who is suspected of being an incendiary. ‘He has the name of a blue cat.’ See Lewis’s Cat.—S.W. (Salisbury.)

Buddle. To suffocate in mud. ‘There! if he haven’t a bin an’ amwoast buddled hisel’ in thuck there ditch!’ Also used in Som.—N.W. (Malmesbury.)

Cag-mag. Bad or very inferior meat (S.).—N. & S.W.

Chinstey. n. The string of a baby’s cap.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.) A horse’s chin-strap.—S.W. Compare:—

‘Oh! Mo-ather! Her hath chuck’d me wi’ tha chingstey [caught me by the back-hair and choked me with the cap-string].’—The Exmoor Scolding, p. 17.

Crumplings, Crumplens. Small, imperfectly grown apples.—N. & S.W.

Daglet. An icicle (A.H.S.Wr.). See Daggled.—N. & S.W.

‘Thatched roofs are always hung with “daglets” in frost.’—Village Miners.

Dain. Noisome effluvia (A.B.C.H.Wr.). Formerly applied mainly to infectious effluvia, as ‘Now dwoan’t ‘ee gwo too nigh thuck there chap; he’ve a had the small-pox, and the dain be in his clothes still.’ (See Cunnington MS.). Now used of very bad smells in general.—N.W.

Dapster. *(1) A nimble boy.—S.W. (Deverill). (2) A proficient (S.). See Dab.—S.W.

Fashion. The farcey, a disease in horses (A.H.Wr.). Fr. farcin.—N.W.

‘An old Wiltshire farmer, when his grand-daughters appeared before him with any new piece of finery, would ask what it all meant. The girls would reply, “fashion, gran’váther!” when the old man would rejoin, “Ha! many a good horse has died o’ th’ fashion!”‘—Akerman.

Flowse. (1) v. act. You ‘flowse,’ or splash, the water over you in a bath.—N. & S.W. (2) v. neut. Water is said to be ‘flowsing down’ when rushing very strongly through a mill hatch. A horse likes to ‘flowse about’ in a pond.—S.W. (3) n. The rush of water through a hatch.—S.W. (4) n. Occasionally also applied to the narrow walled channel between the hatch gate and the pool below.—S.W.

Flucksey. adj. ‘A flucksey old hen,’ i.e. a hen who makes a great fuss over her chickens.—S.W. (Bishopstrow, &c.) Cope’s Hants Glossary has:—’Flucks, to peck in anger like a hen.’

Gaam. (1) v. To smear or bedaub with anything sticky. Gaamze (Village Miners). (2) n. A sticky mass of anything. See Gam.—N. & S.W. Many years ago, at a Yeomanry ball in a certain town in N. Wilts, the Mayor, who had done his duty manfully up to then, stopped short in the middle of a dance, and mopping his face vigorously, gasped out to his astonished partner, a lady of high position, ‘Well, I don’t know how you be, Marm, but I be ael of a gaam o’ zweat!’—N.W.

Garley-gut. A gluttonous person. Perhaps connected with gorle, to devour eagerly (see Halliwell).

‘“Let’s go to bed,” says Heavy-Head, “Let’s bide a bit,” says Sloth, “Put on the pot,” says Garley-gut, “We’ll sup afore we g’auf” [go off].’—Nursery Rhyme.

Glory-hole. A place for rubbish or odds and ends, as a housemaid’s cupboard, or a lumber room.—N.W.

Goggles. A disease in sheep (Agric. of Wilts, ch. xiv).—N.W. (Castle Eaton.)

Grammered in. Of dirt, so grained in, that it is almost impossible to wash it off. Grammered: Begrimed (H.).—N.W.

Hullocky! ‘Hullo! look here!’ exclamation denoting surprise, or calling attention to anything (S.). This is usually pronounced Hellucky, and is a contraction of ‘Here look ye!’ Also Yellucks.—N. & S.W.

Jiffle. At Bishopston, N. Wilts, an old bell-ringer was recently heard to accuse the younger men of having got into a regular ‘jiffle’ (? confusion) while ringing. We have not met with the word elsewhere, but Hal. and Wright have jiffle, to be restless, var. dial.

Long Eliza. A kind of long blue earthen jar, formerly often seen in cottages.—N.W. (Berks bord.)

‘The high black chimney-shelf was covered with crockery of a low type of beauty; pink and yellow china dogs shared their elevated station with “long Elizas” and squat female figures.’—Dark, ch. i.

Minty. Of cheese, full of mites (A.).—N.W.

Moonied up. Coddled and spoilt by injudicious bringing up. ‘Gells as be moonied up bean’t never no good.’—N. & S.W.

Pigeon-pair. When a woman has only two children, a boy and a girl, they are called a ‘pigeon pair.’—N. & S.W.

Nurly. Of soil: lying in lumps.—S.W. (Bratton.)

Parson. In carting dung about the fields, the heaps are shot down in lines, and are all of much the same size. Sometimes, however, the cart tips up a little too much, with the result that the whole cartload is shot out into a large heap. This is known as a ‘Parson.’—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Pissing-candle. The least candle in the pound, put in to make up the weight (Kennett’s Paroch. Antiq.). Cp. Norman French peiser, to weigh.—Obsolete.

Quanked. Overpowered by fatigue (A.). Compare Cank.

Rumple, v. To seduce. The full force of the word can only be given by futuere, as:—’He bin rumplin’ that wench o’ Bill’s again laas’ night.’—N.W.

Shitsack, or Shitzack. An oak-apple (H.Wr.). Oak-apple and leaf (S.).—N. & S.W.

Skimmenton, Skimmenton-riding. A serenade of rough music got up to express disapproval in cases of great scandal and immorality. The orthodox procedure in N. Wilts is as follows: the party assembles before the houses of the offenders, armed with tin pots and pans, and performs a serenade for three successive nights. Then after an interval of three nights the serenade is repeated for three more. Then another interval of the same duration and a third repetition of the rough music for three nights—nine nights in all. On the last night the effigies of the offenders are burnt. Housset is the same thing. The word and the custom have emigrated to America.—N.W.

Smart. A second swarm of bees.—N.W.

Spurl. To spread dung about the fields (S.). Also Spear, Spur, and Spurdle.—N. & S.W.

Taffety. Dainty in eating (S.).—S.W.

Tiddlin’ lamb. A lamb brought up by hand (A.). See Tiddle (1).—N.W.

Toad-stabber. A bad blunt knife (S.). Commonly used by boys about Clyffe Pypard.—N. & S.W.

Vamplets. Rude gaiters to defend the legs from wet (A.H.). Cf. Bams. Also used in the New Forest. See Cradock Nowell, ch. xviii, ‘Not come with me ... and you with your vamplets on, and all!’ where the word is applied to shooting gaiters.—N.W.

Zam-zodden. Long-heated over a slow fire, and so half spoilt. This and the last two words belong to Som. rather than Wilts. A.S. sām-soden, half boiled.—N.W. (Malmesbury.)

I’d Like to Make You Smile

When the poet William Meredith passed away seven years ago today, Poetry published the third and final stanza from his “Accidents of Birth” in memoriam:

When the poet William Meredith passed away seven years ago today, Poetry published the third and final stanza from his “Accidents of Birth” in memoriam:

But it’s not this random

life only, throwing its sensual

astonishments upside down on

the bloody membranes behind my eyeballs,

not just me being here again, old

needer, looking for someone to need,

but you, up from the clay yourself,

as luck would have it, and inching

over the same little segment of earth-

ball, in the same little eon, to

meet in a room, alive in our skins,

and the whole galaxy gaping there

and the centuries whining like gnats—

you, to teach me to see it, to see

it with you, and to offer somebody

uncomprehending, impudent thanks.

It was a beautiful move on the magazine’s part, taking Meredith’s wonder and gratitude for his beloved and letting those words refer to the poet himself. When the verse is turned to epitaph, it becomes Meredith who teaches us to see; his lucky appearance in the room of our lives demands that we bow our heads, or else lift up our eyes, and stammer what thanks we are able to articulate.

I met Meredith nine months before he passed away, at Bread Loaf’s annual writers’ conference, to which he’d been invited as a special guest and at which I was a student. He’d taught on the mountainside campus in the late fifties and sixties, first in the English program and then at the conference, and now he’d returned to read for us in their Little Theater, a long, skinny rectangle of a room, the walls white, the chairs wooden, the light—admitted through banks of mullioned glass doors to either side of the audience—everywhere. It was more like a chapel than a theater.

Meredith read only a few poems, supported at the podium by his partner, Richard Harteis. For the remainder of the event, he sat in the front row, audience to a tribute whose meaning no one could have missed, while Harteis, Michael Collier, and Thomas Sayers Ellis offered up anecdotes and praise and read their own selections of Meredith’s work. Here was a dying man, a man who was loved.

He’d come close to death before, decades earlier. In 1983, when Meredith was just sixty-four, he suffered a stroke that left him immobilized for two years, and after that still saddled with expressive aphasia, a condition that, in a cruel irony, impaired his ability to translate thoughts into speech and writing. Only slowly, by way of intensive therapy, did he work his way back to the land of language, speaking again and even, eventually, continuing to write poetry.

That day on the mountain, I’d never heard of William Meredith. Against my expectation—of nothing; I’m always expecting nothing—here was something like awakening: I sat up when he read; I leaned in. Now I was listening.

Despite his Pulitzer and his National Book Award and his Guggenheim Fellowship, despite the fact that his first collection, Love Letters from an Impossible Land, was selected for the Yale Younger Poets series, Meredith doesn’t seem to have sustained readers’ attention the way his contemporaries have—poets like Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Randall Jarrell, and Muriel Rukeyser, with whom Meredith was close and to whom he is frequently dedicating his verse.

Why? Meredith was mannerly at a moment when raving and confessionalism were at the fore. He found his voice in form; he spoke composedly. And there’s a modesty to the character of his poems that makes him, perhaps, hard to lionize. He’s too polite to be showy, too interested in the world outside to cast himself as the star of the show.

Here’s the first half of “Accidents of Birth”:

Spared by a car or airplane crash or

cured of malignancy, people look

around with new eyes at a newly

praiseworthy world, blinking eyes like these.

For I’ve been brought back again from the

fine silt, the mud where our atoms lie

down for long naps. And I’ve also been

pardoned miraculously for years

by the lava of chance which runs down

the world’s gullies, silting us back.

Here I am, brought back, set up, not yet

happened away.

There’s a lot of “looking around” in Meredith. In his 1983 interview with Edward Hirsch for The Paris Review—conducted, by chance, shortly before his stroke—Meredith characterizes poetry as “the engagement of a mystery that has forced itself to the point where you feel honor-bound to see this mystery with the brilliance of a vision. Not to solve it, but to see it.”

Life’s astonishments come hand in hand with its malignancies, he wants us to remember. Still, he isn’t interested in fetishizing misfortune. “It’s our style now that a poet is taken seriously in proportion to his tortures,” he tells Hirsch, “particularly if his tortures can be blamed on himself.”

But Meredith doesn’t want to wallow. He refuses to use the world’s suffering (or his own) as an excuse to ignore its abundant wonders. In the face of what troubles us, he wants us to look life in the eye, to make that near-impossible effort at speech. “Morale is what I think about all the time / now, what hopeful men and women can say and do,” he writes in “In Loving Memory of the Late Author of Dream Songs,” a poem that appears, along with “Accidents of Birth,” in his 1980 collection The Cheer.

In that book’s title poem, addressing the reader as his friend, he puts it more bluntly:

Frankly, I’d like to make you smile.

Words addressing evil won’t turn evil back

but they can give heart.

Giving heart, persuading us to smile, this is Meredith’s modest work. And this, I think, is what he means by “the cheer”: that which sustains us as we struggle toward our own articulations of anguish and awe and gratitude. “The cheer is hidden in right words,” he says. And, like finding the right words, it’s no easy panacea.

Toward the end of that Art of Poetry interview, referring to Roethke’s remark that “In spite of all the muck and welter, the dark, the dreck of these poems, I count myself among the happy poets,” Hirsch asks Meredith if he, too, counts himself among the happy.

Meredith replies, “I would like The Cheer to seem like someone who would say, ‘Yes. Without any reservations, I say yes.’”

Kate Brittain lives in Brooklyn. Her writing can be found at Vol. 1 Brooklyn and Tin House’s blog, The Open Bar.

By Conservative Estimate

Here’s a weekend recommendation for you—think of it as an extended Staff Pick, if you like.

Bill and Coo was made in 1948 to showcase “Burton’s Birds,” a troupe of trained lovebirds managed by former silent-movie actor George Burton. And does it ever! The tiny, Trucolor-hued town of Chirpendale is filled with bird characters of all kinds, doing all sorts of remarkable things: working in barber shops, wearing dunce caps, performing in circuses. In this idyll, we are told, “love, happiness and contentment blend together in harmony.” That is, until the Black Menace—a crow—descends and wreaks havoc. There’s romance (the eponymous Bill and Coo), adventure, song and dance. The film won a special Oscar. A New York Times critic deemed it “by conservative estimate, the God-damnedest thing I’ve ever seen.”

I adored Bill and Coo as a kid—we had a bootleg Betamax video of it—but I worried it wouldn’t hold up, or that as an adult I’d see signs of avian exploitation. (For the record, I’ve detected no indication of that, although maybe there’s an untold story that bears serious investigation.) I need not have—it is as weird, and as entertaining, as can be. A novelty, yes—but a wonderfully watchable one.

The whole film is readily available online—and you’ll be doing yourself a favor if you watch it from start to finish. But here’s a taste.

The Inner Beethoven, and Other News

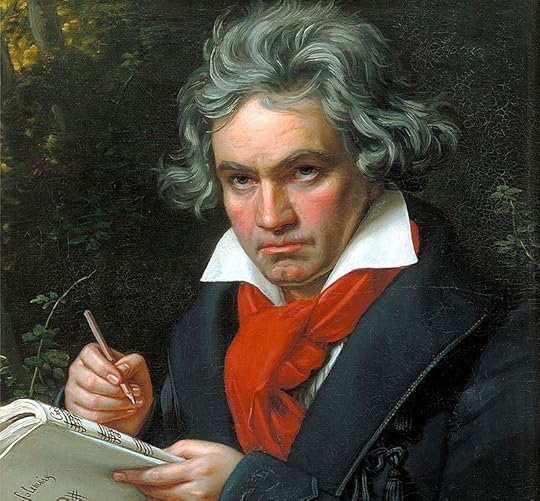

Under gastrointestinal duress. Joseph Karl Stieler’s portrait of Beethoven, c. 1819.

Discovered on the walls of Angkor Wat: more than two hundred hidden paintings.

An intimate new biography of Beethoven: “Suchet also presents ongoing reports regarding Beethoven’s gastrointestinal issues, which run through the book like an idée fixe. These begin with a description of the stomach pains and diarrhea that Beethoven experienced before his first concert at the Burgtheater in Vienna in 1794, followed by periodic updates on his irritable bowel syndrome, bad digestion, irregularity, acute constipation, colic, distended stomach, and more … one begins to wonder whether the book might have been more aptly titled The Inner Beethoven.”

On September 18, 1970, John Cassavetes, Peter Falk, and Ben Gazzara appeared on The Dick Cavett Show. They were all completely sozzled.

An attempt to categorize poetry in translation: “It seems impossible and so it is. But that is why we try, and every time we try we establish a small area of possibility. In fact if we are doing it well we are doing more than that: we are establishing an area of possibility that is itself a poem and the world is never poorer for a new good poem, which is like a new piece of knowledge of the world.”

Today in protein news: in praise of alpaca meat.

May 29, 2014

Poetry in Motion (and Digestion)

G. K. Chesterton in 1909. Photo: Ernest Herbert Mills

A happy birthday to G. K. Chesterton, born today in 1874. Chesterton’s 1908 novel, The Man Who Was Thursday, opens with a gem of a standoff between two rival poets. It’s a pungent, vitriolic affair, the best poet-on-poet action this side of The Savage Detectives, and in celebration of its author I reprint it here at length.

To set the scene: say you’re a hotshot poet at a garden party in Saffron Park, a suburb of London where your versification is known to be the best around. But wait—some other, new poet shows up, all cock-of-the-walk. Who’s this asshole? The two of you get to exchanging words, only to find that your worldviews are not just incompatible but riven, sundered, wholly opposed.

On the side of the anarchic and chaotic, there’s Mr. Lucian Gregory—“His dark red hair parted in the middle … and curved into the slow curls of a virgin in a pre-Raphaelite picture.” And defending all things orderly and punctilious, there’s Mr. Gabriel Syme, “a very mild-looking mortal, with a fair, pointed beard and faint, yellow hair.” The passage below finds them expounding, ardently and hilariously, on their respective poetics. For my money, Gregory has the more compelling argument, but Syme is the more masterful rhetorician.

Gregory resumed in high oratorical good humour. “An artist is identical with an anarchist,” he cried. “You might transpose the words anywhere. An anarchist is an artist. The man who throws a bomb is an artist, because he prefers a great moment to everything … The poet delights in disorder only … Why do all the clerks and navvies in the railway trains look so sad and tired, so very sad and tired? I will tell you. It is because they know that the train is going right. It is because they know that whatever place they have taken a ticket for that place they will reach. It is because after they have passed Sloane Square they know that the next station must be Victoria, and nothing but Victoria. Oh, their wild rapture! oh, their eyes like stars and their souls again in Eden, if the next station were unaccountably Baker Street!”

“It is you who are unpoetical,” replied the poet Syme. “If what you say of clerks is true, they can only be as prosaic as your poetry. The rare, strange thing is to hit the mark; the gross, obvious thing is to miss it … Chaos is dull; because in chaos the train might indeed go anywhere, to Baker Street or to Baghdad. But man is a magician, and his whole magic is in this, that he does say Victoria, and lo! it is Victoria. No, take your books of mere poetry and prose; let me read a time table, with tears of pride … every time a train comes in I feel that it has broken past batteries of besiegers, and that man has won a battle against chaos. You say contemptuously that when one has left Sloane Square one must come to Victoria. I say that one might do a thousand things instead, and that whenever I really come there I have the sense of hairbreadth escape. And when I hear the guard shout out the word ‘Victoria,’ it is not an unmeaning word. It is to me the cry of a herald announcing conquest. It is to me indeed ‘Victoria’; it is the victory of Adam.”

Gregory wagged his heavy, red head with a slow and sad smile.

“And even then,” he said, “we poets always ask the question, ‘And what is Victoria now that you have got there?’ You think Victoria is like the New Jerusalem. We know that the New Jerusalem will only be like Victoria. Yes, the poet will be discontented even in the streets of heaven. The poet is always in revolt.”

“There again,” said Syme irritably, “what is there poetical about being in revolt? You might as well say that it is poetical to be seasick. Being sick is a revolt. Both being sick and being rebellious may be the wholesome thing on certain desperate occasions; but I’m hanged if I can see why they are poetical. Revolt in the abstract is—revolting. It’s mere vomiting … It is things going right,” he cried, “that is poetical! Our digestions, for instance, going sacredly and silently right, that is the foundation of all poetry. Yes, the most poetical thing, more poetical than the flowers, more poetical than the stars—the most poetical thing in the world is not being sick.”

The Man Who Was Thursday is in the public domain.

Wizards of the Coast

John Dee and the occult in California.

Antonio de Pareda, The Knight’s Dream, 1655, Real Academia de San Fernando, Madrid.

Working summers at a Northern California health food co-op brings you into a constellation of eccentrics. The one that stands out in my memory, at a remove of more than a decade, is the old man who dressed as a wizard. His was not some flimsy Halloween affectation—it was a lifestyle, with accessories to match: thick robes of purple velvet stitched with golden stars, a silvery beard, and a hefty wand topped with a crescent moon. In our sole interaction that summer, he entered the co-op around closing and cornered me as I struggled to replace a roll of receipt paper. Peering out from under his pointed hat, he hit me with an intense stare and asked, “You ever done DMT, kid?”

Dimethyltryptamine, you might recall, is a highly potent, short-acting psychedelic alkaloid. It’s the stuff in the bitter Amazonian brew known as ayahuasca, and it’s the reason people lick the backs of Mexican toads to get high. The question surprised me at the time, but it shouldn’t have. Wizards have been asking questions like this for about four hundred years now.

Merlin has long occupied point position in pop culture as our archetypal sorcerer. But John Dee of England, born in 1527, the astrologer to Queen Elizabeth and advisor to Sir Walter Raleigh, was the true founder of the wizardly iconography and mythos. A skilled mathematician, geographer, and inventor, Dee also delved into grimoires, kabbalah, alchemy, and Biblical prophecy. He believed he’d been chosen by God to receive a new divine revelation—angels were sending him a new set of Biblical texts from heaven. And he had a sidekick: Dee believed the ultimate conduit was not himself but his servant, a mysterious ex-con named Edward Kelley, who spoke with the angels through a glass orb that the two called a “shew-stone,” or crystal ball.

Dee’s beliefs gained currency among notables including Sir Walter Raleigh and the poet Philip Sidney. Yet the Dee-Kelley enterprise ended badly, with professional failures and a surprisingly salacious personal dispute—Kelley claimed that the angels required the two men to keep everything “in common,” including Dee’s much younger wife, Jane, who was nonplussed by the idea. Kelley died young, dashing out his brains in a botched escape from a Czech castle where the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II had imprisoned him for claiming to transmute mercury into gold. But Dee and his mythos lived on, resurfacing throughout the seventeenth century in publications with such eye-catching titles as A True & Faithful Relation of what Passed for Many Yeers Between Dr. John Dee and Some Spirits; according to Frances Yates, Dee inspired the character of Prospero in The Tempest.

A portrait of Dee from the frontispiece engraving of A True & Faithful Relation of what Passed for Many Yeers Between Dr. John Dee and Some Spirits (1659), which portrayed Dee as a dangerous dabbler in dark arts and likened him to Muhammad and Paracelsus.

By the time, centuries later, that Umberto Eco had dramatized Dee’s saga from the perspective of a disgruntled Edward Kelley in Foucault’s Pendulum, a cottage industry had grown up around Dee and his angelic dialogues, which later followers would label “Enochian magic.” Today, initiates in Enochian magic can choose from dozens of magical guides, manuals, and websites; they can even listen to a book on tape sonorously dictated by a Los Angeles–based chiropractor, Jungian psychiatrist, and Aleister Crowley acolyte named Israel Regardie. “His way of pronouncing The Divine Names is at a vibratory level that one literally feels,” raves one initiate in a five-star Amazon review.

The Fairfax, California co-op where I worked as a teenager was a haven for this sort of thing, and I have no doubt that my wizardly interlocutor—the DMT guy—was a Dee fan of some kind. But the connection goes deeper than this. Dee was also, in an oblique way, a fan of California.

* * *

On September 10th, 1579, John Dee had a nightmare. He was naked, his entire body tattooed “with crosses blew and red” that recalled the pseudo-oriental textile patterns favored by Tudor nobles. The ominous Latin phrase sine me nihil potestis facere (“without me you can do nothing”) was inscribed on his right arm. And watching him with cautious, hooded eyes was Sir Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster and “the father of modern espionage,” as a recent history of invisible ink puts it.

It’s rare to have insight into the dreams of someone who lived four hundred years ago, but I’d wager that the unexpected appearance of Walsingham in Dee’s nightmare—chronicled in a diary entry about what he called “my dream of being naked”—has something to do with the search for a Northwest Passage. Virtually every navigator and statesman of any ambition sought this elusive quarry, from the era of Columbus to that of Commodore Parry; more than a few lost their lives in the attempt. Around the time of his naked dream, Dee, Walsingham, and Sir Walter Raleigh had discussed a proposed voyage in search of a northern passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific and, with it, a speedy route to China. Most seventeenth-century maps speculated that the mythical passage would exist somewhere southwest of Hudson Bay and north of the lands of New Spain. In other words: Northern California.

One map from the 1650s combined the “Island of California,” a famous cartographical error, with an imagined inland strait that would have carried mariners southwest from the icy north of Canada, through a Mer Glaciale (Icy Sea) and past the mythical cities of Cibola and what it called the Apaches Vaqueros (“cowboy Apaches”) of New Mexico. This hypothetical passage ends in the relatively balmy, sea otter–friendly waters off Point Reyes and Cape Mendocino, near Humboldt County.

Nicolas Sanson, “Amerique Septentrionale,” circa 1650. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The commercial advantages of such a route were obvious from the beginning, but for Dee, as usual, things ran deeper. He was searching not only for trade with China but for the ultimate alchemical object: the Philosopher’s Stone. In 1582, Dee speculated in his angelic diaries that the stone might be “hid in the secret of the depths, in the uttermost part” of the King of Spain’s dominions. The Pacific-facing lands stretching far to the west of British North America, Dee hoped, might shelter the Philosopher’s Stone as well as the Northwest Passage.

Dee never made it to California, nor did he really know it as a distinct geographical place—but that didn’t stop him from dreaming about it.

* * *

Three hundred years later, Aleister Crowley, the late Victorian mystic whom English newspapers labeled “the most evil man in the world,” was running a thriving global organization based on the magical beliefs of Dee and Kelley. Crowley repackaged Dee’s angelic dialogues and expanded them into what he called the Enochian system of magic. Most of his glosses are so cryptic as to be unreadable. “[Dee] symbolized the Fourth-Dimensional Universe in two dimensions as a square surrounded by 30 concentric circles (the 30 Aethyrs or Aires),” Crowley explains in a representative passage.

But Crowley’s magic was never about writing. It was about performance. His religious group, the Ordo Templi Orientis, offered up a beguiling mixture of bohemianism, eastern mysticism, and Catholic-inspired ceremony. And although the order began its life in the occult circles of Yatesian London, it found unexpected success in the palm-lined streets of Golden Age Hollywood.

In his engaging book Strange Angel, the journalist George Pendle excavates the back-stabbing office politics of the Southern California branch of Crowley’s occult organization during the thirties and forties. By World War II, a magnetically handsome Cal Tech rocket scientist named Jack Parsons had seized control of the Los Angeles–area branch of the Ordo Templi Orientis. Parsons’s Pasadena mansion became a center for a nascent brand of distinctively West Coast New Age mysticism, with stagy ceremonies involving sexualized versions of the Catholic Mass that often devolved into raucous, drink-fueled backyard parties. Parsons ultimately blew up both his house and himself in 1952, a casualty of his attempts to manufacture explosives for Hollywood films out of his garage.

Meanwhile, back in London, Crowley fumed in letters to friends that the Californians’ fascination with “sex magic” would give his magical system “the reputation of being that slimy abomination, ‘a love cult.’” He had a point. But in retrospect, Crowley should have been more worried about a red-haired new recruit fresh out of service in the Navy. “Although he has no formal training in Magick,” Parsons wrote excitedly to Crowley, “he has an extraordinary amount of experience and understanding in the field.” The man’s name was L. Ron Hubbard.

Today, the Church of Scientology—founded by Hubbard in the year that Parsons died, 1952—is famous, or infamous. The Ordo Templi Orientalis, by contrast, contents itself with a few outposts clustered around places like Los Angeles and Austin. Like Scientology, the O.T.O. offers would-be spiritual initiates a pre-charted pathway complete with cool-sounding rankings, from the beginner-level “Master Magician” to the more advanced “Prince of the Royal Secret” and “Epopt of the Illuminati.” But the esoteric orders that have followed in Dee’s wizardly footsteps seem content with life in the shadows. They practice but don’t publicize, occupying the blank spots and uncharted coasts of our cultural maps. They thrive in what Dee called “the secret of the depths.”

Benjamin Breen is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Texas at Austin and the editor-in-chief of The Appendix, a new journal of narrative and experimental history. His writings have appeared in Aeon, The Atlantic, The Public Domain Review, and The Journal of Early Modern History. He is currently writing a book on the origins of the global drug trade and is on Twitter.

Coaching, Portuguese Style

César Luis Menotti. Photo: Rob Bogaerts / Anefo, Nationaal Archief Fotocollectie Anefo

The coaches of the World Cup are more invested in the outcome of the match than almost anyone else on the planet. Players return to their league club between national-team matches—coaches don’t. They simply grit their teeth and bear the weight that comes with carrying an entire country’s sporting expectations on their shoulders.

“Your biggest question before you take the job is not, do you put them 4-4-2 or 4-2-3-1,” Slaven Bilic, the former coach of the Croatian national soccer team, said, referencing different soccer formations. “The biggest question is, can you cope with the pressure?”

One of the great World Cup coaches of all time was César Luis Menotti, the manager of the 1978 Argentina championship team. El Flaco, or the Thin One, as he was known, had a long flop of side-parted dark hair and thick sideburns, and he routinely used nicotine to help him cope with the pressure—he was rarely seen without a cigarette. It seemed to work, too. He may be the only person that Diego Maradona has ever referred to as God, other than Diego Maradona himself. Menotti’s reputation in later years became so great that he developed a group of followers known as Menottistas. And as with nearly all of the great coaches, his strategy possessed a blend of philosophy and artistry. He once said, with a lively spirit of abstraction, “A team above all is an idea.”

Argentina is one of three countries that have three different team managers working at this year’s World Cup. Italy is another. This is no surprise; both countries have long and illustrious soccer histories. Italy has won the World Cup four times, more than any other country except Brazil. Argentina is one of three other countries to have won it at least twice. (Germany and Uruguay are the others.)

It may seem odd, then, that the relatively tiny nation of Portugal, which has never finished higher than third, also has three coaches working this year: for Iran, the irascible and itinerant Carlos Queiroz, who has also coached the national teams of Portugal, South Africa, and the United Arab Emirates; for Greece, the stern-faced Fernando Santos, who has become a legend there, having been named the Greek league’s coach of the decade in 2010; and for Portugal, Paulo Bento, the former player who looks a bit like a platypus.

In part, the popularity of Portuguese coaches is due to what Luis Freitas Lobo, the Portuguese soccer television and radio analyst, calls “the José Mourinho effect.” In the last decade alone, Mourinho, who is fifty-one and currently coaches Chelsea, has won championships in Portugal, England, Italy, and Spain, as well as two Champions League titles. Because of his success, “the big clubs of the big countries look to the Portuguese coaches like never before,” Lobo said.

But Mourinho didn’t come out of nowhere. Over the last twenty-five years, Portugal has developed a school of coaching. “Mourinho is a symbol of this new era of coaches,” Lobo said. The “new era” spawned from the Technical University of Lisbon, where Mourinho studied, and the University of Porto, where a man named Victor Frade taught. Frade created the theory known as tactical periodization, which in practice, Lobo said, “never separates the physical, the tactical, the technical—the skills—and the mental in the work. Physical preparation doesn’t exist by itself for Portuguese coaches. It’s integrated with the tactical game. You don’t do any physical exercises without transferring them to the game.”

The theory seems well suited to the World Cup game, which, with its limitations on practice time and unrivaled worldwide attention, may be less about kicking a ball than any other professional soccer context anywhere. “Some of the guys from the university, like Mourinho, give a lot of importance to the psychological side of the game, the mental game,” said Hugo Daniel Sousa, who covered the 2010 World Cup for the Portuguese daily Publico, where he is currently online editor. “It is a much more wide approach.” To varying degrees, all three of the Portuguese World Cup coaches employ it.

Queiroz, the sixty-one-year-old Iran manager, was one of the first Portuguese coaches to come out of the universities, in his case in Lisbon, where these methods were taught. At the beginning of his career, he twice won the youth world championships, in 1989 and 1991, when coaching the Portuguese under-twenty team. “He achieved things that no one had ever achieved,” Lobo said. “The Portuguese people don’t forget that.”

Yet when Queiroz took over the national team in his next job, Portugal failed to qualify for the 1994 World Cup. Directly after the match that eliminated the team, Sousa said, “Queiroz said on TV, ‘The Portuguese national team needs to remove all the shit from the Portuguese federation.’ It’s a very famous sentence in Portugal.”

Queiroz, who was born in the former Portuguese colony of Mozambique, got a second chance to coach his nation’s team in 2010, but after getting eliminated by Spain, that experience didn’t end on a peaceful note, either. “He doesn’t have an easy personality,” Lobo said. “He’s not the coach who goes to the pitch to coach alone. He wants to be the boss. That creates animus.”

Greece’s coach, Santos, fifty-nine, had intended to retire from soccer after a short and minor career playing the game. He began to work at a hotel in the coastal region of Estoril, where friends persuaded him to coach the local team, and he hasn’t looked back since; during a stint with Porto in Portugal, he hired Victor Frade as an assistant. Unlike Queiroz, Santos has an easy personality. “Everyone in Portugal likes Fernando Santos,” Lobo said. When he speaks his mind, he does so through gentle rebuttals. Once, when asked why he didn’t coach his team to play more creatively and offensively, he famously said, “Should we keep fooling ourselves, mistaking sardines for lobsters?”

Bento took over the Portuguese team in 2010, after Queiroz’s fiery exit, and then led the team to the semifinals of Euro 2012. Unlike Mourinho and Queiroz, Bento didn’t study at the university, but at forty-four, he spent his playing career under its influences. “Right now in Portugal, there’s a conflict between coaches that are ex-players and coaches that come from the academies,” Lobo says. “Paulo Bento thinks like a player sometimes; he thinks like a coach sometimes. He is a compromise between the two worlds.”

Yet for all of the respect given Portuguese coaches recently, it might be asking too much for them to make their mark on this World Cup, when they’re coaching the likes of Iran, Greece, and even Portugal, who had to win a playoff match against Sweden to qualify. Only five countries have made it to the World Cup finals more than twice. The talent seems to be heavily and consistently concentrated in the same areas.

But who knows. Perhaps this is how a soccer legacy begins.

David Gendelman is research editor at Vanity Fair. Follow him on Twitter at @gendelmand.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers