The Paris Review's Blog, page 741

February 5, 2014

Lobster and Vodka Chez Burroughs

Meeting William Burroughs on his eightieth birthday.

Illustration: Christian Tonnis

I have this fairy godmother, a childhood friend of my mother’s who lives in Lawrence, Kansas. My mother and I call her up several times a year and she’s always turning me onto cool stuff. One day, when I was a senior in high school, it occurred to me to ask her,

“Do you know William S. Burroughs?”

“Oh, sure.”

I should emphasize that this moment came at the feverish height of a blind obsession I had with William Burroughs and everything Burroughs related.

“Personally?”

“Oh, sure.”

“You’re friends with him?”

“Well, we certainly know each other. He’s one of our local characters.”

“Do you see a lot of him?”

“I see him all the time, but mostly in the cat-food aisle of the supermarket.”

I went straight to my mother and demanded that we visit my godmother at the earliest opportunity. That summer, after I’d graduated high school and had had my wisdom teeth out, we went to Kansas.

My godmother made it clear that she had no intention of foisting me upon “the old man,” as she called him, but she did introduce me to one of his close friends, his editor at the time, who also declined to bring me to him, but was happy to tell me stories—such as how Burroughs’s most recent piece of writing had appeared to be utter gibberish until he realized he had to look at the typewriter key to the left of every character on the page, which ultimately revealed a rather mushy love poem to an octopus. (Toward the end of Burroughs’s life, cats, lemurs, and other non-humans were very much at the forefront of his thoughts.)

Although she didn’t feel comfortable trying to set up a meeting on my behalf, my godmother did show me which house was his. It is entirely against my nature to knock on anyone’s door without an express invitation, so instead, I walked back and forth in front of his gate with a collection of bird-call devices I’d found lying around in my godmother’s living room, hoping to coo him out of his domicile. (I imagine I believed this was an effective tactic after having read, in Hammer of the Gods, that a depressive Jeff Beck was lured out of his house and abducted for a concert by means of a bagpipe player in a diaper marching to and fro in front of his house.)

As the sun set, I thought I caught a glimpse of a pair of eyes peering through a bend in the blinds. But that was all I got.

* * *

A few months later, I was twiddling my thumbs in my college dorm room when a hallmate summoned me to the phone. It was my godmother.

“Guess what’s coming up,” she said.

I didn’t have to guess. It was to be his eminence’s eightieth birthday in February.

“I have these dear sweet friends with a wonderful bookstore that I just love to support. They’re organizing a reading celebrating the old man. If you could find a way to come out again and come read at that event, I’m pretty sure I can make sure you get to see him.”

So back I went to Kansas, brimming with anticipation. I was nervous about the reading, not possessing a very good voice of my own and not being very adept at public speaking. I made a sound collage of reel-to-reel tape manipulations and sampler loops of Ottoman military processions, Moroccan taqtuqa jebeliyya, Egyptian tarab, and Azeri art music; when I read my selections from Exterminator! and The Ticket that Exploded, I held a little Walkman with a speaker up to the mic and tried to balance the droning collage with my own delivery. There was a colorful roster of performers, from a local painter, Roger Shimomura, to the science-fiction-writing country singer Melvin Litton, to the two women who ran the store, who were very warm, wholesome types and struggled together with some perplexity through a selection from Naked Lunch.

Then, at last, Burroughs himself hobbled into the store. In the flesh! I was struck by how old and frail he looked. He had but the ghost of a wisp of hair left on his head. Feeling foolish, uncomfortably flushed, and hot, I introduced myself by name. “Glad to know you!” he said, somewhat impersonally. How was he doing? “As well as might be expected, after this operation I just had on my foot.” He hobbled onward, looked around, and left not long after. A little later, I was speaking with James Grauerholz, who laughed about Burroughs’s “operation”: “he had a corn removed the other day, but he loves to blow it out of proportion.”

After the reading, a mapcap turn of events ensued, culminating in a harrowing car chase. For all its genteel arts community and literary luminaries, Lawrence has its bloodthirsty fratboys. But that’s a story for another day.

* * *

The next day, my godmother’s friend came by early in the afternoon and we drove over to Burroughs’s place on Lenard Avenue together. (He actually had two places on Lenard Avenue, but this was his home; the other was for painting pictures and shooting them.) A small group of local men—a thoroughly charming good-old-boy intelligentsia—maintained a regular, perhaps daily, ritual of gathering at Burroughs’s house and whiling away the afternoon hours into the evening, drinking and smoking pot and talking about whatever. These men were all good friends of my godmother—local poets and writers, good-natured and mildly zany with a particularly tornado-alley perspective on things. We walked into the house and there sat Burroughs, in what looked like an oversize rawhide umbrella stroller. Sitting by him were his friend and editor I’d met on my previous visit, and another crony of theirs, a wacky plumber-raconteur-poet who remains a beloved figure about town.

I was warmly welcomed without ceremony and immediately fixed a vodka and coke. “You do all this stuff right?” the guy who had brought me over asked, referring to the alcohol and pot. Joint after joint was rolled and burned, and where at first I’d sat silent, starstruck, and unable to believe my good fortune, I was soon positively catatonic. The first time Burroughs addressed me directly, he rose out of his stroller, hobbled right over to me, leaned in, and closed the blinds. “The neighbors don’t like all this reefer madness,” he said with weary aplomb.

Four other guests came by over the next hour or two, most or all of them coming from out of town to pay their respects. One was a shaggy, bearded, cowboy-boot-wearing giant. The others seemed to be French—a pair of fashionably dressed, frizzy-haired men, one the younger companion of the other, and a lone traveler who would have fit effortlessly into an “interzone” milieu; he could’ve been found hanging around the docks at Marseille or something. “Weelyam,” he said, “the cops around here don’t seem so cool. I was smoking a joint in my car and just after I got stopped and I suddenly felt like frightened.”

Burroughs didn’t say much, except to provide an occasional annotation to one of the lively anecdotes going around: “No, I think that was down by your place that happened.” I hardly said a word. At one point the burly cowboy-boot guy interrupted a particularly preposterous story with a roar: “LET THE GUEST SPEAK!” Burroughs was startled: “What? What? What happened?” Everyone turned to stare at me, but I couldn’t think of a thing to say. I begged them to resume their stream of conviviality.

Later, Burroughs sipped my drink by mistake—unlike his, mine was less than three-quarters vodka. He choked and flailed until he regained composure. “This couldn’t be my drink!” he pronounced.

I gave him a present. It was The Wisdom of Idiots, a book by the sort-of pop “Sufi” author Idries Shah, which I had wrapped in shiny imitation-gold-leaf Egyptian hieroglyph paper.

I know precisely the sort of book I had wanted to give him. In today’s era of Internet shopping, I would have located an edition of Nicholson’s translation of Abo’l-Hassan ‘Ali bin Osman al-Jullabi al-Hujviri’s Kashf al-Mahjoub, an in-depth and marvelously entertaining exploration of medieval Islamic mysticism from a Khorasanian persepctive, but in the early nineties, book shopping in Philadelphia was an impoverished enterprise, and The Wisdom of Idiots was the best I could come up with. “I like the paper,” he said with genuine approval. He unwrapped it carefully. “Ah, idiot savants! A fascinating subject!” he exclaimed. I tried to explain to him the nature of these stories and what I knew of their cultural context. “Yes! … YES! … ” he said, “Idiot savants, know them well!”

He showed me a book he had laying nearby, a folio of photographs of tornado damage. We leafed through it together, riveted. “Can you imagine?” he said of a piece of hay that had penetrated a brick wall.

We went to his backyard, where I saw his frozen goldfish pond and his orgone accumulator. He broke the ice over the pond with his cane, in case the fish wanted to do any peeking or leaping, and I went into the orgone box for a fleeting eternity. Back inside, I told Burroughs that I had tried to read The Function of the Orgasm and hadn’t understood a word of it, and could he please break it down for me?

He composed himself. “Ahem, well, you see, Wilhelm Reich came to the realization, through extensive trial and error, that—oh! oh! oh my! Did you see that? That cat there! Froofy! He jumped from here”—he tapped the floor with his cane—“to there,” he said, gesturing to the kitchen counter. “Can you imagine a human who could jump six times the length of his body?” There were several instances where his train of thought was interrupted by such occurrences.

When we returned to the main salon—if I may call it such, since it was but a nondescript, wood-floored Midwestern living room—James Grauerholz had arrived with lobsters, ready to be served. He was slicing a baguette. Burroughs strode over in great distress. “You can’t cut anything with a knife like that!” he admonished—though it was a large, unquestionably sharp steak knife that Grauerholz was using. Burroughs hastily produced a machete, or something near enough, and insisted on wielding it against the baguette, gripping the handle with both hands and wincing as he thrust the fairly inconsiderable weight of his body into the operation.

Then he and I sat at a little lamp table and ate our lobster off the same plate, using the same nutcracker. This was a very special moment. I mean, for me.

After dinner, I called my godmother and asked for a ride. Burroughs became alarmed: “Is someone coming to this house?”

I told him I’d wait for her on the porch. When I’d been out there a few minutes, Burroughs put on his hat and came out and sat next to me, clutching his cane. I asked him if he liked Parliament and Funkadelic.

“Never heard of them.” It was chilly. “Where’s this grandmother of yours? Let’s go wait back inside.”

A few minutes later, my godmother came through the door, fanning a path for herself through the dense clouds of pot smoke. Burroughs looked up at her and his face brightened: “Bethie! What are you doing here?” Not only did he know her—he knew her cats. “How’s Scampers? And Frisky? And Wowsie?” I got up to greet her, wearing a feel-good smirk, and he said, “Oh this is your grandmother? Bethie, I didn’t know you had any grandchildren.”

I wish I had asked her to bring a camera. But now, whenever my overall credibility as a human being comes into question, I have only to reflect on my meeting with William Burroughs to remind myself that I belong to that world. It pains me to admit that one of my most memorable days was probably one of his most utterly forgettable, but my mind has surrendered some of the finer points, too. To this day, whenever I tell this story, I always have to improvise all the cats’ names.

George Mürer is a filmmaker specializing in the music of Kurdistan, Khorasan, and the Indian Ocean region. He lives in New York and is currently pursuing a PhD in ethnomusicology.

Lobster and Vodka at Chez Burroughs

Meeting William Burroughs on his eightieth birthday.

Illustration: Christian Tonnis

I have this fairy godmother, a childhood friend of my mother’s who lives in Lawrence, Kansas. My mother and I call her up several times a year and she’s always turning me onto cool stuff. One day, when I was a senior in high school, it occurred to me to ask her,

“Do you know William S. Burroughs?”

“Oh, sure.”

I should emphasize that this moment came at the feverish height of a blind obsession I had with William Burroughs and everything Burroughs related.

“Personally?”

“Oh, sure.”

“You’re friends with him?”

“Well, we certainly know each other. He’s one of our local characters.”

“Do you see a lot of him?”

“I see him all the time, but mostly in the cat-food aisle of the supermarket.”

I went straight to my mother and demanded that we visit my godmother at the earliest opportunity. That summer, after I’d graduated high school and had had my wisdom teeth out, we went to Kansas.

My godmother made it clear that she had no intention of foisting me upon “the old man,” as she called him, but she did introduce me to one of his close friends, his editor at the time, who also declined to bring me to him, but was happy to tell me stories—such as how Burroughs’s most recent piece of writing had appeared to be utter gibberish until he realized he had to look at the typewriter key to the left of every character on the page, which ultimately revealed a rather mushy love poem to an octopus. (Toward the end of Burroughs’s life, cats, lemurs, and other non-humans were very much at the forefront of his thoughts.)

Although she didn’t feel comfortable trying to set up a meeting on my behalf, my godmother did show me which house was his. It is entirely against my nature to knock on anyone’s door without an express invitation, so instead, I walked back and forth in front of his gate with a collection of bird-call devices I’d found lying around in my godmother’s living room, hoping to coo him out of his domicile. (I imagine I believed this was an effective tactic after having read, in Hammer of the Gods, that a depressive Jeff Beck was lured out of his house and abducted for a concert by means of a bagpipe player in a diaper marching to and fro in front of his house.)

As the sun set, I thought I caught a glimpse of a pair of eyes peering through a bend in the blinds. But that was all I got.

* * *

A few months later, I was twiddling my thumbs in my college dorm room when a hallmate summoned me to the phone. It was my godmother.

“Guess what’s coming up,” she said.

I didn’t have to guess. It was to be his eminence’s eightieth birthday in February.

“I have these dear sweet friends with a wonderful bookstore that I just love to support. They’re organizing a reading celebrating the old man. If you could find a way to come out again and come read at that event, I’m pretty sure I can make sure you get to see him.”

So back I went to Kansas, brimming with anticipation. I was nervous about the reading, not possessing a very good voice of my own and not being very adept at public speaking. I made a sound collage of reel-to-reel tape manipulations and sampler loops of Ottoman military processions, Moroccan taqtuqa jebeliyya, Egyptian tarab, and Azeri art music; when I read my selections from Exterminator! and The Ticket that Exploded, I held a little Walkman with a speaker up to the mic and tried to balance the droning collage with my own delivery. There was a colorful roster of performers, from a local painter, Roger Shimomura, to the science-fiction-writing country singer Melvin Litton, to the two women who ran the store, who were very warm, wholesome types and struggled together with some perplexity through a selection from Naked Lunch.

Then, at last, Burroughs himself hobbled into the store. In the flesh! I was struck by how old and frail he looked. He had but the ghost of a wisp of hair left on his head. Feeling foolish, uncomfortably flushed, and hot, I introduced myself by name. “Glad to know you!” he said, somewhat impersonally. How was he doing? “As well as might be expected, after this operation I just had on my foot.” He hobbled onward, looked around, and left not long after. A little later, I was speaking with James Grauerholz, who laughed about Burroughs’s “operation”: “he had a corn removed the other day, but he loves to blow it out of proportion.”

After the reading, a mapcap turn of events ensued, culminating in a harrowing car chase. For all its genteel arts community and literary luminaries, Lawrence has its bloodthirsty fratboys. But that’s a story for another day.

* * *

The next day, my godmother’s friend came by early in the afternoon and we drove over to Burroughs’s place on Lenard Avenue together. (He actually had two places on Lenard Avenue, but this was his home; the other was for painting pictures and shooting them.) A small group of local men—a thoroughly charming good-old-boy intelligentsia—maintained a regular, perhaps daily, ritual of gathering at Burroughs’s house and whiling away the afternoon hours into the evening, drinking and smoking pot and talking about whatever. These men were all good friends of my godmother—local poets and writers, good-natured and mildly zany with a particularly tornado-alley perspective on things. We walked into the house and there sat Burroughs, in what looked like an oversize rawhide umbrella stroller. Sitting by him were his friend and editor I’d met on my previous visit, and another crony of theirs, a wacky plumber-raconteur-poet who remains a beloved figure about town.

I was warmly welcomed without ceremony and immediately fixed a vodka and coke. “You do all this stuff right?” the guy who had brought me over asked, referring to the alcohol and pot. Joint after joint was rolled and burned, and where at first I’d sat silent, starstruck, and unable to believe my good fortune, I was soon positively catatonic. The first time Burroughs addressed me directly, he rose out of his stroller, hobbled right over to me, leaned in, and closed the blinds. “The neighbors don’t like all this reefer madness,” he said with weary aplomb.

Four other guests came by over the next hour or two, most or all of them coming from out of town to pay their respects. One was a shaggy, bearded, cowboy-boot-wearing giant. The others seemed to be French—a pair of fashionably dressed, frizzy-haired men, one the younger companion of the other, and a lone traveler who would have fit effortlessly into an “interzone” milieu; he could’ve been found hanging around the docks at Marseille or something. “Weelyam,” he said, “the cops around here don’t seem so cool. I was smoking a joint in my car and just after I got stopped and I suddenly felt like frightened.”

Burroughs didn’t say much, except to provide an occasional annotation to one of the lively anecdotes going around: “No, I think that was down by your place that happened.” I hardly said a word. At one point the burly cowboy-boot guy interrupted a particularly preposterous story with a roar: “LET THE GUEST SPEAK!” Burroughs was startled: “What? What? What happened?” Everyone turned to stare at me, but I couldn’t think of a thing to say. I begged them to resume their stream of conviviality.

Later, Burroughs sipped my drink by mistake—unlike his, mine was less than three-quarters vodka. He choked and flailed until he regained composure. “This couldn’t be my drink!” he pronounced.

I gave him a present. It was The Wisdom of Idiots, a book by the sort-of pop “Sufi” author Idries Shah, which I had wrapped in shiny imitation-gold-leaf Egyptian hieroglyph paper.

I know precisely the sort of book I had wanted to give him. In today’s era of Internet shopping, I would have located an edition of Nicholson’s translation of Abo’l-Hassan ‘Ali bin Osman al-Jullabi al-Hujviri’s Kashf al-Mahjoub, an in-depth and marvelously entertaining exploration of medieval Islamic mysticism from a Khorasanian persepctive, but in the early nineties, book shopping in Philadelphia was an impoverished enterprise, and The Wisdom of Idiots was the best I could come up with. “I like the paper,” he said with genuine approval. He unwrapped it carefully. “Ah, idiot savants! A fascinating subject!” he exclaimed. I tried to explain to him the nature of these stories and what I knew of their cultural context. “Yes! … YES! … ” he said, “Idiot savants, know them well!”

He showed me a book he had laying nearby, a folio of photographs of tornado damage. We leafed through it together, riveted. “Can you imagine?” he said of a piece of hay that had penetrated a brick wall.

We went to his backyard, where I saw his frozen goldfish pond and his orgone accumulator. He broke the ice over the pond with his cane, in case the fish wanted to do any peeking or leaping, and I went into the orgone box for a fleeting eternity. Back inside, I told Burroughs that I had tried to read The Function of the Orgasm and hadn’t understood a word of it, and could he please break it down for me?

He composed himself. “Ahem, well, you see, Wilhelm Reich came to the realization, through extensive trial and error, that—oh! oh! oh my! Did you see that? That cat there! Froofy! He jumped from here”—he tapped the floor with his cane—“to there,” he said, gesturing to the kitchen counter. “Can you imagine a human who could jump six times the length of his body?” There were several instances where his train of thought was interrupted by such occurrences.

When we returned to the main salon—if I may call it such, since it was but a nondescript, wood-floored Midwestern living room—James Grauerholz had arrived with lobsters, ready to be served. He was slicing a baguette. Burroughs strode over in great distress. “You can’t cut anything with a knife like that!” he admonished—though it was a large, unquestionably sharp steak knife that Grauerholz was using. Burroughs hastily produced a machete, or something near enough, and insisted on wielding it against the baguette, gripping the handle with both hands and wincing as he thrust the fairly inconsiderable weight of his body into the operation.

Then he and I sat at a little lamp table and ate our lobster off the same plate, using the same nutcracker. This was a very special moment. I mean, for me.

After dinner, I called my godmother and asked for a ride. Burroughs became alarmed: “Is someone coming to this house?”

I told him I’d wait for her on the porch. When I’d been out there a few minutes, Burroughs put on his hat and came out and sat next to me, clutching his cane. I asked him if he liked Parliament and Funkadelic.

“Never heard of them.” It was chilly. “Where’s this grandmother of yours? Let’s go wait back inside.”

A few minutes later, my godmother came through the door, fanning a path for herself through the dense clouds of pot smoke. Burroughs looked up at her and his face brightened: “Bethie! What are you doing here?” Not only did he know her—he knew her cats. “How’s Scampers? And Frisky? And Wowsie?” I got up to greet her, wearing a feel-good smirk, and he said, “Oh this is your grandmother? Bethie, I didn’t know you had any grandchildren.”

I wish I had asked her to bring a camera. But now, whenever my overall credibility as a human being comes into question, I have only to reflect on my meeting with William Burroughs to remind myself that I belong to that world. It pains me to admit that one of my most memorable days was probably one of his most utterly forgettable, but my mind has surrendered some of the finer points, too. To this day, whenever I tell this story, I always have to improvise all the cats’ names.

George Mürer is a filmmaker specializing in the music of Kurdistan, Khorasan, and the Indian Ocean region. He lives in New York and is currently pursuing a PhD in ethnomusicology.

A Downward Glissando

Photo: Cory Doctorow, via Flickr

Fat little dog trotting contentedly along the sidewalk, right at his master’s side, with a plastic steak in his mouth.

Neil Young sounds like a lonely alley cat, I thought, most poignant when slightly out of tune.

Whenever I got on the subway, I looked around for someone cute to glance at, and if there wasn’t anyone I resigned myself to boredom.

Old queen in the locker room: “When you’re the prettiest one in the steam room, it’s time to go home.”

At forty-three I was no longer in my heyday.

The name of the medication printed in a half circle and the “100 mg” made a smiley face on my new, blue pills.

On the L train, a poem called “Hunger” spoke of walking home “through a forest that covers the world.”

I’d had the same part-time public-relations job since November 1985. It was now February 2001 and counting.

I was drawn to Neil Young not by the specific content of the lyrics (too hetero) but by the overall tone of longing, which I defined as a kind of sadness that had hope.

On the L platform, a diminutive Chinese man playing “Send in the Clowns” on a harmonica, with flowery recorded accompaniment.

I write this in the hope that aphorism-like statements, when added one to another, might accrue to make some larger statement that will placate despair.

“The intensity of certain random experiences,” I wrote in my journal, “is sometimes unaccountable and makes one wish to live more observantly.”

I’d hoped to overcome negative thinking through therapy, meditation, prayer, swimming, and yoga, but now it appeared I also needed a drug.

According to WebMD, Wellbutrin carries a risk of seizure.

Thought: the problem with polyester is that it pills, yet sometimes it doesn’t, and you can never tell which it will be.

After eight years together, John and I still didn’t share an apartment, and I wondered if this was a failure.

Let the seizure come, I thought, and maybe afterward I’ll have some peace.

I supported myself mostly with public-relations writing and only sometimes with journalism, because public-relations writing is always positive, and I like to be nice.

In his spare time, my ophthalmologist is an amateur magician.

I went to look at the sunset and was given a ticket for trespassing.

My arthritis was bad that week, but I hoped that if I thought of myself as a well person rather than a sick one, the pain would bother me less and less and might even go away.

“Colors were brighter,” said a woman of her first week on Effexor, which I had also tried but didn’t like.

My Walkman in my breast pocket, I floated along with the sad tune.

The ronroco, a small Argentine string instrument, sounds like a cross between a ukulele and a mandolin.

In an e-mail regarding the freelance article I was working on, the marketing executive at Jordache tried to flirt with me by offering vintage jeans and asking my waist size.

Journal: “I like Internet porn too much.”

John and I enjoyed how Mae West makes odd, inarticulate, knowing “humph” sounds, sometimes barely audible, and how, when she “dances,” she barely moves.

I wrote that the old 1979 Jordache commercial, which was being shown again on TV, “begins with a downward glissando,” a line my editor took out, even though that glissando is my favorite part of the ad.

Joni Mitchell once wisely observed that disco music “sounds like typewriters.”

My editor also cut: “We only glimpse the blonde girl dancing, in a manner not seen since, say, the New York City Gay Pride Parade in 1989, that is, as if her shoulders are attached to one circular track and her hips to another.”

I noticed that whenever I trimmed my sideburns, I thought of a particular editor I barely knew, and since I liked her, I didn’t mind thinking of her while shaving, but sometimes I asked myself, Why her?

For another article, I spent my day off in Staten Island interviewing once again the teenager with HIV I had interviewed two and a half years earlier.

Noelle, my therapist of twelve years, almost started crying as she spoke of another patient, a priest, who had died of AIDS.

I went in search of a black version of the navy-blue, cotton-polyester shirt I’d seen at Bloomingdale’s, and I found it at Saks.

Though my brother had died of AIDS and we had discussed this many times, I had never seen Noelle cry before.

As soon as I switched from Effexor to Wellbutrin, my orgasm returned.

“The colors of some moments are slightly brighter than others,” I wrote, “and some a lot brighter, and at the moment I’m interested in those just slightly brighter.”

I told John how much I love blood oranges.

I went home and tried on all my new clothes.

John said I’m like that dog with his plastic steak when I have a new shirt to wear.

Articles I might have written for GQ: “Searching for the Perfect Black Polo Shirt”; “Shoe Shopping with My Podiatrist”; “How Can You Tell If a Particular Polyester Blend Will Pill”; “Why Do Certain Flat-Front Pants Wrinkle So Much in the Crotch?”

I was thinking of leaving Noelle and even went to see three new candidates but decided I would just reach the same point with a new one eventually, for reasons that are officially known as “resistance” and “transference,” and which in practical terms meant I was afraid to go forward.

My mother and father liked to playfully call milk “malk” and cooking “coo-king.”

Similarly, John and I repeat the same phrases again and again, phrases from movies or life that made us laugh, as when John overheard a fag in a coffee shop say, apparently of his boyfriend, “I don’t know where she is, I don’t know if she’s got a dick in her mouth …”

Thought: when you feel a strong connection to your therapist, you not only mistake her for your mother, but she sort of really is your mother, because she has taught you as much as a mother would.

In an e-mail, my friend Cathy, who is legally blind, explained to me for the first time in our twenty-two-year friendship exactly what she sees—that is, a rapid series of blurry snapshots because her eyes won’t hold still.

I begged off having a drink with my boss, saying I had dinner plans, which was true: I had planned to have dinner with myself.

I said I couldn’t have lunch with the salespeople tomorrow because there was something I had to do, which was true: I had to be alone.

Things I liked to do on Wellbutrin: blow my boyfriend; lie in bed switching channels; write one-sentence paragraphs; not get mad at store clerks; masturbate; read stereo-equipment catalogues; plan to go to Rome.

Soaked through after walking only half a block, I said to myself, This weather is absurd. Absurd!

I was discouraged to discover that certain childhood experiences continued to wreck my life, and so I had to look at them one more time.

Subway graffiti: “Admit when your gay and a slacker.”

For five years I’d been writing a novel about my teddy bear, in part because I was (and am) perpetually in need of comfort.

Driving me back to the ferry, the grandmother of the kid with HIV said wryly, as we passed the hospital, “There it is, our home away from home.”

When Noelle nearly cried, I said that maybe she was too fragile to be my therapist, but she replied that that wasn’t the case.

On the telephone John and I tried to imitate Mae West’s inarticulate humphs, but since they’re nearly inaudible, we didn’t have much success.

When I took my trespassing ticket to 346 Broadway, they said I had come on the wrong day.

In Union Square station, a teen to a fellow teen: “You sound like a fucking hibernating bear. Maybe you should sleep six months and shit.”

“Moments of a certain off flavor add up,” I wrote,” “and then you perceive you’re in a new phase of your life.”

In my teddy-bear novel I would have to write about shitting my pants all the time when I was five, and I wasn’t sure how to go about describing that.

After eight years, I related to John very well within certain parameters, and we were working to expand those parameters, but sometimes I was afraid I wasn’t up to the challenge.

His nickname for me: Kid. My nickname for him: Kid.

My dentist pointed to a small dark area on the X-ray.

On the phone John read me a funny article about Kathy Lee Gifford.

“There are certain moments and facts the mind returns to, for whatever reason,” I wrote.

I stared out my office window.

There was nothing more to be done for the tooth, so I would have to have it pulled, and it would have to be done now, before I went to Rome.

Young subway cop, tubby and all in blue, standing by the token booth vigorously chewing his nails.

Thought: Didn’t Dante refer to middle age as a “forest?”

* * *

“You may hear a cracking sound,” said the oral surgeon, who was also named Cliff. He was inserting a pair of pliers in my mouth. I heard the cracking. Occasionally life plunges you into an experience that, for its utter intensity and obscure resonance, may as well be a dream. “You doin’ okay?” Cliff asked. “Uh-huh,” I tried to say, though actually even after the five or six shots of Novocain I still had some sensation in one spot on my gum, but this was too difficult to explain. My mouth was propped open by a black plastic brace, which I bit down on with my left teeth, the side he wasn’t working on. Cliff said, “You’re going to feel some vibration.” I glimpsed the instrument before it went in. I wondered if he wished I’d opted for the Valium or Demerol, so that he wouldn’t have to explain everything he was doing. He was, however, very good at explaining. I felt that high-pitched vibration of the power tool (drill? tiny saw?). Then the tugging of the pliers, as the gray-haired German-accented assistant gently but firmly—Germanly, I thought—held my chin in place. More tugging. This went on for a while, the power tool, then the pliers, first one root, then the other. I kept my eyes closed and the light on my eyelids was bright as daylight. I tried to imagine I was at the beach. Again and again my shoulders tensed up and I would have to remember to relax them. To describe this ordeal as primal might be misleading, since I was too deep in the woods of it to describe it to myself at all. If I were to interpret, I might say it confirmed a nameless and fundamental conviction that life had stolen something nameless and fundamental from me. This might also be called the human condition, but like the protagonist in a dream I was exempt, for the time being, from drawing any such conclusions. At last there was a final tug, which, though I could see nothing, seemed decisive and was. He dropped the pliers in the metal tray with a clang.

* * *

Just as I switched the channel to Jenny Jones, she said, “So, you have sex for money. And you work at White Castle?”

Mouth full of gauze, I had to stop by the office because the goddamn FedEx package hadn’t arrived the day before.

On the subway stairs: “If I hear any more about your anger management class, I’m going to throw up.”

I read that a fever after a tooth extraction is normal.

I began seeing flashing lights on the periphery of my left eye, so I called my magician-ophthalmologist, who told me I had Moore’s Lightning Streaks, a harmless condition that can affect nearsighted people in middle age.

Apparently Barbara Stanwyck once said “Fuck you” to Loretta Young.

I tried to participate in my oral surgeon’s manful matter-of-factness, but I still mourned the molar, designated “number 30.”

I broke down when Noelle said she felt outrage for certain things I had suffered as a child.

Cliff had also been my oral surgeon more than fifteen years earlier, on this very same tooth, which that time was saved, and that time I did choose the Valium and Demerol—

“Cliff … Cliff … Cliff …? Howyadoin’?”

This essay is excerpted from The Tooth Fairy: Parents, Lovers, and Other Wayward Deities, which will be published tomorrow. Copyright © 2014 Clifford Chase. Published by The Overlook Press. All rights reserved.

Clifford Chase is the author of Winkie, a novel, and The Hurry-Up Song, a memoir. He edited the anthology Queer 13: Lesbian & Gay Writers Recall Seventh Grade, and his writing has appeared in publications ranging from Newsday to Yale Review to McSweeney’s. He lives in New York City.

Salty Language for Kids, and Other News

“Auden said something disparaging about Samuel Beckett getting the Nobel Prize for Literature. Nikos said: ‘Who else is there?’ Auden shook his head so all the sagging wrinkles shook and said: ‘There’s me.’” The gossipy diaries of David Plante.

Speaking of Beckett, “Fail better,” a quotation from his Worstward Ho, continues to be wildly misappropriated by Silicon Valley execs who refuse to pay obeisance to its pessimism.

In the UK, a children’s book about a foulmouthed boy with Tourette’s syndrome prompts a debate: Should salty books for young readers come with a warning?

Now in print: “Footlights,” a novella by Charlie Chaplin that inspired the screenplay for Limelight. “‘Footlights’ is 70 pages long and contains around 34,000 words,” notes the BBC. Gosh, tell me more!

The New York Times’ facile editorial page is under fire from its own staff: “Largely irrelevant.” “A waste of money.” “An embarrassment.”

Facebook, Gmail, and Twitter are classically conditioning us. Notifications are a “never-ending arms race of cheap con games to compete for user attention.”

February 4, 2014

Turtle Thoughts (Two of Them)

Photo: Tarek Chowdhury

I finished Russell Hoban’s Turtle Diary on the train this morning, and, wouldn’t you know it, today’s his birthday.

Hoban, a Pennsylvanian who lived most of his life in London, was born in 1925 and died in 2011, leaving behind a wondrous collection of sixteen novels for adults and even more for children. Turtle Diary—in which two aloof, single Londoners conspire to free sea turtles from the zoo—was reissued last year and should be required reading for anyone who lives alone, feels alone, or may one day reckon with loneliness. It’s endlessly quotable, and not in the cheap, aphoristic way that people sometimes mean when they say “endlessly quotable”—Hobanisms do not belong on tea bags or T-shirts, or even necessarily in Barlett’s. It’s more that the whole novel demands to be read aloud, ideally to an audience of one. It might be most fitting, actually, if you read it aloud to yourself. To celebrate Hoban’s birthday, here are two of the novel’s many delightful “turtle thoughts”:

The sign said: “The Green Turtle, Chelonia mydas, is the source of turtle soup … ” I am the source of William G. soup if it comes to that. Everyone is the source of his or her kind of soup.

I think of the turtles swimming steadily against the current all the way to Ascension. I think of them swimming through all that golden-green water over the dark, over the chill of the deeps and the jaws of the dark. And I think of the sun over the water, the sun through the water, the eye holding the sun, being held by it with no thought and only the rhythm of the going, the steady wing-strokes of the flippers in the water. Then it doesn’t seen hard to believe. It seems the only way to do it, the only way in fact to be: swimming, swimming, the eye held by the sun, no sharks in the mind, nothing in the mind.

Self-Help

Photo: Iain Cuthbertson, via Flickr

For several years, I lived in a neighborhood that worried my parents. But I liked my neighbors, I could afford the rent, and, in the grand tradition of fools, I lived a blissfully oblivious existence. I never once felt unsafe.

Well, that’s not strictly true. My boyfriend and I had been living in the apartment for about two years when I acquired a job that necessitated my commuting to an office, and oftentimes returning after dark.

“I don’t like it,” he said grimly of the fifteen-minute walk from the subway. There had been a recent spate of rapes in the area, he pointed out. “Call me when you get on, and I’ll meet you and walk you home.”

Naturally, I did no such thing. Instead, I walked home every day like a normal person and felt completely safe.

Until, one especially late night, I noticed footsteps behind me. I tried to shrug it off and picked up my pace. The person behind me started walking more quickly, too. I crossed the street; the steps followed me. I made a turn; he was right behind me. Now I felt real fear. I walked as quickly as I could without breaking into a panicked run, and fished my keys out of my pocket, holding the sharp point between my fingers for use as a weapon, as we had been taught in freshman orientation. The steps behind me never faltered. My heart was hammering by the time I made it into our building and threw the deadbolt.

After that, I was more careful: I got home as early as I could and walked quickly, head down, instead of greeting people and observing changes in the neighborhood, as had been my wont. Yet I couldn’t help feeling uneasy, and I could have sworn that several times, I heard the steps.

And then, a few weeks later, I had to work late. And again, as soon as I moved off the brightly lit commercial strip onto a residential side street, I heard the steps behind me. Turning with me, keeping pace with me. This time, I did panic: I ran. I could hear the steps behind me, also running, and by the time I made it into the building, I was gasping and on the verge of tears.

My boyfriend was home and called out a cheerful greeting as he heard me slam the door and throw the bolt.

“What’s wrong?” he demanded, alarmed, when he saw my ashen face.

“I think someone’s been following me from the subway,” I said.

“Well, of course someone is,” he said matter-of-factly. “I pay Bill five dollars a day to wait at the subway stop and tail you home.”

Bill was our next-door neighbor, maybe mentally handicapped, who lived with his parents and had modeling aspirations.

“Wait, what?” I said.

“I was worried about you, so I asked him to meet you one night when I couldn’t be there, and then he asked if it could be a regular gig. He can really use the money,” he explained.

The next night, I looked for Bill outside the station and we walked home together. I learned a lot about Bill in the next weeks: that he wanted to segue from modeling to movie stardom, and maybe politics. That he dabbled in musical composition. That he was really good at the latest iteration of Final Fantasy.

There was a great deal of this kind of thing, now that I think about it; my ex-boyfriend is a very kind person.

* * *

That was several years ago. This morning, I was in the Times Square subway station, and I saw Bill. He was sitting behind a table in a shirt and tie, administering stress tests with a bunch of Scientologists.

I called my old boyfriend in California to tell him.

“I’m so glad he landed on his feet!” he said happily. “How was he?”

And I had to admit that I had not stopped to find out.

Five Down: O-O-H Y-E-A-H!

Photo: Martin Huber

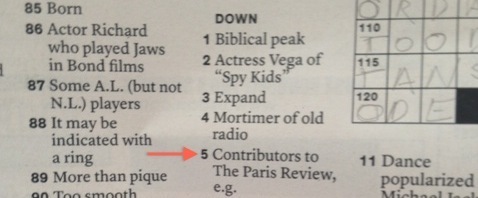

There are many yardsticks for fame and influence, but by my lights, you haven’t really “made it” until you’ve appeared in a clue for the Times Sunday crossword. In which case, we’ve made it. The Times may direct its complimentary jeroboam of Dom Perignon to 544 West 27th Street, New York, NY, 10001.

The clue is “Contributors to The Paris Review, e.g.” The answer is eight letters. Take your best guess.

The Attic of Empire

Remembering the National Air and Space Museum and the nation’s guilty conscience.

Photo: Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons

People think of Washington, D.C., as a transitory place—a city of four-year leases, tourists, and revolving doors—an impression that dates back to the earliest days of the federal capital. The city fathers, desperate to counter the District’s reputation as a provincial backwater, fought back by building monuments. Think of it as overcompensation, the attempt to create an illusion of age-old power. Why else plant a fifty-story Egyptian obelisk in the center of town?

For those of us who were born and raised in Washington, there was both a pride in living near the nation’s symbolic center and a nagging feeling that the city didn’t really belong to us. A drive down Massachusetts Avenue, past the mansions of Embassy Row, was a reminder of how much of the town was actually built on foreign soil. Even the parts that were supposed to be ours were somewhat foreign, in the sense that they belonged to the whole country. Our Fourth of July fairground was the National Mall; the church in which I sang was the National Cathedral; and our local museums were the Smithsonian Institution—the “Nation’s Attic.”

The museums were the best part of living in Washington. My friends and I took a proprietary interest in them. This might not be our town, exactly, but these were our museums, none more so than the National Air and Space Museum, which opened when I was nine years old and obsessed with outer space.

The ribbon cutting was a grand affair, timed to coincide with the nation’s bicentennial celebration. The robotic arm that cut the ribbon was activated by a signal from the Viking 1 spacecraft en route to Mars. President Ford, applauding this bit of high-tech theater, called the museum “a perfect birthday present from the American people to themselves.”

The museum quickly became the most visited attraction on the Mall; it’s now the most popular museum in the world. But in those early days, it seemed to have been built just for me. The moment I squeezed through the glass doors and stood at the sun-blasted edge of “Milestones of Flight,” the crowds melted away. I’d make a beeline for the Apollo 11 Command Module, which was encased in a clam-shell of ballistic plastic, just like the commemorative miniatures in the gift shop, and run my fingers over the scorched heat shield, imagining the astronauts’ fiery reentry.

But most of my go-to exhibits were military machines. I took a special interest in the trophies of war: aircraft that had been delivered to the United States as restitution. I never left the museum without visiting the biplanes of World War I, the Fokker and the Pfalz, with their wire struts and fabric-covered wings; or without shaking a self-righteous fist at the German V-2 rocket. I hated the V-2 as a weapon of Nazi terror, but I had to admire its elegant silhouette and the perfection of its paint job, a kind of abstract checkerboard in gleaming black and white.

The war trophies looked brand new, even the V-1 “buzz bomb,” which dangled from the ceiling trusses like one of the scale models that patrolled the airspace of my own bedroom.

I could almost imagine that winning a war was simply a matter of confiscating the enemy’s favorite toys.

* * *

The Air and Space Museum was conceived as a hanger on a monumental scale, an “attic” for famous and noteworthy aircraft. But by the late 1980s, the museum, under the leadership of a new director, began to explore a fresh line of inquiry: didn’t these masterpieces of technology have something to teach us about our nation and its place in the world?

The fiftieth anniversary of the dropping of an atomic bomb on Hiroshima was the perfect opportunity to unveil the newly restored Enola Gay, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress that delivered Little Boy on August 6, 1945. With the Enola Gay as a hulking backdrop, visitors to the museum would be asked to reflect on the facts of the case, to treat the Enola Gay, and, by extension, the atomic bomb, in the cold light of history. Photographs would display the consequences of the bomb side by side with its brilliant delivery system.

As a child, I’d seen full-scale replicas of Little Boy and Fat Man, the Nagasaki bomb, in the old Arts and Industries Building. I was terrified of nuclear war—Washington was ground zero!—and the bombs’ cartoonish shapes had given me nightmares. Now that the Soviet Union had fallen apart and the threat of mutually assured destruction was finally starting to fade, it seemed more important than ever to remember the horrors of Hiroshima.

I liked the sound of the proposed exhibit, but Air Force veterans of World War II—and the politically powerful veterans’ groups they belonged to—were outraged by its “neutral” character. Where was the pride? What did the victims of Hiroshima have to do with displaying an airplane? Instead of tarring our noble airmen with a war crime, shouldn’t we be down on our knees thanking them for the countless lives they saved by ending the war so quickly?

The controversy escalated to Congress, which supplies about two-thirds of the funding for the Smithsonian. Various members accused the Air and Space Museum of political correctness, intellectual dishonesty, revisionist history—of foisting a guilt trip on the American people. The Senate passed a nonbinding resolution against the exhibit, and the museum’s innovative director was forced to resign. A month later, a vastly simplified exhibit opened without much fanfare. A single succinct sentence described the Enola Gay’s role in the Hiroshima bombing:

On August 6, 1945, this Marin-built B-29-45-MO dropped the first atomic weapon used in combat on Hiroshima, Japan.

* * *

In the years that followed, I needed my museums more than ever, but in new ways: as a reminder of happier times, as a refuge from the pettiness and ego I encountered in my daily grind, and above all as source material for my stories. My imagination had always been drawn to obsessives: people who collected, categorized, curated, and fetishized. Thanks to family and friends who worked behind the scenes, I’d toured preservation labs, storage vaults, and stripped galleries. From an early age, I’d seen just how much artifice was involved in the illusion of authority.

Until the Enola Gay, I hadn’t fully absorbed the role of politics in museum-making. History was written by the victorious; museums were simply shrines to that history. It was hard to blame the Air Force veterans for feeling that their shrine was being desecrated. They saw the quashing of the exhibit as a patriotic victory, but I experienced it as the triumph of vanity over introspection.

As I was writing my novel Marshlands, which explores, among other themes, how an empire consecrates its military history, I drew on the shame I felt after the Enola Gay controversy. I made my characters feel what it is to have an important exhibit ruined by political exigency, to lose a museum that felt like theirs, and with it, a crucial claim to their own past. In Marshlands, the loss is particularly traumatic, since the civilization commemorated in the exhibit has vanished, a casualty of one of the empire’s foreign adventures. The woman organizing it is a refugee of that great disaster and comes to understand too late that there’s no room in her museum for a nation’s guilty conscience.

I wish the Air and Space Museum still retained its magic for me. These days, trudging up the marble steps and passing through the security gauntlet, which was tightened after those gleaming 767s decimated the twin towers, I feel like I’m entering an airport rather than a museum, like I’m finally, after all these years, leaving my own city.

Matthew Olshan is the author of Marshlands, a novel, out today, and several books for young readers, including Finn, The Flown Sky, and The Mighty Lalouche. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland.

Los Angeles Will Never Look the Same in Movies, and Other News

Photo: Los Angeles Bureau of Street Lighting

A strange but urgent side effect of LA’s switch from sodium-vapor to LED streetlights: in night shots, the city will look strikingly different on film.

One last item about the Super Bowl, before it goes graciously into the night—the art of Super Bowl ticket design.

As a postscript to yesterday’s Tulipomania post: Dennis O’Driscoll’s “Tulipomania,” a poem from the April 2002 edition of Poetry.

Relatedly: “Each day we are faced with sound bites and catchphrases deadening and trivializing our language … poetry is the corrective.” In defense of poetry’s cultural sway.

Against grammar, or its ruthless enforcers: “Blind adherence and conformity … pave the way for fascism.” Now everybody get out there and split some infinitives.

To the literary bachelors of New York: Housing Works’ Literary Speed Dating event needs more gentlemen seeking ladies. (Ladies’ tickets are sold out. They’re waiting for you, you, you!) The event is on February 10; use the discount code QUEEQUEG for three dollars off the fifteen-dollar admission.

February 3, 2014

Tulipomania!

On Holland’s legendary tulip bubble, which burst today in 1637.

Detail from Jan Brueghel the Younger’s Satire on Tulip Mania, 1640

When economists need to summon an age of unchecked speculation and financial fecklessness—usually as an analog to our own—the Dutch tulip mania is at the top of the list. If you’re not familiar with the story, it’s an early and especially hysterical example of the vagaries of the stock market: In the mid-1630s, the Dutch fell rapturously in love with tulips, whose vivid petals made them the envy of every Hendrik and Veerle in the neighborhood. The flower became a status symbol, and the Dutch were all but tripping over one another’s clogs in a race to conspicuously consume. To satisfy burgeoning demand, speculators began to trade in what were essentially tulip futures; these grew outlandishly complicated and expensive, and on the third of February, 1637, the tulip market collapsed.

The Scottish journalist Charles Mackay gave currency to the incident. He offers a trenchant, if dubious, account of the whole debacle in his 1841 book, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, which takes, as its title suggests, a pretty dim view of group dynamics. In his chapter on “the tulipomania,” Mackay presents a cautionary tale rife with tulip jobbers, tulip marts, tulip notaries, and tulip parties:

The demand for tulips of a rare species increased so much in the year 1636, that regular marts for their sale were established on the Stock Exchange of Amsterdam, in Rotterdam, Harlaem, Leyden, Alkmar, Hoorn, and other towns … The tulip-jobbers speculated in the rise and fall of the tulip stocks, and made large profits by buying when prices fell, and selling out when they rose. Many individuals grew suddenly rich. A golden bait hung temptingly out before the people, and one after the other, they rushed to the tulip-marts, like flies around a honey-pot … Nobles, citizens, farmers, mechanics, sea-men, footmen, maid-servants, even chimney-sweeps and old clothes-women, dabbled in tulips. People of all grades converted their property into cash, and invested it in flowers. Houses and lands were offered for sale at ruinously low prices, or assigned in payment of bargains made at the tulip-mart … In the smaller towns, where there was no exchange, the principal tavern was usually selected as the “show-place,” where high and low traded in tulips, and confirmed their bargains over sumptuous entertainments. These dinners were sometimes attended by two or three hundred persons, and large vases of tulips, in full bloom, were placed at regular intervals upon the tables and sideboards for their gratification during the repast.

Mackay also recounts the story of a sailor who ate a merchant’s tulip bulb, thinking it was an onion. He rotted in jail.

Most edifying of all, though, is a list of various articles that “were delivered for one single root of the rare species called the Viceroy,” which gives an astonishing sense of just how inflated the flowers’ value was:

Two lasts of wheat

Four lasts of rye

Four fat oxen

Eight fat swine

Twelve fat sheep

Two hogsheads of wine

Four tuns of beer

Two tuns of butter

One thousand lbs. of cheese

A complete bed

A suit of clothes

A silver drinking-cup

In defense of the Dutch, though, the Viceroy is, or was, one hell of a fetching flower:

Today, economic historians are inclined to believe that Mackay’s report is something of an embroidery; given the constraints of seventeenth-century record keeping, one suspects he wasn’t exactly poring over the data and crunching numbers. But I, for one, choose to regard Popular Delusions as gospel truth, if only because the image of a thousand pounds of cheese being relinquished for a single bulb is too fantastic to be fiction.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers