The Paris Review's Blog, page 745

January 24, 2014

What We’re Loving: Foam, Florida, Fiction Binges

I received my first issue of Mothers News this week—and now I wonder what I’ve been doing with my life. A free monthly broadside out of Providence, Mothers News is hyper, delirious, and weird. And, I now realize, essential reading. The eight-page rag is best known, and rightly so, for its comics—with regular strips by C. F., Michael Deforge, Mickey Z, Brian Chippendale, and others—but all the content is of a piece. This issue manages, for instance, a column devoted to foam (“What do we know about foam?”—quite a bit, it turns out); a top-ten list that includes a brief excursion into the etymology of “hoist by my own petard”; and an announcement that the UN has designated 2014 the International Year of Family Farming and Crystallography (IYFF 2014 and IYCr2014, respectively). There’s also, of course, the Ambrose Bierce Memorial Word Jumble and a coveted ad from the Lon Chaney Society of New England. —Nicole Rudick

I’ve been dipping into T. D. Allman’s Finding Florida: The True History of the Sunshine State, whose bright jacket belies its sharp dressing-down of our twenty-seventh state. In Allman’s telling, Florida is, and always has been, an accursed microcosm of the American dream—from its geology to its politics to its economics, everything about the place invites delusion, violence, and disaster. Some critics found this too apocalyptic, but I think Allman’s gloom is a valuable corrective, and he’s far from humorless; even his bibliography has fizz. (“Where the Boys Are [1960]. Groovy LA starlets play beach blanket bingo in Fort Lauderdale.”) You can read Florida, longlisted for last year’s National Book Award, as an erudite complement to Florida Man, a Twitter feed that lists the frighteningly constant stream of follies coming from the Sunshine State. The latest: “Florida Man Arrested for Beating Uncle with Toilet Seat.” —Dan Piepenbring

Over the long weekend I went on a New Yorker fiction binge and read every short story I’d missed in 2013. Among the gems I’d somehow overlooked: Tessa Hadley’s impeccable “Bad Dreams,” Thomas McGuane’s “Weight Watchers,” and “The Christmas Miracle,” by Rebecca Curtis, which is simply the funniest short story I have read in a year. It’s easy to carp at The New Yorker, because it’s an institution, but forget that and read the stories first. From week to week, they are often as interesting, as much fun to read, as anything in the magazine. —Lorin Stein

How often do you stumble across great new science fiction? It’s a genre that never gets the attention it deserves. All the more reason to delight in Jeff Vandermeer’s Annihilation, the first volume in his Southern Reach trilogy, which will be released throughout this year. The plot moves quickly and has all the fantastic elements you’d ever want—biological contaminants, peculiar creatures, mysterious deaths—but it’s the novel’s unbearable dread that lingers with me days after I’ve finished it. —Justin Alvarez

In love as I am with Ann Patchett’s novels, I’m especially compelled by her new collection of essays, This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage. Patchett meditates on camping in a Winnebago, discovers her love of opera through her distaste for country music, and reconciles her Catholicism with her divorce. (As the title implies, her remarriage has been a happy one.) All this is suffused with the same quiet authority and lyricism that had me hooked at Bel Canto. —Rachel Abramowitz

Robert Burns’s “Address to a Haggis”

Photo: Bernt Rostad, via Flickr

To paraphrase Laurie Colwin, the world divides unequally between those who love haggis (not too many) and those who loathe and fear it (most). Tomorrow is Robert Burns’s birthday, aka Burns Night, which is to say, probably the zenith of the haggis-eating year. Whether this strikes dread or delight into your hearts, I cannot say.

Burns—aka the Ploughman Poet, aka Robden of Solway Firth, aka the Bard of Ayrshire—was a poet, folklorist, lyricist, radical, bon vivant, womanizer, and, during his lifetime, certainly the greatest promoter of Scottish history and culture. Sir Walter Scott (no slouch himself in the mythologizing department) met the poet as a teenager in Edinburgh and later recalled,

His person was strong and robust; his manners rustic, not clownish, a sort of dignified plainness and simplicity which received part of its effect perhaps from knowledge of his extraordinary talents … I never saw such another eye in a human head, though I have seen the most distinguished men of my time.

The first Burns Supper was held in June 1802, not many years after the poet’s death at age thirty-seven. But, perhaps on the thinking that haggis and whiskey are best enjoyed in frigid weather, the celebration has for some time now been held on January 25. The traditional Burns Supper contains a number of prescribed steps, including the Selkirk Grace (allegedly penned by Burns for the Earl of Selkirk), a Toast to the Lassies, a Toast to the Laddies, speeches, “Auld Lang Syne,” and muckle, muckle piping.

As we all know, we Americans love celebrating our heritage, no matter how distant such connections may be. Sometime in the early nineteenth century some of my grandfather’s relatives came over from Skye, and family lore has it that this branch of the tree is responsible both for a persistent strain of manic depression and the fact that occasionally someone has sort of reddish hair. (I think at some point my brother, whose middle name is MacKinnon, had a tartan tie, too, from one of the Scottish stores full of cashmere and kilts.) And that’s good enough for me! I don’t go in for throwing trees and wearing sporrans or anything, and the reels look really hard, but I’m a sucker for bagpipes. The spot where I enjoy my annual haggis (a pub in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village) does a somewhat abbreviated version of things, but of course the haggis is piped in, borne by a brae kilted lad, and the “Address to a Haggis” is recited in stentorian tones. I might wear a tam o’shanter. And just in memory of my heritage, take an Abilify at the table, washed down with Glenlivet.

This poem was published in an Edinburgh periodical, the Caledonian Mercury, on December 20, 1786.

Address to a Haggis

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the pudding-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o’a grace

As lang’s my arm.

The groaning trencher there ye fill,

Your hurdies like a distant hill,

Your pin wad help to mend a mill In time o’need,

While thro’ your pores the dews distil

Like amber bead.

His knife see rustic

Labour dight,

An’ cut you up wi’ ready sleight,

Trenching your gushing entrails bright,

Like ony ditch;

And then, O what a glorious sight,

Warm-reekin’, rich!

Then, horn for horn, they stretch an’ strive:

Deil tak the hindmost! on they drive,

Till a’ their weel-swall’d kytes belyve

Are bent like drums;

Then auld Guidman, maist like to rive,

Bethankit! hums.

Is there that owre his French ragout

Or olio that wad staw a sow,

Or fricassee wad make her spew

Wi’ perfect sconner,

Looks down wi’ sneering, scornfu’ view

On sic a dinner?

Poor devil! see him owre his trash,

As feckless as wither’d rash,

His spindle shank, a guid whip-lash;

His nieve a nit;

Thro’ bloody flood or field to dash,

O how unfit!

But mark the Rustic, haggis-fed,

The trembling earth resounds his tread.

Clap in his walie nieve a blade,

He’ll mak it whissle;

An’ legs an’ arms, an’ heads will sned,

Like taps o’ thrissle.

Ye Pow’rs, wha mak mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill o’ fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware

That jaups in luggies;

But, if ye wish her gratefu’ prayer

Gie her a haggis!

The Patron Saint of Writers and Journalists

Today is the feast day of Francis de Sales, the patron saint of writers and journalists. A bishop of Geneva, Francis died in 1622. He was fond of using flyers and books to convert Calvinists: hence his patronage.

Francis’s most enduring work is 1609’s Introduction to the Devout Life, which was written for laypeople—a novel idea at the time. CatholiCity, a repository of “the Finest Catholic CDs, Booklets, and Novels,” calls it “the most popular Catholic ‘self-help’ book of all time,” and when you peruse the table of contents, it’s not hard to see why. There’s plenty of practical wisdom on offer, e.g., “All Evil Inclinations Must Be Purged Away”; “One Word to Maidens”; “Dryness and Spiritual Barrenness”; “How to Exercise Real Poverty, Although Actually Rich”; and, conversely, “How to Possess a Rich Spirit Amid Real Poverty.” Then there’s the meditation on hell, which goes from yogic to despairing at the drop of a mitre:

Preparation

1. Place yourself in God’s Presence.

2. Humble yourself, and ask His Aid.

3. Picture to yourself a dark city, reeking with the flames of sulphur and brimstone, inhabited by citizens who cannot get forth.

In fact, hell has a way of rearing its infernal head at awkward moments throughout the Devout Life, perhaps as in life itself. Here’s a bit from “Balls, and Other Lawful But Dangerous Amusements,” which doesn’t mean what you think it does:

Balls and similar gatherings are wont to attract all that is bad and vicious; all the quarrels, envyings, slanders, and indiscreet tendencies of a place will be found collected in the ballroom. While people’s bodily pores are opened by the exercise of dancing, the heart’s pores will be also opened by excitement … while you were dancing, souls were groaning in hell by reason of sins committed when similarly occupied, or in consequence thereof.

Buzzkill, Francis! Not all his advice is so starchy, though. In “We Must Attend to the Business of Life Carefully, But Without Eagerness or Over-Anxiety,” he writes, “Imitate a little child, whom one sees holding tight with one hand to its father, while with the other it gathers strawberries or blackberries from the wayside hedge.” (I do this literally all the time—can’t recommend it highly enough.)

Still, if Francis has really been watching over the Fourth Estate for these many centuries, one imagines he’s pretty disappointed with the profession. After all, journalists and writers are not known for their piety, to put it mildly. Saving Calvinists from perdition no longer moves us to dip our pens. Should you feast to Francis tonight, you might do him a solid and refrain, as he asks of you, from “too much thoughts of meats and platters.” Then he could check off that box, at least, and think to himself, Frank, you old sermonizer, you’ve still got it.

You can read all of Introduction to the Devout Life on CatholiCity, which also offers a FREE JESUS CRUCIFIED LAPEL PIN AND 8X10 ART-HOUSE PRINT to all who donate.

A Freaky Friday Excerpt from the Next McSweeney’s

Illustration: Carson Murdach

Do not adjust your set. What you see before you is an excerpt from the latest issue of McSweeney’s, our alluring, laid-back, westerly sister. Curiouser still, the McSweeney’s site has an excerpt from our new interview with Geoff Dyer. Have we gone mad? Yes, because we’re also offering an insane deal: a dual, twenty-percent-off subscription to both our magazines. It’s bonkers—we’re practically burning money. Our accountants are tearing their hair out; our lawyers are sweating through their suits. But if you don’t take advantage of this deal, you’re the crazy one—and it’s only available for seven more days. Subscribe now.

SWAN DIVE

All those mornings, our bodies slicked with a sugary sweat. Pure alcohol. You could’ve tasted the night before just by licking our wrists. Stella arcing back so the girls could do body shots from between her perfect breasts. The men drinking and watching, You’re a flexible little thing, aren’t you, sweetheart?

We were inexhaustible in those final few months, throwing ourselves around every chance we got. Our heads might’ve rolled off and we wouldn’t have noticed. Mine probably did. Amanda and Stella started dancing at the Foxhouse two or three nights a week because the money was good and our rent was insane. Then it was three or four nights. They’d show up at the studio in the morning still smelling of tipping dollars. It’s okay if you’re smart about it, they said, stretching at the barre. If you don’t hate it enough to start looking for ways to forget about it.

You should think on it, said Stella, who was spending half the week as Lola.

That accent. They’d eat it up. Amanda was Ruby from Thursday to Saturday.

A swan dive, I guess you could call it.

Sometimes I want to tell you about this, but I won’t. How the hours slammed up against each other. I’d never seen so many sunrises. We’d peel away our damp costumes and step straight into three-dollar g-strings that were only good for a few nights, until the lace was discolored with sweat. The other girls at the club told us we should stick to darker colors: black, navy, even red. Then we wouldn’t be going through so many pairs. But we knew what we were doing. Pale blue. Sugar pink. White, white, white. Let them think we were angelic. We knew how to be angelic.

BRISBANE

And she had this way of swiveling her head round like an owl to talk to you as she drove, except not like an owl because the skin of her neck creased up in folds and she looked so old when that happened, though she wasn’t, not then, and Luke would lean over and say, Watch the road, Mum.

And what I’ll remember of this time is split vinyl and continental breakfasts, fights about who gets the passenger seat, a wallaby cracked over the head with the jack handle and none of us talking till Lismore even though we know she’s done the right thing.

We pull in silent to the motel, a low, sandy-brick L shape, with all the doors facing onto the car park and the car park mostly empty, mostly dark. Our room is No. 17 and there is a TV that only gets two stations and one double bed, which my brother and I fall into fully clothed with only our shoes kicked off. But something wakes me a few hours later and I panic, forgetting where I am. I go over to the window on shaky legs and see her from the back, standing out by the road. A blond in denim pedal pushers and white tennis shoes, standing in the light of the motel sign, like the ghost of 1967. Ghost of her younger self, holding a slim beer bottle down by her hip, fingers round its throat like she wants to swing it at something.

In the dark of the room I find the bar fridge, take a bottle of cola from inside the door. Luke lifts his head from the pillow and says, Eli, don’t you drink that. Those cost like four times as much as they do in the shops, and I say, Shut up, I’m not going to, and I go back to the window. Try to stand the way she does, the bottle dangling loose from my fingertips. Like I don’t care if I drop it. Like I don’t care about anything. She stands like that for a long time, just looking out at the road like she’s waiting for someone to come pick her up.

In the morning there are flecks of rust-colored hair dye in the bathroom sink, and Luke takes one look at her and says, That’s not going to change anything, Mum, because he’s older and sharper than I am but he still gets a slap for it, so we’re all silent in the car again, all morning, and I wish the radio still worked.

When we get to Brisbane, she’s telling us, You won’t even remember. And I don’t know if she’s talking about Dad or the slap, or the wallaby or Victoria or that she was ever a blond, but in any case I know she’s lying, ’cause she’s got her lips pressed into a pale line and her eyes fixed hard on the road.

HOUSE

When I write of a house now, it is only ever the one house: its smell of smoke and old wood, foxed books, dried blue gum ripped lazily from the overgrown yard. Perhaps you haven’t realized this yet. Because in one story, I’ve sat you at the monstrous kitchen table, its surface a forest of knives, their tips driven into the southern mahogany. The empty knife block hidden among them like the woodcutter’s empty cottage. And in another story, we are crouched behind the ruined shed, among the blood and the feathers, and from here the kitchen cannot be seen. Stand in the birdless aviary (you know where we are now, don’t you?) and you won’t see me lying on the slate floor, won’t feel my hands on either side of your face. You won’t hear me saying there isn’t a single thing I feel sorry about. It’s only ever the one house, but it’s shifting, unmappable, and I can never get far enough away to see the whole of it.

Josephine Rowe is an Australian writer of fiction, poetry, and essays. Her short story collections are How a Moth Becomes a Boat and Tarcutta Wake. She currently lives in Montreal.

The Flatus of Yore, and Other News

What a gas! Image via Beautiful Decay.

Japanese scrolls from the Edo period depict—yes—erumpent, competitive flatulence.

Back to more dignified fare. Guess the classic novel from its first sentence.

Fact: Kurt Vonnegut wrote a made-for-TV movie in 1972. It’s called Between Time and Timbuktu, or Prometheus-5: A Space Fantasy. Vonnegut later withdrew from the production: “I am not going to have anything more to do with film—for this reason: I don’t like film.” Well. As far as excuses go, that one’s airtight.

“I think empathy is a guy who punches you in the face at a bus station, and you’re somehow able to look at him and know enough about what situation he was in to know that he had to do that and not to hit back. That’s empathy, and nothing ever happens in writing that has that kind of moral heroism about it.” A new interview with John Jeremiah Sullivan.

As any reader of Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity knows, vagueness can be artful, but it’s especially so in Mandarin writing, where ambiguous sentences resemble optical illusions.

January 23, 2014

Save Rizzoli

Since 1985, Manhattan’s Rizzoli Bookstore has occupied a spectacular six-story limestone townhouse on 57th Street—their website aptly goes in for a bit of self-congratulation, touting the “cast iron chandeliers, ornately decorated vaulting, and a luminous Diocletian window.” You can learn more about the history of the building here. It’s the sort of place that inspires breathless exaltation in book lovers, or even merely book likers; if you were to publish a magazine of bookseller porn, Rizzoli would be the centerfold. Put more baldly, it’s magical.

Alas, in a plot turn that seems ripped from a bad movie, realtors have designs on the building—they want to demolish it and build a highrise. One can only imagine the cackles that issue from their inner sanctum with so many malignant plumes of cigar smoke.

But fear not. Citizens have come together, as we are wont to do, to preserve Rizzoli as a landmark. Sign the petition to help save Rizzoli, and, as a bonus, to ensure that these dastardly realtors are left stomping their finely crafted hats.

From the Margins

A rainbow-colored beast from the margins of a fifteenth-century text. Image via the Public Domain Review.

In college, I was excited to discover a student-produced, fly-by-night zine called “From the Margins.” I don’t know what’s more embarrassing: that I assumed it was devoted to marginalia or that I was seriously juiced about the idea. When I opened its creased, xeroxed pages, though, I found it was devoted not to literal margins but to my school’s “disenfranchised peoples,” most of whom struck me as too well-heeled to feel put out.

In any case, this month has granted my wish: it’s seen some great attention paid to margins, the kind on paper. Open Culture featured Dostoevsky’s manuscript doodles, which demonstrate not just his remarkable penmanship but also an affinity for faces and architecture. (The former, to no one’s surprise, are deeply melancholy.) The Public Domain Review resurfaced some rainbow-colored beasts “found in a book of hours attributed to an artist of the Ghent-Bruges school and dating from the late fifteenth century,” and Brain Pickings resurfaced a piece about Edgar Allan Poe, “history’s greatest champion of marginalia.” Poe is indeed unreserved in his praise; he also suggests, “If you wish to forget anything upon the spot, make a note that this thing is to be remembered.”

Oh, that Poe! He’s a regular Mark Twain.

Last, Sam Anderson and David Rees have defaced, or, uh, annotated, a copy of Dan Brown’s Inferno, much to its benefit. There’s a lot of comfort in seeing—next to such atrocious lines of dialogue as “Don’t let her beauty fool you, she is a dangerous foe”—the red, hateful tendrils of a handwritten EAT SHIT.

It’s exactly the sort of thing I’d hoped to find in “From the Margins.”

Customer Service

Photo: Romley, via Flickr

I grew up in the suburbs of New York City, in one of the handful of commuter towns along the Hudson. One of these villages contained a bookstore—a good one, with a fine selection of titles and a section devoted to attractive wrapping paper and greeting cards. However, the owner was so unfailingly nasty and abusive to her customers that my mother and I came to regard it as a challenge to make it in and out of the shop without incurring her wrath.

We seldom succeeded. Anything might set her off: an innocuous question, a breach of obscure etiquette, a sneeze. Needless to say, she had a hard time keeping staff. Everyone was scared of her, and the atmosphere of the store was one of silent terror.

There was only one occasion on which we saw anyone break through the ice. My mom and I had been compelled to patronize the shop after failing to find Miss Rumphius anywhere else, and we had steeled ourselves for the arctic blast of the proprietor’s contempt. But when we walked in, we met with an amazing scene. A plump, jolly woman was leaning against the counter and thumbing through a novelty book—something about Jewish wit and wisdom, shaped like a large bagel.

“Oh, wait—listen to this one!” she was saying. “When the temple was destroyed … the Jews built Loehmann’s!” She went off into gales of laughter.

The shop owner remained stony-faced. Then:

“It’s true,” she said, coldly.

* * *

Frieda Loehmann opened the first iteration of the store in Brooklyn in 1921, selling designer overstock at bargain-basement prices. At its peak, the chain had one hundred stores in seventeen states. But I wonder if it ever acquired the mystique, or whatever you’d call it, that it carried here in New York.

Mystique, in fact, is sort of the opposite of what characterized Loehmann’s. Despite the promise of the fabled “back room”—the area that carried high-end designs—the experience was aggressively low-rent. The particular smell of silk knits; the racks of dowdy blouses; the dozens of designers you’d never heard of; the cruelly lit communal dressing room, filled with matrons zealously stripping naked; the mortification of bra shopping with my mom; the lack of any customer service whatsoever—this is what I remember. I also had my wallet pinched at the Fordham Road location when I was sixteen and looking for a cardigan to wear over my prom dress.

My mom and I did the vast majority of our shopping at Loehmann’s, with occasional forays to the superb New Rochelle Salvation Army, but I can’t remember ever buying anything I really liked there. Part of the problem is that we only shopped when I “needed” something, and the one law of bargain shopping is that you will never find what you are looking for; it is an exercise in surrendering to fate, not attempting to master it. Whatever we found would have a strange cut, a gratuitous ruffle, a peculiar shade. I remember well the frantic trip to try to find ankle boots to wear with a new skirt; I was about to meet my college boyfriend’s family. The booties we found were square-toed and kind of weird looking, but I felt good about them. It wasn’t until I saw my boyfriend’s sister staring fixedly at the sole of one of my shoes that I noticed the red 70% OFF sticker.

But it was just what you did.

If you’ve ever read The Bintel Brief, the sixty-year collection of Forward advice columns that helped Jewish immigrants navigate the challenges of a new, secular world, you may recall the plight of one Sadie Frowne, a garment worker who faced criticism for spending her hard-earned money on clothes. “Those who blame me are the old-country people who have old-fashioned notions, but the people who have been here a long time know better,” she writes. This would have been shortly before Frieda Loehmann opened that first Crown Heights store.

In December, Loehmann’s filed for Chapter 11, and now all the stores are liquifying their inventory. They’ll be closed by March. The Chelsea location is going to be a Barneys.

But I looked up that bookstore on Yelp and found it had a one-star rating. “Jeez, the older lady manning the place is a grouch. I literally stepped in & out in less than a minute,” said the first reviewer. Added the next: “Forget the merchandise, prices, or anything else by which you would ordinarily judge a business. The short, elderly woman who works here (presumably the owner) is an absolute nightmare. Ask anyone in the area; she’s infamous. One interaction with her, and you will NEVER want to set foot anywhere near this godawful place ever again.”

It is good to know that some things never change.

“The Past Is a Mist”: Pinter’s Proust

Photo © 2014 Nancy Crampton

Yellow screen. Sound of a garden gate bell.

Open countryside, a line of trees, seen from a railway carriage. The train is still. No sound. Quick fade out.

Momentary yellow screen.

The sea, seen from a high window, a towel hanging on a towel rack in foreground. No sound. Quick fade out.

Momentary yellow screen.

Venice. A window in a palazzo, seen from a gondola. No sound. Quick fade out.

Momentary yellow screen.

So begins the wordless sequence of thirty-six shots at the start of The Proust Screenplay, Harold Pinter’s adaptation of À la recherche du temps perdu, written in the seventies and never filmed.

To celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the publication of Proust’s Swann’s Way a series of public events have been planned in New York. Part of 92Y’s contribution to the centenary was a staged reading of Pinter’s The Proust Screenplay, which was produced at the National Theatre in London in 2001 but had never been performed in the States before its 92Y debut. Helmed by the same director from the National’s production, the 92Y’s reading was directed by Di Trevis, who collaborated with Pinter to stage his screenplay. Performed by a cast of fourteen—led by Peter Clements, a dead ringer for Proust—the crowded event felt like a staged reading in name only; fully blocked out with lighting cues, set pieces, and props, the presence of the actors’ scripts was the only sign that this wasn’t a complete production.

At first glance, a writer known for menacing silences, clipped phrases, and testosterone-fueled brutality—all of it rife with ambiguity—hardly seems the obvious candidate to adapt Proust. When I think of Proust, I think of long and mellifluous sentences, lush, discursive scenes, and linguistic precision—all of which are at odds with a playwright who is perhaps best known for his use of the pause. In a description of his own work to students in the sixties, Pinter said, “I think that we communicate only too well, in our silence, in what is unsaid, and that what takes place is a continual evasion, desperate rearguard attempts to keep ourselves to ourselves. Communication is too alarming.”

But if Pinter and Proust would seem to be at stylistic loggerheads, look at their shared themes and obsessions, particularly their mutual fixation on memory, and suddenly Pinter’s project seems not just sensible but inevitable. In the early seventies, Pinter tackled the “memory play” with No Man’s Land and Old Times, dramas where memories become weaponized. In No Man’s Land—currently in repertory on Broadway, at the Cort Theatre—two older men spar with their recollections, using them as a way to gain the upper hand. It’s never clear what’s true, whether their stories are false memories or outright lies. A character in Old Times remarks, “There are some things one remembers even though they never happened. There are things I remember which may never have happened but as I recall them they take place.” Little wonder, then, that Pinter was fascinated by Proust and the way he transformed recollection into art. In a very Pinteresque statement, Proust himself said that art was born “not of conversation and the light of day but of darkness and silence.”

Adaptation is a form of memoir. Both require the writer to take up fragmentary impressions of a whole to create a sense of order. The inclusions and omissions in Pinter’s screenplay, the construction of his scenes, map his singular experience through the text as a reader; we see what stood out for him in Proust. For the most part he plays the hits—Marcel’s need for a goodnight kiss from his mother; Odette and Swann’s sonata; the patch of yellow wall in Vermeer’s View from Delft; the vision of Gilberte’s daughter—and leaves out the deep cuts. For obvious reasons, a lot of material ends up in the bin; the staged reading lasted about two and a half hours with an intermission, condensing nearly four thousand pages into a standard evening at the theater. There aren’t even any madeleines.

Pinter’s script—like a memory play that passes over some details and exaggerates others—trains its eye on class conflict and memory. He makes chronology dissolve in an enlightening way here: the entirety of Marcel’s life seems to exist in one simultaneous, present moment. And Pinter is particularly good with the slipperiness of memory in Proust. Toward the end, when Marcel interrogates a friend of Albertine’s as to whether or not she is a lesbian, the scene alternates two mutually exclusive versions: one where the friend declares Albertine has dallied with many women and another where she earnestly denies that Albertine is capable of this “vice.”

Like many great, long works, À la recherche du temps perdu is widely discussed but seldom read in its entirety. Lydia Davis, translator of the finest English-language version of Swann’s Way, confesses in her introduction that she had never finished the first book until she translated it; Pinter, too, admits in his introduction to the published edition of The Proust Screenplay that he had only read Swann’s Way before setting out to tackle the whole series. The Proust Screenplay steps in where our efforts to reach the end of Proust’s work have failed—it’s a sort of Cliff’s Notes for the cultured. Without an adaptation, how else could you get an intelligent bird’s eye view of this entire work? Pinter’s script streamlines the themes, further distilling memory into art into the most essential moments.

In the end, Pinter’s screenplay, as sophisticated and loyal as it is, encounters obstacles that have little to do with its quality and more to do with the way Proust’s work affects us. At intermission, a woman sitting behind me leapt up and declared, “Horrible,” huffing out of the theater. But I’m not sure the failure, if there was one, belonged to Pinter, to say nothing of the director and cast. Reading is always personal, but it may be that no other work is scored for the individual the way Proust’s is. The uncanny way Proust mirrors thought gives us a feeling of ownership of the work that we rarely experience with other books. We all have our own way of imagining the three steeples, little Marcel’s boyhood crushes, Swann’s walk, and, of course, just what that madeleine tastes like. Proust’s memories mingle with our own and transform them. His prose is so infectious that I start to feel drowsy when Marcel sleeps; my lungs wheeze when his asthma flares up.

Books have a hypnotic power to make us feel like we are a part of them, something Proust himself observes in the first paragraph of Swann’s Way: “I had not ceased while sleeping to form reflections on what I had just read, but these reflections had taken a rather peculiar turn; it seemed to me that I myself was what the book was about: a church, a quartet, a rivalry between Francois I and Charles V.” So I can’t exactly blame my imperious fellow audience-member for her outburst. Seeing Marcel enter the stage gave me that startling sick feeling—like reaching for your mother as a four-year-old only for her to turn around and to have some other woman’s face attached her head. Can Pinter’s fragmentary reconstruction of Proust ever match our memories of it? On my way home from 92Y, I couldn’t wait to slip under the covers, with my inhaler on the pillow next to me, and climb into bed with my Proust.

Christopher Richards is on the editorial staff of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. His essays have appeared on The Millions, Guernica, and FSG’s Work in Progress.

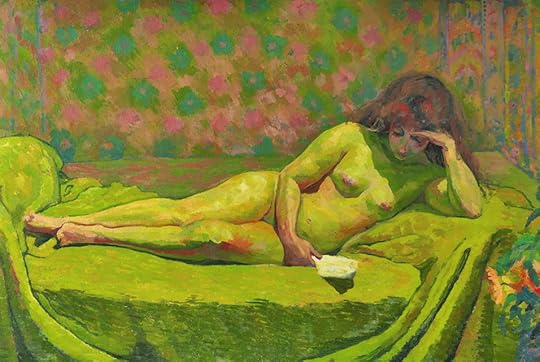

Nudity Defended, and Other News

Giovanni Giacometti, Theodora, 1914, oil on canvas.

The return of Girls also means the return of prudish, puzzled critics. As a riposte, six reasons (just six?) that female nudity can be powerful when it’s not sexual.

What if classic novels were “whorishly titled, optimizing our search engines rather than our imaginations”? (Jane Eyre is a personal favorite: “This Guy Didn’t Tell His Governess About His Secret Ex-Wife in the Attic. What Happened Next Really Burned Him Up.”)

Fiction in translation is on the rise.

The British Library’s new exhibition of comic books aims to inspire children to be “naughtier and more rebellious.” Embrace obscenity, kids. Do not eat your spinach. Kill all fascists.

We live in a time of ever more florid author bios—here are three questions a good bio should answer. (Spoiler: one of them is “Who are you?”)

Parsing punctuation in Internet initialisms: Is the semicolon in “tl;dr” ironic?

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers