The Paris Review's Blog, page 747

January 20, 2014

Hear Chinua Achebe Discuss Martin Luther King Jr.

Achebe at the fiftieth anniversary of Things Fall Apart. Photo: Angela Radulescu

Last week we brought to light a few videos of George Plimpton we’d found on the original version of our Web site, circa 1996. Today we have another highly apropos discovery from those days: audio from an unused portion of the Art of Fiction No. 139, an interview with Chinua Achebe conducted for our Winter 1994 issue. In this clip, Achebe, who died last year, discusses the legacy of none other than Martin Luther King Jr. A transcript follows:

Yes, I think certainly, in my view, that Martin Luther King is an ancestor. And although he died at the age of thirty-nine, this is something we do not often remember: how young he was when he was cut down. But his achievement was such that some who lived to be a hundred didn’t achieve half as much. So he does deserve that status, that standing. If he were in my country, he would be worshipped … I did not meet him, unfortunately, and I think one of the reasons was what I have just said: that he died too young. He was thirty-nine. Gandhi, with whom he is often compared, had not even returned to India at thirty-nine; he was still studying. We are thinking not about a sportsman, who can achieve his peak at eighteen; we are thinking of a philosopher, a thinker, who had to mature into action. I have been lucky in the past few years to be invited, again and again, to speak on his day—two years ago at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and then last year at the Smithsonian, so I’ve become something of an expert on Martin Luther King.

Recapping Dante: Canto 14, or a Finger-Wagging Editorial Letter

Priamo della Quercia, Dante Meets the Sodomites, c. 15th century.

Dear Dante,

I’ve received your manuscript for Canto 14 of the Inferno, and I have quite a few notes. The language and poetry of this passage is absolutely magical; a few passages in particular caught my attention, such as “The gloomy forest rings it like a garland,” (line ten), which is such a beautiful way of phrasing it. And the expression “scorn for fire,” on line forty-six, sounds like the title of a Philip Roth novel. You have a good ear for lyricism and your poem is a unique, fascinating glimpse into theology, history, literature, even love. You’re really carving out a niche for yourself in the Italian canon—kudos!

That said, certain parts left me wanting more, and they confused me enough to wonder if you were really trying your hardest. On line forty-three, Dante addresses Virgil by saying, “Master, you who overcome all things—all but the obstinate fiends who sallied forth against us at the threshold of the gate.” This really threw me off. For the whole poem, Dante has been meek, eager to be with Virgil, and here it almost seems as if he’s mocking Virgil. It doesn’t really fit in with the reader’s impression of Dante—which, I hasten to mention, you have spent the last thirteen cantos crafting expertly.

This canto focuses on those who have sinned against God. Their punishment is to have flakes of fire slowly rained down on them (nice touch, by the way—very Sodom and Gomorrah). Our attention is drawn to one sinner who is sitting in the corner brooding, almost without regard for the flakes of fire falling over him; it’s such a magnificent image that I almost expect him to be Hector or Achilles, but instead it’s a small-timer named Capaneus, who goes on to talk about Thebes for a few lines. From what I understand, Capaneus is in hell because after his victory at Thebes, he scorned Jupiter, who in an instant struck him with lightning for blasphemy. I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again: you need to find a readership and speak to it. Nobody will know who Capaneus is, Dante. You already told the story of an unknown historical figure in the last canto; now it’s time to make a splash. If you want to talk about Thebes, let’s tag in Oedipus himself.

Virgil then yells at Capaneus—in fact, he’s downright nasty to Capaneus, which was a treat to read. We should have more of Dante and Virgil being mean to sinners. (Cruelty sells.) On the other hand, I’m starting to get the impression that some of these sinners aren’t really such awful people, and I almost expect someone near and dear to Dante to make an appearance in the next canto or so. It can be hard to know who we’re really supposed to pity. Your book would benefit from a line drawn in the sand—sinners on one side, non-sinners on the other.

The two move on. They come to a river, and I have to say, this is where you lost me. Dante is interested in this river, so he asks Virgil what it is, and then Virgil rattles off the names of a few different rivers. Well, which river is it? How many rivers does hell need? I think three is enough, ending with the blood bath. Anything after that is overkill.

Virgil tells Dante a story about some woman taking a baby into the mountain. Twenty minutes of Wikipedia-ing later, I figure out that the woman is Saturn’s wife and the baby is Jupiter. You should come right out and say this.

But that’s not even the worst of it. Virgil tells another story about a man in a tower: each of his limbs made of a different element, and he’s crying and the tears are rivers? What is this? Nobody I showed this to could make heads or tails of it. I’m getting the distinct impression that, rather than addressing your peers, you’re writing for some arbitrary audience that will exist over the course of the next several hundred years or so. Ambition is good, Dante, but too much can be a curse.

I like what I’ve seen so far, and I hope we can do a playback on this Canto to get it back on track.

Warmest regards,

Johann Neumeister

P.S. Are you sure you want to continue writing this in Italian instead of Latin? I’m not really comfortable with breaking from tradition like that. Who knows where we could end up?

Blue Monday, and Other News

Edgard Farasijn, Sad News, c. 1880.

Today is supposedly Blue Monday, the saddest day of the year. And Jude the Obscure, 120 Days of Sodom, Germinal: these are among the fifteen most depressing books in literature.

And yet The Day of the Locust lands on a list of comfort reads.

Ship first, ask questions later. Amazon’s latest stratagem: “anticipatory shipping,” a program in which the company preemptively sends you products it expects you to buy, “based on previous searches and purchases, wish lists, and how long the user’s cursor hovers over an item online.”

Not unrelatedly, here’s a roundup of socially resonant dystopian fiction. “These dystopias, I think, speak to a different kind of anxiety … one of widespread helplessness in an unfathomably complex world.”

“Using science to explain art is a good way to butcher both.” A scorched-earth takedown of Jane Austen, Game Theorist.

This roundup is looking pretty bleak. In the name of balance, a celebration of literary rule-breakers.

January 17, 2014

Lysley Tenorio, New York, New York

A series on what writers from around the world see from their windows.

From room 1006 at the Standard, East Village, you see a white-faced clock overlooking a small triangular park. A sea-green dome ringed with small arched windows is partly blocked by a boxy rectangular building, faded and plain except for the cross on its south-facing wall. On the rooftop hangs a single line of laundry. Straight ahead is a building, wide and blank as a wall, that nobody seems to enter or exit.

If you don’t live in New York, you might not know the names of these buildings or their significance, how they function in the city, what they mean to its people. But this is the gift of being somewhere new, in a place that will never be home. Everything is defined by your first impressions. That sea-green dome, so out of place and time, might house things both ancient and futuristic—rusted astrolabes on the shelves, side by side with next generation iPads. The crucifix could be the final remnant of a failed church, the original cathedral demolished decades ago, replaced by a building full of a thousand cubicles. That white-faced clock, the brightest thing at night, may very well be the front of a crime-fighter’s headquarters or a supervillain’s lair. That line of laundry, winter-damp and flapping—those are the clothes of a dead man who had no loved ones left behind to gather them. And directly across, that building is lifeless as ever, but someone is inside, waiting to be glimpsed, you’re sure of it. All you need to do is wait. —Lysley Tenorio

Lysley Tenorio is currently the Paris Review Writer-in-Residence at the Standard, East Village.

What We’re Loving: Gremlin Jokes, Spiritual Paths, Sundae Ire

Jane Frelicher, Backgammon, 1982.

It’s been almost fifteen years since Akhil Sharma published his first novel, An Obedient Father. This terrible, improbably funny book—about a single mother forced to share an apartment with the father who raped her as a child—won Sharma a PEN/Hemingway prize, a Whiting Award, and praise from the likes of Jonathan Franzen and Joyce Carol Oates. (I remember because it was the first novel I had the honor of editing.) Now Sharma is back with Family Life, the tale of an Indian American boy coming of age in the shadow of a family disaster. It too is terrible and improbably funny, and is excerpted in this week’s New Yorker. With acid, deceptively artless prose and a faultless ear for dialogue, Sharma strips his characters bare from page one and dares us to love them in their nakedness. I cannot think of a more honest or unsparing novelist in our generation. —Lorin Stein

Michael Hofmann is the only translator whose work I would read no matter what he decided to English—if only I could keep up with him! In the excellent new issue of Asymptote, he tells a story about interviewing Wolfgang Koeppen in 1992, four years before the German novelist’s death. (“With my English reticence and youth, I met Koeppen halfway: in other words, we were both barely out of our shells.”) He also writes of the Joseph Mitchell–like silence that Koeppen fell into after the publication of Death in Rome (1954) and lauds the still-untranslated last book, Youth (1976)—giving us reason to hope he might be at work on an English version. The final remarks on Koeppen’s sentences—continually “sidestepping into freedom,” “scrupulously managed, supple, cadenced, sumptuously lexical, expressive prose”—double as a description of Hofmann’s own writing. —Robyn Creswell

Poetry’s January issue contains a thirty-page feature on Jane Freilicher: her artwork and her close friendships with a number of poets, among them Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and James Schuyler. The section is adapted from Tibor de Nagy Gallery’s wonderful exhibition, last summer, “Jane Freilicher: Painter Among Poets” (it’s currently on view at the Poetry Foundation, in Chicago). I remembered having glimpsed the show’s catalogue in Lorin’s office. I liberated it, and I’m not sure I’ll give it back. It’s like having a scrapbook made by the people whose work you most admire, and it shows that they had as good a time in one another’s company as you’d imagined. “Some little gremlins seemed to have popped loose in my idea factory and I think they may have been sent over from Koch’s brassiere factory,” writes Freilicher to O’Hara. And in what may be my favorite letter in the whole book, from Jane to Frank on a poem of his: “it just don’t seem to have that real low-down smelly sexy everyday Olympian quality your admirers depend upon.” —Nicole Rudick

“A so-called adult sundae is adult only in the sense that all the fun is gone, scoops arrayed stolidly in a row. True, the chocolate ice cream is spiked with Scotch and the cherries soaked with Pimm’s, but these come off as mostly medicinal. Hardly an incentive to grow up.” Ligaya Mishan’s review of the East Pole manages to be hilariously caustic without getting nasty: no mean feat. —Sadie O. Stein

I’d had Tracie Egan Morrissey’s “Inside the Rainbow Gulag: The Technicolor Rise and Fall of Lisa Frank” waiting patiently in a browser tab for more than a month; this week I finally read it. Frank is, as children of the nineties know, a kind of school-supplies doyenne: her company made the most unabashedly treacly notebooks, lunchboxes, and stickers ever to see a first grader’s cubby. As Morrissey writes, “Frank’s name alone conjures up a specter of koala bears clinging to rainbow-flavored ice-cream cones, neon tiger cubs frolicking with surfing penguins, and, of course, majestic unicorns prancing before a swirl of hearts and stars.” It’d never occurred to me that there might be a sordid story behind all this, but then again, how could the creator of such a lurid fantasy-world not be completely fucked up? Morrissey’s piece shows us the surreal animosity that ruled Frank’s Tucson, Arizona, headquarters. There’s screaming and cocaine and extramarital affairs, all of them drenched in garish colors. Throw in a couple murders and the story would have all the trappings of one of the more vicious Coen Brothers satires, like Burn After Reading. —Dan Piepenbring

As I get older and read more criticism and, thus, write less and less, I find myself turning again to Julia Cameron’s bestselling The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity (1992). Those for whom chirpy self-helpfulness tends to bring on spiritual and creative nausea will appreciate Cameron’s down-to-business exercises (the “Jealousy Map” is particularly illuminating), and perhaps find themselves clearing both physical and mental space for a visit from the Muse. —Rachel Abramowitz

A few years back, Paris Review contributor David Gordon published his debut novel, The Serialist. The book was satirical but also true to its crime-fiction roots. It was also really funny. Little did any of us, including Gordon himself, know that it was to become a huge success—in Japan. In the New York Times Magazine, Gordon recounts his “double life,” where “people toasted me and applauded my ability to eat with chopsticks or sign my name really big on a poster.” He adds, “It was as if I had fallen asleep and had a weird dream about my own book.” And, in a way, it is a dream, as his day-to-day life back in the States has not really changed. The “wonder” of another life also plays into Takashi Hiraide’s The Guest Cat, a novel I just completed in a blur of a few hours. Short and subtle, the book explores the lives of two writers who one day invite a neighbor’s cat into their home. The cat comes and goes as she pleases, but, as Hiraide observes, “was her coming to our house a return—a homecoming—or was it the other way around? Was home really over there?” —Justin Alvarez

Isn’t It a Lovely Day

From J. A. Sidey’s Alter Ejusdem, 1877, via the British Library.

The day of my thirtieth birthday dawned wet and cool. What started as a determined drizzle had settled, by late morning, into hard rain. This scuttled most of our plans, but my boyfriend and I were determined to fill the day with fun, and set off doggedly for Manhattan.

As any tourist knows, filling a rainy urban day can be a challenge; one generally ends up doing a lot of sitting around in restaurants drying off, drinking more coffee than planned (and this in turn creates new challenges). We did this. Our first umbrella blew out and we had to toss it. We took shelter in the Strand bookstore. Our second umbrella was pinched. We saw both Alexander McQueen’s show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and, back downtown, a documentary about Candy Darling. We bought a new umbrella from a bodega. Sometime between McQueen’s S/S ’05 Edwardian collection and Candy becoming the toast of Max’s back room, the rain turned torrential.

I was not distressed about leaving my twenties, and had never been prone to birthday blues, but around three P.M., my spirits began to flag. Our feet were very wet. We were standing under the overhang of the West Fourth Street subway station, and everyone looked miserable, either to be going out into the downpour or else to be leaving the downpour for a train car that would, without question, smell like steaming wet dog. McQueen was dead by his own hand; Candy Darling hadn’t even made it to thirty. I didn’t want to say anything to my boyfriend, who had been such a good sport throughout, but I could tell that he, too, was somewhat low.

And in that moment of desolation, I received the single best birthday gift ever given by one human being to another.

We were glumly unfurling our cheap little umbrella, preparing to venture out and maybe see another movie, when we were approached by a prosperous-looking middle-age Indian man in a beautiful, rain-spattered gray suit. He walked up to us, beaming.

“Will you give me your umbrella?” he asked blandly.

“What? No,” said my boyfriend, somewhat taken aback. “If you want one, you can buy them right there”—he indicated the vendor hawking black umbrellas for three dollars a few feet away—“but we need this one.”

The man’s grin did not abate. If anything, it widened.

“But I’m the baby!” he shouted. “You have to take care of the baby!”

And he bounded away.

As Fred Astaire would have said, rain or not, the sun was suddenly shining everywhere.

The Beetle and the Fly

From the original cover of Kafka’s Die Verwandlung, 1915.

I woke up one morning recently to discover that I was a seventy-year-old man. Is this different from what happens to Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis? He wakes up to find that he’s become a near-human-sized beetle (probably of the scarab family, if his household’s charwoman is to be believed), and not a particularly robust specimen at that. Our reactions, mine and Gregor’s, are very similar. We are confused and bemused, and think that it’s a momentary delusion that will soon dissipate, leaving our lives to continue as they were. What could the source of these twin transformations possibly be? Certainly, you can see a birthday coming from many miles away, and it should not be a shock or a surprise when it happens. And as any well-meaning friend will tell you, seventy is just a number. What impact can that number really have on an actual, unique physical human life?

In the case of Gregor, a young traveling salesman spending a night at home in his family’s apartment in Prague, awakening into a strange, human/insect hybrid existence is, to say the obvious, a surprise he did not see coming, and the reaction of his household—mother, father, sister, maid, cook—is to recoil in benumbed horror, as one would expect, and not one member of his family feels compelled to console the creature by, for example, pointing out that a beetle is also a living thing, and turning into one might, for a mediocre human living a humdrum life, be an exhilarating and elevating experience, and so what’s the problem? This imagined consolation could not, in any case, take place within the structure of the story, because Gregor can understand human speech, but cannot be understood when he tries to speak, and so his family never think to approach him as a creature with human intelligence. (It must be noted, though, that in their bourgeois banality, they somehow accept that this creature is, in some unnamable way, their Gregor. It never occurs to them that, for example, a giant beetle has eaten Gregor; they don’t have the imagination, and he very quickly becomes not much more than a housekeeping problem.) His transformation seals him within himself as surely as if he had suffered a total paralysis. These two scenarios, mine and Gregor’s, seem so different, one might ask why I even bother to compare them. The source of the transformations is the same, I argue: we have both awakened to a forced awareness of what we really are, and that awareness is profound and irreversible; in each case, the delusion soon proves to be a new, mandatory reality, and life does not continue as it did.

Is Gregor’s transformation a death sentence or, in some way, a fatal diagnosis? Why does the beetle Gregor not survive? Is it his human brain, depressed and sad and melancholy, that betrays the insect’s basic sturdiness? Is it the brain that defeats the bug’s urge to survive, even to eat? What’s wrong with that beetle? Beetles, the order of insect called Coleoptera, which means “sheathed wing” (though Gregor never seems to discover his own wings, which are presumably hiding under his hard wing casings), are notably hardy and well adapted for survival; there are more species of beetle than any other order on earth. Well, we learn that Gregor has bad lungs they are “none too reliable”—and so the Gregor beetle has bad lungs as well, or at least the insect equivalent, and perhaps that really is his fatal diagnosis; or perhaps it’s his growing inability to eat that kills him, as it did Kafka, who ultimately coughed up blood and died of starvation caused by laryngeal tuberculosis at the age of forty. What about me? Is my seventieth birthday a death sentence? Of course, yes, it is, and in some ways it has sealed me within myself as surely as if I had suffered a total paralysis. And this revelation is the function of the bed, and of dreaming in the bed, the mortar in which the minutiae of everyday life are crushed, ground up, and mixed with memory and desire and dread. Gregor awakes from troubled dreams which are never directly described by Kafka. Did Gregor dream that he was an insect, then awake to find that he was one? “‘What in the world has happened to me?’ he thought.” “It was no dream,” says Kafka, referring to Gregor’s new physical form, but it’s not clear that his troubled dreams were anticipatory insect dreams. In the movie I co-wrote and directed of George Langelaan’s short story The Fly, I have our hero Seth Brundle, played by Jeff Goldblum, say, while deep in the throes of his transformation into a hideous fly/human hybrid, “I’m an insect who dreamt he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over, and the insect is awake.” He is warning his former lover that he is now a danger to her, a creature with no compassion and no empathy. He has shed his humanity like the shell of a cicada nymph, and what has emerged is no longer human. He is also suggesting that to be a human, a self-aware consciousness, is a dream that cannot last, an illusion. Gregor too has trouble clinging to what is left of his humanity, and as his family begins to feel that this thing in Gregor’s room is no longer Gregor, he begins to feel the same way. But unlike Brundle’s fly self, Gregor’s beetle is no threat to anyone but himself, and starves and fades away like an afterthought as his family revels in their freedom from the shameful, embarrassing burden that he has become.

Jeff Goldblum in Cronenberg’s The Fly, 1986.

When The Fly was released in 1986, there was much conjecture that the disease that Brundle had brought on himself was a metaphor for AIDS. Certainly I understood this—AIDS was on everybody’s mind as the vast scope of the disease was gradually being revealed. But for me, Brundle’s disease was more fundamental: in an artificially accelerated manner, he was aging. He was a consciousness that was aware that it was a body that was mortal, and with acute awareness and humor participated in that inevitable transformation that all of us face, if only we live long enough. Unlike the passive and helpful but anonymous Gregor, Brundle was a star in the firmament of science, and it was a bold and reckless experiment in transmitting matter through space (his DNA mixes with that of an errant fly) that caused his predicament.

Langelaan’s story, first published in Playboy magazine in 1951, falls firmly within the genre of science fiction, with all the mechanics and reasonings of its scientist hero carefully, if fancifully, constructed (two used telephone booths are involved). Kafka’s story, of course, is not science fiction; it does not provoke discussion regarding technology and the hubris of scientific investigation, or the use of scientific research for military purposes. Without sci-fi trappings of any kind, The Metamorphosis forces us to think in terms of analogy, of reflexive interpretation, though it is revealing that none of the characters in the story, including Gregor, ever does think that way. There is no meditation on a family secret or sin that might have induced such a monstrous reprisal by God or the Fates, no search for meaning even on the most basic existential plane. The bizarre event is dealt with in a perfunctory, petty, materialistic way, and it arouses the narrowest range of emotional response imaginable, almost immediately assuming the tone of an unfortunate natural family occurrence with which one must reluctantly contend.

Stories of magical transformations have always been part of humanity’s narrative canon. They articulate that universal sense of empathy for all life forms that we feel; they express that desire for transcendence that every religion also expresses; they prompt us to wonder if transformation into another living creature would be a proof of the possibility of reincarnation and some sort of afterlife and is thus, however hideous or disastrous the narrative, a religious and hopeful concept. Certainly my Brundlefly goes through moments of manic strength and power, convinced that he has combined the best components of human and insect to become a super being, refusing to see his personal evolution as anything but a victory even as he begins to shed his human body parts, which he carefully stores in a medicine cabinet he calls the Brundle Museum of Natural History.

There is none of this in The Metamorphosis. The Samsabeetle is barely aware that he is a hybrid, though he takes small hybrid pleasures where he can find them, whether it’s hanging from the ceiling or scuttling through the mess and dirt of his room (beetle pleasure) or listening to the music that his sister plays on her violin (human pleasure). But the Samsa family is the Samsabeetle’s context and his cage, and his subservience to the needs of his family both before and after his transformation extends, ultimately, to his realization that it would be more convenient for them if he just disappeared, it would be an expression of his love for them, in fact, and so he does just that, by quietly dying. The Samsabeetle’s short life, fantastical though it is, is played out on the level of the resolutely mundane and the functional, and fails to provoke in the story’s characters any hint of philosophy, meditation, or profound reflection. How similar would the story be, then, if on that fateful morning, the Samsa family found in the room of their son not a young, vibrant traveling salesman who is supporting them by his unselfish and endless labor, but a shuffling, half-blind, barely ambulatory eighty-nine-year-old man using insectlike canes, a man who mumbles incoherently and has soiled his trousers and out of the shadowland of his dementia projects anger and induces guilt? If, when Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed right there in his bed into a demented, disabled, demanding old man? His family is horrified but somehow recognize him as their own Gregor, albeit transformed. Eventually, though, as in the beetle variant of the story, they decide that he is no longer their Gregor, and that it would be a blessing for him to disappear.

When I went on my publicity tour for The Fly, I was often asked what insect I would want to be if I underwent an entomological transformation. My answers varied, depending on my mood, though I had a fondness for the dragonfly, not only for its spectacular flying but also for the novelty of its ferocious underwater nymphal stage with its deadly extendable underslung jaw; I also thought that mating in the air might be pleasant. Would that be your soul, then, this dragonfly, flying heavenward? came one response. Is that not really what you’re looking for? No, not really, I said. I’d just be a simple dragonfly, and then, if I managed to avoid being eaten by a bird or a frog, I would mate, and as summer ended, I would die.

This essay appears as the introduction to Susan Bernofsky’s new translation of The Metamorphosis.

David Cronenberg is a Canadian filmmaker whose career has spanned more than four decades. Cronenberg’s many feature films include Stereo, Crimes of the Future, Fast Company, The Brood, The Dead Zone, The Fly, Naked Lunch, M. Butterfly, Crash, A History of Violence, and A Dangerous Method. His most recent film, Cosmopolis, starred Robert Pattinson and was an adaptation of Don DeLillo’s 2003 novel. Consumed, his first novel, will be published in September.

A Resident of Sipswich, MA

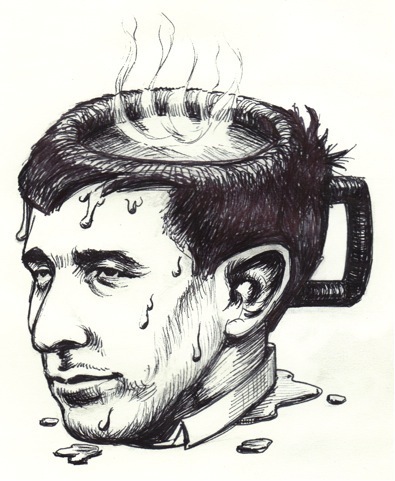

This week, we’re presenting Timothy Leo Taranto’s illustrated author puns. Today, the final entry:

Tim Taranto hails from Upstate New York and attended Cornell. In addition to The Paris Review Daily, his work has appeared on the Rumpus and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Tim lives in Iowa City, where he is studying fiction at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Cinema’s Most Realistic Psychopath, and Other News

Still from No Country for Old Men, 2007.

The Gordon Lish Bot is trolling Twitter, demanding that writers craft their 140 characters more meticulously. It’s fine invective, but masochists will wish for the sting of the real thing.

Science has cast its formidable gaze on movie psychopaths, declaring No Country for Old Men’s Anton Chigurh the most “realistic.” And yet no one, living or dead, has ever dared to sport that haircut.

The curiously robust posthumous life of V. C. Andrews.

Lewis Carroll’s “Wise Words About Letter-Writing” still apply in the lawless land of electronic mail.

This introduction to Korean alphabet art is full of colorful translations: “Using a dustpan, the black mountain is split to form letters, and then the canvas is propped up vertically, and stains caused by gravity are left behind.”

January 16, 2014

A Creator of Inwardness

Photograph by Peter Hujar.

Susan Sontag was born today in 1933.

INTERVIEWER

Is it old-fashioned to think that the purpose of literature is to educate us about life?

SONTAG

Well, it does educate us about life. I wouldn’t be the person I am, I wouldn’t understand what I understand, were it not for certain books. I’m thinking of the great question of nineteenth-century Russian literature: how should one live? A novel worth reading is an education of the heart. It enlarges your sense of human possibility, of what human nature is, of what happens in the world. It’s a creator of inwardness.

—Susan Sontag, the Art of Fiction No. 143

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers