The Paris Review's Blog, page 748

January 16, 2014

West Side Story

Image: Design of Signage

I like my psychiatrist, but I often find that occupying fifty minutes with an account of my tedious life feels like a high price to pay for responsible prescription.

“Do you try to make him laugh?” my dad asked, when he picked me up from my first-ever appointment. “Do you want to be his favorite patient?” (My dad visited a therapist briefly in the 1970s, hence his expertise.) I explained loftily that this was a medical situation and not like that at all, and that the doctor had been amazed that with my family history I had never been treated before. Then I admitted that yes, of course I wanted to be his favorite.

“When I saw my guy,” said my dad, “I sang to him.”

And he began to sing, very beautifully, to the tune of the Love Story theme,

Dog food is the king

I wish it weren’t but I can’t do anything

It’s so damn good it even makes the sparrows sing

And grown men weep and angels cry.

There was a moment of silence.

“What did he do?” I asked.

“He made me turn around so I wasn’t playing to his reaction all the time and had to actually engage.”

* * *

“You’re an M.D.,” I once said to my doctor. “You spend your days at the hospital”—I happened to know this—“and presumably deal with really unwell patients, then you come here and listen to people like me, and our nonproblems. You must despise us so much. I would. Do you despise us?”

“No,” he said, making a note.

* * *

I have been to the psychiatric ward at that particular hospital, visiting friends and loved ones, a number of times this year. Each time I sort of hoped I would run into my doctor. I wouldn’t have given him away, if I had. I was planning on a quick, roguish wink. It would have been our secret.

Maybe I have unrealistic expectations for such encounters. The first time I visited a psychiatric ward was in college. A friend was suffering from depression and campus health services had sent her to the university hospital for a brief stay. The nurse went to fetch my friend and instructed me to wait for her in the sort of group lounge where most visitors congregated. And there, sitting on the couch and watching a Terminator film, was a girl who lived in my dorm. I did not know this girl terribly well—although she was distinctive for always sporting a Henry Higgins–style tweed hat—but I did know that she was supposedly at home in Hawaii on some extended vacation, because people had been vocally envying the weather she must be enjoying.

She was wearing a hospital gown, and the tweed hat. She gave me a wink, said, “Mum’s the word,” and turned back to the movie.

* * *

Only once has a fellow patient engaged with me in the waiting room of my psychiatrist’s office. It was a teenage boy, and when I greeted him, he launched into an excitable monologue about the age and architectural style of the building in which we were standing, the architectural tropes of its era, and Manhattan architecture generally.

“Daniel, that’s enough,” said his father gently, and then, turning to me, “I’m sorry.”

“No, it’s fine,” I said.

He Did, After All, Attend the Tuskegee Institute

A Few Exits Back on the Information Superhighway

Thanks to the unflagging efforts of Archive.org’s Wayback Machine—which has had, since 1996, the unenviable task of preserving as much of the Internet as possible—we recently exhumed the original version of our Web site. Better still, we rediscovered these two videos of our late founding editor, George Plimpton. In the grainy, hypercompressed format that marked mankind’s earliest forays into digital recording, he helpfully explains where you are and what you might do here.

These were the days of 28.8k modems, of CompuServe and Netscape, when the word multimedia carried a frisson of ultramodern potential. As you watch, you can practically hear the bleat and drone of the dial-up connection. That’s technology, baby. These videos are not high definition. They are virtual fossils. Handle them with care.

What with Moore’s Law and all, designs that should feel merely outdated are already full-on quaint. More than anything, our old site reminds us that the Internet was once more literally construed as a location, with “sites” portraying themselves as places for weary travelers to rest their heads:

The Internet is frontier territory for us, and we’re excited about being here. For those of you who know The Paris Review, this electronic forum should offer some new and, we hope, interesting ways to interact with the magazine. For those of you meeting us for the first time, please accept our invitation to browse around … Come to our “offices” as often as you like. We’ll try to keep things fresh.

It’s difficult to conceive of this site as an office today, or even as an “office.” We are, however, still dedicated to keeping things fresh here—wherever here may be.

Peace Reigns Throughout the Land, and Other News

Stained glass window, Denis and Saint Sebastian Church, Kruft, Germany. Photo: Reinhardhauke, Wikimedia Commons.

Great news: we’re living in the most peaceful era* in human history!

“To hell with Gatsby’s green light!” Why we should stop teaching novels to high school students.

Shelley Jackson is, “weather permitting,” inscribing a story entirely in snow.

One way to save a failing bookshop: beg people on Facebook to come spend money there.

Forget Paris. Nantes, a city “situated in the estuary of the Loire,” is where it’s at.

*persistent, intractable religious hostilities notwithstanding

January 15, 2014

Move Over, Big Town

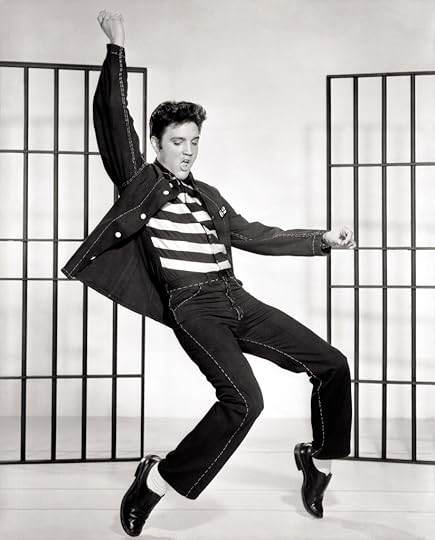

More calculated than you’d think. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Last night, a circa-1877 water main burst on Fifth Avenue near East Thirteenth Street, resulting in substantial flooding and, one imagines, a grueling night for any number of MTA workers. Reports the New York Times on the City Room blog,

Basements were flooded when it cracked, but there were no injuries, said Michael Parrella, a Fire Department spokesman.

Fifth Avenue remains closed between 14th and 12th Streets. The break opened up a big hole in Fifth Avenue that repair crews were working on.

Buildings along Fifth Avenue from 14th to 12th Streets were without water this morning, the Department of Environmental Protection said.

A reader reported that buildings on 10th Street also remained without water.

The A, C, E, B, D, F, M, and Q trains all had to be rerouted, so needless to say the morning commute was disrupted for a lot of people and, if you read Twitter, was basically the Worst Thing That Has Ever Happened. People were inconvenienced, and the world needed to know.

Easy for me to say. Now that I am working from home, I don’t need to be on the subway by nine anymore—and believe me, I understand how crushing it can be to watch six trains stream past, knowing all the while that the first to open its doors will be packed beyond the dictates of civilization, sanitation, or fire safety. Usually in such situations there is a hapless MTA representative at the station who fields the queries of the baffled tourists and furious New Yorkers who have all been Personally Inconvenienced by any such mishap. If you’re really lucky, you’ll have both an entire preschool class and a high school field trip waiting on the platform with you.

As it happened, I did need to be on the subway early this morning. But I decided to hoof it the two miles downtown. It wasn’t, in fact, the scrum of angry commuters, or the cranky children and their poor, harassed minders, or even the prospect of the long wait that made my decision for me. It was the “Jailhouse Rock” guy.

The “Jailhouse Rock” guy is normally one of my favorite buskers. He sings only one song—“Jailhouse Rock”—and he sings it on an interminable loop, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, ad infinitum verses same as the first. He has a guitar which he strums enthusiastically and randomly with one hand, while his fret hand lies idle. I have heard people literally groan when they enter the station and realize he is our morning’s entertainment. Once a crazy woman sort of went off on him. He doesn’t care.

Today I couldn’t do it.

But who cares? We all know what it is to feel imposed upon by musicians during a harried commute. (Likewise, it goes without saying that subway music can be revelatory and interesting. Who at Eighty-Sixth Street wasn’t moved last week by that vet in a wheelchair playing “The Weight” while half the platform joined in on the harmonies?) I’m just another person among thousands, giving money or not giving money, depending on my mood and my finances, on some level thinking of these people with their real lives as somehow a passing soundtrack to my life.

Louis C.K. has a bit about self-absorption. “I can’t believe this is happening to me, ME!” everyone thinks. Because a 127-year-old pipe burst, and hundreds of people had to wade in freezing water overnight fixing it, and others were probably scrambling to prevent everyone being electrocuted, and still others had to reorder all the subway routes, and a man who may or may not be mentally ill was singing a song I didn’t feel like hearing, I walked forty blocks. As the novelty tee would have it, COOL STORY, BABE. NOW MAKE ME A SANDWICH.

Have you seen Jailhouse Rock? Elvis plays a construction worker who accidentally kills a man in a bar brawl, gets one to ten in the state pen for manslaughter, and is taught to play guitar by his cellmate. I won’t get into the whole plot, but suffice it to say, his character encounters a lot of rejection, a lot of class snobbery, and a lot of humiliation. When he does find success, he becomes so self-absorbed that he loses everyone in his life. And “Jailhouse Rock”? It’s a pop song his character writes in a cynical attempt to make it big. The stylized cell-block dance sequence you have seen is in fact a number the Elvis character performs on a Bandstand-style TV show, rather than a lighthearted musical number from a similarly-toned film. The original title was The Hard Way.

Although box-office sales were healthy, Jailhouse Rock received mixed reviews; several critics apparently didn’t like that a film for young people featured an antihero. During filming, one of Presley’s dental caps got lodged in his lung and he had to be hospitalized. Costar Judy Tyler was killed in a car crash two weeks after the film wrapped, and Elvis was so depressed that he didn’t attend the premiere.

As they say, everyone’s a critic. The MTA reports that service has mostly resumed, with delays. No one got a tooth in his lung.

Oh, and for the first time, today, that guy wasn’t playing “Jailhouse Rock.” He was playing “Tutti Frutti.”

Dramatic Needs

Trouble Man, Marvin Gaye’s 1972 soundtrack to the film of the same name.

The way the story most often gets told, Marvin Gaye with What’s Going On (1971) liberated himself from Motown’s formulaic method of music-making and achieved total artistic independence, whereupon the music—if not, to be sure, the man himself—went on to live happily ever after. But the story gets told incompletely, because What’s Going On was only the start of it—it was how Gaye leveraged the potential for his independence, but it wasn’t how he ventured out and completely seized that independence. To tell that story, you have to tell about Trouble Man.

It’s a story that can now be told more elaborately, with a wonderful fortieth anniversary reissue of the original album, complete with some newly released material and a supplementary booklet. Trouble Man is absolutely sui generis within the Marvin Gaye canon for being not only a blaxploitation film soundtrack—the only film score he would ever do—but for being jazz-based and largely instrumental. The booklet does a commendable job articulating Trouble Man’s importance, while the artifact itself sings, as always, with perfect eloquence to the same thing. Except that now it sings even better.

The way it happened is that Gaye had relocated from Detroit to LA to put some finishing magic on What’s Going On, and, once that was completed, began making his next moves. He made them in several directions. Before getting down to work on Trouble Man, as Andrew Flory informs us in his excellent accompanying essay, Gaye recorded a whole handful of terrific songs that would eventually appear elsewhere: “You’re the Man,” “Going Home,” “Where Are We Going” [sic], “The World Is Rated X,” and a version of “Symphony” with some placeholder lyrics. One last thing he did before getting down to work on Trouble Man is an album of duets with Diana Ross.

Ross, as it happens, was herself in the midst of a musical film project, the Billie Holiday biopic Lady Sings the Blues (1972), in which she played lead. Comparing her project with Gaye’s tells us everything we need to know about the difference in their respective sensibilities. Both movies paid tribute to jazz traditions of the recent past, but there is where the similarities squarely ended. Where Ross settled for merely exhuming jazz, Gaye took the altogether more difficult and dangerous leap of actually rejuvenating it, by proving that jazz's arrangements could thrive within the context of funk's emphatic rhythms and instrumentation.

Recently turned on to the Moog by Stevie Wonder, who actually gave him one as a gift, Gaye in Trouble Man used his new synthesizer with the avidity and adventure of a child who’s just discovered a new toy. “I consider Mr. Moog an absolute genius,” he told his biographer David Ritz, “and felt grateful to him all the while I was working [on Trouble Man].” Ritz would write that Gaye indeed considered the project “a large canvas on which he painted his newly discovered Moog figures,” and Flory in his essay gives the Moog plenty of space too. On this most instrumental of albums, Gaye played other instruments as well. A Motown session-drummer in his early days and a talented pianist, Gaye always did have a knack for percussion. Whenever, on this album, you hear foot stomps, finger snaps, hand claps, and tambourines, you can be fairly confident that you’re listening to Gaye himself.

Gaye worked with both rhythm sections and orchestras, depending on what type of song was needed, be it a funked out bluesy soul number or a cool-jazz/orchestral stretch of film score meant to accentuate onscreen action. He composed the whole thing himself, even if it meant, for the scored sections, humming and singing out pieces of music to be transcribed by others. The film band sessions, writes Flory,

were recorded in a large film studio using only a few microphones and full battery of traditional instruments. Most cues were cut in the first take, and there were no overdubs during these sessions. Nearly three hundred separate cues were recorded, ranging from ten-second interludes to passages of several minutes. In the tradition of the film industry, the material from these sessions was viewed as a set of building blocks for what would later become the soundtrack. The actual score was edited heavily in order to serve the dramatic needs of the film.

The great musical offering of this rerelease—which otherwise features mostly alternate takes that differ little from the takes that made the original LP—is to provide many of these interludes and passages for the first time to those who’ve never seen the movie. They have titles like “Stick Up,” “Pool Hall,” “Getting Pete,” “Police Break In,” and “Bowling Alley Parking Lot.” In their languid-but-urgent, hauntingly evocative cool-jazz trances, interspersed with chillingly dissonant brass interruptions, these found musical moments remind one of nothing so much as Bernard Herrmann’s great 1976 score for Taxi Driver (which may, come to think of it, have been influenced by Gaye’s score). They prove, too, just how much good music can accumulate and hide out in the crevices of a movie one had never seen.

I’m far from alone in never having seen Trouble Man. When I recently and finally did sit down to the entire thing, I was not sorry for this neglect. It’s not much better or worse than most of the blaxploitation movies to come out of the era, but this should by no means be taken as endorsement. The great contribution of those films, though, was to offer, in their nihilistic social irresponsibility, a license to the musicians who scored them to be darker and more pessimistic than they could be in other contexts, and, in the doing, to engage a broader range of human experience. Curtis Mayfield; Isaac Hayes; James Brown; Bobby Womack; Sun Ra; Barry White; Earth, Wind & Fire; the Dells; Quincy Jones; Booker T. & the MGs; Willie Hutch; Aretha Franklin; Gladys Knight and the Pips—it seems every major soul musician from the era entered the blaxploitation sweepstakes at least once, and many of them more than once.

One big exception is Stevie Wonder, who, we’ll recall, had given Gaye the Moog that inspired so many of Trouble Man’s greatest moments. Wonder pedaled in a brand of social consciousness that was far too literal and sanctimonious to accommodate the message of these movies and their violence. It was an opportunity missed. All we have to do is look at what Gaye was able to do. With songs like “Main Theme from Trouble Man,” “Don’t Mess with Mr. T,” “Life Is a Gamble,” and “Poor Abbey Walsh,” Gaye was able to communicate something about street life far more powerful and horrible and, ultimately—because of the quality of its music—redemptive, than he’d done in songs like “Inner City Blues,” “The World Is Rated X,” and “Where Are We Going,” so bluntly literal in their agitprop.

Gaye never did do another film score, although he certainly wanted to, or said he did. But what he gave us is enough, as this repackaging both reminds and reinforces. In addition to Flory’s excellent flagship piece, there are mini-essays on the contributions of the arranger and the saxophonist (Dale Oehler and Trevor Lawrence), as well as testimony from Joni Mitchell, Christian McBride, and Lenny Kravitz. There is an essay by Cameron Crowe. There is great album art from inside the original release, and, in a nice touch, photographs of the labeled master tapes. It’s a smart package that will hopefully bring new attention to a bafflingly neglected masterpiece.

Following Trouble Man, Gaye immediately continued his artistic evolution, declining to tour and instead going back into the studio, to record Let’s Get It On (1973). That album would introduce a whole new caliber of raw sexuality to popular music. It was soon followed by I Want You (1976), a more subdued, subtle, and sophisticated, but ultimately more powerful, testimony to Gaye’s undying eroticism. I Want You has moments as haunting as the best of Trouble Man. Here, My Dear (1978) was a culmination of all the musical technique Gaye had demonstrated in the ‘70s: the multiple vocal-track recording, the funk instrumentation, the hauntingly poetic and personal lyrics—all of it done at double-album length in answer to a court-ordered demand for alimony on behalf of his first wife, Anna (and the sister of Motown founder Berry Gordy, who actually released the album). It was not the last great music Gaye would ever make, but it was the last time he would make an entire album’s worth of it.

But it doesn’t matter that he never did another soundtrack, because he did this one. Why he did it is a far more compelling question than why he never tried following it, or why nobody invited him to try. In his catalog, it sits squarely between What’s Going On and Let’s Get It On, chronologically and symbolically, halfway between social consciousness and eroticism. It is both those things, without having to be, entirely, either of them. It occupies the subtle center between two extremes, cool enough to keep its own company as an unclassifiable miracle of melancholy mood-music.

And that’s not even the most impressive gamble Gaye made with Trouble Man. The most impressive gamble he made was in—at this precarious juncture when he was expected to adequately follow What’s Going On, already a classic—answering with the score for a film. And the score for a blaxploitation film, at that. And, what’s even more, a largely musical score for a blaxploitation film, thereby subordinating his greatest asset of all: his voice. It’s at once an act of great humility and of sheer arrogant defiance, as if he just knew his voice was so purely dynamic a means of musical expression that, merely by sublimating its energies and rechanneling them, it could transform into an entirely new mode of musical transcendence.

Lary Wallace is an eccentric at large and a feature writer for Prestige magazine. He last wrote for the Daily about the Jim Thompson House in Bangkok.

Two-Time Winner of the National Borscht Award

Read Chekhov for a More Empathetic 2014, and Other News

He’s here to help. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

As January reaches its halfway mark and resolutions begin to waver, how is one to guarantee a year of self-betterment? By reading Chekhov.

The Argentine poet Juan Gelman is dead, at eighty-three.

What do Willy Loman and Gregor Samsa have in common? They’re both drummers.

Apple’s new ad for the iPad Air is full of leaden rhetoric about the glory of the humanities. Robin Williams does the voice-over, quoting himself from Dead Poets Society: “We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion.” And only with the latest and sleekest in consumer electronics can that passion find its truest expression.

Alaric Hunt, the recent winner of a detective-novel writing contest, penned his book in prison, where he’s serving a life sentence for murder.

January 14, 2014

To Whinny, Perchance to Dream

It’s Nice That, the art and design site, directed our attention to this assortment of vintage Ladybird Books, a British children’s imprint known in its heyday for pocket-size hardbacks on an exhaustive array of topics. Your average Ladybird is accessible, vividly and impeccably illustrated, and almost heartbreakingly earnest. See, for example, 1951’s The Discontented Pony, which traffics in a kind of postwar ennui and Weltzschmerz unknown to the youth of today.

This pony story tells of a very discontented pony named Merrylegs. Even though having everything a little pony needs—a field to run about in, a kindly farmer owner, and farmyard friends Daisy and Squeaker—Merrylegs still begins to feel discontented with his lot in life.

We know the feeling, Merrylegs. We know the feeling.

Ladybirds, also the subject of a recent BBC documentary, tend to bring out the collector’s impulse—they’re legion, they’re handsomely made, and they speak to the tastes of a bygone era, so of course you’ll want to own them all. It’s worth perusing the whole Ladybird corpus, actually. Some gems, in no particular order:

Man and His Car

Strawberries and Cream – The Adventures of Wonk

Learning About Heraldry

People at Work – In a Big Store

What to Look for Inside a Church

The Public Services – Gas

The Story of Clowns

The Garden Gang – Sheila Shallot and Benny Broad Bean

In the Train with Uncle Mac

Sin-Eaters

Photo: woodenmask, via Flickr

“Please don’t confront me with my failures,” sang Nico. “I have not forgotten them.” I can sympathize. Said failures are particularly difficult to forget when they sit glowering at you from your refrigerator. I have often pitied noncooks who will never know the gratification of perfecting a recipe or the sense of achievement that comes from transforming disparate ingredients into something nourishing and pleasurable. But by the same token, these people will never know the heartbreak of a recipe gone wrong.

In her classic essay collection More Home Cooking, Laurie Colwin writes of attempting to make a custard in an inadequately equipped rental-house kitchen. When the mixture curdled, “I remember flinging the pot into the sink and flouncing out of the house in tears, which I wept bitterly in a pine wood surrounded by clavaria and Indian pipes.”

My mother recalls a similar incident from her childhood in Palo Alto. Her own mother, never the most confident of cooks, somehow screwed up a lemon-meringue pie (there are many components to screw up) and, most uncharacteristically, hurled the misshapen pie out the window in a fit of tearful frustration. To this day, says my mother, the memory of rushing out into the yard and gobbling down the offending pastry off the grass with her father and brother remains one of the most thrilling of her early life.

To the noncook, these reactions probably seem excessive. But anyone who has gone through the process of inspiration, planning, shopping, and cooking understands the sense of total emptiness that accompanies such disappointments. After all, if cooking and feeding are the ultimate in social bonding and expressions of love—and we’re constantly being told such things—then these failures strike at something deep. You’re bad at love. And it’s almost worse when you’re surrounded by people who don’t comprehend your distress, who don’t understand what could have been, and who, worst of all, think whatever they’re eating is perfectly okay. More than once I have sat tight-lipped and miserable through a dish gone wrong—the grotesque Braised Lamb Shank of 2011 springs to mind—while my guests chowed down around me, uncritical and kind and infuriating.

Yesterday I made a tomato pie. Let it be said that, even at its best, tomato pie is a pretty revolting concoction: the classic formulation (most trace their roots back to James Beard) involves a biscuit crust, sliced tomatoes (canned out of season), grated cheddar, and a layer of mayonnaise. It sounds awful, but, when well prepared, it can be satisfying in a particularly Southern register. It’s not something I serve to guests (not anymore, I mean; I did once, in college) but it is cheap to make, and I figured it would serve as my week’s main fodder.

It’s not a particularly tricky dish to prepare, although between the making of the biscuits, the messy slicing of canned tomatoes, and the grating of cheese, a lot of dishes get used up. I fixed it as I always have, being careful to make allowances for my inaccurate oven, and, while it baked, was filled with the sense of well-being that comes from knowing your week’s meals are taken care of.

Was it the baking powder I used? The on-sale brand of canned tomato? The fact that I substituted a few tablespoons of yogurt for some of the milk? I don’t know. Sometimes luck deserts you. Just as there are periods where everything one cooks turns out well, on other occasions everything you touch is subtly off. Something astrological, perhaps. (My day’s horoscope, while belligerent, was inconclusive: “Don’t listen to those who counsel caution. The only reason they don’t want you to do anything adventurous is because they are worried it will make them look bad. And they’re right, it will—which is all the more reason to do it.”)

All I know is that my tomato pie was, and remains, one of the most disgusting things I have ever put in my mouth. It tastes … strange. Sinister, even. As if somewhere there’s a Dorian Gray tomato pie swanning around delighting people while this one putrefies under the weight of its misdeeds.

As of this writing, I have eaten it for three successive meals. I have tried it hot (awful) and cold (even worse). I have gulped water after every acrid, metallic bite and tried dousing it with vinegar and hot sauce.

Needless to say, it is enormous. Yes, I could throw it away. But it is too soon. Part of this is thrift; I planned to eat this abomination for days, and I will not give in and buy more groceries this early in the week. Part of it is willful self-delusion. I keep thinking that it couldn’t possibly be as bad as I remember. But most of it is pure masochism; a part of me feels I must be punished for my failure, or at least experience the guilt of staring at it every time I open the fridge.

I checked out today’s Sally Brompton to see what the stars had to say, tomato pie–wise. My worst fears were confirmed. “Over the next few days it will feel like you have turned a corner, that better days are coming. They probably won’t arrive for a few weeks yet but because you know they are on their way you can start making plans.” As I suspected, the pie and I are locked in a fierce, sick battle of wills. We will be living together for a very long time.

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers