The Paris Review's Blog, page 740

February 7, 2014

Coming of Age

Valenciennes lace of Ypres, 1875

The summer before I started college, I worked part-time in an antique linens shop in an East Coast vacation town. The owner, Theresa, was a warm, elegant woman who taught me not just how to do bookkeeping and how to tell the difference between point lace and Valenciennes, but a great deal about how to treat other people, too.

The rest of the time, I worked as a waitress at a nearby restaurant. My fellow employees included a shifty-eyed Hare Krishna named Heather, a bartender called Kenny who liked to try to shock me, and a thirtysomething bodyworker, Julia, who had the unfortunate habit of telling people on the slightest pretext that she had attended “a little school in New Haven.”

At the linens shop, I helped iron and fold the stock and assisted customers. Mostly, Theresa and I would talk: about her family leaving Havana after the revolution; about the history of the town; about her dashing husband and how they met when she was a receptionist at a clinic. (He’d had a dislocated shoulder and she let him jump the line.) “Always spend more on flowers than on food,” she once told me. “Good for the soul, better for the waistline.”

My sole romantic prospects that summer were the handsome, perpetually hungover Irishman who did odd jobs for Theresa and sometimes invited me to beach bonfires—I never went—and a busboy at the restaurant who would occasionally tail me home. After I told him I didn’t want to go out with him, he started leaving wet dishtowels on the seat of my bicycle. I couldn’t help feeling this was poor form.

I spent a great deal of time with Theresa. She taught me how to mix drinks and which birds liked which seed and how to alter my own clothes and how to make bouquets last. These were the happiest times of my summer.

Heather told me it was obvious I needed to do more drugs. Kenny said it was obvious I needed to get laid.

Julia, lately of New Haven, decided to take me under her wing. Like everyone else, she considered me extremely uptight.

“I have things to tell you,” she announced one day as we were filling the salt shakers, “that I think will really broaden your horizons. But you’re not ready to hear them yet.”

“Okay,” I said.

“All, right, I’ll tell you one thing,” she said five minutes later. “When I was nineteen, I traveled around the country in an RV with a forty-seven-year-old midget. We were lovers. In that summer, I learned more about myself, my body, and the world than I had in two years at a certain little school in New Haven.”

“Wow,” I said lamely.

I told Theresa about all these doings. “I am universally considered uptight,” I told her glumly.

She was silent for a moment, and then recited,

In youth, it was a way I had,

To do my best to please.

And change, with every passing lad

To suit his theories.

But now I know the things I know

And do the things I do,

And if you do not like me so,

To hell, my love, with you.

It was, of course, Dorothy Parker. And she was, of course, absolutely right.

A Gun and a Guitar

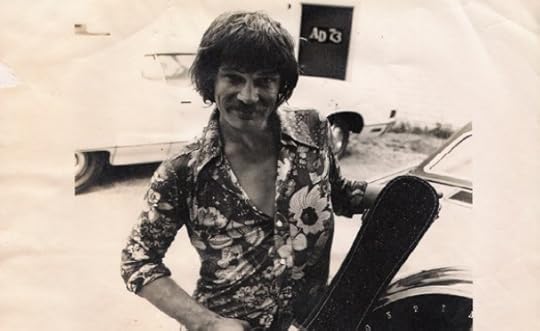

Jerry McGill: Sun Records artist, Memphis fixture, and “crazy sonofabitch.”

Photo: Randall Lyon, Jim Lancaster

Jerry McGill by the numbers, hazy as they may be: He cut one 45 for Sun Records (the rockabilly “Lovestruck,” with a backing band that included Charlie Rich). Years later, in the backseat of a limousine in Memphis, he cowrote one more song with Waylon Jennings. Shot at least three bullet holes into the ceiling of the Sam Phillips Recording Studio, where they still remain. Racked up nearly a hundred arrests. Assumed six aliases. Disappeared for twenty-five years—and ultimately reemerged, at the behest of filmmaker Paul Duane, to collaborate on Very Extremely Dangerous, a documentary about the tornadic trajectory of his life. In January, Dangerous was shown at Brooklyn’s Wythe Hotel, accompanied by a reading from Memphis writer-producer Robert Gordon, whose films will screen this month.

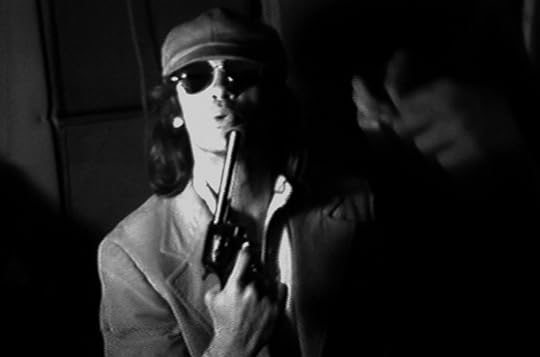

Flash back forty years, to the dimly lit bars, back rooms, and late Delta nights traversed by William Eggleston with his Sony Porta Pak, an early video camera. “It was back when everyone liked quaaludes. ‘Let’s get down,’ ” narrates Eggleston in his cinema verité of that era, 1974’s Stranded in Canton. His voice trails off into the sound of a shot fired and then Jerry McGill’s face jumps into the frame, wild and practically translucent. McGill has the looks of Mick Jagger, the constitution of Keith Richards, and the heart, it would seem, of a snake. His eyes masked in sunglasses, he grins in the dark, lunges, thrusts the barrel of his gun to the head of another man, and holds it there.

That scene still haunts. Rachel Kushner, in a portfolio of her visual inspiration for The Flamethrowers published in the Winter 2012 issue of The Paris Review, included a still of McGill from the film. The same screen capture accompanied McGill’s death notice in the Memphis Commercial Appeal last spring. It was seeing that gunplay scene and reading about McGill’s exploits in Gordon’s It Came from Memphis that inspired Duane to seek out the elusive, felonious musician.

In the midseventies demimonde of Memphis, things had a way of becoming totally and suddenly unhinged, and McGill was frequently the author of their unhinging. As Waylon’s vagabond and oft-arrested rhythm guitarist—prone to performing in disguise when the alias he then toured under, Curtis Buck, did not offer sufficient protection—McGill arguably out-outlawed the Country Outlaw himself. “Curtis Buck was a crazy sonofabitch and he ran around with me,” Jennings writes in Waylon: An Autobiography. “While I was singing, he’d go find the girls, and if we needed drugs, he’d go find the dope.” When Duane and Gordon teamed up to document McGill, it was a devil’s handshake deal: knowingly, if not entirely willingly, they submitted to the volatile ways of their subject. True, McGill had just been diagnosed with cancer and professed a desire to revitalize his music career. But altering his violent ways was not part of the program.

As many concert dates as McGill played in his lifetime, he was as likely to show up with a gun as a guitar. His life was largely spent trying to outwit and evade authority, and wrapping himself in a bolt of self-destruction. He hid from his real name, even, thus never making much of one for himself. He would steal the clothes right out of your closet, and he was as proud of his songs as he was of the counterfeit bills he printed. These are the qualities that compelled Paul Duane to track the guy down.

Very Extremely Dangerous will charm you, sure, with the sight of Jerry McGill singing and strumming in a hospital waiting room as a fellow patient thumbs through a back issue of the print version of WebMD. There’s also McGill pillaging a pile of ten-cent junk in the middle of a dirt field, coming away with a pair of boots, a cane, and a gigantic carnival-prize stuffed animal with bright, gaping eyes.

Never, though, does a feeling close to actual love for him burrow its way into your heart—neither, really, does the desire for Jerry to be redeemed. You don’t want him tamed. This is, after all, a man possessed of a remarkable self-awareness; as you watch him rasp through a recording session after something like four sleepless days, or see him cook up Dilaudid in the backseat of a car, two things become simultaneously clear: one, this is a man whose musical fame passed him by decades ago, and two, this is a born performer who recognizes the power of the camera rushing to catch his every pouncing move.

William Eggleston, Stranded in Canton, 1974, still from a black-and-white videotape, 77 minutes.

Still, you root for the guy, as you do any underdog; in the realm of characters, he’s somewhere between stock villain and reality TV star. He’s an eternal optimist, an opportunist, a folk hero, and his attitude is infectious. The film is structured against time, against the days ticking toward Jerry’s cancer surgery, but even as you witness him cooking up that Dilaudid, you don’t worry that he might die soon. If anything, you worry that someone else might die soon. Dangerous as his persona is, there’s little fear reserved for Jerry alone.

So, little love, little fear. Does that make him simply a curiosity? I think not. What I think is that there’s a part of us wanting to be Jerry, unbridled, uncontained, making up the days as we damn well please; as messy and lethal as his life is, he’s a classic American romantic, and we are voyeuristically drawn to him like a jealous Tom Sawyer who deep down would rather be Huck Finn and float down the river and smoke cigarettes all afternoon, but is too afraid. There’s the impulse of tourism: the desire to inhabit Jerry McGill’s world, to live his life, for just a little bit, but get back home safe. Director Paul Duane flew from Ireland to find McGill; he worried for his own life as he held up his camera in Jerry’s car, erratically racing down the highway at ninety miles an hour. Now, it’s always suspect when an outsider descends on Memphis, or anywhere in the South. People ascribe a certain exoticism to the landscape, as if it explains everything and reveals nothing.

Memphis, after all, “is a place where America assigns oddity,” said Robert Gordon, but he added an important caveat: “go across the bridge to the next town and you’ll find a bar filled with characters just like these ones.” Could Jerry McGill have been born elsewhere? Yes. He could be a character out of a Barry Hannah story or a shit-talking river-rat ex-con in Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree, set four hundred miles west in Knoxville, Tennessee. Memphis does not lay exclusive claim to the outlaw or the outsider.

At the same time, acknowledging this diminishes the myth of the place, a little bit. The night after Very Extremely Dangerous screened, in prelude to a presentation by Gordon, the novelist Michael Parker said,

Most of all I admired Robert Gordon’s abiding but unspoken understanding that place does not confine or for God’s sake refine us but define us, that—as suggested in the Cormac McCarthy quote Mr. Gordon chose as an epigraph for his wonderful biography of Muddy Waters—“they said it was no accident of circumstance that a man be born in a certain country and not some other and they said that the weather and seasons that form a land form also the inner fortune of men”—language and culture arise out of landscape. And in the case of Memphis, in the silt left by the recess of the bands preceding bands, the forgotten and neglected and often dead-and-gone forerunners.

When you are from these places, you collect your own McGill stories, stories of larger-than-life characters with an unassailable will to survive. They thrive figuratively in the works of everyone from Twain to O’Connor to Portis; they live next door. Take away their cars, and they will, like George Jones, hop on their lawn mower and ride into the sunset. Check the bills in your wallet: you just may be carrying Jerry McGill’s counterfeit cash.

An encore screening of Very Extremely Dangerous will be held at the Wythe Hotel screening room on February 9, followed by Gordon’s Stax Records documentary, Respect Yourself, on February 16, and Stranded in Canton on February 23.

Rebecca Bengal is from North Carolina; she is completing a collection of short stories. Her work has appeared most recently in The New Yorker’s Page-Turner, Oxford American, and Vogue.com. She last wrote for the Daily about Christian Patterson’s Badlands-inspired photobook, Redheaded Peckerwood.

Ice-T Reads a Fantasy Novel, and Other News

Photo: Ian Lamont, via Flickr

“This motherfucker got a sword that talks to him … Motherfuckers live in places that don’t exist, and it comes with a map. My God.” Ice-T records a Dungeons & Dragons audiobook.

On the eve of Sochi’s Winter Olympics, writers from around the world have signed a letter urging Putin to repeal laws limiting the freedom of expression. “We cannot stand quietly by as we watch our fellow writers and journalists pressed into silence.” American signatories include Jeffrey Eugenides, Jonathan Franzen, and Jonathan Lethem.

“What the fuck is a selfie?” In Baltimore, poverty precludes access to pop culture.

Discovered in an old Motown LP: Marvin Gaye’s passport.

Before car commercials learned to tug at our heartstrings and abuse the classic-rock canon, they looked like this, and we were all probably better for it. (He said, driving off in his 1985 Isuzu Gemini.)

February 6, 2014

Visualize It

Many thanks to Ed Summers, who writes code for libraries—the Library of Congress among them—and who has generated this impressive visualization of authors, their Paris Review interviews, and their links to one another. More specifically, this charts the way our interviews interact with Wikipedia—that is, which Wikipedia articles cite our interviews. As you can see, it’s … complicated.

Ed has written about his methods here. Apparently all but forty of our interviews are linked to Wikipedia in some capacity. �From this I can only infer that we’re headed inexorably toward a state of total Internet domination, and that anyone who stands in our way will be crushed under the weight of our burgeoning link-connection-web-computer-sphere-thing.

Denigrate Your Enemies, Shakespeare Style

Photo: courtesy of BAM

Last night I saw Angus Jackson’s King Lear, now at BAM, with a spry, sturdy Frank Langella in the title role. Langella was astonishing—he does high dudgeon, he does piss and vinegar, he does grief, perplexity, and weariness. His rimy, bellowing voice belies a surprising range, especially in the later acts. Lear dodders around, benighted, mad, machinating and fulminating to no one.

I haven’t read Lear in a while, and I’d forgotten that it has some tremendous insults in it—as befits a play about a graying, cantankerous head of state. I have a thing for archaic insults. They carry all the rancor of their modern-day counterparts, and with the added advantage of unfamiliarity—you called me what? The result is pure, clean-burning rage. It’s not unlike seeing someone mouth off in a country where you don’t speak the language.

Shakespeare, being Shakespeare, really knows how to deliver a good tongue-lashing—the theater has always been an ideal venue to see people go off on one another, and accordingly his plays are zested with putdowns. These are, I think, great fun to try on your friends. (And then, later, once you’ve mastered them, on your enemies.)

Here’s Lear, red hot but ice cold, in act 1, scene 4, asking the heavens to rain suffering on his daughter Goneril, who has just put him out:

Hear, nature, hear; dear goddess, hear!

Suspend thy purpose, if thou didst intend

To make this creature fruitful!

Into her womb convey sterility!

Dry up in her the organs of increase;

And from her derogate body never spring

A babe to honour her! If she must teem,

Create her child of spleen; that it may live,

And be a thwart disnatured torment to her!

Let it stamp wrinkles in her brow of youth;

With cadent tears fret channels in her cheeks;

Turn all her mother’s pains and benefits

To laughter and contempt; that she may feel

How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is

To have a thankless child! Away, away!

That convey feels most damning—as if the gods would shuttle sterility into a womb on a wheelbarrow, or with some sort of pulley apparatus. Derogate sits so well as an adjective that I wonder why we ever let it fall into obsolescence, and if there’s not a metal band called Child of Spleen, well, I’ll start one.

But the most scalding torrent of invective in Lear belongs to Kent, who, a bit later on, gives Oswald one of theater’s greatest dressings-down:

KENT

Fellow, I know thee.

OSWALD

What dost thou know me for?

KENT

A knave; a rascal; an eater of broken meats; a

base, proud, shallow, beggarly, three-suited,

hundred-pound, filthy, worsted-stocking knave; a

lily-livered, action-taking knave, a whoreson,

glass-gazing, super-serviceable finical rogue;

one-trunk-inheriting slave; one that wouldst be a

bawd, in way of good service, and art nothing but

the composition of a knave, beggar, coward, pandar,

and the son and heir of a mongrel bitch: one whom I

will beat into clamorous whining, if thou deniest

the least syllable of thy addition.

OSWALD

Why, what a monstrous fellow art thou, thus to rail

on one that is neither known of thee nor knows thee!

KENT

What a brazen-faced varlet art thou, to deny thou

knowest me! Is it two days ago since I tripped up

thy heels, and beat thee before the king? Draw, you

rogue: for, though it be night, yet the moon

shines; I'll make a sop o' the moonshine of you:

draw, you whoreson cullionly barber-monger, draw.

Should you deploy “whoreson cullionly barber-monger” at your next bar brawl, you’ll emerge victorious, guaranteed.

Not all the insults are so limpid, though. Earlier in the scene Kent says, “If I had thee in Lipsbury pinfold, I would make thee care for me.” I have no way of divining what “Lipsbury pinfold” might be—a wrestling variant, something akin to boxing’s Marquess of Queensberry rules? The New York Times says it means “between the teeth”; the Independent says it means oral sex; less reputable quarters of the internet say it’s “a very fine weave cloth, possibly with a narrow pinstripe on it.”

Still, “Lipsbury pinfold” has moxie—it pops. One imagines that, uttered with proper scorn, the term would still have the desired effect. There’s only one way to find out.

Sweets for the Sweet

A still from “The Cookie Carnival”

I devoutly hope there is an academic somewhere writing a serious essay about the role of anthropomorphic comestibles in Depression-era cartoons. I am no authority, but it seems pretty clear to me that, besides the obvious economic implications, all this humanized food has a great deal to do with gender norms, and attitudes toward food, and probably class, too. Disney’s 1935 Silly Symphony “The Cookie Carnival” would have to be the centerpiece of any such argument.

“The Cookie Carnival” is a Cinderella story that focuses on a sort of proto–Miss America boardwalk parade in which various confections compete for the title of “Cookie Queen.” In describing the plot, I can do no better than Wikipedia, which undertakes the task with commendable thoroughness:

Various sweets and goodies of Cookietown are preparing to crown their new Cookie Queen. A parade of potential candidates passes by, all based on various cakes and sweets. Far from the parade route, on what would appear to be the wrong side of the peppermint stick railroad tracks, a gingerbread drifter overhears an impoverished sugar cookie girl crying. Upon hearing that she cannot enter the parade because she hasn’t any pretty clothes, he hurries to remedy this, concocting a dress of colored frosting and candy hearts. He covers her brown hair with golden taffy ringlets and adds a large violet bow to her dress as a finishing touch. Thus attired, she is entered as the final contestant in the parade: Miss Bonbon.

The judges, who have thus far been disappointed in the candidates, all promptly declare Miss Bonbon the Cookie Queen on sight. The gingerbread man is practically trampled in the sudden surge of the crowd as they carry Miss Bonbon to her throne, where they place a golden crown on her head. She is then presented with a large layer cake, which appears to be a carousel of different vaudeville acts. A queen must have a king, and so the newly crowned Cookie Queen must choose a husband from those featured.

After being presented with a duo of tap dancing candy cane men, a pair of Barbershop singing Old Fashioned Cookies, a pair of effeminate angel food cakes, two scat-singing devil’s food cakes, some acrobatic upside-down cakes, and three tipsy rum cookies, she refuses each and every one with a giggle and a shake of her head. The judges, with no other suitors to present, make their own proposals.

At that moment, the gingerbread man, who has been attempting to gain a closer vantage point, sneaks up onto the dais. He is accosted by the guards who split his cupcake paper hat and tear off a piece of the jelly roll red carpet so that he looks as if he’s wearing a crown and an ermine-lined cloak. The Cookie Queen calls to the guards, “Stop! I say! Don’t crown the king that way!” The gingerbread man is immediately released and takes his place beside his beloved sugar cookie. Their closing kiss melts the lollipop intended to screen them from view.

The cartoon presents many troublesome portraits—there’s the obvious homophobia of the “Angel Cake” segment and the racism of the “Devils Food cake,” to say nothing of the trivialization of alcoholism. (While we’re on the subject, what, exactly, is a “rum cookie”? It looks vaguely cupcake-esque, but my vintage cookbooks have shed no light on the subject.)

Another Silly Symphony, 1933’s “Candy Town,” is similarly bizarre, though it’s more of a romp, all things considered: A feline couple arrives on the moon and discovers it is made of cake. They gorge themselves sick and then get chased home by a bottle of castor oil.

1936’s “Somewhere in Dreamland” is a more direct response to the Depression. Two urchins enter a magical land filled not merely with edible flora and fauna, but with clothes and toys, too. When they awake, they find that a bunch of kind neighbors have provided them with a real-life feast. (I suppose the political implications are fairly obvious, too.)

That all of these fall into the “Big Rock Candy Mountain” realm of fantasy isn’t hard to see; what is weird is just how often the anthropomorphic treats cheerfully offer themselves up for cannibalism and annihilation. Why are the donuts voluntarily dunking themselves in hot coffee? Why does the peppermint-stick king encourage the cats to lick him? I feel like a postcolonialist reading might have a few things to say on the subject.

I pondered these questions for far too long—and discovered several exceedingly interesting articles on the effects of the Great Depression on children and the intersection of escapism and social consciousness in media. My thoughts were alive, my intellect engaged. And then, of course, I had to look at the YouTube comments for “The Cookie Carnival.”

One more thing I just notice, The Cinderella Cookie was made up beautifully with a new dress and makeup, while the Cookie king just looks … incredibility plain in comparison … I kinda wish he gotten his own makeover. Lol.

Well, that too.

The Habits of Highly Erotic People

What can the French teach Americans about sex?

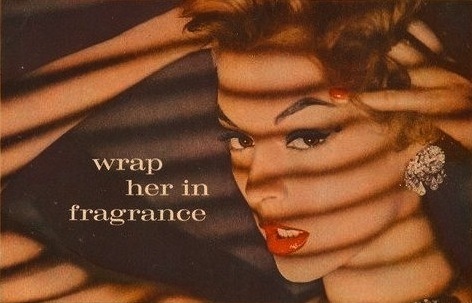

From a 1923 French advertisement

Last month, as the New York Post went into paroxysms over the latest French presidential love triangle, we found a more academic comment on French habits of the heart, thanks to our attendance at a panel on “The Art of Sex and Seduction,” sponsored by the Alliance Française. On the first of its three nights, entitled “Did the French invent love?”, Catherine Cusset, a former professor of French literature at Yale, told a story:

A countess invites a young man to her house after running into him at the opera. After a stiff meal with her husband, who retires to his private apartments, the countess leads her guest down a secret passageway into a bedroom. The walls and ceiling are covered with gilded mirrors. Sexual frenzy ensues. At daybreak, the giddy, exhausted young man emerges from the den and runs into a marquis who has just arrived. The marquis thanks him profusely. The young man realizes that he has served merely as a decoy to distract the count from his wife’s true lover. The husband appears for breakfast and greets the marquis cordially. The last line of this story—Vivant Denon’s No Tomorrow, first published in 1777—reads, “I looked for some moral to this adventure and … I could find none.”

“There is no moral lesson,” Cusset said pointedly, and a communal gasp could be heard in Florence Gould Hall. Throughout the series, the audience was susceptible to gasps, audible stirring, and sudden eruptions of laughter. The French and American panelists, who included historians, scientists, sex therapists, and journalists, spoke about vaginas and orgasms in that purposefully blunt way one always expects and yet can seldom prepare for. Here’s what we learned about the difference between French and American sexual customs and attitudes, with a few startling facts about tout le monde.

“Love, for the French, is tied up with adultery,” explained Marilyn Yalom, a feminist scholar at Stanford. Marriage in the Middle Ages, as least in the upper classes, was a contract related to the exchange of rank and property. Love was, therefore, to be found outside the marriage, leading to the mythic French threesome: the husband, the wife, the mistress.

Studies show that Americans and French have similar rates of infidelity, but the French, “marathoners,” have longer, and therefore fewer, affairs. Americans are “sprinters,” with more frequent but shorter trysts.

Older French women are considered sexual beings. A nonagenarian is to be respected as a repository of sexual history. When Colette was nearing fifty, pointed out her biographer Judith Thurman, she had an affair with her sixteen-year-old stepson, among other men-children.

Cusset once assigned Woman Destroyed, the novella by Simone de Beauvoir, in a class at Yale. The diary of a woman who discovers her husband of twenty years has been unfaithful, it records a gradual nervous breakdown. Cusset was surprised by her American students’ reaction. “They thought she whined too much. They didn’t understand that you can be broken by love.” Love as the loss of control—whether it brings ecstasy or devastation, within or without marriage—is a French ideal. Total surrender is too much for an American. We prefer to check boxes for the ideal mate.

More casually accepted notions in France: When a woman has married and produced the heir and a spare, she is free to live her own sexual life. A lover outside the marriage can save a marriage.

Marie de Bonaparte, a great-niece of the emperor and a student of Freud’s, was convinced that her frigidity was the result of an anatomical defect. After measuring the distance from the clitoris to the vagina in a group of women, she found that those with a shorter distance were more orgasmic. She had surgery to shorten hers. It didn’t work. She did it again, with no better luck.

Forty million Americans describe themselves as sex-starved. According to Helen Fisher, a biological anthropologist at Rutgers and chief scientific consultant to the dating site chemistry.com, it is often a question of mismatched libidos—an adventurer paired with a traditionalist, for example.

Studies show single Americans are having sex especially rarely. An audience member blamed Internet porn; the American sex therapist Ian Kerner theorized that everyone was too tired.

Women who had their cervixes wired for signs of stimulation were shown images of heterosexual, gay, and lesbian porn, and one image of bonobo chimpanzees having sex. The women claimed not to be excited by anything but “appropriate” images, but the instruments showed otherwise. The women were turned on by all the images, including the monkeys. Men, subjected to the same study, were excited by the predictable, and mostly said so. None of them reacted to the monkeys.

In a survey of five thousand Americans, 70 percent said they experienced sexual boredom in their relationship, but eighty percent of married couples said they would remarry the same person.

Women get bored sexually with the same partner much sooner than men. According to one study, women experience “a catastrophic decline of interest” after three years whereas men show a much more gradual erosion.

Studies and anecdotal accounts show rape fantasies to be ubiquitous among women.

In France, “flirting is a civic duty.” Flirting is playing with le fleuret, the tip of the sword.

There is a point of no return in the process of seduction, wrote the French eighteenth-century erotic writer Crebillon Fils, which is when the woman signals that she won’t say no.

As human animals, we have our own observable sexual cues. Females tend to tip their buttocks up during courting. There is also the “copulatory gaze,” during which the pupils dilate.

Manon Lescaut and Dangerous Liaisons were named the sexiest works of literature. Also, The Story of O still stands as a minor erotic masterpiece.

Why the French are not as morally conflicted about sex as Americans: “The French are keenly aware of the brevity of time and the immediacy of pleasure.”

For the French, love is “embedded in the flesh.” Americans “prefer to imagine love without the body.”

According to a French audience member in her twenties, there is no French translation for a date, as in the official dinner/movie outing, which she clearly thought sounded deadly.

A French therapist would not necessarily encourage, as would an American one, more “communication in bed.” Mystery, or what the French call le non-dit (“the unspoken”), is a better aphrodisiac.

An eager young woman had a question “from some friends.” Her “friends,” a new couple, were in love and very attracted to each other, but the man wouldn’t “release his inner wild man.” “What should she do?” the woman inquired, almost desperately. “She is ready for anything!” “When a man gets to know a woman, “ said the expert, “sometimes he becomes self-conscious about objectifying her that way. He thinks it’s wrong.” There was a silence as we considered the sensitivity of this hypothetical male. Then the American science writer suggested talking dirty to break the ice.

On all three nights, the audience was about fifty percent male, which surprised us. The third night, entitled “Behind the Boudoir: The Secrets of Sex Appeal,” attracted an especially attentive group, most of whom appeared in their seventies. The French audience members, whom we might assume to be appealingly jaded, were just as riveted as everyone else. Throughout the series, the ubiquitous French affirmation c’est normal (“that’s normal,” or “we are only human”) hung in the air as we delved into the often bizarre complexities of sex, and for a moment, we felt a uniquely Gallic pleasure: exulting in the complexity of a problem rather than searching for its solution.

Someone asked what Americans could teach the French about sex and seduction. There was a puzzled silence. Finally, the cultural historian suggested that French men could be encouraged to help out more with household tasks, with an important caveat: “Egalitarianism is wonderful in the kitchen but boring in the bedroom.”

Reading List:

No Tomorrow by Vivant Denon, translated by Lydia Davis

Secrets of The Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman

Claudine at School by Colette

How the French Invented Love: Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance by Marilyn Yalom

The Story of O by Pauline Réage

Manon Lescaut by the Abbé Prévost

Dangerous Liaisons by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence by Esther Perel

What French Women Know: About Love and Sex and Other Matters of the Heart and Mind by Debra Ollivier

What Do Women Want?: Adventures in the Science of Sexual Desire by Daniel Bergner

She Comes First: The Thinking Man’s Guide to Pleasuring a Woman by Ian Kerner

Susannah Hunnewell is the magazine’s Paris editor.

The Official Resort of the Third Reich, and Other News

Photo: m.a.r.c., via Creative Commons

Teens of Toronto: Are you fed up with Valentine’s Day and the crass commercialization of love—thorny, ineffable love? Then head to the library, where you can vandalize the covers of romance novels.

With the Burroughs centenary came a welcome glut of Burroughs miscellany, including these photos of the man hanging out with Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol, and Sting.

Today in ethically compromised vacation sites: Prora, a Nazi beach resort built just before the World War II. (Nowadays, part of it is a youth hostel: “You can hear the sound of the sea and meet like-minded people from around the world.”)

“Defined simply, literary Darwinism is the practice of using the theory of evolution to understand books.” I think I need it defined complexly.

St. Mark’s Bookshop is “gathering its forces for a big move.” You can help—not by lugging boxes but by shopping there, right now, this instant. Begone!

February 5, 2014

Happy Birthday, B. S. Johnson

With all the hullabaloo surrounding the Burroughs centenary, we’ve been remiss in celebrating another writer, B. S. Johnson, who would have been eighty-one today. (The B. S. stands for Bryan Stanley; if those were your initials, you’d go by them, too.) Johnson was an English novelist—“experimental,” or, if you’d prefer, formally innovative—who published seven novels, most of them in the sixties. I’ve read only The Unfortunates, from 1969, which was reissued a few years ago. It’s a book in a box: its twenty-seven chapters were printed as pamphlets and are, with the exception of the first and the last, intended to be read in any order.

Today it’s easy to shrug off such things as gimmickry, and yes, the format does make the reissue something of an art object, but make no mistake, it’s worth actually opening the box and reading the book. Its plot is straightforward: a sportswriter goes to an unnamed city to report on a soccer match, and as he roams, he begins to meditate on the death of an old friend. Each of the chapters summons different memories, which unfurl in a steady, stately tour de force, in the vein of Beckett or Henry Green’s Party Going. As Jonathan Coe writes in his introduction to the reissue, “Disintegration and frailty: these are the themes of The Unfortunates, and its tone is one of restless, enquiring melancholy.” Oh, well, here, see for yourself—this, the opening paragraph, is something that springs to mind, morbidly, whenever I go to the dentist.

But I know this city! This green ticket-hall, the long office half-rounded at its ends, that ironic clerestory, brown glazed tiles, green below, the same, the decorative hammerbeams supporting nothing, above, of course! I know this city! How did I not realize when he said, Go and do City this week, that it was this city? Tony. His cheeks sallowed and collapsed round the insinuated bones, the gums shriveled, was it, or shrunken, his teeth now standing free of each other in the unnatural half yawn of his mouth, yes, the mouth that has been so full-fleshed, the whole face, too, now collapsed, derelict, the thick-framed glasses the only constant, the mouth held open as in a controlled scream, but no sound, the head moving only slightly, the white dried and sticky saliva, the last secretions of those harassed glands, cauterized into deficiency, his mouth closing only when he took water from a glass by his bed, that double bed, in his parents’ house, bungalow, water or lemon he had to take frequently, because of what the treatment had done to his saliva glands, how it had finished them. Him.

The Secret Sex Lives of Famous People

Jean Patchett, in a 1957 Primitif by Max Factor ad.

There are a lot of things I should be reading right now: great books, worthy books, new books, books that, quite frankly, I need to finish for work. But I cannot. Ever since I ran across The Secret Sex Lives of Famous People on my grandparents’ bookshelf, I have been unable to crack anything else.

As the title indicates, this is the best book ever written, and possibly the only book one need own. The table of contents contains such categories as “Late Virginity Losers,” “Outsize Organs,” “Minute Members,” “Orgiasts,” “Interfered with When Young,” “Overrated or Disappointing Lovers,” “Clean and Unclean,” and “Peeping Toms.” As of this writing, I am only as far as August Strindberg (cross-listed as “Mother-Fixated,” “Prodigious Progenitors,” “Sex with Partners Twenty Years (or More) Younger”). But I have every intention of dispatching Zola (“Bigamists,” “Sex Trials and Famous Scandals,” “Erotica”) before the sun sets.

Despite the subject matter, and the red-and-purple 1981-issue cover, the tone of the book is not lurid. It is objective, almost academic. Or at least, the authors make all their declarations with absolute authority. Each entry begins with a biographical sketch; these, in themselves, are worthy of much close attention. Of Somerset Maugham, the authors assert, “In his 92nd year, partially demented, often angry, sometimes euphoric, he died of lung congestion.”

Of course, the sex stuff is still the best. To wit:

Hemingway had several unusual theories about sex. He believed that each man was allotted a certain number of orgasms in his life, and that these had to be carefully spaced out. Another theory was that, if you had sex often enough, you could eat all the strawberries you wanted without contracting hives, even if you were allergic to the fruit.

Rousseau had numerous sexual eccentricities. He had the odd habit of going into raptures over inanimate objects. When living with Madame de Warens, he would wander through her house, kissing the armchair, the bedcurtains, even the floor.

James Joyce, meanwhile, “was a true underwear fetishist, and even carried a pair of doll’s panties in his pocket.”

Lately, my inbox has been flooded with desperate advertisements for inappropriate Valentine’s Day gifts. And if tubs of popcorn and sofa cushions qualify as tokens of love, I feel I may as well throw my hat into the ring and nominate The Secret Sex Lives of Famous People as the sum total of my 2014 gift guide. In this I follow family tradition: last year, my father gave my mother At Your Service, the unspeakably lurid memoir by the cheerful gent who, by his own account, acted as procurer and trick for everyone in Old Hollywood. (My mother talked so often, and so darkly and cryptically, about Charles Loughton’s fetishes that in the end I had to read it myself.) But really, who wouldn’t love it? Paper is ephemeral, flowers fade, diamonds are forever but pricey. I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t prefer four whole pages on Mary Baker Eddy’s obsession with “Malicious Animal Magnetism.”

(Well, I suppose a real Joycean might prefer a pair of dolly panties.)

The Paris Review's Blog

- The Paris Review's profile

- 305 followers