Colin Mustful's Blog, page 9

June 16, 2021

A Fresh Approach to History in Fiction: Our Ohio Story by Kate McCord

Recently, I came across Our Ohio Story, a web serial by Kate McCord that tells an American story through a patchwork of sequential chapters, character sketches, and cultural reflections. It’s so engaging. It’s a wonderful way to use fiction to teach and get people really thinking about history. And though it’s an Ohio story, it’s not much unlike the stories I share about the settlement of Minnesota and its Native inhabitants. Here’s an excerpt from McCord’s first chapter. You can follow along on her website for free.

Chapter 1 – Stolen

By Kate McCord

1757 on the English calendar

The knot of a black oak root pressed into the boy’s hip. He shifted. Beneath his elbow, the steady Ohio River sucked soft earth from its bank and swallowed. The boy placed his hand on the base of the rough trunk beside him. He peered across the gentle face of the river. In the distance, three low wooden boats cut diagonally toward him. Virginia territory, their origin, the Shawnee’s home, their destination. Brave men, the boy thought. Brave enough to cross the Appalachians, build boats, dig their oars into the water, and fight their way into a land they didn’t belong in.

He lifted his bow and slipped a stone-tipped arrow into the cord.

A bearded man with a wide-brimmed, rounded-crown, black hat searched the bank where he hid.

The boy peered back. “Are you him?” He asked. His hands trembled.

Gray Hawk pulled himself beside the boy. “Be careful.” He whispered. “They’ll steal you if they see you.”

The boy nodded, aware of the deep auburn hair of his topknot and the flash of meadow green shoots in his eyes. The red and black paint streaked across his face and chest, the heavy grease that protected his skin from mosquitoes’ bites, the soft leather band around his waist, the dark blue cotton cloth that held his loins steady enough to run fleet-footed through the forest could not hide his true lineage. The man with the black hat might now, after all these years, demand him.

The boy pulled the string of his bow to his shoulder.

Gray Hawk touched him gently. “They’re too far away.”

The boy held his bow steady.

The man with the black hat slid past, his eyes still searching the wooded bank, but downstream now, beyond the boy’s hiding place beside the wide trunk of a black oak tree. Son of Fire relaxed his bow. He returned his arrow to the sheath slung over his shoulder. He stood, still thin and narrow, smaller than Gray Hawk, not yet man enough to grow a beard, another mark that would reveal him to be something other than what he was, a young Shawnee warrior.

Gray Hawk stood beside him and pointed across the river. “Beyond those mountains lays the valley called Shenandoah.”

The boy nodded. Piercing shards of memory flashed through his eyes. First, his mother’s scream, then thundering hooves, the whoops, and howls of red and black painted warriors, his father’s arms dropping him onto the ground. His wide-brimmed, rounded-crown, black hat aloft like a startled crow, his booted feet tripping headlong into the forest. His back, disappearing. And the boy, John Albee, light of his father’s eyes, left alone before the red and black painted warrior whose war club shattered the sky.

The boy wheeled, tiny hands balled into fists, face rage-fired screamed fury at a man four times his size on a horse that tore the ground before him.

The warrior pulled his horse hard left, leapt to the ground, and stood wide-eyed before the screaming, red-headed boy.

John Albee, barely old enough to be called a boy hurled himself into the painted man, fists flying, jaws snapping.

Gray Hawk wrapped the boy in arms stronger than the boy had ever known before, rocked his head back, and laughed. Son of Fire’s heart returned to the river bank. He looked at Gray Hawk, his brother. “Was it him?”

Continue reading… https://ourohiostory.com/2021/stories/chapter/s01ws001/

May 30, 2021

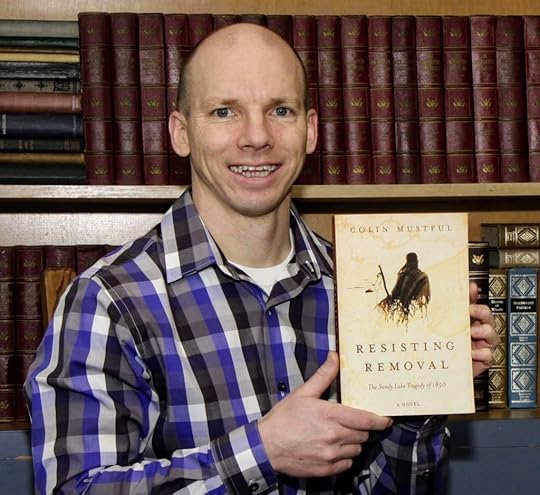

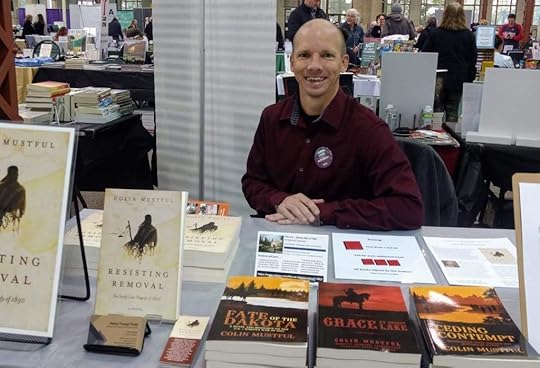

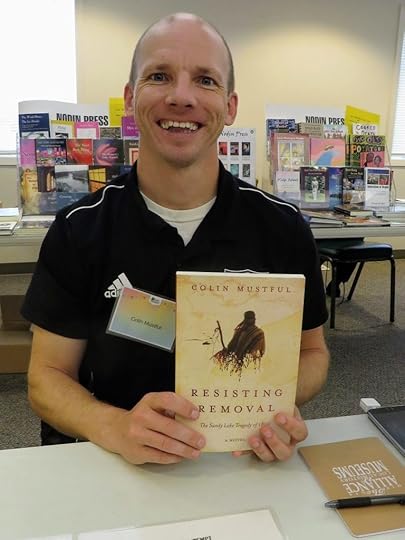

Author Update – Learn more about my writing process

Recently, I finished a full revision of my current writing project—a full-length, alternative history novel (103,263 words to be exact). When published it will be my fifth novel. Each one, as any author could tell you, has been a tremendous challenge that has required years of patient hard work. As I move forward with my current project, I’d like to take a moment to step back and share with readers some of the aspects of writing a historical novel. Consider it a behind the scenes look at my writing process.

The Assassination of Hole in the Day by Anton Treuer was the inspiration for my current Work-in-Progress.

The Assassination of Hole in the Day by Anton Treuer was the inspiration for my current Work-in-Progress.Inspiration – In my case, every novel has started with a small seed of inspiration. It’s not profound or sudden, like a lightning strike. Rather, it’s subtle and pleading, like an unreachable itch. The inspiration for my current Work-in-Progress (WIP) came, like the inspiration for my previous novel Resisting Removal, from a book by Anton Treuer. In The Assassination of Hole-in-the-Day, Treuer refers to an event in September 1862 that he calls “The U.S. – Ojibwe Conflict.” Having studied the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, I was surprised to find out that at the same time war broke out with the Dakota in southern Minnesota, violence nearly erupted between the U.S. and the Ojibwe in central Minnesota. As I read further, I learned that at the time the Ojibwe leader Bagone-giizhig (Hole-in-the-Day) was rumored to have been in talks with the Dakota leader Taoyateduta (Little Crow). This got my imagination going. What if the Ojibwe and Dakota joined forces and, as allies, fought back against U.S. tyranny and settler-colonialism?

Research – Before any historical novel can become a story with a plot and characters and dramatic twists and turns, there must be a foundation of historical knowledge. This is important for many reasons. It creates authenticity, it prevents the past from becoming skewed or misrepresented, and it gives the author many ideas to work from. My research always begins with broad secondary sources. I read books that cover the historical context of the time period in order to familiarize myself with the people and places I’ll be writing about. Then, as I identify specific people and events that I think may fit in my story, I do closer research using both secondary and primary sources. At this point, I’m no longer reading full-length books on the topic. Instead, I’m skimming for information and sources that will directly illuminate the people and events of interest.

For my current WIP, I also did a lot of cultural research. One of my characters is an Ojibwe. I am not. Because of this, I had to familiarize myself not just with the history, but with the cultural practices and traditions of the Ojibwe people. To do this, I relied on several books such as Chippewa Customs by Frances Densmore and Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa by Thomas Peacock and Marlene Wisuri. Of course, this brings up issues of appropriation but that is something I cover in other blog posts.

Writing – At some point during the research process it’s time to put down the books and notes and to start writing. The research is not done, but it needs the guidance of a story, and the story doesn’t exist until the writing begins. Usually, when I start writing I have a general idea of what I want my story to be, but I don’t have an entire outline. I just start writing by relying on my original inspiration and the information revealed through my research. As I move forward, I write one chapter at a time, taking breaks in-between chapters to type what I’ve written and to conduct more research. I’m not sure what will happen or where the story will go. I only know of the events and people I want to include. As I write, I have to rely on my creativity to think of ways to build upon each chapter and to incorporate the important people and events involved in the history I’m sharing. Often, I fear there is not enough material to write an entire novel. But I tell myself that as long as I still feel like there is more to write—like there is more that needs to be covered—then I ignore that fear and just keep writing.

Some visual proof that I handwrite my novels.Another important aspect of the writing process is discipline. Writing a novel is a long process that requires the patience to move forward one day at a time without feeling overwhelmed or defeated. In order to stay focused, I rarely consider the entirety a project. Instead, I just try to accomplish something—anything—related to my WIP every day. Some days it’s an hour of writing. Some days it’s three. Some days it’s a half hour of typing. Other days it’s two hours of research. For me, it’s just about being persistent and disciplined. I don’t try to get too much done, and I don’t try to think too far ahead.

My current Work-in-Progress began as a short-story that I started writing in June 2018 while staying at my father’s house for a few days. At the time, I was entering my second year of my MFA program at Augsburg University, and I was required to write a short-story that would be critiqued at our summer residency. I wrote it in the mornings while my father worked on revising his own book. The story was about twenty-five pages long, and it received some criticism—which is the purpose of critique groups, after all. In the fall of 2018, I built upon the story with the goal of making it into a complete novel by the spring of 2019. However, in the fall I received some poignant but perceptive criticism that forced me to take a step back. Rather than continue to move the plot forward, I had to get to know my characters by exploring their backgrounds. It wasn’t until the summer of 2019 that I was able to move the story forward again, but this time with a much better idea of who my characters were and what they wanted.

Reaching the end of a first draft is not exactly a smooth process. As I already pointed out, I met some obstacles while writing my current WIP. And as I continued writing, I often found myself going back to rewrite or add scenes in order for the story to make sense with the new scenes, characters, and chapters I added going forward. This is true of every novel I’ve written. The process does not move forward in a straight line, rather it zig-zags forward until finally reaching an end point. For my current WIP I reached that point in September 2020.

First Read-through – The best part of the writing process, for me, is when I get to read my first draft. It’s a little bit nerve-wracking because as the writer, being so close to the story makes it hard to tell if what you did actually worked. But somehow it does work. I always enjoy the story the first time I read it, even though it’s not perfect, even though there is so much room for improvement. And, I’m always a little bit amazed. It’s a lot like finishing a marathon—you’re relieved, exhausted, and somewhere deep down you’re extremely proud.

This is me completing the Madeline Island Marathon in 2019. Completing a marathon is not that much different from completing a novel. By the way, it was so cold that morning. I was miserable.

This is me completing the Madeline Island Marathon in 2019. Completing a marathon is not that much different from completing a novel. By the way, it was so cold that morning. I was miserable. Beta Readers – In this step of the process, I give the manuscript over to readers who volunteer to critique the first draft. They don’t provide any specific edits. Instead, they look at the story as a whole and provide the writer with general feedback. They point out plot holes and inconsistencies. They let the writer know what they liked and what they didn’t like; which characters were endearing and which characters fell flat. Beta readers are extremely important because they help frame and shape the story. For my current WIP, I sought beta readers in November 2020 and found about ten gracious readers—some friends and family, some colleagues, and some people I did not know at all.

First Revision – By January 2021, I had received feedback from all of my beta readers. This was incredibly gut-wrenching and always is. That’s because, after spending two years on a project, inevitably, it is painful to see it criticized even when criticism is the goal. But, my beta readers did a fantastic job by giving me insights that I couldn’t see myself. And I’ve learned that by listening to beta readers and incorporating their feedback the story becomes much better.

Using their feedback, I started on my first full revision of my current WIP in mid-January 2021. I began by adding a couple of chapters in order to further develop a few characters. Then, I started reading from page one, slowly working my way through each page, each paragraph, each sentence, and each word making revisions along the way. I expected that this would only take two or three months, but I didn’t finish my revision until May of this year. Because I was busy with my jobs and other obligations, I did most of my revisions between 5:40am and 6:30am before going to work. Although I wasn’t spending a lot of time working on the project, it was enough to move it forward.

The writing process for my current WIP is far from over. The next steps involve editing, revising, editing, revising, and then moving toward the submission process which involves querying and writing marketing plans and other things like that. But for now, after almost three years, I’ve completed my first full revision, and I’m currently working on a second read-through. Perhaps, in a year or two, I will continue this blog post so I can share more with you about the long, tedious, and rewarding process of writing and publishing a novel.

Colin Mustful is an author, historian, publisher, and editor. He is the author of four historical novels and the founder and editor of his own press, History Through Fiction. He has a Masters degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing with a concentration in publishing. He lives and works in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

May 10, 2021

The Original Border Battle – Minnesota vs. Wisconsin

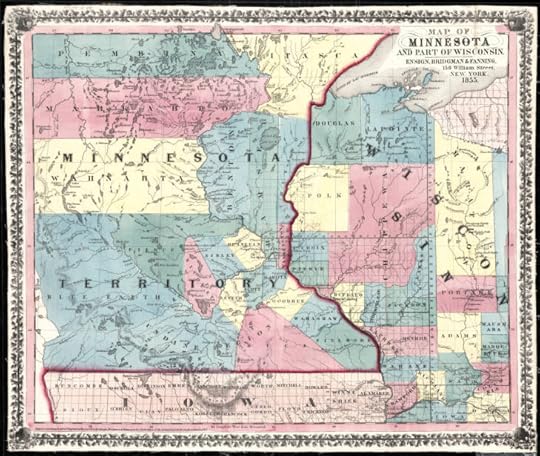

The Minnesota/Wisconsin Border, 1855. Map from the Hennepin County Library Digital Collections – https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/...

The Minnesota/Wisconsin Border, 1855. Map from the Hennepin County Library Digital Collections – https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/... Separated by the St. Croix and Mississippi rivers, the states of Minnesota and Wisconsin have a well-established, recognizable boundary. But the borders of each state, and the boundary that separates them, was not always certain. When Wisconsin applied for statehood in 1846, Minnesota as a territory did not exist and the argument over Wisconsin’s western boundary became the first border battle in what would become a perpetual rivalry.

In 1846, as the settler-colonial population boomed to more than 155,000 people, Wisconsin applied for statehood. The resulting bill, called “The Enabling Act,” was approved by Congress August 6, 1846. In the act, Congress established the western boundary of the state with the following description:

“…thence through the centre of Lake Superior to the mouth of the St. Louis River; thence up the main channel of said river to the first rapids in the same, above the Indian village, according to Nicollet’s map; thence due south to the main branch of the River St. Croix; thence down the main channel of said river to the Mississippi . . .”

But before Wisconsin could become a state it had to write a state constitution that was approved by its citizens. This resulted in the establishment of a constitutional convention where debate ensued over the proposed western boundary. According to the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, only five states were to be formed out of the Northwest Territory. Because four had already been formed, this meant that the western boundary for the state of Wisconsin would have to stretch all the way to the Mississippi River and then north toward the international boundary. Members of the first constitutional convention who supported this far western boundary became known as “fifth-staters.” The fifth-staters were supported by southern Democrats who wanted to maintain the balance of power in the Senate by adding as few northern states to the Union as possible.

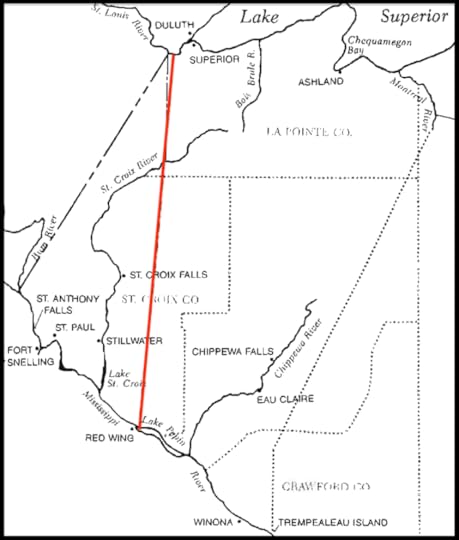

Holcombe’s Proposed Boundary

Holcombe’s Proposed BoundaryHowever, there were several factions that opposed the fifth-staters. One was headed by Stephen A. Douglas who insisted that Congress was not bound by the Northwest Ordinance, and who proposed a boundary drawn from the westernmost point of Lake Superior due south to the Mississippi River. Another faction that disagreed with the far western boundary sprang up from the members representing the areas of St. Paul, Stillwater, and the St. Croix who did not want to be included in the new state of Wisconsin. These were the fur traders, lumberjacks, squatters, and speculators who lived far from the seat of government in Madison. Also, they did not want to see the St. Croix River Valley, rich and abundant in natural resources, to be split by a state boundary. Members of this faction were led by William Holcombe who argued that Wisconsin should be small enough to allow a sixth state of roughly equal size to be created out of the Northwest Territory. Holcombe proposed a far eastern boundary that would run north from Trempealeau Island in the Mississippi River and then northeast to the mouth of the Montreal River.

Boundary Proposed by the first Constitutional Convention

Boundary Proposed by the first Constitutional Convention Holcombe could not find much support for his eastern boundary proposal, and it was rejected by a vote of 51 to 29. However, he then proposed a boundary further west starting from the St. Louis river rapids to a point east of the most easterly point of Lake St. Croix, and from that point south to the head of Lake Pepin. This line was approved by the convention by a vote of 49 to 38. Although this line was further west than Holcombe’s original boundary proposal, it did not completely divide the St. Croix River Valley.

The constitution, which included Holcombe’s boundary change, was approved by Congress on March 3, 1847. But before Wisconsin could become a state the constitution had to be approved by Wisconsin voters. After what was described by historian William E. Lass as a “long, emotional campaign,” Wisconsin voters rejected the constitution by a vote of 20,231 to 14,116. Though some voters may not have approved the boundary change, most rejected the constitution because of, what was considered at the time, some of its more progressive provisions. This included a provision to give married women property rights, and a provision that would have forbidden the chartering of banks.

After Wisconsin voters rejected the state constitution, a second constitutional convention was established in October 1847. This reignited the debate over Wisconsin’s western boundary. At the convention a new faction emerged that recognized the immense value of the timber and mineral resources throughout the St. Croix and Mississippi River valleys, as well as the water-power at St. Anthony Falls, and fought to establish the boundary as far west and north as possible. This faction was supported by Daniel G. Fenton, a lawyer from Prairie du Chien who proposed a boundary that ran southwest from the St. Louis River to the mouth of the Rum River. This became known as the Rum River Line.

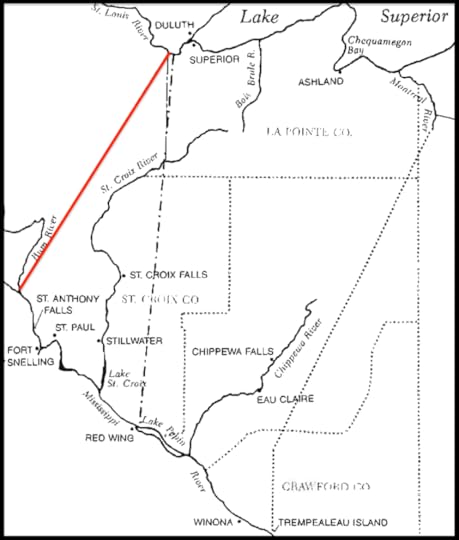

Rum River Line proposed by the second Constitutional Convention

Rum River Line proposed by the second Constitutional ConventionOne of the objectors of the Rum River Line was George W. Brownell who stood for St. Croix separatism. In an attempt to garner support for a more eastern boundary, Brownell walked in snowshoes from the St. Croix Valley to Madison in order to demonstrate the remoteness of the area. His dramatic gesture won little support and when his proposed boundary was brought to a vote, it was rejected 52 to 5. Ultimately, supporters of the Rum River Line won out when their resolution was approved 53 to 3. When the second constitution was sent to Congress, it declared the Rum River Line as the “the preference of the State of Wisconsin.”

The second constitution, and the Rum River Line proposed within it, was not well received by everyone. Those who identified themselves as residents within the limits of Minnesota Territory, wrote and sent a petition to Congress against the Rum River Line and suggested a new boundary running south from Chequamegon Bay to the Chippewa River and then south along the Chippewa to the Mississippi River. The petition created some excitement in St. Croix County, but it did not stop Wisconsin voters from approving the second constitution. On March 13, 1848, they voted to approve the constitution, along with its Rum River Line provision, by a vote of 16,759 to 6,384. The constitution did not include controversial measures such as property rights for married women. In St. Croix County residents voted against acceptance 277 to 17.

When the issue was put before Congress for final approval, the Minnesota petition provoked much debate. Also, George W. Brownell traveled to Washington to make a direct appeal to Congress. While there he published a seven page article titled, “Boundaries of Wisconsin: Reasons Why the Boundaries of Wisconsin, as Reported by the Committee for the Admission of that Territory into the Union as a State, Should not be Adopted.” However, rather than reject the constitution and send it back to Wisconsin for renewed debate, Congress decided to ignore the preference for the Rum River Line and accept the boundary that was laid out in the Enabling Act of 1846, arguing that Wisconsin had accepted it despite preferences for another boundary.

Therefore, on May 29, 1848, Wisconsin was admitted as the 30th state in the Union with the western boundary as specified in the enabling act. This upset many St. Croixans who did not want to see the St. Croix Valley divided. In protest, James Madison Goodhue, editor of the Minnesota Pioneer wrote, “Here now, is the whole valley of the Saint Croix, without an interest or an affinity for Wisconsin . . . yoked to Wisconsin by the potent will of the Convention. All this was done, against the consent and eloquent remonstrances of the delegates from St. Croix. As for us, in Minnesota, who have been carried up into Father Abraham’s bosom, we can only look down with compassion upon our neighbors across the great gulf of the Saint Croix and pray for their safe deliverance.”

Sources:

William E. Lass, “Minnesota’s Separation from Wisconsin: Boundary Making on the Upper Mississippi Frontier,” in Minnesota History, (Winter 1987): P. 309–320. http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/50/v50i08p309-320.pdf

Minnesota Pioneer, March 6, 1850.

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and overlooked past.

Submit a form.April 28, 2021

Appropriate by Paisley Rekdal – A Review and Reaction

Appropriate: A Provocation

By Paisley Rekdal

Published by W.W. Norton & Company

Released February 16, 2021

ISBN: 978-1-324-00358-8

Within all written texts there exists an implicit writer-reader contract. Although this contract can be defined in many ways, essentially, the writer agrees to share something that is true and valuable, while the reader agrees to listen and give the writer her trust. This unspoken contract creates a personal relationship between the writer and reader that is infinitely unique, and is based on what each party brings to the text. For any written text to have purpose, the writer-reader contract is necessary, but it is also problematic. In Paisley Rekdal’s new book, Appropriate: A Provocation, the author critically analyzes the writer-reader relationship as it relates to cultural appropriation, a pervasive political and literary criticism for how people and their history, art, language, and ways of life and thinking, are portrayed by those outside their cultural sphere. Put simply, cultural appropriation is the act of passing someone else’s work or voice off as your own. It’s wrong, but how, why, and when; and is it irredeemable? These are some of the questions Rekdal thoughtfully considers.

Rekdal, who is Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Utah, epitomizes the writer-reader relationship in the way she composes her book as a series of letters to a student known as “X”. The book proceeds as a series of definitions, observations, and case studies about cultural appropriation in literature and popular society. Rekdal moves from one “letter” to the next, carefully providing her observations and analysis on various forms of cultural appropriation, both those that have been done with intention or malice, and those that have been done out of ignorance or good intentions. It is written in a manner that is highly academic in language and process making it, at times, challenging to comprehend. But, it’s Rekdal’s dedication to process that makes this book and its conclusions that much more effective and necessary.

Book Review – Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State by Christopher Lehman

Appropriate does not cast aspersions (with one notable exception toward author Jack London) on writers past or present for their attempts to convey or portray cultures different from their own. That’s not to say that she agrees with them or believes their actions are moral or justified, but she asks the reader to look beyond the failure of any given text in order to mine value from what remains. Essentially, Rekdal champions critical thinking as both a reader and a writer. Rather than being pretentious and haughty, she admits to her own faults while asking readers and writers to look beyond their own worldview, to consider context, and to reevaluate the purpose and results of culturally appropriative materials. In doing so, Rekdal provides a series of guidelines, both for understanding and for analyzing appropriative texts. These guidelines provide readers the tools they need first, to recognize and distinguish appropriative texts, second, to deconstruct the text for any underlying value or lessons, and third, to look inward in order to evaluate their own role in the existence and perpetuation of racist ideology and colonial, capitalist structure. Rekdal does the same for writers, giving them guidelines and strategies to avoid cultural appropriation when possible and to manage its risks and consequences when avoiding it becomes impossible or undesirable.

Ultimately, the only way to avoid cultural appropriation is to back away completely from society. But, I would argue, that would be quite a dull existence. In her book Appropriate, Paisley Rekdal shows us that we must confront cultural appropriation, not as a moral judge or caretaker, but as an open-minded participant both in the world we live in and the one we are striving to achieve. No single authority has ownership over the moral righteousness of any single work of artistic expression. Right or wrong, better or worse, every reader brings their own set of intricate experiences and biases to a text while every writer brings their own truth and goals. There should not be a single solid line, which moves over time by the way, that producers and consumers of appropriative materials cannot cross. There should, however, be an open and respectful dialogue about what delineates cultural appropriation, how and why it’s hurtful, and how all of us, together, can express ourselves and our stories without harming, subjugating, or minimizing the story of another.

Quotes from the Text

“With regards to writing and appropriation, the real question is not whether I can simply ignore or override racial stereotypes, or even whether certain cultures have immutable claims to particular subjects and content, but what appetites I feed when I write from a position outside of my own.”

“I’m going to suggest that, if you engage in subject appropriation, you will research your characters thoroughly, doing all the intimately engaged critical, historical, literary, and sociological due diligence necessary before committing the details of your character’s life to the page.”

“If you are looking for comfort or vindication for your writing, you will never have it. You will have to choose for yourself, understanding that even sensitive literary portrayals may perpetuate racist systems.”

“To understand that we are each—at best—a set of relations and possibilities, not inevitabilities, is a great lesson to be learned.”

“In that sense, if I don’t believe reading is a moral endeavor, I do believe it is a critical skill with moral effects, and that these effects become more pronounced the more carefully I attend to my reading.”

“So instead of discarding all texts that could neither anticipate nor correspond with our contemporary sensibilities, perhaps we might ask what, if anything, we might want to recuperate from them, so that these works can continue to educate us as readers of history, if not as models of humanistic merit.”

About the Author

Paisley Rekdal is the author of ten books of poetry and nonfiction. A former recipient of Guggenheim and NEA fellowships, she is Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Utah and is the state’s poet laureate. She lives in Salt Lake City.

April 15, 2021

Violating the Spirit of the Law – The Trial of Wowinape

On July 3, 1863, Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey discovered a Dakota man and his son in a raspberry thicket outside of Hutchinson, Minnesota. Aware that there was a $500 bounty on Indians, Lamson took aim and shot at the Dakota man. After a brief exchange of gunfire, the Dakota man lay dead and Lamson lay injured. While Lamson’s son, Chauncey, ran to town for help, the son of the Dakota man placed new moccasins on his father’s feet for his journey into the spirit world, folded his arms, and carefully wrapped him in a blanket. He then walked alone to the north.

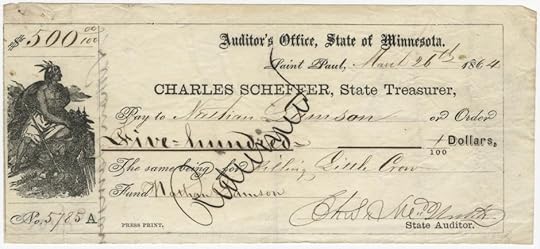

The bounty check paid by the state of Minnesota to Nathan Lamson for killing the Dakota leader Little Crow. MNHS Collections

The bounty check paid by the state of Minnesota to Nathan Lamson for killing the Dakota leader Little Crow. MNHS CollectionsIn the aftermath of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, after seeing hundreds of their neighbors and friends killed by Indians, fear and a thirst for revenge dominated the white settlements of Minnesota. In that spirit, the people of Hutchinson rejoiced at the death of the Dakota man killed in the raspberry patch. They dragged his body through the streets, set off firecrackers in his nostrils, and severed his head from his body. That man, the people later learned, was Taoyateduta—Little Crow—the leader of the Dakota War effort less than a year earlier. The boy who got away was Wowinape, Little Crow’s sixteen-year-old son.

In late August, Wowinape was captured by General Henry Sibley’s soldiers, who described the boy as “half-starved and nearly naked.” Sibley quickly established a military commission at Fort Abercrombie to put Wowinape on trial. The charges and proceedings mirrored those of the military commission that tried and convicted hundreds of Dakota men in October 1862. During Wowinape’s brief trial, several witnesses said they had seen the teenaged boy at the second battle of New Ulm and at the fighting outside Hutchinson. Others declared that after his capture they heard Wowinape admit that he had returned to Minnesota with his father to steal horses. Wowinape’s trial concluded on September 28, 1863, ending in a guilty verdict and he was sentenced to death by hanging.

Wowinape, 1864, MNHS Collections

Wowinape, 1864, MNHS CollectionsThe verdict was approved by the head of the military commision, Henry Sibley, and then sent to Major General John Pope in St. Paul, who forwarded it for final approval to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt. However, Holt declined to review the trial citing an 1861 statute that required “the General Commanding the Army in the Field to confirm or disapprove the proceedings.” In other words, Holt told General Pope that it was his job to determine the fate of Wowinape.

During and after the Dakota War, Pope expressed an eagerness to exterminate the Dakota people. However, when tasked with reviewing the trial and sentencing of Wowinape, Pope argued that he had no legal authority to confirm the sentence. He also cast doubt on the proceedings by citing Article 65 of the Articles of War which stated that the convening officer, in this case Henry Sibley, could not also be the “accuser or prosecutor.” If the same rationale were applied to the Dakota War trials that took place in the fall of 1862, every one of the 392 cases would have been invalidated.

In a letter to Judge Advocate General Holt, Pope noted that the proceedings against Wowinape were “in violation of the spirit of the 65th Article of War, but [that] there . . . [was] a possible doubt.” Holt agreed, and shortly thereafter Pope disapproved Wowinape’s death sentence. Instead, Little Crow’s son was imprisoned at Camp McClellan with the prisoners from the Dakota War. He remained there until 1865 when he was pardoned. Later, he converted to Christianity and changed his name to Thomas Wakeman. He resettled in Flandrau, South Dakota and helped to organize the first Native-run YMCA. He died of tuberculosis on January 13, 1886.

Sources:

Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota, (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

John A. Haymond, The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law and the Judgment of History, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016).

Carol Chomsky, “The United States-Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice,” Scholarship Repository, University of Minnesota Law School, (1990), https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1230&context=faculty_articles

“Wowinape,” Minnesota Historical Society, U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, Accessed April 13, 2021, https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/wowinape.

Want to Learn More? Check out my Historical Novels about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 and its Related History – https://colin-mustful.square.site/

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past. To schedule an event or interview, email the author at mnauthor@colinmustful.com

Submit a form.March 27, 2021

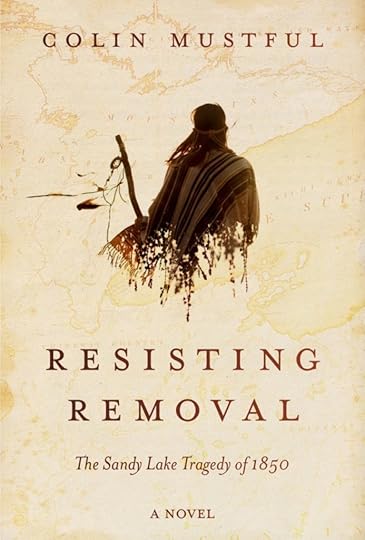

Watrous vs. Armstrong: An Audio Excerpt from the Novel Resisting Removal

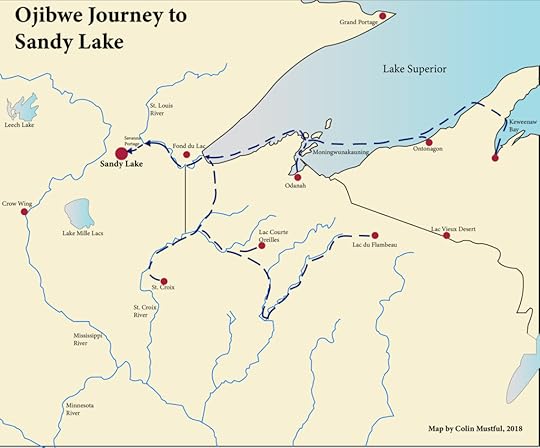

For several years, Indian agent John Watrous attempted to force the removal of the Ojibwe people from their homes along the southern shore of gichi-gami (Lake Superior), a plan that resulted in the death of 400 Ojibwe at Sandy Lake, Minnesota in late 1850. Two years after the tragedy at Sandy Lake, in an effort to continue their forced removal, John Watrous moved the La Pointe Band of Ojibwe’s agency from La Pointe, Wisconsin, to Crow Wing on the Mississippi river in Minnesota Territory. The Ojibwe were told that if they wished to receive their promised annuity payments, they must travel to Crow Wing in order to receive it. The Ojibwe were unwilling to travel such a long distance so late in the season and with obvious reason—the Sandy Lake Tragedy was fresh in their memories.

The journey of the Ojibwe from their homes near Lake Superior to Sandy Lake in 1850. Two years later, they were asked to travel to Crow Wing on the Mississippi River.

The journey of the Ojibwe from their homes near Lake Superior to Sandy Lake in 1850. Two years later, they were asked to travel to Crow Wing on the Mississippi River. Because the Lake Superior Ojibwe were not there to receive the goods and monies promised them in their treaty, Agent Watrous stored their annuities in an agency building at Crow Wing. Learning their goods awaited them, a group of Lake Superior Ojibwe made the long trek to Crow Wing in early 1852 to collect their belongings. However, when they arrived, they found that an arsonist had burned down the building, destroying everything inside.

Benjamin Armstrong, a white man who lived at La Pointe and married an Ojibwe woman, had apparently traveled to Crow Wing with this group of Ojibwe because he recorded the event in his memoir, Early Life Among the Indians. According to Armstrong, after searching through the ash and debris left behind by the fire, the only thing of value that the Ojibwe recovered were two fifty-cent silver pieces.

In the novel Resisting Removal, agent John Watrous plays the role of the antagonist, or villain, of the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the years that followed. Benjamin Armstrong is the first-person narrator and plays the role of a flawed protagonist. While the author, Colin Mustful, relied on real historical documentation to recreate the people and events of this time in history, some scenes, like the one at the burned down storehouse in Crow Wing, were largely fictionalized. In the following audio excerpt, the villain Watrous and the hero Armstrong face off in a heated discussion. In reality, the meeting likely never took place. But in the novel, it serves as a critical climax when right and wrong, past and future, collide, and force readers to consider the truth of history.

Get your Copy of

Resisting Removal

March 19, 2021

Farewell to Black Hawk – The Grief of a Defiant Leader

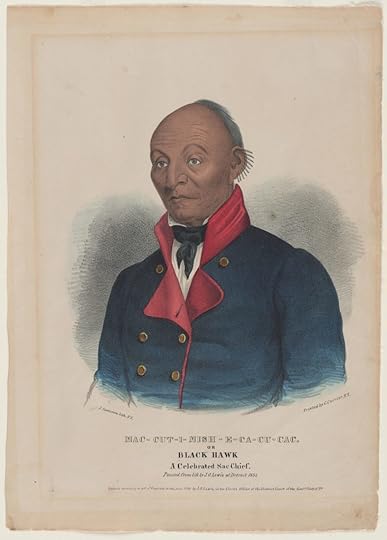

A hand-colored lithograph of Black Hawk by James Otto Lewis, 1836. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution – https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.79.90

A hand-colored lithograph of Black Hawk by James Otto Lewis, 1836. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution – https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.79.90On August 27, 1832, the Sauk leader Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak) surrendered to the U.S. 6th Infantry at Prairie du Chien, ending several months of fighting in what is now called the Black Hawk War. The war was a consequence of the U.S. government’s Indian removal policies that continually forced Native peoples from their homes to places further west. In 1832, Black Hawk of the Sauk people, and a number of other Native tribes who joined forces with Black Hawk and came to be known as the “British Band,” returned to their homes in present-day Illinois. The Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) tribes had ceded the land in the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis and then were forced to remove from the land after the “Corn Treaty” of 1831. But, many Native leaders disputed the Treaty of St. Louis because it had never been authorized by their tribal councils. This dispute, and years of mistreatment, led Black Hawk and his followers to cross the Mississippi into Illinois in 1832 to reclaim their lands.

Black Hawk and his followers, who included women and children, were eventually met by U.S. militia forces. Without provocation the U.S. forces attacked Black Hawk’s group of non-combative Natives on May 12, 1832 in what has become known as The Battle of Stillman’s Run. Black Hawk responded by going on the offensive and enjoyed many early victories while forcing the white settlers in the area to flee to Chicago. These offensive assaults included some raids that were not directly related to Black Hawk’s objectives. One such raid was the Indian Creek Massacre that resulted in the death of fifteen civilians by a large war party of Potawatomi. But, after U.S. forces reorganized and gained the support of some Native tribes that were enemies to the Sauk and Meskwaki, Black Hawk and his followers were forced to retreat. After U.S. forces caught up with Black Hawk, they attacked him and his non-combatants after they attempted to surrender. Most of Black Hawks followers were then attacked while attempting to flee across the Bad Axe River. Called The Battle of Bad Axe, it is also known as the Bad Axe Massacre because it was a lopsided affair. An estimated 260 Natives were killed while U.S. losses were reported as five killed and nineteen wounded.

Upon his surrender to Indian Agent Joseph M. Street, Black Hawk gave to one of the most widely known statements of Native defiance. The speech, which follows, was published in 1882 in a book by historian A.R. Fulton. While it’s impossible to know if these words were reported correctly, they do reflect the sentiment of defiance, anger, and grief expressed by Black Hawk in his autobiography and other statements.

Farewell to Black Hawk

You have taken me prisoner with all my warriors. I am much grieved, for I expected, if I did not defeat you, to hold out much longer, and give you more trouble before I surrendered. I tried hard to bring you into ambush, but your last general understands Indian fighting. The first one was not so wise. When I saw that I could not beat you by Indian fighting, I determined to rush on you, and fight you face to face. I fought hard. But your guns were well aimed. The bullets flew like birds in the air, and whizzed by our ears like the wind through the trees in the winter. My warriors fell around me; it began to look dismal. I saw my evil day at hand. The sun rose dim on us in the morning, and at night it sunk in a dark cloud, and looked like a ball of fire. That was the last sun that shone on Black Hawk. His heart is dead, and no longer beats quick in his bosom. He is now a prisoner to the white men; they will do with him as they wish. But he can stand torture, and is not afraid of death. He is no coward. Black Hawk is an Indian.

He has done nothing for which an Indian ought to be ashamed. He has fought for his countrymen, [the women and babies], against white men, who came, year after year, to cheat them and take away their lands. You know the cause of our making war. It is known to all white men. They ought to be ashamed of it. The white men despise the Indians, and drive them from their homes. But the Indians are not deceitful. The white men speak bad of the Indian, and took at him spitefully. But the Indian does not tell lies; Indians do not steal.

An Indian who is as bad as the white men, could not live in our nation; he would be put to death, and [eaten] up by the wolves. The white men are bad school-masters; they carry false looks, and deal in false actions; they smile in the face of the poor Indian to cheat him; they shake them by the hand to gain their confidence, to make them drunk, to deceive them, and ruin our wives. We told them to let us alone; but they followed on and beset our paths, and they coiled themselves among us like the snake. They poisoned us by their touch. We were not safe. We lived in danger. We were becoming like them, hypocrites and liars, adulterers, lazy drones, all talkers, and no workers.

We looked up to the Great Spirit. We went to our great father. We were encouraged. His great council gave us fair words and big promises, but we got no satisfaction. Things were growing worse. There were no deer in the forest. The opossum and beaver were fled; the springs were drying up, and our [women and babies] without victuals to keep them from starving; we called a great council and built a large fire. The spirit of our fathers arose and spoke to us to avenge our wrongs or die…. We set up the war-whoop, and dug up the tomahawk; our knives were ready, and the heart of Black Hawk swelled high in his bosom when he led his warriors to battle. He is satisfied. He will go to the world of spirits contented. He has done his duty. His father will meet him there, and commend him.

Black Hawk is a true Indian, and disdains to cry . . . He feels for his wife, his children and friends. But he does not care for himself. He cares for his nation and the Indians. They will suffer. He laments their fate. The white men do not scalp the head; but they do worse—they poison the heart, it is not pure with them. His countrymen will not be scalped, but they will, in a few years, become like the white men, so that you can’t trust them, and there must be, as in the white settlements, nearly as many officers as men, to take care of them and keep them in order.

Farewell, my nation. Black Hawk tried to save you, and avenge your wrongs. He drank the blood of some of the whites. He has been taken prisoner, and his plans are stopped. He can do no more. He is near his end. His sun is setting, and he will rise no more. Farewell to Black Hawk.

Sources:

“The Defiance of Chief Black Hawk,” The History Engine, Accessed March 16, 2021, https://historyengine.richmond.edu/episodes/view/4638.

Anthony F.C. Wallace, “Prelude to Disaster: The Course of Indian-White Relations Which Led to the Black Hawk War of 1832,” The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Summer, 1982, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Summer,1982), pp. 247-288.

Bob Blaisdell, Ed., Great Speeches by Native Americans, (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2000), pp. 84-85.

“Indian Creek Massacre,” Wikipedia, Accessed March 18, 2021, Last Updated January 14, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Creek_massacre.

“Black Hawk (Sauk Leader),” Wikipedia, Accessed March 3, 2021, Last Updated March 9, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Hawk_(Sauk_leader).

“Black Hawk War,” Wikipedia, Accessed March 17, 2021, Last Updated February 20, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Hawk_War.

Email Address

Subscribe

Check out these other posts from my Blog, or enter your email address to subscribe and get posts sent straight to your inbox!

Farewell to Black Hawk – The Grief of a Defiant LeaderSully’s Expedition Against the Sioux: Another Military Campaign in the Aftermath of the Dakota WarMy Instagram Live Interview with Oanh JordanThe Punitive Expedition of Henry Sibley: Reevaluating the “Success” of his CampaignThe Largest Mass Execution in U.S. History: A timeline to understand how Abraham Lincoln ordered the execution of 38 Dakota menFebruary 22, 2021

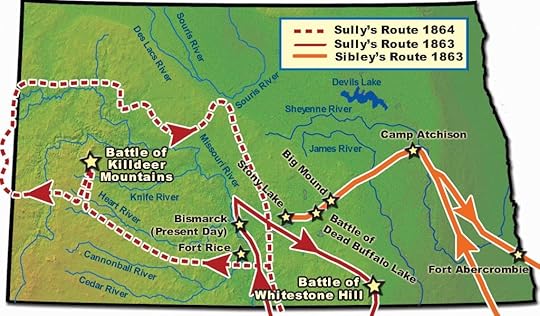

Sully’s Expedition Against the Sioux: Another Military Campaign in the Aftermath of the Dakota War

“I hope you will not believe all that is said of ‘Sullys’ successful expedition,’ against the Sioux. I don’t think he ought to brag of it at all, because it was, what no decent man would have done, he pitched into their camp and just slaughtered them . . . he killed very few men and took no hostile ones prisoners . . . if he had killed men instead of women and children, then it would have been a success . . .”

– Samuel J. Brown to Joseph R. Brown, November 13, 1863

Major General Alfred H. Sully. Image Source: MNHS Collections

Major General Alfred H. Sully. Image Source: MNHS CollectionsIn late 1862, after the Dakota Sioux were defeated in the U.S. – Dakota War, Major General John Pope of the Department of the Northwest laid down plans to pursue and punish the Santee Sioux and any other Native peoples living west of Minnesota toward the Missouri River. The military campaign was a two-pronged punitive expedition launched in the summer of 1863 and led by Major Generals Henry H. Sibley and Alfred H. Sully. Sibley’s expedition, which was covered in an earlier post, was considered a success after several engagements that forced a large hunting party of Sioux west of the Missouri River. Sully’s expedition, however, was delayed making him unable to rendezvous with Sibley as originally planned. But, in August of 1863, as Sibley and his men returned home, Sully overcame the delays and prepared to pursue the combined party of Sioux, Yanktons, Yanktonais, and Tetons that had already fled from Sibley.

On August 14, Sully, commanding a force of 1,200 men, departed his advance base at Fort Pierre and headed north along the Missouri River. After finding Sibley’s old camp, Sully learned from his scouts that the Indians Sibley had pursued had recrossed the Missouri River and returned to their hunting grounds near the headwaters of the James River. Then, on September 3, one of the expedition’s advanced battalions came across a large encampment of Indians at a place called Whitestone Hill. Believing he was being surrounded, the commander of the advanced battalion, Major Alfred E. House, engaged in battle with the Indians. Sully arrived with the main force at about 5pm and charged through the center of the encampment. As it was reported, the Indians fought from the numerous hollows and ravines surrounding Whitestone Hill and put up a “very desperate resistance.” Darkness eventually brought an end to the battle. It is estimated that Sully lost 14 killed and 34 wounded while the estimates of Indian losses range from 150 to 300.

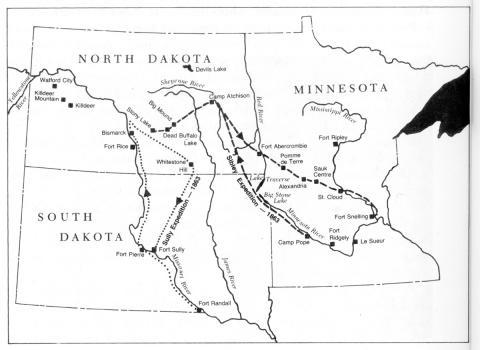

A map of the 1863-64 military campaigns against the Sioux by Sully and Sibley. Map source:

SHSND-ND Studies

A map of the 1863-64 military campaigns against the Sioux by Sully and Sibley. Map source:

SHSND-ND Studies

Over the next two days, Sully’s men completely destroyed the lodges left behind by the Indians and took 156 prisoners, most of whom were women, children, and the elderly. Sully reported that the Battle of Whitestone Hill had been a success and returned to his base on the Missouri River. However, as reported in a letter to his father, interpreter Samuel J. Brown said of the battle, “I hope you will not believe all that is said of ‘Sullys’ successful expedition,’ against the Sioux. I don’t think he ought to brag of it at all, because it was, what no decent man would have done, he pitched into their camp and just slaughtered them . . .”

The following spring, Major Pope in St. Paul issued new orders for Sully’s operation. The first part of the plan was to provide for the construction of four military garrisons along the Missouri River in order to secure communication routes to the goldfields. The second, and greater part of the plan was a military expedition against the whole Sioux nation. In July 1864, after learning that an Indian force of Tetons, Yanktonais, and some Santee Sioux crossed to the west of the Missouri River, Sully and his men, including a detachment of Minnesota soldiers, headed west along the Cannonball River. On July 28 they encountered a large Indian encampment on the side of a high hill known as Killdeer Mountain. Sully made his advance with slight opposition. As his column of soldiers grew closer to the Indian encampment the U.S. soldiers dismounted and were deployed as skirmishers at close intervals. The combined forces of Sioux made what historian William Folwell called a “vigorous but desultory opposition” before retreating from the field. The women and children fled to the mountains leaving large amounts of provisions behind. In the Battle of Killdeer Mountain, Sully’s losses are estimated at five killed and ten wounded while Indian losses are estimated between thirty-one and one hundred fifty killed or wounded.

The 8th Minn. Infantry (Mounted) in the Battle of Ta-Ha-Kouty (Killdeer Mountain) by Carl Ludwig Boeckmann. Image Source: MNHS Collections

The 8th Minn. Infantry (Mounted) in the Battle of Ta-Ha-Kouty (Killdeer Mountain) by Carl Ludwig Boeckmann. Image Source: MNHS CollectionsAfter destroying the Indian’s provisions and returning to their main camp on the Heart River, Sully’s expedition continued west through the Badlands. On August 8 and 9, the U.S. soldiers encountered moderate resistance from the Sioux who fired arrows at them from a safe distance. Sully repulsed the assaults with cannon and rifle fire while traveling four or five miles through rugged terrain. When Sully’s expedition reached a large, level plain, he was able to finally disperse the Indians. Referred to as the Battle of the Badlands, it was probably more of a running skirmish. From the perspective of the Sioux, they had succeeded in harassing the U.S. soldiers, slowed their advance, and deprived their horses of water.

When Sully’s expedition reached Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone River on August 12, they discovered that the Sioux had stampeded or stolen all but two of the horses belonging to the fort. Without horses, and with his men worn-out, Sully decided to abandon his campaign against the Sioux. The expedition returned to Fort Rice where they arrived on September 9, 1864. The Minnesota brigade, relieved of its duty, marched to Fort Ridgely where they arrived on October 8 after marching a total of 1,625 miles in four months and three days.

While some, like Sully and Sibley, declared the 1863-1864 punitive expeditions a success that punished the Sioux for their role in the Dakota War and protected the Minnesota settlements, others saw it as an expensive endeavor that unnecessarily punished innocent people. It was argued that the expeditions were too sweeping and indiscriminate and that the money would have been better spent if given to the Indians in annual installments. In fact, in his annual report in 1866, Commissioner of Indian Affairs D.N. Cooley, as summarized by William Folwell, declared that, “the Sioux generally had not been treated fairly by the government and that the forfeiture of all their annuities by the act of Congress of February 16, 1863, was unjust to a large number who had taken no part in the outbreak of 1862 . . .” Cooley went on to “recommended that Congress at once restore to [the Sioux] the gross sums forfeited in 1863,” for the “justice” of those who had not participated in the Dakota War, and for the “mercy” of the sufferers at Crow Creek and Davenport. Perhaps it’s time that Cooley’s recommendation is revisited.

Read Commissioner of Indian Affairs D.N. Cooley’s entire report.

Sources:

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 2. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1924.

Wikipedia. “Battle of the Badlands.” Last edited January 8, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Badlands.

Keenan, Jerry. “The Battle of Whitestone Hill.” HistoryNet. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://www.historynet.com/battle-whitestone-hill.htm.

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

February 14, 2021

My Instagram Live Interview with Oanh Jordan

I recently had a great conversation with Oanh Jordan, founder of Tiny Triumph Co. and the host of Tea Talks. Check it out to learn more about my experience as a writer, publisher, and founder of my own press History Through Fiction.

Click here to watch on Instagram.

January 19, 2021

The Punitive Expedition of Henry Sibley: Reevaluating the “Success” of his Campaign

August 7, 1863. – We had three desperate engagements with 2,300 Sioux warriors, in each of which they were routed and finally driven across the Missouri with the loss of all their subsistence. Our loss was small, while at least one hundred and fifty savages were killed and wounded.”

H.H. Sibley, Brigadier General, Commanding

Brigadier General Henry Hastings Sibley. MNHS Collections.

Brigadier General Henry Hastings Sibley. MNHS Collections.It is relatively well-known that Henry Hastings Sibley—former governor of Minnesota; former fur trader for the American Fur Company—was the military commander in charge of U.S. forces during the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. Following the war, Sibley also established and chaired the military commission that sentenced 303 men to death by hanging, which ultimately resulted in the execution of 38 Dakota in Mankato on December 26, 1862. But what is lesser known, or lesser publicized, is that the war did not end with the hangings in Mankato and neither did Sibley’s role in it.

Following their defeat at The Battle of Wood Lake, the Dakota, many of whom did not participate in war, had to decide whether to flee their homeland or surrender themselves to U.S. forces. According to historian William Watts Folwell, about 1500 of the Lower Sioux surrendered while about 800 “scattered over the prairies between the Red River and the Missouri, concentrated for the winter on the Missouri River near Fort Rice.” The Upper Sioux, or Santee, who numbered 4,026 people on the 1861 annuity roles and lived along the upper half of the Minnesota River Valley, lingered near their villages before departing north to establish winter camp near Devil’s Lake.

Learn more about Henry Hastings Sibley

Believing the Dakota who escaped to the west were renegades that would align themselves with the Yankton, Yanktonai, and Teton, Sibley estimated that another Indian war was imminent. In October, 1862, he sent a warning to his commanding officer, Major General John Pope, that 2,200 Sioux warriors would soon descend upon the Minnesota settlements. Pope agreed with Sibley’s prediction and quickly drew up plans for a military campaign against the Santee Sioux, including the Yanktons, Yantonais, and Teton in the western territories. According to the plan, which was approved by the war department, the U.S. would send two advancing columns, “one, largely of infantry, to move from the neighborhood of Fort Ridgely northward to Devil’s Lake; the other, mostly of cavalry, to ascend the Missouri Valley from Fort Randall, to cut off a retreat beyond that river, and at length to diverge northeastward toward Devil’s Lake.” The column of infantry was to be led by Henry Sibley.

The following summer, Sibley readied his column to head west from Camp Pope, located at the confluence of the Minnesota and Redwood rivers. Stretching five miles long, the column departed on June 16, 1863, and consisted of 3,320 soldiers, 225 wagons, and several hundred cattle in order to “furnish beef on the hoof.” The column reached a point about forty miles southeast of Devil’s Lake on July 18 where they were informed by Red River buffalo hunters of a large group of Sioux who had recently left Devil’s Lake and were camped about seventy-five miles to the west. Sibley took his column to the southwest and located the large encampment of Sioux on July 24. As Sibley set up camp, a large number of Sioux could be seen to the west occupying a hill which became known as “Big Mound.”

A map showing the military expeditions of Generals Sibley and Sully, 1863-64. By Alan Ominsky. From Kenneth Carley, The Dakota War of 1862, 1976.

A map showing the military expeditions of Generals Sibley and Sully, 1863-64. By Alan Ominsky. From Kenneth Carley, The Dakota War of 1862, 1976.Sibley and his scouts met with the Sioux on the western hills, but negotiations broke down when Dr. Josiah S. Weiser, a surgeon for the cavalry regiment, was shot through the back. The groups quickly dispersed and Sibley ordered an attack on the Native encampment. Using superior artillery from elevated positions and several charges of cavalry and infantry, Sibley forced the Sioux to retreat after a battle lasting only a few hours. Several regiments pursued the fleeing Sioux for fifteen miles from the original point of attack. After nightfall, the pursuing regiments set up a temporary camp and returned to the main column the next day. The Battle of Big Mound resulted in three U.S. soldiers killed, and nine or more Sioux killed.

On July 26, after a day of rest, Sibley’s column continued their pursuit of the retreating Sioux. After a march of fourteen miles, which was strewn with gear and provisions abandoned by the Sioux, Sibley set up camp at the shore of a lake where there lay the head of a dead buffalo, earning it the name Dead Buffalo Lake. Shortly thereafter, mounted Sioux appeared on the hills surrounding the lake as if threatening an attack. Sibley deployed skirmishers who were supported by cavalry and artillery. The Sioux were quickly repulsed and the battle resulted in the loss of one U.S. soldier killed and 1–15 Sioux combatants killed.

As the Sioux continued their retreat toward the Missouri River, Sibley continued his pursuit. On July 27, Sibley’s column marched twenty-three miles where they camped at Stony Lake. Early the next morning, July 28, as Sibley’s column began their march, they were encountered by great numbers of Sioux on their front and flanks. Like he had before, Sibley deployed artillery which kept the Sioux at a distance. This was followed by infantry charges that dislodged the Sioux from several hills and forced their retreat. The Battle of Stony Lake resulted in 0 U.S. soldiers killed and an estimated 3 or fewer Sioux losses.

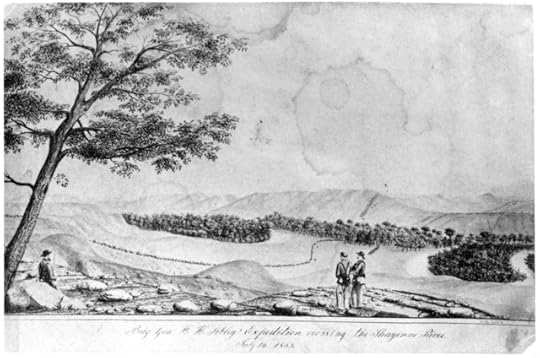

Brig. Gen. H. H. Sibley’s Expedition crossing the Shayenne River by H.F. Knieff. MNHS Collections

Brig. Gen. H. H. Sibley’s Expedition crossing the Shayenne River by H.F. Knieff. MNHS CollectionsAfter the Sioux abandoned the field at Stony Lake, Sibley’s column marched eighteen miles to the Apple River and then another fifteen miles the next day until they reached the Missouri River. On July 29, Sibley sent two howitzers and his mounted Rangers forward to try and prevent the Sioux from crossing over the Missouri River. However, most of the Sioux had crossed the day before and those remaining hastily made their way to the western side of the river before Sibley’s artillery could have much impact. During this time, two U.S. soldiers who became separated from the main column were captured and killed. On July 30, Sibley sent several detachments forward to recover the bodies and burn the wagons and property on the eastern side of the river left behind by the Sioux.

On July 31, short on supplies and exhausted from weeks of pursuit, Sibley ordered an end to the campaign. By driving the large encampment of Sioux—estimated between 10,000 and 12,000 people—across the Missouri River, Sibley declared his expedition a complete success that would prevent any further attacks by Indians on the people of Minnesota. In a letter to his officers and soldiers dated July 31, 1863, Sibley stated, “It would be a gratification if these remorseless savages could have been pursued, and received for their crimes and barbarities such a full measure of punishment as they merited, but men and animals are alike exhausted after so long a march, and a farther pursuit would only be futile and hopeless.” The main column returned to Fort Snelling on September 13 after traveling 1039 miles in just under three months and having lost six men killed. Sioux losses have been estimated between 13 and 150, while they also endured the loss of a large amount of their provisions left behind in their retreat.

General Henry Sibley received much praise for the results of his punitive expedition against the combined group of Santee, Yankton, Yanktonai, and Teton Sioux during the summer of 1863. Writing in 1864, historian Harriet E.B. McConkey declared, “If we look to historic facts, we find no more successful campaigns against the Indians, than have been those of Gen. Sibley . . . The name of Henry H. Sibley will live on history’s unsullied page. Posterity will laud him, when those of his calumniators will be lost in the great whirlpool of oblivion” (McConkey, 377).

Looking back, it has become clear that Sibley’s punitive expedition was sparked by chaos and panic following the U.S. – Dakota War and fueled by the pervasive racist ideology of the time. Those whom Sibley and his column pursued were not a war party, but a community of nomadic hunters that were not involved in the attacks against the Minnesota settlements the previous summer. While it is unclear why Dr. Josiah S. Weiser was assassinated at the beginning of negotiations, the Sioux soldiers involved in battle were not engaging in war. Rather, they sought to delay the pursuit of a large column of sufficiently trained and armed U.S. soldiers in order to allow their women, children, and elderly to retreat to safety. Unfortunately for the Sioux, they lost dozens of lives and immeasurable amounts of goods and property in the process. Furthermore, it was only the beginning of a decades-long conflict with the United States.

Sources:

Folwell, William Watts. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 2. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society, 1924.

West, Nathaniel. The Ancestry, Life, and Times of Hon. Henry Hastings Sibley. United States: Pioneer Press, 1889.

McConkey, Harriet E. Bishop. Dakota War Whoop, Or, Indian Massacres and War in Minnesota, of 1862-‘3. United States: Published for the author, 1864.

“Battle of Stony Lake,” Wikipedia, Accessed Jan. 17, 2021, Last Updated Jan. 8, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_....

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.