Colin Mustful's Blog, page 11

May 31, 2020

A State of Panic: How the Citizens of Wisconsin Responded to the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862

“Given a quantity of gasoline, it requires but the application of a match to produce an explosion; the match taken by itself would be harmless. In the outbreak we are studying the abnormal state of the public mind supplied the gasoline; the application of some report of Indian outrage, however improbable or foolish it might be in itself, produced the panic.”

M.M. Quaife, “The Panic of 1862 in Wisconsin”

While the U.S. – Dakota War wreaked havoc across the state of Minnesota in August and September of 1862, causing thousands to flee their homes in search of safety, its effects were not limited to Minnesota alone. Just to the east, in Wisconsin, a state where many Minnesotans had migrated from, news of the war caused a similar response. Though the threats of danger in Wisconsin were unfounded, exaggerated, and often baseless, communities throughout the state reacted with panic and fear, fleeing their homes and seeking refuge. And though the hysteria, looking back, seems quite unreasonable, the conditions for a sudden escalation of an emotionally driven outburst were always there—not much unlike what we see today in the streets of Minneapolis and St. Paul.

On April 15, 1861, following the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln called upon 75,000 volunteers to serve in the Union army in defense of what some would call Southern aggression. This was the beginning of the American Civil War. More calls for troops followed and by July of 1861, Congress authorized 500,000 additional volunteers.

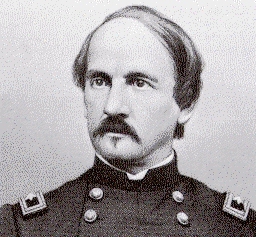

Wisconsin Governor Louis P. Harvey

Wisconsin Governor Louis P. Harveydrowned in the Tennessee River

while bringing medical supplies to

troops following the Battle of Shiloh

Wisconsin answered the call for volunteers sending several regiments. Though it was at the time still considered a frontier state with a meager population of eight hundred thousand, thirty thousand young men were sent to the front. This, of course, created a sense of tension among Wisconsinites as they read country newspapers that carried weekly long and ever-growing lists of casualties. By 1862, when volunteering slowed, conscription resulted in draft riots in some Wisconsin communities. In Milwaukee, troops had to be called in to preserve the peace. Then, on April 19, 1862, the governor of Wisconsin, Louis P. Harvey, drowned in the Tennessee River while bringing medical supplies to the troops injured in the Battle of Shiloh.

Thus, when a contingent of Dakota soldiers attacked and killed several hundred citizens living in south and southwestern Minnesota, sparking the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, Wisconsinites, upon hearing the news, released their growing apprehension in a show of community by community statewide panic. Many believed that Native populations in the region were after their destruction and that a massacre was imminent. In St. Croix Falls and surrounding counties it was reported that in some of the towns midnight alarms had occurred, with the people rushing from their beds and houses in fear. In Menomonie, for four days beginning August 29, a constant stream of men, women, and children rushed into the city, all fully convinced that the Native people were close behind them murdering every white person they could. In eastern counties, citizens reacted to false reports, such as the burning of Cedarburg, by flooding into rendezvous points like Port Washington, Waukesha, and Milwaukee.

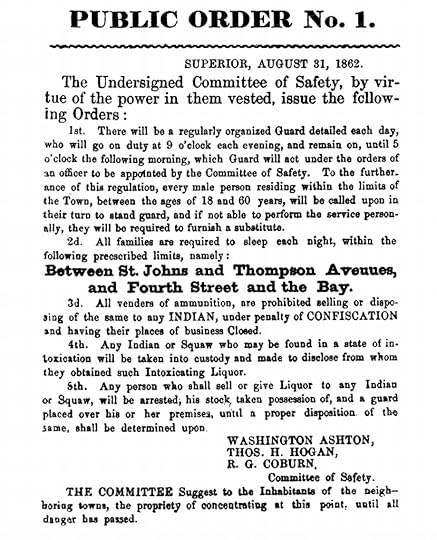

In response to the panic, Governor Edward Salomon organized a committee of public safety that issued Public Order No. 1 on August 31. The order called upon every male inhabitant between the ages of 18 and 60, to take turns as a part of a nightly guard. It also asked that all families sleep within certain town limits for protection while the order also forbade the sale of alcohol or ammunition to any Native person. After the Public Order was issued, Governor Salomon reached out to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton declaring, “Appeals are daily made to me for arms and ammunition. Families are leaving their homes for fear of the wandering bands.” He also recalled Captain Maurice Samuel of the First Wisconsin Infantry from Kentucky to quell any potential violence.

At the time of the U.S. – Dakota War, there were about 9,000 Native peoples living in the state of Wisconsin, most of whom were confined to reservations. The Native peoples had shown themselves to be peaceful and were quite loyal to the government. Following Lincoln’s call for volunteers, many Natives in Wisconsin offered their services in the war against the South. Though authorities would not allow full companies of Native soldiers, the Natives did not fear conscription and about five or six hundred, out of nine thousand, served for the Union Army.

Whatever fear the whites had of the Natives in Wisconsin was based on prejudice or false reports. For instance, on September 8, the La Crosse Weekly Democrat reported that the Lewis Valley settlement had been burned by Indians. However, no such destruction took place and no one could actually report having seen a Native inhabitant. The editor of the Weekly Democrat estimated that there wasn’t a Native within seventy-five miles of La Crosse, and commented on the excitement writing, “every bush has an Indian behind it, every moan of the wind is an Indian signal, the hoot of the owl is nothing but the infuriated whoop of an army of savages.”

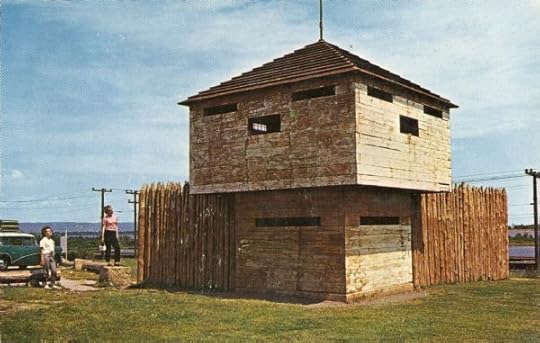

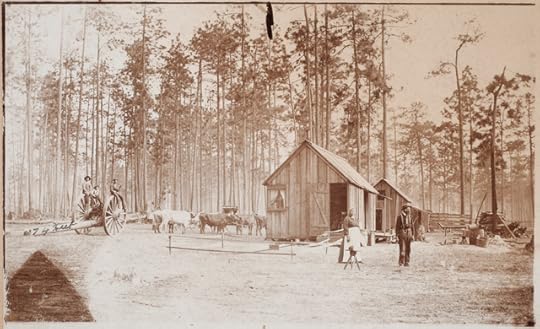

The replica of a stockade that was built in Superior, WI, in 1862 in response to the U.S. – Dakota War. Additionally, a Home Guard was organized and the Governor sent Company B of the 8th Wisconsin regiment to protect the area. Image from the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

The replica of a stockade that was built in Superior, WI, in 1862 in response to the U.S. – Dakota War. Additionally, a Home Guard was organized and the Governor sent Company B of the 8th Wisconsin regiment to protect the area. Image from the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society. Whole settlements were evacuated, west to east across the state, but as time passed, people realized their fears were exaggerated and then began returning to their homes. In Wisconsin it became known as the Indian Scare of 1862. Ultimately, there was no attack, no destruction, and no reason for panic. But what happened there was not unprecedented nor even uncommon. When conditions are ripe, and a spark is provided, emotion, rather than reason, motivates action. Things have changed a lot since 1862, when Minnesota went through one of its most challenging epochs, but people have not. We all want and need safety—for ourselves and for our families. We all want hope for the future. But when that safety and hope is threatened over an extended period of time, there is no stopping the reaction that follows.

Sources:

M. M. Quaife, “The Panic of 1862 in Wisconsin”, The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Dec., 1920), pp. 166-195

Wisconsin Historical Society. Wisconsin Local History & Biography Articles; Sheboygan Daily Press; Sheyboygan, WI; July 1, 1932; viewed online at https://www.wisconsinhistory.org on May 29, 2020.

“President Lincolin’s 75,000 Volunteers”, Wikipedia, Last Updated April 8, 2020, accessed on May 30, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/President_Lincoln%27s_75,000_volunteers.

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

May 23, 2020

Find my books at your local library!

Although many libraries have their doors closed right now, most are continuing to serve their communities through virtual programs, ebook and audio book lending, and curbside pick-up of physical books. As we all wait for libraries to reopen, it’s important to remember that books and services remain available as long as we adjust to the new guidelines. Today, I’m writing to remind readers that my books are free and available to you at many libraries throughout Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. Below is a list where you can find my books in your local community. If your local library does not carry my book, remember that you can always contact your library and ask for my books through interlibrary loan or by making a purchase suggestion.

Stay safe, and keep reading!

Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850

Anoka County Library

Northtown Library

Columbia Heights Public Library

Arrowhead Library System

Babbitt Public Library

Grand Marais Public Library

International Falls Public Library

Great River Regional Library

Delano Public Library

Monticello Public Library

Hennepin County Library

Franklin Library

Downtown Central Library

Eden Prairie Library

Kitchigami Regional Library

Longville Public Library

SELCO – Southeastern Libraries Cooperating

Caledonia Public Library

Lake City Public Library

IFLS Library System

Colfax Public Library

Cumberland Public Library

Lakeshores Library System

Burlington Public Library

Northern Waters Library Service

Frank B. Koller Memorial Library

Larsen Family Public Library

Winnefox Library System

Wild Rose (Patterson Memorial) Public Library

College of St. Scholastica Library

Lake Superior College

Erickson Library

Mesabi Range Community and Technical College

Virginia Campus Library

University of Minnesota Duluth

Kathryn A. Martin Library

Fate of the Dakota: A Novel and Resource on the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862

Arrowhead Library System

Silver Bay Public Library

Two Harbors Public Library

Dakota County Library

South St. Paul Public Library

East Central Regional Library

Mora Public Library

Great River Regional Library

Howard Lake Public Library

Rockford Public Library

Kitchigami Regional Library

Bemidji Public Library

Blackduck Public Library

Longville Public Library

Lake Agassiz Regional Library

Bagley Public Library

Moorhead Public Library

Pioneerland Library System

Atwater Public Library

Benson Public Library

Kerkhoven Public Library

Ortonville Public Library

Plum Creek Library System

Fulda Memorial Library

Minneota Public Library

Windom Public Library

SELCO – Southeastern Libraries Cooperating

Blooming Prairie Branch Library

Caledonia Public Library

Harmony Public Library

Preston Public Library

Traverse des Sioux Library Cooperative

Dyckman Free Library

Hanska Public Library

Janesville Public Library

Waseca Public Library

Wells Public Library

Viking Library System

Morris Public Library

Minnesota Historical Society

Gale Family Library

Grace at Spirit Lake

Anoka County Library

Columbia Heights Public Library

Arrowhead Library System

Silver Bay Public Library

Two Harbors Public Library

Great River Regional Library

Howard Lake Public Library

Rockford Public Library

Kitchigami Regional Library

Brainerd Public Library

Cass Lake Public Library

Longville Public Library

Lake Agassiz Regional Library

Barnesville Public Library

Moorhead Public Library

Pioneerland Library System

Atwater Public Library

Benson Public Library

Kerkhoven Public Library

Ortonville Public Library

Plum Creek Library System

Fulda Memorial Library

Minneota Public Library

Windom Public Library

Marshall-Lyon County Library

Ramsey County Library

Maplewood Library

Shoreview Library

SELCO – Southeastern Libraries Cooperating

Blooming Prairie Branch Library

Lake City Public Library

Harmony Public Library

Preston Public Library

Traverse des Sioux Library Cooperative

Dyckman Free Library

Hanska Public Library

Watonwan Public Library

Waseca Public Library

St. Peter Public Library

Viking Library System

Morris Public Library

Arnolds Park Library

Cedar Rapids Public Library

Emmetsburg Public Library

Laurens Public Library

Milford Memorial Library

Ruthven Public Library

Spirit Lake Public Library

Bethany Lutheran College

Memorial Library

Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College

Ruth A. Myers Library

Normandale Community College Library

Riverland Community College

Austin Campus Library

Vermillion Community College Library

Minnesota Historical Society

Gale Family Library

Ceding Contempt: Minnesota’s Most Significant Historical Event

Arrowhead Library System

Silver Bay Public Library

Two Harbors Public Library

East Central Regional Library

Mora Public Library

Great River Regional Library

Howard Lake Public Library

Rockford Public Library

Kitchigami Regional Library

Blackduck Public Library

Park Rapids Public Library

Longville Public Library

Wadena Public Library

Pioneerland Library System

Atwater Public Library

Benson Public Library

Kerkhoven Public Library

Ortonville Public Library

Plum Creek Library System

Fulda Memorial Library

Minneota Public Library

Windom Public Library

SELCO – Southeastern Libraries Cooperating

Blooming Prairie Branch Library

Lake City Public Library

Harmony Public Library

Preston Public Library

Traverse des Sioux Library Cooperative

Dyckman Free Library

Hanska Public Library

Waseca Public Library

Wells Public Library

Viking Library System

Morris Public Library

Bethany Lutheran College

Memorial Library

The Newberry Library, Chicago

May 13, 2020

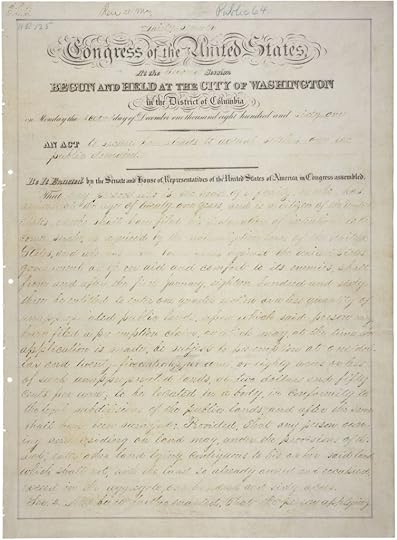

The Homestead Act of 1862: It’s place within the U.S. – Dakota War

By the year 1862, the majority of Native peoples in Minnesota had been relegated to life on a reservation. The Dakota in particular, had ceded millions of acres of land and were moved to a stretch of land that was twenty miles wide along the Minnesota River. In 1858, that land was reduced to an area just ten miles wide. Meanwhile, long before land cession treaties with the Dakota and Ojibwe, the United States government was envisioning ways to settle that land with its white, Euro-American population.

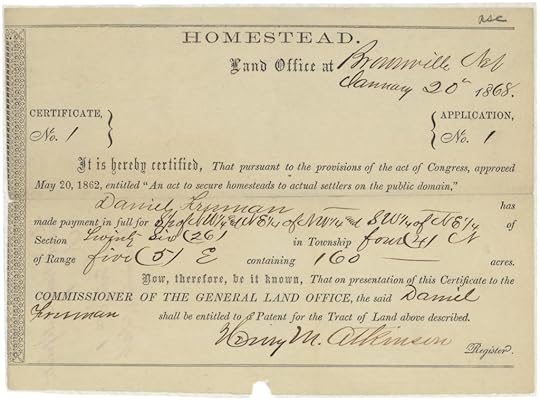

Original Copy of the Homestead Act of 1862; Image from the National Archives

Original Copy of the Homestead Act of 1862; Image from the National ArchivesOn May 20, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act of 1862. According to the Act, any citizen head-of-household, or intended citizen, was entitled to 160 acres of public land if they settled and cultivated the land for a minimum of five years. If the citizen met these stipulations the land was free. If they intended to stay for only six months, the citizen could buy the land for $1.25 per acre.

Debates and ideas about land settlement existed in the United States since its founding. Even the Constitution declared lands outside the thirteen colonies to be public lands owned by the government. The debate about free land for settlers came to the forefront with the establishment of the Free Soil Party in 1848. As a part of their platform, the party stated that “public land . . . should be granted in limited quantities, free of cost, to landless settlers” (Anderson, 118). A year later, Andrew Johnson, who was a U.S. Representative at the time, introduced the homestead bill, which granted 160 acres of free soil as an inalienable home to every citizen head of household.

Though Johnson’s bill did not pass, more homestead bills followed and were passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1852, 1854, and 1859. However, each one was struck down by the Southern dominated Senate who feared that a homestead act would jeopardize the plantation system and lead to more states opposing slavery. Then, in 1860, a homestead bill was approved by Congress, but vetoed by President Buchanan who called it unfair, uneven, and unconstitutional.

Following the secession of southern states in 1860 and 1861, along with their members of Congress, nearly all opposition to the Homestead Act was removed. In 1862, it was passed by a vote of 107 to 16 in the House and 33 to 7 in the Senate. It was signed by President Lincoln and went into effect on January 1, 1863.

In Minnesota, the law had an immediate effect. According to historian William Watts Folwell, “in the three-year period from 1863 to 1865 inclusive, 9,529 homestead entries for 1,237,722.13 acres were made in Minnesota” (Folwell, 331). Extending that view, Folwell reports that “between May 20, 1862, and June 30, 1880, there were made in Minnesota 62,379 entries of 7,346,038.96 acres.” As for the nation as a whole, it is reported that 10% of all land—some 270 million acres—was homesteaded. The homesteading period lasted until 1974 when Kenneth Deardorff, who filed an 80-acre claim in southern Alaska, was recognized as the final homesteader.

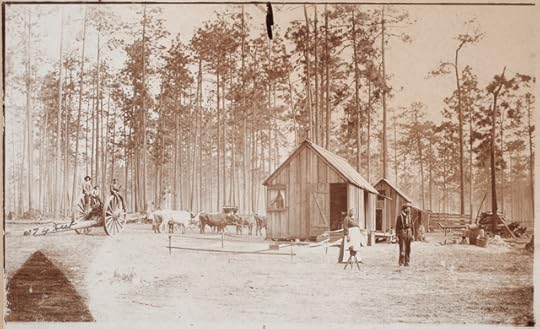

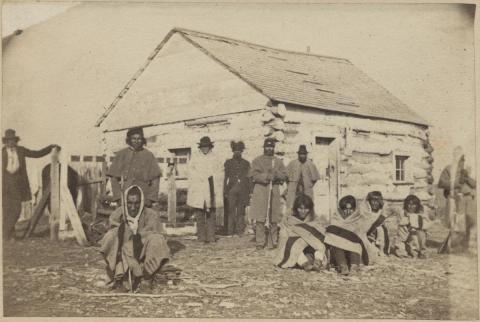

A family of homesteaders in Minnesota, circa 1880; Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections

A family of homesteaders in Minnesota, circa 1880; Image from the Minnesota Historical Society CollectionsIt’s important to note that while the Homestead Act provided a home and a sustainable way of life for many American settlers, the law was exploited by land speculators and corporations who sought, through fraud and corruption, to accrue land and wealth as quickly and easily as possible. Many used proxy filings to obtain land for six months at $1.25 an acre and then turned around and sold it at much higher rates. Some businesses hired individuals to make a show of settlement for the full five year period, only to give the land to their employer for a prearranged sum. According to Folwell, “it was a bold and impudent fraud practiced upon a generous nation,” and “by means of this process many thousands of square miles of pine lands have been acquired . . .” (Folwell, 332).

Homestead Certificate of Daniel Freeman, the first Homesteader; Image from the National Archives

Homestead Certificate of Daniel Freeman, the first Homesteader; Image from the National ArchivesAs reported by the National Park Service, four million claims were made under the Homestead Act, and it is estimated, as of 2007, that there were 93 million homesteader descendants still living. To fully understand the Homestead Act and all its implications would require a much deeper study. Nevertheless, a brief consideration of its context sheds light on our history and its significance for us today. In 1862, when the Homestead Act was passed and the U.S. – Dakota War broke out, the Native peoples of Minnesota were part of a much larger, insatiable machine. For more than eighty years before the war, the United States already laid plans to acquire and settle Native lands, and for more than a century after the war those plans came to fruition through the Homestead Act.

The Homestead Act of 1862 was reflective of an industrious people and a young ambitious nation. The Act itself, however, merely validated sentiments and actions of a nation already set on an inevitable outcome. While such a policy and its results cannot be reversed, it’s imperative upon us, in hindsight, to look beyond our history (in this case the U.S. – Dakota War) as a microcosm of conflicting interests. It was wrought by a narrow-minded vision of conquest and settlement with little thought for the people it conquered and the legacy for those people’s children. As we rethink our world and our values, we should do so with the full understanding of what brought us here.

Sources:

William D. Green, The Children of Lincoln: White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity in Minnesota 1860 – 1876, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

William Watts Folwell, A History of Minnesota, Vol. 2, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1924)

Hannah L. Anderson, “That Settles It: The Debate and Consequences of the Homestead Act of 1862,” in The History Teacher, Vol. 45, No. 1, (November 2011), pp. 117–137.

“Homestead Acts,” Wikipedia, Accessed May 12, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homestead_Acts.

“Homesteading by the Numbers,” National Park Service: Homestead National Monument of America, Accessed May 13, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/home/learn/historyculture/bynumbers.htm.

May 11, 2020

Virtual Author Event: Teaming up to Support Local Museums

Though current circumstances have put a temporary halt to in-person author events, it’s opened up a new world of opportunity for authors and readers to connect. Virtual events, once quite rare, are now being utilized as an effective, affordable, and widely accessible outlet for bookstores, libraries, and museums to engage patrons while maintaining safe social guidelines. While nothing can replace in-person events, it remains important to make adjustments to satisfy the needs of businesses, authors, and readers alike. As we all adjust to our new circumstances, author Colin Mustful is adjusting, too!

Mustful is proud to announce that he has teamed up with The Octagon House Museum in Hudson, Wisconsin, to present a virtual lecture and reading. The author of several historical novels, Mustful will be talking about the historical event that inspired his most recent novel, “Resisting Removal”. Known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy, this relatively unknown event left 400 Ojibwe dead in northern Minnesota and Wisconsin because of the negligence and ill-intents of U.S. government officials. The presentation will include a PowerPoint guided lecture, a reading from Mustful’s novel “Resisting Removal”, and a Q&A with the audience.

To support local museums and historical societies during these difficult times, Mustful will be donating the proceeds of all book sales purchased through his online store to the Octagon House Museum. The author’s online store is found at https://colin-mustful.square.site/ .

When: Thursday, May 14, 7pm Central Time

Where: Google Meet – https://meet.google.com/yqx-dpog-dgj

Phone number (if no internet access) 1-530-395-0813

Pin (to be entered after dialing): 172 415 020#

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/events/848299878985089/

More Info: Octagon House Museum

May 6, 2020

The “Moscow Expedition”: Exploitation of the Dakota and Ho-Chunk Exiled to Crow Creek

April 8, 2020

Sibley to Congress: “You must very soon suffer the consequences of a bloody and remorseless Indian war.”

Henry Hasting Sibley, Image from the MNHS Collections

Henry Hasting Sibley, Image from the MNHS CollectionsHenry Hastings Sibley is one of the most prolific figures in the history of Minnesota. He arrived in Minnesota in 1834 as the regional manager of the American Fur Company’s “Sioux Outfit.” While living at Mendota, he established ties with local Dakota and voyageur communities and quickly grew to be one of the most prominent traders in the region. As the fur trade dwindled, Sibley moved toward politics and in 1849, when Minnesota became a territory, he was elected Minnesota’s territorial delegate to Washington. Several years later, Sibley was elected as Minnesota’s first governor. Then, when war broke out with the Dakota in 1862, Sibley served as colonel to lead U.S. forces against the Dakota. In the aftermath, he served as the head of the military commission that put Dakota men on trial and, as brigadier general, he led several punitive military expeditions against the Dakota in 1863 and 1864.

From Sibley’s arrival in 1834 to his death in 1881, Minnesota changed drastically from an unorganized territory that was home to Native Dakota and Ojibwe peoples, to a State in the Union with booming industry, abundant agriculture, and a white population of more than 780,000 people. It is intriguing to consider Sibley’s role in Minnesota’s transformation, especially as it relates to the Dakota people. In 1839, Sibley entered into a kinship relationship with a Dakota woman named Red Blanket Woman, the daughter of Bad Hail. A year later the couple had a daughter named Helen Hastings or Wahkiyee. Sibley was also known to be friends with the Dakota elder Little Crow and often joined hunting parties with the Dakota. During this time Sibley wrote about his hunting expeditions for the New York magazine, Spirit of the Times, under the pen name “Hal a Dacotah.”

Sibley, however, exploited his kinship ties with the Dakota, eventually becoming the wealthiest trader in the region. Relying on his political influence, Sibley was a negotiator of the 1851 Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota that ceded thirty million acres of Dakota land and for which he was the most prosperous benefactor. Eleven years later, Sibley led U.S. forces that defeated the Dakota war effort and he headed the military commission that sentenced three hundred three Dakota men to death by hanging, eventually executing thirty-eight in Mankato on December 26, 1862.

With all that to consider, I’d like to present a speech that Sibley made before Congress in August of 1850, while representing Minnesota as a territorial delegate. The speech is interesting because Sibley acknowledges the deceit and wrongdoing done to Native populations while accurately predicting the outbreak of war between U.S. and Native forces. Sibley recognized the ineffectiveness of the treaty system stating, “I will venture the assertion, that not one in ten of the treaties made will be found to have been carried out in good faith.” And yet, a year later he orchestrated the Sioux treaties that removed the Dakota from their land, forced them onto a reservation, and engendered ill-will that culminated in the U.S. – Dakota War.

Sibley’s Mendota Home, now a state historic site.

Sibley’s Mendota Home, now a state historic site.To be clear, Sibley’s tone was incredibly patronizing, often referring to Native populations as “creatures” or “savages” while also presuming an air of superiority and promoting a policy of assimilation. Nevertheless, Sibley spoke strongly on behalf of Native populations and called out government agents as being ignorant and unsympathetic.

Sibley concluded his speech with a stark and prophetic warning: Your pioneers are encircling the last home of the red man, as with a wall of fire. Their encroachments are perceptible, in the restlessness and belligerent demonstrations of the powerful bands who inhabit your remote western plains. You must approach these with terms of conciliation and of real friendship, or you must very soon suffer the consequences of a bloody and remorseless Indian war. Sir, what is to become of the fifty or sixty thousand savage warriors and their families, who line your frontier, when the buffalo and other game upon which they now depend for subsistence are exhausted? Think you they will lie down and die without a struggle? No, sir, no. The time is not far distant, when pent in on all sides, and suffering from want, a Philip or a Tecumseh will arise to band them together for a last and desperate onset upon their white foes. What then will avail the handful of soldiers stationed to guard the frontier. Sir, they, and your extreme western settlements, will be swept away as with the besom of destruction.

Read in hindsight and within the context of Sibley’s life, this speech is difficult to digest. It is filled with overwhelming prejudice that marked our policy makers of that time while also acknowledging the damaging effects to those being subjugated. Henry Sibley knew the consequences of his actions and yet he proceeded anyway. Perhaps the temptations of wealth and power were too great, or perhaps he saw no other possible result as he, too, was swept away in a wave of progress.

Sibley’s full speech is available through Google Books. It was originally printed in The Congressional Globe, Volume 22, Part 2, Pages 1505 – 1508. The original text is printed verbatim below.

Sources:

“Henry Hastings Sibley,” Minnesota Historical Society: Sibley Historic Site, https://www.mnhs.org/sibley/learn/henry-hastings-sibley

Brian Haines, “More the the Story: Hunting with Hal, A Dacotah,” in Hutchinson Leader, December 16, 2019, https://www.crowrivermedia.com/hutchinsonleader/news/entertainment/more-to-the-story-hunting-with-hal-a-dacotah/article_0e4fd0ee-254b-523e-b818-d977d3bdbd19.html.

William Watts Folwell, A History of Minnesota, Vol. 1, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1922.

Full Text of the Speech

With these remarks, Mr. Chairman, upon the general character of territorial governments, I now proceed to another topic, to which I alluded several weeks since, stating, at the same time, my intention to discuss it at an appropriate period. I refer to our relations with the Indian tribes within our limits, but more especially with those of the Northwest. The subject is one which appeals to the sympathies not only of the people I have the honor to represent, but to those of every American. The solution of the problem which involves the civilization of the remaining Aboriginal tribes, or the alternative of their utter extinction, is intimately connected, also, with the peace and ultimate prosperity of our own Territory. It is for these reasons that I regard it to be my imperative duty, not only to my constituents, but to the Indians themselves, to review briefly the policy of the Government in their intercourse with the latter, and to suggest such a remedy for existing evils, as will, in my judgement, suffice to meet the exigencies of the case. If, unfortunately, the Government shall still persist in its present course, with full knowledge of its unhappy tendency, Minnesota shall at least be freed from any responsibility on that score.

I am aware, sir, that the Commissioner of Indian Affairs is required by law to make an annual exhibit of the affairs of his department, and of the general condition of the Indians within the limits of the United States. But it is equally certain that his report does not receive an attentive perusal from one tenth of the members of either House of Congress. In fact, so far as any legislation is concerned, having for its object the advancement of the tribes in civilization, it may well be asserted that the whole question is banished from these Halls. You have as one of the standing committees of this House, that on Indian Affairs; but if I am not in error, it is no part of the duty assigned to that committee, composed as it is of able and intelligent men, to do more than to act upon the business which may be brought before it. It cannot reasonably be expected of that committee, continually occupied as it is with other duties, that it shall enter into a detailed examination of the condition of each tribe, to ascertain what causes are in operation seriously to affect that condition. But of one face we are all cognizant, and that is, the absolute certainty that the Indians are rapidly diminishing in number. I conceive it to be incumbent upon this Government to find out the cause of this diminution, and to arrest it.

Sir, at an early period of our history, there was much more attention paid to this subject than there now is, and many plans were originated to meliorate the condition of the Indian race. I cannot discover, however that any systematized effort was made to civilize them, or to prepare them for admission into the great American society of freemen. Then, as now, philanthropic and christian associations and individuals were found laboring to evangelize them; but their efforts were then, as they now are, to a great extent abortive and unsuccessful. The policy pursued by the Government was, to make reservations upon which the Indians were to be allowed to reside for an indefinite period, after the title to their lands had been extinguished. So soon as the surrounding region became settled by the whites, these poor creatures, subjected to indignities of every description, treated as outcasts and supplied with intoxicating drinks by unprincipled white men, either dwindled rapidly away, or, forced to sell their reservations, emigrated in a body to a more remote part of the country, only, in the course of a few years, to be resubjected to the same process.

Mr. Chairman, the history of the northern portion of this continent presents one strange fact for our consideration. In the wars of the Greeks, the Romans, and the Franks, and, in more modern times, of the British Empire in India, we read of nation after nation being subjugated, and their territories occupied, but never of their becoming speedily extinct in consequence of a failure on the part of the conqueror to allow them such privileges and such conditions as were indispensable to their existence. It remained for those Anglo-Saxons, who fled to this New World to escape persecution at home, and for their descendants, boastful as they are and have ever been, of their philanthropy and their religion—it remained for them, I say, to show to the world, that while they wrested from the red man the soil which gave him birth, they neither incorporated him into their community as a member, nor bestowed upon him any of those beneficent appliances which were necessary to preserve him, and raise him to a level with themselves. From the days of the Pilgrim Fathers to the present time, there is the same sad story to be repeated, of grievous wrongs inflicted upon this unhappy race.

Sir, history has thus far failed to do justice to the heroic bands, who have struggled so fiercely to preserve their lands and the graves of their fathers, from the grasping hand of the white man. The wars which have so often desolated the frontier, sullied indeed with horrid butcheries and atrocities on the part of the Indians, will, nevertheless, hereafter be referred to as the efforts of a brave and patriotic race to maintain themselves in the position in which Providence had placed them. True, numbers, science, and discipline, prevailed in the end, and the vanquished submitted of necessity to the will of the victor. That will was death, not by the more merciful sword, but by a lengthened course of oppression, of insult, and of degradation.

The system of removing the Indians to the west of the Mississippi originated during the administration of Mr. Monroe, but it was not acted upon to any extent until after General Jackson was elevated to the Presidency. It was then announced as the scheme par excellence, which was to afford “healing to the nations.” And, if it had been carried out according to the original design, with due care and in good faith, by the agents of the Government, it would, doubtless, have been attended with happy effects. But this has not been the case, and the actual result has been to introduce among the bands of wild and noble savages who roam the western prairies, a horde of worthless vagabonds, reeking with the vices, but possessed of none of the virtues of the whites, to breed a moral pestilence in the land, and to contaminate those who were, comparatively speaking, far elevated above them in the scale of existence. If these tribes had been more or less civilized, by the well-directed efforts of the Government itself, before they were called upon to remove, the influence exercised upon the wilder bands, when brought in contact with them, would have been at once elevating and beneficial. Unfortunately, as I have before stated, the very reverse of this has been the case.

Sir, it is my sincere conviction, that of all the Indians who have been removed to the west of the Mississippi, there are very few who entertain kind feelings towards this Government; nay more, who are not its secret or avowed enemies. This is a startling assertion, but it is not the less true. The reason is obvious to any one who is the least acquainted with Indian character. This is to be found in the defective manner in which treaties are negotiated with them, in the unfitness of the individuals too often selected as commissioners, and the little regard manifested by the agents of the Government, in carrying out the stipulations of solemn treaties after they are made. No man, sir, should be appointed to the responsible office of commissioner on the part of the Government, to negotiate with the Indians for the purchase of their lands, unless he be of high character, and possessed of a practical knowledge of the peculiar characteristics of that race. If the act of making a treaty is not to be looked upon as a mere mockery or a farce, every stipulation contained in it, and every pledge made by the authorized agent of the Government, should be as scrupulously fulfilled as if the negotiation had been entered into with a sovereign and independent nation. Nay, sir, the very fact that the weaker party are powerless to redress their grievances, and are entirely dependent upon the sense of justice of the other party, appeals strongly to this Government to avoid the appearance of a desire to shrink from the performance of its obligations, voluntarily incurred. I regret to say, that such magnanimity as this is too seldom displayed. On the contrary, when commissioners are appointed who do no reside on the frontier, and who have little or no sympathy with the Indians, they do not hesitate to overcome the natural repugnance of the savages to part with their lands, by making promises which they know will never be performed, but which the poor victims believe to be made in good faith. The commissioners, having accomplished their object by obtaining the signature of the chiefs, plume themselves upon having made a favorable treaty, leaving the miserable savages to find out in due time that they have been betrayed and deceived. This first breach of faith is, of course, charged upon the Government itself. Then there arises another just cause of complaint. The treaty stipulations, albeit they have been duly sanctioned by the Senate, are not fulfilled. I will venture the assertion, that not one in ten of the treaties made will be found to have been carried out in good faith. If they were, sir, your streets would not be thronged every year with delegations from distant bands, to seek justice at the hands of their “Great Father.” Yea! Old men making weary and toilsome pilgrimages of thousands of miles, to supplicate that their righteous claims may not be longer disregarded. One instance of this kind occurs to me, in which the Government bound itself to pay $5,000 per annum to a certain band in 1837, and, to this day, although the sum has been regularly estimated for, and appropriated by Congress, that band has never received on cent of this annuity; nor has it been expended for their benefit. This is but one case in a thousand that might readily be cited.

Sir, when these tribes, thus suffering under real or supposed grievances, are herded together like cattle, preparatory to their removal from their own lands to a far-distant dwelling-place; when, treated with contumely and threatened at every step, they arrive at length at their place of destination, is it natural to suppose that they can feel much amity for the power whose agents have done them these wrongs? No, sir; and one of the evils inseparable from this state of things is, that the hostility thus engendered is not confined to their own breasts, but is transferred, to some extent, to individuals of other bands, with whom they are brought in contact. Thus are concentrated upon our western hordes of savages, who are all more or less imbued with feelings of distrust and hatred towards the whites, which are only kept from manifesting themselves by a fear of the superior power of the Government. Sir, all the Indian wars you have had upon your hands, and are likely to occur hereafter, have been and will be occasioned by proceedings, such as I have but faintly described, on the part of your agents. The Black Hawk difficulty, so called, which cost you millions of dollars, was thus brought about. The Florida war took its origin in the treaty of Payne’s Landing, by which the Seminoles conceived themselves to have been defrauded and deeply wronged. This war has already cost you some thirty or forty millions, and from present indications, is likely to be renewed at another heavy expenditure on your part. And thus, sir, will this Government continue to be involved in troubles with the Indian tribes, until it ceases to pursue its present course with regard to them, and adopts a policy more in accordance with the principles of justice and humanity.

Mr. Chairman, I have gone into some detail of the operation of the present system upon the Indians, because it is necessary that it should be understood. A physician cannot be expected to prescribe successfully for his patient, without knowing the nature and extent of the disease. No more can Congress apply a remedy to existing evils, until they are properly probed and exposed. Sir, even the efforts of Christian missionaries to evangelize these Heathen, are more obstructed by the policy of the Government than by any other cause. The Indians who are thereby rendered restless and discontented, are little disposed to receive or profit by religious instruction. To use the words of a former eminent member of this House, “The Indian is called by the endearing name of brother, and he is told that we are religiously bound by the most sacred injunction to do unto other as we wish that others may do unto us; at the same time we exclude him from any participation in the benefit of our social and civil institutions. We treat the whole race as if they were not the descendants of Adam, and thus we baffle and tantalize the christian, who labors for their moral and religious instruction; and hence the deluded hopes of many wise and pious clergymen, whose efforts in their behalf, however unavailing, reflect upon them the highest honor. The Indians, at a loss to reconcile the friendly professions of the Christian, who labors for their moral and religious improvement, with the cruel treatment inflicted upon them by the Government, doubts the sincerity of the Christian, his jealousies and suspicions are excited, and the most bitter enmity to the whites rankles in his bosom.” Sir, this picture, mournful as it is, which was presented to this House twenty-seven years ago, by the distinguished chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs at that time, is a most correct delineation of the state of things existing at this distant period. One which would be more truthful and applicable to the present condition of affairs cannot be drawn. The thousands of dollars contributed by the Christian community in this land, for the melioration of the condition of the Indian race, and the faithful and unwearying labors of the missionaries of the Cross to evangelize them, will be alike unavailing, until the whole Indian system of the Government is changed. I bear cheerful testimony to the zeal and constancy with which these missionaries have labored in the Northwest, while I lament that they have not met with the success with which their exertions would have been crowned, if the policy of the Government had not interposed an insurmountable barrier.

It is a fact, Mr. Chairman, that under the operation of the present system, the Indian, when deprived of his lands, becomes entirely indifferent and apathetic as to his fate. With the mark of Cain upon his brow, regarded as a vagabond and treated as such, he actually loses a portion of his former vitality, and falls an unresisting prey to the slightest form of disease. It is an utter fallacy to suppose, that the diminution in the number of the Indians is attributable to the use of intoxicating drinks. True, this is an evil of great magnitude, which should be suppressed. But the real cause will be found in the policy which reduced the comparatively noble and independent savage to the condition of a vagrant and an outcast.

If you are sincerely desirous that he should strive against the process of demoralization, you must place before him some motive to stimulate his ambition, and some hope that by a course of moral and intellectual culture, he can attain to an equality with his white brethren. But to do this effectually, you must first win back his confidence, and convince him that the pleded faith of your Government, is considered as a solemn and a binding obligation, not to be dispensed with at pleasure.

Sir, I believe the first step to be taken for the improvement of the Indians, is to extend over them the protection of law. With this view, I had the honor at the beginning of this session, to introduce for the consideration of this body, a bill for the extension of the law of the United States, over the Indian tribes within the boundaries of Minnesota and Oregon. I included the latter at the special instance and request of my friend, the Delegate from that Territory, who fully concurs with me as to the propriety and necessity of such a measure. Sir, I can say in all sincerity, that unless this bill, or a corresponding one, is passed by Congress, all other plans for the civilization of the Indians will fail. It is the substratum upon which all else must rest. It has for its object, the security of life and property among the Indians themselves, to protect the industriously disposed against the system of communism by which they are now oppressed. I do not ground my convictions of the beneficial operations of this measure upon my own individual opinion only, but upon those of the officers of the Government, of the missionaries, and of many prominent citizens of our Territory, who have all had much opportunity of acquiring information connected with the condition of the Indians. They have petitioned you to pass such a bill. The objection, which has with some plausibility been urged against it, that it would bear with too much severity upon a barbarous people, unaccustomed to their discipline of law, has in reality no foundations, for its very intent and operation would be to arrest the cruelties and outrages which are now practiced among them, upon persons and property. Another difficulty may perhaps be suggested, that these tribes are independent, and that consequently no right exists on the part of this Government, to subject them to its laws. But, sir, this state of independence is only nominal. The Indians hold their lands by a usufructuary right, or right of occupation, the fee simply being in the United States. For this reason, the Government has never hesitated to make such rules and regulations within the limits of the Indian country, operating equally upon whites and Indians, as it has deemed expedient. And, sir, your functionaries have ever taken upon themselves to inflict punishment at will upon one tribe for committing aggressions upon another tribe. Stripes, confinement at hard labor, and the degradation and imprisonment of the chiefs and principal men, for petty offences, have been resorted to, whenever the occasion prompted a recourse to such inflictions. Nay, sir, your Department of Indian Affairs has heretofore arrogated to itself the right to stop the payment of annuities to the tribes, under solemn treaty stipulations, when one tribe has been guilty of aggressions upon another band. This was done on occasion within a few years, when, because three or four individuals of the tribe, entitled to provisions in accordance with treaty stipulations, joined a war party, and were present at the murder of some persons of a different tribe, the department ordered the stoppage of the annuities of the bands to which the offenders belonged, and thereby occasioned the death of more than one hundred and fifty innocent individuals by starvation, or diseases engendered by improper food.

In the face of such facts as these, sir, where is there any propriety in opposing the objection to the passage of the bill referred to, on the score of the independence of these tribes? The plea is a mere mockery, and one object of the bill is to place these poor creatures under the benight rule of our own laws, and thereby put a stop forever to all the arbitrary and illegal proceedings to which I have called your attention. If the Indians must be punished, let the inflictions at least be regulated by law. Sir, the very measure I am advocating, and which anticipates the division of property among the individual Indians, has been often recommended by eminent and experienced men holding high stations under this Government. In 1789 General Knox, then Secretary of War, thus expressed himself in a report to the President: “But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America. This opinion is probably more convenient than just. To deny that under a course of favorable circumstances it could be accomplished, is to suppose the human character under the influence of such stubborn habits, as to be incapable of melioration or change, a supposition entirely contradiction by the progress of society, from its barbarous ages to its present degree of perfection. Were it possible to introduce among the Indian tribes a love for exclusive property, it would be a happy commencement of the business.”

Mr. Calhoun took the same view of the subject in his report in 1822: “To tribes thus surrounded, nothing can be conceived more opposed to their happiness and civilization, than this state of nominal independence, while it has nearly all the disadvantages of a state of absolute subjugation. The consequence is inevitable. They lost the lofty spirit and heroic courage of the savage state, without acquiring the virtues which belong to the civilized. Depressed in spirit, and debauched in morals, they dwindle away a wretched existence, a nuisance to the surrounding country. Unless some system can be devised, gradually to change these relations, and with the progress of education to extend over them our laws and authority, it is feared that all efforts to civilize them, whatever flattering appearances they may for a while exhibit, must ultimately fail.”

Sir, I might continue quotations to any extent, in support of the principle that there can be no hope of improvement for the Indian, until he is brought within the pale of law. But those I have recited, together with the fact that the failure of Congress to adopt them, has produced the disastrous results that were predicted, should be a sufficient guarantee to this House, and to the country, that no evil, but much good, would follow the passage of this proposed bill. The gentleman, recently at the head of the Indian Bureau, has recommended such a measure in his late report. His view of its necessity, is based upon the reasons which have been used by the several superintendents and agents of the department. It is indeed pregnant with blessings to the poor savage. Under its operations, the murders, the massacres, and the destruction of property will cease. The wars between hostile bands will be suppressed. A new era will have commenced in the history of the red man, and the corner-stone of his civilization will have been laid Hand in hand with this measure, should be a provision that each individual of whatever tribe, who will cultivate the soil for three consecutive years, shall be entitled to a grant of a certain number of acres of land, without the power, however, of alienating it. By thus doing, you will stimulate those who are industrious to exertion. With an experienced gentleman from whom I have already quoted, I believe that “the history of all nations, Christian or Heathen, will confirm the fact, that none of the sons and daughters of men ever did become extensively civilized, virtuous and happy, except they were stimulated to industry and enterprise, by giving them an idea of the fruits of his own labor, industry and enterprise, with the power of transmitting them to those who are most near and dear to him.” And who can urge a stronger claim upon you in favor of such a grant than the poor savage, the descendant of that noble race who have given you an empire such as the world as ever seen? While you are agitating the question in this Hall of the propriety of giving to every white settler a large portion of the public lands, “without money and without price,” no voice has been heard in favor of that portion of God’s creation, from whom you have received these lands, for a consideration too insignificant to be taken into account. Has anyone suggested that common justice would teach us to provide a home for the Indians, and that peradventure he might be reclaimed from his savage state? No, sir; he belongs to a doomed race, and it is not deemed worth the pains to endeavor to avert his impending fate. As if God, in his mercy had over placed upon this earth, a race created in his own image, fore-ordained only to suffer and to die!

Sir, give to the wandering savage a home secured to him by law, and you will have done much to redeem him. You thereby begin the process of denationalization, and the end will be his incorporation into the American family. Meanwhile bestow upon him civil privileges, withholding political rights, until he is sufficiently advanced to appreciate their enjoyment. Establish manual labor schools for the education of his children in the useful arts, and in the English language, and afford him at the same time, the blessings of religious instruction. Insist that all the children as they arrive at a suitable age, shall attend these schools, and let them be kept as much as possible from the demoralizing influences with which they are now surrounded. The annuities of the different bands will, of course, continue to be divided as they now are, per capita, and each individual who is the head of a family, will thus receive the means to aid him in his endeavors to meliorate his condition. Adopt these incipient measures, and thus prepare the way for the reception of the Indian as an equal into your community. You will thereby relieve him from the incubus which now threatens the speedy extinction of this unhappy people. It will then be no longer the case as it is now, that your first intercourse with the savage, the first apparently friendly grasp of the hand which you tender him, will infuse a selwo but foul and mortal poison in his veins, to blight his hopes, destroy his energies, and send him an unresisting victim to the grave.

Sir, in this work you will have the cooperation of every man on the frontier, except, perhaps, of a few miserable wretches, who risk their souls’ salvation by the sale of intoxicating liquors to the Indians. These few are rapidly diminishing, scathed as they are by the burning indignation of a sound public sentiment. For the rest, I know of no others among us so utterly depraved, as not to bid “God speed” to measures which have a direct tendency to elevate the poor savage. Sir, there is nothing to prevent the civilization of the Indian race. They are gifted with a high order of intellect, and an aptitude for acquiring knowledge fully equal to that possessed by the whites; and this nation will be held responsible before God and man, if it longer neglects to provide for the preservation of the remaining tribes.

But, Mr. Chairman, I remark in conclusion, that if anything is to be done it must be done now. The busy hum of civilized communities is already heard far beyond the mighty Mississippi. You are about to remove the Oregon Indians to the east of the Cascade Mountains. The settlements in New Mexico and Utah, are driving the tribes that roam the prairies in that quarter, towards the East and the North. Your pioneers are encircling the last home of the red man, as with a wall of fire. Their encroachments are perceptible, in the restlessness and belligerent demonstrations of the powerful bands who inhabit your remote western plains. You must approach these with terms of conciliation and of real friendship, or you must very soon suffer the consequences of a bloody and remorseless Indian war. Sir, what is to become of the fifty or sixty thousand savage warriors and their families, who line your frontier, when the buffalo and other game upon which they now depend for subsistence are exhausted? Think you they will lie down and die without a struggle? No, sir, no. The time is not far distant, when pent in on all sides, and suffering from want, a Philip or a Tecumseh will arise to band them together for a last and desperate onset upon their white foes. What then will avail the handful of soldiers stationed to guard the frontier. Sir, they, and your extreme western settlements, will be swept away as with the besom of destruction. We know that the struggle, in such case, would be unavailing on the part of the Indians and must necessarily end in their extermination. But this nation will subject itself to additional and awful retributions of that Prividence without whose knowledge and permission “not even a sparrow falls to the ground,” if it fails to use every endeavor to avert such a catastrophe. This Republic is even now expiating its guilt in this respect to some extent, by the visitations of pestilence, and the weakening of that bond of harmony among its members which was wont to exist. While manifesting an active sympathy for the nations of the Old World, who are down trodden by despotic power—while like the Pharisee of old, we are thanking God that we are not as other men are, we seem to forge that we are still pursuing a line of policy towards the Indian race, which has already destroyed countless thousands of them. Sir, this nation of more than twenty millions of people, can well afford to reach forth its friendly hand to rescue the residue of this unhappy people, from degradation and death. You are taking from them their lands, their homes, their all, and whatever return can be made them in this hour of their greatest need, should be granted with an ungrudging and generous hand.

Well might the eloquent Sevier, whose voice is now silenced in death, thus appeal to the Senate in behalf of the Indian tribes in 1839. Said he, “Let us remember the kind and hospitable reception of our ancestors by the natives of the country, a reception which has been perpetuated in carved figures in the walls of the Rotunda of this Capitol; and in remembering these things, let us this day step forward and do something for our wretched dependents, worthy of a great, a merciful, and generous Christian people.”

April 1, 2020

Minnesota’s Red River Trails

March 19, 2020

Free Audio Sample: Resisting Removal, Chapter 4

Enjoy this free audio sample from Chapter 4 of the novel “Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850.” Get the full print or ebook version at Amazon, IndieBound, Barnes and Noble, direct from the author, or wherever books are sold.

March 16, 2020

Learn from home – An Online Course about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862

Dakota Prisoners at the Lower Sioux Agency, Photo by Adrian J. Ebell, Sourced from the MNHS Collections

Dakota Prisoners at the Lower Sioux Agency, Photo by Adrian J. Ebell, Sourced from the MNHS CollectionsIn August of 1862, Minnesota was shook by war. After years of oppression and genocidal policies, a faction of Dakota soldiers retaliated by attacking, killing, and taking captive several hundred noncombatant U.S. citizens living throughout south and southwestern Minnesota. The attacks, which have become known as the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, lasted more than a month before being put down by U.S. forces led by Henry Hastings Sibley. In the aftermath, thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in what remains the largest mass execution in United States history. Shortly thereafter, all Dakota and Ho-chunk peoples were exiled from beyond the borders of the state of Minnesota by act of Congress.

Preview the Course Now!

The U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 was much more than a series of battles. It involved years of cultural and social change and included the contribution and perspectives of many different groups of people. In order to understand the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, it is important to carefully consider all the elements that eventually led to unavoidable conflict.

With this online course, students will come away with three valuable results.

Students will be able to critically evaluate the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862: when, why, and how it happened.Students will be able to identify the people and events that were relevant to the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.Students will be able to place the U.S. – Dakota War within its historical context with an understanding of the various influences and perspectives involved.

This easy-to-follow course includes seven lessons. Each lesson contains the following:

3 Specific Learning TargetsA 3-6 Minute Video Lecture with Relevant ImagesA Printable List of Key Terms and ConceptsBiographies of Key People Provided Through Lecture and a Printable ResourcePrintable Discussion Questions and Practice Activity Related to the Current LessonA Six Question Multiple-Choice Quiz

Click the video below to watch a course preview.

Find the course at Udemy.com where you can learn more and preview various lectures: https://www.udemy.com/course/the-us-dakota-war-of-1862/

Enroll Now!

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian whose work focuses on the complicated and tumultuous time period when land was exchanged between Native and American hands. Using elements of fiction and nonfiction, Mustful’s work relies on real historical figures and documentation while creating compelling narratives that bring history to life. You can learn more about the author and his work at his website, www.colinmustful.com.

February 28, 2020

Old Rail Fence Corners: Frontier Tales Told by Minnesota Pioneers

Lucy Leavenworth Wilder Morris

Lucy Leavenworth Wilder MorrisIn 1911, Lucy Leavenworth Wilder Morris conceived the idea for a book to record the recollections of early Minnesota settler-colonialists. With the help of twenty-two fellow members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Lucy recorded, transcribed, and edited the “simple anecdotes” of 154 women and men who came to Minnesota during its earliest years. The result was a book titled, Old Rail Fence Corners: The A.B.C.’s of Minnesota History. It was published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1914, reprinted in 1915, and published as a new edition in 1976. It is a remarkable, earnest, and interesting look at what life was like for Minnesota’s early pioneers—men, women, and children who made tremendous sacrifices and lived through hardship in hopes of building a better life.

Before sharing some of the anecdotes I found most interesting, funny, or surprising, it is important to remember the context of the place and time period for which these stories take place. In 1850, shortly after Minnesota became a Territory of the United States, the non-Native population was 6,077. A decade later, the non-Native population reached 172,023. That growth was spurred by economic incentives and ornamented descriptions of the region’s beauty and potential for wealth. One such description, written in poetic form by an 1852 journalist, said: “There are its interlinking lakes, its forests wild and wide, And streams—the sinews of its strength—that feed it as they guide; Its rich primeval pastures grounds, fenc’d by the stooping sky, And mines of treasure, yet undelved, that ‘neath its surface lie.”

Migration to Minnesota was also effectuated by numerous land cession treaties between sovereign Indigenous peoples and the United States government. The most notable during this time period were the 1851 treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota that opened up land west of the Mississippi river for settlement while requiring the Dakota people to move their homes onto a reservation along the Minnesota river valley. Such treaties were often lopsided arrangements satisfying the political and economic motivations of its American negotiators while exploiting Native populations. It is likely that many settler-colonialists were unaware of the financial and political arrangements that made land available to them, but not all were ignorant of their encroachment on Native territory and rights.

According to historian Gary Clayton Anderson, numerous emigrants claimed land based on the concept of “settler sovereignty” which allowed people to claim land before it was surveyed. In the spirit of settler sovereignty, many emigrants took claims on land west of the Mississippi river illegally, before the treaties were ratified by Congress. In response to the illegal settlement practices, Minnesota U.S. Representative Henry Sibley wrote to Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey, “Let the people go onto the purchased country in thousands if they will. Never in any case, will the land revert to the possession of the Indian.” Once a revised treaty was ratified by Congress, Little Crow, chief spokesman for the Mdewakanton Dakota, criticized the U.S. government for its greed and noted, “we have neither our lands, where our fathers’ bones are bleaching, nor have we anything.”

With this context in mind, I do believe it is important to celebrate the industriousness and hard-labor of Minnesota settlers who experienced lives of privation and sacrifice with only the hope of a prosperous future. Many of them were kind, community-driven people whose stories have value and whose lives contributed to the diverse, ever-changing, and bountiful state we know today.

Mrs. Anna Simmons Apgar – 1854

When our six families got to the springs near Excelsior it was near dark and we struck the worst road we had found in the swampy land by it. The mosquitoes were dreadful, too. How dreadful, no one today can ever believe. One of the tired out men said, “This is Hell!” “No,” said another, “Not Hell, but Purgatory.” The spring took its name from that.

Has anyone ever told you how terrible the mosquitoes were in the early days? Think of the worst experience you ever had with them and then add a million for each one and you will have some idea. My little face, neck, arms, legs and feet were so bitten, scratched and sunburned that when I was undressed I was the most checkered looking young one you ever saw.” P. 97-98

Settler-Colonialists’ family homestead, circa 1880. MNHS Collections

Settler-Colonialists’ family homestead, circa 1880. MNHS CollectionsMrs. J.R. Beatty – 1853

The want of salt bothered the pioneers more than anything else. Game abounded. Buffalo herds sometimes came near and deer often came through the settlement on the way to the river to drink. The streams were full of fish, but we could not enjoy any of these things without salt. However, our family did not suffer as much inconvenience as some others did. One family we knew had nothing to eat but potatoes and maple syrup. They poured the syrup over the potatoes and managed to get through the winter. Sometimes flour would be as high as $24 a barrel. During the summer when the water was low and in the winter when the river was frozen and the boats could not come down from St. Paul, the storekeepers could charge any price they could get. P. 166

Mr. I.A. Pelton – 1858

At this time too, they had to watch their fields with guns, or protect them with scarecrows and have the children watch them to keep them clear from the blackbirds, which were an awful pest. There were millions of these birds and there was not a time of day when they were not hovering over the fields. These birds would alight in the corn fields, tear the husks from the corn and absolutely ruin the ears of corn; also feed on the oats and wheat when it was not quite ripe and in a milky condition. P. 171

Sod House, Circa 1880. MNHS Collections.

Sod House, Circa 1880. MNHS Collections. Miss Sara Faribault

Little Crow was often at our house and was much loved by us children. He used to bring us candy and maple sugar. My father was fond of him too, and said he was always honest. P. 233

Mr. Michael Teeter – 1857

Fortunately there was plenty of fine wood, but the cracks were so numerous and large in our houses that we veritably warmed the outdoors in keeping ourselves warm. We chopped and sawed wood every spare moment in winter and summer in order to keep the booming fires which were necessary all winter long. We used to talk and think much of the settlers who were on the prairie who were so unsheltered and far from standing timber. P. 194

Mrs. W.L. Niemann

The winters there were very long and severely cold and many times they would be shut in by the depth of the snow for weeks at a time. One time in particular the snow was so deep and the cold so intense that they had been snowbound so long that their supplies were almost exhausted, and my grandfather sent the men off to get a fresh supply. They were gone much longer than usual and the little family began to suffer for want of food and were obliged to go out and scrape away the snow to find acorns. They also ate the bark of trees. P. 196

Jensen Homestead, Otter Tail County, Circa 1880. MNHS Collections

Jensen Homestead, Otter Tail County, Circa 1880. MNHS CollectionsChristmas in those hard times did not mean to us little pioneer children what it does now. There was no spare money with which to buy presents. We always hung up our stockings, but got nothing in them but a little cheap candy, and perhaps a few raisins. But one year, father determined to give us and the other children of the village a little better Christmas than usual. So he went out to his woods and cut enough firewood to exchange in St. Cloud for a barrel of apples. Then he divided off one end of our sitting room with a sheet and arranged a puppet show behind it. And with the village children in one end of the room eating apples, and father in the other managing the puppets, we celebrated the day in a very happy way. P. 198-199

Colonel A.P. Connolly – 1857

We also built a boat here, or rather made a dugout, so we could explore the river. We had amusements in plenty, for wolves, Indians, mosquitoes and grasshoppers were in great abundance. The wolves were hungry and told us so, congregating in great numbers for their nightly concerts. We had to barricade our doors to keep them out and burn smudges on the inside to keep mosquitoes out as well. P. 213

Read Old Rail Fence Corners Online.

Sources:

Lucy Leavenworth Wilder Morris, ed., Old Rail Fence Corners: Frontier Tales Told By Minnesota Pioneers, introduction by Marjorie Kreidberg, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1976).

Gary Clayton Anderson, Massacre in Minnesota: The Dakota War of 1862, the Most Violent Ethnic Conflict in American History, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019).

“Sketches on the Upper Mississippi,” in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 7, No. 38, (July, 1853), pp. 177–190.

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.