Colin Mustful's Blog, page 18

November 13, 2018

Resisting Removal: Ojibwe Clan System

The Ojibwe people are descended from an earlier people known as the Lenni Lenape. Many tribes, such as the Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Cree, Shawnee, and Miami, trace their ancestry to the Lenni Lenape. But among all the related tribes which have become divided by geography, language, and customs, the first and principal division is that of clan or doodem.

The division of clan among the Ojibwe and other related tribes is more important than the division of tribe. Clan is a division based on blood and kindred that is descended in the male line. Each clan is represented by a badge or symbol taken from nature. There are seven principal clans and within each clan there are several sub-clans. The seven principal clans include the Crane, Loon, Bear, Deer, Bird, Marten, and Fish clans.

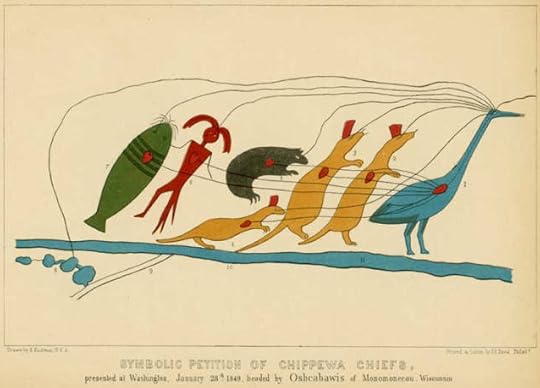

This is a re-creation by Seth Eastman of a petition brought to Washington in 1849 by Oshcabawis. It depicts the Ojibwe clan system. Image from Wikimedia Commons – By Bizhiki and other Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs – Wisconsin Historical Society Library, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index....

This is a re-creation by Seth Eastman of a petition brought to Washington in 1849 by Oshcabawis. It depicts the Ojibwe clan system. Image from Wikimedia Commons – By Bizhiki and other Lake Superior Ojibwe chiefs – Wisconsin Historical Society Library, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index....Each clan plays a unique role within Ojibwe society and governance. For instance, the Crane Clan are said to be excellent orators who represent the Ojibwe while negotiating with people outside of the community. The Loon Clan claims to be the chief or royal family because of the collar around a loon’s neck which resembles the royal megis, or wampum, about the neck of a chief. The Loon Clan are responsible for settling disputes and issues within their home community. Ultimately, each clan has a role that is used for the greater good of the community.

In addition to being known by several different clans, the Ojibwe are also known by several different names. This includes being called Chippewa and Anishinabe. Each name, Ojibwe, Chippewa, and Anishinabe, are distinct from another, but their origin and usage is not agreed upon.

The term Chippewa is generally regarded as a mispronunciation of the word Ojibwe. Chippewa was the name recognized by the U.S. government and used in all dealings with the Ojibwe people. Ojibwe literally means “puckered up” and is thought to describe the Ojibwe based on their moccasins, which were sewn in such a way to pucker up and keep the snow out. However, there are several different spellings and interpretations of Ojibwe. Anishinaabe has been translated as “original” or “spontaneous people.” It is most often used when describing themselves and refers to their creation as the first people.

Read History of the Ojibway Nation by William Warren.

Sources:

Mike Swan, “Who We Are as Anishinabe,” Accessed June 6, 2018, http://anishinaabemodaa.com/data/upfiles/media/Who%20Are%20We%20-%20Seven%20Prophets.pdf

Georgian College Aboriginal Resource Centers, “The Ojibwe Clan System,” Anishnaabeg Bimaadiziwin: An Ojibwe Peoples Resource, Accessed June 6, 2018, http://ojibweresources.weebly.com/the-clan-system.html

William Warren, “History of the Ojibway Nation,” in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 5, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885).

Louise Erdrich, Books and Island in Ojibwe Country: Traveling in the Land of My Ancestors, (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2003).

Thomas Peacock and Marlene Wisuri, Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions, (Afton, MN: Afton Historical Society Press, 2002).

November 6, 2018

Resisting Removal: The Annuity Payment of January 1852

In January 1852, a special annuity payment was scheduled to take place at Fond du Lac, an Indian agency near present day Duluth, for those Ojibwe who had not received payment the previous fall. The payment was ordered by Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey after a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe had visited him in St. Paul. By this time, the La Pointe Ojibwe had not received annuities in 1850 or 1851 and were quite dissatisfied with the conduct of their agent, John Watrous.

According to one petition given to Ramsey and dated November 6, 1851, the Ojibwe believed that Watrous, who was a former La Pointe trader, had a close relationship with the traders. They asserted that annuity goods and money were deposited in the trader’s stores and that the traders controlled the agent’s conduct.

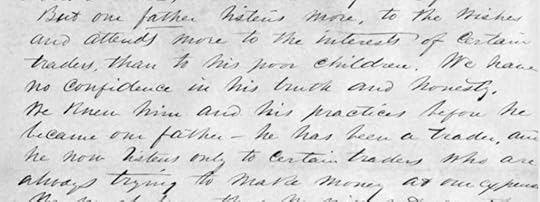

In this petition dated November 6, 1851, Ojibwe chiefs and headmen stated that, “But our father (John Watrous) listens more to the wishes and attends more to certain traders, than to his poor children. We have no confidence in his truth and honesty. We knew him and his practices before he became our Father. He has been a trader and we know only listens to certain traders who are always trying to make money at our expense.” Petition held by the Wisconsin Historical Society.

In this petition dated November 6, 1851, Ojibwe chiefs and headmen stated that, “But our father (John Watrous) listens more to the wishes and attends more to certain traders, than to his poor children. We have no confidence in his truth and honesty. We knew him and his practices before he became our Father. He has been a trader and we know only listens to certain traders who are always trying to make money at our expense.” Petition held by the Wisconsin Historical Society.The Ojibwe gathered for payment at Fond du Lac in early January 1852. However, just as the Ojibwe asserted, the payment was ruled by the traders. As described by Vincent Roy who attended the January payment, the traders George Nettleton and Clement Beaulieu were given privileged positions and “got most of the money.” He went on to say that, “One stood at one door and one at the other of the payroom and no Indian was allowed to go out until he had paid most of his money to one or the other of them. The chiefs and headmen were bribed to consent to it” (White, The Removal Context, 234).

The agency blacksmith, William E. Van Tassell gave a similar description of the payment. He reported that “at the door of exit just outside the door C.H. Beaulieu was located with a table and papers and some silver change. As the Indians passed out of the door they were stopped by Beaulieu and his assistants and compelled to settle their accounts. Beaulieu took the money. I frequently heard him say on taking the money—Now we are square, the account is all settled” (White, The Removal Context, 234).

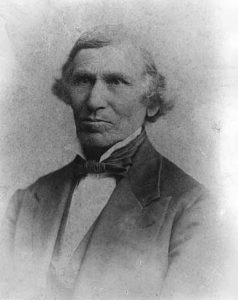

Clement Beaulieu was one of the traders at the 1852 payment at Fond du Lac. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

Clement Beaulieu was one of the traders at the 1852 payment at Fond du Lac. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.In some cases, the Ojibwe received no money at all. This occurred when the traders presented power of attorney for a member of one of the bands which allowed the trader or his clerk to collect the annuity money before it was ever received by the Ojibwe. According to Van Tassell, “from what I saw I think the traders received the greater portion of the money paid the first day . . . The Indians carried away but very little” (White, The Removal Context, 235).

A few months later, after it became obvious that they could get no support from Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey, a delegation of La Pointe Ojibwe traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet with the President with the hopes of ending such mistreatment.

Read the full text of the November 6, 1851 petition.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

October 30, 2018

Resisting Removal: Leonard and Harriet Wheeler

In the summer of 1841, Leonard and Harriet Wheeler arrived at La Pointe to work as missionaries as members of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. For twenty-five years they lived among the Lake Superior Ojibwe before retiring from missionary life and moving to Beloit in 1866. Leonard has been called “the best friend the Ojibwe ever had” (White Boy Grew Up Among Chippewas). However, he and Harriet also facilitated cultural assimilation policies that devalued and damaged traditional Ojibwe ways of life.

Leonard Wheeler was born in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts on April 13, 1811, and he grew up in Vermont. After attending Middlebury College and teaching for a few years, he entered the theological seminary in Andover, Massachusetts. Harriet Wood was born December 4, 1816, in Dracut, Massachusetts and as a young woman attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. Leonard and Harriet married on April 26, 1841, and shortly thereafter departed for La Pointe as missionaries to the Lake Superior Ojibwe.

Missionary Leonard Wheeler. Image from “In Unnamed Wisconsin” by John Nelson Davidson.

Missionary Leonard Wheeler. Image from “In Unnamed Wisconsin” by John Nelson Davidson.In their first four years, Leonard and Harriet dedicated themselves to learning the Ojibwe language, preaching and teaching, and caring for the welfare of the people at La Pointe. Together, they discovered the work was hard, yet rewarding, leading Harriet to remark in her journal, “I found it was sober, prose business; a stern reality, but yet a most precious, a most blessed work.”

For better or worse, the Wheelers believed that western ways of civilization and Christianity went hand-in-hand. “They are inseparable,” Harriet noted in her journal. In order to greater influence the Ojibwe, the Wheelers established a mission and community at Bad River called Odanah in 1845. Leonard believed that while living at La Pointe, the Ojibwe suffered from the influences of traders and whiskey sellers, and that their traditional nomadic way of living made it difficult to teach them the white, Christian ways of living. At Odanah, he hoped the Ojibwe would adopt agriculture and remain in one place long enough to stay under his continual influence.

Harriet Wood Wheeler in 1890. Photo from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Harriet Wood Wheeler in 1890. Photo from the Wisconsin Historical Society.Despite their negative perception of the Ojibwe culture and ways of life, the Wheelers worked hard as members of the community. Leonard filled many roles as a doctor, farmer, carpenter, teacher, interpreter, and intermediary between the Ojibwe and U.S. government officials. On Sundays, he held numerous services in both the English and Ojibwe languages. Harriet raised nine children, while maintaining large and beautiful gardens and teaching Ojibwe women and girls to read and sing. Also, Leonard spoke up for Ojibwe land rights during and following the Sandy Lake Tragedy in 1850. According to historian Leo Filipczak, “Wheeler is someone who more than once stood up for justice and against corruption even when it brought him powerful enemies and endangered his health and safety” (Filipczak, Leonard Wheeler Obituary).

Leonard Wheeler became ill and retired to Beloit, Wisconsin in 1866. He died there in 1872. Harriet Wood Wheeler’s journal and letters were edited and published by Nancy Bunge and is titled, Woman in the Wilderness. She died in 1892.

Read from the annual report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.

Sources:

Nancy Bunge, Woman in the Wilderness: Letters of Harriet Wood Wheeler, Missionary Wife, 1832–1892, (East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 2010).

Sara Breitenfeldt, “Leonard Wheeler and the Bad River Band,” http://www.academia.edu/254416/Leonar....

Leo Filipczak, “Leonard Wheeler Obituary,” Chequamegon History (blog), Published May 31, 2014, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

“White Boy Grew Up Among the Chippewas,” Wisconsin Historical Society, Wisconsin Local History & Biography Articles, Milwaukee Journal, January 25, 1931, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Reco....

October 23, 2018

Resisting Removal: The Suspension of Removal Efforts

On August 25, 1851, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea sent a telegram to La Pointe, Wisconsin, instructing the Indian agent there, John Watrous, to “suspend action with reference to the removal of Lake Superior Chippewas for further orders” (White, The Removal Context, 210). The telegram was received by missionary William Boutwell and then delivered by messenger to John Watrous at Sandy Lake on or around September 11. Watrous, however, ignored the order, making no mention of it to his superiors or the Ojibwe.

When the Lake Superior Ojibwe arrived at Fond du Lac that fall, Watrous refused to make their annuity payment. Watrous set off to Sandy Lake to make payment to the Mississippi and Pillager Ojibwe, promising to return to Fond du Lac later. But this was a part of Watrous’ plan to delay payment and force the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe after orders had been received to suspend removal. In a letter to Superintendent of Indian Affairs Alexander Ramsey and dated October 25, Watrous stated that payment would be “so late in the fall that little fear may be entertained of their being able to return to their old home” (White, The Removal Context, 216). This was the same plan that resulted in the death of four hundred Ojibwe at Sandy Lake the previous year.

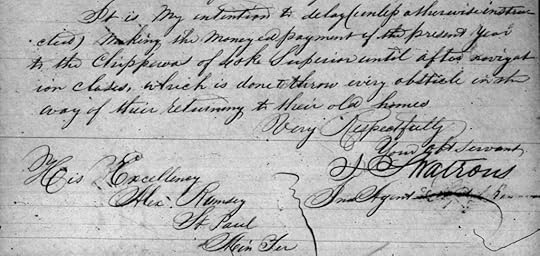

In this letter by John Watrous to Alexander Ramsey, Sept. 22, 1851, Watrous states, “It is my intention to delay (unless otherwise instructed) making the moneyed payment of the present year to the Chippewas of Lake Superior until after navigation closes, which is done to throw every obstacle in the way of their returning to their old homes.” Letter found in the MNHS Manuscript Collections.

In this letter by John Watrous to Alexander Ramsey, Sept. 22, 1851, Watrous states, “It is my intention to delay (unless otherwise instructed) making the moneyed payment of the present year to the Chippewas of Lake Superior until after navigation closes, which is done to throw every obstacle in the way of their returning to their old homes.” Letter found in the MNHS Manuscript Collections.In addition to continuing his plan, Watrous also argued that removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe had already been accomplished and therefore there was no action to suspend. In his annual report written September 20, 1851, Watrous stated that, “it affords me much satisfaction to inform Your Excellency that the entire removal has been accomplished” (White, The Removal Context, 213). Watrous went on to report that 3,000 Ojibwe had been removed in 1851 when in reality only a few hundred had removed.

Missionary Leonard Wheeler helped the La Pointe Ojibwe fight against the removal efforts of Indian Agent John Watrous. Image from “In Unnamed Wisconsin” by John Nelson Davidson.

Missionary Leonard Wheeler helped the La Pointe Ojibwe fight against the removal efforts of Indian Agent John Watrous. Image from “In Unnamed Wisconsin” by John Nelson Davidson.A few months later, when the Ojibwe gathered for their rescheduled payment, Watrous presented them with a document which was an agreement for them to remove from their homes next spring. The Ojibwe protested and the missionary Leonard Wheeler asked Watrous about the order to suspend removal that had been delivered in September. According to Wheeler, “I asked him also what authority he had to ask the Indians to remove, when the removal had been suspended? He denied the fact . . . but said he had received an order to suspend active operations” (White, The Removal Context, 232). Wheeler also reminded the agent of the many promises he made that had not been delivered—promises to provide health, comfort, and well being for the Ojibwe and their families. According to Wheeler, the agent admitted to him that “he intended to do just as little for the Indians there as possible, his object being to get them beyond the Mississippi as soon as he could” (White, The Removal Context, 232).

It is clear then, that despite the tragedy at Sandy Lake and despite orders to suspend removal, Indian agent John Watrous continued efforts to remove, against their will, the Lake Superior Ojibwe from their homes.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

October 16, 2018

Resisting Removal: Petitions Against Removal

In February 1850, Indian sub-agent John Livermore held a council with the La Pointe Ojibwe to inform them of the possibility of removal from their homes. According to Livermore’s account of the council, “they were indeed considerably excited, and said that the man who came here to make the treaty (in 1842), told them that they would not probably be required to remove for many years” (White, The Regional Context, 175). Despite promises such as these the Ojibwe were told that if they wished to receive their annual payment, which was normally given at La Pointe, they would instead have to travel to Sandy Lake, Minnesota.

Over the next few years, the Ojibwe faced continued pressure from government agents to move from their homes and into Minnesota Territory. But the Ojibwe resisted by filing numerous petitions against removal. Their efforts were supported by local white residents who also filed numerous petitions in favor of the Ojibwe’s right to remain living at La Pointe.

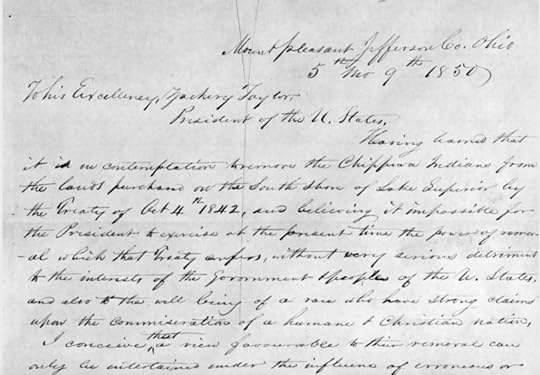

Petition of Cyrus Mendenhall May 9, 1850. From the Wisconsin Historical Society United States Bureau of Indian Affairs Documents.

Petition of Cyrus Mendenhall May 9, 1850. From the Wisconsin Historical Society United States Bureau of Indian Affairs Documents.One such petition was made by Cyrus Mendenhall, a mining entrepreneur associated with the Methodist Episcopal Mission Society and a “respected citizen” (Cleland, Preliminary Report, 65). Mendenhall rallied support from local ministers, physicians, officials, merchants, mine foreman, lumbermen, and other influential citizens. The petition stated that removal was “wholly uncalled for by any interest of the Government or people of the United States.” The petitioners ended by stating that, “We therefore…feel ourselves compelled solely by sentiments of humanity and justice, earnestly to remonstrate against a measure fraught with so many evil consequences as the proposed removal.”

This petition by the local white community was forwarded to President Millard Fillmore on July 30, 1850. It was then forwarded to the Secretary of the Interior who forwarded it to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea for a report. No action was taken as a result of the petition, and a report by Lea was not made until June the following year.

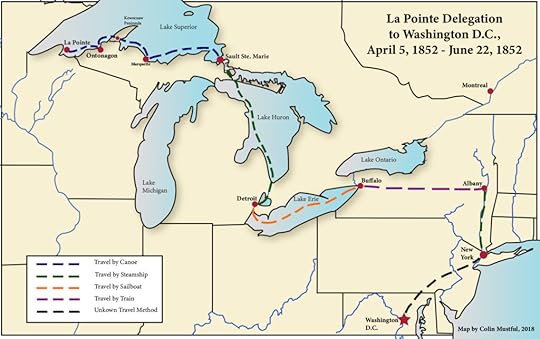

Journey of the La Pointe Delegation to Washington in 1852.

Journey of the La Pointe Delegation to Washington in 1852.Another petition among numerous others, was written by the La Pointe Ojibwe and carried with them as they traveled to Washington in 1852. As the delegation traveled by canoe across Lake Superior, they stopped at the mining and trading communities of Ontonagon, Portage Lake, Houghton, Hancock, and Sault Ste. Marie. There they obtained signatures for their petition from businessmen, traders, and miners who were sympathetic to their cause. Once they arrived in Washington, the petition was personally delivered to President Millard Fillmore who recognized several of the signatures. According to the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong, an interpreter who traveled with the delegation, after meeting the Ojibwe and seeing their petition, Fillmore agreed to countermand the removal order and reinstate annuity payments at La Pointe, which is exactly what the Ojibwe had worked so hard to achieve.

Read the petition of Cyrus Mendenhall and others.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

Charles E. Cleland, “Preliminary Report of the Ethnohistorical Basis of the Hunting, Fishing, and Gathering Rights of the Mille Lacs Chippewa,” Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 1–140.

Ronald N. Satz, “Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective,” in Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, “Transactions,” Vol. 79, No. 1, (1991).

“Turning Points in Wisconsin History,” Wisconsin Historical Society, United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/tp/id/62186.

October 9, 2018

Resisting Removal: Ojibwe Lifeways

For centuries the Ojibwe people survived through traditional seasonal practices of hunting, fishing, and gathering. Over time, they learned the best survival practices that they handed down from generation to generation. Through hard-work and respect for all plants, animals, and natural objects, they flourished throughout the vast northern regions. Eventually, their traditional lifeways were threatened by the encroachment of settlers and the assimilation policies of missionaries and the United States Government. But the Ojibwe maintained their survival traditions through challenging times and still practice many of their traditional lifeways today.

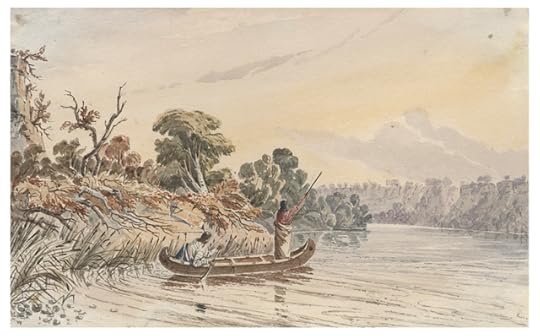

“Indians Spearing Fish 3 Miles Below Fort Snelling” by Seth Eastman. MNHS Collections

“Indians Spearing Fish 3 Miles Below Fort Snelling” by Seth Eastman. MNHS Collections

Spring Sugarbush: The spring was a time of joy and renewal for the Ojibwe. Families gathered in the sugarbush after being separated during the long, hard winter. The sugarbush was any large grove of maple trees where the Ojibwe could tap the trees to gather maple sap. This could only be done in the spring when the the sap would rise up the trunk during the warm days and then back down during the cold nights. Using birch bark baskets, the Ojibwe collected the sap which they boiled down into maple sugar and syrup. At the end of every spring, one family might pack out hundreds of pounds of sugar that could be stored and used throughout the year.

Summer Gathering: Summer was a time of plenty and so the Ojibwe worked hard to gather as much food as possible because it was so scarce at other times during the year. The Ojibwe often fished during the summer, using nets, spears, traps, and hook and line. They also harvested mushrooms and other forest plants such as cattail roots, wild onions, grapes, butternuts, hazelnuts, and all kinds of berries. They also trapped and hunted wild game such as beaver, mink, deer, bear, and moose. The Ojibwe made sure to use every part of the animal and always gave thanks for the food they captured and gathered with an offering of tobacco. What the Ojibwe did not eat during the summer they dried and stored for use later.

“Gathering Wild Rice” by Seth Eastman. From “American Aboriginal Portfolio” by Mary Eastman and held by the Newberry Library of Chicago.

“Gathering Wild Rice” by Seth Eastman. From “American Aboriginal Portfolio” by Mary Eastman and held by the Newberry Library of Chicago.Fall Ricing: Long ago, while the Ojibwe people were living near the Atlantic Ocean, they were told by their prophets to travel west “where the food grows on water.” After many years migration, they found that land. The food they discovered growing on water was wild rice. In the fall, the Ojibwe gathered and processed wild rice for use during the long winter. Wild rice grows in shallow water near the shores of lakes and bays. In order to gather the rice, the Ojibwe used a canoe that one person pushed slowly through the rice stalks, while another used knocking sticks to shake the rice off the stalks and into the canoe. Once ashore, the Ojibwe processed the rice by drying it, roasting it, and then separating the hull from the kernels. During times of abundance, most families could process hundreds of pounds of rice every fall.

Winter Trapping: Winter was a long, hard season in Ojibwe country. Families often spread out to make it easier to get food since it was so scarce. Winter was marked by the trapping of wild game that the Ojibwe used for food and for pelts that could be traded for necessary goods. The Ojibwe developed many techniques for hunting, trapping, and snaring wild game. A favorite among most Ojibwe was the snowshoe hare, a white rabbit that was seen as a right of passage for Ojibwe youth. Once a young person snared a snowshoe hare, they went from someone who only eats food to someone who provides it. The Ojibwe also fished through holes in the ice during winter and they survived on the food stored away during the spring, summer, and fall months.

Read Anton Treuer’s Ojibwe Lifeways.

Sources:

Anton Treuer, “Ojibwe Lifeways,” in Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, October-September 2012, http://files.dnr.state.mn.us/mcvmagazine/young_naturalists/young-naturalists-article/ojibwe/ojibwe.pdf

“The Four Seasons of the Ojibwe,” Minnesota Humanities Center, http://www.earthscope.org/assets/uploads/misc/Seven.The_Four_Seasons.pdf

October 6, 2018

Resisting Removal Cover Design

Author Colin Mustful is proud to share the cover design for his upcoming novel, Resisting Removal.

Summary: Resisting Removal is a historically detailed account of the 1850 removal efforts that resulted in the relatively unknown Sandy Lake Tragedy. Relying on real correspondence from the time period, the novel, through fictional scene and dialogue, exposes the corruption and negligence of the Indian System. It also brings to life important and sometimes controversial historical figures like Benjamin Armstrong, Chief Buffalo, and Leonard Wheeler. The story also expresses the rich culture and harrowing history of the Ojibwe people, exposing the wrong and deceit that the United States was founded on, and questioning whose story is really being told.

October 2, 2018

Resisting Removal: The Ojibwe in 1850

William Whipple Warren recorded the oral history of the Ojibwe which was later published as “The History of the Ojibway Nation.” Image from Wikimedia Commons.

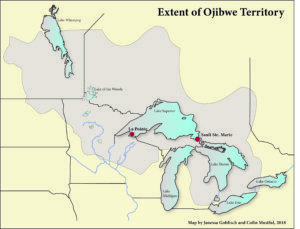

William Whipple Warren recorded the oral history of the Ojibwe which was later published as “The History of the Ojibway Nation.” Image from Wikimedia Commons.Around the year 1850, Ojibwe historian William Whipple Warren began recording the oral history of the Ojibwe people. His findings were published posthumously in 1885 under the title, History of the Ojibway Nation. In it, Warren describes the great migration when the Ojibwe moved from “the great salt water toward the rising sun,” to the island of Moningwunakauning, known today as Madeline Island or La Pointe. This migration began around the 900 CE and took several hundred years to complete. Once settled at La Pointe, the Ojibwe spread out in all directions. According to Warren, La Pointe was “the root from which all the far scattered villages of the tribe have sprung” (Warren, History of the Ojibway, 78, 80). That is why La Pointe has been called the ancient homeland of the Ojibwe people.

Warren described the Ojibwe territory in 1850:

“The Ojibways are scattered over, and occupy a large extent of country comprising all that portion of the State of Michigan lying north of Green Bay and west of the Straits of Michilimackinac, bordering on Lake Superior, the northern half of Wisconsin and the northeastern half of Minnesota Territory. Besides this they occupy the country lying from the Lake of the Woods, over the entire north coast of Lake Superior, to the falls of St. Mary’s and extending even east of this point into Upper Canada. They literally girdle the great “Father of Lakes,” and the largest body of fresh water in the world may emphatically be called their own, Kechegumme, or “Great Water”” (Warren, History of the Ojibway, 37).

Warren went on to describe their population at this time, estimating the total number of Ojibwe people at 15,000. Within the boundaries of the United States he estimated there were 9,000 Ojibwe people—1,000 living in Michigan, 3,000 in Wisconsin, and 5,000 in Minnesota Territory. While describing their geography, Warren wrote that the Ojibwe “reside almost exclusively in wooded country” and that entire territory is connected by waterway. Because of this, the Ojibwe traveled by birch bark canoe. They relied on birch bark for many purposes including the construction of their homes, called wigwams. Warren also briefly described the Ojibwe way of life, writing that “they procure food principally by fishing, also by gathering wild rice, hunting deer, and, in some bands, partially by agriculture” (Warren, History of the Ojibway, 38–40).

Warren went on to describe their population at this time, estimating the total number of Ojibwe people at 15,000. Within the boundaries of the United States he estimated there were 9,000 Ojibwe people—1,000 living in Michigan, 3,000 in Wisconsin, and 5,000 in Minnesota Territory. While describing their geography, Warren wrote that the Ojibwe “reside almost exclusively in wooded country” and that entire territory is connected by waterway. Because of this, the Ojibwe traveled by birch bark canoe. They relied on birch bark for many purposes including the construction of their homes, called wigwams. Warren also briefly described the Ojibwe way of life, writing that “they procure food principally by fishing, also by gathering wild rice, hunting deer, and, in some bands, partially by agriculture” (Warren, History of the Ojibway, 38–40).

Read William Warren’s “History of the Ojibway Nation.”

Sources:

Warren, William W. “History of the Ojibway Nation.” In Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 5. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society, 1885.

September 25, 2018

Resisting Removal: Alexander Ramsey and the Sandy Lake Tragedy

In 1849, Alexander Ramsey was appointed Governor of the new Minnesota Territory. At the time, the vast majority of the land was occupied by native Ojibwe and Dakota peoples and had a white population of less than 7,000 people. Ramsey, who was also the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, sought to acquire the land for the United States. Also, through the payment of Indian annuities, Ramsey sought to bolster the Minnesota economy for the benefit of traders, merchants, and businesses in the territory. Toward that goal, Ramsey sought the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe from lands in Wisconsin and into Minnesota where their annuity payment would benefit Minnesotans.

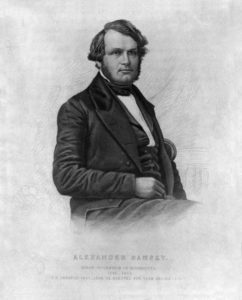

Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey played a large role in the attempted removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe which resulted in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey played a large role in the attempted removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe which resulted in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.Speaking to the Minnesota Legislative Assembly on September 4, 1849, Ramsey said that, “It might be well for the Legislative Assembly, to memorialize the President of the United States, requesting him to notify the Chippeways that these privileges (of hunting, fishing, and gathering in Wisconsin) must cease and requiring them to move into their proper territory” (White, The Removal Context, 162). This led to a Resolution of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Minnesota dated November 7, 1849, revoking the rights of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to remain living in Wisconsin and requiring their removal to Minnesota Territory. The Resolution was forwarded to Washington and read by President Zachary Taylor, who, on February 6, 1850, ordered the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe from their lands in Wisconsin, also known as the ceded territory.

As Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the region, it was Ramsey’s job to implement the Removal Order. However, it became apparent early on that removal would be attended with insurmountable difficulties if it was to be attempted in 1850. In a letter to Ramsey dated March 26, 1850, Indian Agent at La Pointe, John Livermore, addressed the difficulties attended with removal and warned of a great calamity if the Ojibwe gathered in Minnesota Territory without enough provisions. He also made it clear that the Ojibwe rejected removal and would not be removed because of promises made to them by the U.S. government during treaty negotiations in 1842. Then, on the same day as Livermore’s letter, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Orlando Brown informed Ramsey that Congressional appropriation of the funds necessary for removal would not available be until very late in the season. This had the potential to cause great problems because the Ojibwe traveled by canoe and if payment arrived too late, the waterways would freeze over and the Ojibwe would be unable to return to their homes.

Despite the warnings of a potential disaster, Ramsey pressed for the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe in the same year the Removal Order was given. Writing to Brown’s replacement Luke Lea on July 16, Ramsey stated his intention to make the Ojibwe annuity payment at Sandy Lake, Minnesota, “and there, time the payment in such a way as to interpose obstacles to a return to the country they left” (White, The Regional Context, 187).

Mikwendaagoziwag Memorial at Sandy Lake remembering the approximately 400 Ojibwe who died.

Mikwendaagoziwag Memorial at Sandy Lake remembering the approximately 400 Ojibwe who died.As directed by Ramsey, messengers were sent to the Lake Superior bands, telling them that if they wished to receive their promised annuity payment, they and their families must assemble at Sandy Lake, Minnesota, on October 25. But, just as previous warnings had suggested, payment was not appropriated from Congress and provisions at Sandy Lake were insufficient to provide for the needs of the approximately 4,000 Ojibwe that assembled there. Within a matter of weeks of their arrival at Sandy Lake, the Ojibwe began dying in large numbers from sickness and starvation. The agent did not arrive until late November and he did not disperse any goods until early December. By that time winter had set in and the Ojibwe encountered great difficulties returning home. The Sandy Lake Tragedy resulted in the death of approximately 400 Ojibwe.

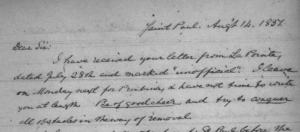

Letter from Alexander Ramsey to John Watrous, August 14, 1851; Found in the Manuscript Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Letter from Alexander Ramsey to John Watrous, August 14, 1851; Found in the Manuscript Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.After learning about the tragedy, Ramsey was undeterred in his removal efforts. Speaking to the Minnesota Legislative Assembly in January 1851, Ramsey reiterated his plans for removal and suggested they would begin again in the spring. A few weeks later, while meeting with the La Pointe Indian Agent John Watrous, the two men discussed their plans to continue the removal efforts beginning on May 1st when the Ojibwe sugar making would be over. In the following months, the Lake Superior put up a strong resistance to removal and were determined not to return to Sandy Lake. Nonetheless, Ramsey insisted that they be removed and that their payment be made in Minnesota Territory. Writing to Watrous on August 14, 1851, Ramsey encouraged Watrous against the resistance stating, “Be of good cheer, and try to conquer all obstacles in the way of removal” (White, The Regional Context, 225).

It was not until 1853, when Ramsey was removed from office, that removal efforts ceased and the Ojibwe were allowed to remain living upon their homelands.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

September 18, 2018

Resisting Removal: Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke)

Regarded as a hero among the Lake Superior Ojibwe, Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke) of La Pointe successfully resisted numerous attempts by U.S. government officials to remove his people from their ancient homeland. Recognized as the principal chief of the Lake Superior Ojibwe, Buffalo signed the treaties of 1825, 1826, 1837, 1842, 1847, and 1854. He also travelled to Washington DC in 1852 to fight for the rights of his people to remain living upon their homeland.

Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke), Image from the Wisconsin Historical Society

Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke), Image from the Wisconsin Historical SocietyBuffalo was born at La Pointe on Madeline Island around the year 1759, when it was still a part of New France. In his youth, Buffalo was known as a skilled hunter and athlete. Eventually, he became a leader among his people because of his speaking and oratorical skills which were highly valued in his culture. A member of the Loon Clan, Buffalo promoted peace between the Ojibwe and Dakota and he acted diplomatically in treaty negotiations.

After the Sandy Lake Tragedy in 1850 which resulted in the death of approximately four hundred Ojibwe because of removal efforts, Buffalo fought to end such efforts and obtain a permanent home for his people. Despite numerous petitions sent to Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey of Minnesota, removal efforts continued and his people went without annuity payments for several years. Buffalo, who was more than ninety years old at the time, determined that he must travel to Washington to see his “Great Grandfather” if removal efforts were to be terminated. In a memorial to the President, Buffalo outlined the grievances of his people and closed the impassioned plea by writing:

“It is generally the case with white men, when they have selected a spot to dwell at, that they begin to consider and look around them, to see what obstacles are in their way, they begin to cut away the underbrush and bad trees, in order to make the land level and smooth so that nothing will come in contact to hurt their feet, they see good trees and they are allowed to stand and live, and they are not cut down. We beseech you to do towards us as you do, allowing the good trees to stand and live in your domain. And furthermore we pray, that in accordance to that, we so fully understand that our annuities should be paid to us at Lapointe and that they may be continued there, until the expiration of the term as set forth in the Treaty of 1842″ (White, The Regional Context, 247).

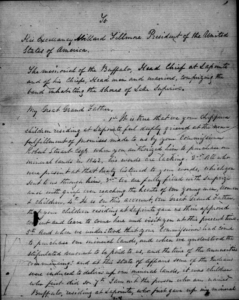

Memorial of Chief Buffalo to President Fillmore, June 12, 1852; Found in the Manuscript Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Memorial of Chief Buffalo to President Fillmore, June 12, 1852; Found in the Manuscript Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.According to the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong, a white interpreter who traveled with the delegation to Washington, Buffalo met with President Millard Fillmore who promised to end removal efforts and negotiate a new treaty that would provide permanent homes for the Lake Superior Ojibwe. A year later, the Ojibwe were paid their annuities at La Pointe and one year after that a new treaty was made that provided the Lake Superior Ojibwe reservations within their homelands. Buffalo died on September 7, 1855, at La Pointe. Today his legacy lives on among his ancestors who live at Red Cliff and Bad River, the permanent reservations he fought for.

Read more about Chief Buffalo’s 1852 trip to Washington.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

“Kechewaishke,” Wikipedia, Accessed May 30, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kechewa....