Colin Mustful's Blog, page 17

January 2, 2019

Resisting Removal: Watrous Investigation

John Watrous was the La Pointe Indian Agent during and after the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850, an event that left four hundred Ojibwe dead in northern Minnesota. The year after the tragedy, official charges were made by the Lake Superior Ojibwe against the agent for his repeated attempts to remove them from their homeland. The charges included broken promises, daily deception, personal self-interest, bribery, and a general lack of interest in the Indian welfare. The charges were sent to Minnesota Territorial Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs Alexander Ramsey for investigation.

Ramsey’s immediate response was to deny the charges, which he believed were politically motivated and he argued that in pursuing removal efforts Watrous was only following orders. Then, rather than meet with members of the L’Anse band of Ojibwe where the charges originated, Ramsey sought statements from Reverends William Boutwell and Sherman Hall and from Minnesota Territorial Delegate Henry Sibley.

In 1852, Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey exonerated Indian Agent John Watrous for his role in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. A year later, Ramsey was facing his own charges of misconduct for his role in the Sioux treaties of 1851. Ramsey was also exonerated. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

In 1852, Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey exonerated Indian Agent John Watrous for his role in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. A year later, Ramsey was facing his own charges of misconduct for his role in the Sioux treaties of 1851. Ramsey was also exonerated. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.Once informed of the charges, Watrous called them “ridiculous” and stated that he would hold himself “in readiness to repel and prove the falsity of every charge made against” him. Watrous also criticized the Ojibwe arguing that any statement coming from the Indians had little weight “as a barrel of Pork and Flour or a glass of Whiskey” (White, The Removal Context, 228).

While Ramsey investigated the charges, more charges were made by other Ojibwe bands. But Ramsey ignored them, arguing that they all came from the same source. Then, while writing to Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea, Ramsey overlooked all charges against John Watrous stating that the charges were difficult to investigate because they lacked specificity, that he believed Watrous and others who refuted the charges, and that the charges had little credence because they were probably manufactured by white men. Ramsey closed his letter to Lea by writing that Watrous had acted “faithfully to the Govt. and with kindness and honest to the Indians. He deserved the commendation, not the censure of the government” (White, The Removal Context, 240).

Ramsey’s letter was forwarded to the Secretary of the Interior who forwarded them to the President. The President, Millard Fillmore, agreed with Ramsey’s judgement and therefore the charges against John Watrous were not sustained. It would appear then, as argued by historian Bruce White, that Ramsey viewed the investigation against Watrous’ behavior as “a matter of politics, in which the welfare of the Ojibwe was a secondary concern” (White, The Regional Context, 243). And, ultimately, for his role in the Sandy Lake Tragedy, John Watrous was never held accountable.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

December 27, 2018

Resisting Removal: 1853 Payment at La Pointe

Explorer and Fur Trader Robert Stuart negotiated the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe, promising the Lake Superior Ojibwe they would not be removed from their land for the remainder of their lifetimes. Image from Wikipedia.

Explorer and Fur Trader Robert Stuart negotiated the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe, promising the Lake Superior Ojibwe they would not be removed from their land for the remainder of their lifetimes. Image from Wikipedia.In 1842, the Lake Superior and Mississippi bands of Ojibwe signed a treaty with the United States government ceding their territory along the southern boundary of Lake Superior. According to the treaty, the Ojibwe maintained the right to hunt, fish, and gather on the land. Furthermore, they were promised that they could remain living upon the land for the remainder of their lifetimes. Included in the treaty, were annual payments that were to be made to the Ojibwe for twenty-five years. These payments, or annuities, were paid to the Lake Superior Ojibwe at La Pointe, Wisconsin.

Just eight years later, the La Pointe band of Ojibwe were ordered to remove from their homes and told they could no longer receive their annual payment in the ceded territory. Therefore, in 1850 payment was scheduled at Sandy Lake, Minnesota. However, payment was never appropriated from Congress and therefore never received by the Ojibwe. Then, in 1851, payment was scheduled at Fond du Lac on the St. Louis River in Minnesota Territory. This time, payment was delayed causing the Ojibwe to return to their homes without payment. It was then rescheduled at Fond du Lac and made in January 1852. The following year, payment was scheduled at Crow Wing, west of the Mississippi River. Payment was again delayed and very few members of the La Pointe band were willing to make the long trip west. Their goods were stored in the agency warehouse at Crow Wing for delivery in the spring, but in January 1853, the warehouse burned down.

It was not until October 9, 1853, that the annual payment finally returned to La Pointe. This occurred because of a change in administration in which the La Pointe agent John Watrous was replaced by Henry Gilbert. Gilbert’s arrival at La Pointe came as a surprise to the Ojibwe, many of whom had given up hope of receiving payment from the government. It was also a source of celebration. In a letter to his parents, Missionary Leonard Wheeler described the scene at the 1853 payment:

“America does not contain happier company than is congregated on this island tonight. I have been out this eve to some of the lodges to rejoice with those that do rejoice. The payment has thus far been one of the best that has ever been made. They have a great many more goods than usual. This payment took us all by surprise. We knew nothing about it until the Agent came to make the payment. Some of our people were so happy and so excited that they could not sleep the first night” (White, The Regional Context, 267).

Indian Agent Henry Gilbert returned the annuity payment to La Pointe in 1853. Image from Chequamegon History (blog) and attributed to Branch County Photographs.

Indian Agent Henry Gilbert returned the annuity payment to La Pointe in 1853. Image from Chequamegon History (blog) and attributed to Branch County Photographs.In his report of the payment, Gilbert wrote that upon his arrival to La Pointe he found many Ojibwe “reduced to the very extreme of want and poverty and without the aid furnished them many must have perished during the coming winter from cold and hunger” (White, The Regional Context, 267). Gilbert also reported that the Ojibwe expressed many grievances regarding the previous years removal efforts. Concluding his report, Gilbert suggested that it was time for a new treaty—one that would end all removal efforts and provide permanent homes for the La Superior Ojibwe upon their homelands.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

December 26, 2018

States of Incarceration: MNHS Exhibit Sparks Debate

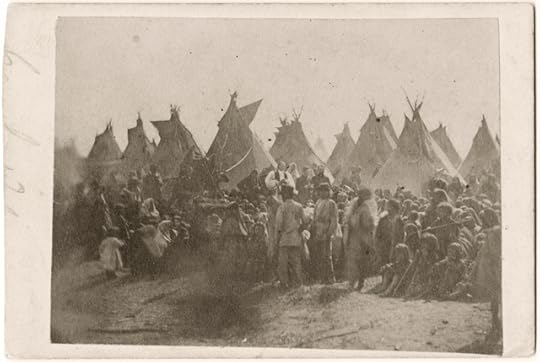

Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple speaks to an audience of Dakota held at Fort Snelling in 1863. Image courtesy of MNHS Collections.

Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple speaks to an audience of Dakota held at Fort Snelling in 1863. Image courtesy of MNHS Collections.In recent weeks, a debate has been sparked by a traveling exhibit called States of Incarceration: A National Dialogue of Local Histories, which is currently being displayed in the Gale Family Library at the Minnesota History Center. As a whole, the exhibit considers states of incarceration in seventeen states throughout the country and is a collaboration of, as stated on their website, “over 800 students and others deeply affected by incarceration” (https://statesofincarceration.org/about-project). Regarding Minnesota, authors of the exhibit have chosen to focus on the high rates of incarceration among Natives and have titled this portion of the exhibit, “Carceral Colonialism: Imprisonment in Indian Country.” Authors of this portion of the exhibit have sought to investigate “the disproportionate rate of American Indian incarceration in the state” (https://statesofincarceration.org/states/minnesota-carceral-colonialism-imprisonment-indian-country). In doing so, researchers wish to consider the full context of the Native experience by exploring Minnesota’s history of exploitation toward Native populations. This includes the U.S. – Dakota War and its aftermath. In particular, the camp of innocent Dakota people who were held at Fort Snelling during the winter of 1862-63 and who were eventually exiled from the state.

The controversy arose when a local historian, Curtis Dahlin, published an article in the Star Tribune titled, Counterpoint: U.S.–Dakota Historical Exhibit Gets Some Things Wrong (Nov. 30, 2018). In his article, Dahlin points out what he believes are historical inaccuracies while also claiming intentional bias are the part of the exhibit’s authors. Also, Dahlin takes issue with the term “concentration camp” calling it “a flagrant misrepresentation.”

Dahlin’s article sparked numerous responses. The first of which was published in the Star Tribune on December 5, 2018, titled, Counterpoint: Remember the Trauma of the Dakota in Recalling the 1862 War by John R. Legg. Legg argues that “for decades, the overarching theme of white victimhood and American innocence dominated the contested history,” and he claims that Dahlin’s analysis “neglects the suffering of exile from western Minnesota to Fort Snelling . . .” Legg concludes by stating that “continued misunderstandings about Dakota War history mean historical accuracy is lost and pain still forced on the indigenous population.”

Further criticism on Dahlin’s essay came in an article published by the Star Tribune on December 10, 2018, titled, Counterpoint: Paint the Dakota’s Plight in the Winter of 1862 as it Was—Horrific by Charles R. Vig, Shelley Buck, and Brian Pendleton. Author’s of this article state that “Dahlin downplays the long record of the federal government’s coercion of the Dakota people,” and call Dahlin’s article “an effort to minimize the tragedy that befell our ancestors.”

In a final response, the Minnesota Historical Society published an article on December 11, 2018, titled Elevating Historically Silenced Narratives Long Overdue by Kate Beane. Beane, who is a member of the Flandreau Santee Sioux, takes issue with Dahlin’s language when he called the Dakota people “dependents” of the United States and she argued against Dahlin’s comment that the camp at Fort Snelling was a “compassionate response by the white authorities.” Rather, Beane argues that “Native American voices serve as a lens through which the story of mass incarceration is told” and she concludes by stating, “we have not relinquished the right to speak for ourselves to interpret our own story—our history matters.”

Finally, on December 19, 2018, an article in support of Dahlin’s original critique was published by the Star Tribune titled, Counterpoint: After the 1862 War, Authorities Tried to Shield the Dakota From Revenge. The article was written by eight independent historians who state that they “have spent years studying the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862.” The authors of this article consider the context of the camp at Fort Snelling which followed the death of approximately 600 white settlers at the hands of Dakota combatants. The authors argue that had the innocent Dakota been left alone on the prairie they might have died from starvation or the attacks of incensed whites seeking revenge. They conclude by stating that “the story of the Dakota and other tribes is compelling enough without incorrect assertions.”

What this exhibit and its public debate clearly shows is the unresolved tension surrounding the tragic and controversial history of our state. What began as an academic endeavor to evaluate the disproportionate rates of incarceration among Natives, has boiled over into a passioned, emotional argument regarding the portrayal of historical events. I do not wish to argue the historical accuracy of certain figures, nor to consider the linguistic nuances of certain terms. I acknowledge that those are important factors in order to understand our history, but I do not believe it is productive under these circumstances.

As a Minnesotan, and someone deeply curious about the complex history of my home, I am disheartened by a debate which, seems to me, lacking in understanding and fruitfulness. I don’t believe Dahlin meant any harm when he published his observations. Dahlin is one the most prolific authors regarding the U.S.–Dakota War and has published thoughtful, well-researched books about both sides of the war. Also, I don’t believe his critics meant to degrade the perspective of whites who also suffered greatly as a result of the U.S.–Dakota War. I think what’s missing, is the understanding that all of us, whether Indian or white, historian or amateur, are seeking the same goal. Ultimately, we all seek to reconcile our past that we might create a more just, equal, and enduring society.

Minnesota was not established without strife, suffering, or exploitation. Neither is understanding achieved without challenging our past while engaging in discussion with one another. This often leads to controversy. But we must remember that our understanding is influenced by our own experience. Because of this, so is history. In order to achieve understanding, we must acknowledge the perspectives of others and respect their experience while adding it to our own. Emotion is not without its usefulness, but as we strive to comprehend and (hopefully) right the wrongs of our past, we must not be carried away by our own self-righteous determination for vindication of our own biased viewpoints.

Read history. Study history. Talk to your friends, neighbors, and teachers. But do not broaden the discussion to fit your needs. Indeed, write your own thoughtful history that it might be added to the discussion—that it might become a part of the historiography. The exhibit, States of Incarceration, is now a part of that historiography. See it. Filter it. Use the information you find to broaden your understanding. If it is biased, why might the authors write this way? Does it overcompensate for a previously dominant narrative? Should it? Or, should it be more balanced? As you read and interpret history, ask yourself these questions. What did the author include? What did the author exclude? When and under what context was it written?

One hundred fifty-six years after the hanging of thirty-eight Dakota people in Mankato (+2 at Fort Snelling in 1865), there is still a need for healing. There is also, and perhaps always will be, a need for historical scholarship to further vet and understand the complexities of our convoluted past. Reconciliation will not be easy, but it is possible.

On January 8, 2019, the Minnesota Historical Society will host an event titled, States of Incarceration Conversations: Emerging Leaders. This will be a good place to add to your perspective and contribute to the discussion.

December 18, 2018

Resisting Removal: Benjamin Armstrong

Benjamin Green Armstrong. Image from the historical blog Chequamegon History as it appears in Armstrong’s memoir.

Benjamin Green Armstrong. Image from the historical blog Chequamegon History as it appears in Armstrong’s memoir.Benjamin Green Armstrong was trader, store owner, logger, farmer, and interpreter who lived among the Lake Superior Ojibwe for many years. He is most well known for his memoir, Early Life Among the Indians, which was published in 1892. In it, Armstrong gave a detailed account of the Ojibwe delegation to Washington DC in 1852 to meet with President Millard Fillmore. The delegation sought the support of the president in their efforts to countermand the Removal Order of 1850 which resulted in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Armstrong’s memoir also recounted important treaties, described the arrival of settlers, miners, and loggers, and described Ojibwe law, customs, religion, culture, language, and history.

Armstrong was born in Alabama in 1820. As a boy he was “decoyed away” from his home by the owner of a horse-racing show (Armstrong, Early Life, 261). According to Armstrong he became a very accomplished horse racer before he had taken ill and could no longer race. Still just a teenager, Armstrong headed north at the advice of his doctors. By the 1840s, he moved to La Pointe in Wisconsin Territory and he married an Ojibwe woman.

For many years Armstrong acted as a trader and interpreter among the Ojibwe at La Pointe. He quickly earned their trust and helped defend their right to remain living at La Pointe against the wishes of the U.S. government. In 1852, he traveled with an Ojibwe delegation to Washington DC and acted as interpreter for the La Pointe Ojibwe during treaty negotiations in 1854. He was so well-liked he was adopted as the son of Chief Buffalo, the foremost elder among the Ojibwe at that time, and he was given the name Shaw-Bwaw-Skung, meaning, the man who goes through. He was also rewarded with a plot of land as a result of the 1854 treaty.

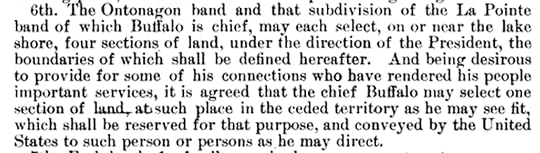

According to Article 6 of the 1854 treaty, Chief Buffalo was to set aside land for those “who have rendered his people important services.” Armstrong claims he was one of those people.

According to Article 6 of the 1854 treaty, Chief Buffalo was to set aside land for those “who have rendered his people important services.” Armstrong claims he was one of those people.However, there is still much that is unknown about Armstrong. His memoir, which has been cited numerous times over the years, is a personal account in which he openly admits that there are errors in his recollection. He was also mentioned in two Supreme Court cases regarding his rights to the land he was awarded in 1854. One historian has questioned Armstrong’s right to that land and his intentions toward the Ojibwe writing, “There is no doubt that Benjamin Armstrong was a shady character.” The same historian claims that Armstrong “swindled (Chief) Buffalo’s children out of the land on September 17, 1855 for the sum of one dollar” (An Ethnographic Study, 104, 99). In most cases, Armstrong is remembered as a friend to the Ojibwe who worked hard on their behalf, but it also seems possible that he used his position and influence for personal profit.

Read Benjamin Armstrong’s Memoir.

Sources:

“An Ethnographic Study of Indigenous Contributions to the City of Duluth,” Turnstone Historical Research, Published July 2015, http://www.duluthmn.gov/media/461501/....

Armstrong, Benjamin Green. Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences From the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong. Dictated to and Written by Thomas P. Wentworth. Ashland, Wisconsin: A.W. Bowron, 1892).

Travis Armstrong, “Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong,” accessed June 2, 2018, http://www.chiefbuffalo.com/buffalo/T....

December 11, 2018

Resisting Removal: The Seven Grandfathers

Passed down from generation to generation, the Ojibwe oral tradition includes the teachings of the Seven Grandfathers. The teachings, which are represented by animals that share in the Ojibwe existence, are guiding principles that are used as a moral stepping stone and cultural foundation. Generally, the teachings of the Seven Grandfathers, also thought as gifts, appear in a circle and they symbolize what is defined by Minobimaadizi/Living Well.

[image error]Dibaadendiziwin/Humility – Humility is represented by the wolf who lives life for his pack. Humility is to know that you are a sacred part of creation.

[image error]

Aakodewewin/Bravery – Bravery is represented by the Bear because the mother bear faces her fears to protect her young. Bravery is to defend what you believe and what is right for your community.

Gwekwaadziwin/Honesty – Honesty is represented by the Raven [image error]who accepts himself and knows how to use his gifts. To be honest is to accept who you are.

[image error]Nibwaakawin/Wisdom – Wisdom is represented by the Beaver because he uses his natural gifts wisely for survival. To be wise is to use your inherent gifts and to live your life by them.

Debwewin/Truth – Truth is represented by the turtle who lives in a slow, meticulous manner because he understands the importance of both the journey and the destination. To be true is to show honor and sincerity in all that you say and do.

Debwewin/Truth – Truth is represented by the turtle who lives in a slow, meticulous manner because he understands the importance of both the journey and the destination. To be true is to show honor and sincerity in all that you say and do.

[image error]Minwaadendamowin/Respect – Respect is represented by the Buffalo who gives every part of his being to sustain the human way of living. To be respectful is to not waste and to be mindful of the balance of all living things.

Zaagidiwin/Love – Love is represented by the eagle who has the strength to carry all teachings. To know love is to view your inner-self from the perspective of all teaching.

Zaagidiwin/Love – Love is represented by the eagle who has the strength to carry all teachings. To know love is to view your inner-self from the perspective of all teaching.

Learn more about the Seven Grandfathers on Ojibwe.net.

Sources:

Michele O’Brien, “7 Grandfather Teachings,” Anishinaabeg Bimaadiziwin: An Ojibwe Peoples Resource, Accessed June 5, 2018, http://ojibweresources.weebly.com/oji....

“The Gifts of the Seven Grandfathers,” Ojibwe.net, Accessed June 5, 2018, http://ojibwe.net/projects/prayers-te....

“Niizhwaaswi Mishomis Kinoomaagewinawaan,” Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture and Lifeways, Accessed June 5, 2018, http://www.sagchip.org/ziibiwing/abou....

Images from WikiMedia Commons.

December 4, 2018

Resisting Removal: John S. Watrous

Appointed April 19, 1850, John S. Watrous was the Indian sub-agent at La Pointe during the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the removal efforts that followed. Prior to his appointment as sub-agent, Watrous served in the Wisconsin Territorial Legislature and later became a trader among the Lake Superior Ojibwe. In 1848, he was granted license to trade with the Ojibwe at La Pointe, but because of excessive competition that year, Watrous was unable to collect on credits given and was forced to sell his entire business.

Following his failure in the trade, Watrous lobbied to have the sub-agent at La Pointe, John Livermore, removed. With the help of his political associates, Watrous was successful and was himself appointed sub-agent.

Following the orders of Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey, John Watrous orchestrated the attempted removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to Sandy Lake in Minnesota Territory. The Ojibwe were opposed to removal from their homelands, but were forced to travel to Sandy Lake in October if they were to receive their much needed annuities. According to their plan, Watrous and Ramsey sought to convey the Ojibwe to Sandy Lake, and hold them their so long that once they received payment, winter would have set in and the Ojibwe would not be able to return home.

Watrous promised payment on October 25, but, while the Ojibwe assembled and waited at Sandy Lake, he failed to arrive until November 24. Upon arrival, Watrous found that scores of Ojibwe had died from spoiled provisions and that more were dying each day. Making matters worse, annuity money had not been appropriated by Congress and so Watrous could not follow through with the annuity payment. After arranging for traders to supply goods for the sick and starving at Sandy Lake, the Ojibwe returned home in early December. But, by that time the waterways had frozen over and the Ojibwe had to throw away their canoes and travel home on foot. Approximately 230 Ojibwe died while trying to return home.

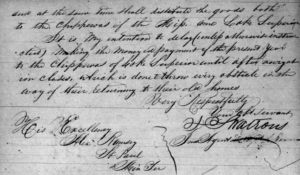

In this letter to Alexander Ramsey, John Watrous states that he intends to intentionally delay the Ojibwe annuity payment in order to prevent them from safely returning home. Letter from the Manuscript Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

In this letter to Alexander Ramsey, John Watrous states that he intends to intentionally delay the Ojibwe annuity payment in order to prevent them from safely returning home. Letter from the Manuscript Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.Despite the tragedy at Sandy Lake in 1850 that resulted in the death of 400 Ojibwe, Watrous tried to institute the same plan for removal the following year. Writing to Governor Ramsey in September, 1851, he stated that it was his “intention to delay the money payment of the present year to the [Ojibwe] of Lake Superior, until after navigation closes, which is done to throw every obstacle in the way of their returning to their old homes” (White, The Regional Context, 215).

In 1852, Watrous again refused to make payment at La Pointe, despite numerous petitions to end removal efforts. Furthermore, Watrous ignored orders from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea to stop removal efforts, and he tried, unsuccessfully, to prevent a La Pointe Ojibwe delegation from traveling to Washington DC in 1852. Numerous charges were made against Watrous for his conduct as sub-agent, including repeatedly breaking promises, daily deception, and attempted bribery. But, it was determined by Alexander Ramsey, who had the final say in the investigation against Watrous, that the charges should not be sustained.

Watrous was eventually removed as sub-agent of La Pointe in 1853 after a new administration took office. After his removal, annuity payments to the Lake Superior Ojibwe resumed at La Pointe to the great joy and satisfaction of those residing there. Also, in 1854, a new treaty was made promising that payment would always be made at La Pointe and providing the Lake Superior Ojibwe permanent reservation homes within their homeland.

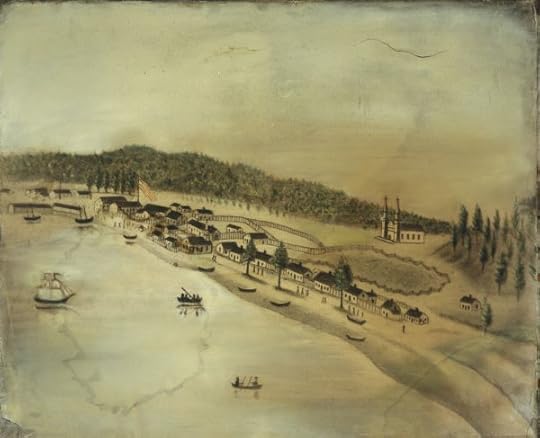

View of La Pointe (1843) on Madeline Island, the homeland of the Ojibwe people. Sketch from the Wisconsin Historical Society and purportedly done by a Native American youth.

View of La Pointe (1843) on Madeline Island, the homeland of the Ojibwe people. Sketch from the Wisconsin Historical Society and purportedly done by a Native American youth.During his time as Indian sub-agent at La Pointe, John Watrous sought the forced and illegal removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to Minnesota Territory in order to support his own business and political interests. His efforts resulted in the death and suffering of countless Ojibwe peoples, for which he received no disciplinary action. For his role in the failed removal efforts, Watrous has been called the most conspicuous villain of the Sandy Lake Tragedy (Filipczak, “Memoirs of Doodooshaaboo”).

Read John Watrous’ Annual Report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the year 1851.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

Leo Filipczak, “Memoirs of Doodooshaaboo: Joseph Austrian’s Time at La Pointe 1851–52 (Pt. 1)” in Chequamegon History (blog), Published April 12, 2014, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

November 27, 2018

Resisting Removal: Oshoga

In the years following the Sandy Lake Tragedy, Chief Oshoga of La Pointe emerged as a charismatic and capable leader second only to Chief Buffalo. During that time he signed numerous petitions against removal, he traveled with a delegation to St. Paul to meet with Governor Alexander Ramsey in 1851, and he traveled with a delegation to Washington DC to meet with President Millard Fillmore in 1852. During the meeting with the president, according to the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong, Oshoga gave a long speech explaining the Ojibwe understanding of the treaties of 1837 and 1842 and expressing their grievances over the conduct of their agent and the removal efforts.

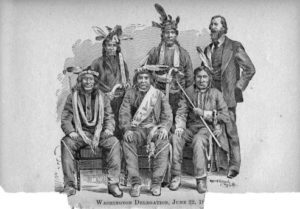

Chief Oshoga is shown in this image of the La Pointe Delegation to Washington, June 22, 1852. Image found in the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong.

Chief Oshoga is shown in this image of the La Pointe Delegation to Washington, June 22, 1852. Image found in the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong.Unfortunately, Oshoga died in February 1854 during a smallpox epidemic. According to Richard E. Morse, who was present at the La Pointe annuity payment of 1855, Oshoga “was a young chief, of rare promise and merit; he also stood high in the affections of his people” (Oshogay, Chequamegon History). Morse also recorded a speech by a young Ojibwe named “Hole in the Sky” who said, “We had but one man among us capable of doing business for the Ojibwe nation; that man was Oshoga, now dead and our nation mourns. Since his death we have lost all our faith in the balance of our chiefs” (Morse, 361).

Oshoga, who may or may not have been originally from La Pointe, spoke out adamantly against the conduct of their agent John Watrous, and he stood firm for the rights of his people to remain living upon their homeland at La Pointe. It appears Chief Buffalo, who was over ninety years old by 1850, was grooming him to be the next great leader of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Sadly, he did not get that chance and, after the death of Chief Buffalo in 1855, it left a leadership vacuum during the reservation period that followed (Oshogay, Chequamegon History).

Read “The Chippewas of Lake Superior” by Richard F. Morse.

Sources:

“Oshogay,” Chequamegon History (blog), Published August 12, 2013, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.com/2013/08/12/oshogay/.

Richard E. Morse, “The Chippewas of Lake Superior,” in Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Volume 3, (Madison, Calkens and Webb, Printers, 1857),p. 338–369.

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

November 20, 2018

Resisting Removal: La Pointe Delegation to Washington 1852

On April 5, 1852, a small delegation of Ojibwe led by chiefs Buffalo and Oshoga, departed their island home at La Pointe in route for Washington DC. The delegation sought a meeting with the President in order to express their grievances related to the conduct of their agent, John Watrous, and the disastrous removal efforts that caused the Sandy Lake Tragedy less than two years earlier.

The La Pointe Delegation to Washington, June 22, 1852. Image found in the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong.

The La Pointe Delegation to Washington, June 22, 1852. Image found in the memoir of Benjamin Armstrong.At the time of the journey, the La Pointe Ojibwe were under increasing pressure from government officials to remove from their ancient homeland on Madeline Island, and resettle in Minnesota Territory. The Ojibwe were adamantly opposed to removal, citing promises made during a treaty in 1842 that they could remain living upon their homeland for fifty to one hundred years. After several petitions failed to end removal efforts, the Ojibwe decided the only way to save their home was to visit their “Great Father” in Washington. Several times the Ojibwe asked for permission from their agent John Watrous, and from Minnesota Territorial Governor, Alexander Ramsey, to travel to Washington, but every time their request was either ignored or declined.

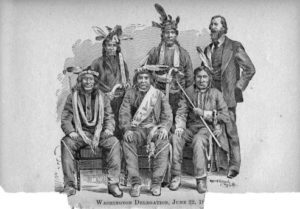

With the help of interpreter Benjamin Armstrong, the delegation set off for Washington by canoe, never having received permission. Along the way, the delegation made many stops in order to raise funds and obtain signatures on a petition urging the end of removal efforts. After reaching Sault Ste. Marie the delegation traveled by steamship to Detroit, then by sail to Buffalo. From Buffalo to Albany the delegation traveled by train and then by steamer down the Hudson River to New York. While in New York, the delegation performed traditional Ojibwe dances to earn enough money for the last leg of their trip. Finally, they traveled overland to Washington DC where they arrived on June 22, 1852.

Journey of the La Pointe Delegation to Washington in 1852.

Journey of the La Pointe Delegation to Washington in 1852.While in Washington, the group was declined a meeting with the President by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea who told them to turn around and go home. However, a fortuitous encounter with two Congressmen at their hotel led to the arrangement of a meeting with President Millard Fillmore. During their meeting, Chief Oshoga gave a detailed account of all the wrongs done to the Lake Superior Ojibwe dating back to the Treaty of 1837. Moved to action by the sorrowful tale, Fillmore agreed to end the removal efforts and resume annuity payments at La Pointe. The following year payment was made a La Pointe and in 1854 a new treaty was signed which provided the Ojibwe with permanent reservation homes within their homeland.

Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke). Image from the Wisconsin Historical Society, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Reco....

Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke). Image from the Wisconsin Historical Society, https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Reco....A complete account of the delegation’s trip to Washington is available through the memoir of interpreter Benjamin Armstrong. However, it should be noted that the veracity of Armstrong’s account has been called into question. According to historian Bruce White, there is conflicting evidence regarding the meeting with the President. Several reports would lead one to conclude that the delegation was simply intercepted by Luke Lea and handed off to Agent John Watrous for a return trip home. But, there is also proof that the petitions were handed to the President by someone other than the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, which would have likely been the delegation itself. Whether or not the delegation met with the President is still a matter of question.

Ultimately, the decision regarding removal was left with Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey. In a letter written by chiefs Buffalo and Oshoga shortly after their return from Washington, they acknowledged this fact writing, “My father I have just returned from Washington. I learned that you were the one that had to say that we had to go or stay. If that is the case do as you agreed that you would do, last winter when I visited you, you told me that if it was left for you to say you would do all that was in your power to have us stay at La Pointe. It is left to you to say whether we will be permitted to remain or not” (White, 254).

Read Benjamin Armstrong’s account of the trip to Washington.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

Benjamin Green Armstrong, Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences From the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong, Dictated to and Written by Thomas P. Wentworth, (Ashland, Wisconsin: A.W. Bowron, 1892).

November 17, 2018

New Website – History Through Fiction

In combination with the upcoming release of his new novel, Resisting Removal, author Colin Mustful is proud to announce the launch of his independent press, History Through Fiction. Using his experience self-publishing four novels and his knowledge gained through his creative writing program at Augsburg University, Mustful seeks to publish high quality fiction that is rooted in accurate and detailed historical research. The goal of History Through Fiction is to provide readers with a compelling narrative that can also act as a valuable historical resource, much like the novels Mustful has already published. To find out more, you can visit his new website at historythroughfiction.com.

Mustful would also like to announce that pre-orders are now available for his upcoming novel, Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850. Orders are direct through the author and those ordering will receive a signed copy as soon as copies are available following the literary review process. You can learn more about Mustful’s upcoming novel by reading his feature article. For questions regarding pre-orders, please direct them to the author at mnauthor@colinmustful.com.

November 14, 2018

MNopedia: Sandy Lake Tragedy

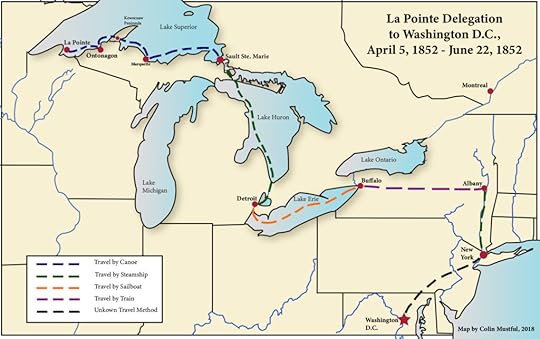

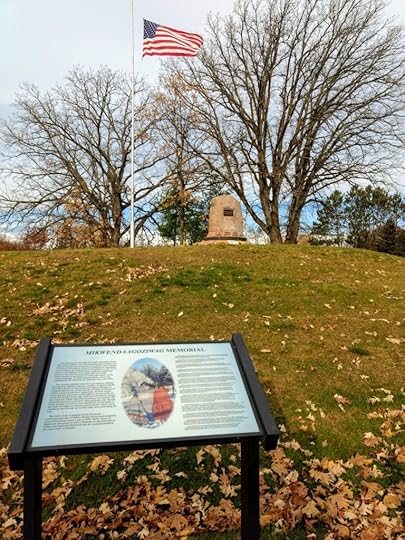

Mikwendaagoziwag Memorial at Sandy Lake

Mikwendaagoziwag Memorial at Sandy LakeAuthor Colin Mustful has recently published an article in MNopedia, an online encyclopedia about Minnesota developed by the Minnesota Historical Society and its partners. The article, which is about the Sandy Lake Tragedy, precedes his upcoming novel of the same topic. Mustful encourages Minnesotans to learn more about the history of this region and how it came to be the place they call home. Through awareness and understanding of these complicated and often tragic events, Mustful hopes facilitate discussion and healing. Find the article at MNopedia.org to learn more about the Sandy Lake Tragedy.