Colin Mustful's Blog, page 19

September 12, 2018

Resisting Removal: The Removal Order of 1850

On February 6, 1850, President Zachary Taylor signed an executive order revoking the usufructuary rights of the Lake Superior Ojibwe under the treaties of 1837 and 1842 and ordering the removal of the Ojibwe from the ceded territory. The usufructuary rights included those of hunting, fishing, and gathering wild rice. The land ceded, were those lands west of the Mississippi River and south of Lake Superior that had previously been sold by treaty.

Land ceded at the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe. Map by CJ Lippert and found Wikimedia Commons.

Land ceded at the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe. Map by CJ Lippert and found Wikimedia Commons.The origins of the removal order can be traced back to the year 1830 when President Andrew Jackson issued the Indian Removal Act authorizing American officials to negotiate with Indian tribes for their removal west of the Mississippi River. At the time, the Lake Superior region was almost completely unsettled and so officials saw no reason to ask the Lake Superior Ojibwe to remove. Rather, the Indian Removal Act had a much greater impact on those tribes living throughout the southern half of the United States. One notable outcome was the Cherokee Trail of Tears in 1835.

In 1842, the Lake Superior Ojibwe signed a treaty in which they agreed to sell the mineral rights to their lands. However, according to the treaty, they maintained the right to hunt, fish, and gather upon the ceded lands. The Ojibwe signed the treaty because of the promise of treaty commissioner Robert Stuart who said that they would not be asked to remove from their homes for fifty to one hundred years.

A few years later, politicians began to pressure for the removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe from the ceded land to the unceded land in Minnesota Territory. The major impetus for this was benefit that removal would have on the politicians, traders, businessmen, and contractors of Minnesota. If the annuity were paid in Minnesota, it would provide Indian patronage jobs and it would bring money into the territory that would benefit merchant suppliers and traders. It would also lead to new Indian agencies and the building of schools, farms, blacksmith shops and the employment of skilled workers to staff such facilities.

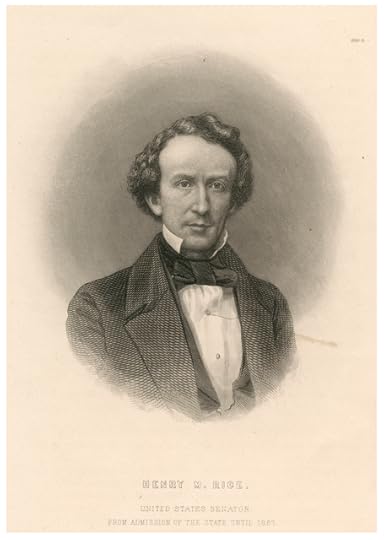

Trader Henry M. Rice favored removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Image from the MNHS Collections.

Trader Henry M. Rice favored removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Image from the MNHS Collections.Trader Henry M. Rice openly advocated for the Ojibwe removal in a letter to Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey writing, “They should be removed from the ceded lands–they should receive their annuities on the Mississippi River…This would better accommodate the whole tribe–and Minnesota would reap the benefit–whereas now their annuities pass via Detroit and not one dollar do our inhabitants get” (Clifton, Preliminary Report, 61).

Ramsey was apparently of the same mind because, in September 1849, he urged the Territorial Assembly to write a memorial to Congress for the Ojibwe removal. The Territorial Assembly agreed and on November 7, 1849, they approved a resolution for the removal of the Ojibwe from the ceded territory. The resolution was sent to Congress who then forwarded it to the President. As a result, the Removal Order of 1850 was signed and all rights granted the Ojibwe in the treaties of 1837 and 1842 were cancelled. Less than a year later, the forced removal to Minnesota Territory resulted in the death of four hundred Ojibwe at Sandy Lake.

Read the Removal Order signed by President Taylor on February 6, 1850.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

Charles E. Cleland, “Preliminary Report of the Ethnohistorical Basis of the Hunting, Fishing, and Gathering Rights of the Mille Lacs Chippewa,” Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 1–140.

James A. Clifton, “Wisconsin Death March: Explaining the Extremes in Old Northwest Indian Removal,” in Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, Vol. 75, (1987): 1–40.

September 4, 2018

Resisting Removal – Ojibwe Migration

Long before the Ojibwe people lived on reservations throughout northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, they lived in the northeast alongside what they called the Great Salt Water. It has been said that long ago their “people were so many and so powerful that if one was to climb the highest mountain and look in all directions, they would not be able to see the end of the Ojibwe nation” (Swan, Who We Are as Anishinabe). But, one day they were instructed by the great Megis (sea-shell) to migrate west or they would be destroyed. The great Megis said they were to stop once they reached an island shaped like a turtle and then later the place where the food grows on water.

Around the 900 CE the Ojibwe began their migration, moving west along the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes along with the Ottawa and Potawatomi people, settling and resettling along the way. Once they reached the confluence of Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron, the three groups split up.

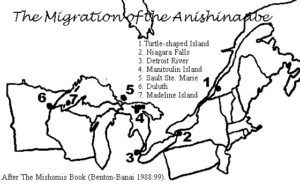

Ojibwe Migration from The Mishomis Book by Eddie Benton Banai

Ojibwe Migration from The Mishomis Book by Eddie Benton BanaiThe Ojibwe split into two groups—one settling along the northern shore of Lake Superior and one settling along the southern shore. Those who migrated along the southern shore finally settled at Moningwunakauning, the place of the golden-breasted woodpecker. Today, this place is called La Pointe, or Madeline Island. Here the Ojibwe found Manomin (Wild Rice) growing on the waters in Chequamegon Bay. It was the place the creator had foretold—the place where food grows on water.

The Ojibwe thrived at Moningwunakauning which became the spiritual and economic center of Ojibwe life. It is estimated that there once lived a large community of Ojibwe on the island that numbered over 10,000 people. Over time, it became their ancient homeland. Eventually, the Ojibwe people spread throughout the region into Wisconsin, Minnesota, and as far west as Montana.

Learn more about the Ojibwe people from the Minnesota Historical Society.

Sources:

Mike Swan, Who We Are as Anishinabe, Accessed May 28, 2018, http://anishinaabemodaa.com/data/upfiles/media/Who%20Are%20We%20-%20Seven%20Prophets.pdf.

“The Ancient History of the Ojibwe People to the Nineteenth Century,” Wiigwaasi-Jiimaan: Birchbark Canoe, Accessed May 28, 2018, https://canoe.csumc.wisc.edu/LdFCanoe_subpage_North_History_1.html.

Thomas Peacock and Marlene Wisuri, Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions, (Afton, MN: Afton Historical Press, 2002).

August 21, 2018

Resisting Removal – The Sandy Lake Tragedy

On February 6, 1850, President Zachary Taylor signed an executive order for the removal of all Ojibwe living within the lands ceded by the treaties of 1837 and 1842. This was done in response to a Resolution of the Minnesota Legislative Assembly issuing the same order.

The Lake Superior Ojibwe who were affected by the order, refused to remove from their homeland, citing promises made by the United States government during the treaty negotiations in 1842. The treaty gave timber and mineral rights to the U.S., but the Ojibwe maintained the right to hunt, fish, and gather upon the lands. Furthermore, they were told that they would not be asked to remove for fifty to one hundred years.

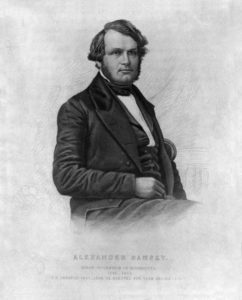

Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey played a large role in the attempted removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe which resulted in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey played a large role in the attempted removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe which resulted in the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.Because of their reluctance, Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey devised a plan to force the Ojibwe removal which would be instituted by Indian Agent John Watrous. Ramsey changed the location of the annual payment, which the Ojibwe received as a part of the 1842 treaty agreement, from La Pointe, Wisconsin, to Sandy Lake, Minnesota. He then had Watrous advise the Ojibwe that if they wished to receive payment, they had to travel to Sandy Lake along with their families to receive it. Ramsey’s intention, which he stated outright in letters to John Watrous, was to lure the Ojibwe into Minnesota Territory, and then intentionally delay payment so that winter would set in and the Ojibwe would be unable to return to their homes.

The Ojibwe were told by their agent that they would receive payment at Sandy Lake on October 25, 1850. More than four thousand gathered from all parts of the region. However, the agent was not there to greet them. They waited many weeks while at the same time, the rations they were fed were spoiled. Hundreds became sick with dysentery and died. The agent did not arrive until November 24, and when he did he did not have the annual payment because it was never appropriated by Congress.

After negotiating with traders who greatly inflated their prices, Watrous gave the Ojibwe what he could in order to sustain them. But, by the time the goods had been distributed, winter had set in and the waterways had frozen over, forcing the Ojibwe to throw away their canoes and begin the long trek home on foot. On the way, many suffered and perished from sickness and starvation.

On December 17, The Minnesota Chronicle and Register gave a report of the conditions at Sandy Lake titled, “Dreadful Sufferings of the Indians.” It stated:

“The Chippewa payment has just come off. A more miserable set of Indians I never saw – most of them half dead for want of food – not less than eighty-five dead at Sandy Lake – and since the payment, some five or six die every night. I cannot describe the distress of this poor people, and should I, it could not be believed, for it is incredible.”

A week later, the Minnesota Chronicle and Register estimated that no fewer than 167 Ojibwe died at Sandy Lake. It was estimated that another 230 died on the way home. Despite this tragedy, removal efforts continued the following year and neither Ramsey or Watrous were punished for their involvement in the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

Read “Wisconsin Death March” by James A. Clifton.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

James A. Clifton, “Wisconsin Death March: Explaining the Extremes in Old Northwest Indian Removal,” in Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, Vol. 75, (1987): 1–40.

August 16, 2018

Review: The American Soldier, 1866–1916

Whether well-versed in the history of the U.S. Army or a novice to the subject, John A. Haymond’s The American Soldier, 1866–1916: The Enlisted Man and the Transformation of the United States Army is an effective, engaging, and thoughtful work of historical interpretation and writing. Haymond, who served in the U.S. military for twenty-one years, shows his ability as a historian to examine and challenge preconceived notions while exhibiting a realistic, almost personal perspective for the soldiers who fought and died for their country often with little or no recognition for their service and sacrifice. Most notably, though, Haymond demonstrates his keen ability to inform his audience through thorough and careful research that expresses multiple perspectives while drawing unbiased and valid conclusions.

Whether well-versed in the history of the U.S. Army or a novice to the subject, John A. Haymond’s The American Soldier, 1866–1916: The Enlisted Man and the Transformation of the United States Army is an effective, engaging, and thoughtful work of historical interpretation and writing. Haymond, who served in the U.S. military for twenty-one years, shows his ability as a historian to examine and challenge preconceived notions while exhibiting a realistic, almost personal perspective for the soldiers who fought and died for their country often with little or no recognition for their service and sacrifice. Most notably, though, Haymond demonstrates his keen ability to inform his audience through thorough and careful research that expresses multiple perspectives while drawing unbiased and valid conclusions.

Covering fifty years of the history of the U.S. Army, Haymond looks deep into the soldier’s experience throughout the period of Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, and the 1916 Punitive Expedition into Mexico. Rather than rely second-hand accounts, Haymond uses the personal narratives of soldiers, giving a voice to the men who actually experienced this history. In this way, the American soldier is brought to life through his own thoughts, feelings, fears, and anxieties, but is not glorified in those expressions. Haymond does not hide the good or the bad and expresses no personal bias in his interpretation, but instead is forthright and honest showing the soldiers simply as they were—human and fallible. Haymond then uses his own knowledge and expertise of military history and law to examine the real context of the life of a U.S. soldier.

In addition to covering a broad swath of American U.S. Army history, Haymond takes the time to pull apart the well-known but not fully understand events of this time period. This includes events such as the Fetterman Fight, The Battle of Washita River, The Battle of Little Bighorn, Wounded Knee, and the Brownsville Affair. In each case, Haymond dispels misconceptions by first acknowledging those misconceptions and then examining the sources to reveal a more nuanced realistic view of the events. It is both eye-opening and intriguing to discover what happened and why rather than accepting historical bias and giving in to modern revisionism, something Haymond appropriately avoids.

Ultimately, Haymond succeeds in conveying the history of the U.S. Army in an engaging and informative manner free from bias or misconceptions. But more importantly, he does so through the eyes of those who, until now, have been overlooked—the eyes of the soldiers who experienced this history. It was, as one soldier pointed out, “not very pleasant,” but it was real and it should not be forgotten or taken for granted. Haymond shows us why.

August 14, 2018

New Blog Series: Resisting Removal

Historian and author Colin Mustful is proud to announce the release of a new blog series related to his upcoming novel, Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850. The series takes a look at the people, places, and events surrounding the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the illegal removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe that followed. Each post will cover some aspect of the Sandy Lake Tragedy by highlighting the people involved while also providing political and cultural context. Although it is a series, each post is also meant to stand alone and therefore some information may appear redundant. The subject of each post was selected for it’s relevance to the Sandy Lake Tragedy and also because the people, events, and culture, are included as a part of Mustful’s upcoming historical novel Resisting Removal. The series will be released weekly beginning Tuesday, August 21, 2018.

Historian and author Colin Mustful is proud to announce the release of a new blog series related to his upcoming novel, Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850. The series takes a look at the people, places, and events surrounding the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the illegal removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe that followed. Each post will cover some aspect of the Sandy Lake Tragedy by highlighting the people involved while also providing political and cultural context. Although it is a series, each post is also meant to stand alone and therefore some information may appear redundant. The subject of each post was selected for it’s relevance to the Sandy Lake Tragedy and also because the people, events, and culture, are included as a part of Mustful’s upcoming historical novel Resisting Removal. The series will be released weekly beginning Tuesday, August 21, 2018.

Although Mustful relied on numerous sources for the creation of this blog series, he would like to acknowledge the historical blog Chequamegon History, published by Amorin Mello and Leo Filipczak, as an excellent and reliable source of information. Chequamegon History offers a variety of primary source materials related to the La Pointe band of Ojibwe during the 1850s as well as excellent historical commentary by its authors. Mustful would also like to acknowledge an essay by historian Bruce White titled, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” and found within the book Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance. In his essay, White provides a thorough analysis of all actions of U.S. government officials involved with the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe while including relevant and useful citations to primary source material.

Finally, Mustful would like to acknowledge that although much of this blog series reports on Ojibwe history and culture, he is not Ojibwe nor is he affiliated with any Ojibwe tribal groups. Everything posted through this series is a reflection his own perspective which is guided by careful research of Ojibwe and other sources. If you discover an error or misinterpretation please do not hesitate to contact the author that such errors may be changed or deleted.

Mustful is a Minnesota resident who studied history at Minnesota State University, Mankato. His previous works include three historical novels about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 and its preceding context. He has also published an electronic textbook titled Confronting Minnesota’s Past and an online academic course about the U.S. – Dakota War through Udemy.com. Mustful’s previous blog series’ include Fifty Questions and Answers about the U.S. – Dakota War and Lessons from the Novel Ceding Contempt – twenty-five blogs related the 1851 Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota. These blogs have also been published as YouTube videos and can be found on the author’s YouTube channel.

Currently, Mustful is a candidate for a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at Augsburg University in Minneapolis. He hopes his work shedding light on the tragic and complicated events of Minnesota’s past will create awareness and open productive thought and discussion on our country’s historical blemishes. Mustful is open and willing to collaborate with community members in order to create more attention and awareness about these important and misunderstood historical topics. Finally, Mustful is available for public speaking at schools, libraries, historical organizations, book clubs, and elsewhere. He can be reached at mnauthor@colinmustful.com.

August 10, 2018

New Online Bookstore – Minnesota History

Check out my new online bookstore with books, both fiction and nonfiction, related to Minnesota history! Most are books I have read or relied upon for the writing of my novels and historical blogs. If you have recommendations of books I should add to my bookstore, please let me know at – mnauthor@colinmustful.com. – https://aerbook.com/store/ColinMustful.

July 2, 2018

Author Update July 2018

Dear Readers,

I have just completed my series of twenty-five YouTube videos relating to my novel Ceding Contempt. This fall I will be posting a new series of twenty-five blog posts related to the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850 followed by a series of YouTube videos. My current project is a novel about the Sandy Lake Tragedy which has the working title, Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850. The novel has been through several edits and I am now exploring my options for publication. Previously, I have published my books independently through Lulu.com. As I move forward, I will consider traditional and hybrid publishing as a means to help my work reach the largest possible audience.

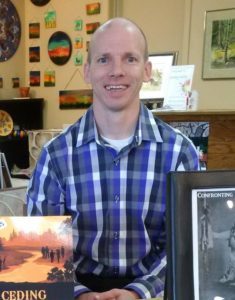

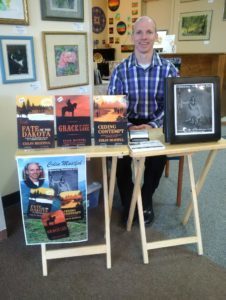

Author Colin Mustful at Gallery North in Bemidji on June 1, 2018

Author Colin Mustful at Gallery North in Bemidji on June 1, 2018Also at this time, I am entering my second year of MFA program in Creative Writing at Augsburg University in Minneapolis. I will be attending an intensive writer’s residency at Augsburg on July 19–29. The Residency will include workshops, craft talks, panels, and lectures from visiting authors. This will help me continue to learn more about the craft of fiction as I seek to make my historical writing more effective, meaningful, and entertaining.

As I focus on graduate school and the publication of my current novel, I have very few events this summer. I will be speaking at the Pond Dakota House in Bloomington on August 19 (http://ponddakota.org/events/program-the-context-of-the-u-s-dakota-war) and I have a tentative speaking engagement in Hutchinson on August 18.

Thanks for reading and best wishes for an enjoyable summer!