Colin Mustful's Blog, page 13

December 22, 2019

Lessons from the novel Resisting Removal: Watrous Investigation

December 15, 2019

Lessons from the Novel Resisting Removal: 1853 Payment at La Pointe

December 8, 2019

The Battle of Sugar Point

Commonly referred to as “the last Indian Uprising in the United States,” The Battle of Sugar Point at Leech Lake hardly meets that definition. Fought October 5 and 6, 1898, between a handful of aggrieved Pillager Chippewa and seventy-seven soldiers of the 3rd U.S. Infantry, the battle resulted in the death of six U.S. soldiers and one civilian police officer, but led to no further violence.

At the time of the battle, the Pillager Band of Chippewa were in the midst of a legal struggle to prevent the theft of timber from their reservation lands. Although logging companies were allowed to harvest dead or downed timber, they often set fire to healthy timber in order to claim it. In a petition to President William McKinley written September 25, 1898, the Pillagers wrote, “We now have only the pine lands of our reservation for our future subsistence and support, but the manner in which we are being defrauded out of these lands alarms us.”

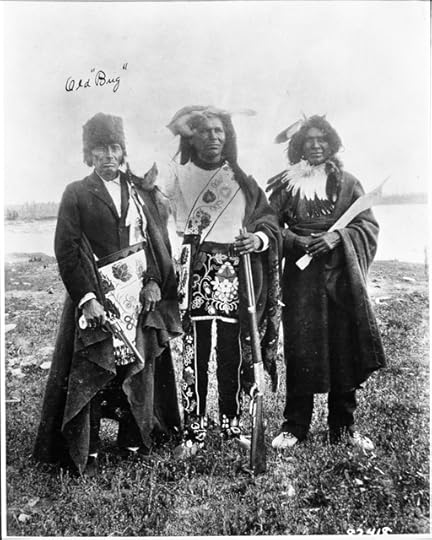

Bugone-giizhig pictured with two other tribal members at Leech Lake, 1897. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

Bugone-giizhig pictured with two other tribal members at Leech Lake, 1897. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections. Additionally, the Pillager and other Ojibwe bands expressed grievances over their frequent and unsubstantiated arrests. The Ojibwe were often taken into custody over dubious charges, transferred to far away cities such as Duluth or Minneapolis, and forced to walk home, a distance of one to two hundred miles. Such was the case with Bagone-giizhig, a 62 year-old Pillager arrested on bootlegging charges in early 1898. Bagone-giizhig, who shares no apparent relation with the earlier chiefs named Bagone-giizhig, was taken to Duluth for trial but was released for lack of evidence. Without money or transportation, Bagone-giizhig walked all the way back to his home at Sugar Point on Leech Lake. Following the experience, he was determined never again to be taken into federal custody.

But, on September 15, 1898, Bagone-giizhig and another Pillager named Sha-Boon-Day-Shkong, were seized in Walker by U.S. Deputy Marshal Robert Morrison and Indian Agent Arthur M. Tinker. The two were taken into custody as witnesses to a bootlegging operation, but before they could be transported a group of local Pillagers came to their rescue, allowing Bagone-giizhig and Sha-Boon-Day-Shkong to escape across Leech Lake to Sugar Point. The U.S. reacted by dispatching twenty soldiers to the area. The soldiers, led by Lieutenant Chauncey B. Humphreys, traveled to Onigum on Leech Lake where councils were held with Ojibwe officials. After negotiations broke down, Agent Tinker and U.S. Marshall Robert T. O’Connor traveled to Bear Island just opposite Sugar Point, but Bagone-giizhig, Sha-Boon-Day-Shkong, and their followers refused to surrender.

In response, a larger force of soldiers were sent to Walker from Fort Snelling. Then, on the morning of October 5, two boats and one barge loaded with several Indian office men, U.S. marshals and deputy marshals, an army surgeon, four reporters, and 77 troops departed Walker for Sugar Point. The troops were commanded by Brevet Major Melville C. Wilkinson and Brigadier General John Mosby Bacon. The troops arrived at Bagone-giizhig’s cabin on Sugar Point and found that neither he nor Sha-Boon-Day-Shkong were present. After searching the area, two Pillagers involved in the earlier rescue were arrested and placed on the boats.

Troops dispatched to Walker and sent to Sugar Point in October, 1898. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

Troops dispatched to Walker and sent to Sugar Point in October, 1898. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections. Although various accounts of the ensuing battle differ, according to the reports of Bacon and his men, at approximately 11:30am while the soldiers were stacking their weapons before lunch, an inexperienced soldier forgot to engage the safety on his rifle causing it to accidentally fire. Fearing they were under attack, the Ojibwe hiding in the woods surrounding the cabin returned fire. The soldiers set up skirmish lines around the cabin, but in the first thirty minutes of battle many U.S. soldiers were wounded and killed, including Major Wilkinson who was mortally wounded in the abdomen. The battle settled into an exchange of volleys which lasted into the evening. That night an Indian police officer was shot and killed by a soldier who mistook him for the opposition. The final casualty of the battle took place the next morning when a hungry soldier was shot and killed while digging for potatoes.

After the battle, panic spread throughout the region and country as false information was disseminated about an Indian Uprising. Newspaper headlines read “Rumored Massacre of One Hundred Soldiers” and “Fierce Fight with Bear Lake Savages in Minnesota.” In Bemidji, residents barricaded themselves in the courthouse until a militia sent from Duluth arrived to protect them from the perceived threat. In Walker, two hundred-fourteen troops arrived armed with a Gatling gun.

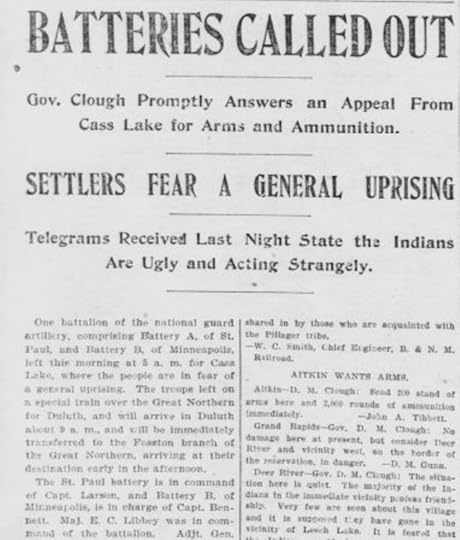

Report of the St. Paul Globe October 8, 1898

Report of the St. Paul Globe October 8, 1898Eventually the panic settled and on October 10, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs William A. Jones negotiated for several days with Pillager leaders at Leech Lake. As a result of the negotiations, several of the September 15 rescuers were given into custody, but none of the men involved in battle were charged or arrested. Also, neither Bagone-giizhig or Sha-Boon-Day-Shkong were arrested for their escape or refusal to surrender. After his return to Washington, Commissioner Jones analyzed The Battle of Sugar Point in a report to the Secretary of the Interior writing: “The Indians were prompted to their outbreak by the wrongs committed against them and chafed under unfair treatment. They now will go back to their homes and live peaceably if the whites will treat them fairly, which is very likely, as the whites were thoroughly impressed with the stand taken by the Indians. In this respect the outbreak has taught them a lesson.”

Funeral held at Fort Snelling for the soldiers killed at Sugar Point. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

Funeral held at Fort Snelling for the soldiers killed at Sugar Point. Photo from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections. Sources:

Title Image – Bug-ah-na-ge-shig, E97.1B p7, Minnesota Historical Society Collections.

William E. Matson, “The Battle of Sugar Point: A Re-Examination,” Minnesota History, 50:7 (Fall 1987), 269–275.

Lauren Peck, “The Battle of Sugar Point,” Minnesota Good Age, Published September 25, 2017, Accessed December 6, 2019, https://www.minnesotagoodage.com/voices/mn-history/2017/09/the-battle-of-sugar-point/.

“The Battle of Sugar Point,” Wikipedia, Last Updated September 9, 2019, Accessed December 6, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Sugar_Point.

December 1, 2019

Lessons from the Novel Resisting Removal: Benjamin Armstrong

November 24, 2019

Lessons from the novel Resisting Removal: The Seven Grandfathers

November 17, 2019

Historical Fiction in the Classroom

I recently discovered an article titled, Using Historical Fiction in the History Classroom by Sarah K. Herz and published by Yale New Haven Teachers Institute. The article effectively articulates the value of historical fiction as an educational resource. To begin, Peck goes beyond traditional historical fiction to define the historical novel. Historical fiction, or, “costume” novels, place fictional characters within a historical setting, but the characters do not directly interact with that setting in a way that reveals historical events or conditions. A historical novel, on the other hand, as defined by Peck, is “about past public events and people and social conditions and [is] based on historical facts.” Additionally, “the historical novelist does not distort historical data for the sake of literary form.” That is an important distinction because, when done well, the historical novel can evoke an intellectual response in addition to an emotional one.

Writing a historical novel with accurate and detailed historical facts is especially challenging for the historical novelist who must blend history and imagination in a deliberate attempt to recreate the past. But doing so creates a more effective tool than traditional textbooks because of the novel’s ability to bring history to life. As Peck points out, “textbook historical figures often become so heroic and extraordinary or so flat and lifeless that students cannot conceive of these people as ordinary men and women endowed with normal human characteristics. Rather, using imaginative and figurative language, historical novels entice students into historical exploration. And, by placing characters in the context of real life (as brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, etc.) students begin to understand history as a human experience. History becomes relatable. Furthermore, students will begin to recognize history not just as past names and dates, but as circumstances and problems that echo through time, allowing students to begin to understand the significance of the study of history.

As Peck adequately argues, historical novels provide students with excitement, adventure, and a good story. But, when written in a way that incorporates historical accuracy in detail and theme, it provides the necessary elements of a meaningful historical exploration through fiction. History can be taught through fiction. Peck includes important and useful guidelines for using historical fiction in the classroom which I will paste below. You can find the complete article here: Using Historical Fiction in the Classroom by Sarah K. Herz.

I. Setting (time and place)

a. Has the author accurately described a particular historical period in the novel? Explain.

b. List some details that describe the historical period and parallel your study of this particular historical period, e.g. geography, transportation, costume or dress, rural, urban, religious mores, social attitudes.

c. Are the details of locale authentic in the novel?

d. Does the description of the locale fit the historical period? Support with specific details.

II. Characters

a. Are there real historical figures whose names you recognize? List them.

b. Do the historical figures belong in the period described?

c. Does a check against the history textbook or biographical materials show that the historical characters are accurately portrayed?

d. Are fictional characters in keeping with the historical setting?

e. List positive and negative character traits of at least four main real or fictional characters. Show parts of the novel that support this trait.

f. Explain the characters’ involvement in the historical setting and events.

g. How are the historical characters important to the action of the novel?

III. Plot (story line)

a. Does the plot focus on a specific historical incident? Explain.

b. Do the historical characters in the novel participate in a well known historical incident? Explain.

c. Is the conflict real or fictional?

d. Do the characters dramatize an eventful moment in the history of Connecticut, or some other familiar place.

IV. Theme

By theme we mean the author’s use of people and events from the past to elucidate some truth about a past era.

a. What social condition in history does the novel reveal?

b. What comment do you think the author is making about this social condition?

c. How can this social condition be related to contemporary life?

d. How do the characters reveal the theme?

e. Does this novel reflect more than one theme?

f. Is there more than one point of view about the theme(s)?

V. Summary

a. Why do you think the author chose to write about this particular historical episode?

b. Is the author revealing any new insights about the historical characters or historical events?

c. Why is this considered a historical novel?

d. Is this novel a good or bad historical novel, based on the previous definition of historical fiction?

November 10, 2019

Lessons from the Novel Resisting Removal: John S. Watrous

Want a copy of Resisting Removal signed by the author?

Buy Now

October 27, 2019

Lessons from the Novel Resisting Removal: Oshoga

October 20, 2019

Lessons from the Novel Resisting Removal: La Pointe Delegation to Washington, 1852

October 14, 2019

How to Write History Through Fiction – A Craft Essay by Colin Mustful

Historical fiction is one of the most popular literary genres. When done well it brings history to life, teaching readers about important historical people and events while also evoking profound, relatable emotions through its characters. But how does the historical author balance history and fiction? In this craft essay, historian and author Colin Mustful carefully examines four Civil War narratives and identifies how each author incorporates important historical details into their novels without disrupting the fictional dream. Mustful, who is the author of several historical novels, identifies the elements that make a historical novel effective and engaging—he shows readers and writers alike how to write history through fiction.

Available for download NOW on Amazon.