Colin Mustful's Blog, page 15

July 14, 2019

Lessons from the Novel Resisting Removal: Ojibwe Lifeways

June 30, 2019

Lessons from the novel Resisting Removal: The Ojibwe in 1850

June 16, 2019

Lessons from the novel Resisting Removal: Alexander Ramsey and the Sandy Lake Tragedy

June 9, 2019

Lessons from the novel Resisting Removal: Chief Buffalo (Kechewaishke)

May 29, 2019

May 28, 2019

Review: The Relentless Business of Treaties

Martin Case begins and ends his book, The Relentless Business of Treaties: How Indigenous Land Became U.S. Property, with the American Myth — a predominant belief that America was settled by rugged pioneerism, justified and predestined by the founding principles and values of the United States despite any obstacles in the way. The myth has survived any challenges against it and now holds a notable place at the center of American history and culture. Case, however, sufficiently dismantles the American myth, demonstrating to readers how political and economic systems worked to absorb indigenous lands and resources while creating wealth for a small class of American elites. These elites were the treaty signers—men with political and business interests who manipulated the bureaucratic treaty system for the benefit of themselves and their close friends and family members.

“Removal of indigenous people from their homelands was a necessary condition for expanding the U.S. property system and the fortunes that grew with it, and their removal was imagined before it was accomplished.”

I recommend reading The Relentless Business of Treaties for a variety of reasons. Foremost, the book adequately exposes the reality of U.S. expansion. Although it may challenge the narrative you’ve been taught, it is important to acknowledge the sad truths behind American history. From its inception, America instituted a land grab without any consideration for the people already living there. Over the years, the systems in place, and the men who controlled them, stripped indigenous people of their land and culture while causing great suffering along the way. This is the legacy that we now live with.

I would also recommend The Relentless Business of Treaties because of its format and readability. Case organizes his argument both chronologically and by topic. He begins shortly after the American Revolution, leading readers forward through the treaty making period which began with John Marshall’s Doctrine of Discovery (1823) and ended when Congress cut off funding for future Indian treaties (1871). Case also makes clear the various interests that were involved in treaty making and U.S. expansion. This includes, as separated by chapter, the land speculators, fur traders, men of industry, political and personal boundaries, bureaucrats, and mythmakers. Essentially, Case is able to demonstrate that each of the men who signed treaties with indigenous nations had either ties to each other, ties to political and business interests, or both. At times, the examples provided by Case become monotonous, but this does not detract from the overall lessons of his research.

“In this mare’s nest of conflicting political interests—federal, settler, business—the only consistent theme was aggressive support for U.S. expansion.”

Finally, I would advise readers that, despite my glowing recommendations, The Relentless Business of Treaties should not be the only source that informs your awareness of these topics. I am skeptical of Case’s overall argument because it lacks nuance. It is undeniable that the system of treaty making with indigenous nations was fraught with greed and corruption, but Case’s evaluation lacks depth. It is a concise history of a broad topic that fails to consider the lives of the treaty signers within the context of their time and own personal histories. Also, Case states facts about the Dakota treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota that appear either untrue or unverifiable. I do not argue his conclusions, but I do believe a closer analysis is necessary.

“In creating history, many of these treaty signers were telling their own stories. And because they occupied prominent positions in society at large, and in the vanguard of aggressive U.S. expansion, their stories shaped the American myth and affected the way that American history has been told.”

The Relentless Business of Treaties by Martin Case, published by the Minnesota Historical Society, is an outstanding historical work that rightfully debunks the American Myth. Although narrow in its interpretation, its presentation is informative and readable and its conclusions are invaluable toward righting the wrongs upon which America was founded.

Buy The Relentless Business of Treaties at a discounted price in my online bookstore.

May 19, 2019

May 13, 2019

May 6, 2019

Lake Calhoun or Bde Maka Ska?

In recent weeks, there has been renewed discussion about the name of a popular lake in southwest Minneapolis. Known for many years as Lake Calhoun, the name was changed back to Bde Maka Ska as it was known by the Dakota people before American exploration and settlement. But, the Minnesota Court of Appeals determined that the Department of Natural Resources lacked the authority to change the name of the lake. The decision has raised controversy. Although many circumstances and perspectives contribute to the discussion and its eventual results, it is important and valuable to understand some of its historical context.

In 1805, shortly after the United States negotiated the Louisiana Purchase, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike led an exploratory expedition up the Mississippi River to scout out suitable sites for military and trading posts. Pike selected a site at the confluence of the St. Peter’s (Minnesota) and Mississippi rivers, a sacred area known as Bdote to the Dakota people. It would be many years before a fort was established at that location.

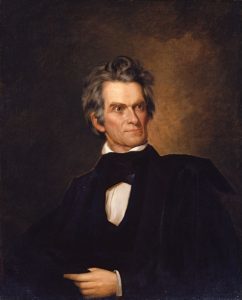

John C. Calhoun, Image from Wikipedia.org

John C. Calhoun, Image from Wikipedia.orgIn 1817, John Caldwell Calhoun was appointed Secretary of War under President James Monroe. Calhoun, in response to the War of 1812, immediately allocated resources for the exploration of the west in order to secure the area for American expansion. Calhoun launched what is now known as the Yellowstone Expedition which included numerous expeditions up the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. One such expedition was a scientific journey led by civil engineer Stephen H. Long. Long’s expedition was part of an imperialist strategy to use scientific exploration to inform military knowledge in order to secure the West. After arriving at the confluence of the St. Peter’s and Mississippi rivers in 1817, Long supported Pike’s opinion and recommended the site as a suitable location for a permanent fort.

In response to Long’s recommendation, Calhoun directed Lieutenant Colonel Henry Leavenworth, then rendezvoused at Detroit, to relocate to the confluence of the St. Peter’s and Mississippi rivers for the purpose of establishing a military post. The post was established in 1819 and named Fort St. Anthony. Upon encountering the chain of lakes to the west of the fort, Leavenworth named the largest lake, Lake Calhoun in honor of the Secretary of War who ordered the establishment of the nearby fort. The next largest lake, Lake Harriet, he named after his wife. Leavenworth was succeeded by Colonel Josiah Snelling in 1821. Snelling made sweeping changes and moved the fort to its current location. In 1824, General Winfield Scott renamed the fort, Fort Snelling in honor of its ambitious commander.

Lt. Colonel Henry Leavenworth named Lake Calhoun in honor of John C. Calhoun. Image from MNHS Collections.

Lt. Colonel Henry Leavenworth named Lake Calhoun in honor of John C. Calhoun. Image from MNHS Collections.Calhoun went on to become Vice President of the United States under presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Calhoun has been criticized as a staunch proponent of slavery which he considered a “positive good.” But, he is also celebrated for his numerous political achievements. In an address at Fort Snelling in 1905, one hundred years after the Pike Treaty, General James H. Baker stated, “Two generations have carped at Calhoun, subsequently the great apostle of human slavery; but at that hour he was our friend, and issued the momentous order which opened the doors of Minnesota to settlement and civilization.”

At the time Fort Snelling was established, the United States also established the St. Peters Indian Agency. The role of the agency, led by Indian Agent Lawrence Taliaferro, was to control trade in the region, resolve disputes, and maintain peace. Agencies, like the St. Peters, also adopted policies of acculturation and assimilation of Native communities. In order to administer such policies, Taliaferro encouraged agriculture among the Dakota people living near the fort. One Dakota leader who decided to try the agricultural experiment was Mahpiya Wicasta (Cloud Man, or Man-of-the-Sky). According to missionary Samuel Pond, Mahpiya Wicasta made his decision after a blizzard trapped him and his hunting party for three days. After surviving the storm, Mahpiya Wicasta persuaded some Dakota families to join him in establishing an agricultural colony of subsistence farming on the banks of Lake Calhoun.

Gideon and Samuel Pond established a mission at Bde Maka Ska in 1834. Image from MNHS Collections.

Gideon and Samuel Pond established a mission at Bde Maka Ska in 1834. Image from MNHS Collections.The lake was known to the Dakota by several names. Because of the lake’s white sandy shores, the Dakota called it Bde Maka Ska (White Banks Lake). According to Samuel Pond, who, along with his brother Gideon established a mission at the lake in 1834, the Dakota also called it “the inland lake” (Heyata Mde) because of its location away from the river. Lake Harriet they called, “the other lake” (Mde Unma). Bde Maka Ska has also been called Mde Medoza (Lake of the Loons) by the Dakota. While helping Samuel Pond select a spot for his new home, Mahpiya Wicasta suggested a location along the eastern shore because from that point “the loons would be visible in the lake.”

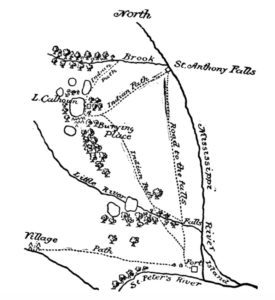

A map of the region near Bde Maka Ska drawn by Samuel or Gideon Pond in approximately 1835. Image found in “Two Volunteer Missionaries Among the Dakotas,” p. 46

A map of the region near Bde Maka Ska drawn by Samuel or Gideon Pond in approximately 1835. Image found in “Two Volunteer Missionaries Among the Dakotas,” p. 46Mahpiya Wicasta’s agricultural colony was established in August of 1829 and was called Heyate Otunwe (the village at the side). Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro, however, called the village Eatonville, in honor of John Eaton, secretary of war in the administration of President Andrew Jackson. The village was considered an experiment by the United States government to see how well the Dakota could adapt to a settled, agrarian way of life. The U.S. government provided the Dakota at Heyate Otunwe with farming implements such as plows and even hired a government farmer named Philander Prescott. For the Dakota, however, the village represented a diplomatic decision made in the best interests of their people. Mahpiya Wiscasta recognized that times were changing and he sought to ensure the survival of his people and culture. Though the village was abandoned in 1839, Mahpiya Wicasta and members of his community continued to practice methods of subsistence farming in addition to traditional ways of living.

As for the lake, it remained largely unpopulated until the latter half of the 19th century when resort hotels were built nearby. In 1886, the Minneapolis Park Board began acquiring land around the lake and in the 1910s and 20s the marshy shores were dredged and the chain of lakes were connected, creating what we know today as a series of parkways and beaches for recreation and enjoyment. By whatever name the lake is known, it is a beautiful place that should be preserved and appreciated, and understood within its historical context.

Sources:

Clyde Wilson, “John C. Calhoun and Slavery as a “Positive Good:” What He Said,” The Abbeville Institute, Posted June 26, 2014, Accessed May 6, 2019, https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/clyde-wilson-library/john-c-calhoun-and-slavery-as-a-positive-good-what-he-said/.

“DNR Taking Bde Mka Ska Name Fight to MN Supreme Court,” MPR News, Posted May 1, 2019, Accessed May 6, 2019, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2019/05/01/bde-maka-ska-lake-calhoun-dnr-appeals-court.

General James H. Baker, “Address at Fort Snelling in the Celebration of the Centennial Anniversary of the Treaty of Pike with the Sioux,” in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 12, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1908), 291-301.

Gwen Westerman and Bruce White, Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012).

James D. Miller, George J. Hudak, Chad Wittkop, and Patrick I. McLaughlin, editors, Archean to Anthropocene: Field Guides to the Geology of the Mid-Continent of North America, (Boulder: The Geological Society of American, Inc., 2011).

James P. Ronda, edited by William Deverell, “Passion and Imagination in the Exploration of the American West,” in A Companion to the American West, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 53-76.

Larry Millet, AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: The Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2007).

Reverend Samuel William Pond, “The Dakotas or Sioux in Minnesota as they were in 1834,” in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 12, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1908), 319-501.

Samuel William Pond, Two Volunteer Missionaries Among the Dakotas, (Boston and Chicago: Congregational Sunday School and Publishing Society, 1893).

“The US Indian Agency (1820-1853),” Minnesota Historical Society, Accessed May 6, 2019, http://www.mnhs.org/fortsnelling/learn/native-americans/us-indian-agency.

Warren Upham, “Minnesota Geographic Names: Their Origin and Historic Significance,” in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 17, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1920).

William H. Keating, Narrative of an Expedition to the Source of St. Peter’s River, Lake Winnepeek, Lake of the Woods, &c. &c., Vol. 1, (Philadelphia: H.C. Carey & I. Lea, 1824).

April 20, 2019

Independent Bookstore Day – April 27, 2019

Independent Bookstore Day is Saturday, April 27, 2019. Founded and run by the Northern California Independent Booksellers Association, Independent Bookstore Day is a national celebration of independent booksellers that takes place the last Saturday in April. Each store participates in its own way with prizes, discounts, and fun in-store events. Independent booksellers are local anchors that provide a place of gathering, learning, and community involvement. This annual celebration is a great way for patrons to support and show how much they appreciate their local booksellers.

Independent Bookstore Day is Saturday, April 27, 2019. Founded and run by the Northern California Independent Booksellers Association, Independent Bookstore Day is a national celebration of independent booksellers that takes place the last Saturday in April. Each store participates in its own way with prizes, discounts, and fun in-store events. Independent booksellers are local anchors that provide a place of gathering, learning, and community involvement. This annual celebration is a great way for patrons to support and show how much they appreciate their local booksellers.

This year, Rain Taxi is partnering with the Twin Cities Literary Calendar, along with 19 independent booksellers, to create the 2019 Twin Cities Independent Booksellers Passport. Pick up your passport at any participating locations and collect stamps to activate coupons and enter contests for a chance to win prizes. Learn more, along with a list of participating stores at RainTaxi.com.