Colin Mustful's Blog, page 16

April 16, 2019

How to do Historical Research

Including relevant historical resources and citations such as chapter notes, footnotes, bibliographies, and appendices, are one of the unique features of my novels. Although fiction does not usually include these elements, I believe it is important to allow readers the opportunity to become deeply engaged in my stories by investigating the history. I encourage my readers to evaluate the sources I use, filter fact from fiction, and determine for themselves what the history means. But, in order to do that, readers need to the tools to understand and become a part of the historical process. Below is a step-by-step guide to get you started.

Identify your topic – Start broad. Begin with an idea of what or who you are interested in researching. There is no need to narrow your topic until you have a basic understanding of the historical context.

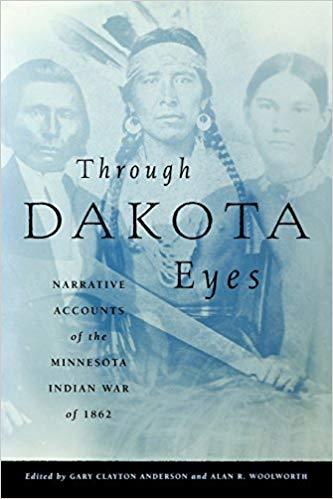

THROUGH DAKOTA EYES, edited by Gary Clayton Anderson, provides an excellent overview of the people and events of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.

THROUGH DAKOTA EYES, edited by Gary Clayton Anderson, provides an excellent overview of the people and events of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.Do some general reading – Once you’ve identified a broad topic, start reading texts that provide an overview of that topic. For instance, if you’re interested in the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, begin by reading books about the history of Minnesota in the 19th century. As you read, slowly begin to narrow your topic by then selecting books about the history of the U.S. – Dakota War. This might include books like Over the Earth I Come by Duane Schultz, Through Dakota Eyes by Gary Clayton Anderson or Being Dakota by Alanson Skinner and Amos Enos Oneroad.

Identify a specific/narrow topic – Once you’ve done some general reading, think about what caught your interest—what made you curious? That should become your topic.

Identify potential sources – Thanks to the historical process, historians always leave behind a trail of sources that begin with secondary sources and lead to primary sources. Use the bibliographies, footnotes, endnotes, and other resources found in books related to your topic in order to find sources that will help you learn more. For instance, if you’re reading the MNopedia article titled, Battle of Birch Coulee, in the bibliography you will find a source recorded like this: Christgau, John. Birch Coulie: The Epic Battle of the Dakota War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012. The article just led you to a new source that will lead you to even more sources.

Find your sources – In today’s digital age finding sources is easier than ever. Most sources are digitized, meaning you can find them with a computer and internet access. I recommend starting with Google Books (books.google.com), though there are many other digital platforms available. Search Google Books with all the information you have available such as book title, author name, and publication year. If you have a specific quote, use that. Put the quote in parentheses in the search bar and Google Books will take you directly to the source.

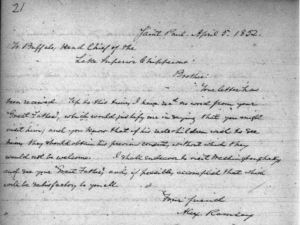

This is a letter written by Alexander Ramsey to Chief Buffalo of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. I discovered it in the endnotes of a secondary source, then located the microfilm copy at the Minnesota Historical Society, then scanned and digitalized the letter for my records.

This is a letter written by Alexander Ramsey to Chief Buffalo of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. I discovered it in the endnotes of a secondary source, then located the microfilm copy at the Minnesota Historical Society, then scanned and digitalized the letter for my records.For those sources that you cannot find on Google Books, try Worldcat.org. Worldcat searches all libraries throughout the world for your source. Use the search features to narrow your search. Sometimes, Worldcat will direct you to an electronic source other than Google Books. That’s great! Sometimes, you can only find the source in print or microfilm at a local or regional library or museum. That’s okay, too.

Gather as many sources as possible – It’s not enough to look at one or two sources if you wish to truly understand your topic. Historians will often use hundreds of sources when writing books or essays. Whatever sources you use, be sure that you consider multiple perspectives. That means you must evaluate your topic from the viewpoint of all people involved and then find sources from those people. For instance, when researching the U.S. – Dakota War, it’s important to find sources and viewpoints from numerous parties involved such as the white settlers, the traditional Dakota, the farmer Dakota, the missionaries, the government appointed agents, the traders, the Dakota of mixed racial heritage, the people held captive, the volunteer militia, and so forth. Each person and group of people will have a different viewpoint of what happened and why. As a historian, it’s important to acknowledge and understand each viewpoint in order to fully comprehend your topic.

Furthermore, when considering sources, be aware of the author and date of publication. Choose sources that were written during the event, after the event, and during contemporary or more recent times. Also, be sure to use a variety of authors who reflect a diversity of opinion and backgrounds.

A page out of my notebook. Notes on the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

A page out of my notebook. Notes on the Sandy Lake Tragedy.Take notes – As you read your sources, take notes. Write down anything that interests you. Write down anything that strikes or startles you. Write down anything that seems important or relevant.

This is the bibliography from my novel, RESISTING REMOVAL. Notice that the sources are similar in format and they include all of the information you need to find and use those sources.

This is the bibliography from my novel, RESISTING REMOVAL. Notice that the sources are similar in format and they include all of the information you need to find and use those sources.Make it your own – You’ve identified your topic, read through a variety of sources, and taken pages and pages of notes. Now it’s time to draw your conclusions. What do you think happened and why? You are now the expert. Using your notes, turn your thoughts into a readable narrative. Begin by summarizing your findings and expressing the historical context of your topic. Then, using evidence, build a narrative or argument to support the conclusions you’ve made about your topic. Tell readers what happened and tell them, based on your careful research, why it happened. Or, if you’re unable to draw any specific conclusions, pose new questions for future researchers. Ultimately, remember that this is your narrative and you should make it your own rather than repeating what’s already been said. By doing this, you are adding to the historiography so that others may use your work as their source.

Cite your sources – This is important. Cite your sources by including the title, author, publisher, date of publication, and any other relevant information from the sources you used. This will help historians track down and verify your sources. This way, you are building a map for future researchers that will help them delve into the historical event or person the same way you did. As more historians research a topic, history becomes revealed which builds upon our understanding of the past and leads to a more enlightened future.

For those looking for broad range of history on the U.S. – Dakota War, download my Kindle ebook, Confronting Minnesota’s Past: A Resource to Test Your Understanding on the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. This comprehensive resource includes historically relevant information about the war, the people and places involved, and its context. An easy-to-read guide, Confronting Minnesota’s Past introduces readers to this important and tragic history through a variety of headings, quotes, discussion questions, and citations for further research.

For those looking for broad range of history on the U.S. – Dakota War, download my Kindle ebook, Confronting Minnesota’s Past: A Resource to Test Your Understanding on the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. This comprehensive resource includes historically relevant information about the war, the people and places involved, and its context. An easy-to-read guide, Confronting Minnesota’s Past introduces readers to this important and tragic history through a variety of headings, quotes, discussion questions, and citations for further research.

April 7, 2019

March 31, 2019

Pictures from AWP 2019

Once a year the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) hosts the AWP Conference & Bookfair. This years conference took place March 27 – March 30 at the Oregon Convention Center in Portland, Oregon. With more than 12,000 attendees, 2,000 presenters, and 550 readings, panels, and craft lectures, the AWP Conference & Bookfair boasts that it is the largest literary conference in North America. As a student of Augsburg University, I was proud to represent Howling Bird Press at the conference. I also enjoyed Portland for its abundance of recreation and scenic beauty. Below are some photographs from my trip.

Staffing the table.

Staffing the table. A view of the city.

A view of the city. A well-attended panel.

A well-attended panel. Cherry blossoms near the lift bridge.

Cherry blossoms near the lift bridge. MFA faculty member Karen Babine signing copies of her new book, All the Wild Hungers.

MFA faculty member Karen Babine signing copies of her new book, All the Wild Hungers. Joining a group trail runners.

Joining a group trail runners. With publishing mentor Jim and student editor Sharon.

With publishing mentor Jim and student editor Sharon. Alum Michael Ferraro keeping an eye on the candy.

Alum Michael Ferraro keeping an eye on the candy. Cherry blossoms through the sun.

Cherry blossoms through the sun. Forest Park in northwest Portland.

Forest Park in northwest Portland. Morning fog lifting.

Morning fog lifting. Running up the trail.

Running up the trail. A look at the bookfair.

A look at the bookfair.

March 15, 2019

The “Moscow Expedition”

“The whole operation is likely to prove a pretty expensive and a very difficult one, and to say the least, it was a great mistake on the part of the Government not to have attended to the matter before.” St. Paul Press, October 18, 1863, “A Moscow Campaign”

Following their forced exile from Minnesota, more than three thousand Dakota and Ho-Chunk people arrived at Crow Creek, South Dakota—their new reservation. The land was dry and inhospitable and could not support agriculture. Furthermore, the semi-arid terrain was not conducive the traditional lifeways of the Native peoples which depended on woodland lakes, rivers, and streams. Right away, food was in short supply and had to be rationed. Less than two months after their arrival, seventy Dakota people had died from want of food and medical care. According to the missionary John P. Williamson, “For six weeks after they arrived at Crow Creek they died at the average rate of three or four a day” (Hyman, 153).

The man assigned to oversee the removal and resettling of the Dakota and Ho-Chunk was the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Superintendency, Clark W. Thompson. A Republican appointed to the position in 1861 as a reward for his political loyalty to Morton Wilkinson, throughout his tenure Thompson showed little concern for the condition of Native populations. Rather, Thompson, who was a presidential elector, banker, and railroad speculator, used his position to support his political and business interests. As described by historian Mary Lethert Wingerd, Thompson was “a hard-drinking opportunist” who “used his position exclusively to enrich himself and his senatorial patron at Indian expense” (Wingerd, 293).

Unfortunately, this was not unusual in the United States Indian System at the time which was marked by corruption and fraud. As the Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thompson often faced pressures from political and business allies to overlook discretions or to assign contracts as a favor. In a letter to Thompson in early 1862, Dakota agent Thomas Galbraith actually urged Thompson to help him perpetuate a “little fraud” regarding a $52,000 claim for reimbursement (Green, 49). Meanwhile, the Ojibwe agent Lucius C. Walker “enthusiastically partnered with Thompson, falsifying annuity rolls, stealing Ojibwe goods and then reselling them to the Indians, and colluding with dishonest traders” (Wingerd, 293-294). When selecting the Crow Creek reservation, historian William E. Lass argues that Thompson was not totally to blame because Secretary of the Interior, John P. Usher, and Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William P. Dole, “had restricted Thompson severely in his selection area” (Lass, 228).

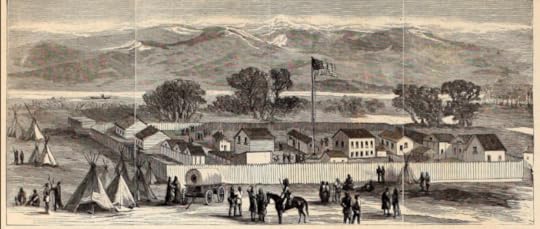

An image of Fort Thompson from Harper’s Weekly, October 28, 1865

An image of Fort Thompson from Harper’s Weekly, October 28, 1865Whether influenced by political and business cohorts or not, the conduct of Clark W. Thompson during his tenure as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Northern Superintendency was detrimental to Native populations—conduct which was amplified by his role in the “Moscow Expedition” of 1863. Because Thompson intended the Dakota and Ho-Chunk to quickly take up farming, he provided them with meager supplies at Crow Creek, also known as Fort Thompson. Throughout the summer of 1863, little was done to alleviate the condition of the Native peoples at Crow Creek which was exacerbated by a harsh drought. In fact, their condition was largely ignored by their agent St. Andre Durand Balcombe who was absent from the agency for weeks at a time. It was not until September 15 that Superintendent Thompson reported to acting commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles E. Mix, that no provision had been made “for the subsistence of the Winnebago and Sioux . . . after the first day of October next” (Lass, 230).

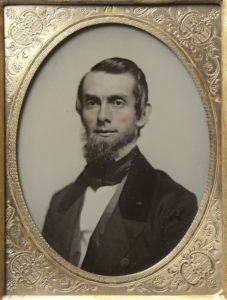

Indian Agent St. Andre D. Balcombe was absent from Crow Creek during much of the summer of 1863. Image from MNHS Collections

Indian Agent St. Andre D. Balcombe was absent from Crow Creek during much of the summer of 1863. Image from MNHS CollectionsSeeing this situation as an opportunity, Thompson devised a plan that would provide much needed supplies for the Dakota and Ho-Chunk while also benefiting himself and his business partners. Because of the summer drought, it would have been difficult to send supplies up the Missouri River from St. Louis or Sioux City, as would have normally been the case. With that in mind, Thompson suggested sending the supplies overland from Mankato, a distance of 292 miles. This plan would provide government contracts that would benefit local businesses including Thompson’s brother and his close friend, James B. Hubbell, a trader at Mankato.

Some newspapers at the time touted the idea. On October 2, 1863, the Mankato Weekly Union reported that such a route between Mankato and the Indian Agency would “work greatly to the advantage of the people in this vicinity” while arguing that “it will furnish a ready market at our door, for from $100,000 to $150,000, worth of provisions, annually, and the people will receive the profit . . .” Other newspapers, however, considered the idea a mistake, leading one reporter from the the St. Paul Press to liken it to Napoleon’s failed Moscow Campaign. In his report of October 18, 1863, and titled “A Moscow Campaign,” the reported declared that, “The whole operation is likely to prove a pretty expensive and a very difficult one, and to say the least, it was a great mistake on the part of the Government not to have attended to the matter before.” This led other newspapers to begin calling the plan “The Moscow Expedition.” They argued that it was too late in the season for such an expedition and that it would result in material losses.

Nevertheless, the plan moved forward quickly. Without competitive bidding, Thompson awarded Hubbell with a contract to supply five hundred head of cattle. Then, after advertising the transportation contract for just one day, Thompson awarded the transportation contract to J.C. & H.C. Burbank and Company. Finally, because of the recent military skirmishes in Dakota Territory, Thompson requested a military escort to go along with his huge supply train. The acting general, John Pope, questioned why the supplies had not been shipped from somewhere along the Missouri such as Sioux City, but because he did not want the military to seem unsympathetic to the starving peoples at Crow Creek, he readily assigned a military escort.

Along with the beef cattle, Thompson was to supply Crow Creek with pork and flour. In order to do this, Thompson sought to use the pork and flour that had been left behind at the Ho-Chunk Agency when the Ho-Chunk were forcibly exiled. According to their former agent, C.G. Wyckoff, who inspected the barrels, only a small portion was safe for consumption. Thompson, however, told Wyckoff to put the barrels up for auction and when they were not sold, Thompson bought the condemned pork and flour because he considered it unfit for soldier’s consumption, “but good enough for hungry Indians” (Folwell, 440).

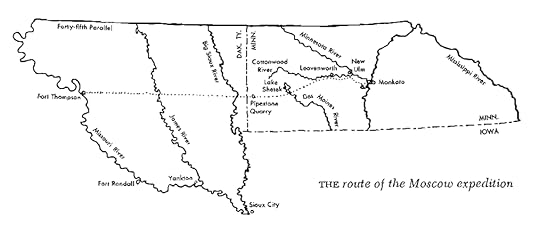

Map from “The Moscow Expedition” by William E. Lass, Minnesota History, Summer 1965.

Map from “The Moscow Expedition” by William E. Lass, Minnesota History, Summer 1965.The expedition assembled at Lake Crystal, Minnesota, with the last of the wagons departing from there on November 12, 1863. The wagon train extended one and a half miles and included 153 wagons—each with two yoke of oxen—2,500 to 3,000 pounds of goods, three companies of infantry totally 175 men, a detachment of nine men with a small howitzer, and twenty-five wagon loads of supplies and three ambulances (Lass, 235).

The wagon train reassembled at Leavenworth, Minnesota, about forty miles west of Mankato, where it encountered numerous problems. Because the expedition was short on teamsters, many of the soldiers were asked to drive the wagons. However, the soldiers were disgruntled and made several attempts to sabotage the expedition by removing the axeltree nuts of the wagons. Under the conditions, the expedition could not proceed until Colonel William Crooks was called in. Crooks established order by arresting the key troublemakers, calling for a night watch on the wagons, and increasing the pay for soldiers who drove the wagons.

With the expedition able to continue, it traveled another 252 miles “without seeing anyone outside the party” (Lass, 237). On November 26, they encountered a blizzard but avoided any other setbacks, arriving at Crow Creek on December 2, 1863. Upon their arrival, Thompson found the agency in a desperate situation. Hundreds of Ho-Chunk had fled south to other reservations while many of the Dakota were threatening to leave for the Yankton Agency. Unfortunately, for the Native peoples at Crow Creek, the arrival of the expedition provided minimal relief. As noted by missionary John P. Williamson, most of the supplies that reached the reservation were consigned either to the traders or to the military (Lass, 238). As for the cattle, several had died along the way while the rest were “fatigued, lean, and starving” (Lass, 239).

Like they had been before, the supplies given to the people at Crow Creek were rationed, much of which were unsuitable for consumption. In order to work around that problem, officials at Crow Creek built a wooden barrel out of cottonwood and connected it by a pipe to the boiler from the saw mill. Inside the barrel, officials put beef, pork, flour and water. It also included things like beef heads, entrails, hearts, and lungs. The barrel was heated from the steam produced by the boiler and the soup, which had the composition of a thin gruel, was fed to the hungry Dakota and Ho-Chunk. According to Dakota leader Passing-Hail, reservation officials, “built a box and put the beef in it and steamed it and made soup; they put salt and pepper in it, and that is the reason these hills about here are filled with children’s graves; it seemed as though they wanted to kill us” (Hyman, 148).

According to Dakota leader Passing-Hail, reservation officials, “built a box and put the beef in it and steamed it and made soup; they put salt and pepper in it, and that is the reason these hills about here are filled with children’s graves; it seemed as though they wanted to kill us” (Hyman, 148).

The reservation at Crow Creek caused much suffering and death among the Dakota and Ho-Chunk peoples who were forced to resettle there after the U.S. – Dakota War. While the Dakota and Ho-Chunk were at Crow Creek, officials and businessmen such as Clark W. Thompson continued to use the the Native peoples for personal gain as exemplified by the “Moscow Expedition.” According to editor of the Mankato Record, John C. Wise, as summarized by historian William E. Lass, Minnesota had benefited greatly by the removal of the Sioux and Winnebago and the Moscow Expedition seemed “a final desperate attempt of Senator Wilkinson and his associates to exploit the Indians” (Lass, 234). Thompson, for his part, moved on from this tragedy as a successful businessman and politician. Thompson established the Southern Minnesota railroad from the Mississippi River to Winnebago City, he was a member of Minnesota’s constitutional convention, he became a state senator, and he was president of the State Agricultural Society. Now, his actions, and the actions of those like him, who exploited Native populations for personal gain, should be interrogated and discussed.

Sources:

William E. Lass, “The “Moscow Expedition”,” Minnesota History, 39:6 (Summer, 1965); 227–240.

Colette Hyman, “Survival at Crow Creek, 1863–1866,” Minnesota History, 61:4 (Winter 2008–2009); 148–161.

William D. Green, The Children of Lincoln: White Paternalism and the Limits of Black Opportunity in Minnesota 1860–1876, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Warren Upham and Rose Barteau Dunlap, “Clark W. Thompson” in “Minnesota Biographies 1655–1912,” Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 14, (St. Paul: Published by the Society, 1912).

William Watts Folwell, “The Moscow Expedition” in A History of Minnesota, Vol. 2, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1924).

For various newspaper accounts read: Mankato Record October 3, 10, 17, 24; Mankato Union October 2, 30, November 6; St. Paul Pioneer November 22, December 30; St. Paul Press October 18, 28, 1863.

February 12, 2019

Resisting Removal: Julius Austrian

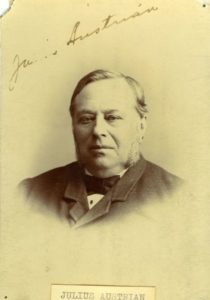

At the time of the Sandy Lake Tragedy, the La Pointe delegation to Washington in 1852, and the La Pointe Treaty of 1854, Julius Austrian was one of the most prominent and influential residents of La Pointe. Austrian, whose name was originally Oesterreicher, was a Bavarian Jew born in Germany in 1821. In 1844, he immigrated to America, to join his brother-in-law Lewis Leopold in business at Mackinac. A few years later, he moved to La Pointe where he operated a fur trading post and general store. Austrian also became engaged in the fish business, furnishing nets and salt and barrels to the fishermen.

By 1860, Julius Austrian owned 4,000 acres of land on Madeline Island. Image from the historical blog Chequamegon History and attributed to the Madeline Island Museum, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

By 1860, Julius Austrian owned 4,000 acres of land on Madeline Island. Image from the historical blog Chequamegon History and attributed to the Madeline Island Museum, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....While living at La Pointe, Austrian quickly earned a reputation for honesty and generosity. He was also known for his large and colorful garden which was described as being laid out most tastily with a large variety of fruit trees, apples, plums, cherries, as well as large quantities of currants and strawberries. His store and warehouse quickly became the center of La Pointe business dealings including an important 1851 council between the Ojibwe chiefs and elders and the Indian agent John Watrous.

Austrian took advantage of his success and in 1853, he bought up all land and property on Madeline Island that was previously owned by the American Fur Company. Then, in 1854, he was the unnamed and de facto host of the 1854 treaty. A year later, he officially hosted the 1855 payment at La Pointe. In 1856, Austrian helped name and plat the town of Bayfield, Wisconsin, just across the bay from La Pointe. By 1860, Austrian owned 4,000 acres on Madeline Island and he operated a cooperage which annually turned out 600 barrels for fish and he owned the island’s inn.

But, in obtaining land and wealth, Julius Austrian has been accused of fraudulent dealings. In particular, in his role as Postmaster of La Pointe he was said to obtain signatures illegally “by which he accomplished his selfish ends.” Also, as stated by the historical blog Chequamegon History, “Julius Austrian succeeded in securing several thousand acres of Chippewa Mixed-Blood Allotments along the Penokee Iron Range, for his benefit, not the Tribe’s.” Ultimately, whether through proper channels or fraudulent dealings, Austrian was a powerful landowner at La Pointe who made a name for himself through numerous ventures and carried great influence at a time of change and controversy.

Learn more about Julius Austrian and his families relationship to the Chequamegon region.

Sources:

Amorin Mello, “Austrian Papers,” Chequamegon History (blog), Accessed June 28, 2018, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

—————, “Penokee Mixed-Blood Allotments Shakedown Scam of 1858,” Chequamegon History (blog), Published April 21, 2018, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

John O. Holzhueter, Madeline Island and the Chequamegon Region, (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 1974).

“Jewish Museum of the American West, Julius Austrian, Early Jewish Pioneer Merchant of Northern Minnesota & Wisconsin,” Jewish Museum of the American West, Published February 8, 2016, http://www.jmaw.org/austrian-jewish-m....

February 5, 2019

Resisting Removal: The 1854 Treaty of La Pointe

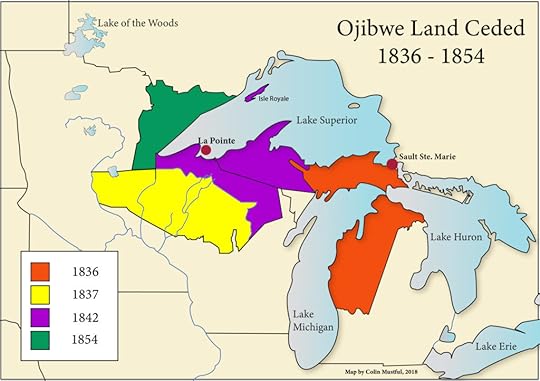

On September 30, 1854, eighty-five leaders of the Lake Superior Ojibwe signed a treaty ceding their lands along the northern and western shores of Lake Superior in exchange for annual payments, goods and services, and permanent reservations near their homes. The treaty was signed in the aftermath of the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the removal efforts of the early 1850s.

Lands ceded by the Ojibwe, 1836–1854.

Lands ceded by the Ojibwe, 1836–1854.In the late 1840s and early 1850s, the Lake Superior Ojibwe argued for permanent homes within the so-called “ceded territory” of northern Wisconsin and Michigan. This included trips to Washington DC in 1849 and 1852. During this time, the Ojibwe were told that they had to move west into the “unceded territory” of northern Minnesota. But, the Ojibwe wished to remain living on their homeland just as they had been promised they could during the La Pointe Treaty of 1842.

After a series of failed removal efforts by the U.S. government, it was finally determined that a new treaty be made. In September, 1854, thousands of Ojibwe from the Lake Superior and Upper Mississippi bands along with Indian traders gathered at La Pointe to negotiate a new treaty. The U.S. government, led by Indian agent Henry Gilbert and Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny, wished to acquire the copper and timber resources of the region and to concentrate the Ojibwe on reservations for the purpose of assimilation. The Ojibwe, led by Chief Buffalo and interpreter Benjamin Armstrong, wished to secure permanent homes, annual cash payments, and the right to hunt, fish, and gather within the ceded territory.

After much negotiation that included a split between the Lake Superior and Upper Mississippi bands, and a show of objection from the traders, an agreement was reached. The final treaty ceded almost all remaining land held by the Lake Superior Ojibwe, but it also secured permanent reservations for the numerous bands such as those at Grand Portage, Fond du Lac, and La Pointe. Furthermore, included a stipulation that annuity payments would thereafter be made near their homes, rather than forcing the Ojibwe to travel to Minnesota Territory as they had previously done. The reservations created by the treaty remain home for the Lake Superior Ojibwe who still hold many of the original treaty rights to hunt, fish, and use the land.

Sources:

Armstrong, Benjamin Green. Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences From the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong. Dictated to and Written by Thomas P. Wentworth. Ashland, Wisconsin: A.W. Bowron, 1892.

Stone, Andrew. “Treaty of La Pointe, 1854.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/treaty-... (accessed June 3, 2018).

January 29, 2019

Resisting Removal: Willis Gorman and Henry Gilbert

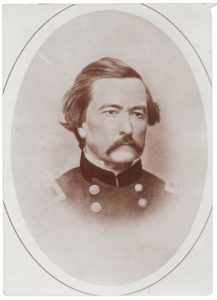

Minnesota Territorial Governor Willis A. Gorman reversed the Ojibwe removal policies of his predecessor Alexander Ramsey. Portrait from the MNHS Collections, 1861.

Minnesota Territorial Governor Willis A. Gorman reversed the Ojibwe removal policies of his predecessor Alexander Ramsey. Portrait from the MNHS Collections, 1861.In March 1853, Democrat Franklin Pierce replaced Whig Millard Fillmore as President of the United States. This led to the removal from office of Alexander Ramsey and John Watrous. Willis Gorman replaced Ramsey as Minnesota’s Territorial Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs while Henry Gilbert replaced Watrous as Indian Agent assigned to the Lake Superior Ojibwe.

Immediately upon taking office, Gorman and Gilbert recognized the poor and ineffective condition of Indian policy and politics among the Ojibwe of Minnesota and Wisconsin. This condition was a direct result of the failed removal efforts of the previous administration. Therefore, Gorman put an immediate and effective end to the Removal Order of 1850 and all its attendant policies. For this reason, Gorman ordered the annuity payment as early in the year as possible to avoid causing the Ojibwe to travel during winter, a circumstance that led to the death of many Ojibwe in previous years.

In 1853, Agent Gilbert arrived at La Pointe to make payment on October 9 much to the surprise of the Ojibwe who were overjoyed at the change in policy. After meeting with the chiefs and elders Gilbert called the previous years removal efforts “the great terror of their lives” and said the Lake Superior Ojibwe “would as soon submit to extermination than to comply with it.” Commenting on their condition, Gilbert said that he found many Ojibwe “reduced to the very extreme of want and poverty” (White, The Removal Context, 267).

Gorman also recognized the poor condition of the Ojibwe throughout the region. After being visited by a delegation of St. Croix Ojibwe, Gorman paid $550 out of his own pocket for goods to be provided them. As Gorman stated in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs explaining his actions, “They present such a squalid appearance I took pity on them” (White, The Removal Context, 269). As Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Gorman participated in the Congressional investigation against his predecessor, Alexander Ramsey. After his review of Ramsey’s conduct Gorman wrote, “there is or has been more fraud and cheating in the Indian trade in this Territory than it has been my lot to see or know of anywhere else on this earth” (White, The Removal Context, 273).

Gorman and Gilbert worked hard and faced some opposition while they reversed the failed removal policies of Ramsey and Watrous. By 1854, they arranged for a new treaty that officially put down on paper the end of removal efforts and provided permanent homes for the Ojibwe upon their homeland. However, they also instituted a new policy of concentration and assimilation.

Read more about Willis A. Gorman on the website The Minnesota Territorial Pioneers.

Sources:

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

January 22, 2019

Resisting Removal: Ma’iingan – The Brother Wolf

Among their many beliefs within the creation story, traditional Ojibwe spirituality tells of a unique relationship between Ma’iingan (the wolf) and humankind. The creator, known as Kitche Manitou, made the wolf to walk alongside the Anishinabe (Original People) as their brothers and teachers. The Ma’iingan are recognized as educators of the Anishinabe who teach hunting and working together as a family unit. As closely related brothers, both the Anishinabe and Ma’iingan have extensive clan systems, both mate for life and raise their young in a family environment, and both have shared a similar fate – both have lost lands and been mistreated and misunderstood.

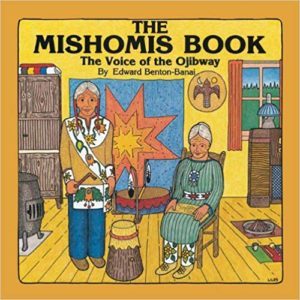

The story of Ma’iingan is told in The Mishomis Book by Edward Benton-Banai:

The Mishomis Book provides this history, philosophy, and teachings of the Ojibwe people as passed down through oral tradition. Published by University of Minnesota Press, https://www.amazon.com/Mishomis-Book-....

The Mishomis Book provides this history, philosophy, and teachings of the Ojibwe people as passed down through oral tradition. Published by University of Minnesota Press, https://www.amazon.com/Mishomis-Book-....Anishinabe and Ma’iingan walked the Earth and came to know all of her. In this journey they became very close to each other. They became like Brothers. In their closeness they realized that they were Brothers to all Creation.[image error]

The Creator said, “You are to separate your paths. You must go different ways. What shall happen to the one of you will also happen to the other. Each of you will be feared, respected and misunderstood by the people that will later join you on the Earth.”

Read the White Earth Wolf Proclamation from 2012.

Sources:

Edward Benton-Banai, The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

“Ma’iingan (the Wolf) Our Brother,” White Earth Land Recovery Project, Published December 22, 2012, http://welrp.org/maiingan-the-wolf-ou....

January 15, 2019

Resisting Removal: George Manypenny

The three government officials most involved in the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850 were the Commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs Alexander Ramsey, and the Indian Sub-Agent John Watrous. Together, Lea, Ramsey, and Watrous, promoted a policy of removal, forcing the Ojibwe from ceded lands in Wisconsin and Michigan to unceded lands in Minnesota Territory. In 1853, these officials were replaced when a new political administration appointed new officials. The new appointees were Henry Gilbert as Indian Agent, Willis Gorman as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and George Manypenny as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

George W. Manypenny ended all removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe, but he ushered in a new era of assimilation policies. Image from Wikipedia.

George W. Manypenny ended all removal efforts of the Lake Superior Ojibwe, but he ushered in a new era of assimilation policies. Image from Wikipedia.The change in administration also represented a change in policy. Rather than promote removal, the new policy promoted concentration and assimilation. At the time, this was seen as favorable by the Ojibwe living in the ceded territory because it ended removal efforts and provided permanent homes within their homeland. However, it could also be viewed as another way to control and eradicate Native peoples and culture.

At the head of the new Indian policy was Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny. Manypenny believed that the Indians should be concentrated on reservations within their homelands and there made to learn the ways of “civilized life” which included farming, ownership of private property, Christianity, and the speaking of the English language. In the making of treaties, Manypenny was very businesslike and showed little knowledge or appreciation of Native people or culture. When negotiating a treaty with the Ojibwe in 1855, Manypenny showed a “shocking insensitivity” toward the Ojibwe and “displayed not the slightest understanding for, or appreciation of, Indian culture” (Cleland, Preliminary Report, 90).

Later in life, Manypenny wrote a book about his views on Indians policy titled, “Our Indian Wards.” In it, Manypenny expressed the belief that the Indians should be given “such aid, instruction, and sympathy as will win them from their wild life, and induce them to accept the comforts of civilization and a settled home” (Manypenny, “Our Indian Wards,” xxvi). Manypenny admitted that removal was detrimental to the Indians, but he only did so to further promote his policy of assimilation.

In 1854, though the Ojibwe were relieved and anxious to sign a treaty ending removal efforts and promising permanent homes, it did little to improve their position or condition. Rather, it represented a change in policy championed by the new Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny who, as argued by historian Leo Filipczak, “despised Indian culture.” Rather than remove the Ojibwe, the new policy in 1854 was to concentrate and assimilate them.

Read Our Indian Wards by George Manypenny.

Sources:

Charles E. Cleland, “Preliminary Report of the Ethnohistorical Basis of the Hunting, Fishing, and Gathering Rights of the Mille Lacs Chippewa,” Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 1–140.

Chequamegon History (blog), “Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment,” Published January 20, 2014, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

January 8, 2019

Resisting Removal: Interest of the Traders

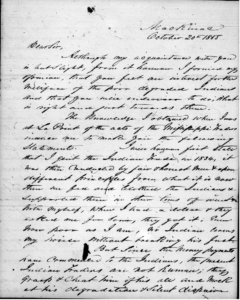

Letter by William Johnston to George Manypenny, October 20, 1855. MNHS Manuscript Collections.

Letter by William Johnston to George Manypenny, October 20, 1855. MNHS Manuscript Collections.In October 1855, trader and government interpreter William Johnston wrote a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, George Manypenny in which he stated, “Since the money payments have commenced to the Indians, the present Indian traders are not human; they grasp and cheat him of his all and mock at his degradation and silent despair.” Johnston went on to name the traders Charles Borup, Charles Oakes, Clement Beaulieu, and George Nettleton among those who took advantage of the Indian annuities. He also accused Indian Agent John Watrous of exploiting the system illegally for his own personal profit (Johnston to Manypenny, October 20, 1855).

These same traders took full advantage of the dire circumstances of the Ojibwe during the Sandy Lake Tragedy. When agent John Watrous arrived at Sandy Lake in November 1850, he found that dozens of Ojibwe had died from spoiled rations and more were dying daily. Also, Watrous had no money to make the promised annuity payment. Seeking help, Watrous asked the traders to supply the Ojibwe with food and supplies. The traders, seeing their advantage, greatly inflated their prices. According to Watrous, he “negotiated the most reasonable terms possible” to supply the Ojibwe, but still the prices were three to six times higher than normal (Clifton, Wisconsin Death March, 25). This greatly indebted the Ojibwe to the traders.

A few years later, during the 1854 treaty and 1855 payment that followed, the traders sought to further exploit the Ojibwe through threats of violence and manipulation. According to interpreter Benjamin Armstrong, the traders put up much opposition during the 1854 treaty negotiations and he wrote that they “were at the council heavily armed for the purpose of enforcing their claim by intimidation” (Armstrong, Early Life, 42). When the time came to pay the claims, William Johnston reported that the traders, “in Midnight counseled with the chiefs of La Pointe . . . [and] induced them to sign a stipulation, giving them the whole of the $90,000 provided by treaty for the payment of debts.”

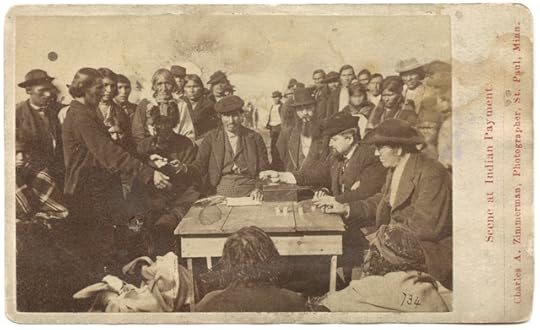

Scene at Indian Payment likely photographed at Odanah around the year 1870. MNHS Collections.

Scene at Indian Payment likely photographed at Odanah around the year 1870. MNHS Collections.

Many Ojibwe objected to paying the traders directly out of annuities, because it went against the wording of the treaty and failed to allow for a review of the claims. In a speech to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and those gathered for the 1855 payment, the Ojibwe leader Blackbird said, “Now I will tell you how it is with our traders. When they first came among us they were very poor, but by and by they became very fat and rich, and wear rich clothing and had their watches and gold chains such as I see you wear. But they got their things out of us. They were made rich at our expense” (Chequamegon History, “Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment).

Read Blackbird’s speech at the 1855 payment.

Sources:

Chequamegon History (blog), “Blackbird’s Speech at the 1855 Payment,” Published January 20, 2014, https://chequamegonhistory.wordpress.....

James A. Clifton, “Wisconsin Death March: Explaining the Extremes in Old Northwest Indian Removal,” in Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, Vol. 75, (1987): 1–40.

Bruce White, “The Regional Context of the Removal Order of 1850,” in Fish in the Lakes, Wild Rice, and Game in Abundance: Testimony on Behalf of Mille Lacs Ojibwe Hunting and Fishing Rights,” Compiled by James M. McClurken, (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2000), 141–328.

William Johnston to George W. Manypenny, October 20, 1855, Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824–1880, Mackinac Agency, Minnesota Historical Society, Manuscript Collections, M175, R404.

Benjamin Green Armstrong, Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences From the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong, Dictated to and Written by Thomas P. Wentworth, (Ashland, Wisconsin: A.W. Bowron, 1892).