Colin Mustful's Blog, page 10

December 26, 2020

The Largest Mass Execution in U.S. History: A timeline to understand how Abraham Lincoln ordered the execution of 38 Dakota men

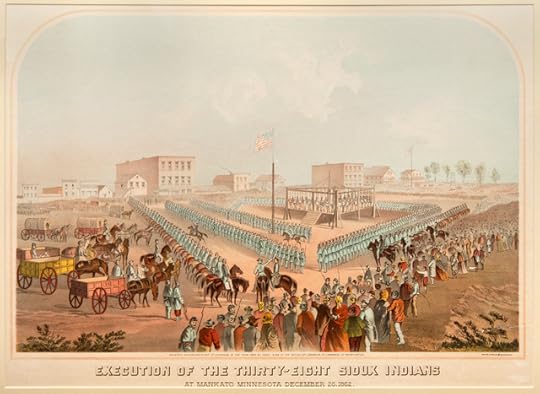

On December 26, 1862, 158 years ago today, thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in what remains the largest mass execution in United States history. The hangings were ordered by President Abraham Lincoln in response to a series of battles between U.S. and Dakota forces commonly known as the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. The war began on August 18, 1862, when several hundred Dakota soldiers attacked the people living at the Lower Sioux Agency. After several attempts to overrun the defenses at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm, the Dakota retreated along with their captives and were eventually defeated by U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry Hasting Sibley at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. It should be noted that the war and its results were a part of a much broader context of mismanagement and mistreatment of the U.S. government toward Native peoples.

A framed color lithograph hanging in Mankato, December 26, 1862. MNHS Collections.

A framed color lithograph hanging in Mankato, December 26, 1862. MNHS Collections. This post presents a timeline of events between the Dakota defeat at The Battle of Wood Lake and the hangings on December 26. It is meant to give readers a clearer view of those things that transpired prior to the tragic mass execution that has left an indelible stamp on Minnesota’s history. While the military trials that followed the U.S. – Dakota War were highly questionable for the manner in which they were conducted, this timeline is meant to present the facts as they are known without considering the moral, ethical, or legal implications.

The information conveyed here has been collected largely from the important and valuable scholarship of John Haymond and Walt Bachman. Any mistakes in the historical accuracy of the timeline are my own.

Read more about the mass hanging on December 26, 1862

September 23

The Dakota are defeated by U.S. forces at The Battle of Wood Lake.

September 23

Following their defeat, the Dakota are split between those who flee toward the western plains and those who remain to protect the captives and surrender to U.S. forces.

September 26

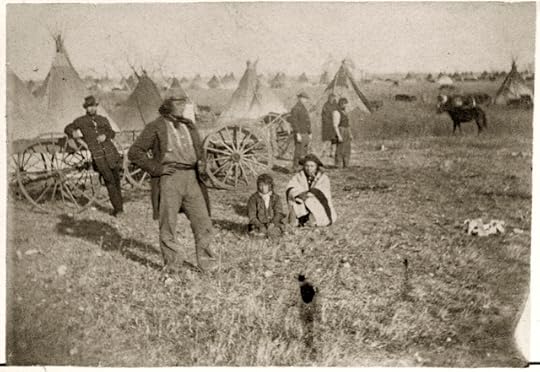

U.S. forced led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley the Dakota camp and take the captives safely into custody. The new encampment is named Camp Release.

A photograph taken at Camp Release, 1862. MNHS Collections.

A photograph taken at Camp Release, 1862. MNHS Collections.September 27

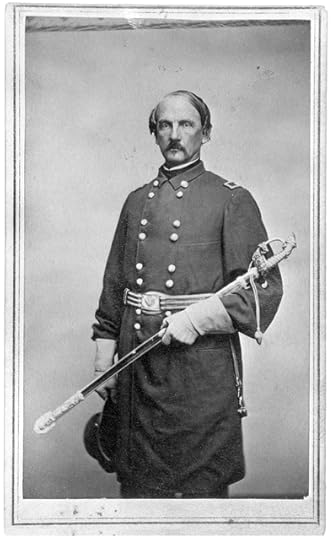

Colonel Henry Sibley issues an order to establish a three-man military commission consisting of Colonel William Crooks, Lieutenant-Colonel William Marshall, and Captain Hiram Grant. Missionary Stephen R. Riggs is appointed as deposer of witnesses and translator and Isaac V.D. Heard is appointed Recorder of the Commission.

September 27 and 28

16 Dakota men are arrested.

September 28

Sibley issues instructions that no one is allowed to depart the camp without a special permit from the commander.

September 28

In Order No. 55, Sibley expands the military commission adding Lieutenant Rollin C. Olin as Judge Advocate and Captain Hiram S. Bailey.

September 28

In a letter to Major General John Pope, Commander of the Military Department of the Northwest, Sibley declares, “I have apprehended 16 Indians . . . If found guilty they will be immediately executed . . . although I am somewhat in doubt whether my authority extends quite so far.”

September 28

Pope to Sibley: “[The Indians] are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.”

September 29

Sibley is promoted to the rank of Brigadier General.

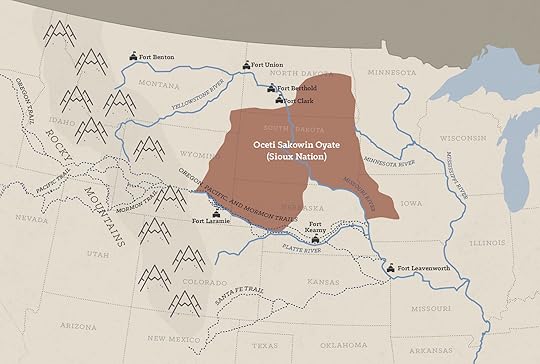

Henry Hastings Sibley was the convening officer of the Military Commission that condemned 303 Dakota men to death by hanging. MNHS Collections.

Henry Hastings Sibley was the convening officer of the Military Commission that condemned 303 Dakota men to death by hanging. MNHS Collections.October 4

Sibley orders the relocation of the entire camp—about 1500 men, women, children, and elderly—approximately 20 miles downriver to Yellow Medicine. At this point 29 Dakota men have been arrested and remain at Camp Release.

October 7

Sibley reports to Pope that he has convicted 20 prisoners under sentence of death by hanging.

September 28 – October 7

29 cases are conducted by the military commission. (2.9 cases per day)

October 7

Pope to Sibley: “The slightest effort that is made to interfere with the well merited death of these Indians will be considered treason to the Govt., and treated accordingly . . . We have and can have troops enough to exterminate them all, if they furnish the least occasion for it.”

October 11

After more Dakota people have surrendered themselves at Camp Release, four companies of Sibley’s army surround the Dakotas at Camp Release, seize their weapons, and take all men into custody.

October 11

Pope orders Sibley to move all Indians in his charge, whether guilty or innocent, to the Lower Sioux Agency.

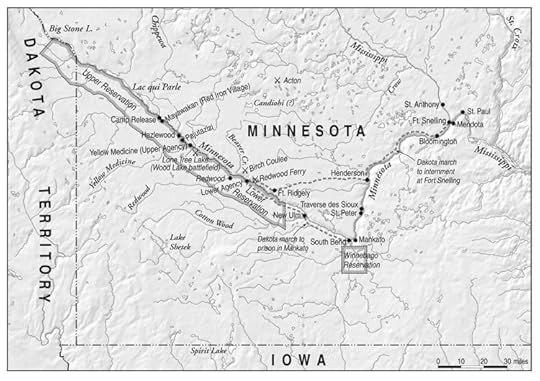

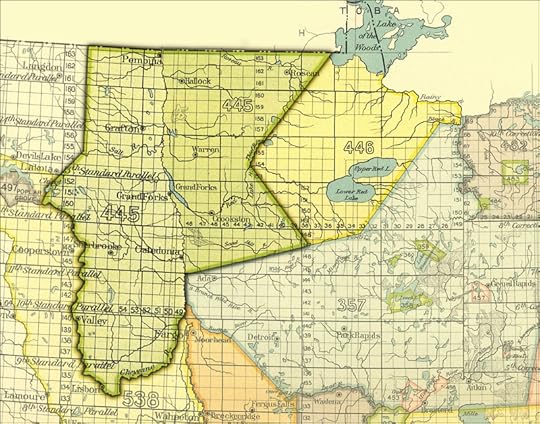

Map by the Pond Dakota Heritage Society

Map by the Pond Dakota Heritage SocietyOctober 12 (on or about)

After being told to expect their annuity payment, all weapons are confiscated from the Dakota men at Yellow Medicine. At this point there are 234 men at Yellow Medicine and approximately 100 at Camp Release.

October 15

Lieutenant Colonel William Marshall is replaced on the military commission by Major George Bradley.

October 15

Sibley directs his judges to streamline the remaining cases, declaring that they should proceed in each case only until they were satisfied as to a man’s “voluntary participation” in the war.

October 16

Sibley learns from Pope that all sentences of death must be approved by the President.

October 21

Sibley to Pope: “The commission is proceeding with the trials of prisoners as rapidly as possible. More than 120 cases have been disposed of, the greater part of whom have been found guilty of murder and other atrocious crimes, and there remain still nearly 300 to be tried . . . I shall suspend the executions until the pleasure of the President is known.”

October 23

Sibley orders the relocation of the entire encampment from Camp Release to the Lower Sioux Agency, approximately 45 miles downriver.

October 8 – October 23

110 cases are conducted by the military commission. (6.875 cases per day)

October 27

The “Cookhouse Trials” begin at the Lower Agency.

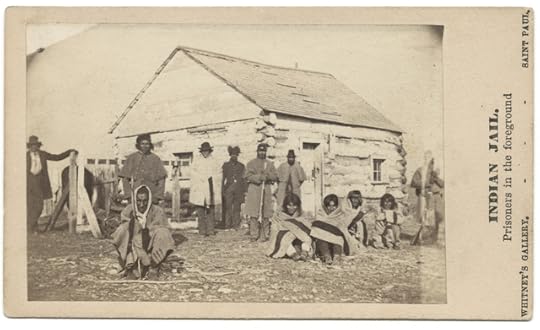

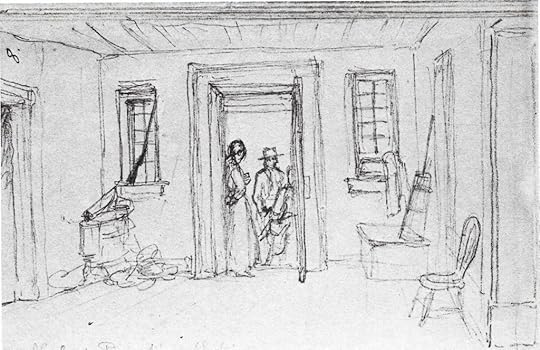

U.S. – Dakota War prisoners awaiting trial outside the summer kitchen of François LaBathe at the Lower Sioux Agency. MNHS Collections.

U.S. – Dakota War prisoners awaiting trial outside the summer kitchen of François LaBathe at the Lower Sioux Agency. MNHS Collections. October 27 – November 3

253 cases are conducted by the military commission. (36.14 cases per day)

November 3

The Dakota trials are completed. In 37 days (if you include September 27) 392 cases were tried. 323 men were convicted of the charges against them. 20 were sentenced to imprisonment. 303 were sentenced to death by hanging. 69 defendants were acquitted, however 61 of those exonerated remained in close confinement.

November 3

Stephen Riggs records a list of the 303 condemned men.

November 6

The list of condemned men is sent to Major General John Pope in St. Paul.

November 7

Approximately 1700 Dakota, who had not been sentenced to prison or death, begin a forced march from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling where they are detained throughout the winter.

November 9

The Dakota prisoners, approximately 375 in number, are marched from the Lower Sioux Agency to South Bend (near Mankato) where they are imprisoned at Camp Lincoln.

November 10

President Abraham Lincoln to Pope: “Your dispatch giving the names of 300 Indians condemned to death is received. Please forward as soon as possible the full and complete record of their convictions; and if the record does not fully indicate the more guilty and influential of the culprits, please have a careful statement made on these points forwarded to me. Send all by mail.”

November 11

Pope to Lincoln: “The people of this state, most of whom had relations or connections thus barbarously murdered and brutally outraged are exasperated to the last degree, and if the guilty are not all executed I think it nearly impossible to prevent the indiscriminate massacre of all the Indians—old men, women, and children.”

November 12

In Mankato, 14 Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) Indians are put on trial for their roles in the U.S. – Dakota War. All of them are acquitted of charges.

December 5

Lincoln directs White House legal advisors George Whiting and Francis Ruggles to review the trial transcripts and identify any men convicted of rape. After learning that only two cases meet this criteria, Lincoln directs Whiting and Ruggles review the transcripts again, this time identifying those cases where the convictions were based on specific charges of murder or massacre. Whiting and Ruggles identify 38 more cases, bringing the overall total to 40.

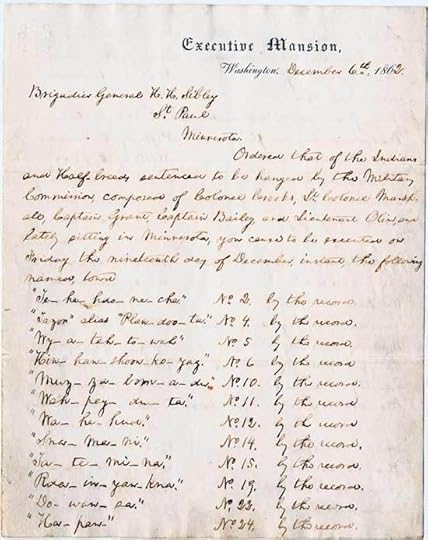

Lincoln’s Execution List. MNHS Collections. See the full list and get more information.

Lincoln’s Execution List. MNHS Collections. See the full list and get more information.December 6

Lincoln confirms the execution order of 39 Dakota men to take place on December 19. He also orders that the remaining prisoners are held subject to further orders. The one name he leaves off the list is Joseph Godfrey, a black Dakota who was recommended for clemency by the commission for his role as an expert witness throughout the Dakota trials.

December 11

Lincoln explains his reasoning for confirming 39 cases for execution to the U.S. Senate writing: “Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records of trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females. Contrary to my expectations, only two of this class were found. I then directed a further examination, and a classification of all who were proven to have participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles. This class numbered forty, and included the two convicted of female violation. One of the number is strongly recommended by the Commission which tried them, for commutation to ten years’ imprisonment.”

Read Lincoln’s Letter to the Senate.

December 15

Lincoln’s execution order arrives in Mankato.

December 15 (on or about)

Shortly after the execution order is given, Colonel Stephen Miller, who is in charge of the Dakota prisoners at Camp Lincoln, requests a postponement of the execution because he needs time to acquire more rope. There are also concerns about being able to correctly identify each of the condemned prisoners.

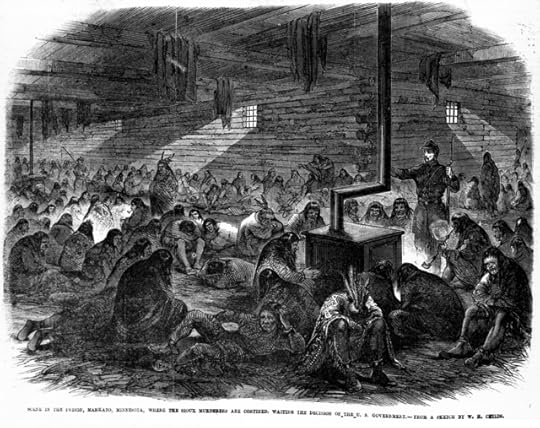

An illustration of the Dakota prisoners waiting to hear the decision of President Lincoln. Printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 31, 1863, page 300. MNHS Collections

An illustration of the Dakota prisoners waiting to hear the decision of President Lincoln. Printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 31, 1863, page 300. MNHS CollectionsDecember 15

Sibley to Riggs: “Have you a list of the condemned Indians? I suppose it was here but it cannot be found and you probably have it. I cannot say more for fear of miscarriage of this letter. Only speed your way, and above all say nothing of your having been summoned by me.”

December 16

Lincoln approves the postponement of the executions and reschedules it for Friday, December 26.

December 19

The list of condemned prisoners is found in possession of Major John Brown who is at Camp Lincoln.

December 22

The 39 condemned men are removed from the log shanty jail at Camp Lincoln to a room in the nearby three-story stone Leach Building.

December 25

After Jane and John Williamson expose new evidence, Lincoln issues a reprieve of Tatemina who, until then, was sentenced to death by hanging. This reduces the number of condemned men from 39 to 38.

December 26

Thousands gather in Mankato to witness the simultaneous execution of 38 Dakota men.

December 27

Sibley to Lincoln: “I have the honor to inform you that the 38 Indians and half-breeds ordered by you for execution were hung yesterday at Mankato, at 10 A. M. Everything went off quietly, and the other prisoners are well secured.”

November 11, 1865

After being kidnapped in Canada and smuggled across the border Sakpe (Shakopee) and Medicine Bottle are hanged at Fort Snelling.

Sources:

John A. Haymond, The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law and the Judgment of History, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2016).

Walt Bachman, Northern Slave Black Dakota: The Life and Times of Joseph Godfrey, (Bloomington, MN: Pond Dakota Press, 2013).

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

November 20, 2020

A Cruel Kind of Coercion: The Nelson Act of 1889

On January 14, 1889, Congress passed an Act for the removal of the Ojibwe people in Minnesota from their reservations. With the expectation of those at Red Lake, the Ojibwe were to be resettled on allotted sections of land within the boundaries of the White Earth reservation. The so-called “surplus” land that resulted from the removal and allotment, was to be sold at auction to white settlers, loggings companies, and mining companies. Known commonly as the Nelson Act of 1889, its actual title was, “An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota.” The act was made in the wake of the General Allotment Act of 1887, known more commonly as the Dawes Act.

According to the Dawes Act, and the successive Nelson Act, reservation land was to be broken up into sections and given to individual Native head-of-households as private property. The goal of this action, as seen by the U.S. government, was to break up the communal land holdings of the tribes, encourage private enterprise, foster the assimilation of Native peoples, and open up more land for white settlement and business. The Nelson Act took one step further than the Dawes Act by actually trying to eliminate some reservations altogether.

Ojibwe people living at the White Earth Reservation, circa 1890 – MNHS Collections

Ojibwe people living at the White Earth Reservation, circa 1890 – MNHS CollectionsLike most federal policies regarding Native populations throughout American history, the Nelson Act was marked by fraud, corruption, and greed. It unilaterally broke all previous treaties with the Ojibwe and further impoverished already desperate communities. As noted by the educational exhibit and website Why Treaties Matter, “many [Native] families lost their allotments through sales, tricks, contracts, taxes, and corrupt government officials” while “a few white men got very rich off of the timber and mineral contracts.” Commenting on the Dawes Act, writer David Treuer stated that, “allotment was as cruel a kind of coercion as the withholding of rations.”

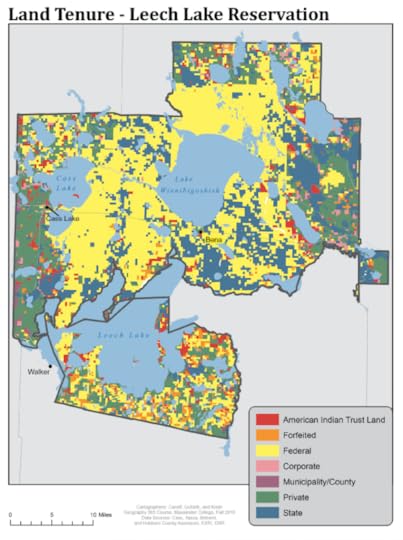

Land Ownership on the Leech Lake Reservation – Sourced from the Minnesota Center for Rural Policy and Development

Land Ownership on the Leech Lake Reservation – Sourced from the Minnesota Center for Rural Policy and DevelopmentUltimately, the Act did not succeed in eliminating the Ojibwe reservations in Minnesota. But it did directly and indirectly strip the Ojibwe of large sections of their land promised them by previous treaties. Furthermore, as non-Native owners acquired reservation lands, it “checkerboarded” Native held land making it impossible for Native communities to develop or protect the larger area. For instance, according to the Minnesota Center for Rural Policy and Development, of the 800,000 acres of land within the boundaries of the Leech Lake reservation, only 30,000 acres or four percent of that land is held by the Ojibwe tribe.

In 1999, after a long legal battle, the U.S. Court of Federal Claims awarded the Ojibwe tribe with twenty million dollars to compensate descendants for the losses their families suffered under the Nelson Act. Unfortunately, such compensation is miniscule when compared to the aggregate effects over time of the Nelson Act and other acts like it that illegally wrest away Native land.

Sources:

David Treuer, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America From 1890 to the Present, (New York: Riverhead Books, 2019).

“Nelson Act of 1889,” Wikipedia, Accessed on November 18, 2020, Last Updated on May 27, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nelson_Act_of_1889.

“This Day in History: The Nelson Act Defrauds Minnesota Chippewa of Land and Timber; Update on Paiutes and the Oregon Standoff,” Healing Minnesota Stories, Accessed on November 18, 2020, Published on January 14, 2016, https://healingmnstories.wordpress.com/2016/01/14/this-day-in-history-the-nelson-act-defrauds-minnesota-chippewa-of-land-and-timber-update-on-paiutes-and-the-oregon-standoff/#:~:text=This%20day%20in%20history%2C%20January,treaties%20and%20took%20tribal%20lands.

“The Chippewa National Forest: Educator Guide for Grades 6-12,” Why Treaties Matter: Self-Government in the Dakota and Ojibwe Nations, http://treatiesmatter.org/exhibit/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-Chippewa-National-Forest.pdf.

Larry Schumacher, “Solving a Land-Control Dilemma,” Minnesota Center for Rural Policy and Development, https://www.ruralmn.org/rmj/rmj_winter2014/rmj2014q3-land-control-dilemma/.

“An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota,” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/50th-congress/session-2/c50s2ch24.pdf

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

November 7, 2020

Beta Readers Wanted

I am looking for Beta Readers for my current Work-in-Progress, an alternative history novel titled, The Land of Sky-Tinted Waters.

This novel represents a departure from my previous publications. Rather than fictionalize history while leaning strongly toward known facts, I have created a complete reimagining of history that leans strongly toward character and setting. The novel is based on the events of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, but relies on two fictional main characters in order to look deeply at the lives of those who were affected by the war and its political and social context. Ultimately, rather than report what happened, I have created an alternative history that asks readers to look at the U.S. – Dakota War from a new perspective, and to question what it means for all of us today.

But…the novel is not ready for publication and I need your help to make it better! If you’re interested in reading an electronic version (Microsoft Word or PDF) of the current manuscript and offering feedback, please email me at mnauthor@colinmustful.com. I would like all feedback returned no later than December 31, 2020.

What is a Beta Reader?

A beta reader is someone who reads an unpublished manuscript and provides honest feedback to the author.

What’s the deadline for feedback?

If you agree to beta read, please return your feedback no later than December 31, 2020.

How will I know what feedback to give?

I want your overall opinion of the novel, but I will also include specific questions throughout the manuscript for you to consider.

What’s in it for me, the beta reader?

A lot! You get to be part of shaping a story with an important and valuable message. You get to read the story well in advance of most readers. And I will include your name in the Acknowledgements of the finished and published product.

What happens after I’ve finished reading and emailed my feedback?

I will be scheduling an individual interview with each beta reader so that I can get direct feedback and ask more specific questions about your thoughts on character, plot, setting, and so on.

October 19, 2020

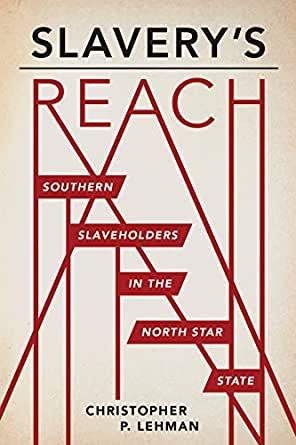

Book Review – Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State by Christopher P. Lehman

Slavery’s Reach by Christopher P. Lehman is an essential addition to the historiography of slavery in the United States of America. It is a well researched, eye-opening account of how slaveholders, their employees, and their benefactors infiltrated Minnesota through their political and economic influence. It shows not only how Southerners brought their unfree laborers and their wealth from unfree labor to the North, but how Northerners overlooked, acquiesced, and encouraged the influence of Southerners and their wealth. Slavery’s Reach is a heartbreaking acknowledgement of the greed for economic growth that benefited Minnesota and its citizens from the time it became a territory in 1849 until the time slavery was abolished by the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865. The cost of that greed – human lives, freedom, and dignity.

“Regardless of the ignorance of Minnesotans, they were complicit in some of the worst cruelties of southern slavery by conducting business with the slaveholders inflicting the cruelties.”

The book is laid out quite plainly, noting Minnesota’s connections to slavery in each of its varied forms chapter by chapter. The forms are numerous, two of which include fur traders, who were often employed by slaveholders, and commuters, who were Southern slaveholders that traveled to Minnesota during the summer months to buy up land and real estate. In each of these chapters, Lehman surgically analyzes the actions of men and women who either used their Southern wealth to enrich Minnesota or who were complicit in the political and economic advantages of that wealth. Lehman demonstrates, in more than adequate terms, the ways in which Southern wealth and influence permeated Minnesota while also accounting for those Northerners who looked the other way, or who indeed supported and collaborated with Southern interests.

While Slavery’s Reach is essential to our ever-widening understanding of our tainted past and its legacy for our present, it is not a digestible or compelling narrative. Rather, it presents a long list of politicians, entrepreneurs, businesspersons, and travelers who, in one way or another, accepted or contributed to Minnesota’s connectedness to slavery, slaveholders, and slave labor earned wealth. Though the research is impressive and necessary, it is presented with such a dry preciseness that without re-reading portions, it is difficult to follow an argument or example from beginning to end. The political, social, and economic context of the time period becomes redundant, repeating itself in almost every chapter. Also, there is no single anecdote, character, or narrative arc to drive the main argument of the book forward or string together its vastness of information.

“Beholden to the interests of slaveholders, Sibley did not enforce the state’s prohibition of slavery. When Sibley declined to run for reelection in 1860, he had given the state a reputation for tolerating enslaved people and their captors within its borders.”

With that said, I do not wish to dissuade readers from picking up this book. As a Minnesotan who has dedicated much time to researching and understanding Minnesota’s early history, I found Slavery’s Reach to be thoroughly enlightening and achingly tragic. Though it should come as no surprise, men like Henry Sibley, Alexander Ramsey, and Henry Rice—who did so much to exploit, subjugate, and destroy Native peoples and their land—also exploited slavery to the benefit of their own wealth and high-standing. As Lehman thoroughly demonstrates, money and comfort superseded morals and dignity at almost every turn. Even those claiming to be abolitionists, such as Jane Grey Swisshelm, the Republican editor of the St. Cloud Visiter, accepted Southern money when it benefited their interests.

“Minnesotans rarely interfered with the slaveholder-slave relationships in their hotels, and their apathy left slaves with no recourse but to forego the realization of their legal freedom.”

Far too many Minnesotans overlooked the sources of wealth pouring into the region during its early state and territorial periods. They made excuses for southern slaveholders or outright ignored legal and illegal human trafficking happening right under their noses. Today, we are reckoning with our legacy of profiteering at the cost of human dignity. Lehman shows us our legacy but stops short of anger and real condemnation—at least in writing. What do we do now? How do we choose to acknowledge the past without revering it, while making real change for the future and reparations for the lives that were stolen?

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

September 26, 2020

Alternative History: Reimagining the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862

What if the past had turned out differently? What if the outcomes of history were flipped—changed completely? What would the world look like today?

The U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 was a watershed event in Minnesota and American history with tragic and long-lasting results. But what if the defeated were the victorious? What if Little Crow and the Dakota joined forces with Hole-in-the-Day and the Ojibwe? What if an allied Native front overran Fort Ridgely, swept through New Ulm, and defeated U.S. forces at Fort Snelling? What if, on December 26, 1862, thirty-eight white Euro-American settlers were hanged while thousands of others were herded into forced internment at Bdote and later exiled from beyond the borders of the state? What if Minnesota wasn’t Minnesota at all? What if it was Mni Sota Makoce, a Native held and governed land?

These are the questions I am trying to answer in my newest novel, an alternative history that reimagines The U.S.–Dakota War of 1862. By asking these questions, I seek to view the past from another perspective. By shifting the perspective, I hope to illuminate the wrongs of the past while showing their direct connection to the present. Using well-rounded characters whose allegiances are both mixed and challenged, this story asks readers to reconsider their notions of right and wrong. It brings to life a world that might have been, demonstrating that everyone had something to gain and something to lose—someone to hate and someone to save. Culturally rich and historically detailed this alternative history gives readers a new way to look at the past and its legacy for today.

The novel, which is untitled, has not yet been set for publication. I am currently working on the first rounds of revision and plan to begin submitting the story to publishers early next year. In the meantime, I still have plenty of projects to keep me busy.

[image error]

This October, I will be an exhibitor at the 2020 South Dakota Festival of Books. This is my first time attending the SD Festival of Books and I’m excited to share my work with a new audience of readers. Kicking off on October 1, this virtual festival includes numerous authors, publishers, and literary and historical organizations. Extending through October 23, the festival has dozens of events that include readings, lectures, and workshops, most of which are free to attend. For a complete event schedule visit the website here: http://sdhumanities.org/festival-of-books/schedule/.

I’ve also recently launched my own small press called History Through Fiction. I began this press with a desire to share history using the same unique approach that I use in my own novels—combining elements of fiction and nonfiction. Books by History Through Fiction are based on real historical events and people and are rooted in real historical documentation. Our authors create compelling fictional narratives, bringing history to life through scene, setting, and dialogue, while also providing readers the resources to further investigate and understand history. Our first title, The Education of Delhomme: Chopin, Sand, & La France is being released this November.

While I strive to make a career out of writing and publishing, I’m not there yet. I currently work as a para educator for Coon Rapids High School. In this role I work with students with specialized needs, assisting them with their exams and coursework. This is my first year at Coon Rapids but my eighth within the Anoka-Hennepin School District. After school, I coach high school boys soccer at St. Francis High School. This is my seventh season at St. Francis and I really enjoy being a part of a team and being out on the soccer field every day. Finally, I also work weekends as a pizza delivery driver for Parkway Pizza in Northeast Minneapolis. I’ve worked several years at Parkway and I’m grateful to work in a fun, fast-paced environment alongside a hard-working and supportive team.

Stay tuned for more content and updates. Please visit me—virtually—at the upcoming 2020 SD Festival of Books, share my books with your friends, family, and colleagues, and make sure to follow me on all my social media channels!

August 18, 2020

Philander Prescott: A Victim of Minnesota’s Inevitable Conflict

On the morning of Monday, August 18, 1862, one hundred fifty eight years ago today, a faction of the Mdewakanton Dakota attacked and killed or took captive the settlers, traders, and government agents living at the Lower Sioux Agency in present day Morton, Minnesota. Prompted by more than a half-century of genocidal government policies and actions, the Dakota spread their attack throughout southwestern Minnesota, killing several hundred people while taking another 200-250 captive. In the following weeks, the Dakota launched numerous organized attacks at key American strongholds, but were eventually defeated at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. In the aftermath, thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged and the remainder of the Dakota and Ho-Chunk, whether they took part in the war or not, were exiled from Minnesota. The U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, as it is often called, is a major source of anguish and grief in the history of Minnesota.

A portrait of Philander Prescott about 1860. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society: https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/philander-prescott

A portrait of Philander Prescott about 1860. Image from the Minnesota Historical Society: https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/philander-prescottAmong those killed on the morning of August 18, was sixty year old Philander Prescott. Born in Phelpstown, New York, Prescott moved to Detroit in 1820 to work with his brother, Zachariah. Prescott was eighteen years old at the time. Later that year, Prescott and his brother moved to Camp New Hope (Fort Snelling), at the confluence of the Mississippi and St. Peter rivers, where a new military post was being built.

Upon arriving at Camp New Hope, Prescott took work as a clerk for the American and Columbia fur trading companies. In 1823, he courted a Dakota woman named Mary Spirit-in-the-Moon. In his reminiscences, Prescott described their courtship writing:

“It was ten days before I could get my wife, as she was then timid. At last, through much entreaty of the parents, she came for to be my wife or companion as long as I chose to live with her. Little did I think at the time I should live with her until old age . . . The old chief lived in his tent near us all winter. I fed and clothed them all winter.”

In a formal ceremony conducted by missionary Samuel Pond, the two were married in 1837. They had nine children together and remained married until Prescott’s death in 1862. Mary Spirit-in-the-Moon was taken captive but later released.

During Prescott’s lifetime, the centuries old fur trade dwindled, forcing him to seek other sources of income. This led him to a series of both adventurous and practical jobs as he adjusted to the ever-changing frontier circumstances. At one point, he worked on a steamship that operated between St. Louis and New Orleans. At another, he led mining ventures near the Platte River. He was also employed by Joseph Rolette to search for beaver near Traverse des Sioux and he helped survey the boundary line separating the Dakota and Ojibwe. In 1829, he was hired by Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro to teach agriculture to the Dakota living at Eatonville, an experimental farming community of Dakota living at Bde Maka Ska. In 1839, he spent a season holding a claim for land speculators at the confluence of the Mississippi and St. Croix rivers. The settlement born there became known as Prescott, Wisconsin. Prescott also worked as an interpreter at the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and at the time of his death he was the government appointed farmer at the Lower Sioux Agency.

This is a sketch of Prescott’s house by the artist Frank Blackwell Mayer. Mayer boarded with Prescott after he arrived in Minnesota territory for the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. Image from the Newberry Library in Chicago.

This is a sketch of Prescott’s house by the artist Frank Blackwell Mayer. Mayer boarded with Prescott after he arrived in Minnesota territory for the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. Image from the Newberry Library in Chicago. Philander Prescott was among the earliest white American settler-colonialists to the upper Mississippi region. His industrious character and adventurous spirit helped usher in a new era. And though Prescott integrated himself into the native Dakota culture and community, the skills he earned, the ties he developed, and the enterprises he performed, fostered a period of change and exploitation that saw the Dakota people and culture suppressed and mitigated until they believed war was their only choice. So, despite years as a friend, companion, teacher, and counterpart to the Dakota people, his life was not spared when vengeance visited the people of southern Minnesota.

Read “The Recollections of Philander Prescott, Frontiersman of the Old Northwest, 1819–1862.”

Sources:

Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

“Philander Prescott: An Inventory of His Reminiscences and Related Papers at the Minnesota Historical Society,” Minnesota Historical Society, Collection Finding Aids, http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/P2285.xml.

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

August 6, 2020

“The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee” and “What Does Justice Look Like?”: The Reaction of a White Minnesotan

Recently, I finished reading two nonfiction books by Indigenous Minnesotans about the history and future of indigeneity in America. One was The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present by David Treuer. The other was What Does Justice Look Like?: The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland by Waziyatawin. Treuer identifies as an Ojibwe from the Leech Lake Reservation while Waziyatawin identifies as a Wahpetunwan Dakota from the Pezihutazizi Otunwe (Yellow Medicine Village).

Before commenting, I’d like to identify my own background and interests. I am a white Minnesotan who grew up in the Twin Cities area of Minneapolis and St. Paul. While attending school in Mankato, I took an interest in what is now called the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. I pursued that interest by researching the war, its aftermath, and its historical context, and then by writing a series of essays, historical novels, and other resources related to the U.S. – Dakota War. More recently, I have written a historical novel about an event known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850 involving the Lake Superior and Upper Mississippi bands of Ojibwe. As my writing and interests have developed, my perspective and understanding has, too.

I highly recommend both books for Americans of all backgrounds no matter their race, gender, status, politics, or religion. The reading, though not a source of entertainment, is informative, sobering, and discerning. Regardless of how much readers may already know or not know about the history and arguments presented in these books, each will give readers something to think about.

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee is well organized and is written in an almost easy, objective tone. One of the book’s greatest strengths belongs to its first ninety-seven pages, in which Treuer divides present day America into distinct regions. He then describes the Native inhabitants of each region, and details their contact with European and then American colonialists. The brief context Treuer shares is a startling reminder, or perhaps lesson to some, of the genocide that swept over almost all Native peoples who lived throughout this country.

Treuer moves on to describe, in greater but still limited detail, the history of American/Indigenous relations from 1890 to the present day, using Wounded Knee as a watershed event. He organizes this part of the book by time period and by the policies and practices of the U.S. government that marked each period. Each section is characterized by interviews and anecdotes that blend in nicely with the historical facts and events.

After Treuer catalogues centuries of genocide, injustice, and trauma, he finishes his book in a tone of (what I would call) hopefulness. He recognizes that while Native Americans live with the challenges of historical trauma, on top of the burdens endured through destructive, inequitable policies, they have come to redefine what it is to be Native American—that is, they are Native and American. Natives are no longer hiding or somehow ashamed of their culture, language, and history. Rather, they embrace those things that make them uniquely Native while claiming their rights and inheritance as Americans.

Though Treuer’s book is in many ways heartbreaking, it is not condescending or cynical. And even though his book catalogues the past, he looks very much toward the future. I am left to wonder, however, what does that future look like and how far away is it?

Waziyatawin’s book, What Does Justice Look Like? bears little resemblance to Treuer’s—at least, regarding the tone and outlook. Like Treuer, Waziyatawin includes the historical context on which her lesson/argument is built. That is, she describes the history of the Dakota in Minnesota from creation to their exile in 1863. And, from what I can tell, she reports this history accurately, though she uses rather unambiguous and provocative language. For instance, calling the introduction of whites to Minnesota a “Wasicu Invasion.”

Waziyatawin takes a sharp turn from history to define genocide as laid out by the United Nations Convention on Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The definition includes five criteria which the author uses to show readers how each of the five criteria was met in Minnesota in violation of the Dakota people. Though harsh to contemplate, it is hard to dismiss the objective historical facts.

From this point in her book the author asks for truth and reparations. She contends that there was nothing innocent or unintentional about the take over of Dakota lands—that all settlers, traders, and politicians are accountable. She recommends that there ought to be a forum for acknowledgement and truth telling such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that occurred in South Africa after Apartheid. As for reparations, Waziyatawin leads with her argument to take down Fort Snelling, which, she disputes, is a symbol of genocide and colonialism built atop sacred land that rightfully belongs to the Dakota people. She goes on to argue that all historic forts, as symbols of colonialism and oppression, should be taken down.

Further reparations outlined in her argument include both a return from exile for those Dakota living away from their homeland, and a return of millions of acres of publicly held land. Waziyatawin stops short of extending a call for a return of all land, instead arguing for something more economically and practically viable. For instance, she points out that while much of the land in Minnesota is privately owned, there remains more than eleven million acres of publicly held land. Much of this land, she asserts, could be returned to the Dakota people without disrupting settler society. As a way to support her argument, she provides a stark reality by showing readers, using economic figures, just how much wealth is and has been extracted from the Dakota homeland. In many cases, that extraction has caused irreparable damage to the environment, something that further agonizes Dakota people—and all Minnesotans for that matter. By sharing economic figures on wealth, Waziyatawin is asking for a small portion to be given back to the Dakota people so that they can live with dignity and independence in their homeland.

Admittedly, Waziyatawin’s message is difficult to consume. Her tone, at times, is laced with bitterness. She questions the actions of other Dakota people and she draws numerous correlations to the Holocaust and Nazi Germany. That does not, however, invalidate the way she feels or mitigate the relevance of what she is arguing. What Does Justice Look Like? is indeed a confrontation—a confrontation that more and more Americans are realizing they need.

As for my reaction as a white Minnesotan, I am unnerved, saddened, and, in a way, capitulating. It is undeniable that what happened to the Indigenous populations of Minnesota, America, and the Western Hemisphere was a crime against humanity. It was a genocide. The responsibility that we, as a community, now hold is arguable, but our inheritance of wealth and freedom is not. As Waziyatawin points out and Treuer alludes to, Americans are not ready for the complete acceptance of our history, the truth of our inheritance, or the path toward justice, compassion, and dignity. This, of course, is evidenced by our current political and social climate that sees people marching in the streets, pulling down statues, and demanding reform.

I do not know the answer anymore then does Treuer or Wazayatawin, but I have recounted enough history and listened to enough Indigenous voices to know that something’s not right. Eventually, we will reconcile our past. We will acknowledge colonialism in America not for what it gave us, but for what it took away: life, peace, freedom, equality, dignity, empathy, humanity. It took away the basic humanity of countless groups and individuals and it is still doing so today. Eventually, we will reconcile—led, hopefully, by compassion, unity, and forgiveness. The only question that remains, is how long do we really need to wait?

Click here to learn about MAKOCE IKIKCUPI: A Project of Reparative Justice

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

July 13, 2020

The Treaty of Old Crossing

The Treaty of Old Crossing was signed October 2, 1863, at the “Old Crossing” of the Red Lake River near present day Huot, Minnesota. It was negotiated between the United States government and the Pembina and Red Lake Bands of Ojibwe. The original treaty ceded approximately 11,000,000 acres of land in northwestern Minnesota and northeastern Dakota Territory to the United States in exchange for $20,000 paid annually for twenty years, $100,000 paid out to traders for debts and depredation claims, and smaller amounts of money were to be set aside for various other services and implements. Additionally, according to the wording of the treaty, one-hundred sixty acres of land was to be provided “each male adult half-breed or mixed-blood . . . who has adopted the habits and customs of civilized life.”

Land ceded in the Treaty of Old Crossing. Image from Wikipedia.

Land ceded in the Treaty of Old Crossing. Image from Wikipedia. The treaty that was signed October 2, was not the first attempt to obtain the Red Lake and Pembina Ojibwe lands, nor was it the final agreement. Twelve years earlier, immediately following the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, a treaty was negotiated at Pembina for the cession of five million acres of land surrounding the Red River Valley. That treaty was negotiated by Alexander Ramsey, who was then Minnesota’s Territorial Governor, and signed on September 20, 1851. However, the treaty was never ratified by Congress as a concession for those southern Congressmen who sought to prevent or delay the addition of a free state to the Union.

Urged on by traders, railroad interests, and steamboat proprietors, another attempt at negotiating the Red River land cession was planned and organized for August of 1862. In mid August of that year, a huge supply train that was headed for Pembina and preceded U.S. negotiators reached Fort Abercrombie. Meanwhile, on August 25, a large number of Pembina and Red Lake Ojibwe gathered at the mouth of the Red Lake River as instructed. But, after the outbreak of the U.S. – Dakota War, U.S. negotiators, fearing travel was unsafe, canceled negotiations. The Ojibwe waited many weeks, consuming their rations and trade goods, before returning to their homes. The consumption of goods and rations were counted against them in later negotiations.

Because of the failed treaty in 1862, Ramsey was anxious to reopen treaty negotiations the following year. With the help of Episcopal Bishop Henry Whipple, negotiations were set for September of 1863 at the “Old Crossing.” The much anticipated occasion was preceded by a supply train of two hundred and ninety men, three hundred and forty mules, one hundred and eighty horses, fifty-five oxen, and ninety vehicles that reached the crossing on September 21, 1863. A week later, after Ramsey and co-commissioner Ashley C. Morrill arrived, it is reported that there were present 579 Indians and 24 half-breeds of Red Lake, and 352 Indians and 663 half-breeds of Pembina.

The initial proposal was rejected by the Ojibwe bands and treaty negotiations were tense. It has been noted that Ramsey set up a Gatling Gun aimed at the assembled bands and that, according to historian Ella Hawkinson, “the white men made threatening speeches, in an irritated tone, calculated to break down the Chippewa’s tenacity.” On October 1, Ramsey recorded in his diary that, “To day it looked as if all hope of success was gone . . .” But, after negotiations renewed the next day, a deal was made and the treaty was signed October 2, 1863. However, sources argue that U.S. negotiators intentionally misrepresented the purpose of the treaty as merely seeking “right of passage” rather than land cessions. Bishop Whipple wrote that the treaty was “from beginning to end a fraud.”

Norman Kittson was a fur trader, sutler, steamboat operator, and railroad entrepreneur. Kittson worked closely with men like Henry Hastings Sibley and Alexander Ramsey and was probably the most notable benefactor of the Treaty of Old Crossing. Image from MNHS Collections.

Norman Kittson was a fur trader, sutler, steamboat operator, and railroad entrepreneur. Kittson worked closely with men like Henry Hastings Sibley and Alexander Ramsey and was probably the most notable benefactor of the Treaty of Old Crossing. Image from MNHS Collections. Regardless, the treaty underwent numerous amendments in Congress because they believed it was too generous to the chiefs. Several of the original signatories refused to sign the amended treaty. However, after further negotiations led by Bishop Whipple and a delegation of Ojibwe which were held in Washington D.C., a revised treaty was agreed upon and signed on April 12, 1864. The supplemental treaty reduced the annual payment from $20,000 to $15,000, but allocated funds specifically between the Red Lake and Pembina bands, and included more provisions such as those for a sawmill, and to furnish a blacksmith, physician, miller and farmer.

Ultimately, the Treaty of Old Crossing was just one of many land cession treaties of the time period that supported the colonial, capitalistic advancement of the white American population while further suppressing Native culture and land rights. It was advocated by politicians and businessmen, who, in collaboration with one another, used their positions of power and influence to obtain and expand their political and economic advantages. Today, we have come to acknowledge this legacy of unethical colonial domination while struggling with how to reinterpret and reconcile this inheritance.

Read the original treaty – page 853

See this blog post on YouTube.

Sources:

Ella Hawkinson, “The Old Crossing Chippewa Treaty and Its Sequel,” Minnesota History, 15 (September 1934): 282–300; http://collections.mnhs.org/mnhistorymagazine/articles/15/v15i03p282-300.pdf

“Treaty of Old Crossing,” Wikipedia, Accessed July 10, 2020, Last Updated June 25, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Old_Crossing

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

July 4, 2020

Sell or Starve: Seizure of the Black Hills (Repost)

On July 3, 2020, the President of the United States delivered a speech in front of Mount Rushmore. The speech, which celebrated American independence, sparked controversy because of the nature of the historic landmark and the land—the Black Hills—upon which it was erected. As Americans acknowledge, reconcile, repair, and struggle with their past, it is important to understand that past. With that in mind, I am reposting this blog post from 2014 which briefly details the illegal seizure of the Black Hills by the United States government.

In 1868, the United States Government signed a treaty with various tribes of Lakota and Arapaho people in which they “set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” the region known as the Black Hills. However, less than a decade later the government formally seized this land.

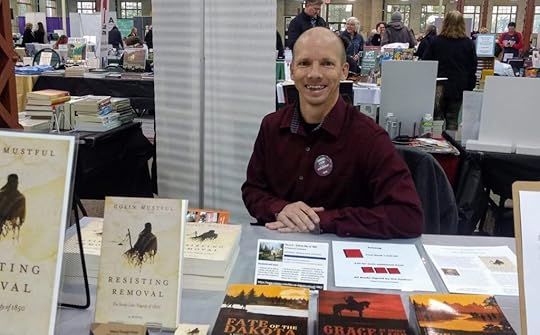

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie established a large tract of land for the Sioux Nation which included the Black Hills, land the Sioux consider sacred. Map from Native Knowledge 360° – https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/plains-treaties-fort-laramie/#

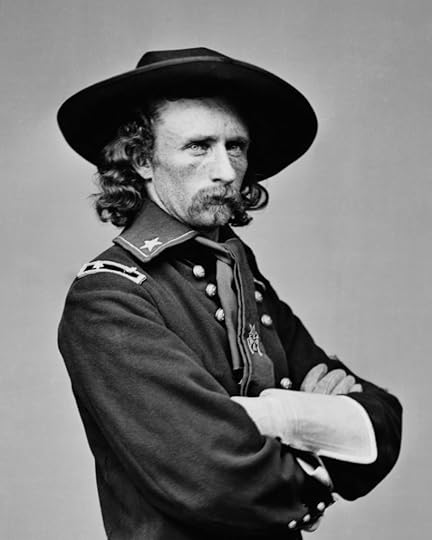

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie established a large tract of land for the Sioux Nation which included the Black Hills, land the Sioux consider sacred. Map from Native Knowledge 360° – https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/plains-treaties-fort-laramie/#Prior to 1868 it had long been suspected that the Black Hills were rich in mineral resources, in particular, gold. In the years following the Sioux Treaty of 1868, the U.S. government had either been unable or unwilling to prevent prospectors from entering the region. By 1873, General Phil Sheridan determined it was time once in for all to examine the Black Hill’s topography, flora, fauna, and most important, geology. Assigned to this task was General George Armstrong Custer. Upon entering the Black Hills in 1874, Custer and his expedition were met with dissension from Lakota tribes, but Custer assured the Lakotas that he was merely passing through and would obtain no title to their lands. Though Custer’s expedition recorded few results of mineral findings, Custer declared that the Hills were a veritable Garden of Eden. National newspapers trumpeted the news reporting that rich mines of gold and silver had been found. The Black Hills gold rush was on.

General George Armstrong Custer reported that the Black Hills were rich with mineral resources which spurred the Black Hills Gold Rush and led to the illegal claim and seizure of Native lands.

General George Armstrong Custer reported that the Black Hills were rich with mineral resources which spurred the Black Hills Gold Rush and led to the illegal claim and seizure of Native lands.Enthusiasm by miners at the news of gold far outweighed the army’s lackluster efforts to evict miners from the region. By August 1875, there were an estimated fifteen hundred miners in the Hills. By this time seizure of the Black Hills seemed inevitable and Americans began to rationalize such action. For instance, some argued that the Lakotas seldom used the Black Hills and therefore the land should not be left in their hands. Others argued that a new gold rush would create an immediate economic infusion that would stimulate business and bring hard times to an end.

As tensions mounted, the government decided to send officials to Lakota country in order to negotiate the sale of the Black Hills. The initial attempt was led by Iowa Senator William B. Allison and was known as the Allison Commission. On September 20, 1875, the commission opened a council attended by five thousand or more Lakotas, Yanktons, Santees, Cheyennes, and Arapahos. After more than a week of deliberating, the commission made a proposal to buy the Hills for $6 million or to purchase mining rights for $400,000 per year. Both offers were rejected. Angered by the Indian’s rejection, Allison suggested the government make a final offer that, if refused, would result in the termination of all appropriations for their subsistence in the future. Put bluntly, they would have to sell or starve.

The following summer at the the Battle of the Little Bighorn, General George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry Regiment suffered a major defeat at the hands of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors. This embarrassing loss created a thirst for revenge that added urgency to efforts to take the Black Hills. As a result, Congress passed legislation on August 15, 1876, which required the Lakotas to give up all claims to the Black Hills. If they refused, Congress would make no further appropriations for their support. This was followed by the establishment of the Manypenny Commission led by humanitarian spokesman George W. Manypenny. The Manypenny Commission traveled throughout the Lakota agencies pleading with the Indians to sign the agreement selling the Black Hills while accepting rations, clothing, farm equipment, and schooling. Though they were reluctant sign, many Lakota leaders reached the painful conclusion that if they failed to sign, Congress would carry out its threats and make survival for the Indians almost impossible. By the end of October, the Manypenny Commission had gathered 230 signatures from various Indian bands. This was just ten percent of the Lakota men living at the agencies. According to the 1868 treaty at least three fourths of all adult male Indians were required to sign any future treaty ceding land. But, Congress gave little thought to this treaty violation and on February 28, 1877, the United States officially seized the Black Hills.

Learn more about the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Article Source: Jeffrey Ostler, The Lakotas and the Black Hills: The Struggle for Sacred Ground. The Penguin Library of American Indian History: New York, 2010.

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

June 12, 2020

The Sand Creek Massacre

On November 29, 1864, approximately 700 U.S. army soldiers commanded by Colonel John Chivington, attacked some 1,000 Cheyenne and Arapaho people camped near Big Sandy Creek in eastern Colorado. It is estimated that between 150 and 500 Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed and mutilated, two-thirds of whom were women and children. The tragic event, which was initially celebrated by U.S. soldiers and civilians, is called the Sand Creek Massacre and is commemorated as a National Historical Site operated by the National Park Service.

The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie recognized a large swath of land south of the North Platte River and north of the Arkansas River, in eastern Colorado as territory of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people. But, in 1858 after gold was discovered in Pike’s Peak Country, thousands of gold hungry miners traveled through Cheyenne and Arapaho Territory along the Smoky Hill Trail. The Pike’s Peak Gold Rush brought with it an estimated 100,000 gold seekers who competed with Native populations for resources.

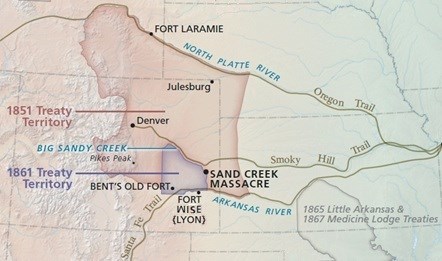

National Park Service Map

National Park Service MapThis led to the Treaty of Fort Wise, signed February 18, 1861, which redefined the Cheyenne and Arapaho Territory to 1/13 it’s original size. While the treaty was signed by several Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders, the majority of tribal authorities were angered by the agreement and disavowed the treaty. Those who disavowed the treaty continued to live and hunt throughout the original territory, and became increasingly belligerent to the constant stream of white migrants.

[image error]Major John M. Chivington commanded Union troops at The Battle of Glorieta Pass. He is infamous for leading an attack and massacre on peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho people camped at Sand Creek. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

At the same time, the American Civil War had broken out between Union and Confederate forces throughout the country. In the West, Confederate forces were defeated at Glorieta Pass in northern New Mexico Territory in March, 1862. Union forces were led by Major John M. Chivington, an American Methodist pastor who volunteered to fight when the Civil War began. After the Confederate defeat in New Mexico, Colorado established a home guard to protect settlers and trade routes throughout the territory. Chivington was placed in command of the Third Colorado Cavalry.

During the period that followed, American Civil War soldiers began attacking and destroying camps of peaceful Cheyenne. Then, on May 16, 1864, Cheyenne leaders Lean Bear and Star were killed by U.S. soldiers who approached them during a buffalo hunt. The soldiers were operating under the orders of Chivington to “kill Cheyennes whenever and wherever found.” The killings sparked attacks of retaliation by some of the Cheyenne in Kansas causing tensions to rise between white and Native populations.

Black Kettle was a prominent leader among the Southern Cheyenne. He survived the Sand Creek Massacre, but was killed four years later by U.S. forces led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Washita River. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Black Kettle was a prominent leader among the Southern Cheyenne. He survived the Sand Creek Massacre, but was killed four years later by U.S. forces led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of Washita River. Image from Wikimedia Commons.In order to de-escalate the situation, Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans invited the Cheyenne and Arapaho to Fort Lyon where they would be given provisions and protection. Black Kettle of the Cheyenne and Chief Niwot of the Arapaho brought their people to Fort Lyon in compliance with the peace parley and remained until they were asked to relocate to Big Sandy Creek about 40 miles to the northeast. After establishing their camp at Big Sandy Creek, Black Kettle flew an American and white flag above his lodge to show themselves as peaceful.

Nevertheless, Major Chivington and approximately 700 soldiers of the Third Colorado Cavalry, the First Colorado Cavalry, and the First Regiment New Mexico Volunteer Infantry, departed Fort Lyon on November 28 en route to the Cheyenne and Arapaho camp. Meanwhile, a large majority of the fighting age men in camp at Big Sandy Creek had left for a buffalo hunt, leaving mostly aged men, women, and children in the camp. Then, on the morning of November 29, 1864, Chivington ordered an attack on the defenseless and peaceful camp even while several of his men were within the camp at the time trading. For their part, Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer, refused to attack the camp and commanded their men to hold their fire. Most of the U.S. soldiers, however, obeyed Chivington’s order.

According to Captain Soule, “The massacre lasted six or eight hours” and “not more than two hundred, about 140 women and children” were killed. Soule also reported that women died while begging for their lives or, when they realized they couldn’t escape, cut the throats of their children before killing themselves. In a report to Major Edward Wynkoop, Soule wrote, “it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.” He also reported that “they were horribly mutilated” and that body parts were cut out as trophies.

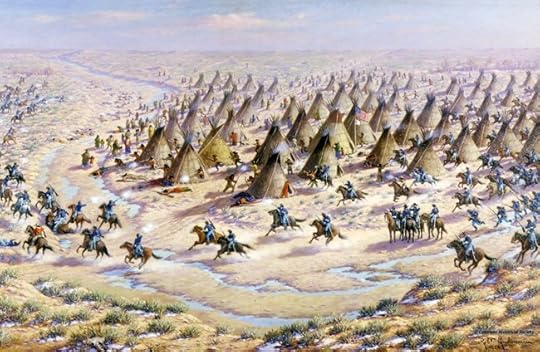

“The Battle of Sand Creek” by Robert Lindneaux. Image from the NPS and attributed to History Colorado. https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/index.htm

“The Battle of Sand Creek” by Robert Lindneaux. Image from the NPS and attributed to History Colorado. https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/index.htmThe U.S. army lost 24 killed and 52 wounded. Some of the Cheyenne and Arapaho were able to find cover on the bank of the creek and return fire, however, it is likely that many of the U.S. deaths were caused by “friendly” fire. As noted by Captain Soule, “there was no organization among our troops, they were a perfect mob.”

Chivington reported that five or six hundred Indians had been killed in a battle against a brave and numerous foe. U.S. soldiers in Denver were greeted with praise and acclaim while displaying the scalps they had cut. However, a few weeks after the attack, the truth had started to trickle out. A Joint Committee on the Conduct of War investigated the attack and ruled that Colonel Chivington “surprised and murdered, in cold blood, the unsuspecting men, women, and children on Sand creek, who had every reason to believe they were under the protection of the United States authorities.” Chivington could not be court-martialed because he had resigned from the military. The ruling effectively ended his political career. Captain Silas Soule, who testified against Chivington in the investigation, was shot dead in Denver a few weeks after his testimony. It is believed the assailants were associates of Chivington.

Because of its remote location and its timing within the larger context of the American Civil War, the events at Sand Creek, some argue, have been overlooked by history. There is no doubt, however, that it was a horrific and unwarranted attack on a peaceful and relatively defenseless group of innocent people. And while the truth that hindsight and history provide brings about discussion and healing, it cannot wipe away the shame and trauma now cemented into society. Unfortunately, The Sand Creek Massacre was just one of the countless injustices done to the Native populations of this country.

Watch this blog post on YouTube

Sources:

“Sand Creek Massacre,” Wikipedia, Accessed June 10, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sand_Creek_massacre

Tony Horwitz, “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More,” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/horrific-sand-creek-massacre-will-be-forgotten-no-more-180953403/

“Silas S. Soule: Two Letters Regarding the Sand Creek Massacre,” Author Kevin I. Cahill, Accessed June 10, 2020, https://www.kclonewolf.com/History/SandCreek/sc-documents/sc-soule-letters.html

“The Sand Creek Massacre – Captain Silas S. Soule letter to Major Edward Wynkoop regarding the massacre,” Author Kevin I. Cahill, Accessed June 10, 2020, https://www.kclonewolf.com/History/SandCreek/sc-documents/sc-soule-to-wynkoop-12-14-64.html

“Pike’s Peak Gold Rush,” Wikipedia, Accessed June 10, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pike%27s_Peak_Gold_Rush

“Lean Bear,” Wikipedia, Accessed June 10, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lean_Bear

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.