Colin Mustful's Blog, page 8

January 15, 2022

Author Update – The Tedious Submission Process

Dear Readers,

First, I’d just like to wish all of you a safe and healthy year.

In my last update, written in May 2021, I told you that I completed the first major revision of my full length manuscript titled, Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternative History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. Since then, I’ve been working hard trying to find an agent or publisher for my story. Today, I’m writing to update you on that process.

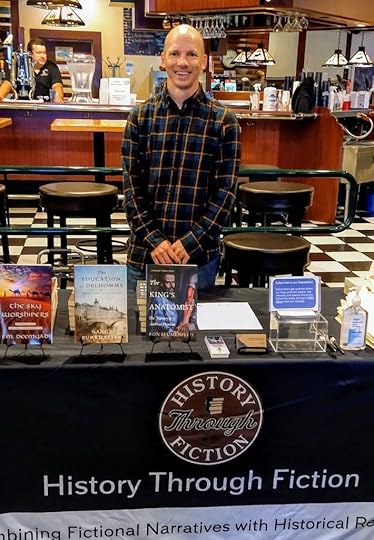

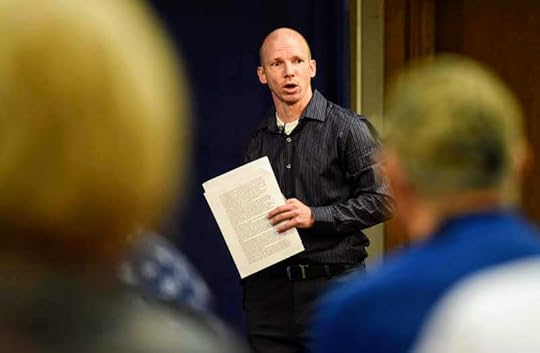

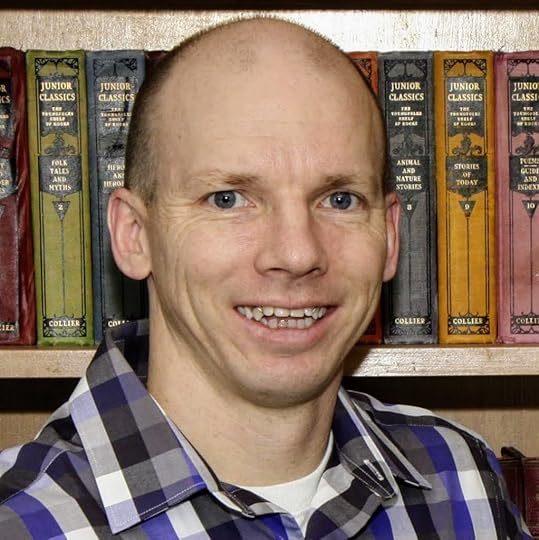

A photo of me representing my press, History Through Fiction, at the Deep Valley Book Festival in Mankato, in October, 2021.

A photo of me representing my press, History Through Fiction, at the Deep Valley Book Festival in Mankato, in October, 2021.Query and Synopsis Preparation – In order to catch the attention of an agent or publisher, it’s important to have a professional, engaging query letter and synopsis. That’s why, in July of last year, I hired Readerly to provide me with a service called Pitch Support. Working one-on-one with Readerly’s founder, Robin Henry, we wrote and rewrote a query and synopsis for my manuscript. Additionally, Robin edited the first fifty pages of my manuscript, which are often required for submission, and she helped me write one sentence log lines and 280 character Twitter pitches. Finally, Readerly identified twenty-five literary agents they believe would be most interested in representing my manuscript. The entire process took about six weeks, and I was very satisfied with the services provided. If you’re interested, you can read the query and synopsis here (Reader beware – there are spoilers in the query and synopsis).

Sensitivity Reading – In August, at the recommendation of Readerly, I asked Native American community members if they would read my manuscript to check for the accuracy of the Native history, culture, and language represented in my story. This is known as a sensitivity read. Thankfully, Michael A. (AmikoGaabaw) Loso, an enrolled member of the Mille Lacs band of Ojibwe, volunteered for this. Previously, Mike had read, and was impressed by, my novel Resisting Removal. After a few weeks, Mike returned the manuscript with a multitude of specific corrections and valuable insight which I then incorporated into the story. I am glad for Mike’s help, and I know it made the manuscript much better.

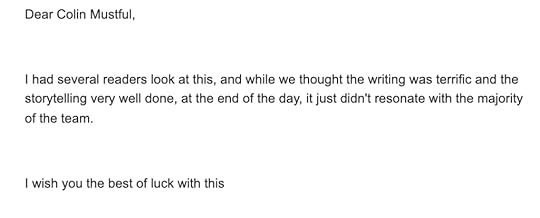

Submission Process – In September and October, using the list of agents provided by Readerly, I began submitting my manuscript for literary representation. Also, in November I began submitting directly to a handful of small presses. So far, I’ve submitted my manuscript to twenty-one agents and eleven publishers. Of those, I’ve received nine agent rejections and five publisher rejections. I’m still waiting to hear back from the rest. At the end of this blog post, I’ve shared screenshots of the rejections letters. They are discouraging, of course, but they are also part of the process.

Moving Forward – As you can see, I’m still waiting to hear back from more than half of the agents and publishers I’ve submitted to. Also, I plan to continue submitting before considering independent or hybrid publishing. However, the manuscript has not yet been through professional editing and, no matter what route the story goes through to finally reach your bookshelves, it will need to go through developmental editing from an objective, professional source. Because of this, I’m now in the process of searching for a developmental editor. This kind of edit is quite expensive (which is why I’ve avoided it so far) but also quite valuable. Therefore, in a month or two, if the manuscript hasn’t been accepted by an agent or publisher, I will hire a developmental editor to help me strengthen the story and give it a better chance of being accepted once I continue the submission process.

In the meantime, I’m keeping myself busy by managing my independent press, History Through Fiction. I’ve now published three books under the imprint, and I’ve just signed two new authors. I’m also busy promoting the press through social media, a podcast, and a virtual author panel series. I was also recently hired as a freelance editor to complete a copy edit of another author’s manuscript. This is a great way to help me generate income while using my skills, experience, and education. You can learn more about my editing services here: https://www.historythroughfiction.com/services

[image error]

[image error]

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

January 6, 2022

“Indian Warfare” in Minnesota: The Battle of Kaposia

In 1825, the United States government signed a treaty at Prairie du Chien with the Dakota and a multitude of regional tribes. In fact, they titled it, Treaty with the Sioux, Etc. Among the purposes of this treaty for the US government was “to promote peace among these tribes, and thereby to remove all causes of future difficulty.” The first line of the treaty actually states that “The United States of America have seen with much regret, that wars have for many years been carried on between the Sioux and the Chippewas . . .” As reported by the Ojibwe historian William Warren, the Ojibwe (referred to as Chippewa by the US government) had been continually at war with the Dakota (referred to as Sioux by the US government) since the Ojibwe’s arrival at Mooningwanekaaning (Madeline Island) centuries earlier. At the time of the 1825 treaty, it was in the US’s best interests to end the perpetual warfare in order to open the land to land speculators and settler-colonialists.

While the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien managed to create boundaries that would allow for the expulsion of Native peoples in later treaties, it did not quell the traditional warfare between the Dakota and Ojibwe. Neither, apparently, did the establishment of a military outpost at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, Fort Snelling, in 1825. According to Reverend Samuel Pond, who established a Christian mission at Bde Maka Ska in 1834, “we may reasonably conclude that the loss of life in the war carried on between the Dakotas and their enemies, was not much, if any less, most of the time after Fort Snelling was built, than it was before.” Furthermore, Pond stated that, “Both Chippewas and Dakotas complained that the efforts of our Government to promote peace between the two tribes, rendered their condition more insecure than when each one was left to take care of himself. That precarious peace often exposed them to dangers which in a state of open war they would have avoided.” Pond made these observations in an 1870 article he titled Indian Warfare in Minnesota.

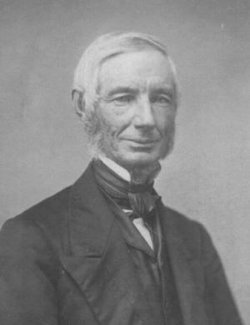

Samuel W. Pond was a Christian missionary who established a mission among the Dakota at Bde Maka Ska in 1834.

Samuel W. Pond was a Christian missionary who established a mission among the Dakota at Bde Maka Ska in 1834.In the article, Pond published ten years of notes he had taken about violence between the Dakota and Ojibwe in the region beginning with the year 1835. This was ten years after the Prairie du Chien treaty and just fourteen years before the region became Minnesota Territory. Regarding his notes, Pond says they are not a “relation of events of great importance in themselves, but [are] a fragment of Minnesota history, and may, at some future time be read with more interest than at present.” In total, Pond records twenty-one incidents of violence between the Dakota and Ojibwe peoples (while there were a few others between the Dakota and Sauks) despite the efforts of white authorities at Fort Snelling to avoid and mediate conflict. The total recorded loss of life in these attacks were 93 Dakota and 119 Ojibwe. It seems, each attack was inevitably followed by retaliatory attack, sometimes immediately, and sometimes in the following year. This is what made their warfare perpetual.

In an article published by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1925 titled The Story of Beengwa, Daughter of a Chippewa Warrior, the interviewee, Beengwa of the Sandy Lake Band of Ojibwe, calls particular attention to one of the attacks recorded by Pond. This attack, which took place in June of 1842, was called “the last battle between the Sandy Lake band and the Sioux in the latter’s territory” by Beengwa, and called “The Battle of Kaposia” by some historians. The attack was led by Beengwa’s father, a Sandy Lake Ojibwe named Augenosh. The war party was formed either at Fond du Lac or Sandy Lake and traveled down the Mississippi before meeting up with Ojibwe from the Mille Lacs and St. Croix bands. Upon reaching the opposite bank of the Dakota village of Kaposia, the Ojibwe lay in wait in the brush along a creek. This creek, which empties into Pig’s Eye Lake, is now known as Battle Creek.

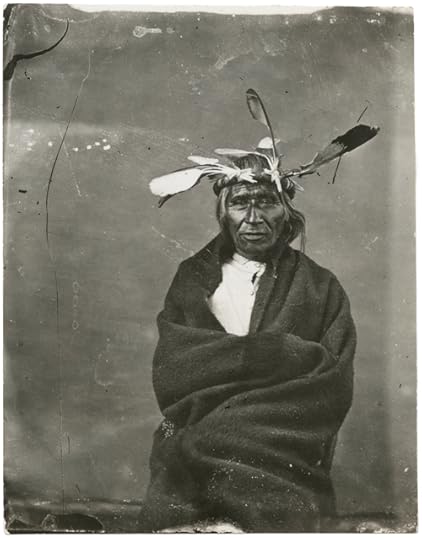

Augenosh was a leader among the Sandy Lake band of Ojibwe who helped orchestrate an attack on the Dakota at Kaposia in 1842. Photo from the MNHS Collections.

Augenosh was a leader among the Sandy Lake band of Ojibwe who helped orchestrate an attack on the Dakota at Kaposia in 1842. Photo from the MNHS Collections. Early in the morning, at Augenosh’s signal, the Ojibwe sprung their attack killing a handful of unsuspecting Dakota before slipping away back up river. Accounts of the attack vary. According to Beengwa, “The attack was entirely successful, many Sioux being killed without the loss of a single Chippewa warrior.” However, according to the historian interviewing Beengwa, “The Chippewa lost a number of warriors, but the Sioux loss is believed to have been greater.” Other historians, such as Pond, also record losses for the Ojibwe. While the exact number of losses are unclear, it does appear certain that it was a successful attack for the Ojibwe that was celebrated upon return to their homes. Beengwa stated that, “After the return of the war party a scalp dance was held. Members of other near-by bands came to Sandy Lake for the dance, which began at nightfall and continued through the entire night and most of the next day.” She also conveyed that the scalp of the first victim was placed upon a pole, colorfully decorated, and then passed “from village to village and from band to band until the celebration of the victory was completed.”

For a more comprehensive look at the history of warfare in the place we now call Minnesota, one would have to read the work of William Warren, an Ojibwe historian who, in the early 1850s, recorded the history of the Ojibwe people. Nevertheless, it’s interesting to read the tradition of attacks and revenge attacks that took place in the region all while white officials and missionaries sought, not to understand, but end such violence and traditions. Today, the only evidence that remains are in the notes of men like Samuel Pond or names of landmarks like Battle Creek in St. Paul and many others.

Sources:

Charles J. Kappler, ed., Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. 2 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904).

Irving H. Hart, “The Story of Beengwa, Daughter of a Chippewa Warrior,” in Minnesota History, 9:322 (December, 1928), http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/9/v09i04p319-330.pdf.

Rev. S.W. Pond, “Indian Warfare in Minnesota,” in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 3, (St. Paul: Published by the Society, 1880), p. 129-138.

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

[image error]November 29, 2021

“Poor, Even Extremely Poor”: The Unambiguous Findings of The Meriam Report

An overwhelming majority of the Indians are poor, even extremely poor, and they are not adjusted to the economic and social system of the dominant white civilization.

The Meriam Report, 1928

Dating all the way to its establishment, the United States government has a record of failed, often deplorable, and ever-changing policies toward Native American communities. Beginning in 1830, this includes policies such as Removal, Assimilation, and Termination. While the intentions of those policies can be argued (though it would be hard to argue they weren’t aimed at the dismantling and annihilation of Native people and culture), the results cannot. American Indian policy has left Native people without access to the wealth and opportunity their white counterparts enjoy. Matter-of-factly, it has left Native peoples either poor or dead. These direct results of American Indian policy were made all too clear in a 1928 report titled, The Problem with Indian Administration, more commonly known as The Meriam Report.

Commissioned by the Institute for Government Research and authorized by the Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work, the report was to be an economic and social study of Indian conditions. Lewis Meriam, a statistician who did serious work for the Census Bureau, was appointed as technical director of the survey. In an effort to be unbiased, the project was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation rather than by any department of the government. In order to conduct the survey, Meriam selected a team of specialists, some of whom were Native American. They included the following:

Ray A. Brown (legal aspects)

Henry Roe Cloud (Indian adviser)

Edward Everett Dale (economic conditions)

Emma Duke (Indian migration to urban areas)

Dr. Herbert Edwards (physician) (health)

Fayette Avery McKenzie (source materials)

Mary Louise Mark (family life)

W. Carson Ryan, Jr. (education)

William J. Spillman (agriculture)

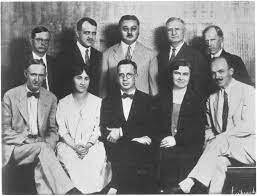

The Meriam Commission. Seated (left to right): Edward Everett Dale, Mary Louise Mark, Lewis Meriam, Emma Duke, Herbert R. Edwards, Standing (left to right): W. Carson Ryan, Jr., Ray A. Brown, Henry Roe Cloud, William J. Spillman, Fayette Avery McKenzie

The Meriam Commission. Seated (left to right): Edward Everett Dale, Mary Louise Mark, Lewis Meriam, Emma Duke, Herbert R. Edwards, Standing (left to right): W. Carson Ryan, Jr., Ray A. Brown, Henry Roe Cloud, William J. Spillman, Fayette Avery McKenzieThe team, which often worked separately in order to acquire more data, spent its first seven months visiting Native communities and reservations across the country. In total, they visited ninety-five locations in twenty-two states. They spent the next two and a half years compiling the data into an 847-page report consisting of eight major sections. Those sections included:

A General Policy for Indian Affairs

Health

Education

General Economic Conditions

Family and Community Life & the Activities of Women

The Migrated Indians

The Legal Aspects of the Indian Problem

The Missionary Activities among the Indians

The report was submitted to the Secretary of the Interior on February 21, 1928. Using facts and details, the report concluded that Federal Indian policy had been a complete disaster in every aspect. They argued that the poverty seen on reservations was largely the result of the Allotment Act of 1887 which privatized Indian land. They pointed out that the land allotted to Native peoples was barren and inhospitable, calling it “lands from which a trained and experienced white man could scarcely wrest a reasonable living.” They called the system of Indian boarding schools “grossly inadequate” and argued that Indian education should no longer be segregated from the majority culture. They argued that Indian health was “bad” and that their hospitals and care systems were “characterized as lacking in personnel, equipment, management, and design.”

Overall, the Meriam Report excoriated the government’s Indian policy. But, the report did lead to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 which would reverse many assimilation policies and restore land and mineral rights back to the tribes. The report also led to other policy changes such as the drafting of tribal constitutions, the creation of Indian-run courts, and the strengthening of Indian police. Unfortunately, the report could not make up for the century and half of mistreatment that preceded it, nor prevent some of the detrimental policies that followed.

Sources:

“Meriam Report,” Wikipedia, Accessed November 28, 2021, Last Updated March 15, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meriam_...

“The Meriam Report,” Native Amerian Netroots, Accessed November 28, 2021, Published July 7, 2010, http://nativeamericannetroots.net/dia...

David Treuer, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America From 1890 to the Present, (New York: Riverhead Books, 2019).

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

November 14, 2021

What’s New in Historical Fiction – An Author Panel Hosted by History Through Fiction

Dear Readers,

In addition to being an independent author, I am the founder and editor of a small press called History Through Fiction. In a few days, History Through Fiction will be hosting What’s New in Historical Fiction, a virtual author panel featuring historical novelists with new and upcoming titles. As the host and moderator of the event, I’d like to invite you to join us! The inaugural panel of what I hope to be a continuous series will include Dietrich Kalteis, author of Under an Outlaw Moon, Paula Martinac, author of Dear Miss Cushman, and Sarah Loudin Thomas, author of The Finder of Forgotten Things. Don’t forget to read all the details for special deals and giveaways!

Where: Crowdcast

When: Wednesday, November 17 @ 7pm Central

Learn more and Register

About the Authors

Dietrich Kalteis is an award-winning author of numerous novels and short stories. He is also the host of a monthly blog called Off the Cuff, a no-holds-barred and casual chat with guest authors on various aspects of writing and what they’re working on. His newest title, Under an Outlaw Moon, is based on the true story of Depression-era bank robbers Bennie and Stella Mae Dickson. She’s a teenage outsider longing to fit in. He’s a few years older and he’s trouble. They meet at a local skating rink and the sparks fly.

Paula Martinac is an award-winning author of seven fiction novels, three nonfiction books, and numerous articles, essays and short stories on LGBTQ themes. Also a playwright and teacher, Paula teaches fiction writing to undergraduates at UNC Charlotte and is an instructor and writing coach at Charlotte Center for the Literary Arts. Her newest novel, Dear Miss Cushman, which is set in 1850s Manhattan, features 18-year-old Georgiana Cartwright in a gender-bending role on stage that helps her find the courage to reject an arranged marriage and find love on her own terms.

Sarah Loudin Thomas is an award-winning author from West Virginia who writes Christian fiction that celebrates the people, the land, and the heritage of Appalachia. Sarah is a fund-raiser for a children’s ministry and currently lives near Asheville, North Carolina. Her new novel, The Finder of Forgotten Things, sees Sullivan Harris, an occasionally successful dowser, on the run after he promised the people of Kline, West Virginia, that he would find them water. After the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster, Sulley finds something new—a desire to help.

Deals and Giveaways

Ten registrants will receive a free Apple ebook of Under an Outlaw Moon.

All registrants will receive an exclusive 30% off discount code for any all formats of Under an Outlaw Moon.

Ten registrants will receive a free downloadable ebook of Dear Miss Cushman.

All registrants will receive an exclusive 25% off discount code for all formats of Dear Miss Cushman.

All registrants will receive an exclusive 25% off discount code for all books in the History Through Fiction catalog.

Register Now!November 2, 2021

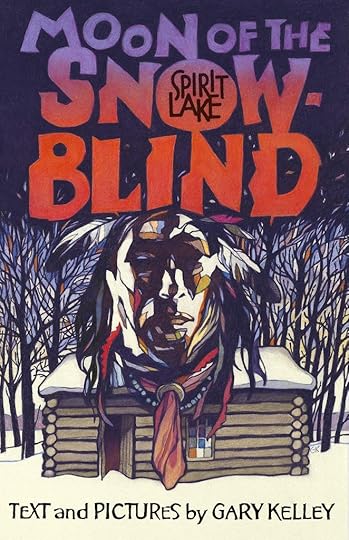

Book Review – Moon of the Snowblind

I’ve never read a graphic novel—until now. I was lured into reading Moon of the Snowblind by Gary Kelley because of its enticing cover, captivating title, and its compelling and tragic topic. Published on the one hundred sixty-fourth anniversary of that topic, Moon of the Snowblind is an illustrated portrayal of the Spirit Lake Massacre, an event that resulted in the death of more than forty settler-colonialists at the hands of a traditional band of Wahpekute Dakota. As the author of Grace at Spirit Lake, a historical novel that tells the story of the Spirit Lake Massacre and its aftermath, I was curious to see how another author chose to convey these events and their complicated history.

The novel opens with two quotes: one attributed to Spotted Tail, the Brulé Lakota tribal chief and the other attributed to Black Elk, the Oglala Lakota medicine man. The quotes, and their corresponding illustrations, express the ineludible nature and tragic impact of settler-colonialism on Native American peoples. It seems appropriate for the story that follows.

After a brief portrayal of the murder the Dakota leader Sidomindota and his family by the white horse trader Henry Lott, the novel centers upon the experience of the Gardners, a New York family compelled by Manifest Destiny to move west and resettle on the vast open prairies of Iowa. Through an array of exposition, dialogue, and black and white illustrations, the narrative shows the hardships and challenges, the joys and triumphs, of settler life while also hinting at the looming conflict ahead. Once winter arrives, survival becomes uncertain—for settler and Native alike.

The story progresses chronologically, using the Dakota and English months as chapter headings. It shifts back-and-forth between the Dakota and white experience, but focuses mainly on the massacre of the settlers at Spirit and Okoboji lakes and the harrowing captivity of young Abbie Gardner at the hands of the Wahpekute. It ends with the rescue of Abbie and the reconciliation of the white and Dakota communities. But it does not end without reminding readers of the tragic impacts westward expansion would continue to have on Native populations, most notably the hanging of 38 Dakota in Mankato in December 1862.

I am impressed with Gary Kelley’s Moon of the Snowblind. The illustrations are both engaging and keenly expressive while the story is informative and affecting. Some may take issue with the portrayal of one side or the other, believing perhaps it lacks objectivity. But at a time when the world has become acutely aware of our narrow representation of history, I believe it’s appropriate to question the stories we’re being told. It’s clear that Kelley knows his history and he’s found a unique and artistic way to share it. Let the readers glean what they can, add it to their own experience, and think critically about how our history will continue being told.

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes four historical novels, focusses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people.

October 14, 2021

Finding the Source of the Mississippi River: The Ojibwe Guide Who Deserves Credit

American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft is generally regarded as the man who found and identified the source of the Mississippi River in 1832. But this interpretation, which has been perpetuated throughout American history, fails on two levels—it does not recognize people who had already found the source of the Mississippi, nor does it acknowledge the contributions of Ozaawindib, the Ojibwe guide who led Schoolcraft to the river’s origin.

For several decades, U.S. explorers tried and failed to locate the source of the Mississippi River. The first U.S. backed expedition was led by Lieutenant Zebulon Pike in 1805/06. After meeting with the Dakota at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, Pike headed north with explicit instructions to locate the source of the Mississippi. After a long and challenging winter journey, Pike arrived at Upper Red Cedar Lake (later renamed Cass Lake). Believing he had reached the source of the Mississippi, Pike declared his mission accomplished and turned around to return home.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist who led an expedition to the headwaters of the Mississippi River in 1832.

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft was an American geographer, geologist, and ethnologist who led an expedition to the headwaters of the Mississippi River in 1832. Fourteen years later, in 1820, governor of Michigan Territory Lewis Cass led an expedition to map the region and locate the source of the Mississippi. Along with Cass was Henry Schoolcraft, the expedition’s mineralogist. Upon reaching Upper Red Cedar Lake, Cass, like Pike before him, identified it as the source of the Mississippi River. But Schoolcraft had his doubts, noting in his journal that the lake had two large inlets, one of which was called Mississippi by the Voyageurs.

Then, in 1823, an Italian named Giacomo Beltrami, took leave of an expedition headed by Major Stephen H. Long. From Pembina, Beltrami traveled southeast where he believed the Mississippi had its origin. After reaching Red Lake with the help of Native and French guides, Beltrami traversed the Mud River to a “small, heart-shaped lake, three miles in circumference” which he named Lake Julia. Beltrami was content to declare Lake Julia both the most southern source of the Red River and the most northern source of the Mississippi.

In 1831, with the actual source of the Mississippi declared but still uncertain, Schoolcraft was instructed to lead an expedition “into Lake Superior and the Mississippi country” in order to persuade the Ojibwe and Dakota peoples to end their perpetual warfare. The underlying purpose was to create peace in order to negotiate treaties and obtain the lands. Having successfully met with numerous Native communities throughout the summer of 1831, Schoolcraft decided to return to the region the following summer. In July of 1832, while leaving the region, Schoolcraft encountered a small party of Cass Lake Ojibwe led by Ozaawindib, known as Yellow Head by the whites. Ozaawindib was on her way to Sault Ste. Marie to warn white authorities of potential warfare. But, being that Ozaawindib was from Cass Lake, Schoolcraft saw this as an opportunity to, once-in-for-all, find the source of the Mississippi River. After some negotiation, he persuaded Ozaawindib to act as their guide for such a mission.

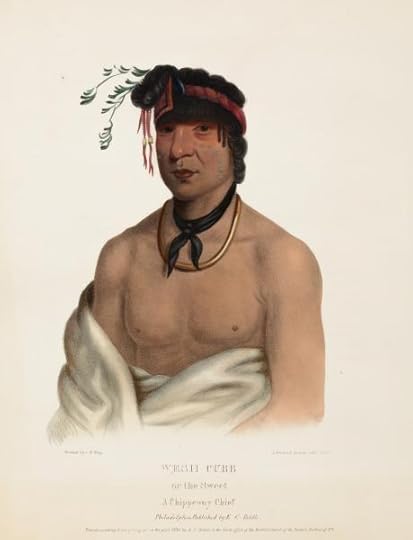

Wiishkobak was Ozaawindib’s father and a leader among the Leech Lake Ojibwe. Painting by Charles Bird King (1836). Image from the Smithsonian American Arts Museum. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/wesh-cubb-chippeway-chief-history-indian-tribes-north-america-34925

Wiishkobak was Ozaawindib’s father and a leader among the Leech Lake Ojibwe. Painting by Charles Bird King (1836). Image from the Smithsonian American Arts Museum. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/wesh-cubb-chippeway-chief-history-indian-tribes-north-america-34925Together with Schoolcraft’s party, Ozaawindib returned to Cass Lake where, according to historian William Watts Folwell, she immediately “collected five small canoes, drew maps, and engaged additional guides for the capital object of the expedition.” Then, on July 11, 1832 Ozaawindib guided the party to Lake Bemidji where they turned southwest along the eastern fork of the Mississippi now known as the Schoolcraft River. After two days of “toilsome navigation” and a six-mile portage heading west, the party arrived at what Schoolcraft called “a transparent body of water”—the source of the Mississippi River. Having accomplished his mission, Schoolcraft planted an American flag on an island in the lake. He proceeded to rename the lake, called Omashkoozo-Zaaga’igan by the Ojibwe and Lac La Biche by the French, by combining the Latin words Veritas (true) and Caput (head). It’s new name would be Lake Itasca. Upon returning to Cass Lake, Schoolcraft awarded their capable guide, Ozaawindib, with the president’s medal, a practice used by the U.S. government to identify Native Americans as chiefs among their people.

Schoolcraft’s accomplishment, while important, ignores the fact that the lake had already been identified and named by the French and the Ojibwe. And while awarding his Ojibwe guide the president’s medal may have shown gratitude, it failed to place Ozaawindib at her rightful place in history. Known among the Ojibwe as an agokwa—a person deemed male at birth who took on women’s roles—Ozaawindib was not only a guide who interacted with many French and American traders and explorers, but she was also a capable soldier. Her father, Wiishkobak, was a chief of the Leech Lake Ojibwe. As an agokwa, or Two-Spirit Ojibwe, living in the late 1700s and early 1800s, she likely had to navigate a complex and changing social environment. Nevertheless, she rose to the top of her community and greatly aided U.S. officials to end their decades-long mission to locate the source of the Mississippi. While Ozaawindib is remembered by several place names, she has not, as suggested by historian William Watts Folwell, received her full share of the credit.

Sources:

Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota, (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

William Watts Folwell, A History of Minnesota, Volume 1, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1922).

Pyle, Kai. “Ozaawindib (late 1700s‒?).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/ozaawi... (accessed October 12, 2021).

Pyle, Kai. “Ozaawindib, the Ojibwe Trans Woman the US Declared a Chief.” The Activist History Review. https://activisthistory.com/2019/06/13/ozaawindib-the-ojibwe-trans-woman-the-us-declared-a-chief/. (accessed October 12, 2021).

Warner, Mary. “Who Gets Credit? Naming the Source of the Mississippi River.” Morrison County Historical Society. https://morrisoncountyhistory.org/?page_id=338. (accessed October 12, 2021).

Colin Mustful is an author, historian, and publisher. His work focuses on the complex and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the American Midwest throughout the 19th century. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press publishing compelling historical novels. Mustful has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing.

September 2, 2021

The Trial of Chief Standing Bear (Ponca Series Part 2 of 2)

A statue of Chief Standing Bear in the National Statuary Hall

A statue of Chief Standing Bear in the National Statuary HallIn 1877, the Ponca of Nebraska, led by Chief Standing Bear, endured a 600 mile forced march from their homes near the Niobrara River to Indian Territory in present day Oklahoma. The removal occurred in the years after the U.S. government mistakenly gave away the Ponca Reservation lands in the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Ponca that survived the journey were resettled on uninhabitable swampland, causing many of the Ponca to die of disease in the months and years after resettlement. In January of 1879, Bear Shield, the son of Standing Bear, was among the Ponca who perished. In order to honor his son’s request, Standing Bear tried to return to the Ponca homeland to bury Bear Shield near the Niobrara River. However, when Standing Bear and his followers arrived at the Omaha Reservation in March of 1879, they were arrested by orders of General George Crook for leaving their reservation. Then, they were escorted to Fort Omaha to be held until their forced return to Indian Territory.

Read Part 1, The Ponca Trail of Tears.

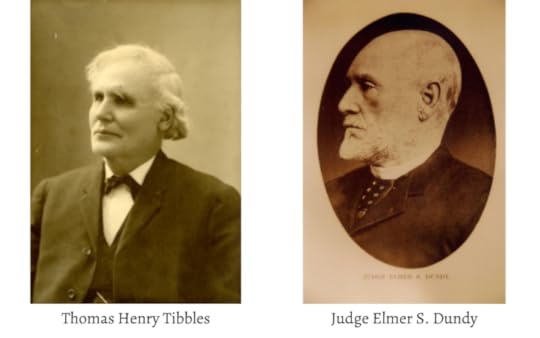

While being detained at Fort Omaha, the small group of Ponca became sick which delayed their return to Indian Territory. It was during this delay that the plight of Standing Bear and the Ponca drew the attention of Thomas Henry Tibbles, the assistant editor of the Omaha Daily Herald. Known as an ardent Indian right’s activist, Tibbles sympathized with the Ponca’s situation and worked quickly to share Standing Bear’s story. Then, he enlisted the support of local ministers to petition the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz, to reverse his removal order. During this time Tibbles also spent many nights in a law library devising plans for a court case that might free Standing Bear and his followers. With a rough idea in mind, Tibbles brought the case to the attention of lawyers John L. Webster and A.J. Poppleton. The lawyers agreed to represent Standing Bear without a fee and then petitioned Judge Elmer S. Dundy of the United States District Court for a writ of habeas corpus—a legal order that challenges the lawfulness of an imprisonment. Judge Dundy issued the writ and ordered the opposing parties to appear before him in court.

The case of Standing Bear v. Crook opened in Omaha on April 30, 1879 and lasted just two days. As the lawyer representing General Crook and the U.S. government, G.M. Lambertson argued that as an Indian, Standing Bear could not sue the government because he was neither a citizen, nor a person. Furthermore, as dependents of the government, Lambertson argued, Indians were not entitled to the rights and privileges of citizens. On the other side, the attorneys for Standing Bear argued that the Ponca had made great advances and were no longer dependent on the government. Also, and more importantly, they said that the Ponca were citizens and people and as citizens were entitled to all the rights and privileges granted by the fourteenth amendment. Finally, Poppleton and Webster pointed out that the U.S. had no legal right to take the Ponca land in the first place. Speaking through an interpreter, Standing Bear stood before the judge and said, “That hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. God made us both.”

Ultimately, Judge Dundy agreed with Standing Bear and his attorneys, ruling that “an Indian is a person within the meaning of the law” and that Standing Bear was being held illegally. The decision freed the Ponca from imprisonment and allowed Standing Bear to return to his homeland to bury his son. Congress acknowledged that they had wronged the Ponca when they gave away their lands, and by 1890 the Ponca were provided individual allotments of land along the Niobrara. The ruling by Judge Dundy was a landmark civil rights decision that has been compared in impact to cases such as the Dred Scott Decision and Brown v. Board of Education. However, Native peoples were not granted full citizenship until the Indian Citizenship Act on June 2, 1924.

Sources:

NebraskaStudies.org, “The Story of the Ponca,” Accessed August 30, 2021, https://nebraskastudies.org/en/1875-1899/the-trial-of-standing-bear/the-story-of-the-ponca/

Jennifer Davis, “Chief Standing Bear and His Landmark Civil Rights Case,” Library of Congress, Posted November 21, 2019, Accessed August 30, 2021, https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2019/11/chief-standing-bear-and-his-landmark-civil-rights-case/

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and forgotten past.

August 18, 2021

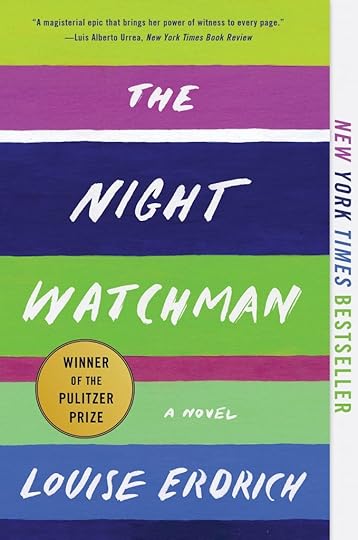

Book Review – The Night Watchman

On a small Indian Reservation in northern North Dakota, Thomas Wazhashk, the night watchman at the Turtle Mountain Jewel Bearing Plant, is struck by the words of a government bill. Those words—to provide for the termination of—were part of a 1953 government bill that sought to end all federal supervision of American Indian tribes and abrogate all treaty arrangements. Thomas knew that this policy would be disastrous for his people and he was determined to stop it from happening.

As Louis Erdrich’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel opens, it’s clear that although life isn’t perfect at the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation, it is filled with tradition, freedom, and hope. Life is rooted in the past, with few, if any, modern conveniences available for the hard-working but poverty-stricken Turtle Mountain Chippewa. While Wazhashk works as the night watchman, Pixie Paranteau is one a handful of young women who work the most coveted manufacturing jobs because they scored higher in manual dexterity than did men. The story progresses when Wazhashk, who is the fictional representation of Erdrich’s grandfather Patrick Gourneau, recognizes that the new Indian Termination Policy is detrimental to his people and would strip them of their remaining lands. A skilled writer, Thomas quietly goes about fighting the bill through a variety of written correspondences while organizing a delegation to Washington D.C. Pixie goes on her own mission to find her sister, Vera, only to be lured into strange new job at a Minneapolis bar. She returns to the reservation without Vera. Instead, she comes back with Vera’s son and the beginnings of a relationship with Turtle Mountain boxer Wood Mountain.

As Wazhashk goes to work each night, and helps organize against the bill each day, Pixie longs to see her sister again while discovering who she really is as a woman, sister, daughter, and friend. The novel continues this way, bringing various characters in and out of the story through short but deeply revealing chapters. Almost hidden between the personal details of each character’s life, are actual facts and commentary from this episode in time when Patrick Gourneau and the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa fought against termination. In the end, all the stories connect for an ambiguous but realistic conclusion.

You cannot feel time grind against you. Time is nothing but everything, not the seconds, minutes, hours, days, years. Yet this substanceless substance, this bending and shaping, this warping, this is the way we understand our world.

There are many praiseworthy elements of Erdrich’s story, as made evident by its status as a Pulitzer Prize winning novel. What I found most endearing was the absence of a clearly identified hero. Titled “The Night Watchman”, I began the novel believing that Thomas Wazhashk, as the central figure, would be the hero—the man who takes on the power of the U.S. Government and defeats it. Rather, there’s a subtly to Thomas’ life and actions that portray him not as a hero, but as a man. The same can be said for each character in this novel. They are not heroic figures or caricatures that exist to prove a point or embellish an important historical moment. They are deeply human and therefore profoundly real.

By fully humanizing her characters—by making each character the main character of their own story—Erdrich has created historical fiction in its truest form. This is life, the author seems to be saying. It is a people cast aside by the dominant society, left to live in poverty and grief, but who exist every day to work, love, live, hope, dream, and fight for themselves and their futures. Consider Millie Cloud, for instance, the young Chippewa Scholar brought in from Minneapolis to give Congress an economic study of reservation conditions. Millie does not swoop down from the rafters with a sword and shield, though it would have been easy, and probably tempting, to write Millie as a gallant, fearless figure. Instead, Millie is a reluctant hero who is rather naive about her people and the historic legacy they carry. Millie, like all the characters in the novel, plays her role while struggling to navigate her own life and feelings. And isn’t that what we’re all trying to do?

Millie knew enough from her interviews to understand that being adopted by a Chippewa was a special mark of friendship and honor. But for some reason what Patrice said didn’t make her feel all one way. She was both happy and for some reason disappointed. And her feelings ran on this way in the silence. Companionable though it was, she felt unsettled and was left wanting by what Patrice had offered. It was as if a marvelous design had flashed before her, and disintegrated, before she could grasp the figures it conveyed.

The contributions of the 1954 Turtle Mountain delegation to Washington D.C., the Chippewa boxers who fundraised for the trip, and the scholars who wrote the economic study cannot be understated. As Erdrich notes in her afterword, they were the first to mount a defense against the termination policy and prevail. Before the policy was finally ended in the 1970s, 113 tribal nations were terminated by the U.S. government resulting in the loss of 1.4 million acres of tribal land. The policy, like so many before it that sought to solve the “Indian Problem,” was an utter disaster for Native American peoples. Erdrich makes this clear, but not with heroic, larger-than-life characters or vicious, ugly villains. There are no cliches or grandiose statements. Nor does she rely on facts or figures to prove her point. Erdrich creates real people living under real circumstances, each one with their own set of deeply personal thoughts, feelings, and decisions to make. Ultimately, it is quite remarkable to get to know these people, to empathize with their situations, and to understand that they are not heroes. They recognized injustice and decided to do something about it. We can do the same thing.

Colin Mustful is an author, historian, publisher, and editor. He is the author of four historical novels and the founder and editor of his own press, History Through Fiction. He has a Masters degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing with a concentration in publishing. His books combine elements of fiction and nonfiction to tell compelling and educational stories. Learn more and purchase Colin’s books at https://colin-mustful.square.site/

Want a copy of The Night Watchman? Get a discount by buying yours in my online shop.

July 20, 2021

The Ponca Trail of Tears (Ponca Series Part 1 of 2)

The forced removal and relocation of Native tribes by the U.S. government is a common theme in the history of U.S. relations with Native peoples. The forced removals often, if not always, broke with previous treaty agreements and the hazardous conditions of the relocation marches resulted in many Native deaths. The most widely-known of these marches is called the Cherokee Trail of Tears which took place in 1838 and caused the death of approximately 4,000 Cherokees. The Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850, portrayed in the novel Resisting Removal, caused the death of approximately 400 Ojibwe due to the same Indian removal policies. Like the Cherokee, Ojibwe, and many other Native tribes before them, the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska was also removed from their homes and forced to make a long and deadly march.

The Ponca are a small tribe that are thought to have migrated west from the Ohio River Valley to the Great Plains. In the mid-16th century they migrated north along with several other tribes. After separating from those tribes, they settled near the mouth of the Niobrara River. Numbering about 800 people in 1779, the Ponca suffered a smallpox epidemic and their population was reduced to about 200 in 1804 when they were visited by the Lewis and Clark expedition. By 1874, their population had rebounded to 733 individuals.

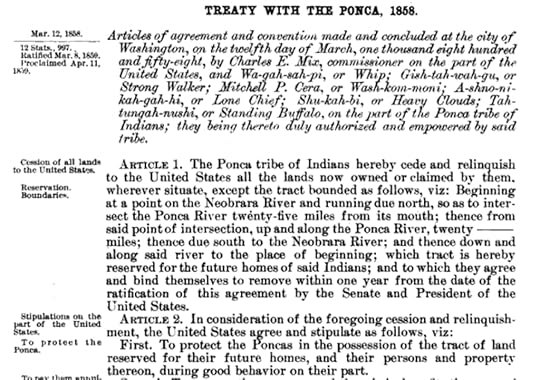

The Ponca signed a series of treaties with the United States beginning in 1817. In a treaty signed in 1858, the Ponca agreed to cede their lands in exchange for a reservation located on the Niobrara River as well as annual cash payments, educational facilities, a grist and saw mill, and several agency contractors. According to Article Two of the 1858 treaty, the United States agreed “to protect the Poncas in the possession of the tract of land reserved for their future homes, and their persons and property thereon, during good behavior on their part.” However, in 1865, the U.S. negotiated a new treaty with the Ponca that moved their reservation to a position east and south of its original location.

In 1858, the U.S. promised “to protect the Poncas in the possession of the tract of land reserved for their future homes, and their persons and property thereon, during good behavior on their part.”

In 1858, the U.S. promised “to protect the Poncas in the possession of the tract of land reserved for their future homes, and their persons and property thereon, during good behavior on their part.” Despite their promise to protect the Ponca in possession of their lands, the U.S. mistakenly gave away the Ponca reservation by placing it within The Great Sioux Reservation created by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Because of this mistake, conflict arose between the Ponca and the Sioux/Lakota, who claimed a legal right to the Ponca land. As a result, the U.S. had to find a way to remove the Ponca from their homelands.

In 1875, Indian agent to the Ponca, A.J. Carrier, recommended to President Grant that the Ponca be moved to Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). Grant agreed to the move as long as it was approved by the Ponca leaders. Carrier returned to the Ponca who, after some negotiation, agreed to move to Indian Territory. According to the terms, however, the Ponca leaders were allowed to select the site for their new reservation. Therefore, on February 2, 1877, Standing Bear and several other Ponca leaders began a trek south to the Osage Reservation to scout their potential new home. Upon their arrival, they found that many of the Osage leaders were absent and that the land was unsuitable for relocation. The Ponca leaders then told Indian Inspector E.C. Kemble that they wished to return home without surveying the lands. Kemble was furious and refused to support them on their journey home. Without rations, and exposed to harsh winter conditions, the Ponca made the strenuous journey home where they arrived on April 2, 1877.

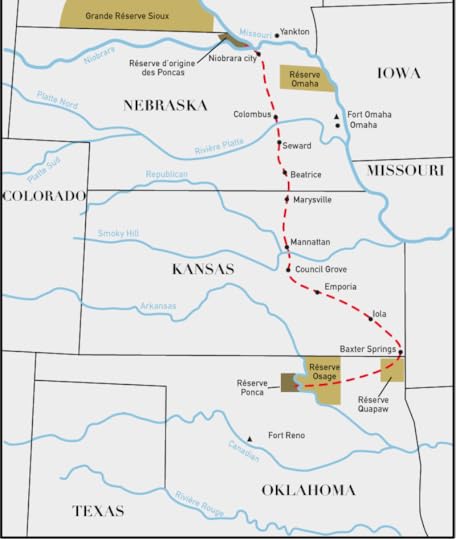

Route of the deportation of Standing Bear and the Ponca tribe in 1877. Map from Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trajet-ponca.png

Route of the deportation of Standing Bear and the Ponca tribe in 1877. Map from Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trajet-ponca.pngWhen the Ponca leaders finally made it back to their reservation, they were met by Special Agent Kemble who told them that he had orders to remove them to Indian Territory—by force if necessary. A small contingent of Ponca, about 170 of their citizens, agreed to go voluntarily and left for Indian Territory on April 16, 1877. The remainder, about 500 Ponca citizens, remained on their Nebraska reservation until General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered two companies of American soldiers to Ponca territory to force their compliance. The Ponca, led by White Eagle and Standing Bear, departed their reservation on May 16, 1877. The 600 mile, 54-day journey south was plagued by poor weather conditions and resulted in the death of nine Poncas, including Standing Bear’s daughter, Prairie Flower, who died of consumption and was buried at Milford, Nebraska.

On July 9, 1877, the Ponca arrived at Indian Territory where their hardships continued. First, they suffered severe economic hardships at the loss of their homes and property. Also, their new location was a swampy area in a tropical climate which caused diseases such as malaria and yellow fever. In the first six months at their new location, 141 Ponca died. Before long, the death toll exceeded 200 people, or about 30% of the Ponca population. In January 1879, Standing Bear’s son, Bear Shield, was among those Ponca who perished because of the poor conditions at their new reservation. After his son’s death, Standing Bear requested approval from U.S. officials to return to his homeland along the Niobrara River so that he could bury his son. His request was denied. What followed, resulted in a landmark civil rights decision that forever changed the status of Native Americans under the law.

To be continued…

Sources:

Wikipedia, “Chief White Eagle,” Accessed July 19, 2021, Last Updated January 11, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_White_Eagle

Wikipedia, “Trail of Tears,” Accessed July 19, 2021, Last Updated June 19, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trail_of_Tears

Kathy Weiser, “The Cherokee Trail of Tears,” Legends of America, Accessed July 19, 2021, Last Updated May 2020, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/na-trailtears/

NebraskaStudies.org, “The Story of the Ponca,” Accessed July 19, 2021, https://nebraskastudies.org/en/1875-1899/the-trial-of-standing-bear/the-story-of-the-ponca/

NebraskaStudies.org, “The Ponca Trail of Tears,” Accessed July 19, 2021, https://nebraskastudies.org/en/1875-1899/the-trial-of-standing-bear/the-ponca-trail-of-tears/

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian whose work focuses on the complicated and tumultuous time period when land was exchanged between Native and American hands. Using elements of fiction and nonfiction, Mustful’s work relies on real historical figures and documentation while creating compelling narratives that bring history to life. He has Masters degrees in history and creative writing and he is the founder and editor of an independent press called History Through Fiction.

June 26, 2021

Minnesota’s First, First Daughter: Wahkiyee, or Helen Hastings Sibley

Henry Sibley in 1849. Image source: https://www.legendsofamerica.com/mn-h...

Henry Sibley in 1849. Image source: https://www.legendsofamerica.com/mn-h...Henry Hastings Sibley is a well-known figure in Minnesota history. He came to the region as a fur trader in 1834 and quickly established himself as a business and political leader. Among his many roles and accomplishments he helped negotiate the 1851 treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, he was a member of the Minnesota Constitutional Convention, he served as the first Governor of the State of Minnesota, and he was the leader of the military forces against the Dakota during the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. Today, numerous places bear his name including Sibley County, Minnesota; Sibley, North Dakota; Sibley, Iowa; Hastings, Minnesota; and Sibley State Park.

Years before Sibley rose to political prominence in the region, he married a Franco-Dakota woman named Tahshinaohindoway, known as Red Blanket Woman. Tahshinaohindoway was the daughter of Wasuwicaxtaxni (Bad Hail), a well-known Dakota spokesman during the treaty negotiations of 1837 and 1851. The two were together on a hunt in the winter of 1839–40 when they married in a style known as a la facon du pays, or, country style. This was not unusual in this region or this time period. Such unions were thought to be socially and economically advantageous for both parties. However, despite any benefits, the Native women in these unions were brought into a patriarchal society and often lost both personal autonomy and control over their children.

Such was the case in the marriage between Sibley and Tahshinaohindoway. The couple welcomed the birth of a daughter on August 28, 1841. She was named Wahkiyee, or Bird, while her Christian birth certificate identifies her as Helene, the daughter of Tahshinahohindoway and an unnamed father. Much remains unknown or uncertain about Tahshinahohindoway in the years following Wahkiyee’s birth. She is thought to have married a Dakota man sometime after Sibley abandoned her, and she died in the years shortly thereafter. In 1843, Sibley traveled to Baltimore for the wedding of Franklin Steele and Anna Barney. There he met Steele’s sister, Sarah Steele, who returned to Minnesota with Sibley. The two were married at Fort Snelling on May 2, 1843.

As a young child, Wahkiyee grew up among her Dakota kin where she learned to speak French. But in 1847, Sibley removed Wahiyee from her Dakota family to be fostered by William Reynolds Brown and his wife, Martha Newman Brown in the little village of Red Rock just south of St. Paul. Wahkiyee became Helen, and in the years following her adoption she was acculturated into Anglo-American society. For his part, Sibley “provided for his daughter financially, monitored her welfare, and maintained a relationship with her throughout her life.” After moving to St. Paul with the Browns, Helen was active in the Methodist church and often took part in social activities. In a 1908 newspaper, “old settlers” remembered her as “tall, pretty,” and “slender,” with a “sprightly intelligence,” and a “kindly, sunny disposition.” As a teenager, she was sent east to attend boarding school, an expense paid for by Sibley.

Helen Hastings Sibley (Wahkiyee). Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Helen Hastings Sibley (Wahkiyee). Image source: Wikimedia CommonsWhile it was publicly known that Sibley was Helen’s father, this fact was often hidden in legal documentation. After Helen met and fell in love with a New York physician, and a boarder of the Browns, Sylvester Sawyer, the two were married on November 3, 1859. Sibley attended the wedding and signed the marriage certificate as a witness, but the place on the document that listed the bride’s father remained blank. Many believed, including Sylvester, that Sibley’s wife, Sarah, strongly disapproved of his Dakota daughter.

After their marriage, Helen and Sylvester moved to Milwaukee and were reportedly very happy together. Helen soon became pregnant and, on September 4, 1860, she gave birth to a daughter. Tragically, hours after the birth she developed scarlet fever and died on September 6. She was just nineteen years old. The baby, who was born healthy, soon became emaciated and in pain. Though Sylvester was a physician, he could not save the baby who passed away on September 14. Helen and the baby were buried together in a cemetery in Raymond, Wisconsin. In response to Helen’s death, Sylvester noted that “he mourned her loss sincerely and truly.”

Wahkiyee, also known as Helen Hastings Sibley, lived a short and complex life in a changing, multicultural world. Like many born in that time period and in that region, she was the product of a system that saw the union of white and Native peoples as politically and economically advantageous despite whatever feelings, attraction, or other factors may have been involved. Henry Sibley may have cared for his daughter, and supported her financially, but he intentionally removed her from her mother’s culture, forcing her to acculturate into the dominant society while supporting her with money he earned by exploiting Native peoples. Helen Hasting Sibley, the first daughter of Minnesota, grew up with a cultural identity that was challenged in a society that, like her father, wouldn’t acknowledge her as whole. Despite that, she made a happy life for herself that was tragically cut short by illness, for her and for her daughter.

Sources:

Jane Lamm Carroll, “Who Was Jane Lamont?: Anglo-Dakota Daughters in Early Minnesota,” in Minnesota History, Issue 59, No. 5, (Spring, 2005), pp. 184–196. https://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/59/v59i05p184-196.pdf

Lois A. Glewwe, “Three Dakota Daughters – Nancy McClure, Julia LaFramboise and Helen Sibley,” Dakota Soul Sisters, Posted October 2, 2019, Accessed June 24, 2021, https://dakotasoulsisters.com/2019/10/02/three-dakota-daughters-nancy-mcclure-julia-laframboise-and-helen-sibley/

Bruce A. Kohn, Dakota Child, Governor’s Daughter: The Life of Helen Hastings Sibley, (Mendota, MN: Friends of the Sibley Historic Site, 2012).

Colin Mustful is a Minnesota author and historian with a unique story-telling style that tells History Through Fiction. His work focuses on Minnesota and surrounding regions during the complex transitional period as land was transferred from Native peoples to American hands. Mustful strives to create compelling stories about the real-life people and events of a tumultuous and misunderstood past.