Colin Mustful's Blog, page 4

April 12, 2024

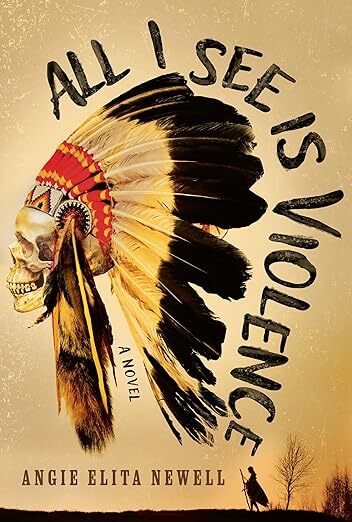

All I See is Violence by Angie Elita Newell – A Review

“I think of my life. Of wandering in a shrinking forest, game, berries, fish, growing less and less every year, and illnesses, illnesses we have never seen, rotting us from the inside out. I realize for the first time what it is like to live; before I only knew what it was like to try not to die.”

All I See is Violence by Angie Elita Newell is painfully honest. But, in its honesty, it offers a heartfelt, necessary, and brilliant story.

Told from three different first-person point of views, “All I See is Violence” seems to perfectly encapsulate the Native American experience. There is Nancy Swiftfox, a college professor and mother of four living near the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1972 during the height of the American Indian Movement. There is a General George Armstrong Custer, the American military hero fresh off the heels of political turmoil and dead set on restoring his reputation and ending the American Indian Wars. And then there is Little Wolf, a female hunter and warrior who lost everything and only seeks to hold on to her land and her heritage amidst the greed and death wrought by America’s Manifest Destiny.

“I understand right then what I think he meant. We are both Indians. Joshua can go home at night with the sense that he has real freedom. We, on the other hand, go to sleep every night with an ache and a longing in our soul for something we can’t even remember if we ever had—freedom.”

What I found striking about this novel was the author’s ability to tell a story filled with so much tragedy, so much death, so much reason to be angry and resentful, without anger and resentment. It is not gratuitous. It does not rely on clichés or dramatization. It relies merely on the author’s ability to tell a good story with sincerity, reaching deep within the human experience—deep within the Native experience—to pull out a true sense of grief and longing that may never be reconciled. Even Custer, who could so easily have been shown as the villain, is shown as a man who loves his wife, his brother, and acts according to the role he’s been given, brash as he may be. And the victims, Nancy and Little Wolf, are not exploited as helpless bystanders. They are seeking their own truths, their own happiness, their own answers. They don’t know where to find them, but they do not live in pity. They are genuinely seeking answers. They are genuinely, and perhaps tragically, human.

“There are only about fifty of us left. I see the bodies, all blue, all army blue, the color of freedom, the color of progress, lying on the hill of the ridge we’d just run up. The gunfire rings out, but not one bullet even comes near the Indian with the long golden hair. I waste three more shots as I watch him disappear. I look at Captain Keogh, who is standing next to me, his rifle at his side and the color drained from his face. I hear the war cry before I see what is coming. There are more Indians than I could have imagined. This dream I have, the dream of securing this land they waste, is turning into a nightmare.”

This is not a redeeming story by Angie Elita Newell. It ends with the line, “For all I see is violence, all I feel is pain and suffering, and all I hear is hate.” The Native warriors defeated Custer and the American forces at The Battle of the Little Bighorn, but it did not change the outcome for the Native people. Crazy Horse died a year later, and Sitting Bull died in 1890, both after being arrested by U.S. authorities. A century later, as Nancy Swiftfox’s story illustrates, the legacy of the American Indian Wars plays out all while groups like AIM continue the struggle to be free. And still the U.S. government holds on to the Black Hills, the land it stole outright. But this story is not meant to be redeeming. It is a story of suffering. It is a story of longing. It is a story that is brutally honest, simple, and true. It is a story about what it means to live in the shadow of genocide.

“I feel myself looking up at the sky. It is a clear blue, and I wonder why we are here. I wonder why we have to prove that we are worthy of our life to these people who have come from so far away. I wonder why they want our home so badly. I wonder why they don’t take their big boats and sail back to where they came from.”

March 13, 2024

Distrust and Retaliation: Tracing the Roots of the Arikara War

An Arikara warrior, by artist Karl Bodmer

An Arikara warrior, by artist Karl BodmerIn August of 1823, the U.S. Army, along with their Sioux allies, attacked villages of Arikara (Sahnish) located near the confluence of the Grand and Missouri Rivers. The attack was launched in response to an attack led by the Arikara on a group of fur traders months earlier. Called the Arikara War, it marked the first time in which the United States Army was deployed for operations west of the Missouri River on the Great Plains.

The origins of the Arikara War can be traced back to 1805, when the Lewis and Clark expedition passed through Arikara lands. While the expedition was preparing to continue west from Fort Mandan, they were met by a group of Arikara who said they were considering relocating near the Mandans and Hidatsas for the benefit of mutual protection. They also said that they wished to travel to Washington D.C. to meet with the President.

An Arikara expedition to Washington D.C., led by Ankedoucharo, was quickly arranged. The Arikara expedition arrived in Washington in February 1806 and met with President Thomas Jefferson. They continued on to Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. But then, on April 7, 1806, Ankedoucharo died of illness. President Jefferson quickly composed a letter of condolence to the Arikaras over the loss of their leader, but the Arikaras believed the death had not been properly explained. This set off a period of mistrust between the Arikaras and the United States Government.

“He (Chief Ankedoucharo) consented to go towards the sea as far as Baltimore and Philadelphia. He said the chief found nothing but kindness and good will wherever he went, but on his return to Washington he became ill. Everything we could do to help him was done but it pleased the Great Spirit to take him from among us. We buried him among our own deceased friends and relations. We shed many tears over his grave.”

President Jefferson’s eulogy to the Arikara over the death of their leader, Ankedoucharo

By 1823, the Arikara could no longer depend on their traditional lifeways of agriculture and hunting for their survival. Like many Native American tribes, their numbers dwindled due to disease and they became more and more dependent on non-traditional trade networks provided by large fur trading companies. At the time, General William Ashley of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was setting up a huge trapping and trading network that relied on the transportation of the Missouri River. The Arikara asked Ashley to set up a permanent post near their settlements, but Ashley said he would only ship goods up the Missouri from St. Louis, essentially cutting the Arikara out of the trade network and threatening their survival. It seems that the Arikara may have also resented the fact that the Sioux, their traditional enemies, had such trading posts while they did not.

Then, on June 2, 1823, the Arikara attacked boats belonging to General William Ashley. The Arikara killed between fourteen and twenty trappers, wounding several others, and taking all trade goods from the boats. This attack was portrayed in the 1954 biographical novel Lord Grizzly by Frederick Manfred and then later in the 2015 film The Revenant. The U.S. responded in August of 1823, sending Lieutenant Colonel Henry Leavenworth and a combined force of 230 soldiers of the 6th Infantry, 750 Sioux allies, and 50 trappers and other company employees. On August 9 an assault of Sioux cavalry was launched against the Arikara. The initial assault was successfully repelled by the Arikara and on August 10 Leavenworht ordered a military bombardment. When this was ineffective, Leavenworth ordered an infantry attack. All attacks failed and on August 11 Leavenworth negotiated a truce with the Arikara. But, that night, fearing another attack, the Arikara left their village and the following day it was burned to the ground by resentful members of the Missouri Fur Company.

Hostilities between the U.S. and Arikara officially ended on July 18, 1825, when a peace treaty was signed between the two nations. Although the conflict was brief, it was representative of the growing conflicts and changing alliances that would lead to the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 and the Sioux Wars that followed.

Sources:

Wikipedia contributors, “Arikara War,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Arikara_War&oldid=1211808759 (accessed March 12, 2024).

Wikipedia contributors, “Arikara,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Arikara&oldid=1204765265 (accessed March 12, 2024).

“Section 4: The Arikara War,” North Dakota Studies, https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content... (accessed March 12, 2024).

February 6, 2024

Update on the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant: New Direction and Continued Commitment

Dear Donors, Supporters, and Friends,

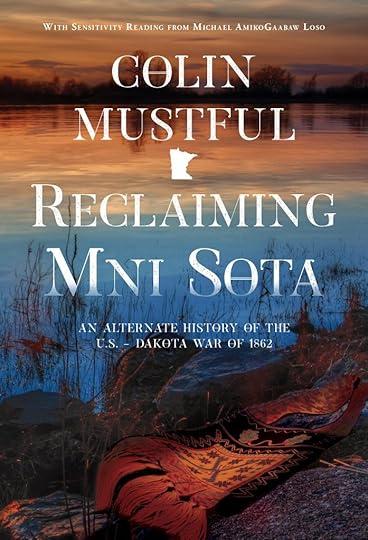

I want to update you on the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant. Launched on June 15 last year, this initiative aimed to support one Indigenous writer from Minnesota with a $10,000 grant, connected to my novel Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. It was part of a broader effort to address a history of inequality.

Despite facing criticism from some Native American community members, we pressed on, believing in the positive impact of the novel and the grant. Thanks to you, we raised $6,467 by the end of the fundraising period. However, there were no applicants for the grant. As a result, we donated the funds to Indigenous Nations Poets, who later returned the donation, stating only, “We’re returning this money because we’re uncomfortable with the manner and circumstances under which it was collected.”

Respecting their stance, my Native colleague Michael AmikoGaabaw Loso and I looked for another recipient. I’m pleased to say that after speaking directly with their chief financial officer, the American Indian Community Development Corporation (AICDC) in Minneapolis has agreed to accept the funds. While AICDC isn’t focused on literature, it does crucial work with housing and homelessness for Native communities.

Before making the donation, I’ll reach out to each donor about this change and offer a refund if preferred. Then, on Monday, February 12, I’ll donate any remaining funds to AICDC.

Thank you for your support. Although things didn’t go as planned, I’m confident these funds will still benefit Native Americans in Minnesota. This experience has been educational, and I’m committed to honoring our shared history and supporting Native communities now and in the future.

January 20, 2024

Settler Colonialism – Who’s to blame for a system of genocide?

A homesteading family pictured in 1886. Courtesy of the National Archives.

A homesteading family pictured in 1886. Courtesy of the National Archives. In 1850, the white population of Minnesota was 6,077. Ten years later the white population ballooned to 172,023. Ten years after that it grew to 439,706. The people who poured in from the eastern United States and Europe are often called settlers. They are called settlers because they settled upon a land that was new or foreign to them. But that is only half of the story. By settling on the land they also displaced the Native populations already residing there. That makes them settler-colonists.

The term settler-colonialist is relatively new and can feel like an abrasive term for those whose ancestors did the colonizing. By labeling a white settler as a settler-colonialist it can feel like they are being accused of intentionally harming Native populations—like they are being accused of stealing their land. But the reality is far more nuanced and cannot be pinned on any one person for any one reason. Settler-colonialism was a structural, institutional practice that took place over decades and involved a system so large that no one settler should be assigned guilt for the resulting displacement of Native peoples and culture.

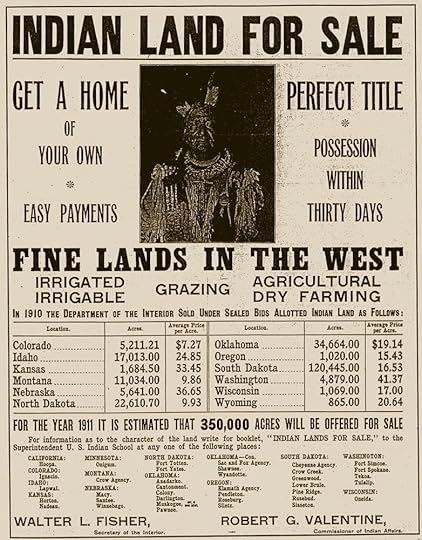

Advertisements like this one drew settlers west.

Advertisements like this one drew settlers west.In my novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota, I’ve created a fictional family of white settler-colonialists. They live in a small log home in Londonderry, Vermont, and they attribute their homestead to a reward given to the family’s paternal great-grandfather for fighting in the American Revolution. The family uses their homestead to grow a small amount of cash crops, and produce eggs, maple syrup, and goat cheese. The father, Randolph, and his son, Samuel, also work at the local saw mill. But when Randolph is badly injured and unpaid bills pile up, the family begins to worry about their livelihood and future. This is when Samuel has an unsuspecting run in with Mr. McPherson, a land management officer who tells Samuel about the beautiful, arable, and open land in the new state of Minnesota. With the promise of land, opportunity, and a better future, Samuel and his family follow in the footsteps of other Vermont families and head west.

In the mid to late 1800s, the story was the same for millions of American migrants and European immigrants—tough times and the promise of wealth and opportunity prompted them to seek a new life in a new land. Moreover, they were encouraged to head west by the capitalist United States government. White settlement meant economic growth and economic growth meant power and influence. The United States government sought to imperialize the entire land mass from east to west no matter who or what stood in their way. The economic motivation to settle the land eventually became an ideology known as Manifest Destiny—the idea that the United States is destined by God to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire North American continent.

Settler-colonialists could not see beyond their own livelihoods. They were not wealthy or educated and had few opportunities outside of working the land. They sought only what was promised to them and they went about it with hard work and sacrifice. This is what I attempted to show in my novel. That is not to say that settler-colonialists were blameless. Many of them were ruled by greed and knew they were enriching themselves at the expense of others. But within the context of their daily lives it was impossible to see the scope of their decisions or to comprehend injustices created by their own existence.

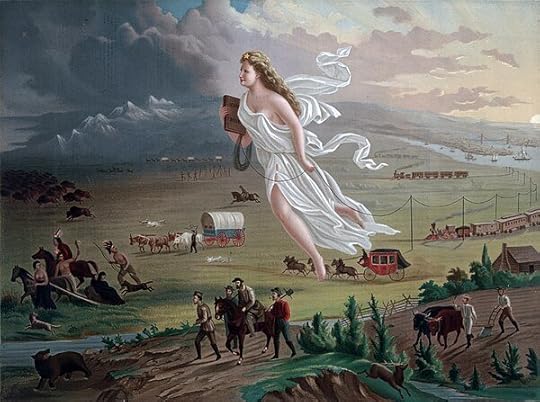

American Progress by John Gast, 1872

American Progress by John Gast, 1872Settler-colonialism equals genocide. It equals the removal and replacement of Indigenous populations and the annihilation of their culture and way of life. But it is not done by the settler and her or his family. It is done by a capitalist system, developed over centuries and institutionalized into the gears of society. It is a form of imperialism and it is justified by valuing the needs of one group of people over the needs of another. It is done by valuing wealth and power over the basic humanity of those in the way of wealth and power. It is incredibly destructive and its effects have shaped the world we live in today. It has created the imbalance of wealth and opportunity that have become so commonplace that they are hard to recognize.

Acknowledging Samuel and his family as settler-colonialists is not an indictment. It does not make them bad people for seeking a better life. If I’ve written the characters of my novel well enough, it should show their innocence within a system designed to exploit them and their dreams. We are all victims of settler-colonalism, white and Native, rich and poor. We are all part of the system. What’s important, is to step outside of ourselves and look objectively upon the roots of society. How did we get to where we are today and what role do I and my ancestors play within that world? To start…just read. Read about the people that came before you and empathize with their circumstances—with their world. Take yourself out of the picture and recognize the harm settler-colonialism has done and continues to do. Then, move forward, making the world a better place.

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

January 5, 2024

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Update (December)

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

December 2023

Sales of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 26 = $26

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $8.40

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – 0

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $34.40

Thank you to our December donors!

Sandra Jackson-Opoku

Kristin Blomme

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant. The fundraising and application periods for the grant are now closed. Although our $10,000 goal was not met, we did raise $6,467 to support literary diversity.

Unfortunately, there were no applicants for the grant. As a result, we have decided to donate the funds to Indigenous Nations Poets, a national Indigenous poetry community dedicated to mentoring emerging writers and promoting Indigenous poetic practices. They also aim to raise awareness of Native Writers past, present, and future. While we fully support the work of Indigenous Nations Poets, we understand that this was not the original plan for the funds. We wanted to inform you, our generous donors and supporters, about this change in destination for the grant contributions.

If you donated to the grant and would prefer a refund, please contact Colin Mustful at mnauthor@colinmustful.com before Friday, January 12. After this date, all remaining funds will be donated to Indigenous Nations Poets. Thank you once again for your support of the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant. Though we did not reach our ultimate goal, we made significant strides in supporting Indigenous writers and storytelling. We remain committed to contributing to a more diverse literary community in the future.

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

Learn MoreDecember 13, 2023

A History That Remains Overlooked – The U.S. – Dakota War of 1862

On December 26, 1862, thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, for their roles in the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. Today, at the site of the hanging, this heartbreaking event is commemorated by the statue of a buffalo on Riverfront Drive in downtown Mankato called Reconciliation Park. In the 161 years since it happened, the U.S. – Dakota War and the hangings that followed have been studied, written about, discussed, and commemorated in countless ways. Hundreds of books, both fiction and nonfiction, now tell the tale of the U.S. – Dakota War while in sixth-grade social studies classes students across the state of Minnesota are required to learn about the people and events involved in the war. For certain, there is no shortage of information about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.

I first discovered the U.S. – Dakota War in 2007 while studying history at Minnesota State University in Mankato. While I was shocked by the events, I was surprised that I had not learned of them before. How, in all my years of education, in all my years as a Minnesotan, had I not learned about the war, the hangings, or the exile of Dakota people that followed shortly thereafter? I was both alarmed and curious which led to my own years of research and writing about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. Yet, after recently publishing my fifth novel related to the displacement and mistreatment of Native peoples in 19th-century Minnesota, it is apparent that most Americans still know little to nothing about this history. While my novels delve deep into the reasons, context, and outcome of the war, I’d like to take a moment to provide readers with a very brief history of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.

This scroll at Reconciliation Park in downtown Mankato, lists the names of the men who were simultaneously hanged there on December 26, 1862. Photo taken at the annual commemoration event on December 26, 2022.

This scroll at Reconciliation Park in downtown Mankato, lists the names of the men who were simultaneously hanged there on December 26, 1862. Photo taken at the annual commemoration event on December 26, 2022. To begin, it’s important to understand that the region now known as Minnesota is the homeland of the Dakota people. The word Minnesota itself is derived from the Dakota phrase Mni Sota, meaning “Land Where the Water Reflects the Clouds.” The Dakota consider the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, located between the present-day cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, a sacred place called Bdote. It is, as noted by the Minnesota Historical Society, their “sacred place of creation, identifying themselves as the Wicahpi Oyate (Star Nation) who originated in the sky and came into being on this land.”

The origins of the U.S. – Dakota War can be traced back to 1805 when Lt. Zebulon Pike met with Dakota leaders at Bdote and negotiated a treaty. With the agreement of just 2 of the 7 Dakota leaders gathered there, Pike negotiated the sale of 100,000 acres of land surrounding the confluence for the U.S. to build a fort and promote trade. While the treaty valued the land at $200,000, years later the U.S. Senate agreed to pay just $2,000. This would prove to be the first of many treaties made by the U.S. government with the Dakota people that was fraudulent and deceitful.

Treaty of Traverse des Sioux by Francis Davis Millet

Treaty of Traverse des Sioux by Francis Davis MilletJumping ahead to 1851, two years after Minnesota became a territory of the United States, U.S. government officials and fur trade associates negotiated the sale 24 millions acres of land west of the Mississippi River from the Dakota in exchange for $3,750,000 (estimated at 12 cents per acre), to be paid over decades as annuities or annual cash payments. In addition, the Dakota agreed to remove from their lands and live on a “permanent” reservation along the Minnesota River Valley. For the U.S. this accomplished many things: it allowed traders to be paid off for the debts they incurred from trade with the Dakota, it opened the land for white settlement, and it was the first of many steps in an attempt to acculturate Dakota people into white Euro-American society. It should also be noted that while a treaty is generally considered as an agreement made between two sovereign nations, the Dakota had been coerced into signing treaties through years of manipulative policies and practices that left the Dakota with few options. For a specific example of this, read more about the Trader’s Paper.

Reservation life was hard on the Dakota people. Forced to adjust from living semi-nomadically to living permanently in one place, the Dakota were also forced to speak English, practice Christianity, cut their hair, till the soil, and change their style of dress. Many Dakota resisted the changes causing factionalism among those who wanted to maintain their traditional lifestyle and those that were pressured into agreeing to making changes and becoming farmers. Additionally, the white population of Minnesota exploded, especially after it became a state in 1858, forcing the Dakota to give up more land, further infringing upon their space and way of life. Lastly, debts between the Dakota and traders/merchants continued to increase as businessmen exploited the treaty system to enrich themselves and impoverish the Dakota.

Andrew Myrick was a trader who was among the first killed at the outbreak of war. He’s known for having said of the starving Dakota, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung.”

Andrew Myrick was a trader who was among the first killed at the outbreak of war. He’s known for having said of the starving Dakota, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung.”By 1862 the Dakota were nearly destitute, hemmed in on all sides by white settlement. The summer was dry, making food scarce. In addition, the Dakota’s anticipated annual cash payment was delayed by many weeks. Uncertainty over the late payment prompted traders to deny the Dakota goods on credit. Without access to food or credit, by August of 1862 the Dakota people were in an increasingly desperate situation. All of this contributed to the decision of a faction of the Dakota, led by Little Crow and known as the Soldiers’ Lodge, to launch an attack against the white settlers, traders, and government agents living at the Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 1862.

The attack took the white settlers, who considered the Dakota as friendly neighbors, by surprise. Panic swept throughout the settlements near the reservation as Dakota soldiers killed or captured hundreds of white Minnesotans. Following the initial attack, the Dakota launched two separate attacks on New Ulm and Fort Ridgely while also attacking settlements as far away as Lake Shetek. Meanwhile, groups of farmer Dakota who were not in favor of the war, protected groups of white settlers, bringing them to safety or ensuring they were not hurt while being held captive. They also sought to negotiate with the Soldiers’ Lodge for an end to the violence.

However, the Soldiers’ Lodge faced little resistance until, in late August, Colonel Henry Sibley, former governor of Minnesota, led an army of volunteer militia south from Fort Snelling to quell the violence and rescue the captives. Sibley’s presence forced the Dakota to make a hasty retreat and re-establish their camp northwest of the Upper Sioux Agency. On September 2-3, in what’s known as the Battle of Birch Coulee, the Dakota successfully pinned down for more than thirty hours a burial party of U.S. soldiers but were again forced to retreat when U.S. reinforcements arrived with cannons. Finally taking pursuit of the Dakota weeks later, Sibley and his soldiers met the Dakota on the battlefield on September 23, in what’s known as the Battle of Wood Lake, and defeated them within a few hours. Days later, Sibley marched into the Dakota camp, released the captives, and detained any Dakota who had not already fled.

The war was followed by the Dakota War Trials, a hastily established military commission led by Henry Sibley. In just over a month’s time, Sibley and his commission put more than 400 Dakota on trial for their roles in the U.S. – Dakota War. If the Dakota admitted to having shot a gun or having been present at a battle, they were determined to be guilty and sentenced to death by hanging—303 Dakota received such a conviction while sixteen others were given a ten-year prison sentence. The trial proceedings were forwarded to Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States at the time, for review and approval. Lincoln approved forty of the death sentences declaring that he was “anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other…” Two more sentences were later reprieved. Then, at 10am on the morning of December 26, 1862, thirty-eight Dakota men were simultaneously hanged in Mankato, Minnesota while thousands of onlookers gathered to witness the event. The hanged men were buried in a shallow grave near the river bank and most were quickly dug up and stolen by physicians for use as medical cadavers.

Photo of the Fort Snelling Internment Camp where nearly 1700 Dakota people were held during the winter of 1862/63.

Photo of the Fort Snelling Internment Camp where nearly 1700 Dakota people were held during the winter of 1862/63. Meanwhile, the majority of the Dakota people, numbering 1,658 mostly women, children, and the elderly according to the Minnesota Historical Society, were sent to Fort Snelling where they were held in a concentration camp just below the fort. Conditions at the camp were poor and an estimated 130-300 Dakota died while being held there.

Then, in February and March of 1863, by acts of Congress, all previous treaties made with the Dakota were abrogated and the Dakota and Ho-Chunk were forced to remove from beyond the borders of the state by law forever. In May 1863, all Dakota survivors were packed aboard steamships and sent south down the Mississippi River and then northwest along the Missouri River where they were resettled at the Crow Creek Reservation, many of them never to see their homeland again.

This has been a very brief summary of the U.S. – Dakota War. For more detailed information, I highly recommend visiting https://www.usdakotawar.org/, a website published and maintained by the Minnesota Historical Society. For a historically detailed but fictional view of the conflict that will put you in the minds of the whites and Natives during the time period, I hope you’ll consider reading my novel Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.

“Reclaiming Mni Sota is a well-researched and impassioned tale of an unlikely friendship between two men: Waabi, an Ojibwe destined to reclaim his people’s land, and Samuel, a white farmer from the infant United States seeking a better life on the frontier. A painful, heart-wrenching, yet triumphant read, this is an alternate history in which Mustful paints the ending this country needed, and the Native population deserved.”

– Lindsey S. Fera, Historical Fiction Author

Get a signed copyDecember 5, 2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Update (November)

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction, are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

November 2023

Sales of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 173 = $173

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $46.20

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – $3200

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $3,419.20

Live Fundraiser and Silent Auction Contribution Total – $640

Thank you to our October donors!

Anonymous

Lyn Glenn

Paulette Hughes

Fundraising for the grant ends December 31 and we ask everyone to please consider making a contribution to help us reach our $10,000 goal! As fundraising comes to a close, regardless of whether or not we reach our goal, we will begin reaching out to eligible applicants, letting them know about this fantastic opportunity to receive funds and mentorship that can help them tell their invaluable stories. If you know any writers from the Minnesota Indigenous community, please reach out to them and encourage them to apply.

Current Fundraising Total = $6,322

No Donation is too small!

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

November 15, 2023

What’s in the Body Bag?

Though it’s not my typical genre, I recently had the pleasure of reading What’s in the Body Bag, a collection of dark fiction that dares readers to delve into the strange, the dark, the funny, and the off-kilter stories of troubled characters who just don’t know when to leave a good body bag alone. The collection, which comes out on Kindle on November 16, was written and published by the Dead Birds Writing Group. This fabulous writers group originates from the Augsburg University MFA program, the same program I graduated from. The collection of nine stories is a quick, fun read to be enjoyed on a cold, dark winter’s night. So grab a cup of hot cocoa, put on your slippers, cover yourself in a warm blanket, and get comfortable for these drama-filled anecdotes that keep your heart racing as you ask yourself the same question the characters do—What’s in the body bag!?

Kitchen Encounters by Judy Niemi Johnson

A woman comes home to discover her husband is a murderer—or is he the one who was murdered!? Panic sets in as she wonders if she could be next.

In Passing by Amy Dahl

At Geezer Glen dead bodies just come with the territory. But not this dead body! What was supposed to be just another trip to the morgue turns into a startling (and deadly) revelation.

Truth or Dare by A.M. Symes

Envy can motivate people to do some terrible things. But it’s game night, and nothing bad could happen at game night. Or could it?

Spirit of Savannah by Trena Bolden Fields

An enchanting evening in Savannah takes an unexpected and tragic turn. What should have been a celebration is anything but.

Catatonic Survival by David Nash & L.E. Schwaller

With the vibes of Happy Death Day, poor Megan can’t seem to escape her own death. That is, until she learns the truth about her life.

Saturday at the Morgue by Jayne Carlson

A character-driven tale reminiscent of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a plague slowly overtakes the human race. When a curious mortician finally discovers it source, it may be too late.

Bottom Half of the Watch by Jon Dahl

A series of midwestern earthquakes opens the earth, releasing mysterious species into the world. But is the species friend or foe?

Killer Wives Club by Michelle I. Linder

Everyone needs a support group, even serial killers. But this support group has a shocking twist—a twist the local detective wishes he never found out.

Group Exorcise by Andrew Marks

An exorcism gone wrong, a young Catholic priest tries to cover things up, only to make matters much, much worse. In this story, it is the dead that have the final say.

November 3, 2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Update (October)

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction, are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

October 2023

Sales of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 127 = $127

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $29.40

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – $50 (payment for the book tour I’m doing is forthcoming)

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $206.40

Thank you to our October donors!

Wheels Across the Prairie Museum

Anonymous

Eileen Sanchez

Teresa and Grant Fogle

Anonymous

While we’re still a long way from our goal, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction are proud to announce our upcoming Silent Auction & Live Fundraiser benefiting the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant. On October 10, corresponding with the official book launch of Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, History Through Fiction is opening bidding for a Silent Auction featuring more than 40 items ranging from author signed books, to book marketing services, to Zoom consultations, and more! Then, on Friday, November 3, at 7pm US Central Time, Colin Mustful is hosting a 24-Live Zoom Fundraiser that includes interviews with more than 30 special guests. The live event ends with the announcement of the winners from the Silent Auction from 6-7pm on Saturday, November 4. Registration for the live fundraiser is FREE.

Current Fundraising Total = $1,638No Donation is too small!

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

October 10, 2023

Thank You For Your Tips: A Pizza Delivery Driver’s Expression of Gratitude

Delivering a pizza is not a complicated task. I put a cardboard box into a bag, I drive that bag over to your house, I walk up to your door, probably say “hi” to your dog, pull the cardboard box from the bag, hand you the cardboard box, say “thank you”, and drive back to the restaurant. Most of the time, these days, there’s not even an exchange of money. Simple, easy, done. I may never see you again and you may never see me again. And yet, there’s a lot more to it than that.

It was 1998.

A new mini-mall was being built just a mile up the road from where I lived. Within that mini-mall was a Papa John’s Pizza. I was sixteen years old. I knew that I liked pizza. I didn’t really want to return to my job as a grocery bagger at King’s IGA, so I applied at Papa John’s. I got the job. I was hired as an instore—answering phones, making pizza, cleaning up after dinner rush. I enjoyed it. I liked the people I worked with, I loved the camaraderie and teamwork, I enjoyed the fast-paced nature of dinner rush, and I did really like the pizza. So I continued working there throughout high school. What I didn’t know was that twenty-five years later, I’d still be working at a pizza restaurant at a position with no more distinction than the one I started with.

It was 2007.

I was working as a shift lead at Papa John’s Pizza in downtown Mankato, Minnesota, while studying for a Master of Arts in history. Not far from the restaurant, maybe just a few blocks, there stands a large stone sculpture of a bison. Known as Reconciliation Park, the bison commemorates the hanging of thirty-eight Native Dakota Indians in Mankato on December 26, 1862. The hanging, the largest simultaneous mass hanging in U.S. history, was one of the immediate results of the U.S. – Dakota War which also included the exile of all Dakota and Ho-Chunk people from the state of Minnesota in 1863. This was the first time I’d ever heard of it. As someone who studied the genocide of Western Indigenous people, I was shocked to find out what happened in my own home state. And I was shocked that I had never learned of it before then. Over the next decade and a half, I would dedicate much time to researching and writing about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862.

It was 2010.

A picture of me in the Slice costume outside Papa Johns in Columbia Heights, MN, circa 2010

A picture of me in the Slice costume outside Papa Johns in Columbia Heights, MN, circa 2010I was working as a shift lead and delivery driver for Papa John’s Pizza in Columbia Heights, a parking lot attendant at Andover High School, and a high school soccer coach. Three years out of graduate school I still hadn’t found a job with my degree. I decided to write a novel—a novel about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. I was ambitious and I needed to try something new. I also wanted to find a way to teach others about the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, to share with them the tragic history that had been kept from me. It would take hard work, but maybe it would be my big break?

It was 2012.

I was working as an in-store and shift lead at Papa John’s Pizza in downtown Washington D.C., a grocery manager at a corner bodega on Rhode Island Ave, and an unpaid intern at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. A year and a half earlier I had finished writing my novel, and sought its publication, but nothing came of it. I had taken the internship at the Holocaust Museum believing that, at twenty-nine years old, an internship might jump start my career since writing a novel had not accomplished that. Unfortunately, it did not. However, a few months after completing the internship, a new opportunity arose.

A photo of my desk at Holocaust Museum offices in Washington, D.C.

A photo of my desk at Holocaust Museum offices in Washington, D.C.It was the fall of 2012.

I was working as the grocery manager at a corner bodega, refereeing high school soccer, and working as an instructor for a program called Soccer Shots. It was one of the rare moments in my life when I was not working in food service. I remember the moment distinctly. I was working alone at the corner bodega when I received a contract offer from Tate Publishing. I was thrilled. Ecstatic. Overwhelmed with excitement. According to the contract, Tate was going to dedicate $27,000 toward the publication and marketing of my novel. This was it, I’d finally gotten my big break. I would never have to return to food service again. If Tate Publishing was willing to invest $27,000 toward the publication of my novel, I reasoned, they must think it’s going to sell. A year later, in October 2013, my novel, Thy Eternal Summer, was published.

It didn’t sell. It didn’t change my life. I didn’t have any events or interviews. Outside of my own family, no one even knew I had written and published a novel. Not only that, but I was out $4,000. According to the contract, Tate required a $4,000 retainer that would be paid back after the book sold 1,000 copies. Unfortunately—and I didn’t realize this at the time—the only books that would count toward that quota were those books that were sold through distribution, not the ones that I bought and sold in-person. Tate never intended to market my book to a potential audience of readers. They only marketed it to me, explaining that I would earn more money if I bought the book from them first and then sold it at in-person events. Tate Publishing, as I eventually learned, was a Vanity Press. I would never see my $4,000 again.

Although my experience with Tate Publishing was a negative one, it was one of those formidable experiences, like the one I had in 2007, that led me to where I am today. The experience motivated me to learn more about what it means to write and publish a novel—what it means to identify my target audience, to establish an online presence, and to market myself and my book. It was with these lessons that I moved on to write my second novel, Grace and Spirit Lake, a follow-up to Thy Eternal Summer that also dealt with the history of the U.S. – Dakota War, an event that, as I was learning, was much more complicated and complex than I originally perceived. While my research continued teaching me more about this history, it was my everyday life that taught what it means for us today along with my role in both experiencing history and contributing to it.

It was 2014.

I think. I was working as a delivery driver for Jimmy Johns in Northeast Minneapolis and a delivery driver for BiteSquad across the Twin Cities. I went to Birchbark Books, a Native-owned bookstore in Minneapolis, with a copy of my novel Thy Eternal Summer. It should be noted that this was not just any Native-owned bookstore, it was owned by Louise Erdrich, one of the most accomplished Indigenous writers of our time. I’m not sure what I expected when I went there, but I thought perhaps Birchbark Books would be interested in carrying my title on their shelves. At the time I knew nothing of traditional distribution and the various proper channels to get your book discovered by bookstores. I just went straight up to the counter with a copy of my book in hand and told the clerk about what I had written. They politely turned me away. But, the clerk allowed me to linger—to state my case—perhaps recognizing that I was well-intentioned though overly naïve. At that moment Louise Erdrich herself walked up to the counter and pointed to the word ‘Conflict’ in the subtitle and said, “There’s your first problem. From the perspective of the Dakota, this was considered a war.”

This was another formidable moment. With this experience, this moment, I learned many things. First, as I already mentioned, I learned that there are more proper, traditional channels to expose my work to bookstores rather than just bombarding them in the middle of the day. Second, I learned about my position on the writing ladder. Honestly, I didn’t know much about Louise at the time. I didn’t know about the demands on her time, knowledge, and experience. I didn’t even know if she was Dakota or Ojibwe. And third, I learned about my limited viewpoint. When writing about the U.S. – Dakota War, I had only emulated what I had seen from hundreds of white writers before me. I had only relied on my cultural and religious background as Christian, white-American living in the 21st century. I hadn’t even thought to filter history from outside of my own immediate understanding. I hadn’t thought of calling it the U.S. – Dakota War instead of the U.S. – Dakota Conflict.

It was late 2015.

I was working as the pizza chef at Stratton Mountain Resort in Vermont. To receive better cell reception, I drove to the parking lot of the Londonderry Village Market where I parked in order to call my editor about my newest novel, a manuscript about the 1851 treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota called Ceding Contempt. A month earlier I had responded to my editor’s comments and constructive criticism with a litany of questions. Why do I need to do this? Why do I need to change that? I didn’t understand why my editor wanted me to change so much of the content of my manuscript. In response, my editor said that I was being ‘hostile’. Clarification was necessary and a phone call was the only way to do that. The phone call, which ended cordially, was another formidable experience, one that taught me once and for all that although I understood history, I did not understand the craft elements of fiction—I did not understand the science of storytelling—in order to effectively convey history to readers. I needed to go back to school. I needed an MFA in creative writing.

My co-workers making pizza dough at Stratton Mountain Resort in Vermont, 2016.

My co-workers making pizza dough at Stratton Mountain Resort in Vermont, 2016.It was the summer of 2004.

I was working at Papa John’s Pizza in Champlin before returning to school for my senior year of college. By this time I had six years’ experience at Papa John’s and my general manager Craig asked if I’d like to manage my own store. My answer was an obvious and resounding ‘no thank you’. Working in the restaurant industry was temporary and I only wanted to stay there long enough to get me through college. It’s always been temporary until something else comes through. It’s not as though I haven’t tried to find a more permanent solution. Over the years I’ve applied for hundreds of positions adequately suited to my educational background and professional skill sets. These include jobs with titles such as Research Associate, Editorial Assistant, Adjunct History Instructor, Production Editor, Historical Interpreter, Writing Tutor, Site Guide, Program Manager, Acquisitions Editor, Adjunct English Instructor, Indian Education Advisor, and the list goes on, and on, and on. While attending Augsburg University I regularly worked with counselors at the Strommen Career Center to revise my resume and prepare me for interviews. I worked briefly with a life coach. I hired a career counselor from LinkedIn. Most recently, I’ve been working with a volunteer mentor from the SCORE business office. And yet, every Saturday night you’ll find me walking up your front step to hand off a hot, delicious pizza so that I can supplement my income while I pursue my passions and interests—while I apply myself to something more.

It was October 2018.

I was working as a delivery driver at Parkway Pizza, a Special Ed Para at STEP in Anoka, and a high school soccer coach at St. Francis High School. I was also in my second year of my MFA program at Augsburg University and had just started writing what would become my most recent novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. The novel began as a short story in which a white settler and an Ojibwe soldier happen upon each other in the midst of battle only to find that they share a common bond. Eventually, they befriend each other. The story was a stretch for me because all of my previous fiction writing was based strictly on real historical happenings. I was challenging myself to do something more than just write history. However, when I shared the story with my assigned mentor, his feedback was not only negative, it was startlingly critical. My mentor expressed that my writing had no redeeming qualities while pointing out my biased, ethnocentric point of view. He said that I needed to learn how to write, but learning how to write within someone else’s culture was not the place to do so. He ended with an ultimatum: write about something other than Native history or find a new mentor.

Hurtful as it was, my mentor’s criticism held within it important lessons while also providing the catalyst to move my writing and publishing journey forward. It challenged me to examine and re-examine who I am and why I view the world the way I do. It helped me to recognize the power of storytelling and the role I play in contributing to a very narrow viewpoint that has been perpetuated from generation to generation. It helped me to write my novel with empathy and true care for the connection the past has with the present.

It was 2019.

I had just earned my MFA and was still working as a delivery driver at Parkway Pizza. I decided to create and launch my own press, History Through Fiction. Combining my integrity for the historical process and my new knowledge of the craft elements of fiction, I launched it with the belief that historical fiction can and should have some component of traditional nonfiction historical texts. That is, historical fiction authors should be transparent about what’s fact and what’s fiction by including things like footnotes, a bibliography, endnotes, recommended resources, or even just a detailed author’s note. I’m incredibly proud of my press and how it’s grown over the years. I’m also proud of the way I have combined my interests, experience, and education to create something meaningful, entertaining, and, hopefully, lasting. But none of this has managed to divorce me from my reliance on your generosity—on your tips. My company’s expenses exceed its revenue by about $15,000 to $20,000 a year, approximately the same as my annual income as a pizza delivery driver.

It is 2023.

We all have dreams and ambitions. We have talents and skills. We all have a handful of formative experiences and another handful of experiences that, for better or worse, led us down one particular path or another. I write this not as a complaint about my years in the food service industry or as a grievance over my inability to find meaningful employment that pays a living wage. I write this to show myself to you—an entrepreneur operating a historical fiction press out of the corner of his studio apartment in Roseville, Minnesota. I write this to say thank you. I’ve delivered pizza through heatwaves and cold snaps. I’ve opened the door to restaurants to begin prep before the sun comes up and I’ve walked home at four in the morning through the streets of Washington D.C. after closing down the pizza shop following bar rush. I’ve washed countless dishes, taken out countless trash bags to the dumpster, put thousands upon thousands of miles on my car, and answered the phone to take your order so many times that I could practically do it in my sleep. So, when I arrive at your door with your pizza, wings, and maybe a pint of ice cream and say thank you, I mean it. Thank you for your tips. They have sustained me through college, graduate school (twice), the publication of five novels, and the creation and operation of my own literary press. I don’t know where my dreams and passions will take me, but I know that I couldn’t even hope to achieve them without your generosity. Thank you for your tips.

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.