Colin Mustful's Blog, page 5

October 3, 2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Update (September 2023)

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction, are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

September 2023

Pre-Orders of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 160 = $160

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $21.00

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – $100

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $281.00

Thank you to our September donors!

Mark Mustful

Anonymous

Lynn McDonough

Anonymous

Anonymous

Anonymous

While we’re still a long way from our goal, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction are proud to announce our upcoming Silent Auction & Live Fundraiser benefiting the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant. On October 10, corresponding with the official book launch of Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, History Through Fiction is opening bidding for a Silent Auction featuring more than 40 items ranging from author signed books, to book marketing services, to Zoom consultations, and more! Then, on Friday, November 3, at 7pm US Central Time, Colin Mustful is hosting a 24-Live Zoom Fundraiser that includes interviews with more than 30 special guests. The live event ends with the announcement of the winners from the Silent Auction from 6-7pm on Saturday, November 4. Registration for the live fundraiser is FREE.

Current Fundraising Total = $972No Donation is too small!

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

September 12, 2023

Cut from the Novel – A Chapter Excerpt from Reclaiming Mni Sota

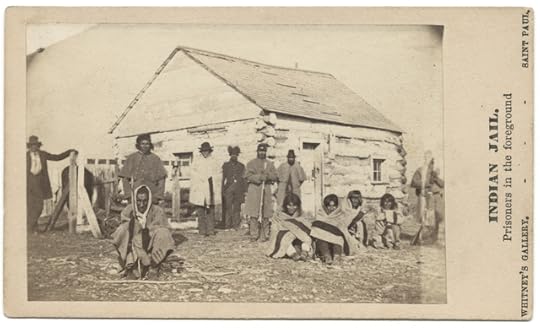

Dakota people held as prisoners following the U.S. – Dakota War. Image from MNHS Collections.

Dakota people held as prisoners following the U.S. – Dakota War. Image from MNHS Collections. Following the conclusion of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, a military commission of five U.S. army officers was established to put on trial those Dakota men, and one woman, who had been captured or surrendered and were suspected of being participants in the war.. The commission, led by Henry Hasting Sibley, worked quickly, trying 391 cases between September 28 and November 3. Of those 391 cases, 303 Dakota men were determined to be guilty of murder or “other outrages”. Most of those cases lasted less than five minutes, the Dakota had no one to represent them, and most were determined to be guilty for admitting to being present at a battle of having shot a gun. The trials were conducted in haste and without any consideration for the rights of the defendants. (Sourced from The Infamous Dakota War Trials by John A. Haymond)

In my novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota, I attempt to illuminate the wrongs done to the Dakota, Ojibwe, and other Native peoples by having those same wrongs done to the white settler population of Minnesota. By doing so, it’s my hope that readers will come to empathize with the Native peoples and take a new, more compassionate view on our shared past. However, because the list of wrongs is so egregious and long, it was difficult to fit it all into one story. In one chapter that was eventually cut from the manuscript, I placed Thomas, a white settler-colonialist, in the place of the Dakota combatants who sat before the U.S. military commission. Because my novel is an alternate history, we see Thomas held as a prisoner. We see Thomas seated before a commission of Dakota judges all ready and eager to send him to the gallows. We see Thomas face the confusion and grief of a short, unfair trial that quickly determines the fate of his life.

Today, I’d like to share that chapter with you. It was cut from the manuscript because it simply could not fit within the narrative. But, like the novel itself, it shares a valuable perspective on history that I think needs to be heard. For those who have not read the novel, but still intend to, this chapter does contain spoilers.

Download the Chapter Excerpt

Thomas

Fort Snelling

November 1862

Water trickled down the ridged wall of the stone barracks. The slow moving beads of water dripped onto the floor forming a growing mound of ice. Thomas admired the smooth shine and perfect symmetry of the ice mound, watching it grow bigger from one day to the next. A shiver passed through his seated body. Thomas pulled his knees in tight and tried to wrap his thin cotton blanket tighter, but he struggled to reach the edge of the blanket because of the metal shackles that held his wrists together. An older man—not more than forty-five or fifty—pacing back and forth and sipping a tin of water noticed Thomas’ struggle. He set down his tin, grabbed the blanket with his shackled hands, and pulled it over Thomas’ knees. Thomas and the older man, both now prisoners of war, regarded each with a nod. Then both returned to their previous occupations; Thomas watching the water drip onto a mound of ice and the older man pacing back and forth.

Hundreds of men, former defenders of Fort Snelling, wallowed in the barracks living in a passive state of uncertainty. They knew nothing of their families; nothing of their futures. They lived in monotony. That monotony was broken when a key entered the prison door, and the doorknob turned. Each of the prisoners craned their necks to watch. As had become routine, three Indian guards entered. Wearing forage caps and Union coats over their leggings and moccasins, the guards appeared quite humorous. Looking at them, Thomas sneered knowing that the Indians had taken army uniforms from the commissary, or worse, from a dead soldier.

With rifles in their hands and knives on their belts, the guards scanned the room. The prisoners standing near the door stepped back, slinking away like young children afraid of their parents’ discipline. Recognizing the fear in the faces of the prisoners, the guards turned to each other and laughed. As their laughter died down, one of the guards stepped toward the center of the room. His satisfied grin quickly changed to an unpleasant glare. He searched the room leaning forward at the neck and turning his head from left to right like a vulture looking for rotting flesh. “Niye,” he said in a demanding tone while gesturing toward a group of prisoners, his hand still gripping his rifle. “Niye!” he said again. “Niye!”

A stocky man with a thick graying beard put his shackled hands to his chest, acknowledging the Indian’s command. Thomas looked at the stocky man with curiosity, unsure if he knew him before the fort had been overrun. All the men looked the same now, tired, dirty, covered in frayed, torn blankets.

“Niye!” the guard said again using the same demanding tone, this time waving his arm forward as if to say come. “Yakuwa, yakuwa,” the guard added.

The stocky prisoner looked to his left and right in search of sympathy but found only darting eyes and lowered heads.

“Niye! Yakuwa!”

The prisoner walked forward slowly, hesitantly, with the chain between his ankles clanking and rattling as it dragged over the wooden floor of the former barracks.

With narrowed eyes the guard watched as the prisoner edged past him and was ushered out the door by the other two guards. He remained there in the center of the floor searching the room, eyes moving from one prisoner to the next. Thomas looked up and caught the attention of the guard who looked back at him with a subtle, satisfied grin. Then he strode quickly to the door smirking as he walked out, pulling the door shut behind him. With a turn of the key the room returned to a state of dismal silence.

The men continued their aimless milling about while Thomas lowered his head between his knees and took a long, slow breath. He felt the cool, dry air enter through his nostrils. He held it in his chest as he closed his eyes and listened to the dripping of the water like the ticking of a clock. His stomach churned, and his feet stung like they’d been soaked in ice-cold water. He released his breath, but kept his eyes shut tight.

How could I have been so naive, he thought? How could I have been so dumb? My father is dead. My friends scalped by…by…by Savages! And what was Samuel to do about it, that prissy, over-achieving louse! He never loved our father, not like I did. He couldn’t. And what was he to do! To take revenge? He couldn’t even scold a cat if it bit him on the cheek. Huh! He was there when father died and he did nothing. He turned and ran away like the fleeing, pea-brained oxen while father stood bravely to protect our cranberries—to protect the only thing that would provide for our family. Samuel is to blame for bringing us to this place; for planting the seed in our heads. He is to blame for father’s death. He’s to blame for me being here, now. I was forced to seek my own revenge by joining the army in the midst of a war. Was I to know there would be an outbreak on the frontier? Was I to know these Indian beggars, the ones I once thought of as friendly, would band together with enough numbers to overtake the United States Army. Look at us. We have become the beggars, imprisoned in our own fort. God, I had done so well, too. I had done so well once I joined the army to learn discipline and order; to take commands and complete chores—all the things Samuel was harping on me about. I would have returned to the farm and shown Samuel what I could do; shown him that I had grown into a man; shown what I could be if he had only cared less for himself and more for our family.

The clunky scratching of the key entering the door startled Thomas from his thoughts. His eyes burst open, and his head shot up as he looked to see who entered, though he knew exactly who it would be.

The three Indian guards emerged from the door frame, still wearing Union blue over their deer skin and fur. Once again the prisoners slinked away, not wanting to discover what awaited them outside of their uncomfortable but safe jail cell. Wasting no time, the Indian guard who eyed Thomas earlier took a direct path to where Thomas was seated.

Standing just inches away, he leaned over Thomas and said in English, “Get up.”

Keeping his head level, Thomas turned his eyes upward to see a determined glare and a face filled with hate staring back at him.

“Get up!” he said again, his frozen breath lingering in the air.

When Thomas didn’t move, the guard pounded the butt of his rifle against the wooden floorboards, making a cracking sound so loud it hurt Thomas’ ears.

With all of the prisoners watching, Thomas raised his shackled hands up toward the Indian guard indicating that he needed help getting up. The guard stepped back and furled his brow as if offended by the gesture.

Quickly, the older man who had been pacing nearby, stepped beside Thomas, grabbed his arms by the wrists, and hoisted him to his feet.

“Thank you,” Thomas said in a hushed tone as the blanket slid from his back.

The guard narrowed his eyes and pointed toward the door where two other guards stood waiting. “Go now!” he said. “Go!”

Thomas stepped forward, minding the chain between his ankles so he wouldn’t trip. As he did, the prisoner who had helped him said, “Admit to nothing.”

Thomas lowered an eyebrow, uncertain of the meaning of the statement. But as he turned to ask him, the man was struck forcefully in the jaw by the butt of the guard’s rifle, and he fell to the floor. Thomas winced at the sight of it.

Thomas continued his slow walk toward the open door of the prison. Thin and hunched, only the wisps of long blond hair on Thomas’s chin hinted at his true age as a boy of merely sixteen years.

Stepping outside Thomas immediately brought his hands to his face to shield himself from the blinding sunlight glinting off the pure white snow that covered the parade ground. One of the Indian guards grabbed Thomas by the arm and gently steered him to the right. The two trailing guards said something in their native language and then peeled away to the snowy parade ground where there were numerous tepees and wigwams. Thomas and the lone remaining guard moved along the porch corridor of the barracks toward the iconic round tower in the western corner of the fort. It was partially toppled by cannon fire and looked more like a pile of stone than a tower, but Thomas didn’t care now. Shuffling along he breathed deeply the cool, crisp air feeling grateful to be alive.

“Where are we going?” Thomas said.

The Indian guard looked at him curiously. Thomas noticed the age in his face shown by his sunken cheeks and wrinkled upper lip. He appeared old enough to remember a time before Thomas and others like him had moved onto his homeland.

“Where are we going?” Thomas said again.

The guard smiled, revealing several cracked and broken teeth and then said, “To-ked eniciyapi he?”

“I don’t speak Indian.”

“To-ked eniciyapi he?” the guard repeated. When Thomas didn’t answer the guard held his hand to his chest and said, “ Hepaŋ. Hepaŋ.”

“Oh . . .” Thomas said. “Your name is Hepaŋ.”

“Hepaŋ,” he said again, with his smile widening enough to hide his sunken cheeks.

Thomas brought his shackled hands to his chest. “I am Thomas. Thomas.”

Hepaŋ nodded, sounding out the name, “T–omm–iss.”

Thomas couldn’t hold back his smile, and then they both laughed.

Hepaŋ held out his hand is if to say ‘wait’ and then reached into the pocket of his Union jacket. He pulled out a piece of dried meat and offered it to Thomas. “Woyute,” he said. “Woyute.”

Hesitant at first, Thomas grabbed the meat and brought it to his mouth. Ripping it between his teeth, he savored its toughness. He put the rest in his mouth and chewed greedily, noticing how pleasurable it was to feel real food on his tongue rather than just the hot broth he had grown accustom to.

Thomas savored the meat as long as he could, swallowed, and then nodded in gratitude to his captor. Hepaŋ’s bright face suddenly dimmed. He ushered Thomas forward, and within a few feet they reached what used to be the schoolhouse and chapel. Hepaŋ briefly made eye contact with Thomas, showing him a look of compassion, but then his face hardened as he pushed Thomas forward through the open door of the former schoolhouse.

Inside the one-room schoolhouse there were a dozen Indian men seated in a circle on the floor. In perfect unison each one turned their head to look at Thomas as he entered. Startled, Thomas stood, still unsure if he should proceed within the circle.

A young man with bone trinkets hanging from his long, dark hair stood and said, “Please, enter.” He gestured toward the center of the circle where a chair had been placed. It was the only piece of furniture in the entire room.

With the chain of his ankle cuffs scraping the floor, Thomas edged forward. The rich scent of tobacco filled the room, and a smoldering fire burned in the stove giving off enough heat to shield the space from the cold air outside. The seated Indian men parted as Thomas entered the circle and took his place on the lone chair. It creaked loudly as his thin figure landed gently on its rickety frame.

There was a moment of silence while the Indian men examined Thomas with their eyes. Their dark faces were lined with age marked by years of life experience. Their heads, hair, and necks were adorned with various jewelry, ornaments, and beads. Some wore eagle feathers atop their heads while some had muskrat tails hanging from their ears and hair. Others, had colorful glass beads ornamenting the hair that fell over their shoulders and chest. Some even had pieces of elk horn and bear claws hanging around their necks. They passes a pipe among them, inhaling deeply and exhaling slowly, as they looked at Thomas with their worn, expressionless faces.

They began to speak. Not toward Thomas, but toward each other. They spoke quickly, first from one side of the circle and then the other, back-and-forth, exchanging words in their own languages.

Thomas felt himself growing hot, uneasy, frustrated. He didn’t know if they were discussing his fate.

After a minute or two, the circle of Indians stopped speaking and looked at Thomas as if waiting for a response. The young Indian man with bone trinkets in his hair, who was apparently the interpreter, said to Thomas, “How many years do you have?”

Thomas looked around at their expectant gazes. “Sixteen.”

“Ake ŝakpe,” the translator said, then the men resumed their back-and-forth discussion, this time in a more urgent tone.

After another minute or so, the men grew silent once more. “Are you a soldier in the U.S. army?” the interpreter said.

Thomas hesitated. “Y-yes.”

“Did you fight in the white man’s army the day the fort was attacked? Did you fire your weapon at the attackers?”

Thomas recalled the words of the prisoner who told him not to admit to anything. But if he said no they would know he was lying. They would find out and then punish him for the lie. He could admit to firing his gun. What crime was it to fight as a soldier in a battle?

“Yes,” Thomas answered.

Recognizing the word ‘yes’ the circle of Indians continued their discussion without waiting for a translation. This time they spoke quicker than before. To Thomas, it was a blur of sounds. The tone was intense and urgent.

Was he being condemned? Would he be hanged or worse, scalped? Would he, like his father, be scalped by savage Indians simply for coming to a place where the land was open and free, where the trees and rivers were untamed by settlers?

The Indian men became silent once more, their faces now hard and menacing. “Were you with the Long Trader, the one you call Sibley?”

Thomas could feel his heartbeat pulsing in his temples, hard and quick. Sweat gathered on his forehead. He felt nauseous. Sick. Scared.

“I didn’t do anything wrong. I–I came to Minnesota with my family. We were encouraged to come by the government. They said it was all right. They said the Indians had been given new lands. Reservations. But then . . . then they killed my father. You killed my father. And a war started. So I joined. I didn’t know we would be fighting Indians. I just wanted to prove my brother wrong. I wanted . . . I wanted . . . I wanted to show him that I was grown up and that I didn’t need him anymore. That I was my own man.”

“Enough!” one of the Indian judges said, surprising Thomas with sudden and strong tone. The man, who wore an eagle feathered headdress and flaxen colored trousers, turned his head to the interpreter.

The interpreter then turned to Thomas and said, “Answer yes or no. Were you with the Long Trader Sibley?”

Thomas paused, looking about the room while he tried to settle his pattering heart. For a moment he admired the wooden planks of the walls, wondering if a sawyer like his father—a sawyer like his brother—had cut them. Where was Samuel? Where was his family? Were they alive?

Thomas opened his mouth, held his breath, and finally said, “Yes. Yes, I was, but he was our commanding . . .”

The council did not wait to hear more. They spoke over him, showing no interest in his explanations. When they finished, the Indian wearing the eagle feathered headdress spoke clearly and directly to the interpreter. Thomas watched as the interpreter nodded. He knew his fate had been sealed.

“Thomas Copeland,” the interpreter said. “The intertribal council of elders have determined that you—first as an intruder settling on foreign land, second as a part of an armed resistance—have been a part of a rebellion against the tribes and people of Mni Sota Makoce and their ancestors. Your punishment, as is customary in your country, is that you are to be hanged by the neck until you are dead.”

Thomas was breathless. Numb. He felt nothing. He heard nothing, as if he were floating in an empty void. Who could deserve this? Who could have everything taken from him so quickly? So completely. Merely for existing.

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

September 4, 2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Donation Update (August)

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction, are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

August 2023

Pre-Orders of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 11 = $11

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $16.80

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – $100

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $127.80

Thank you for your continued support!

Learn MoreDonate NowApply NowWhile we’re still a long way from our goal, there are numerous efforts underway that will help spread the word and gain support for this important grant. First, author Colin Mustful has scheduled numerous speaking engagements and those speaking fees will be donated to the grant. There will be many additional sales to report once the novel comes out and those sales reports become available to me. On September 8 and 9, Mustful will be attending the Indigenous Writers Gathering at Fond du Lac Tribal & Community College which will help notify tribal communities about this grant opportunity. And finally, Mustful is currently putting together a silent auction and live fundraiser for the months of October and November. Final details for the event will be available soon.

Current Fundraising Total = $491

No Donation is too small!

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

August 18, 2023

The first white victims of the U.S. – Dakota War

Gary Clayton Anderson’s 2019 book, Massacre in Minnesota, provides specific details on the outbreak of war on August 18, 1862.

Gary Clayton Anderson’s 2019 book, Massacre in Minnesota, provides specific details on the outbreak of war on August 18, 1862. On August 18, 1862, war erupted in southern Minnesota when the Dakota Soldier’s Lodge attacked and killed the white traders, clerks, and government employees at the Lower Agency. The Soldier’s Lodge then spread throughout the white settlements of south and southwestern Minnesota killing and taking captive hundreds of white and mixed-race people. The attack was precipitated by decades of poor treatment toward the Dakota people—loss of land, culture, and the resources necessary to survive. Nevertheless, by the time the attacks were subdued, an estimated 400 to 800 Minnesotans had been killed while another 250 were taken captive.

Using the scholarship of Gary Clayton Anderson in his book Massacre in Minnesota, this blog post will attempt to clarify the first few hours of the attack which began early on the morning of Monday, August 18, 1862. A day earlier, a small hunting party of Dakota murdered Robinson Jones and four other settlers near the white settlement of Acton. When the hunting party returned to their village and told the Dakota leaders what they had done, a serious debate broke out among the leaders and the Soldier’s Lodge. Fearing retribution, angered by being denied credit by the traders, and with the knowledge that the Union was embroiled in a civil war, the Dakota decided it was time to go on the offensive.

According to accounts, James William Lynd was the first victim of the U.S. – Dakota War.

According to accounts, James William Lynd was the first victim of the U.S. – Dakota War. As the sun rose the next day, a group of armed Dakota, ready and painted for war, arrived at the Lower Sioux Agency—an area of stores and housing established by the government to manage relations with the Dakota people. The Dakota arrived with a plan. According to historian Gary Clayton Anderson, the akicitas, leaders of the Soldier’s Lodge, assigned certain men to open the assault by attacking the trade houses of those trader’s who they believed had wronged them. When the Dakota opened fire, the first to be shot was James Lynd who stood in the doorway of Andrew Myrick’s trade house. The next two to be gunned down were George W. Divoll and the cook “old Fritz” who were at Myrick’s counter. Andrew Myrick himself—well-known as the trader who allegedly told the Dakota, “So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung”—was hit with two gunshots but managed to flee upstairs. However, once he heard of plans to burn him out, he fled through an upstairs window but was soon shot down as he ran away. The soldiers severed his head and stuffed his mouth with grass.

A trader with Dakota heritage, Francois LaBathe, was gunned down at his store. Three clerks working at Louis Roberts’ store—Patrick McClellan, Joseph Belland, and Antoine Young—were also quickly killed. At the stables, three government workers—A.H. Wagner, John Lamb, and Lathrop Dickinson—were killed while trying to prevent the theft of horses. Philander Prescott, a government worker who lived among the Dakota for forty years and had a Dakota family, was shot and killed while running for his house.

After a face-to-face encounter with Little Crow, Revenerend Samuel Dutton Hinman survived the first day of the attack by fleeing to Fort Ridgely.

After a face-to-face encounter with Little Crow, Revenerend Samuel Dutton Hinman survived the first day of the attack by fleeing to Fort Ridgely. But there were also those that the Dakota protected or allowed to flee. Amidst the chaos the Reverend Samuel Hinman had a direct encounter with the Dakota leader Little Crow. Hinman asked the leader, “Crow, what does this mean?” Little Crow did not answer, leaving the Reverend to flee to the ferry crossing like so many others were doing. At William Forbe’s store, the soldiers had wounded George W. Spencer and allowed William Bouratt to escape. While planning an assault on the attic where Spencer held up, a veteran soldier, Wakinyantawa, who was friends with Spencer, publicly declared that if anyone hurt Spencer they would have to answer to him. Spencer survived.

By the end of the assault on the Lower Agency, twenty government employees and nine traders and clerks were killed while forty-six escaped. But this was just the first hour of the attack. Most people in the surrounding settlements knew nothing of the outbreak and the imminent danger they faced. It would take a day for news of the attacks to arrive in St. Paul and it would take more than a week to mount any real defensive force. In the meantime, the struggle to survive which plagued the Dakota throughout the preceding years, would plague the settler-colonialists of south and southwestern Minnesota leaving them in a struggle to survive.

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an author, historian, and publisher. He is the author of Reclaiming Mni Sota, an alternate history that reimagines the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes engaging, well-researched historical novels. When not writing, Mustful enjoys hiking, running, and playing soccer. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

August 3, 2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Donation Update (July)

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction, are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

July 2023

Pre-Orders of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 2 = $2

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $29.40

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – $0

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $31.40

Thank you to our July donors!

Praveen Kandi

Learn MoreDonate NowApply NowWhile fundraising is off to a slow start, there are numerous efforts underway that will help spread the word and gain support for this important grant. First, I am in the process of scheduling numerous speaking engagements and those speaking fees will be donated to the grant. There will be many additional sales to report once the novel comes out and those sales reports become available to me. In September, I’ll be attending the Indigenous Writers Gathering at Fond du Lac Tribal & Community College which will help me get the word out to tribal communities. And finally, I’m currently putting together a silent auction and live fundraiser for the months of October and November.

Current Fundraising Total = $273

No Donation is too small!

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

July 19, 2023

It’s Time to Broaden Our Views on History: A Dakota War Historiography

This blog post relies heavily on the scholarship of William E. Lass in his article titled Histories of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 published by Minnesota History Magazine in 2012. To learn more about the historiography of the U.S. – Dakota War, I highly recommend reading the article.

“Anyone who writes history engages in a selective process.” – William E. Lass

Historiography is the study of the body of historical work about any given topic. As a historian, it’s important to study the historiography of a topic before delving deep into the research and formulating an argument. For example, before researching and writing my master’s thesis about the Pampas Indians of Argentina, I was required to read thirteen books about the history of Argentina during the 19th century. This helped me understand the historical context of the people and places I would be researching.

But while historiography has become essential to studying history, it also raises significant questions—questions about who is writing history and how and why they came to their conclusions. A very brief historiography of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 demonstrates how problematic our views of the past can become. By relying a single viewpoint, that of the white, Western world, we are limiting our views of the past to a single set of cultural influences and backgrounds. For better or worse, history is an unbroken line of narratives that build off of one another and are influenced by each preceding narrative. Our stories are shaped by what we’ve been told and what we’ve been taught. Our stories are a reflection of who we were and who we are. We get to decide where the narrative goes next.

1864

History of the Sioux War and Massacres of 1862 and 1863 by Isaac V.D. Heard

Isaac V.D. Heard was born in Goshen, Orange County, New York. He moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota and studied law. Heard was admitted to the Minnesota bar and served as the Ramsey County Attorney and as the Saint Paul City Attorney. Heard was involved in the Dakota War of 1862 and served with United States General Henry Hastings Sibley. He served as acting judge advocate involving the Sioux Indians and the Dakota War of 1862. Heard served in the Minnesota Senate in 1872. He died at his home in Goshen, New York and was buried in Saint Paul, Minnesota. (Source:Wikipedia)

1864

Dakota War Whoop: Or Indian Massacres and War in Minnesota of 1862-‘3 by Harriet E. Bishop McConkey

Harriet E. Bishop (January 1, 1817 – August 8, 1883) was an American educator, writer, suffragist, and temperance activist. Born in Panton, Vermont, she moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota in 1847. There, she started the first public school as well as the first Sunday school in Minnesota Territory. She was a founding member of temperance, suffrage and civic organizations, and played a central role in establishing the First Baptist Church of Saint Paul. An active promoter of her adopted state, she was the author of books such as Floral Home, or First Years of Minnesota (1857) and Dakota War Whoop, or Indian Massacres and War in Minnesota of 1862–63 (1863). (Source: Wikipedia)

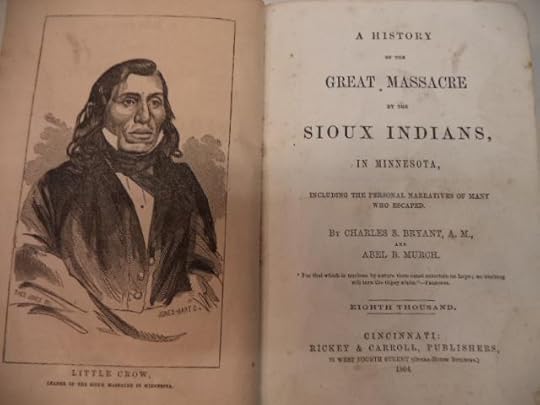

1864

A History of the Great Massacre by the Sioux Indians by Charles S. Bryant and Abel B. Murch

Charles S. Bryant was a lawyer who moved from Ohio to Minnesota in 1859. In 1863, while practicing in St. Peter, he presented more than 100 damage claims to the Sioux Claims Commission, the body established by Congress to be the federal government’s arbiter in determining compensation for war-incurred losses. (Source: William E. Lass)

Abel B. Murch was born in New York, March 4, 1824. He lived at the Upper Sioux Agency before the war and had joined the Renville Rangers only days before the opening of hostilities. As a member of the Renville Rangers, Murch helped defend Fort Ridgely from the attacks of the Dakota. (Source: William E. Lass)

1891

The Indian’s Revenge: Or, Days of Horror. Some Appalling Events in the History of the Sioux by Alexander Berghold

Alexander Berghold was born in Dirnrieth, parish of St. Margarethen, in the state of Steiermark, Austria on October 14, 1838. His father, Philip and mother, Josepha Kloescher, moved with the family in 1844 to Petersdorf, parish of St. Marien on the Pickelbach River where they operated a large estate and from where Alexander attended the school of St. Marien. In the fall of 1851 Alexander left home to attend the normal school at Graz. After passing his final examinations at the latter institution, he entered the theological department of the Royal Franzend University in 1862. Two years later in 1864 Alexander Berghold was recruited by the most famous Minnesota missionary of all, Father Francis Pierz, to come to Minnesota and work in the German immigrant missionary field. (Source: La Vern J. Ripley)

1904

Indian Outbreaks by Daniel Buck

Daniel Buck moved to Minnesota Territory in 1857 and eventually settled in the area that became Mankato, Minnesota. He was on hand to witness the aftermath of the final climatic battle between the Dakota and Ojibwe tribes at the Battle of Shakopee in 1858. Buck was a central figure in the founding of the Village of Mankato, the Mankato Normal School, and the Mankato Area Chamber of Commerce. In 1866, Buck served in the Minnesota House of Representatives as a Democrat and then served in the Minnesota Senate from 1879 to 1883. Buck also served on the Minnesota State Normal School Board and Mankato School Board. Buck was an associate justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court from 1894 until 1899 when he resigned due to his wife’s ill health. In 1904, Buck published his book on the Indian troubles in Minnesota, especially for the Spirit Lake actions. He intended his book Indian Outbreaks to be a judicially impartial account. (Source: Wikipedia)

1908

Great Sioux Outbreak of 1862 in Minnesota in Three Centuries, Volume 3, by Return I. Holcombe

Born Robert Ira Holcombe in Huntington Township, Gallia County, Ohio, February 24, 1845, he changed his name to Return after his grandfather’s grandfather, a soldier of Connecticut in the army of the American Revolution. His parents and family moved to Missouri when he was six years old, and there he received a serviceable education. During the Civil War, Holcombe served on the Union side in the Tenth Missouri Regiment. In Missouri and Kansas, Holcombe became a proficient writer on the staff of various publishers of county and city histories. In the summer of 1888 he helped prepare several long chapters of a history of St. Paul. From that date his home was in St. Paul where he did much work as a newspaper writer, especially for the Pioneer Press and Dispatch. (Source: Minnesota History, Vol. 2, No. 1, March 1917)

1924

A History of Minnesota, Volume 2, by William Watts Folwell

William Watts Folwell (1833-1929) was an American academic and advocate for parks. He attended Hobart College and later became an adjunct professor of mathematics there. In the years leading up to the American Civil War, he studied philology in Berlin and served in the 50th New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment. After the war, he briefly pursued business ventures in Ohio and then served as the chair of mathematics at Kenyon College. In 1869, Folwell became the first president of the University of Minnesota, where he implemented an ambitious plan for expansion. He also played a significant role in promoting parks in Minneapolis, serving on the city’s park board and supporting the creation of a park network. Folwell’s contributions were recognized with the naming of buildings, neighborhoods, and schools in his honor. He passed away in 1929 and was buried in Lakewood Cemetery. (Source: Wikipedia)

1956

The Indian Wars of Minnesota by Louis Harry Roddis

Louis H. Roddis (1918-1991) was the 15th President of the American Nuclear Society (ANS) and a notable figure in the field of nuclear energy. After graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy, Roddis served in the Navy during World War II and participated in the atomic weapons tests in the Bikini Atoll. He played a significant role in the development of nuclear submarines and the first major nuclear power plant in the U.S. at Shippingport, Pennsylvania. Roddis later became the president of Pennsylvania Electric Company, where he oversaw the construction of innovative transmission lines. He held leadership positions in various organizations and received several awards for his contributions to the field. Roddis passed away in 1991, leaving behind a legacy of advancements in nuclear energy. (Source: American Nuclear Society)

1959

The Great Sioux Uprising by Chester M. Oehler

Chester M. Oehler worked as a camp clerk for the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company in 1928. He graduated from the University of Minnesota, where he majored in journalism, in 1932. Later, Oehler worked as the director of research for the western offices of Batten, Barton, Durstine, & Osborn. (Source: William E. Lass)

1961

The Sioux Uprising of 1862 by Kenneth Carley

Kenneth Carley was a journalist who wrote for the Ortonville Independent, the Minneapolis Star, and the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune’s Picture magazine. He was also the founder and past president of the Twin Cities Civil War Round Table and was named to the citizens’ advisory committee of the Minnesota Civil War and Sioux Uprising Centennial commission. He graduated from the University of Minnesota. (Source: Goodreads)

1992

Over the Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862 by Duane Schultz

Duane Schultz is an accomplished author known for his expertise in psychology and historical fiction. He earned degrees from Johns Hopkins University, Syracuse University, and American University, specializing in social psychology. Schultz has written college-level textbooks, including internationally translated editions, as well as books on psychology and a comparative study of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. After a successful teaching career, he transitioned to full-time writing and currently resides in Clearwater, Florida. Schultz has authored novels on World War II and the Civil War, drawing from extensive research and interviews with former prisoners of war. His books have been adapted into television documentaries, received critical acclaim, and have been published in various formats and languages. (Source: DuaneSchultz.com)

2006

Let Them Eat Grass by John J. Koblas

John J. Koblas (d. March 8, 2019) was a celebrated author, musician, and meticulous researcher from Minnesota. With over 70 books to his name, he focused on outlaws like Ma Barker, John Dillinger, and the James-Younger Gang, earning him three Perry awards. Koblas explored the lives of Minnesotan authors F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sinclair Lewis, notably with his book “F. Scott Fitzgerald’s St. Paul: A Traveler’s Companion to His Homes & Haunts.” Additionally, he delved into historical mysteries for young adults and wrote about figures such as J.J. Dickison and the Minnesota Sioux Uprising. As a trained concert pianist and a member of the rock band the Magpies, Koblas’s musical talents were well-known. Through lectures, appearances, and television contributions, he made a lasting impact on literature, music, and historical research. (Source: St. Paul Pioneer Press)

2009

The Dakota Uprising: A Pictorial History by Curtis A. Dahlin

Curtis Dahlin, an independent historian specializing in the Dakota Uprising of 1862 in Minnesota, has spent thousands of hours and driven many thousands of miles researching and writing about the subject. In 2007, he published Dakota Uprising Victims: Gravestones & Stories. Previously, in 2001, he participated in compiling and writing Joel E. Whitney: Minnesota’s Leading Pioneer Photographer, and in 2008, he wrote an essay for Trails of Tears: Minnesota’s Dakota Indian Exile Begins. He and his wife, Gay, live in Roseville, Minnesota. (Source: USDakotaWar.org)

2019

Massacre in Minnesota: The Dakota War of 1862, the Most Violent Ethnic Conflict in American History by Gary Clayton Anderson

Gary Clayton Anderson is an historian of the American Indian and the American West. His most recent book is Massacre in Minnesota: The Dakota War of 1862, the Most Violent Ethnic Conflict in American History (2019). His other publications include Kinsman of Another Kind: Indian-White Relations on the Upper Mississippi River (1984), a nominated finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Little Crow, Spokesman for the Sioux (1986), Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862 (ed., 1988), Sitting Bull and the Paradox of Lakota Nationhood (1996), The Indian Southwest: Ethnogenesis and Cultural Reinvention (1999), winner of the Angie Debo Prize, The Conquest of Texas: Ethnic Cleansing in the Promised Land (2005), a nominated finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Will Rogers and “His” America (2010), Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America, (2014), The Army Surveys of Gold Rush California: Reports of the Topographical Engineers, 1849-1851, (ed., 2015), and Gabriel Renville and the Creation of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Indian Reservation (2018). He has also co-authored with Kathleen P. Chamberlain, Power and Promise: The Changing American West (2007). (Source: The University of Oklahoma Department of History)

2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 by Colin Mustful

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

History is both a product of our time and a product of the compiled times that have come before us. Even in my own writing, which began in 2007, I can see a significant change in how I convey historical topics related to the U.S. – Dakota War. The history hasn’t changed, I’ve changed. Looking back through these sources, each one is a clear reflection of the time and place in which it was written. Moreover, there is a clear pattern regarding the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of the people who share and proliferate this history. On its own, that’s not a problem. Everyone has a right to take an interest in and share history—to share their views on history. But when you review these and thousands of other sources on the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, it’s obvious that certain voices are missing. That is a problem.

Today, there is a lot of excellent scholarship being done by Indigenous scholars in Minnesota such as Brenda Child, Anton Treuer, and Waziyatawin. But when you look at the thousands of sources on the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 that have been written over the past 160 years and how the perspectives and messages of those sources have influenced present views on this history, it becomes apparent that it will take a lot more than a few Indigenous scholars to reframe the entire conversation. What’s more significant, is the structural framework of our society that has enmeshed itself so deeply in who we are, that the opportunities to learn, understand, and convey such historical messages is and will continue to be dominated by an all too narrow cultural viewpoint.

As a historian, a writer, a human being, I am a part of all of it. I cannot offer any immediate solutions, I merely wish to contribute to a more even-handed, level playing field where historical narratives, discussion, conversations, and scholarship are shared through any and all viewpoints—whether they be Western, white, and educated, or Native and traditional. This, and other factors, contributed to my decision to create the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. While I continue to try to understand our history and its legacy for us today, I want to facilitate and support those viewpoints outside of my cultural, ethnic, and religious background while also helping others make their own contributions to the historiography of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. I want to view history objectively—fully—and I cannot do that until all voices have been heard. I want to see the conflict—I want to see ourselves—from all sides and all perspectives so that I can truly understand what happened here and how it led to who we are today.

July 5, 2023

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant – Monthly Donation Update

From June 15 – December 31, 2023, author Colin Mustful and publisher History Through Fiction, are accepting donations for the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant, a literary diversity initiative to raise $10,000 for one Indigenous writer from Minnesota. As a part of their effort, from now until the end of the year, or until the goal is met, Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction will contribute to the grant in three ways:

$1 from the sale and pre-sale of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota will be donated to the grant.All membership fees for History Through Fiction’s member area will be donated to the grant.All speaking fees/donations for author programs presented by Colin Mustful will be donated to the grant.This monthly update will help supporters of this initiative follow along as we get closer and closer to our goal of empowering Indigenous storytellers.

June 2023

Pre-Orders of the novel Reclaiming Mni Sota – 3 = $3

Member Area Payments less transaction Fees – $20.72

Speaking Fees/Direct Donations for Speaking – $0

Total Contribution from Colin Mustful and History Through Fiction – $23.72

Thank you to our June donors!

Addison Armstrong

Eileen Sanchez

Eric Weintraub

Lindsey Fera

Robin Henry

Hannah Karau

Brandon Mustful

No Donation is too small!

Thank you to all of our donors, advocates, and volunteer judges!

Fundraising Total as of July 3, 2023 – $227

June 21, 2023

Book Review: The Seed Keeper by Diane Wilson

“People don’t understand how hard it is to be Indian,” Carlos said. “I’m not talking about all the sad history. I’m talking about a way of life that demands your best every single day. Being Dakhóta means every step you take is a prayer.”

The Seed Keeper by Diane Wilson follows the life of Rosalie Iron Wing, a Dakhóta woman from the Minnesota River Valley in Southern Minnesota, as she re-discovers her family, her history, and her sacred tradition. We meet Rosalie in 2002 when she takes a desperate journey through harsh winter conditions to find her family’s abandoned rural cabin. Nearly hopeless, Rosalie chooses to survive and bring life back to the cabin. From there the story takes us back to 1979 when Rosalie is a teenager just trying to figure out what she wants to do with her life. Though unfamiliar with farm work, she takes a job as a corn detasseler stating, “I was willing to do most anything to earn some money right then.”

As Rosalie spends her summer corn detasseling, she develops a relationship with the farmer, John. Before long, the two are married and though Rosalie always intends on running away, she finds that life with John on the farm is harmless, despite being a Native woman in a white community that was at the center of the U.S. – Dakhóta War. That’s when Rosalie discovered the seeds. On a dusty, cobwebbed shelf, she finds a shoebox labeled “Edna’s Seeds.” After opening the jars that held the seeds, Rosalie “admired how unique they were. The smooth white teardrop of the squash, the dark oval of the bean. We spent the morning together, the seeds and me, and by noon I felt we were well on our way to becoming acquainted.” Rosalie decides to plant a garden.

As the story progresses, it goes back and forth through time, mostly forward, following the life of Rosalie as she and John encounter the hazards of small, generational farming in an era of corporate farming—a way of life that forces farmers to use dangerous chemicals, genetically engineered seeds, and big machinery. Rosalie witnesses these hazards first-hand as she sees what corporations like Mangenta—a fictional seed company named in the novel—do to her community, her neighbors, and her husband. She sees the irreconcilable dichotomy between the land and profit and she’s made all that much more aware of it by her friend, Gaby Makespeace, who grows up to become a lawyer and environmental activist. Eventually, life unravels and we follow Rosalie back to her family’s cabin in 2002 when Rosalie must confront who she is, where she’s from, and how she can move forward.

There is a lot worth praising in Diane Wilson’s The Seed Keeper. The most valuable aspect of the novel is probably the message itself, something along the lines of: we’ve lost our connection to the land, we’re devastating the earth’s plant and animal diversity, and if we don’t do something to protect what’s left, we’re in for a dark and challenging future. You could argue that the novel is a criticism, but it doesn’t feel like one. It’s written with a certain empathy for our own ignorance—for our own situation. Whether it’s Rosalie who doesn’t quite know her place in the world, or the residents of New Ulm who are understandably bitter for what happened to their town so many years ago, there are no villains in this story, only victims. We are victims of a system that disconnects us from our past and from the truth.

But where this novel falls short, I believe, are in its ambitions. Though the novel follows the life of Rosalie Iron Wing, it detours a bit with chapters written from the perspective of Gaby Makespeace and Marie Blackbird, a young Dakhóta woman exiled from her home in the aftermath of the U.S. – Dakhóta War of 1862. And though there’s a clear connection and relevance between Rosalie’s story and the other POVs, the author brings in so much to the story that there’s not enough space to fully develop Rosalie’s experience. The quote “Being Dakhóta means every step you take is a prayer,” is a valuable one and it’s impossible to fully comprehend for those who are not indigenous to this land. In telling this story, the author tries to help us understand that experience by bringing us back to 1862, then forward to 1889, then forward again to 1920. The author shows us the exile of the Dakhóta, the imprisonment at Davenport, the harsh life at Crow Creek, the return to Minnesota, and the traumatic and devastating boarding school years. But it’s in this attempt to give readers the full picture, that I believe the novel loses its impact.

Rosalie Iron Wing has a meaningful experience from 1976 to 2002, but that experience fails to take hold deep inside the reader as the author takes us on a journey far too ambitious to keep up with. Ultimately, however, I recommend reading The Seed Keeper. The story shows us our history as seen, and discovered, through Dakóta eyes. But, more importantly, it provides a startling warning for the world we’ve created while, hopefully, instilling in our hearts the need for change—a revelation Rosalie and the reader will have in common.

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

June 15, 2023

Author Colin Mustful Announces New Initiative

For Immediate Press Release

Author and Historian, Colin Mustful

mnauthor@colinmustful.com

colinmustful.com

651.788.0055

Minneapolis, MN, June 15, 2023

Independent Author, Historian, and Publisher, Colin Mustful, announces a new literary diversity initiative, the Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant . The grant will support the writing of an enrolled member of a tribal community within Minnesota.

“I strongly believe actions like this grant help break down the legacy of historical and present wrongs perpetuated against Native peoples,” says Colin Mustful, who is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction. “At HTF, we believe that by giving financial support to Indigenous storytellers, we empower them to write their own stories, thereby reclaiming the narrative.”

The inaugural grant timeline coincides with the release of Mustful’s latest title, a work of alternate history that will be published by History Through Fiction. Reclaiming Mni Sota reimagines the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 and invites readers to question how things might have ended differently.

Applicants must be able to demonstrate a clear intention to share narratives, fiction or nonfiction, about the past through creative writing. The recipient will be selected by guest judges Erika T. Wurth, CMarie Fuhrman, and Linda Johnston. Once the successful applicant has been awarded, they may use the award toward the advancement of their creative writing projects, education, and career.

Mustful has pledged to contribute $1 from the pre-sale and sale of every copy of Reclaiming Mni Sota through 2023 to the grant. Additionally, Mustful will donate all speaking fees that are booked before the end of the year to the grant. To learn more about scheduling Mustful for an author visit, please see the author’s Pitch Deck.

Pitch DeckVisit the Grant’s GoFundMe PageAbout Colin Mustful

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

Reclaiming Mni Sota Indigenous Writers Grant

In conjunction with his forthcoming novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota, author Colin Mustful, and his press, History Through Fiction, will award one Indigenous writer a $10,000 grant to pursue the advancement of their creative writing projects, education, and career. To be considered for the grant, eligible applicants must submit proof of membership to federally-recognized Minnesota Indian community, a personal essay, and a writing sample.

Pre-Order the NovelContribute to the Grant

About the Novel

A creative re-imagining of the U.S. -Dakota War of 1862, Reclaiming Mni Sota is an eye-opening portrayal of one of America’s most tragic, regrettable events. Told through dual narratives from each side of the conflict, Reclaiming Mni Sota confronts America’s history of settler-colonialism while illuminating the personal stories and heartrending choices that men and women, white and Native, were forced to make. Based on real events told through descriptive detail and fully developed characters, Reclaiming Mni Sota reveals the truth of our history while connecting it to the present and asking readers to question how things could have been different.

Advance Praise“Reclaiming Mni Sota is a well-researched and impassioned tale of an unlikely friendship between two men: Waabi, an Ojibwe destined to reclaim his people’s land, and Samuel, a white farmer from the infant United States seeking a better life on the frontier. A painful, heart-wrenching, yet triumphant read, this is an alternate history in which Mustful paints the ending this country needed, and the Native population deserved.”

– Lindsey S. Fera, Historical Fiction Author

“With a historian’s eye for detail and a novelist’s empathy for individuals, this wonderful novel suggests an alternative ending to the 1862 war, one that inspires contemplation about what could have happened and what did.”

– Linda Ulleseit, author of The River Remembers

“What if the Ojibwa and Dakota conquered old rivalries to fight the U.S soldiers during the 1862 U.S-Dakota War? Many believe their combined forces would have pushed the whites out of Minnesota and changed history forever. Colin Mustful’s Reclaiming Mni Sota is an imaginative and intriguing story of what might have happened if this alliance had been made. Reclaiming Mni Sota may give an alternative account of this tragic episode of Minnesota history, but it also leaves the reader pondering race relationships today. It kept me reading to the very last page.”

– Candace Simar, Author of the Spur-Award winning Abercrombie Trail Series

“Mustful brings one of the most tragic events in Minnesota’s history to life in this carefully researched book.”

– Stephen E. Yoch, author of Becoming George Washington

“As an author and educator, one of my favorite things to do is pose the question “What if?” In Colin Mustful’s novel Reclaiming Mni Sota, he poses this question about the Dakota War of 1862. The answer? A compelling re-imagining of history that is accessible to the reader while also creating empathetic characters from both perspectives of the war.

Beginning with two young men who are learning from their elders how to exist in the world they were born into, Mustful’s deft hand at exposition brings us closer and closer to the penultimate moment with a growing sense of dread. When the historical events diverge into an alternate timeline, I found myself reflecting on the real timeline and questioning the “inevitability” of Manifest Destiny when the choices of two characters had the power to shape Minnesota into something much different.”

– Jason Lee Willis, Author and Educator

May 11, 2023

Feedback and Revisions – The Long, Challenging, and Rewarding Process of Writing a Novel

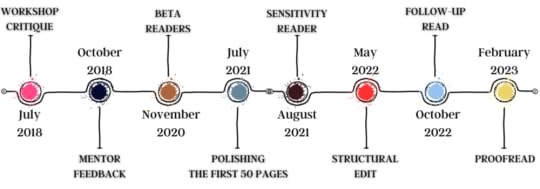

Reclaiming Mni Sota is ready. The cover has been designed. The interior, and all its words, has been laid out. The release date is set for October 10, 2023. But it took a long time to get here and there were a lot of ups and downs along the way. Today, I want to share some of that process with you. I want to share with you every time I reached out to someone for feedback in order to revise and improve the manuscript. This does not include my own self-editing, only those occurrences in which I received an outside view of my story. If you are one of those people, thank you very much. I sincerely appreciate all the feedback—critical and supportive—that helped make my idea into a novel.

In doing so, I’m also going to share two critical, challenging moments during the development of this story. These were difficult moments, but they weren’t bad moments. Each one helped push the story beyond its limits at the time. I am sharing them with you to give the full scope of what it means to create something of this nature—to create Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. What it becomes is yet to be determined.

July 2018 – Workshop Critique (Augsburg MFA Program)

The first time I received feedback on this story was during the second residency of my MFA program at Augsburg University. At the time it was only a story, about twenty pages long. Each member of the workshop—fellow students of mine—read the story and then discussed it amongst each other while I looked on. Then, they allowed me to ask them questions. This was very important and helpful feedback that provided me the direction I needed to expand the narrative from a short story to a novel.

October 2018 – Mentor Feedback (Augsburg MFA Program)

By this time I had started to expand the story by providing backgrounds for the two main characters. As a part of my MFA Program, I submitted the new, longer story to my MFA Mentor for feedback. My mentor was extremely critical of the story and my writing. Although the story I submitted was thirty pages long, he/she could not comment past page sixteen. By then end of the story, my Mentor left the following statement:

Your goal is to present Ojibwe/Dakota stories to general audiences in this region. That brings up real issues of cultural appropriation that your text fails to resolve. Sections of this text were offensive. You need to build your writing skills, but someone else’s culture is not the place to learn. My advice is to stop trying to tell stories you think you know, and start trying to write fiction – the story of things you don’t know, probably about yourself.

Finally, I cannot be your advisor if you decide to continue to write Ojibwe and Dakota stories from this perspective. Think about what you want and let me know.

That was tough to take. That was really tough to take. But it wasn’t a bad thing. It was, in fact, a great thing. This criticism—this ultimatum—pushed me and this story beyond anything it could be otherwise making it into the story that it is today. First, it created a sense of urgency that allowed me to become challenged in a way I hadn’t before. Second, it helped me better understand the intricacies of being a storyteller. It helped me critically examine my own viewpoint and how that viewpoint colors my manner of storytelling. It helped me ask questions that I otherwise may not have asked.

November 2020 – Beta Readers

When I graduated from my MFA Program in July 2019, I didn’t have a manuscript yet. I had a short story with a few long chapters of character background preceding it. I spent the next year moving beyond character background and creating a novel with a plot, conflict, and resolution. I called The Land of Sky-Tinted Waters. It was at this time, in November 2020, that I reached out to beta readers. Beta readers are the most wonderful people in the world. They are folks who agree, freely, to read and provide feedback on an unpublished manuscript. I was lucky enough to find about ten or twelve people gracious enough to do this. Each of them read the manuscript and, by February 2021, provided useful feedback about the story and characters. I put all that feedback together and used it to work on a full revision of the manuscript.

I’m going to share the feedback of one of the beta readers to give you an impression of how vulnerable writers are during this part of the writing process. Here’s what one beta reader returned to me:

Here are my comments for the text of your book until page 66. Unfortunately, I find myself unable to keep reading past that point because the character of Randolph got on my nerves and I developed an extremely strong dislike for him.

He/she went on, of course, describing just how unlikeable the character was. Like before, this criticism was hard to take. But looking back, it was necessary. It helped me reexamine Randolph’s character in a more full and complete way that I wouldn’t have otherwise. I was hurt when I read this, but it truly helped push the story forward.

July 2021 – Polishing the first 50 pages

In the summer of 2021, after thoroughly revising the manuscript based on the feedback of beta readers, I hired someone to help me with the query process. This is the process of writing a query letter (essentially a cover letter) and synopsis, while also identifying potential agents to represent me and my manuscript in the search for a publisher. This included providing critical feedback on the first fifty pages of the manuscript. That’s because, when submitting to agents and publishers, most of them require the submission of the first 5 – 50 pages…so, it must be clean and polished. The person I hired did a wonderful job of evaluating the first fifty pages and then helped me revise them until they were as strong and clear as they could be.

August 2021 – Sensitivity Reader

Because one of my main characters is Ojibwe, and because I included quite a lot of information in the novel about Ojibwe history, culture, and language, I was aware that it would have been wise to hire a sensitivity reader. To this point, I had avoided it because of the additional expense, however, it could no longer be avoided. A sensitivity reader is someone with intricate knowledge and experience regarding a specific culture or history. In this case, Ojibwe. The sensitivity reader carefully reviewed the manuscript looking for errors I made in respect to the Ojibwe language and traditions. He/she was especially helpful by pointing out discrepancies in various Ojibwe dialects. He/she was also able to point out certain cultural aspects that were so specific, no amount of reading would have allowed me to correct them myself. I am incredibly grateful to my sensitivity reader and I’m so proud of how he/she helped make this a better story that more fully and accurately represents the Ojibwe experience.

May 2022 – Structural Edit

I put my manuscript on submission for about six months but it did not find an agent or publisher. Because of that, I decided to hire a professional editor, something I was hoping to avoid because of the expense involved. When I did reach out to an editor, I hired them for what’s called a Structural Edit. This is a little bit cheaper than a developmental edit because it does not include any inline edits or comments. However, it did include a fifteen page report about the plot, setting, and characters of the manuscript. It also provided a chapter-by-chapter breakdown of everything that was working and everything that was not. The structural edit, though difficult to accept after already doing so much work on the manuscript, provided some very useful and specific feedback. I used that feedback to write yet another revision of the manuscript. I completed that revision in September 2022.

October 2022 – Follow-up Read

Although I was confident in my revision following the structural edit, I decided it was best to hire a professional to review and evaluate my new revised manuscript. I wasn’t thrilled about yet another expense, but there was simply no way, using my own biased judgment, I could be sure the story was ready for the world without an objective, professional viewpoint. And so, I rehired the person who helped me polish the first fifty pages. This person, like before, did a great job of reviewing the revision and provided me with the feedback I needed to put the final touches on the manuscript while also giving me confidence that it was ready for publication.

February 2023 – Proofreading

The final, final touches. Proofreading. In this case, I relied upon the generosity and intelligence of my sister Rachelle. Rachelle has helped me with each one of my novels and she did not disappoint here. She provided a full proofread of the manuscript, pointing out things such as missing words, timeline discrepancies, and grammatical errors. With her feedback, I was able to finalize the manuscript and move it on to the design stage. From this point on I will be receiving no more feedback on what the manuscript could be. I will only be receiving honest reviews and opinions about what the novel is.

Writing a novel is a challenging endeavor that cannot be done alone. It requires commitment, perseverance, an open mind, and the helpful guidance of many contributing partners. Thank you for going on this journey with me. I’ve done everything I can, and I sincerely hope you enjoy, and also learn from, Reclaiming Mni Sota.

What if Minnesota was Mni Sota Makoce, a Native held and governed land?

A creative re-imagining of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, Reclaiming Mni Sota is an eye-opening portrayal of one of America’s most tragic, regrettable events. Told through dual narratives from each side of the conflict, Reclaiming Mni Sota confronts America’s history of settler-colonialism while illuminating the personal stories and heartrending choices that men and women, white and Native, were forced to make. Based on real events told through descriptive detail and fully developed characters, Reclaiming Mni Sota reveals the truth of our history while connecting it to the present and asking readers to question how things could have been different.