Colin Mustful's Blog, page 6

April 25, 2023

The Beginnings of a Cultural Genocide – The Civilization Fund Act of 1819

Last summer, I wrote a blog about The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. The report revealed that “between 1819 and 1969, the United States operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states, including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii.” Sadly, these schools caused immense and irreparable damage to Native American peoples and cultures, something future investigation seeks to more fully illuminate. But what happened in 1819 that established Indian boarding schools, allowing for such harm?

On March 3, 1819, the United States Congress passed the An Act making provision for the civilization of the Indian tribes adjoining the frontier settlements, better known as the Civilization Fund Act of 1819. Its purpose was to provide against the further decline and final extinction of the Indian tribes by supporting religious mission schools in Native communities. It wasn’t until much later in the century that the U.S. used the wording of the Act to establish numerous Native American boarding schools.

A late 19th century Native American Boarding School where Native students are required to adopt white, euro-American styles of dress and speech. Image from the MNHS Collections.

A late 19th century Native American Boarding School where Native students are required to adopt white, euro-American styles of dress and speech. Image from the MNHS Collections. The Act gave the President “in every case where he shall judge improvement in the habits and condition of such Indians practicable” the authority to “employ capable persons of good moral character” to teach Native people the “arts of civilization.” The Act was championed by Thomas Lorraine McKenney, a Quaker who headed the Office of Indian Trade from 1816–1822. Then, when the Bureau of Indian Affairs was established in 1824, McKenney was appointed as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, a position he held until 1830. During his time as Superintendent, McKenney advocated the American Indian “civilization” program, and he was in favor of removing Native people to areas west of the Mississippi River.

From 1819 to 1830, fifty-two federally-funded Indian schools opened. These schools were primarily designed to promote religious conversion to Christianity but they also sought to remove the cultural ties of Native children and to assimilate them into white, Euro-American society. This form of cultural genocide continued for more than 150 years and was made all the more damning after the establishment of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879 whose motto was “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Today, Native people are still grappling with the suffering, trauma, and loss of cultural genocide, while the United States is confronting its legacy.

Sources:

Hope MacDonald LoneTree, “Healing from the Trauma of Federal Residential Indian Boarding Schools,” Administration for Children & Families, Accessed April 15, 2023, Published November 24, 2021, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/blog/2021/11/healing-trauma-federal-residential-indian-boarding-schools

“Civilization Fund Act,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Accessed April 15, 2023, Last Updated February 5, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilization_Fund_Act

“Thomas L. McKenney,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Accessed April 15, 2023, Last Updated March 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_L._McKenney

“Congress Creates Fund to “Civilize” Native American People,” EJI: A History of Racial Injustice, Accessed April 15, 2023, https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/mar/3

“Let All That Is Indian Within You Die!,” NARF Legal Review, 38, No. 2 (Spring/Fall 2013), 1–11, https://narf.org/nill/documents/nlr/nlr38-2.pdf

Lcrawfor, “James Monroe’s Trail of Tears,” The James Monroe Museum, Accessed April 15, 2023, Published November 28, 2022, https://jamesmonroemuseum.umw.edu/2022/11/28/james-monroes-trail-of-tears/

Colin Mustful is an independent historian, author, and publisher. His work, which includes five historical novels, focuses on the tumultuous and complicated periods of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in American history. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes compelling historical novels that are based on real events and people. As a traditional publisher, he works with authors who want to share important historical stories with the world. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

April 19, 2023

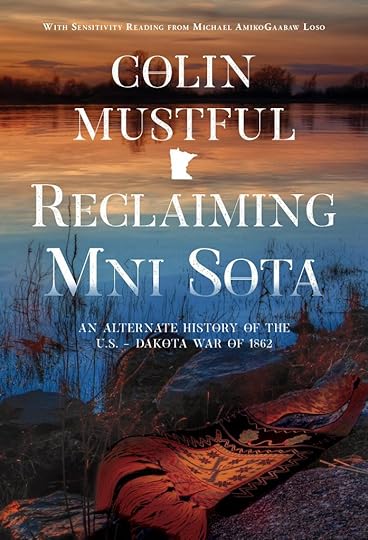

Cover Reveal! – Reclaiming Mni Sota Takes a New Look at History

In June 2018, I sat down to write a short story that saw a white settler and a Native Ojibwe cast aside their differences in the midst of war to become sympathetic to each other’s points of view. The story itself was inspired by my research into The U.S. – Ojibwe Conflict of 1862, an event that nearly led to the outbreak of war between the U.S. and Ojibwe at the same time the U.S. was at war with the Dakota. Well, after years of writing, revisions, and input from a variety of sources, the story is finally ready! And today, I couldn’t be happier to share with readers the cover design for Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. This stunning, colorful design, created by Christine Horner of The Book Cover Whisperer, not only represents the beautiful Minnesota landscape, but it symbolizes the definition of the word Minnesota. Derived from the Dakota phrase mni sota makoce, Minnesota is translated as “land where the waters reflect the clouds.” The cover image is a wonderful illustration of that phrase. Highlighted at the bottom is a gashkibidaagan, or a bandolier bag. With colorful beaded designs, bandolier bags have been created and used by Ojibwe people for centuries. It’s included on the cover because it also represents an important part of the story found within the novel.

Set for release on October 10, 2023, Reclaiming Mni Sota is my fifth novel and my first alternate history. I first took in interest in the the U.S. – Dakota War in 2007 while studying history at Minnesota State University, Mankato. After writing several essays about the U.S. – Dakota War, in 2010 I began work on my first novel, Fate of the Dakota, which was first published in 2013 under the title Thy Eternal Summer. Following Thy Eternal Summer, I wrote Grace at Spirit Lake, a historical novel about the Spirit Lake Massacre of 1857, and Ceding Contempt, a historical novel about the 1851 Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota.

In 2019, I published Resisting Removal, a historical novel about the Sandy Lake Tragedy of 1850. Departing from the Dakota of Minnesota, Resisting Removal centered upon the Ojibwe of Minnesota and Wisconsin while remaining on the same topic, time period, and style of writing. In order to publish Resisting Removal, a novel I completed while studying for an MFA from Augsburg University, I created History Through Fiction, a small literary press that publishes historical novels based on real events and people. Since its founding, History Through Fiction has published five novels from five separate authors. The press has also grown to include a podcast, editing services, online events, short stories, and writer workshops.

Reclaiming Mni Sota is a dual narrative written from the perspectives of Samuel, a white settler, who seeks his future in Minnesota, and Waabi, a Native Ojibwe, who mourns the loss of his homeland. But when progress clashes with tradition, Samuel and Waabi find themselves on opposite sides of a war years in the making. Thrown together by battle, they discover a common grief binds them. As they fight for their future, and the future of their loved ones, Minnesota is changed forever. Ultimately, Reclaiming Mni Sota confronts America’s history of settler-colonialism while illuminating the personal stories and heartrending choices that men and women, white and Native, were forced to make.

To stay up to date with author Colin Mustful and to learn more about Reclaiming Mni Sota, please subscribe to my monthly newsletter. To learn more about History Through Fiction please visit the website at historythroughfiction.com or subscribe to their monthly newsletter.

March 24, 2023

Author and… Traveler! – Sharing my trip to southern Utah

Hey readers! When I’m not researching, writing, editing, or publishing books, I love to travel—especially when it comes to hiking in the U.S. National Parks. This March, I drove to southern Utah to visit Arches National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and Bryce Canyon National Park. I’m back now, but I’d love to take a moment to share a little bit of my trip with you. No history, I promise!

A map of my trip to southern Utah

A map of my trip to southern UtahI started my trip in Moab, Utah, just south of Arches National Park. I began the day early by getting up before dawn and hiking to Delicate Arch, perhaps Utah’s most recognizable rock formation. I spent the rest of the day exploring the park by traveling up and down the main road and doing short day hikes along with one longer hike on an unmaintained “primitive” path. Then, that evening, I headed out of Moab to a camp just outside of Canyonlands National Park.

A hiker on a primitive trail in Arches National Park

A hiker on a primitive trail in Arches National ParkMy first night at (or near actually) Canyonlands National Park was a cold one. The temperature dropped below freezing. I know this because my water froze and my tent was covered in a thick layer of frost that morning. After waiting for the sun to rise and taking my tent down, I went into Canyonlands National Park and parked my car at the trailhead for Big Canyon Spring. This is because I was headed into the backcountry for a two night stay. This means that carried all my supplies on my back, including all food, water, sleeping necessities, and even human waste disposal bags!

For the next forty-eight hours I hiked the canyons and valleys of Canyonlands National Park. This was an amazing but somewhat stressful experience. On the one hand, I got to see some of the most incredible, expansive views a unique and beautiful landscape. On the other hand, I had to tread carefully through ravines, up steep canyon faces, and over/around large boulders. Finding my way wasn’t always easy and I had be very careful about each step I took. Often times, I found myself saying “Just don’t look down.” It worked!

A short video showing my view inside Cayonlands National ParkAfter finding my way back to my car, I made a long drive from Canyonlands to Escalante, Utah, where I had a very nice stay in warm and comfortable travelers lodge. I also used this opportunity to catch up on emails, wash my clothes, take a shower, and get some hearty food.

After a good night’s rest I drove south from Escalante down a long dirt road to the a trailhead called Hurricane Wash. That’s because I was doing another overnight hike, this time in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Specifically, I was hiking from Hurricane Wash to Coyote Gulch. I’m not exactly sure what a gulch is, but it was worth the hike. While there, I hiked along a meandering stream that was surrounded by high, arching canyon walls, each one bending inward to form a natural amphitheater. These natural amphitheaters stretched above me like a roof and around me like walls, enclosing me by about two-hundred seventy degrees! Plus, I saw some more remarkable arches such as the Jacob Hamblin Arch.

The Jacob Hamblin Arch

The Jacob Hamblin ArchAfter camping overnight in Coyote Gulch, I hike out via Hurricane Wash and back to my car. From there I drove back north and then west on my way to Bryce Canyon National Park. Originally, I had planned to camp at Bryce Canyon, but, because Bryce Canyon is at a high elevation, the temperature was in the 30s and the snow was piled high. So, I got a hotel room! It was still early in the afternoon when I arrived, so I explored as much of the canyon as I could by car. Then, the next day, I did a longer hike down into the canyon. Getting into the canyon was somewhat challenging because I had to use my crampons to hike over the ice and snow while being very careful not to slip down the steep slopes. But it was worth it because the unique rock formations of the canyon were amazing to see up close.

A view from the trail inside Bryce Canyon

A view from the trail inside Bryce CanyonI hiked up and out of the canyon in the afternoon, got back in my car, and headed north to begin my 1500 mile road trip back home. Along the way, I stopped and visited some friends in Colorado. Otherwise, the drive home was fairly uneventful.

Overall, it was a wonderful though challenging trip. The scenery was stunning and I’m grateful for the time, health, and resources to take such a trip. Now that I’m back, I’m focused on preparing for the launch of my novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota.

For more photos from my trip, visit my travel blog here.

March 2, 2023

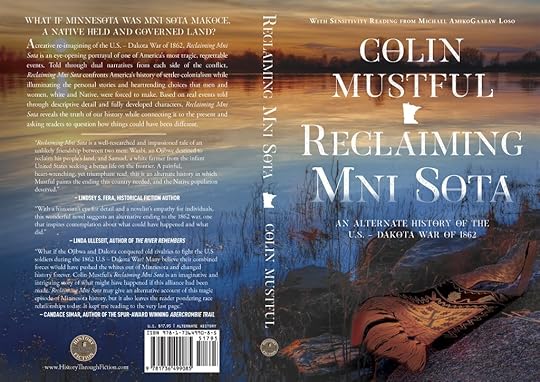

Book Feature – The Girl in the Thistles: A Novel of the Dakota Homeland

Hey Readers! I recently discovered a new novel by author S.K. Sandvig titled, The Girl in the Thistles: A Novel of the Dakota Homeland. The novel takes place during the U.S. – Dakota War and features a main character that has a Dakota/Scottish racial background. Although I’ve not had a chance to read the novel yet, it’s getting great reviews. Today, I’m going to share with you the synopsis, information about the author, and the first chapter of the novel. If you’ve already read it, or once you get the chance to, I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Synopsis:

Emilie, the 19-year old daughter of a Sioux mother and a Scottish father, finds her home destroyed when her clan is caught up in the US-Dakota war of 1862. Her mother is sent to a prisoner-of-war camp, and Emilie sets out to find her father, who has been missing since the beginning of the war. With help from two new and unlikely friends, Eustis and Anders, she begins a treacherous and emotional journey to track him down. Will she find him? Will her mother be set free? And will Emilie be able to rebuild the home she’s lost?

“This exceptional historical adventure is an inclusive experience, sharing actual life events woven through the lives of the settlers, the Dakota people, and one group so

important, but often overshadowed and overlooked, those of Minnesota’s mixed-blood people, the people of the transition – and in this story, those of Dakota and Scottish heritage. All that can be expected of an historical

adventure is more than achieved with The Girl in the Thistles.”

–Corinne L. Monjeau-Marz, Author of The Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862-1864

Author S.K. Sandvig

Author S.K. SandvigAbout the Author

S.K. Sandvig is a retired pastor with a passion for powerful stories of history that give voice to underrepresented events and people. He holds degrees in architecture, Biblical studies, and education and has been a general contractor. He has a special love for the wide-open spaces of the Dakotas (where he was raised) and Australia (where his children were born). He and his wife have four children and fourteen grandchildren who often ask him for more stories.

Novel Excerpt

Chapter 1 – The Locket

HILLHEAD, DAKOTA TERRITORY – June 1857

Sunlight filtered through the entrance of the tipi and danced gently across the face of the sleeping girl. She began to stir. Through slits in her eyes, Emilie Ferguson saw her mother hang an object on a peg and slip quietly out of the tipi. She turned to her side and looked around as the familiar shapes of her home came into focus. Leather pouches filled with beads, shells, and tools made of bone lay tucked away under the far edge of the tipi. A buffalo robe was draped over a willow bench next to two smoking pipes that hung on a pole. On the ground, below the pipes, were several journals and small bags of tobacco and dried scrapings of red willow bark, which Emilie’s grandfather would mix to make kinnikinnick. Their sweet and pungent odors made Emilie’s nose itch.

In the milky light of the lodge, a gold locket shimmered like a full moon on a foggy night. Emilie stared at it, admiring the outline of thistles etched on its gold-plated cover. Night Song, Emilie’s mother, had gone to wash in the lake and would be back soon. Quickly, Emilie peeled off her blanket and stood up to put the locket around her neck, letting it lie on her chest. It was only half of the locket, the front disc. The back disc, which her father wore under his shirt, had been engraved with the image of a Scottish manor house. Years earlier, for their wedding vows, Papa had pried the locket apart and given Night Song the front disc, and she in return had given him the back disc.

With slow motions, Emilie rubbed the raised imprint of thistles while listening for her mother’s return. She knew full well that her mother did not like her handling the locket, but she did it anyway.

The tipi was not large by Dakota standards. It was the same size as the one her grandparents had nearby. Twelve ivory-colored bison skins had been carefully stitched together with sinews. Night Song and Unci, Emilie’s grandmother, had decorated it with dabs of yellow and blue paint to represent stars in the night sky. On either side of the tent flap, they had embroidered porcupine quills, dyed purple, to represent thistles. Papa often told stories of the thistles of Scotland, his homeland, which were ‘good medicine,’ he claimed. Of course, there were thistles at Hillhead, and the sight of them would often get Papa singing,

O, the Thistle o’ Scotland was famous of auld,

Wi’ its toorie sae snod and its bristles sae bauld;

’Tis the badge o’ my country—it’s aye dear to me;

And the thocht o’ them baith brings the licht to my e’e.

On this particular morning, Papa, Jack Ferguson, was making his way home from the Hudson’s Bay Company headquarters, 500 miles to the north, at Fort Garry in British territory. He had been promoted numerous times and was now responsible for the growing trade on the Red River trails between Fort Garry and St. Paul. But like other Company men with native wives, Jack had chosen to make his home with his wife’s clan.

“Emilie, are you awake?”

Peering through a four-foot tunnel of thatched grass that protected the entrance to the lodge, Emilie could see her grandmother, a small Dakota woman in her sixties, hunched over a fire, making corn cakes in a frying pan and looking in Emilie’s direction.

“Yes, I’m coming,” said Emilie, lifting the locket from her neck and placing it on the peg. She bent over, slumped through the thatched-grass tunnel, and joined Unci at the cooking fire. Her grandmother plunked a fresh dollop of fat in the center of the frying pan and let it sizzle. While watching Unci cook, Emilie wet her fingers repeatedly and pressed hard on her wayward tresses to make them lie straight. She wanted so badly to have naturally straight hair like the other Sioux girls did. To her chagrin, her auburn hair was thick and unruly, which framed a heart-shaped face. Her green eyes, flecked with blue, were set wide apart under straight brow-lines, marking her with intelligence.

Emilie sat down next to her grandmother and nudged her with her shoulder. Unci smiled and nudged her back. Reaching into a bowl of cornmeal dough, Emilie made a lump and flattened it between her palms. She pressed it to the hot pan, watching liquid fat spatter around the soft edges of the dough. Then Unci pressed it flat with her spoon.

“You hungry this morning?” asked Unci.

“Enough for two!” said Emilie, scanning the camp to see who was up and about. Several were tending fires. Others were gathering sticks and wood. Thunder, their pinto pony, grazed quietly with three other ponies under a massive, peeling cottonwood. Beyond the trees, green prairies stretched as far as the eye could see. Morning was a time she cherished, especially when she was alone with Unci.

Suddenly, from beyond the circle of lodges, a trio of boys, almost out of breath, came running from the bottom of the coulee, shouting, “Bison! We found a herd of bison!”

The tallest boy, Leather Wing, saw Emilie and shouted out to her, “Bison. It’s time to hunt!” Emilie smiled back, surprised he had noticed her. All the girls admired Leather Wing, with his broad shoulders, strong arms, and calm demeanor.

Chief Red Iron hurried from the direction of his lodge and approached the boys. He wasted no words. “How many? How far? Where?” In the previous year, the Dakota had failed to find any bison, and crops had dwindled from lack of rain. Hunger was lurking in the villages. Fearful whispers were spreading, especially among the women of the four Dakota Sioux tribes. Leather Wing stepped forward and explained that there were at least fifty bison near the Lake of Storks.

“Re-Ipaham? Are they near Re-Ipaham?” asked the chief. Leather Wing nodded yes, and Red Iron turned to shout orders. The camp came alive with preparations for a hunt. Winona, Emilie’s fifteen-year-old cousin, came running.

“Red Iron needs twenty women to go help with the slaughter,” she said. “Are you coming?”

Emilie ran to her tipi, picked up her satchel, and handed it to Unci, who began packing it with fresh corn cakes and small strips of pemmican. Night Song returned from washing up and went quickly to the tipi to finish dressing. Moments later, she appeared at the fire, tying the ends of her braids with leather thongs.

“Ina, I’m going to join the hunt,” said Emilie. “Red Iron will need help butchering the bison.” Night Song said nothing at first, staring at Emilie.

Then she asked, “What happened to my locket? Were you wearing it again?”

Startled, Emilie stammered, “Yes, but—but I put it back. Have you heard? They’ve found a herd of bison. Can I go help with the hunt? Winona is going.”

“Well, my locket is gone.”

Surely it was a mistake! Emilie ran to the tipi to find the gold locket. She looked first at the peg on the pole, but it wasn’t there. Then she knelt on the ground and felt around the base of the pole for several minutes. It was nowhere to be found!

She hurried back to her mother and said, “I’m sorry, Ina. I can’t find it now. I hung it on the pole where you put it this morning. It has to be in the tipi somewhere. I’ll look for it when I get back.”

Night Song was quiet, but from the firm set of her mouth, Emilie could tell her mother didn’t believe her. In this moment, more than anything, Emilie wanted to go and join the hunt, and she needed her mother’s blessing. Night Song glared at Emilie, daring her to stop ‘lying.’ Unci looked away, embarrassed. Emilie’s throat tightened as she fought to keep the tears away. In recent months, Ina had been reprimanding Emilie more than usual, and now she refused to believe her daughter. Would she let Emilie join the hunt?

Unci spoke up. “Emilie knows how to use the knife now and where to make the cuts. Here, Emilie, take my knife. I think you should go and help with the butchering.” Emilie almost cried out with relief, but she remained quiet, waiting for Night Song’s response. Night Song said nothing. Instead, she turned and went back to the tipi.

“You better get going before Winona leaves you behind,” said Unci with an unwavering look in her eye. Emilie knew that Unci did not like taking sides, but as the matriarch of the family, there were times she had to pick a side, especially when disagreements erupted between Emilie and her mother. To Emilie, it seemed that in recent months, her mother was becoming more difficult to live with, and she wondered why. But she dared not speak of it to anyone, even Unci.

Emilie rushed to join Winona, who was lashing two long ash poles and one short cross-pole together with leather thongs to make a travois, which would carry a load of meat back to camp. They hitched the travois to Thunder and mounted him together and joined the other women who rode in single file.

Night Song and Unci watched the hunting party depart. “When you get back,” said Night Song to Emilie, “we must talk.” Emilie said nothing in return as the party rode over the edge of the hill and out of sight.

At high noon, the hunting party stopped to water their ponies at a stream and eat. Emilie slipped her sore and sweaty feet into the cool water. Winona opened Emilie’s satchel and reached in to grab some pemmican and cornbread. Pulling her hand out, she said, “Why did you bring this?” There in her hand was the gold locket!

Get the Novel!February 7, 2023

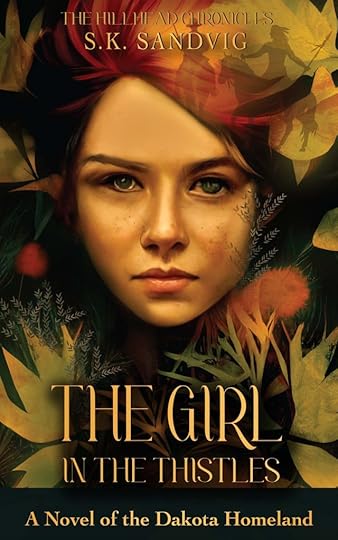

Fiction or Fantasy: Writing an Alternate History of the U.S. – Dakota War

In my upcoming novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota, Dakota and Ojibwe soldiers join forces to defeat the US army and exile the white population of Minnesota from the borders of the state. This, of course, is fiction. It is an alternate history of what could have happened. The goal is to help readers rethink history, and to reconsider what the results of our history mean for us today. The reality is a lot more complicated.

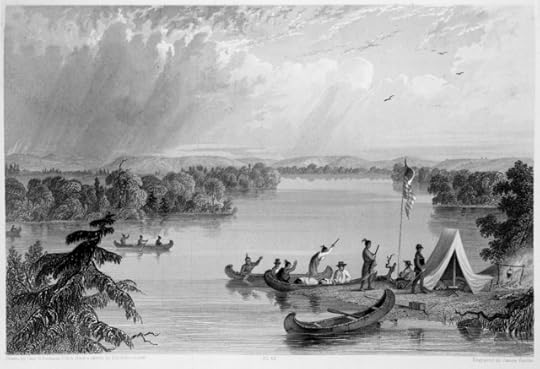

At the time of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, the Dakota and Ojibwe were traditional enemies. Beginning around the year 1750 with the Battle of Izatys, the Dakota and Ojibwe fought a one hundred year war for control over the regions of what are today northern and central Minnesota. It seems very unlikely then, that they would join forces against a common enemy in 1862. However, after succeeding his father in 1847, the Mississippi bands of Ojibwe were led by Bagone-giizhig the Younger, a charismatic, cunning, and unpredictable headman who was eager to regain the autonomy his people had lost. Then, with the emergence of Taoyateduta, or Little Crow, spokesman for the Dakota and military leader during the U.S. – Dakota War, rumors abound among the white populations that Bagone-giizhig and Taoyateduta would collude against the United States.

Some of these rumors came about because Bagone-giizhig did in fact communicate with Taoyateduta and other Dakota leaders in the form of written correspondence. As noted by Ojibwe historian Anton Treuer, Bagone-giizhig “dictated his thoughts in Ojibwe, then had them translated into English and mailed. Little Crow then had Bagone-giizhig’s letters translated into Dakota and relayed to him orally.” It’s also known that when war did break out against the white population of Minnesota, Bagone-giizhig threatened to join the Dakota. Also, as reported by Andrew B. Stone in a MNOpedia article, Bagone-giizhig encouraged the Ojibwe to fight by spreading “a false rumor that the U.S. government was planning to force all Ojibwe men to fight in the Civil War.”

In 1862, there were rumors among the white population that Bagone-giizhig, pictured on the left, and Taoyateduta, pictured on the right, would join forces in a military effort against the settler population.

In 1862, there were rumors among the white population that Bagone-giizhig, pictured on the left, and Taoyateduta, pictured on the right, would join forces in a military effort against the settler population. And so, while there is evidence to suggest that collusion was possible, there is more evidence that such a partnership was unwise and therefore very unlikely. Though Bagone-giizhig was indeed a charismatic leader with a growing following, he did not have the support of the Ojibwe leaders at Mille Lacs or Lake Superior. Rather, the Mille Lacs and Lake Superior leaders were set on supporting the US government and strengthening their alliance with state and federal officials. This is not to suggest that they did not wish to reclaim their land and autonomy, but by 1862 they determined that the best approach was through conciliation with the whites. This took on several forms.

Evidence that the Lake Superior Ojibwe did not support any kind of war effort against the United States can be found in the memoir Early Life Among the Indians by Benjamin G. Armstrong. Armstrong was a white man who moved to La Pointe on Madeline Island in the early 1840s. He married an Ojibwe woman and worked on behalf of the Ojibwe as an interpreter for many years. In his memoir, he notes that at the beginning of the Civil War columns of Union soldiers began appearing everywhere. This startled the Lake Superior Ojibwe. Therefore, in order to show that they were peaceful and cooperative, Armstrong and a delegation of nine Ojibwe leaders traveled to Washington DC in early 1862 to meet with President Lincoln. Their goal was one of appeasement. Also, as Armstrong wrote, “such a trip would give the delegation a rare chance to see the white soldiers and to thus impress upon their minds the futility of any further recourse to arms on their part.”

We know that the Ojibwe in the vicinity of Mille Lacs did not support the Dakota war effort, nor had any inclination to form an alliance, because at the outbreak of war they actively protected the white settlements. When the war began on August 18, 1862, panic spread throughout the state, and people fled to the nearest city or fortification. In central Minnesota, people fled to Fort Ripley. There, as noted by historian Anthony Godfrey, “Mille Lacs leaders arranged for some 700-750 warriors to march to Fort Ripley to highlight their support for the Americans.” The Mille Lacs leaders actually condemned the actions of Bagone-giizhig—who had orchestrated the U.S. – Ojibwe Conflict—and told the Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Dole that they would help put down the Dakota attacks. As a result, Commissioner Dole promised the Mille Lacs Ojibwe the protection of the US government and told them that they could stay upon their lands “without being molested if it was a thousand years.”

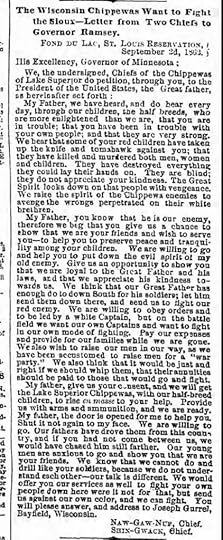

In this letter, written September 2, 1862, two Ojibwe leaders from Fond du Lac offer to help the US government in their war against the Dakota.

In this letter, written September 2, 1862, two Ojibwe leaders from Fond du Lac offer to help the US government in their war against the Dakota.The final and most obvious piece of evidence suggesting that the Ojibwe had no intention of colluding with the Dakota is demonstrated by a letter written September 2, 1862, by Chief Naw-Gaw-Nub and Chief Shin-Gwack, two leaders of the Fond du Lac Reservation, to Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey. In it, the two leaders expressed their support and gratitude for the US government while condemning the actions of the Dakota. They went on, not only to offer support in the war, but to beg for the chance, as they stated, “to show that we are your friends and wish to serve you—to help you to preserve peace and tranquility among your children.” In return, they wanted assurances that their families would be safe, that they would be allowed to fight in their traditional manner, and that they would receive all future annuities intended for the Dakota. They ended their letter with the bold reminder that “our fathers have drove them from this country, and if you had not come between us, we would have chased him still farther.”

With the benefit of hindsight we know that Ojibwe and Dakota did not join forces, and the Dakota were not able to overcome the US army during the U.S. – Dakota War. But it is clear that there was some political maneuvering at play. Whether it was Bagone-giizhig, Taoyateduta, or other various Ojibwe leaders, they all sought to protect their interests in the best way they thought possible. My novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota, is based on realities, but it’s an alternative to what we know happened. It’s an opportunity to reevaluate history from an imagined perspective. A perspective that, hopefully, broadens our view of the past and enlightens our view of the present.

Sources:

Anton Treuer, The Assassination of Hole-in-the-Day, (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2011).

Benj. G. Armstrong, Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong, (Ashland, WI: Press of A. W. Bowron, 1892).

Stone, Andrew. “Bagone-giizhig (Hole-in-the-Day the Younger), 1825–1868.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/bagone... (accessed February 5, 2023).

Wisconsin Chippewas Wish to Fight the Sioux: Letter from Two Chiefs to Gov. Ramsey, Chief Naw-Gaw-Nub and Chief Shin-Gwack, Chicago Times, Volume VIII, No. 28, 16 September, 1862.

Anthony Godfrey, Ph.D., Non-Removable and Self-Determined: A Social History of the Mille Lacs Ojibwe, 1640–1993, Prepared for the Minnesota Historical Society, January 1993.

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, editor, and publisher. His writing helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

January 5, 2023

Book Blurbs! – Just Another Part of the Author Experience

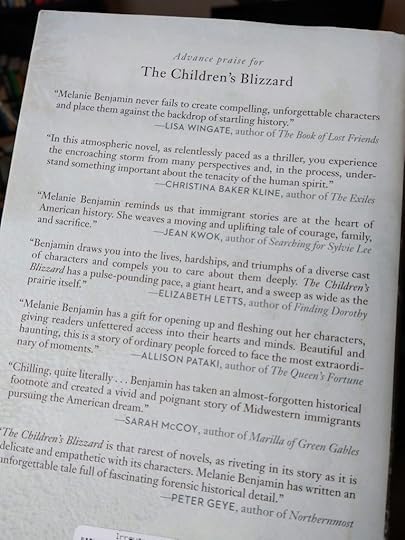

A long list of book blurbs on the back cover of the novel The Children’s Blizzard by Melanie Benjamin

A long list of book blurbs on the back cover of the novel The Children’s Blizzard by Melanie BenjaminThe book blurb. You know them. You’ve seen them. They’re those flowery statements of effusive praise on the back cover of books. They’re usually written by a “best-selling” or “award-winning” author who has written a book related to the book they are blurbing about. I don’t know how blurbs became so prevalent in the publishing industry (though you can read about the history here), but they’re ubiquitous now and it would be a mistake to publish a novel without them. And so getting book blurbs is another task you can add to the list of being an author.

Getting blurbs for a novel can be tricky for several reasons. First all, authors tend to be busy people with a lot of demands on their time and expertise—especially “bestselling” authors. It can be an imposition to reach out to them and many will be forced to say ‘no’ because they can’t fit it into their schedule. The timing of making blurb requests is also challenging. It’s important to get blurb requests early enough to be included in your book design. Also, you want to provide potential blurbers with a sufficient amount of time to read your book. With those things in mind it’s good to make blurb requests as early as possible, but, the problem is, your manuscript might not be complete. Somehow, authors have to find just the right moment to make blurb requests when their manuscript is finalized while the design phase is still to come.

My upcoming novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota, comes out October 10, 2023. Last month, eleven months before its release, I made a list of potential blurbers. That list was forty persons long. I made the list based on those authors and scholars whose endorsement I thought would lend credibility and authority to my novel. They include a handful of Indigenous authors, a long list of Minnesota-born authors, a few historians, and a few historical fiction authors I’ve gotten to know or work with over the years. Before reaching out to these authors, I wrote a template letter that I could copy/paste into my email and change as necessary depending on who I was reaching out to. If you’re interested, you can read that template here: Blurb Request

At the end of last month, I went ahead and made those blurb requests. The response has been good but not great. Of the forty requests I sent, I received a response from twelve of them. Of those twelve, six declined my request for a variety of reasons. Two authors have given me a ‘maybe’ response and four have said ‘yes.’

Making blurb requests is a challenging but necessary task. I’m grateful for those authors who were available and willing to take a look at my manuscript and potentially, if they enjoy the novel, provide me with a blurb that will capture the attention of my target audience. Two authors have already written blurbs and I’m happy to share those with you now.

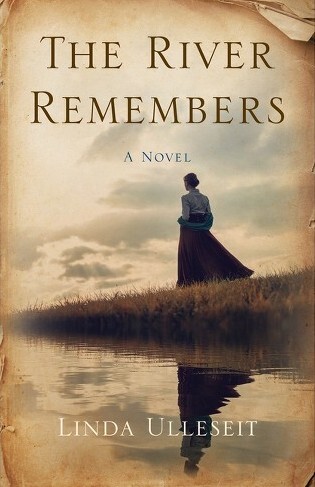

“With a historian’s eye for detail with a novelist’s empathy for individuals, this wonderful novel suggests an alternative ending to the 1862 war, one that inspires contemplation about what could have happened and what did.”

– Linda Ulleseit, author of The River Remembers

“What if the Ojibwa and Dakota conquered old rivalries to fight the U.S soldiers during the 1862 U.S-Dakota War? Many believe their combined forces would have pushed the whites out of Minnesota and changed history forever. Colin Mustful’s Reclaiming Mni Sota is an imaginative and intriguing story of what might have happened if this alliance had been made. Reclaiming Mni Sota may give an alternative account of this tragic episode of Minnesota history, but it also leaves the reader pondering race relationships today. It kept me reading to the very last page.”

– Candace Simar, Author of the Spur-Award winning Abercrombie Trail Series

On another note, I was recently asked to provide a blurb for Alina Rubin, author of the novel A Girl With a Knife. As an author, that’s an exciting thing. It shows that your name carries authority in the world of literature. Here is the blurb I provided for Alina…

“A thrilling debut by Alina Rubin, A Girl with a Knife has just the right amount of keen historical and medical detail, alongside a riveting story of a young woman determined to follow her dreams despite the odds stacked against her by a dogmatic, narrow-minded society.”

— Colin Mustful, author, historian, editor, and founder of History Through Fiction

I meant those words and if they lead to even one sale, to even one happy reader, I’ll be grateful for having provided them.

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, editor, and publisher. His writing helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

December 26, 2022

The Dakota 38 + 2 Memorial Ride

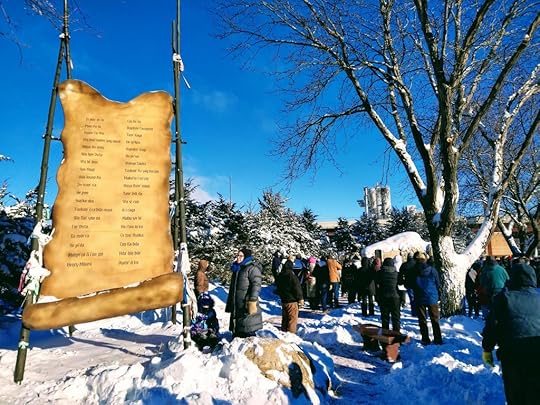

The Dakota 38 + 2 riders arriving at Reconciliation Park amid crowds of bundled up onlookers.

The Dakota 38 + 2 riders arriving at Reconciliation Park amid crowds of bundled up onlookers.Today, bitter cold winter temperatures could not prevent hundreds of people from gathering at Reconciliation Park in Mankato, Minnesota to welcome the Dakota 38 + 2 Memorial Riders and Runners. The event, started in 2005 by Lakota spiritual leader Jim Miller, commemorates the infamous hangings of 38 Dakota men that took place in Mankato on this day in 1862 in the aftermath of the U.S. – Dakota War. It also commemorates the hanging of Little Six and Medicine Bottle, two Dakota men were apprehended in Canada and hanged at Fort Snelling on November 11, 1865, for their roles in the U.S. – Dakota War.

The bitter cold temperatures could not keep people away from this important event that seeks to create awareness and healing regarding the mass hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota on December 26, 1862

The bitter cold temperatures could not keep people away from this important event that seeks to create awareness and healing regarding the mass hanging of 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota on December 26, 1862The riders of the memorial event traveled on horseback from the Lower Brule Reservation in South Dakota to Reconciliation Park in Makato, a journey of 330 miles. They began their journey on December 10 and traveled through bitter cold and harsh winter storms. The journey represents the exile from their homeland that the Dakota people endured in the months after the mass hanging. At the time, the Dakota, who were perceived as a violent threat by the majority white population of Minnesota, were banned from the state by law, forever.

In addition to the riders, a large group of relay runners also arrived at Reconciliation Park as a part of the memorial event. These runners began from Fort Snelling at midnight the day before, finally arriving at Reconciliation Park, a distance of about 90 miles, at 10:30am, December 26. The runners then proceeded to Land of Memories Park to conclude their relay. The run itself represents the long walk of those Dakota who, in November 1862, were forced to march from the Lower Sioux Reservation to Fort Snelling. Once they arrived at Fort Snelling, they were imprisoned in a concentration camp just below the fort where hundreds died during the cold, hard winter.

A sculpture of a scroll lists the names of the 38 men hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862.

A sculpture of a scroll lists the names of the 38 men hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862. The completion of the ride in Makato today was a joyous, reflective, and grief-filled occasion. The riders were welcomed with applause and celebratory drum beats and shrieks. This was followed by several speeches from Dakota elders who spoke of the pain this history has brought while also honoring those who endured such suffering. As a part of honoring them, each of the 40 names of those hanged were read aloud and remembered with a loud trill of the drums. Speeches from elders continued as they also honored those like Jim Miller who had the strength and foresight to create, organize, and maintain the annual memorial ride. Finally, they spoke of reconciliation. They spoke of continued acknowledgement of past wrongs while working together with state officials, like Governor Tim Walz and Lt. Governor Peggy Flanagan who were present, to create a future that heals the wounds of the past and incorporates the needs and viewpoints of all Minnesotans.

Crowds gathered at the statue of a buffalo listening to traditional Dakota music at the conclusion of the memorial event.

Crowds gathered at the statue of a buffalo listening to traditional Dakota music at the conclusion of the memorial event.

Once the speeches ended, the riders unsaddled their horses and departed with their trailers most likely toward warm food and rest. At the park, people huddled close to the buffalo statue while listening to Dakota musicians play their traditional songs. Others made their way to the library just across the street from the park where they watched a presentation of the Dakota 38 + 2 documentary.

With temperatures just barely above 0 degrees Fahrenheit, it was a cold day in Mankato. But that’s what makes us a part of this place. And that also makes us a part of its history. All of us. The events of the past have deep, meaningful, and real impacts for us today. There’s value in coming together, to see the past for what it was, and to push on toward the next steps—the next generations. The memorial riders and runners have truly shown us what it means to hurt and to heal. It’s an example I hope they continue to set. It’s an example I hope all Minnesotans can learn from.

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, editor, and publisher. His writing helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

December 14, 2022

The Legacy of a Great Lakes Missionary: Father Frederic Baraga

This granite cross on Minnesota’s North Shore is just one of many historical sites dedicated to Father Frederic Baraga. Image from Atlas Obscura.

This granite cross on Minnesota’s North Shore is just one of many historical sites dedicated to Father Frederic Baraga. Image from Atlas Obscura. Along Minnesota’s North Shore, in the town of Schroeder, there is a large granite cross inscribed with the year 1846 just below the name “Father Baraga.” The cross is a memorial to Irenaeus Frederic Baraga, a Roman Catholic missionary who, upon learning of a possible smallpox epidemic among the Grand Portage Ojibwe, set out across Lake Superior in a birch bark canoe, to aid them. On the way, Father Baraga and his paddler Louis Gaudin, were hit by an unexpected storm and blown ashore at the mouth of what became known as the Cross River. Initially, Father Baraga put a wooden cross where the canoe landed in gratitude for having survived the journey. Later, a granite cross was erected there as memorial to celebrate Father Baraga’s fortitude and faith.

The granite cross in Shroeder, Minnesota, is just one of many historical and memorial sites in the Great Lakes area dedicated to Father Baraga. For thirty-seven years, from 1831 to 1868, he lived among the Native Ojibwe people of the region, preaching to them, learning their ways, and fighting to protect them from illegal removal efforts.

Born on June 29, 1797, in present-day Slovenia, Frederic Baraga did not discover his desire to be of service in the church until after completing law school. Immediately after graduation, Baraga entered the seminary and became an ordained Roman Catholic priest on September 21, 1823. As a priest he worked tirelessly for the care and welfare of the people, but felt called to serve as a missionary among the Ojibwe in North America. In 1830, he was granted permission to travel to America and by the end of that year he arrived in New York.

After a short stint in Cincinnati, Father Baraga was sent to L’Arbre Croche, a large Ottawa settlement in the northern region of Michigan’s lower peninsula. It was there he began learning the Ojibwe language and collecting words for what would become the first written Ojibwe dictionary. In his first year at L’Arbre Croche, Father Baraga baptized more than 150 Ojibwe families and wrote Otawa Anamie-Misinaigan, a Catholic prayer book.

After spending a few years in the unceded territory of central Michigan, in 1835 Father Baraga was sent to La Pointe on Madeline Island (Mooniingwanekaaning-minis) where the Ojibwe had requested a Catholic Priest. Within two weeks of his arrival, Father Baraga and community members constructed the first Catholic church on the island. The congregation grew steadily and by 1841 a larger church was constructed.

This plaque on Madeline Island is located at the site of Father Baraga’s Catholic church which built in 1835.

This plaque on Madeline Island is located at the site of Father Baraga’s Catholic church which built in 1835. Over the subsequent years, Father Baraga established himself as an advocated for the Ojibwe people and their rights. During the long cold northern winters he walked hundreds of miles to various Ojibwe communities attending to their needs. These efforts earned him the nickname “The Snowshoe Priest.” Through a series of treaties, the U.S. government continuously sought to remove the Lake Superior Ojibwe from their lands. Using his background in law, Father Baraga also fought against these illegal removal efforts and helped the Ojibwe protect their right to use and remain upon their traditional homelands. On some occasions, Father Baraga would even purchase lands so that there would be no threat of removal, and then give the deed to Ojibwe leaders.

Throughout the years, though Father Baraga worked tirelessly and had few comforts or luxuries, he wrote, “I am happier in my little room than so many of those who live in gilded palaces.” Father Baraga, who was consecrated bishop on November 1, 1853, died January 19, 1868 in Marquette, Michigan. During the course of his ministry, he baptized and confirmed over 1,000 people in the region. On May 10, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI declared Father Baraga “Venerable.” Today, there is an effort to make him a Catholic Saint.

This blog post was inspired by the website “Father Baraga and the Ojibwe Natives.” The site takes an extensive look at the life and work of Father Frederic Baraga. But, more importantly, it examines the legacy of missionary work among Native populations during the 19th century while providing visitors to the site with a wealth of information and resources. One aspect of the site worth highlighting is its “Truth and Healing” section. Here the authors of the website acknowledge the damage Catholic actions have had on Native communities and culture while pointing visitors toward vital initiatives to resolve past and current harms.

In addition to providing valuable information about Truth and Healing initiatives, the website makes its own efforts to reconcile past harms while contributing to positive change. One such effort is made through offering Pipestone Crosses for sale. As stated on their website, “the purchase of this cross helps to keep the sacred tradition of carving pipestone alive which helps to repair and amend some of the challenges that came when the boarding schools were created.” The stone for each cross is quarried by Native Americans in Pipestone and is a tradition among Indigenous people of this continent going back 3,000 years. The crosses are carved by The Keepers of the Sacred Traditions of Pipemakers and “the purchase of this cross helps to keep the sacred tradition of pipestone carving alive which helps to repair and amend some of the challenges that came within the era of the boarding schools and the wrongs that have transpired.”

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, editor, and publisher. His writing helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master of Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

November 10, 2022

Book Review – The River Remembers by Linda Ulleseit

A heartbreaking but honest look at the lives of three women in the not-so-distant past, A River Remembers by Linda Ulleseit epitomizes historical fiction in its ability to share history as seen through the eyes of those whose stories are yet untold.

The novel opens with Samantha Lockwood and her brother, James Henry, as they arrive in the frontier town of Prairie du Chien. The year is 1834 and Samantha is a young woman who traveled all the way from New York state to escape the expectation that she would marry James Churchman, an up and coming politician that by Samantha’s own words, “bored her to tears.”

Next we meet Day Sets, a Dakota woman living in Eatonville on the shores of Mde Make Ska, a lake just west of Fort Snelling. Eatonville was created years earlier by the region’s Indian agent, Lawrence Taliaferro, as a means of acculturating the Dakota into white, Euro-American style living. It was called Cloud Man’s Village or Ȟeyáta Othúŋwe by the Dakota. Days Sets is daughter of Cloud Man and the wife of Agent Taliaferro whom she and the Dakota call Iron Cutter. Together they have a daughter named Mary.

Lastly, we meet Harriet Robinson, a fourteen-year-old girl brought to Fort Snelling as an enslaved person owned by Major Lawrence Taliaferro’s wife, Eliza. Harriet works in Major Taliaferro’s home alongside her fellow enslaved women, Ellie and Hannah, and one very playful Newfoundland dog named Nero. Born at a Virginia plantation, Harriet was sold at eight-years-old to the Dillon family of Pennsylvania. When their daughter, Eliza Dillon, married Lawrence Taliaferro, Harriet was given as a gift to the bride and brought with Eliza to Fort Snelling in the so-called “free territory.”

After introducing the characters, the story continues by alternating points of view in each chapter as seen through the eyes of these three women. Ulleseit’s approach has two main advantages: First, it provides the author three distinct social classes through which the world is filtered; and second, it shows the world through the eyes of women, a group whose viewpoint has been ignored by history for far too long.

As a historian, I was impressed with the breadth of research Ulleseit did to fill in all the details for this novel. 1834 was a pivotal moment in the history of the region and it involved a huge amount of people, events, and instrumental proceedings. Not a page goes by that the author does not include some fact or detail relevant to the course of history. Some are miniscule, and must have been difficult to sift out through the research. Others are major and therefore were not overlooked.

But Ulleseit does not hit the reader over the head with these historical facts. Rather, they are dropped in with the deftness and creativity of an author who’s done this before. While some of the author’s methods are noticeably contrived, it’s written well enough, and filtered through the eyes of the characters often enough, that the abundance of history does not distract from the indulgence of the story.

But, more important, perhaps, than the history, are the lives and challenges of these three women. Samantha, a white, well-to-do debutante, wants nothing more than to be able to make her own decisions. Day Sets wants a future for her daughter, Mary, while she recognizes the unjust and unfair compromises her family and her people must make as the white-world overtakes her own. Harriet wants her freedom. She wants a life where her labor is her own, not someone else’s, and where her daughter can live free of the restraints of slavery.

There’s so much to discover about these three women and the world in which they lived. To read The River Remembers is to see their struggles, their hopes, their dreams, and yes, even their mistakes, masterfully laid out on the page—all of it carefully crafted with real historical details. But what happens to the women of A River Remembers by Linda Ulleseit? You’ll have to read the novel to find out.

The River Remembers is set for publication on June 27, 2023. I received a free advanced reader copy of the novel from the author in exchange for an honest review. You can pre-order the book now at Bookshop.org and other retailers.

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

October 12, 2022

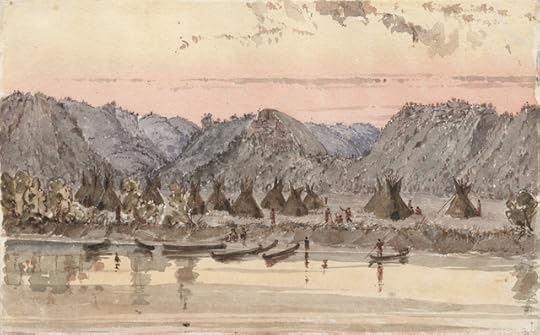

A Realistic and Colorful View of the Past – Seth Eastman’s Legacy to Minnesota

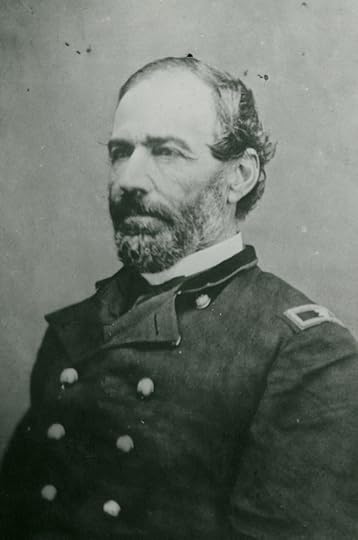

Seth Eastman was an artist and U.S. Army General. He was stationed at Fort Snelling 1830-1832 and again 1841-1848. Image courtesy of MNHS Collections.

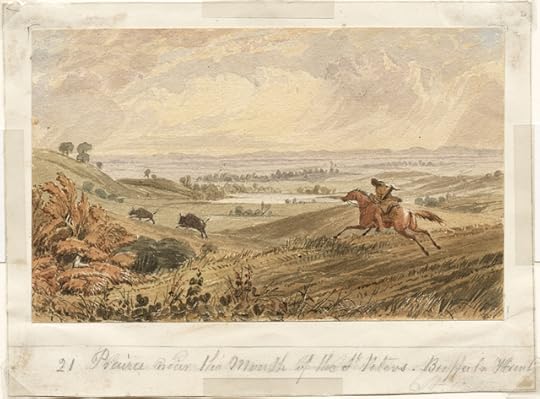

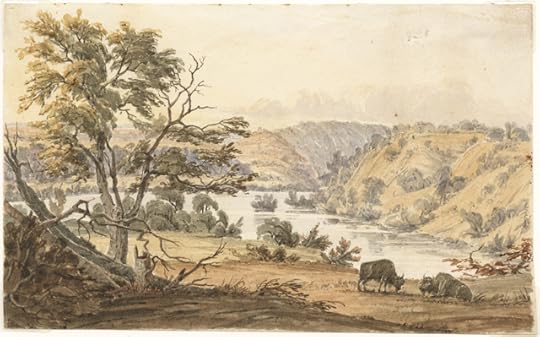

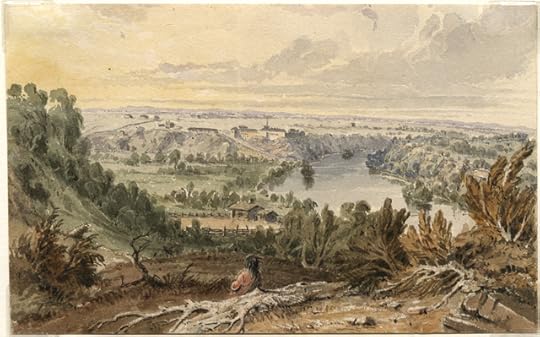

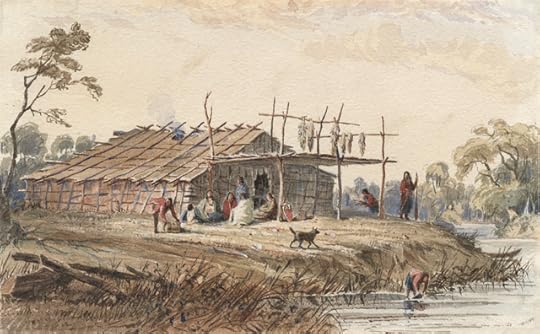

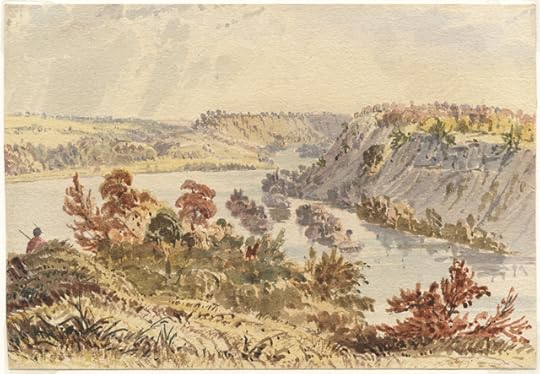

Seth Eastman was an artist and U.S. Army General. He was stationed at Fort Snelling 1830-1832 and again 1841-1848. Image courtesy of MNHS Collections. You’ve most likely seen the artwork of Seth Eastman before. In fact, if you’re reading this on my website, all you need to do is scroll up to see one of Eastman’s paintings on the title bar of this page. His work, if not brilliant, was certainly prolific and illuminating—much of it depicts the lives, landscape, and lifestyle of Native Americas during the mid-19th century. His most prominent work, in my opinion, are the many paintings he did of the people and landscape near Fort Snelling. The depths, colors, and details of his paintings provide a realistic view into Minnesota’s past that can’t be gained through historical documents. But who was Seth Eastman and why did he have such a penchant for portraying the region we now call Minnesota and its Native population?

Eastman grew up in Brunswick, Maine where he was born on January 24, 1808. He was the eldest of thirteen children and at age sixteen he enrolled in the United States Military Academy at West Point. While attending West Point, Eastman began to paint scenes featuring the daily life of local Native American tribes. Upon graduating in 1829, he joined the Army as a second lieutenant in the 1st Infantry Regiment.

In 1830, Eastman was assigned to topography duty on the frontier and spent three years at Fort Snelling, which, at the time, was a frontier outpost deep in Indian territory. Eastman soon learned the Dakota language and married Wakan Inajin-win (Stands Sacred), the fifteen-year-old daughter of Cloud Man, a Dakota chief. Together they had a daughter named Wakaŋ Tanka Wiŋ—or Mary Nancy in English.

Eastman left Fort Snelling in 1832 and declared his marriage ended. He was reassigned to West Point where he taught drawing for mapmaking from 1833 to 1840. While there, he met and married Mary Henderson, the daughter of a West Point surgeon. In 1841, Eastman returned to Fort Snelling where he was appointed commander. He, his wife, and their children remained there for seven years.

It was during this time he created numerous paintings and drawings of the Dakota and Ojibwe people living near the fort. This includes paintings such as “Distant View of Fort Snelling,” “Permanent Residence, Sioux,” “Wenona’s Rock on the Mississippi,” and many others. All of them share a clear style that offers a broad, idealistic view of the landscape in the background with a Native inhabitant or inhabitants in the foreground. The paintings and drawings are elegant and natural and show a harmonious view of the region before things drastically changed. Also, according to historian Julia Lavanger, “unlike his peers, Eastman mostly avoided romanticizing the Native people with whom he lived.” This is evident in sketches such as “Indian Woman Scraping a Hide,” that, like the title suggests, shows a Native woman going about daily chores without accentuating her Native culture in a stereotypical manner.

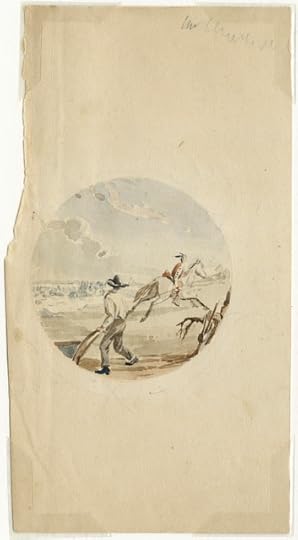

Indian Woman Scraping a Hide by Seth Eastman. Image Courtesy of MNHS Collections.

Indian Woman Scraping a Hide by Seth Eastman. Image Courtesy of MNHS Collections.

Design for Minnesota Territorial Seal by Seth Eastman. Image Courtesy of MNHS Collections.

Design for Minnesota Territorial Seal by Seth Eastman. Image Courtesy of MNHS Collections. In addition to his many paintings, Eastman also illustrated two significant texts. These include Dacotah, or Life and Legends of the Sioux Around Fort Snelling written by Mary Henderson Eastman, his wife, and Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, a six volume work by Henry Schoolcraft. For his wife’s book, Eastman completed twenty-one illustrations of Dakota life. For Schoolcraft’s, it’s reported by Lavanger that “he created eighty-five compositional drawings of Native life and more than 180 drawings of artifacts and maps.” According to another historian, Toby Thompson, for the entire six-volume work Eastman provided 275 drawings and watercolors.

In 1849, Eastman also helped design Minnesota’s Territorial Seal, a symbol that was the basis for the Minnesota State Seal. In it, a man (presumably a white farmer) plows a field while looking at a Native American on a horse who is riding away. In the background are the Falls of Saint Anthony.

Years after leaving Fort Snelling, in 1867, Eastman was commissioned by the House Committee on Indian Affairs to make nine paintings for the committee’s chambers. Those paintings, which were influenced by his early years at Fort Snelling and Fort Crawford, show Native peoples and culture in a natural and traditional manner. With the exception of one of the paintings, they show an era of peace and tranquility. They include works such as “Rice Gatherers,” “Indian Mode of Traveling,” and “Spearing Fish in Winter.” Today, those canvases still hang in a hearing room formerly used by the House Committee on Indian Affairs.

Eastman died in his home in Washington D.C. in 1875 while working on a painting of West Point. His work has provided future generations a much fuller view of an era of conflict and change and I for one am quite grateful for it.

Sources:

“Seth Eastman,” Wikipedia, Last Updated August 17, 2022, Accessed October 6, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seth_Eastman

“Seth Eastman: Pioneer & Painter: Overview,” Gale Family Library, Last Updated September 6, 2022, Accessed October 6, 2022, https://libguides.mnhs.org/eastman

Julia Lavanger, “Seth Eastman (1808–1875),” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society, Last Updated July 12, 2018, Accessed October 6, 2022, http://www.mnopedia.org/person/eastman-seth-1808-1875

Toby Thompson, “Perspective: Seth Eastman [1808–1875],” Western Art & Architecture, Published May 2016, Accessed October 6, 2022, https://westernartandarchitecture.com/articles/perspective-seth-eastman-18081875

All gallery images from the Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society.

TwitterFacebookYouTube