Colin Mustful's Blog, page 7

September 14, 2022

A Project Failed or a Lesson Learned: My Author Journey Continued

Note to Readers – This blog post is about a potential campaign to raise funds to create an Indigenous Writers Grant. I am still in the process of determining how or if to move forward with this. I will share more updates with you as things proceed. Thank you!

When I first started reading, researching, and writing about the U.S. – Dakota War back in 2007, I did not understand the very complicated nature of that history and what it means for us today. I just wanted to know what happened and why. My curiosity, along with a multitude of life’s random developments and circumstances, led me to share my research through essays, blogs, videos, presentations, an online course, and novels. Over time I’ve discovered that there is a lot more at stake than just the history itself. My two major observations are these: It matters how and why the history is being conveyed; and many of the people currently pursuing, consuming, and living the legacy of that history have deeply-rooted thoughts and feelings about what it means.

People often want to know why I’m interested in this particular history and whether or not my pursuit and portrayal of it is authentic and accurate. I can’t easily answer those questions, nor do I think it’s worthwhile to try. All that I can do is tell you what I’ve done and what I haven’t done. It is in that spirit that I share this blog post about my initial attempts to start an Indigenous Writers Grant. I’m not writing this post as any kind of indictment or judgment. It is merely done to share my story—my whole story so that you can learn, along with me, everything that’s involved in the process of being an author who writes about Minnesota’s complicated and tragic history. I don’t have any answers, and I have been wrong about many things. But I am always striving to learn and grow in my understanding to the degree that I am able.

Thy Eternal Summer was published by Tate Publishing in 2013. After learning more about publishing and the content I write about, I republished Thy Eternal Summer as Fate of the Dakota in 2016.

Thy Eternal Summer was published by Tate Publishing in 2013. After learning more about publishing and the content I write about, I republished Thy Eternal Summer as Fate of the Dakota in 2016. Louise Erdrich once pointed to the word “Conflict” in the title of my novel, Thy Eternal Summer: The U.S. – Dakota Conflict of 1862 and said, “There’s your first problem. The Dakota don’t view it as a conflict, they view it as a war.” That was eye-opening for me. It was, I’m sorry to say, the first time I stepped back to consider the history from a viewpoint other than my own. Since then I have learned dozens of invaluable lessons about how history has generally been portrayed and how it ought to be portrayed—that is, from a broader, more respectful, and more objective point of view. I have tried my best to incorporate those lessons in my own portrayal of The U.S. – Dakota War, the Sandy Lake Tragedy, and other related history. But having done that, and understood that, there is one thing I haven’t done. I haven’t taken any actionable steps toward reversing the long-lasting inequities created by historical wrongs, institutionalized by generations since, and accepted by generations present. Should I? I’m honestly not sure, but I’m willing to listen and find out.

That brings me to today and an idea I had to take those actionable steps. My idea was to create and fundraise for a $10,000 Indigenous Writers Grant. My thought was to raise funds for the grant through the sale of my upcoming novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternative History of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. This, I thought, would be an action I could take to use my writing to contribute to breaking down the systems in place that prevent and have prevented Indigenous storytellers from gaining access to the resources they need to share their side of the story—resources I have been privileged to utilize because of the legacies our history has created. You might expect that Indigenous and literary organizations would be eager to support and promote this cause. But that is not exactly the case. Before officially creating and launching the grant, I sought feedback from Indigenous community members. Then, after receiving little feedback, I sought advocates and donors from both Indigenous and literary organizations. The response has been underwhelming. I don’t wish to classify that as a negative thing, but it was disheartening.

Read the current draft of the grant’s GoFundMe Page.

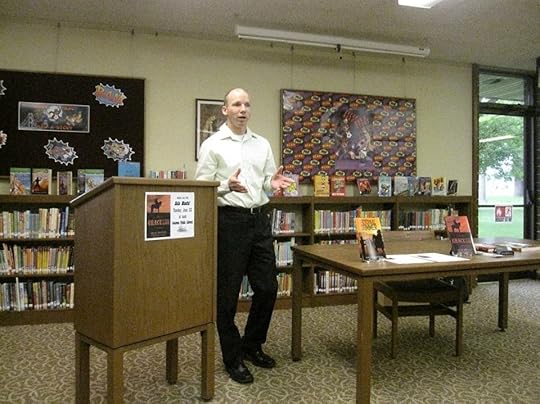

Speaking at a public library in June 2015, my first-ever book tour.

Speaking at a public library in June 2015, my first-ever book tour. As I continue down this path, I discover that there is a lot I don’t know and cannot anticipate. And that’s okay. I just don’t want to let it force me to change course until I’m ready. With all these things in mind, I’m going to share with you a list of all the people and organizations I have reached out to over the past six months seeking either feedback, partnership, advocacy, or donations for the creation and funding of an Indigenous Writers Grant. I’ve also reached out to a small number of organizations asking if they would accept donations that come from the sale of the forthcoming book. Below is that list and their response or lack of response. I will repeat that this is not an indictment. It is merely a way for me to share my story and the lessons I’m learning while also being completely transparent for those who truly are interested in the work that I do.

Name/OrganizationDate ContactedResponseBois Forte Tribal Government2/16/2022 & 4/6/2022We spoke over the phone. They said they would review the materials. Recommended using Patreon or GoFundMe for recurring donations. Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa2/16/2022 & 4/6/2022No ResponseGrand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa2/16/2022 & 4/7/2022No ResponseLeech Lake Band of Ojibwe2/16/2022 & 4/7/2022No ResponseLower Sioux Indian Community 2/16/2022 & 4/7/2022No ResponseMille Lacs Band of Ojibwe Indians2/16/2022 & 4/7/2022No ResponsePrairie Island Indian Community2/16/2022 & 4/7/2022No ResponseRed Lake Band of Chippewa Indians2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022No ResponseUpper Sioux Community2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022No ResponseWhite Earth Band of Minnesota Chippewa2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022No ResponseCircle of Indigenous Nations2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022Responded by writing, “Reviewing grant requests isn’t something I work on. My role at the University of Minnesota is to support current Native students.”Minneapolis American Indian Center2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022Spoke over the phone on 4/15/2022. Said they could not support the grant until I had support from Indigenous writers. Native American Community Development Institute2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022No ResponseMinnesota Indian Affairs Council2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022Said they would bring the information to their board of directors. I sent a follow email on 4/11/2022. I have not heard back since. UMD Department of American Indian Studies2/16/2022 & 4/13/2022No ResponseUMM Native American and Indigenous Studies2/16/2022 & 4/13/2022No ResponseAugsburg University American Indian, First Nations, and Indigenous Studies2/16/2022 & 4/11/2022Said they would support me “behind the scenes” but could not support me publicly because of their affiliation to the University. Augsburg University MFA in Creative Writing Program2/16/2022 & various other datesSaid they would be happy to publicize the grant but are not in the habit if championing certain ventures. Bemidji State University Indian Resource Center2/16/2022 & 4/13/2022No ResponseAll Nations Indian UCC4/13/2022No ResponseAmerican Indian OIC4/13/2022No ResponseCenter School2/16/2022No ResponseThe Circle 4/13/2022No ResponseYellow Medicine Review5/11/2022No ResponseIndigenous Literary Studies Association4/13/2022No ResponseWe Need Diverse Books4/13/2022No ResponsePuha Hubiya4/13/2022No ResponseMakoce Ikikcupi4/18/2022 & July 2022No ResponseDakota Author (unnamed here)4/18/2022No ResponseOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022Unable to help at this timeDakota Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022No ResponseOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022No ResponseOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022DeclinedOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022No ResponseOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022Unable to help at this timeOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022Respectfully declined and recommended reaching out to Dakota people. Ojibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022No ResponseOjibwe Author (Unnamed here)4/18/2022No ResponseTGI Frybread Native American Writers Group5/10/2022No Response826 MSP5/10/2022No ResponseLakes Area Writers Alliance5/10/2022No ResponseCracked Walnut5/10/2022No ResponseThe Jackpine Writers’ Bloc5/10/2022No ResponseLake Superior Writers5/10/2022No ResponseLeague of Minnesota Poets5/10/2022Said they would discuss it at the next Executive Committee meeting. Have not gotten back to me since. Midwest Fiction Writers5/10/2022No ResponseMN Speculative Fiction Writers5/10/2022No ResponseNational League of American Pen Women, Inc.5/10/2022No ResponsePlaywright’s Center5/10/2022No ResponseScreenwriters’ Workshop5/11/2022No ResponseTwin Cities Sisters in Crime5/11/2022No ResponseAscent5/11/2022No ResponseBlue Earth Review5/11/2022No ResponseConduit5/11/2022No ResponseGreat River Review5/11/2022No ResponseMidwest Review5/11/2022No ResponseMizna5/11/2022No ResponseRunestone5/11/2022No ResponseSt. Paul Almanac5/11/2022No ResponseSleet5/11/2022No ResponseThe Tower5/11/2022No ResponseUnder Review5/11/2022No ResponseWater Stone Review5/11/2022No ResponseWater Stone Review5/11/2022No ResponseWhistling Shade5/11/2022No ResponseLiterary Quicksand5/11/2022No Response11:11 Press5/11/2022No ResponseAfton Press/Calumet Editions5/11/2022Met in Person. Gave Support. Button Poetry5/11/2022Said they would like to connect directly but have not responded to my invitation to schedule a meeting. Cloquet River Press5/11/2022No ResponseCoffee House Press5/11/2022No ResponseGraywolf Press5/11/2022No ResponseHandtype Press/Square & Rebels5/11/2022Does not have available funds. Holy Cow Press5/11/2022No ResponseLiving Justice Press5/11/2022No ResponseMelange Books5/11/2022No ResponseMilkweed Editions5/11/2022Said they would forward my message to others within the press. I have not heard back since. Minnesota Historical Society Press5/11/2022No ResponseNew Rivers Press5/11/2022No ResponseNodin Press5/11/2022Yes, they will offer their support.Queen of Swords Press5/11/2022No ResponseRamsey County Historical Society5/11/2022No ResponseRed Dragonfly Press5/11/2022Does not have available fundsShipwreckt Books5/11/2022No ResponseSic Semper Serpent5/11/2022Said they would like to offer support but that they winding down operations. Sky Candle Press5/11/2022No ResponseUniversity of Minnesota Press5/11/2022No ResponseBeaver’s Pond Press5/11/2022No ResponseThe Loft Literary Center5/24/2022No ResponseMinnesota State Arts Board5/25/2022Member contacted is on leave until further notice. Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota Tribal Community 6/20/2022No ResponseNative Writers Circle8/6/2022No ResponseMigiziAugust 2022No ResponseGinew/Golden Eagle9/7/2022No ResponseSimily.coMay 2022Yes, they have offered their support. #mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:600px;} /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */ Subscribe to my monthly newsletter! * indicates required Email Address * First Name (function($) {window.fnames = new Array(); window.ftypes = new Array();fnames[0]='EMAIL';ftypes[0]='email';fnames[1]='FNAME';ftypes[1]='text';fnames[3]='ADDRESS';ftypes[3]='address';fnames[4]='PHONE';ftypes[4]='phone';}(jQuery));var $mcj = jQuery.noConflict(true);

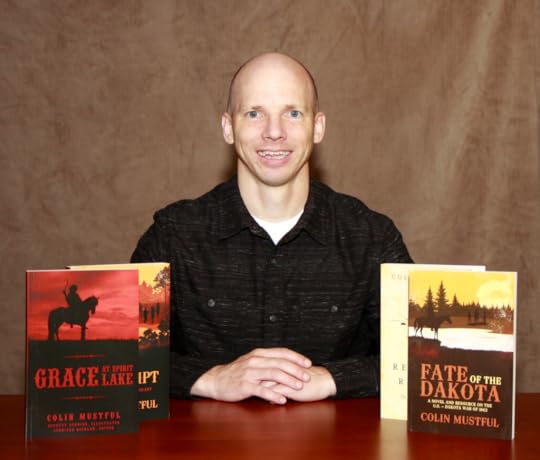

About the Author

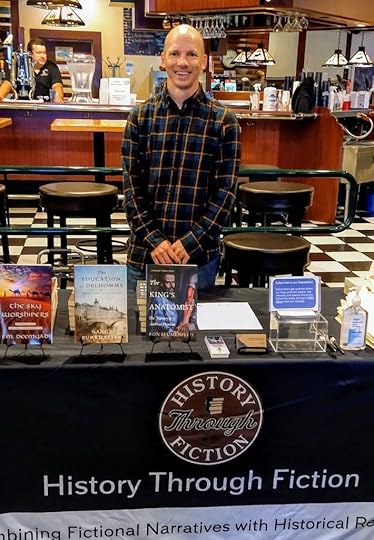

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

August 15, 2022

Highlighting the Defenders of New Ulm

In the summer of 2017, while traveling through western Minnesota, I stopped at the Acton State Monument—a small stone obelisk that, according to the inscription, marks the spot where the first blood was shed in the Sioux Indian Outbreak Aug. 17, 1862. While signing the visitor book I saw the name Curtis Dahlin just above my own. Dahlin, in my world, is a mega-celebrity. A Minnesota historian, Dahlin has written at least a dozen nonfiction books related to the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, all of which are extensively researched. As I learned from the visitor book, Dahlin and I live in the same city.

A few weeks after stopping at the Acton State Monument, I connected with Dahlin and made a visit to his home. We had a nice conversation, and I learned that he had gone to Acton while researching his next book, A Guidebook to the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 in Minnesota, which was published in 2019. Before leaving, Dahlin gave me a signed copy of one of his other books, Dakota Uprising Victims: Gravestones & Stories. The book is a remarkable feat of research. In it, Dahlin tracks down the surviving gravestones and markers of those white Minnesotans who were slain during the U.S. – Dakota War. While the book is remarkable in its breadth of geographical and biographical data about the victims, Dahlin points out that it only represents “one-third of the estimated 600 white settlers and soldiers who were killed by the Dakota” and “this means that about two-thirds of the victims lie in unmarked graves.”

Attack on New Ulm During the Sioux Outbreak, August 19-23, 1862

Attack on New Ulm During the Sioux Outbreak, August 19-23, 1862Anton Gag, 1904, MNHS Collections

The Minnesota Historical Society estimates that more than 600 whites were killed during the war. However, as noted by Dahlin, that number may have been much higher. And, according to a 42-page list of victims published by the Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims, that number could be as high as 2000. But I don’t wish to argue the number of casualties for any one side of the conflict, nor the long-lasting effects on the people, places, and families—Native American and White—in the aftermath of the war. What I do wish to acknowledge, is that there were many brave, selfless people who gave their lives in defense of their communities. And because I’ll be speaking at the 2022 U.S. – Dakota War Commemoration in New Ulm, Minnesota, I’d like to highlight a few defenders of New Ulm who gave the ultimate sacrifice when the Dakota attacked the town on August 19 and August 23. The motley crew of defenders, most of whom were farmers, merchants, and volunteer militia, successfully repelled the Dakota attacks and then made the difficult decision to evacuate the town on August 25 and burn down the remaining buildings. The three defenders highlighted here are included in Dahlin’s book, Dakota Uprising Victims: Gravestones & Stories.

William Bigelow Dodd

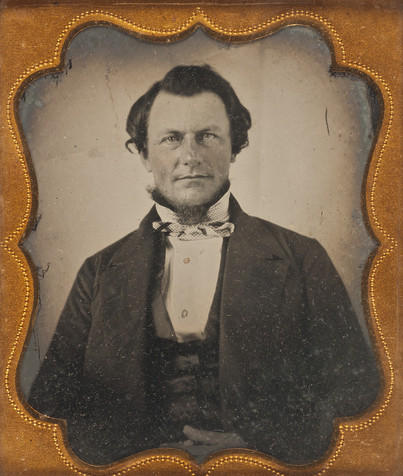

Capt. William B. Dodd, second in command at New Ulm, was shot and killed while defending New Ulm from the Dakota attack on August 23, 1862. Image from MNHS Collections http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10454876

Capt. William B. Dodd, second in command at New Ulm, was shot and killed while defending New Ulm from the Dakota attack on August 23, 1862. Image from MNHS Collections http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10454876Captain William Bigelow Dodd was the second in command of the forces defending New Ulm. In the afternoon of August 23, 1862, Dodd, along with a small company of men, charged the Dakota lines in order to allow what they believed were white reinforcements to enter the town. What they thought were reinforcements, however, were actually Dakota dressed up like white men. After recognizing the trap, Dodd hurried back to the safety of the town barricades but was shot three times during his retreat. He made it back to town but died shortly thereafter.

Dodd was born April 21, 1811 in Bloomfield, New Jersey. He came to Minnesota when it was still just a U.S. territory and is credited with founding the town of St. Peter. He was a member of the volunteer militia that traveled to Spirit and Okoboji lakes to save and protect white settlers in the immediate aftermath of the Spirit Lake Massacre of 1857. In 1854 he was commissioned to oversee the construction of a new military road from Fort Atkinson, Iowa to Fort Snelling in Mendota, near St. Paul, Minnesota. Today, Dodd Road in Eagan is named after him.

Jacob Castor

Jacob Castor was a baker living in New Ulm who was mistaken for a Dakota and killed by friendly fire. As reported by Dahlin, on August 23 Castor, who also acted as a soldier in Captain John Bellm’s company, was baking bread to feed the New Ulm Defenders. As evening approached, rain began to fall. When Castor left his bakery with baskets of bread, he covered his shoulders and head with a blanket, a common manner of dress for the Dakota Indians. In the dim light of dusk he was mistaken for an Indian and shot. He got back up and tried to make it to his home, but was shot again. He died the next morning. Castor, an immigrant from Prussia, was just 30-years-old.

William Luskey

William Luskey was a member of the LeSueur Tigers, a militia group under Captain William Delaughter that came to the relief of New Ulm once word was received that the town was under attack. By the time of Dakota’s second attack on August 23, the population of New Ulm swelled to more than 2000 people as refugees and reinforcements, like the LeSueur Tigers flooded the city. The defenders built makeshift barricades around the city center and posted men at outlying buildings. Luskey and a small group of men were posted at the Robbecke Mill because it was a tall structure that provided an excellent defensive position. During the hotly contested battle, some of the men left the mill for other positions. The thirteen that remained, one of which was Luskey, finally decided to leave and burned the mill down upon their departure so that it could not be used by the Dakota. Luskey was killed sometime thereafter, but it isn’t known exactly how or when. Luskey was one of twenty-six people killed defending New Ulm that day and one of six LeSueur Tigers killed.

William Luskey was born in Ireland in 1815. His wife Johanna and their children lived on a farm in Tyrone Township in LeSueur County. He was 47-years-old at the time of his death.

Sources:

Curtis A. Dahlin, Foreward by Alan R. Woolworth, Dakota Uprising Victims: Gravestones & Stories, (Edina, Minnesota: Beaver’s Pond Press, 2007.

“Aftermath: The U.S. – Dakota War of 1862,” Minnesota Historical Society, Accessed August 12, 2022, https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/a...

“Those Who Served,” Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims: 1862 U.S. – Dakota War in Minnesota, Accessed August 12, 2022, http://www.dakotavictims1862.com/tomb...

Visit My Online Store!

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:600px;} /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */ Subscribe to my monthly newsletter!* indicates required Email Address * First Name (function($) {window.fnames = new Array(); window.ftypes = new Array();fnames[0]='EMAIL';ftypes[0]='email';fnames[1]='FNAME';ftypes[1]='text';fnames[3]='ADDRESS';ftypes[3]='address';fnames[4]='PHONE';ftypes[4]='phone';}(jQuery));var $mcj = jQuery.noConflict(true);

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:600px;} /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */ Subscribe to my monthly newsletter!* indicates required Email Address * First Name (function($) {window.fnames = new Array(); window.ftypes = new Array();fnames[0]='EMAIL';ftypes[0]='email';fnames[1]='FNAME';ftypes[1]='text';fnames[3]='ADDRESS';ftypes[3]='address';fnames[4]='PHONE';ftypes[4]='phone';}(jQuery));var $mcj = jQuery.noConflict(true);

August 2, 2022

I’ve got a Newsletter!

Hey Readers,

I’d like to invite you to join my brand new monthly newsletter! Until now, I’ve been connecting with readers through blog subscriptions. But, beginning September 1, 2022, I’ll be sending out a monthly newsletter on the first of each month.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; } /* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block. We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */ Subscribe to my BRAND NEW monthly newsletter!* indicates required Email Address * First Name * (function($) {window.fnames = new Array(); window.ftypes = new Array();fnames[0]='EMAIL';ftypes[0]='email';fnames[1]='FNAME';ftypes[1]='text';fnames[3]='ADDRESS';ftypes[3]='address';fnames[4]='PHONE';ftypes[4]='phone';}(jQuery));var $mcj = jQuery.noConflict(true);Things my newsletter will include…

Updates about my forthcoming novel, Reclaiming Mni Sota: An Alternative History of U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 Links to new blog posts, YouTube videos, and other contentLinks to old blog posts, YouTube vides, and other content — Stuff you may have missed!News about online and in-person eventsDiscounts and sales on my booksUpdates and content from my press, History Through FictionThank you so much for your patronage and support over the years! I can’t wait to share with you what’s next. And for those who have just discovered me, I know you’ll find a lot enlightening, thought-provoking, and enjoyable content that I’ve created. Please join me as I continue my journey to learn more about the past and what it means for us today.

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

July 15, 2022

Accountability and Revitalization – The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report

It’s no secret that throughout the history of the United States, Federal Indian policy, in most cases, has had devastating, deadly, and long-lasting effects on Native American populations. Some policies were made out of ignorance or expediency, others out of outright greed and malice. One such policy that was unequivocally brutal was the establishment of Indian Boarding Schools which was part of a larger effort to forcibly acculturate Native peoples into the dominant white American society.

The devastation wrought on Native communities, especially children, was recently acknowledged by the U.S. Department of the Interior upon publishing the first volume of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. The 100-page report is both objectively factual and subjectively damning. It states that “between 1819 and 1969, the United States operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states, including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii.” The report further acknowledges that it is “based on examination of records under its control” meaning that there are numerous institutions “including Indian day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages, and stand-alone dormitories that may have [been] involved [in the] education” of Native American children but were not under federal control.

Among its findings, the report “has identified approximately 53 marked or unmarked burial sites” across the Federal Indian boarding school system and suggests that, upon further investigation, the Department “will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands.” Overall, the report concludes that the Indian boarding school system used “militarized and identity-alteration methodologies to assimilate” Native American children through education. Some methods of forced acculturation include forcing Indigenous children to change their names, cut their hair, eliminate their languages, religions, and cultural practices, and perform manual labor. All of this, the report acknowledges, was done with the broader goal of intentionally dispossessing Native peoples of their land while avoiding war.

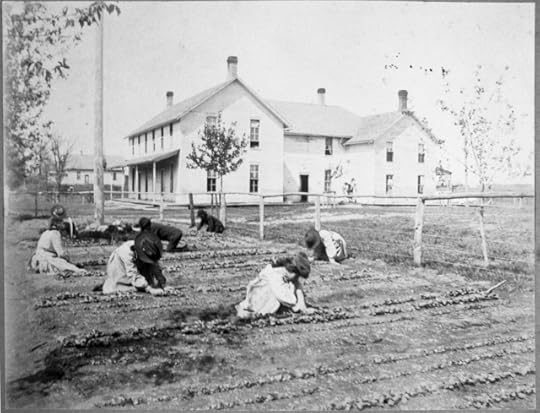

Children working in the gardens at an Indian Boarding School in Minnesota. The report identified 21 federally funded Indian Boarding Schools in the state of Minnesota. Photo from MNHS Collections – http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10830856

Children working in the gardens at an Indian Boarding School in Minnesota. The report identified 21 federally funded Indian Boarding Schools in the state of Minnesota. Photo from MNHS Collections – http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10830856 One of the most important elements of the report is the accountability the Department accepts for the damaging assimilation policies of the past. It states, “The Department must fully account for its role in this effort and renounce forced assimilation of Indian Tribes, Alaska Native Villages, and the Native Hawaiian Community as a legitimate policy objective.” And, the report takes accountability further by promising actions aimed at restoring and revitalizing Native communities, language, and culture. First and foremost, the Department articulates their commitment to complete a full investigation of the Federal Indian Boarding School System while encouraging non-federal institutions related to the education of Indian children to submit their records to the Department. The report goes on to list a number of specific actions the Department will take to support Native communities. Some examples include advancing Native language revitalization, developing a Federal repository of records involving the Federal boarding school system, documenting the Federal Indian boarding school attendee experience, and supporting the protection, preservation, reclamation, and co-management of sites across the Federal Indian boarding school system.

While this is a remarkable step forward for a government that has marginalized and destroyed Native people and cultures for centuries, it should be noted that similar reports have been published in the past. One such report, published in 1928 and titled The Problem With Indian Administration, determined that Federal Indian policy had been detrimental to Native Americans while calling the system of Indian boarding schools “grossly inadequate.” Then, in 1969, Senate Report 91-501, commonly known as the Kennedy Report, declared Indian education a “national tragedy” and said “the dominant policy of the federal government toward the American Indian has been one of coercive assimilation” and the policy “has had disastrous effects on the education of Indian children.”

It would be impossible to account for all the wrongs done to Native communities through Federal Indian policy over the centuries, but the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report is an important step toward acknowledging those wrongs and committing to their reversal. While such acknowledgment has been done in reports of the past, those reports did lead to valuable advancements in Native governance such as the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, and the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act. As the Department of the Interior’s investigation continues, it will reveal more damning evidence, but will also lead to positive change for millions of Native American peoples so that they and their communities can heal, thrive, and prosper.

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

June 29, 2022

Author Update – June 2022

Dear Readers,

In my last update, written in January 2022, I told you about the query process and my attempts to find an agent or publisher for my manuscript, Reclaiming Mni Sota. Today, I’m going to update you on where I’m at in the publication process and what to expect moving forward.

Since January, I’ve continued to submit my manuscript to agents and publishers. However, it’s not been the main focus of my time. So far, I’ve submitted to about fifty agents and publishers. I’ve received about thirty rejections and have not heard back from the others. In March, I received a full manuscript request from a small press called Foundations Book Publishing. Usually, upon submission, authors are asked to provide a sample of their work. A full request is encouraging because it means the publisher was interested in the sample and wants to review the manuscript in its entirety. I have not heard back from Foundations since submitting the full manuscript, but it’s only been a few months.

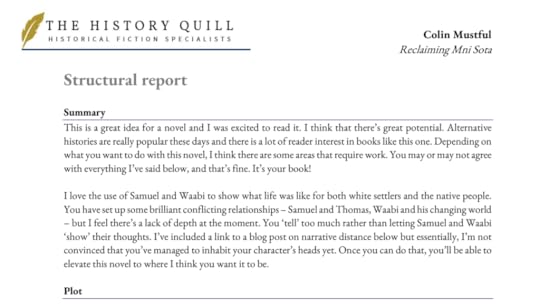

The first half-page from my Structural Report

The first half-page from my Structural ReportIn the meantime, however, I hired a company called The History Quill to provide me with a Structural Edit of my manuscript. This is similar to a developmental edit but not quite as extensive. A structural edit, as described on their website, “includes a comprehensive assessment of your manuscript and an evaluation of each individual chapter, drilling down into the text to identify problems at a granular level.” This was exactly what I received—a fifteen-page report that outlined the areas for improvement in my manuscript as it relates to plot, point of view, character development, and so forth. This was hard to read, but after sitting with it for a few days, I took notes on the recommendations and determined that there are several things I can do to improve my narrative. That’s why, this summer, I’m making revisions to the manuscript. The story will remain essentially the same, but I plan to do a lot to improve the characters and their relationships with one another. My goal is to finish my revisions by the end of August.

The crowd gathered to hear me speak in Peterson, Minnesota, on Sunday, June 26

The crowd gathered to hear me speak in Peterson, Minnesota, on Sunday, June 26This summer I’m also undertaking several speaking engagements. For instance, on June 16 I traveled to Winnebago, Minnesota, to talk about the history of the Ho-Chunk people. On June 20, I traveled to Ivanhoe, Lake Benton, and Tyler, Minnesota, to talk about the history of the U.S. – Dakota War. On June 26, I traveled to Peterson, Minnesota for the grand opening of a new wing of their museum. There, I talked about the history of a Root River Trail, a 42-mile recreational path that had once been an Indian trail. I’ll be giving various other presentations in the months of July and August. I’m very grateful for these events because it gives me a chance to engage with my audience, sell my books, and earn an income through speaking fees. I’ve definitely enjoyed the events so far, and I’m looking forward to more.

With all that said, my major focus over the past year plus has been on the establishment and growth of my publishing company, History Through Fiction. At this point I can proudly say that it is indeed growing. I’ve now signed five authors to contracts, including Alina Adams, a NYT-bestselling author whose most recent title, The Nesting Dolls, was published by HarperCollins. Her current novel, My Mother’s Secret: A Novel of the Jewish Autonomous Region, which comes out November 15, is now available for pre-order.

In addition to publishing historical novels, History Through Fiction is now publishing historical fiction short stories. The stories are published digitally to our member-only content area where our members can download and read them whenever they like. I’m also producing a podcast which has been a wonderful, but time-consuming experience. Since May I’ve recorded about a dozen interviews with historical novelists and I have about a dozen more scheduled in July and August. The interviews will be published as a weekly series for Season 3 of History Through Fiction: The Podcast beginning in September. And finally, I’m the moderator for What’s New in Historical Fiction, a regular panel series featuring historical novelists with new and upcoming titles. This has been a great experience and the panels allow me to connect with other historical novelists while growing my audience of subscribers. If you don’t already know about my publishing company History Through Fiction, I highly encourage you to check it out and to subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

I met the founders of Simily, a short story publishing platform, at the AWP Conference in Philadelphia. Then, I had wonderful conversation with them on my podcast. You can listen to it here: https://www.historythroughfiction.com/podcast/simily

I met the founders of Simily, a short story publishing platform, at the AWP Conference in Philadelphia. Then, I had wonderful conversation with them on my podcast. You can listen to it here: https://www.historythroughfiction.com/podcast/similyThis year, I’ve also been doing freelance editing. I joined the Editorial Freelancers Association and the ACES: The Society for Editing. This has allowed me to gain additional training and helped me to connect with writers looking for editors. So far, I’ve completed three freelance editing contracts, and I’m currently working on two others. I’ve received some great testimonials for my work, which you can read here along with a description of services, and it’s allowed me to bring some income into my company. Since I’ve been working at this for so many years, it’s very rewarding to be able to help other writers while also generating some income.

As you can see, I’m immensely busy pursuing my passions in history, writing, and publishing. I’m constantly coming up with new ideas, networking with other authors and publishers, and interacting with freelancers, contractors, and publicists. My days are filled with a variety of endeavors from writing, to editing, to interviewing, to social media management, to networking and much more! I’m still working my day job as a para educator and my weekend job as a pizza delivery driver. It’s definitely hard work, but I do enjoy it and I’m beginning to see the fruits of my labor. Thank you for being a part of this journey. I can’t wait to share my next novel with you along with everything else that lies ahead.

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

June 1, 2022

Once a trail, always a trail: A brief history of the Root River Trail

The Root River Trail is a 42-mile paved path meandering through the driftless region of Southeastern Minnesota from Fountain to Houston. Set among the limestone bluffs of the Root River, today the trail is used for biking, jogging, walking, in-line skating, and cross-country skiing. But before becoming a recreational path in 1986, the trail had many other uses. Until 1979, railroad tracks cut through the steep hills and forested ridges of the valley. And those railroad tracks, built in the 1860s, were laid atop a carriage path. Before the carriage path, there was a Native American trail running through the valley.

https://www.rootrivertrail.org/root-river-trail-system/

https://www.rootrivertrail.org/root-river-trail-system/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Root_River_(Minnesota)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Root_River_(Minnesota)The Root River is an 80-mile tributary of the Upper Mississippi River Valley flowing eastward through what is today Southeastern Minnesota. The Root River watershed covers 1,670 square miles of driftless riverine terrain encompassing six Minnesota counties. It is a beautiful, lush region unique for its geology and geography as part of the Driftless area—a place characterized “by the absence of glacial drift deposits, the sculpted topography, and the presence of the ancient limestone immediately beneath the soil and in cliff outcroppings.”

The river has been known by many names. Called “R. des Kicapous” on a 1703 map, it did not take on the name Root River until the early 1800s. Explorer Zebulon Pike referred to the river as Racine in 1805, but by 1817, when Stephen H. Long led an expedition through the region, it was called Hokah or Root. Hokah is the Dakota word for root. In 1843, Joseph Nicollet referred to it as Hokah while in 1852, missionary to the Dakota Stephen Riggs called it Hutkan. The river has also been called Cah-he-o-mon-ah, or Crow river by the Ho-Chunk. Interestingly, according to historian Lafayette Bunnell, the Dakota “also called Root river Cah-hay Wat-pah, because of the nesting of crows in the large trees of its bottom lands.”

Prior to American settlement, the Root River Valley was dominated by the Dakota and a dynasty of successive leaders named Wabasha. According to historian Charles C. Wilson, “The Wabasha dynasty claimed and exercised jurisdiction over the eastern bank of the Mississippi opposite Winona, for at least twenty-five miles either way, up and down the stream, and over the islands therein.” Wilson went on to write that “within that territory the reigning Wabasha was in older times the lord of all. On the lands drained by the Root river or the Zumbor, no Indian could camp or hunt without his consent.” It’s also known that the elder Wabasha, or Wabasha I, died on the banks of the Root River in 1806 about 25 miles southwest of present day Winona.

The actual route of a trail through the Root River Valley prior to the building of a railroad is hard to determine. However, written evidence from expeditionaries like Stephen H. Long make it clear that common trails in the region did exist. In his 1817 expedition from Prairie du Chien to the Falls of St. Anthony, Long reports that he had a “good” Native American guide that led them on the most direct trail where water could not be used for travel. This included at least one crossing of the Root or Hokah river.

De-Coo-Dah guided researcher William Pidgeon along trails through the Root River Valley

De-Coo-Dah guided researcher William Pidgeon along trails through the Root River ValleyIn the 1840s, researcher William Pidgeon met and interviewed a Native American man from the Ioway tribe named De-Coo-Dah living near Prairie la Crosse. Pidgeon was in search of Native mounds with De-Coo-Dah as his guide. In his 1858 book, Traditions of De-Coo-Dah and Antiquarian Researches, Pidgeon left the following account:

“We descended the Mississippi from my Trading Post on Root River, to the Western Terminus of what he termed the highway of Nations, but better known in modern time as the old Indian trail, running from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River. I have but little doubt, however, that this Trail occupies the best natural line for travel between those two Great Waters, and has been used for very many ages by the ancient inhabitants of those regions, and will continue to be used as the great thoroughfare in time to come to the full consummation of its ancient and dignified title; that it will lead along through the Holy Land the sons of all Nations, presenting to their view the remaining relics of a custom wants Universal, but now to all alike unknown.”

This is some of the most direct evidence of a Native American trail traveling east to west through the Root River Valley. And, in hindsight, Pidgeon was correct in asserting that the trail would “continue to be used as a great thoroughfare.”

Further evidence of a trail prior to white settlement was provided by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources when, in 1979, they conducted a study of the recently abandoned railroad route through the Root River Valley. In their report of the study, the DNR made the following conclusion:

“A trail which follows two main routes of prehistoric and historic travel—the Root River itself and the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad bed—follows two major arteries of communication which encompass much of the past of this area. The proposed trail is also apparently intersected at various points by former stagecoach line routes and other prehistoric and historic trails.”

This 1979 map by the Minnesota DNR shows evidence of an Indian Trail

This 1979 map by the Minnesota DNR shows evidence of an Indian TrailTheir study, called the Milwaukee Road Corridor Study, included maps of the region with various markings to indicate an “Indian Trail.”

Since 1986, recreation goers have enjoyed a scenic and tranquil path through picturesque towns and past scenic landscapes along the Root River Trail. For them, little thought is given to the century of railroad travel, decades of stagecoaches, and a millennia of Native travelers that used the path before them. Perhaps, years ahead, the trail will find another purpose, and those travelers will pass through without ever considering what it once was.

Sources:

William Pidgeon, Traditions of De-coo-dah and Antiquarian Researches, (New York: Horace Thayer, 1858).

James Travis Spartz, The Root River: Driftless Place Names, Published October 29, 2020, Accessed May 31, 2022, https://jtspartz.medium.com/the-root-...

Charles C. Willson, “The Successive Chiefs Named Wabasha,” in Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 12, (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1908) pp. 503–512.

History of Winona County, 1883, (Chicago: H. H. Hill and Company, 1883.)

Lafayette Houghton Bunnell, Winona (We-no-nah) and its environs on the Mississippi in ancient and Modern Days, (Winona, MN: Jones & Kroger, 1897).

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Milwaukee Road Corridor Study: Social and Physical Inventory, October, 1979, https://www.leg.mn.gov/docs/pre2003/o...

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

May 2, 2022

The Ho-Chunk: A History of Removal and Endurance

Like most groups of Native American peoples, the Ho-Chunk, commonly called the Winnebago, have a long, unfavorable history of forced removal and ethnic cleansing at the hands of the U.S. government. Originally residing on what is now Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula, the Ho-Chunk were given the name Ouinepegi by the French, a term heard as Winnebago by U.S. officials. It translates roughly to “People of the Stinky Waters” and is thought to have been given to them because of their location near scented marsh lands. Correctly termed Hochungra, or “The People with the Big Voice”, the Ho-Chunk officially took back their name in 1993.

While adapting to the fur-trade with the French and British throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries, the Ho-Chunk expanded south and west to the regions surrounding Lake Winnebago and along the Fox, Wisconsin, and Rock River systems toward the Mississippi. Eventually abandoning the Bay area they laid claim to a large portion of land in what is today southwestern Wisconsin and northwestern Illinois.

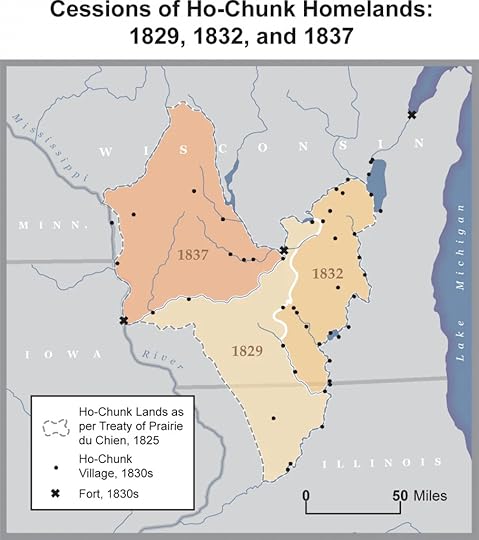

Tribal boundaries as a result of the 1825 Prairie du Chien

Tribal boundaries as a result of the 1825 Prairie du ChienIt was shortly after the War of 1812 that the U.S. government gained an interest in the region inhabited by the Ho-Chunk. The first treaty between the U.S. and Ho-Chunk was signed in 1816 to end hostilities heightened by the War of 1812. Then, in 1825, the U.S. and an assortment of Native groups, including the Ho-Chunk, negotiated the Treaty of Prairie du Chien, an agreement that established firm boundaries among those Native groups. Even though the Ho-Chunk had not ceded any territory, miners pursuing rich lead deposits quickly began moving into the region. This led to a violent incident in 1827 that became known as the Winnebago War. Following the incident, new treaty negotiations were held in 1829 in which the Ho-Chunk reluctantly agreed to sell a portion of their land.

A few years later the Ho-Chunk became embroiled in the Black Hawk War of 1832 with divided loyalties among them. With the loss of the war, the Ho-Chunk were compelled to sign a new treaty. In this treaty, the Ho-Chunk agreed to sell their land in southeastern Wisconsin in exchange for land in eastern Iowa along with annual cash payments and other provisions. Known as the Neutral Ground, the Ho-Chunk’s new territory was selected by the U.S. government as a buffer zone between the warring Dakota tribes to the north and Sauk and Meskwaki to south. Five years later, the same year the Ojibwe and Dakota signed a major land cession treaty, the Ho-Chunk ceded their remaining Wisconsin lands and those Ho-Chunk that did not agree to the 1832 treaty were removed to the Iowa Neutral Ground reservation.

Map by Cole Sutton

Map by Cole SuttonThe so-called Neutral Ground proved unlivable for the Ho-Chunk and by 1848 they were removed again. This time, the Ho-Chunk were sent north to Minnesota Territory where they were resettled at the Long Prairie Reservation. Many of the Ho-Chunk, missing their homelands, did not make the long trek north and attempted to resettle in Wisconsin. Those that made it to Long Prairie found that the reservation was densely forested and not well-suited for agriculture despite the fact that U.S. officials had been promoting farming among the tribe for years. Also, like their previous reservation, their new lands served as a buffer zone—this time between the Ojibwe to the north and Dakota to the south.

In 1853, the Ho-Chunk negotiated the Watab Treaty which was to give them new land five hundred thousand acres further south on the Crow River, near the Mississippi. However, settler-colonialists of the burgeoning settlement of Saint Anthony feared the Ho-Chunk’s new land would impede on future expansion of the white settlements. Therefore, the Watab Treaty was never ratified. Instead, in 1855, the Ho-Chunk ceded 897,900 acres of their land near Long Prairie in exchange for two hundred thousand acres along the Blue Earth River, just south of Mankato.

Map by Cole Sutton

Map by Cole SuttonThe Ho-Chunk remained on their Blue Earth reservation for several years, making improvements on the land and living peaceably with their neighboring white settlers. In 1859, seeking funds to pay off debts and buy farming equipment, the Ho-Chunk signed a treaty ceding the western half of their Blue Earth reservation. Then, in 1862, a contingent of Dakota living just west of the Ho-Chunk, launched an attack on the government agents and white settlements of south and southwestern Minnesota. Known as the U.S. – Dakota War, the Dakota were defeated and thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota in December of 1862. In the spring of the following year, all Dakota people were exiled from the state of Minnesota and resettled at Crow Creek Reservation in present day South Dakota. The Ho-Chunk, despite the fact that they lived peaceably and did not participate in the war, were also removed from the state of Minnesota by an act of Congress passed on February 21, 1863. In May of that year 1,945 Ho-Chunk boarded steamships and were sent south and west to Crow Creek. It’s been reported that “more than 550 Ho-Chunk died during their removal to South Dakota.”

Crow Creek was a barren, inhospitable land and within a few years of being removed there hundreds of Dakota and Ho-Chunk died of starvation and disease. After petitioning the U.S. government, in 1866 the Ho-Chunk were allowed to resettle in Nebraska where the Omahas willingly gave up a portion of their reservation. At the same time, many of the Ho-Chunk returned to their lands in Wisconsin. However, Wisconsin Ho-Chunk were considered “dissidents” by the U.S. government and were often rounded up and sent back to Nebraska. After seeing that the Ho-Chunk were determined to live upon their ancestral homelands, in 1874 the U.S. government extended the 1862 Homestead Act to Ho-Chunk peoples allowing individuals and families to claim up to 80 acres in their homeland.

The Wisconsin Ho-Chunk gained federal recognition in 1963 and today, according to Wisconsin First Nations, “the Ho-Chunk Nation is not located on a reservation or a single continuous land base in Wisconsin, but rather, the Ho-Chunk Nation owns land in fourteen counties in Wisconsin, including Adams, Clark, Crawford, Dane, Eau Claire, Jackson, Juneau, La Crosse, Marathon, Monroe, Sauk, Shawano, Vernon and Wood Counties and also land in the State of Illinois.” Those that stayed in Nebraska are still there today and are called the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska. It’s clear now that from 1816 to 1874, the U.S. government perpetrated a continuous effort to remove and ethnically cleanse the Ho-Chunk people. But the Ho-Chunk endured each effort, recovered some of their homelands, and today is one of Wisconsin’s leading employers.

Sources:

Matt Reicher, “Ho-Chunk and Blue Earth, 1855–1863,” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/ho-chun... (accessed May 1, 2022).

Reicher, Matt. “Ho-Chunk and Long Prairie, 1846–1855.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/event/ho-chun... (accessed May 1, 2022).

Will and John Gorenfield, “The Ho-Chunks Were Forced West, and Misery and Violence Followed,” Historynet, Published February 28, 2017, Accessed May 1, 2022, https://www.historynet.com/ho-chunks-...

“Ho-Chunk and Winnebago Explained,” Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volumes III, IV, X, XIII, and XIV, https://www.csmpl.org/files/local/war...

“Ho-Chunk Treaties and Treaty Rights,” Milwaukee Public Museum, Accessed May 1, 2022, https://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-105

“Ho-Chunk Nation: Hochungra – The People With The Big Voice,” Wisconsin First Nations: American Indian Studies in Wisconsin, Accessed May 1, 2022, https://wisconsinfirstnations.org/ho-...

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

March 31, 2022

Drifting Goose and his peaceful perseverance against white settlement

Drifting Goose, photo by Charles Milton Bell. Photo courtesy of The Center for Western Studies, Augustana University.

Drifting Goose, photo by Charles Milton Bell. Photo courtesy of The Center for Western Studies, Augustana University.Magabobdu, or Drifting Goose, was a Hunkpati Sioux chief who never signed a treaty with the U.S. government and is known for his resistance of white settlement and railroad development upon his peoples’ land. Born in 1821 near present-day Redfield, South Dakota, Drifting Goose and his band of Hunkpati Sioux lived a semi-nomadic life in and around the James River Valley. At just the age of nineteen, Drifting Goose became the chief of his people. It was at that time, in 1840, when his band of approximately three hundred members established a permanent camp in abandoned earth lodges on an island, now called Armadale Island, in the James River. While there, they were known to live a prosperous life in which they cultivated corn, gathered berries and wild turnips, raised stock, and hunted the scattered groups of bison that roamed the western plains.

Life for Drifting Goose and his band began to change in 1851 when the Sisseton and Wahpeton signed the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. The treaty, which opened up twenty-four million acres of land to white settlement, included lands stretching as far west as the James River. Settler-colonists quickly poured into the region. Rather than resort to violence, the Hunkpati Sioux implemented intimidation tactics as a way of “unwelcoming” settlers. These tactics included pulling up survey sticks, taking or damaging equipment, and running off livestock. The strategy was quite successful at warding off encroaching settlers and developers until 1856 when a detachment of U.S. soldiers arrived to secure a townsite of white settler-colonists. But, even with the troop presence, Drifting Goose effectively kept settler-colonists out of the James River Basin.

The next setback came following the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. In August of that year the Dakota Sioux, in retaliation for years of mistreatment, attacked the white settlements and government agencies in southwestern Minnesota. The Dakota won several victories, but after a series of battles they were defeated and their people were exiled to a reservation at Crow Creek, South Dakota. In the aftermath of the war there was a severe mistrust among the white population of all Native peoples in the area. There was also a $25 bounty put on all Dakota found within Minnesota. As a result, many Dakota fled west to the James River region. Additionally, the white settlers at Sioux Falls moved west to Yankton at the confluence of the Missouri and James Rivers, further encroaching on the homeland of Drifting Goose and the Hunkpati Sioux.

A few years later, in 1868, leaders from the Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The treaty established The Great Sioux Reservation west of the Missouri River in present day South Dakota. But, like the treaties before it, Drifting Goose did not sign the treaty or agree to its terms. Nevertheless, in the years following the treaty settlement increased in the James River region while more surveyors also made their way into the territory. Like he had before, Drifting Goose and his band repelled the settlers and surveyors through nonviolent means while continuing to live a prosperous, mostly agricultural life.

Then, in 1878, Drifting Goose was ordered to leave the James River region and resettle at the Crow Creek Reservation. Drifting Goose reluctantly agreed. But, because of peaceful perseverance, Drifting Goose had earned the support of many influential whites such as the Reverend Henry B. Whipple and General Henry Hastings Sibley. In fact, shortly after Drifting Goose was resettled at Crow Creek, Sibley wrote a letter to the authorities in Washington D.C. arguing that Drifting Goose and his people should be “protected in possession” of their lands. As a result, in 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes signed an executive order establishing the Drifting Goose Reservation.

Unfortunately, by 1879, settlement in the James River Valley had increased to such a degree that conflict and disagreements were inevitable. Upon moving back to their homelands, Drifting Goose’s band demanded that all whites who had settled upon the reserved lands should be expelled. According to historian George W. Kingsbury, “They entered the houses of settlers when the men were not at home, and insulted and hustled the women, forcing the women to cook for them. They boldly entered the cornfields, husked the corn and carried it away in sacks. They informed the settlers that the country was theirs and all the whites would be compelled to leave; that the agent from Sisseton was coming over and would put them in possession.” Because of this, just a year after the establishment of the reservation, Drifting Goose and his people were ordered back to Crow Creek.

Though Drifting Goose never returned to live upon his homeland, he continued to fight for the rights and advancement of his Nation. One of his most lasting legacies was the establishment of a school on the Crow Creek reservation. Also, in 1888, he and a large group of Sioux leaders traveled to Washington D.C. in response to the Dawes Allotment Act. Drifting Goose died in 1909 and was buried on the Crow Creek reservation. Today, a road at Fort Thompson is named after the great leader who is known as one of the last bastions of Native resistance to white settlement.

Sources:

Mike McAfferty, “Chief Drifting Goose,” Aberdeen Magazine, (January/February 2018), https://aberdeenmag.com/2018/01/chief-drifting-goose/

George W. Kingsbury, History of Dakota Territory, Vol. 2, (Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1915)

“Drifting Goose: Hunkpati Dakota,” Akta Lakota Museum & Cultural Center, http://aktalakota.stjo.org/site/News2?page=NewsArticle&id=8679

Submit a form.

About the Author

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

March 8, 2022

There’s still time to join my Summer Speaking Tour

This summer, author, historian, and publisher Colin Mustful is available to speak at libraries, museums, book clubs, bookstores, and various other organizations across the state. As the author of four historical novels about Minnesota’s complicated history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement, Mustful is eager to engage with audiences about what he’s learned while he continues to confront, study, and convey history. Additionally, Mustful is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press publishing historical fiction novels and stories. He’s looking forward to sharing his publishing journey with readers and writers alike, while providing lessons on writing and publishing.

If you’d like to invite Mustful to speak at your club or organization, you can do so use using the following calendar link: https://calendly.com/colinmustful While Mustful is open to developing a unique presentation or workshop that best fits the needs of your patrons, he has developed is a list of pre-conceived presentations which are listed below.

Please note that all presentation fees are negotiable and may vary based on your organization’s distance from his home in Roseville.

If you’d like to attend one of Mustful’s presentations, please see the list of currently scheduled programs at his events page.

Suggested PresentationsHistorical Presentation:

Resisting Removal: The Sandy Lake Tragedy and the Years that Followed

This presentation will catalog the events surrounding the Lake Superior Ojibwe in the years 1850 to 1855. Specifically, it will focus on the illegal removal efforts of Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey and Indian Agent John Watrous who attempted the forced removal of the Lake Superior Ojibwe which resulted in the death of 400 Ojibwe at Sandy Lake, Minnesota. The presentation begins by considering important elements of cultural and historical interpretation, then provides a cultural and political context of the 1850 Removal Order, then details the continued removal efforts after the Sandy Lake Tragedy and the perseverance of the Lake Superior Ojibwe to resist those efforts and earn a new treaty that promised permanent reservation homes in their homeland.

Historical Presentation:

The U.S. – Dakota War of 1862: A Historical Context

The U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 was a watershed event with a major, long-lasting impact. But what was the U.S. – Dakota War and how and why did it happen? In this presentation, I trace the history of the U.S. – Dakota War beginning in 1805 when the Dakota signed the Pike Treaty at Bdote. Throughout the presentation, I identify the multiple perspectives and factors that, over time, contributed to the Mankato hanging and the expulsion of the Dakota and Ho-Chunk peoples from Minnesota to Crow Creek, South Dakota. Before completing the presentation, I will read an excerpt or two from my novels about the U.S. – Dakota War.

Historical Presentation (

View a recording of this presentation

)

A Welcome Tragedy: Factors that Led to the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862

On December 26, 1862, the United States Government hanged thirty-eight Dakota people in Mankato, Minnesota, for their participation in what is known as the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862. This remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history. But the hangings and the depredations that preceded them were not the result of an isolated incident or event. The war did not occur by chance. Rather, it was the foreseeable result of years of misconduct, fraud, and exploitation. Recommendations were made and warnings were given, but nothing was done. In this presentation, I will reveal the faults within the Indian System that fostered neglect, nourished corruption, and welcomed tragedy.

Fiction Craft Presentation:

Authorial Intrusion and the Civil War Novel: How to Write History Through Fiction

Historical fiction is one of the most popular literary genres. When done well it brings history to life, teaching readers about important historical people and events while also evoking profound, relatable emotions through its characters. But how does the historical author balance history and fiction? In this presentation, I carefully examine four Civil War narratives and identify how each author incorporates important historical details into their novels without disrupting the fictional dream. Throughout the presentation I identify the specific elements that make a historical novel effective and engaging, showing readers and writers alike how to write history through fiction. At the end, I will guide patrons through the process of turning a historical document into a fictional scene.

Publishing Industry Presentation:

Beyond Craft: An Explanation of the Publishing Process

As an independent author and publisher I have a wealth of experience and knowledge to share with readers of all levels. Beginning as an independent author, I was naive to the challenges and pitfalls of the publishing process. After years of experience and education, I learned about what it means to be an author and how and why to publish a novel. In this presentation, I will talk with writers about the process of making the idea of a story into a completed manuscript, and then making that manuscript into a published novel. I will tell writers about important steps in the writing and publishing process such as finding Beta Readers and developing an online presence. I will give them tips on how to get their manuscripts noticed by publishers and I will tell them how and why I choose whether or not to publish a manuscript that has been submitted to my press. I will end the presentation with a Q&A session to ensure I have not missed any important questions about the writing and publishing process.

Submit a form.February 21, 2022

George Bonga Died in 1874 – The Trouble with Copy/Paste in the Age of the Internet

George Bonga circa 1870. From the Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society

George Bonga circa 1870. From the Collections of the Minnesota Historical SocietyWhen I set out to write this blog post, I intended on sharing a brief biography of the Afro-Indigenous fur trader George Bonga. Born around the year 1802 to a black father, Pierre Bonga, and an Ojibwe mother, Ogibwayquay, George became a fur trader in northern Minnesota successfully navigating between white and Indian worlds. He was known to be a large and powerful man who was also well educated. Also, he is well-known for working as a guide and interpreter on Lewis Cass’ 1820 expedition to locate the source of the Mississippi River, for tracking and capturing an accused murderer in 1837 in what became Minnesota’s first criminal trial, and for, along with his wife, opening and maintaining a lodge at Leech Lake. He was a remarkable man deserving of the attention he’s recently received by historians and bloggers.

But, while researching George Bonga, it didn’t take long for me to notice that the date of his death is disputed, or at the very least, unclear. Some sources report that he died in 1874, others 1880, and still others 1884. It wasn’t just that the sources differed, but that they reported the date of his death without any ambivalence. (With one exception; The St. Paul History Theater stated, “Sources differ as to the year Bonga died, with some stating 1874, 1880, or 1884.”) In some cases, sources have differing death dates listed on the same document or webpage without even acknowledging their discrepancy. This made me curious. When did George Bonga die? And why do the sources differ?

I started by doing an internet search for the following terms: “George Bonga 1874”, “George Bonga 1880”, and “George Bonga 1884”. Below I’ve listed a handful of results for each search term along with any corresponding information related to Bonga’s death found within the source. You’ll notice that many sources also tried to determine his age at the time of his “reported” death. Direct quotes are italicized.

Google Search “George Bonga 1874”

https://www.mnopedia.org/person/bonga-george-ca-1802-1874

Bonga died at Leech Lake in 1874.https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/82501366/george-bonga

Reports death as November 30, 1874 (aged 72)Also reports death as 1880 (age 78)Guests would recount his yarn spinning and after-dinner singing until he died near Leech Lake in 1880 at 78.https://www.geni.com/people/George-Bonga/6000000041048627515

Death: 1874 (66-75)https://www.ancestry.co.uk/genealogy/records/george-bonggaa-bonga-24-37w0zcb

He passed away on 30 Nov 1874 in Leech Lake, Cass, Minnesota, United States.Reports date of birth as 1803. George passed away in 1874, at age 71 at death place, Minnesota.George passed away circa 1884, at age 82Google Search “George Bonga 1880”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Bonga

Bonga died there when he was around seventy years old. (Interestingly, while reporting his death in 1880, which would have made him 77 or 78 years old, the author cites the MNopedia article which reports his death as 1874.)https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/bonga-george-1802-1880/

https://peoplepill.com/people/george-bonga

Reports death as January 1, 1880George Bonga died in 1880.Bonga died there when he was around seventy years old.https://wcif.org/blog/community/black-history-month/

https://aaregistry.org/story/george-bonga-an-early-settler-in-minnesota/

George Bonga died in 1880.Google Search “George Bonga 1884”

When Bonga died in 1884, notice of his death appeared in newspapers in Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York.https://edu.glogster.com/glog/george-bonga/1x4j28ji11q

An extraordinary man George Bonga lived until 1884 a very old age at the time of his passing.Bonga died in 1884. Notice of his death appeared in newspapers in Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York.https://theweeklychallenger.com/george-bonga-african-american-fur-trader/

Bonga died in 1884. Notice of his death appeared in newspapers in Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York.In 1884, Bonga died. His death was mentioned in newspapers across the country and noted by the U.S. Congress.https://kentakepage.com/george-bonga-african-american-fur-trader/

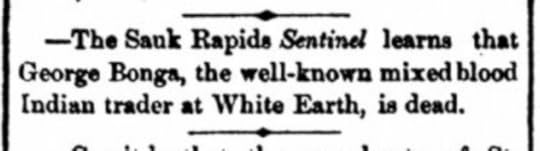

Bonga died in 1884. Notice of his death appeared in newspapers in Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York.While much is still unclear, I’ve been able to draw a few conclusions. First and foremost, George Bonga most likely died in 1874. While this still needs to be corroborated, I was able to find a report in The St. Cloud Journal, December 10, 1874, stating that, “The Sauk Rapids Sentinel learns that George Bonga, the well-known mixed blood Indian trader at White Earth, is dead.” Below is a screenshot of that report. The website Find a Grave reports the exact date of his death as November 30, 1874. I reached out to the author of the Find a Grave post asking for the source of the November 30th date. Unfortunately, in her reply she stated, “I can’t recall where I got the exact date of death.”

It appears to me that the reported death date of 1884 stems from an article published in the Minnesota Conservation Volunteer Magazine in 2010, which is a periodical produced by the Minnesota DNR. Toward the end of the article the author states, “When Bonga died in 1884, notice of his death appeared in newspapers in Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York.” The exact same language appears in multiple sources that were published after 2010. When I reached out to the author of the DNR article to inquire about his sources, the author replied, “Though I referenced that quote regarding Bonga’s death, I didn’t confirm the original source. Had I been doing academic work I would have.” It’s my guess that whatever his original source was, that source mistakenly reported Stephen Bonga’s date of death, which occurred in 1884, in place of George’s date of death.

I’m uncertain of the original source reporting George Bonga’s death in 1880. However, it’s likely that, since Wikipedia is such a widely used source, many subsequent sources relied on the date reported by Wikipedia. It’s possible that the same mistake that might have happened between George and his brother Stephen also happened between George and his sister Margaret who died February 6, 1880.

Regardless of when George Bonga actually died, this provides an excellent case study regarding problems that can arise while reading and writing about history. If an author, at any point, makes a mistake, that mistake has the potential to be multiplied until it becomes recognized as fact. Furthermore, this also shows a lack of care shown by many online authors. In several instances, the authors used conflicting sources but didn’t recognize the discrepancies within their own article. I’m not writing this to cast aspersions on any of these authors. In today’s digital age where content is king, writers are under a lot of pressure to add new content all the time. This can make it challenging to balance the urgency of adding more content with the necessity of verifying and corroborating your information. And, admittedly, I am guilty of many of the same mistakes.

Let this be a lesson then. First, remember to always cite your sources so that readers and researchers can trace the information back to its original source. Second, take the time to verify important information. This may not mean tracking everything back to its original source, but at least verifying your information with more than one source while also thinking critically about that information so that you’ll recognize when there is a potential mistake. And finally, readers, don’t commit to any one source as true and reliable information. Accept the information you read, but, like the writer doing their research, seek out multiple sources while also thinking carefully and critically about the information you’re taking in.

Sources:

Eric Weber, “Bonga, George (ca. 1802–1874).” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. http://www.mnopedia.org/person/bonga-george-ca-1802-1874 (accessed February 18, 2022).

“George Bonga,” Wikipedia, accessed February 17, 2022, last updated January 14, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Bonga

William Durbin, “Who Was George Bonga?” Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, (November-December 2010), Pp. 41 – 50, https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/mcvmagazine/young_naturalists/young-naturalists-article/george_bonga/george_bonga.pdf

Colin Mustful is an independent author, historian, and publisher. His work helps readers learn and understand the complicated and tragic history of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in the Upper Midwest. He has a Master or Arts degree in history and a Master of Fine Arts degree in creative writing. He is also the founder of History Through Fiction, an independent press that publishes high-quality fiction that is rooted in historical research. Mustful is an avid runner and soccer player who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He believes that learning history is vital to understanding our world today and finding just, long-lasting solutions for the future.

Submit a form.