Scott H. Young's Blog, page 22

November 23, 2021

Learning by Doing: When Does it Work? When Does it Fail?

How much do we learn simply by doing the things we’re trying to get good at? This question is at the heart of a personal research project I’ve been working on for several months. Readers can note some previous entries I’ve already written on this project.

My original intuition was that we get good at what we practice, and skills are often quite specific. This suggests doing the real thing—focusing precisely on what we want to get good at—is underrated.

I still think this view holds. But this simple statement belies a lot of complexity. There’s a lot of fascinating research showing which conditions lead us to get better through direct practice. These, in turn, have shaped my views about the best way to get good at complex skills.

Here are some of the research findings I’ve uncovered.

1. Complexity and Cognitive LoadOne of the major mediators of the “learning by doing” thesis is task complexity. Absent instruction, we need to rely on what cognitive scientists refer to as “weak methods” to solve problems. These include trial-and-error and means-end analysis. There’s research showing that, at least in some cases, an overreliance on this kind of “figuring things out” can make it harder to learn.1

The obvious problem with this is that if something is too hard, you simply can’t do it. If you can’t do it, then “practicing it” is meaningless. This problem can arise in some educational approaches. When students are given overly complex problems, they may default to “weak methods” to solve them and fail to actually practice the knowledge and skills they’re supposed to learn.

However, there’s also a more subtle problem. Even if you can figure out the problem, the working memory required for solving it may be so great that you don’t encode the procedure well.

This is the conclusion behind John Sweller’s research on cognitive load theory. Experiments show that seeing lots of examples tends to beat problem solving in a head-to-head comparison for algebra problems.2 However, the result flips once you figure out the pattern, and problem solving becomes more useful.3

My views on this issue seem to correspond most closely to Jeroen J. G. Van Merriënboer and Paul Kirschner. Their instructional design guide, Ten Steps to Complex Learning, argues for the importance of starting with real tasks to be learned. But, they also stress the importance of having lots of support and structure in the early phases of learning to avoid the problems Sweller’s research highlights.

2. Prerequisite Skills and ConceptsA related issue is how much weight should be given to learning the fundamentals versus doing the whole task? This, it turns out, is a contentious issue in the research. Some argue that presenting the entire task from the outset is necessary to integrate skills and knowledge properly. Others argue that it’s essential to start from the basics first.

A representative of the former view would be Allan Collins and John Seely Brown’s cognitive apprenticeship. The idea here is to present students with the real situations and give enough assistance and structure so that the cognitive load isn’t overwhelming.

An alternative approach, Direct Instruction, was developed by Sigfried Engelmann and Wesley Becker. In this theory, skills are built from the bottom-up, with careful attention paid to the full range of component skills to minimize later issues with transfer to the whole task. Direct Instruction performs well in educational settings, despite being unpopular for its perceived “assembly line” approach to teaching.

It seems clear that both the structured whole and part-to-whole approaches can be successful. But the details matter quite a bit. Presenting information in a full context, even with appropriate scaffolding, may make it harder to focus attention on what is to be learned. This seems to be the critique of problem-based learning in medicine, where students are taught all their medical knowledge in the context of patient cases. It might be harder to learn how the body works, if it’s always presented within the context of individual patients.

However, the research on part-to-whole learning is not uniformly positive.4 Many skills must change when they are integrated with other tasks. When component skills are separated in time, practicing each skill by itself can work well (e.g., parallel parking while learning to drive a car). However, when skills need to be performed at the same time (e.g., learning to shift gears while also steering the car), practicing each skill alone is often less effective than simply practicing the whole task.

What’s the right approach? I think it depends. If you were trying to learn quantum mechanics and didn’t know algebra, you’d be in for a hard time trying to start there. But many educational programs pretend there are prerequisites that don’t actually exist in practice—learning to speak Chinese, for instance, doesn’t actually require learning to handwrite, and teaching it that way may throw up unnecessary barriers for someone who only wants to speak.

3. Deliberate Practice and PlateausAnders Ericsson’s work on deliberate practice makes a distinction between performing a skill and practicing it. His research found that elite performers spent more time engaged in the careful act of improvement, rather than merely using the skill a lot.

Examples of this include the link between achievement and the quantity of deliberate practice in violin players, chess players benefiting more from increases in “serious study” than in extra tournament play, and the decline in skill medical practitioners experience the longer they have been away from school.56

Some research challenges the deliberate practice concept and its relevance to professional skills.7 But, for the moment, let’s assume that Ericsson’s observation about the nature of improvement is correct. What does that say about my original idea that we get good by doing the real thing?

In some ways, there’s no contradiction, only a matter of scope. You get good at what you do. If you play basketball, you’ll get better at basketball. If you practice shooting layups, you’ll get better at shooting layups. If you can practice a few hundred layups in an hour doing drills, and only a handful of times during a game, you’ll get better faster doing drills. The drilled layups may be harder to integrate than the layups played during the game. Still, the rate of practice is much higher in the drills, so the efficiency may be worth the trade-off.

A secondary factor seems to be the incentive structure created by the environment. When we enter a new environment, our performance often quickly reaches adequacy and then levels off. Once our performance is “good enough,” we stop actively seeking ways to improve it.

One route to improvement would be to disengage from the performance requirements of the job and focus exclusively on practice. But it depends on accurately identifying critical skills and creating conditions for practice. This is hard to do for nebulous skills, and, I’d argue, a lot of what we’re trying to get good at is in ill-defined domains of performance.

Another strategy is to change your environment so that there are increased pressures for quality. As a writer, I found writing a book with a traditional publisher (and fixing a specific goal for the kind of book I wanted to write) did more for me than writing “drills.” Since pursuing real challenges also has benefits beyond simply getting better at the skill itself, I tend to favor it over isolated practice. However, there are probably cases where isolated practice is necessary.

4. Background KnowledgeKnowledge tends to be more skill-like than we may assume. Research on transfer-appropriate processing, for instance, shows that we encode the same information differently, depending on how we think we’re going to use it. Work on the testing effect and retrieval practice shows that practicing remembering strengthens memory more than repeatedly looking at the content.

However, there’s a lot to be learned from reading and listening. As a scientist, you would be at a significant handicap if you only performed experiments and never read the surrounding literature! Similarly, understanding the background knowledge that underpins a domain is enormously helpful.

The question that interests me is: how much background knowledge should you obtain before practicing? Our experience of school suggests the answer is a lot. In school, you spend years studying before you “do” anything that actually resembles the real thing.

I think this is more an artifact of our educational system than an ideal path to mastery. Schools serve two goals, teaching useful background knowledge and skills, and sorting students by ability. This sorting function may be the more influential force in how our educational institutions actually work.

To see why, consider two hypothetical training activities: one with high fidelity to the real activity, but low ability to grade and sort students; and another that’s contrived and unrealistic, but is easy to rank. If the goal was training, you’d want more of the first type. If the goal was sorting, you’d want more of the latter. Given that many of our educational institutions lean so heavily on the latter, that’s a good indicator of where priorities lie.

5. How Common Are Tasks With Greater Than 100% Transfer?Transfer of learning is the idea that if you learn task A and then learn task B, how much faster will you learn task B because you already know A? Zero transfer means that time spent on the first task offered no help for the second. One-hundred percent transfer means practicing A was just as good as practicing B. Greater than 100% means that, to get good at B, you shouldn’t do B! You should practice A instead since it will be more efficient.

The research on transfer shows that most tasks are between 0 and 100%. In other words, learning A can occasionally help with learning B, but it’s usually worse than doing B directly. In cases where A and B differ considerably, the transfer tends to be even lower than most people think.

In some cases, the transfer is much less than you’d naively expect. Learning to do algebra problems of one type, for instance, transfers surprisingly poorly to learning ones of a slightly different kind.8

However, tasks with greater than one-hundred percent transfer do exist. For example, doing a simplified version of a task can result in better learning than the most complex version due to cognitive load. Thus learning is better when it “ramps up” rather than diving right into the most challenging scenario to start.

But what about less obvious cases? One that has been proposed to me comes from language learning. Beyond a certain point, the argument goes, reading and listening in a language are better practice activities for speaking ability than speaking. If this is true, then this would be a prominent counter-example of my bigger idea.

Supposing this statement is correct, what might explain it? One possible answer relies on background knowledge and cognitive load. Reading in a language exposes you to a greater variety of vocabulary than you might acquire in conversation. Reading also reduces cognitive load—you can stop to look up words—so that it is easier to learn underlying patterns.

How general is this phenomenon of greater-than-100% transfer? I suspect most cases fall under issues of task complexity and exposure to background knowledge. However, even in the case of language learning, it’s certainly possible to be a fluent reader or listener and be unable to speak. So even when doing something else may benefit skill acquisition more than direct practice, the amount of direct practice should probably never go to zero.

6. Are Some Skills Not Learnable?A final wrinkle in my overall picture is that some skills may not be learnable through practice at all. James Voss and Timothy Post have found that experts outperform novices in certain categories of prediction tasks but grossly underperform simple linear regression models.9

The assumption that we get good at what we practice presumes improvement is possible. But it’s probably the case that many skills simply aren’t improvable. The cue-response relationship is too complicated and there aren’t any training methods that properly break them down into a sequence of learnable steps.

Some skills are difficult or impossible for humans to learn, but mathematical models can do them. In these cases, the key skill is learning to use the mathematical model. As machine learning advances and more data become available, I suspect we will develop more of these machine-human hybrid skills.

In many ways, this finding isn’t entirely surprising. I don’t know how to calculate cube roots with just a pencil and paper, but I can use a calculator to do it immediately.

Much of skill learning also involves figuring out which tools that can improve your performance. For millennia, technology has augmented our physical skills. More recently it has replaced the “lower” cognitive skills of memory and algorithmic calculation in many instances. However, we might be entering an age where “higher” skills such as judgement, taste and decision-making may be relegated to machines or computer-human hybrids.

What are the Practical Implications for Self-Improvement?My general advice remains: do the thing you’re trying to get good at. But there are useful considerations to keep in mind:

Instruction plus practice beats practice alone.If the task is too difficult, seek lots of examples and find simpler versions of the task to start.Broad background reading and study are helpful. But they can’t replace doing the real thing.Isolated practice of component skills can be effective. But these skills are often subtly different when doing the real thing. Thus, a good habit is alternating between whole and part practice.Cases where transfer exceeds 100% can exist. Usually, they’re because the alternative training task exposes you to information you can’t discover through practice, or because it reduces cognitive load enough that it aids in knowledge acquisition. But, as with the previous point, alternating between these activities and the real thing is probably helpful to avoid integration problems later.Some skills may not be learnable through practice. In these cases, relying on tools that remove the need for direct improvement may beat extensive experience.As I continue researching this topic, I’ll do my best to share what I find with you!

The post Learning by Doing: When Does it Work? When Does it Fail? appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 16, 2021

What if You Don’t Feel Smart Enough?

I often don’t feel smart enough to do what I do.

I don’t say this out of false modesty or as an attempt to be more relatable. I spent the last decade taking on rather-immodest learning challenges. I’ve always been confident in my ability to learn new things.

Instead, the insecurity comes from recognizing that, no matter how hard I try, there are tons of people who know way more than me. Perhaps they, not I, should be the ones to write these essays?

I was reminded of this recently while reading Scott Alexander’s newsletter. He writes:

I often find myself trying to justify my existence; how can I write about science when I’m not a professional scientist, or philosophy when I’m not a professional philosopher, or politics when I’m not a professional policy wonk? When I’m in a good mood, I like to think it’s because I have something helpful to say about these topics. But when I’m in a bad mood, I think the best apology I can give for myself is that the discovery drive is part of what it is to be human, and I’m handling it more gracefully than some.

Alexander is extremely smart. He’s written some of my favorite essays. He’s able to quickly summarize deep research, reveal hidden patterns in our debates, and manages to be funny at the same time. As a writer, I’m envious.

Why should Alexander feel the need to apologize for his efforts to assemble new ideas? Why should you or I not feel smart enough to do the work we want to do, and what should we do about it?

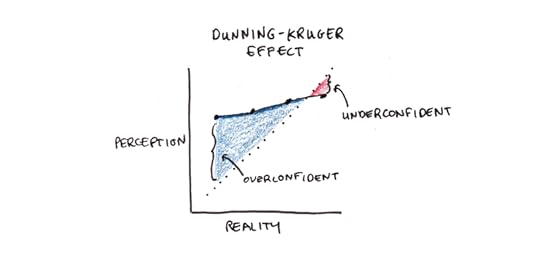

Dunning-Kruger Effect?The popular explanation of this is the Dunning-Kruger effect. Those who are incompetent also cannot accurately self-assess their competence. As David Dunning explains:

“If you’re incompetent, you can’t know you’re incompetent … The skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is.”

Bertrand Russell expressed a similar sentiment nearly a century ago: “The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.”

So that’s the problem? Smart people are insecure about their knowledge, and the ignorant are oblivious to their incompetence?

Except that’s not what the research actually shows. The study found that incompetent students overestimated their class rank, and top students underestimated theirs. However, incompetent students didn’t think they were better than good students.

[T]he bias is definitively not that incompetent people think they’re better than competent people. Rather, it’s that incompetent people think they’re much better than they actually are. But they typically still don’t think they’re quite as good as people who, you know, actually are good.

Did all those people who casually cited the Dunning-Kruger effect to mean “stupid people are cocksure” just fall victim to Dunning-Kruger? Or is something else going on here?

Digging Into KnowledgeMy own experience with learning things tends to involve the following cycle:

Read claim X.Read a bit more about claim X. It turns out the authors who proposed X didn’t actually say X, but X’. Also, some people think Y and Z with good reason. Nobody thinks Q.Actually, some people think Q. And X’ is contradicted by work done in a different field, except there it’s called P. Maybe X is right all along?The expectation is that as you learn more and more, you’ll eventually hit a bedrock of irrefutable scientific fact. Except usually, the bottom of one’s investigation is muck. Some parts of the original idea get sharpened, others blur as more complications and nuance are introduced.

This experience doesn’t just apply to researching facts. When I started learning languages, I was more than happy to carry on a decent conversation. But, once I achieved it, I became self-conscious of all the things I couldn’t do well. I’d struggle to follow movies or read literature. Group conversations could be surprisingly challenging. Occasionally I’d bump into a seemingly basic situation that I couldn’t grasp. I’d think: “Wait… Am I actually terrible at this?”

Given my modest talents, it’s impossible to assert that this pattern continues forever. Perhaps there truly is a vaunted place of excellence on the other side, where doubts cease to exist and one is supremely self-confident. If such a place exists, I certainly haven’t found it.

Instead, I suspect that this squirming feeling of self-doubt is a persistent feature of learning. Speculating further, I’d suggest it arises from at least two principle causes: one inherent in the cognitive structure of knowledge and skills, and the other in the social comparison with expert performers.

Knowledge Structures and Social ComparisonsThe first cause of this trouble seems to be in how knowledge works. Ability appears to result from accumulating increasingly nuanced patterns of discrimination, motor skill, and reasoning.

Consider learning to speak English. You first learn the word “good,” which applies to a whole range of situations. Later you learn shades of intensity: “okay,” “fine,” and “excellent.” As you gain more knowledge, you learn “stupendous,” “sublime,” and “stellar.”

Each word occupies a slightly different meaning. A space of discrimination previously described by “good” now gets subdivided into many overlapping sections. Blanks exist at each stage of the learning process—areas where you don’t have a good word to describe the situation. As you get more precise, the size of blanks appears to grow. Gaps that seemed negligible begin to look like chasms.

From a relative perspective, there is consistent progress. You always know more than you knew before. But it often doesn’t feel that way. Instead, learning more seems to make you feel more ignorant about everything else you don’t know.

The other effect of increasing knowledge is changing who you compare yourself to. When I started writing, I mostly read other advice writers and compared my work to theirs. Now that I spend most of my days reading original research, I’m comparing the quality of my thinking to a more rarefied intellectual strata. That comparison is not always favorable.

Dealing with Intellectual InsecurityThere seem to be two strategies for dealing with this kind of intellectual insecurity.

The first is to “leave it to the experts.” The relatively smart often apply this one to the relatively uninformed as a kind of browbeating. In other cases, it’s intended to try to remove noise from a discussion so those with the most experience can speak the loudest.

While I understand wanting to let the most-informed speak clearest, I have serious doubts about the consequences if this strategy were to be applied consistently.

Fields of expertise often develop insular intellectual cultures where questionable assumptions can get entrenched. While a failure to heed expertise is blamed for many of our current woes, an overconfidence in expertise may have produced some of the woes of the past. It’s not obvious, to me at least, that our overall credence in authorities is set too high or too low.

I am persuaded by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber’s account of reasoning. They argue that the best answers arrive not from individual rationality, but from open, deliberative processes. Reason, in this sense, functions more like a conversation than a solitary mental act. While individual voices may be wrong, the collective takeaway from the discussion is fairly good.

Still, there’s an obvious, opposite danger of intellectual egalitarianism: considering everybody’s opinions as equal, even if some people have spent years in careful study and others have not.

The second strategy, which I prefer, is to try to be honest yet humble. Do your best, given what you know. Be willing to change your mind. If many people who know more than you disagree, it’s a sign to stop and listen.

Perhaps it is a tad self-serving in light of my career as a writer of non-expert opinions, but my gut tells me that the right way to use one’s insecurity is as a drive to improve, not to halt inquiry. Be honest and do the best work you can, but don’t ever stop learning.

The post What if You Don’t Feel Smart Enough? appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 9, 2021

The Craft is the End

I once met with a successful academic and author. He told me that he didn’t understand most of his peers.

Getting tenure at a university is a lot of work. You need to produce a lot of the right kind of intellectual output to get recognized. But after that, you have total freedom to pursue whatever work you think is true and important.

He commented that many of his colleagues waste this opportunity. They continue to churn out the same boring, citation-grubbing papers that made their early career. They have academic freedom and the job security to take intellectual risks, but instead, they play it safe.

What he strives for, in contrast, is to use his freedom to do the work he thinks is vital. Whether this meets the intellectual fads of his field doesn’t matter.

Was he right about the other academics? Who knows. I’m too far removed to judge. Maybe those people he criticized were doing work they thought was essential, even if my acquaintance disagrees.

What struck me about this conversation was that it flipped on its head a common assumption about success. For many, the goal of success is to be rich and respected. That’s why you work hard. For this person, the goal is to do the work he thinks is important. Doing the work is the end.

C.S. Lewis and the “Inner Ring”I thought about this conversation after I stumbled upon the text of C. S. Lewis’s famous lecture, “The Inner Ring.”

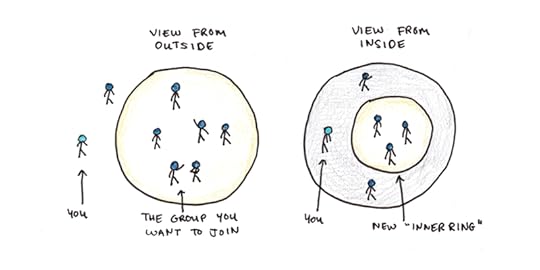

In the lecture, Lewis warns his audience against the drive to be within the inner ring—that select group of people that seem cool, successful or famous. It’s a fundamental impulse of human beings to want to be included, to feel like they’ve “made it.”

Yet, Lewis noted that within every inner ring is a ring yet more inner. Suppose you get a master’s degree because you feel like people don’t take you seriously because you don’t have credentials. But you still are looked down upon by people who have a Ph.D. So you get your doctorate. But then you find out that the Ph.D. isn’t what matters but where you went to school, and whether you got tenure, and so on.

The problem isn’t that inner rings exist. Lewis correctly notes they’re essential for society’s function. What’s dangerous is the desire to always burrow deeper inside them. There is no final, inner ring where one can have refuge. Like the layers of an onion, you peel them away until there is nothing left.

Craft as the Antidote to Status SeekingWhat is the solution? How does one avoid becoming, in Lewis’s words, an “inner ringer”?

Lewis argues that the answer is craft. If you care about your work—for its own sake—you can transcend the petty status-seeking that surrounds you.

Occasionally, I’ve seen the mantra of excellence become a kind of sour grapes. Others don’t respect your work, perhaps with good reason, so instead of considering this criticism, you claim you’re doing it just for yourself. Adhering to an internal standard, you reject the judgement of others.

But this isn’t quite right. The only way to counter a strong, instinctual urge like status-seeking is to override it with a more compelling one. Having soft and idiosyncratic standards for your work doesn’t insulate you from the desire to be liked—it’s just a form of self-deception.

Instead, those who manage to get wholly absorbed in their craft do so because they have higher standards for their work than anyone else expects. Acclaim and fame fail to motivate because that’s too easy, not too hard. Improvement according to an internal sense of quality matters more than whether some inner ring agrees.

This pursuit of craft can be stressful. It can become a kind of caustic perfectionism, where none of your work (successful or not) meets the aspirations you have for it. It’s certainly not a wholly positive force. Still, going deep within your work is a surer route to satisfaction than peeling the onion of social hierarchy.

You may never be conventionally successful. You may never get the respect you feel you’re due or the rewards you deserve. But if you can focus on doing the work that matters to you, you’ll be inside the only ring that counts.

The post The Craft is the End appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 2, 2021

Which Works Better: Habits or Projects?

In a recent essay, I argued that most people are trying to do too much. In the attempt to do everything that interests them, they end up making little progress on anything.

One reader noted a problem. Doesn’t this view of having a few serial projects contradict the idea of building good habits? Isn’t it the idea to make slow and steady progress on all your goals rather than work in intensive bursts?

This tension has come up before. After my book came out, I received an angry rant that argued that the intense projects I documented in Ultralearning were wholly opposed to the habit-centric philosophy of my friend and foreword author, James Clear, as stated in Atomic Habits.

So which is it: slow and steady habits or intensive projects?

As is my usual style, I think the answer is both. Habits and projects are both useful tools. They tackle different kinds of problems and have different limitations. Whether a habit or project is the appropriate tool depends on the nature of the goal you are trying to achieve.

The Habit-Building PhilosophyHabit building, the process by which behavior becomes increasingly automatic, has a long history.

William James, the father of scientific psychology, made habits a centerpiece in his magnum opus: The Principles of Psychology. Habit, he argued, is the fundamental principle of the mind. Behaviors link together until they become automatic and fall out of awareness entirely.

For more than a century, automaticity has remained a conspicuous theme in our understanding of the mind. Early behaviorists defined the shaping of stimulus and response as the basis of human action. More contemporary theories of skill acquisition focus on the shift from controlled, effortful processing to automatic behavior as a central feature of mental life.

The philosophy of habit-building takes these observations and relates them to our goals. If effort is the primary barrier to action, and repeated, rewarded actions become more automatic, then building better habits is an essential tool.

Habits VS ProjectsThere are a few ingredients needed to make habits work well:

The behavior can become routine. If it requires complex thinking or planning, it is not a habit, by definition. Sitting down to write each morning can become a habit; the act of writing itself cannot.

The behavior must be rewarding and enjoyable. In my essay on the meta-stability of habits, I point out that many behaviors we want to turn into habits aren’t enjoyable on their own. This means that while they can become easier and more automatic, they will never entirely transform into mindless routines.The goal requires patience more than intensity. Many goals face diminishing returns—the first hour of weekly exercise matters more than the fifteenth. Not all goals are like this. Getting a new job, launching a start-up or passing an exam have thresholds. Under a certain limit, the return on effort is zero.None of these mean that complicated, difficult or intense goals can’t benefit from habits. If I’m writing a book, I might benefit from a routine of sitting down to write every day. The habit-based tools can make writing more automatic, even though the goal itself isn’t maximally habit-friendly.

However, and this is important, having a habit won’t be enough. Book-writing is not as simple as churning out a page a day. Writing a book depends not merely on typing words, but editing, getting feedback, doing research, and obsessing a little too much about a topic that you think is important. Many terrible books have been written under the misconception that hitting a daily word count is the hardest part of writing.

Writing a book, then, is a project. It requires mental overhead to manage the complexity, as well as focus to push through frustration. It requires thoughtful, planned action that can never be made fully automatic.

Projects, particularly the philosophy of having a few, serial efforts, can be used to handle these difficulties.

Habits AND ProjectsAs tools, habits and projects coexist nicely. If you have a goal to write a book, the daily rituals involved in writing can be routinized. But you must recognize that the deep thinking and planning needed to write well can’t be automated. Good authors learn to combine both. They regularly set aside time to write. And they don’t kid themselves that writing a book is effortless, something they can churn out without much thought.

Habits are plenty for some goals, but others will need projects. I might set a goal of exercising daily—if I stick to it for long enough, it can eventually become an automatic behavior. But if I decide to run a marathon for the first time, it will likely require more than just my daily jog. If I want to win the marathon, I will need a lot more than just a habit.

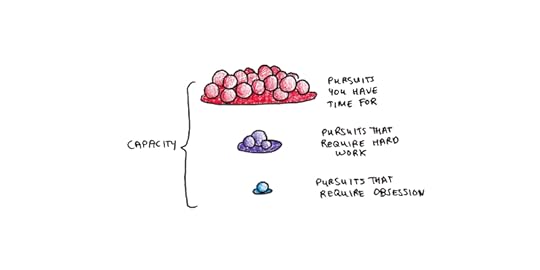

The Effort ContinuumThere are three different resources that you invest in a pursuit: time, effort, and attention.

Time is the most obvious—you only have so many hours in the day. Thus, even if it doesn’t require much effort or thinking, a time-intensive habit may bump against other pursuits. Even if you could use every minute of the day productively, you might still not have enough time to do everything you’d like to.

Effort is next. With careful conditioning, habits can become less effortful, but the effort rarely goes down to zero. This non-zero effort has two effects. First, when combined with the inevitable jostles of life, it can lead to a need to rebuild old habits semi-regularly. Second, it means that even if you can conceivably fit all of your desired habits into your schedule, you may not have the effort available to do them all.

Attention is perhaps the most constrained of all. If a project requires planning, reflection and obsession to reach completion, you’re probably limited to at most one or two efforts at a time. Anything more is going to reduce your performance sharply.

The number of pursuits you can take on at once depends on where they fit on this continuum. Habit-building can shrink the effort and attention required, although rarely to zero.

The aim should be, with every pursuit, to try to make the regular investments of effort required more habitual. However, pursuits have a degree of irreducible difficulty that requires focus. For the new author, writing a book would probably benefit from a daily writing habit. But this doesn’t imply that, habit installed, she ought to also learn French, practice guitar, start a business and take on a new role at work at the same time.

My Experience with Projects and HabitsI’ve spent most of my adult life pursuing a combination of projects and better habits. I’ve tried nearly every strategy out there. While this hardly reaches the rigor of a controlled experiment, I’d like to reflect on my experiences.

Exercise tends to work well as a habit. Although the time remains constant and the effort rarely goes to zero (fun sports are often an exception), the attention needed really can go to zero. Exercise enough, and you can think about other projects while working out.

Exercise is also the paradigmatic goal that requires patience over intensity. You can’t stockpile fitness, and being active throughout your life has enormous downstream benefits.

Writing articles works well as a habit, provided my goal is consistency. I’ve written over 1500 articles during the last decade and a half. That’s probably two million words of published material. Few could argue that I don’t have a solid writing habit.

Yet this habit doesn’t always drive improvement. Whenever I want to make a leap in my writing to something new, I have to put in a ton of effort. Often, the habit works against improvement, rather than for it, as I have such ingrained writing behaviors that they are difficult to dislodge.

Working on books, courses, or ultralearning efforts are all intensive projects. They’re areas where few results came from the mindless repetition of easy work. Yet, even here, habits often undergird my efforts. One of my first steps in the MIT Challenge, for instance, was establishing a studying routine. It was far from effortless, but consistency made it doable.

This blending of habits and projects has been a theme throughout my life. It’s part of the reason I get perplexed when I see the two approaches contrasted—as if it were one or the other. But if you understand how each works, and their respective limitations, you can make more progress than dogmatically sticking to either.

The post Which Works Better: Habits or Projects? appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 26, 2021

The Project-Driven Life

The majority of productivity advice is about the day-to-day. What tasks should you work on? When should you get up in the morning? How often should you take breaks?

This granular perspective is valuable. For most, it’s daily life that makes the difference. Big goals and plans matter little if they don’t translate into action.

When I view my own life, however, the biggest differences have come from projects, not tasks. These are large, complicated efforts that span anywhere from a month to a couple of years. It’s by choosing these wisely (and actually finishing them) that I’ve seen the most significant leaps.

What is a Project?

What is a Project?I contrast projects with goals.

A goal is your desired outcome:

Lose 15 lbs.Become a millionaire.Learn French.A project is a plan of action:

Stick to my daily workout for thirty days.Save and invest 25% of my salary for the next five years.Get a tutor, buy a textbook and practice speaking weekly.The line between goals and projects can be blurry. The difference is that goals emphasize outputs while projects emphasize inputs. A well-designed goal may be easy or impossible depending on circumstances outside of your control. A well-planned project, however, can nearly always be achieved because it depends mostly on your own commitment and effort.

When I wrote my book, Ultralearning, I didn’t focus on sales, external success, or other outcome goals. Whether it was a hit or a flop wasn’t up to me.

I focused on what I could control. I had a year to write. I still needed to run my business, spend time with friends and family, exercise and run my life. The project was to write the best book I could within those constraints.

Life as a Series of ProjectsProjects are how I organize my life. This includes big ambitious ones, like writing a book or doing one of my learning challenges, and it also includes small ones, like trying to sketch every day while on holiday.

Ten and twenty-year plans have always felt too restricting to me. Daily habits, while important, often lack the scope for more ambitious interests.

I find the discrete, finite nature of projects to be satisfying. Think about a project for a while, work on it to the best of your ability, and at a certain point, it’s finished.

The Life Cycle of a ProjectMy projects go through three phases: incubation, action, and completion.

1. Incubation

Incubation is essential. The longer and more ambitious the effort, the more it pays to choose wisely. You want to avoid picking poorly thought out projects you won’t actually finish. Spending more time thinking about projects tends to filter out fleeting or bad ideas. When you do act, you’re working on something that has kept your interest for months.

This incubation phase tends to work best when it occurs during another project or immediately following one. Those are periods when you generally don’t want to work on anything else, so daydreaming is relatively costless. When I’m itching for a project but don’t have a good one ready, I tend to settle for short ones—a month at most.

2. Action

Action is obvious. Nothing gets done without work. But I want to stress the experience of being in the middle of a project.

Good projects should make you a little obsessed. Obviously, you can go overboard, but a good project should make you think about it a bit more than you’d like to. If you can’t get yourself to think about it, even when you’re working on it, reaching the finish line is unlikely.

That isn’t to say effort is automatic. Nearly every project I tackle has its low moments: frustration, self-doubt, the feeling that maybe this will end in disaster. You’ll feel the tug of other, seemingly easier, more tractable projects. You’ll want to quit, take a vacation and not worry about it so much. Maybe you’ll feel like it was a big mistake.

In good projects, these moments are fleeting. Soon enough, you’ll get another breakthrough, some positive feedback or maybe take a weekend off, and the interest will return.

3. Completion

Finally, completion. Not all goals can be achieved in a single project, but all projects must end eventually.

I prefer to define project completion by setting a timeframe rather than an arbitrary milestone. Working on something for six months or a year, and trying to do the best I can within those constraints, works better for me than working until I achieve a particular goal. Sometimes this framing isn’t possible, but I find time-constrained projects easier to stick to.

Finishing a project is a funny feeling. There’s satisfaction, obviously, for a job well done. But after this immediate glow, there’s not much feeling at all. You rest for awhile, and then comes the itch to begin again.

Projects Give Life DepthIs this the best way to live? I’m not sure—it’s simply how I’ve settled into organizing my life. Some of that may reflect disposition rather than choice. My grandfather exhibited the same pattern of serial projects in his life, so perhaps it’s hereditary.

One advantage of organizing your life into a series of projects is that it can alter the perceived flow of time. We judge the passage of time by our memories. Distinct memories serve as landmarks of time’s passing. If you want your life to pass in a flash before you, then the surest way is to do the exact same things every day. Projects serve as landmarks in the hazy stream of our daily existence and draw out our perception of time.

I suspect projects aid in achievement as well. A project tends to be large enough to allow you to accomplish things that wouldn’t happen automatically on their own.

Perhaps the biggest reason is simply that a project is a reminder that life is finite. Oliver Burkeman’s book Four Thousand Weeks breaks down a human life into weekly increments. But four thousand is still a hard-to-visualize number. Taking year-long projects as the modal value, claiming that life is around 50 projects puts things into a sharper perspective. What will be yours?

The post The Project-Driven Life appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 19, 2021

You’re Trying to Do Too Much

I’ve been teaching online courses for 10+ years. A typical student has an array of varied interests and passions. They want to learn Spanish and guitar. And also machine learning and web development. Oh, and they want to start an online business—so they’d better learn marketing too.

I like these students. Heck, I am one of these students, so I relate to their enthusiasm.

The problem is that this enthusiasm is rarely matched with execution. Attempting several pursuits at once is a recipe for accomplishing none of them. Progress requires priorities. We need to tackle projects one at a time—not try to juggle them all at once.

The Mindset of Open OptionsI recently read Pete Davis’s excellent book Dedicated. In the book, he argues against the culture of “liquid modernity,” the idea that we always need to keep our options open and avoid committing to causes, communities and projects.

Davis argues that we live in a culture that prizes keeping one’s options open. It’s better to be maximally flexible, the popular reasoning goes, so that we can respond to any opportunity at a moment’s notice. Committing to anything, even for just a few months, locks away other possibilities, and is thus undesirable.

Examined closely, the reasoning behind liquid modernity doesn’t hold up. Even if you want a more varied life than the long-haul commitment Davis encourages, you still need to commit to projects for bursts of time to make progress. The person who commits to three-month projects may not achieve mastery. Still, they will get further than the person who merely thinks about doing those projects.

Tying Yourself to RealityWhile broad cultural forces may be partly to blame for our indecision, I suspect the problem my overly-enthusiastic students face is more mundane. It’s more fun to think about being good at something than to actually do the work to get good. Thus we daydream, rather than take action.

Daydreaming isn’t always bad. Sometimes thinking about something is better than actually doing it. This is particularly true when embarking on a new effort would break an existing commitment—a person who merely fantasizes about an affair is probably better off than one who cheats on their spouse. The person who sticks to their career, college or business throughout their difficulties will often get further than those who wilt at the first frustration.

The problem is that daydreaming alone doesn’t lead anywhere. None of the projects we imagine but never work on are ever realized. This can deflate even our daydreaming, as part of us knows, deep down, we’re never really going to do it.

The solution is to pick a project and see it through. Tie yourself to making a reality manifest, not simply thinking about it.

Give Ideas Time to IncubateA side-effect of committing to one project is that you end up putting off all the rest. By the time you finally start a project, you’ve been thinking about it for awhile.

This extra incubation time has two virtues. First, it filters out bad ideas. Since you only pursue the ideas that have stuck with you during your commitment to other projects, you end up pursuing projects you care about deeply.

Second, extra time results in better plans. As you ponder a potential project, you turn over the possible difficulties in your mind. Where will you find the time? What is your precise target? What constraints will you work under? All of these questions lead to sounder plans when you finally get started.

The notion that a commitment to focused action leads to longer and better thinking may seem paradoxical. But I’ve found it to be the case in my own efforts. Committing to fewer pursuits tends to make those you do stick to better thought out in the end.

Set Shorter ProjectsShort commitments tend to lead to greater accomplishment than long ones. How so?

It’s not the intention to commit that matters, but whether you follow through with it. A multi-year effort has a much higher chance at being abandoned than a three-month project does. Further, a three-month project can easily lead to another three-month effort in the same direction, provided the results from the first proved promising.

My advice is that if you’ve never stuck through a project that wasn’t externally enforced (meaning school and work don’t count), the best place to start is one that lasts thirty days. Once you’ve done a few of these, try a three-month project.

What about all those projects that require years to achieve? The answer is simple. Set your commitment for a short burst and give yourself the option to renew it at the end.

If you imagine you might quit midway, then it isn’t a commitment. It’s better to pick shorter commitments you will follow through on than to make lofty promises to yourself that aren’t actually binding.

Variety in Focus, Possibilities in ConstraintsThose who focus the most often end up with a great variety of accomplishments. Actually realizing the possibilities inherent in your life is only possible by subjecting yourself to hard constraints. Above all, recognize when trying to do too much generally results in nothing being done at all.

The post You’re Trying to Do Too Much appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 12, 2021

My Recent Reading: 10 Interesting Books on How We Think and Learn

My current project is a deep dive into the science and philosophy of learning by doing. (Which, ironically, has me reading a lot of books!)

Since my last post sharing interesting books was surprisingly well-received, I figured I’d share some more. Here are ten books I found thought-provoking:

1. Metaphors We Live by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson

1. Metaphors We Live by George Lakoff and Mark JohnsonThinking is fundamentally metaphorical. Instead of reasoning about things directly, Lakoff and Johnson argue, we reason through analogy to more primitive experiences. Language is a conduit. Bigger numbers are higher up. The mind is a container. Some of these metaphors are so deeply ingrained in our thinking, that we fail to recognize that they’re even metaphorical.

There are two radical ideas resulting from this view. The first is the idea that all thought derives from our more fundamental experiences from having bodies and dealing with physical things. The second is that since we need analogies to reason, what is objectively true hinges upon this analogical choice. Totally objective truth, independent of the choice of a metaphorical system, is impossible.

I was largely persuaded, but not everyone agrees.

2. The Principles of Psychology by William JamesWilliam James is considered by many to be the father of scientific psychology. His 1400-page text was the standard reference for decades. The paper edition was unwieldy, so I chose to listen to the unabridged Audible version, which came in at 47 hours.

Written over 130 years ago, Principles is an odd blend of surprisingly modern analyses and stranger fare. Detailed descriptions of localizing brain function are presented alongside cases debunking people being possessed by spirits.

The book is also an interesting guide into the metaphors that guide science. James frequently uses a “flow” metaphor of mentality, of circuits that flow and drain throughout the cerebrum.1Today, the computer metaphor dominates. Will the latter stick? Perhaps in another century and a half, our forebears will use a different metaphor for the mind that makes our computer analogy seem as dated as well.

3. The Nature of Expertise edited by Micheline Chi, Robert Glaser and Marshall FarrChi is famous for her studies describing physics experts and novices. Her work shows that experts solve problems using principles (e.g., conservation of energy) while novices focus on superficial elements (e.g., does it contain a pulley?). This theory builds on work by Chase and Simon, who argue that expertise is the accumulation of many discrete patterns.

This model implies that expertise tends to be domain-specific and extensive experience is the primary way we gain skill.

There’s a good chapter by Anders Ericsson dissecting the impressive memory feats of a professional waiter. The waiter was able to remember complex orders quickly and largely error-free. Although his performance declined on non-restaurant memory tasks, it was surprisingly general. Ericsson chalks this up to the method the waiter used having a degree of generality.

I would argue that real-life practice also pushes for generality. Laboratory tasks and textbook problems often have an unusual degree of regularity which encourages less flexible skills to develop.

Another interesting chapter, by Eric Johnson, argues against expertise. While experts do better than novices in many domains of uncertainty, they perform worse than simple linear regression models. We’re overly swayed by unusual circumstances and ignore base rates.

4. Reality is Broken by Jane McGonigalReality, McGonigal argues, is insufficiently motivating compared with games. To fix this we ought to make our everyday goals more game-like to inspire motivation.

I wasn’t convinced. While gamification may be alright for household chores or tedious tasks, I worry that it replaces the actual drive to do things. We need more meaningful work, hobbies and social relationships—not bullshit engagement tricks layered onto meaningless work.

The numerous examples of gamification mostly seem silly rather than threatening. However, the much more powerful “gamification” tools used to glue us to our screens and distort our politics are omitted. Thus, while the changes McGonigal suggests are mostly harmless, I think they harbinger a deeper illness in our society.

5. The Metaphysical Club by Louis MenandPragmatism is a uniquely American philosophy. This book explores the lives of four of its most influential members: Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., William James, Charles Saunders Pierce and John Dewey. It explores the spectrum of American thought from the outbreak of the Civil War through the beginning of WW2.

Pragmatism argues that ideas are tools. Truth is defined by usefulness, not an exact matching to reality.

James tells a story of a group of campers arguing about a squirrel on a tree. As they run around the tree, the squirrel moves to the opposite side so they can’t see it. They debated whether they truly ran “around” the squirrel. James thought the debate was silly. “Around” could mean either a circle on the ground, in which case they had gone around, or in terms of a relative position compared to the squirrel, in which case they hadn’t. No practical issue depended on this definition, so it wasn’t a real question.

I like pragmatism as an overall attitude toward the biggest questions in life. But it may be ultimately self-defeating, if only because it doesn’t seem useful to collapse truth into mere usefulness. Still, the writing of James and Dewey is some of my favorite in philosophy for its humanism and lack of pretentiousness.

6. Fear and Courage by S. J. RachmanWhat is fear? What is courage? Applying lessons from clinical psychology, Rachman provides intriguing insights into these questions.

He argues that fear isn’t monolithic—instead, he argues that fear is a set of three loosely coupled components: physiological arousal, subjective feeling, and behavior. Exposure therapy works well, but we’re not entirely sure why. Courage is not fearlessness; it is the absence of fear behaviors (e.g., avoidance, freezing) in the presence of subjectively felt fear.

Beyond this theoretical work, I found his analysis of examples of genuine fear fascinating. Rachman discusses the Blitz in London (in which psychologists massively overpredicted the panic) to the conditions of courage in some of the most dangerous tasks imaginable (heavy bombers in the RAF, some of which had only a 10% survival rate).

My favorite quote: “One of the major weaknesses of all psychological theories is the assumption that people are highly vulnerable to threats and stress. The theories are designed for creatures more timorous than human beings.”

7. The Computational Brain by Terrence Sejnowski and Patricia ChurchlandIf the brain is a computer, how does it compute? Sejnowski and Churchland argue that early attempts to understand mentality often avoided dealing with the actual “hardware.” Proposed psychological models assumed someone else would figure out the “implementation” in neural circuits.

But implementation isn’t so separable from function. The brain’s architecture—in which billions of neurons communicate across trillions of synapses, with highly constrained, dynamic connectivity—is not only a limit on plausible theories of the mind; it is also a powerful tool for understanding it.

Sejnowski and Churchland argue for a model that resembles the deep neural networks used in machine learning. If accurate, this makes the brain much more like a giant, sophisticated look-up table than has previously been thought.

8. Cognitive Training edited by Tilo Strobach and Julia KarbachDoes brain training work? Mostly no.

This is the conclusion I gathered after reading this edited volume comparing many meta-analyses on the idea of cognitive training. The consistent finding: training reports some benefit for near transfer but little benefit for far transfer tasks.

However, the book itself was a jarring experience, with many researchers seemingly fighting against the conclusions of their own data.

My take is this: scientists like to devote their careers to studying something that works, not a dead-end. This biases the field in favor of optimism as the skeptics tend to work on different problems. Usually, mild successes are congratulated, while more typical failures are calls for more research and study.

My basic critique goes deeper than the data: how can a mental activity be so generally useful that improving it would influence the performance of tons of everyday tasks, yet be so under-practiced that a few minutes per day of specialized training is enough to make significant boosts?

9. Dewey’s Laboratory School by Laurel TannerJohn Dewey’s book Democracy and Education made him one of the most prominent public intellectuals in America at the beginning of the 20th century. Before this, however, he set up a school to test his theories of philosophy in action.

Called the Laboratory School, Dewey’s model was for students to engage holistically with subjects integrated with real life. There were no separate classes for math or history. Instead, students were taught both through an ongoing project that simulated the historical development of textile production.

More hagiography than history, I found Tanner’s account to be overly rosy in places. Given that the Laboratory School was populated by children of his University of Chicago peers, lessons drawn from the school are probably not universal. Still, I admire the boldness of the experiment.

10. Mind and Society by Lev VygotskyVygotsky argues that the processes of learning and development aren’t separate. By assisting children to perform tasks they can’t do on their own, we can spur them to advance to higher stages of ability and reasoning. While interesting in its own right, I was mostly drawn to this book because it plays a central role in many of the debates over how minds work.

During my reading, I’ve found two competing traditions. On one side we have the Cognitivists. These are people like Chi, Ericsson, Simon and Newell. They tend to work from the assumption that the mind is an information processing tool, with the goal of psychology being to figure out the function.

On the other side are the Constructivists. They tend to see all mentality as being embedded in larger social structures, communities and shared practices. Vygotsky’s work here is important since it establishes the importance of social factors in mental life, learning and development.

I’m often torn between the two camps. My mental model of how the mind works is more closely allied with the Cognitivists. Yet, I tend to agree that skills are often more local and context-bound than many assume. This puts me in a bit of an awkward position in reading evidence, since I find my own thinking doesn’t neatly fit into either tradition.

Some Thoughts on Doing ResearchOne of the challenges (and opportunities) of researching a big topic is just how many different views could plausibly relate. It’s easy to get comfortable with one set of results only to realize there’s an entire discipline that weighs in on the questions you ask.

The paradox of learning is that the more you know, the more you realize you don’t. Each answered question spawns myriad doubts. I’m about fifty books and a hundred papers into this project so far, and there’s still a lot to go.

The post My Recent Reading: 10 Interesting Books on How We Think and Learn appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 1, 2021

Lessons Learned from 5 Years and 5000+ Students in Top Performer

Just over five years ago, Cal Newport and I launched the first session of Top Performer.

The release was shortly after the publication of Cal’s book So Good They Can’t Ignore You. Cal’s career-advice book dispelled the myth that following your passion was the key to fulfilling work. Instead, the heart of great careers is rare and valuable skills—in other words, being a top performer at your job.

We designed the course to offer a structured approach to career improvement. How can you figure out how your career really works? How can you produce stellar work that will get you noticed (and rewarded)? More deeply, how can you build a career that gives you the lifestyle you want, instead of just endless ladder climbing?

These aren’t easy questions to answer. Over the last five years, we’ve had the privilege of working with over five thousand students to try to find the answers. This experience has taught us a lot.

Introducing Top Performer 2.0Listen to this articleIn keeping with the themes of continual improvement in the course, we decided to update Top Performer. In doing so, we’ve added dozens of new lessons, interactive worksheets and even some additional mini-courses to go alongside the main program.

We’re calling it Top Performer 2.0, and we’ll be taking new students for a special session of the course until October 8th.

Five Lessons Learned from 5 Years and 5000+ StudentsIt’s been incredible working with so many students over the years with Top Performer. Here are some of the biggest lessons we’ve learned since the early days of the course:

Lesson #1: The Machine Learning FallacyAn inside joke among those who help run Top Performer is how often the students’ first idea about how to improve their career is to learn more about machine learning. This is not to say that machine learning isn’t valuable (it is), but its popularity in this context highlights the degree to which many imagine that the key to career success is found primarily in mastering an exotic skill.

In reality, learning to first become reliable, and then second to produce what you say you’re going to produce at a high level, is typically a much more effective platform on which to build advancement. These abilities will get you noticed, and it’s once you’re noticed that exciting opportunities to tackle big projects, or learn fancy new skills, will emerge naturally.

Lesson #2: Find Existing Paths Before Forging Your OwnAnother common pitfall we observed was students’ tendency to want to write their own story about how a particular career works instead of taking the time to master its reality.

The aspiring non-fiction writer, for example, often wants to get started immediately writing 1,000 words a day on their newly purchased, and carefully configured, copy of Scrivener. It’s an exciting but tractable challenge and gives them a compelling sense of progress. The problem, however, is that this isn’t actually how people end up becoming professional non-fiction writers. A lot more time likely needs to be invested in your idea. You need to gain more professional writing experience. You need an agent before you write even your first words. And so on. Not all energy expenditure generates equal results.

To get the most out of your time, it’s critical to ensure your efforts are aimed where it most matters.

Lesson #3: Do Real WorkOne of our first Top Performer cohorts included a young architecture associate. He was eager to work deliberately to advance his career and soon found himself poring over new design theory textbooks in his free time. The problem, however, was that learning new design theory was not on the critical path to him getting ahead.

A better project might have been to focus on managing client relations, mastering design software or focusing on project pitches—in other words, skills that directly interact with the stakeholders that will determine his success. Many are more comfortable with abstract, theory-style classroom learning, but in the professional context, it’s almost always better to practice the specific concrete skills that matter for your specific job.

Lesson #4: The Grad School DefaultWe were surprised, at first, by how many of our students were leaning toward graduate school as a sort of default fix to feeling stuck or bored. As someone who teaches a lot of graduate courses, Cal can speak from experience when he says that graduate education can be immensely positive for your career. But this only holds when you deploy this education for a specific reason.

The mantra we began to preach is that you should enroll in a graduate program only if there is a specific type of position you want, and you have good evidence that getting this degree from this program is what is needed to obtain that position. Never spend multiple years (and multiple tens of thousands of dollars) going back to school based only on some vague hunch that having more degrees will open up more opportunities.

Lesson #5: Don’t Ask People for AdviceFiguring out what skills matter for your career path can be surprisingly tricky. One of the best ways to determine where to aim your deliberate improvement efforts is to learn from those who have already gotten to where you want to go. Getting this information from someone, however, is harder than it seems. Why?

As it turns out, most people are very bad at giving advice based on their own experience. If you ask people for their advice, you end up putting them on the spot to come up with something useful sounding to offer in response. This leads to a panicked internal search for anything that sounds right. You’ll end up with coherent advice, but not necessarily the right advice.

The better alternative is to instead ask people to tell you their story. Like a journalist, extract from them the beats of their career, pushing where needed to help understanding what exactly it was — accomplishments, timing, a particular skill-base — that allowed them to make the more important leaps. Then you should go back through this reporting and extract the relevant advice on your own.

—

Interested in taking the leap to improve your career? We’re holding the first session of the newly expanded Top Performer 2.0. Registration will be open until October 8th at midnight Pacific Time.

The post Lessons Learned from 5 Years and 5000+ Students in Top Performer appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 20, 2021

Want to Write for a Living? The 7 Things I Wish I’d Known

Many people dream of becoming professional writers. Getting paid to share your thoughts with strangers is a pretty good gig. I’ve been a full-time writer for over a decade, and in the spirit of my last post on college advice, here’s what I wish I had known before I started writing.

First, though, some caveats. Writing is tough. Few who write regularly make a living doing it, and many of those who do barely scrape by. As with entrepreneurship, most people would probably be better off with a regular job than trying to earn a living writing.

That said, even if writing isn’t your primary source of income, it can still be worthwhile. Writing, like painting, music or languages, is fun. It can also be a great source of opportunities because it has spillover into other professions. Thus, becoming a decent writer is often a good investment.

Finally, writing is a broad discipline. I make money through courses and non-fiction advice books. Therefore, what I have to say will mean little to someone who wants to be a journalist, novelist or poet. Although the underlying skill is similar, the industry isn’t. Don’t expect my experience to transfer if you’re hoping to be the next J.K. Rowling or Tom Wolfe.

That said, here’s my advice to people who enjoy writing and wouldn’t mind being paid for it, too.

1. Your Audience is Your Most Valuable Asset

Success as a writer depends almost entirely on having a critical mass of people who want to read what you write.

A common mistake new writers make is trying to monetize too quickly. Many new writers have only a handful of subscribers, yet they try to write books or create courses to sell.

I understand this impulse. There’s a desire sometimes to validate your writing early on by proving you can earn a little money from it. But this gets the difficulty of professional writing backwards. The hard part isn’t coming up with something to sell, but having people who plausibly want to buy it.

A good general principle is not to try to sell anything (including writing a book) until you have 5000 regular readers. If that sounds like a lot, it should! Getting 5000 people to read your writing consistently isn’t easy—but it shows that you have something people are interested in. That’s why building your audience should be your priority.

2. Don’t Worry About Quality Until You’ve Written 100 Essays

Many writers obsess over their style when they haven’t produced enough to have one yet.

One hundred essays is probably a good benchmark to hit before worrying about whether what you’re writing is good or not. Again, if that sounds like a lot, it is! Writing one hundred essays is probably a year’s worth of work. But it’s a year that will tell you what kind of writer you are and give you a starting point for trying to improve.

Writing this much will also get you over your inhibitions about putting thought into text. Trying to produce the perfect essay right out of the gate will only lead to crippling writer’s block.

3. Write What You Like to Read

Emulate the writing you enjoy reading. There are two reasons for this:

First, it’s next-to-impossible to write well in a style you don’t enjoy. A good piece to write is something you would choose to read.

Second, imitation can be a starting point for creative success. While I don’t condone plagiarism, there’s nothing wrong with dissecting a piece of writing you like and trying to produce something similar. Often the finished product will look quite different, but learning what makes other writing work will help your own writing improve.

A side-effect of this process is that your writing will often start out looking like a second-rate version of an author you like. This is normal, and it doesn’t last forever. My early writing had a bit too much influence from Steve Pavlina, for instance. But over time, you add more and more influences, and your style will evolve spontaneously from the unique amalgam.

4. You May Never Feel “Smart Enough”I’ve never felt qualified to write. I used to think the feeling would go away as I learned more, grew older or gained recognition. But I believe now this feeling of insecurity is a stable illusion caused by the very act of improvement.

Two factors influence this insecurity. The first is that your taste inevitably outstrips your ability. You can always appreciate writing that is better, smarter, more thorough and incisive than your own. You get better as a writer—but improve even more as a reader. The confidence gap widens, even as your absolute abilities grow.

The second factor is that there is no end to mastery. You can always learn more about a topic. And each piece of learning tends not to consolidate your views but fractionate them—providing more opportunity for nuance and distinction. Every piece of writing beneath your current understanding seems over-simplified. Every piece that’s above it seems pedantic. Your level of understanding rises, but the two sides forever remain.

I don’t prescribe blind confidence. Instead, acknowledge your perspective will always be imperfect and find the courage to create something anyway. Use the doubts you feel as a motivating force to better yourself, not as a barrier to prevent getting started.

5. Don’t Write Alone

Success as a writer means navigating the ever-changing sea of systems, social media networks and outlets people use to find success. While marketing alone won’t make you successful as a writer, it’s also true that an absence of this knowledge can be fatal.

Unfortunately, this type of information is nearly impossible to learn from a Google search. You need friends who also write. That way, you can share what is working, learn about opportunities, and refer to each other’s work.

Networking and marketing savvy tend to be force multipliers. They won’t help you if your writing is paltry, but it becomes easier to make friends who will help you if you write enough interesting stuff.

6. Look for Extreme BetsMost writing will never be read by anyone. Of what remains, the vast majority will stay confined to the narrow corner of the internet they were birthed into. But a few pieces will travel widely. It only takes a few such pieces to build a career.

The easiest way you can increase your chances of success is simply to write more. Writing has a large random component; thus the optimal strategy tends to be prolificacy.

However, there are also predictable components to what makes writing interesting. Producing something one-of-a-kind doesn’t guarantee people will like it. But if they do like it, then at least you won’t be competing against the hundreds of near-substitutes.

The MIT Challenge remains my most popular project. Much of that I couldn’t have anticipated. But part of it is that it was such an extreme bet that there was little else like it online.

I still recommend quantity-first as a strategy. But once you’ve written your first hundred essays, start thinking about how you can push into an extreme that will set you apart.

7. Use Writing to Build Indirect Opportunities

Despite all my previous advice, it is rare to achieve success solely from writing. Given that I make money from selling courses, it’s not even clear if I count in this regard.

However, writing can be a good tool for leveraging other opportunities. Sometimes that means landing a more prestigious job, getting on a cool start-up, or just meeting cool people. Being an engineer, accountant, or manager who also writes well is a powerful combo.

While it’s great to make a living writing, it works best when you’d be happy to do it for free.

The post Want to Write for a Living? The 7 Things I Wish I’d Known appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 14, 2021

The 7 Things I Wish I’d Known Before College

We live in a bizarre culture. We expect teenagers to commit to a field of study that will often shape their entire future career. And we ask them to choose their path based on whether they liked their freshman class in that subject.

This is absurd. Work is utterly unlike an intro class. Liking your psychology class doesn’t necessarily mean you should be a therapist or that there will be a job for you once you graduate.

Much of the advice we give to new college students is terrible. Here is some advice I wish I had known when I first went to university.

1. Apply Everywhere, Even “Out of Reach” Schools

Many students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, don’t get into prestigious schools. This isn’t because they lack the ability, but because they don’t apply. Two myths seem to perpetuate this: first, top schools are too expensive, and second, the chances of getting into a top school are too low to make it worthwhile.

The truth is many elite institutions have generous financial aid packages, so only the children of the richest pay the sticker price. Thus “I can’t afford Harvard/MIT/Stanford” is often false.1

Second, the odds of getting into an elite school aren’t as dismal as they seem. As I reviewed here, the bare odds of getting into Harvard are about one in twenty. That may not seem great, but the reward-to-effort ratio for applying is still pretty good.

This advice will probably strike some as obvious. Yet, I think there’s a stark division here. Some belong to a rankings-obsessed social-climbing class that will do anything to get their kids into a better school. In contrast, others are blissfully unaware that the other half are paying so much attention to what school you went to.

My advice is to split the middle. I don’t think sacrificing yourself in high school is worth it to slightly improve your odds of going to a top school. But, I also think people outside of the rankings-obsessed strata of society would benefit from applying a bit more broadly.

2. Don’t Choose Your Major Because You Like the Classes

Classes are a terrible proxy for whether you’ll enjoy the work. This is especially true at the freshman level, where generic classes are often taught in big auditorium sessions. Psychology 101 is nothing like clinical therapy, research psychology, or, more likely, working at an office doing something unrelated to psychology.

What’s more, you can always learn things outside of school. Since I graduated, I’ve taken dozens of classes online in a range of subjects. I don’t need the pressure of deciding whether I want to do it for my entire life to enjoy the class.

If you arrive at college with a strong intuition of what you want to do with your life, by all means, major in that. But if you’re like most students and have no idea, then deciding your major based on which classes were coolest is a terrible idea.

3. Seriously Consider Majors that Pay Well

The worst advice we give students is to ignore how much money specific fields tend to make. After all, making money is a grubby business, so we tell kids to pick fields of study based on intellectual affinity, academic curiosity and following your passion.

This is bad advice for a few reasons. The first is simply that most college students live in “student poverty,” a strange pseudo-communism where everybody is broke. Thus, one’s choice of major functions like your taste in music or clothes: a way of showing off your personality. This tends to mask the stark differences between the economic prospects for an actuary versus an art history student.

The second reason is that when you’re young and broke, there’s a certain romanticism to it. I remember feeling like money didn’t matter much when I was in my early twenties. Everything I wanted to do was pretty cheap, and none of my friends were rich. But eating ramen noodles and bicycling through the rain to avoid splurging on bus fare gets old in your thirties. If you decide you want to have kids, own a house, or live in a trendy city, you can’t ignore the financial aspects of those decisions.

In my senior year of business school, we were shown the typical starting salaries for graduates with different specializations (accounting, finance, marketing, etc.). It was stunning how much of a range there was, even right out of school. To this day, I have no idea why this information wasn’t at least presented to students when they were freshmen. Still, I think the onus is upon every new student to at least seek this information out.

Sorting majors by median salary and picking the highest one you find interesting enough to get through four years of is perhaps extreme—but only a bit.

4. Enjoy College to the Fullest (Don’t Be a Grind)

You can get good grades without exhausting yourself. Knowing how to study effectively is critical, which is why I wrote about it so extensively when I was in school.

But one thing no one tells students is that soon after graduation, nobody cares about grades. In technical fields or academia, grades may help you land a particular first job or graduate position. But beyond this, it’s incredible how little people pay attention whether you were a C or A+ student.