Scott H. Young's Blog, page 25

May 9, 2021

The 10 Essential Strategies for Deeper Learning

Learning can be tough, but it doesn’t have to be mysterious. Ample research shows that there are better ways of studying, not just for passing the test, but for creating deep understanding.

Below are ten essential strategies you should keep mind any time you need to learn something important.

1. Practice on Questions From the TestThese lessons are drawn from my course, Rapid Learner. We’ll be having a new session soon—sign-up for the waiting list here.

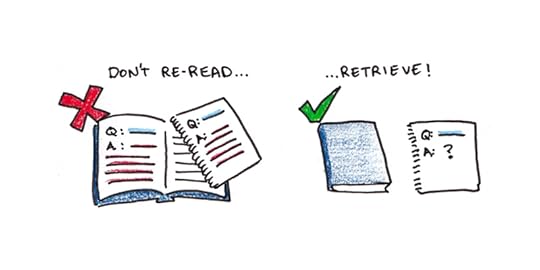

All skill depends on practice. So too, with memory. If you want to remember something, you need to practice remembering it, not just looking at it.

Retrieval practice—where you shut the book and try to recall what you’ve learned without looking at it—is one of the most effective studying techniques.1 It beat fancier techniques like concept mapping in head-to-head trials.2 Retrieval also works even if you can’t get feedback.3 The value of actively trying to remember goes beyond simply correcting mistakes.

The best questions to test yourself on are those most similar to the test. But, if you don’t have access to those, it’s better to practice harder forms of practice—think writing an essay and not multiple choice. These desirable difficulties lead to more efficient studying over easier tests.4

2. Expose Yourself Multiple Times to the Same Information

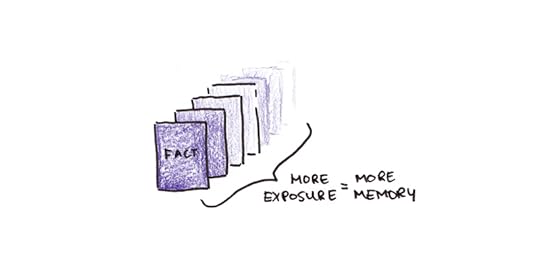

If the first key to learning is practice, the second is repetition. Memories tend to diminish in strength over time, quickly at first and more gradually later. This is known as the forgetting curve, and its relentless erosion of our memory is the bane of all students.

Yet there is a strategy that causes memories to be retained longer—spreading out your exposure through time. If you can be exposed to a fact, idea or procedure multiple times, you’ll retain it far longer than if you experience it only once. Even better if these exposures are spread out over weeks instead of just hours.

The lesson: avoid cramming if you want to learn things deeply. Whenever possible, test yourself throughout your classes, not just on the current unit, but on previous ones. This sounds tedious, but it ends up saving time needed to learn everything right before the exam.

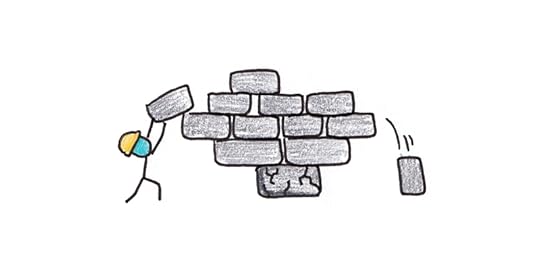

3. Drill the Basics Until They’re Automatic

Complex skills are built out of simpler parts. Basketball is shooting, passing and dribbling. Drawing is proportions, lighting and lines. Math is addition, multiplication, algebra and more.

One challenge to learning is when the basic parts aren’t fully learned, performing more complicated skills quickly becomes impossible. Researchers call this cognitive load, and note that it is a major impediment to learning hard skills. Direct instruction, one of the most successful teaching methods ever studied, overcomes this by ensuring core skills are mastered before moving to harder tasks.5

Whenever you’re struggling to learn anything, always ask if you’ve mastered the basics. The feelings of inadequacy that frustrate harder skills can often be remedied by fixing the foundation.

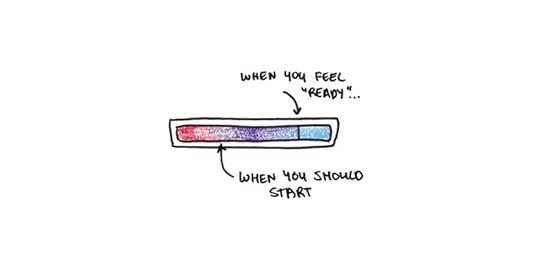

4. Test Your Knowledge Before You’re “Ready”

Most students know they eventually need to test themselves on what they’ve learned, if they’re going to learn it deeply. But many feel that they aren’t “ready” for this stage yet, so they stick to re-reading their notes at first.

Yet clever experiments show that this is a mistake. A clever experimental manipulation found that the students who would have chosen passive review, nonetheless did better when they were forced to do practice instead.6 Other research shows that taking a test before you learn the material can prime better learning.7

The rule of thumb should be to test yourself before you feel ready. The more you can shake the feeling that you need to do well on the first attempts at practice, the better you’ll learn.

5. Slow Down to Understand Better

Few things are more frustrating than leaving a lecture feeling, “Huh?” You know you need to understand to keep going, but the big picture eludes you.

One reason this happens is because of our limited working memory. This concept corresponds roughly to what we think of as our mental bandwidth. It can only hold a few items at a time.8 If you’re required to put together a dozen different pieces to understand an idea, then, you’ll be hopelessly lost.

The fix is to slow things down. Write out what you’re trying to learn on a piece of paper, and go through each sentence or step in a calculation one-at-a-time. By offloading some of the problem to paper, you can free up space in your working memory to see the connection you need.

6. Get Clear on What Confuses You

If you’ve slowed things down and you’re still stuck… what then? In this case, you need to flip the problem. Instead of trying to understand the idea all at once, you need to ask yourself what’s missing to understand it.

Take a complicated math problem you don’t understand. Try walking through each step in the calculation. At which line of the derivation do things not make sense to you? Those might be points where a concept was being applied that the teacher assumed you understood. It might be two or three steps confusingly compressed into one. In either case, you now have a much more specific question to ask—and the answer is much more likely to resolve your confusion.

This doesn’t just apply to math classes. Confusing paragraphs in philosophy can be stepped through, one-word-at-a-time, making sure you understand the point of each. Explanations for concepts in business or biology can be walked through until you find the sentence you don’t understand.

Debugging an understanding is tough work, but it ultimately saves far more time than the frequent alternative—rote memorization.

7. Never Multitask

Multitasking is a misnomer. We’re never actually doing two things at once. Instead, when we multitask, we’re quickly switching between tasks in our minds.

Each of these switches comes at a cost, however. The contents of the previous task stay with our mind for awhile, even as we work on the new one. This cognitive residue makes mental performance harder, and can make learning nearly impossible.9

Obvious fixes are to silence your phone, turn off email and remove noisy distractions. Music with lyrics ought to be avoided, since these take up space in our working memory devoted to processing language. Instrumental music does better, but quiet (or white noise, if silence is impossible) does even better.10

8. Don’t Get Too Far From the Real Thing

What if your goal isn’t just to pass a test, but to learn a real skill? Here the problem of transfer rears its ugly head.

Many studies show that what is learned in one context is often not transferred to other contexts.11 Some of this can be blamed on students failing to learn things deeply in the first place.12 By obtaining only a superficial understanding, it’s harder to abstract the deeper principles behind things.

Yet a deeper problem is simply that using any knowledge depends on a whole set of invisible skills.13 Knowing a programming concept, like recursion, for a test is one thing. Being able to notice that the current problem in your work would be best solved with a recursive algorithm is another.

One fix is to always keep the real thing you care about close when learning. Going back between more formal learning and real projects can be helpful. This not only prevents knowledge from ossifying into something purely academic, but it also acts as a check to ensure you’re learning what mattered most in the first place.

9. Pretend to Teach It

The teacher often learns more than the student. Teaching something, even if just pretending, forces you to confront what you know and don’t know.

Putting something into your own words checks whether you really understand it, or are just memorizing a definition. Coming up with analogies that would help someone else learn, helps you figure out if you have a good picture for how things work. Showing how to solve a problem, makes clear you’ve mastered it.

Teaching something combines many of the techniques mentioned previously. If you do it with the book closed, it’s a form of retrieval practice. It forces you to master the basics, slow down to deal with your own confusions and gives you feedback. What’s more, since the goal of much learning is to leave with a deep understanding, being able to teach something is often the real thing that matters. If you can share an idea, you can be sure it doesn’t get stuffed away to a dusty, unused corner of your mind.

10. Find Your Reason to Be Interested

What’s your motivation to learn? Is it to pass tests or develop a deep understanding? Research shows that students with the latter motivation, ironically, do better than those whose only aim is to pass the test.14

Genuine interest can’t be faked, but it can be fostered. Ideas are often presented in a detached way in classes. Their history, when they were bedeviling puzzles, not just established facts, and their future applications are often omitted to save time. If you can find a reason to be interested in insight and not just a grade, you’ll often end up with both.

Next week, I’ll be offering a new session of my six-week course, Rapid Learner. If you found these strategies helpful, but want to master your own tools for learning well, then you might want to join our next session.

Before we open, I’ll be sharing three more lessons like this one. Stay tuned!

The post The 10 Essential Strategies for Deeper Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 3, 2021

A New Understanding of Effort

Why is it harder to watch a physics lecture than Netflix? Why does a cognitively demanding activity, like playing a video game, create a pleasurable state of flow, while math problems rarely feel that way? What makes something effortful?

At first glance, these questions seem too obvious to ask. Of course video games are less effortful than math problems—video games are fun!

Yet, I think an understanding of effort is supremely important. Many of the goals we want to accomplish will require a lot of it. If we have the wrong theory for how it works, many of our systems will fail or otherwise be poorly designed.

The Failure of a TheoryUnfortunately, until recently I couldn’t find a satisfying explanation of how effort works. The dominant model was Roy Baumeister’s ego depletion theory. This argued that willpower was a resource. Use it up and you (temporarily) have none left. Like a muscle, however, it could be strengthened.

Yet, ego depletion theory was a major casualty in the replication crisis. Baumeister’s preferred explanation for the source of the resource—glucose—ended up being wildly implausible.1

The theory was attacked on psychological grounds. Giving a reward could increase persistence, suggesting it wasn’t a physical limitation.2 Changing beliefs about willpower could also alter performance—another strike against a capacity constraint.3

Effort as Opportunity CostThis is why I was so excited to read the paper “An Opportunity Cost Model of Subjective Effort and Task Performance” by Robert Kurzban et. al.. They suggest a new way of thinking about effort in terms of opportunity costs. From the abstract:

Specifically, certain computational mechanisms, especially those associated with executive function, can be deployed for only a limited number of simultaneous tasks at any given moment. Consequently, the deployment of these computational mechanisms carries an opportunity cost – that is, the next-best use to which these systems might be put. We argue that the phenomenology of effort can be understood as the felt output of these cost/benefit computations. In turn, the subjective experience of effort motivates reduced deployment of these computational mechanisms in the service of the present task.

The idea here is that the brain has many different functional centers. The part at the back of your head, called the occipital lobe, processes vision. At the side, there’s audio processing and language comprehension.

A lot of these functional centers are more-or-less single-purpose. Your visual cortex can process input from your eyes, but it can’t suddenly switch to help you with hearing something better, in case you’re in a dark room and want to devote more bandwidth to listening to an audiobook.

On the other hand, the frontal cortex, which includes centers believed to control central executive processing, is more flexible. It also makes connections through the basal ganglia, similar to the motor loop, which suggests that it may also be partly responsible for the experience of thoughts happening one at a time.

Kurzban and his co-authors argue that since the executive has many possible uses, it would be adaptive to have a system that ensures it is being applied to the most valuable activities. This experience of the cost-benefits of using this fixed resource would manifest itself as effort. When your current activity doesn’t feel like a good use of limited mental bandwidth, you feel like doing something else (like daydreaming or playing with your phone).

Computer Time Sharing vs Fuel Tank MetaphorsWhile ego-depletion is like a fuel tank, opportunity-costs are like computer time sharing. The computer resources don’t get depleted or used up, but they are constrained, and thus effort would be the experience that what’s occupying your executive processing just isn’t worth it.

If you’re like me and you remember when computers were slow, you have had the experience of trying to do something with a computer that’s running a major background process, like a backup, virus scan or rendering operation. You want to play a game or watch a movie, but the game depends on the same computational resources as the background process, so you have to decide whether to shut it off or wait until it is finished.

This paper argues for a similar process, except that these opportunity costs are experienced as effort rather than conscious decisions to allocate resources.

Applying This Model of Effort to Your Goals

Applying This Model of Effort to Your GoalsWhat does this model of effort say about striving that a resource theory gets wrong? I can think of a number of important implications:

1. Effort Depends on Alternatives

How effortful something feels will depend on what it is being compared against. Thus it is more effortful to work with your smartphone nearby, thus cuing you to the possibility of quickly going on Instagram, than it would be if that cue wasn’t present.

This suggests to me an alternative mechanism for why habits can become easier. Since habits, in the sense of completely automated behavior, don’t really apply to complex routines like working out or studying, it’s an open question how effortless they can become. However, if we see effort as a comparison of alternatives, one thing habits provide is a reduced salience of possible alternatives.

Thus studying a math problem is much more effortful when, in moments similar to that one, you often play video games or surf the internet instead. Their salience is high and thus the opportunity cost of continued studying is high too.

2. Willpower Depends on RewardThe opportunity-cost model has a similar implication to Robert Eisenberg’s learned industriousness. Eisenberg’s theory was that when you get rewarded for effortful activity, the experience of effort itself becomes less unpleasant and thus you more easily choose high-reward, high-effort activities over low-reward, low-effort ones.

In an opportunity-cost framework of effort, we can increase our self-control by learning that certain actions yield positive results. The authors give the example of a smoker resisting temptation a few times, thus giving evidence that this is an effective strategy, and thus making it more likely to resist in the future. If persistence on a difficult math problem pays off with finally understanding it, you’ll find it easier to persist through frustration in the future.

3. Discipline is Specific, Not General

Both the resource and opportunity-cost theories of effort suggest our capacity for willpower may be improved, but they critically imply different ways this might come about.

Resource theories suggest the capacity is like a muscle. Thus, training on general-purpose disciplining activity will increase the capacity for any kind of activity that requires self-control.

An opportunity-cost theory, in contrast, suggests that what is learned when increasing self-discipline is the reward contingencies for certain activities. If you can establish that a certain activity is rewarding compared to alternatives, over time it will become less effortful.

The contrast between these two theories reminds me of the contrast between formal discipline in education and the notion that acquired skills are quite specific. In both cases, the intuitive (but, ultimately false) theory was that the mind was like a muscle, with general-purpose training effects. If the opportunity-cost theory is true, then it isn’t like that. Willpower depends heavily on learning the value of activities, which will be much more specific.

I don’t want to go overboard with this analogy, however. It’s certainly possible that some kind of high-level idea of discipline might be able to operate between tasks and contexts. Something like a rule which says, “I always stick to my goals” and then this rule itself becomes more powerful as it is rewarded. Yet, this theory does suggest for me a different way of thinking about improving your self-discipline generally. Once again, doing the real thing seems to matter and bulk training on irrelevant activity seems less effective.

Further QuestionsI’m optimistic that further experiments will validate at least some of the ideas in this theory, which seems much more plausible than the resource theory it supersedes. Yet, there are also complexities that need to be sorted out:

If effort is opportunity cost, why do tasks become more effortful, the longer we persist at them? My own experience suggested this might be due to social factors—you look at the clock, see you’ve been working for an hour and say “that’s enough.” Other motivational researchers argued that motivation itself was a balance between driving and consummatory forces.4 Still, the resource model made the decreasing persistence on tasks an immediate consequence, while this theory makes it more complicated. As go with paradigm shifts, some features become central ones to be explained while others are explained away.What explains the two-task experiments, whereby effort on a first task resulted in reduced performance on a second task? The authors suggest that it might be because, in experiments, subjects feel a certain social obligation to perform. Expending effort on the first task would seem to meet that obligation, after which there is less incentive to continue on the second task. Still, it would be nice to see follow-up experiments that look at this more closely.Why are so many valuable activities effortful? If effort is a seemingly rational process of assessing opportunity costs, then why are so many useful activities–exercising, studying, working–effortful, while seemingly useless ones are so fun? Evolutionary mismatch might explain some of the discrepancy. In other cases, it may simply be that our motivational hardware is less sensitive to the kinds of long-range benefits of working hard. How does this notion of effort tie into other experiences? Physical fatigue, boredom and sleepiness seem related to effort. If this theory holds for mental effort, I would like to know how other experiences we associate with strain interact. Exercise seems to improve cognitive performance, for instance, but being physically exhausted usually makes it harder to sustain on mental tasks after.Effort is something we all know intimately, yet the precise causes are often mysterious. I’m excited by this theory since it seems to shed light on something that, perhaps because it is so close to our experience, we have a harder time understanding.

The post A New Understanding of Effort appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 26, 2021

Should You Use Flashcards to Learn?

Flashcards, especially in their digital incarnations, are some of the most powerful learning tools. They can also easily be a complete waste of time.

Powerful, because retrieval and spacing are key to memory. If you want to learn a topic with a lot of stuff to memorize, flashcards will help you do it better than almost anything else. Mnemonics are trendy, but for medium-to-long-term purposes, flashcards are probably better.

It’s also easy to waste your time with flashcards. You can spend a lot of time memorizing something you don’t need to, or fail to memorize the important things you do. Flashcard practice can also be a convenient way to avoid doing the real thing you need to learn. Some subjects may not be amenable to flashcards at all.

Let’s try to untangle these seemingly contradictory views…

In Favor of FlashcardsFlashcards work via simple retrieval practice. You have a question on one side, answer on the other. By trying to recall the answer before looking at the back, you strengthen the memory link between the one and the other in your mind.

Retrieval practice is well known to be one of the most effective studying methods. While flashcard study isn’t the only way to practice retrieval, it can be a convenient one for subjects that are factually dense.

Spaced Repetition Systems (SRS) such as Anki or Supermemo enhance this basic technique by automatically scheduling reviews. The spacing effect, that repeated exposures spread out through time enhance memory, has been known since the dawn of experimental psychology. Once again, there’s clear evidence spacing works.

A common claim of SRS is that they optimally space out reviews. With an exponentially increasing delay between successful reviews, this allows you to keep adding new flashcards without the burden becoming unmanageable. While this review schedule is convenient, the scientific evidence isn’t so clear-cut as to it being better than evenly-spaced reviews.

Flashcards also compare favorably to mnemonics, which is often what is taught in memory-enhancing courses. Mnemonics tend to be somewhat narrower in their applications, and since the rely on the declarative memory system, they may result in less automatic and enduring memories than repeated retrieval practice. (Of course, if you can do both, that’s even better. But if I had to choose where to start I’d go with flashcards first.)

Flashcards have many passionate advocates online, so if you google around a bit for learning methods, you’re likely to stumble across people who have made Anki their go-to tool for learning languages, medicine, math and more.

Flashcard FailuresOkay, if flashcards are so useful, and the two principles on which they’re based (retrieval and spacing) are so well-justified, what’s the problem?

There are a few major traps you can fall into when applying flashcards:

You grab off-the-shelf flashcard decks, rather than make or edit your own.You design the cards badly. This leads to either memorizing useless stuff or failing to learn what you actually care about.Memorization substitutes for understanding.Flashcards substitute for doing real practice.Let’s look at each of these pitfalls briefly.

1. Off-the-Shelf Flashcards

The appeal of a premade flashcard deck is obvious: making a deck takes time and so grabbing one off-the-shelf can save dozens of hours. The downside is less obvious. A lot of premade decks are terrible, and only work with considerable editing.

One resource I used while learning Chinese characters was the Mastering Chinese Character decks. There were a series of ten of these and they benefited from having native audio and images. Plus there were a lot of cards—well over 10,000 in total.

Except the deck had numerous problems. The language was quite formal for beginners, resulting in me learning a lot of not-so-common ways to say things (and thus being misunderstood). There were also a subset of cards that went from single-character pronunciation to the written form. This doesn’t work, because each sound in Mandarin represents multiple characters—是,市,士 are all common characters that are pronounced shì.

I don’t regret using this deck, but it did require a lot of editing (including filtering out the broken cards). Most of the time, however, you won’t be so lucky. The decks you download will end up wasting you more time than making your own.

2. Bad Card Design

There’s a subtle art to designing a good flashcard:

Each question should have one and only one correct answer. (Something violated by my Chinese deck as mentioned.)Questions should either have as little unnecessary context as possible, or redundancy. A vocabulary word alone, or used within a few sentences (each on different cards) are better designs than a single sentence. Why? Because you learn to predict the answer based on the surrounding context even if that won’t be there when you need to use it in real life.Questions should be simple. Complex problem solving isn’t well-suited to flashcards. Better to break apart complex problems into multiple steps, or simply forego flashcards altogether in favor of solving real problems.Questions should be something you actually need. Just because you can memorize something doesn’t mean you should.A sloppy way of making flashcards is simply to copy and paste stuff from your classes into a Q&A format. This can be fast, but it ends up making many cards that end up violating these rules. The result isn’t memory but a mess.

3. Memorization Substituting for Understanding

I used to be a strong opponent of rote memorization. My views now have evolved, as I see that memory and understanding are probably on a continuum rather than distinctly different things. Knowing many facts is often needed for understanding, and so flashcards shouldn’t be seen as the enemy of insight.

Nonetheless, there’s often a tendency to take a difficult problem of understanding and try to replace it with a system of memorization. Difficulty in learning deep programming ideas, for instance, get swapped out by flashcards to memorize syntax. Except syntax is fairly easy to look up and ideas are fairly hard, so this has the priorities exactly backward.

There do seem to be some people who can learn conceptual subjects through flashcards. However, I’m less optimistic that this is a generally good approach. For many deep subjects, solving lots of problems ought to be the first step, with flashcards used to master stubborn details that are often forgotten.

4. Doing Flashcards Instead of the Real Thing

Flashcard fetishization reaches an extreme in language learning circles. I say this being someone who has made decks with tens of thousands of cards.

The logic seems to go like this: languages require a lot of memorization, flashcards are good for remembering things, therefore if I just do a lot of flashcards I’ll be fluent in a language.

The problem with the logic is the word “just”, flashcards are great for memorization. But using a language is much more complex than just spitting out translations. Since actually speaking a language is more effortful than flashcards, typically, they can end up being a fake substitute to the real thing.

My own experience with using flashcards in language learning has varied. I didn’t use them much at all with Spanish, as I found I was able to remember words well enough from real conversations. I used them heavily while learning Mandarin, but always alongside real conversations. My more recent Macedonian project was in-between—I made a much smaller deck of around 2000 cards which was really helpful for vocabulary, but my total time spent on flashcards was a distinct minority of my studying time.

Should You Use Flashcards?If you’ve never used spaced repetition systems before AND you have a memory-intensive subject to learn (language, law, medicine, etc.) the answer is probably yes. You should at least give them a shot because they really are vastly superior to the passive review techniques that students typically use.

If you’ve tried them before and they didn’t seem to appeal to you, chances are you either designed the cards badly or your judgement was correct and other forms of practice might be better. While there’s always a risk of using a tool incorrectly and mistakenly thinking it doesn’t work, there’s also often excessive enthusiasm from devotees of a particular technique.

If you’re a flashcard aficionado, I would go forward, but with caution. Are you doing the real work to develop understanding in the areas that need it? In complex skills like speaking a language or medical diagnosis, are you using flashcards to supplement or substitute the real practice you need to get good?

My feeling about flashcards is similar to my views on most learning methods. They work well when used appropriately. The trick is to have enough self-awareness and understanding of your subject to know what’s appropriate and what’s not.

The post Should You Use Flashcards to Learn? appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 19, 2021

Some Reflections on Being Off Social Media

Last summer, I decided to stop using Twitter. I gave up YouTube as well as part of my own digital declutter in the fall, during the first session of Life of Focus.

Since it’s been several months since I’ve stopped using social media, I thought I would reflect on some of my experiences. It’s possible I might go back to some limited use at some point, but for now the benefits of being off-platform greatly outweigh the costs.

Still, I don’t want this essay to be misconstrued as some kind of permanent commitment. If you’re reading this years later and I’m no longer following this, there’s no contradiction. I merely thought I’d share some of my experiences now, while the transition is still relatively fresh.

Motivations for Going Off-PlatformI should note that while I’m not using social media personally these days, my business definitely does. I’m not typically the person doing the posting, but my team uses most the major platforms to hopefully convert more people to read the weekly newsletter or listen to the podcast.

I’m less antagonistic toward social media than my oft-collaborator Cal Newport. I think they’re potentially a vice, but they can also be really entertaining and have some worthwhile benefits. Thus I’m only speaking from my own experience, rather than offering a universal prescription.

My own impetus to switch off came from two places:

First, the overall level of nastiness on platforms, particularly Twitter. I would often follow people for their academic or entrepreneurial expertise, only to find my feed was mostly full of culture-warring threads. At first I tried to diminish this through careful filters (removing tweets that mentioned “Trump” was a start), but I was beginning to feel a bit like Sisysphus by the end.Second, the additional time wasted beyond the “good” content. This was particularly true of YouTube. There’s a lot of really good content on YouTube, and I had many channels that I loved all their new videos: 3Blue1Brown, Historia Civilis and WW2 in Real Time were a few. But these showed up, at most, a couple times per week. The rest of the time my feed was full of stuff I probably didn’t need to watch.I was also interested just to see what going off social media completely would do for my life. It was a much more positive change than I had expected, as the impulse to check social media declined considerably and I found alternatives to replace my previous information sources.

Off-Platform, Not Off the InternetI still use the internet quite a bit, so my transition wasn’t toward a life of reading books by candlelight. Instead, I feel like my internet usage now is much closer to how it was when I began blogging—curated information sources rather than algorithmic feeds.

RSS remains an underrated technology. I follow a few dozen blogs and their articles let me get the echos of current Twitter discussion, without having to wade into the muck myself. Marginal Revolution is one I like, in particular, given Tyler Cowen’s voracious reading habits. (Feedly is good if you want to start with RSS.)

Much of my previous random YouTube watching time is now on online courses instead. While I have also been reading more as well, there are some times when I’d prefer to watch than read (say if I’m having a quick lunch by myself) and online classes fill the gap.

My phone use is now much more heavily skewed toward reading. These days it’s mostly my Kindle app and The New York Times. I still check my phone quite a bit, but I find that the fact that the news doesn’t refresh nearly so often means that I’m not “sucked in” nearly as much as before.

Recently I found out you can also follow YouTube channels via RSS, so this solves my previous dilemma about what to do with my favorite channels. Now I only get new updates from sources I’m actually subscribed to.

Benefits of Going Off Social MediaThe transition away from social media was a lot easier than I had expected in the long-term. The short-term can be quite difficult because many of the habits to check are strongly reinforced. However, several months out I’m now wondering why I was fussing over it.

This raises, at least in my mind, the value of the argument that social media is a mild kind of addiction or compulsive behavior. If withdrawal seems hard in the short-term, but barely noticeable in the long-term, it seems unlikely to me that our collective social media use is entirely derived from us getting value from the activity.

Initially, a major benefit of cutting social media was reclaiming quite a bit of time. However, as replacement activities such as reading (or more constrained internet use) have filled up some of this, the time gap doesn’t seem salient any more. The opposite feeling—“How did I used to have time for this?”—is what I tend to feel now.

I think the anxiety-lowering effects of going off Twitter are more significant than the time savings. While I enjoyed the intellectual discussions, the overall hostility definitely made me more anxious. The feature of modern social media, where it becomes more appealing the more it makes you miserable, seems like its biggest flaw.

Not all platforms share this problem equally. YouTube and Reddit were largely time-wasters for me, rather than anxiety-provoking. Reddit does seem to have a lot of caustic discussion, but since you can choose which subreddits to follow, you can simply omit those talking about something you don’t care about. However, in the end, I found the intellectual caliber of conversations on Reddit was fairly low.

Why is Twitter smart and nasty, but Reddit is dull and fun? The choice to follow people rather than topics seems pivotal here. Twitter allows you to follow the smartest minds, but you get everything they’re interested in, not just their expertise. Reddit’s upvoting system instead gives a kind of intellectual populism where the majority opinion rules the day, but this tends not to be the most insightful analysis.

My verdict: following blogs via RSS is superior on both counts, even if it required more time to maintain and curate a blogroll.

What are the Downsides?Right now the balance of pros-to-cons of ditching social media is definitely toward the “pro” for me. But I can comment on a few side-effects that I observed and have worked to mitigate:

I did become a little less informed of current events. Part of me reactivating my NYTimes subscription was to counter the fact that I suddenly lost most of my breaking news. I’m somewhat ambivalent as to whether being constantly informed is a good thing, but it is something to note.I have found it harder to stay in contact with some friends. Before I had Twitter friends and some friends who mostly messaged me via Facebook. Because of my absence, I’m probably missing some communication. There may be some costs to this (especially for my business), but I suspect the long-run shift to deeper relationships with people offline is going to more than make up for it.RSS and newsletters need more active management. The advantage of algorithms is that they do all the work for you. They figure out what you like to read and watch and make sure you see it first. If you use RSS or get most of your content via email newsletters, you’re responsible for unsubscribing when the volume gets too high or the content irrelevant. I’ve been doing this for years, so this was easy for me, but it is an important factor to keep in mind.People are now telling me about new social media services like Clubhouse and TikTok. No thank you.

I can’t rule out the possibility that there will be a new service that is worth it for me in the long-run (or existing services remove some of their toxicity). But, I’m doubtful. Not because it would be impossible, but just because it wouldn’t be as popular or profit-generating.

In the end, I’m optimistic about content online. There is a lot of good discussions, entertainment and educational materials and it’s getting better every year. But I think curating our own access to that content is probably better than allowing a company to do it for you.

The post Some Reflections on Being Off Social Media appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 12, 2021

Help Me with My New Project

I’m working on a new writing project, based on some of the ideas I’ve written about in Do the Real Thing, The Hard Way is the Easy Way and the chapter on directness in Ultralearning.

The basic idea is that instead of doing the real thing we need to improve, we often get stuck on fake alternatives. This wastes time, energy and makes us miserable. To fix this we need to choose our goals more carefully, face up to their inherent difficulty and ensure our efforts make direct contact with reality.

Interwoven with all this, I want to expose how many of our faulty plans depend on an incorrect metaphor of how the mind works, demonstrate that apprenticeship is a better model for the results we want than school and argue that the laundry list of goals society expects from us is probably unhelpful. If all goes well, it might wind up as a new book.

What I Need From YouIn keeping with the theme of the project, I don’t want my own research and speculation to disconnect from reality. That reality, of course, is the lives of the people who will one day (hopefully) read it. Thus I’m in the process of gathering examples, feedback, stories and research suggestions from anyone who would like to contribute.

If you have thoughts about the project, feel free to share in the comments, or reach me directly via email.

While I want to keep my request open-ended, here are a few things that would help me a lot, in particular:

Personal stories. If you have a personal experience, either of getting stuck doing something you only later realized was a “fake” effort, or of making a breakthrough by adjusting your approach to make better contact with reality, let me know.Current struggles and difficulties. Maybe you’re struggling, right now, with figuring out what the real thing is, you can’t seem to make progress or find yourself stuck. If you loved (or hated) “Do the Real Thing” or my other articles related to this topic. Why did it resonate with you? What did it make you think of? This will help me clarify the idea, as well as resolve potential confusions early.Of course, if you have any books, journal articles, biographies or other ideas you think might contribute, I’d love to hear them. Before my previous book, I did a similar process of getting examples and suggestions from the audience, and it ended up making a big difference in the final product.

The post Help Me with My New Project appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 5, 2021

Book Recommendation: A World Without Email

As many of the readers here probably know, I’ve been a long-time fan and friend of Cal Newport. We co-instruct two online courses and we’ve shared more conversations than I can count. Cal also coined the term “ultralearning” and pushed me to write my book, so his influence on my career hasn’t exactly been minor.

So of course, I was very excited to hear that his latest book, A World Without Email, had reached the New York Times bestseller list in its first week. I just finished reading my copy and I have to say I think it’s Cal’s best work to date.

Is Email Really So Bad?

Is Email Really So Bad?The title of Cal’s book is provocative. To be honest, when I first heard he was writing a book about eliminating email, I was a little confused. What’s wrong with email?

Heck, if you’re getting this essay delivered via my newsletter, there might be some irony here. I’m sure Cal is also aware of this tension—tens of thousands of readers are also on his email newsletter. Beyond that, Cal and I mostly communicate via email these days, so if the ideal of the book was zero email usage, we’re both failing miserably.

Once you start reading, however, the message of the book is clear. What Cal is against isn’t email per se, but what he terms the “hyperactive hive mind” workflow that it enables. This is the workflow which involves numerous back-and-forth pinging of email in order to do collaborative work. Endemic in big organizations, this workflow is unproductive and it is making us miserable.

Cal shares anonymized data gathered by the time-tracking software RescueTime and it isn’t pretty:

Half of users check communication applications like email or Slack every six minutes or less.The most common average checking time was once every minute.For half the users studied, the longest unbroken period of work was no more than forty minutes, with the most typical longest time being only twenty minutes.More than two thirds of users never experienced an hour without an interruption.For business users, average email volume was 126 messages per day.

Earlier productivity writers, notably Tim Ferriss in his bestselling 4-Hour Work Week, argued we could reduce email’s impact with techniques like batching or sending out autoresponders to inform our colleagues that we were only checking email twice a day.

Cal believes these measures often fail because once your organization has adopted the hyperactive hive mind workflow, it’s hard to opt out. Your boss and peers are also sending emails back and forth frantically, so being the one person who ignores this creates friction.

What we need, then, isn’t just better email habits but totally new workflows for handling our collaborative work. While Cal’s book Deep Work argued for the benefits of depth from a largely individual perspective, A World Without Email could be said to extend this reasoning to the problem of coordinating work across an entire organization.

Knowledge Work Hasn’t Had Its Productivity EpiphanyCoincidentally, prior to reading Cal’s books, I had been engaged in a mini-project of my own to investigate the origins of thinking on productivity. This had me reading big textbooks like Daniel Wren and Arthur Bediean’s The Evolution of Management Thought, and Frederick Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management.

I can see clear parallels between Frederick Taylor and Cal Newport. Both saw their respective working environments as being horridly inefficient. Both saw the problem as stemming from coordination failures—individuals might act out of their own interest, but collectively end up getting much less done than they could ideally. Finally, both suggest the prescription is to research and design better ways of working to get more done with less waste.

Cal downplays his similarity to Taylor for the probable reason that Taylor hasn’t always been viewed fondly through the lens of history. I tend to be of the view that Taylor was unfairly vilified, so I tend to see the comparison more favorably. Still, I think even if you were a critic of Taylor’s time studies of productivity (where he would sit next to factory workers with a stopwatch to find out optimal movements and productivity levels), the critique largely wouldn’t apply to Cal. What’s being suggested isn’t turning us into maximally-efficient automatons, but taming the hive mind so we can actually get our work done in peace.

Via this comparison, however, we can see that Cal sees our current working setup as being akin to the pre-Taylor world of manufacturing. One in which production processes were ad-hoc and disorganized and productivity was abysmal. Following Taylor, Drucker notes, manufacturing productivity increased fifty-fold, so we can see how far Cal thinks we are from the productivity frontier.

Unintended Consequences of TechnologyA recurring theme of A World Without Email is that technology isn’t neutral. Email didn’t just arrive in workplaces as a more efficient way of sending letters. Instead, it radically changed what messages were sent and, ultimately, how we performed our jobs.

This is a theme that runs through Cal’s earlier work, Digital Minimalism and his long-standing critiques of social media. Adding the “Like” button to Facebook was originally intended to declutter comment spaces, preventing redundant “Nice!” or “Cool!” in response to photos. But the consequences were extreme, suddenly allowing the services to provide the steady drip of social approval humans crave.

The problem, as Cal sees it, is that once you decide on email as the primary vehicle for collaborating with coworkers, you unavoidably slip into workflows that involve checking your inbox for new messages every three minutes. Cal’s addition to Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message” might be interpreted as “the technology is the workflow.”

I particularly enjoyed this book because it made much heavier use of Cal’s computer science background. Claude Shannon, information theory, asynchronous communication channels and Nash equilibria are woven into Cal’s arguments. Computer science references aren’t typically what people are looking for in a book like this, but it was nice to see Cal leaning on his academic expertise.

What’s the Solution?Cal’s suggestions are less radical than the title of the book. While Cal avoids making one-size-fits-all recommendations, his general approach is to replace the free-form ad-hoc collaborative style enabled by email with much more structured processes.

Cal writes fondly of tools like Asana and Trello, which can help get tasks off of email and onto more organized project boards. Discussion, then, becomes something you tune into when you’re ready to work on that task, not something that constantly interrupts unrelated work. Programming productivity paradigms like scrum and agile development also feature strongly, as the more disciplined communication habits have already shown dividends there.

The world Cal wants to envision doesn’t seem to do away with email entirely, but rather is one where email isn’t the main tool for getting your work done. That’s a vision I can wholeheartedly endorse.

The post Book Recommendation: A World Without Email appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 29, 2021

Make it Happen! is now open

My course on improving the invisible systems that underpin your goals and motivation is now open:

Make it Happen! is taught over six weeks, via brief daily lessons on psychology, decision-making, goal-setting, habits and more. If you’ve wanted to take a course from me before, this is a good one to start with as the material is easy to stick with and builds a good foundation for any other course you might take.

If you’ve wanted to get better at taking action on the things that matter to you–or even if you want more clarity about what should matter to you–the course might be a good fit.

I’ll be closing registration Friday, April 2nd, at midnight Pacific Time. Be sure to check it out before then!

The post Make it Happen! is now open appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 27, 2021

How to Improve Your Self-Awareness

Over the last week, I’ve been sharing lessons on thinking of motivation as a system. One which, if you master it, can allow you to make more progress on your goals with less struggle.

Key to all of this, of course, is self-awareness. You can’t diagnose a problem if you don’t even know you have one. Similarly, unless you have a good sense of who you are, your strengths, weaknesses, personality and proficiencies, you’ll always struggle to make progress.

Yet no bookstore sells a book about “you”, so how do you develop this kind of insight into yourself?

Inside and Outside ViewsThere are two perspectives worth cultivating for self-knowledge. They dovetail nicely, but tend to come from very different sources.

The first is what I’ll call the “inside” view. This is the kind of self-awareness you get from going through a major breakup, finally figuring out what you want in life or going on a meditation retreat. It’s the kind of wisdom you gain from life experience.

Inside-view self-knowledge is highly personal. It’s experience that tells you how to interpret yourself that only you know. This kind of knowledge also tends to be hard to write down. In fact, its often the tacit self-knowledge that underpins much of our motivation. Our self-efficacy determines our motivation, as it subtly encodes our expectations for success when we strive hard.

The second perspective is the “outside” view. This is the perspective you gain from reading psychology, economics, neuroscience and religion. It’s the kind (I hope) you gain a little of when reading my blog.

The outside view isn’t personal—it’s generic. It doesn’t explain your situation, but it offers ideas to help you see all situations. The value of the outside view is that it, indirectly, aggregates the experience of millions of people. Ultimately, science itself is nothing but a systematized accumulation of experience. This can be evidenced by the root word for “experiment” being the same as experience.

Improving the Inside ViewThe road to wisdom is experience. Unfortunately it’s a road that is often quite narrow. Our personal experience, at best, captures a minuscule fragment of the possible lives we could have lived.

Sometimes, with experience, we get a good accounting of who we are. Years of schooling, for instance, often give us a pretty good idea of how well we do on exams, or how much we like sitting and listening to lectures.

However, this experience can also be deceiving. Just because you failed high-school Spanish doesn’t mean you’re “bad” with languages. You might do just fine if you instead lived in Madrid and used the language as part of your everyday life.

This narrowness of personal experience can be reduced somewhat:

Having a wider range of experiences. Simply trying more stuff is an important ingredient in success since it widens the inside view of self-knowledge you have to build off of. While it can sound somewhat trite to say “try a bunch of things” to someone who is struggling, it very often is the right answer.Document and measure your experiences. We often don’t even take full advantages of the limited experiences we do have. We needlessly repeat past mistakes because we don’t bother to document what went wrong. We fail to build on past successes because we don’t take a careful accounting of what foundation was laid beforehand.Talk to more people. Other people can offer an outside perspective on your inside view. There are studies which show that good friends often understand us much better than we do ourselves. This can be valuable information when making decisions, even if we don’t always want to hear it.Improving the Outside ViewWhile the inside view is rich, yet narrow, the outside view is broad, but often lacking details. The solution to problems of the outside view is to educate yourself more deeply. Learn about motivation, memory and willpower. Read broadly and widely to get a better picture of the human condition.

Science, of course, plays an important role in this self-discovery. Psychology, however flawed, has revealed an enormous amount of truth about human nature. Economics has given me more tools for thinking than I can count. Neuroscience provides mechanism to theory, showing how our personalities function.

But I don’t think limiting the outside view to hard sciences is best. Religion, philosophy and literature all have important contributions to make. Many people have been contributing to the conversation of how best to live for millennia, so it makes sense to read what they have to say.

Merging the Two Views

Merging the Two ViewsSelf-awareness comes from building a richer, more accurate model of yourself. This combines not only theory, but experience.

Having more self-awareness leads, straightforwardly to more success. If you understand how you operate, both as an individual and as a human being generally, you can be more successful with your ambitions.

But the benefit of self-awareness is much deeper than this. Understanding yourself transcends just trying to make more money or have a better job, because it helps you realize why you want to pursue those things in the first place. In some places, this will strengthen your ambitions, as you recognize a deeper purpose to your goals, in other cases it may change what you pursue entirely, leaving some pursuits that you recognize won’t actually make you fulfilled.

The process of cultivating self-knowledge is long, and I would be lying if I said I had figured it all out. But, I think it’s a process worth pursuing deliberately, even if it takes a lifetime.

This lesson was written as the last part in a free, four-part series. If you want to read the other lessons, click here: Lesson 1, Lesson 2 and Lesson 3.

On Monday, I’ll be reopening my course, Make it Happen! for a new session. Delivered via daily lessons over six weeks, this course offers insights to help you make more progress towards the goals you care about.

The post How to Improve Your Self-Awareness appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 25, 2021

Why We Struggle to Motivate Ourselves

In the last lesson, I introduced a simple metaphor for motivation: action always flows downhill. Thanks to the amazing circuitry in our basal ganglia, we take the billions of simultaneously firing neurons in our brain and produce sequential thoughts and actions.

Yet the choice of which action to take isn’t always the one our higher selves would opt for. Our motivational hardwiring is notoriously short-sighted, failing to spur us on for rewards that will take months and years to reach.

In this simplified account, one aspect I didn’t include was why our motivational terrain is what it is. Why do we find some actions harder to take than others? Why, in other words, do we struggle to motivate ourselves?

Push and Pull: Two Forces of MotivationListen to this articleThere are two different kinds of reasons we might fail to motivate ourselves:

Lack of drive. This can be because the object of our goals just isn’t rewarding enough. Sometimes, we even trick ourselves about how genuine our motivation is (more on that later), and thus get “stuck” with goals that fail to inspire, but which we can’t drop to do something better.Pain from progress. Alternatively, there might be something particularly aversive in the way of our progress. This can be fears—as someone who wants to deliver a great speech but suffers from stage fright knows. But more commonly it’s drudgery, effort or boredom. We want to ace the exam, but grinding through problem sets just isn’t a lot of fun.Importantly, it seems that these two factors of motivation can operate somewhat independently. Meaning, we can be in situations where we have few barriers, but relatively lackluster drive, and thus stall out. But, we can also be in situations where our goal is highly compelling, but an equally large pain prevents us from making progress.

Problems of DriveIt might seem paradoxical to talk about having a goal that you’re not really motivated to achieve. After all, if you didn’t really have much desire for the goal, why is it your goal in the first place?

One reason has to do with how motivation is shaped by reinforcement contingencies. In their pioneering work, Richard Ryan and Edward Deci, developed an experiment that contradicted decades of previous research on motivation.

Earlier behaviorist theories of motivation assumed all motivators were additive. If you give someone an extra reason to do something, their motivation ought to increase. This was backed by complicated theories that argued that motivation is simply the expression of past reinforcement. If you take an action, that is because of past reinforcement, end of explanation—consciousness, emotion and goals were unnecessary for understanding.

In his experiment on intrinsic motivation, Deci showed that rewarding someone for an enjoyable activity, say completing fun puzzles, did have the predictable effect on behavior—people did more puzzles.1 But, perversely, it diminished motivation after the experiment was complete. People did fewer puzzles for fun, afterward.

This experiment led the duo to propose self-determination theory as a more sophisticated model for human motivation. This theory says that it isn’t simply the rewards that count—our sense of autonomy over the actions we take matters too.

So what does this mean for a lack of drive? Ryan and Deci explain this elegantly too. In their system, externally motivated behavior operates on a spectrum, from purely instrumental activity we do only to get a particular reward, to all the partially-internalized motivators we feel guilt when we don’t always reach them, to those which are fully authentic and integrated into our personality.

This explains why goals can sometimes fail to motivate. If the impetus for a goal is a socially internalized norm “I need to get good grades” or “I should really exercise daily”, but doesn’t feel entirely self-generated, it can often provide only inconsistent motivation. Essentially, we’ll work at it enough to meet our appearance in the eyes of others, but often fail to pursue it vigorously enough to actually make real progress.

Spotting these pseudo-goals in oneself doesn’t always lead to a perfect solution. However, if you spot that your problem is that the motivation isn’t fully internalized, you can either work to make it more fully autonomous (injecting choice and control back into the domain, selling yourself on your goals, bringing it into alignment with other values) or you can push it back to work on something else.

Problems of PainThe other reason we fail to motivate ourselves is because the pain of taking action can be too great. This may not always be literal pain, but fear, boredom, unpleasantness or drudgery.

As procrastination researcher Piers Steel notes in his literature review, task unpleasantness is one of the biggest associated factors with procrastination.2

While this isn’t earth-shatteringly surprising to realize, it too suggests ways we can improve progress on our goals. One is simply to redesign them to make them less unpleasant. If the problem is that your goal requires going forward with something you really don’t like, maybe you can do something you like more instead?

Another clue to resolving this problem comes from the psychology of phobias. Exposure therapy, in which you expose yourself gently to a fearful stimulus over time has a high effectiveness for reducing fears. To the extent that your aversion to making progress is due to an irrational fear or anxiety, applying a similar method can “ease” you into the work.

While it’s easy to think about pain in the most dramatic terms, it’s often the small pinches and itches that really derail progress. How many people fail to set up retirement accounts because the thought of trying to understand their 401k program makes them feel a bit anxious? How many get stuck in dead-end jobs because the thought of reaching out to talk to a few people in different career spaces feels awkward?

Motivation is a complex and fascinating topic. In Make it Happen!, we spend six weeks discussing motivational strategies for achieving your goals. Success comes from self-awareness. If you can understand the friction points holding you back, you can start to get results a lot faster.

I’ll open registration for a new session of Make it Happen! next week. On Sunday, I’ll share the final lesson in this warm-up series.

The post Why We Struggle to Motivate Ourselves appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 23, 2021

The Neuroscience of Motivation

In the last lesson, I shared why it was important to think about success in terms of systems, not inspiration. This isn’t because motivation isn’t important—rather it’s because motivation is itself a kind of system. If you can understand it, you can change it.

Success as systems may not be so dramatic, but the results speak for themselves. The steady accumulation of wealth, building of fitness and acquisition of skills aren’t going to lead to any Oscar-worthy moments, but the outcome is a better life. Provided, of course, you master the processes that lead to them.

Unfortunately, a major challenge in making progress is that our brains simply aren’t designed for a lot of the long-range goal-setting that’s necessary for success.

How Motivation Works Inside Your BrainInside your head, nestled deep behind your brain’s neocortex is a relatively ancient part of the brain known as the basal ganglia. This little blob of tissue receives inputs from many different cortical regions, including your frontal cortex (thinking, working memory) and motor cortex (physical actions).

The problem the basal ganglia solves is that our brains are massively parallel computing structures. Billions of neurons and trillions of synapses all firing independently. Yet, we need to take one and only one action at a time. Try to sit down while jogging and you’ll probably fall.

How the basal ganglia accomplishes this is with a pattern called the motor loop. Basically, it locks all actions by default. Only when an action gets enough support from dopamine-carrying neurons from the substantia nigra, does it go through. These dopaminergic neurons are trained to be reward-predictors—anticipating which set of actions will lead to the best rewards.

The circuitry guiding our thoughts and actions is exquisitely complicated. I’ve only provided a crude summary. But it does have a big limitation—our motivational impulses are remarkably short-term. As motivational researcher Piers Steel commented in our interview:

A week is actually, motivationally a long, long way off. A couple days, yeah, that’s pretty much it.

Motivation comes with an eye-dropper when you want it, and a firehose at the end. What we want is a nice tall glass of motivation, but we don’t really have that. We have this really messed up system.

In brief, while we have an excellent system for predicting rewards and choosing the best action to take, the system is remarkably short-sighted. Messed up indeed.

Imagine Water Flowing DownhillNeuroscience is fascinating, but it doesn’t always give a visceral sense of the implications of this system. To that end, I’d like to propose a visual metaphor that doesn’t capture the full complexity of the computations going on, but gives a good gist.

Imagine your motivation as water sitting on a hill. The action you take is determine by where the water flows. It doesn’t take a physics doctorate to realize that the direction it flows is wherever the slope is the highest. Water flows downhill.

Now, however, imagine that where you want to go is downhill, except there’s a slight lip of land keeping the water flowing further. What happens in real life is obvious—you get a puddle at the top of your mountain. Even if the water “wants” to flow to the bottom, it can’t get over that little hump.

We can imagine our motivation similarly. We want to be rich, fit, smart and successful, but the action required in the short-term requires some effort—it is motivationally uphill. Compared to other, immediately-rewarding alternatives, our impulse will be to procrastinate. Why work hard today for an uncertain future, when I can get an immediate dopamine hit from watching Netflix?

One solution to this problem is simply to try to tilt the playing field. If your motivation is strong enough, temporarily, you might even be able to do it. I think of those puzzle games where you have to roll a ball bearing through a maze, but you can only do it by tilting the game as a whole.

As a short-term solution this works. But often the little humps of motivation required aren’t one-time, but continuous. Exercising isn’t a single cost, but a small amount of effort every time you go to the gym.

An alternative, then, is to smooth off the bumps. If you can reduce friction to your goal, the behavior you want to flow can be realized with a much smaller tilt.

Another strategy is to dam up the easier paths. Reducing the salience of opportunities when you need to make progress on your goals can make them easier. If the easy escape route is momentarily blocked, you’ll be more likely to flow downhill again.

Even better is to design a new path for your goal. If you can have it more consistently pointed downhill, the water might flow of its own accord, no smoothing or damming required. The person who gets in shape doing an activity they love (dancing, skiing, hiking) they might not need nearly as much motivation to get started.

Designing Better Goals

Designing Better GoalsThe analogy with water is an imperfect one. For one thing, water can only roll down in a few directions. The possible actions you can take in any moment is nearly infinite—thus attention and beliefs also form constraints in that they limit which actions are even being considered at any particular moment.

However, what I hope this idea illustrates is the skill of designing your motivational efforts. If you change the problem from, “how do I motivate myself enough to reach this goal” to, “how can I design the goal so that motivation is automatic” you’ll end up making far more progress.

This is the second part in a four-part lesson series. Click here to read the first part. On Monday, March 29, 2021, I’ll be opening a new session of Make It Happen!, which builds on these ideas over six weeks with daily lessons and a framework for improving the systems you use to achieve results. I hope to see you there!

The post The Neuroscience of Motivation appeared first on Scott H Young.