Scott H. Young's Blog, page 29

April 24, 2020

Macedonian Project Update (Week One)

Last week, I shared my goal to learn my wife’s native language, Macedonian.

Today, I thought I’d give a quick update for anyone following along, as well as some tips in case you’d like to attempt something similar with your spouse or roommate.

How is Learning at Home Different from Travel?

The overall process for learning Macedonian is, in many ways, no different from the one Vat and I used several years ago when we were traveling.

In some ways, the project is much easier. Being at home, in a familiar environment, has fewer unanticipated problems than kick-starting immersion while you’re already on the road.

In Brazil, for instance, Vat and I spent the first two weeks trying to find a place to live. After we got out of a bad AirBnB reservation, we spent our days wandering around the town repeating, “Estamos procurando um apartmento por dois meses.” Needless to say, such travel hiccups cut into studying time.

The major way my current project is harder is simply that I haven’t cut back on work, so my studying is entirely in my free time. It’s not a major setback, but it might stretch out the learning process longer compared to when learning was my full-time obsession.

Thoughts on the Macedonian Language

Macedonian is harder than Spanish, but easier than Chinese. Within that range, it’s closer to Spanish than Chinese for difficulty.

A major challenge I had when beginning with Chinese was simply the fact that each and every word needed to be learned anew. Going from English to most Western European languages gives you a lot of vocabulary for free. Creativity in Spanish is creatividad. Creativity in Chinese is 创造性 (chuàngzàoxìng).

Macedonian certainly has more cognates with English than Chinese does (e.g. креативност [kreativnost] = creativity). But it also has a ton of words that differ which are cognates in the other Romance languages I know.

Grammatically, I’m getting off easy with Macedonian, as it’s largely dropped the complicated Slavic case system. The major grammatical complications I’m dealing with so far are clitics and the fact that most major verbs have two different words depending on aspect.

So far the progress feels more like Spanish than Chinese, so I’m still optimistic about having some reasonable conversations on restricted topics by the end of the month. By then, my wife and I will make a decision of whether we want to continue the immersion another month or take a breather.

Advice to Couples (or Roommates) Attempting the Immersion-at-Home Challenge

It’s been great to hear from several couples who told me they plan to try this. I know that some have started already, and I hope others will try it soon. Having some experience with this No English policy, I thought I’d share some advice:

1. You don’t need to be that good to start.

One reader wrote to me how surprised he was at how much he could communicate, even though his objective ability was quite bad.

I think most people grossly overestimate the linguistic ability needed to start applying the No English Rule. The truth is, you can get by with zero talking in many situations. Google Translate plus a patient partner is more than enough for most situations.

If your feeling is “I don’t think I’m ready for it” I suggest shortening the commitment period to a week. If you can get through the first week without a breakdown, you will be able to get through all the other weeks.

2. It’s as hard on your partner as it is on you.

A mistake is thinking of the project as solely being pressure placed on the learner. After all, you’re the one who needs to absorb all the new information!

But in truth, whomever you are speaking with is also going to have his or her communication interrupted. That person is used to speaking with you and having you understand everything fluently. To suddenly drop that ability is challenging, even if it may not involve learning new words.

I’m fortunate that my wife has been very supportive and helpful. But I also try to take care to not make it needlessly harder for her. The strictness of the No English Rule should be placed on the learner, not the other party. This is, in part, to allow the other person to translate important things, but also to act as a pressure release in case there’s something important to be said and you’re just not understanding it.

3. It helps to study too.

I make a big deal out of immersion being a good learning method. It is. And for most people learning a language, it is often what is missing.

But, once you have direct practice as a foundation, studying the language can be quite helpful in accelerating the process. Grammar study, for instance, is often quite helpful because it’s often quite difficult to deduce the formal rules for speaking in the middle of conversations. Vocabulary acquisition, similarly, can be aided with flashcards to augment the words you pick up as you learn.

Harder languages benefit more from studying. This is because the more difficulty you have juggling everything in a live conversation, the more help you’ll get from doing drills to work on components in isolation. Chinese benefited from studying much more than Spanish, because with the latter I didn’t find it too hard to pick up new words in real situations, whereas speaking Mandarin in the beginning, it was often painful to say even a single sentence and be understood.

Chronic Amnesia for the First Week Experience

I always forget how tricky it is to start speaking a new language, the first week I start speaking it. Having done this six times now, you’d think it would be impossible to forget.

Instead, what happens is that you get consistently better with the language. Eventually it’s pretty easy. Now you can’t remember not being able to speak it reasonably well.

The upside of all this is that, if you can push through the first few weeks, it really does get a lot easier. Even one week into this new, part-time project many aspects of our daily communication have become much more fluent. There’s still a long way to go, but no doubt I’ll soon forget, once again, what it was like not to be able to speak it.

The post Macedonian Project Update (Week One) appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 20, 2020

New Project: Learning My Wife’s Native Language

Recently, I wrote about why now was the time to take on an ultralearning project. I figured I should probably follow my own advice!

My new project is to learn Macedonian, employing a modified version of the No English Rule, Vat and I used several years ago during our language learning trip.

Why Learn Macedonian?

My wife, Zorica, was born in what is now North Macedonia (formerly, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, even more formerly, Yugoslavia). She moved to Canada when she was 14. Although we met in our freshman year of college, we didn’t start dating until after having known each other for over eight years.

When we did start dating, I had just finished a year learning languages, so I was interested in learning Macedonian too. However, my wife is perfectly bilingual, and we already had nearly a decade of speaking to each other in English. So, while I learned a bit here and there, I never got to the stage where having a conversation was possible. Just random phrases here and there.

Like most couples, we continue to talk in the language we’re most familiar, in our case English.

Why Learn Macedonian Now?

I have two motivations that make this project particularly timely.

The first is that my son is now nearly three months old. Raising bilingual children is difficult—even families with two native speakers often have children who aren’t in fluent command of the language. But, if there’s any chance for our son to partake in his linguistic heritage, I’ll need to be able to speak in Macedonian too.

The second reason is that the current worldwide state of self-isolation offers a unique opportunity for immersion at home. Normally, a major problem of doing partial immersion is that if the surrounding environment doesn’t speak the language you want to learn, you’re constantly pushed out of the language you want to learn.

Our friends, for instance, don’t speak Macedonian. Therefore, if my wife and I are with anyone other than her family members, the conversation will need to be in English. It’s not an insurmountable obstacle, but it does make it harder to approach things the way one would do when traveling to the country that speaks it.

Now, however, these social complexities are sharply reduced. Maintaining an in-house No English Rule will be a lot easier to maintain.

How Do I Plan to Learn?

Macedonian also offers a unique challenge because it’s a language without much supporting material. For comparison, Chinese may be hard but it has so many learner resources you’re practically drowning in them.

My approach to learning Macedonian, therefore, is relatively simple:

Near daily iTalki.com tutoring. There are a few tutors for Macedonian, so my hope is to have at least an hour per day talking with someone who is dedicated to helping me out.

Textbook practice. I managed to get a Macedonian textbook a couple years ago in my earlier phase of dabbling with learning it. An hour or so per day of this is my goal, but I may scale it back for more tutoring if I don’t find it helps much.

Flashcard practice. I plan to use Anki to master all the words that come up in my conversations and textbook practice. This should make the vocabulary acquisition process a bit smoother.

Talking with my wife! Of course, the main way I’m hoping to learn is simply by having the No English Rule at home to get more comfortable with daily communication.

I’m going to modify the No English Rule from our trip in the interest of my sanity. Rather than the absolute, strictest form that Vat and I adhered to for most of our voyage, I want to include a few caveats that should make life easier without jeopardizing the overall aims of the project:

Calls outside the house are still okay. While I did maintain calls with my parents in English while I traveled during my yearlong project, I heavily curtailed other calls. I won’t be doing this here, since doing so would needlessly interfere with my work.

Emergency “Time Out” allowed. Switching to an unfamiliar language can put strains on any relationship. It certainly did with Vat and I, and our roommate status was far less intimate. While I want to keep the low stakes conversations within Macedonian, I’m going to be more permissive with emergency time outs to deal with matters of importance, especially those that have to do with our child.

How Far Do I Hope to Get?

In general, I prefer to focus on the effort invested, rather than reaching a specific outcome. The project is only a month long, and my level of immersion is decidedly less than what I had in Spain or China, so realistically I should moderate my expectations.

That said, I have learned some Macedonian before, during my dabbling in the previous five years. I even spent two weeks in North Macedonia visiting my wife’s relatives over a year ago. The result of which is that although I’m far from conversational, I’m also enough above zero that transitioning to full immersion should hopefully be a tad easier.

I would be exceedingly happy if I can get through longer conversations without undue hesitation and dictionary use. However, this description still contains a wide range of underlying abilities, so I would hope to be in the lower intermediate range, even if I can’t quite get to the fluency I had at the end of my time in Spain.

Do Any Couples (or Roommates) Want to Join Us?

When I spoke about this with Zorica, she pointed out how many couples we know where one partner has expressed an interest in learning the language of the other. It’s something that looks easy to the outside (“You spend so much time together, it must be easy to learn the language!”) yet there’s often a lot of resistance.

If anyone here would like to use this opportunity as a push to do a similar project, we’d love to have the company. I’ll try to post weekly updates to the project, although I’ll probably just include them as links in the weekly newsletter to avoid disrupting my normal content.Is there a language you’ve been meaning to learn, but haven’t had the opportunity? Share your story in the comments!

The post New Project: Learning My Wife’s Native Language appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 13, 2020

Being and Time: An Interesting Book You Probably Shouldn’t Read

I just spent the last two months doing a deep dive trying to understand Martin Heidegger’s seminal work, Being and Time.

You probably shouldn’t read it. It’s also one of the most interesting and thought-provoking books I’ve read in the last decade. This post is my attempt to reconcile those two beliefs.

The reasons not to read Being and Time are obvious. The book is only half-finished. Of what was written, the second division is so muddled, that even after taking a companion class with dozens of hours of lectures, I still have no idea how to make sense of it.

Also, Heidegger was a Nazi.

It’s not clear how much Heidegger’s politics influence his writing. Especially around 1927 when this book was published. Still, there’s an undeniable ick factor.

However, even if you do separate Heidegger’s politics from his philosophy, he may have bigger problems. Philosopher Philippe Lemoine describes Heidegger, half-jokingly, as “The only man about whom one can truly say that being a Nazi was the least of his sins.”

Indeed, Heidegger was a major influence of postmodernist thought. You know, that philosophy that says that there is no truth, science isn’t real, all that exists are belief structures made by whomever is in charge. Heidegger didn’t say exactly those things, but his work definitely inspired later postmodern thinkers like Foucault and Derrida.

On top of all that, he’s a terrible writer. It took me a companion course, dozens of articles and books to try to make sense of it from a first reading. I can honestly say reading the Dao De Jing in Chinese was less effortful.

Given all this, why spend two months grinding through the book and why write this now? Sunk-cost fallacy in action, or is there something more?

Interesting Takeaways from a Nearly Unreadable Book

To save you the effort, there were three big ideas I got from Being and Time that were worth the price of admission:

The concept of the background or “world”

A rethinking of what it means to be human

Circles of interpretation, rather than a fundamental ground

Let me try to do my best to explain each…

1. Discovering the World

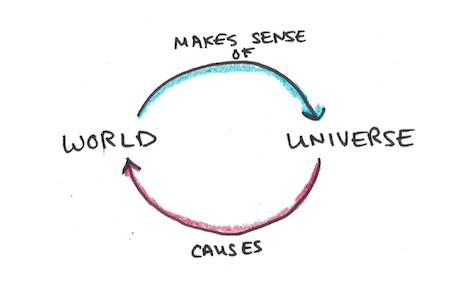

The world is not the universe. The universe is full of atoms and leptons and photons and stuff. It’s what physics studies. The world, in Heidegger jargon, in contrast, is something very human. Indeed, having one may be our defining quality.

You can see what Heidegger means by “world” when you hear expressions like “the business world” or “the world of basketball.” These expressions aren’t pointing to the electrons that make up mergers or lay-ups, but the fact that these domains are backgrounds upon which cultural practices reside.

The “business world” however, is just a part of the broader “world” we live in. The world Heidegger wants to talk about isn’t a sub-world like the world of baseball, nor even the more general world which contains these parts. Indeed, he’s not really interested in describing the contents of our world at all. Instead, he’s interested in the “worldliness of the world” or how worlds are structured, in general.

Okay, that’s a little confusing. Let’s give an example.

Consider a hammer. What is it?

The naive view (in Heidegger’s mind at least) is to see it as a list of properties: a wooden shaft and a metal blob at the end. A slightly more sophisticated view might also include that it’s a tool or that it’s for driving nails, as if these were extra properties of the object like the wood or the metal its made of.

To Heidegger, this is totally wrong. What a hammer is, meaning, how we make sense of it, isn’t as a wooden shaft with a metal blob at the end. No, you make sense of a hammer by hammering with it.

If you have the skill for hammering, the way the hammer “shows up” for you is by being something you don’t really think about at all. Instead you’re thinking about how you need to hammer in those nails into the right spot to join the table leg to the table. To be a hammer, then, is to be something in the periphery of your attention in the context of some larger, meaningful activity.

What’s the big deal then? Well it means that you can’t make sense of a hammer, in the most basic way, without also having nails, lumber, the table you build by hammering, the practice of sitting by tables to eat and so on. In other words, a hammer, as we experience it when hammering, isn’t even a “thing” at all, but part of an interconnected nexus of equipment we know how to use. It’s via this interconnected nexus that we can glimpse at the “worldliness of the world” Heidegger wants to talk about.

Okay, but that’s dumb because obviously when you look at a hammer you can see it’s made of wood and metal. To say that isn’t what a hammer is seems obtuse.

Heidegger would respond that, of course you can also look at the hammer, it’s just that this isn’t the normal way we make sense of hammers. Indeed, he would go further and argue that, in order to just stare at a hammer and “see” that it is “really” metal and wood, we have to strip away all of the context that enables us to skillfully use a hammer.

Heidegger illustrates this stripping away in a multi-step process:

In its most basic sense, the hammer isn’t a thing at all, it’s just an invisible part of the overall task of hammering that you’re working on.

But maybe the hammer is a bit too heavy, this starts to make it stand out. Now you can take notice of it, but still in a way related to the task of hammering. “Too heavy” is still not a property of hammers, but something that exists in this context, for you, at this time. A sledgehammer may be too heavy for building a birdhouse, but not for smashing rocks.

With further reflection “Too heavy” can become “heavy” where you notice that it has weight, independent of your current task. This too is a further decontextualization of the hammer into a separate object.

Finally, if you were a modern thinker, you might say that the hammer has mass, something even more decontextualized and independent.

And there’s nothing wrong with doing this! Indeed, you can learn a lot by removing the “world” from the things you encounter so you can study them scientifically. Our modern world is built on this ability.

But, at the same time, it’s important to recognize that this isn’t our typical starting point. If you start with the raw physical properties of the hammer, Heidegger argues, you couldn’t “build back” to the skills for dealing with it in the world we live in.

What I Like About This Idea

I’m not a philosopher. I don’t really know enough about this to know whether Heidegger’s account undermines Truth or Reality or whatever.

But, I do have an interest in how the mind works, and this seems to be a more compelling account than the traditional picture.

We know, for instance, that over evolutionary time, animals begin with motor reflexes for dealing with their bodies and the outside “world” (although not yet a cultural world at this point). Yet, tradition has largely assumed that reason arrived ex nihilo, as an add-on that is disconnected from those more basic abilities. It seems more plausible, to my decidedly non-expert eyes, that these kinds of skills might end up being the building blocks for abstract reasoning rather than the other way around.

Cognitive scientists have recently been coming to the appreciation that an unconscious runs most of the show for our brains. This unconscious is not a Freudian unconscious—thoughts that could exist in the mind but are simply repressed. Rather it’s an adaptive unconscious that allows our minds to work but does so in a way that could never be conscious. How are you controlling your eyes to read these words right now? How many saccades did you just make? You don’t know, yet those things make vision possible.

Heidegger’s notion of “world” is more cultural than biological, but I don’t see why that division is particularly important. Cultural evolutionary theorists like Joseph Henrich point out that many of our cultural practices are adaptive although we don’t know the reasons for them. Whether nature or culture, I agree with Heidegger that a lot of the “heavy lifting” that makes intelligence possible is being done in this background of activity that is largely invisible to us and which we cannot articulate the reasons for.

2. Rethinking Human Being

What does it mean to be human, deep down? Heidegger has a unique answer to this question. Except instead of using an existing word like “human”, “soul”, “consciousness” or “person” he decides to invent a new one: Dasein.

There’s a justification for this neologism. We have too much philosophical baggage attached to all the old words, Heidegger argues, so it’s impossible to see what he wants to show you if you stick to words infected by the old philosophy. If you want to start a new paradigm, you have to be willing to sound incomprehensible to those still attached to the old one.

Dasein is our way of being, which he also calls existence. (To Heidegger, hammers and quarks don’t exist, only things like us do. This doesn’t mean what you think it does. It’s just him redefining the word “existence” to apply to only this narrow sense. Yeah, I know…)

Our being, in essence, according to Heidegger, isn’t a rational animal, immortal soul, stream of consciousness or any of the other previous interpretations. Rather we are, at the base level, self-interpreting. We’re the being that makes sense of other beings, which importantly includes ourselves.

To be a human being, then, is to take some stance on what it means to exist. This is not a self-conscious identity. Indeed, the stance we take may be inarticulable, so it’s not as if saying to yourself, “I’m a father” or “I’m a video game addict” is what makes you human. Rather, it’s all the invisible practices that you’re so immersed in that they’re effectively invisible that allow you to make sense of yourself and be something unique.

This definition, that we’re essentially self-interpretation, reminds me of Douglas Hofstadter’s book, Godel, Escher, Bach. In GEB, Hofstadter argues that we are “strange loops.” Like the staircases in MC Escher drawings that continually go up, but somehow loop back on themselves, we are the things which, by our very constitution take a stance on the thing that takes stances.

Heidegger, however, takes this definition further. Combined with his definition of world, he redefines us once again as being-in-the-world. That “in” is supposed to mean more like “interaction” than “inside.” In this view, we’re not separate minds isolated from an external world, but inseparable from the world we deal with.

If you haven’t lost track of all of our redefinitions at this point (Dasein, existence, being-in-the-world), then at this point you find something rather original. The modern view is that we are subjects who look over objects, streams of consciousness, res cogitans or something similar. Being-in-the-world, in contrast says that while private experiences are possible they are not the default. To use Hubert Dreyfus’s explanation, our default way of being is to be “empty heads towards one single, self-evident world.”

Much of philosophy has worked itself into knots about how we can know things about the world, how we can ever really agree that we’re having the same inner experiences as other people, maybe we’re all living in the Matrix and this world isn’t real, etc..

Heidegger just decides to flip the problem around. If our basic state of nature is that we live in a shared world, then the problem of how we can agree on things is dissolved away. When you and I are looking at the same picture, we’re not each representing separate little mini-pictures inside our heads and struggling to compare them. We’re actually looking at the same picture.

Of course, in flipping the problem, this view of us as being-in-the-world creates new problems just as it dissolves old ones. If we inhabit shared worlds, how do we account for the fact that people have different knowledge of things, or that they can have false beliefs? If our basic existence is a shared, public world, what about dreams, the quintessentially private experience?

What I Like About This Idea

Heidegger’s concept of “world” seemed obviously true to me, once it had been spelled out. This concept of being-in-the-world doesn’t have the same obviousness, but it may be a fruitful paradigm, even if some of the problems aren’t worked out.

One thing I like about this idea is that it seems to correspond with our psychological development. Children start out as empty heads turned toward the world, but around the age of 3 or 4, they start to gain the ability to recognize that other people might have different beliefs than they do. This “theory of other minds” has been traditionally presented as a discovery, as if children were inherently solipsistic until they discover that other people actually exist.

But there’s another way to frame this story. What if being-in-the-world is simply more basic than having private experiences? Like the example with hammering being more basic than just staring at a hammer, it may feel like private experiences are more basic than public ones, but this might just be a bias from traditional accounts of philosophy.

Hubert Dreyfus gives some telling anecdotes to suggest our view of the primacy of private experience may be a modern invention. In Augustine’s Confessions, he recounts how people from far around would come to see Ambrose, the bishop of Milan. Why? Because he had this strange ability to read books without having his lips moving.

Similarly, Dreyfus recounts Homer’s Odyssey, where during a banquet the hero, Odysseus, is cited for his incredible ability to “weep inwardly” while having dry eyes. Apparently, in those days, the idea of having a private emotion was seen as a mark of extraordinary ability.

I suspect there is truth to this. Although we can all think of prominent examples when people lack knowledge we have, these might be “correctives” to a more basic sense that we all live in the same world. Especially when we take the concept of world at its broadest level, there are uncountably many “facts” about the world that we never even articulate, so deeply do we believe that they really are “there” in the world.

In this account, it’s not that children suddenly learn that everyone has a separate, isolated mind that contains totally different contents than one’s own, but that there are special edge cases where the normal assumption of a shared world breaks down and requires corrections.

Isn’t the idea of a shared world unphysical?

I think it’s important to point out that the idea of a shared world isn’t the same as saying a shared brain or consciousness. While it’s obvious to me that the brain is the source of all of the phenomena I’ve described so far, and thus must be processed by each individual human, that doesn’t mean seeing ourselves as possessing separate “copies” of the entire world inside our heads necessarily makes sense.

To use an analogy that isn’t metaphysical, think of torrenting files. In those cases, there is no central server or “global consciousness” holding everything altogether. But, at the same time, the entire file may not actually be present on any one person’s computer. All that’s necessary is a protocol for sharing and distributing it so that different people agree on the file contents.

Alternatively, there may be a sense that we have a shared world because the way our brain works is not by storing a copy of the world, but by using the actually existing shared environment to make decisions. You can catch a pop-fly by running to maintain a certain angle between you and the ball. This doesn’t require calculating the ball’s trajectory, but utilizing the fact that the ball has a trajectory in the environment to do the calculation for you. The difficulty we often have with running in dreams, may be a similar example, as kinesthetic feedback from the ground is normally needed to keep a smooth gait.

Thus it’s plausible that we live in a shared world, either agreed upon via an unconscious protocol, or through direct reference to the environment itself. The “theory of mind” that children gain, would then be the theory for spotting where this typical protocol for living in a shared world breaks down, and correcting the more basic understanding.

I’m not making any claims of having an algorithm worked out here, just to say that it doesn’t seem obviously unphysical to me that this might be our more basic makeup.

Dreams seem harder to reconcile with this, and private imagination in general. But I don’t think it’s hard to argue that dreams are impoverished relative to the actual world we live in. Maybe that’s the best argument against the idea that the world is purely subjective: that our dreams are pale visions of the world we experience when we’re awake.

3. The Hermeneutic Circle (and the Groundlessness of Philosophy)

Now we arrive at a difficult point. Much of philosophy has been preoccupied with how we can really know things for certain. How can we ground our knowledge on something that is beyond doubt? Medievals used to do this through appeals to God. Moderns have done this through appeals to Reason or Science.

However, if you follow Heidegger in believing that all these invisible skills and practices underpin our ability to do seemingly more basic things like just looking at stuff or thinking about things, then you get in a trap. The skills you have are far from a perfectly solid ground to rest your conclusions on. After all, different people, different cultures, different times have had different practices—so how could you possibly come up with the one final, indubitable Truth?

Heidegger argues that the only way forward is to do hermeneutics. Hermeneutics is the study of interpretation, usually applied to texts. The idea is that, if you want to understand Moby Dick, you have to start with some interpretation of what it’s about. (Say that this guy really hates that whale.) As you dig deeper, you may end up finding out that that initial understanding was flawed, or even completely contrary to where you started. (That the whale is actually man’s search for God.) But you’re always starting with something. There’s no way to go to the ground truth of What Moby Dick Really Is About , since you’re always in some partial stage of interpretation, given what meanings you’ve already started with.

, since you’re always in some partial stage of interpretation, given what meanings you’ve already started with.

This observation, that philosophy is fundamentally ungroundable, is seen as a major flaw for some. Doesn’t this imply full-blown cultural relativism? That truth is just a social convention, rather than anything deeper?

Again, I’m not good enough at philosophy to judge. It’s at least unclear to me whether Heidegger was an anti-realist in the way such beliefs would seem to demand. Heidegger makes a big issue out of the fact that beings do not depend on being, suggesting that the entities that exist in the world are, in a certain sense, independent of our intelligibility of them. This would imply that there really is a causal underpinning of the universe that doesn’t care what we think about it, and thus a proper object of scientific study.

Heidegger’s hermeneutic circle starts and stops with phenomenology. But to me, this feels like too narrow a way to think about the world. While it is true that we have to start somewhere, even if that’s totally wrong, when understanding the universe, I don’t see why that circle can’t encompass physics, biology, psychology, economics and more.

If we expand this circle wide enough, I think we can start to see how more “basic” studies start to look more advanced. Physics, after all, is the study of the most basic things in the universe. But, at the same time, the physics department in a university is made of some of the most complex things in the universe: human brains doing physics. To understand what it means to “do physics” requires understanding psychology, neuroscience, biology… back down to physics again. A circle.

I tend to think people make too big a deal about this kind of ungroundedness. Yes, it does mean that we can never be certain we have found the right answer. But I don’t see that this implies the opposite worry—that everything is totally relative and arbitrary.

Certainly the causal properties of the universe influence the beliefs and practices we form. Thus I don’t see why we can’t simultaneously admit that science is based on a specific set of cultural practices (publishing papers, weighing evidence, deciding what makes a “good” experiment, etc.) but not also see that these practices fit together with the thing they study. A hammer may not be understood, in its most basic way, as just a blob of metal on a wooden shaft. But a hammer made of Jello couldn’t work at all. Science seems constrained by the universe, even if it does require human minds with cultures to implement.

How to Avoid Reading Being and Time (If You Wanted to Know More)

Some of the ideas that Heidegger makes a big deal out about, I either can’t make sense of or didn’t seem compelling to me. The book is called Being and Time, for instance, because apparently time is the key to understanding being. I didn’t get it. Don’t misconstrue my cherry-picking interesting ideas for a blanket endorsement of Heidegger. Your mileage may vary.

If you’re interested in learning more, I still don’t recommend reading the actual book unless you’re willing to grind through it for a couple of months. Instead, I recommend the following:

Being-in-the-World. Documentary about Heidegger’s philosophy. It captures a lot of the ideas (including some later Heidegger stuff) which I didn’t include here.

Being-in-the-World. This book is Hubert Dreyfus’s original exegesis (and also the reason for the title of the documentary). This goes into a lot more philosophical depth than the documentary, if you wanted to really know more, but still shields you from the worst of Heidegger’s writing.

Being and Time – Division I. This is a full class, originally taught at Berkeley, by Dreyfus, about Heidegger. This was my main companion for understanding the book, although it doesn’t cover the later existentialist stuff in Division II. Dreyfus does have a class on that too, but since he also can’t seem to make sense of that part of the book, I didn’t find it helpful.

Stanford’s Wiki on Heidegger. Probably the best short description of Heidegger’s thoughts, which also includes his later ideas about art, styles of being, technology and culture.

One takeaway from this project is that I should probably read more philosophy. Maybe if I do, I’ll end up taking back a lot of the things I agreed with so far. But thinking is always a work-in-progress, so I’m content to share what I find along the way.

The post Being and Time: An Interesting Book You Probably Shouldn’t Read appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 6, 2020

Rapid Learner 2.0 is Now Open

Rapid Learner, my six week course designed to make you a better student, professional and lifelong learner is now open.

I’ve made major updates to this edition of the course, including 20+ newly recorded lessons, deep dives, walkthroughs and more. For the first time, I’m also experimenting with a (limited) option which includes private coaching. Be sure to check out the page above for details.

Registration will remain open until Friday, April 10th at midnight Pacific Time. If you have any questions at all about joining, be sure to email me!

The post Rapid Learner 2.0 is Now Open appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 5, 2020

Is Your Path a Staircase or a Circle?

Tomorrow I’m going to be opening a new version of Rapid Learner—with 20+ new lessons, deep dives, options for personal coaching and more. If you’ve been following my work on learning and are ready to take things to the next level, this is your opportunity.

I’ve already shared a few key ideas this week. I wrote about why now is the perfect time to start an ultralearning project. I explained common mistakes people make when picking projects (and how to avoid them). Finally, I introduced the concept of a practice loop, and gave suggestions for perfecting yours.

Today, I want to discuss the impact learning has on your whole life.

Staircase or Circle: You Decide

Listen to this article

We all have ideas for things we want to improve. Maybe you want to learn about investing so you can manage your finances better. Maybe you want to learn about how to build good fitness habits, so you can stay in shape. Maybe you want to build skills for your career, learn new subjects or otherwise become a smarter, better version of yourself.

Unfortunately, for a lot of people, their process of improvement looks like this:

They start out with some ideas. They get excited for a week or two. Maybe they even take some early steps into doing something about it. But, their enthusiasm wanes and eventually their project gets abandoned and they’re right back where they started. Their path is a circle.

On the other hand you have people whose path of improvement looks like this:

They get an idea. Instead of daydreaming, they construct a specific, short-term project. Once they accomplish that, they move on to a new idea and a new project. Each project builds on the last, expanding options. Before long, they’re getting opportunities to do things they couldn’t have imagined at the start. Their path is a staircase.

What Defines the Shape of Your Path?

I think there’s a few factors that determine whether you make consistent progress or spin around in circles:

1. Do you focus on one thing at a time to completion?

Juggling multiple goals and interests is fine when those projects are easy. But distracted focus doesn’t work when projects are hard. Unfortunately, climbing stairs is hard work.

The person who does one project at a time, finishing them before starting the next, will make infinitely more progress than the person who does dozens of projects at a time, but never really makes much progress on any of them.

2. Do you have the right method to make it work?

Doing something that’s outside the orbit of your usual routine requires not just commitment, but new methods. Almost by definition, if you already knew how to do it, you’d have done it already.

The people I most admire for constant climbing are always acquiring new methods. They get these from reading books, taking courses, conversations with people who know more and experimentation on their own. Thinking you already know the best way guarantees you can’t find a better one.

3. Do you enjoy actualization more than possibility?

Daydreaming can be fun. It’s certainly a lot less work. For some, the idea of a goal is always more exciting than actually reaching it.

There’s some truth to this. When you achieve most goals, you often find that they don’t seem as special as when you first imagined them. The magic trick feels less magical, once you know how it’s done.

But there’s a different kind of satisfaction that comes from reaching goals. The more you can attune your life to the joys of doing and actualizing, over daydreaming and philosophizing, the more solid your life’s foundation will become.

Today’s Homework

As a final exercise, I want you to think of all the projects and ideas you’ve had in the last couple of years to work on. Then I want you to write down how many of those you actually completed.

No need to share this one, this exercise is just for you.

My purpose in this exercise isn’t to argue you should actualize every notion you’ve ever had. That’s impossible. If you’re doing it right, the number of completed projects will always be a lot less than your possible ideas.

Instead, I want to note how often we not only do far less than we imagine we would, we often do far less than we reasonably could. This isn’t to guilt or shame, but to be optimistic about our future potential. Even a small bump in your completed projects can accumulate into a mountain over time. Start building yours today.

The post Is Your Path a Staircase or a Circle? appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 3, 2020

Designing the Perfect Practice Loop

All this week I’ve been sharing lessons to prepare for a new session of Rapid Learner. Next Monday, I’m going to be reopening the course which has been revamped with over twenty new and updated lessons.

Previously, I wrote about why now is the perfect time to start an ultralearning project, and gave three different paths you can take to come up with ideas. I also shared pitfalls people make in choosing their project, particularly the peril of indirectness.

Today I want to get into the weeds and talk about a useful concept to think about learning any skill, whether it’s math, art, languages or business: practice loops.

What is a Practice Loop?

Listen to this article

A practice loop is an activity, or group of activities, you repeat over and over again while learning something. For example:

Basketball – Playing games is a practice loop. But so are layup, shooting and passing drills.

Painting – Each painting you make.

Programming – Each program you complete.

Physics – Each problem you solve.

Business – Each product/feature you launch.

Languages – Conversations, flashcards, grammar exercises are all loops.

The concept can get a little fuzzy. Many loops aren’t actually straightforward repetitions. You may never write the same essay twice. In this case, the loop isn’t writing a particular essay, but the overall process for writing essays.

Similarly, each thing you learn may have more than one loop. Drills are smaller loops that isolate parts of what you do in a bigger loop. A programmer may have a loop for a whole software project, a loop for each module or feature, and smaller loops for little bits of code she writes.

Despite these wrinkles, I think keeping the overall picture of loops in mind is very helpful, since it can help you think about what goes into your practice efforts and how to make them more efficient.

Designing Your Practice Loop

The first step is to figure out what your loops are. What are the activities you repeat over and over again when learning a subject. You can’t improve a loop you’re not even aware you have!

The next step is to analyze the loop for different parts to see whether you might be able to make improvements. Faster learning is often the result of identifying a weakness in your current loop and reinforcing it so that it is sturdier.

Here are a few places to look:

1. Match: Does my loop match the skill or subskill I’m trying to improve?

The first place is to check whether the loop you’re engaging in really is matching the skill you need to perform in a real situation.

A vocabulary drill that is aimed for giving you words to speak in a real conversation, but only has you recognize words by their spelling is a poor match. The result may be that you’ll probably occasionally recognize the words in print, but you may not be able to speak them aloud in many situations.

A first place to improve your loop, therefore, is to look for ways you can match it closer to the demands of a real situation.

2. Feedback: Can I get better, more accurate feedback after each iteration?

Always look at the feedback you get in each repetition. What could be made more accurate? What information could you get that is currently missing?

My portrait drawing challenge was largely inspired by realizing that you can get much better feedback drawing from a picture if you superimpose a transparent version of the original image on top of your work. That gives way more information about what kinds of mistakes you’re making than simple guesswork.

Some other ideas:

Public speaking? Dance? Sports? Could you videotape yourself performing the skill to be able to look for mistakes later, rather than when your attention is otherwise occupied?

Solving math problems with solutions can accelerate your progress since you can easily correct conceptual mistakes.

Work in front of an audience? Having a blog (versus writing in private) adds external feedback to each essay you write.

3. Ideal: Do I understand the process I’m trying to loop?

A mistake many make is thinking that most of the improvement in performance comes from simply doing the same thing over and over again until it is perfect. Although this is true (and perhaps necessary) for some loops, this overlooks an important fact: sometimes a different process altogether will create better results. In such a situation, repeating an inefficient technique won’t make you a master, but simply ingrain bad habits.

Try to make explicit what your ideal process ought to look like. Then ask yourself if you’re reaching this ideal when you perform the skill, or are you taking short-cuts around the method you know will work best? If it’s the latter, adjusting your loop to consciously emulate an ideal is good practice.

4. Speed: How many loops can I do per hour? Per month?

Assuming you are hitting your ideal, the next place to look for optimizations is to simply stop wasting time and do more of the loops you need to do. Many of my projects followed a similar pattern: identify a core loop that works for learning the subject, then be relentless about optimizing time to get the most iterations in possible.

So, if you’ve decided that doing flashcards is important for a subject, then if you can maintain one hundred new flashcards per day plus reviews, you’ll be learning faster than if you only do ten. If you’re painting one piece a day you’ll progress faster than if you’re doing one a month. If you’re speaking twice a week, you’ll get better than if you’re speaking twice a year.

There’s a risk here of getting speed without getting an ideal process. Doing a bad loop faster doesn’t help. But once you’ve got a good enough loop, the obvious strategy is to simply do as much as you can.

Today’s Homework

The best way to learn is to do, not just sit and read. Try this quick exercise:

Write in the comments what your current practice loop is for something you’re learning now.

Give one suggestion for how you might improve the loop, based on what I’ve suggested above.

In truth, optimizing your practice loop depends on a lot more than the basic ideas I was able to sketch here. In Rapid Learner, I devote an entire week to covering practice, with several lessons (including a 2+ hour deep dive specifically devoted to spaced repetition systems). Next week, I’ll be opening the course for a new session.

In the next lesson, I want to zoom out a little and consider not just success with a single learning project, but how that builds into continual improvement throughout your whole life.

The post Designing the Perfect Practice Loop appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 1, 2020

How to Build Skills That Matter

In times of difficulty, you want your efforts to matter. Not just to pass the time, but to build something that endures.

Recently, I shared why I think now is the best time to start an ultralearning project. Not in spite of the anxious time we’re living in, but because of it. Taking resolute action through uncertainty allows you to improve the things you can actually control, instead of breaking under what you cannot.

Today, I’d like to continue that theme and talk about how you can structure your efforts so that what you are learning actually matters.

Side note: Months ago, my team and I started work on a new edition of Rapid Learner, with 20+ new and updated lessons. Next week we’ll be holding a new session. Past students can access the new material for free.

The Peril of Indirect Projects

Listen to this article

In my book, Ultralearning, I cover the research on transfer. It’s not pretty. Countless studies confirm the fact that much of what we set out to learn doesn’t actually transfer to the situations we need it. Consider just a few cases:

In one study, students who took high-school psychology courses didn’t end up doing better at college level psychology.

In another, those who had studied economics didn’t do better at questions of economic reasoning than those who hadn’t.

Psychologist Howard Gardner even adds that there is now an “overwhelming body of educational research” that “students who receive honor grades in college-level physics courses are frequently unable to solve basic problems and questions encountered in a form slightly different from that on which they have been formally instructed and tested.”

All of this research explains why many of us feel like we got little out of school. Transfer—meaning the ability to actually apply and use what you learn—is a lot more illusive than it first appears.

This applies to school, certainly. But also to your own learning efforts. Choose poorly and many of your projects may not matter at all.

How Can You Avoid This Trap?

I suggest a good rule of thumb for any learning project is that the project should involve something you DO or MAKE not just something you LEARN. That may sound a little vague, so let me gives some examples:

Don’t just learn French, aim to have conversations with people.

Don’t just read a book on JavaScript, build a functioning website.

Don’t just watch lectures, do practice problems from the exam.

Don’t just read philosophy, write an essay or discuss it with someone else.

This rule won’t guarantee you’ll avoid transfer issues. But it prevents some of the more severe versions of the problem.

More Tips on Designing Your First Project

Here are a few other good rules of thumb you can follow when designing your project:

1. Inputs over outputs.

A mistake I see people make (and I’ve made myself), is to think that the important thing is picking an especially ambitious target. While it’s true that a big goal can inspire, it can also frustrate.

A better approach is to focus on how you’ll learn differently. My language learning project is a good example here: I focused not on reaching a predefined fluency goal, but of sticking to a method I knew would make progress quickly. My MIT Challenge is a counter-example, but even there I spent months planning my strategy so the choice to do it in one year wasn’t arbitrary but carefully calculated.

2. Pick your quitting time in advance.

Don’t start projects without clearly defined endpoints. For a new project, one month is a good endpoint, but two or three months also work if you have something specific in mind.

Why? Because committing to an indefinite timetable means you’ll give up as soon as things get tough. It’s much easier to say to yourself, I’m going to stick with this for one month no matter what, even if it feels too hard or something else feels more interesting.

3. Put practice first.

Some topics will require a lot of reading. Nobody got good at history, law or philosophy without first reading a lot of books. That’s okay.

But, regardless of how much reading is required, mentally give yourself priority to the practice you intend to do. Practice is the most important ingredient in building real skills, and yet it’s the easiest to pass over because it’s more difficult and often feels optional.

If you think of your project first in terms of the practice you’ll do, then reading/lectures/videos become the things you need to do first in order to get to the practice. Adopt this mindset and you’ll be less likely to engage in passive strategies that are less effective.

Today’s Homework

If you’re interested in doing something and not just reading about it, here’s what you need to do today:

Write in the comments what you want to learn this month.

Be sure to frame it in terms of something you want to DO or MAKE, not just LEARN.

(If you’re a student, passing an exam counts too.)

That’s it for today. On Friday, I’ll have a new lesson where I’m going to introduce the concept of a practice loop and show you how you can design yours. Next Monday, I’m going to hold a new session of Rapid Learner with brand new content for those who want to go further.

The post How to Build Skills That Matter appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 30, 2020

Now is the Perfect Time to Start an Ultralearning Project

When I published Ultralearning last August, I had no idea how the world would have changed six months later. Self-directed learning from home has become a requirement for millions, not just a quirky pastime for a few.

Yet I understand if getting excited about learning seems far from your mind right now. These are scary times. Both our physical and economic health are in danger, and it can often feel like there’s nothing you can do but sit and panic-scroll your newsfeed all day.

There’s no shame in being worried. I am too. But in tough times, it is how we choose to respond to our worries that will define us as people in the years to come. Did we dissolve into panic, or did we rise up and do something constructive?

Now is the time to learn.

No, you can’t control what will happen to the world around you, but you can make yourself a better person, more equipped for the road ahead. Investing in learning something deeply is more valuable now than ever:

Learning makes you a more informed citizen. Misinformation is multiplying. The antidote is to dig deeper and understand the forces impacting your life, not surrender to the opinions of others.

Learning prepares you for economic impacts. A rising tide lifts all boats. But a falling tide shows you which ships were seaworthy. Build skills that will weather the storm.

Learning transforms anxiety into resolute action. To let what you cannot control take up space in your mind doesn’t just weaken you, it makes you miserable. Investing in yourself allows you to cultivate mental freedom along with mastery.

There’s never been a better time in your life to vigorously pursue a skill or subject that matters to you.

How to Figure Out What Matters

Listen to this article

There are three roads you can take to choosing a theme for an ultralearning project:

The road of excitement

The road of necessity

The road of foundations

There’s no “correct” path. Yet if you understand the three paths, you can more easily forge ahead. Let’s examine each of them:

1. The Road of Excitement

Our emotions have a deeper intelligence. Excitement isn’t just an irrational impulse. Rather, it’s a sophisticated pattern-matching algorithm cultivated over years of experience. When you feel excited about something that’s those algorithms telling your conscious mind: this is an important opportunity.

I usually start with the road of excitement whenever I’m considering new projects. If there’s an idea I just can’t get out of my head, that’s a sign that there’s something worth looking into more deeply, even if I can’t explain why.

The difficulty with this path is that sometimes you aren’t obsessed about something yet. Maybe you have too many things you’re excited about and can’t pick. What then?

2. The Road of Necessity

The second path for choosing what to learn is to focus on things that you need to know to make your life better. This includes skills for your job, classes you need to pass, certifications you ought to obtain or even the knowledge to understand what is happening in the world.

Necessity may not always arouse excitement, but it can create a stable path forward into developing skills that matter. While excitement can sometimes be fleeting, the things that matter today will likely matter long into the future, and so you’re on more stable footing.

The key is to transmute necessity into obsession. Crafting the right project (more on that soon) can even make a relatively “boring” topic into something you find deeply interesting.

3. The Road of Foundations

What if you still don’t know what to learn? Maybe you don’t have a single thing that excites you to the point of obsession. Maybe you don’t know what you need to learn. What then?

The road of foundations looks at the question of learning from the broadest view. What skills and knowledge, if I acquired them today, would create the best foundation for learning more skills and knowledge in the future?

For instance, you might decide to understand the core subjects that underlie your profession in more detail. A programmer might really get into algorithms. An architect might really dig into design theory. An entrepreneur might try to really understand business strategy.

Foundations matter for your personal life as well: you may recognize that deeply understanding habits, emotions, beliefs or goal-setting is going to be pivotal for you to make progress elsewhere.

Create a solid enough foundation and you can build as high as you’d like.

New Session of Rapid Learner

Months before the world went topsy-turvy, my team and I had spend hundreds of hours creating a major expansion and update to my six-week learning course, Rapid Learner. We’re continuing forward with opening a new session next week.

Any past student of Rapid Learner can access the new material for no extra charge. If you had gotten the course previously, now is the perfect time to take it alongside a new learning project.

During this week, I’m going to be providing some of the best lessons from the course, entirely for free. But I don’t want this to be a passive exercise. Just reading an email isn’t going to make a material difference to your life and well-being. Action is required.

In that spirit, here’s a simple homework assignment to get you started:

Decide, right now, what is one thing you could learn during the next month. If you’re stuck, consider the three roads mentioned earlier to find something exciting, useful and important.

Write down what you want to learn. By sharing your intentions publicly you can also see what other people are working on, and even discuss your ideas in the comments.

On Wednesday, I’m going to write another lesson illustrating one of the biggest mistakes people make in a new learning effort and how you can avoid falling into that trap. Making the right decisions in the planning phase can save hundreds of hours and countless headaches later.

The post Now is the Perfect Time to Start an Ultralearning Project appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 23, 2020

What are the Core Ideas of Self-Improvement?

In any field, there are a few ideas that are core to understanding everything else. Biology makes little sense without evolution. Physics without symmetries and conservation laws is baffling. All mathematics can be built out of sets.

Self-improvement isn’t usually regarded as an intellectual field. It’s mostly an assortment of various gurus and pundits’ suggestions on how you ought to be more successful, happier or wise. Thus it might seem like self-improvement doesn’t really have core ideas at all—just opinions.

However, I think there are some common themes to the art of living better. These ideas are pervasive, coming up again and again. Even in the writing of people who take a stand against them, their prevalence still requires that they be acknowledged.

The Core Ideas

1. Habits

Nearly all forms of self-improvement first require that you change your behavior. Unless the improvement you’re after is purely mental, you’re going to have to actually do something first.

Habits, then, form a central idea in behavior change. Being able to make certain behaviors automatic (or at least, more automatic) is going to help tremendously with any change you might want to make. To get fit you need to have a habit of eating well and exercising. To get rich you need a habit of saving and investing. To have loving relationships you need good habits of communication.

Not only are habits central to self-improvement, but they’re also one of the best studied aspects of psychology. We have countless studies showing how the impact of association, rewards, punishments and contextual cues will have impacts on behavior.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into habits, I recommend:

My best articles on habit changing

Atomic Habits by James Clear

The Power of Habits by Charles Duhigg

Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard by Dan & Chip Heath

2. Goal-Setting

How can you reach a destination if you don’t first know what it is? Goal-setting not only involves deciding what you want, but also planning how you should get there. It’s a common theme, even if many people disagree about which aspects are most important.

Goal-setting has also been studied by psychological research and generally found to be helpful. However, it also seems clear that just having the idea of what you want to achieve usually isn’t enough (although it may be a necessary start). Thus, goal-setting on its own needs to be paired with plans, systems or habits if it is going to be successful.

A good heuristic for goal-setting is that they should be SMART (specific, measureable, attainable, relevant and time-bound). Implementation intentions, formulated as IF… THEN… plans tend to work better than just focusing on an outcome on its own. Planning fallacies also need to be watched for as many goal-setting efforts can be overly optimistic.

Some view the disadvantages of explicit goal-setting to outweigh the benefits. These people either argue for being entirely process oriented and ignoring outcomes, or simply negate the value of achievement itself in favor of different values.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into goal-setting, I recommend:

My best articles on goal-setting

Goals! by Brian Tracy

The ONE Thing by Gary Keller

My course Make it Happen!

3. Systems

Systems are tools that structure your behavior and decision with formal rules. A productivity system is one type of system—in this case aimed at helping you get work done by organizing the things that need doing and telling you when to do them. Other systems exist for helping make decisions, managing knowledge or organizing your approach to specific domains of life.

The opposite of systems is an intuition-based or informal approach. What systems often encourage is creating explicit rules or guidelines which will discourage some tendencies you’d like to avoid. Getting Things Done, for instance, is a famous productivity system based on avoiding the tendency to forget what you need to do.

Systems are often built off of concepts of scientific management and organizational theory, but applied to one’s personal life. Thus business concepts like standard operating procedures, quarterly reviews and key performance indicators get repurposed as self-improvement concepts.

Systems, like goal-setting, also have detractors. Spontaneous, intuitive, creative or emotional approaches to improvement may be suppressed in an overly rigid system. Nonetheless, understanding systems, even if you choose to apply them selectively, is a core concept worth knowing.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into systems, I recommend:

My best articles on productivity

Work the System by Sam Carpenter

The 4-Hour Workweek by Tim Ferris

Getting Things Done by David Allen

4. Emotional Self-Regulation

Much of self-improvement has to deal with managing, guiding or listening to our emotions. Indeed, those who take happiness to be an emotional state, central to our existence, may argue that all self-improvement ultimately is aimed at making us feel better.

Beyond being an end in itself, emotional self-regulation has many important instrumental purposes. Overcoming fears and anxieties represent a huge swath of self-improvement literature. Motivation and willpower overlap here as well, even if they may be better seen as concepts distinct from emotions or subjective feelings.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, sees thoughts, feelings and behavior as all being part of an interrelated system. The way you think about things affects how you feel, which affects what you do. How you feel, in turn, affects your thoughts and actions. Actions too, with their consequences can impact later feelings (exposure therapy is a clear example of this direction).

Others argue in favor of listening to emotions more than trying to manage them. In this view, emotions are important signals to tell you about the significance of events, often surpassing your ability to analyze situations rationally. The job, school or relationship you feel bad about might not be good, even if you can’t say why.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into emotional self-regulation, I recommend:

My best articles on emotions

The Emotion Code by Dr. Bradley Nelson and Tony Robbins

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Obstacle Is The Way by Ryan Holiday

5. Learning

Learning is a tricky concept here because there are actually two different senses of the word. The first is a synonym for studying. This is something that matters to students, certainly, but it may not be something that feels central to your life if you’re no longer in school.

On the other hand, learning is also a basic psychological process. Every time we change from experience, get better at anything or remember something, we’re learning.

In this second sense, learning is a core concept of self-improvement. Like habits, learning has been studied in incredible detail, making it a rich source of research-driven insights into self-improvement. Some might argue that learning is the core of psychology itself.

I’ve spent more time writing about this core concept than anything else, in part because I feel it has often been neglected in self-improvement, perhaps because many people conflate it with studying. Learning in the first sense, of deliberate studying, is also an important tool simply because it’s the means by which one can understand the other tools better, so I tend to give it priority even if other authors don’t.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into learning, I recommend:

My best articles on learning

My book, Ultralearning

My course, Rapid Learner

Peak by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool

6. Values and Meaning

Most of the core concepts I’ve discussed so far are instrumental, useful for reaching some purpose. However, a core concept of self-improvement is a reflection on those purposes themselves.

This typically moves away from psychology and more towards philosophy and religion. What you ought to value in life and how you derive meaning from things are deep questions which we’ve debated for millennia. Even self-improvement itself is a perspective, one for which some pundits argue explicitly against.

There are two levels that this issue can be approached. The first is to find a system of meaning or values that you want to self-consciously emulate. This could be Stoicism, Buddhism, Christianity or some kind of secular humanism. You might want to consciously inhibit some of your vices and enhance your virtues. You might decide that happiness is the meaning of life or that the purpose of our lives transcends how we feel in the moment.

The second level of this system is to investigate meaning itself. This is a more esoteric job of philosophers, and perhaps too abstract for many people who simply want an answer for how life is to be. But given the plurality of systems which often contradict, understanding meaning and values themselves can often help structure your decision of which to strengthen.

The variety of value systems expressed in the former is too broad to give recommendations, but for those looking to think more deeply about the issue of meaning itself I recommend:

Meaningness by David Chapman

Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

My articles on life purpose and meaning

7. Thoughts and Beliefs

Thoughts refer to the things you say to yourself in your head. Much mental content isn’t verbal, but our ongoing self-narrative is an important part of both our quality of life and as an instrument to achieving things.

What beliefs are precisely (and whether they actually exist) is less precise. Some would classify a belief as a propositional statement in your head, like a little bit of logic with TRUE or FALSE attached. Others would see beliefs as statements of probability (90% TRUE or 54% FALSE). Still others might argue that beliefs don’t really exist in our head at all, but are only inferrable by our behavior. In this sense we act as if we had beliefs, but don’t really have anything corresponding to probabilities or propositions inside our minds.

Regardless of the exact format of thoughts and beliefs, they form a core concept in self-improvement for multiple reasons.

The first is that beliefs and thoughts may become self-fulfilling prophecies. Many argue that since your thoughts and beliefs have a causal impact on your behavior, and thus your results, you may get into cycles of self-limiting beliefs that become true only because you believe in them.

Thoughts can also create emotional feelings as well, and thus we may want to control our thoughts even if we don’t care so much about changing our external outcomes. The constant worrier may have a nagging voice in her head that says her success never counts.

The importance of thoughts and beliefs ranges depending on whom you ask. For some, beliefs have mystical powers that transcend a physically justifiable version of reality. To believe something is, in a certain sense, to literally make it true. Others reject the supernatural, but argue that beliefs still highly constrain our attention, making self-fulfilling prophecies frequent. On the opposite extreme are those that argue for a mostly passive role of beliefs, recording the world but not much changing outcomes. To those people, having true beliefs matters more than believing things to make them true. Regardless of where you sit in this spectrum, the content of our thoughts and beliefs is central to self-improvement.

If you want to go deeper into this topic, I recommend:

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday

The Happiness Hypothesis by Jonathan Haidt

Awaken The Giant Within by Tony Robbins

For the more “rationalist” approach, I suggest LessWrong

Which Core Concepts Did I Miss?

There certainly are other concepts in self-improvement I’ve skipped over here. Some ideas are important, but didn’t seem as universal so I excluded them (compound growth, progressive training, metrics). If you have your own thoughts of core ideas that come up again and again in self-improvement, please share in the comments!

The post What are the Core Ideas of Self-Improvement? appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 16, 2020

Audio, Paper or Kindle: What’s the Best Way to Read a Book?

What’s the most effective way to read a book? Should you stick to paper books you can flip the pages, dog-ear and write notes in the margin? What about Kindle or other eReaders, which let you download new books instantly and cheaply? Is it okay to listen to an audiobook instead, or is that “cheating”?

The research on the effectiveness of different forms of reading seems to indicate no significant difference. There’s some research in favor of paper, for instance this study that suggested mind wandering was higher with audiobooks. Other studies have favored paper over digital.

However, my overall impression of the research is that the differences are slight, and probably outweighed by personal preference or convenience. In other words, if you prefer paper, ebook or audiobook, you’re probably free to make that choice yourself.

My Approach to Reading

I use all three formats to read, and I think the benefits of doing all is better than using just one alone.

The benefit of audiobooks are obvious: you can do other stuff while you listen. True, multitasking is likely to impair your retention and comprehension compared to complete focus. Therefore, I don’t think this is a good approach if you’re studying. But, if the choice is between folding laundry without a book and folding laundry while listening to a book, you’re definitely learning more in the latter case.

Kindle, and eReaders in general, also have similar advantages. Being able to get books-on-demand helps me a ton in research, and for filling gaps when I don’t have any books I particularly want to read. The ability to download samples has become my new approach to building a reading queue—every time I hear of a good book, I get the sample and only buy when I finish that. This saves money, but also prevents me from forgetting about books I was recommended.

Although it’s not the feature most people need, I also find digital books to be much, much easier for searching. Many books don’t have decent indices, and even when they do digital search is so much faster. When I do book reviews, for instance, I often read over my notes and highlights to refresh my understanding, something much easier to achieve with digital.

Side note: I like digital search so much that when I do only have a paper copy (which is common with academic books / textbooks), I often use Google Book search to find the page numbers which have the info I care about.

Paper books are probably best for more serious study when deep learning is more important than convenience. There’s a few good reasons for this:

Text is non-linear in general. You almost never read things in a linear progression of words and sentences, but jump back to make sense of new passages as you get more information. This is particularly true for hard books. When I recently started reading Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time, I made sure to get it on paper.

Paper is easier for flipping back-and-forth. While a novel might not benefit so much from this, it’s essential for reading textbooks. Being able to quickly jump between relevant sections to see connections is still much easier with paper than eReaders.

How Should You Approach Your Reading?

My advice is that if you’re serious about reading more books (and learning more in general) you should have all three:

Have audiobooks for moments when sitting down to read won’t work.

Keep a Kindle (and Kindle app for your phone) to increase portability and access more books more quickly.

Stick to paper books when you need to study it deeply (say for a class, work or something you expect to be difficult).

Which do you prefer? Do you use all three, or stick mostly to one source? What kinds of books do you read with each? Share your thoughts in the comments.

The post Audio, Paper or Kindle: What’s the Best Way to Read a Book? appeared first on Scott H Young.