Scott H. Young's Blog, page 32

October 28, 2019

Why I Became an Entrepreneur

I’ve run my own business for over a decade, writing and selling books and courses. In the beginning, it was just me. For the last few years, I’ve had a small team.

When I see people promoting entrepreneurship, the reasons for it are usually simple: more money, greater freedom, no boss.

But for me, the biggest draw to running a business was the pure meritocracy of it. If you can sell stuff, you make money. If you can’t, too bad.

Few professions are so directly tied to results. Even if you’re a great worker, your value is filtered through the perception of your boss, your colleagues and office politics. Academics need grants, tenure and peer approval. A programmer might be ten times as productive as his peers, but probably won’t get paid ten times as much (the other workers might think it unfair).

Incomes in most professions are compressed. Superstar employees tend to get paid less than they’re actually worth—because what they’re actually worth is often obscene. At the same time, duds can often chug along, collecting a paycheck despite producing little value.

Entrepreneurship, ideally, doesn’t have these social niceties. I remember my first month earning any money at all from my business, after having worked at it for months—I made less than fifty bucks from AdSense revenue. I’ve also had friends that have individually earned over a million dollars in a single day.

Our egalitarian instincts often recoil at these extremes. Forty dollars is not enough to live. Nobody needs millions. But these outcomes are simply the aggregation of people individually choosing whether or not to buy your stuff or visit your website.

The Reality of Entrepreneurship

That was the dream, at least. In reality, entrepreneurship has many of the same popularity contests, politics and patronage that many other forms of work do. Did someone high-profile recommend your business? That alone can put you back in the black.

While employees tend to experience income compression, entrepreneurs often experience income stretching. Many of the business processes are little engines of expontential growth. Winners take all and to each who has more is given.

Yet, despite these deviations from the ideal, I still think starting a business tends to be better on these fronts than most other types of work.

True, popularity and who-you-know continue to matter in business, just as they do in work. But, at the end of the day, you’re always tested by the market. If you can make customers happy, you’ll attract allies, investors, partners and promoters. If you can’t, not even friends in the highest of places can help.

Similarly, while income stretching is clearly less desirable than income compression (your first $100 makes you much better off than your ten-thousandth), if you can make it work, you’ve really earned it. You know that pity or pride wasn’t a factor.

High-N and Low-N Professions

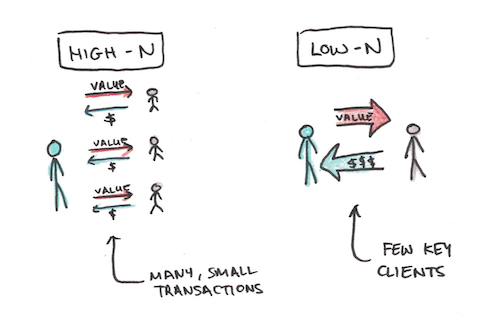

The main difference, to me, between running (most) businesses and working (most) jobs, is the number of people who need to like you in order for you to thrive.

In a business, you will have thousands of customers. In a job, you typically have only one (your boss). If one person doesn’t like you, that’s their problem; if everybody doesn’t like you, that’s your problem. The more people you have to serve, the more their decisions will converge to the true value. If you only have a couple people to please, there’s a lot more variance.

Having a lot of people to please also mutes the effect of individual politicking. When there are only a few key people to make happy, there’s a greater benefit of doing things unrelated to the work to reach that outcome. Sucking up to the boss, gossiping about rivals and forming coalitions are all common in typical jobs, but happen much less when you start a business. There are simply too many people to keep happy for this to be an effective strategy. You’re better off just making a really good product.

This also explains why different types of entrepreneurship exhibit this to different degrees. Solopreneurs who sell to consumers are one extreme—they interact with a large number of customers. In this setting, it’s easy to forget that you’re selling to actual people and not simply running a mechanical system. Seeing your customers as cogs in a machine isn’t good for business, but that it can happen at all is a testament to the relative lack of personal considerations swaying outcomes that reign in other areas of work.

On the other hand, you have businesses with few customers (think defense contractors) or fundraising stages where appealing to a handful of investors can make or break your company. Fewer patrons means success depends on more things than simply doing a good job.

Some jobs, in contrast, may be more like entrepreneurship for the same reason. Although academia has areas which require approval from a narrow set of peers (getting your PhD requires pleasing your advisor, getting hired requires a department to pick you), much of the overall success you experience is organic—do other people want to cite your work?

Some jobs, by the ease of measuring key results, also are more like running a business. Freelance writers online are evaluated on the ability to bring readers to a website. Salespeople earn commissions on the amount of product they move. This, too, shifts the work to be more like high-n professions because the boss can’t argue with results.

Would You Rather Be Judged by a Person, or a System?

Most people want the same things. To be loved, happy, safe and fulfilled. We’re far more alike than we are different.

Therefore, I think it’s interesting when you have a motivation that seems to point in the opposite direction of most people. I suspect this is the case with me.

Most people would much rather be judged by a person, and not a system. They want their crimes punished by judges and juries, not strict interpretations of the law. They want their college to admit students based on the “whole person” not simply who scored the highest score on the SAT. They want to be paid what they think they’re worth, not whatever people will pay for what they produce.

I tend to lean in the opposite direction. I think the outcomes of systems tend to be fairer than those judged by a few people in charge. People can be generous, yes. But they also tend to be petty, jealous, nepotistic and prejudiced. “Do people want to buy your stuff?” is, in my mind, a more objective question than, “Do you really deserve a raise?”

This isn’t to say the outcomes produced by systems are always ideal for society. I’m happy to pay taxes when I win to help out those who could not. But, at the same time, I’d prefer that the benefits go to help others via simple rules, not merely whomever lobbied or yelled the most.

This is why I’m always baffled at critiques of society being too mechanical and system-like. I feel the opposite! The world is run, too often, by prejudice, bias, tribal loyalty and patronage. A system isn’t guaranteed to be fair, but I’ll take it over the ad-hoc judgement of a few people in charge any day.

Entrepreneurship isn’t right for everyone. It’s probably not right for most people. It probably won’t make you more money, give more freedom or be more prestigious than just getting a good job would. But, if you want what you earn to be based on what you can make, it might be right for you.

The post Why I Became an Entrepreneur appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 21, 2019

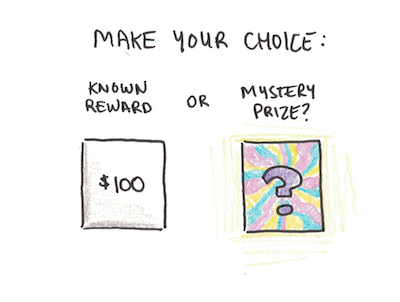

Are You Stepping Over $100 Bills Lying on the Sidewalk?

There’s an old joke about an economist walking down the street when he steps on a $100 bill lying on the ground. He spots it, but decides to walk right on by.

“After all,” he chuckles to himself, “if that had really been a $100 bill, someone else would have picked it up already!”

It’s easy to make fun of this way of thinking, but maybe the economist being lampooned here is actually right. When’s the last time you saw a lot of cash lying on the ground? In the real world, people don’t let $100 bills linger on the sidewalk.

Finding lost money is nice, but otherwise trivial. Instead, let’s consider the more abstract (and important) version of this problem, namely: how many opportunities are lying under your feet that you might be ignoring?

The implications of this are vast. If a business idea is so great, why isn’t anyone else doing it? If a scientific discovery is ripe to be found, why isn’t there a team of academics already probing for the answer? If something is broken, why isn’t anyone trying to fix it?

Ultimately, it’s not just $100 bills lying on the ground, but billion dollar companies and life-saving technologies that we may be stepping over, so I think it makes sense to think deeply about this question.

“Someone’s Already Doing That”

I once took a class called Technology in Entrepreneurship. The instructor had just recently finished his PhD, and this was a relatively new class with an unproven format. One of the assignments of the class was to come up with a “new idea” for a technology, for which our grades were based on the business viability.

I mention that it was a new class because this idea for an assignment didn’t work at all!

Virtually nobody in the class could come up with a genuinely “new” idea. Every time we, as plucky business school students, came up with a new concept that had actual market viability, it turns out a quick search revealed several companies who were already doing that exact thing.

This is part of the reason I chuckle when people want a confidentiality agreement before sharing their business idea. If the idea is any good, there are probably three or four companies already doing mostly the same thing.

As an entrepreneur, though, this isn’t a major problem. Competition is actually good because it demonstrates that other people think the market is viable. It’s when nobody is doing your business idea that you really need to get worried. Ideas without competition are usually bad.

The other lesson to draw from this experience is that, if you want new innovations, don’t ask undergrad business students to come up with them.

Leaps in innovation tend to come from people who are situated at the cutting edge of a field. They can see what might be possible a bit before other people. To use our $100 bill analogy, it’s like you find a $100 bill lying on the ground, but instead of being on the street, it’s in a private garden that only a few people can access. Suddenly the possibility that nobody else has discovered it seems a lot more likely.

But What About the Bicycle?

This line of reasoning seems to weigh in favor of innovation being hard. Most good ideas for companies are already being pursued. This isn’t a death sentence for a would-be entrepreneur, but it does put a limit on how much totally unexpected innovation should be possible.

But, then again, what about the bicycle?

Bicycles were not invented until the late 1800s. But why? All of the component technologies existed long before then. Requiring only human power to greatly increase speed and mobility, a bicycle would have been very useful in a world that only had horses and wagons. And yet, nobody seems to have thought of inventing one.

In this fascinating article, Jason Crawford dives deep into offering an explanation, but importantly, he rejects some common explanations:

“Roads weren’t good enough!” But bicycles don’t need perfectly smooth roads, and they became popular largely before good roads.

“Horses were everywhere!” True. But bicycles don’t need food and space, so from a transportation perspective they surely would have had advantages over horses (just as they do today).

Instead, Crawford argues that a major factor was simply that inventing the bicycle is hard. It’s difficult to get all of the design decisions right that will lead to not only a successful vehicle, but a commercially viable product. As a result, bicycles probably didn’t get invented earlier because nobody thought of them!

The bicycle example suggests an opposite view to our earlier example of all good ideas being taken. The bicycle is very clearly a good idea, but for centuries, nobody had thought of it.

So Which is It? Is Innovation Easy or Hard?

My own view of the situations is this: the potential for innovation is vast, but people can’t see more than one or two steps removed from what currently exists.

It’s easy to blame this simply on our own conformity and short-sightedness. But I don’t think the bicycle story really shows that. Early designs for bicycle-like things did exist.

See Jason Crawford’s original article for more images.

See Jason Crawford’s original article for more images.Rather the difficulty was that, in order for the bicycle to really work, you need to get several independent factors right simultaneously:

Single rider. The first designs for a human-powered vehicle were for multi-person carriages, not individual riders.

Two-wheeled design. It’s not obvious that a two-wheeled vehicle would be stable, or indeed preferable to clunkier designs.

Pedals. The first proto-bicycle, Karl von Drais’s Laufmaschine (running machine), did have the first two elements, but it lacked pedals. To make it move you had to run while riding it. Useful for coasting, but far from the usefulness of a modern bicycle.

Gears. Even when pedals did arrive, they were connected directly to the front wheel. This is like pedaling on a really low gear. To compensate, designers made front wheels bigger, but this also makes them harder to balance.

Rubber tires. One early version had the nickname “boneshaker.” Comfort, it seems, was a later innovation.

What we can see here is that inventing the bicycle might have been possible, but it was far from obvious. Several discrete innovations are required to have useful bicycles, and more than one are required to make something beyond a simple prototype. Without an active market for the vehicles, invention and discovery were limited to hobbyists.

The more unproven design factors need to be incorporated for an invention to succeed, the more likely that you’ll fail to think of one of them. When this happens you get things like Leonardo da Vinci’s early designs for flying vehicles—innovative, to be sure, but hundreds of years ahead of a working prototype.

Early designs for man-powered flight from Da Vinci’s sketchbooks

Early designs for man-powered flight from Da Vinci’s sketchbooksHow Do You Find the $100 Bills Lying on Your Sidewalk?

While these examples have lessons for innovation at a societal scale, I think they also teach us important lessons about improving our own lives.

First, if you want to pick up $100 bills, go to the place you see people scrambling for them! If you want to choose a good career—pick the one people are currently getting good jobs in. If you want to start a new business—pick the one that has tons of needy customers. The place nobody is looking is usually empty because there’s nothing there.

Second, most improvements happen only one or two steps removed from what currently exists. Most “tech” companies are really just applying the model of software entrepreneurship to other industries. They are innovative, to be sure, but usually only require an insight that combines what has already been done before. This is how innovation typically happens–totally unexpected ideas requiring multiple insights typically fail.

Third, while the zone of viable short-term opportunities is rarely empty, the space of possible future innovations is vast. These opportunities are often invisible because they’re not ripe for discovery yet. However, new things will open up as we inch closer to them.

And finally, if you see a $100 bill just lying on the ground somewhere—be sure to pick it up!

The post Are You Stepping Over $100 Bills Lying on the Sidewalk? appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 14, 2019

My Best Book Recommendations

Over the years, I’ve read hundreds of books and recommended more than a few on this blog. Below, I’ve organized the best books I’ve read. If you’re looking to expand your library with something great, these are some of my favorites.

My 5 Favorite Books

Below I’ve lumped books into specific categories. However, these five books have impacted me the most:

Getting Things Done. The best book on personal productivity, it inspired me as it has countless others with a systematic approach to getting work done.

The Enigma of Reason. What is reason? Why are human beings the only animals that seem to possess it, and why does it fail so often? The theory proposed in this book transformed my view of what it means to think and live, with implications that go far beyond the seemingly narrow topic. Read my summary here, or listen to the podcast discussion episode.

Deep Work and So Good They Can’t Ignore You. Cal Newport’s two best books (in my opinion) which have formed the basis of much of my thinking on career and productivity.

Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman. Richard Feynman is my hero, and his autobiography teaches more lessons on how to live than most books explicitly devoted to the topic. Smart, funny and wise, everyone should read this book. Listen to my review

Dao De Jing. The Chinese classic, this book is an antidote to much of Western culture’s obsession with improvement and achievement. Listen to my review here.

Honorable mention: Although not technically a book, or even finished, I would also like to include David Chapman’s hypertext book Meaningness, as incredibly influential in my own life philosophy.

Best Books on Career, Productivity and Achievement

Digital Minimalism – We all know we spend too much time on our phones, distracting and deluding ourselves. Cal Newport offers the antidote, a deliberate philosophy to the role devices play in our lives and to replace them with something better instead. (Another worthwhile book is Indistractable, which covers similar themes.)

Average is Over – This economics book makes a provocative argument: that because of outsourcing and automation, being average isn’t an option any more. Either you grow and get ahead, or you fall to the bottom.

The Power of Full Engagement – We often try to optimize for time management in our busy lives, but as the authors of this book argue, that’s rarely the resource that is most limited. Instead our energy–physical endurance, mental stamina, emotional bandwidth, attention and meaning–all tire out before the clock is done.

Best Biographies and Stories

Mary Somerville – Polymath, genius and 18th-century Scottish housewife, her story speaks to making remarkable accomplishments, even when the world around you isn’t supportive.

Jack Ma (马云) – China’s richest man, Ma’s story of overcoming adversity, unorthodox leadership style and entrepreneurial success is a case study for anyone who has big ambitions.

Arnold Schwarzenegger – Famous bodybuilder, movie star, politician and philanthropist. A case study in the importance of confidence and unshakeable ambition.

Marie Curie – Won the Nobel Prize twice, discovered radiation, overcame oppression in her native Poland and raised a family.

Albert Einstein – Perhaps the world’s most famous scientist, his accomplishments are so vast that, he may still be underrated for his contributions to science.

Benjamin Franklin – The original Autobiography, Benjamin Franklin is the prototype of self-improvement, hard work and optimism. Entrepreneur, author, inventor and statesman, there’s plenty to learn and admire.

Deng Xiaoping – A complex character, he reformed and opened up China to the world, which many attribute to the country’s rapid rise. His role also secured power for the Communist Party as he navigated political intrigues and survived the purging of his colleagues. A fascinating glimpse into the politics and policies of the world’s largest nation.

Vincent van Gogh – Most stories of success deal with those whose life situation made their achievements seem easy. Not so with van Gogh, who struggled throughout his life with learning to draw, paint and cope with mental illness.

Daniel Everett – Linguist and anthropologist, Everett spent decades living with a remote tribe in the Amazon jungle. In doing so he reflects on what the experience has taught him about languages and life.

Best Science Books

The Hungry Brain – Seriously researched and articulated, this book explains the science behind how diet meets behavior. Why do we overeat? Why is losing weight so hard? What’s actually going on in your brain?

The Elephant in the Brain – Signalling explains much of human behavior, whether we’d like it to or not. This book exposes the hidden motives behind why we do what we do.

Predictably Irrational – A classic on biases and heuristics, this book explores how we systematically make bad decisions, and how to avoid those traps.

Stuff Matters: Exploring the Marvelous Materials that Shape Our Man-made World – Who could have thought material science was this interesting? Exploring the hidden intricacies of concrete to chocolate, you’ll never think about stuff the same way again.

The Emperor of All Maladies – A biography of cancer and our unending battle with it.

The Secret of Our Success – We are not merely biological creatures, but cultural ones. The cultural evolution, adoption and adaptation has transformed humans far faster than our genes.

Thinking, Fast and Slow. Why do we make mistakes. Although this book often contradicts another favorite of mine, The Enigma of Reason, I think they’re both essential reading, forming a piece of the puzzle of why we think, and more often, why we make mistakes.

The Language Instinct. I love all of Steven Pinker’s books, but this is one of his best, exploring what language says not only about how we communicate, but how our minds work.

The Big Picture. What does physics tell us about how the world works? Caroll’s book is probably the best overview of what we know about life and reality as a result of science.

Best Books on Learning, Habits and Popular Psychology

Atomic Habits – The best book out there on how to change habits. Written by my friend, James Clear, (who also wrote the foreword for my book, Ultralearning) this book provides actionable plans, solid science and inspiring stories to change your habits–bit by bit.

Peak – The best book on deliberate practice, co-authored by the psychologist who first studied it, Anders Ericsson. Detailed and informative, the ideas behind this book has shaped everything I do in my career and learning.

Flow – The feeling of being “in the zone” when your attention is fully absorbed, anxieties are gone and you’re doing your best. This is what this book is all about, and the researcher who first sought to describe and study it.

The Checklist Manifesto – We tend to think of medical innovations as being spurred from big, fancy technology. But can something as simple as a to-do list save people’s lives? Doctor and author, Atul Gawande explores how simple checklists can be transformative (and, indeed, life-saving).

Best Books to Make You Think

Seeing Like a State – We live in a world of metis, but believe it is dominated by techne. This deep book explores why many visions of society have failed, and why a different kind of knowledge actually runs the world.

Godel, Escher, Bach – Life, and human consciousness, is a strange loop. In this thesis of what makes life special, strange loops are explored in computers, music, math and art.

Sapiens – What makes human beings unique? Harari argues that it is our capacity for myth–to live in invented social realities–that has made us great.

– Using a novel technique–tracking rare surnames–Clark argues that social mobility is far less than it first appears.

The Case Against Education – Economist Bryan Caplan argues that education is mostly about credentials–not teaching useful skills. He argues this powerfully despite the unpopularity of his conclusions. His ideas are worth grappling with even if you’re an ardent supporter of school.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions – We imagine science as the steady progress from ignorance to insight. In practice, it is often punctuated by revolutions where entire ways of thinking are discarded as a new view takes hold. This book coined the term paradigm and will likely overturn your thinking as well.

Best Books on Philosophy, Religion and Spirituality

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance – A journey into speculative philosophy. Maybe the Greeks got it wrong, and the quality of things precedes their objective truth?

The Wisdom of Insecurity – Alan Watts is one of those philosophers I enjoy who sometimes says stuff that sounds completely wrong to me, and other times says things that totally flip how I view life. Worth pondering over.

God: A Biography – Instead of asking who God is from a philosophical or religious angle, this book takes a different approach–consider the Hebrew Bible as a work of literature (true or not) and ask what kind of inferences we can make about the character of God as He is portrayed there. The book is deep and insightful, as are its sequels examining the New Testament and the Quran.

My Favorite Fiction

Le Compte de Monte-Cristo (The Count of Monte Cristo) – My favorite novel. Locked away for a crime he didn’t commit, Edmond Dantes escapes from prison, finds buried treasure and plots his revenge. Attendre et esperer!

活着 (To Live) – Yu Hua has the ability to make the most tragic stories bittersweet. The protagonist in this novella begins as a despicable lecher who gambles away his family fortune. After being conscripted, surviving starvation and the deaths of those around him, life goes on.

Dune – My favorite science fiction novel. Herbert’s masterpiece combines political intrigue, religion, environment, revenge, heroism and comments on the powers of myths and stories themselves.

The post My Best Book Recommendations appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 7, 2019

Five Lessons about Life and Ultralearning (My WDS Keynote Talk)

This June, I gave a keynote talk at WDS 2019 about Ultralearning.

I cover five lessons I’ve learned about life from undertaking my various projects:

The hard way is the easy way.

A little fear is very useful.

Feedback is good, so ignore most of it.

The shortest path is straight ahead.

Happiness is not pleasure. Happiness is the expansion of possibility.

This is definitely the largest audience I’ve spoken to in-person before. It was great to share some of my stories and experiences along with what is (hopefully) some advice that will make you think. I hope you enjoy it!

The post Five Lessons about Life and Ultralearning (My WDS Keynote Talk) appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 23, 2019

Thinkers vs Doers: Who Gives Better Advice?

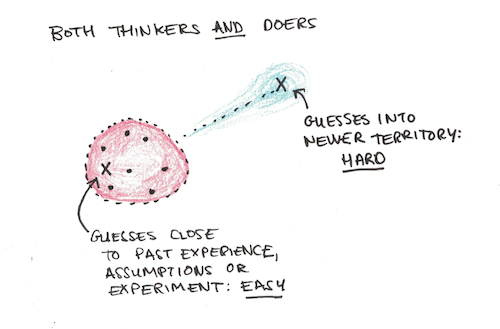

What makes someone an expert? The word is often used to refer to two different types of people:

A skilled practitioner. Someone who has personally achieved a high level of performance in a given field.

A knowledgeable theorist. Someone who has studied, argued, researched and theorized about how a field works.

In short, doers and thinkers.

This distinction tends to hold across many domains. An excellent pilot, or an expert in aviation. A crack coder, or a computer scientist. Legendary investor Warren Buffett, or Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman.

In some domains, these tend to be one-in-the-same. I don’t think it makes sense to talk about physics experts being split between doing and thinking. Doers in physics are also thinkers. Similarly, some fields lack enough theory to have thinkers—an expert sushi chef who doesn’t make sushi is a self-contradiction.

If you’re getting advice, who should you listen to: doers or thinkers? I’d like to argue that this question has a more interesting answer than it might first appear. If you can take the best parts of both, you’ll make better decisions than following only one kind.

What Separates Doers from Thinkers

Although clear examples of doing-vs-thinking exist in many domains, most examples aren’t clear cut.

Expert thinkers usually require at least some doing to properly understand their field. Linguists typically learn other languages, if only to understand their own better. They may not be the most prolific polyglots, but they can typically speak something other than English.

Similarly, expert doers usually require some theory to be proficient. An expert surgeon that doesn’t know anything about medicine is a quack.

Therefore, I don’t think it’s useful to divide up these experts based on how much they do vs think. Instead, I think the key distinction is what kind of feedback they get from their environment.

Doing VS Thinking Environments

Doers live in a world that rewards them for performance. Entrepreneurs are graded by the market, not a teacher. Surgeons succeed and fail on their ability to save lives. A pilot that crashes isn’t going to be an expert for very long.

Thinkers live in a world that rewards them for having high-quality ideas and theories, as judged by their peers. Economists are prestigious when they can make sophisticated arguments using math, models and data to make their point. Medical researchers get acclaim when they can demonstrate the efficacy of different treatments from experiments.

It’s this difference, more than the actual amount of time spent doing vs thinking, that characterizes so much of the difference between doers and thinkers.

Doers are the “Real” Experts… Or Are They?

When I first posed this problem on Twitter, I got a number of replies favoring doers over thinkers, in general. Doers actually have skin in the game, the reasoning goes, so why ever trust someone who earns esteem without actually getting their hands dirty?

In practice, however, there are plenty of situations where we trust thinkers over doers, as we should:

I’d much rather listen to a doctor, who hasn’t had cancer, about which treatment to pursue than hear about a cancer survivor’s recommended medicine.

I want my NASA rocket engineers to have PhD’s, not just a lot of experience setting off explosions in their backyard.

I’ll trust my food supplement choices to a nutritionist, not just some guy at my gym who is really buff.

Since we all accept that there are situations where trusting an expert with minimal direct experience makes sense, I think the more interesting question is why thinkers sometimes beat doers for advice. Also, if we can understand some of the factors at play, it might help sort out who to listen to when the choice isn’t so obvious.

Comparing Doers and Thinkers: Whom Should You Trust?

Doing and thinking are different skills. It’s possible to be a great practitioner and lack clear theories about how success works. This happens more often than you’d think.

Consider using a can opener. You’re probably already an expert practitioner in can openers, and you’ve probably opened thousands of cans in your lifetime. Yet, if I asked you if you could explain how a can opener works, could you?

The difficulty you’re experiencing is known as the illusion of explanatory depth. Just having a lot of experience with something doesn’t necessarily make you great at understanding how it works. In fact, in one experiment researchers were able to get participants to steadily improve their design of a mechanism—yet nobody had the correct theory for why it worked.*

This is why we need separate theorists in the first place, because simply doing a lot isn’t guaranteed to generate the right abstract-level theory about how it works.

Why Doers Can Sometimes Give Bad Advice

There are many times when being good at something directly doesn’t yield useful advice:

Experience the tree, miss the forest. Successful entrepreneurs start one company, but often give advice for all companies. Just because you know every detail of a single tree doesn’t mean you understand how the forest works.

Can’t separate successful strategy from background context. All success is a combination of both the methods a person used to succeed (which you can too) as well as background factors that are unique. Teasing these apart isn’t easy, and sometimes we do it wrong.

They don’t remember (or understand) their own success. In Cal Newport’s book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, he discusses how Steve Jobs advice differed dramatically from the path Jobs actually took. We’re always editing our own autobiographies, sometimes to the detriment of those who follow our lead.

Why Listening to Thinkers Can Backfire

This isn’t to say that thinkers are immune from giving terrible advice:

Bullshit is higher when success isn’t tethered to the real world. If you only need to sound impressive, not be impressive, then it’s easier to have theories and ideas become unhinged from the real world.

Theories can be true and also irrelevant. David Chapman tweets here about how many fields claim wide intellectual territory, but mostly debate highly contrived minutia in practice. Most problems are wicked, which makes them unsuitable for theorizing, and thus many thinkers prefer to retreat elsewhere.

Prestige often substitutes for knowledge. According to Robin Hanson, we often seek advice not to get useful ideas, but to affiliate with high-status people. If thinkers are seen as especially prestigious this can add a veneer of acceptability to their advice which doesn’t withstand actual practice.

Combining the Best of Thinkers and Doers (and Avoiding the Worst)

The best approach is to combine both thinkers and doers, to trade-off their weaknesses for each other.

The theories of thinkers tend to be better than those of doers. Therefore, if I’m trying to think abstractly, I tend to side more with ideas from scientists, academics and people who have to defend their ideas for a living rather than some guy who was successful once.

Detailed advice, however, tends to be better from doers. Specific steps, tactics and strategies tend to be better when they come from a practitioner, as this person hasn’t only calibrated against what works, but also what’s relevant.

If I were to apply these two rules of thumb to something like health, that might mean I’d want to get my general sense on which diets are healthy, what kind of exercise to do and how much from an academic source (thinkers), but I’d want the specific plan, how to make it stick in practice, motivation tips and detailed strategy from someone who is super fit (doers).

Advice from thinkers tends to be worse the further it leaves the assumptions and evidence backing up their theories. Advice from doers tends to be worse the further it leaves their personal experience. In both cases, better advice is mostly interpolation, whereas dubious advice is mostly extrapolation.

What do you think? Who do you trust to give you advice? Why do you trust those people compared to other people who offer suggestions on a topic? Share your thoughts in the comments.

*

Derex, Maxime, Jean-François Bonnefon, Robert Boyd, and Alex Mesoudi. “Causal understanding is not necessary for the improvement of culturally evolving technology.” Nature human behaviour 3, no. 5 (2019): 446.

The post Thinkers vs Doers: Who Gives Better Advice? appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 17, 2019

Explore or Exploit: The Hidden Decision that Guides Your Life

Here’s a useful tip next time you go to a restaurant: The best dish on the menu is often the first dish you ever ordered while eating at that place.

Why?

Well if you live in a big enough city, with enough locations to eat out, you end up going to a lot of places. If you have a lousy meal, you probably won’t go there again. If you have a great meal, you’ll go back often.

Any time you go to a restaurant for the first time, some of the dishes will be excellent, others mediocre. When you have a great meal, and thus decide to go back again, those meals are disproportionately from the better end of the range.

What to eat at a restaurant is a simple decision, but it embodies one of the most common types of decisions you make in your life every day: explore or exploit.

Explore or Exploit

When you go to the restaurant you always have a choice: should you eat something you know is pretty good (exploit), or try something else which might be even better (explore)?

As I’ve argued above, I think the logic mostly favors picking the first thing you ordered at restaurants you like. This doesn’t mean you should never try new dishes, just that your first pick tends to be better than a random selection would imply.

However, explore/exploit decisions come up in every aspect of life:

Should you continue with your current line of work, or branch out into something new?

Keep working on the same kind of business projects, or try something else?

Date the same person you’ve known since high-school, or see someone new?

Go to your favorite vacation spot, or book a trip to an exotic new destination?

Keep reading the current book, or crack open a new one?

Even micro-decisions like whether to drive home the usual way during your commute, or take a detour are a version of the explore-exploit problem.

Solving the Explore/Exploit Problem

It would be nice if there were a handy rule for deciding when to explore or when to exploit. It turns out that no solution is known for solving these problems in the general case, and there’s reason to suspect we may never have such a solution.1

Even in the highly contrived situation known as a multi-arm bandit (where you can choose from a finite list of opportunities, whose values won’t change when you’re not using them), a solution is known, but it’s so difficult to compute that it’s unlikely that any biological system could actually calculate the right choice.2

Side note: Birds, when given a variation of this problem seem to approximate the optimal solution, suggesting our heuristics for deciding when to explore and exploit may be pretty good.3

So if explore/exploit problems are super common, yet a general solution is unknown, how do we do it?

One option is simply to make the “best” decision you know each time, given the information available (exploit), but have some randomness added so you sometimes try something different (explore). Order your favorite dish two thirds of the time, but one third of the time, pick a different one at random.

Another option is to deliberately explore when you’ll have more time. In experiments, people are more likely to explore new options when they think they’ll have more time to act. Constrain the time, and the safer, known options are more likely to get picked. If you expect to go to a restaurant for years to come, you may want to try all the dishes, compared to if you’re only visiting that city for a week.

A third option is to integrate information outside our personal experience to guess at how good our current opportunities are. If your friends are raving about the linguini, and your pizza is so-so, you may want to switch next time even if you haven’t tried it yet.

Age and Exploration

Time plays a crucial role in explore/exploit trade-offs. Think you’ll have tons of time left to take advantage of whatever you encounter, and people become much more willing to try new things. Think time is limited and you’ll stick to what you know best.4

This impacts how we age. Children are the ultimate explorers. They’ll try things they’re bad at. Make new friends easily. Approach new situations with curiosity. (Interestingly, food may be an exception, as they may be hardwired to avoid accidentally ingesting something poisonous.5)

In contrast, as we get older, we orient our lives around known rewards. We spend time with old friends and family, rather than meet new people. We stick to existing careers and hobbies. How young/old you feel may have more to do with your perceived long-term time horizon than your actual age or physical limitations.

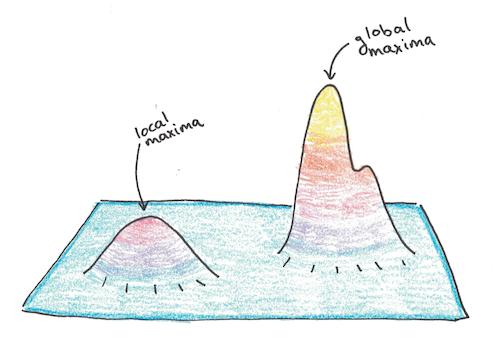

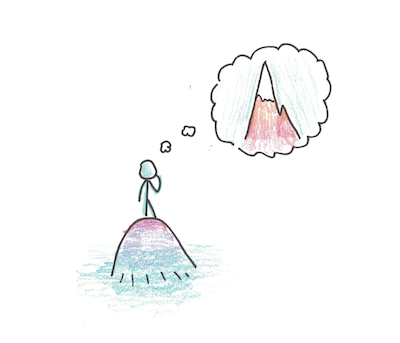

Local Maxima Traps

A local maxima is a small hill next to a mountain. When you get to the top of the hill, the only way you can go higher is by going down first. But, stay at the top of the hill and you’ll miss the views from the mountaintop.

Failing to explore enough can result in local maxima traps. A woman I knew had a promising start as a medical student, but in her early days of college started making a lot of money bartending. It became harder to do both, her grades suffered and she ended up dropping out.

Being exposed to a particularly high-value opportunity early on can trick our brains. Having seen an opportunity so much better than anything else seen, it’s easy to prematurely exploit—choosing big tips at the expense of a better long-term career.

In my own life, I felt the opposite pattern was important. It took me years to earn enough money from writing that I could go full-time. Except I was a student, so my alternatives for making money were less attractive. A different friend of mine had a successful start to his writing career, but he was making so much money as a contract programmer, after a year’s work he decided to quit.

Be wary how you judge early successes or failures. Sometimes an early success can be a trap, forever pegging your expectations to a standard most good long-term opportunities will not meet.

Ambition and Exploration

Openness to new experiences seems obviously correlated with exploration. Some people may have a personality trait that pushes them to explore more, while others opt for taking the safe bet.

However, I suspect ambition is also a factor. Ambition seems to be a combination of a knowledge of the potential that could be achieved that exists in the world, as well as a certain confidence that you might actually be able to achieve it.

More ambitious people will likely explore more, turning down great jobs and gigs, since their baseline expectations for how good rewards are “out there” is much higher. This change in strategy itself may precipitate the success ambitious people experience. If my friend had seen past her (relatively) high earnings as a bartender, she might have stuck through medical school.

I remember turning down freelance writing gigs when I still had barely enough for basic expenses. Even though those gigs paid much better than anything else I had going on at the time, I knew I wanted to build my own business, not somebody else’s. That decision cost me in the moment, but it allowed me space to work on projects that would eventually bring success.

In other cases, exploration isn’t driven by a specific ambition that you think you ought to get paid more, but by a lowered sensitivity to traditional rewards in the first place. The project that has made the biggest impact on my career thus far was the MIT Challenge.

Yet I didn’t expect to profit much from it at all, and a close friend even strongly discouraged me from pursuing it, because he felt I had better opportunities. Instead, my decision wasn’t driven by expected reward, but simply because it was a bigger unknown than anything else I was considering.

Enabling Exploration

I mentioned before that time horizon plays a pretty important role in explore/exploit decisions. This isn’t just the amount of time you have left to live, but also, how quickly you think you need a payoff in order to keep going.

A heroin addict is the extreme exploiter. Someone who has a very high reward value for a known option (doing heroin) and who needs a fix right now. Addicts don’t generally dabble for the uncertain promise of future rewards.

Even if you’re not addicted to drugs, your life circumstances also determine your theoretical time horizon for which to consider explore and exploit decisions. If you feel safe, comfortable and confident, you’ll be much more willing to quit your job and try a new career, switch majors in school, date someone different or try out a new business that may fail utterly.

More exploration isn’t always better, but having the space to explore more usually is. Our intuitions about when to exploit or explore tend to be fairly good, or at least better than a formal analysis. However, if that decision is forced—because getting by today demands sacrificing trying anything new—we may end up making worse decisions.

I think there’s a couple ways you can create this kind of space, psychologically, to at least allow for the possibility of more exploration in your life:

Become financial secure. This means living below your means. Making regular savings (including an emergency fund).

Avoid busyness. Regularly de-busy your life, by saying no to minor commitments and schedule gunk that has accumulated. Exhausted people tend to explore less.

Block off time for new things. If you can’t delete things from your calendar, put blank spots on there, where you can push yourself to meet new people, learn new things and go new places.

Create stable friendships and relationships. We need more than money to thrive, and being lonely or in toxic relationships can push short-term decisions that don’t match your long-term interests.

Be comfortable with less. I know people who earn six-figures and feel psychologically trapped, while people who earn just above the poverty line have spaciousness. This isn’t to say money isn’t important, but only that it’s possible to have quite a bit and trap yourself because you set your required lifestyle right below the amount you earn.

I don’t think spaciousness necessitates exploration. If you’ve got a great spouse, you probably won’t get divorced just because you can. Rather, it allows you to better make optimal decisions rather than stay stuck picking between crappy choices.

Cultivating spaciousness itself isn’t easy. If you feel trapped, no platitude will open the world up instantly for you. Instead, you make small changes that slowly increase the space you have. Improve your finances, health and time management so that constraints which felt overwhelming loosen up a little.

More than anything, however, I think cultivating space is a goal you should have. For many, the aim of life is to squeeze the space out of every moment–every dollar spent, every second scheduled. In this case, I think the attitude of optimization may actually be a weakness, if it closes you off to new opportunities that might be better than anything you’ve seen so far.

The post Explore or Exploit: The Hidden Decision that Guides Your Life appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 10, 2019

Book Recommendation: Indistractable

I recently finished reading an advance copy of Nir Eyal’s new book, Indistractable. Even as someone who has written extensively about focus and productivity, the book was densely packed with useful advice.

The obvious comparison to Indistractable is Cal Newport’s, Deep Work and Digital Minimalism. Heck, the book even has the same yellow cover. (I guess yellow is the color of focus?)

I was pleasantly surprised, then, that Indistractable is a lot more than just rehashing what you’d already expect. In many ways, Eyal’s book is a good companion guide to Newport’s introducing different ideas and techniques. For a problem as big as distraction, two books are definitely better than one.

The 4-Part System for Being Indistractable

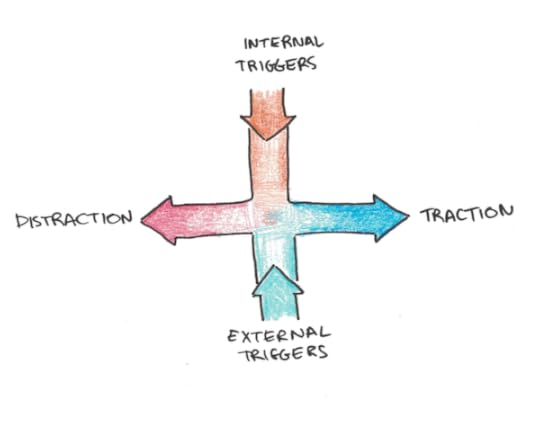

Eyal breaks down his system for becoming indistractable into four parts, neatly visualized as a crossroads of four intersecting factors:

*This is taken from Indistractable, but this illustration is my own.

*This is taken from Indistractable, but this illustration is my own.The vertical axis explains why we often get distracted. External distractions are some of the problem. But, as Eyal explains, a lot of our distractions come from within. It may be easier to blame your smartphone for your distraction than to confront all the ways you’re distracting yourself to avoid boredom, frustration or the truth that you’re not doing what you need to in life.

The horizontal axis splits between distraction and “traction”. Distraction is what you’re trying to avoid. Traction is what you’re trying to accomplish.

This is also a useful distinction because once you overcome your distractions, what do you do then? Do you just fill your waking hours with more work? Do you stare blankly at the walls of your house, waiting for something to happen?

Any conversation about giving up distraction must be paired with a deep reflection of what kinds of activities you’d like to do instead.

What Sets This Book Apart

Is technology to blame for our distractedness? Or is technology just the symptom of our deeper issues with living the kind of lives we want?

I found Eyal’s take useful because, while I also enjoyed Deep Work and Digital Minimalism, I still use technology a lot. I use Twitter. I watch YouTube. I have email, an iPhone, text messages and group chats. I use these because they make my life easier and more enriching. While I have taken hiatuses from them, I always go back because I find them valuable.

Despite deciding, overall, that I want these services in my life, I also find that it’s tempting to overuse them. It’s easier to continually refresh Twitter, rather than go read a book. It’s easier to watch a Netflix show than to have a deep conversation with your spouse. It’s easier to play on your phone than to truly be present.

Eyal, like me, doesn’t demonize technology, but recognizes that we need to be in control of it and not the other way around.

On Raising Indistractable Children

Tucked away, at the end of the book, Eyal argues what is perhaps the most healthy and sane approach I’ve seen from parenting in awhile. He argues that you ought to treat your children like rational individuals and help them become indistractable themselves.

Instead, the approach I so often see from parents is that of the do-as-I-say-not-as-I-do parenting, where parents who are wrapped up in their own distractions nonetheless demand ascetic habits from their children.

I’ve faced this with parents who ask how they can get their children to use effective studying methods. I’m always surprised that the answer, “Assist them in making a study plan so they can accomplish their own goals,” rarely crosses their mind. As if children lack their own values and priorities, for which academic success is just one goal of many.

Eyal talks about working with his five-year old daughter to set limits on how much time she spent on the iPad. To his surprise, when he asked her how much she thought she should use it per day, the answer wasn’t unlimited but a modest two episodes of her favorite show.

Since ever-escalating controlling parenting seems to be the norm, it was refreshing that Eyal argues that we ought to treat our children like human beings.

Recommending Indistractable

Focus is an important topic. No one book or resource can give you all of the ideas and tools that might be helpful. The question therefore, isn’t whether you should read this book or Cal Newport’s or my articles, but whether this guide offers new ideas and advice to take you further. Indistractable does.

The post Book Recommendation: Indistractable appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 3, 2019

How to Think About Your Life’s Work

Last week, I wrote about getting better at something you’ve done for decades. In my case, writing.

But what does it mean for your work to be “better”? Especially something creative like writing. Is the better author the one who sold more books? Won more awards? Or is it a personal question about the meaning you give your life’s work?

Below, I’d like to outline my thought process for answering this question, with the hope that it may encourage you to think about your process for evaluating the work you do in your life.

The First Rule: There are No Rules

A knee-jerk reflex when dealing with the question of “better” is to try to define it in words. This is the same impulse that results in so many insipid corporate mission statements full of well-meaning words like “community” or “service.”

The problem isn’t with missions, service or community. Rather, the difficulty is that the goals you have for your life’s work are about something you feel, not something you think. Turning those feelings into bullet points can only leave things out.

The truth is, we don’t perceive any value explicitly through rules and sentences.

This sounds mysterious, but it’s really not. We also don’t taste things through explicit rules. If I gave you some ice cream and asked you to tell me if it were chocolate or vanilla, you wouldn’t consult a 98-point feature chart to decide, you’d just let your tongue do the work.

Similarly, you don’t really evaluate your work by rules either. Instead you create something, and then ask yourself how you feel about it. Sometimes that feeling is good. Sometimes it’s bad. More often, it’s a mix of emotions, with both the things you’re proud of and the potential you didn’t quite feel you reached. None of which is easily expressed in a sentence.

If There Are No Rules, How Do You Get Better?

So if you’re not actually following rules when deciding whether your work is good or not, how can you possibly improve?

This, too, is actually easier than it sounds. We do it all the time.

You make scrambled eggs and they taste better than last time. You don’t need a feature-by-feature breakdown scored by experts to know this. You just chew.

Improving in your work is very similar. Do I like this more than what I made before? Compared to others’ work? What could have been made better? What did I do well?

Some people are uncomfortable approaching things this way. They’ve become so convinced that everything ought to be measured, analyzed and dissected that they forget they can simply taste things.

Why Just Tasting Doesn’t Always Work

The scrambled eggs analogy, however, isn’t a perfect one. Because we don’t just cook for ourselves.

Your work may be driven by your own taste buds, but ultimately its whether other people can stomach it that decides if you can make a living. You may adore your banana jalapeño omelette, but that’s not enough to make you into a chef.

As a result, the meaning of our work always hovers in a fuzzy boundary between personal taste and outside appreciation. The meaning of our work is never entirely decided by us. It’s filtered through the tastes of other people.

This can lead to two different mistakes:

Only following your own taste.

Losing the ability to taste your own work.

Only following your own taste can lead to solipsistic, naval-gazing work that only the artist appreciates. This is a serious problem because, as the creator of something, you are, at least in some ways, never like the people who simply consume it.

Conversely, you can get so focused on the outside that you lose your sense of taste. You chase reviews, acclaim, sales and applause. You want to be respected by others, never asking if you respect yourself.

The challenge is to balance both. To have a refined palette for your own work so you can improve, but at the same time recognize when your tastes diverge from the people you serve.

How to Do Work You Love (That Other People Love Too)

The only solution is to pay attention to both. Cultivate your own sense of taste for your work, but at the same time keep an eye on how others are consuming it.

The first step in balancing these two competing signals is to see when they are likely to fail. Personal taste can be misleading when:

Your interests differ from your audience. You may care about something much more or much less than the people you want to reach. You love spice, but your guests can’t take the heat.

You know things your audience doesn’t. You may know things about the world your customers don’t. Connoisseurs notice flavors a novice will ignore.

You can’t see with fresh eyes. For you, this work might have taken thousands of hours. Chew something over that much and it tastes differently than someone taking the first bite.

Similarly, signals from the outside can also mislead:

Sometimes success (or failure) means nothing at all. Some things you do will be popular, some won’t be. Sometimes there’s a lesson to be learned. Sometimes it’s just luck.

Most people really do judge books just by their covers. Most will only skim the headline, remember the sound bite, tweet the hashtag. But you want your life’s work to be more than just catchy.

They ask for the old, but want it to feel like how it was when it was new. Forever trying to replay your greatest hits repeats the surface forms, not the way people felt about the original.

Balancing personal taste and outside appreciation is hard. It’s easy to swing to one extreme then the other. To be the starving artist who won’t listen to any outside feedback for fear of tainting a personal vision. To check sales, reviews or scores obsessively to validate your worth.

Like the question of taste itself, integrating the two signals is more art than science. I tend to trust my own taste first, but moderate based on outside feedback. If I love something but others don’t, that’s an opportunity to dig deeper to ask why.

Improving Your Sense of Taste

Getting better is a twofold process. First, getting better at your work, as judged by your sense of taste. Second, improving your sense of taste itself.

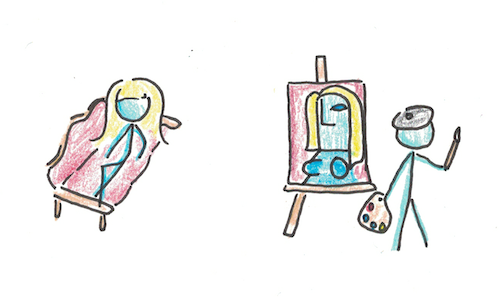

The first way to have better taste is to consume a lot. If you’re a writer, read. If you’re a painter, look. If you’re a programmer, read other people’s code.

Consuming better work improves your sense of taste in two ways. The most straightforward way is that more data leads to better discrimination. See one good movie, and all the movies you see will be compared to that one. See a thousand good movies, and your appreciation of cinema will be much more nuanced.

The subtler (and sometimes dangerous) way consuming more improves your taste is that you unconsciously imbibe successful styles from the past. You mimic what has worked well for others, while still making it your own.

This second process isn’t without risk. Too much exposure to others and you lose your beginner’s mind. You can no longer see something with fresh eyes, but only through a kaleidoscope of other work.

Rediscovering the Beginner’s Mind

Consuming more isn’t enough. You also need to learn to unsee. To empty your mind of what you’ve filled it with before.

Unlike simply consuming more, this is much harder to do. Talking to people helps. I find travel helps. Ironically, learning something completely new also seems to help, as you return to the starting point of all things.

Better taste isn’t enough for better work. You can have a refined palette but be unable to cook. If you want to get good at making, not just critiquing, then you actually need to make stuff.

The Meaning of Your Life’s Work

Meaning isn’t subjective. But it’s not objective either. It follows patterns, but it doesn’t break down into explicit rules.

So too with the meaning of your work. It’s personal, depending more on taste than recipes. But it’s also not only for you to decide. To matter, it also has to touch the minds of others.

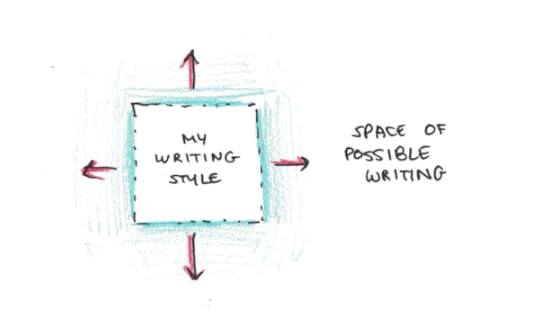

This is challenging, but also exciting. The space of possible things to be made greatly exceeds what will ever be made, both now, and until the end of time. Your work allows you to explore one sliver of possibility, and bring something into the world that, without your care and skill, would never have existed.

The post How to Think About Your Life’s Work appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 26, 2019

How Should I Get Better at Writing?

Suppose I wanted to get substantially better at writing, maybe through some kind of deliberate ultralearning project, how should I do it?

Improving when you’re at zero is quite different from improving when you’ve already invested tens of thousands of hours into your craft.

I’ve been writing for over thirteen years. I’ve written around 1500 blog posts, 5 books and probably a couple million words of text. I was trying my best for each sentence, so simply trying harder isn’t a good strategy.

Yet, at the same time, it’s not as if no improvement is possible. If there’s anything the research on deliberate practice shows is that people tend to plateau absent special effort. The volume of writing I’ve done may have even calcified some bad habits. Practice making permanent, rather than perfect.

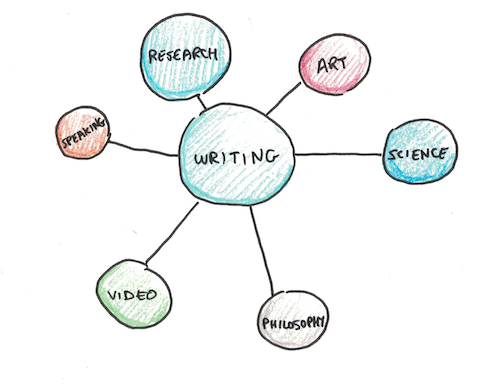

Why I’m Interested in Mastering Writing

I think writing, like many complex, creative skills, offers a lot of learning challenges that make it interesting. Here are just a few:

It’s not clear what makes good writing good. Great writing provokes and inspires. But it’s not always obvious what makes it different from mediocre prose. And, when your writing sucks, it’s even harder to say how to fix it.

We don’t always agree which writing is good. Nuanced or pedantic? Descriptive or verbose? Insightful or obvious? That we sometimes disagree can make improving harder than when quality is indisputable.

Good writing depends on more than just technical brilliance. Resonance with an audience means that writing is a vehicle for communication, and the sophistication of your writing doesn’t mean a damn if you say something other people don’t care about.

Yet, these challenges are also what make it intriguing as a learning project. When learning is just about memorizing facts and passing tests, it becomes boring. When it’s about doing something you can’t quite see how to get better at, that’s when it feels exciting.

What Approach Should I Take?

I’m not ready to pull the trigger on a new ultralearning project. However, I do think brainstorming a little at this stage might be useful. Rather than wait until I’ve made up my mind in private, I’d like to share some of my thoughts on this now.

I can think of a few approaches that might work to improve my writing:

1. Analyzing and emulating better writers.

One approach would be to pick people who I think are better writers than I am (either in terms of recognized success, or simply because I like their writing a lot), and then analyze and emulate their writing methods.

I see this approach being helpful in two ways. The first would simply be replacing ineffective habits of mine with more effective ones. If I see that someone can do something better than me, deconstructing and emulating their example will help me do it better too.

The second benefit might be expanding my toolbox. There are styles of writing I’m not strong with, that if I became more comfortable with, I might be able to apply them better to new forms of writing. Research, humor, storytelling, visual language, pacing, etc..

2. Figure out what drives quality in writing.

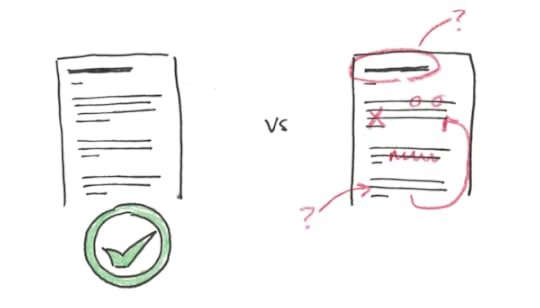

A qualitative analysis of other writers is interesting, but it might also be possible to do something more quantitative. Could I put an article I wrote next to someone else’s and get anonymous bystanders (or maybe Mechanical Turk) to judge which they prefer?

If you can do that, then you could also systematically vary components of the writing. Why do people like A instead of B? Is it the headline? Opening story? Readability? Do the comparison again and see what comes out of it.

This isn’t to say all writing is reducible to discrete elements, that if you just improve your headline writing by 10%, you’d win a Pulitzer. But, it would help disentangle competing hypotheses such as the importance of someone’s name, topic choice, credentials or simply hitting the right cultural zeitgeist.

Doing this kind of quantitative analysis wouldn’t be trivial, but I wonder if it’s not also something one could do in other industries/professions as well?

3. Seeking a more demanding feedback environment.

As I’ve written before, the environment can often determine the level of proficiency attained. My background as a blogger has both helped and hindered me in becoming a better writer.

For help, public blogging has meant most of my work has received some scrutiny and attention. That feedback makes it a lot easier to learn and grow.

However, I also haven’t had the same editorial scrutiny that journalists writing for major publications do, or academics who have to defend their ideas in front of experts and peers. Both of those environments cultivate different skillsets, since the feedback prevents sloppiness that would go uncorrected on a blog post.

I don’t have any plans to join a newspaper or get my PhD, however, so I would need to do something else to improve. Perhaps writing op-eds for bigger publications, hiring an editor to improve my articles or pushing myself into conversations with people much smarter than myself to force me to improve my ideas.

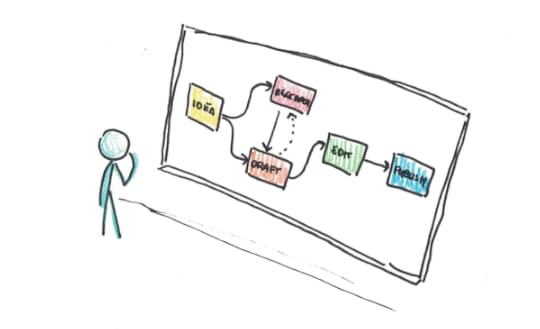

4. Process improvement.

It might also be useful to distinguish getting better at a skill, versus having an improved process for creating works with the skill you have. While the former involves improving your potential, the latter involves improving how your work is done in practice.

I know, from doing research on my book, for instance, that I have the capacity to include engaging stories and deep research. Yet, I don’t usually apply these skills fully for my blog articles because I don’t usually have enough time.

In this sense, improving my writing might be more about creating processes and habits that allow me to more consistently output writing near the upper part of my quality range, rather than increasing my theoretically possible writing, and then rarely reaching it in practice because of time constraints.

5. Improving writing-adjacent skills.

It might also be that writing itself isn’t my bottleneck. That I could deliver more effective writing if my ideas were better, if I had better life experiences to draw from, understood difficult subjects in more depth or cultivated authority to speak on more topics from better credentials or real-world successes.

This certainly has been a part of my already-existing strategy at improving writing. My previous learning projects helped me immensely with my writing, not by improving my writing itself but giving me something unique to talk about.

In practice, it’s often difficult to tease apart writing from the writer. Do I like Paul Graham’s essays because he’s a good writer and thinker? Or do I respect him for his entrepreneurial success and that elevates his writing in my eyes in a way I would disregard if it came from someone unproven?

This might also be something to test using Approach #2. I suspect both are important, although it’s not entirely clear what the split ought to be.

6. Exploring outside of my comfort zone.

Perhaps the key to successful writing is simply being different. Maybe writing quality is stochastic itself, and so those who take the most swings are the ones with the most home runs, and that the greater your variability as a writer, the better you’ll perform.

I’m not convinced this is a complete explanation of writing talent, but it’s also possible that my writing weaknesses are from being stuck repeating the same successful strategies of the past.

Getting out of your old habits, however, is easier said than done. Just wanting to be different isn’t usually enough. You usually also need creative constraints which force you to do something that doesn’t come automatically.

Random constraints and a random search strategy may also have the possible benefit of exploring entirely new territory in ideas and writing, which is a defect of Approach #1. If the thing that makes a great artist great is that he or she is like nobody else, then emulating successful strategies may end up repeating styles that are already overdone.

Is Analytical Improvement of Creative Skills Even Possible?

All of this deliberate improvement presupposes that this is even the right paradigm for thinking about improving creative skills. While I lean in favor of this view, others might argue that creative skills are either impossible to evaluate in terms of goodness, or that analytical approaches to mastery are doomed to fail.

One argument might be that “quality” itself in writing is totally arbitrary. Van Gogh was a brilliant painter. However his work went largely unrecognized in his lifetime. The art world around him certainly didn’t see his work as being anything special, until they changed their minds and made him one of the most famous painters of all time.

In the same way, it might be the case that what makes someone a good writer is simply irreducible to any kind of analysis. A “bad” writer, who, through chance, later becomes famous, may have all her previous work re-evaluated and elevated to the level of brilliance. If quality is determined through a fickle process of social consensus, it might be a mistake to talk about mastery in the first place.

Another argument might say that “quality” is achievable, but that it’s strictly impossible to reach this via analytic methods. This is certainly the view of some creativity researchers, who separate mundane acts of technical innovation and problem solving from “genius”-level creativity, which is genius precisely because it can’t be reduced to a formula or analysis, perhaps except after the fact.

Following this train of thought, getting better at writing is a process of inspiration and disinhibition. An emphasis on quality, particularly if it’s enforced from top-down processes of self-control, is a move in exactly the wrong direction.

I try not to rule out any hypotheses when approaching problems, but taking either of these as a starting point seem like non-starters for a project, so I’d probably set them aside for now. That may be the equivalent of the drunk looking for his lost keys under the streetlight because he can see better there, but I’m not sure there’s any way around it.

How Do You Approach Getting Better at Something You’re Already Good At?

What skill do you spend your life doing? How do you approach getting better at it, especially if you’re already pretty good? Are there any strategies and theories I’m missing above that I should consider? Share your thoughts in the comments.

The post How Should I Get Better at Writing? appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 19, 2019

I’m 31

Today is my thirty-first birthday. Every year on this blog, since I was 18, I’ve written a birthday post, sharing some of what I’ve done in the past year, as well as my plans for the future.

In some ways, this tradition itself feels strange. When you’re in your early twenties, each year feels like a huge milestone. Now, without grades or graduations to separate chunks of time, years start to blur together.

However, perhaps the fact that years blur together is all the more reason to pay attention to them. Mark out time, so that it doesn’t slip away from you. Don’t let decades pass without having done the things you wanted to do.

What I Did Last Year

The biggest event of the last year happened just a few weeks ago–the publication of Ultralearning.

Writing this book has been, without a doubt, the hardest project I’ve undertaken. Not because of something intrinsic to writing a book, but because I felt enormous pressure, and that often made it challenging to make progress.

For starters, the topic of this book has been basically my entire adult life. While there will be other ideas for books, I wouldn’t get another chance to write this, so I knew I wanted to make it count.

Second, I knew I wanted to write something I hadn’t done before. I wanted the book to explore other stories, not just my own–which meant I had to get good at finding those stories. I knew I wanted the book to talk about science intelligently, which meant trying to pore over thousands of pages of research, just hoping that I’m not going to misinterpret the work of specialists.

The book has since become a National and Wall Street Journal best-seller. Sales are great, but even more rewarding have been the comments from readers. As of this writing, we have 18/20 5-star reviews on Amazon, and 4.33 on Goodreads (out of 87 ratings).

In the end, I’m proud of the book I was able to write. But I’m more proud that I didn’t let the stress and fears it created win.

Italy + Macedonia

I also went on a honeymoon with my wife, Zorica, to Italy in October last year. We started in Positano, on the Amalfi Coast, and went north, through Rome, Tuscany and finally Venice.

We even decided to do a (mini) ultralearning project: sketching. My goal was to do one sketch a day on the trip. I’ve done sketching trips before (previously, a couple years ago in Beijing), and it can be a lot of fun, even if you’re not an artist.

I like the way drawing forces you to really look at things, in a way that snapping a photograph may not. Plus, it was a fun activity to do with Zorica, drawing our way across Italy.

Positano, Italy

Positano, Italy View from our balcony in Rome

View from our balcony in Rome AirBnB in Tuscany, near Lucca

AirBnB in Tuscany, near Lucca Venice

VeniceAfter Italy, we spent two weeks in Zorica’s home country of Macedonia. She moved to Canada when she was fourteen, and it was her first time going back home in sixteen years.

I didn’t go No-English this time (her cousins speak English quite well, and my goal in the first visit was to make a good impression with my in-laws, not rapid fluency) but I did manage to learn a little Macedonian, which will hopefully improve over future trips.

Bazaar in Skopje

Bazaar in SkopjePlans for Next Year

I already have a few projects underway for the coming year.

I want to improve the quality of the articles I write on the blog. Writing this book was great for learning how to produce more engaging, well-researched work. But, it was also a reminder that my blog posts rarely reach that level of polish. I’d like to try to change that in the coming year.

I’m working on a new course with Cal Newport. We’ve been in talks for over a year now to try to deliver a course which will break down the approach to life we’ve been separately advocating on our blogs, of deep work and learning, and turning it into a set of concrete habits one could be guided through in a course. It’s still in development, but I hope to have more news sometime in 2020.

New ultralearning projects? An obvious question, after having finished writing the book, is what ultralearning projects I want to tackle next. I still haven’t made up my mind, but right now I’m inclined towards applying it to the skills within my career rather than learn completely new and unrelated ones. Regardless of what I choose, I’m always actively learning new things, even if I don’t always make a big public project out of them.

Finally, thanks to everyone who has been following my writing over the years. Because of you, I’m able to do what I love for a living, and I don’t take that for granted. I look forward to sharing the journey with you.

The post I’m 31 appeared first on Scott H Young.