Scott H. Young's Blog, page 35

July 3, 2019

The Best Articles on Learning

Learning matters to everything you do in life. Here are the best articles I’ve written on the subject.

The 5 Best Articles

Although I’ve written hundreds of articles on the subject, if you’re not sure where to start, read these five:

How to Start Your Own Ultralearning Project (Part One, Part Two) – The process behind taking on ambitious projects to learn hard things.

The Complete Guide to Memory – Everything you need to know about the science behind long-term memory.

How to Learn a Language in Record Time – How I’ve learned Chinese, Spanish, French, Korean, Portuguese and more.

The Feynman Technique [VIDEO] – How to understand difficult ideas.

Five Scientific Steps to Ace Your Next Exam – The science behind the right way to study.

Ultralearning

Ultralearning is a strategy for aggressive, self-directed learning. My book shares the science and stories behind people who’ve accomplished big things through learning hard subjects in unique ways:

Here are some of the initial articles which motivated the book and explain the concept:

How to Start Your Own Ultralearning Project (Part One, Part Two) – The process behind taking on ambitious projects to learn hard things.

Ultralearning Environments: Why Where You Learn Determines How Much You Learn

How is Ultralearning Different? Exploring what ultralearning is, and how it differs from the approach most people take.

In addition to writing about ultralearning, I’ve also taken on my own ultralearning projects. Here are my more popular projects:

The MIT Challenge. My project to learn MIT’s 4-year computer science undergraduate curriculum, which I did over 12 months from October 2011 to September 2012.

The Year Without English. Learning Spanish, Portuguese, Mandarin Chinese and Korean by avoiding speaking English for an entire year.

Portrait Drawing Challenge. Thirty days devoted to trying to improve my ability to draw faces well.

Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics. One month to learn the basics of quantum mechanics. This entire project was livestreamed as well–so there’s a complete record of what I did to learn it.

Holistic Learning

Before ultralearning, one of my more popular ideas on learning was holistic learning. This approach to learning things argues that learning through making connections, analogies, examples and pictures leads to a better understanding than rote memorization.

My book Learn More, Study Less, is largely about this approach to learning.

Here are some popular articles I wrote on holistic learning.

How to Ace Your Finals without Studying – My first post on holistic learning, and how I applied it to ace exams in college without lengthy studying sessions.

How to Become a Holistic Learner – Addresses some follow-up questions to the original post which started it all.

Holistic Learning Free Ebook – This short ebook summarizes holistic learning and provides some of my thoughts prior to writing Learn More, Study Less.

How Do You Make a Good Analogy? – Analogies were a central piece of holistic learning. Here’s how to make good ones.

Flow-Based Notetaking – How to take notes that link ideas together, rather than just transcribe what you’re listening to.

A Brief Guide to Learning Anything Faster – Overview of some holistic learning concepts.

Side note: Although holistic learning was (and remains) one of my more popular ideas about learning, I feel like my more recent work is better grounded in the scientific research of how learning actually works. I still think there’s some useful ideas here, but if my current writing and past writing occasionally contradict it’s usually because I learned something about learning which changed my mind!

Complete Guides on the Science of Learning

Want to know how learning really works? I’ve collaborated with cognitive science PhD student Jakub Jilek to produce some longer essays on the science behind learning:

The Complete Guide to Memory – Everything you need to know about the science behind long-term memory.

Working Memory: A Complete Guide to How Your Brain Processes Information, Thinks and Learns

Here are some other articles, dealing with specific facets of the science of learning:

Seven Principles of Learning Better from Cognitive Science

How Much Do You Really Understand? (Experimental, interactive article on why there’s always more depth than you think!)

Is the Brain Like a Muscle? Debunking a Seductive, but Incorrect, Idea

Flow Doesn’t Lead to Mastery

How the Brain Changes with Expertise

Do You Need to Be Smart to Learn Certain Subjects?

The Bicycle Problem: How the Illusion of Explanatory Depth Tricks Your Brain

Which Learning Methods Actually Work? – Discussion of some research investigating the scientific support of different learning methods.

How to Learn Specific Subjects and Skills

In addition to writing about learning generally, I’ve written a number of articles about how to learn specific subjects, or how to deal with specific learning challenges:

How to Learn a Language in Record Time

How to Learn English

How I Learned Spanish

How to Learn Chinese: 8 Things I Wish I Knew Before I Started (and my strategy after coming back from China)

How I Learned French (Note: I did this before my intensive immersion experiment)

How I Learned Portuguese

How I Learned Korean

How I’m Maintaining the Ability to Speak Six Languages

How Do You Learn a New Language, Without Forgetting the Old One?

Why You Shouldn’t Learn a Language the Way Children Do

How to Learn Programming / Computer Science

The 7 Core Skills to Drawing Realistic Pictures

Five Steps to Become a Better Writer

How to Teach Yourself Math

Learning Calculus in Five Days (and if *you* had to do it in 15 days, what should you do?)

Why Learn Math?

How to Study for a Standardized Test

How to Learn Social Skills

How to Learn History (Read Biographies, Not History Books)

How to Learn (and Apply) Information Products

How to Improve Critical Thinking

What’s the Difference Between Learning an Art and a Science?

How to Learn Boring Subjects

Completing an MIT Physics Class in 4.5 Days?

Should You Learn Physics Like Newton? Contrasting Expert and Beginner Learning Strategies

How to Teach Yourself Anything (in a Fraction of the Time)

The Beginner’s Guide to Learning to Program

How to Learn Really Hard Courses

How to Memorize a Speech

Tools for Learning Faster and More Effectively

Struggling to learn something hard? Here are some of the best tools for learning hard skills and subjects:

The Feynman Technique [VIDEO] – How to understand difficult ideas.

Five Scientific Steps to Ace Your Next Exam

How to Take Notes While Reading

How to Study Without Practice Problems

How to Enjoy Studying

How to Stop Forgetting What You Read

Why I Was Wrong About Speed Reading (and What to Do Instead to Read Faster)

How to Read More Books

Easily Distracted? Use Orienting Tasks When Learning

Why I’m Skeptical About SRS for Conceptual Subjects

Why Braintraining Games are Silly

Keeping To-Learn Lists

Are Blogs Better than Books for Mastering Complex Ideas?

Big Ideas on Learning

Beyond tactics and tools, here are some of my best articles about my philosophy of learning and how to approach learning new things:

Fluency vs Mastery: Can You Be Fluent, Without Being Good?

Should Learning Be Hard?

How Much Theory Should You Learn for Practical Skills?

There are No Hard Subjects, Only Missing Prerequisites.

Should You Learn Things You Don’t Plan on Using?

Learning Rule: Quantity, Then Quality

What Most People Get Wrong About Effective Learning

The Art of Unlearning

How Much Faster Can You Learn? (and: How Much Can You Possibly Learn?)

Cultivating the Skill of Figuring Things Out

If You Had 10 Years to Learn Anything, What Would You Do?

How Einstein Learned Physics

Should You Try Learning More than One Thing at a Time?

Learning What Can’t Be Taught

Should You Learn Fast or Slow?

With the World’s Knowledge a Click Away, We Spend Our Time Looking at Funny Pictures of Cats

At What Age is it No Longer Okay to Be Bad at Something?

Should You Use Deliberate Practice… or Just Practice?

Should You Know Your IQ?

Which Skills Should You Master?

Are There Books You Should Reread Every Year?

Should You Maintain (an Almost Zero) Reading Queue?

Is it Better to Review Back or Learn Ahead?

Things Worth Knowing Well, Things Worth Knowing Poorly (follow-up to an interesting quote about languages being something worth knowing, even poorly)

The 7 Most Common Learner Mistakes

The Importance of Knowing What You Know

Do Habits Hurt or Help You Learn?

Why You Should Read Textbooks

Why Forgetting Can Be Good

Should You Learn New Skills, or Master Old Ones?

Developing an Appetite for Hard Ideas

Is What You Learn in School Really Useless?

Why Self-Educated Learners Often Come Up Short

What if You Never Graduate?

The Goal of Learning Everything

Rapid Learner: My Course on Effective Learning

Just reading isn’t enough, you actually need to put in the work if you want to become a more effective learning. My 6-week course, Rapid Learner, will guide you through the process of designing, executing and optimizing your own learning projects.

Sign-up here to find out about our upcoming sessions so you can learn better too.

The post The Best Articles on Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 2, 2019

Useful Mental Model: Evolution by Natural Selection

Some ideas are so powerful and general, that once you learn them you start seeing them everywhere. Today I’d like to discuss one of those ideas: evolution by natural selection.

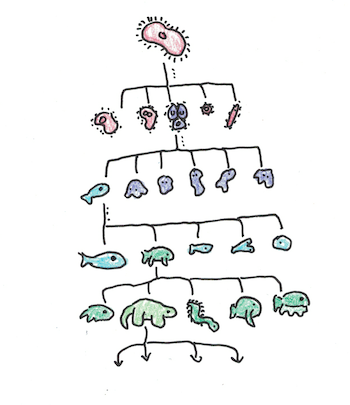

Evolution by natural selection was one of the greatest intellectual triumphs of the last thousand years. The great diversity of life, including human beings, is the outcome of a rather simple process, repeated a tremendous number of times over billions of years.

Yet biological evolution is just a principle example of this pattern, it’s not the only place it applies. If you take the analogy more approximately, it can apply to far more things and allow you to reason about culture, ideas, technology and more.

Evolution by Natural Selection

Commonly shortened just to “evolution”, evolution by natural selection is a relatively simple model. To have it, you really only need three things:

A mechanism for creating copies with high-fidelity (aka replication).

A mechanism for changing the copies slightly (aka mutation).

Different copies should persist and copy at varying rates (aka fitness).

Once you have these three things, the outcome is that, over time, the copies that survive and replicate better will multiply, and “ineffective” copies will die off. What starts as a simple, random process, can create a ratchet leading to better and better versions.

Evolution is such a popular idea, however, that it risks being used to casually without really understanding the mechanism by how it works. Consider a popular false analogy I first heard called out by Eliezer Yudkowsky.

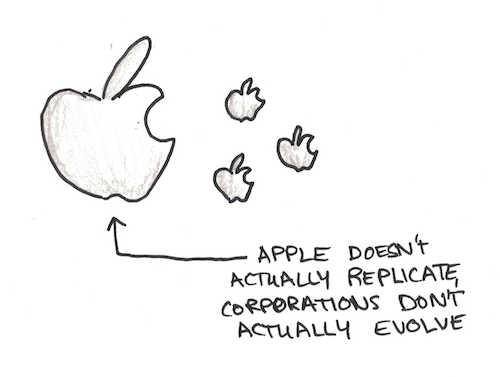

Corporations evolve. They have protocols and products. Those that do well survive and grow. Those that don’t do well go bankrupt. Therefore the growth we’ve seen in companies is due to corporations evolving.

However, if you look through the above list of preconditions, you can see that it can’t possibly be the case that corporations evolve via natural selection. Corporations, for instance, don’t create copies of themselves with high fidelity. Apple doesn’t spawn mini Apple’s that are the same in every way plus a few mutations.

In order to really understand a mental model, it’s not enough to see it in more places. You also have to recognize places it doesn’t apply, even when it seems to. Just because the weird knots on a tree stump look like a smiling face doesn’t mean the tree is happy, and thinking it does just means you understand happiness less.

What Actually Evolves?

A good test of your understanding of natural selection isn’t to just see evolution everywhere, but to ask yourself what, specifically, is undergoing selection?

Many people, when asked about what evolves, will say species. Human beings evolve to beat out other species, rising above apes, Neanderthals and other animals.

This, however, is false. To see why, again, look at the above pattern. What actually replicates? Not species at all. A species doesn’t replicate itself, and so it can’t be the actual unit undergoing selection.

Another tempting answer is to say that individuals are what replicate. You and I are individuals, and so we’re the basic unit that is replicating, mutating, surviving and evolving.

This, it turns out, is also likely false. To understand why, again think to the preconditions. You don’t actually make high-fidelity copies of yourself. Your children resemble you and inherit much from you, but they also inherit much from their other biological parent.

A more correct answer, is to say that genes themselves are the basic object that replicates. Species, societies and even you and I are merely vehicles for the endlessly replicating genes themselves. An individual is nothing more than a collection of genes that survived better by grouping together than by existing separately in the primordial goop.

The implications of the gene-centered view of natural selection are broad, and I’ve discussed them in my book club episode covering The Selfish Gene.

What Else Evolves?

Biological natural selection is the clearest and most unequivocal example of this pattern. However, depending on how strictly we enforce the definition, there are many other places where this idea seems to apply, at least partially.

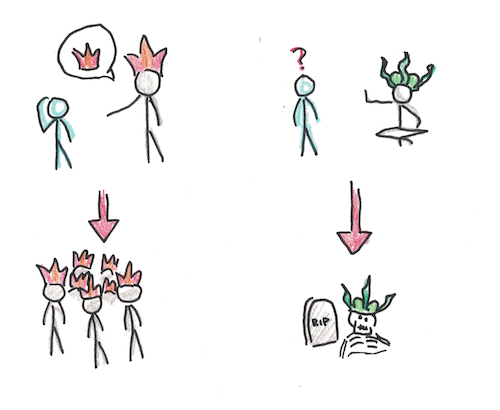

One example is cultural evolution, as proposed by Joseph Henrich. This idea says that human beings are unique because we not only evolve biologically, but our cultural practices work on an analogous system of evolution which happens to be much faster.

To see if this pattern really fits, let’s look again at the core tenets:

Replication: People are expert copiers, in particular we copy people/groups we see as prestigious, often replicating with fidelity aspects of a behavior ritualistically, without a clear rationale.

Mutation: While we’re expert copiers, we’re not perfect. Every once in awhile a behavior will be learned incorrectly. Whole tribes of people have gotten cut off of basic technologies, such as fire, when information about how to make one gets corrupted or lost.

Fitness: Behaviors have different success rates. These different success rates directly induce differences in replication because those less successful die of. In addition, because we tend to copy prestigious individuals, who by definition are more successful, successful behaviors replicate much more quickly than by survival of their practitioners alone.

In this sense, the evolving unit isn’t a gene or individual, but an cultural practice. Henrich argues that we have evolved to expect culture. Our brain, rather than evolving the best behaviors itself, seems to have left open slots where culture can be absorbed. Language, tools, rituals and religions are all part of our cultural evolutionary history.

Cultures may not be the only thing that evolves, via prestige networks. Richard Dawkins, in The Selfish Gene, first proposed the concept of a “meme.” Unlike cultural evolution from copying prestigious exemplars (which would seem to benefit the host), memes can be parasitic, evolving because a certain idea encourages its replication and thus becomes prevalent even if it is neutral or detrimental to the host.

Religions that encourage evangelism, for instance, would have greater memetic fitness, even if missionary work didn’t benefit the individuals themselves. This is because if your religion is best kept to yourself, it is unlikely to spread as far as one which encourages you to convert believers.

Applying Evolution by Natural Selection to Your Life

There’s a few ways you can use this mental model in your own thinking.

First, you can ask yourself whether a system has the propensity to evolve over time. Is there faithful replication? Mutation? Fitness? Then you might have a system which ratchets up towards more successful replicators in the future.

Second, you can also see how this can be used to solve problems that you’re unable to solve through reason alone. Programmers, for instance, can use this directly in the form of genetic algorithms. Create a bunch of candidate approaches, mutate them, replicate them and keep only one that works best, then repeat.

A smaller-scale version might be present in your own work as you learn. Trial-and-error isn’t necessarily evolutionary in the sense that you’re faithfully copying your approach and trying things purely randomly, but it can result in improvements even when you don’t fully understand them.

The post Useful Mental Model: Evolution by Natural Selection appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 28, 2019

Most Books Won’t Change Your Life (But You Should Read Them Anyways)

“If you only put into action half of what you read, you’d already be a millionaire.”

I’ve heard many variations of this advice, all making the point that the problem isn’t that we don’t have good ideas, but that we implement little of it and therefore our lives don’t change, we don’t lose weight, grow wealth, improve our relationships or become happier.

The implication of this advice is that if you read a book and don’t apply it, you’ve just wasted your money. You ought to apply the lessons of what you read, or there was no point reading the book. I disagree.

Why You Ought to Read More Advice than You Actually Use

Reading books is cheap. Kindle editions of popular books cost less than a nice meal. Libraries and borrowing books means you often don’t even need to pay that.

Even the time spent to read a book is a fairly low investment. For almost any topics there are books which are good enough that reading them isn’t a chore. If you get in the habit you can probably easily read two dozen books a year.

Implementing ideas, in contrast, is often quite expensive. Implementing just one idea from a book can take more time, money or effort than reading the book itself. Implementing all the ideas from a single book might take years.

This imbalance suggests that you ought to read a ton of books, and only implement a fraction of the ideas, depending on what you have time for.

If the Typical Book Changes Your Life You Read Far Too Few Books

An idea from economics you should remember deeply is that when you have diminishing returns from an activity (meaning doing more and more gets less effective), then the optimal amount is when marginal cost equals marginal benefit.

To illustrate, imagine a machine that you put in $5 and it spits out money each time. At first it spits out $20 bills. After a while, only $10 bills come out. Eventually only few quarters spit out when you put in your $5. When should you stop using the machine?

Obviously, you should stop using the machine when it only gives you $5 back. That’s when marginal benefit (the amount of money you get each time) is equal to marginal cost (the amount you have to put in to run the machine).

Now apply this reasoning to books. If a typical book you read costs $20 and requires twenty hours to read, but the value is life changing—you’re not reading enough books! You should keep putting in those $20 and twenty hours until books you read are worth about what you paid for them. Any less and you’re leaving money on the table.

I think the vast majority of people don’t read enough books to reach this trade-off point. So the advice to read less until you implement every idea you’ve already read seems foolishly wasteful to me.

Why Unused Books Still Have Value

Contrary to the popular wisdom, I think a book you never explicitly try to implement can still add value. Perhaps not life-changing, but at the very least, enough value to justify the relatively low cost invested in them.

It’s true, most books won’t change your life. But then again, you don’t need a life-changing amount of money and time to consume them. If you pick good books, read them well and think deeply about their implications, that’s enough to earn back their price tag (both in terms of dollars and hours spent).

There’s a few ways books have a lot of value, even if you don’t make a direct habit of implementing every idea:

1. Good books limit bad choices.

Read enough books about investing and you learn enough to steer away from some clearly bad habits on investing. Yes, the nth book you read may not cause you to change any behavior differently from the n-1 books you read before, but the accumulation of books on personal finance can keep you from spending and saving foolishly.

It’s often the things you don’t do after reading a book that justify the investment cost. If a book steers you away from bad strategies which won’t work, that alone can make it worth reading.

2. Reading a lot ensures you have lots of good ideas.

The improvements I want to make in my own life and business often resemble a huge (near infinite) list of things I could be doing. I could refine my exercise habits, optimize a landing page, switch to a new productivity app, etc..

The list is usually far larger than I have time to accomplish. That’s okay. What reading a lot of books does is that it increases the overall quality of this list, so that the ideas I’m working on are better. The more you read, the better the average quality of your list, even if you haven’t set aside time to work on any specific idea.

3. Books change the conversation in your head.

Good books don’t simply act as an instruction manual, giving you a tutorial for changing something specific. Instead, they shift the conversation in your head. Read a good book, and you’ll start thinking about things in a different way.

Sometimes that different pattern of thinking will result in some deliberate plans of action. Other times, they will merely adjust your thinking down a new direction you might not have considered before.

4. Authors can be the friends in your life you wish you had.

If you have one friend who is always perfect—never procrastinates, achieves every goal she sets, eats healthy and has good habits—that probably won’t make you a better person on its own. (In fact, this person sounds pretty annoying.) However, if all your friends acted that way—you couldn’t help but change your behavior.

Books, in some ways, can act like a thumb on the scale of your average social environment. They may not be the same as flesh and blood people motivating you to act, but they subtly adjust your expectations for yourself.

When I started reading books, I found they gave me motivation to do a lot of things that people around me thought were “weird” even though those things eventually led to a lot of good things in my life. If I had tried to implement those ideas spontaneously off of a single book, the impact probably wouldn’t be sustainable.

5. Sometimes, books really do change your life.

Although, on average, most books you read won’t change your life (and if they do, you’re not reading nearly enough books), some books certainly will. Every once in awhile, you’ll encounter a book that will give you just the right idea at the right time and inspire you to make a bunch of sweeping changes.

In this sense, buying books is like buying lottery tickets, each with a small chance of a huge payoff. Lottery tickets tend to be a bad investment because, cheap as they are, the chance of winning is even lower. Good books, on the other hand, are a great one because they’re both cheap and if you read enough, there’s bound to be a few that will change your life.

Want some good books to read? Check out my book club podcast playlist, where I’ve covered some of my favorite in-depth.

The post Most Books Won’t Change Your Life (But You Should Read Them Anyways) appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 27, 2019

Useful Mental Model: Efficient Markets (and the Efficient Market Hypothesis)

Some ideas are so powerful and general that once you learn them deeply you start to see them everywhere. Efficient markets is one of those ideas.

Unfortunately, efficient markets is also an idea that gets a lot of hate. The reason is that the simple logic of efficient markets often leads to conclusions people would rather not accept.

My point of this article isn’t going to try to persuade you that all markets are efficient, but to help you understand the idea. Even if it doesn’t apply because one of the fundamental assumptions is violated, efficient markets still provides a powerful “default” way of viewing complicated human systems that would otherwise be quite confusing.

Let’s dive in…

What are Efficient Markets?

Efficiency is a concept from economics that simply means you can’t make anybody better off without making somebody else worse off.

Consider a world in which Bob has $1,000,000 and Julie has $1. This could be “efficient” because in order to give Julie more money, Bob has to have less. Thus, don’t think of “efficient” as being “fair” but simply that there aren’t any ways to change things to make everyone better without making at least one person worse off.

Now, however, imagine that Bob has $1,000,000 and Julie has a rare artifact. Bob would be willing to spend up to $500,000 to have the artifact. Above that, and he’d rather have the money. Julie would be willing to sell it for as little as $100,000. Below that, and she’d rather keep it.

This state, of Bob having money and Julie having the artifact, is no longer efficient. Why? Because we could simply move anywhere from $100,000 – $500,000 from Bob to Julie and the artifact from Julie to Bob and they would both be better off for it.

This is the power of markets and voluntary trades. It allows both people to be better off than they would be if they couldn’t exchange things.

Supply and Demand

The world has more than two people in it, however. As a result, when we imagine efficient markets we’re usually considering lots of people selling something (say televisions) and lots of people buying them (say television viewers).

People who make televisions would sell more of them if they could get a higher price. If people would buy each television for a million dollars, television manufacturers would want to make a ton of televisions, after all, they cost a lot less than a million dollars to make. New people would start television companies to keep up with the gold rush.

Similarly, people would buy more televisions if they cost $1. You might have four or five in your house. You might throw your old one out and buy a new one every six months. You might give them as gifts when you visit your friends or use them as serving plates. Cheaper prices cause people to buy more.

These two phenomena are known as supply and demand curves. Supply curves tend to curve up, as prices rise, people want to sell more. Demand curves tend to curve down, as prices rise, people want to buy less.

Efficient markets say that the actual price of televisions will be when the amount people want to buy equals the amount people want to sell. At this point, the arrangement is “efficient” because you can’t make anyone better off with further trades.

If people made and sold more televisions, they’d have to sell them to people who want them for less than the amount of money television makers are willing to accept.

Lessons of Efficient Markets

The first lesson of efficient markets is that markets make almost everybody better off. Remember those sloping curves of who wants to sell and who wants to buy?

Like our example with Bob and Julie, Bob is willing to pay much more for the artifact than Julie is willing to sell it. So when the artifact changes hands, the difference between them is what’s known as surplus. Surplus indicates the total amount that people are “better off” by trading than they were before.

It’s possible that Bob is a shrewd negotiator and convinces Julie to sell her artifact for only $1 above her minimum selling price. In which case he captures $399,999 of “consumer surplus.” Julie, is still better off, but only by a measly $1 of “producer surplus.”

Suppose now, that someone came in and forbid anyone from selling below or above a certain price. If this price was above the efficient price, now some people who would like to sell aren’t allowed to sell to some who would like to buy. The arrangement is no longer efficient and we have what economists call deadweight loss.

Monopolies (where one seller sells to many buyers) or monopsonies (where one buyer buys from many sellers) can also create deadweight losses. The price a monopolist wants to charge is usually higher than the competitive price, and so there exist people who would like to buy, but can’t. In these cases, forcing the monopolist to charge the “competitive” price can increase surplus, even if it makes the monopolist worse off.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

With the basics of supply and demand understood, now we can look at an extension of this idea, applied to the stock market.

Suppose I know, with certainty, that Apple’s stock is going to go up. This means that when I buy it now, wait a little bit, and sell it later, I will make a lot more money than I would buying other stocks.

As a result, I go out and buy as much Apple stock as I can, since I can make guaranteed extraordinary profit. The result of this, however, is that the quantity demanded increases, and so the price rises. It will keep rising until the price of Apple’s stock no longer makes it a great deal. If I hold it and sell it later, I won’t make more money than I would buying other stocks, so I stop.

What this dynamic suggests is that prices are self-correcting. If I have secret information that makes something more valuable than its price suggests, I will buy more until the price reflects the correct price.

This is true even if my guess at Apple’s stock price rise is only probabilistically correct. Just like how you can make money from a blackjack table by counting cards, it’s not that each hand will win, but over time you can make money since each bet is slightly weighted in your favor.

Similarly, prices will adjust to the “correct” price, even if people only have partial, probabilistic information about what will happen in the future.

The efficient market hypothesis states that any information about the value of something will automatically adjust the price until the price matches what people think it is worth.

Applications of Efficient Markets

First let’s look at the simple case of efficient markets, without the extension to stock markets and information.

One of the lessons of this case is that price caps and floors are really bad. In a normal market with sufficient competition, setting a price floor makes people worse off.

It’s easy to see this with televisions. If I force people to sell televisions at $100, but there are producers who would like to sell it for $90 and consumers would would buy it for $95, there are trades that could make everyone better off that nobody is taking.

Where this gets controversial is when this logic is applied to things other than televisions. Minimum wages are price floors. This makes those who get jobs better off, but it means there are those who would work for less who can’t get jobs.

The main argument against “efficient” markets here is when we have a monopsony. If there is only one company hiring and many employees, the company may pick a price where people still want to work (because they need to eat) but far closer to their minimum selling point rather than the companies maximum salary they can offer. Like Bob being the shrewd negotiator, employees may be left off with less.

My point isn’t to support or criticize minimum wages here, but simply to point out that most people automatically think of them as good with no downside. Efficient markets suggest that, at least in some cases, they may actually be bad. Whether that’s true in the real world, is a more complicated matter, but the mental model is still useful.

You can similarly apply this idea to restrictions on price gouging, rent control, export quotas and much, much more.

Applications of Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

The efficient market hypothesis takes this idea and argues that it implies that asset prices which are frequently bought and sold will tend towards having the “correct” price.

There tends to be two forms of this hypothesis a “weak” form and a “strong” form.

The strong EMH says that since information corrects prices, bubbles and panics are impossible. If it looks like there’s a stock market bubble, that’s just an illusion because if prices were really overvalued, it would retreat to the correct price. It hasn’t, so prices are correct.

The weak EMH says that prices don’t need to be correct, only that there can’t exist any reliable information to say that they’re wrong. In this case, you could imagine that there’s a new technology. It has a 50% chance of completely revolutionizing the world and a 50% chance of being a total bust. Nobody knows which.

It’s possible that stocks for this company might soar, because there’s a 50% chance that they will become huge. Except, in this version of reality, the technology turns out to be a bust. The prices then crash. This isn’t a violation of the weak EMH, simply because nobody knew which way it would turn out.

Similarly, there’s an even weaker EMH, which argues that prices may be “wrong” but they’re not exploitably wrong. Consider the housing market for a booming city. If half of the people think the prices are going to skyrocket and the other half think they are going to crash, but you can only buy houses, never short them, then those who think it is going to crash can’t “vote” in the market unless they already own a house. This can create a lopsided bet where the price isn’t correct, but there’s still no way to abuse that information to make money.

I’m not sure this weakest version can still be said to be the EMH, but it’s still worth considering.

One straightforward implication of the EMH (in all its strengths) is that it suggests that you can’t beat the market under normal circumstances. You may do so, out of luck, or by taking on extra risk, but you can’t do so consistently, unless you possess information other people don’t have (i.e. insider trading).

Side note: Some variants of the EMH argue that markets even incorporate this “inside” information, so even insiders can’t exploit the market consistently.

EMH also can serve as an approximate guide to things other than stock markets.

The remunerations for a career (pay, prestige, flexibility, fun) must roughly equal its costs (school, skill, difficulty) since otherwise people would gravitate towards that career, competing down the benefits. See an article I wrote applying the mental model of efficient markets to career choices.

Applying Efficient Markets

Each of these implications of efficient markets depends on a lot of assumptions. If the assumptions don’t hold, the mental model may not hold either.

Deeply learning a mental model involves both spotting it as an analogy in the world, as well as recognizing when the assumptions it requires may not be met. It’s totally fine, for instance, to come away from this article realizing that actual human markets don’t approach the efficient ideal. There may be transaction costs, search costs, monopolies or monopsonies, for instance.

Yet, good mental models are still a powerful way to view the world, since when the assumptions do at least approximately hold, they can suggest interpretations that might not be obvious otherwise (like that consistently predicting the stock market to get superior returns should be nearly impossible to do).

Side note: I’m considering making a series, exploring mental models like this one. Do you have any ideas you’d like me to share? To those with economics training, are there any implications about efficient markets I missed? Feel free to continue the discussion in the comments!

The post Useful Mental Model: Efficient Markets (and the Efficient Market Hypothesis) appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 26, 2019

Unpopular Opinion: Don’t Just Get Started

“Just get started,” is the default mantra for all self-help, business books and anyone telling you how to improve your life.

Yet, this is actually a piece of advice I think is more often wrong than right. Contrary to this bromide, I think preparing more is good. Most people actually start projects without much planning, and as a result, sabotage themselves before they even begin.

This idea is so deeply ingrained in our thinking that even when I’ve tried to argue the opposite (that more preparation helps) I’ve had people try to “reiterate” my point by saying that “just getting started” is really what I meant.

Why I’m Against Starting Immediately for Difficult Goals

It seems weird to say that it should be counter-intuitive that preparing for a goal makes success more likely, and yet here I am.

The reasons preparation helps are fairly obvious:

1. Preparing makes your plans better. Better plans are more likely to succeed.

Yes, it’s true that plans often need to change. But you know which plans are even more likely to be changed almost immediately? Bad ones. And you know which plans are bad? The ones that the creators didn’t put more than two seconds of thought into.

2. Preparation is like packing a suitcase. Yes you can buy stuff on the road, but it sucks if you have to buy everything on the road.

Plans will always fail to meet reality. But the more you think about what will be required of you, the more you can avoid common pitfalls:

Are there events in your calendar that will conflict with your plan?

Going on vacation that will make a new gym habit harder? Plan around it.

Are you going to need certain resources? Books, money, materials, access? Planning for some of that will reduce delays and obstacles when they aren’t there when you need them.

3. Finally, preparation is psychological.

Athletes commonly use visualization to prepare themselves for upcoming competitions. There’s tremendous power in imagining something before you have to face it, because then you can be ready to face it rather than panic.

I’ll give a quick personal example. For my 30th birthday I went bungee jumping with friends. Except that, since a child, I’ve always been afraid of heights. As the date approached, I worried that I might freeze when it was my time to jump.

However, I managed to visualize the act of jumping enough times so that when the moment came, I didn’t panic at all.

Side note: while I had visualized the jumping part, I hadn’t imagined the falling part, so that was the moment that was really scary!

You may not be going bungee jumping but life is going to throw hard obstacles at you. Are you mentally prepared for them, or are you going to panic under pressure?

Why People Seem to Be Against Preparation

Listing it out, it seems to make sense that preparation and research are helpful, not harmful for your success. However, if this is obviously true, then why do so many people believe the opposite and put my opinion in the contrarian minority?

The reason, I think is twofold:

People confuse delaying and daydreaming with preparation.

People procrastinate even once their preparations are finished.

Let’s look at each of these issues.

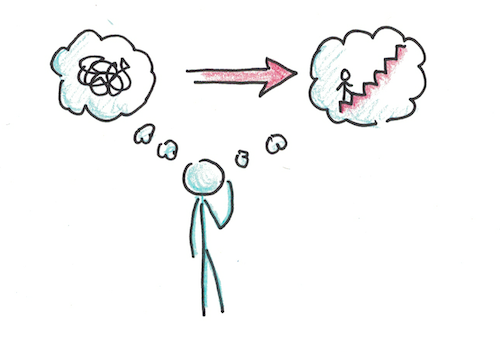

1. Daydreaming ≠ Preparation

The reason the “just get started” advice is appropriate for some is that most people don’t actually prepare for anything. Instead they daydream about it for months or years. Fantasizing what it would be like, or telling themselves they might do something someday.

This isn’t actually preparation though. If you’re preparing it means you’ve actually got a piece of paper in front of you and you’re writing things down. You’re looking into your calendar to fit it into your schedule. You’re doing research online and writing down methods, ideas and strategies.

Actually, when you think of it this way, preparation looks a lot more like doing than daydreaming.

2. Analysis Paralysis

The second problem is that preparation can sometimes feel more comfortable or safer than starting. This can create a risk for when you approach the starting point, hear the pistol fire and completely freeze.

I’ve written about analysis paralysis before here and how you can overcome it. Sometimes the key is to exposure yourself to lower level dosages of the thing you’re afraid of, so you can reduce the fear enough to get started.

Ironically, however, sometimes the key to overcoming this kind of fear is simply to prepare more. If somebody told you to start a new business today the confusion and difficulty might overwhelm you. If you had instead spent a couple weeks putting together a complete business plan and prepared more, the task would feel a lot more doable.

Creating a plan in your calendar, allocating time and mentally rehearsing the act of doing it is often the antidote to procrastination, rather than the cause of it.

How I’ve Applied This Advice in My Life

The MIT Challenge started only after six months of part-time research. For the year without English, it was more like nine months of preparation. Even my shorter projects usually had at least a week of scheduling and preparing before pulling the trigger.

And, yes, sometimes you’ll go through the preparation process and not go forward. But that’s usually because there was a good reason for not going forward. Maybe, once you wrote it all down on your calendar, you realized you weren’t really committed enough to put in the amount of work? Or maybe the goal that seemed super compelling in your mind excited you a lot less when you contemplated the work required?

These are good things to find out early! It’s good to know that you aren’t going to make it before you start, because then you can redirect your energies to something you can accomplish.

How You Can Apply This Lesson

Is there something you’ve been thinking about for awhile but never taken action? Instead of “just getting started” why not actually sit down a little bit and prepare to do something about it?

Write down what you want to do. Look ahead into your calendar and note obstacles and conflicts. Figure out how much effort you can invest, what resources, tools and people you need.

If you find yourself still procrastinating, set a starting date, telling yourself you’ll start on that time, even if your research isn’t complete. And, if you still can’t start even then, go back and prepare a goal that’s a little more manageable to begin with.

The post Unpopular Opinion: Don’t Just Get Started appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 25, 2019

The World is a Hierarchy, Our Theories Aren’t

Natural sciences support the basic idea of reductionism. Sociology reduces to psychology, which reduces to biology, which reduces to chemistry, which reduces to physics.

Things get enormously more complicated with each layer, so that doesn’t mean that knowing quantum mechanics can give you special insight into the next election. However, the basic idea that biology is just a complicated pattern within chemistry and that chemistry is just a complicated pattern within physics, is pretty well accepted among scientists.

Given this strict hierarchy of reality, it’s comforting to think that our knowledge of reality is also a pyramid. Philosophy (or math) forms the bottom, with physics theories on top, then biological ones and so on.

However, strangely enough, this doesn’t necessarily follow from the fact that reality is hierarchical. Knowledge itself is instantiated on human brains and in social institutions. Since these sit at the top of the hierarchy of reality, that implies that although the things physics describes may not need to reference human minds, our theories themselves may be constrained and informed by phenomena much higher up on the hierarchy.

Does Philosophy Say More About Reality or Ourselves?

Psychologists have noticed a lot of quirks of human thinking, that show we’re hardwired to think in certain ways about things that may not always correspond to the actual reality.

For instance, we tend to think of objects and their essences, rather than seeing them as complicated aggregates whose properties arise from simpler parts.

Many “paradoxes” of early philosophy arise because of our all-to-human habit of seeing things as objects with essences rather than complex aggregates. The Ship of Theseus, when taken apart plank by blank, and replaced with new wood, does it stay the same ship? The question is really a non-starter because ships, objects and things (at the level of macroscopic objects) are merely a convenient description, not the fundamental reality.

It seems likely that figure-ground separation is another characteristic quirk of human perception. We are hard-wired to see blotches of light as shapes with boundaries. Insides and outsides. This and that. Black and white.

Machine learning algorithms, designed with explicit analogies to our own nervous system, can be shown as mathematical techniques for creating separations in higher dimensional space. Think of each example as forming a point in space, except instead of just having two or three dimensions, it might have thousands (or millions). The algorithm works to divide up the space into the categories it wants to classify. Insides and outsides. Black and white.

Taking seriously the figure-ground idea of human cognition, therefore, it’s easy to see why we might impose this formulation on the world around us, even when most of the categories we’re actually imposing break down at the edges, rather than form hard lines.

Can You See Things as They Really Are?

The fact that thinking about the world is embedded in processes that are themselves different from the processes you’re thinking about, means that the ideas we have about the world and the world itself are never one-to-one mappings. The former are always simplifications, reorganizations and emphases that exist only on the map, not the territory.

I’ve written before how a lot of us strive to see reality as it is. Would-be rationalists want to see the raw truth, without all the human superstitions and convenient beliefs. Spiritualists want to feel the universe as one, apart from the deceptions of human thinking. Religions, philosophies and thinkers for centuries have tried to grasp at an ultimate reality.

However, it’s likely more often the case that there are merely different ways of conceptualizing the world, rather than the accurate one. Models which leave something out in order to represent something else better.

This may sound abstract, but it’s something you do all the time. When looking at objects, we automatically represent them in 3D—chairs and tables have legs that are of equal length. Yet, when you’re drawing, you need to represent them in 2D. This means suppressing your normal instinct to see table legs as equally long, and instead draw them based on the space the occupy in your visual field. Closer is bigger, further is shorter.

Which perspective is the “true” one? Neither really. Saying it’s a chair with legs is just a convenience. If I smashed it with a wrecking ball, what happened to the chair? It was really just some wood and metal all along. Which were just molecules. Which were just a fantastic number of particles obeying the bizarre rules of quantum mechanics.

Seeing a chair as a 3D object or a 2D one, therefore, can only be judged relative to some context you want to use it. Do you want to sit on the chair (and thus hope the legs are roughly the same size)? Or do you want to draw it, and need foreshortening?

No View is Real, But Some are Realer than Others

The world is, to our best guess, hierarchical. But knowledge isn’t. Knowledge is based on models that are themselves far simpler than the reality they describe. Enormous compressions of information from countless quantum mechanical particles following differential equations, to a few bits of information: chair or not-chair, black or white, inside or outside.

All we have are the models. This doesn’t mean reality is whatever you want it to be. Just that there are lots of different ways you can think about reality. Some will be more useful than others in all cases. Some will be more useful than others, depending on the questions you want to ask.

All learning is really about acquiring more models. Learning when to apply which ones. Integrating pictures so you know to see the table legs as different sizes when drawing, but the same when you want to sit down on them. Knowing when the fuzzy boundaries of one model break down and you need something else to take its place.

In some ways, this model of models I’m describing is not the one we’re born with. Our intuition is that there should be one true way of looking at things, and that the others are wrong. Or, that our models of thinking should collapse into “truer” perspectives the way reality seems to reduce as you go further down the hierarchy.

Our built-in nature is to separate things and make them black-or-white. Since this model of models says that it’s neither true that there’s a “correct” way of looking at things, nor does it say that all ways of looking at things are equally valid. Instead, the model-of-models is a description of itself—there are times when you want to view things in one, “best” way, and other times when you need to choose between different perspectives, depending on the questions you want to ask.

Yet, I think the more comfortable you can get with this unsettling view, the better you can approach learning anything and living in the world. Give up models that don’t work for you. Learn multiple ones that do. Accept that most models are terrible, and aren’t worth learning at all. Yet, recognize that, in many places, it’s only by having multiple models that you can think about it correctly even some of the time.

Also, to remember that this way of looking at things is just another model. What’s going on in your head is actually more complicated.

The post The World is a Hierarchy, Our Theories Aren’t appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 24, 2019

The Best Career Articles

Work occupies much of our waking lives. Why not spend the time to build a career you love, rather than one which makes you miserable? Below are some of my best ideas on how to build a successful career:

The 5 Best Career Articles

I’ve written a lot about your career, but if you’re looking to get started, here are my best five essays on the topic:

If You Want to Be an Author Don’t Start Writing (and Other Strangely Useful Career Advice) – Understanding how your career actually works, not just doing what feels good, is the first step to mastering it.

What Do You Want to Do With Your Life – An older and popular article about trying to decide where to go in your career.

The Interview Method: Why Our Assumptions About Success are Often Wrong – and why you need to test those assumptions to figure out what actually works.

Fantasizing About Retirement? Here’s How to Build a Career You Won’t Want to Quit – Many of us dream of escaping, but work isn’t going away, so you ought to make it something great instead.

You Need to Negotiate Your Lifestyle – Bosses, clients and colleagues aren’t just going to give you the life you dream of, you need to negotiate what you want.

Top Performer

In addition to my free articles on career topics, I teach a course, along with author Cal Newport, on building rare and valuable skills to improve your career. This popular course offers limited sessions, but if you’d like to sign-up to find out about our next one, you can here.

Building Career Skills

As much of my writing focuses on learning, I’ve applied that lens to look at a lot of career problems as well. It’s my belief that mastering rare and valuable skills is the best way to look at your career, and thus I’ve written a lot exploring that topic. Here’s some articles on becoming better at your career:

How to Figure Out Which Skills You Need to Build to Improve Your Career

How Much of Your Career is Running to Stay in the Same Spot – Most of the work you do isn’t going to make you much better.

Capital Trumps Courage – Building skills matters more than being bold, and this boring truth prevents a lot of people from improving.

Why Most People Get Stuck in Their Career

Which Skills Should You Master?

Pick Three Things. Now Do Them Well.

What’s Your Growth Ratio?

How Much Specialization?

Getting Good: How I’m Trying to Become a Better Writer

Should Future Entrepreneurs Go to College?

What are You Going to Be Exceptional at in 10 Years?

How to Network, Find Mentors and Build Relationships

Your career isn’t a solitary activity. Every promotion you get, new job you apply to, or clients/customers you gain will be new people to win over. Here’s how to build the relationships that matter:

Look for Partial Mentors – Finding that perfect mentor who always knows more than you may be impossible. Here’s what to do instead.

Why You Need Mentors (and Why You Don’t Have Them Yet)

What Matters More: Your Network or Your Skills? Why being good may also lead to making connections.

“It’s Who You Know”

Could You Sell Who You Are in 30 Seconds?

How to Meet Interesting People

How to Escape the Toxic Friends Holding You Back

How to Figure Out What People Want

Designing Your Career and Lifestyle

Work/life balance, enjoying work and making it meaningful matter more than just a paycheck. Here’s how to do it:

Bored with Your Job? The Recipe for Enjoying Your Work.

Don’t Follow Your Passion

The Path to Happiness: Do What You Love, Not What You Like

Career Planning and the Dao

How I Became a Full-Time Blogger

Two Ways to Think About Career Fulfillment

Is Getting Rich Worth It?

…and is it important for living the ideal life?

Should You Pursue Your Dream, Even if You’ll Probably Fail?

Is Owning Your Own Business Worth It?

Don’t Follow Your Passion, Do Less to Achieve More and the Magic of the Failed Simulation Effect – My review of Cal Newport’s book.

How to Find What You’re Passionate About (and Get Paid for It)

Should You Wander the World or Build a Home?

Should Your Twenties Be For Work or Play?

More Thoughts on Career

Know Your Competition – Who you compete against matters a lot for what your expectations ought to be.

Some Useful Distinctions When Thinking About Your Career

I Told My Friend Not to Start a Business… Here’s Why

Why the Risky Option Can Sometimes Be the Safest

Why Does Most Career Advice Suck?

What Matters More: Marketing or Mastery?

Day Jobs vs Side Projects – Why working on projects on the side may be better than trying to transition to a new pursuit all at once.

Should You Plan to Retire?

Why I’m Not Trying to Build Passive Income

The post The Best Career Articles appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 21, 2019

Can Life Have Too Much Meaning?

I’m suspicious of those things where more is always supposed to be better. Nature prefers moderation, so good things can harm you when you get too much of them. Drinking more water is good. Too much and you’ll drown.

I think “meaning” is one of those things that is usually good, but that can cause you problems when there is too much of it.

What Meaning Means

Meaning is a slippery word, so it’s hard to be clear we’re using it the same way. However, we all know when a person, thing, goal or idea feels significant to us, and when those same things feel ordinary. The difference is meaning.

In addition to being a feeling, meaning is also an idea. When someone asks you what something means, they’re asking for you to explain it in words. They want its definition, cause or likely implications. Meanings are words and ideas you weave together in your head.

More meaning tends to be better. A complete absence of meaning usually (although perhaps not always) feels awful. Similarly, a lack of meaning in the conceptual sense is confusion and ignorance. We’d prefer to say what things mean and believe it, than to simply shrug our shoulders and say, “I don’t know.”

How Can You Have Too Much Meaning?

I think there’s two ways you can have too much meaning.

First, you could feel too strongly about the significance of something. We’ve all had anxiety and fears when something is so important to us that we’re unable to function. That relationship that you wanted to hold onto even though the other person wasn’t in love with you. That job which meant everything to you—until you got fired. That conviction you held to desperately, until it started to unravel.

Feelings are mental tools. They put our minds into a state that allows certain ideas, actions and thoughts to flow more easily than others. However, to allow some ideas to flow more easily, that must necessarily mean you’re blocking others. The feeling of significance therefore will be useful in some contexts and harmful in others, just like anger, fear, optimism, joy, love, sadness and everything else you feel.

The second way you can have too much meaning is related to the intellectual idea of meaning. If you have a strong set of ideas about what something means, either in terms of its definition, explanation or implied effects, that can “lock” you into a certain way of seeing things. Too much meaning can prevent you from seeing something in another way, and other perspectives may be necessary to solve certain problems.

How to Tell if You Have Too Much Meaning

I suspect that the anxiety and fear we often feel in our daily lives is a result of too much meaning, rather than too little. It’s a combination of a strong feeling of significance, along with a perceived lack of control.

If you follow politics, you may feel like the world is going mad, and that the battles over who leads the country and what policies they implement is extremely significant. Yet, at the same time, you may feel nearly powerless to control the results.

Similarly, in your personal life, there may be situations where there isn’t much more you can do to overcome a problem, but you can’t stop thinking about it. Although people don’t often see their anxieties and fears as resulting from an excess in meaning, it follows that this is the case because if you genuinely didn’t feel the situation was significant you wouldn’t worry about it.

Intellectually an excess of meaning can result in an overly rigid and fixed way of viewing the world. Your ideas, explanations and reasoning about the world is so tight, that you get stuck when you encounter situations that fail to make sense for you.

Is Mindfulness the Relaxation of Meaning?

I have an explanation of meditation and mindfulness and why it seems to be so popular.

Mindfulness, particularly the body-scanning methods popular among Vipassana retreats, are effectively, a way of reducing the emotional and intellectual excesses of meaning.

A common experience when you’re practicing, for instance, is to have a pain somewhere in your body. At first this feels very significant and something that you ought to do something about. After twenty minutes though, the pain starts to turn into something more abstract, perhaps an odd pulsation or throbbing that has changing characteristics.

At one level, I think what has happened is similar to how if you repeat the same word over and over again (say the word “meaning” a few dozen times out loud to get what I mean). By repetitive attention something that would be processed at a level of meaning dissolves into parts that lack that meaning and you start experiencing something that seems to lack connection to the meanings you had previously.

I hesitate to say this is entirely what’s going on with meditation. Many meditators will note the opposite experience: that suddenly the world feels filled with a hidden specialness that was invisible before.

However, I also suspect that this may be a consequence of the thorough de-meaning-ization of your regular experience. Dehabituate your normal filters for processing meaning and new ones will start forming again in the vacuum. Those new ones may not have the same obstacles as the old ones and the fresh perspective may be more enjoyable.

Should You Take Time to “Relax” Your Meaning of Life?

I think meanings, especially intense ones, are an important part of living life well. Don’t confuse what I’m saying for arguing we should all live nihilistically.

Rather, I think what’s necessary is that, from time to time, you are able to temporarily “relax” your meanings in life. This relaxation may be necessary to get out of ruts where your current way of viewing the situation is frustrated and can’t allow you to live your best life.

These meaningness relaxations may be related to specific situations (i.e. how you think about your future career) or it could be more global (i.e. should you find meaning in ambition at all?).

I also suspect that there is no perfect state of meanings, no eternal viewpoint that will be good for all things. Therefore, relaxation of meaning is probably a necessary adjustment that needs to be done every once in awhile. The new meanings you get to may not be any better (in an absolute sense) than the ones you went in with, but they may help you see around obstacles that keep you from living a good life.

The post Can Life Have Too Much Meaning? appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 20, 2019

Decision Making: How To Handle All The Permutations And Combinations

Question: Sometimes it feels like there are just too many choices to make? Every step leads to a million more possibilities? How can you make decisions?

It’s often easy to frame a decision when there are only two options: quit or stay, left or right, more or less.

However, life choices rarely present themselves as a single option. Instead there are countless permutations and combinations of every decision you might encounter. You could go to college or go straight to work, but you then have to decide where to go, what to major in, which classes to pick, and so on. The possibilities quickly become almost endless and it can seem paralyzing to make a decision.

When faced with these kinds of choices, exploring the possibilities can be almost as challenging as making the decision.

Here’s some strategies for handling these kinds of issues:

1. See and experience more.

In face of the near-infinite complexity, our brains simplify. Instead we opt to consider only paths that we see others have taken before us. I’m not sure whether this is because of an evolutionary logic (e.g. the road less traveled is more likely to have tigers on it.) or whether it’s because we can more easily recognize options than invent them (P != NP)

Therefore, if you see more options, you’ll be better able to consider all the implicit options in your life. Travel is a good way to do this, but so is meeting people, saying yes to opportunities that feel outside your comfort zone, reading unusual books and adding more randomness to your life. There more options you see, the more you’ll be able to consider intelligently.

2. Break big decisions into smaller ones.

If you have a lot of options, it often makes sense to try to break them into groups and then make decisions one at a time.

In computer science, there is an algorithm for doing this known as binary search. Essentially you divide the options into two groups, pick one, and then divide those again, continuing until you have the decision you want to make. You may have even played something like this with the number game (where one person picks a number between 1-100 and you try to guess it with them saying “higher or lower” after each guess).

Imagine you’re trying to pick a place to live, you might want to start with asking whether you want to have a big place or a more central place. Then you might consider whether it’s more important to be close to parks or shops, and keep going until you’ve gotten something you’re happy with.

3. Define your must-haves and nice-to-haves.

When considering a set of choices, it often makes sense to decide in advance what your deal breakers are. What are the things that must be there for you to go forward? Which things can you live without?

This is often incredibly valuable for things like relationships, where emotions can temporarily override your needs and you end up picking someone who has completely different life goals or values than you. Similarly, if you are going into a new job, major, city or making another big life decision, you might try to decide what things are must-haves first. Next, you could add a list of nice-to-haves, which would help you rank different options but wouldn’t be a deal breaker.

4. For serial decisions, apply the secretary algorithm.

Some decisions have a lot of possible options, but they present themselves one after another, and you have to say either yes or no to each one, with no going back. Dating can often be considered a version of this problem, where you typically have to consider each person, one at a time, and it’s hard to go back if you change your mind later. Hiring can also be seen this way, where you interview people, but if you wait too long to hire them, somebody else will. Buying a house, living in a city or other life choices can be seen as a line of opportunities one at a time.

For these choices, there’s actually an algorithm you can apply which will give you the best option the highest percentage of the time. I wrote a whole article about it here, but the gist of it is that you wait a certain amount of time rejecting all options, and then after that waiting period you say “yes” to the first option that’s better than all the ones that came before it. In a mathematical sense the optimal point for switching from rejecting to choosing is after you’ve seen a proportion equal to 1/e of all the candidates. In real life, however, the ideal ratio won’t be that precise.

This may sound abstract, but my wife and I used this process when apartment hunting for our new place. We went to see a few places just to get a feel for the overall quality, after seeing 5-6, we picked the first one that was clearly better than all the other ones we had seen before, and we were very happy with our choice.

Not all choices will be clear cut, but if you apply these approaches, you can simplify the possibilities.

The post Decision Making: How To Handle All The Permutations And Combinations appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 19, 2019

4 Actionable Steps To Feel Happy, Content and Grateful

Question: Each one of us would like to be thankful and feel gratitude for all the things that we have today. But why is it so common to only notice everything wrong/missing in our lives? What are some ways to practice gratitude and feel content with what we have?

Our minds were designed by evolution to noticed problems. If you were living out on the Savannah, those who noticed problems (and tried to fix them) or potential problems (and tried to avoid them) lasted longer than those who spent the day being grateful for the sunshine.

The problem is that this attitude of constantly noticing problems and dangers is out of sync with our modern reality. We aren’t going to be eaten by a lion. Yet our minds are still living in a different era.

Gratitude isn’t just a practice of saying thanks. It’s also a practice of shifting your attention away, if only transiently, from the incessant focus on problems and danger and onto the things which are good. However, since our minds evolved powerful problem detectors, but weak gratitude muscles, this shift in attention is rarely an automatic one. It takes a lot of practice, and likely some intervention, to make gratitude a habit.

Here are some helpful tips for implementing gratitude:

1. Start by adjusting your reference point.

We often compare ourselves to other people. Others are in a relationship, we are alone. Others have a great job, we’re broke. Others have admiration and respect, people don’t like us. Yet these comparisons usually lack imagination. They point out how you compare to your imagination of a handful of people near you.

In contrast, I often find it helpful to broaden my scope. Even when things weren’t great in my life, they were still a lot better than they are for much of the world. Even if you feel like you don’t live in great conditions, there were many points in time when things could have been much, much worse. Since gratitude is a relative experience, it’s often useful to recognize how many things aren’t problems in your life, but you just never notice them.

2. Avoid the “Friends Paradox”

The “friends paradox” refers to a phenomenon in sociology where your friends always have more friends (on average) than you do. That’s because, some people will, on average, have more friends than other people, but since they have more friends they will disproportionately be friends with people who have less friends than they do. The result is that your social surroundings always seem to be populated with more popular and social people than you.

This has a lot of implications on our relative perceptions (and thus gratitude) because we get a distorted picture of what’s typical. College students, for instance, frequently overestimate the prevalence of binge drinking and promiscuity, simply because the people who party the most are easier to see. The more typical, boring, student stays and home and isn’t noticed.

The next time you think the average person is better off than you, ask yourself whether you might not simply be ignoring the problems and pains of others, simply because they aren’t as visible as the success people want you to see.

3. Don’t be like the monkeys.

Here’s a video of an experiment involving monkeys. The monkeys like both cucumbers and grapes, but they prefer grapes. You can train the monkeys to do a task which has a nice piece of cucumber as a reward and they’ll be happy to do it. Given one of the monkeys a grape, however, and the other monkeys will no longer accept cucumbers.

We have a hardwired sense of fairness. If we feel like someone else is getting a better deal than us, we’re likely to throw it back in their face.

Yet, sometimes we don’t have control over who gets the better deal. Maybe you worked really hard and only got a B-, while a friend aced an exam without working hard. Maybe your got looked over for a promotion and somebody less deserving got it instead. These are all situations that can make us feel angry and envious. Yet, often we’re acting just like the monkeys—throwing back cucumbers because we suddenly realized grapes were an option.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t fight against unfairness, but that there will always be unfairness in life and so it’s better to step back and see that the cucumbers we get in life aren’t always so bad, even if others sometimes get grapes.

4. Be grateful for your problems.

If you can readjust your reference point and start to imagine the challenges that other people hide from you, that should already do a lot to shift your perspective outside of yourself. Once you have a different perspective, it’s a lot easier to be grateful.

However, I often find it useful to go a step further and not just to be grateful for your lack of problems, but to be grateful for your problems themselves. This can be a tough perspective to adopt, especially if your problems are extreme or tragic. However, the problems themselves allow you an opportunity to live differently than if your life had been without them. The job that stresses you out can also be a source of meaning as you overcome challenges. The relationship that failed can allow you to find something better. Even the tragedies that seem to have no positive side can still allow you to appreciate your life in a different way.

This step isn’t mandatory, but I find it a useful exercise for reframing things and encouraging gratitude.

Ultimately, gratitude is not (and may never be) the automatic pattern for you to think about your life. Our mental hardwiring is simply too strongly pointed towards problems and dangers. However, if you can introduce a little more gratitude, you may be happier for it.

The post 4 Actionable Steps To Feel Happy, Content and Grateful appeared first on Scott H Young.