Scott H. Young's Blog, page 39

April 11, 2019

Book Recommendation: The Hungry Brain

Most diet books are about food. The Hungry Brain, by neuroscientist and obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet, is fascinating because it is about behavior.

The brain, Guyenet argues, is the most important part of the body if we want to understand why we gain weight and how we lose it.

Nutrition is one field I struggle to follow, because there’s a lot of noise. Millions of breathless news headlines scream at you that you need to cut fat, cut carbs, go vegan, go paleo, reduce cholesterol, reduce trans fats, reduce everything. In the end, there’s too much advice, often pointing in mutually opposing directions to make a well-informed decision.

Guyenet’s book was refreshing because it puts the science first: admitting what we don’t know, evaluating what we do, and not offering an easy solution just because that’s the one which sells.

The Hungry Brain is also fascinating because it focuses on how our brain mechanisms regulate eating behavior, and how these can get misaligned in a modern world to cause us to overeat.

We’re Fat Because Food is Too Tasty

If I could crudely summarize Guyenet’s message it would be: we’re fat because food tastes too good.

Tasty, convenient food triggers complex brain circuits that cause us to want to eat far more calories than we need to sustain our weight. This kind of food occurred seldomly in our ancestral environment, and when we did encounter it, overeating was probably an adaptive response. Fresh fruit and honey will spoil or be stolen, so you’d better eat it now.

The problem is that we live in a world where tasty, convenient food is everywhere. Thus the same adaptive brain circuits from our ancestors are now firing all the time.

The challenge that this presents is that, unlike some diets which blame obscure food properties, such as gluten, monosodium glutamate or saturated fats, this puts the blame squarely on how appealing we find food itself.

Given a bland diet, with limited food reward, and overweight research participants dramatically lower their food intake, rapidly losing weight. Give slim participants easy access to junk food and they overeat immensely.

Capitalism and Obesity

A frequently named culprit of our obesity problems is the fast food industry. Giant corporations and restaurant chains conspire to give us ever-fattening food. Often this is blamed on cost-saving measures, say from using GMOs, antibiotics or high-fructose corn syrup.

This narrative would suggest that if we could simply restrain these greedy companies, our weight loss woes would go away.

In the view presented by Guyenet, we might still want to blame capitalism for obesity, but rather than it coming from corporations undermining our true desires, we’re getting fat because a competitive marketplace has been extremely successful in giving us what we really want. What we want are convenient foods which have the high food reward our ancestors craved.

The solution: making food less tasty, or less convenient, is going to be a hard sell. As a result, our finger-pointing tends to obscure this fundamental issue, pretending we can somehow have quick, delicious food, without the costs.

The Brain Circuits that Make Us Fat

Guyenet spends much of the book explaining some of the principle brain circuits that drive obesity.

One of these is the lipostat, centered in the hypothalamus, which controls our hunger levels in response to changing body fatness. Our fat tissues release a hormone, leptin. When we lose fat, this hormone declines, and hypothalamic circuits switch on a “starvation response.” We become obsessed with food, and need to eat a lot more to feel full, until we can regain the lost fat.

A problem with modern diets is that our lipostat will guard very strongly against weight loss, but is rather less effective about causing us to lose weight after we gain weight. As a result, having gained a lot of weight, and rapidly losing it, tends to provoke a starvation response even if the new weight is a much healthier one.

Another set of brain circuits are found in the brain stem. These circuits control the feeling of fullness. More calorie-dense, tastier foods tend to make us feel less full, for the same amount of calories.

Other circuits in the brain respond not only to food reward, but food variety. In this sense, our market economy, with its dizzying array of food choices itself can create a problem. While we may get tired of just eating one food, researchers can provoke overeating by giving full participants access to new food. In a sense, providing the scientific explanation for the intuitive feeling we have that there’s always more room for dessert.

What Should We Do to Stay Healthy?

The Hungry Brain focuses on science, but it also comes with many suggestions for staying in shape:

Eat a smaller variety of food (to feel full with less).

Eat a blander diet.

Make eating food more difficult (through cooking, less fast food or prepared foods).

Avoid holiday overeating binges (which may create a “ratcheting” effect of weight gain over time).

Eat more protein. (Low-carb diets may work through this mechanism, by increasing protein we feel full more easily and it may lower the fatness set point.)

Exercise, while not universally positive (because it can increase appetite) is generally beneficial because it may adjust the amount of body fatness your brain wants to maintain. In this sense, you lose weight from exercising not simply because of the calories burned, but because if you’re overweight, your brain circuits may want you to be leaner, causing you to eat less.

What is interesting about this advice is that it puts front-and-center the modern trade-off. If we’re too fat because food is too tasty and convenient, then losing weight and keeping it off tends to become about making our food somewhat less rewarding or convenient.

Successful diets, whether they be low-carb, low-fat, paleo or vegan, tend to work by indirectly making food less rewarding or convenient. These aren’t negative side-effects of these diets, but the principal mechanism by which they work.

This may not be the message that people want to hear, but it’s the right one. Everyone wants to believe they can be rich without work, committed without constraints or thin without giving up tasty foods. Life, however, is full of trade-offs. Know them, so you can choose wisely.

The post Book Recommendation: The Hungry Brain appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 8, 2019

Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics: Week One Update

Last Monday, I announced a new ultralearning project: trying to get a good grasp of the physics behind quantum mechanics. In particular, I decided to try to tackle MIT’s 8.04 – Quantum Physics I, similarly to how I tackled other MIT classes during the MIT Challenge.

As an experiment, I decided to try livestreaming the entire project. Every lecture I watch, problem set I do, Feynman Technique I try and frustration I encounter is all happening live on camera:

How the First Week Went

In terms of the class content itself, the first week went fairly well. There are 24 lectures and 10 problem sets. By the end of the first week, I have gotten through the first 10 lectures and 4 problem sets.

The pace, however, shouldn’t imply I’ve been finding the class easy. Most of the problem set questions have stumped me without getting hints back-and-forth from the solutions, so it’s clear there’s still a lot of work to be done.

In particular, my prerequisite classes are either missing (I didn’t do 8.03) or rusty (I did do 8.01, 8.02, 18.01, 18.02 and 18.03, but almost eight years ago). So there’s be a simultaneous difficulty of managing the hard QM content, along with refamiliarizing myself with a lot of hard math techniques.

Despite those difficulties, I still think I’ll make good progress towards my eventual goal (a strong intuition about the basics of QM) by the end of the month.

While the class itself has had ups and downs, livestreaming has been much easier than I thought it would be. Part of the motivation for doing this project was to test out the process of livestreaming a challenge where I understand the learning process fairly well.

My Progress So Far…

Day One

Started out by reviewing the first four problem sets (prior to doing any lectures).

Spent the rest of the day doing watching lectures. (Up to lecture 3)

End-of-day debrief.

Day Two

Spent the whole day (morning and afternoon) watching lectures. (Up to lecture 8).

Day Three

Spent morning to finish up to lecture 10.

Spent afternoon working on problem set one.

Day Four

Finished up to end of problem set two.

Day Five

Finished up to beginning of problem set five.

Used the Feynman Technique on understanding group and phase velocity.

The post Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics: Week One Update appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 3, 2019

Should You Fix Weaknesses or Focus on Strengths? Here’s How to Decide

Say you only have time to focus on improving one thing in your life right now, what should you focus on: something you’re good at or an area you’re weak?

Most people will argue that you should focus on your strengths. With books like Strengths Based Leadership and Now, Discover Your Strengths, authors have made a living out of arguing that we should give up trying to fix our flaws and double down on what makes us great.

There’s just one problem with this advice: it often doesn’t work!

This isn’t just because life is complicated and every situation calls for a unique response. Instead, I think the dividing line between whether something is a weakness you should work on or ignore is actually fairly clear and simple.

When You Should Focus on Your Strengths

The logic behind focusing on your strengths is one of specialization and increasing returns to mastery.

Albert Einstein didn’t need to be a good painter, baker or tailor. He could enjoy art, eat cookies and wear suits all made by somebody else. Spending more time trying to improve his pastry-making skills would have robbed him of precious hours to develop general relativity.

Similarly, the value of Einstein’s science came from breakthrougths at the edge of human knowledge. Had he only gotten halfway to the frontier of his day, that wouldn’t be useful. Either you develop new science, or you don’t.

This illustrates the central case for focusing on strengths:

Specialization is possible. Einstein’s muffin baking can be safely ignored.

Mastery matters. Einstein’s success depended on being the best physicist, not merely a mediocre one.

When You Should Focus on Your Weaknesses

The logic behind fixing your weaknesses is one of bottlenecks and inescapable elements.

Suppose, for instance, that Albert Einstein, brilliant visualizer and imaginative thinker he was, couldn’t do math. In contrast to his lack of baking talent, this indeed would be a major failure. For it wasn’t merely thought experiments that led to his success in science, but turning those thought experiments into math that others could put to the test.

The math behind general relativity, for instance, was so fearsome that it took Einstein years to wrap his mind around it. His biographer even argues he developed stomach problems due to the stress. Yet, the math was inescapable. It had to be done or the work didn’t count.

Einstein can’t outsource “doing the math” to someone else because it is intrinsically tied up in his work as a physicist. Similarly, he can’t outsource “communicating his idea” as how would he be able to do it?

This illustrates the central case for fixing weaknesses:

Separation is impossible. Einstein can’t get someone else to do the math.

Weaknesses worsen the whole. If Einstein’s math is bad, the theory will be bad. Failure in one will undermine the entire enterprise.

The Dividing Line Between Fixing and Ignoring Weaknesses

With these two paradigmatic cases in mind, let’s walk through a few questions you can ask yourself to decide if you should fix your weaknesses or focus only on your strengths:

1. Can You Outsource Your Weakness?

Is it possible to get somebody else to work on your weak point? If you can hire, delegate, purchase or abstract away the thing you’re not as good at, this is often a better solution than trying to fix weaknesses.

2. Can You Ignore/Downplay Your Weakness?

Even if a weakness can’t be outsourced, it can safely be ignored. If you’re a writer who isn’t very funny, you don’t need to be comedic in your prose. If you’re bad at math, you can avoid making your career rest on numerical virtuosity.

3. Do You Want to Improve Your Weakness?

Sometimes a weakness is merely an undiscovered strength. It’s often through lack of practice, rather than genuine lack of talent, that our weaknesses hobble us. Therefore, if you actually want to improve your weakness, that might be the best sign to work on it more than anything else.

Of course, the opposite is also true. If you hate working on your weakness, and you more motivated to tackle something you’re great at, that may be a better path to follow. Whether those weaknesses can or should be ignored matters, but perhaps even more is whether you have the will to fix them.

The post Should You Fix Weaknesses or Focus on Strengths? Here’s How to Decide appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 1, 2019

New Ultralearning Project: Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics

A subject that has always confused and fascinated me was physics. When I was in high-school, I liked to read popular physics books like Brian Greene’s The Elegant Universe or Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time.

The picture these books painted was a bizarre world. Space is a fabric. Time curves. Stuff is like a wave—except when we’re looking at where it goes, in which case it turns back into particles. The details are so strange they would be unbelievable as science fiction if they weren’t scientific fact.

Central to this bizarre world is quantum mechanics. These are the scientific tools that, although they seem to defy our intuition about how stuff ought to work, nonetheless offer an incredibly accurate picture of reality.

Can You Understand Quantum Mechanics Intuitively?

Quantum mechanics (QM) is famously a subject that’s been said to be impossible to grok. Even the famed physicist Richard Feynman casually remarked, “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.”

This difficulty seems to be overstated. After all, thousands of physicists, engineers and chemists use QM brilliantly every day. Certainly that practical use doesn’t happen without understanding.

However, it does seem to be the case to me, as an outsider, that QM is very difficult to understand intuitively without knowing the math. Many of the key facts about QM seem unrelated in a casual explanation are simple logical consequences of the equations which govern QM.

Therefore, I feel like my earlier days of reading endless popular accounts of QM always lacked something important. Because there was no discussion of the math, or an attempt to wrap one’s head around it, QM always seemed hopelessly confusing for me.

Ultralearning Quantum Mechanics

Ultralearning is the practice of aggressively tackling a learning project of your own design and choosing. One of the more popular features of my blog has been my ultralearning projects taking on classes, languages and other skills.

Since QM is such a tantalizing and challenging subject, I wanted to see if I could chew off a piece of it in a self-education project. Fortunately, a gap appeared in my schedule that made me think April might be a good time to squeeze one in, so I thought I’d try to tackle my first attempts to get a good grounding in QM.

Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics

My strategy for this project is similar to the one I used in the MIT Challenge. Take an open class from MIT’s OpenCourseware, try to learn as much as I can in a set period of time, and then take the final exam to see how well I learned the material.

In this case, I’m going to take MIT’s first QM class, 8.04 – Quantum Physics I. There are more classes after this one, so my month-long project isn’t going to close the book on this topic, but I’m hoping it will give me enough math so that my intuition about these things is on solid ground. In particular, understanding the basics of QM will also help me with understanding other subjects I’ve had an interest in such as quantum computing, biology and cosmology.

There’s two main changes I’m going to be making compared to my original approach I used during the MIT Challenge:

I’m going at a more leisurely pace. At the peak, my pace was one class per week. I don’t think that’s possible for me with this challenge, both because I won’t be doing it full-time, and also because I expect the difficulty for this class to be higher than the MIT classes I did at that pace.

I’m going to try to livestream the entire process. By doing the entire class live on camera, I’m hoping I can share my thought process behind tackling an ambitious learning goal like this one. While I’m sure most people aren’t going to want to watch me studying the whole thing, I hope recording the whole process will make it easier to give a reference example for some of the learning strategies I discuss on the blog.

Why This Will Be a Hard Class (And Why That Matters)

Quantum mechanics is difficult. However, in my case, that difficulty is doubly so for a few reasons:

I haven’t done all the prerequiste classes. In particular, I’m missing 8.03 – Waves, which is a prerequiste in the series. This means there will almost certainly be some backtracking to learn concepts I’m missing (or need to relearn).

The prerequisites I have done, I did almost eight years ago. There will undoubtedly be a lot of relearning and getting reacquainted with hard math problems and techniques I haven’t used since the MIT Challenge.

Calculus-heavy classes were always a weak point for me. During the MIT Challenge, my best classes were those in computer science. My physics and electrical engineering classes, in contrast, were usually harder. This could be an intrinsic difficulty of those classes, but another reason is simply that my algebra/calculus problem solving skills aren’t as well-practiced as coding was for me.

I wanted to pick a class/topic that I would struggle with, because learning methods don’t matter so much when the subject is easy.

Therefore, I’m going into this class with some trepidation (especially live on camera), but I’m hoping that this experience will be a better example than if I can tackled a subject I had more confidence in.

How Can You Follow the Project?

My plan is to livestream up to six hours per day, five days per week, for a total of thirty hours per week. Tentatively, that’s going to be from 8am-11am and again at 2pm-5pm (Pacific Time), Mon-Fri.

Side note: Although I’ve managed to rearrange my commitments, I still have to work, run my business and keep up with life responsibilities on top of this. Therefore, the schedule may get shifted around if work preempts it.

If you’re interested in dropping in to see how it’s going, be sure to check out my YouTube channel here.

Of course, if you’d rather not watch the entire thing, I’m also going to try to post weekly highlights where I try to analyze how things are going and give some thoughts on tackling hard subjects like this.

If you do join the livestream, you’re welcome to chat with me (you can even learn along with me or help me out if you already know QM!). I’m not sure how chatty I’ll be at this point, because discussion may end up being a distraction. On the other hand, out-loud problem solving and reasoning are often good tools for building an understanding, so it may not matter so much.

One of my goals with this project is to see how doing a project livestreamed would work, so I’m sure there’s a lot of details I have yet to work out. If all goes well, I hope to do more projects like this in the future!

The post New Ultralearning Project: Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 25, 2019

Rapid Learner is now open

Rapid Learner, my popular course teaching you how to learn anything better and faster, is now open for registration (until Friday only):

Rapid Learner teaches a 6-week program designed to build effective learning habits from the ground up. Here’s a brief sketch of what we’re going to teach, week-by-week:

Project. Week one starts by teaching you how to construct a compelling learning project, to organize your classes, professional development or self-education.

Productivity. How to combat procrastination, increase your energy and get more done without the frustration and stress.

Practice. How to convert more of your studying time into the techniques research has shown are most effective for learning.

Insight. Develop deep intuitions of hard ideas and learn tools for making sense of complexity.

Memory. Exploit quirks in how your brain remembers things to store information more quickly.

Mastery. How do you go from a basic understanding to mastery? How do you retain what you’ve learned so it’s not forgotten. The final week will give you tools to turn learning from a one-time event into a strategy that works your entire life.

Whether you’re a student who wants better grades, a professional looking to accelerate your career skills or just someone who wants to learn more, this course is for you.

Please note: we’re going to be closing registration on Friday – March 29, 2019 at midnight, Pacific Time. If you’re interested at all in this course, I suggest checking it out before then.

The post Rapid Learner is now open appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 24, 2019

Why Most Self-Education Efforts Fail

We’re taught a lot of things in school. But oddly, few of us are taught how to learn. This is unfortunate because knowing the effective way to teach yourself things is absolutely essential.

Why Self-Education Matters

Every improvement you ever make in your life will come from learning.

To have a successful relationship, you need to learn how people think. You need to master social skills, communication skills and empathy.

To have a successful career, you need to learn your profession. You need to pick up technologies, stay on top of research and keep up with trends.

To have a meaningful life, you need to learn. Our greatest joys in life don’t come from passive achievements. They come from finding a goal or project and figuring out how to make it a reality.

The more things you know how to do well, the more things you enjoy. We love the things we’re good at, so learning how to learn is really learning how to create more things you love in your life. How might life be different if you were an accomplished painter, carpenter, athlete or writer? It all starts with self-education.

Why Self-Education is Hard

The problem is that most people struggle with learning new things. We tend to learn only the things we were already good at. This creates little bubbles of confidence where we learn, and vast areas we avoid because we’re not sure we can get good at them.

There’s nothing wrong with focusing on learning some things and not others. Time is finite, so it makes sense to pick the things you’re already good at.

The problem with this is that relying on our limited experience makes it a lot harder to learn something you want to face, but don’t feel so confident about. Our personal experiences help, but they can also wedge us into corners where we only feel comfortable tackling certain types of projects, because otherwise the skills feel outside our comfort zone.

You see this with people who claim they’re “bad at math”, don’t have the “language gene”, or are clumsy, uncreative or introverted.

The real truth is probably closer to, “I don’t know how to learn this.”

How to Learn the Things You Find Challenging

I’d like to change this. By compiling research from cognitive science; my own experience aggressively learning things as varied as computer science, languages, art and more; combined with the experience of working with thousands of different students over the years, I’d like to give you a roadmap to learn anything.

The process starts by understanding basic principles of learning. Once you see how learning works, it’s a lot easier to see where you may have made mistakes in the past. Next, move from general principles to specific tactics. These are proven strategies that make use of the principles and allow you to learn more efficiently by giving you more tools for overcoming stumbling blocks.

In Rapid Learner, I cover all of these principles and tactics in detail, but for now, I’d like to just leave you with three:

1. Begin with the use in mind.

The first step to learning well is always to ask yourself “why am I learning this?” In particular, ask yourself in what types of situations are you likely to use the information.

The reason why this matters is that the most effective way to learn is highly dependent on the eventual situation, be it a test, essay, conversation or real-life project.

If you can identify the use, the most valuable thing you can do is to try to align what you’re doing when learning to match what you’re doing when you want to use it. If that’s learning a language to have conversations; have conversations. If that’s programming to build apps; build apps. If that’s learning to pass a big test; practice the test questions.

2. Always understand before memorizing.

Faced with an onslaught of information, many of us resort to memorizing. Every day I meet students who are trying to cram facts, figures, definitions and concepts into their brain in order to pass hard tests.

Learning, however, is much faster when you work with precision over brute force. You’ll remember much more if, instead of trying to memorize, you first seek to understand. Once you “get” something, the act of memorizing it becomes much, much faster.

3. Everything can be learned.

There’s a common emotional reaction to facing a learning challenge that’s above your level. You feel that you can’t possibly learn it. Physics is too complicated and mysterious. Japanese has too many words, characters and confusing grammar to master. You try out some dance steps and trip over your feet.

The right belief to have is that everything can be learned. No matter how complicated it seems, everything breaks down into components which are simple enough even a child could learn them. Learning well involves spotting how those systems break down, so you can always start with pieces that are small enough to handle.

Join Rapid Learner

I’m going to be opening a new session of my six-week course for learning things more effectively, Rapid Learner, very soon. Sign-up here to find out about our next session.

In that course, I’ll walk you through the exact system I use for learning hard subjects, whether that’s passing exams, learning a new language, mastering a professional skill or just learning for fun. I hope to see you there!

The post Why Most Self-Education Efforts Fail appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 22, 2019

The Most Powerful Learning Tool (That Doesn’t Involve Studying)

I’d like to talk about one of the most important things you can do for learning. It’s scientifically demonstrated to have a huge impact on your memory, attention and energy levels. Yet, tragically, it’s often the first thing many people jettison when they’re preparing for a big test.

The Most Powerful Learning Technique

The technique is sleep.

Sleeping 7-8 hours per night has an enormous impact on your ability to learn. Cutting sleep, even for as little as one night, can have irreversible impacts on what you learn both before and after, in your fatigued state.

Pulling all-nighters should be banned from your life as a valid tool to cram information. The costs are simply too high.

Even if you’re not staying up for days on end trying to learn, few of us get the sleep we need to learn at our best.

What You’re Doing When Sleeping

Sleep is not a passive activity. Although it seems like you’re doing nothing but resting, the mind is highly active during your moments of slumber.

Sleep is broken into different discrete phases, mostly falling into two catagories of REM (rapid eye-movement, aka dreaming) and NREM (non-REM, which includes deep sleep).

While your head is on the pillow, your brain is engaging in very important work. This includes:

Allowing glial cells (support cells between neurons) to shrink in size, so that chemical byproducts that result from waking activity can be flushed away with cerebrospinal fluid.

Spindle events, 10-12 Hz electrical pulses, which are believed to play a role in making declarative memories permanent.

Reorganization and consolidation of learned information, possibly related to improving the ability to reason abstractly and extend knowledge to new situations.[1]

One of the first studies to demonstrate the importance of sleep to memory was the 1924 study by John Jenkins and Karl Dallenbach. In it, they compared rates of forgetting over the same time period when subjects were awake and asleep. The results are quite dramatic:

Adapted from Fig I. of original study

Adapted from Fig I. of original studyNREM sleep plays a particularly important role, with sleep researcher Matthew Walker explains:

“Indeed, if you were a participant in such a study [on sleep and memory], and the only information I had was the amount of deep NREM sleep you had obtained that night, I could predict with high accuracy how much you would remember in the upcoming memory test upon awakening, even before you took it.”[2]

Sleeping Pills, Alcohol, Caffeine and More

The importance of natural, healthy sleep (as opposed to merely being unconscious) means that you should be wary about the substances you ingest if you want to get the learning-accelerated benefits of a proper night’s sleep.

Drinking, for instance, is widely believed to help with sleep. Unfortunately, the sedative effects of alcohol also inhibit the memory consolidation effects of NREM sleep.[3] Therefore, a night out drinking can be nearly as bad as a night without sleeping in terms of the impact on your memories.

Sleeping pills also prevent many of the healthy benefits of regular sleep, so they can compound your problems with insomnia and make them even worse. Instead, Walker argues in favor of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, which research suggests should be the first-line treatment, rather than pills.[4]

Amphetamines and other drugs commonly employed by students to achieve higher levels of focus can also interfere with sleep, particularly if they’re taken later in the afternoon. Thus the caffeine you drink or stimulants you think will help you study better may end up making your learning much less efficient.

Even artificial light can delay your circadian rhythm, making it harder to fall asleep at an early enough hour to get proper rest.

What Should You Do Instead?

I recommend a two-fold approach to get the benefits of sleeping, not only for memory consolidation, but for improving your energy, attention, emotional stability and mood:

The first is to recognize that sleep is an active part of learning. Cutting sleep to spend more time studying is counterproductive. No approach to learning should make sleeping less than 7-8 hours per night a part of the plan.

The second is to put a plan in place to sleep better. Even if you recognize that sleep matters, it’s still easy to have your habits fall short of the ideal. There’s a few steps you can do to maximize your learning advantage through proper sleep:

Limit alcohol and caffeine. Better that these happen earlier in the day than later, where they will disrupt proper sleep.

Avoid screens and bright lights after 9pm. This will help you fall asleep faster.

Sleep and wake at the same time every day, including weekends. Switching between late weekend nights and early weekday ones will make it harder to sleep well.

Never sacrifice sleep for more studying. If you really have a lot to learn, you’re better off making use of the sixteen waking hours you have available. An hour sliced from sleep will hurt more than an extra hour with the books will help.

Eight hours per day is the goal. Some people believe they can operate on less. Unfortunately, science says that they can’t, although they can fool themselves into believing they can.

A good way to think of the connection between sleep and learning is like the connection between exercise and recovery for an athlete. Elite performers know that it’s not enough to train non-stop. You need to give the muscles time to recover in order for them to grow stronger.

While the brain is not a muscle, there is an analogous truth about sleep and learning. Without sleep you can’t consolidate what you’ve learned. Instead of forming permanent memories, you’re more likely to overwrite what you’ve learned previously.

Improve Your Learning with More than Just Sleep

If you find lessons like these helpful, you’ll enjoy Rapid Learner. This is my full program for turning you into a more effective learner. I’ll guide you through the step-by-step process you can use to learn anything, whether it’s a language, class, skill or hobby, as effectively as possible

[3] – Ibid. p. 271

[4] – Ibid. p. 285

The post The Most Powerful Learning Tool (That Doesn’t Involve Studying) appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 20, 2019

How to Learn a Language in Record Time

Acing exams isn’t the only goal of learning. Life is full of opportunities for learning things well that will never have a final test.

Learning another language is a goal many people have. It’s also one that many people stumble on. They get stuck, give up and maybe even convince themselves they don’t have the right “gene” for learning languages.

There is no gene, however. There’s only ineffective strategies and good ones.

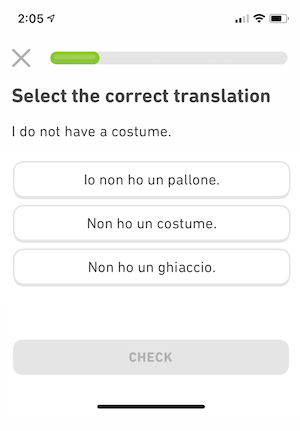

Why I Don’t Recommend DuoLingo

Because actually using a language is so hard in the beginning, its easy to accidentally fall into ineffective learning strategies.

I don’t recommend DuoLingo for most language learners. On the surface, this may seem surprising. The app is slick and well-designed. It has spaced repetition and procedurally-generated questions.

So what’s the problem?

The problem is that the default early-level design of each module in DuoLingo works by getting you to translate sentences by picking words out of a word bank. The problem is that this is nothing like actually speaking a language.

Note, that there is no:

Need to recall the exact word forms, since they can be recognized from the word bank.

Need to ignore similar or confusing words, since those rarely appear side-by-side.

Deal with incomplete vocabulary, where you want to say a word but don’t know it and still need to communicate.

Actual pronunciation and using your lips and mouth to produce the correct sounds.

In DuoLingo’s defense, if you keep drilling a lesson/module, it eventually does start to have more difficult and realistic forms of practice. But my suspicion is that this feature is buried on purpose because far few people would stick to the app if they had to learn it that way.

The Better Way to Learn a Language

A better way to learn a language would have three phases:

Acquiring the minimum basic knowledge and skills to start talking to people.

Having structured, easy conversations in an environment that facilitates learning.

Switching to immersive learning through actual interaction with people (or media).

Let’s look at how you can approach each of these three phases.

Phase #1: Hitting the Minimum

The first goal should be short and achievable—get to a level where you can struggle through your first 15-minute conversation, with the help of dictionaries and Google Translate.

If you’re confident and willing to deal with awkwardness, this could potentially be reached in as little as thirty minutes. This is the approach recommended by Benny Lewis. This counteracts the normal tendency to wait too long to get started using the language. Thus, if you’re bold enough, I recommend diving straight in.

If you’re not so bold, or you tried speaking it and it was too discouraging, you’ll need a beginner learning resource.

Here’s my picks for best resources, in order of priority:

Pimsleur. An older technology, and sometimes a little expensive. However, the thing it does right is that it forces you to recall and pronounce whole phrases from memory. This is exactly the training you need to give yourself that beginner foundation. Just don’t expect it to get you to fluency.

Teach Yourself. These offer a decent overview of the language. Practice is often less automatic with these, but they do provide enough information to start having basic conversations where the real work can begin.

Flashcards. A final strategy is to just use flashcards, from an app such as Memrise or Anki. There’s too many resources to mention here, but the main advantage they have over DuoLingo is that you must produce the whole answer in your head, rather than select them as multiple-choice or from a word bank.

Regardless of what you use, the best strategy is the one that gets you into a real conversation as soon as possible.

Phase #2: Simple Conversations

The next phase of your learning should be based on a mixture of actually speaking to someone and further deepening your knowledge of grammar and vocabulary.

For the first step, I highly recommend finding a language partner or tutor. You can find them at websites like iTalki.com and LiveMocha.co. There are also in-person language meetups through meetup.com (although group meetups tend to be harder than one-on-ones).

Next, you need to start off with a very specific kind of conversation. I recommend having this one in English first. In this conversation you’re going to explain:

That you only want to speak in the language you’re learning (with rare exceptions).

You’re going to use a dictionary and Google translate to fill gaps in your understanding.

You want them to write everything down that they’re saying, if you ask them. Both to help you learn it better, but also to copy into a dictionary to understand them.

You’ll tell them that you know it’s going to be awkward and slow, but you want them to be patient.

This warm-up conversation makes it a lot easier to not fall back onto spending the whole session doing drills, but otherwise speaking entirely in English.

From there, you need to start having conversations. I recommend starting with this being about 25% of your total practice time right at the start (with the other 75% being vocabulary acquisition and grammar practice), and you can slowly ramp up as you feel more confident.

Phase #3: Real Conversations

If you go through this process, it shouldn’t be long before you’re able to have simple conversations about familiar topics that don’t immediately retreat to the dictionary.

Once this barrier has been surmounted, you can start making a more conscious effort to have real conversations. These differ from tutored conversations in many ways (not only by being more difficult), and so having real, immersive practice is essential for really learning the language.

If you were planning an opportunity to travel to a place that speaks the language (or otherwise immerse yourself) now would be the time.

Join My Full Course!

If you find lessons like these helpful, you’ll enjoy Rapid Learner. This is my full program for turning you into a more effective learner. I’ll guide you through the step-by-step process you can use to learn anything, whether it’s a language, class, skill or hobby, as effectively as possible.

The post How to Learn a Language in Record Time appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 18, 2019

Five Scientific Steps to Ace Your Next Exam

Below, I’d like to outline a simple strategy you can use to ace any exam you might have coming up.

Although the specific strategy is my own, the approach is based on cognitive science. In particular, I’m going to look at five key ideas from cognitive science that are easy to miss, but extremely important if you want to study effectively.

The Strategy to Ace Exams

1. When to Study and How Much

The first question to answer is when you should study and how much.

The obvious answer to this question is that you’ll do better the more you study. If you spend hundreds of hours preparing, you’ll do a lot better than if you spend ten, and you’ll do even better than if you do nothing. This is pretty clear.

What’s less clear is exactly how you should allocate your limited studying time.

This brings us to our first cognitive science principle: spacing.

The robust literature on the spacing effect clearly shows that studying time is more efficient if it is spread out over multiple sessions than if it is compressed in one session. More exposures to information, separated in time, will result in better retention than if you cram them together in one burst.

Therefore, your studying schedule should take whatever time you have available and try to be as evenly spread as possible throughout your semester. It’s natural to study a little bit more right before the exam, but you should do this much less than is typical.

The next question is how much to study each piece of information. Jakub Jilek and I recommend that you aim for covering each piece of information (via questions or problems) at least five times, evenly spaced from the time you first encounter them until your eventual testing date. This approach is near-optimal for retaining information with the least amount of effort.

Advice: Keep your study schedule evenly spaced out, with only a slight bump right before the test (if at all). Try to practice each piece of info five times from when you first learn it, until your exam.

2. What to Study and How to Do It

Once you’ve figured out your schedule, it’s now time to look at what you’re actually doing when you study.

This is a place where there’s a vast gulf between what most students think is effective and what actually works best.

Consider one experiment by psychologists Jeffrey Karpicke and Janelle Blunt.[1] In it, they had students in four groups: single review, repeatedly reviewing the information, free recall of the information (meaning you try to remember as much as you can without looking), and creating a concept map (also called a mind map).

Which do you think best?

Before I answer that, let me tell you what the subjects themselves thought. Those who did a concept mapping and repeated review thought they’d do best, with those doing free recall expecting the worst.

What really happened? The exact opposite. Free recall did much better than the other groups, even though the students themselves expected to score the lowest grades.

This result is just one of many from a broad literature concerning the testing effect. This effect says that testing oneself, so you must retrieve the important information from memory, works better than re-reading notes or creating diagrams while referencing your textbook.

Advice: After your first time learning the material, the majority of subsequent studying should be in the form of retrieval practice—trying to reproduce the information, solve a problem or explain an idea—without looking at the source.

3. What Kinds of Practice to Do

There’s a strict hierarchy of what kinds of study materials will be most useful to you in preparing for your eventual exam:

The most valuable are mock tests and exams which are intended to be identical in style and form to the test you’re actually going to take.

Next are problems, given in homework assignments, textbook questions or quizzes, that are given for your class specifically.

Finally, self-generated questions or writing prompts based on the material.

Problem sets from other classes often differ a lot in the scope and expectations, so I don’t recommend using them if your goal is to study for a particular exam.

The reason for this hierarchy of practice is known as transfer-appropriate processing. This basically means that the more your practice resembles the exam, the more your practice efforts will transfer into actual results.

If you don’t have access to high-quality problem sets (as is often the case in non-technical classes), a good solution is to do a writing prompt. Pick a concept, theme or big idea and then try to explain it succinctly and accurately without opening the book. Then re-read it to see if you got it right.

Advice: Always prioritize higher-quality problem sets. Mock exams are best, followed by in-class problems and then writing prompts from big ideas or concepts discussed.

4. Make Sure You Really Understand

Most academic classes are conceptual. This means that passing or failing inevitably rests on whether you understood some important ideas. Memorization matters, but it’s more often as a means to understanding rather than an end in itself.

This means that deeply understanding the core concepts behind any exam you study for should be a top priority.

Practice problems already help with this, since to solve a problem you usually need to understand it.

However, shallow understandings masquerading as deep ones is very common. Psychologists even have a name for this: the illusion of explanatory depth.[2] The reason is that while it’s easy to self-check factual knowledge (you either know it or you don’t), understanding proceeds in degrees, so it’s easy to convince yourself you know something deeply you don’t.

As a result, I recommend the Feynman Technique as a tool for deepening your understanding of core concepts covered in the class. You’ll know something best when you can teach it.

Advice: Identify the core concepts and make sure you can explain them without looking at the material. If you really don’t get something, go back and forth between the explanation in the textbook and your own understanding until you do.

5. Beat Anxiety by Simulating the Exam First

Big exams come with big anxiety.

Anxiety is one-two punch for your studying ability. It’s both harder to concentrate and the stress makes it harder to remember things, even if you could.

The solution is to make at least some of your studying sessions a full-blown simulation of the exam. If you have a few mock exams, I would save these for doing a full simulation of the test—same seating posture, materials and, most importantly, the same time constraints.

There’s three benefits to doing full simulations:

You increase your temporary anxiety while studying, which makes it easier to recall the information due to state-dependent memory effects.

By exposing yourself to the exam situation you’ll be less anxious when the eventual test comes.

You’ll actually know what your performance is likely to be on the test!

Advice: Simulate your exam by doing mock exams (or if you lack those, with other problems) under the same time constraints and conditions of the actual exam.

Learning Better—Beyond Just Exams

I’m going to be reopening a new session of my popular course Rapid Learner. This course goes beyond just learning to pass exams, but how to master skills and knowledge for your whole life.

Stay tuned, and I’ll be providing more lessons drawn from Rapid Learner. After those lessons are done, you’ll get a chance to join in for the full course and get the benefits of learning better your whole life.

[2] – Lawson, Rebecca. “The science of cycology: Failures to understand how everyday objects work.” Memory & cognition 34, no. 8 (2006): 1667-1675.

The post Five Scientific Steps to Ace Your Next Exam appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 14, 2019

How to Know When to Give Up

There’s plenty of great stories of persistence.

J.K. Rowling living on welfare, while writing Harry Potter.

Thomas Edison and his team, attempting thousands of different materials, before eventually settling on tungsten filaments for the lightbulbs that created an industrial empire.

Albert Einstein, failing to find work in physics, dreaming up his revolutionary ideas for physics in the Swiss patent office.

What we rarely hear are the stories whose moral is that the person should have just given up.

But these stories also exist. They’re just not as celebrated, although, perhaps they should be.

Famous Figures Who Should Have Given Up

Consider Isaac Newton. Famous for discovering the law of gravity that unites apples falling and the planets orbits. Yet, he spent years trying to decipher strange numerological codes hidden in the Bible that he thought could give him the recipe for turning lead into gold.

Or what about Elizabeth Holmes and her bogus blood-testing company, Theranos? She had ambition and persistence in abundance. But had she paused to reconsider earlier, she might have readjusted that drive into a product that wasn’t a sham, defrauding investors of billions.

Even Alexander the Great died at an early age because he pushed his empire too wide and thin, rather than stopping while he was ahead.

The Problem with Persistence

Every decision you make to keep going faces a trade-off. On the one hand, by quitting too early and too often, you never get past the hard parts and into the areas where your effort may pay off.

The easy spaces in life, with guaranteed wins for little effort, are crowded. It’s only once you venture past this, where you need persistence, vision and drive, do you start seeing rewards. When things are easy, everyone is doing them, so you want to go where things are hard enough to make it worth your time.

On the other hand, failing to quit is a failure to learn. Sometimes your ideas and vision don’t match reality. What you’re trying to do isn’t going to work, staying stubbornly in the same direction can cost you much more than just pride.

How to Decide Whether or Not to Give Up

I’ve been in a position multiple times in my life where things seem to not be working out, and I have to consider whether I should keep going or give up.

One of the biggest decisions for me was whether to keep writing almost a decade ago. I had been trying to work my way into a sustainable income for myself for several years working part time, and it hadn’t worked out yet. After a particularly bad failure with a project I had worked on, I considered giving up altogether, trying out something new.

In the end, however, I decided to keep going. The twist was that this was only a few months before I finally found the business model that would allow me to earn a full-time income, and I have ever since.

In other cases however, persistence didn’t win out. I started a book club nearly two years ago, but after fourteen months, I wasn’t happy with how the format was working out, so I gave up so I could have time to work on other projects instead.

Between these, there’s been a ton of moments where I’ve had to make judgement calls about whether or not to keep going, and the choice is rarely clear cut. Below, I’d like to outline the decision process I use for making the tough call to keep going or quit:

1. Do You Have an Obviously Better Opportunity?

Decisions aren’t made in isolation. You’re always comparing doing something to doing something else. Even “do nothing” is something, since you’ll fill your time with watching television or hanging out with friends.

A good question, therefore, when you’re weighing whether or not to continue is if you have a clear idea of what you’d do instead. Sometimes a project is hitting a rough patch, but it’s still the best idea you have of how you’ll reach your goals—you just need to push through.

This was my reasoning when I decided to keep writing. I couldn’t see anything else that was a better opportunity at the time, even though I was getting discouraged.

2. What Did You Commit To?

One mental tool I use a lot to stick to hard things is to predefine my commitment before starting. That way, I don’t depend on momentary frustrations to make big decisions to quit or continue, but a different rule of thumb.

This was my reasoning behind giving up the book club. I had started it with a specific commitment to go for one year. After that yearlong effort, I felt it wasn’t what I wanted. The amount of work required to make each one was relatively high (compared to blog articles), the amounts of views for each episode were lower than I’d like, and it was more like a book review than a book club, as most months didn’t have many people other than me reading along with the book.

In this case, however, I was fine with giving it up because I had tried it out for the period I was committed to. If I had been feeling this way at the six month mark, I probably would have pushed forward because six months didn’t feel like enough time.

3. Would Your Future Self Feel Regret or Relief?

This is a hard question, since it depends on imagining your future emotions in a way that isn’t always possible. However, I do like this approach to evaluating big decisions because it makes use of your intuition (as opposed to just your rational mind, which may be inadequate) as well as force you to see above momentary hiccups and focus on the big picture.

If I feel like future-me would regret the decision, I usually commit to a bit more. Pick a spot out, either in time (say 6 months more work) or a certain milestone (after graduation) and push to that spot and reevaluate.

In contrast, if I imagine future-me would feel like it’s a relief, that with more emotional distance I’d recognize that I was in a bad relationship, project, obsession or mindset, that’s probably a good reason to believe that giving up is good. Sometimes we get overly attached to our current plans and fear giving them up for the unknown. But if you expect future-you to feel relief about it, then you’re probably wise to give it up now.

Do You Need to Give Up? Or Just Take a Break?

Fatigue, anxiety and frustration can all put you in emotional states that make it hard to keep going. However, sometimes the problem is just that—a momentary emotion.

If whatever you’re considering giving up is important, and you’ve invested a lot of time already, I strongly suggest starting with a brief break. A semester off school. A leave of absence at work. A vacation to clear your head.

Once you get back to a more neutral mindset, you can reexamine your feelings and see if they want you to get back up and continue the old path, or if the distance reinforces your decision to give it all up.

Whatever you do, recognize that there’s no perfect solution to these problems in life. You’ll always make decisions under uncertainty. The choice is yours to make.

The post How to Know When to Give Up appeared first on Scott H Young.