Scott H. Young's Blog, page 40

March 12, 2019

The Six Morning Routines that Will Make You Happier, Healthier and More Productive

Of all the different things you can try to improve your productivity, a morning routine is one of the most effective.

There are a few reasons why morning routines are so useful. The first is obvious to anyone who has ever procrastinated, just getting started is often the hardest part. If you can start out with the right momentum towards your goals, you’ll avoid wrestling with yourself in the morning to get started.

The second is that the morning, particularly before the workday officially begins, is a quiet time with fewer social obligations. For many of us, the rest of the day can present a chaotic, ever-changing blast of responsibilities, urgent errands and unexpected interruptions. The morning, in contrast, is often the most consistent part of your day.

Morning routines also set the tone for your upcoming day. Do you want your workday to begin quiet and contemplative? With vigorous exercise? Silent meditation? Creative and productive? Your morning habit can push you along a current which will carry throughout the morning and allow you to maximize whatever aspect of your personality you want to be most important.

In this article, I’d like to explore a few different morning routines you can try. But first, let’s talk about what comes before the morning ritual: sleep.

When Should You Wake Up? How Much Sleep Should You Get?

When you talk about productivity, there seems to be two camps. Some argue in favor of waking up extremely early to maximize those early-morning hours. Others say getting enough sleep needs to be the priority. If you can’t go to bed by 8pm, you should wake up only after you’ve gotten 7-8 hours of sleep.

I believe the scientific case is fairly clear: when it comes to productivity, getting enough sleep is essential.

A lack of sleep causes enormous cognitive declines, it impacts your ability to form memories, and may even increase the risk of certain diseases (including cancer). Research indicates that 7-8 hours per day is a nearly universal requirement, so those who claim to get by on four or six hours per night might be kidding themselves.

Worse, the cognitive impairment of a lack of sleep can accumulate, even if you think it has leveled off. Any morning routine you develop needs to accommodate your sleeping rhythms.

Key Lesson: Your morning routine should allow you enough sleep. Pick a time you can wake up consistently and also get 7-8 hours of sleep on a normal night.

Creating the Perfect Morning Routine

I’ve experimented with a ton of different morning routines. Waking up super early, waking up without an alarm, exercise, learning, work and many others.

In all these different experiments, I’ve found that there isn’t one perfect routine that will make you rich, ripped and happy overnight. Instead, there’s different routines for different purposes, and so I tend to think about my routines as trying to match my most important goals of that moment.

If I’m really focusing on health and fitness, starting with exercise or putting in the time to eat a healthy breakfast might go first. If I’m working like crazy, getting straight to work on my most important tasks may be better than cluttering up my morning with different tasks. Different goals, different routines.

Therefore, instead of suggesting one routine, I want to suggest six. These different routines have all served me during different parts of my life, and so you can see which feels like the best fit for you.

The Six Key Morning Routines

1. Exercise and Energy

This routine is simple: right when you wake up you go and exercise. Before eating breakfast, checking your phone and emails or watching some television—go out and move.

I’ve done this before with running, swimming and even just push-ups.

The first benefit of this is that it puts fitness in that all-important first slot of the day. If you’ve struggled with staying on a regular exercise schedule in the past, this can be a good way to make sure it is a priority.

Second, this habit can wake you up. Exercise can keep you alert and mentally functioning at your prime, when a coffee may only be able to slightly prolong your later-day crash.

Recommended for: If you struggle with grogginess, you’ve had a hard time fitting exercise into your schedule and if you want to make fitness your top priority.

2. Meditation and Stillness

Contrary to the first one, this starts with daily meditation. I’ve done this before with 30-minute meditation periods.

It’s important to do seated meditation and not do so lying down in your bed, or you’ll be likely to fall back asleep. I sit on the floor, not a chair, which is not terribly uncomfortable, but also a position that requires enough muscle tension that I’m unlikely to fall asleep.

I’ve found this helpful because it tends to leave me calm and focused. Useful if you expect to have stressful days ahead to start yourself off with a quiet mind.

I also find that one of the challenges of grogginess is keeping your eyes open. Meditation allows your mind to wake up without strain so by the time you hear the final gong you’re fully awake.

Recommended for: If you want to be calm and less anxious in your day, if you’ve wanted to make meditation a priority but haven’t had time, as an alternative if you don’t like exercise first thing in the morning.

3. Get to Work!

The key to productivity is just doing the work. This routine underscores this by making getting some work done your first priority, so that your first break is the chance to eat breakfast, shower, shave and do the normal routine you’d do in the morning.

I did this during the MIT Challenge. I even have old schedules I wrote on paper which had “6:55 – Wake Up,” “7:00 – Start studying,” written on them. I’d wake up, and in five minutes I’d be doing practice questions, listening to the next lecture or working on a programming assignment. Only after I did 30-60 minutes of this would I take a break to “get ready” to start my day.

This works because it not only maximizes your time, it shifts your productivity much earlier. You finish much earlier in the day and can enjoy a less cluttered evening without guilt that you’re slacking.

The second benefit is that you get to take a break when you need it. Too many people take their break before starting, so that when they have to work they can’t take a pause for fear of not having enough time to finish.

Recommended for: If you have important goals and projects that take a lot of time. If you expect to be working a lot and you’re worried you won’t have time to do everything.

4. Learning First

When I was planning my year-long trip to learn four different languages, the early morning was the only time my roommate (who went with me on the trip) and I had to do some pre-travel practice. Therefore, we woke up at 6am each day and did a half-hour of Pimsleur lessons before he got ready to go to work and I got up to start my day.

In other times I’ve done learning goals where I’ve read books, watched lectures, practiced skills or studied first thing. This is often useful for the same reason it’s useful for meditation and exercise: it puts something you struggle to schedule first thing in your day, so you won’t forget it.

Recommended for: When you want to work on an important learning goal but never find time.

5. Plan Your Day

Mental rehearsal is a key strategy elite athletes use to ensure performance. By imagining each movement vividly, they can perform better under pressure when the big event comes.

You can exploit a similar impact by planning out your day in the morning. Don’t just jot down some to-do items, but actually imagine working on them. What will be the complications? Where will you have gaps in your schedule that need filling? What will you need to focus on?

Doing this planning first thing in the morning can be a good way to prime your day for success.

Recommended for: If you have a hectic, busy schedule. If you want to focus your mind on work and productivity, but can’t start working right away.

6. Make Your Bed

Making your bed, brushing your teeth, showering, shaving, doing makeup, pressing your clothes and more are all little tasks that can put you in good form for the rest of your day. Such morning routines were pretty much expected a generation or two ago, but nowadays many people skip out on some of these steps as the culture has become looser.

An advantage of this more traditional routine is that in putting your house and appearance in order, you put your mind in order as well. As one admiral William H. McRaven put it, “if by chance you have a miserable day, you will come home to a bed that is made — that you made — and a made bed gives you encouragement that tomorrow will be better.”

This approach can be taken on its own, or it can be synced up with one of the other two—say fifteen minutes for some key preparation activities followed by exercise, work or study.

Recommended for: Creating a sense of order and dignity in your day. Giving you a foundation of meticulousness and conscientiousness to approach your later tasks.

Add an Evening Routine

Morning routines are great for managing the first part of your day, but they also depend crucially on an evening routine to complement them. If you do decide to aim for an early rising schedule, you need an early-to-sleep routine to match it. Similarly, if you plan to work or learn first thing in the morning, you should plan out your day the night before so you know what to work on.

A good evening routine should minimize blue light (a good rule is to have no screens after 9pm), so that the melatonin circuit that controls your circadian rhythm can start to adjust for better sleep.

I often like to plan out my day ahead of time and either read a book or listen to an audiobook with the lights out for 20-30 minutes before sleeping to make it easier to doze off.

Matched to your goals a good routine is the foundation for success. It can help you become more productive, healthier and happier by tweaking at one of the most consistent and important points in the day.

The post The Six Morning Routines that Will Make You Happier, Healthier and More Productive appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 11, 2019

How to Learn Chinese: 8 Things I Wish I Had Known Before I Started

I’ve been learning Chinese now for roughly five years. Including a burst of intensive immersion during three months in China near the beginning, plus plenty of practice since, I now feel fairly comfortable with the language.

I’m still a long way from perfect fluency, but I’m at a point where conversing in Chinese is pretty easy, I can read novels without a dictionary and I’ve even done some impromptu speaking and media interviews while in China.

Learning Chinese has been one of the hardest subjects I’ve studied, but also one of the most rewarding. I find the language and culture endlessly fascinating, and I fully expect to spend my entire life learning it.

If you’re also interested in learning Chinese, I’d like to lay out some of the things that have helped me. I’d like to emphasize advice or ideas I wish I had heard when I started. I don’t intend this guide to be complete, perfect or authoritative. It’s just what I’ve done, and what has worked for me.

My Advice for Learning Chinese

1. Learn to Recognize (but Not Write) the Characters

My first starting point into Chinese (before I ever set foot in China) was to play around with a huge set of flashcards on Anki called Mastering Chinese Characters. These decks (split into 10) had thousands of cards and covered the most common characters.

Unfortunately, they were taken down from Anki’s website due to copyright issues a few years ago. If you google around for them, there are some still uploaded in different places, but since I think the content was ripped off some other platform, I don’t know if they have a stable home now.

These cards are imperfect (all resources are), but their main advantage is volume. There are so many cards that you can spend a few years with this resource.

When I started learning Chinese, I doubted whether doing all these flashcards was actually such a good idea. Flashcards featured minimally in learning Spanish, which had gone fairly well for me, and I had been coached into believing that learning to read/write at all is something that should happen a lot later into learning Chinese.

In retrospect, however, learning to recognize the characters was a huge advantage. Most words you’ll encounter are made up of the most common 2000 characters or so. Therefore, if you know these characters, you’ll immediately have hooks for mastering any new vocabulary.

This was especially useful for me when I started because I found it very difficult to memorize words by sound alone, especially when there are only differences due to tone. Having a huge glut of characters memorized meant that I could immediately form a mnemonic when I encountered a new word to remember it. (i.e. “Oh, so printer = 打印机 = (make) (mark/impression) (machine)”)

On the other hand, I don’t think learning to write the characters is necessarily worth the hassle. It takes a lot less effort to successfully recognize a character ~95%+ of the time in context, than it does to draw it without a reference. I think being able to know the basics of handwriting, including knowing how to draw ~100 components is probably sufficient for most purposes, since you’ll probably use pinyin entry for typing anyways.

My advice: Get a resource for learning the characters. Make character recognition, meaning and sound a part of your daily study in the beginning until most the characters you see are ones you recognize.

This can be done from the very first day, but may take a year or two to complete, depending on your intensity. It doesn’t need to precede other learning activities, but it will give a foundation that helps with everything else.

2. Practice the Tones (But Don’t Get Stuck on Them)

Tones were the aspect of speaking Chinese that mystified and intrigued me the most when I started. People talk, and by subtle inflections in their pronunciation, they could take one word and turn it into something completely different.

Intrigue, however, quickly turned to frustration as I recognized that I couldn’t hear the tones! I couldn’t tell when someone was saying first tones or third tones, second or fourth, unless they slowed their speech down to a few seconds per syllable.

Doubly-frustrating was that my own tones didn’t seem to work. I struggled intensely with differentiating 汉语 (hànyǔ = Chinese) and 韩语 (hányǔ = Korean), and many times I’d try to say something, people would hear something else.

While pronunciation is important, and so I think it is crucial to work on your pronunciation, in retrospect I let the tones worry me too much.

The problem of listening was mostly solved through increased exposure. Eventually you can start to hear tones in speech with better accuracy, and even start to catch people making tonal mistakes. Producing tones also got better, albeit more by mimicking how native speakers talk than by practicing elaborate tone drills.

From talking to Chinese learners, my sense is that many more get the q/ch, x/sh, j/zh confusions worse than the tonal errors. Even including all types of pronunciation errors apart from tones, vocabulary is still a far bigger problem for most speakers.

My advice: Learn the tones and pronunciation. Especially, learn the tongue positions for unusual sounds such as those in ‘q’, ‘x’, ‘j’, ‘ü’ and ‘r’. However, your focus should be on vocabulary acquisition since this is the biggest hurdle to communicating in Chinese.

3. Graded Readers + Pleco Document Reader are Your Friends.

I care about knowing how to read in Chinese. That’s not everyone’s goal, but it’s a big part of what I wanted to get from learning the language.

Unfortunately, reading Chinese is often an even more daunting task than learning to speak it. With thousands of characters, few pronunciation cues and vocabulary that differs from spoken Chinese, learning to read doesn’t come automatically after learning to speak the way it does in many other languages.

Doing the basic character mastery is an important first step. If you can recognize the characters in isolation with relatively high accuracy, you won’t necessarily know what words they form when linked together, but you’ll do far better than if every second character you see is a new one.

However, if you want to read, knowing characters isn’t enough. You actually have to read.

This too is hard because often native materials are waaay too hard for beginners, and there’s little else to practice with. Here two things helped me immensely: graded readers and, later, Pleco’s document reader.

Graded readers, which are texts written to use a more restricted vocabulary and character base, are good starting points because you can read through them more comfortably without having to look up every second word. I highly recommend the following graded reader series:

Mandarin Companion’s Graded Readers

Tales and Traditions

Graded Chinese Reader

To really read things, though, you need to go a lot beyond just graded readers. This is why I recommend getting Pleco (the most popular Chinese-English dictionary) and buying the Document Reader add-on. This reader allows you to open files and by tapping on words which are unfamiliar, Pleco will automatically translate it for you. This saves an enormous amount of time from trying to copy the character and paste it (or worse, trying to handwrite each one you don’t know to look up a definition).

The document reader can also open web pages, so you can translate anything by tapping on it!

The document reader can also open web pages, so you can translate anything by tapping on it!I used this with smaller documents and short-stories, before reading my first full-length novel Liu Cixin’s 《三体》 (The Three Body Problem) entirely within Pleco. From it, I could easily look up many terms that were unfamiliar and I didn’t need to waste much time.

My advice: Start with character practice. Then graded readers. When you’re bored with those, go onto reading native material with Pleco’s document reader.

4. Immersion Helps a Lot, But Get Some Practice in First.

Going to China early on and spending it in near-complete immersion was a huge benefit to learning Chinese. Not only does immersion give ample practice opportunity, but it connects learning to real life, providing you with motivation to improve your skills.

However, I found Chinese hard enough that even basic things were quite difficult until I had built the proper foundation. I had spent about ~100 hours practicing before going to China, and that felt like roughly the right amount of time to really dive in. My friend who traveled with me did less than that, and I think he struggled a lot more with learning things.

I would recommend putting in 100-250 hours of practice before going for an extended stay in China. I suggest this for two reasons:

You’ll want to go for immersion on Day 1. This is because otherwise an English bubble will form around you which will be hard to break out of. The more prep you have, the easier this is to do.

Getting the foundation is going to make everything you encounter while abroad much easier to remember. Therefore, I think learning efficiency increases with more foundation.

You don’t need to do super intensive practice. Most of my hundred hours were spent doing the flashcards to get a passing familiarity with the characters. If you can do something similar, along with knowing the basic grammar, pronunciation and a few dozen core phrases, you’ll be fine.

My advice: Put in 100-200 hours of practice before your first immersive trip. When you do go–make sure you set strict rules for yourself about when you can speak English, so you don’t get trapped in an English-speaking bubble!

5. Don’t Listen to the Whiners.

Chinese is hard. Tones are hard. Characters are hard. The culture is different and sometimes challenging. But it’s one thing to admit difficulty and another to give into complaining and griping.

I don’t know why, but China attracts a certain kind of masochistic element, of people who live in the country and complain about it constantly. Especially about how hard the language is, and why it’s impossible to really learn Chinese or all the obstacles that make learning it so hard.

This is a terrible attitude to have and totally counterproductive. Having reached a level in Chinese where I feel pretty good now, I can say that, no matter what difficulties you seem to be facing, they will go away with more practice.

Can’t remember the characters? More practice and they’ll be perfectly memorized.

Can’t hear tones? More practice and you’ll spot them immediately.

Can’t get people to understand you? A larger foundation and people will understand you just fine, accent and all.

Find the culture difficult to integrate into? More practice and you’ll be able to slide into situations more and more easily.

Chinese is hard, yes. But practice will resolve all problems.

My advice: Even if it feels like you’ve put in enormous effort and haven’t reached a level you’d like, have faith that more practice will lead to results. Learning Chinese is more endurance than speed.

6. More and Worse is Better.

I often try to talk about efficiency in learning. Isolating which methods are better for memory and for study. With Chinese, however, the problem is overwhelmingly one of insufficient volume of practice.

If you’re new to the language, you’re almost certainly not spending enough time with it. Anything you can do to increase the time you spend speaking, reading, listening or writing is beneficial, even if the quality of your practice doesn’t reach some magical ideal.

This is why I tend to like resources that are flawed, but massive, over those that are perfect but small. ChinesePod continues to be an excellent resource, not because they have discovered some kind of magical pedagogy, but because they have so many podcasts at early levels, that if you just stick to listening them all the time, you’ll learn some Chinese.

Similarly, the Mastering Chinese Character decks have some major flaws. The sentences used are overly formal and not how real people speak. They (stupidly) have a whole set of cards that ask you to name the character based on pronunciation, even though this is a one-to-many mapping, and thus can’t be done in flashcards. Yet, even with these flaws, they cover thousands of characters instead of dozens, and so can keep you occupied for awhile.

If you think about studying Chinese as a volume problem, rather than an efficiency problem, you can change your approach to increasing exposure. How could you make it easier to use the language more and more?

My advice: Always ask yourself how you can do more practice, rather than just “better” practice. As long as you engage in real use at least some of the time, the main goal should be to increase your daily practice.

7. Watch Shows You Already Know, Dubbed in Chinese

Watching movies and television are a real challenge with any new language, Chinese included. A good technique I found for learning other languages was to watch shows I had already seen in English, dubbed into a new language. I watched most of Star Trek: The Next Generation, in Spanish for this reason—I could follow the plot perfectly, even if I missed pieces of the dialog.

This is hard in Chinese. The reason is that few shows are dubbed into Chinese, with most people preferring subtitles instead. Subtitles don’t help much, because you’ll just ignore them to listen to the English.

One exception to this rule is children’s shows. So I was able to rewatch a lot of Dragonball Z (a show I saw as a kid) since these were actually dubbed, as opposed to just subtitled into Chinese.

This is another good way to increase your volume. Watching shows you’ve already seen before helps you stay on the plot while picking up new vocabulary. Once you feel more comfortable, you can watch more new shows, dramas and movies.

My advice: Watching shows you’ve already watched in English (or another language) dubbed in Chinese can be a good bridge to listening to actual television or movies without subtitles. Children’s shows tend to be the easiest to find dubbed versions.

8. Keep at It!

Learning Chinese is a lesson in patience. Thousands of unique characters. Tens (possibly hundreds) of thousands of words. Heck, you’ll also need to re-learn words for nearly every proper noun–every city, famous person or corporate brand has their own Chinese name!

At times, this volume of learning can feel overwhelming. How can you possibly learn all of that?

And yet, if you keep practicing, you learn more and more. Eventually, you find yourself encountering even fairly obscure things enough times to have them memorized. Things that felt overwhelming eventually become comfortable.

I had a conversation with Olle Ligne, who runs Hacking Chinese, a popular blog about learning Chinese. I told him (a few years ago) that I felt like I had gotten out of the beginner phase of learning, and now learning felt like a long intermediate slog, slowly piecing together the thousands of puzzle pieces that is Mandarin Chinese.

Olle’s reply to me was that this phase never ends. There’s always more to learn. Always things you haven’t discovered yet. But even if putting the pieces together takes time, puzzles are fun and this one creates a fascinating picture!

The post How to Learn Chinese: 8 Things I Wish I Had Known Before I Started appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 8, 2019

Do You Have Habits, or Just Commitments?

If you exercise fairly regularly, it’s easy to say you have an exercise habit. Except, maybe you don’t always do the same exercise, sometimes you go running, swimming or lift weights. Maybe you don’t always work out at the same time of day or under the same conditions.

In these cases, even though you exercise regularly, it’s probably more accurate to say you have a commitment to exercise rather than an exercise habit.

A habit is more than just doing something often. To be a habit, a behavior should come with a degree of spontaneity, triggered by a particular context. Habits may require some conscious monitoring (few people accidentally end up at the gym), but the level of conscious effort required should be fairly low.

A commitment, in contrast, doesn’t need to come automatically. It can require a lot of effort and energy, but you do it anyways because you’re following a rule in your head that says you need to do it, so it happens even if it doesn’t always happen automatically.

Which of Your Behaviors are Actually Habits?

To be fair, the difference between habit and commitment is not black and white. Exercising when you’re completely out of shape is a lot more effortful and deliberate than exercising when you do it regularly, albeit not always consistently from the same context.

However, I’m making a distinction between the two because I think it’s fairly easy to think of yourself as having a habit to do X, but what you really have is a commitment to do X. The difference being that, once conscious effort withdraws (or you stop enforcing your rule to do X) commitments tend to be more fragile than habits.

In my own life, for instance, I have a commitment to do fifty push-ups every day. This is like a habit, except I don’t always do it at the same time or place. Sometimes I do them at the gym. Other times before bed (if I forgot to do them earlier in the day).

If I dropped my self-conscious tracking of my push-up habit, it would quickly fall back to not doing push-ups. Even after having done them for nearly a year, I still need to remind myself to do them. I don’t accidentally start doing push-ups.

In contrast, I’ve been working on a different commitment, reading/listening to Chinese for ten minutes per day. This has led to a semi-conscious habit of reading random articles in Chinese on my phone when I have downtime. This is more like a habit, because I do spontaneously engage in reading, even if I also have a commitment to do ten minutes per day.

Can You Make Your Commitments into Automatic Habits?

There’s nothing wrong with having commitments to do something consistently over time, versus an automatic habit which occurs largely without conscious planning or thinking. Once again, there are shades between the two where something requires less effort but still doesn’t happen perfectly automatically.

However, I still think it might be worthwhile to consider what makes commitments into automatic habits, since the latter seem more stable, and, lacking conscious effort to propel them forward, would seem to require only a small degree of maintenance rather than continuous monitoring to get done.

Here are some possible remedies for making commitments into habits:

1. Tighten the link between context and action.

If you don’t always act out your habit under the same contextual triggers, or you sometimes act it out in some circumstances and you act it out differently in other circumstances, you’re less likely to end up with a habit.

Take our frequent fitness example. If you always went to the gym right after work, this is more likely to become a habit because ending work always cues up the behavior of going to the gym. Similarly, if you always go to the same place and do the same workout, the behavioral coupling will be stronger.

This also helps explain why initiating a behavior is the hardest thing to automate. Once you start some set of actions, the contextual cues narrow dramatically and the subsequent behavior is much easier to sustain. Unfortunately, real life often offers a much more variable set of contexts and cues prior to initiating some action, so getting started is harder.

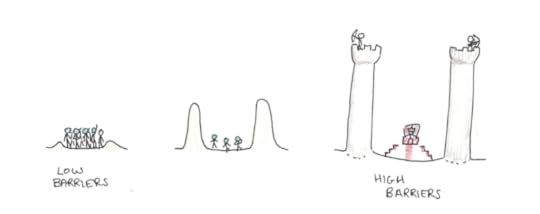

2. Reduce difficulty and friction.

Most habits are meta-stable. That is, they can be sustained with low effort for a time, but they are sensitive to falling apart due to random noise in the environment. Exercising is a meta-stable habit while not-exercising is stable, because the former degrades into the latter when things make it harder to exercise.

Of course, if your habit is easier, more rewarding and has fewer preconditions, it will be more stable.

Some of this is unavoidable. If you want to do something hard, you’ll just have to accept that it’s going to be less stable in the long-run.

However, if your goal is stability itself over accomplishing something of a given difficulty, then lowering the difficulty can make things much easier to do. If you want to read more books, for instance, you might start with books that are fun to read since this will be a more stable habit and will eventually expand your reading skills to handle more complicated works easily.

3. Reduce randomness and noise.

If you can’t make the habit easier, then an alternative is to reduce the chances something from the outside will derail it. This sounds impossible in a modern life, but this is always possible to some degree by choosing when and how you execute the habit.

One way is to work on your habit during a time of day when you’re less likely to face interruptions or obstacles. First thing in the morning or last thing before bed are usually safer times to do something than in the middle of the day, when interruptions are more likely. Similarly, you can do something right in the beginning or end of work, which are more consistent.

I’ve known other people who deliberately make parts of their routine more consistent, ostensibly to make behaviors that go along with them also more consistent. Mark Zuckerberg, for instance, is famous for wearing the same shirt every day, and Warren Buffet drinks Coca Cola with his lunch. These drives for consistency may have different motivations that the one I’ve stated here, but the impact is the same: creating consistent cues can also reduce the chance you’ll be derailed in your habits.

Is Automatic Habits a Reasonable Goal for All Behaviors?

I’m not certain that it’s possible sustain every goal through fully automated habits. Even people I know who are quite devoted to installing habits in their life, seem to use a mix of habits and commitments to accomplish the things they need to.

Many parts of life are just going to be too unstable or variable to allow you to reach a point where all action comes effortlessly.

That being said, I think you can make efforts to shift some of the things you already do regularly in the direction of genuine habits so that they happen with a little less force.

The post Do You Have Habits, or Just Commitments? appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 7, 2019

How to Improve Critical Thinking

Being able to think critically is an essential skill. You need to wade through what everyone is saying and pick out the truth from the nonsense.

Critical thinking isn’t just for detecting fake news, however. You also need it to make accurate decisions. Should you buy a house or rent? Eat paleo or vegetarian? Go to college or drop out and start a company? Each of these decisions is difficult and important, so being able to think critically about them can make a huge difference in your life.

With that said, what’s the best way to improve your ability to think critically?

The Wrong Way to Improve Critical Thinking

I’m going to start with what I believe is the wrong way to improve critical thinking, which is sadly the kind most often taught in schools.

This approach starts by teaching you some basic rules of logical deduction, modus ponens, some examples of fallacies and a whole bunch of Latin terminology that philosophers use.

You work through a few problem sets and, voila!, you’re supposed to be able to reason critically about real-world problems.

While there’s nothing wrong with studying logic and rationality, per se, I don’t think these methods deliver on their intended promise. In particular, there’s a few facts about how our brain actually reasons that make this route to improved rationality a dubious one.

Problem #1: Critical Thinking isn’t a Faculty

The first problem was actually resolved over a hundred years ago by psychologists Edward Thorndike and Robert Woodworth.

The popular view of learning of their day was the idea that human brains contained large, distinct “faculties” such as logic, memory and judgement, and that by practicing them on subjects, regardless of their relevance to the real world, would strengthen these faculties just like lifting weights in the gym improves your muscles.

The problem is that this theory of the mind doesn’t work. The brain isn’t like a muscle. Instead of general, abstract faculties that can be improved with non-specific training, improvements to the mind tend to be extremely specific. General improvements, when they happen, tend to result out of the accumulation of many, many specific improvements, rather than unrelated and general ones.

Consider learning a language. The faculty view says that learning Latin will improve your linguistic faculties. While there’s some benefit of this, most of the work of learning a language is learning specific vocabulary. Thus, if you want to learn Japanese, you’re best off learning Japanese vocabulary—mastering Latin first won’t help too much.

Similarly, critical thinking isn’t just a single monolithic ability that reduces to abstract logical forms. Instead it’s numerous facts, inferences, heuristics and context-specific abilities that must be built up through voluminous exposure to real situations.

Problem #2: Reasoning is Largely Rationalization

The argumentative theory of reason, which I covered in depth here, suggests that the seeming failure of many types of human reason are misinterpreted because they don’t recognize reason’s true function.

Instead of a general-purpose way of making better decisions, reason is a faculty for generating explanations and evaluating those of others. The intelligence comes from throughout the brain, via mostly intuitive modules which are specific and trained through practice, rather than some mystical faculty that does critical thinking.

If this theory is correct, then another reason critical thinking is hard to improve is that we’re mostly not coming up with more intelligent decisions when we think critically, but trying to create more appealing arguments for our positions (or more incisive attacks on the arguments of others).

While this form of critical-reasoning-via-debate has great benefits for our collective knowledge, individually it doesn’t help quite so much. Instead, critical thinking when used alone tends to be more of a tool for justifying your intuitions rather than methodically evaluating them to make better decisions.

The Right Way to Improve Critical Thinking

So if the classic view of critical thinking is wrong, what’s the right way of doing it?

I think there’s two broad approaches that will work to make better decisions:

The first is creating a context that will lead to better decisions, in light of what we know about human reasoning already.

The second is to absorb lots and lots of knowledge about the world and integrate it through practice making decisions—in other words, critical thinking comes from being smart.

Strategy #1: Creating Contexts that Enable Smart Decisions

This first strategy is to recognize what you’re actually doing when you’re reasoning about things and uses this knowledge to try to avoid making common mistakes. Given what we know about how reason works, there’s a few things you can do:

1. Examine the decision in multiple times, places and moods.

Since reason tends to be more to justify than to generate the right judgement, one way to avoid making mistakes is to reason about the same problem in a lot of different contexts.

The modular theory of mind says that rather than a single coordinated function, the brain consists of a lot of semi-autonomous modules that all “vote” their preferred action into the brain. Depending on which module is more strongly activated by the context around you, its vote will get higher weight. So if you’re hungry, scared, angry, sleepy, joyful or sad you may get different inputs into which decision is correct.

Therefore, reasoning about a decision in multiple moods, places and settings will give you the greatest variety of backdrops to reason about things. If the decision is the same each time, you’re can be more confident that you have the correct assessment.

2. Talk to more people and have more debates.

The argumentative theory of reason suggests that reason doesn’t work very well alone. However, it does work brilliantly when combined in public debate. Many well-known problems of human reasoning disappear once you get a group of people together and let them talk about it.

Discussing your decision or judgement with others is a good way to see your ideas refuted or let stronger ideas win the day. Although there’s a risk of group think and conformity pressures, if you take a large and diverse enough group, you’re more likely to be exposed to the best reasoning, which will tend to win out over the majority opinion.

3. Don’t stake your reputation on your choice.

One of the biggest challenges to overcome in critical thinking is that you may not properly update your beliefs in the face of new evidence. Old beliefs may cling stubbornly to their prior position, even once you’re shown to be wrong.

Part of this may be because, in an argumentative theory of reason, we are trying to justify our intuitive beliefs rather than argue against them. Therefore, if you’re only looking for why you’re right, you naturally ignore why you’re wrong.

However, another big part might be the social consequences of flip-flopping on your position. If your reputation and identity is staked on an idea being right, you almost certainly won’t update sufficiently when you’re exposed with reasons that undermine your views.

I’ve tried to counter this tendency in myself by writing about when I’m wrong. By sharing these inversions of beliefs, I’m hoping to separate myself from the content of my ideas, so that I can discard the ones that don’t work, rather than cling to them for fear of looking foolish.

Strategy #2: Be Smarter and Know More

The second approach to improving critical thinking which actually works is to simply learn more about the world. The more you know about things, the better you can reason about them.

I recently had an experience of this when someone told me that they were worried the wifi signals from their phone might cause cancer.

I explained that this doesn’t make any sense. Wifi signals are microwave radiation (and phenomenally low power). Cancer is caused when DNA is damaged. For that to happen, radiation needs to be energetic enough to break molecular bonds. Ultraviolet radiation is strong enough to do this (which is why you should put on sunscreen), but visible light is not (which is why you don’t need sunscreen indoors). Microwave radiation is an even lower frequency than that, so it can’t cause cancer.

The problem wasn’t that this person didn’t have good critical thinking skills. It’s not unreasonable to assume a new technology might have unstudied consequences (including causing cancer). If you heard this from a friend who you think is pretty smart about other things, that’s not a terrible way to make a decision about the risk.

The problem instead was that this person didn’t know enough about electromagnetism to see why this claim didn’t make any sense. If they did, they should be much, much more worried about all the lightbulbs outputting higher-frequency visible light at higher power every day than the faint beam of microwaves put out by the phone.

Critical thinking, therefore, doesn’t happen because you’ve studied some abstract logical form and come to valid deductions. It happens because you know enough about how the world works to rule out certain possibilities as being unlikely or impossible.

The downside to this is that it means critical thinking can’t just be picked up by taking a few credits in college. It means you need to be learning constantly, about all subjects, in order to make intelligent decisions.

The upside is that it also means much smarter decisions are possible. Far from just being an abstract faculty you either have or you don’t, critical thinking is part of the process of knowing things to begin with, and that you can get better at it by learning more throughout your life.

The post How to Improve Critical Thinking appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 6, 2019

Stupid Advice: “You’ll Never Be Rich Working for Somebody Else”

I’ve run my own business, first as a sole-proprietor for nine years, then as a corporation for four. I’ve earned a good income in that time. It’s allowed me to take on interesting projects, travel full-time and work whenever I want.

To many outsiders, it looks like I’m living the fantasy you see on so many “earn money from home” scams advertised online.

Despite all this, I absolutely hate the advice that comes with the saying, “You’ll never be rich working for somebody else.”

This is a little phrase that gets thrown around in some corners of the internet, which glorifies entrepreneurship over employment as a means to wealth, freedom and happiness. The implied advice is that working for somebody else is a sucker’s game, and that if you want to really live, you need to start your own business.

Why This Advice is Dumb

This is terrible career advice.

Don’t get me wrong. I love running a business, and I would recommend it to someone who has the right drive to make it work. But the idea that entrepreneurship is the best route to wealth and freedom is stupid.

For starters, the advice doesn’t even make sense. Many of the richest people I know earned all of their money working for other people. Accountants, doctors, engineers, CEOs and financiers. All working for others, all stinking rich.

Second, even if we ignore that the advice is literally false, the assumption—that entrepreneurship offers a better path to wealth than working for others—is bad economics.

Supply and Demand (or Why Get-Rich-Quick Doesn’t Work)

All career choices are pushed by supply and demand, just like any other purchasing decision. If a career choice is really attractive (because it offers a lot of money, for little effort, low talent and is highly prestigious) it will get a lot of new entrants. Those new entrants will increase competition, push the payoff down, and it won’t be so attractive anymore.

Suppose, for a second, that starting a business really did offer a lot more money for less effort and with fewer barriers to entry than working at a job.

What do you suppose would happen?

Obviously, more people would start businesses! Those businesses would compete. Some might succeed, others might fail. The end result would necessarily be that the average payoff to each new entrepreneur would shrink down until it was no longer so lucrative.

Economists call this stable level of profit that you should earn as a business normal profit. It is contrasted with economic profit, the kind of profit you earn when you’re a monopoly or can otherwise prevent people from competing against you.

Even though you might think to yourself, “all that means is I need to make a monopoly!” this reasoning still doesn’t work. Everyone chasing those rare unicorn start-ups also create more competition. Since the prize is bigger if you win, it’s also more fierce before you get there, meaning that the average payoff is reduced.

Why People Don’t Earn the Same Amount

This kind of logic might seem to go too far, however. If it were true—wouldn’t all professions pay the same amount?

However, there’s at least three mediating factors that explain why some people earn more than others, even though we can expect the above reasoning to hold:

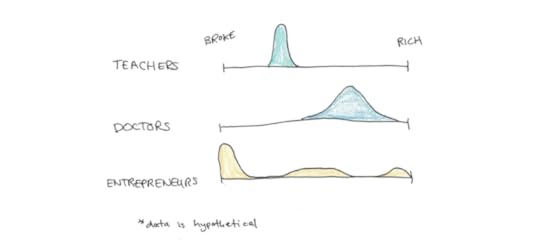

1. Some career choices have a higher variance.

Some professions have a very narrow range of possible incomes. Being a public school teacher, for instance. Others have huge ranges, say launching a start-up.

This is a problem with assessing entrepreneurship because it has much greater variance than normal professions. This means you will see some people get really rich. However, what you don’t often see, is a lot of people making zero or negative money (once you count the cost of their time and investments).

A risky-profession might return a little more on average, because people tend to be risk-adverse. But all that means is that people would rather have a decent income as a certainty, rather than a random chance at poverty or riches.

2. Some career choices offer other (non-monetary) benefits.

Some careers are sexy and prestigious. Others have legendary job security and great pensions. Others will guarantee you an impressed look at dinner parties when you tell people what you do for a living.

Money isn’t the only thing people want from a career. Therefore, the more sexy, cushy, prestigious or secure your job is, the more people will want it for a given amount of income. This is why construction workers can often out-earn college instructors, even though the latter is much harder to get—people would rather teach at college than work on a construction site—even if the pay is worse.

3. Some career choices require more talent, connections or credentials.

The final differentiating factor are barriers to entry. Sometimes these take the form of barriers due to ability. A supermodel might be a good job to have, but most people can’t apply. Connections and credentials also form barriers that make it harder for you to succeed.

Medicine is an excellent example of a lucrative profession that remains well-paying, despite being a desirable job for non-monetary reasons and offering relatively secure wealth. It’s hard to get through medical school, and most people are either not smart enough, patient enough or have the means to endure years of training to becoming a doctor.

Once you factor in variance, non-monetary benefits and barriers to entry, you should be able to explain most (if not all) of why some careers pay more than others.

Why This Analysis Doesn’t Look So Good for Entrepreneurship

So let’s take our above analysis and apply it to entrepreneurship. It’s higher variance, certainly. That means some people will win big and others will win nothing (or lose money).

It’s an attractive profession. Most people would love to be their own boss. If anything, this makes entrepreneurship a somewhat worse way to make money (on average).

Finally, the barriers to entry are typically low. Although being able to start a business in some industries really does have high barriers, those are not typically the industries most people consider when making the kinds of stupid statements I’m disagreeing with above.

This analysis seems to hold out fairly well when you consider the evidence.

Entrepreneurs, as a group, do not out-earn their peers. According to a literature review done by the Copenhagen School of Business, self-employed entrepreneurs have “significantly negative” returns, following their choice. Incorporated entrepreneurs show only a slight positive return, even though this career choice requires more ability, connections and capital.

Not Just Entrepreneurs… But All Professions

This type of analysis, however, doesn’t just apply to entrepreneurs, but to every profession.

The risk-adjusted, expected income of any profession, accounting for net non-monetary benefits and barriers to entry, should be roughly equal. There may be temporary exceptions to this, as the labor market takes time to adapt to changes in the overall economy, but these shouldn’t last forever.

Side note: Jobs in tech, like programming, engineering and IT, may be those temporary exceptions, with the explosion in those fields outpacing the ability of people to transition into them. However, there might be a simpler explanation: people either dislike tech enough (non-monetary downside), or lack the ability to succeed in tech (barrier to entry), that benefits will remain high.

If this isn’t true, however, we should expect either the income of the profession to lower over time due to competition, or for more barriers to be erected by those inside the field to preserve the return of the jobs (increasing credentials/licensing required).

This doesn’t mean getting rich is impossible. Effort, acquired skills, connections, credentials and other career assets can all push you into spaces where you are able to enter niches with higher rewards and less competition. But it definitely does dispel the notion that you can get rich simply by avoiding working for someone else.

This also doesn’t mean that the choice of career doesn’t matter. Some careers are naturally harder and more restricting than others. Being a janitor will usually pay less than being an accountant, because there’s only so skillful you can get at cleaning things up that people are willing to pay extra for.

In short, you want to pick a career which matches your level of ability and drive, so that you can achieve your full potential.

You also want to match your career to your values, depending on how much you care about status, money, security and other benefits compared to other people.

Finally, you want to invest as much as you can into building skills, experience, connections and other assets that will allow you to do things others can’t. This is the only stable way to have a successful career. The rest is just luck.

My Own Experience

I love running a business. I think it is challenging, interesting and can be a great career path. However, I definitely don’t feel like it’s the easiest possible way to make a lot of money.

I feel like I have made a decent living, and one that has reached a semi-stable state (although still with a lot more variance than most employees would experience). Getting to this stage, however, is no different than working in any other demanding field. I had to put in enormous amounts of upfront work to build career assets first.

If you, also, feel like you’d like to take on a career that’s quite challenging, requires an enormous amount of effort and involves more variance than a typical profession, entrepreneurship might be right for you. If you think it’s an easy way to make a lot of money without working hard, someone’s been fooling you.

The post Stupid Advice: “You’ll Never Be Rich Working for Somebody Else” appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 5, 2019

How to Be More Ambitious

Recently I got an email from a reader asking how he can become more ambitious. He feels like he could do more with his life, but he doesn’t have strong desires for the usual sorts of things that seem to motivate people: wealth, success, fame or prestige.

I thought about this question a lot, because in some ways it’s semi-paradoxical.

It’s perfectly normal to want things (e.g. “I want to be rich”). It’s also normal to not to want things you’re unlikely to obtain (e.g. “I wish I weren’t so hungry right now”). But it’s odd to want to want something you currently don’t. It almost feels like asking for an itch so you’d have something to scratch.

My suspicion is that this question conceals a more complicated intent. The person who is asking to be more ambitious does want something. He wants approval, an interesting life or the feeling he imagines would come with a great ambition.

The problem is simply that he doesn’t have much drive for the usual objects of ambition (fancy cars, prestigious credentials, etc.), and so, seemingly, can’t get the motivation to pursue the things he really does want (an interesting life, social acceptance, etc.).

Should You Be More Ambitious?

There’s certainly an argument that ambition is socially beneficial. Scientists who sacrifice their entire lives in the pursuit of a Nobel prize might benefit humanity more than one who was predisposed to taking Saturdays off. Inventors who toil, hoping to make it big, may create the next breakthrough when a more contented person might maintain the status-quo.

Whether ambition is a positive externality or negative one depends a lot on where it is directed. I believe in earlier times, when technological spillovers were low, being more ambitions usually just made you more cruel. Napoleon, Julius Caesar and Genghis Khan all had enormous ambitions—but they did so mostly by killing thousands of people.

I tend to think the incentives have aligned so that ambition is more often positive than not in today’s society. Capitalism, for whatever it’s flaws, tends to reward people for doing things that other people value. This isn’t universally the case (Bernie Madoff certainly had ambition), but it seems more likely than in pre-modern times.

However, I’d like to put aside the supposed virtue (or vice) of ambition on a societal level, and just focus on the personal case. Forget whether ambition is good for the world or not, and just ask, is it good for you? If it is, is it possible to cultivate more ambitions?

How to Cultivate More Ambition

Let’s go back to our story from the start. This person doesn’t feel like he has ambition. But, it’s clear that’s not because he doesn’t want anything (people perfectly content with things rarely complain about it). Rather, the problem is that he doesn’t seem to have much interest in the intermediate products of his ambitions that seem to drive other people.

In this sense, his self-perceived lack of ambition isn’t really a lack of ambition, but a frustration that there doesn’t seem to be any available path for him to reach the things he wants in life.

Thus, I think the question of cultivating more ambition is more about redirecting the feelings you already have, so that they are less frustrated and more fulfilled, rather than generating desires you don’t actually feel inside.

I can see a few possible approaches to resolving this problem:

1. Widen Your Ambitions.

Some people struggle with this because they have an overly narrow conception of what they ought to strive after in life. Maybe their parents told them they need to study hard, get a good job, have 2.5 kids and buy a big house to be a success in life. Maybe society doesn’t care about the things they find most interesting.

In this sense, a lack of ambition is really that what you think of as ambition is overly constrained. Maybe you don’t want to go to school right now, but you’d rather travel the world, make art or have a great social life.

Your ambitions should be tuned to creating the kind of life that you want. Not the life that other people want for you. Widening the scope of what things you could orient your life around may free you from some of the frustration you experience when you can’t bring yourself to strive after the things other people push upon you.

2. Get Onto a Positive Feedback Loop.

Another possible reason for lacking ambition might be, again, not the total lack of desire, but because all your intermediate paths seem to be surrounded by large walls of negative feedback. These reduce your motivation to pursue things, but also cut you off from the bigger picture life you still crave.

A good example of this might be school. You didn’t do terribly well in school, and every class is a struggle. Yet, you know you need to graduate if you’re going to pursue a career you’ll find interesting. Thus you’re stuck—between your long-term desire to have an interesting job and your short-term frustration with school.

The only way out of this seems to be to tunnel a new positive feedback loop. This isn’t easy to do, but it can be done with sustained effort. A positive feedback loop is one in which the difficulty of the task is lowered enough that you can surmount it and build more confidence. From confidence comes competence and so you can slowly get to a point where the barrier of frustration is reduced.

You may not become a brilliant scholar overnight, but if you worked on your dislike of studying by setting up easier tasks and accomplishing them, you may reduce the frustration enough that graduating becomes possible and you can reach your further goal.

3. Get Started, Let the Ambition Come Later.

In some ways, the problem of a lack of ambition is like procrastination. You know you need to do something to get a bigger thing that you want, but you don’t have the inertia to get you going.

In these cases, the problem might simply be that you need to move forward along a path, even if you don’t find it terribly inspiring, so that you’ll pick up motivation as you go along. This is part of the career advice of Cal Newport in his excellent book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, where he argues that passion is overrated and tends to follow behind being really good at something rather than precede it.

If you see it this way, ambition is more likely to result once you’ve already put in some time and gotten good enough at something that you start to get better opportunities. Bootstrapping this process is tricky, but the idea is to just start by showing up and eventually you’ll be good enough that you’ll enjoy it, given more time, that skill will translate into opportunities.

It’s Okay to Want Less

All of this discussion started on the comment from a reader who complained about his lack of ambition. I took it for granted that this was a problem that needed solving.

However, what if you genuinely don’t have much ambition and don’t feel deprived because of it? Should you be scolded into working harder, sacrificing more for some long-term goal?

Again, whether ambition is virtuous or not depends a lot on the context. But, from a purely selfish aim, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being less ambitious. There are many ways to live life and many possible values to hold. Those who obsess and toil constantly for a big dream, and those who live quietly and contently with things as they are. It’s up to you to decide who you want to be, not for me or anyone else to dictate it to you.

The post How to Be More Ambitious appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 4, 2019

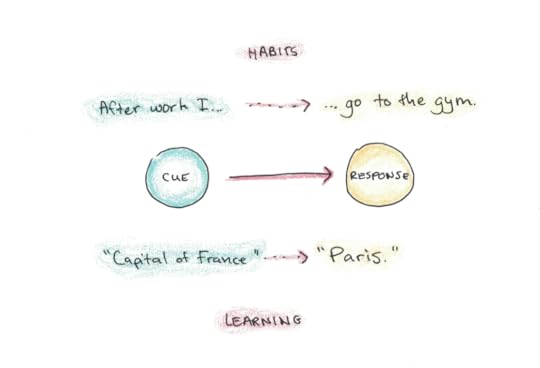

The Hidden Connection Between Habits and Learning

Learning and habits seem like to separate facts about our psychology. Learning is about knowledge, information and skills. Habits are about routines, behaviors and actions.

However, I think the two actually work on mostly the same principles of the brain, and recognizing this connection can help you both learn better and form better habits.

Learning = Habits

To see the connection, let’s start by asking what a habit is. A habit is a semi-automatic behavioral response, given a certain set of cues in the environment. In other words, when you say you have a habit you mean something of the form “Whenever X happens, I do Y.” Examples:

I go to the gym every day = “Every day after work, I go to the gym.”

I don’t eat meat = “Whenever there’s meat in something, I don’t eat it.”

I have a reading habit = “Whenever I have free time, I tend to read (as opposed to something else)”

Informally, habits can be more complicated than a 1:1 association. A regular exercise “habit” may, in fact, be multiple such associations of varying complexity, for instance:

“When I plan my day, I always put in exercise.”

“If the day is nearly over, and I haven’t exercised yet, I exercise.”

“I go after work, except if I have other activities, in which case I go in the morning.”

Although some habits are actually just a simple cue and response, most are complex, dealing with specific sub-cases and having rules for certain situations that get embedded so they work most of the time. A habit doesn’t need to be 100% coupled to count, either. A voracious reader may not have a habit that says “whenever X happens, I must read,” but simply a tendency to read more when there’s spare time.

Learning, it turns out, is almost exactly like this. To learn something means you produce some kind of response (mentally or physically) when given a set of cues. Examples:

I know the capital cities of every state = “When state X is mentioned, in context of asking for the capital city, I produce the correct city, Y.”

I can speak Chinese = “When someone speaks to me in Chinese, I produce an appropriate response.”

I can ski downhill = “When I’m falling down on my skis, my body automatically produces the motor actions that will get me to the bottom safely.”

This may sound hand-wavey, because these examples are so much more complicated and nuanced than simple habits. But as I mentioned before, habits are also often quite complicated, with varying responses for different situations and sometimes only probabilistically so, rather than a completely automated response to a situation.

Conscious Control Versus Automatic Action

One seeming difference between learning and habits may be that applying what you’ve learned is a more conscious process, whereas a habit is thought to be mostly automatic.

An expert painter, for instance, doesn’t just splatter paint on autopilot. Every stroke is a deliberate effort to achieve a particular result. This deliberateness seems the complete opposite of habits, which are defined by their level of automaticity.

While this seems to be the case, I’m also inclined to believe it’s more a superficial difference than it first appears. Even in simple habits, there’s often a great deal of flexibility about how to execute it. Take something like exercising every day: should you go in the morning or afternoon? Run or lift weights? Push yourself or take it easy?

Of course, a habitual action tends to have a strong default (otherwise it wouldn’t be a habit), but this too is similar to learning. When you encounter a familiar problem, the overriding tendency is to apply the techniques you’ve learned before. To solve a problem in an original way takes effort the same way that breaking out of a habitual groove does.

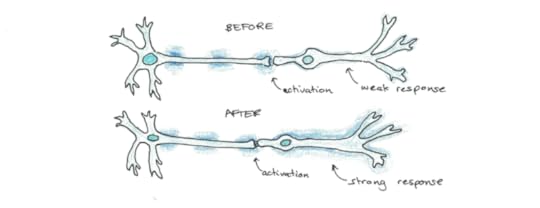

The Neuroscience of Learning and Habits

There’s a lot we don’t understand yet about both learning and habit-formation in the brain. But a common principle to both seems to be selectively strengthening the connections between neuronal circuits that lead to the desired output, and weakening incorrect or spurious connections.

A habit forms when a sequence of neurons fire forms a strong connection with downstream synapses and thus when the earlier ones fire, the later ones fire with a high probability. Think of this like a river carving a valley into the ground, so the water flowing downhill will be exceedingly likely to follow a certain path.

Learning happens when associations of one long-term memory become tightly coupled with another. This can be as simple as a cue-response: “Q: What is the capital of France? A: Paris.” or it can be as complicated as solving a differential equation by having the forms of the differential equation automatically flow to the mental actions that begin to solve it.

While there is likely quite a bit of nuance in each of these broad categories, my suspicion is that they overlap considerably, rather than being largely separate domains. Some forms of learning are encoded as motor sequences (such as learning to drive a car), some habits are encoded as associations between higher-level abstractions (such as remembering to write down to-do items when actions are discussed in an office meeting).

How to Use this to Learn Better (and Make Better Habits)

By seeing learning as similar to habit formation, you can start to view learning not as the process of storing information, but of preparing actions in particular contexts. So learning a language isn’t just storing vocabulary words, but learning to activate certain knowledge, in response to particular situations.

Once you see learning as cue-driven and context-based, as well as something that is trained like a habit (through repetition of the pattern of cue-response), then you’ll be much more likely to practice in a way that will eventually be useful. You’ll be able to spot inefficient learning designs when you recognize that the habit you’re creating isn’t the habit you actually need.

While it is true that you can’t anticipate every detail of a situation, it’s easy to recognize, for instance that a fundamental habit of mind which is useful when speaking a language is being able to think of an idea/concept and come up with the associate word in the language, but that picking that word out of a wordbox isn’t probably the habit you need (like in apps such as DuoLingo).

Similarly, you can improve your habit-formation by seeing it more like an act of learning. Rather than see your habits as being simple units, you can see that you’re trying to create flexible responses to a whole host of situations, all of which need to be conditioned separately. An exercise habit isn’t just going to the gym every day, but finding the appropriate response for all sorts of varied conditions (the gym is closed, you’re feeling sick, you forgot your running shoes, etc.)

By seeing habits-as-learning, you recognize that what you’re doing is not simply a matter of self-discipline, but also of exploration, experimentation and trying to create patterns of behavior that produce useful responses in situations you can’t quite predict. This takes time and practice, rather than simply being an act of will to execute.

Above all, by seeing the connection between learning and habits, you can see how much of your life is made up of similar patterns. Your thoughts, emotions, relationships and identity also operate on similarly practiced loops of cue and response. See the patterns, and you can start to change them.

The post The Hidden Connection Between Habits and Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 1, 2019

Who Has Time for Hobbies?

One of the bigger lessons I got from reading Cal Newport’s recent book, Digital Minimalism, was the importance of scheduling your leisure time.

Scheduling time for hobbies may sound unnecessary. Aren’t those the things you do for fun?

Yet, I would wager that most of us have activities we’d like to do on the side but never seem to have time for:

Learning a language

Art

Sports and activities

Reading for fun

Creating something

A common way to look at this state of affairs is to argue that we don’t have time for these things because we’re too busy. We want to relax at the end of a hard day, with whatever meager hours are left over.

This idea assumes we mostly use our time wisely, and if there isn’t time for something at the end of the day, it must be because there wasn’t time for it to begin with.

Where Does Your Free Time Really Go?

The view put forth by Newport in his book is that we tend to invest a lot of our time on various, low-value leisure activities that neither give us meaning or much enjoyment. Think television, Netflix, video games, social media and web surfing.

These activities often don’t provide much value, but they have really low barriers to get started. That combined with carefully engineered reward mechanisms keep them occupying our attention for many hours in the day.

In this view, it’s not that we don’t have time for high-quality pastimes because we’re too busy. Rather it’s because the default is to do something less worthwhile. If we could momentarily push ourselves out of these bad habits and onto something else, we’d be happier overall.

The solution is simply to schedule time for activities you care about.

How I’ve Been Applying This Idea

There’s two ways I’ve been working to integrate this idea more in my own life:

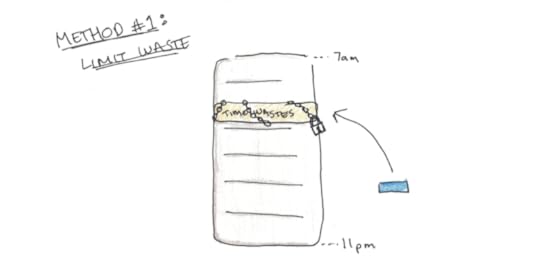

The first is to set strict limits on internet and television use, outside of a few high-quality areas. Right now I have LeechBlock configured on my phone to block my biggest time-wasting websites if I use them more than an thirty minutes per day total. I also have ten minute blocks on my iPhone per day for YouTube and other apps that I mostly use to waste time.

Thirty minutes per day is still more than enough time to follow everything I care about.

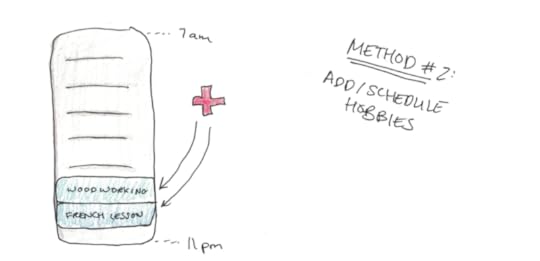

The second way I’ve been trying to integrate this idea is proactively scheduling time for higher-value hobbies. Making a goal to do some activity every evening, Monday to Thursday, whether it’s learning salsa, painting, attending a Chinese language meetup or going to the gym with friends, makes me less likely to fall back into binge-watching old television shows before going to sleep.

What If You Really Don’t Have Time?

The idea of scheduling hobbies tends to provoke one of two reactions:

The first comes from people who don’t like the idea of putting in effort to have fun. Why should you schedule fun–shouldn’t it be spontaneous?

However, I think the problem is often that there are barriers to starting activities you’d find really meaningful and enjoyable in your life, so the path of least resistance is usually not the most satisfying. Scheduling is just one way to avoid this trap.

The second reaction comes from people who argue they actually don’t have any time for hobbies. They’re truly too busy to do any of those things, since they work eighty hours per week, have seven kids and are studying for a dozen exams.

It’s hard to respond to this second objection because, there really are people in such a situation. You may even be in this situation yourself.

However, I also know that some of the highest-achieving, busiest people I know, nonetheless put in a lot of time in high-quality leisure activities.

Do You Really Lack Time, or Are You Just Stressed and Tired?

This suggests to me that the feeling that you have no time is often a reflexive evaluation about the amount of stress and exhaustion you experience to do the things you have to do in life, rather than an objective assessment about the number of hours per day you have no choice over.

My guess is that for most people in this situation, if you did a timelog, you’d find there’s lots of “wasted” time, and that your self-assessment mostly reflects the fatigue and stress you feel.

However, if it truly is fatigue and stress, rather than genuine lack of time, then that’s all the more reason to invest in high-quality hobbies. It’s the meaningless web surfing and Netflix binging that can make your life feel like a complete grind. Creating, learning, adventuring, socializing and experiencing are ways to reduce that stress and fatigue.

Therefore, paradoxically, I think it’s often the very people who claim they cannot possibly schedule their hobbies that need to do it most.

The post Who Has Time for Hobbies? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 26, 2019

Why Memorize?

Is memory redundant?

After all, the world is just a Google search away. Who needs to memorize facts, dates, terms and definitions when you can pull them up in less time than it takes to wrack your brain to remember them?

Some argue that just as teaching cursive or long division is becoming antiquated, so to is our scholastic obsession with memory. Why should we encourage people to memorize things if they’re so easy to look up?

Your Mind Outside Your Brain

An interesting idea from cognitive science is that of distributed cognition. Basically this suggests that your mind, as a system that processes information, may extend beyond the reaches of your skull.

This sounds crazy, but it’s actually rather simple.

Consider a calculator. When you want to multiply two long numbers, you could try to do this in your head using your internal cognitive tools for manipulating symbols and following the procedure you mastered in grade school.

Alternatively, you can pick up a calculator, put in the numbers and get the same answers. Although this calculator isn’t part of your brain, it could be seen as an extension of your mind—an externalized cognitive procedure for calculating things.

Similarly, notes function like externalized memories. In ages before paper, great orators mastered complex mnemonics to memorize great speeches verbatim. Now we just write them down, the paper substituting for our built-in memories.

Given this concept of externalized cognition, it’s worthwhile to ask why we bother trying to remember so much in the first place? If we can write it down or look it up, doesn’t that effectively mean the same thing as if you remember it personally?

Spreading Activation, Modularization and Why Brains Still Matter

The problem with this line of reasoning is that while a calculator does function as a piece of external cognition, it’s much more separated from our brain than other brain regions are from each other. In computer science parlance, we can say that the calculator and your brain are two very separate modules that communicate via a much more limited interface (the buttons on the calculator and the calculator output stream).

While the brain is likely modularized to some extent, it has a lot more interconnections than this, and therefore each module likely has much richer representation and feedback to other modules than you do with your calculator.

In terms of memory, this can have big implications.

A central idea in how brains store memories is that of spreading activation. This occurs when one idea suggests another, which suggests another, which suggests another. This spreading out (which may not be entirely conscious) enables us to locate memories.

However, if your memories are located behind a Google search, they can’t participate in this network effect.

The problem, therefore, isn’t that using a Google search to look up a fact is inherently wrong, but that very often you won’t even think to look something up. Not being in your mind, the correct question to search for may not even form, so there’s nothing for Google to reply with.

What Does it Mean to Understand?

There’s less consensus as to what it means to “understand” something, in strictly neurological terms. Part of this is because what we mean by understanding itself is somewhat ambiguous. As the problem of explanatory depth shows, we often mean very different things by “understanding” depending on the context.

Regardless of whether a specific definition of understanding can be found, we can at least say that to understand something means to have some kind of flexible representation of it in your mind. You should be able to ask many questions and get a good answer about a thing you understand, versus something you simply memorized.

Here, however, gets to the heart of why remembering things in your brain still matters. While Google can substitute for poorly understood, memorized facts (what date was the Magna Carta signed?), it cannot easily substitute for the flexibly represented ideas that have deep understanding (why was the Magna Carta signed?).

As Google searches and easily accessible translations, definitions, calculations and algorithmic capacities increase, we’ll need less memorization. But, what’s left over is more understanding, deep knowledge that requires the spreading activation between many different concepts stored in memory in flexible ways.

That deeper understanding, however, is built off of a lot of memories actually stored in your brain. Ironically, the changes wrought by modern technology may require us to remember more, not less, as shallow recitation of facts gets replaced by deeply remembered ideas.

The post Why Memorize? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 25, 2019

Life’s Wicked Problems (and How to Get Past Them)

Wicked problems are problems that are, “difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize.”