Scott H. Young's Blog, page 38

May 14, 2019

Some Things That Have Helped Me Worry Less

I worry about things more than I’d like to.

I worry about making mistakes, getting criticized, having my business fail, being awkward or rude in social situations and lots of other things.

Most of the time my worries just stay in my head. They’re there, but I ignore them well enough to get on with my day and keep working.

Other times, those worries grip me and derail my progress. I struggled immensely with big parts of writing my upcoming book. My own expectations (and imagined attacks) made starting the writing portion of each chapter a strenuous chore.

I don’t think my level of anxiety is unusual or extreme. I don’t get panic attacks, and I haven’t had anxiety debilitate my life the way it does for many. That said, I’ve tried a lot of things to make it easier. Here’s what’s worked for me.

Things I’ve Done to Worry Less

Most problems in life are stubborn, rather than complicated. Thus we tend to spend our lives fighting against the same problems over and over. Progress is possible, but at the same time, our old foes are rarely completely vanquished.

Overcoming worrying isn’t a trivial issue. But it there are strategies you can use to lessen the impact.

1. Don’t Own Your Thoughts

I’ve found meditation helpful, not so much for the actual meditation itself, but for the idea of what meditation tries to accomplish and to apply the same abstract principles to my ordinary life.

One of the core ideas of Buddhist philosophy is anatman, or not-self. The idea essentially boils down to reviewing everything in your conscious experience and recognizing that you don’t have control over it.

It’s easy to see your thoughts as part of yourself. Something you create and control. It can therefore be frustrating when you can’t help yourself from worrying.

Another way of looking at it, however, is that thoughts just happen. They are a sensory experience, not part of you. Thoughts comes from inside your head, but otherwise they’re as much under your control as what you see, hear or feel from the outside world.

Denying ownership of a thought gives you a choice not to grab onto it. Just like how you might have an annoying sound in the background and choose to ignore it because there’s nothing you can do, you can similarly have a distracting, negative thought and choose to do nothing about it.

This approach is different because most of us spend our time trying to “stop” ourselves from worrying (which makes it worse), or try to “solve” the worry by imagining a way to avoid the threat. It’s easy to forget that there’s a third option: do nothing.

2. Get Off Social Media.

Facing down your fears is good. But there’s a difference between healthy exposure to things that give you anxiety, and indulging in a non-stop download of algorithmically-optimized information designed to trigger your threat response.

Twitter is my vice of choice. I love being able to engage with smart people from around the world on interesting topics. More than once I’ve learned fascinating new things. But the platform is also a nightmare for throwing up things that make you feel angry or anxious.

I now believe that resiliency must be matched with choosing appropriate environments. Mute the people and sources that make you feel worried. Especially if those are the people on “your side.”

3. Identify Your Acute Anxieties, Face Them Head-On.

Not all anxieties are recurring. You may worry that you said something weird to that person one time, and forget about it a few days later. Others, however, have consistent themes and show up again and again.

One of mine is definitely being criticized for my work or projects. Over the last thirteen years I’ve said and done a lot. A lot of the things I’ve said or decisions I made have probably been wrong. Thus, anyone with an axe to grind against me would have plenty of material to make an attack.

This worry has often been stoked by seeing highly-public cases of someone having their career ruined because of a relatively innocent mistake. I remember puzzling over the downfall of Jonah Lehrer, whose sky-rocketing writing career was torn down over misquoting Bob Dylan. I agree he made some mistakes, but the punishment didn’t match the crime.

Although I can’t simulate a career-ending mistake without making one, I’ve tried to attenuate my own fears of criticism by going out and reading it. When I do, the attacks are rarely as bad as the ones I imagine. Even from people who hate me (one guy even created a website saying why he hated me), the reality is usually easier than my imagination.

Your fears may be different. It might be failing a big test, getting fired or being humiliated. Seeking mild exposure to those things you fear is often the only way to diminish their intensity.

4. Stop Trying to Solve It.

My friend, a clinical psychologist, told me that one of the big mistakes people make to deal with anxiety is seeking reassurance. You worry, so naturally you want to talk to someone who will tell you everything will be okay.

While this does make you feel better for a short time, it actually makes it worse later. By “rewarding” your anxious mental patterns with reassurance, you strengthen this pattern of behavior through negative reinforcement.

Similarly, you can have the same issue when trying to “solve” your worries. If you’re have anxious thoughts about someone humiliating you at work, you might fantasize your comeback.

The alternative approach, suggested by my friend, was to resist the temptation to find a way out of your problem. It will make your anxiety worse, but because there’s no “resolution”, the pattern that led to your anxiety is reduced.

This model suggests that anxiety is a motivation with a clear purpose. That purpose is to identify threats and formulate solutions to them. When the goal of this feeling is frustrated, the response is weakened for the next time.

Ask if a Worry is Actionable, Not Rational

I got an email from a reader who also struggles with anxiety, and said that although he can see from a distant perspective that many of his anxieties are irrational, he can’t so easily separate the legitimate worries from the ridiculous ones when they’re afflicting him.

A behavior that is bad 100% of the time is much easier to break off as a habit than one which is beneficial some of the time. When you quit smoking, you can go cold turkey. When you want to quit overeating, you can’t stop eating food. Similarly, some anxiety is probably a good thing. But too much can be crippling.

What this reader wanted to be able to do was to figure out which fears were rational and which were not, in the moment, so as to ignore the irrational ones.

You can’t separate out the “rational” worries from the irrational ones.

Most of your anxieties, even the ones you should have less of, do have a rational basis. The things I fear are not things that are totally without merit, although I should probably worry about them less than I do typically.

Instead of asking whether something is irrational, ask if you should change your behavior. When a worry can’t change your response, it’s not helpful, even if it might be rational.

The post Some Things That Have Helped Me Worry Less appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 13, 2019

Do You Need to Be Smart to Learn Certain Subjects?

How does being smarter change how you learn things?

While definitions of intelligence vary, and the models behind what makes some people smarter than others vary even more, a common view says that intelligence is likely linked closely to having a better generalized working memory.

Working memory is essentially the ability to hold multiple ideas in your head at once. Think of it like the workbench of your mind, where different pieces are assembled together into new ideas. For a primer, check out Jakub Jilek and my extensive guide to the science behind working memory.

Under this view, those who are smarter have a bigger workbench. Thus patterns are easier to spot because more pieces of the puzzle can be put together at the same time.

How Intelligence Differs from Knowledge

Psychological research tends to back the idea that intelligence exists, it is at least partly heritable, and there are few ways to improve it in a very general capacity.

At first thought, this can be kind of depressing. Some people might just be smarter than you, and that might keep you from getting good at certain things.

However, the reality isn’t quite so gloomy. For while some people might have inherited slightly better working memories than others, the most powerful way to improve your working memory is to simply learn a lot. Learning creates chunks, which allows you to deal with more complicated ideas at the same time.

Playing a lot of chess, for instance, will make you a much better chess player than someone who is really smart, but has never played the game.

The downside of learning, is that the chunks you acquire tend to work in fairly narrow domains. Playing a lot of chess will make you a better chess player. But it’s unlikely to make you a better scientist, programmer or artist.

This is the essential trade-off of learning. Learning is very powerful, but tends to be somewhat narrow. Intelligence is general, but can often be swamped by differences in acquired experience.

Why Are Some Subjects Harder to Learn Than Others?

This theory helps explain why some subjects feel like they require more intelligence than others. If understanding an idea requires considering many different ideas in quick succession, it’s a lot easier to lose the thread if you have lower working memory. Example: mathematical proofs.

In contrast, if a subject requires a large volume of memory, but each fact and idea is largely separate, then it may require a lot of practice without needing a ton of working memory. Example: history or law.

When learning Chinese, for instance, I often felt the volume of words and characters to be overwhelming, even if learning any particular character wasn’t too hard.

Learning physics, in contrast, it can sometimes feel like you either “get it” or you don’t. Either the explanation makes sense to you, or the insight goes over your head and you’re lost.

Is The Problem the Subject, or Just How it is Taught?

While this may seem to put an barrier up to understanding some subjects, if you don’t have enough raw intelligence, I actually think the opposite is true.

Because you can expand your working memory within a subject by creating new chunks, even very complicated ideas are understandable if you’ve mastered the parts.

The perceived difficulty is often the way these subjects are taught. As you go higher into math and physics, weaker students naturally drop out. All else being equal, those who were a bit smarter and found it a bit easier are more likely to stay.

Since better students are more likely to have larger working memory, more chunks from experience, or both, the class average ability will get higher and higher as you go further in these topics. Since classes are usually taught to the average level of ability, this means that explanations get shorter, with more “trivial” steps skipped over. This can lead to you feeling like you can’t keep up.

There are, however, solutions to this. The first is for teachers to slow down the class. Presenting explicitly ideas which would otherwise be implicit, so you don’t accidentally get lost.

The second solution is for the student to manually slow down the class. This can be done either by using techniques like the Feynman Technique, which crawl through confusing explanations to prevent working memory overload. You can also pretrain the prerequisite ideas, so that there are more chunks, and thus fewer ideas need to be considered simultaneously in order to learn the new subject.

What Does This Mean for You?

Anything you want to learn can be learned. However, some subjects may appear harder because the speed at which they are taught makes it harder for you to follow along without missing key links in the reasoning to arrive at the right insights.

There’s a fix to this problem, however, the trade-off is that it requires more work. If you can’t see everything all at once, it means you need to practice more the pieces so you don’t need to juggle as many ideas simultaneously in your head to reach the same conclusions.

While needing to put in extra work may feel discouraging, I prefer to see the glass as half full—it also means that you can learn anything you want, if you’re willing to work at it. No subject is too abstract, difficult or confusing that it can’t be overcome with patience.

The post Do You Need to Be Smart to Learn Certain Subjects? appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 10, 2019

Your Life Problems are Really Learning Challenges in Disguise

There’s a lot of different lenses you can use to view any situation. Say you’re trying to get in better shape, improve your career, find a good relationship or just want to be happier with your life.

You could see these through a lens of effort: the problem is simply that you haven’t tried hard enough and now you need to really get serious. Really start exercising, work harder, meet more people, finally commit to things, and so on.

You could see these problems through a lens of other people. You need to get other people to help you, either by befriending them, cajoling with them or earning their favor. Once you’ve got the right people next to you, everything else will click into place.

You could even see these problems through a lens of attitudes. Have the right beliefs, optimism and inspiration and you’ll be successful.

Some of these lenses might not help you see much clearer than before. However, some lenses immediately bring a lot of clarity to a situation. Once you view your problem through the right lens, it can be a lot easier to think about.

In this post, I want to argue that a particularly helpful lens it to view your life problems as learning challenges in disguise.

How Life Problems are Really Learning Problems

Some people are resistant to this lens. They’ll argue that they already know what to do, they just don’t always do it. The problem is doing what they know, not knowing what they do. You need to actually get out and exercise, not learn about new workout plans.

Others argue that learning is often procrastination. More time spent researching is more time spent delaying actually doing what needs to be done. You need to actually start your business, not keep researching new business ideas.

The problem with these perspectives is that it tends to assume learning is mostly the narrow, book-based studying you’re used to in school. That to learn something new means reading a lot and contemplating theories rather than taking action.

If you look at definitions of learning in cognitive science or psychology, however, it’s clear that what most people stereotype of as “learning” is just one very specific type. Learning includes almost any persistent changes that occur in your brain as a result of experience that is beneficial.

Learning Beyond Studying

With this broader perspective, a lot of things that don’t at first seem like learning challenges, become a different kind of learning challenge.

Consider exercising again. It’s probably true that you don’t need to read about more exercise plans or theories of weight loss to get in better shape. But the challenge still involves learning, except it is learning how to get yourself to exercise regularly.

This kind of learning isn’t theoretical, but it still works on exactly the same principles that all learning operates on. You have to pair cues and reactions (say having your day end with going to the gym). You have to integrate feedback, so when your habit collapses you know how to readjust it to prevent failing next time. You have to learn skills—not just physical ones like lifting weights, aerobics or dancing—but mental ones of motivation, persistence and prioritization.

Similarly, having a good relationship is also a learning challenge. You need to learn to communicate. You need to learn social skills, how to have conversations and learn to read emotions and situations. The learning involved here is sophisticated, even if it doesn’t come from a book.

Why Adopt This Perspective?

I said from the start that you can view your problems through any number of lenses. Learning is just one of them. However, I believe it can be a particularly useful lens. In fact, I’d argue it’s a much better lens than ones which emphasize effort, attitudes or other people.

Effort matters, of course. But when you can’t seem to put in enough effort, how does this perspective solve your problem? Just do… more? But if you can’t do more, the solution this lens offers dead-ends pretty fast.

Learning, in contrast, suggests that there is a hidden system that you need to understand. That system may be out there in the world, in the form of things you need to know and skills you need to master. But it can also be inside your head. Learning how to motivate yourself, stay committed, disciplined and focus on your priorities turns our initial response from “Put in more effort,” to, “How could I put in more effort?”

Attitudes also matter. Optimism, inspiration and motivation are key elements to succeed at anything. But, what about when you are feeling pessimistic, afraid and discouraged? What then? Simply “reverse” how you feel about things? How long can that realistically last?

Learning, in contrast, makes your problems objective. Instead of just feeling good about them, you need to figure out how they work and how you can move forward. Experimentation, feedback, researching new strategies, techniques and methods.

Other people also matter. But when you put your salvation in the hands of other people, you also give them a power over your life. If your success doesn’t depend on you, how can you possibly make it come about?

Learning Challenges and Solving Life’s Problems

Viewing your problems as learning challenges may help in some cases. But in other cases, it may seem to be confusing. How do you learn to motivate yourself and stay disciplined? How do you learn empathy, communication and social skills? How do you learn when there’s no subject to study?

Fortunately, there’s already a lot known about what ingredients are necessary for learning to occur. Environments that allow for feedback. Breaking down complex skills into manageable parts. Repetition and recall to make patterns into memories. Ideas and examples to model your progress from.

Turning a life problem into a learning challenge doesn’t make it trivial. But it can offer solutions where other ways of thinking just lead to confusion.

Thinking about life’s challenges as learning problems has been a big motivator behind my book, ULTRALEARNING, now available for pre-order.

The post Your Life Problems are Really Learning Challenges in Disguise appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 8, 2019

Is Mastery More Like a Wedge or a Knife?

There’s two main ways to think about becoming really good at something.

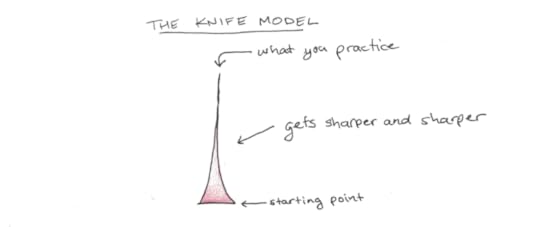

The first I call the knife model. This is where you get better and better at a very narrow range of skills, movements and patterns. Olympic sprinters, archers and many artisans master like a knife—getting extremely good at one thing.

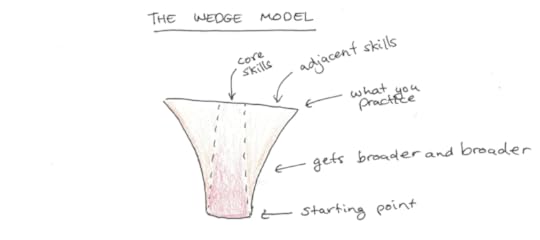

The second I call the wedge model. This is where getting better requires learning an increasingly broad array of subskills. Programmers, composers and entrepreneurs master like a wedge—getting better overall, by having a huge library of patterns and skills.

I’d like to argue that the wedge model matters more for most of us. To get better at our work, we need to pick up more and and more adjacent skills to flesh out and support the work that we do.

Why Wedges Beat Knives

At first glance, this may sound like an argument against specialization. Wedges fan out, knives sharpen in. But this isn’t the case: both wedges and knives are a kind of mastery of a single domain, they just represent different ways of going about it.

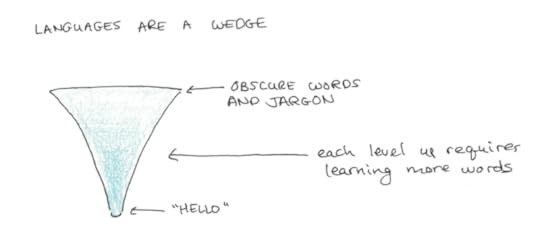

Consider learning a language, a clear instance of a wedge. You must learn vocabulary, but to increase your overall proficiency in the language, you need to go broader. Learn less frequent words. Master less frequent grammar. Spreading out in knowledge, yes, but always constrained to the overall goal of communicating better.

Or consider programming, another wedge. Good programmers aren’t those who know one way to solve a problem. Good programmers are those who know a dozen ways to solve a problem, all with their own trade-offs and design implications for larger code. Breadth of knowledge, but still about coding.

Even artistic mastery often looks like a wedge. Van Gogh, in his training as a painter, experimented voluminously with different styles, theories and techniques. His breadth of knowledge about art allowed him to hone the specific style which would later make him famous.

What to Learn to Improve Your Career

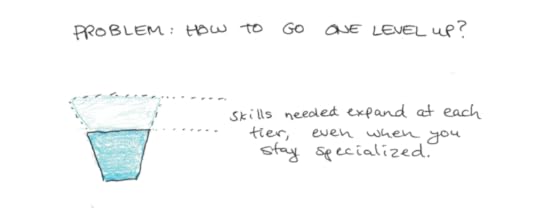

I like the wedge model because it says that the way to improve your professional skills is through looking at neglected adjacent skills and improving them. It also says that, as you get better, you’ll need more and more to continue to go upward.

In my course I teach with Cal Newport, Top Performer, I often get questions from students about what kind of skills they should master. They’re often looking for the singular “big” skill that if they learned it, they would immediately advance to the next level.

While sometimes those big skills do exist, for anyone who has been working in their career for awhile, those have likely already been learned. To go further, therefore, requires mastering increasingly specific adjacent skills. Otherwise, you just end up with vague answers like, “improve soft skills” or “communication” when trying to figure out what will advance your career.

Consider my writing. I’ve been writing for thirteen years, and I’ve published probably close to two million words. My ability to write likely isn’t going to improve much by repeatedly practicing writing articles.

Yet, I’m also aware that there’s still a lot better I could get. I read other writers and recognize that they do a much better job than I do, some of whom haven’t even written as much as I have.

What’s the solution?

The response here is to recognize that my writing is a wedge. I need to pick up skills adjacent to my core writing. Research and domain knowledge on the subjects I write about. Humor, storytelling, vocabulary, design and illustration. All of these little skills I can actually work on and get better at. While none of them will likely make an overwhelming difference to my writing quality, if I keep working on all of them I will eventually get better. After years, the wedge grows and I get better.

Think about your own career. What skills and actions do you perform every day? Which ones, if you could be better at them, would make a difference in your career? How could you build the supporting structure around those skills so that you can get better at the things that matter? Share your thoughts in the comments!

The post Is Mastery More Like a Wedge or a Knife? appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 6, 2019

How to Stop Feeling Like an Imposter

Imposter syndrome is the feeling that your achievements don’t matter. That you only scraped by because of luck or by fooling others into believing in you. You feel deep insecurity about your work and accomplishments, always anxious that you’ll be exposed as a fraud.

While arrogance isn’t good, I think impostor syndrome is far more prevalent than most of us realize. This is because the fear of being “found out” causes those who suffer from it to languish in silence. They don’t want to admit their insecurities for fear that this may trigger the revelation of their “true” worthlessness for all to see.

Impostor syndrome doesn’t just strike those who are high-achieving, but can hit even people who have more modest success.

It also seems to impact women more at higher rates than men, which makes sense if you don’t see yourself as fitting the stereotypical image of what a “successful person” looks like in your field.

My Own Struggles with Insecurity

There’s some irony in writing this post because rather than being brimming with self-confidence, this is definitely a feeling I struggle with daily. Indeed, I feel awkward writing about it, as if admitting my own insecurities might somehow bolster proof of my own inadequacy in the eyes of others.

However, if I step back, I can notice a pattern in my own life. I start by looking at someone else who has achieved something, I will compare myself to such a person and imagine that they are successful, while I am not.

Later, if I happen to reach the same benchmark, what I did now feels trivial, and there’s a new standard that needs to be reached if I can qualify as having accomplished something.

Publicly, I’ve learned to suppress this instinct somewhat, but I find it dominates a lot of my private thoughts and feelings.

An example would be language learning. When I first started learning French, I was in awe of Benny Lewis and his ability to speak several languages. Later, when I did so for myself, the achievement no longer felt special, but simply trivial.

Now, my feeling is an anxiety that my level might not be good enough. While I would have previously considered holding extended conversations to be “good enough,” now I felt like it was inadequate compared to complete fluency—I should be able to understand everything perfectly and speak without mistakes.

This pattern—finding something special, reaching it, and then immediately discounting that as not being a “true” accomplishment—is something I’ve found pervasive in my own life. Perhaps it is a pattern you notice in yourself as well.

There’s nothing wrong with setting harder goals. The problem with impostor syndrome is that you erase your own past progress by changing your standards to put it “below” what you consider successful.

Why Do Successful People Often Feel Like Failures?

To understand impostor syndrome, we need to look at what can cause it. This isn’t an exhaustive list, but here are two big factors that distort your thinking about yourself

Factor #1: Achievements are Objective Yet Feel Relative

Let’s start with the first factor: relative status.

Intuitively, it’s easy to step outside and take a birds-eye view of any field of achievement. From there, you can rank people on their overall level of success. Within a company, there is entry level, manager, vice president, C-level executive. Academia has masters, PhDs, professors and prize-winning researchers. Athletics has regional, national, Olympic and world-record performers.

However, in reality, we’re much less sensitive to this absolute scale of excellence than we are to our relative position within it. As such, we see the rungs above us and below us in much greater detail and conscious awareness than those which are quite distant.

For me, all the rungs of achievement much above me are far enough away that I can basically ignore them. Authors who are world-famous. Linguists who’ve mastered 40 languages. Polymaths who were recognized for their brilliance in many subjects. These accomplishments are so beyond what I’ve experienced, that they don’t cause me any anxiety at all.

Insecurity Comes from Magnifying the Levels Just Above You

However, I am more aware of people who are slightly above me in the rank. When it comes to topic expertise, therefore, I compare myself unfavorably to those who have studied subjects deeply in grad school. I compare myself to people who run “real” businesses with dozens of employees. I compare myself to people who speak a language I know fluently, instead of my intermediate level.

The problem is that once you go up one rank, the rank above that suddenly snaps into view. When I went from a solo business to a team, immediately that new accomplishment became the baseline and my comparison grew. If I were to get a PhD in something, I’d become immediately aware of the difference I had with tenured professors or recognized experts.

In short, our relative status perception means that there’s always a clearly-defined rung above us and below. Insecurity therefore, can come from an over-emphasis on the rung above you, rather than recognizing the rungs you’ve already climbed and the successes you’ve already surpassed.

Where imposter syndrome differs from this, is that it tends to make even the current rung seem untenable. The position you’ve reached was through luck, circumstance or because others incorrectly perceived you to have done something impressive. Therefore, there’s a constant fear that you’ll slide back to earlier rungs or fall off the ladder altogether in a spectacular crash.

Factor #2: Invisibility of Insecurity

Another contributing factor to imposter syndrome is that you may not be aware that other people are experiencing it. The fact that others seem so confident, secure and full of self-esteem may reinforce your belief that your own doubts are proof of your illegitimacy.

When asked how many of their peers have had sex or how much alcohol they drink, college students grossly overestimate the promiscuity and partying of their peers. Everyone else, it seems, is having a raucous time and it’s just you who is alone and boring.

This overestimation seems to be from an availability heuristic. The people who seem to be having wild fun are highly visible, whereas those staying at home studying are not. Therefore, we overestimate their occurrence.

This may also lead to some depression, especially if you think having fun and going on lots of dates is an important goal in your student days. It feels like you’re the only one, and thus your insecurities deepen. If you could see the reality (most people aren’t getting laid and partying as much as you think) then you’d probably feel more secure in yourself.

Similarly, if you could enter into the private lives of many successful people, and see how they struggle with their insecurities or worries that they may have reached levels of success exceeding their merit, you’d probably be reassured that your own feelings are normal. Yet confident people are highly visible, those who struggle with doubts keep their mouths shut.

Overcoming Your Imposter Syndrome

I think the first step to overcoming your own insecurities is to realize how normal they actually are. That much of the seeming confidence and bravado people display is really thinly covering up their own doubts about themselves.

Once you see self-doubt and insecurity, not as a unique disorder you exhibit, but something that impacts many people, it’s a lot easier to get comfortable with those feelings.

Another useful tip from me has been to read successful people’s biographies. The reason is that you’d be surprised how many extremely successful people spent their whole lives grappling with intense self-doubt and insecurities. Famed poet, Maya Angelou once wrote:

“I have written 11 books, but each time I think, ‘Uh oh, they’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody, and they’re going to find me out.’”

Next is to consciously adjust your fixation away from that rung of the achievement ladder immediately in front of you. It may not be habitual, but focus on the rungs you’ve already climbed and the difficulties that came with them. This can avoid the temptation to write down your past achievements as being trivial and the ones in front of you as being those that truly matter.

Finally, I would recommend taking a softer view when evaluating the works and accomplishments of others. Attack and criticize others constantly, and you’ll end up attacking yourself. When you start exaggerating the flaws of others, your own will seem to be magnified as well.

I don’t know of any bulletproof cure that will immediately fill you with lasting confidence in yourself. I’m not sure if one existed it would necessarily be a good idea to use it too often. But, moderating your own tendency to discount your achievements and feel more comfortable in the position you’ve reached is something we call can aim for.

The post How to Stop Feeling Like an Imposter appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 3, 2019

What is Quantum Mechanics? (An Incomplete and Amateur Summary)

In case you missed it, I spent last month learning MIT’s quantum mechanics. I’ve written a bit about how the project went, what I did and why I did it here. Today, I’d like to talk about what I’ve learned and try to explain, without using math, what picture of reality quantum mechanics gives us about the world.

Trying to explain quantum mechanics, as a non-physicist, is a risky operation. Few topics attract more nonsense and pseudoscience than popularizations of quantum mechanics. I really don’t want to add to that pile of garbage.

Still, after spending some time intensely learning the subject, I figured it would be useful to share what I’ve learned, to try to show why I think it was worthwhile to learn in the first place. Therefore, if you have the interest to keep reading, think of this as a summary of my experience, rather than an authoritative guide to quantum mechanics.

If you really do what an authoritative guide to quantum mechanics, you have two good options.

The first is to watch Richard Feynman’s brilliant lectures which describe, without any math harder than squaring a number, how quantum mechanics works.

If you want to go deeper, as I did, then I recommend also taking MIT’s free 8.04 class in quantum physics. To understand it, you’ll need to have taken calculus up to differential equations at least, and studied classical mechanics, electromagnetism and wave mechanics.

Those caveats and risks aside, here’s my intuitive understanding of how quantum mechanics works (minus the math).

How Reality Really Is

Quantum mechanics may sound like a weird, esoteric theory. But the amazing thing is, that it is the best possible model physicists have found for describing pretty much all the stuff in existence. Light, electrons, atoms and even you and I are governed by quantum mechanics. Even gravity, which physicists haven’t yet unified with quantum mechanics, is suspected to have a quantum theory at its core, so it’s a really general idea.

Not only is quantum mechanics nearly universal, it’s also super accurate and successful. The difference between experiment and prediction is insanely high (Richard Feynman compares the two by saying it’s like measuring the distance between the Earth and Moon and being off by only a foot). Thus, weird as it is, quantum mechanics is a better candidate for “how stuff really is” than anything else we have dreamt up.

Okay, so the near-universality and success of the theory out of the way, what does it actually say about the world?

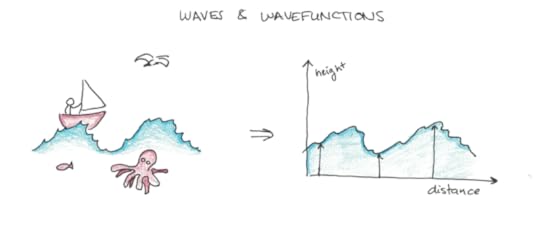

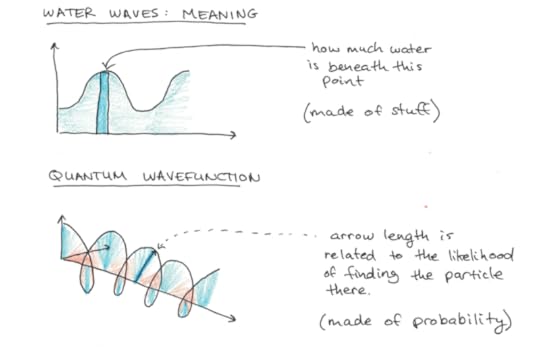

One way to describe it is to say that all stuff can be modeled by a wavefunction. Wavefunctions aren’t too complicated, they’re a lot like waves you’re used to. If you took water waves in the open ocean, and measured the height at each point, you could probably graph something that looks like a wavefunction.

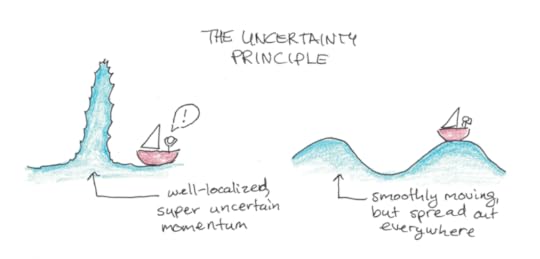

There’s a lot of connections between waves of water and quantum wavefunctions which can make (some) of the quantum weirdness seem rather ordinary. Consider the famous Uncertainty Principle, which says you can’t simultaneously know the position and momentum of a particle.

There’s something analogous in water waves. To make a wave really well localized (meaning all the water is bunched up in one place), you have to make it very unstable. To make it move at a uniform speed, you need to spread it out into regular crests and troughs. Therefore, definite position or momentum, both can’t exist simultaneously because those things mean contradictory things when we’re talking about waves.

What’s Weird About Waves?

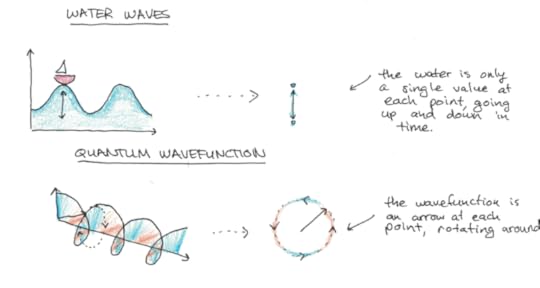

If wavefunctions were just waves like water, though, while they may be a bit tricky to calculate, they wouldn’t be weird. Physicists have dealt with waves for centuries, and it’s not so hard to understand.

Instead, wavefunctions add two new properties which are very strange:

Instead of just having one value at every point, wavefunctions have two. While a water wave can be represented by knowing its height at each point, the wavefunction actually has an arrow at each point. These aren’t real arrows (for instance, they stay two-dimensional, even when we deal with 3D situations) but they indicate that there’s more going on than in simple water waves. The fact that the wavefunction is made of arrows instead of values has some surprising implications, which I’ll explain later.

Wavefunctions aren’t waves of stuff, the way that waves on the ocean are waves of water. Instead wavefunctions are waves of probability. Here, it’s the (squared) length of the arrow at each point that says how likely it is that you’ll find the particle there. A big swell in your wavefunction means your particle is more likely (although not guaranteed) to be found there.

These two strange facts result in a lot of surprising implications for quantum mechanics which are nothing like regular waves which have only one value at each point and are made of stuff, not probability.

Arrows and Probability Waves

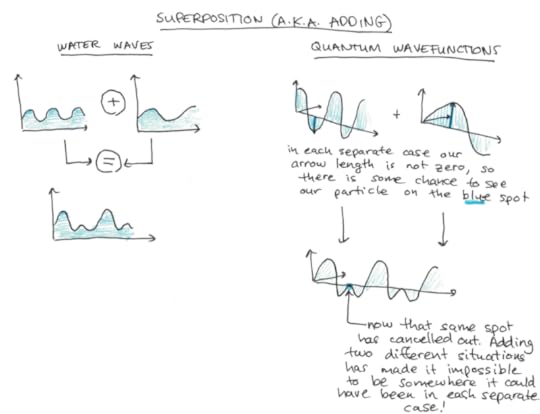

The first strange idea has to do with superposition. This is a fancy term that basically means adding, and it is one with a classical analogy: if you make ripples on water in one place, and ripples on water in a different place, they will stack on top of each other when they meet, but otherwise pass through each other unaffected.

This is a neat property of waves which helps with analyzing them since you can break down a complicated wavefunction into different superposition states to make the analysis tractable. However, from a purely visualizable perspective, I often find it easier to just imagine the wavefunction as a big complicated thing, rather than tons of separate, simpler things added together.

Normal waves add together by adding their height. Two crests meet and you get a super crest. Two troughs meet and you get a super trough. Wavefunctions add in the same way, except now because there are arrows instead of heights, you can get arrows that point in the same direction or in opposite directions. Opposite arrows, of equal length cancel, while arrows in the same direction add.

What makes this weird is when you add in probability. Since the probability depends only on the length, if you took two independent states and measured them a bunch of times, you might find that there’s always some chance of finding your particle in a particular spot. Add those states together, however, and the arrows can actually cancel each other out, making the separably possible state now impossible!

This shows two new and interesting properties of nature:

That the world is fundamentally random. Not random in the anything-can-possibly-happen variety, but in the kind of randomness you get from playing poker: there’s only some cards that can be drawn (and some you can never draw) but you can’t predict exactly which ones, only the odds.

That instead of just being a normal probability measure where different possibilities strictly add with each other, quantum mechanics uses arrows instead of values, so by setting a situation up correctly you can make two events which, if done independently, have some chance of happening, completely cancel each other out.

Things Quantum Mechanics Helps Explain

Technically the list of things that quantum mechanics explains needs to include (nearly) all physically observable phenomena, since this is the physical theory everything else, including chemistry, biology, psychology and politics, ultimately reduces to. However, practically speaking, actually calculating the quantum mechanical effects can be intensely difficult, so the actual predictions are more limited.

However, there’s still a lot of phenomena you could observe in everyday life that have a direct and simple explanation from quantum mechanics.

Why Stuff Exists at All

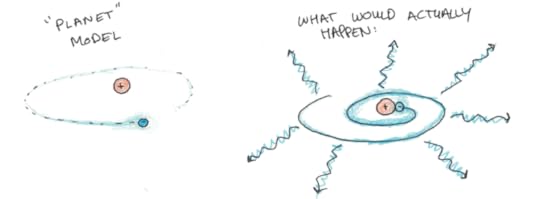

One is simply to explain why there is stuff at all. When scientists discovered the structure of the atom, electrons orbiting nuclei, it was quickly discovered that a classical model wouldn’t work. While it’s still a popular idea to think of the electron to orbit the nucleus like a planet around the sun, there’s an important difference that makes this impossible.

Electrically charged stuff, when it accelerates, gives off light. This is because, classically, a moving charge generates a magnetic field. If the charge is accelerating (meaning changing how fast it is moving) then this generates a changing magnetic field. A changing magnetic field, conversely generates a changing electrical field. These two things couple and become a self-sustaining wave of electromagnetic radiation. We call that wave light.

However, when you give off light, you lose energy. Which means unlike the stable orbits of planets around the sun, a planetary model of the atom has to have the electron rapidly crash into the center of the atom. This means, according to classical mechanics, stuff can only exist for a tiny fraction of a second before collapsing.

If you represent the electron as a wavefunction this problem goes away. Now, however, instead of a wave along a line or a surface, however, it’s each point in 3D space that gets a 2D arrow. Which is harder to visualize, but the math is basically the same. Because the wave has to “sit” in the well created by the nucleus, it has to have a certain minimum energy.

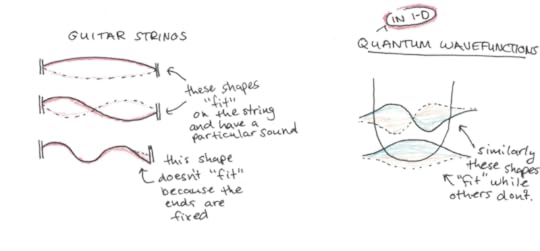

This is a little like how when you pluck a string on a guitar, it produces a certain sound. The frequency of sound corresponds to the waves which match the length of the string. Similarly, a quantum wave has to be the right shape or it can’t “sit” on the atom.

In reality, this would be in 3D, and the parabola I drew represents the potential, or “height” of the electron. Unfortunately, doing this in three dimensions is really hard to visualize, since you need to imagine a 2D arrow at each point in 3D space which is also being acted on by a potential that varies with the square of the distance. Fortunately the easy-to-see 1D case has a lot of the same physics, minus the extra energy states you get from rotating the electron around in different ways.

In reality, this would be in 3D, and the parabola I drew represents the potential, or “height” of the electron. Unfortunately, doing this in three dimensions is really hard to visualize, since you need to imagine a 2D arrow at each point in 3D space which is also being acted on by a potential that varies with the square of the distance. Fortunately the easy-to-see 1D case has a lot of the same physics, minus the extra energy states you get from rotating the electron around in different ways.Why The Periodic Table Exists

Even more than allowing stuff to exist, taking the wavefunction for an electron in an atom doesn’t just force a minimum energy, but it forces that the energy levels of the atom be discrete. This is also a surprising fact. Understanding why fully requires knowing differential equations and how complicated states can be broken down into partial wavefunctions of definite energy.

A crude analogy, however, might be to consider our guitar string again. Different waves can resonate on the string, but they are also discrete and based on the length of the string. Waves which don’t fit perfectly onto the length of the string quickly cancel themselves out. Electron wavefunctions are more complicated, so the pattern is more complicated, but it is similarly limited to fit into certain vibrations.

Combining this property, discrete energy levels, with another fact about electrons, that two cannot occupy the same exact state, means that you have atoms with electron orbitals which “fill up” and this explains nearly all of chemistry.

Why Learn Quantum Mechanics

These little bits of trivia may seem like they’re not worth all the work of learning quantum mechanics. But, in my case at least, I think it’s been worth approaching not because of a few facts, but because of how it forces you to think of how reality really is. To paraphrase Richard Feynman, understanding math is necessary to really appreciate the beauty of nature. I think that is worth the effort.

The post What is Quantum Mechanics? (An Incomplete and Amateur Summary) appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 2, 2019

Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics: Project Complete!

Yesterday morning, I finished my month-long project to get a good foundation in the basics of quantum mechanics.

I had picked this project for two reasons. First was because I knew it was going to be a challenging class and the idea of understanding the strange rules which govern all of reality has fascinated me for years. Second, because I wanted to try livestreaming an ultralearning project from start to finish.

How Did The Project Go?

I was happy with the outcome for the project in both counts—for learning quantum mechanics and for livestreaming.

I wrote a final exam for 8.04 – Quantum Physics I, the class I benchmarked for the project. The score on the exam was around 60-65%. This was complicated by the fact that about 10% of the marks were for material that hadn’t been covered in my session. Worse, I made a silly mistake (I read a question as u0 + u1, when it was u0 + u2), that made my answers wrong for multiple questions, losing around another 15%.

The class was difficult, and it took more time than I had initially expected. I had expected to put in around six hours per weekday on the project, but I ended up putting in more like seven. A lot of that difficulty came down to being rusty with a lot of the advanced calculus techniques I hadn’t practiced since the MIT Challenge, so getting caught up consumed more time than simply learning the class from scratch.

That being said, I do feel like I learned the material taught in 8.04 reasonably well. What was missing, however, was all the stuff taught in later quantum mechanics classes, such as 8.05, 8.06, and the theories which combine relativity and multiple particle interactions.

I didn’t think those things would be too important, but it turns out that a lot of the weirdness of quantum mechanics only appears once you start considering interacting particles and relativistic corrections.

I’d like to keep learning those extra classes, but as those classes don’t have any solutions to the assignments or exams, I may have more difficulties learning them the way I could with this class.

How Was Livestreaming?

I really enjoyed livestreaming the project, and I liked how it shifted the focus of the project in a new direction. The environment and passive constraints around any project often make subtle adjustments to how you approach things.

For instance, if you’re taking a class at school, the pressure to get a good grade and pass the class changes how you would learn than if you were learning to get a practical skill at work, or purely for curiosity.

My own projects in the past, too, have been influenced by those factors. Because my projects tended to culminate in some kind of bigger before-and-after write-up, I often designed projects that would work well in that format. That meant I often focused on learning things from scratch (to make the before picture clearer) and where there was an easy-to-recognize benchmark of success at the end.

Livestreaming, in contrast, is much more process oriented, so I could see it working well for tackling projects which have more ambiguous starting and end points. Some types of projects I’ve hesitated to turn into public challenges (because they don’t work well in the previous format I’ve used) might become viable, such as doing deliberate practice for skills I’m already decent at, or showing slices of learning efforts rather than complete projects.

What Did I Learn?

One downside of this project (especially for a livestream) is that if you don’t have enough math background, what I’m doing at any moment is often completely opaque. The language of quantum mechanics is written in complex valued differential equations, functional inner products and operator notation, so it’s not always clear exactly what I’m learning or doing at any moment if you haven’t followed from the beginning.

I wanted to try to mitigate that by, at the end, having a non-mathematical description of what I had learned. This is a bit foolhardy for two reasons. The first is that if a completely non-mathematical description of quantum mechanics were possible, there wouldn’t have been much need for me to learn this class in the first place.

A big part of my motivation for learning this class intensely was that I believe knowing the math is necessary, in some sense, to really understand how it actually works. Some ideas which seem disconnected are actually logical consequences of a simpler set of rules once you know the math.

The second difficulty is simply that, having only done 8.04, I’m still missing many pieces of the puzzle that would be needed to make the big picture. Trying to give a high-level summary while missing some pieces is risky, since I could give a misleading impression due to my own gaps of understanding.

Since quantum mechanics is so strange, it’s easy to grasp onto simpler, more intuitive understandings if you don’t know the reasons why those intuitions are actually incorrect. The world is full of bad quantum mechanics intuitions used as nonsense explanations for all sorts of pseudoscience, so I hesitate to add to that pile.

Therefore, if you want to really understand quantum mechanics, I recommend watching Richard Feynman’s (brief) lectures which introduce the subject far better than I could and do so without using any math harder than squaring a number:

I will try to summarize some of my intuitions about quantum mechanics, if only for the purposes of showing what I spent the last month trying to learn, rather than to pretend to have a complete understanding of all quantum phenomena, in a follow-on post.

I’ll also try to piece together some highlights/discussion from my actual recordings throughout the month-long learning efforts. This will take me awhile to process though, and I wanted to publish my thoughts on the project without too much delay after finishing it.

Overall it was a fun (and hard!) project, and I appreciate everyone who dropped by to follow along, offer encouragement of ask questions during the month. I’m excited to try new projects like this in the future, and to keep learning more about physics and quantum mechanics.

The post Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics: Project Complete! appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 22, 2019

Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics – Week Three Update

I finished the third week of my month long project to get a basic understanding of quantum physics.

I wanted to tackle this project for two reasons. First, because quantum mechanics always interested me. It’s part of the most successful scientific theory we’ve ever devised, yet it is also intuition-defying and confusing. To really understand it, I’d have to work hard on understanding the mathematics behind it.

The second reason for tackling this project was that I wanted to try out a shorter project completely livestreamed. Every minute I spend working on the project is done live, meaning there’s nothing omitted or edited out. Few people will watch even more than a small percentage of it, but I’m hoping this approach to doing projects makes them easier to document than projects I’ve done in the past.

What Happened This Week

This class has been harder than I expected. I knew it was going to be hard going into it, which was part of the reason I chose this project, but the difficulty was higher than I had expected.

I don’t think this is anything intrinsic to the class, but simply relative to my pre-existing knowledge. Going into this class, I was at a bit of a disadvantage because I hadn’t taken one of the prerequiste classes 8.03 – Vibrations and Waves, and the other five prerequisite classes I haven’t done in nearly eight years, meaning some relearning and brushing up was inevitable on top of learning new material.

This difficulty meant that my pre-planned schedule and timeframe may not be enough. This is common in self-directed learning projects. Sometimes a project will turn out to be easier than expected (learning Spanish in Spain) other times progress will come more slowly (learning Chinese).

Regardless of which way reality unfolds, however, I think keeping focused on an ambitious target is the best way to move forward. Even if your initial plan ends up being overly optimistic, you’ll still accomplish more with a challenging goal than by lowering your sights.

To compensate for the heightened difficulty, I decided to work a little more on the project this week, closer to the schedule I maintained in the earlier part of the MIT Challenge.

With my added time, I managed to finish a first pass on all the problem sets. Since I finished all the lectures the week before, this means I’ve covered all of the material now. With the remaining time I have, I’m going to try to focus on practicing the core technical skills, debugging my understanding of the concepts and drilling into memory a few of the key patterns I need to remember.

As I enter the final stretch, you can drop by to say hello as I livestream the rest of the project. Regardless of whether I meet my target or not at the end of the month, I’m going to keep studying hard!

The post Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics – Week Three Update appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 17, 2019

The 7 Core Skills to Drawing Realistic Pictures

Knowing how to draw is something most people feel is mostly about artistic talent. You can either draw or you can’t.

I disagree.

Instead, I think drawing is mostly about having a set of specific techniques, that anyone can learn, which make it a lot easier to draw something realistic.

I’m not a professional artist, and so my experience comes mostly from drawing as a hobby. However, as many professional artists have long-since mastered these basic skills, they often struggle to teach them.

I’d like to share what I think some of these basic skills are, along with resources you can use to master them. If you do, I promise that you’ll be able to draw much, much better than you do now.

Seven Core Drawing Skills

Skill #1: See How Things Look (Versus How They Are)

The most basic skill of drawing is to notice how things actually look, instead of what you know they’re really like. This sounds vague and hand-wavey, but it’s really not.

Consider drawing something simple like a table.

Question: How big is each leg of the table?

The obvious answer is that they’re all the same. That’s how tables are built. If they weren’t it would be all wonky.

Yet that’s not how a table actually looks. Because some legs are in the background, and viewed at different angles, the lines you put down to represent the table legs aren’t actually the same size.

The first question to ask when drawing is always, “what does it actually look like?” How do the edges of the object actually look, (i.e. what angles do they form and what size are they) rather than what you “know” them to be like as 3D objects.

For a great resource on mastering this core skill, I suggest Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain.

Skill #2: Block In By Comparing Angles and Sizes

If seeing how things actually look is the first skill, the second is using this knowledge in a precise way to make accurate drawings.

There’s a few different ways you can do this.

The easiest is tracing. You copy over an image to preserve the lines and structures in the original. If you have a piece of glass and a dry-erase marker you can even do this to “trace” a real-life scene rather than an image.

The next level up is drawing from a grid. Apply a grid to your scene or image you want to copy, and then draw into a grid on your paper. I did this a lot when I started, and it’s a good way to get better at drawing without feeling like you’re cheating as much.

The final level is to triangulate. This maintains precision without relying on grids and tracing is to block in the shapes by locating reference points and then meticulously building up the scene by comparing angles and sizes of lines. This requires some effort, but it’s my favorite because it allows arbitrary degrees of accuracy and transfers better to looser sketches which don’t use the technique (unlike tracing or grid drawing).

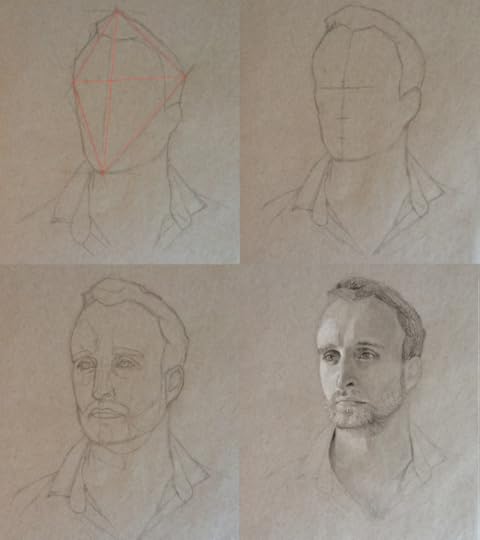

Note the lines radiating from the top of the head, bottom of chin, above the ear and on the forehead, used to block out the right width and height. Further points can then be added and refined until it is fairly accurate before finally shading things in. This is much easier than trying to draw a complete feature first (say the eye) without knowing where it goes exactly!

Note the lines radiating from the top of the head, bottom of chin, above the ear and on the forehead, used to block out the right width and height. Further points can then be added and refined until it is fairly accurate before finally shading things in. This is much easier than trying to draw a complete feature first (say the eye) without knowing where it goes exactly!The basics of this technique are as follows:

Locate a point on the top and bottom of the thing you want to draw. They should “bound” the object on the 2D scene. If you’re trying to draw a flower vase, you might pick the bottom point on the vase and the top of the highest flower.

Sketch a rough line on your paper on the top and bottom.

Measure the angle between those points by closing one eye and holding your pencil up to line it up with the two points in your scene. Holding your arm steady, bring it down to your paper and try to copy this line. Do it a few times to make sure you got it right.

Now pick a point on the left or rightmost side of the object. Do the same thing estimating the angle between it and the point from the bottom. Transfer this line to your paper. Do the same with the top.

This makes a triangle, which geometrically means that, to the extent your transferred lines were accurate, you have successfully copied the point on the page. Repeat this with a point on the opposite side (left or right) of the object.

Now you have four points. See if the angle between the left and right point on your paper matches that of your scene.

To add more points, you just need to measure angles between two points you have on the page, to the one you don’t have yet. Tracing these out slowly can build more and more reference points, which are collectively more and more likely to be accurate as you go on.

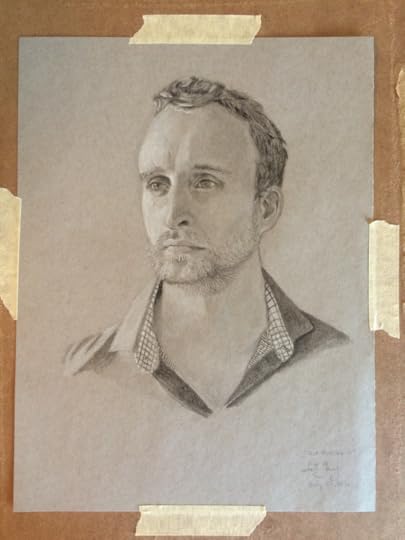

The completed drawing!

The completed drawing!The best resource for learning how to apply this drawing technique is Virtruvian Studios course on drawing.

Skill #3: Get Some Perspective

Drawing is hard because lines which are perpendicular in the real world, become weird angles on 2D scenes due to perspective.

Perspective is particularly important when drawing a scene of regular objects which recede into a distance. Therefore, it’s very important for things like drawing buildings, landscapes or big scenes. It’s less important for drawing faces and still lifes, where the subject doesn’t change all that much in terms of distance to the viewer.

While you can apply the same method as the one above to accurately draw a scene with buildings, it is often more useful as a shortcut to consider making vanishing points instead.

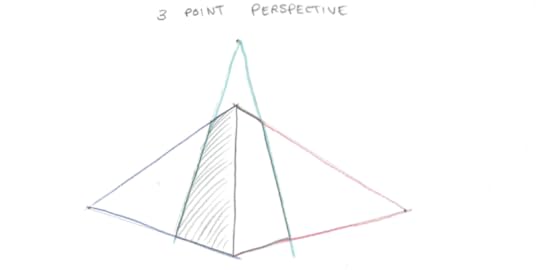

There’s three main types of perspective drawings you might consider:

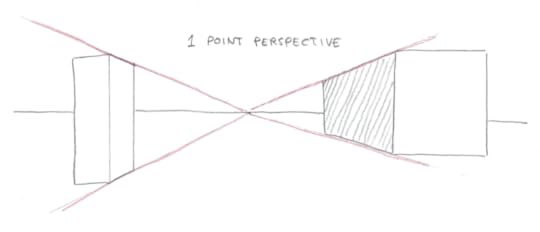

One-point perspective has a single vanishing point. This can happen when you’re looking down a road, for instance, and the buildings, lampposts and statues on the side are receding into the distance. The idea being what in the center is smallest, with what’s on the left and right being bigger and bigger.

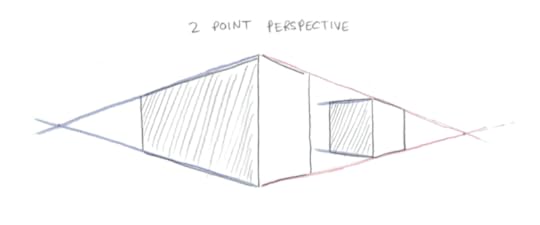

Two-point perspective has two vanishing points. This happens when you’re looking at the corner of a building, and you want to consider two streets going off in each direction. The idea here being that what is in the middle is largest, with everything to the left and right getting smaller and smaller.

Three point perspective has, you guessed it, three vanishing points. This is like two-point perspective, except now it also recedes above you. This is often the case when you’re looking up at a tall building and the top of the building takes up less room than the bottom, even thought each floor is (in the 3D world) the same size.

The Logic Behind Perspective

When I started learning about perspective, I found it very confusing. When should I use one point? Two points? The dreaded three?

The logic behind vanishing points is that all the lines that go “into” one vanishing point are actually parallel in a 3D scene. Look back at the above images. In a one point perspective, all the lines that go “into” the picture are all parallel. In a two point perspective, in contrast, there are two sets of lines which are themselves pointed in different directions.

This means that a scene can, in theory, have any number of vanishing points, each corresponding to the parallel lines themselves. If you’re doing a sketch of an old European city, for instance, you may have buildings that sit at strange angles to each other, resulting in a set of lines and vanishing points for each.

Note all the red lines are (approximately) parallel in 3D, they correspond to one vanishing point. The purple lines, because the building is faced in a slightly different angle, have their own vanishing point which is a bit closer to the center of the picture than the red lines.

Note all the red lines are (approximately) parallel in 3D, they correspond to one vanishing point. The purple lines, because the building is faced in a slightly different angle, have their own vanishing point which is a bit closer to the center of the picture than the red lines.Don’t get hung up on the technicalities of vanishing points when you get started. Instead, use them as a benchmark for blocking in your scene. If you know a group of lines (say all the tops of windows for a building) are going to be parallel, you can quickly estimate the vanishing point and sketch them all in more accurately than trying to guess the angle of each one on its own

Use Perspective Lines to Make Better Guesses

You can get started with this by actually drawing vanishing points and making your buildings or objects fit. A quicker way, once you’re more experienced is simply to expect the lines in your buildings to be self-consistent.

If you’re sketching a building for instance, and decide to draw the top of a roof at a 15 degree angle, and you know it recedes off to the right, then you know the tops of your windows can’t be at a sharper angle than that one.

This rule-of-thumb can help you make self-consistent drawings much faster than the painstaking method of triangulating points, by exploiting the regularity in the structures you want to draw.

Skill #4: Don’t Get Tricked by Relative Contrast

We’ve already seen how applying our knowledge of the 3D world to 2D drawings can lead to misleading images. But, that was relatively minor to the problems relative contrast can cause.

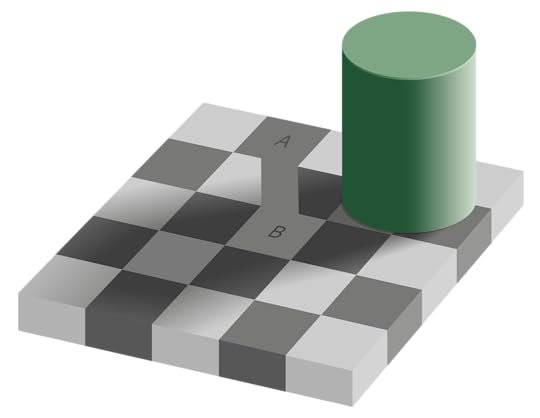

Consider this famous optical illusion:

The two squares are exactly the same value, except one looks light and the other dark. Relative contrast makes it very easy to overestimate the lightness of light objects in shadow and the darkness of dark objects in the light.

How can you avoid this problem? One way is to take a photograph and open it up in an image editing program like photoshop. There you can use the eye-dropper tool and actually sample the local value and see how it compares to other things you’ve already drawn.

Except that feels a bit like cheating. Plus it doesn’t really train your mind to sense the correct brightness value just by looking at the objects.

How do artists overcome their brain’s tendency to adjust for relative contrast? By squinting.

With details blurred out (and less light, so fewer color receptors are active) it’s easier to make out the overall shade without getting distracted by the details.

With details blurred out (and less light, so fewer color receptors are active) it’s easier to make out the overall shade without getting distracted by the details.That may sound ridiculous, but it actually works. Squinting, so you’re seeing the scene as a blurry set of shapes through your eyelashes, reduces a lot of the information in the scene. It also turns the scene into splotches of light and dark which are easier to assess on their own without the distractions of relative contrast.

Try it yourself, pick out two objects in the room and squint to compare their brightness. Now open your eyes and see how they look without squinting. Do you see a difference?

Squinting is just one technique, but if you really want to understand how to draw lights and darks, I suggest How to Draw Light & Shadow by Will Kemp.

Skill #5: Get the Big Stuff Right, and Let the Details Take Care of Themselves

A mistake I made a lot early on in drawing was putting in a lot of details on one section, without filling in everything else. I’d try to draw a boat, and I’d start putting in the lettering I see on the side of the ship before I’ve even sketched out any of the scene.

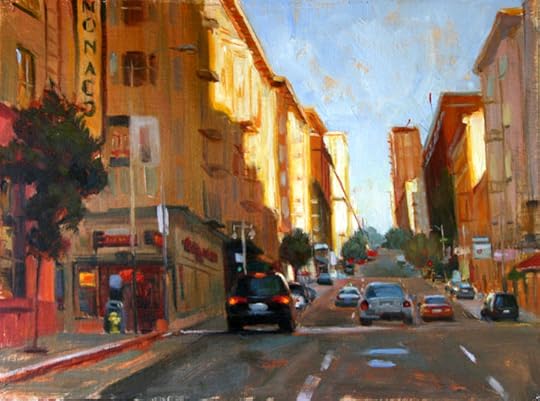

One theory I have about why this often doesn’t work, is that people have expectations of accuracy. If I show you a really low-resolution photograph, or an impressionistic painting, you’re unlikely to say it lacks artistic merit, just because it isn’t photorealistic. The relationships it does portray are accurate enough that you can see what it is.

On the other hand, if you make part of your image extremely accurate, it makes deviations from accuracy on bigger things much more noticeable. A face drawn realistically will be judged much worse for slight imperfections than one done as a sketch.

A useful skill to learn when drawing, therefore, is to start by getting the big things right. How big is the thing you’re drawing? How much wider is it than it is tall? How big is it compared to the other things you’re putting in?

Once you’ve mapped those things out right, you can actually be pretty loose with a lot of details and still have a “realistic” looking drawing. Look at the windows on this painting. They are basically splotches, yet we accept it as realistic because the big things were done right.

Artist Cynthia Hamilton

Artist Cynthia Hamilton Close up of windows

Close up of windowsSkill #6: Watch Your Curves Carefully

Curves are a lot harder to draw than straight lines. For starters, they’re more complicated than lines. You need more information to represent a curve than a straight line, so there’s more ways you can screw one up.

Second, curves often are harder to freehand draw accurately. A straight line, with practice, isn’t too hard to do freehand, even if it doesn’t meet the accuracy of one done with a ruler. However, curves often go against the natural motion of your hand, so it’s often the case that you’ll draw it wrong if done in a single motion.

The starting point, as always, is to see how the curve really is. If you had to draw tangent lines on its surface, what would they be? Does it form corners, or does it stay curved the whole way? A common mistake when drawing vases in still lifes is to kink the corners at the end, not recognizing that it will form an ellipse instead.

The top of a cup I painted. Note the metal “kinks” at the left side.

The top of a cup I painted. Note the metal “kinks” at the left side. Compare that to a photo of a metal cup–the curve is always smooth.

Compare that to a photo of a metal cup–the curve is always smooth.Next, you can sketch out a few line segments to break up a complex or sharply turning curve into a few straight-line segments as approximation. This will help you stay roughly in the right ballpark when you put curves in.

Finally, draw your curve, asking yourself how it is accelerating and slowing down at different parts of your line segment.

Skill #7: Don’t Be Afraid to Draw Things

All of these skills don’t matter if you don’t practice them. The biggest obstacle to drawing is fearing that it won’t turn out right—that you’ll put effort in and you’ll end up with something embarrassing.

This is why I think some people have convinced themselves they don’t have artistic talent.

At some point they received negative feedback about something they drew, either from a peer, teacher or parent (or even from their own expectations) and this made drawing something frustrating, instead of pleasant. They stopped doing it because thinking of drawing brings up those old fears and anxieties.

However, the truth is that drawing is mostly about cultivating a bunch of specific, learnable skills like the ones above. Anyone can learn them, they just require practice. In order to practice, you need to stop being afraid of drawing.

There’s a few ways you can build up your confidence to master these skills:

Start with easier subjects and methods. Drawing portraits with the triangulation method too hard? Try drawing a still life using the tracing approach or with a grid.

It’s okay to keep your first drawings private. You don’t need to show your mistakes, just the ones that turned out well. Even many professional artists often re-do things multiple times until they’re happy with them, so why can’t you?

Making daily drawing a habit. Set yourself the goal of drawing something every day, even if it’s just a quick sketch of something lying around the house that you spend five minutes on.

Don’t give up and keep practicing to draw better!

Resources mentioned in this post:

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain – Teaches many core drawing skills.

Vitruvian Studios – Teaches “triangulation” approach to accurate drafting, plus realistic portraiture

Will Kemp’s courses (I’m also a fan of his courses for acrylic painting) – Useful complement to Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, especially if you find you learn better through demonstration than text.

The post The 7 Core Skills to Drawing Realistic Pictures appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 14, 2019

Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics: Week Two Update

Last week was the second week of my month-long project to get a foundation in quantum mechanics, with the entire project being livestreamed.

Why I’m Tackling This Project

The inspiration for this project came about a year ago. I stumbled upon 8.04, MIT’s first class in quantum physics and watched some of the lectures. While I could follow it at a very high level, the math went totally over my head, despite having done a number of math classes during the MIT Challenge.

Ultralearning, intense and self-directed learning, is probably the only way to really get an intuition. Just watching videos and reading books isn’t enough. I would actually have to work through hard problems to wrap my head around what’s going on. Just watching videos wouldn’t cut it.

Thoughts on Livestreaming

The other motivation for this project was to try doing a project livestreamed. Documenting my previous ultralearning projects was always an additional chore. After every week of MIT classes, I would have to create update videos, scan and upload exams, update pages. During the Year Without English, documenting the project became almost involved as learning the languages themselves as my friend and I made mini-documentary videos about the experience.

Despite the effort of trying to document everything realistically, it always felt like I was leaving 99% of it out. Deciding what to show and what to omit makes it feel less authentic, yet there was only so much I could realistically do without jeopardizing progress in the project itself.

Livestreaming interested me because it seemed to solve both problems at once. One, because almost everything is visible, there’s no risk of omitting something important or possible bias about what I choose to show and what to leave out. It’s all there.

Second, because the recording is generated automatically, it’s not much more work to do a project live on camera than in isolation. I will probably need to do work to condense and summarize the project in the end (since nobody will watch the whole thing), but that can happen later when I don’t need to deal with the simultaneous workload of learning a lot of new things.

Where I’m at Now

As of right now, I’ve finished watching all 24 lectures, putting me one day ahead of schedule in initial plan. In addition, I’ve finished the majority of the first five problem sets (there are ten total). Although most of these questions have required hints and feedback with considerable struggle, so even after I finish these, there will remain a lot of work to be done.

Matching my expectations, the class is tough. It’s always tricky anticipating how hard one of these projects are going to be, and in this case I definitely underestimated the difficulty. But with greater challenge, learning is also more satisfying. I’m just going to have to work harder to compensate.

Since my next week is a little lighter on outside work, I’d like to double down and try as many days I can at a schedule similar to the one I used in the early part of the MIT Challenge. Therefore, I might be going beyond the two, three-hour chunks that I had planned for.

Feel free to drop by the livestream, even if just for a few minutes to check in!

The post Let’s Learn Quantum Mechanics: Week Two Update appeared first on Scott H Young.