Scott H. Young's Blog, page 41

February 22, 2019

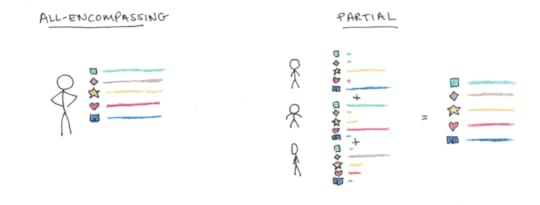

Useful Career Tool: Look for Partial Mentors

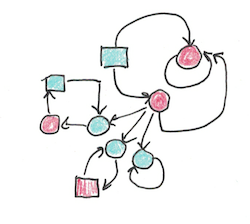

There are two kinds of people you can look up to. The first are the all-encompassing mentors. The people whose careers are ahead of yours, who have businesses with ten times your revenues, with fancier titles and more impressive accomplishments on their resume.

These kinds of mentors are great: they inspire, motivate and can offer wide-ranging advice.

However, often these mentors are more difficult to get substantial time with. Everyone would like to be hand-coached by the CEO, but there are more entry-level upstarts than C-level executives, and so, most people won’t get this kind of treatment.

Instead, I recommend most people focus on another kind of mentor—a partial, limited mentor. Someone who has clearly mastered something important, further than you. But possibly not someone who is better than you in all ways, or even in all aspects of their career.

Why Partial Mentors Can Be Greater

The relative rarity of all-encompassing mentors is one reason why you shouldn’t obsess over finding them. But another is simply that the relationships you make with partial mentors can be more equal and mutually beneficial.

Consider becoming friends with that person who is ten steps ahead of you in career or business. If that person would sit you down and patiently give you advice and suggestions, you might really benefit. But how are you going to similarly benefit this person?

There’s a whole host of reasons why mentors want mentees. But the biggest is simply when the relationship is directly valuable. If this person can learn something useful from you, or you otherwise serve as a useful contact, the relationship is going to be less one-sided.

Partial mentors, therefore, are valuable because the chances that you have something worthwhile to share with them is much higher.

My Experiences with Both Types of Mentors

In my own career, I’ve had plenty of experience with both types of mentors.

I have friends who are clearly ahead of me in experience, and from whom I’m usually taking advice (not the other way around). I try to help them however I can, but it’s clear we’re not on the same level. As a result, our interactions tend to be briefer and more one-sided.

On the other hand, I have a much larger circle of peers that are better than me at some things, but for whom I’m good enough at others to also help them. This larger circle is much easier to talk with, have more frequent calls and discussions, and even offer mutual support.

I recently decided to work on a project to try to improve the traffic on my website. As a result, I talked to one of my friends who is an expert in SEO. Another who generates a lot of traffic with his website, and still another who has had impressive success with social media.

Individually, I wouldn’t want to completely emulate what any of those three people do in isolation, but in combination their suggestions were better than any I could have reasonably achieved from a perfect mentor who was doing exactly what I wanted. Best of all, because these people are not so far ahead of me, I can also offer something in return, say from my experience running courses.

Seeking Out Partial Mentors

The first step is to drop the expectation that someone should be better than you at everything in order for you to learn something from them. Mentors don’t need to be strictly higher than you in whatever social hierarchy you experience.

Second, try to cultivate friendships with people whose skills are broad and diversified. Therefore, you may not have one single person who is amazing at everything, but when you consider your social group as a whole, its collective intelligence ought to greatly exceed your own.

Third, try to size up and identify your relative value that you can contribute back to these partial mentors. What can you add that they don’t possess? Which skills, knowledge and experiences do you have that you could presumably help them with. Be generous with your talents and others will be with theirs.

The post Useful Career Tool: Look for Partial Mentors appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 21, 2019

New YouTube Videos and Podcast Episodes

I’ve been experimenting with recording videos as companion pieces to my regular articles. You may have noticed some of them embedded at the bottom of my most recent articles.

If you’re interested in getting my videos on YouTube, please subscribe to my channel. I’m still early in this experiment, but the more views/subscribers, the more I’ll take it as a sign to keep making regular video content. So if you would like to see me speak more, please let me know

Additionally, we’re also going to be making quick podcast episodes out of the videos, so if you prefer to listen to podcasts, you can also get my ideas there as well!

What do you think? What kinds of stuff would you like to see on the blog? Share in the comments and let me know!

The post New YouTube Videos and Podcast Episodes appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 20, 2019

Bored with Your Job? The Recipe for Enjoying Your Work

Endlessly boring meetings. Frustrating clients. Work that seems to pile up endlessly and never get done. There’s plenty of reasons to dislike work, but the state of stressful, near-constant distraction tops the list for many.

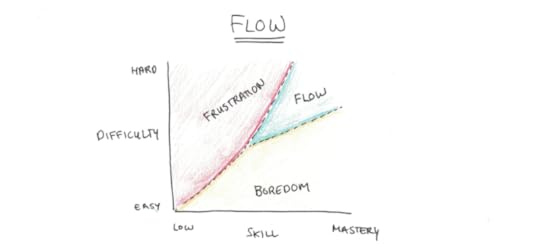

Compare that to the state of flow, described by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. The state when the outside world fades away and you’re completely absorbed in your task. It’s neither frustrating, nor boring. Time melts away and you get a ton of work done effortlessly.

This state of flow is great for your productivity, but also for your sense of well-being. Flow, Csikszentmihalyi argues, is a key ingredient to your happiness. Experience it more, and you’ll be happier at work and in life.

More than promotions, accolades and fancy titles, how happy you are at work will depend greatly on how much of your time you spend in flow.

Therefore, if you want to enjoy your work more, you need to engineer a flow state, even if it isn’t the default.

How to Reach Flow

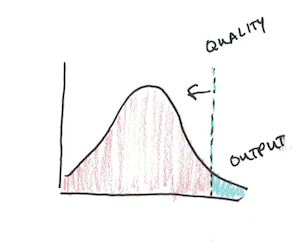

The major component of flow is simply difficulty. Flow occupies a relatively narrow range of task difficulty.

Too hard, and you’ll be interrupted constantly by frustration. Little jolts of negative feedback from the task will give you an urge to quit, or take you out of the moment. If the difficulty is too high, every movement forward in your work will require immense effort.

Too easy, and you’ll be bored. Flow requires that your complete attention be focused on the task. Once your mind feels like it can do the task in the background, without full concentration, your default mode network starts to turn on. This system in the brain comes on when you have nothing else to think about, and is responsible for day dreaming and random thoughts.

Therefore, to achieve flow in your work you need to find the right spot between frustrating and boring. Sharpen your mind, but grind it too much and it will start to break.

How to Adjust the Difficulty of Tasks You Don’t Choose

This range of difficulty seems to present a problem for finding flow at work. Unlike things you do for fun, work tasks are rarely chosen for being of optimal difficulty. Instead your day is likely full of all sorts of tasks, some boring and repetitive, others frustrating and painful.

While getting to the optimal flow is not possible 100% of the time, you can adjust your frustrating tasks to be a little easier (at least psychologically) and make your boring tasks a little more interesting. Even if you only do this a little bit, the amount you end up spending in flow will be much higher.

How to Make Frustrating Tasks Easier

There’s a few ways you can take a task that is frustrating or unpleasant and make it easier (and thus more likely to produce flow):

1. Slow it down.

Sometimes the frustration isn’t inherent to the task, but to your task expectations. If you’re expecting yourself to write a thousand words every hour on a big report, but you’re dragging, maybe your expectations are simply too high.

Slowing down your work, especially at the initiation of a task, can often reduce the frustration enough to start slipping into flow.

2. Break it up.

Task complexity can make something more frustrating, even if the individual components are not terribly difficult on their own. Creating a marketing plan for a new product is daunting. But individual tasks like deciding on the color, name, font choice, etc.. are simpler and easier.

Many tasks are frustrating because we attack them as cohesive wholes, rather than stepping back, dissolving them into more manageable sub-tasks and taking each on on its own.

3. Lower your quality.

This one sounds bad, but it’s really not. Perfectionism, especially the idea that you’ll make no mistakes or produce fantastic work your first try, can impede flow. This is because every attempt you make to get started is ruthlessly criticized by the part of your brain that evaluates your output.

The key to achieving flow, therefore, is to lower your standards temporarily to get the faucet running. Once you have a good flow going and have output some work, you can give yourself a separate time to go back and reevaluate it for quality.

How to Make Boring Tasks More Interesting

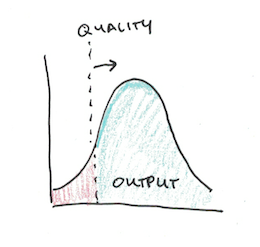

The second part of flow, however, actually involves making easy tasks harder. Boring work is work that is almost impossible to focus on because your motor routines have made it so that it doesn’t occupy much mental space.

This is what is so hard about mindfulness meditation. Just breathing is very hard to achieve a state of flow because your mind already has minimal cognitive routines that automate this action. Therefore, you tend to start daydreaming spontaneously when you don’t have something harder to do.

Here’s a few things you can do to make boring tasks more engaging and thus more conducive to flow:

1. Up your game.

Just as lowering expectations helped with frustration, increasing them helps with boredom. Even a slight increase in standards is often enough to make your focus sharper.

I used to work as a lifeguard, and watching all the swimmers can often be an incredibly boring task. One way to make it more engaging is to play a game—see if you can mentally focus on each person in the pool (say there are 25) in one minute. Make a cycle of it and see that you don’t miss anyone.

2. Raise the stakes.

Arousal (in the general, not sexual, variety) is a major determinant of focus. Since flow is based on a state of focus, then being under-aroused due to lack of sleep or interest, can lead to boredom spontaneously by preventing you from maintaining a sharp focus.

A simple way to increase arousal is simply to make the stakes higher for whatever you’re doing. If you have a boring task, measure your performance and keep track of it as you go. Top scores in video games can compel interest, even if you’ve long mastered the core skills.

3. Do it differently.

Motor routines tend to automate routine actions and procedures. Not only physical actions, like in sports, but even mental work can often become automated in this way. Think about typing in your PIN code for your bank, this is more a muscle memory of your fingers now than a conscious recollection of the digits.

Similarly, if you change up your explicit strategy, removing the ability to do it by rote, you can increase engagement. Most tasks have multiple variations for how they can be performed, so explicitly doing it a little differently can often lead to greater engagement.

Flow and Happiness

Obviously there’s more to whether you like your job than simply being in a flow state. Toxic work cultures, bullying bosses, lack of recognition and terrible schedules all contribute.

Yet, flow remains an underrated aspect of our happiness at work. Engineering flow may not solve all problems, but it’s a good start in the right direction!

The post Bored with Your Job? The Recipe for Enjoying Your Work appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 19, 2019

Is Ambition a Good Thing? Thoughts on Striving Without Selfishness

Ambition is a concept that gets mixed reactions.

Some people see it as the essence of progress, virtue and character. Those with ambition take action, set goals and build meaningful things. Without ambition, nothing would get done. In this sense, ambition is synonymous with vision, the opposite of laziness.

Other people view it as the essence of corruption. Those with ambition take from others, cheat, swindle and are ruthless in getting what they want (especially to those who get in their way). Without ambition, the world would be a kinder, gentler place. In this sense, ambition is synonymous with greed, the opposite of contentment.

To me it seems that the latter problems of ambition are mostly because ambition is a selfish pursuit. In other words, ambition is bad when it centers around your ego and self-aggrandizement.

Is Selfless Ambition Possible?

Ambition is a motivation to achieve things. Motivations can have many possible sources.

It could be from a creative urge. An ambitious novelist might craft an engaging epic because the vision pulls her forward.

It could be from a desire to change the world for the better. An inventor may develop a new energy source, transportation mechanism or just a better mousetrap because they want to improve the world they live in.

Alternatively, it can also come from a desire to become wealthy, famous or respected.

Some people argue that these selfish motivations truly predominate. That our more virtuous intentions are merely social masks we put on to conceal our ego-driven intents. Ambition, in this view, is always ego-driven, whether we recognize it or not.

Others would argue that, it is true that most motivations are selfish by default, this is not the only option. Turning down your own craving can allow nobler motivations to take over. Thus an ambition to serve might flourish in a mind that isn’t constantly plagued by its own dissatisfaction.

Cultivating the Right Type of Ambition

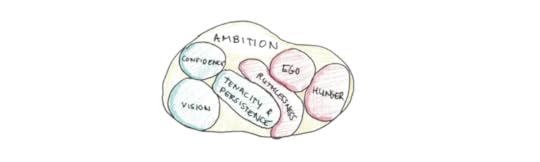

I think that ambition combines a few different qualities, some of them good, others more questionable. Which predominates can tell you about the kind of ambition they pursue and whether or not it will benefit them or the world around them.

Confidence seems to be a common ingredient in ambition. Believing one can do things which are hard to accomplish seems to be a prerequisite for any kind of ambition.

Vision is also important. Being able to imagine an alternative state of affairs and create it in enough detail so that you can venture forward and realize it is also essential.

Tenacity and persistence matter too. No truly ambitious effort will succeed without friction, so if you stop at the first sign of resistence, you won’t achieve anything.

These three qualities seem rather positive, or at least not obviously negative. However ambition also gets tied up with a few other drives:

Hunger and greed. Ambitious people often want more than others. This greater appetite may drive good deeds, but it can also gnaw away on the inside as they are ever dissatisfied with what would satiate normal people.

Ruthlessness and immorality. Ambition can also be seen in people who are willing to cause harm to others, or sacrifice other values to achieve their ends. In moderate cases this is the person who works non-stop and neglects his family. In extreme cases, this is the person who will betray a friend or harm innocent people to reach her goal.

My sense is that virtuous ambition tends to promote the former three qualities, while minimizing the latter.

Are Purely Selfless Motivations Possible?

I don’t know whether it’s possible to achieve genuine selflessness. There’s a strong argument that many behaviors we feel are virtuous conceal a selfish interior. Charity, being nice to your family, following rules and helping society, may boil down to a selfish calculus beneath our conscious awareness.

Regardless of whether this is the case, however, I think there’s definitely different qualities of motivations. Even if all motivations have some grounding in selfishness, there’s a world of difference between giving to charity in the unconscious desire to appear generous, than stealing from others to enrich yourself.

For ambition to be without ego, in my view, it would avoid these latter types of selfish motivations.

The Goal of Ambition Without Ego

My own sense is that what motivates your actions tends to come from how you feel inside. If you feel contented, satisfied and happy, you’re more likely to pursue ambitions that come from desires to serve, create or challenge yourself. If you’re deprived and dissatisfied, your ambitions may come from a deeper need.

While I think there’s a lot of flaws in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, this does roughly correspond with the pyramid he first set forth:

The only difference of opinion I would note is that it seems many people are still obsessed with “lower level” needs well beyond what they technically need to sustain themselves. The person who eats to excess, constantly depends on approval of others or wants to seem successful, may have objectively filled those lower requirements long ago, but keeps chasing the same desires.

Living well, therefore, seems to involve a kind of double strategy. One, we need to strive to meet our expectations so that extreme deprivation doesn’t turn us nasty and brutish in our motivations. At the same time, we also need to cultivate a kind of ambition that doesn’t depend on renewing already-sated hungers for its motive force.

The post Is Ambition a Good Thing? Thoughts on Striving Without Selfishness appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 18, 2019

Impossible Standards: The 3-Step Process to Reach New Heights in Your Work and Life

A few years ago my friend, Ramit Sethi, invited me to record an interview. He flew me out to New York, had an entire studio rented with a huge team and thousands of dollars of fancy equipment to record it.

I remember feeling awestruck that my blogging friend was putting in such production values in his work, and thought about my own courses. Until that point, I had made most of my living from offering Learning on Steroids, which was mostly handmade PDFs and videos I recorded in my apartment and edited myself.

My feeling at the time was twofold:

There’s no way I have the funds or experience to pull something like this off.

This is the standard I should aim at.

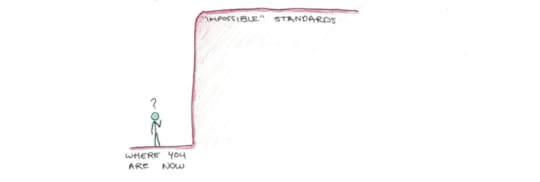

There’s an obvious tension between these two different feelings. The easy way to resolve it is to simply dismiss the standard. That it’s too difficult, out of your league or “impossible” for you, and to lower your expectations to something more reasonable.

The hard way is to expect that the standard is probably something you can’t reach, but you should still hold yourself to it regardless. That you’ll make more progress in your attempt to reach an unrealistic standard than to settle for something easier.

Choosing the Hard Way

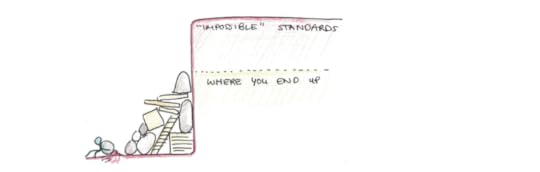

Keeping this as an ideal, I remember talking about the possibility of doing video like this with Vat Jaiswal, who helped me on making the videos for the Year Without English. Although my initial estimates of the total budget we would need were well beyond what I could afford, he started looking into it anyways.

Eventually, we found a setup that ended up being pretty good in terms of professional quality, but costing only a fifth of what some of my other friends had suggested doing such a shoot would cost.

The end result was that in my next courses, Top Performer and Rapid Learner, we had much better video quality than I had done before. This, on top of many other similar examples of higher standards set for the courses, resulted in greater sales. My business grew, and eventually expanded from a mostly solo operation to one with a small permanent team.

The Science of Goal-Setting

It’s not just my own experience of setting standards that upholds this idea. Goal-setting theorists, Edwin Locke and Gary Latham argue in their review of the psychological experiments that have been conducted on goal-setting that “specific high (hard) goals lead to a higher level of task performance than do easy goals.”

The challenge of course, is that if you set a goal too hard, you may reject it psychologically because it is too difficult. Thus, the key to this method seems to be in maintaining the tension between the goal you’re striving after and the disbelief you have that you can achieve it without resolving that tension by simply lowering the standard.

If you can stick with it, however, the pattern often goes more like this:

You observe something incredible, clearly beyond your current skill level, resources or imagination.

Instead of dismissing it as being unrealistic, however, it sticks in your mind and you follow it through as if you might actually reach it.

In the end, you get much, much closer to the standard than you would have originally thought. Often you can get around obstacles that seemed insurmountable before and end up with a level of quality that you wouldn’t have imagined possible earlier.

Another time this happened to me was with learning languages. When I was in France, I dismissed the idea of pure immersion by not speaking English as impossible. But after meeting Benny Lewis and seeing his aggressive language learning challenges, I thought I might be able to strive to do the same. My own project to stop speaking English to learn languages ended up being much more successful (in terms of eventual fluency) than I had expected, in part because the standard was higher.

I applied a similar process in writing my upcoming book. Instead of just writing it as I would a normal blog article, at my current level of ability, I picked a few books written by great authors and experts and decided to model what I wanted from the book on that process. I can’t say whether this one will pay off yet, but I do think I pushed my writing ability a lot more than I would have otherwise.

How to Leverage This Effect For Yourself

A lot of people would label this kind of pattern as “confidence” or maybe even “arrogance” when it comes to taking on goals. You simply have a lot of confidence that you’ll succeed, and that will manifest its own success.

However, my own experience tells me otherwise. Instead of confidence, taking on steps like this is usually full of doubt, insecurity and fear.

Instead, what I think it depends on is not rejecting a higher standard, just because you might not be able to reach it. Hold that tension in your mind, and quite often you’ll be able to close the gap much more than you would have previously believed possible.

I think there’s a simple three-step process you can repeat to have the same kind of effect:

Identify an exemplar. In all cases where this has worked, I’ve been able to point to a concrete example and say to myself, “that’s what it should look like.” How I should run my business. How I should write. How I should study.

Don’t reject the exemplar, just because it’s impossible to reach. Most exemplars you find will have advantages, assets, abilities and resources you don’t. Maybe a lot. That’s fine. Just don’t reject the standard—keep it in your mind, even if you will never reach it.

Ask yourself how you can get closer. The more you think about it, the closer you’ll get. You’ll find shortcuts. Ways around obstacles. Problems that seemed insurmountable suddenly reveal loopholes.

It’s not the case that every time you apply this method you’ll accomplish impossible things. However, I think the average outcome of applying this method many times will be a greater improvement in your performance than simply trying to “do better” or “improve” without setting these unrealistic expectations.

Think about your own life right now. Where are there examples of people doing something truly extraordinary that could serve as an exemplar for your life? How far could you go if you didn’t dismiss their achievements as being unrealistic?

The post Impossible Standards: The 3-Step Process to Reach New Heights in Your Work and Life appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 14, 2019

Follow Me on WeChat! (我的微信账号)

If you use WeChat, I’m publishing articles every week in both English and Chinese on my account:

My WeChat ID: Scott-H-Young

微信账号

I am regularly publishing content on my WeChat account,

both in English and in Mandarin Chinese. I also post any announcements

like book tours or meet ups in China, so make sure to follow me there!

我每个星期都会在我的微信公众号里发表文章(英文版和中文版)。我也会第一时间发布关于我在中国的图书宣传或见面会的消息,以此记得关注我!

Here are some of my most popular articles:

最受欢迎的文章

如何在三个月内教会自己任何技能——所有自学的重要原则都在这里了

习惯堆叠:(当你时间不够时)如何完成每天要做的事?

九个习惯提升你的精力水平

My books // 书:

亚马逊(实体书购买链接)

知乎(电子书购买链接)

豆瓣(电子书购买链接)

My videos // 视频:

TEDx

MIT Challenge Overview

Sites where I am featured:

知乎

知乎Live

豆瓣

Bilibili

The post Follow Me on WeChat! (我的微信账号) appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 13, 2019

Should You Target the Minimum?

Whenever you set a goal, create a new habit or make some plan for your life, there’s a few different ways you can go about it

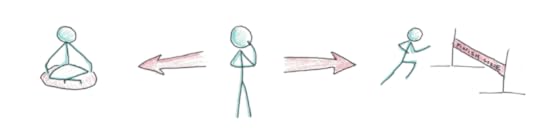

The first way is to target the minimum output. The idea here is that you focus on always doing at least a little bit, so that overall, you’ll end up doing enough to make it count. Examples: meditating for ten minutes a day, taking the stairs at work to get in shape, learning a new word every day.

The second way is to target the average output. Here, you focus on setting a goal that you don’t always achieve, but if you reach it enough, you’ll end up making a big difference. Examples: write a new blog post every week, read two books a month, go to the gym 4x per week.

A final way is to focus on the maximum output. Invest your energy in surmounting a specific, intense threshold that will pull you to a new level. Examples: one-rep maximum, deliberate practice, aiming at setting a personal best.

A huge array of different suggestions from personal development flow into one of these three types, yet I’ve rarely seen them analyzed together. I’d like to do that, and try to see if there’s a way of thinking which can make sense of when you should expect each type to be more useful.

When Should You Focus on the Minimum?

To understand where each of these strategies succeeds (or underperforms) you need to compare them to the status-quo.

The status-quo in minimum-focused projects is zero. This is the default, and what will happen in the overwhelming majority of cases.

One habit I’ve focused on in this way was doing fifty push-ups every day. Some people critiqued this as not being ideal for fitness. But it ignores the alternative—usually I would do no push-ups in a day, so some is certainly better than none. Doing the push-ups hasn’t stopped me from going to the gym, but keeping the habit has made me stronger.

Another way I’ve used this was doing reading practice for Chinese. I set a goal to do ten minutes per day. Again, the default here was zero. Most days I did no practice, so a ten minute goal, even if I never do more than this, is going to be an improvement.

The other reason to focus on a minimum is that it assumes the difficulty is in starting. When initiating a behavior or effort is the hardest step in the process, you want to set lower thresholds for effort so that you can make starting as easy as possible.

Minimum-targeting works very well for establishing stable, long-term habits. It also works when the status-quo is very low or zero effort. Finally it makes sense when initiating effort is the hardest obstacle to overcome.

When Should You Target the Average?

In contrast to minimums, many goals are set by trying to provoke an average investment. The difference between this approach and a minimum isn’t, however, strictly about how much effort you put in. Rather it is how you frame the goal.

Consider my Year Without English project. That goal used, as a minimum, not speaking any English. This was intense, but the focus was on not breaking the habit ever—thus focusing on the minimum output—rather than on a goal of reaching a certain average amount of practice per day.

Compare that to a goal to learn a language by putting in about ten hours per week. Some weeks you’ll do less, others you may do more. The emphasis isn’t on never missing a session, but on trying to reach some general threshold of effort into language learning.

Focusing on the average, can make sense when input isn’t a problem. If you’re already going to do some work towards your goal, or it is always in your field of consciousness, then the benefits of minimal habits are lower. If the status quo is non-negligible, then you may want to push at it, rather than set a minimum you’re already reaching.

Targeting the average, however, is long-term in mind. You’re hoping to sustain something, even if it not always a perfectly easy and consistent output. I have a current goal now of writing five new articles per week. Some weeks, this may be impossible and I’ll fail. But the goal is to try to reach this as much as possible, and hopefully, the average will bear this out.

Average-targeting works well when you were already putting in a fair bit of effort, you want to improve that effort, and yet your focus is suitably long-term.

When Should You Focus on the Maximum?

Focusing on the maximum, has the advantage that it can expand your potential. Many areas of growth exhibit some elements of friction, that barring some kind of intense effort, planning and potential frustration, they won’t be realized.

Deliberate practice epitomizes this strategy. By putting in an uncomfortably high focus on quality, narrowing onto specific aspects of performance with clear feedback, you can get better. Such a peak learning state is less likely to occur if you don’t aim for this effort deliberately.

Aiming at one-rep maximums, or reaching personal bests in fitness, learning or life are also attempts to focus on a maximum. They too, are less likely to spontaneously come about without some conscious effort.

The downside of focusing on reaching a maximum is that it often isn’t sustainable. Bursts of high intensity rarely make for long-term, stable habits. Therefore, those who engage in routine exercises of maximum-targeting efforts often require continued obsession with performance. Maximum-targeting efforts require all your attention and energy, they can’t be engaged lightly in the background.

Maximum-targeting works well when there is an efficiency gain for reaching higher levels of intensity, or when other barriers impede progress without such intensity. They work well either with sustained obsession, or careful transition to average or minimum-tageted goals, once the burst has finished.

Concluding Thoughts

Minimum-targeting is the art of patience, endurance and small efforts accumulating into large gains. Average-targeting is the strategy of continuing what you have been doing, but expecting more from yourself and continuing it for longer. Maximum-targeting is a sprint, which can climb over mountains, but can’t be sustained perpetually.

The post Should You Target the Minimum? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 12, 2019

Should You Follow Less News?

When I was growing up, my family would watch the news every morning. The unquestioned belief was that this was a good thing to do. You should stay informed about what is happening, and news was the way to do this.

These days, I don’t have a cable subscription, so my news tends to come from social media. Twitter, Reddit, Facebook and blogs. The people I follow tend to talk a lot about news—politics, issues and current events.

Lately, I’ve been wondering whether that unquestioned belief of my childhood deserves more thought. Is following the news always a good things? Can you follow it too much?

What is Followed and What is Ignored

Whenever we talk about something being good or bad, the follow-up question must always be, “Compared to what?”

Eating potato chips all the time is bad. But the presumptive comparison there is a healthy diet. Certainly if you were starving to death, a bag of potato chips becomes a nutritious meal.

So too it is with the media we consume. Complete ignorance of what is going around you doesn’t seem to be very good. Total information starvation doesn’t seem like the right comparison. However, a lot of news and media may be more like potato chips than the healthy alternatives we ought to be consuming.

Downsides of Excessive News

The most obvious downside of excessive news is that much of it doesn’t matter all that much. Most things reported on in the news don’t have any suggested actionable consequences for the reader, and even when they do (say disaster relief or an upcoming election) the actionability of news is rarely most of the message.

Following politics, at least in democratic countries, is often seen as a civic duty. Failure to follow allows the bad guys to win elections, they say, and so failure to follow the latest twists and turns in the unfolding drama is a dereliction of that duty.

However, once again, the actions remain unclear. Elections are the major action points for political engagement, and yet they happen far less frequently than political news cycles persist.

Even if you believe political engagement is required of you, it’s not clear excessive news coverage helps. Too much news may be worse than too little, since the newness of news constantly pushes down important things. Instead of electing leaders based on well-deliberated policy opinions and patient judgements of character, the deluge of information washes away past judgements so it’s only the latest episode which stays salient.

How Much News is Ideal?

My feeling is that you should follow enough news to have a bare outline of what is going on, and you should have more information when that news should lead to decisions, but otherwise, your media diet shouldn’t focus on it.

In my perfect world, no more than 30% of my information consumption would be news. The remaining 70%+ would be spent on things that aren’t going to go stale with time. Ideas and theories which ought to be timeless.

Less News, More Olds

News focuses on what is happening now. But often what is happening now isn’t all that important. The ideas and actions that matter to your life are often unchanging. Principles, not fads. Policies, not politicians. Fundamental ideas, not ephemera.

I want to return to the question at the start, if you follow less news, what do you replace it with?

There are certainly less healthy sources of information to consume. Junk conspiracy theories, pseudoscience and ideological nonsense are all alternatives which are much worse than just following current events.

But, I suspect we can also do better. Acquire knowledge and skills which will remain valid months and years into the future.

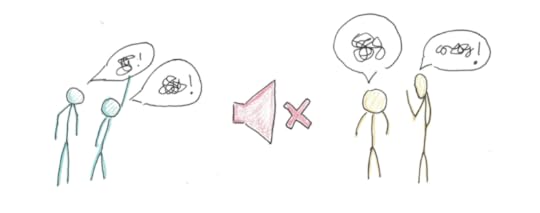

Turning Down the Volume of Your Newsfeed

In the past, news was a program on television, a magazine or paper you purchased. Now, if you get your news online, it might be right alongside your other media. The aggregating and blurring of voices means you might follow a scientist on Twitter to hear about the latest in nutrition, but mostly get their opinions on momentary politics. How do you lower the volume of news when you no longer unilaterally control your input?

1. Read more books.

Books, due to delays in the publishing cycle, can’t be nearly as in-the-moment as your Facebook or Twitter feeds. They need to be written, edited, printed and sold, all of which takes months or years.

This bias away from recency means even if you’re going to read something pertaining to politics, governance or an event that recently happened, the quality of reporting and thinking will be higher than in purely online formats. You’re more likely to encounter deeper research and nuance, and so even if you don’t change the subjects you consume, you’ll get better information.

2. Mute the loudest.

I selectively unfollow people on Twitter or Facebook who post excessively about current events and news. A small fraction of the total input sources you have create the majority of noise, so even if you silenced ten percent, you’d have a much quieter feed.

3. Follow blogs (RSS still works!)

Blogging is still a powerful medium for getting information on a particular topic, which has enough barriers to publication that there is usually a modicum of editing and thinking before the writer hits “Post.”

Although RSS is a bit of an antiquated technology, it is still the best tool I’ve found. RSS isn’t algorithmically curated by large corporations, so you have full control over your feed, rather than being recommended the most inflamatory and sensational. Feedly continues to have the highest signal-to-noise ratio for me of any of the platforms I use, and I unsubscribe from blogs enough that it typically stays nearly empty.

Ultimately, however, a decision about what media to consume requires first deciding what would be ideal, and then having the discipline and planning to stick to that choice. News, while far from the worst, doesn’t seem to deserve the portion sizes it is often allotted.

The post Should You Follow Less News? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 11, 2019

Should You Desire More or Less?

I was a teenager when I first started getting interested in personal development.

My first introduction was Steve Pavlina, who I found from an early interest in making video games. He had set up a full-time independent game development business, and the idea of starting my own small, online business became a dream that obsessed me.

Later, I listened to audiobooks by classic self-help speakers like Zig Ziglar, Brian Tracy and Tony Robbins. Together, they all suggested a similar philosophy of life: set goals, cultivate your ambition, work hard and realize your dreams.

It’s a vision of life that I connect with today. Even though, now, many of those early dreams have been already realized and my new ones lack the obsessive character of those first ambitions.

However, there’s a completely different school of thought that argues that the cultivation of desire is exactly the wrong thing to do. In Buddhism, Daoism and Stoicism, desire and craving are the very enemies you should be combating. The flames you stoke to reach your dreams are, in their view, the exact fires you need to quench.

Who is right? Should you follow your desires ardently, until you reach your goals? Or should you abandon craving and aim for a life of equanimity and serenity?

Comparing the Two Views of Life

These two visions of life definitively contradict. I’m not sure that they can be integrated in any systematic way. Yet, I also find myself hard-pressed to reject either of them.

On the one hand, my own personal experience attests to the view of goal-setting and self-cultivation. At fifteen, my life today was just a fantasy. Today I have an online business, which has supported me full-time for nearly a decade. I have a beautiful wife. I live in pleasant city. I’ve gone on adventures and enjoyed life.

What my life would have looked like, absent those early inspirations, is hard to say. I can imagine myself grudgingly showing up to a day job, with my earlier dreams and ambitions long collecting the dust of regret in the back of my mind.

Yet it’s also possible that something like my current life was mostly inevitable. Perhaps not this exact career, spouse or experiences, but something similar. In this view, it was my nature to do these things, and no particular philosophy or inspiration was necessary. Or perhaps, the goal-setting and self-development was also in my nature, thus there was never much choice involved in whether or not I would pursue it so obsessively.

The Darker Side of Ambition

On the other hand, I also appreciate the meaning behind why the Buddha argued for eliminating craving, and why Laozi argued that, “he who seeks to grasp things will lose them,” and that therefore, “the sage puts away excessive effort,” in the Dao De Jing.

It is impossible to truly satisfy all your wants, eliminate all your fears and achieve a lofty position of total success. Even in the brief moments when such a permanent success might feel imminent, the underlying emotion is rarely serenity, but boredom.

The fires of ambition and goal-setting, once their fuel has been used up, rarely fail to spread to other things, gnawing at you to do more and more, even if that wasn’t your initial inspiration.

My own, very limited, experience with meditation, gives me the impression that these ideas are deeper than simply avoiding excessive desire. Abandoning all your cravings, even for a short time, gives a feeling of happiness that rarely matches with simple achievement.

Which Should You Choose: Cultivate Your Desires or Abandon Them?

At the risk of becoming completely incoherent, I think the answer is, paradoxically, to do both.

I don’t believe the highest meaning in life should be to sit cross legged on the floor and remain equanimous as the world passes you by. Living things are meant to live, and for human beings that means striving, dreaming and reaching our potential.

But, at the same time, there’s a fallacy in believing that such striving and dreaming will land at a destination. That, if you could only reach a certain goal, find that perfect partner, become financially free, start a thriving business, that this would lead to a deep and enduring happiness.

It’s better to have these things than to be without them, that’s sure. But, in not having them, people chronically overestimate how much possessing them will permanently improve their moment-to-moment reality.

Therefore, I think the letting go of desires must also be in your daily practice.

In the first journey, I feel I’ve gone quite away. In the second, I feel as if I’ve just begun. But perhaps this is always how it is, with striving inevitably embodying a kind of personal history, to which one has been walking for some time. Abandoning craving, in contrast, puts the focus on this very moment, and thus one is always making the first step.

I’m more and more convinced that the answer to life’s enduring questions may end up being paradoxical. That inconsistent answers to life may be better than imbalanced ones which rigorously exclude all internal contradictions.

Thus, I think you should both cultivate your desires and abandon them. Stoke the flames of your striving and pursue the things you really want in life, in spite of your doubts and fears about them. But, at the same time, know how to release those same desires so they do not burn you.

The post Should You Desire More or Less? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 8, 2019

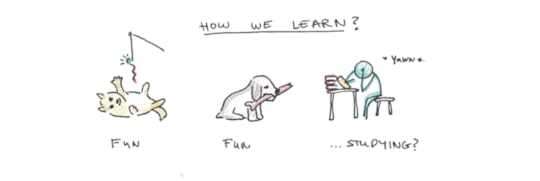

Play is Learning

Why do we play? Whether it’s games, sports or just joking around, people spend a lot of time playing. Children spend the most time playing, but we continue even after we grow up.

The simplest answer is that playing is fun. Games, sports, hobbies and other activities are enjoyable, and so we like to fill our spare time with play.

But this just pushes the question back. Why do we find play fun?

Animals play too. Dogs wrestle. Cats stalk. Animals of all kinds engage in behaviors we easily recognize as play. And, from this perspective, it’s easier to distance ourselves from the direct experience of playing and look at it from a more objective lens.

What we find is that play is about learning. Play is a way for animals to train skills—hunting, stalking, fleeing, raising children and socializing. Play is the same for human animals as well. Rather than being a superfluous leisure activity, play is important work building the skills which allow us to live in the world.

Why Don’t We See Play as Learning?

If I asked you to think of the best example of learning, I doubt many people would pick playing around. Learning is serious. Play is fun.

I suspect that the reason for this is that school has become such a central example of learning that we tend to think of learning in terms of activities that are most similar to academics. Reading a book = learning. Playing tag = fun, unserious activity.

Yet play is the original learning activity. We engage in it spontaneously because millions of years of evolution have found it to be the most useful way to learn important skills. In contrast, the scholastic mode of learning is and incredibly recent (and not always successful) mode of learning we haven’t been hardwired to enjoy.

Playing > Studying

A good reason for preferring play to study is that playing tends to encourage learning the way our brains actually work.

Consider learning to play a game, like chess.

A scholastic approach would begin with a lecture. You sit and listen as the teacher explains the piece moves, castling and en passant. Forks, pins and skewers. Zugzwang.

Then some homework assignments. Chess problems. Memorize opening patterns. “What is the King’s Indian Defense?” Problem sets to be handed in Monday, graded for the following week.

All this culminating in some kind of final exam—a thorough test of the definitions, concepts and ideas presented in the class, and no more. After all, to test you on something you hadn’t been taught would be unfair.

Compare this to just playing a lot of chess. Perhaps this latter strategy would miss some opportunities, but it does vastly better than the hypothetical chess pedagogy above.

The reason playing chess trumps the formal academic approach is that to play chess you must transfer knowledge and skills to actual games. Play, by simulating real chess, does this quite well. Study, by memorizing and reviewing abstract concepts, does not—and so it often fails to make an impact when you’d naively expect it would.

Your Study Should Be More Like Play

Nobody teaches chess this way. We understand that, at the very least, you must play some actual chess games. Memorizing concepts, definitions and abstracted problems isn’t enough.

But is this not how we teach languages? Mathematics? Science? History? The above formula is played out for most subjects, yet the critique for chess applies to them as well.

If you want to learn something deeply and well, your studying needs to look more like play. Fiddling with things. Inventing challenges and struggling to solve them. Imagining what-ifs, how-abouts and why-nots.

Play is how you were meant to learn. You enjoy play because you enjoy learning. Most people dislike formal study because, outside of the classroom, it’s not a terribly efficient way to learn.

Richard Feynman: Master of Play

It’s easy to think of games like chess as being learned by play. But how could you learn a serious subject, like physics, through play?

This, I’ll argue, is how famous physicist Richard Feynman learned it. It started as a child, repairing radios that had broken down. Tinkering and fiddling led to recognizing that you could solve things by thinking about them.

Later, as a student, he would invent problems for himself. Why does a spinning plate wobble the way it does?

Finally, it got applied to the deepest problems in physics, eventually winning him a Nobel prize.

Feynman is a vivid example, but most great thinkers, scientists and artists learned through play. Whenever you’re learning anything, if you can ask yourself, “How do I make this more like a game? How do I tinker, experiment, imagine and fiddle around with this?” you’ll be much better off than if you merely study.

The post Play is Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.