Scott H. Young's Blog, page 42

February 8, 2019

Play is Learning

Why do we play? Whether it’s games, sports or just joking around, people spend a lot of time playing. Children spend the most time playing, but we continue even after we grow up.

The simplest answer is that playing is fun. Games, sports, hobbies and other activities are enjoyable, and so we like to fill our spare time with play.

But this just pushes the question back. Why do we find play fun?

Animals play too. Dogs wrestle. Cats stalk. Animals of all kinds engage in behaviors we easily recognize as play. And, from this perspective, it’s easier to distance ourselves from the direct experience of playing and look at it from a more objective lens.

What we find is that play is about learning. Play is a way for animals to train skills—hunting, stalking, fleeing, raising children and socializing. Play is the same for human animals as well. Rather than being a superfluous leisure activity, play is important work building the skills which allow us to live in the world.

Why Don’t We See Play as Learning?

If I asked you to think of the best example of learning, I doubt many people would pick playing around. Learning is serious. Play is fun.

I suspect that the reason for this is that school has become such a central example of learning that we tend to think of learning in terms of activities that are most similar to academics. Reading a book = learning. Playing tag = fun, unserious activity.

Yet play is the original learning activity. We engage in it spontaneously because millions of years of evolution have found it to be the most useful way to learn important skills. In contrast, the scholastic mode of learning is and incredibly recent (and not always successful) mode of learning we haven’t been hardwired to enjoy.

Playing > Studying

A good reason for preferring play to study is that playing tends to encourage learning the way our brains actually work.

Consider learning to play a game, like chess.

A scholastic approach would begin with a lecture. You sit and listen as the teacher explains the piece moves, castling and en passant. Forks, pins and skewers. Zugzwang.

Then some homework assignments. Chess problems. Memorize opening patterns. “What is the King’s Indian Defense?” Problem sets to be handed in Monday, graded for the following week.

All this culminating in some kind of final exam—a thorough test of the definitions, concepts and ideas presented in the class, and no more. After all, to test you on something you hadn’t been taught would be unfair.

Compare this to just playing a lot of chess. Perhaps this latter strategy would miss some opportunities, but it does vastly better than the hypothetical chess pedagogy above.

The reason playing chess trumps the formal academic approach is that to play chess you must transfer knowledge and skills to actual games. Play, by simulating real chess, does this quite well. Study, by memorizing and reviewing abstract concepts, does not—and so it often fails to make an impact when you’d naively expect it would.

Your Study Should Be More Like Play

Nobody teaches chess this way. We understand that, at the very least, you must play some actual chess games. Memorizing concepts, definitions and abstracted problems isn’t enough.

But is this not how we teach languages? Mathematics? Science? History? The above formula is played out for most subjects, yet the critique for chess applies to them as well.

If you want to learn something deeply and well, your studying needs to look more like play. Fiddling with things. Inventing challenges and struggling to solve them. Imagining what-ifs, how-abouts and why-nots.

Play is how you were meant to learn. You enjoy play because you enjoy learning. Most people dislike formal study because, outside of the classroom, it’s not a terribly efficient way to learn.

Richard Feynman: Master of Play

It’s easy to think of games like chess as being learned by play. But how could you learn a serious subject, like physics, through play?

This, I’ll argue, is how famous physicist Richard Feynman learned it. It started as a child, repairing radios that had broken down. Tinkering and fiddling led to recognizing that you could solve things by thinking about them.

Later, as a student, he would invent problems for himself. Why does a spinning plate wobble the way it does?

Finally, it got applied to the deepest problems in physics, eventually winning him a Nobel prize.

Feynman is a vivid example, but most great thinkers, scientists and artists learned through play. Whenever you’re learning anything, if you can ask yourself, “How do I make this more like a game? How do I tinker, experiment, imagine and fiddle around with this?” you’ll be much better off than if you merely study.

The post Play is Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 7, 2019

Digital Minimalism

My long-time friend and mentor, Cal Newport, has just released a new book, Digital Minimalism.

The basic premise is one you’ve heard before: digital addictions, from social media to constant texting, have invaded our attentions, reduced our productivity and made our lives worse.

The antidote isn’t to smash your smartphones and live as the Amish do, but to embrace a deliberate philosophy Newport calls digital minimalism.

This philosophy is guided by the idea that we should be in control over what kinds of media we consume, not have our habits dictated to us by technology.

Taking Leisure Seriously

While Newport’s massively popular book, Deep Work, tackled the problems of our always-on connectivity as they pertain to work, Digital Minimalism does this for your personal life. Having deep work at the office, but digital addictions at home, is hardly a victory.

To resolve these problems, Newport argues we should all take our leisure time much more seriously. Instead of defaulting into the low-quality obsessions that leave us wondering where the time has gone, we should cultivate high-quality hobbies that lead to lasting satisfaction.

In order to have the kind of meaningful use of our personal time, however, we need to first re-evaluate our relationship to technology. Newport suggests first a period of abstinence, followed by a selective re-introduction of only those tools and technologies that pass a more rigorous cost-benefit analysis than we typically impose.

Addiction and Modernity

A substantial theme in Newport’s book, although usually under-the-surface, rather than extensively argued, is how modernity and addiction may go hand-in-hand.

The reasoning is simple. We evolved to live in a specific kind of environment. That original human society created our minds to seek certain things, which rarely ever became excessive to the point of vice: high-calorie foods, sexually-stimulating sights, social approval and new information.

However, in our modern world, due to our wealth and technology, we don’t have the same limitations. Therefore we seek out more of these things than we need, and our market economy scrambles to provide them for us.

As a result, addiction seems to be the inevitable consequence of our culturally-created environment changing faster than our biologically-hardwired brains. A cultural problem requires a cultural solution.

Unfortunately, our recent changes to society have progressed too fast, even for culturally-transmitted solutions to be proven and durable. Thus, I expect books like Newport’s, and others, will fill the void as we recognize collectively the need to generate innovations to counteract the problems of our own success at fulfilling basic desires.

My Reactions to Digital Minimalism

I liked this book a lot more than I thought I would. Although I love all of Newport’s writing, I use more social media than he does. I have Facebook, Twitter and Reddit accounts, and I feel like I get value from them.

I also police my online usage more than most. I use Leechblock on my computer browser, which prevents me from going over a pre-allocated limit on addicting websites. I don’t have Twitter, Facebook or Reddit on my phone.

Thus, I expected the book to mostly reaffirm what I already felt I was doing. However, after reading through the book, I got a chance to re-evaluate many of my habits and pass them over with greater scrutiny:

Rethinking Twitter. Twitter is a platform I love for the chance to hear from experts, academics, entrepreneurs and interesting people. But, it’s also a dumpster fire of toxic political controversies and culture war in-fighting. I used to think the benefits made up for the costs, but Newport’s book has made me seriously reconsider.

Being deliberate in my leisure time. Like most people, I’m often tired after work and just want to “relax.” However, that can easily devolve into spending time on things that don’t bring relaxation or meaning, but just waste time. Selectively blocking some tends to increase the influence of others. But putting your leisure time first, and taking seriously what kinds of activities you’ll engage in presents an opportunity to push out the waste through the opposite direction.

Am I really in control? Alcoholics frequently don’t think of themselves as addicted to drinking. Instead, they “like” drinking and could stop whenever they feel like it. They just don’t feel like it right now. While digital addictions aren’t chemical dependencies, they create reinforcing behavioral patterns so that not checking your smartphone every five minutes makes you feel a pang of discomfort. I’m no longer sure you can safely evaluate your media consumption, while you’re in the midst of it. Newport’s advice to step away for a month may be necessary to see your habits objectively.

The reason I loved the book, however, wasn’t a specific tactic he recommends or a specific, new idea, but that it paints a different vision of what your life could be like. A life strategy that is slower, less anxious, more meaningful and deeply connected to the things you care about.

This picture of life really resonates with me, and if it sounds like it will for you too, I strongly recommend reading Digital Minimalism.

Note: Cal Newport gave me a free digital copy of his book, so that I could read it in order that my review would appear online.

The post Digital Minimalism appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 6, 2019

Follow Me on Instagram

I’ve created an Instagram account!

If you have Instagram and would like to get snippets of my life, summaries of articles (with my hand-drawn images) and other things, you can follow me here:

https://www.instagram.com/scotthyoung/

I’m still pretty new to publishing on this platform, so the more people follow/engage, the more I’ll be able to try to do.

Just a reminder, in case you’re not aware, you can also follow me on Twitter, Facebook and WeChat (in Chinese) too!

The post Follow Me on Instagram appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 5, 2019

How to Find Time

There’s never enough time.

You want to exercise, eat well and be healthy. But the day slips by and you don’t go to the gym. You eat that muffin for lunch, instead of the salad you thought you would.

You want to do great work, advance your career, produce something meaningful. But your email inbox is overflowing. A coworker drops by to, “ask a quick question.” Soon the working day is done, and you’re exactly where you were the day before.

You want to learn a language, guitar, to paint or martial arts. If you could just put time in consistently, you could make it happen. But it stops more than it starts, and years go by while it remains just a notion.

Where to Find Time

The first thing to realize is that time is rarely the problem. Yes—it is limited. But your attention, energy and enthusiasm is more limited than that.

Thus start creating habits. Inertia is a bigger enemy than a lack of time. You’ll be surprised how much materializes, once you simply start doing the things for a few minutes a day.

The second thing to realize is that a list of unfulfilled things isn’t a problem to eliminate. It’s our challenge as human beings to experience finite lives in an infinite world. To pick one thing, out of innumerous possibilities.

Thus prioritize your goals. Say no to the things that don’t meet your criteria. Start with saying no to the things you don’t even realize you’re saying yes to right now. Above all, be content with having done one thing that mattered, rather than a dozen which do not.

The third thing to realize is that our fears and frustrations unconsciously drive what we have time for. The fear of getting started, making a mistake or looking foolish conspire in the background to leave, “I have no time,” as the most attractive excuse.

Thus put your fears first. If it is important, do it. If it is unpleasant, do it now. Facing down the things that scare you has the unintended effect of those same things turning out to be not so scary after all.

You Have the Time

Not for everything. Not even for most things. But for the things that matter.

Maybe you only have a few minutes each day. Then use those few minutes.

Maybe it’s fragmented, distracted and prone to interruption. Then cut it up, spread it out and let it be put on pause.

Just don’t let it slip away unknowingly, another day without a moment spent on the things that matter most to you.

The post How to Find Time appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 4, 2019

How to Cultivate Mental Stamina

One of the common questions I get asked about my ultralearning projects, such as the MIT Challenge, is how to keep up hard mental effort for long periods of time.

During that project, for instance, my starting point was to study for 11-12 hours per day, five days a week. Starting at six in the morning, I’d wake up, and begin watching lectures, doing problem sets or otherwise preparing until five or six at night.

In the Year Without English, my friend and I made a point of not speaking English to learn languages. Although the difficulty eased as we improved, each new country put us in a situation where we were strained non-stop for a few weeks, as our abilities were too minimal to say almost anything without a dictionary or translation app.

Mental stamina—of continuing your focus on hard, intellectual problems for weeks or months at a time—is an essential skill for learning important things. If you surrender to frustration and fatigue easily, then you’ll chronically be fighting a war with yourself to do the work you need to.

Strategies for Cultivating Mental Stamina

Since building up my endurance on tough mental problems has been an important goal of mine for awhile, I’d like to share some of my strategies that have worked for me in reaching this goal. Experiment with all of them, and focus on the ones which work best for you.

Strategy #1: Create an Obsessive Quest

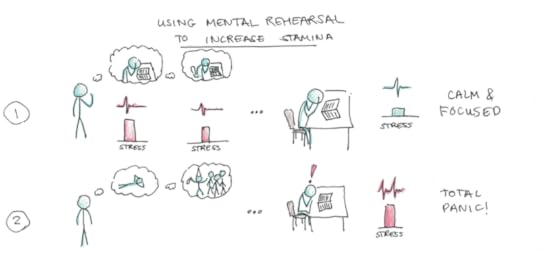

In my mind, mental stamina is as much about preparation as it is about endurance, after the fact. In all of the projects where I successfully sustained a long period of mental work, I also spent considerable time obsessing, rehearsing and preparing for those challenges.

The MIT Challenge began in September 2011, but had begun thinking about it, planning and visualizing it as early as March of that year. Therefore, when the classes hit me, and I was pushed to study many hours per week, the strain and fatigue didn’t feel nearly so difficult.

For my thirtieth birthday, I went bungee jumping with some friends. The surprising thing is that I used to be terrified of heights. Even as a teenager, I’d avoid standing too close to windows in tall buildings, or my palms would get sweaty. So jumping off a gorge on my own was definitely a tough mental challenge.

Before the jump, I was worried that I would freeze when I stood by the edge. So, for nearly a week before, I imagined standing and taking the jump. Each visualization had my heart racing, yet, when it came time to finally jump I didn’t freeze. (I didn’t end up visualizing the fall though, so that ended up being much scarier than the initial jump had been!)

This strategy of visualizing and mentally rehearsing anxiety or stress-inducing moments has been demonstrated psychologically to help with performance. The problem with mental stamina is that you’re going to have feelings of strain, frustration or overwhelm. But if you start mentally planning for them well ahead of time, when they actually do occur, they’re much more manageable.

Strategy #2: You Can Always Just Sit

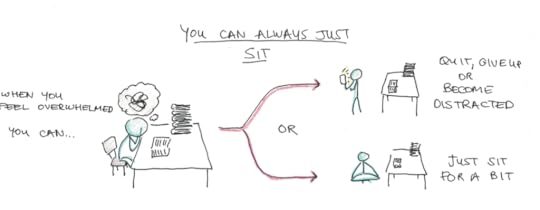

In encountering a frustrating problem, there’s an immediate impulse to flee. Our nervous system is hardwired to handle threats as if they are tigers, crouching in the bushes. Yet, such responses are not particularly helpful when the problem to overcome is calculus.

One solution I’ve found particularly helpful in these moments is that whenever I felt overwhelmed by a problem, I could always just sit there. Meaning, I could temporarily shut off mentally from the problem and just sit, quietly.

While this is obviously an option available to all of us in mentally straining situations, it’s not usually our first reaction. We want to get up, do something else and distract ourselves with phones and Facebook.

Just sitting, however, reminds you that the strain you face is largely an invisible one. It’s not a tearing of your muscles or pulling of your joints. It’s an anxiety about your upcoming test, a frustration in a problem you don’t understand or a fatigue from working hard all day. Releasing yourself from those emotions, just for a moment, and doing nothing, can help you get a better grip on them.

Strategy #3: Create Positive Feedback Loops

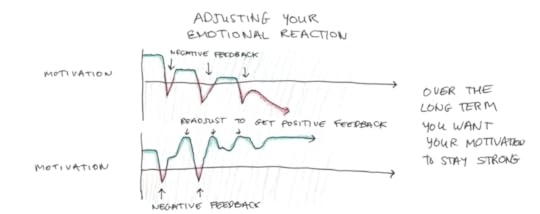

Although mental stamina was a key ingredient in all of my challenges, the truth is, most of the time they flowed fairly well. I didn’t feel frustrated, anxious or upset, just pleasantly challenged.

Thinking about those moments, I think a big reason why they felt that way was because I had built up a cycle of solving the problems I faced. When I’d encounter a subject I didn’t understand, I didn’t panic, because I had succeed to understand similar concepts before. Similarly, when there would be a hard test, I felt confident that I could master the techniques.

This confidence cycle is important for many things in life, but I think it’s particularly important for your stamina. When you feel encouraged to go forward, the effort required to keep going is far, far less than when you feel beat down at every turn.

Cultivating these positive loops is part challenge selection and part expectation. Selection, in that you should pick activities and tasks that challenge you, but don’t overwhelm you. If you feel totally put off from even trying, pick something a little easier and try again. Increase the challenge until you find it straining, but not completely unpleasant.

Expectations, however, are also quite important. Because I approached my challenges under strange constraints, I often didn’t expect to succeed. The status-quo for tackling a class in five days, or a language in three months, wasn’t success, so when I felt frustrations or difficulties these seemed totally normal.

In contrast, students who struggle in school systems often think to themselves, “Why is it so hard for me? If I’m struggling so much, I must be dumb.” This attitude encourages you to give up and find something where you’re better suited, even if almost everyone in the class privately feels this way!

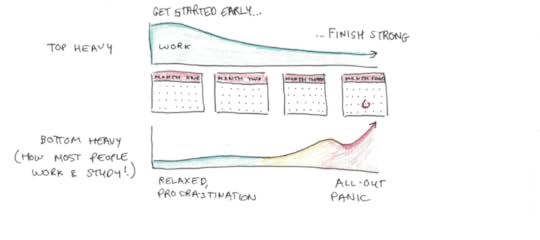

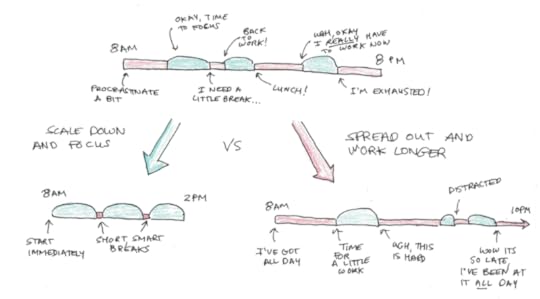

Strategy #4: Make Your Attack Plan Top-Heavy

In all my projects, I expected to get tired. I expected to lose motivation and start to be a little less willing to work hard. But, I tried to compensate for this by making my initial plans a bit harder and faster-paced than expected. Thus, as I naturally got a little more fatigued, what I needed to stay on schedule got a little more slack.

In the MIT Challenge, my initial starting pace was one class per week. At thiry-two classes over a fifty-two week year, this is slightly faster than necessary. So later on, I took classes more slowly, and spread out over time.

It turns out that this worked out perfectly, because my initial 11-12 hour studying sessions were unsustainable. After about ten classes, I was getting more fatigued, and I couldn’t sustain them. Switching to seven or eight hours was necessary, but also possible because of my initial plan.

Strategy #5: When in Doubt, Shorten the Time

A common story I’ll hear is from students, panicking because of an upcoming exam, studying for every waking moment. They will tell me that they’re studying fifteen hours or more, seven days a week, in order to reach their goal. They’re cutting sleep, losing exercise and pulling out their hair just to stay on track.

Except, in the same email, this same student will complain about procrastination. That they can’t be motivated to continue. That they easily get distracted and can’t seem to focus on their studies.

So which is it? Do you study all day or are you procrastinating all day?

Somehow the internal contradiction between these two statements isn’t obvious to the student. To them, they think that their tendency to procrastinate should mean they need to work even more, to make up for their own flagging willpower.

This is entirely backwards. Your stamina is what it is. You can take the above strategies to extend it, certainly. But some goals will naturally cultivate within you a steadfast endurance, and others will be painful and require prodding. Some people may have more natural mental stamina for some tasks than others.

The solution to continuous distraction, procrastination and poor quality attention isn’t to inject more hours into your schedule, but to apply less. Concentrate your studying into shorter bursts of time and give yourself more time for rest, sleep, exercise and self-care. Force yourself to study only five or six days a week, instead of seven.

Then, from this more limited, and constrained starting point, aim for total absorption. Start immediately when you tell yourself to start, eliminate any outside distractions and work on the hardest, most challenging mental problems.

Once you successfully work with pure concentration for the time you allocated for yourself, you can try stretching the timeframe a little more, but not before. If the concentration time you’ve allocated is not enough to succeed in your goal, then you won’t succeed in your goal. I’m sorry to say that, but switching from a dedicated and pure focus, to a hazy and haphazard one over slightly more hours certainly won’t do the trick, so don’t bother.

The only chance you have of reaching the finish line is to start from a base of relatively high-quality concentration and build up, rather than one full of procrastination, guilt and endless distraction to which you respond with an even more demanding schedule.

The Merits of Mental Stamina

These metacognitive strategies for mental stamina are not the complete picture. Natural aptitude, interest and environment all make a difference and, yet, are somewhat outside your control.

However, mastering whatever you can is still enormously beneficial. Mental stamina is essential for success in school, work or any intellectually demanding task. The higher your threshold for quitting due to frustration, the more things you can master.

The post How to Cultivate Mental Stamina appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 1, 2019

Unraveling the Enigma of Reason

My favorite book of last year was Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier’s The Enigma of Reason. I covered it in my book club as a podcast, but the ideas are so interesting that I wanted to take a second chance to explain them.

The basic puzzle is this:

If reason is so useful, why do human beings seem to be the only animals to possess it? Surely, a lion who had excellent reasoning abilities would catch more gazelles? Yet human beings seem to be alone in the ability to reason about things.

If reason is so powerful, why are we so bad at it? Why do we have tons of cognitive biases? Reasoned thinking is supposed to be good, but we seem to use it fairly little as a species.

Unraveling the Enigma

The answer to both of these puzzles, which has far-reaching implications for how we think and make decisions, is that we’ve misunderstood what reason actually is.

The classic view of reason is that it is simply better thinking. Reasoned thinking is better than unreasoned thinking. Being able to reason means being smarter—a kind of universal cognitive enhancement that is good for all types of problems. Sure, we don’t always use it and it can be slower than intuitive judgements, the classic view goes, but reasoning is always good.

Sperber and Mercier, argue, in contrast that reason is actually a very specialized cognitive adaptation.

The reason other animals do not possess reason is because they don’t have the unique environment human beings exist in, and thus never needed to evolve the adaptation.

The reason human beings often don’t use reasoned thinking is that our faculties of reason are actually much more restricted in their use. We use it only when necessary, and otherwise adopt the same strategies animals use to make intelligent behavior.

What’s the Point of Reason?

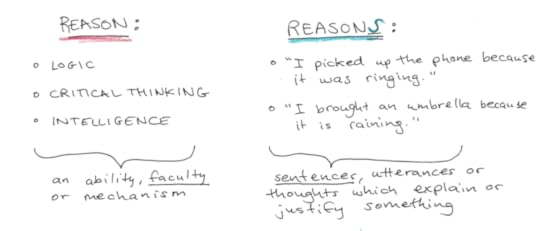

According to Sperber and Mercier, the purpose of reason, as a faculty, is for generating and evaluating reasons.

This may sound almost tautological, but these two words, reason and reasons, actually refer to very distinct things.

Reason is a faculty. An ability we possess. Near-synonyms might include logic, critical thinking or analysis.

Reasons, in contrast, are explanations, usually given in the form of sentences. “Because it is raining,” is a reason for bringing an umbrella outside. Reasons, such as this one, do not refer to the general capacity of human beings to decide to take umbrellas when it rains, but rather the explanations that justify such behavior to other people and oneself.

What Sperber and Mercier argue is that the human faculty of reason largely isn’t to create intelligent behavior. Instead, it serves to justify and explain that behavior. In short, we have Reason to create reasons. Those reasons aren’t mostly for ourselves, but to make our behavior comprehensible and justifiable to other human beings.

Animals don’t need this faculty because, without language, there is nobody to hear the reasons they might have. Human beings don’t use reason all the time, because, our decisions about what to do are mostly generated by other, intuitive processes, and reasoning is added after.

Mental Modules and How You Think About Things

A popular view of the brain is the modular theory of mind.

This view says that rather than being a unified whole, the brain is better thought of as broken down into distinct modules. Each module takes inputs from other parts of the brain, and gives outputs to other parts of the brain, and each module specializes to its own specific functions.

One metaphor for this might be to imagine comparing a big factory that makes gadgets from scratch, on a big conveyor belt. Now compare this to a bunch of separate companies that each make parts of the gadgets, and they get put together only at the end. Mental modules are more like this last picture, with each separate company being somewhat separate from the others, rather than a big unified conveyor belt of thinking.

Fitting in with this view, reason, according to Sperber and Mercier, is a separate mental module. This module has two functions:

It takes situations and generates reasons for them. So if you were standing with your umbrella, and someone asked you “Why are you carrying that?” your reason module might generate a few candidate answers, before arriving on, “It’s raining outside,” as being a good one.

It evaluates the reasons of others. In this way, you can also take the reasons given by other people and decide whether they are good or not. If I asked you why you’re carrying an umbrella and you said, “Because it’s Monday today,” that would not seem to be a good reason.

Important in this theory is that the decision to carry an umbrella itself needn’t be decided by the reason module. This might be a different module of the brain, that through past conditioned experience, generates the motor commands to grab your umbrella before leaving the house. The reason for why to carry the umbrella, in terms of an actual sentence or thought, may only occur later, upon being asked by someone (or anticipating being asked by someone).

Opaque Processes and Reasoning

One coincidence I find very persuasive in terms of arguing for this view of reason comes from machine learning.

A common critique of machine learning is that it is not introspectable. Meaning, if an algorithm decides to approve a loan, change a price or order a drone strike, human beings often don’t know why it made that choice. Even the designers of the algorithm itself often don’t know what were the causes of its decisions, even if it tends to make them accurately overall.

One proposed solution to this problem has actually been to make two systems. One makes the decision, the other trains itself on the patterns of the first system to generate “explanations” of the former. This way, a complete machine learning system could justify its choices.

The coincidence here is that this is exactly what Sperber and Mercier argue is how human brains actually work!

We also have a bunch of opaque algorithms that may be trained in ways not dissimilar to the machine learning algorithms. The fact that machine learning algorithms often describe themselves in terms of “neural” networks, uses their superficial similarity to the brain as a metaphor for their operation.

We too, also need to justify our behavior to outsiders so that it appears in keeping with how our society works. If we appeared to do things without any apparent reason, or worse, a reason that is not valid for that social situation, we may be seen as crazy or evil.

Thus, evolution fashioned us too with a second module, that takes our intuitively-arrived-at decisions and generates something that we can communicate with language to outsiders so that they can try to evaluate why do what we do.

Implications of Sperber and Mercier’s Theory

There are too many implications of this idea to easily fit into a blog post. Best to read the book itself.

However, I want to showcase a few of the most important implications of this theory, if it is true.

1. Reasoning isn’t a big part of intelligence or (potentially) consciousness.

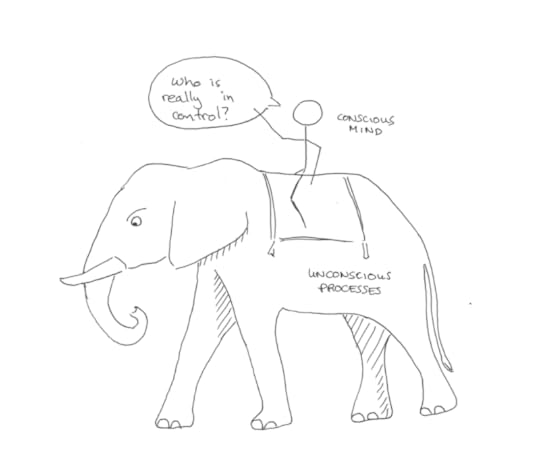

One common view of psychology is described as the elephant and the rider. We are the riders, loudly proclaiming where we want our behavior to go, yet it is really the elephant, the unconscious mind, that is the driving force.

This view has often been used to disparage the idea that we have much control over our lives or decisions.

Although the essence of consciousness is still debated, I think this new theory upends some of this view of the mind. In this view, there is no rider. Reason itself is just another module in the mind, providing specialized support for specific tasks. In other words, it’s intuitive, opaque processes all the way down.

A better metaphor might be of starlings. These birds fly in amazing patterns, but the behavior emerges out of each bird doing a smaller part. There is no bird who dictates the pattern of flight to others, like a rider might tell an elephant where to go. There is also no cohesive whole to ignore this order, like a willful elephant might ignore its rider. Instead, there’s a bunch of smaller parts (modules), all doing their own purposes, contributing to a more intelligent behavior at a larger level.

2. It’s possible to have smart decisions, but not be able to have reasons for them.

In a classic view of reason, having no reason for an action makes it almost certainly a bad one. Unless it happens to randomly be correct, there’s no reason to trust it if there is no reason behind it.

Sperber and Mercier, in contrast, completely flip this view. If reason exists to generate reasons, then there are potentially tons of smart decisions that we struggle to generate good reasons for. Therefore, ignoring one’s reason and acting without it, is not necessarily maladaptive (unless you get confronted about your behavior by others).

I don’t think this implies we should make every decision on intuition alone, but it does put a big hole in the project of “rationality” as a self-improvement goal. If rationality is really mostly about rationalization, then the idea of working hard to make more of your behavior in line with your “reasons” is a fundamentally flawed one.

3. We are smarter when we argue than when we think alone.

Sperber and Mercier call their theory the “argumentative theory” of reason. This is because they claim that the function of reason is to provide socially justifiable reasons for beliefs and behaviors. This also explains why we have a strong my-side bias, looking to justify our beliefs rather than challenge them—this is what reason is actually for.

However, the power of reason, and why reason produces such wonderful things as technology, science and human progress, is that collectively, our individual weaknesses cancel out. You may not persuade your opponent in a debate, but the audience is listening. In the end, good reasons win out over bad ones in the broader sphere of discussion.

4. Feedback loops may explain the role of classical reason.

This explanation may seem like it dismisses too easily the focal example of classical reasoning: smart people thinking carefully to arrive at a hard-won, but brilliant, insight.

However, when we see that reason can both generate and evaluate reasons for things, this forms a potential feedback loop. You can take the reasons you generate yourself and then evaluate them. If you expect push-back, you may reject those initial reasons and dig deeper to try again. This may even push you to change your intuitive beliefs, if you are unable to come up with a suitable justification.

This actually happens all the time when you have to explain something to a skeptical audience. You may rehearse several different explanations before settling on the one you think is the most justifiable reason.

This back and forth, combined with the ability for a reason module to override intuitively-made decisions, provided they can’t be sufficiently justified, may explain, in a dynamic sense how Sperber and Mercier’s theory of reason flowers into the classical reason under specific circumstances.

5. You will reason better if reasons are harder to provide.

Better, this theory also explains why this kind of deep thinking is so rare: normally we aren’t dealing with such a skeptical audience! We’re satisfied with sticking with the first reason that pops up, not searching and evaluating and possibly even changing our beliefs when those first intuitions are shown to be unjustifiable.

This may also explain why scientific communities reason so well. The audience is extremely skeptical, and sets narrow constraints as to what kinds of reasons count. This makes such narrow wiggle room, that often it is easier to override an intuition, than to provide an acceptable reason for a bad intuition.

This may also give a potential improvement tip for performance in reason-based domains. The higher standards you imagine your audience will have, the better your thinking will be. It will force you to go over and over your thoughts with a fine-toothed comb, rather than simply state your intuitions and leave it at that.

A corollary for this, however, might be that if the constraints are too narrow for reason, it may lead to rejecting “good” answers, that don’t fit the reasons they contain. Dogmatism may be an inevitable side-effect of reason as the structures that force reasoning into specific channels may ultimately divert it from the truth.

Concluding Thoughts

In the end, our minds are not separated into a war between a ruling, but often frail and feeble, reason, and a willful unconscious. Instead, it is split between many, many different unconscious processes, each with their own domains and specialized functions, with reason standing alongside them.

In some senses, this is a demotion of reason, from being a godlike faculty that separates us from animals, to being just one of many tools in our mental toolkits.

But in another sense, this is a restoration of reason, since instead of appearing like sloppy, feeble and poorly-functioning faculty, it appears as if reason does exactly what it was designed to do, and it does so very well.

Although there are many implications of this idea, it is how it changes how we conceive of ourselves that matters to me most of all. If we are not the rider on the elephant, but the murmuration of starlings, then our selves are both more powerful and also more mysterious than they first appear.

The post Unraveling the Enigma of Reason appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 31, 2019

The Three Different Types of Luck

Luck is obviously an important consideration if you’re aiming to be successful at anything.

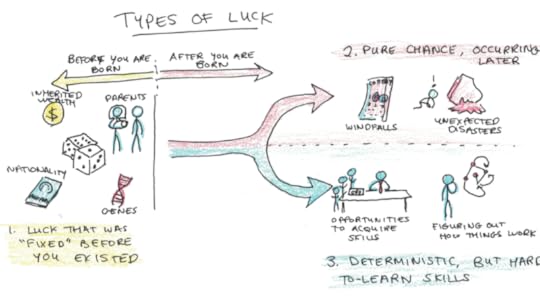

But what does it mean for someone successful to be lucky? I can think of three main ways.

The first is when the element of chance occurs before that person comes into the world. This kind of luck is pervasive and common. The child of rich parents becomes rich herself. The person born with extreme intelligence becomes a professor. You’re beautiful, and thus become a famous actor.

This kind of luck speaks to an unfairness that exists in this world. Where we are born. Who are our parents. What abilities, talents, fortunes, genes, beauty and other privileges we’re given in greater or lesser amounts than others.

The second kind of luck occurs after, but it is still impossible to predict or control. Getting a lucky audition that propels you to stardom. Happening to invest in a company before they hit bit. Winning the lottery.

The third kind of luck also occurs after you’ve come into the world. However, the outcomes you experience are entirely deterministic. The reason some people succeed and others fail, however, is success is confusing and difficult, so what you may lack is skill and knowledge.

Serial entrepreneurs, who successfully start multiple successful businesses, in my mind, fit this third idea of luck. They know something others do not which allows them to succeed even though success appears to be based heavily on luck to outsiders.

How Unfair are The Three Types of Luck?

Depending on the perspective you adopt, and your purpose for talking about luck, all three of the above are quite unfair.

Certainly accidents of birth result in great unfairness. Warren Buffet famously remarked that his greatest piece of luck was to have been born in the United States.

Having won this “ovarian lottery” allowed him to become a rich investor. Had he been born to a poor farming family in the developing world, he would not have become the world’s richest man.

Obviously luck caused by pure randomness is also unfair. But so is luck caused by difference in knowledge. Those who gain access to the right environments, mentors or situations may get into feedback loops which allow them to learn their way to success, while others are excluded.

Still, although this birds-eye view of luck from a perspective of fairness is one way of looking at it, that’s not the only way.

What Luck Means to You

The first kind of luck is unfair, true. But in another sense, it has already been rolled for you. Knowing who you are, your abilities, advantages and disadvantages, you already have good information about how lucky you were.

From this perspective, I believe it is fair to say that who has the intelligence to become a superstar scientist is based a lot on luck. However, I also think that once you consider who you are, it switches to being mostly based on hard work. Why? Because once you’re in a position to consider this goal, then the residual variation is based a lot more on your effort, tenacity, ambition, etc..

This means, for an individual pursuing goals in the world, I think luck is not nearly as large a factor as it is for considering the issues of society-wide fairness. This is because the kinds of dreams and goals we have, are often unconsciously constrained into the things we at least plausibly have the prerequisites for.

Luck from Intrinsic Randomness Versus Insufficient Knowledge

Once you’ve gotten past all the luck (or unluckiness) you must have already passed through merely by existing in the world, the two further types of luck suggest very different approaches.

For luck based purely on chance, there’s little you can do. The only rational thing is to diversify your options, take more chances and pick a path that has a level of risk and expected outcome you can stomach.

However, many areas of success depend a lot more on luck of the second type, where the process generating different outcomes is deterministic, but often difficult to master. In this case, doing everything you can to immerse yourself in the environment, learn more, and perhaps more importantly, last long enough for the effects of learning to kick in, becomes essential.

The Attitude You Should Take in Life

My feeling is that these different types of luck should suggest a few things to you:

1. Humility and compassion.

Because much of luck in the world is of the first type—being endowed advantages (or disadvantages) that are baked into who you are as a person—there will be considerable unfairness in society.

As such, we should always strive to be humble in our successes and compassionate to those who struggle (including ourselves).

2. Adjusting our ambitions to our endowments.

This happens automatically. I don’t think that I need people who feel like they struggle to “dream less,” because millions of years of evolution have hardwired exactly that. When we see we are good at things, we increase our ambitions. When we struggle, we decrease them.

If anything, our sense of possibility is likely too narrow. It is overly informed by our past experiences and doesn’t leave enough room for change.

However, given that this process occurs naturally, it also suggests that, within the range given to us by our experiences, luck matters a lot less. While I’m never going to be an NBA player because I’m neither athletic or tall enough, that was never a dream of mine. But starting a business was something I thought I might be able to do, and given that this lay with the range of possibilities given my starting point in life, whether I actually did it or not was based a lot less on random chance than on doing the work.

3. Smooth future-oriented luck out by replacing it with learning.

Whatever luck remains in your future, as opposed to already having been given to you when you came into the world, this is something you can try to minimize by learning more about how the world works (so you can take control over the deterministic portion of this luck) and taking enough chances (so you can reduce the variance on the stuff that really is random).

The combination of these two things to me suggests a picture where we admit the broader role of luck in society, and don’t implausibly suggest that we ourselves came to everything we are from identical starting points, yet at the same time don’t see our future goals and ambitions as being primarily occurring because of random chance, instead of hard work and mastery.

The post The Three Different Types of Luck appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 30, 2019

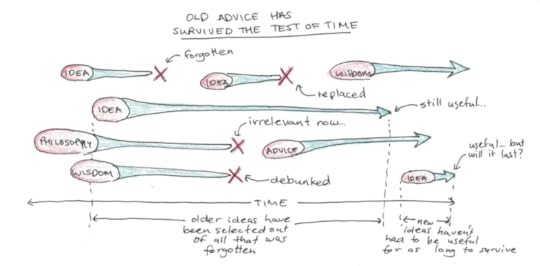

Is Old Advice Better?

Should you pay more attention to wisdom, when it comes from an ancient source? Or should you stick to advice that heeds closer to the scientific principles and moral scruples of our current time?

Some argue that ancient wisdom is definitively better.

There are some good reasons for this.

First, there’s probably a filtering effect where bad advice gets lost over time. Newer advice, being more recent, has yet to prove itself as being useful for solving perennial human problems.

The Stoics, Buddhists and early philosophical and religious scholars created words than people still follow today, this makes their claim to usefulness much higher since so many other words in the intervening millennia have been lost.

Second, older advice may not be tainted with self-promotion. Although philosophical pioneers, centuries ago, likely had their own biases which shaped their worldview, one of them, presumably, wasn’t to sell you stuff. Modern self-help authors, business gurus and other pundits all have their own motivations, which may not be nearly so pure.

Finally, older advice might simply ignore fads. Modern writers, driven by what’s new, may miss what is important. Focusing on self-centered millennials, social media trends and shifting technology may be newsworthy, but it ignores the bulk of our human nature that is unchanging.

Why Might Older Advice Be Worse?

Despite these benefits, I can also think of a few arguments for why newer advice may be better than older wisdom.

If you believe in intellectual progress, both scientifically and ethically, then earlier times are less likely to produce something of value. Aristotle believed the body was composed of earth, wind, water and fire. The Buddha believed that acting like a dog would reincarnate you as one. And neither seemed all too worried about the slaves people possessed around them.

Even if you believe that progress is an illusion, and there’s only a shifting set of culturally specific standards for judging truth and ethics, it may still make sense to read more modern works since those are more likely to adhere to the prevailing ideas of your time.

Another reason for believing in newer advice is that newer advice can inherit the best qualities of older wisdom, while ignoring its flaws. Paradoxically, this creates a market for “new” advice, that promotes itself as being ancient. Many self-proclaimed Stoics are more familiar with Ryan Holiday than Aurelius, and many Buddhists read modern gurus rather than the Pali Canon.

This may be a good thing, since it allows older advice to be updated to fit a more modern context, making it easier to understand (since the metaphors and context can be updated to current assumptions) and also modifying it to remove elements that are seen as antiquated or harmful.

Is Older Advice Just a Status Signal?

A third view, not mutually exclusive with the two I’ve outlined above, is that older advice is popular because it is seen as higher status than newer advice.

Consider Shakespeare. Many believe he has produced some of the finest works of literature of all time. Yet, most people would prefer to read a Harry Potter novel to Othello, if given the choice. Shakespeare, good or not, might attract this reverence because reading him is hard, particularly for a modern reader.

Since reading him is hard, having read his works signals that you’re probably smarter, more educated and cultured than average. Thus, what reading him says about you ends up becoming associated with the intrinsic value of reading Shakespeare itself.

Similarly, pulling a self-help book with a glitzy title is easy. Wading through centuries old texts is much harder. Therefore, older advice may inherit a sheen of respectability, not because it is intrinsically better, but because the types of people who end up reading it are better, and thus it gains from the signal it tends to send.

Of course, this could be true, in part, without invalidating the usefulness of the advice. I tend to think Buddhism gets too much credit because it’s very old and culturally exotic, but I also think there are useful ideas within.

What Biases Ancient and Modern Advice?

Perhaps the best answer is simply to diversify! Both modern and older wisdom have their biases and flaws, and the best solution is to draw from a diverse set of sources.

I suspect a lot of modern advice suffers from inconsistent quality, overreaction to temporary trends and is often blurred with the financial motives of the author. These can create biases which make the advice less-than-perfect.

However, I think it’s also a mistake to view older advice as somehow being free of biases, even if the authors no longer gain financially from their words.

As I wrote about in my review of the Dao De Jing, it’s important to recognize the context for this work—that of advising a ruler. This was the place of the philosopher in this time period in China, so rather than self-improvement, much of Confucius and Laozi is really a kind of nascent political theory.

Similarly, the Buddha existed during a time when many different ascetics from the sramana movement were all competing with different philosophies. Much of his ideas and advice were responses to the typical practices of the time, and this background context (and a desire to convert followers) is present in much of the advice.

These biases aren’t necessarily a big problem, just that if you pretend ancient advice is necessarily pure and modern advice overly tied up in our modern context, it may simply be that you aren’t familiar enough with the context that older advice was entangled with!

What do you think? Do you think older, ancient advice is more useful for some of the reasons I’ve described (or may some I didn’t)? Or do you prefer modern ideas that are based on sounder science and contemporary values? Share your thoughts!

The post Is Old Advice Better? appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 29, 2019

How to Take Notes While Reading

Note-taking is an incredibly powerful tool for learning.

Notes extend your memories. I’ve explained before how writing can be seen as an external enhancement of your brain, allowing you to think more complicated thoughts and solve harder problems. Notes you keep, therefore, act to expand your memory.

Notes enhance your focus. The act of taking notes ensures your mind isn’t wandering. Even better, notes can facilitate deeper processing of the material, which has been shown to improve memory than when you pay attention only to the superficial details.

Unfortunately, note-taking is often easier and more natural when you’re listening to something, than when you’re reading.

Why Taking Notes While Reading is Harder

Taking notes while listening is generally easier because, while listening, your hands and eyes are free to jot down notes. On the other hand, switching away to take notes while reading inevitably interrupts the reading flow.

This interruption leads to a trade-off. Too few notes and you give up the powerful cognitive enhancements that note-taking provides. Too many notes and your reading speed slows to a crawl.

What should you do?

How to Take Notes While Reading

I’d like to explain my thinking process of taking notes while reading. Follow these steps and you can find the right way to take notes for your situation.

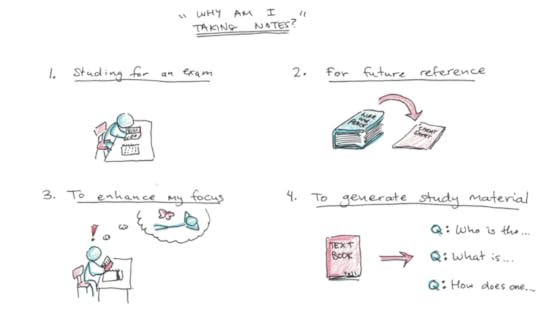

Step One: Why am I Reading?

The starting point of any note-taking technique has to be the purpose of whatever you’re trying to read. Why are you reading it in the first place? Why are you trying to take notes? What are you hoping to achieve?

These questions matter greatly, because different purposes are better served by different methods.

Consider two different situations. In one, you’re studying from a textbook. You want to take notes because the textbook is too long to easily review, and you want to prepare for an upcoming test based on the material it contains.

In the second situation, you’re a journalist, doing research to write a piece. You’ll go back to your sources when you write the final article, so your goal with taking notes is to make this job easier on yourself later.

In my experience, these two situations suggest different note-taking techniques, which I’ll go into shortly.

Before that, start by asking yourself why you are reading what you’re reading. In particular, ask yourself:

What am I trying to remember? (Alternatively: What do I think I’m going to forget?)

How am I going to use this information? (e.g. on a test, cited in an essay, as background for deeper thinking, etc.)

What do I plan to do with the notes later? Will you be studying off of them extensively? Keeping them in your records, just in case, but otherwise not looking at them again? Or maybe you’re just taking notes to stay focused, and it’s highly unlikely you’ll look through them after?

Think about your answers to these questions as we go through the next steps.

Step Two: Facilitating Focus

The first purpose of notes should be to enhance your concentration on what you read. This is especially true when taking notes from written material, because, in most cases, you’ll be able to go back and read the original source in case your notes were incomplete.

You want your notes to do the following:

Make it easier for you to concentrate on reading. A small amount of note-taking can prevent your mind from wandering.

Focus your mind on the right level of information. Are you trying to meticulously store details from a text? Or are you trying to get the gist of the argument put forth by the author? How you take notes also reinforces what you pay attention to.

Create a document that you can reference later to review, study or find information. Notes can also serve as a cheat-sheet for finding things you later forgot.

A few strategies I do to take notes while reading that helps with this are:

Jot notes in the margin. These aren’t particularly searchable (if the book is text, not Kindle), but they allow me to reiterate the main idea, so I can convince myself I understood it.

Keep a small notepad on the side, take breaks each section to jot down the main ideas. This, again, helps force me to focus on what are the higher-level ideas.

Creating flashcards. In the rarer situations where memorization of details is important, then a simple strategy can be to just create flashcards while you take notes. If I’m learning a language, anatomy or am given long lists of details I need to master, this can be better than trying to write them down and transfer them to flashcards later.

The important thing to keep in mind is that text, unlike live lectures, is usually searchable later. So your notes, to be effective, should strive to enhance your focus first, and only secondarily, be a document that is pretty and easy to review.

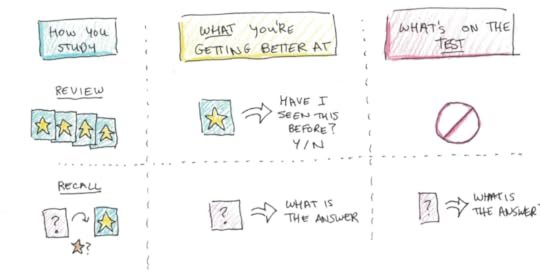

Step Three: Review or Recall?

If you expect to have to study the same material multiple times to fully master it (say it’s for an exam) then, you can save time by integrating your note-taking and retrieval practice efforts.

Retrieval practice is a well-supported practice that greatly enhances your memory compared to simple review. This technique is simply to try to recall as much as you can from the text, either by having prompted questions and answers, or just writing as much as you can on a blank page.

Retrieval works far better than review, where you look at the notes you wrote down multiple times. This is because review merely aids recognition, which isn’t very useful for most practical applications. Retrieval, in contrast, practices your ability to summon up memories when you need them—exactly the ability you need for tests and real-life situations.

Therefore, if you expect to study the material multiple times, it may be in your benefit to use the Question Book Method. This method simply encourages you to take your notes as questions, rather than as statements. Then, when you review your notes, you can answer those questions instead of just reading the information—aiding retrieval and making your studying time more efficient.

Side note: One trap students can fall into when using this method is copying down a bunch of irrelevant details as questions, and missing the big picture. A good way to avoid this is to limit yourself to one or two questions per section, thus forcing you to restate the main idea. If you really do have to memorize the details, flashcards with spaced repetition, is a better tool.

Step Four: Creating Clues for Future Searches

Sometimes the goal of notes isn’t to facilitate your memory, inside your brain, at all. Rather, the goal is to create an easily-searchable document that can help you find things you thought were important later.

I use this with writing all the time. I take notes, not so much to help me pay attention or memorize the facts, but to serve as anchors to find later if I’m looking for a quote, factoid or reference.

Digital note-taking systems like Evernote, make this easiest. Although, even the simple note-taking features on Kindle can work quite well. If I know I’m reading a biography and I need examples of the person doing something specific, I might highlight and tag any of those examples with a keyword so a simple search will bring up all the relevant passages.

Similarly, if you’re reading something you plan to use for a specific purpose, you can even put little sticky tags on the book to mark passages that refer to that. Say you’re reading a book on marketing, but you’re mostly interested in pulling ideas to try for your own business. You could put these tags on the book so you can easily flip through later if you need inspiration.

Final Question: Paper or Digital?

A question many students ask me is whether they should take paper or digital notes.

For classes where my goal is to study, I tend to prefer paper. There are studies supporting the use of paper versus computer note-taking, although the reasoning behind this might be that it’s harder to copy notes verbatim on paper, so you’re forced to think about the information while taking notes. Provided you aren’t taking verbatim notes, then, whichever option is the most convenient for you.

For texts where my goals is to reference later, I tend to prefer digital. Searching digital documents is much, much easier than printed ones.

The truth is, however, if you follow the above steps, you can find the right answer for your situation based on what makes you feel the most comfortable.

Quick Summary of How to Take Notes While Reading

Here’s a quick summary of what to do in order to take notes while reading:

Figure out your purpose.

Choose a technique that maximizes your focus on what is most relevant for your purpose. There’s many different ones (jotting in the margin, separate notes on paper, Question Book Method) for different purposes.

Decide whether to optimize for review or retrieval practice. For docs you don’t plan to extensively study, review is the obvious choice. For texts you need to master perfectly, the Question Book Method (for big idea) or flashcards (for details) saves time.

If you do need to go back into the text again and again, create clues in your notes that can help you find what you’re looking for faster.

Above all, however, pick a method that you feel most comfortable with. The variety of different ways to take notes exist because there are many different reasons you want to read something and remember it. Experiment with them until you find the way that works best for you!

The post How to Take Notes While Reading appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 28, 2019

How to Push Past Your Analysis Paralysis

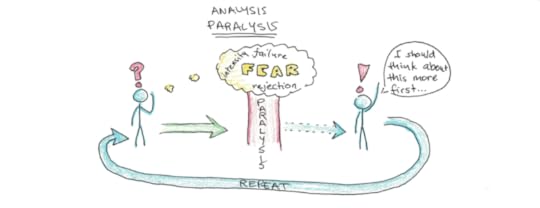

You know you should really get started but you can’t. What if you make the wrong choice? What if you start it out the wrong way, and it all gets ruined? You start to feel that weight in your stomach, that tension in your chest, as you feel a little panic about the idea of going forward.

Maybe it’s best to just hold off for a bit. Sleep on it a little more. Get some more feedback. Figure out what the “right” thing to do is. Plan it all out, until it makes sense. That tension you were feeling starts to melt away.

Analysis paralysis is a specific kind of procrastination. You feel some aversion to going forward. You convince yourself that the problem is that you haven’t given it enough thought, done enough research or really figured things out enough to get started. As you mentally shift the idea of taking action into the future, your tension subsides you delay it some more.

Analysis paralysis is also really hard to overcome because, it’s not always harmful. Sometimes you do need more research. Sometimes you shouldn’t make a decision out of haste. Sometimes holding out for the best possible option is really better than jumping out right away.

But, of course, rationalizations that work some of the time are the most seductive. If something were always a bad idea, it would be hard to use it as an excuse.

Why Do You Get Analysis Paralysis?

Why do you experience this kind of pernicious procrastination?

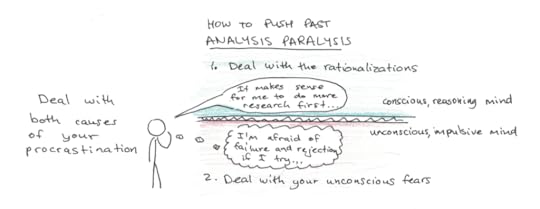

I would like to make the case that analysis paralysis actually has the same root cause as all forms of procrastination. The difference isn’t in what is causing the procrastination, but that features of the situation allow you to use a different rationalization to cope with it.

All procrastination, analysis paralysis included, is caused by the desire to avoid something unpleasant (either real or imagined). At a visceral level, you don’t want to get started, so you start searching for excuses to justify avoiding the unpleasantness.

What makes analysis paralysis different is that often there really are fears, uncertainties or doubts, which make doing more research an attractive excuse. While I usually can’t claim the need to do more research when I’m putting off going to the gym, I can do it before I start writing an article I haven’t figured out how to start, or I can put off starting a project that sounds scary, or a decision that might go wrong.

The way of dealing with analysis paralysis, has to cope with these two realities: the rationalization and the underlying fear.

First the rationalization: You need to deal with your rationalization that you need more time to think, plan and research by preventing this excuse from working.

Second the underlying fear: Even if you convince yourself that you are engaging in procrastination and your paralysis is unhelpful, that may not stop you from doing it. Now you need to turn to strategies that will push you past it.

Only by tackling both of these two aspects, can you cure your paralysis.

Overcoming Rational Excuses to Getting Started

You know you want to start a business, but what kind of business should you run? Should you be a consultant or make products? Should they be physical goods or digital ones? Should you market yourself online or person? What should you call your company? Should you raise funds?

None of these are easy decisions with an automatic right answer. Any one of them (or their combined weight) can easily become a source of analysis paralysis.

Clearly spending some time analyzing the possible options is good. However, an indefinite amount of time is going to be bad. We want to spend enough time thinking about these choices to make good ones, while avoiding the trap of endlessly repetitive analysis.

The way to get past this is to set constraints. If you set these constraints in advance, then you can undermine the rational part of your mind from using them as a justification for further procrastination. As mentioned before, this won’t necessarily stop your procrastination, but at the very least it will strip it bare so that it will be obvious that this is what you are doing.

Here are a few constraints you might try:

1. Set a decision deadline with a default.

If you’re choosing between options, pick a default (in order to not recursively procrastinate over this, you may want to pick the default choice randomly). Then, set yourself a deadline for doing all research, thinking, investigating, interviewing and anything else you might do to figure it out. When the deadline passes, you’re stuck with the default unless you changed it beforehand.

2. Start blindly, change later.

Another option is to flip the protocol. Give yourself a default, and force yourself to work on it for a certain amount of time, before you can go back to research. This works well when you want to explore options, but can’t really learn more about them without actually trying them out.

3. Leave hard choices open-ended.

Sometimes you can procrastinate about a huge thing because you can’t decide on a minor detail. You may procrastinate on studying, because you’re not sure which major to choose. However, there may be plenty of classes and topics you could study that will work for both, and so you can get started without making the decision you’re fearing.

All of these strategies work on a principle of removing the rational objection to getting started. In the first, you’ve assigned some reasonable amount of research time, so you can’t really complain that you didn’t have time to think about it. In the second, you give yourself the option to back out, so you can’t complain that the decision is too weighty to get decided yet. In the third, you get started on the stuff that would be the same for either option, so you can’t use research as a reason to procrastinate.

Unfortunately, even employing these strategies, defusing your excuses doesn’t mean you’ll get started. You may recognize that you’re procrastinating, and still do it. To overcome this too, you need to take aim at the root emotions underlying your responses.

Overcoming Emotional Resistance to Getting Started

Most emotional resistance that causes procrastination is usually something like this:

When I think about doing X, I imagine bad things happening.

I feel those bad things now, and so I move away from doing it.

When I think about not doing X now, and waiting, I feel relief, so that pattern becomes easier.

To really overcome analysis paralysis you need to escape from this cycle. You need to remove the anxiety and fear of doing the thing you’re avoiding. Second, you need to remove or invert the pleasant feeling you get from stalling.

I already spoke about the first step. Overcoming your rationalizations is important because as long as you feel justified procrastinating, there’s nothing else to do. It’s only when there’s conflict between reason and feeling that you can create some change to the latter.

How do you start to change yourself to overcome your feelings to get started?

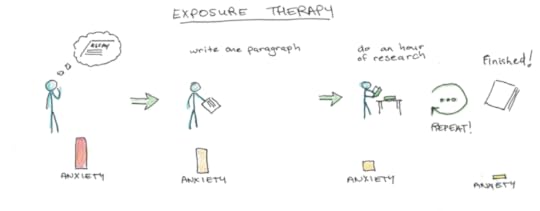

A simple answer comes from the psychology of dealing with phobias. Exposure therapy, where you give yourself small doses of the thing you’re scared of to diminish the fear it generates, works for phobias of spiders or clowns, but it can also help with getting started.

Say you need to write an essay, but you’re not sure what topic to do it on. You’ve implemented the suggestions above, and picked a default topic and a deadline. Now the deadline has passed, and you’re supposed to get started on the essay, but you’re still dragging your feet. Now what?

Here, you can start by giving yourself a task that is small enough to be manageably unpleasant. Instead of telling yourself to sit for several hours writing the essay in the library, only ask yourself to write one paragraph. After which you can take a break.

Writing one paragraph will overcome your initial resistance and make the built-up aversion to getting started slightly less. Once you’ve done this, you might try sitting for thirty minutes to write, no expectations on accomplishing anything. Later, you can keep expanding until the essay is done.

You might have dealt with a similar problem with starting a business. But what if you just had to get one client, or sell only one thing? What if you just had to make something, and not try to sell it? Breaking down your fears into atomic parts can make them something you can overcome.

Exposure therapy is just one tool. Another can be pairing taking action with a reward, so overcoming your procrastination becomes positively reinforced.

Another can also be punishing yourself for failure to act. I knew someone once who forced himself to only take showers with cold water if he missed any of his goals, the day before. The thought of cold water started to motivate action.

In all these cases, the key is that you’re resolving your procrastination not by thinking about it obsessively (which only makes it worse), but by retraining your emotional reactions to make them manageable over time.

If you can do both types of strategies—eliminating the rational excuses for analysis paralysis and reducing your emotional reactions that prevent you from doing what you know is right—you can start moving forward on even the toughest goals and projects.

The post How to Push Past Your Analysis Paralysis appeared first on Scott H Young.