Scott H. Young's Blog, page 36

June 18, 2019

The Best Articles on Productivity

How can you get more work done, overcome procrastination and do it without all the stress and guilt? Here are my best articles exploring ways to get organized and accomplish more with less effort.

The 5 Best Articles

Productivity is a major theme of the blog, as such, I’ve written hundreds of articles on the subject. If you’re not sure where to start, here are the best five to get you going:

How to Finish Your Work, One Bite at a Time – The first article introducing my weekly/daily goals system, which I’ve used for years to stay productive.

How to Be Prolific – Sometimes the key is just creating a lot. Here’s how to produce a lot more in your work.

What is Productivity Guilt, and How to Prevent it? – We all feel pressure to do more than we’re doing now. While your intentions may be good, this guilt may do more harm than help.

Make Your Time Top-Heavy – A key strategy for getting things done.

Rethinking Discipline – Some speculations on what really motivates us to stick to things.

My Books on Productivity

I’ve written two ebooks on productivity: The Little Book of Productivity and Think Outside the Cubicle.

The Little Book of Productivity is a compilation of 99 ideas to make you more productive. Perfect if you’re looking for an easy read with a high ratio of ideas to pages.

Think Outside the Cubicle, despite having a somewhat confusing title, this book isn’t about quitting your job, but about how to be productive when you don’t work in an office. Students, entrepreneurs, freelancers and a growing number of people who don’t work in the normal office environment, nonetheless need to find ways to meet those productivity challenges. This book is a guide for rethinking the way we work.

Time Management

How to Find Time – A short essay on how to find time for what matters.

Why You Need to Run a Timelog (and How to Do It)

How to Work on Your Goals When You Don’t Have Time – Strategies for sticking to your goals when time is scarce.

What’s More Productive: Counting Hours or Tasks Accomplished? – Comparing two common metrics of productivity.

Why You’re Probably Not Working as Much as You Think You Are – Timelogs are an underused, and powerful way to see where you really spend your time.

How Much Time Do You Spend on Your Most Important Goals in Life?

Schedule Footprints VS Deadline Counts: How to Hack Your Stress Levels – A guest post from Cal Newport.

Don’t Pay Yourself by the Hour – Why thinking in terms of results, not hours worked, makes more sense.

20 Tips for Batching to Save Time and Cut Stress – Batching small tasks in one go can save a lot of time and free your time up for deep work.

Energy Management

Rethinking Discipline – Some speculations on what really motivates us to stick to things.

Energy Management – My first post on the subject.

7 Tips for Morning Alertness Without the Caffeine – I got through some of my most difficult projects (including the MIT Challenge) without drinking coffee or caffeine. Here’s how you can wake up without the brown stuff.

What Does it Mean to Work Hard

Why Focusing Can Often Feel Lazy

The Stupidity of Cutting Sleep – Why your time in bed is your most useful per hour spent.

Why Focus (Not Effort) is the Key to Getting Stuff Done

How to Nap (Without Feeling Exhausted After)

Energy Management is More Important for Creative Work

Motivation, Preventing Procrastination and Staying Focused

How to Cultivate Mental Stamina – How to persist on tasks that drain you mentally.

Stress, Not Working Too Much, Causes Burnout – You feel exhausted because of the emotions you need to deal with, not the toil itself.

The Complete Guide to Increasing Your Focus – Being able to concentrate is no easy task, here’s how to get better.

The Irony of Focus: Why Doing One Thing Actually Helps You Accomplish More

Could Obsessive Research Be the Cure for Procrastination? I spend a long time researching my projects, and ironically, this time spent actually increases my ability to stick to hard things.

Why You’re Lazy (and How to Fix It)

Work Less to Get More Done

20 Tips to Survive When You’ve Overloaded Your Schedule

Systems for Getting More Done

Double Your Output (While Working Fewer Hours) – My approach to productivity.

The Art of the Finish (How to Go From Busy to Accomplished) – Popular article from Cal Newport on how to get things finished.

Too Much Work? Here’s How to Handle It

Do You Trust Your Productivity System? – Trust that your system will get the job done will keep you from stressing over it.

Boost Productivity with a To-Don’t List – Why the things you don’t do often determine your productivity more than the things you work on.

How to Speed Up Highly Creative Tasks – Applying two-flow theory to creative work.

plus, the original article describing two-flow theory.

Kill Open Loops – Relax without feeling lazy.

Twenty Ways to Stay Productive When Working From Home

More Thoughts on Productivity

How Procrastination Can Help You Succeed – Delaying isn’t always a bad thing!

20 Unique Ways to Use the 80/20 Rule Today

Don’t Be Busy – Why true productivity often looks like laziness, and why busyness often leads to less getting done.

Just Finish It

Does Enjoyment Trump Efficiency? – Why the most efficient solution may not always be the best one.

How to Juggle Pursuits and Still Get Stuff Done

The 10 Really Obvious Ways to Be More Productive

Taoism and the Art of Productivity

How to Keep Productivity from Making You Into a Robot

Build a Motivation Catalyst

10 Tips for Staying Productive While Being Scheduled to Death

Have a question related to productivity, procrastination, and getting things done that I haven’t covered here? I’m always looking for new things to write about, so ask your question in the comments and I can consider it for a future article.

The post The Best Articles on Productivity appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 17, 2019

Pre-order Ultralearning and Get Way More for Free

My new book, Ultralearning, is going to be published on August 6th.

I’ve worked like crazy on this book for the last four years. More than just researching and writing, the topic has been the focus of my life for almost a decade, through projects like the MIT Challenge, Year Without English and more.

I think you’re going to like the book. I worked hard to make the book as compelling, scientific and practical as possible. I’m very happy with the finished product, and I think you will be too.

But I Need Your Help…

The problem is that most books are ones you’ve never heard of. I didn’t realize this until I started writing, but there are a ton of books out there. Far more than can be reasonably stocked inside a typical bookstore, or can be recommended by Amazon.

Pre-orders are really important to getting enough momentum so that other people have the opportunity to find out about the book. Early sales can convince retailers to stock the book or Amazon to recommend the book to other customers, which makes it much more likely other people will find it.

Therefore, I have a simple request: If you were thinking of buying the book when it comes out, pre-order it instead.

A Ton of Free Stuff I’ll Give You in Return for Pre-ordering Ultralearning

Obviously this book matters a lot to me, but this is just my life, and I don’t blame you if you have bigger priorities than helping me out. That’s why, if you pre-order, I’m going to give you a ton of stuff you’re going to like (that happens to be worth a lot more than the price of the book).

Pre-order the book before August 6th (when the book is released) and I’ll sweeten the deal with these ten bonuses:

All of the ebooks I’ve ever written, including:

1. Learn More, Study Less.

This is my most popular book I’ve ever sold. Despite both being about learning, ultralearning and this book cover different things, so it’s a good complement rather than repetition.

2. The Little Book of Productivity.

Ninety-nine ideas to help you work smarter, better, faster and do it with less stress.

3. Think Outside the Cubicle.

How to be productive when you don’t work in an office. If you’ve wondered how I get things done from running a business to doing the MIT Challenge, this explains my system.

4. How to Change a Habit.

My first book and a complete guide to changing your habits. Comes with an audio companion guide as well.

Normally I would sell these for over $100 together, but I’m going to give them to you for free if you pre-order the book in any format and send me your receipt.

5. Ultralearning PDF Workbook.

I’ve created a companion PDF workbook to go alongside the book which can guide you through applying ultralearning to your life.

Four ultralearner interviews, where I deconstruct the learning efforts of famous experts that they haven’t shared publicly before, including:

6. James Clear

On how he became a best-selling author, award-winning photographer and the intersection between learning and habits. Those who pre-order will get access to our full conversation, I’m only going to publish a snippet publicly after the book is out.

7. Cal Newport

On how he applied the ideas in ultralearning to get to top of his class in undergrad, graduate from MIT with his PhD and become a tenured professor, all while simultaneously building a successful career as a writer and author.

8. Barbara Oakley

On how she learned Russian, overcame her difficulties with math to get a PhD in engineering and built the most popular online course of all time, Learning How to Learn.

9. Tristan de Montebello

Tristan, who is documented extensively in the book, went from near-zero experience to a finalist for the World Champion of Public Speaking in less than seven months. We discuss how you can get better at less technical skills, the ultralearning way.

10. 2-Hour Private Webinar Chat.

After the book had released, I’m going to hold a two-hour private conversation, online with me for those who pre-ordered. I’ll share some insights that didn’t make it into the book and you can ask me any questions you’d like. I’ll try to make a recording available for anyone who can’t attend live.

Best of all, if you pre-order the book, I will give you all of this stuff right away (minus the live chat, to be held after you’ve had a chance to read the book), so even if the book isn’t out for a few weeks, you’ll have plenty of stuff to keep you busy.

I’m giving away a lot more than the cost of the book because I believe this book is my best work and I want to make sure people have a chance to see it. Your pre-order will help immensely with that, so this is just a small thank you.

Click here to see the homepage for the book and get links to pre-order. If you’ve already pre-ordered your copy, just attach your receipt in a message to support@scotthyoung.zendesk.com.

Want to know more about the book first? Check out the homepage where I explain what the book is about, what’s in it and answer common questions.

The post Pre-order Ultralearning and Get Way More for Free appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 14, 2019

How To Stay Motivated To Go To The Gym Long-Term

Question: It seems that it is easier to muster up the motivation to work towards a concrete short term goal; a 30 day fitness challenge or training for a half marathon etc. But how is it so much harder to maintain motivation to go to the gym week after week for the whole year? Is it beneficial to always have a “fitness goal” in mind or can one maintain motivation for fitness without a goal?

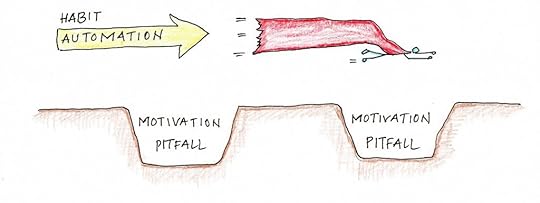

If you need to use anything beyond a minimal motivation to go to the gym on a regular basis, you don’t have a habit. That’s pretty normal, most people don’t have gym habits, or they oscillate between having a habit and falling out of the habit.

The goal of creating a gym habit is to make going to the gym such an unthinking part of your life that you don’t really consider it. It’s just something you do.

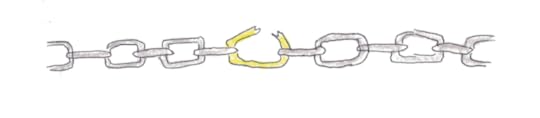

Getting to that point takes time. Part of it is strictly habituation—you need to go to the gym consistently enough for a long enough period of time in relatively the same way so that it will feel automatic. I found 30-day trials to be a good kick-off for a habit, but in truth making a habit totally automatic may take months or more. The other part is that gym habits, like most habits, are meta-stable. This means that it’s always easier to not do them than to do them, so while they can be stable for a long time, they’re also prone to collapsing if something from the outside disturbs them.

Fitness goals and other short-term projects can inspire action, but they also risk failing to habituate your habit sufficiently. You can get excited to work out for a month, but what about a year? A decade? That requires long stretches where you exercise without thinking about it much, which in turn requires a habit that’s pretty deep.

My advice when starting any goal like this is to begin with the actions and habits you want to create and only once those have been established aim for making more specific improvements. This could be a gym habit, or it could be a writing habit, language learning habit, programming habit or meditation habit. Once you figure out the kind of habit pattern you want, you can then start thinking about what kind of specific targets you want to reach or improvements you’re after.

The post How To Stay Motivated To Go To The Gym Long-Term appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 13, 2019

Do Long-Term Goals Bring Happiness?

Question: Our goals, emotions, personalities, life situation and priorities are always shifting. What we wanted 5 years ago is not necessarily what we want today. Even if a long-term goal is realized, it does not bring the same satisfaction that we once imagined it would. Isn’t it better to only set short term goals that align better with one’s current life situation? Why even bother with long term goals?

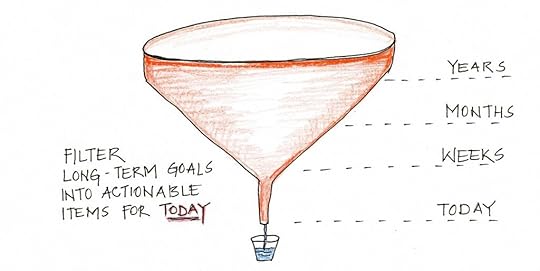

The purpose of setting a goal is to align your behavior and life in the present. I think this point is often missed in discussing goal-setting in general, because most people see setting a long-term goal as about (primarily) realizing that goal in your future.

In truth, you have no control over the future. You only have (some) control over your present moment. This isn’t to be fatalistic, it’s simply a fact that any change in the future is going to be because of some action you took right now.

So why set goals at all? The reason is that setting and having goals can modify how you behave in the present. This can either improve your quality of life immediately (it’s better to have a life of purpose and hope than boredom or despair), or it can make your future life better by achieving something that will improve your life.

This new perspective makes it easier to go back to the original question about setting long-term or short-term goals. You should take goals such that they modify your present behavior in such a way to improve your life either immediately or in the long-term. If the goal doesn’t change your present behavior, it’s useless. If the goal changes your behavior, but in ways that make you worse off in the now or in the future, it’s worse than useless.

Long-term goals, therefore, are useful if they are enough to motivate you to take action today. Often, this isn’t the case. A goal to be a millionaire in ten years isn’t worthwhile if you don’t do anything differently right now as a consequence. Shorter projects are often better here because they more directly inspire action. Being a millionaire in a decade doesn’t obviously lead to an action right now. But wanting to start a new business in six months might. Even better, a goal should come with some kind of plan so you know what you should be doing differently right now, rather than just a vague sense of wanting something distant.

In my own life, long-term goals have sometimes inspired a lot of motivation. Wanting to own my own business was a goal that took me eight years from when I had the idea to when I was actually able to live off of the income. There were a ton of shorter goals, plans and daily to-do items along the way, but those were intermediate motivators for a bigger dream of being self-employed.

These days, I tend to focus a lot more on projects of 1-2 years. These projects often inspire me more directly, or they push my life in directions I want to go. I don’t find I need as many specific long-term goals these days because there are few that inspire action greater than those shorter ones. However, that’s just a consequence of my life situation rather than anything specific about goal-setting.

My advice to readers thinking about their goals is to evaluate them on whether they cause you to act or feel differently right now. If they don’t, then you need to either rework them so that they do (rephrasing them in terms of habits, tasks and milestones) or you need to pick new goals. Whether they are long or short will depend on your situation and what things inspire you enough to work at them.

The post Do Long-Term Goals Bring Happiness? appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 12, 2019

The Perpetual Backburner: Is Procrastination Part Of Human Nature?

Question: It seems it is human nature to put off any task that is not urgent, and at any given moment, we might be procrastinating on over a dozen things that we “should” do but are not. Even when we say we are ‘prioritizing’, we are still perpetually delaying some tasks. Given our energy is limited, is it humanly possible to completely beat procrastination? If not, how does one come to terms with it?

I don’t know of a single person who never procrastinates. There are some people who never procrastinate on certain things (e.g. they never miss the gym, they always wake up right away or they’re quick to get to work) but even the most productive people procrastinate on certain things.

The basic logic behind procrastination is that you’ll delay working on something if the aversion to working on it (or the pull to distract yourself) is greater than your motivation to work on that thing. This is why a lot of us get chores done at the last possible moment. It’s only when the consequences of not meeting the deadline are so strong that you’re motivated enough to start doing an unpleasant task.

This basic pattern doesn’t go away, so procrastination will always be with you. However, the flip side of that, is that once you recognize the pattern you can take steps to reduce the impact of procrastination. It won’t mean you’ll never procrastinate, but it will give you a path for handling procrastination when you do.

If taking action happens only when motivation > aversion, then there’s two ways you can combat procrastination:

1. Increase motivation.

Deadlines are one way to do this. Setting difficult goals that will only be met if you stay on schedule is another way you can motivate yourself. Sometimes even just thinking about your goal or the outcome you’re after can push you forward and create motivation. When I’m working on big projects that have a lot of difficult work, I like to try to set challenging goals, and then break them down into smaller and smaller increments until there’s always something I need to do right now to complete on time.

The problem with just increasing motivation is that it’s sometimes fragile. If you turn up the pressure too much, you may crack, as can happen when you miss one deadline so the pressure to meet future deadlines starts decreasing

2. Decreasing aversion

If you can make the task you’re facing more pleasant, you’ll be less likely to procrastinate. The Pomodoro Technique is a classic tool here. While contemplating working on an essay, math problem or difficult project can be enough to make you procrastinate, working for twenty minutes only is a lot more pleasant. There’s lots of ways you can make tasks more pleasant, even if that’s mostly in focusing on a small, less threatening component of the total thing you want to work on.

The post The Perpetual Backburner: Is Procrastination Part Of Human Nature? appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 11, 2019

You Have to Be Willing to Get Cut

“I only want to teach people who are going to stab someone or get stabbed.”

Whiskey in one hand, my friend was only half-joking. He teaches martial arts, including knife fighting. He was mocking the fact that students come to him, including police officers and members of the military who need the skills for their work, although few are willing to get cut.

You may not want to learn knife fighting, but the fear of getting cut is real in much more mundane pursuits:

You want to learn a language, but you don’t want to make mistakes speaking.

You want to give speeches, but you don’t want to bomb your presentation.

You want to write a novel, but you don’t want anyone to laugh at your work.

You want to be a surgeon, but you don’t want anyone to die on the operating table.

Nobody wants to get cut. Failure, injury, pain, rejection, and death, are all things we instinctively avoid.

At the same time, the risks can never be eliminated. For many skills, the only way to learn them is to endure a long run of painful mistakes. Even for those where the price of mistakes can be deadly, there’s always a residual risk you must be willing to accept.

The Fear of Getting Cut

Of course, the most learning mistakes don’t result in getting stabbed. You get booed on stage. Critics thrash your latest work. Native speakers interrupt you and switch back to English.

The fear can be as acute as mortal danger, but the actual risks are small. In those cases, it’s better to just get cut a lot. Start by getting rejected. Start by failing utterly. Start with the worst blows so that they lose their sting.

Two things happen when you decide to get cut. First, you get cut a lot less than you expected to. The world isn’t really so mean as your imagination. Second, when you do feel it, it’s not as deep as you anticipated.

Minor scrapes aside, you can stop being timid and start getting good at what you’re afraid of. The fear itself was more unpleasant than the actual experience, so it is, ironically, by being willing to get cut that you endure the least pain overall.

When Cuts are Deadly

Of course, not all wounds are minor. Get stabbed regularly and learning stops pretty quickly. Doctors, pilots, engineers and those who hold life in their hands can’t be so frivolous as to ignore the risks.

Yet, even here, accepting the risks is essential to be able to move forward. I once met someone who worked in medical technologies who told me that, “Every choice you make, you have to accept that people are going to die.” This may sound callous, but from his position it was simply a fact. A life-saving treatment fails to work, people die. Don’t try the life-saving treatment, people die.

Cuts are minimized through training, simulation and practice. But they’re never eliminated. Being willing to get cut is the only way to more forward psychologically.

What Cuts are You Afraid Of?

What are the cuts of your work and life you’re avoiding that need to be accepted? The anxieties that keep you from attacking the problems in your life? What minor cuts could you feel now, so you don’t spend your life flinching or face worse wounds later on?

The post You Have to Be Willing to Get Cut appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 10, 2019

The Best Articles on Goal-Setting

How can you hit a target you don’t even have? Goal-setting, the process of taking your vague dreams and ambitions, and turning them into concrete targets and plans of action is powerful. Here’s some of my best articles, divided into subtopics.

The 5 Best Articles

I’ve written hundreds of articles which touch on goal-setting. If you’re not sure where to start, here are the best five:

Set Goals in the Middle – Why, for some pursuits, it’s actually better to wait before picking your target.

Two Types of Growth – We tend to see progress as a straight line. In practice, diminishing and accelerating returns are more common. Here’s how to spot them and how it should alter your approach to your goals and projects.

Show Up, Every Day. Why consistency is the foundation for any long-term success.

Why It’s So Hard to Stick to Your Goals (And How to Make it Easy) – I introduce the action-intention gap, and how to close it.

On Keeping Your Word – We all instinctively avoid breaking promises to others. But what about the promises we make to ourselves?

Make it Happen!

In addition to my articles on goal-setting, I teach a course on how to create goals and systems to take the aspirations you have and make them happen in your life. If you’ve ever felt like the gap between what you intend to do and what actually happens is large, this is the course to close the gulf.

Join the waiting list to find out about new sessions.

How to Set and Achieve Your Goals

How to Push Past Your Analysis Paralysis – How do you pull the trigger and just get started on those goals you’ve been avoiding?

How to Make Hard Life Decisions

The Simple Algorithm for Making Big Life Decisions

The Overkill Approach: How to Solve the Hardest Problems You Face

The Most Important Skill You Can Learn – Why goal-setting matters.

Should You Set Deadlines for Your Goals?

What Should Your Goals Be?

How I Choose Projects

Make Plans Work on 20% Effort

How to Execute a Successful Side Project

If You Want to Be Fit Don’t Buy New Running Shoes

How to Achieve a Goal (If You Don’t Know Where to Start)

Why I Stopped Setting Long-Term Goals – I rarely set goals with extremely long time horizons, preferring projects of a year or two. Here’s why.

Be Ambitious with Goals, Not Deadlines

How to Start Projects You’ll Actually Finish

How to Find Motivation, Commit Yourself and Do the Work

You Fail to Reach Your Goals Because You Design them Badly – Motivation doesn’t come from nothing, it’s built into how you design your projects.

Impossible Standards: The 3-Step Process to Reach New Heights in Your Work and Life

How to Work on Your Goals When You Don’t Have Time – Strategies for sticking to your goals when time is scarce.

How to Commit to Long-Term Goals

How to Commit to the Things You Start

You Probably Have Too Much Motivation – Why too much motivation may actually harm your efforts.

Are Successful People Just Putting in More Effort?

How to Build the Habit of Finishing What You Start

Is Obsession a Prerequisite for Success?

How to Kick Yourself Out of a Slump

How to Stay Motivated on Long Projects

More Thoughts on Goal-Setting

How to Know When to Give Up – Implicit in any effort to finish something is an idea about when you should quit. Better to think about this clearly, than to do it automatically when times get tough.

Is Ambition a Good Thing? Thoughts on Striving Without Selfishness

Hustle or Mediocrity? Ambitious striving is just one possible approach, here I discuss the trade-offs.

Success is Boring – Goal-setting and achievement are enticing, but the reality is usually more mundane. Learn to love boring successes.

What is Self-Improvement – What does it really mean to try to improve yourself? How does this differ from trying to improve the external things in your life?

How Important is Growth – Does every goal need to be an improvement? Sometimes staying put may actually be best.

What’s Your Life Strategy? – Thinking beyond specific goals, what is your strategy for life itself?

What’s Next? – What to do after you finish your goals.

Why You Should Be More Extreme – Our society stigmatizes obsessive effort, but it’s often the key to success.

You Should Have More Spectacular Failures – Don’t optimize for a perfect track-record.

Failures of Intensity – Often the problem isn’t knowing what to do, but how much you need to do it to reach success.

The Formula to Help You Decide Whether to Strive or Settle

Should You Accept Your Constraints or Try to Improve Them?

Should You Do Intense Short-Term Projects or Build Long-Term Habits?

Bold Moves are Often Easier than Small Ones – Why doing something big is often more successful than trying something small.

Catch-22s and Bootstrapping Your Life – Getting started is often a paradox, how can you break out of it?

Self-Discipline Comes First

Don’t Know What You Want?

Feeling Lost? Stop Worrying About Your Life Purpose

You Can’t Set Goals to Fix Your Flaws – Speculations on why many attempts to improve fail–because they’re driven by the wrong motivation.

Why Goal Setting Can Leave You Miserable (and how to avoid it)

Should You Wander the World or Build a Home?

How to Set Goals (Without Being Obnoxious) – Being an avid self-improvement enthusiast can make your life better, but it can also breed an annoying personality. Here’s how to avoid that.

How Much Time Do You Spend on Your Most Important Goals in Life?

The post The Best Articles on Goal-Setting appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 7, 2019

What Medieval People Got Right About Learning

We tend to assume that if people today and people five hundred years ago do things differently, it’s because we’ve figured out a better way to do it. After all, we have microscopes, democracy and penicillin. People in the middle ages lit cats on fire for fun.

Yet despite overwhelming progress, it’s ironically in the area of education that we may be the ones who have it backward.

Apprenticeships were, for a long time, the dominant way of learning professional skills. A master agrees to show you how to perform a useful skill. In exchange, he got a bunch of free labor from you while you were learning.

Why Apprenticeships Beat Classrooms

There’s a few good reasons to prefer the apprenticeship model to classes.

1. Transfer is Hard.

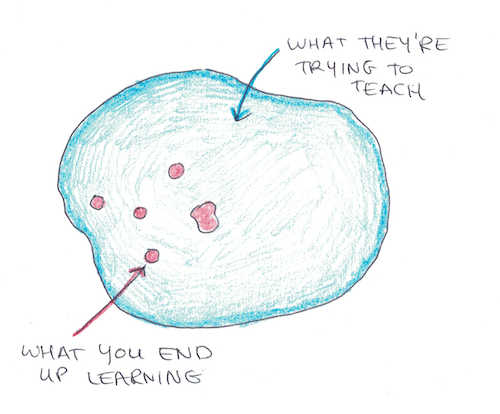

The first has to do with transfer. It’s been well-known for decades that learning general abstractions is very hard. Instead, what we learn tends to be hyperspecific. It’s only after learning many hyperspecific things that we get the ability to apply it to completely novel problems.

Consider the findings that economics students tend not to perform better on problems which require economic reasoning, that taking a high-school psychology class doesn’t improve performance in a later psychology class in college, or even more startlingly, that a significant fraction of American high-school graduates can’t calculate the cost of ordering office supplies, given a list.[1][2]

These educational failures are an embarrassment. But they more likely reflect the simple fact about transfer: if you’ve only ever done math, psychology or economics problems in a very narrow setting, you’re unlikely to apply them in the real world, even if you could in principle.

Classes are divorced from the practical applications of learning. Apprenticeships train in exactly the situation you’d want to apply the skill.

2. Learn by Doing (and Watching).

The second reason to prefer apprenticeships is that they more easily mimic how human beings learn almost every other skill we need to survive: by doing and watching.

The doing aspect is obvious, and related to the problem of transfer I described above. The watching aspect is more interesting. Human beings, it appears, are nearly unique in the animal world for being able to learn something by watching somebody else do it.

Joseph Henrich, in his excellent book, The Secret of Our Success, argues that this social learning, not raw intelligence, is what truly separates us from non-human primates or other intelligent animals.

Interestingly, it’s often not so important to actually understand the reasons behind why you should do something as it is to see it being performed correctly. In one interesting study, participants learned through iteration to improve a type of rolling machine, but they couldn’t give an accurate theory why their design worked.

Classrooms don’t follow this principle. Instead, they try to teach broad theories (the why) to eventually make it into the how. Consider medical students, who spend years in the classroom learning theories of chemistry and biology before studying medicine for another few years before working with patients.

Apprenticeships, which focus on practice first, allow you to learn how you were designed to learn. By doing and watching other people.

3. Most Theories are Wrong Anyways.

A lot of people reason on a pyramid model of knowledge. This says all knowledge is built on top of more fundamental layers, with the foundation needing to be bigger than the layer above it or it will collapse. Biology is grounded on chemistry, which is grounded on physics, grounded on math. Our knowledge of physics can’t exceed our knowledge of math.

Except, this model doesn’t work at all. Knowledge isn’t a pyramid. In general, we’re almost always learning from the “middle” of something, with both more complicated theories and more fundamental theories being less well-understood than the central phenomena we started with.

A clear example of this is science itself. We have tons of scientific knowledge. The pyramid approach would say that this must mean we have an ironclad theory of how scientific knowledge is produced. Except we don’t. We have some theories of science, but they’re a lot shakier and contentious than the actual science we created.

Classroom learning tends to be based on the pyramid model. Instead of working directly with a practical example, it argues that we should start by teaching a more abstract theory from which all practical examples can be derived. Learn the rules of conjugation before sentences. Learn Newton’s laws before trying to guess at some practical results of physics. Learn computational theory before coding.

Not all classes are this extreme, but the pyramid model still has a dominant influence in academic learning. Apprenticeships, in contrast, often ignore theory altogether. Which is good, because the theories often aren’t as accurate as the practical knowledge anyways.

How to Create Your Own Apprenticeship

It’s unfortunate that true apprenticeships have gone out of fashion in many fields which could benefit from them. However, if you understand how apprenticeships work, you can try to inject more of the same principles into your own learning.

1. Start by Learning Concrete Things for a Specific Purpose.

The first step is to begin your learning with a specific purpose in mind. Many people think that if they restrict their initial purpose too much, they won’t ever learn fully general skills. In truth, the opposite is closer to the truth. By really learning for a specific purpose, you paradoxically acquire skills that generalize better than if you had started trying to learn everything from first principles.

Examples:

Learn to code by picking a particular piece of software or script you want to make.

Learn a language by figuring out exactly where you want to use it (i.e. while traveling in Spain? Watching movies in Japanese? Reading literature in French?)

Learn history by deciding to write an essay on the military strategies of ancient Rome, rather than by abstractly trying to learn a bunch of history.

2. Theory Builds on Practice, Not the Other Way Around.

Theory is important to learn, but it is more useful after the foundation of practical knowledge has been built. Computational theories after writing code. Grammar after mastering basic sentence patterns. Music theory after learning to play a bunch of songs with your guitar.

The flipside is, theory is actually a lot of fun once you have some foundation in practice. I did the MIT Challenge without having taken more than a couple programming classes in college. But I had spent my high-school days tinkering with little games and applications. For me, the theory-based classes at MIT were perfect, but they might have been a waste of time if I had never tried to make anything before.

3. Immerse Yourself in an Expert Practice Ecosystem.

Immersion in an ecosystem of expert practitioners is one of the best moves you can make for accelerating your learning. Unfortunately, this is often one of the hardest steps to take because these environments are often gated, difficult to access or invisible to the outside.

Ironically, for all my jabs at classroom learning, academia in the graduate levels and beyond is actually this kind of ecosystem! Professors (masters) take in grad students (apprentices) and get them to work for very little money so that they can learn to produce research.

The easiest way to do this is to join an existing practice ecosystem. That could be at a school (research at Harvard), company (machine learning at Google), place (French in France) or even a community (speedrunning through online forums).

If you can’t find it, then you can also make one. When I went to write my first book, I had already made so many friends with other authors that I knew how many processes worked, despite never having published a book myself. The same is true with entrepreneurship. Whenever I have a challenge in my business, I usually know of a few people who are better than I am, and can offer advice.

Learning by doing and learning by watching sound obvious, but they’re often obscured in our classroom-focused style of education. We might not bring back apprenticeships, but by bringing back the features that work, we can all hopefully learn a bit better.

[[] – Caplan, Bryan. The case against education: Why the education system is a waste of time and money. Princeton University Press, 2018.

The post What Medieval People Got Right About Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 6, 2019

Why Copying Successful People Can Backfire

James Clear recently tweeted about the importance of carefully cultivating your tribe:

He’s not wrong. Being surrounded by the wrong culture can definitely impede your progress.

However, there’s more nuance to the idea than that you’re simply the average of the five people you spend the most time with.

In one of my favorite books of all time, Harvard anthropologist Joseph Henrich, makes a compelling case that it’s not true that people merely copy the behavior of those around them. Even more, the fact that we don’t follow this simple approach may underlie the source of all human progress.

Who to Copy: Prestige and Dominance

Many animals exhibit what’s known as a dominance hierarchy. The alpha picks on the beta, all of whom pick on the omega. These hierarchies are asserted through force and they exist in human beings as much as they do in others. Bosses, commanders and kings all formalize the notion of a dominant individual being higher up in status.

Interestingly, however, human beings have a second, separate status hierarchy that doesn’t seem to exist in other animals: prestige hierarchies. A prestige hierarchy isn’t maintained through force and alliances, but through respect. Artists, academics, celebrities and intellectuals are higher up on prestige hierarchies.

When anthropologists study human beings across different cultures, what they observe is not blind copying of random individuals that surround them. Instead, it’s copying of prestigious individuals.

This copying also seems to be happening at a level beneath explicit rationales about what works. This means that people will copy things even with no argument about why X is better than what they were doing before, but simply because someone prestigious seemed to be doing it.

One example, involving hunter gatherer tribes, found that after a more successful tribe (= more prestigious) had painful rites of passage for boys to be seen as men in the tribe, many other tribes spontaneously adopted the same kinds of rituals. This kind of copying, therefore seems hardwired instinctually, rather than simply a product of reasoning about the cause of success.

We try to do what the cool kids do, without even realizing it.

The Power of Prestigious Copying

Henrich argues extensively in his book that this simple mechanism: copy prestigious people (or groups) may have been one of the principle mechanisms behind the invention of culture and how human beings surpassed our hominid ancestors.

Prestigious copying works like natural selection, except instead of inheriting genes through reproduction, you copy behaviors from other individuals. Since people tend to copy all the details, not merely the underlying rationale, this fidelity means that complex behaviors can evolve culturally and propagate even if people don’t know why they work.

It’s likely true, therefore, that our cultures have embedded in them countless beneficial strategies and behaviors that we don’t have a clear reason for why they work. They work the same way that a cat can hunt without understanding its own digestion, because a process of replication and selection generated it, rather than deliberate engineering.

When Copying the Most Successful Backfires

For all the power of copying, however, it can backfire. Like the painful manhood rituals of the tribesmen, just because successful people are doing something doesn’t mean it’s actually useful.

In fact, the opposite can be true. Successful people often engage in what’s known as counter-signaling. This is when you do things that are actually costly, just to show you have the ability to pay for them.

A gazelle that wastes energy by leaping straight up in the air after spotting a crouching leopard could have used those calories for running away. Instead, however, it wants to say “look, I’m so fit you shouldn’t even try to chase me.” The peacock has such impressive plumage, not because it helps him survive, but because he has to be healthy to survive, so the peahens will pick him.

Signaling is pervasive everywhere, thus our instincts to blindly copy prestigious individuals can backfire if we copy costly signals we can’t actually afford. The strategy to copy prestigious individuals only needs to be right on average to have survived this long. Which means it can still be wrong in plenty of specific cases.

Does Prestige + Signaling Explain Ineffective Institutions?

I suspect that this combination of signaling + prestigious copying explains the unusual persistence of many of the broken features of our modern institutions. Heathcare, education, politics, religion and more often have obvious flaws where there are clear fixes available. Yet, they don’t get changed because their signaling functions often override their actual usefulness.

Put in other words, schools often don’t fully reform because the reforms that would make them better for learning make them worse at giving credentials. Hospitals focus on expensive interventions rather than cheap preventions because showing you care matters more than promoting overall health. Politics centers around drama instead of policy because drama allows you to show people which team you’re on better than abstract policy discussions.

The lesson of signaling is that when the big things in the world around you look broken, it’s often because you don’t understand the function they’re really trying to serve.

In a normal environment, competition might eliminate these inefficiencies. A competing institution, that is better formatted to how people actually learn, might defeat reigning universities in an open contest.

Except that because we copy prestigious individuals, institutions that gain prestige themselves may persist much longer than they should. Universities, healthcare systems or even modes of governance can become sclerotic but survive because their accumulated prestige means that people emulate them unconsciously and thus they can maintain their monopoly.

When Should You Avoid Emulating Successful People?

As a practical matter, the prestigious copying works well. If it didn’t, you probably wouldn’t be reading this now. In fact, you probably wouldn’t be reading anything, instead just eating some raw meat from an animal you had to kill with your bare hands.

However, with the existence of signaling, it can also backfire when you copy countersignals which hurt your success, but which successful people do to show that they can.

Deciding which are countersignals and which are the genuine causes of success isn’t easy. After all, if fully understanding the reason behind a successful behavior were easy, we would have evolved that, instead of blind copying. We haven’t because often saying what makes something work is a lot harder to say than simply noticing that it does work.

There are cases, I think, that are obvious enough that they probably are worth avoiding (or at least being skeptical of) despite the fact that successful people do them. Some examples:

Wasteful spending of money and time. I think most people will accept that owning a Ferrari doesn’t make you rich. But how many of us fetishize the weird investment habits of people who have unlimited money to waste?

Excessive pickiness and avoiding grubby work. Some successful people boast about turning down opportunities or avoid doing some work that’s hard, but probably necessary when you’re just getting started (like pitching your work instead of just passively receiving opportunities). Some of this is simply a consequence of a different life situation, but I suspect some of it also functions to say, “I’m important enough that I don’t need to do X anymore.”

Weird rituals that are probably useless. Any success advice you read that starts with what person X has for breakfast in the morning is probably bogus. Similarly, I think it’s no surprise that weird health trends like anti-vax, detox crazes and strange supplements are mostly applied by those who are already healthy and rich. They have the money and body to tolerate those treatments.

Another good way to spot for signaling is to notice when people say X a lot more than they actually do X. If the proportion of saying-to-doing is high, X is probably more of a signal than an actually useful task. In contrast, if the ratio is the opposite: most people do it, few admit it, then it’s a kind of anti-signal, something that is very effective despite the fact that people don’t want to admit to doing it.

Although I think there’s probably benefits to applying some skepticism when copying prestigious people’s personal habits, the mysteriousness of why many culturally adapted traits actually work should also oppose going to the opposite extreme: dismissing everything unless you know exactly why it works.

The best answers are usually somewhere in-between. A mixture of wide-eyed (as opposed to blind) copying, and careful analysis to try to tease out the places where people’s words and deeds conflict to see what really matters.

The post Why Copying Successful People Can Backfire appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 5, 2019

What’s the Best Way to Make a Habit? Comparing Seven Different Approaches

The basic process for building all habits is basically the same: you repeatedly condition the behavior you want, over time, until it becomes automatic.

There’s two main ways you can condition a habit. One is through classical conditioning. This is simply a paired association with a trigger and a behavior. Going to the gym after you wake up each morning is this kind of habit.

The second way you can condition a habit is through operant conditioning. Here, you not only associate a trigger with a behavior, but you reward that pairing. Reinforcement (by adding rewards or removing pains) can accelerate the habit-forming process. At the gym I go to, there’s a pool and hot tub, so a quick soak post-workout made the overall experience of going to the gym more pleasurable, and thus easier to keep as a habit.

In addition to the different conditioning strategies (classical and operant) there’s also a ton of little things you can do to smooth the process to habit formation. James Clear’s excellent book, Atomic Habits, is a good guide to many of these.

In this article, however, I’d like to look at a different aspect of forming habits, namely the mental rules or commitments you use when trying to form them.

Seven Different Rules for Making Habits

No habit starts out automatic. Instead, there’s a deliberate period, where you must consciously apply yourself to make a certain behavior your default.

During that time, there’s a bunch of different ways you can regulate your commitment. These are things like, “Do X every day” or “Whenever X happens, I do Y.” I’ve tried a ton of these different rules personally, so I’d like to talk about what I think are their varying strengths and weaknesses so you can pick the approach that works best for you.

1. The 30-Day Trial.

This was the first approach I ever encountered to forming habits. I learned it from Steve Pavlina, although the technique predates him in various guises (21-day trials, 10-day trials, etc.)

The basic approach is simple: you commit to some change for thirty days straight. This could be something you actually do every day, like going to the gym, or another rule you follow like not drinking alcohol.

Once the thirty days are done, the concept goes, you’re free to go back to your old ways. The point of this framing is that the thirty days should be seen as an experiment. You can challenge yourself to something you might otherwise be afraid of setting as a lifelong commitment. The reverse of this is that having spent thirty days applying a new behavior is often enough to convince you to stick with it.

Pros:

Can handle more significant/difficult behavior changes you might be unlikely to start with a perpetual commitment.

Fosters an experimental mindset. “What if?” rather than assuming you already know what’s best. – One month is short enough that planning is rarely a big issue.

Cons:

30 days probably isn’t enough to actually make something a habit, especially if the behavior change is difficult.

Without a long-term plan, many 30-day trials will revert back to the original behavior. A month without drinking often ends with a few beers, not a commitment to lifelong sobriety.

2. Don’t Break the Chain.

“Don’t break the chain” is a slogan (often attributed to comedian Jerry Seinfeld) for sticking to any important behavior. The idea here is that you want to keep track of how many days in a row you’ve successfully followed your habit. As your chain gets longer and longer, you become increasingly committed to the habit.

I’ve applied this myself to many habits from daily push-ups to flossing. I do find it works really well for maintaining a commitment over a long time. I currently use the app Done, to track my DBTC habits.

Pros:

Maintains habits over a longer timeframe than a 30-day trial.

Better for things you already do (or are easy to do) but you’re not as consistent as you’d like. (30DTs are often better for more dramatic changes to your behavior)

The longer your chain, the more serious your commitment. I can remember doing pushups when I was feeling quite ill, just because I had a few hundred links in my chain and I really didn’t want to break it. That’s a powerful commitment device.

Cons:

Accidental slip-ups or situations where your habit becomes impossible can collapse your motivation.

More awkward with difficult habits. If it isn’t easy to do every day, you’ll slip up enough that your chain will rarely get long enough where your commitment is strong.

Many habits don’t work on an easy daily or weekly interval.

3. Never Miss Twice.

James Clear, who I mentioned wrote a great book on habits, has a strategy for working out where he aims to not miss a workout twice in a row. This is different from the DBTC approach where a single slip-up can undermine the entire habit.

For this, the goal is to do it every day (if possible) but if you miss a day, you must do the habit the following day.

Pros:

More forgiving than DBTC, which means it’s easier to keep up for longer stretches with harder habits.

Since you’re keeping track of misses, rather than completes, it’s a little easier to handle on an irregular schedule (say working out 4x per week).

Cons:

More slack also means more slacking off. DBTC works so well also because it’s so rigid. You’ll be much more likely to take days off unnecessarily if you know it’s only two-in-a-row that count.

Habituation works best when the trigger-behavior link is total. If you sometimes do X, and sometimes don’t, it will take longer to make the association automatic. DBTC will do this, but allowing yourself gaps might not.

4. Pretraining.

Pretraining means practicing the habit a bunch of times in an artificial situation so that it occurs more automatically in real life.

I’ve used this before when trying to condition myself to wake up automatically from the alarm, and not hit the snooze. I practiced by taking a short nap in a darkened room, setting the alarm for 5 minutes and then, when it sounded, getting up right away. Repeat this 10-20 times, especially over a few sessions, and you’ll be more likely to override your unconscious urge to fall back asleep in the morning.

Pretraining is somewhat uncommon as a tool for typical habits, but it is extremely common when the trigger is some kind of question and the behavior involves a skill or knowledge. In those specific cases, though, we tend to call pretraining “studying” and habituation is called “learning.”

Pros:

Useful for situations where you think you won’t be able to consciously control your reaction in the real situation without practice.

Aids when the behavior you want to perform requires skill or knowledge you might not possess without practice.

Cons:

Real and practice situations often differ in important ways, so the practice may not fully transfer to the real situation.

Practicing multiple times in the same session (massed practice) is known to have a weaker impact on long-term changes to your behavior than spreading them out. Since spreading the behavior out is guaranteed in more typical habit-creating strategies, this is a potential drawback of pretraining.

5. Project-Driven Habits.

Another approach is to ignore the process of creating habits altogether and simply focus on a project that will force them to occur.

I changed a ton of habits during the MIT Challenge. I changed even more during the Year Without English, when my friend and I had to stop using English to communicate. However, the habit changes weren’t explicit. Instead, they were the byproduct of trying to accomplish something else.

I find a similar thing often happens with ultralearning projects. You might learn something intensely, but not call it a “learning project” because what you’re really trying to do is start a business, create a website or prepare for a new job. Habits, like learning, are always in the background, but it’s a choice about whether to work on them explicitly or implicitly.

Pros:

You can often change multiple habits at the same time with less overhead. Normally, the goal of waking up early, making your lunches ahead of time, getting into deep work right away at your job and cold-calling people to network would be difficult to coordinate as separate projects happening simultaneously. However, if you are starting a new business, those habits might piggyback and come automatically, just by having sufficient motivation for the main goal.

A lot of habits are superfluous and don’t drive results. Focusing on projects first can help you be flexible about adopting and dropping habits based on what works, rather than assuming you already know.

Cons:

Once the project is done, the habits may go with them.

A project can often eat up or push out other good habits. Getting really excited about a work project may interfere with a healthy eating habit if you run out of time to cook for yourself.

6. Tattletale Tactics.

This strategy works by deputizing others to enforce your habit for you. The classic example is the realtor who bought a billboard with his face on it saying, “If you catch me smoking, I’ll pay you $20,000.”

The stakes don’t need to be so big, or even involve money, to work, however. If you have an annoying habit of interrupting people when they talk, you might ask your friends to point it out to you next time you do it, thus creating social pressure to stop.

This strategy can also work for positive habits, not just breaking bad ones. You might have a gym partner and go in with the deal that if either of you skip a day, you have to buy the other person dinner.

Pros:

No formal rules or mechanisms are required, just the social pressure from the outside.

If you find yourself constantly breaking your own commitments, you may not have the track-record to take your own commitments seriously. This may be the only tool you can use to effectively control your behavior.

Cons:

Requires others to care. Most people won’t care about your behavior as much as you should, so this can backfire if the incentive to tattle is weak.

Doesn’t work if others aren’t watching you while you perform the habit. How can your friends know whether you clean your house regularly if they don’t live with you? Or floss your teeth?

7. Identity-Driven Habit Changes.

Another strategy is to avoid thinking about changing a habit, but instead think about changing your self-conception. In other words, you don’t quit smoking directly, but you stop because you’re a healthy person now and you don’t put toxins into your body.

This strategy is not mutually exclusive with the ones above, but it can be a standalone approach to habit change by constantly reaffirming a new way of describing yourself and the emotions you attach to certain things.

My own experience is that this can work, but it usually works because a certain identity change was already occurring on the inside for awhile before manifesting into new behaviors. When I first became vegetarian (I’m now mostly pescetarian), I had read a ton of books about it, and it changed my feelings about eating meat sufficiently that by the time I stopped, there wasn’t much tempting about it.

Similarly, if you view yourself now as an entrepreneur, not an employee, that may change a bunch of habits automatically long before you actually quit your job. I’ve also seen many new parents make a similar transition when they turn themselves into self-professed saints overnight for the good of their children. Although such transformations can be annoying if they don’t come with self-awareness, they do often work.

Pros:

Identities, like projects, are packages of habits, so you can often change a bunch in one deliberate effort rather than piecemeal. “I’m a healthy person now,” can trigger eating better, exercising more and quitting smoking and drinking all at once.

If successful, these can make not following the habit unthinkable. A complete identity change may make the old behavior so unpallateable that you’re unlikely to ever go back.

Cons:

Often requires that your self-conception has been changing for years, and that you’ve built up a healthy dislike of your old behavior that simply hasn’t manifested yet. If you’re trying to change your identity but you still really like the old you, the change won’t last.

Hard to plan for and pull off. While identity-changing can be triggered, in certain conditions, I’m skeptical that it can be initiated purely on its own.

What Approach Do You Take to Changing Your Habits?

I’ve listed seven of the approaches I’ve used. What are yours? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

The post What’s the Best Way to Make a Habit? Comparing Seven Different Approaches appeared first on Scott H Young.