Scott H. Young's Blog, page 31

December 30, 2019

My Best Writing of 2019

I shared a lot of ideas this year. I published a Wall Street Journal bestselling book. I recorded 100+ podcast episodes. I also wrote 116 new articles to this blog.

Here are some of my most popular essays from last year:

The Complete Guides

I worked on three in-depth, research-based guides with Jakub Jilek, who is doing his PhD in cognitive science. These were some of the most popular essays this year, at over 10,000 words each, they’re more like small books than blog articles:

The Complete Guide to Memory – Understanding how you remember and forget, with practical tips on how to study and learn better.

The Complete Guide to Working Memory – How to think smarter and better, by managing your attention and cognitive resources.

The Complete Guide to Self-Control – How can you be more disciplined? What does research say about willpower and effort?

The Best Essays

Here are my favorite essays that I wrote last year:

Ultralearning Environments: Why Where You Learn Determines How Much You Learn – Why, decades after the peak of its popularity, are we just now getting much better at Tetris? The answer to this has striking implications about innovation, learning and mastery.

Unraveling the Enigma of Reason – A summary of one of the most profound ideas I’ve ever read. Our faculties of reason may not be doing what we think they are.

Stupid Advice: “You’ll Never Be Rich Working for Someone Else” – Contrary to internet wisdom, I argue that its wrong to assume entrepreneurs are better off than employees.

How to Stop Feeling Like an Imposter – Why do the most successful people often feel like failures? How can you be comfortable with yourself rather than undermining your own achievements?

What Medieval People Got Right About Learning – Classrooms may not be the best way to learn. Here’s how to think about learning instead.

Can Life Have Too Much Meaning? – We tend to think of purpose and meaning as being good things. But what if it’s possible to have too much meaning? Implications for anxiety, ambition and happiness.

How Should I Get Better at Writing? – Getting better at a skill you’ve worked on full-time for decades isn’t easy. Here I list some different *possible* paths forward. Useful thinking in case you’re wondering how to get better at your own work.

The Neuroscience of Anxiety – Summary of NYU neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux’s fascinating (if challenging) book, Anxious. Not only interesting for worrying less, but understanding how our minds operate.

Most Books Won’t Change Your Life (But You Should Read Them Anyways) – Applying some simple economic reasoning, it’s clear that most people should read more books than they do already.

Why is Taking Action Hard? – A recent foray into a question I find fascinating–why do we struggle so much with taking action? Why do we procrastinate, abandon goals and projects, fail to take easy steps to make our lives better?

Of course, with over 100 more articles I haven’t mentioned published just this year, there’s plenty more to read (or listen to, on our podcast) in case you’re interested. My archive page is organized to help you find something you might like.

Thanks for reading in 2019. I look forward to a new year of writing. As always, I’ll share what I find with you.

The post My Best Writing of 2019 appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 23, 2019

Seven Easy Habits to Read More Books Next Year

As a new year approaches, it’s a good time to think about what new habits you’d like to make. An obvious one is to read more books.

Reading is a habit of compounding growth. Learn more and you’ll generate ideas and enthusiasm for making other changes.

Reading books, not just random online articles, is especially helpful. An article can be penned in an afternoon, whereas most books take years. The result is that, when you read a book, you’re getting more concentrated thinking on a topic than shorter essays.

Books, however, are also harder to read. They require patience and attention that is often in short supply. As a result, I think it makes sense to single out some specific strategies for increasing the amount of books you read.

Let’s look at a few of these book-boosting habits…

Habit #1: Never feel guilty about putting a book down and starting a new one.

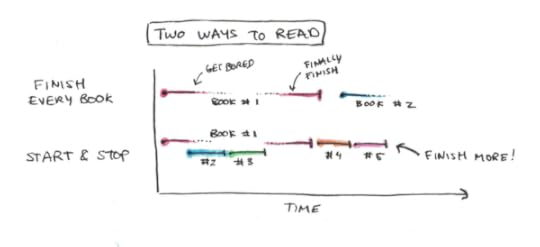

The habit I’ve had the most success with in increasing the number of books I read may seem like a paradoxical one. Isn’t the goal to finish more books? Why would abandoning them without hesitation be a good thing?

But the real cause of reading too few books is that you don’t enjoy it enough. The worst thing for your enjoyment is to feel compelled to finish a book that has become boring, predictable or unhelpful.

I often have ten or more books through various states of completion that I read at a time. I know I won’t finish some of those and that’s okay. The alternative—reading less—is worse than having a few go unfinished.

Habit #2: Build a library in your Amazon wishlist

Alternatively, if you have a Kindle or eReader, get samples of any book you might want to read.

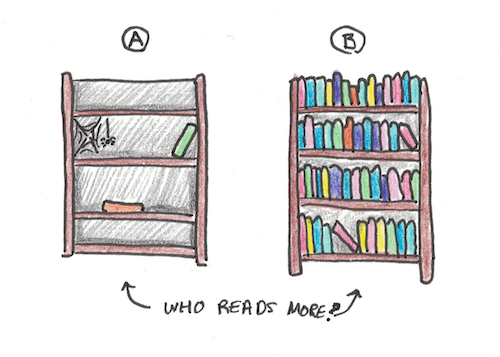

The goal here is to have an enormous pile of potentially good books. While getting stuck with a boring book may be the biggest obstacle to reading more, the second obstacle is not having enough interesting books waiting to be read.

I typically source my wishlist from suggestions from other writers and authors. Tyler Cowen has been a regular referrer of books since his reading volume dwarfs mine. But, in general, anytime someone recommends a book on a blog, tweet or in an email, I add it to my wishlist. I now have hundreds of books to choose from whenever I want to read something new.

Habit #3: Listen to more books

I love audiobooks. For some books, they’re better than text. Voice conveys more information than text alone, through tone and pacing. Therefore, for books where you want not just information but an emotional resonance with the ideas, audiobooks can be great.

But the real reason to listen to books is that they tend to increase your overall quantity since listening is possible in situations when reading is not. I read books on paper, on Kindle and through Audible. More media mean more opportunities to read.

Ignore the snobs who say listening to a book doesn’t count.

Habit #4: Progressively reduce your temptation to do something easier

You start reading. But it’s a bit slower and more effortful than Instagram or YouTube. So, after a few minutes, you decide to just pop over and see what’s on. An hour passes and your book has started collecting dust in the corner.

The biggest competitor to books these days is social media. I don’t think there’s anything intrinsically wrong with these services, but I also think they’re designed to capture and hold our attention much better than paper technology. Books, which require sustained attention, struggle to compete.

The solution is to silo off your time for attention-grabbing media so that the triggers don’t compete. One way I’ve found particularly successful is to limit your media use to certain times in the day, outside of which, you’ll read if you have spare time.

While this does require some effort in the beginning, it gets easier as you no longer have conflicting habits of reading vs checking Facebook at every moment in the day. Weaned of the habit to check in constantly and it becomes a lot easier to sit and read (or listen) to a book without fidgeting.

Habit #5: Set aside thirty minutes before sleep for reading

This habit works because it also helps you get better sleep. Too might light, particularly the bluer light from LED screens, activates brain circuits that tell your brain it is still daylight. The result is that it’s harder to start the subtle biochemical cascade that prepares your body for sleep.

While relaxing you, this habit will also let you accumulate a lot of books read by the end of the year. If you read 25 pages a night, you can finish more than thirty books a year with this time alone.

Another option is to turn off all the lights and listen to audiobooks instead. It’s a good placeholder activity if you have some difficulty falling asleep since it allows you to keep the lights off and keeps you from anxiously worrying about not falling asleep (one of the major issues with insomnia).

Habit #6: Delete social media from your phone, add Kindle instead

Turn your habit of constantly checking your phone into something useful. Having a Kindle app on your phone means you can always read a book wherever you are.

The problem most of us have is that we have other apps on our phone which are more attention-grabbing. If you remove those apps (or limit their usage to only certain times per day), you can reduce the impulsive need to check social media.

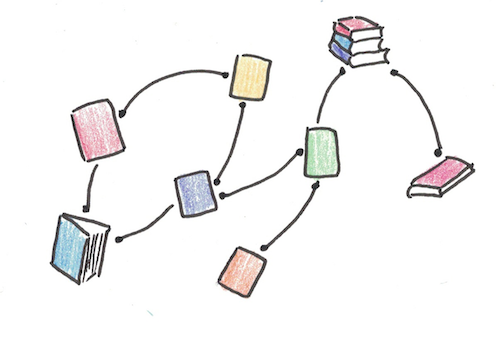

Habit #7: Create a deeper learning project

I like to read aimlessly. If a subject seems interesting or if the author is a good writer, I’ll read almost anything. This wandering is great for exposing you to bulk, positive randomness—giving you a chance to have creative insights in ways you couldn’t plan for.

But there’s also something satisfying about creating a deeper learning project. One that spans multiple books to really explore a topic you’d like to know in-depth. In this case, the goal isn’t just to read a book, but to try to understand a topic, question or field much better than you do now.

What’s a topic that fascinates you? What would you like to know much more about? The science of persuasion? The history of espionage? How your immune system works or how money is made? Pick a topic and make a cluster of books you can add to your list.

The benefit here is that, as you read more, you can also work toward bigger goals and topics. What starts as a reading list may even push you to an ultralearning project, where your goal isn’t just to read, but to turn that knowledge into an actual skill or accomplishment. Regardless of where you’re headed, reading more is a great start.

Change Begins with a System

Do you want to read more books this year? The key is to take action to modify your environment to support these habits now. Download Leechblock or modify ScreenTime to limit your social media. Talk to your family about starting a reading habit 30 minutes before bed. Take action now, and you’ll read far more in the year ahead.

Reading more books isn’t hard. But it does require making some changes to your habits so it will become automatic. Start today and you can end up reading thousands of more books over your lifetime.

The post Seven Easy Habits to Read More Books Next Year appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 16, 2019

Why is Taking Action Hard?

You’re supposed to write an essay, but you procrastinate. The treadmill is collecting dust in your basement. You want to learn a language, start a business or change careers, but those ideas go nowhere. Inaction is something we’ve all experienced.

Inaction, more than anything else, is the cause of our failures and our miseries. If we could consistently do the things we know we ought to, life would be much easier. Your projects would be more successful. Your goals would become a reality. Your life could be better.

We all know action is hard. But why? Why do we struggle so much to take action?

It’s easy to simply take this for granted, to assume laziness is just an intrinsic feature of the human psyche. But it’s also possible to imagine an alternative where action happened without so much inner struggle.

Indeed, you don’t even have to imagine a hypothetical universe to consider this possibility, because there are people who exist in our world who seem to be extraordinarily good at taking action. Arnold Schwarzenegger moving to America, becoming a famous bodybuilder, actor, entrepreneur, then politician. Elon Musk starting PayPal, Tesla, SpaceX and more. Marie Curie winning two Nobel prizes while raising a family as a widowed mother.

There seems to be an amazingly high correlation between the ability to take action and eventual success. Action and success are so closely matched, that it makes the struggles we have with inaction all the more perplexing. If success in life is often as simple as “do things, learn from them, repeat” why do many of us get caught in loops of laziness, self-sabotage and procrastination?

Some Possible Explanations for the Difficulty of Doing

There’s a lot of possible reasons why action is hard. Before I try to offer some explanations, however, I want to look at some theories that don’t do the job very well:

Talent. Talent, intelligence and serendipity are multipliers of your ability to execute. Obviously, Marie Curie was brilliant. That brilliance, combined with picking just-the-right research project, contributed to her discovering radium and making history. But while talent is obviously an ingredient in success, it doesn’t seem to be all that correlated with taking action. The world is populated by brilliant stars that flame out and mediocre minds that build empires.

Preferences. I have no desire for Elon Musk’s working life. I’m okay with the fact that this means I probably won’t have a similar level of impact on the world. That’s a difference in preferences, which likely explains part of the range we see in how much people are willing to work hard. But preferences can’t explain why we struggle with ourselves so much. Why procrastinate forever on an essay you know you’ll do eventually? Why start learning the language for weeks if you know you’ll never get to a level where you can use it? Preferences can explain failing to try, but they don’t work well to explain our inner struggles with inaction.

Capacity for effort. Perhaps effort is simply a different kind of talent, different from intelligence. Have a large capacity and you can easily do a lot of things. Have a low capacity and everything is a struggle. While this explanation does seem partly true, it doesn’t match the pattern of struggle we experience. If your capacity for effort is lower, why wouldn’t this just slow you down, rather than have you experience chronic bursts of activity with inevitable crashes in your goals and projects?

Motivation. Many of the people who have the hardest time taking action have the most reason to change. Someone leading a grossly unhealthy lifestyle will benefit the most from a small intervention, compared to the hyper-fit trying to lower bodyfat percentage by another 1%. If you define motivation as objectively having a good reason to act, then there’s still a big gap in action that needs explaining. If, instead, you define motivation as a subjective feeling, then we’re simply back to our original puzzle: why do some people feel motivated to do the things they should while others don’t?

My own thinking about the exact causes of inaction aren’t fully developed yet, but I want to try to flesh out some possibilities here, as well as give myself some directions for digging in further.

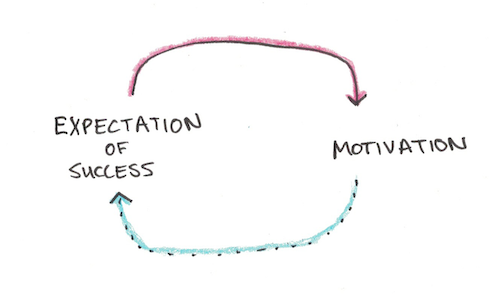

Possibility #1: Confidence

A popular class of theories related to goal-setting are those known as expectancy theories. These are essentially theories that say your motivation to complete a task depends both on the value of the reward you anticipate receiving, as well as your expectation that you’ll actually get that reward.

Your expectations of success, however, also depends on your motivation. This creates a feedback loop where your own expectation of your ability to sustain motivation long-term influences your expectation of success, thus influencing your motivation long-term.

A positive feedback loop can create a system where there are two possible dynamics: an accelerating commitment as you think success is more and more likely, and thus get more and more motivated, as well as a spiral of lowered expectations as you get increasingly discouraged.

Since your expectations of one pursuit often influence future pursuits, this is also something that might stabilize into a general response of doing or inaction in your life. If your projects tend to fail, your expectations are low and motivation withers. If your projects tend to succeed, your expectations go up and motivation stays strong.

Possibility #2: Social-Desirability Bias

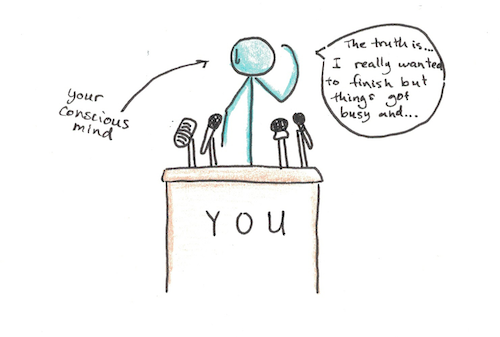

One view of the conscious mind is that it functions more as the brain’s public relations manager than as it’s CEO, confabulating reasonable-sounding explanations for its behavior rather than actually calling the shots.

If so, this suggests that many of our failures of action are intentional. We fail to take action because the unconscious parts of our mind that drive our behavior have decided not to take action.

Where this gets interesting as a possible explanation, however, is that sometimes inaction isn’t socially acceptable. Thus, we need to feign taking action in order to suggest to others that we do care, even when we don’t. This pretending may even be completely unconscious. The easiest way to lie is to believe you’re telling the truth, so you may even convince yourself you want to pursue a goal when really your unconscious mind is not committed to it.

This might manifest itself in the student who procrastinates on his homework (but doesn’t know why) because he doesn’t really want to study, but has to get the approval and financial support of his parents. Inner friction and anguish may be the price he pays for needing to appear like he’s trying to take action.

Possibility #3: Daydreams Feel Different From Reality

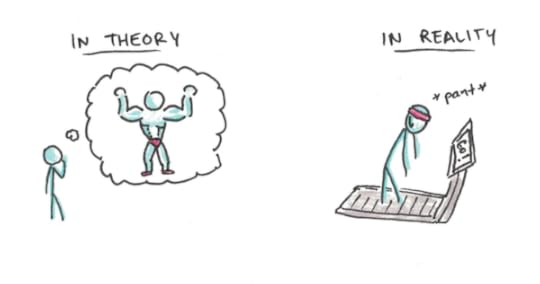

Construal level theory is the idea that we have two characteristic modes of viewing things—an abstract (or far-mode) and a concrete (or near-mode) view.

Many big goals have a far-near incompatibility which can make them hard to take action on. You might think about your fitness goal in terms of losing weight, being healthy and looking great (all abstract, idealized goals). Yet, when you go to the gym you mostly think about how hard you’re breathing, the sweat dripping down your face and how uncomfortable it makes you.

Chronic issues of starting and stopping difficult projects likely depend on this incompatibility of mental states. The person who dreams up the goal is different from the person who executes on it, and coordinating those two versions of yourself may be hard.

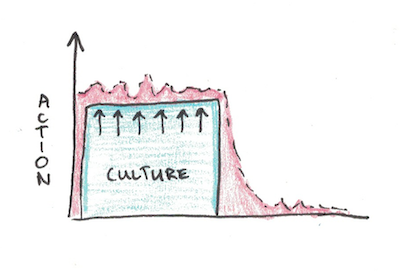

Possibility #4: Don’t Stick Your Neck Out

It may be that our hardwiring for ambition itself is based on our environment. Many of our ancestors lived in times when standing out, taking actions that go beyond cultural expectations could get you killed or exiled. Our natures, then, may be trying to sniff out the cost-benefits of taking actions, willing to retreat to placid conformity in case those early ventures get punished.

This might make for a theory of motivation that says, “do whatever your culture requires you to do,” with ventures into different kinds of actions being strongly discouraged if they don’t yield big rewards.

This may also explain why inaction seems to happen with some areas of life (starting your own business), but not others (showing up to work on time). In the second case, there’s a strong cultural expectation that everybody needs to show up on time to work, whereas nobody will blame you for not starting a company.

Our inner struggles may be our unconscious minds trying to find the frontier of action-taking that we’re best suited for, adjusting our ambitions and overall tendency to act based on feedback from the environment.

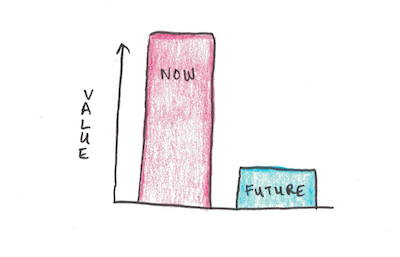

Possibility #5: We’re Too Short-Sighted

It may also be simply that our modern environment, which is peaceful, stable and allows for long-term accumulation of skills and resources, is quite different from the one we’ve evolved to survive in.

In particular, human beings exhibit inconsistent time preferences for satisfaction here and now, versus long-term rewards in the future. Procrastination may be a delaying tactic to avoid wasting energy here and now, even if you think you might work harder in the not-so-far future.

The ability to accumulate resources likely only started after the Neolithic revolution, where grain agriculture allowed some to save (and steal) and where long-term planning could actually result in evolutionary success.

This may be too short a time-scale to effectively modify our innate psychology, but it may have allowed us to create cultural institutions that counteract our typical short-sightedness. Since, once again, inaction is most prevalent when we’re facing activities without strong cultural pressures, this may suggest that our gap of inaction is due to defaulting to our ancestral, myopic approach to life.

How Can We Get Better at Taking Action?

This subject, why we struggle to take action and how we can improve it, is one that fascinates me. Both because it seems so simple on the surface (“Just do it.”) but so complicated underneath (what do you do when “Just do it” doesn’t work?).

Traditional approaches to this problem have often focused on human will as single thing. But the reality is that our minds are fabulously complicated things, with many different integrating control mechanisms, both conscious and unconscious. To take action, then, you need to not only have new inputs to your conscious mind to nudge you in the right direction, but those nudges need to translate into all the other control systems you possess to keep you headed in that direction.

I have a lot of remaining questions:

Are there different types of inaction, or do they all have a similar core explanation?

What separates everyday inaction from the clinical difficulties people who suffer depression or anxiety face?

Are these simply extreme versions of the slumps and avoidance we all face, or are they separate mechanisms?

What points in the system are most flexible for adjusting long-term action for the least amount of effort?

As I learn more, I’ll do my best to share it with you.

The post Why is Taking Action Hard? appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 9, 2019

Why Care About Learning?

A few years ago, when I was planning on writing Ultralearning, a couple well-meaning friends told me not to do it. “People don’t care about learning,” they told me.

Having reached the Wall Street Journal bestseller list, I’m glad they were wrong. Not merely for my own career as a writer, but because given how much I care about learning, it’s sad to envision a world people don’t care much about it.

I’m not fooling myself. I know that, on the whole, most people would rather debate politics than governance, read gossip rather than science or indulge in comforting superstitions rather than grapple with a complex reality. But I’m happy, at least, that the space of people interested in learning is large enough to support me and my work.

In recording dozens of interviews for Ultralearning, I often get asked why I care so much. Often the person pokes at my childhood or other life experiences that make me so interested in learning. But I prefer the flip-side of the question: how can it be that other people aren’t interested?

Why I Care About Learning

I wrote Ultralearning with a practically-minded thesis: learning pays. Being good at things matters. So even if you’re a philistine at heart, being able to efficiently acquire hard skills matters for your success in life.

But deep down, this isn’t my motivation to learn things. I’m eager to learn things because the world is deeply interesting. Far more interesting than we imagine. Maybe even more interesting than we can imagine.

Boredom, not curiosity, is the attitude that requires an explanation. How you could see glimpses of the world around you and feel that there wasn’t anything worth knowing more about is the truly baffling response. Daunted, I understand. Bewildered, I feel as well. But bored? That’s an insane response to the world around us.

Our Interesting World

Inside your body right now are a trillion cells. Each of these cells is more fantastic a machine than has ever been constructed by humans. We sit inside a galaxy of a hundred billion stars. And in a visible universe of a hundred billion galaxies.

Space and time aren’t flat. The axiom of geometry that the Greeks thought was a logical requirement turns out to not only be unnecessary, it’s not even true of the world we live in! At the base of this reality are things that would puzzle the characters of Wonderland—objects that have to spin around twice before they’re facing the same direction, wiggle in waves like the strings of guitar and bounce off cliffs instead of falling down them.

The moments we live in are an infinitesimal sliver of human experience. Millions of lives were lived and written down, billions more exist beyond that. Every problem you’ll ever face in life was faced by a thousand others, and they recorded how they solved it.

Within this life, there are more things you could possibly get insanely good at than you’ll have time for in a thousand lifetimes. Countless things you could be so passionate about that they would feel like the purpose of your entire existence. Near-infinite masterpieces you could create, theories you could invent, works you could build. The space of possibility dwarfs what even the most ambitious person could ever realize.

Boredom, that’s what I don’t understand.

Feeling Small and Weak

I remember looking up at the stars one cloudless night, remarking on how incredible it was just how far away and big everything that surrounded us was. Mentioning this, my friend told me the opposite—that the space was frightening. If it’s so big, after all, doesn’t that make us very small?

We don’t like to feel small. We don’t like to feel confused. Perhaps boredom and apathy aren’t a decision to ignore the wonders of the world around us but a reaction to them. The first explorers of new worlds saw amazing things—but those new wonders often killed them. If the space of things to learn is phenomenally vast, it’s also easy to get lost.

Some of the difference in reactions may just be innate. Openness to experience is one of the big five personality variables, and likely there’s some inherited hardwiring that separates whether the vastness of things to learn makes you feel awe or awful.

However, I suspect part of it is also the explorer’s skill. When frustration doesn’t yield fruit, it becomes an unconscious signal not to explore further. Climb into the jungle and get scratched by thorns, and you learn to stay indoors. Only if that frustration gets resolved, that you experience the joys of discovery, will the scrapes along the way not seem to matter so much.

But this, to me, suggests as well that people could be much happier and lead far more interesting lives if they knew how to learn better. Not simply the kind of knowing that comes from understanding principles like retrieval or spacing, although those do matter, but the deeper kind of knowing, when you know deep down that the world an incredibly interesting place.

The post Why Care About Learning? appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 2, 2019

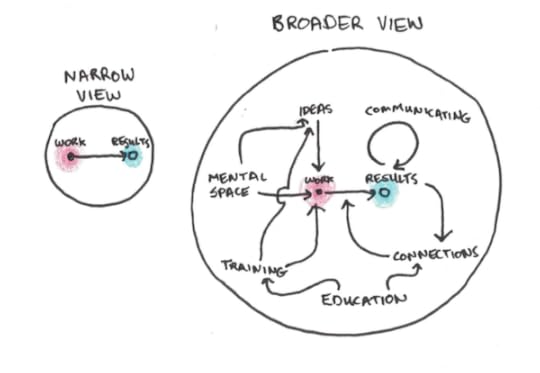

What’s the Point of Productivity?

Could productivity be a bad thing?

I had a podcast interview about Ultralearning recently where the host asked if being productive might be overrated. Working all the time, striving for ever-more efficiency, aggressive efforts to get more done, maybe chasing productivity isn’t the answer?

I couldn’t disagree more. Productivity features a lot in my writing because I believe it’s central for living and working well.

Yet, I often don’t say this explicitly. The value of productivity is so obvious to me, that I rarely articulate my assumptions about it. Today I’d like to share my vision of productivity, why it matters and why some critiques productivity are misguided.

What Productivity Isn’t

Before I explain my view of productivity, let me separate it from some related ideas it tends to get lumped in with.

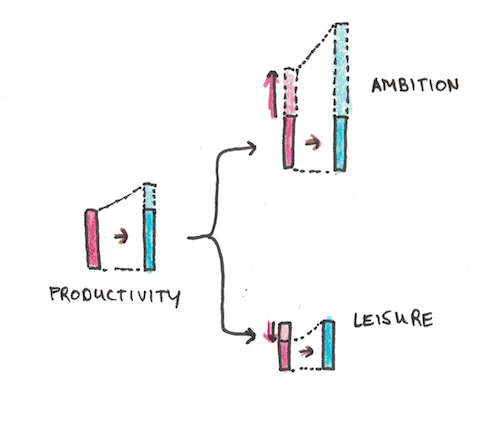

Productivity is not work ethic or hustle. The decision to work a lot is a question of values—how important is work in your life? Productivity, in contrast, is about how do you accomplish the most, given how much time and energy you want to devote to work.

Elon Musk is productive. He’s also a workaholic. His 100+ hours of work each week pays off, but it requires an obsessive commitment.

I have another, much less famous friend, who works from home as a programmer. In his role, he only has to spend a few hours per day to keep up with his workload. This is also highly productive, but my friend chooses not to reinvest his saved time into ever-increasing ambitions.

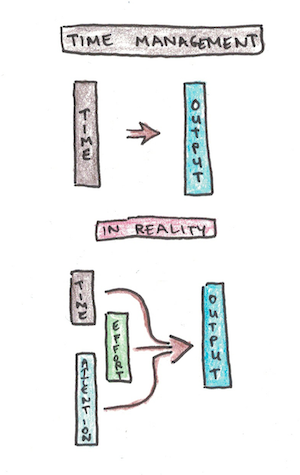

Productivity is not time management. Time management is based on the idea that the main bottleneck for accomplishing important things is the number of hours in the day. Therefore, the person who endlessly optimizes every sliver of time is the one who gets the most done.

But this approach doesn’t work. Time is nearly always more plentiful than effort. Productivity means maximizing your capacity for important work, not injecting more and more busyness.

Productivity is not just doing things that look like work. Conversations with colleagues, long walks to think, taking naps when you’re tired, vacations and hobbies can all be enormously productive, in the broader context.

What Is Productivity Then?

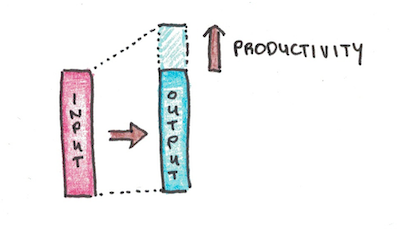

Productivity is a measure of your output divided by your input.

Output is measured by the importance of the accomplishment to your goals. A person who outputs lots of unimportant stuff is still unproductive. Importance, not sheer volume, is how output ought to be measured.

Input is measured by the time, energy and attention you have available. Sometimes this translates to speed. Other times it translates to ease or sustainability. Big impact, given your limited capacity, is the goal of productivity.

I care deeply about my productivity. But this doesn’t translate into working non-stop. In a typical day, I:

Usually wake up without an alarm.

Take a 20-minute nap if I need one.

Go on walks during the day.

Spend large chunks of time reading.

Have conversations with colleagues and coworkers.

From a traditional perspective on work ethic, I look downright lazy. Yet, I believe my output speaks for itself. In the last decade I’ve published millions of words of essays, five books and finished big, public projects.

My situation is unusual. I have enormous flexibility in my working life. However, that flexibility itself is a result of past productivity which has generated the career I have today.

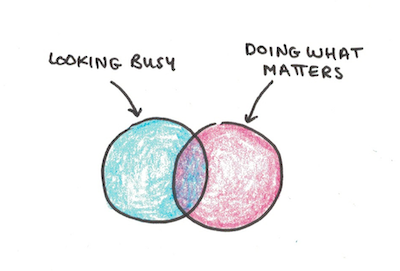

Appearing Productive VS Being Productive

Unfortunately, productivity is often judged on what it looks like you’re doing. A lot of the hustle culture and obsessive work ethic among entrepreneurs, ambitious employees and students is actually this—signaling to everyone outside that they’re serious about working hard.

This can be a cancer in an organization. Employees don’t leave the office until 9pm or later, to prove to everyone how committed they are. Meanwhile, nobody is actually getting meaningful work done. The twelfth hour of work devolves into a corporate hangout session.

This impacts entrepreneurs just as it impacts employees. I knew a guy, years ago, who was trying to bootstrap his online business. He made a big deal out of the fact that he was working 12-hour days, 7 days a week. But he was a frequent poster on message boards, discussing entrepreneurship rather than building his company.

This urge to signal is largely unconscious. Sometimes we do it to show our boss and coworkers that we’re a “team player.” Other times, we do it to quell the anxiety we have over the fact that we rarely have total control over whether we reach our goals in life.

When I defend productivity, it’s this attitude of conflating appearances over the real thing that I want to combat. Since productivity is a measure of output over input, it’s a philosophy that deliberately avoids substituting that difficult measurement with one that simply looks like you’re doing a lot of work.

What If I Can’t Always Be Productive?

The truth is, in many situations, appearing productive is a necessary evil. Your boss won’t let you take a nap, even though you’re so sleepy you can’t concentrate. Your team wants to stay up all night “brainstorming” even though you think it would be better to split off and come together when you actually have something to discuss.

Productivity is an ideal. Sometimes reality gets in the way. But it’s one thing to admit we can’t always be productive, and quite another thing to argue that productivity wasn’t worth striving for to begin with.

This vision of productivity, as well, applies to some types of work more than others. A security guard’s job, most of the time, is just to be there. In this case, output and input are largely inseparable—being really attentive for the first half of his shift won’t give him the opportunity to clock out early.

However, even if the idea of productivity isn’t universal, it can still matter for most people. For most of us, we will be evaluated on the importance of our outputs: software produced, essays written, research conducted, children taught, sales made. Better outputs for our limited inputs is a sound strategy for success in most types of work.

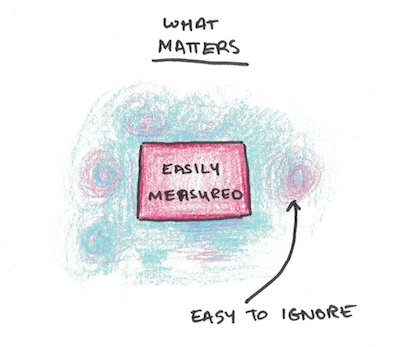

What is Measured and What Really Matters

Another critique of productivity is that it’s excessively driven by short-term output over things that matter, but are harder to measure.

This, I think, was the real source of the critique my interviewer had in mind. Don’t people obsessed with productivity often neglect the hard-to-quantify-but-ultimately-essential work that goes into achievement?

As a writer, I could measure my output by the number of articles written. Optimizing for that goal, I might write continuously, never reading a book, never discussing an idea with a friend, never thinking deeply about what I do. Raw output goes up, but impact goes down.

This, however, isn’t a critique of productivity so much as it is a critique of how we count it. Just as I don’t support conflating the appearance of productivity with actual productivity, I also don’t support the short-term optimization of immediate outputs over long-term accomplishment. If this makes productivity harder to quantify so be it.

In Defense of Productivity

In the beginning of this essay, I made a contrast between being productive and being a workaholic. Productivity, as a measure of output over input, is value neutral. You can be productive even if your goal isn’t to make your entire life about work.

But that value neutrality also means that the pursuit of productivity can’t tell you what your life should be about. A set of tools can’t tell you what to build. But keep those tools sharp, and you can build whatever you’d like with them.

The post What’s the Point of Productivity? appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 25, 2019

The Neuroscience of Anxiety

Few things are as unpleasant as anxiety. With the explosion of interest in mindfulness meditation and books like The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, I’m hardly alone in wanting to worry less.

Recently, I read Anxious by NYU neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux. LeDoux is an expert on a lot of the neural processes behind fear and anxiety, and this book offers fascinating insights into the underlying mechanisms that make miserable.

At the same time, however, Anxious isn’t an easy read. Many sections involved deciphering neural circuit diagrams, trying to keep track of countless acronyms for minuscule brain regions. This essay is my attempt to summarize some of the main insights of the book to help my own understanding of anxiety and for anyone else who wants to worry less.

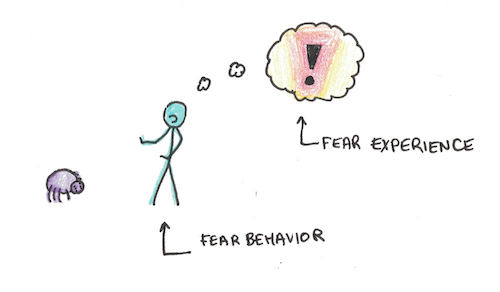

Fear and Consciousness

A huge chunk of the opening of the book is devoted to what, at first glance, seems to be a rather abstract problem: do the parts of the brain that are active when we observe fearful behavior really make us feel fear?

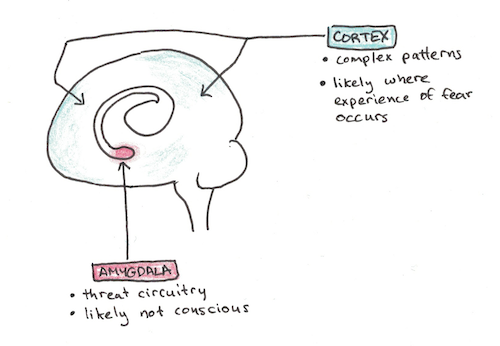

If you’ve followed any pop-sci articles on neuroscience, you’ve probably heard that the amygdala, an almond-shaped chunk of brain beneath the cortex, is the brain’s “fear center.” Scare someone (or a mouse in a laboratory) and the amygdala gets activated.

This has led to a wave of reporting that center our feelings of fear inside this little knob of brain tissue. This is unfortunate, in LeDoux’s estimation, because it’s not at all clear that signals processed by the amygdala are conscious at all.

Instead, LeDoux prefers the term “survival circuit” since, while it’s clear that the amygdala is involved in responding to threats, it’s not clear that activity here directly generates conscious feelings. Fear, as an experience, likely happens elsewhere, possibly in higher cortical areas of the brain that work with attention, thinking, imagining our futures and remembering our pasts.

Put another way, if a threat falls in the amygdala, but there’s nobody there to feel it, does it actually make you fear? To LeDoux, anxiety you don’t consciously experience isn’t anxiety at all.

Side note: Fear, anxiety and worrying have different, technical meanings. Fear is the feeling associated with imminent danger. Anxiety is the feeling of uncertain threat. Worrying is anxious and repetitive thinking.

The Adaptive Unconscious and Fear

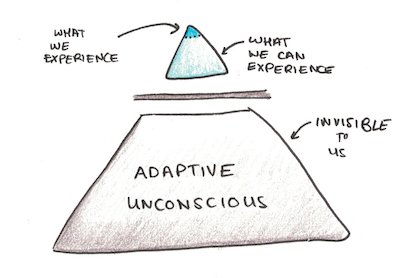

This division between nonconscious survival circuitry and conscious experience is reflected in more than just anxiety. In Strangers to Ourselves, psychologist Timothy Wilson argues that much of our mental operation exists outside of conscious thought.

The idea of an unconscious mind isn’t new, of course. Freud famously argued that our unconscious minds was a surreal dreamscape full of repressed desires about genital jealousy and wanting to romance our mothers.

This new picture of an unconscious, what Wilson calls the adaptive unconscious is much more mundane. The adaptive unconscious manages the business of living, often guiding our behavior without our awareness.

What we experience, of our mental processing, may not be just the tip of the iceberg, it may be merely a snowflake resting atop that tip.

What we experience, of our mental processing, may not be just the tip of the iceberg, it may be merely a snowflake resting atop that tip.A classic demonstration of the adaptive unconscious are priming experiments. If you flash an image, and then quickly flash a kind of masking stimulus, subjects cannot consciously report what they saw. You can tell they can’t consciously report it, because when asked to guess about what it was, they do no better than chance.

Nonetheless, if that image is of a frightening face, unconscious threat circuits are mildly activated. Although you may not be able to consciously notice any difference, behavioral responses, such as muscle movements in the face, can be measured.

Experiments such as these suggest that a lot of sophisticated mental processing not only happens beneath our everyday awareness, it is completely inaccessible to our conscious mind.

Where Do Feelings of Anxiety Come From?

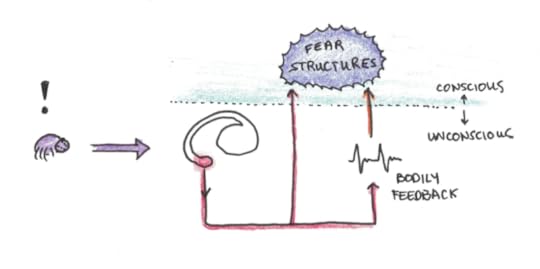

If threat circuitry isn’t directly conscious then, how does it impact our experience of anxiety which very much is conscious? In this case it’s likely that while the threat circuitry may not result in conscious experiences itself, it may trigger other mental processes which do cause us to worry.

One way this has been suggested is through bodily feedback. You experience some fearful stimulus, your amygdala and related areas react quickly and increases your heart rate. You feel your heart beating faster and your mind interprets this as fear.

While the bodily-feedback loop is a popular theory, LeDoux doubts it can be the total explanation. This feedback is probably just too slow for it to be the main pathway by which threat circuitry turns into conscious feelings.

Instead it might be that the amygdala triggers patterns in higher cortical areas which we can consciously experience as fear. In this case, the feelings we experience as anxiety are a downstream effect of the threat circuitry that we don’t experience directly.

Still, the coupling between threat-circuitry and feelings of fear is not perfect. As already discussed, it’s possible to activate the threat-circuitry mildly without creating any conscious awareness (although behavioral responses are still observable). Conversely, it might also be possible to feel anxious even if there are no threat-response circuits firing at all.

The overall feeling of dread and constant worrying that characterizes a lot of anxiety may not need a trigger from threat circuits to become active. It may be a purely higher-order mental phenomenon. As a result, interventions that work by clamping down on threat-circuits may not help much in these cases.

Threat-Circuits and Anti-Anxiety Drugs

This bifurcation of systems: a nonconscious threat-response system as well as consciously felt fear, may have implications on our ability to treat anxiety.

For instance, LeDoux notes that drug companies haven’t always had great success at discovering anti-anxiety medications. When something does help with anxiety, it’s often discovered by accident, rather than design.

The separation of threat circuitry from conscious fear may partly explain why. Drugs are often selected by their ability to reduce fear-like behavior in laboratory animals. In doing so, however, they may be operating on nonconscious rather than conscious circuitry. This may not help as much when the goal is to treat conscious feelings of anxiety.

Exposure Therapy

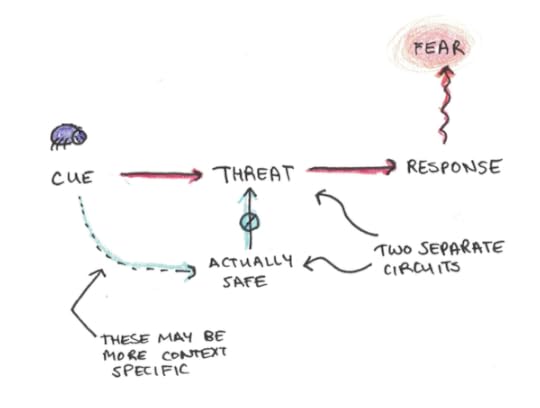

This perspective might also have implications for improving therapy as well. Exposure therapy is a fairly successful therapy for combating anxiety. It works by exposing a patient to the object of their fears. When they experience fear but nothing bad follows, the fear will be a little less next time. LeDoux notes that around 70% of patients do get some help from exposure therapy.

Success isn’t perfect, however. Spontaneous recovery, whereby a previously extinguished fear returns back, seemingly without reason, can occur. Stress or trauma can also trigger remissions.

One reason for this seems to be that the memory for threat and the memory for safety are actually two distinct neural circuits. When you initial learn the threat, and then later extinguish the threat circuit through exposure, this doesn’t work by erasing the original memory, but by creating a second memory designed to suppress the first one. It’s as if, instead of erasing the fearful picture, you’ve merely painted over it with a fresh coat of paint, one that might get scratched off later by accident.

Interestingly this memory for safety that suppresses the original threat response may be more context-sensitive than the threat circuit itself. If you learn not to panic at a social gathering while with your friend, you may still panic when that person isn’t there to accompany you. Reducing this context-sensitivity requires many different exposures in varying situations, otherwise the experience may not transfer.

Side note: Context-specificity shows up in another context—learning. In Ultralearning, I reviewed research showing that the things we learn tend to be more specific and context-dependent than we expect. That this shows up in so many different contexts suggests it is a fairly general principle of how our brains work.

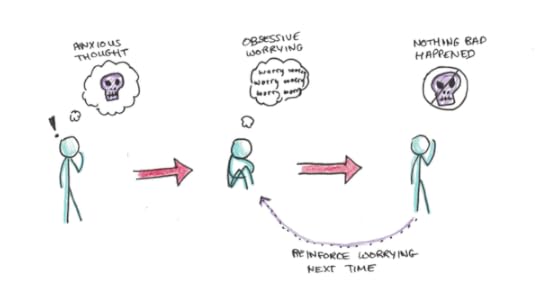

Why We Get Stuck in Anxiety

Anxiety can be self-reinforcing. Say you’re terrified of public speaking. You have an upcoming speech and you start feeling worse and worse about it. Finally, you come up with an excuse to avoid speaking. Now you feel better, whatever you were worried might happen can’t happen.

This actually creates a pattern of negative reinforcement. By removing something unpleasant (your anxious feelings) you reinforce the behavior that created it. Since what you fear never happens, the pattern to avoid what you fear gets stronger each time you feel anxious.

In nature, this pattern probably works fairly well. A rabbit that almost gets eaten while near a certain watering hole may never go back there. This may result in a little thirst, but it’s better than being eat by a crocodile.

The problem is that the avoidance strategy can work too well. It may be that the situation you’re afraid of is actually safe. By avoiding it, however, you never experience the disconfirming evidence that you don’t need to be afraid. In some cases, avoidance itself becomes worse than the thing you’re afraid of, as you take increasingly costly steps to avoid situations that might be scary.

Exposure therapy works to disable this feedback loop. Expose yourself to the thing you’re afraid of, and when nothing devastating happens, you diminish the fear response the next time. Repeat this and, eventually, the fear you experience will hopefully be mild enough so that it no longer interferes with your life.

While this is easiest to understand with phobias, there’s probably a similar avoidance reinforcement mechanism underlying a lot of more general anxiety and worrying. An imagined, fearful situation arises, and then you worry obsessively to find some possible escape. Since most catastrophic worries never actually happen, you’ve successfully avoided it and so the worrying behavior is reinforced.

Extinguishing Fears and Changing Beliefs

Modern exposure therapy, however, is usually more than just direct exposure. It usually also involves cognitive therapy, which involves talking about your fears. The hope here is to make explicit some of your beliefs so you can start to question them. Our glossophobe might worry that if he bombs on stage, his boss will fire him. This may not be realistic, but unless it’s made explicit, it’s very difficult to evaluate this thought pattern.

According to LeDoux, these two different aspects work on the two different systems that contribute to feelings of anxiety. Exposure targets the threat-response circuitry, a largely nonconscious response. Only change someone’s beliefs, but leave the threat circuits untouched and someone may still be paralyzed with anxiety even though they know it’s completely irrational. For instance, you may “know” that standing in a glass elevator is totally safe, but be petrified looking down over the edge.

Similarly, if you only extinguish the threat circuit, higher-cognitive systems may reactivate it later. You hear about plane crash and all of a sudden your worries about flying resurface in ways you can’t control.

Implications of Anxious and Further Thoughts

The existence of parallel nonconscious and conscious states, and indeed, treating the two as somewhat separate systems that both contribute to behavior is an interesting insight I gleaned from the book.

In my own life, I often find myself talking through my problems, either by myself or with others. Sometimes this process can help. Writing down my plans, worries, goals and problems in a journal, or discussing it with a friend, can often lead to new insights or reveal flaws in my thinking that lead to breakthroughs.

In other cases, overthinking is exactly my problem. Thinking leads to more thinking which goes nowhere. Particularly in cases where I’m worried, this thinking becomes compulsive and difficult to control.

This book suggests that neglecting the nonconscious processing may be a major weakness here. Since many of the mental processes happen outside of awareness, they can’t really be fixed by thinking about them more. Alternative approaches, such as exposure, may be more effective in these cases because they work on the problem more directly.

This book also echos another neuroscience book I reviewed earlier, The Hungry Brain. In that book, sophisticated circuits control how much we eat which can explain why dieting is so hard. Like anxiety, these processes happen without our awareness, yet seem to exert incredible sway over our lives.

In some ways, the existence of these unseen processes makes things more difficult. How do you make decisions when many of your actions are decided by processes you have no access to? How do you effect change in your life when the causes of your behavior are often invisible? How do you know yourself when so much is not open to introspection?

These questions don’t have easy answers. But I hope by exploring these, we might uncover new tools to worry less.

The post The Neuroscience of Anxiety appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 18, 2019

Top Performer Is Now Open

Top Performer is the course Cal Newport and I teach for helping you deeply understand what drives success in your career, and then gives you the strategy for getting really good at those skills. We hold sessions quite infrequently, and right now we’re opening registration for another one.

If you’d like to learn more about the course, how it works and whether it’s right for you, see the registration page here.

Everything you need to know about the course is in that link above, but here’s a quick summary of what we teach:

Research — We give you the tools to figure out how any career works and what skills you need to develop to reach the next level. This works for people early in their careers, still trying to figure out what they want to do. It also works for people who have already advanced in their careers and need to know what it will take to reach the next level.

Practice — We break down methods for translating the important research in mastery of deliberate practice to knowledge work. In particular, we teach you how to set up effective projects that will allow you to quickly build new skills and master ones that matter for your career.

Deep Work — Cal and I run through our productivity approaches with a focus on how you can maximize the amount of deep, important things you do every day.

Mastery — How can you set up long-term career habits to continually push your career forward. This includes how to assess your career capital, set long-term goals and stay focused on the big picture instead of getting bogged down in the day-to-day difficulties.

If you have any questions about the course, our team members will be happy to answer them here: support@scotthyoung.zendesk.com

Keep in mind, registration will be shutting down November 22, 2019 – Friday at midnight Pacific Time, so if you’d like to join, you’ll need to act before then.

The post Top Performer Is Now Open appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 15, 2019

A Subtle Mistake People Make When Trying to Grow Their Careers

In early Top Performer pilots (before we even called it Top Performer) Cal and I made a fairly subtle mistake about the process of acquiring career skills. It’s one I’ve seen many people make when thinking about improving their career, so I think it’s worth exploring here in case you might be making it too.

A big part of our course is creating a skill-building project. The goal is to cultivate rare and valuable skills which form the foundation for a successful career.

What I hadn’t recognized in early iterations of our course is that there are actually two subtly different ways to go about it, one of which tends to be more effective.

The Difficulty with Drilling Down

The first way you can design a project to upgrade your career skills is to drill down on some aspect of your work that ought to be important. One of our students was an academic philosopher, and so he decided to get better at logic. Another student was an architect and decided to deepen his understanding of design.

Drilling down works by getting specific. You pick a part of what makes someone great, focus on it exclusively and, hopefully, get better at that slice of what makes someone a top performer.

On the surface, drilling down sounds like it should be helpful. Indeed, the entire idea of deliberate practice, upon which our course is based, seems reflected in it—pick an aspect of your work and design an effort to focus on improving it deliberately. So what’s the problem?

The problem is that a lot of these projects didn’t generate spectacular results. Sure, the person might have felt good about deepening a skill, but these were rarely the projects that resulted in promotions, raises or transformations of a person’s work.

True, there were some exceptions. One person decided to dig deep on their understanding of a programming language, and later translated that into landing his dream job.

But even then, the mechanism underlying success wasn’t just from improving a skill alone. In his particular case, he got the job because his practice activity (making online quizzes about the language he specialized in) brought him to the attention of experts in his field. Had those quizzes not been published (or acknowledged) and it’s unclear how big an impact his project would have had.

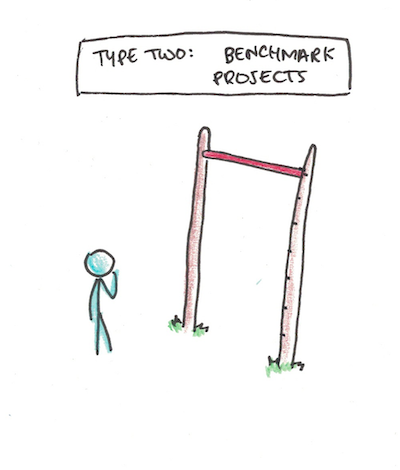

Benchmarking Success

A different style of project, however, does seem to work better: benchmark projects.

Benchmark projects are also about improving skills. However, instead of picking a skill and just trying to do work related to it, they work by first picking a clear benchmark accomplishment that defines success. Examples of successful benchmark projects could be:

Writing – Creating a blog and producing 100 articles.

Programming – Designing a popular open source library.

Academia – Producing a paper that has a higher impact than your previous work.

Entrepreneurship – Creating a new product that will sell more.

Why are these projects (often) more successful than projects which are strictly about drilling down on a particular skill?

My experience tells me that there are two distinct advantages to this kind of project. The first is that by tying your project to a benchmark, you can’t avoid the uncomfortable work. A deliberate practice project that is disconnected from real-world results can unintentionally be steered away from the outcomes that actually matter.

Second, benchmark projects produce a recognizable achievement at the end. This also helps by allowing you to point at something when trying to articulate your newly acquired skill. Good work alone can propel you forward, but making your skills more legible to outsiders is often a key part of translating those skills into actual career benefits.

How You Can Create Benchmark Projects to Grow Your Career

The way I like to think of benchmark projects is to pick something that I can’t do right now, but I might be able to do, if I improved my skills and worked at it.

These projects tend to work better when the benchmark itself suggests what kind of efforts you might take to improve. Improving as a writer, for instance, it would be better for me to pick a project like, “Get published in a national newspaper or magazine” rather than “Sell one million books.” The former will suggest a lot of specific actions I need to take to get my writing to the level where I could be published in a prestigious place, but the latter doesn’t really suggest anything concrete.

Good benchmark projects are often scarier than drill-down projects. “Getting better at research” is a lot more comfortable a goal to set than, “Get my work published in a Top-5 journal.” Yet that discomfort also encourages you to take a hard look at your own work.

What are some benchmarks you could strive to attain in your own work? How would those look different than attempts you’ve made in the past to simply “get better at my work”?

The post A Subtle Mistake People Make When Trying to Grow Their Careers appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 11, 2019

The Obvious Way to Improve Your Career (That Might Not Be So Obvious)

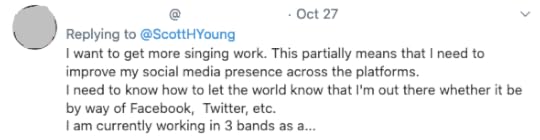

Sometimes the obvious advice you need to hear isn’t obvious to you. Here’s an example of this that happened just last week.

A guy on Twitter asked me if I did coaching. He felt stuck in his career and wanted to pay me to give him advice. I don’t do individual coaching (at least for money) but, I was curious so I asked him to send me some details of his situation to see if I could help.

Here were his tweets:

What do you think his mistake was?

…

In my mind, the biggest mistake he made was simply that he was asking me what to do next. I’m not a singer, and I don’t even work in the music industry.

So, lacking specifics, I gave the advice that was obvious to me: you need to locate people who are 2-3 steps ahead of you in the kind of career you want to have. You need to talk to these people, not just random people on the internet you admire to map out how your career actually works.

His response:

This seems obvious in retrospect, but it actually happens a lot.

In early pilots for our course, Top Performer, Cal and I had students work through an exercise of interviewing someone in their field for career advice. One person decided he wanted to pick Tim Ferriss, even though he was working an engineering job.

The problem is that Tim Ferriss isn’t an engineer. He’s an author, podcaster and investor. If you’re not in one of those fields, the advice Tim could give (if he was gracious enough for an interview) would have to be restricted to highly generic advice.

In fact, even if you are an author, podcaster or investor, it may not be the case that Tim Ferriss will offer super helpful advice. Why? Because Tim Ferriss is incredibly famous! For most people, Tim Ferriss isn’t 2 or 3 steps ahead but a dozens of steps ahead. His advice for a new podcaster is going to be hampered by the fact that when he launched his podcast, he was already a minor celebrity. A lot of his personal experiences won’t translate to someone just getting started today.

The Strategy and the Map

To succeed in your career—whether that’s becoming a singer, starting a business, earning tenure or just getting a job—you need two things:

A strategy. This is a high-level, abstract process for generating career improvements.

A map. This is a low-level, detailed picture of what your career looks like, concentrating on the areas that surround you.

The strategy is important—it’s one of the few areas where having the right approach to your career can make a big difference. Top Performer, is geared towards providing this half—giving a set of tools for thinking about your career and making progress.

But, in addition to your strategy, the map is essential. Importantly, you need to have the details about your immediate vicinity.

Imagine if you had to plan a trip, but you had only the map below?

Now contrast that with a map where all the roads have been filled in:

Regardless of where you are heading, the second map is going to get you much further. You’ll get lost less. You’ll know which streets are dead-ends, and which routes have traffic jams and where the expressways are. Without a map, you’re just wandering in the general direction of your goal.

Mistakes You’ll Make When Drawing Your Map

Being able to draw an accurate map is one of the skills Cal and I emphasize in Top Performer. Indeed, we spend the first two weeks of our course on getting the skills to get it right. Over the last several years of teaching the class, we’ve noticed all sorts of common mistakes that would-be career mappers make:

Obvious Career Mistake #1: You mostly ask for general advice.

Finding the right people, those people 2-3 steps ahead in their careers, is the first step. However, when talking to these people, many would-be mappers get mostly general advice—work hard, make connections, don’t give up. What gives?

The answer is that if you want good answers, you need to ask the right questions. Asking someone what they did, rather than for abstract advice, is a better question because it focuses on specifics, not generalities.

Obvious Career Mistake #2: You copy the surface, not the cause.

What time does the person wake up? Do they have a kale smoothie for breakfast or oatmeal? Apple or Android? None of these things matter…

Another mistake you can make in your map is looking at surface characteristics—obvious habits, quirks or beliefs that the person you admire holds. Instead, you have to look at what is driving their results. What skills have they mastered? What assets did they build? What projects did they cultivate?

Obvious Career Mistake #3: You plan a route that’s easy, even if it’s not pointed at your destination.

Often the kinds of efforts that will move forward your business are hard. They are uncomfortable. They require doing things that you (currently) have no idea how to do.

Many people pass on these to pick hobby projects instead. Projects that are fun, seem related to their career, yet, ultimately deliver underwhelming results. Improving their social media marketing, rather than creating compelling content. Installing a new development environment, rather than becoming an expert in their language. Designing business cards instead of drumming up business.

How Can You Avoid These Pitfalls?

Knowing how to draw a detailed and accurate map of your career is the first step. The second is knowing how to navigate it. How to cultivate the skills, assets and signals that will move you forward in the direction you want to proceed.

Cal Newport and I are going to be reopening Top Performer, our course for improving your career, next week. If you’re interested in joining us on an eight-week program to develop the tools to understand your career and make progress towards what really matters, we’d love to see you in the class.

The post The Obvious Way to Improve Your Career (That Might Not Be So Obvious) appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 4, 2019

Meet Me and Cal Newport in DC (+ New Podcasts)

This Saturday (November 9th, 2019), I’m going to be in Washington DC. Solid State Books was kind enough to host Cal Newport and I for a conversation about Ultralearning.

If you’re in the area, I’d love to meet you in person:

What: Cal Newport and I discuss Ultralearning.

When: 4pm-5pm Saturday, November 9th, 2019

Where: Solid State Books, 600 H Street Northeast Washington, DC.

Have You Seen My New Podcast Yet?

You may have noticed I’ve released some new podcast episodes. The segments are short — usually around 5-15 minutes. I’m narrating some of my best articles, both recent and from the archive, so be sure to check it out.

Over the next few months, I’m going to be releasing twice weekly. If you’re a fan of podcasts, I’d really appreciate a review on iTunes, since that’s one of the big ways people find out about this kind of content.

The post Meet Me and Cal Newport in DC (+ New Podcasts) appeared first on Scott H Young.