Scott H. Young's Blog, page 30

March 9, 2020

What is Effort?

Recently, I wrote a piece asking why taking action is hard. Why do we so often struggle to take our ideas and actually do something about them? It’s tempting to just say people are lazy or unmotivated, but I think the question is a lot more complex and interesting than it first appears.

Related to this question is what makes something effortful? Why is it “easier” to watch Netflix than solve math problems?

Like taking action, this question risks being overlooked because of our familiarity with it. It’s “obvious” to us that television is easier than algebra, so we don’t bother to ask why. However, like action, I think effort is also more mysterious than it first appears.

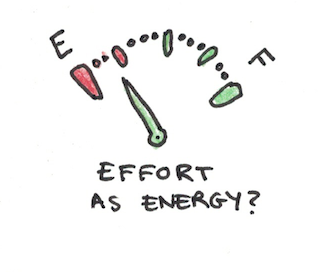

Effort as Energy Expenditure

A simple view of effort is that it simply represents an investment of a fixed resource, possibly calories or glucose.

Running is more effortful than sitting for this reason. If you run constantly, you use up more calories than sitting, and thus need to eat more to stay alive. Since calories were historically scarce, it might be that we have an aversion to effort because it keeps us from wasting energy.

Running also strains muscles and joints (if done excessively) so there’s another possible reason for making it harder. If you run non-stop, eventually your muscles will wear out, so preventing strain and damage to your body may also be involved in the effort in some activities.

This simple idea makes sense, but it breaks down when you consider it carefully. For starters, many activities that have similar caloric consumption or wear-and-tear on the body have wildly different amounts of effort required. Watching lectures in physics isn’t going to consume more calories than YouTube.

Neurological studies also show that glucose consumption in the brain, which was one of the hypothesized constraints for effort, doesn’t change very much when mental effort is changed, so this doesn’t work as a good explanation for effort.

Finally, sometimes we like to get up and move, expending more effort, rather than sitting still. Playing tennis is much more fun (and less effortful) than staring at a blank wall all afternoon, but the former burns way more energy.

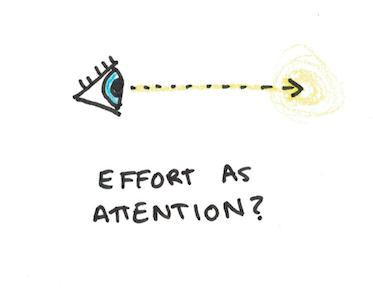

Effort as Attention

Other research points to a link between effort and the conscious mind. Attention seems to be linked to effort, as the deliberate control of attention is effortful. Daniel Kahneman, best known for his work on cognitive biases, even published a book arguing for this connection, Attention and Effort.

Still, attention alone can’t be the only explanation for effort. Some things are effortless to pay attention to, while others are hard to focus on for more than a few minutes. Watching an action movie and meditating to the flow of your own breath clearly illustrates that the object of your attention plays a big role in how effortful it is to sustain.

What makes focusing hard is that we’re trying to focus. That attention isn’t being held automatically, and thus needs conscious control, seems to be the relevant part for effort.

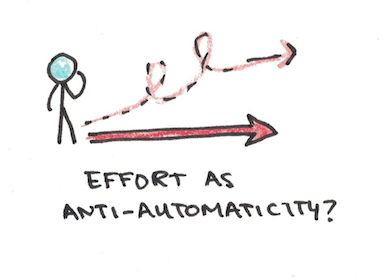

Effort as the Opposite of Habit

Another view of effort might be that it’s the opposite of something we do automatically. Certain behaviors and patterns occur automatically. This could be because they’re acquired habits or skills, such as always brushing your teeth before sleeping or knowing how to drive a car. Other automatic behaviors are instinctive, like pulling your hand away from fire.

Effort, then, is what happens when we try to override an automatic pattern. Driving isn’t effortful, except when you change countries and have to drive on the other side of the road. Then you’re counteracting learned behaviors, and this requires effort.

This would explain the difference between Netflix and calculus in terms of effort. For most of us, the latter involves a lot more conscious control of our thoughts and behavior, and therefore a lot more effort.

This explanation isn’t without issues, however. Games are often feel effortless, but they often require many deliberate actions that aren’t determined by habits. Doing household chores requires more “effort” yet this requires far less executive control over attention.

Effort as Moving Against the Balance of Rewards

Still another way of looking at effort might be to see it as occurring whenever you need to make a choice that involves some internal conflict. Part of you wants to eat another cookie, but a part of you thinks you probably shouldn’t. This tug of war between different parts of yourself makes self-control effortful.

In this view of the mind, we all flow towards certain default behaviors like a river flowing downhill. What requires effort is moving “uphill” or resisting this downward gravity.

What defines the path of least resistance, instead of gravity, is something akin to a balance of pleasure or pain. The more strongly an activity is associated with an immediate reward, the less effort it requires to continue. The more you need to override an action that flows along a path of greater reward, the more effort is required.

Are There Different Kinds of Effort?

I’ve given a handful of possible theories of effort, and there are likely more that I’ve missed. Rather than one of these being unequivocally correct, it may also be the case that the word “effort” encompasses distinct phenomena that aren’t always related.

So there may be a physical effort associated with calorie expenditure, that explains why you’re exhausted after an otherwise enjoyable soccer game, but that this effort is different from the kind spent working on math problems all day.

Similarly, there may be an effort involved in controlling attention, overriding automatic behavior patterns or otherwise choosing a path that has less short-term reward than competing options. These may actually be different kinds of difficulty, with different features and different obstacles, even though we often classify them as all requiring “effort.”

What Would Different Efforts Mean for Taking Action?

Returning to the question I asked previously about why taking action is hard, effort is clearly a factor. Action is hard because it requires effort. While that sentence is dangerously close to a tautology, it does match the phenomenon we have all experienced: some things feel easy and others feel difficult and this is a major reason we don’t always follow through on our plans.

Resolving this problem would have huge implications for our lives. If we could consistently follow-through on our plans, our lives would be much happier, more productive and successful. Even if following through on everything turned out to be impossible (as it likely is), then at least the self-awareness of when action won’t be forthcoming could allow us to accept our fate.

Yet, as the above explanations show, part of the issue might be that we’ve lumped together distinct problems: physical fatigue, attention control, automaticity, self-control, all under the label of “effort.” If we could tease apart these different impacts on the effort required for different tasks, we might be able to make changes to our environment, goals or tasks to ease the effort required to finally take action.

My own thoughts are that it’s hard to deceive ourselves about the effort of an activity. At the same time, the effort required to do things isn’t static. Habits and learning make frustrating things automatic. Our environment constrains our choices. Rewards for effort change as you do more of something.

All of these things suggest that even if exerting effort is hard, there may be detours that allow us to make some actions less effortful than they might be now. This would not only have implications for taking action, but also living better, given the amount of difficult things we need to do.

What are your thoughts? Why do you think some activities are harder than others? What might we do to shape the perceived effort ahead to struggle less with doing hard things?

The post What is Effort? appeared first on Scott H Young.

March 2, 2020

New Edition of Rapid Learner Coming Soon!

Rapid Learner is my most popular course on learning more effectively. It’s a six-week course designed to guide you through everything you need to know to ace your next exam, master professional skills or learn anything you care about more quickly and efficiently.

Over the last several months, my team and I have been working on major upgrades to the course. A major motivator for this upgrade was bringing some of the ideas and method in line with my recent book, Ultralearning. For those who read the book, but wanted more structure and detailed guidance, this course is a good fit for you.

What’s new in Rapid Learner 2.0?

Dozens of new and revamped lessons. These lessons were created not only because of new research I added in the process of writing Ultralearning, but also to address common issues that came up since the first edition.

Deep Dives: Notetaking and Spaced Reptition Systems. These lessons go into minute detail into how to take notes effectively, as well as how to use spaced repetition systems to remember anything. Walking through concrete examples with live footage from classes I’ve actually taken, you can see how to apply these strategies exactly.

New premium coaching add-on (limited capacity). One of the most frequent questions I get asked is whether I offer one-on-one coaching. With this next session, I’ll be taking a smaller group of students to work with me directly on their projects. This includes:

Weekly group live discussion sessions. Not only can you share your project with me and receive tips, but you can see the ideas applied in other projects as well.

Personal accountability system. If you want extra nudging to stay on track in the course (and your project!), we’ll be offering an optional accountability system to help you out.

One-on-one “office hours.” In addition to the group live discussions, I’ll also be holding regular office hours, so if you’re stuck in your studies, you can chat with me one-on-one to get advice.

Free for Old Students

Any previous student of Rapid Learner will get the upgrade to their course free of charge. Although this second edition represents a lot of new material, I want to make sure old students can benefit. When the new session is available, all the new lessons, revised lessons and deep dives will automatically be added to the accounts of past students.

We plan on opening the new session in early April, but I’ll announce the exact dates once all the finishing touches are ready!

The post New Edition of Rapid Learner Coming Soon! appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 24, 2020

How Does Age Change How You Learn?

As you get older, learning often feels harder than it used to. Why is that? What changes in the brain as we age that makes acquiring new information harder? Is there anything we can do to avoid our minds slowing down?

This is a topic I’ve been asked about a lot, but until recently one that I didn’t know much about. Aging wasn’t a topic I spent much time researching in my book, preferring to focus on principles of learning that are universal.

Recently, however, I decided to dig into some of the research on cognitive aging to see how our learning is impacted by getting older.

Learning Slows with Age

The first clear finding is that the feeling that one is getting slower mentally as we age is not an illusion—countless studies reinforce the fact that most aspects of mental processing get worse as we age:1

Interestingly, not all aspects of thinking get worse with age. Accumulated knowledge of the world increases until nearly the end of our lives, as you can see in the figure above with vocabulary size.

This is a trade-off between what researchers call fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. Even if our minds slow down as we get older, we accumulate more experience. We know more as we age, even if we’re slower at learning and processing new information. Wisdom increases even as wit declines.

What Gets Worse With Age?

There are different hypotheses about how our minds tend to get worse as we get older. A simple one is the idea that processing speed slows down as we age—neurons lose mylenation and so the signals that carry the currents of our thinking slow down.2

Other researchers disagree, arguing that aging impacts some brain areas more severely than others, resulting in specific deficits of cognition rather than an overall decline.

The frontal aging hypothesis argues that the frontal cortex is hit harder by aging.3 The frontal cortex is involved in many functions, but a key one is in asserting top-down executive control over our actions. This is often associated with the deliberate effort it takes to override habits or consciously keep intentions in mind when completing tasks.

Researchers Todd Braver and Robert West argue for a goal maintenance account of cognitive aging.4 Following the frontal aging hypothesis, this suggests that what is harder to do as you get older is to maintain and switch the goals associated with a task. This results in older individuals struggling more with Stroop tasks, where an automatic habit needs to be overridden by instructions:

Additionally, older individuals are hurt more by multitasking than younger people.5 This seems to be because multitasking requires switching the goals of the task at hand over a short period of time. Since older people have a harder time maintaining these, switching tasks frequently is particularly hard.

Another deficit observed in older individuals is difficulty with binding information that occurs in a combined context.6 Chunking is one of the most important parts of learning new information, so the fact that this becomes harder with age may explain why learning new things feels more difficult as we get older.

Difficulty binding information together to store in long-term memories also impacts our ability to remember our life events. Simple information is less impacted by aging, but as we get older we may start to forget the context in which something was learned.7 The person you walk by looks familiar, but you forget where you met him before.

The story isn’t all gloomy. In addition to crystallized knowledge, older people seem to be better at emotional regulation as well.8 Since managing emotions is an important part of success at many tasks, this suggests older people may be slower but surer at working on goals that have a bit of frustration baked in.

Do Different People Experience Decline Differently?

Do all people experience cognitive decline uniformly? Or do some people’s minds slip while others stay sharp much longer?

There seems to be a little conflict on this point in the research. One literature review I found argues in favor of cognitive decline being mostly linear as we age and not increasing in variance.9 This suggests that, absent illness, we’re all on roughly the same trajectory of cognitive slowdown.

The lefthand graphs show decline of cognitive function, while righthand graphs show the variability. At least according to this study, variability doesn’t show dramatic increases with age.

The lefthand graphs show decline of cognitive function, while righthand graphs show the variability. At least according to this study, variability doesn’t show dramatic increases with age.This review, in contrast, seems to differ.10 The authors argue that variance increases with age, which goes with our normal intuition that some people seem to experience large declines in thinking with time while others fair much better. This seems to match up with other evidence that most factors associated with aging experience increasing variability over time.

Redundancy and Cognitive Decline

One reason for the observation that some people seem to age mostly with minds intact and others notice dramatic slowdowns may be that the brain has a lot of redundancy built in. On a physical level, brain volume may be declining, but that this may not create noticeable difficulties for some time.

Cognitive reserve is the concept used by researchers to note that many individuals who experience decline on physical measures may not have related mental decline owing to this robustness.11

One way you can see this is in fMRI scans which show that older individuals’ frontal cortices are more active than younger people’s on comparable tasks.12 Since frontal cortex decline is common in aging, what might be happening is that the brain is compensating for reduced efficiency by increasing activation.

Researchers note that education seems to have a protective effect on aging.13 This may be because accumulated knowledge from education contributes to cognitive reserve, so as our minds decline, those who learned more when they were younger are better able to cope. Of course, another explanation might also be that those with sharper minds were more likely to go to school, and that education has no causal effect.

How Can Older People Reduce the Impact of Cognitive Decline?

There is some evidence that some aspects of cognitive aging can be overcome with training.14 However, I wouldn’t hold my breath for a magic fix. Age impacts our minds just as it does our bodies. Just as there is no exercise regimen that will allow a septuagenarian to compete in the Olympics, I doubt there are universal remedies for our cognitive declines.

However, the situation doesn’t seem to be completely without hope either. There do seem to be some things you can do to help your mental functioning.

The first is preventing cognitive decline. Exercise and eat well when you’re younger. Learning more when you’re younger may minimize cognitive decline. Even if learning doesn’t prevent declines in fluid intelligence, it still enhances crystallized intelligence, giving you greater knowledge in your older years.15

The second is to strategically control your environment to minimize the specific difficulties associated with aging. In particular, you should:

Avoid multitasking or environments with likely distractors. Since goal maintenance seems to be a central problem of aging, it means the older you are the more you benefit from an environment that allows your mind to focus on the problem at hand.

Be more strategic with creating cues and reminders for important information. Proactive memory, where you set the intention to recall something later, given a specific prompt, is particularly affected by aging. This suggests engineering your environment to remind you of your goals and tasks is more important as one ages.

Be more explicit in organizing what you want to learn. Binding pieces of information together to be recalled as a single chunk can happen both automatically and deliberately. Since binding is harder with age, it may make more sense to be deliberate about organizing information you want to learn.

A third idea relates to how you might allocate your learning throughout your entire lifetime. Since fluid intelligence and complex working memory peak in early adulthood, this suggests that time might be the best for learning skills where those are more important, such as mathematics.

In contrast, for subjects that require mostly accumulated knowledge and build off of past habits of thinking, age may be an asset rather than a liability. History and law, for instance, may benefit more from this accumulated wisdom and be more amenable to improvements later in life.

The idea that our minds change as we age, and thus change the relative ease of learning certain subjects shouldn’t be viewed fatalistically. Obviously, learning history when you’re fifteen or calculus when you’re fifty are both great. But understanding how age selectively impacts cognition can also help us to minimize the downsides of decline.

The post How Does Age Change How You Learn? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 17, 2020

How Fast Should You Be When Learning?

Normally when I talk about learning quickly, I’m using speed as a synonym for efficiency. Use more effective methods and you’ll learn more in less time. All else being equal, that means you’re learning faster.

Today, however, I want to consider a different meaning for speed: how quickly should you try to do things in order to improve performance.

One way to imagine this is to look at something like chess. Chess can be played at different speed levels: you could play tournament-length games, which take hours. You could play blitz, which has only a few minutes, or bullet chess where moves are counted in seconds.

If your goal were to improve at chess, which kind should you make your core practice?

Speed and Transfer

The first thing to consider is that often what we think of as a single skill is actually different skills when viewed from different timeframes.

Consider solving a math problem. You can painstakingly calculate an exact answer. Or you can ballpark it using some guessing. While the two skills are related, they are, strictly speaking, different mental abilities.

The research on transfer shows that when we train skills, they tend to be learned quite narrowly. So tons of time learning to do back-of-the-envelope calculations may not improve your calculating skills as much as you’d expect. This also works in the opposite direction as you may be able to get the “right” answer, but without a quick guess that’s in the ballpark.

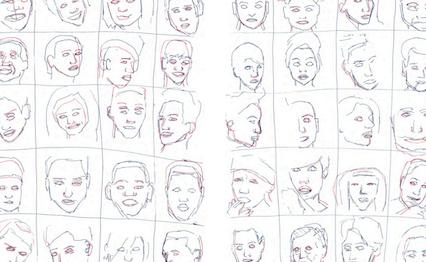

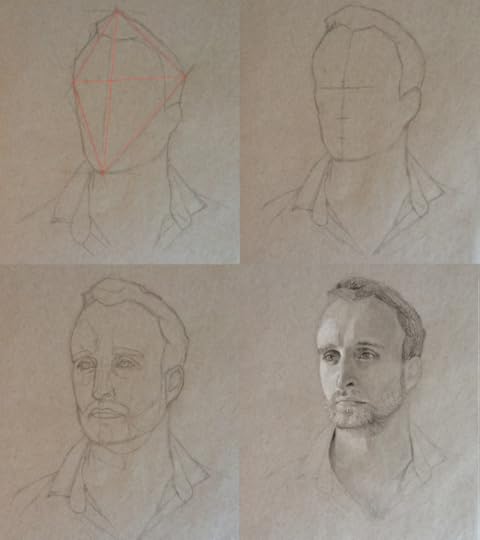

I experienced this firsthand when working on my portrait drawing project.

My initial thought was that drawing faces well came from “guessing” the relative positions of facial features, lines and shapes. Thus if I simply did more and more quick practice, my guesses would get increasingly accurate and I’d draw realistic pictures. Speed, then, made sense.

This worked, for a while, but eventually I found that my problem wasn’t accuracy but precision. There was too much variability in my guesses even if I wasn’t systematically making a particular kind of mistake.

The solution ended up being learning a different method for drawing based on triangulation, as taught by Vitruvian Studio. This method, in contrast to my guess-and-sketch approach, was not fast. My first attempts took hours. With practice, I could do it faster, but it was still much slower and more painstaking than sketching.

The result was that I got better at drawing portraits, but only weakly better at doing quick sketches. The skills I enhanced mostly worked when I had at least an hour to draw, not sixty seconds. If I wanted to get better at the sixty-second sketches, I’d probably need to master different techniques.

The lesson here is that the timeframe you need to perform a skill within often constrains the methods you can use to master it. The way you solve a problem in ten seconds is often, cognitively speaking, quite different from the way you solve it in an hour.

Are You Failing to Reach an Ideal or You Don’t Know What the Ideal Is?

A lot of learning involves having a mental representation of what the ideal performance ought to be, a method or approach to achieve said performance, and then working towards implementing that method with your mind.

There are therefore two distinct problems you can encounter when you’re trying to learn something. The first is that you have a clear picture of what you’d like to do, and how you’re going to do it, but you’re simply unable to implement the approach you’ve chosen. In these cases, slowing things down is usually better. By slowing down the speed of the overall process you can devote more attention to each aspect of the problem. Only once you’re able to do it correctly does it make sense to try to do it faster. Rushing this only results in making mistakes.

Drawing portraits, it was better that I focus on applying the method the best I possibly could, rather than artificially give myself time constraints, which would have caused me to mess up more things and have a harder time mastering the technique. Similarly, when I want to improve my writing, I usually form a clear idea of what kind of essay I want to write and slow down my process until that form is achievable.

The second type of problem, however, is when you’re not even sure what the ideal should be and need more information to figure this out.

A new writer may need to pen a dozen or more essays to get a sense of the kind of writing they’d like to create. You may need to do a few dozen sketches before figuring out where your artistic deficits lie. Faster means more feedback and solving these problems earlier.

The best example of speed leading to greater quality is often in entrepreneurial domains. The problems being solved here are often related closely to identifying what is the ideal to reach, as opposed to mastering the execution of that ideal. Many businesses fail because the founder picked the wrong problem to solve and wasted too much time trying to solve it.

Ask yourself, “Do I know what I’d like to do, and what approach I should take to do it?” Or, “I’m not sure what’s the right way to approach this?” The former suggests slowing things down, the latter suggests getting faster feedback. These aren’t the only considerations that matter for speed, but it’s a useful heuristic.

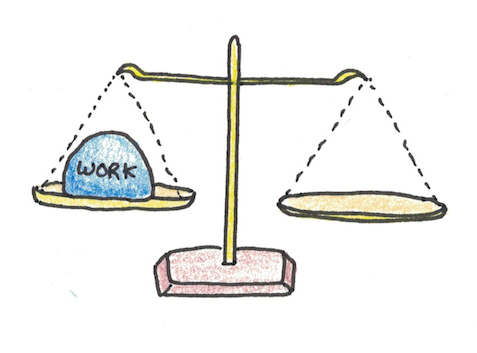

A Meta-Heuristic for Handling Trade-Offs

The balance between going faster and doing it right depends on a trade-off. Faster feedback means you get more information allowing you to explore the problem space to figure out what the key challenges are and possible strategies for overcoming them. Thus faster is better. Slowing things down, on the other hand, helps you home in on a strategy you’ve already chosen, allowing you to execute it correctly. Thus slower is also better.

Many (if not most) things you want to learn involve these kinds of trade-offs. You want to space out the things you want to learn to extend your memory, except not so far that you’ll forget. You want to take advantage of direct practice to minimize transfer failures but also do drills to give yourself more space to master components.

The meta-heuristic I use when dealing with these problems is to do both and feel out which seems to be helping more. So if I were unsure whether my struggles in a new domain were due to inadequate breadth of feedback or inadequate mental bandwidth to do things properly, I might spend ten hours doing both faster and slower practice and see which seems to be bearing more fruit.

If you can adopt the above approach you rarely get “stuck”, but it also requires more self-awareness to monitor your own progress.

The post How Fast Should You Be When Learning? appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 10, 2020

I’m a Papa!

My wife and I recently welcomed our first child into this world, Thomas. It seems my next ultralearning challenge is going to be learning how to be a dad!

I’m sure there will be plenty of life lessons from fatherhood that will make its way into my writing in the future. I’m planning on taking about a month of leave to be with him exclusively. In the meantime, I’ve queued up some writing I did beforehand. Enjoy reading that until I’m back!

The post I’m a Papa! appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 3, 2020

How Important is Work?

How important should work be in your life? What kind of relationship should you have with your career? If you don’t feel like you have that, what should you do about it?

I’m usually against overthinking wants and likes. Consider cilantro. Some people (like me) think it’s delicious. Others think it tastes like soap. No amount of convincing can make cilantro-haters learn to love the herb. The taste may even be genetic, so liking cilantro may just be an immutable part of your make-up.

Career preferences are somewhat similar. For some, work not only provides them with a living, it is their life. For others, a job is what you have to get by—the background of your life, not main scene under the spotlight. Who am I to argue with either?

But, today, I want to try to ask how work matters and see how it fits into life. Not a prescription, but an exploration, to see how our relationship with our career comes to be and how we might improve it.

Why Care About Work?

The obvious reason to care about your career is that you need money to live. Survival ranks higher than lofty ambitions, so for most of us, a job is simply a necessity.

But many things are necessities without deriving much focused attention in life. Eating is also essential, but I don’t derive the meaning of my life from food. Indeed, it often seems like the people who focus most on their careers are those who need it the least. The lawyer who puts in eighty-hour weeks to make partner isn’t worried about rent money.

But if not survival, then at least comfort is a major aim of work. Even if you could survive, strictly speaking, on a smaller income, it would often make life more difficult. Similarly, most of us can imagine a bigger house, nicer things or an extra vacation as being worth the effort of getting a better job.

This perspective, that work is mostly about material survival and comfort, is one story we tell ourselves about work. It’s obviously true, but whether this is the main plotline or not depends on the person.

There are, however, different stories that you can tell yourself about your work.

Work as Respect

A different story, perhaps the one that a majority of people living in wealthier countries tell themselves, is that work is about respect. Your work decides some of your status in society, and doing well in your career is about mostly about amplifying the respect you receive.

There’s an element of self-deception here. Work being about survival (or even comfort) sounds better than trying to gain more status. Vanity and pride aren’t attractive traits, so many people mask their underlying desire for respect under different stories about their work.

Often, the only way you can unmask the true motivation is to see the choices people make in their work. When they turn down options with greater financial reward for those with greater status, you can see that clearly respect ranks higher than money in their unconscious minds.

I think this story, of work-as-respect, is a big part of the reason college education has exploded. While it is true that college does pay people more, this is only an average outcome. For those who barely get in, a few years of school only to end in dropping out is a financial disaster.

In contrast, many trades have a shortage of qualified people, despite offering very high salaries. College-educated jobs offer more prestige and so people are willing to sacrifice on material comfort to attain them. Anyone who pays $30,000 per year to study psychology rather than plumbing is, in a partial sense, saying that prestige matters more to them than material comfort.

Respect is an important, often unconscious drive, in our work, but it’s not the only story we tell.

Work as Play

Normally we see work as something we have to do. But if it’s also something you enjoy doing, then you get both the financial rewards of work without having to sacrifice so many hours of your life on something that isn’t fun.

My own sense is that the story of work-as-play is important, but it tends to be overrated as an explanation for the work people pick. I tend to side with Cal Newport that most people don’t have pre-existing passions. Instead, people have the potential to like all kinds of work, as long as the conditions that surround work support it.

Indeed, many “fun” jobs are anything but. My friends who work in film, for instance, often complain about terrible hours, bosses or working conditions. Their passion comes with a price. In contrast, the friends who do “boring” jobs are often more satisfied since their work treats them better.

Still, play is an important story for work even if it’s probably downstream of other causes. Unsurprisingly, the jobs that are the most “fun” tend to be prestigious and high-paying. We’re quite psychologically flexible at finding rewarding things interesting.

Work as Purpose

In contrast to the intrinsic enjoyment one gets out of a job, your work is also a vehicle for creative self-expression and service. When you feel a job is purposeful, it not only provides a living, but a reason for being alive.

In many ways, this story is the exact opposite of the story of material survival. If your work is only for a paycheck, then it tends to be in the background of your life—friends, family or other personal goals often take center stage. In contrast, if your work story is one of purpose, it often steals the spotlight away from everything else.

What Creates the Story We Tell Ourselves About Work?

My sense is that there tend to be two forces that cause people to organize the meanings of their lives around certain stories: intrinsic and extrinsic.

The intrinsic forces are those, by nature of your personality or upbringing, tend to make you value some things more than others. As with cilantro, some of the feeling you assign to your career may be genetic. Others may be instilled from childhood. I’ve had friends for whom going to college was seen as uppity by their families, all the way to friends whose parents would disown them if they didn’t earn six-figures.

I think all of us have certain innate dispositions that lead us in some directions more than others. I don’t subscribe to the view that these dispositions are destinies, but I think it would also be a mistake to imagine ourselves as totally blank slates upon which any story can be written.

External forces also matter. I suspect that a lot of people alter the meanings of their lives in accordance with the kinds of experiences they face. If success in work comes easily, people are more willing to ascribe it importance in their self-conception. If it’s harder, centering one’s life around family, hobbies or spiritual pursuits might come more naturally.

However, I don’t think the stories we tell ourselves can be instantly reinterpretted in any way we like. Someone who values work in the extreme, and stumbles into professional failure, might persist for years in a state where the choice between overcoming adversity or telling themselves a new story remains unclear.

Should You Rewrite Your Story?

The meanings we ascribe to things tend to get fixed, the more we think of them that way. This stability is a good thing. Without it, life would become an incomprehensible mess.

However, rigidity of meaning can also get us stuck. If you’ve organized your entire identity around becoming a doctor, and you’ve failed to get into medical school for the third year in a row, what should you do?

When overly rigid meanings strain too much, they can sometimes snap. In 1837, in what was probably the most significant career failure of all time, Hong Xiuquan failed the imperial service examination for the third time. This lead to a nervous breakdown, deciding he was the brother of Jesus Christ, and kicking off the Taiping Rebellion which ended with a death toll of thirty million.

It’s healthier to have meanings somewhere between the two extremes. Stubborn enough, that one can persist through adversity. Flexible enough so that in the face of the obstruction of one path, you have the ability to choose another. Cultivating that correct degree of flexibility may be more important than the story you end up telling yourself.

The post How Important is Work? appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 27, 2020

Information Overload is a Fake Problem

The internet reachable by Google has over a million terabytes of data. Every minute 300 hours of new video is added to YouTube. In the time it took to read this sentence, at least 10,000 new tweets have appeared on Twitter.

We’re drowning in information, so it’s only natural to feel overwhelmed. Right?

I was asked about this in a recent podcast: how can you deal with information overload? On the surface, it seems like a completely reasonable question. There is so much more to read, watch and respond to that it can feel a bit overwhelming.

However, I think the explosion of data hasn’t really changed much about how we ought to stay informed. Most things aren’t worth reading. Of those that are, there’s an enormous amount of redundancy built in. The amount of truly original ideas worth learning is much, much smaller than statistics like I quoted above would lead you to believe.

On the (Relative) Paucity of Good Ideas

If ideas, as opposed to mere information, were truly exploding, we should be able to test this. Pick a few dozen important ideas, then ask when those ideas were first shared or discovered. If knowledge is growing exponentially, the majority of those should have been discovered in the last few decades.

Yet if you actually go through this exercise, the striking thing is just how old most of the important ideas are.

Quantum mechanics, that revolutionary physics that still baffles most of us? 100 years. DNA, the molecular secret of all life? Over forty years. The idea of artificial intelligence? Alan Turing spoke about it in nearly the same breath as he did in inventing a universal computer. Even the cutting edge “deep” learning strategies are largely based on algorithms that are decades older, but for which the technology wasn’t quite fast enough to make powerful until recently.

What ideas of the last decade or two will stand out as truly being worth learning in another hundred years? Blockchain? Quantum computing? CRISPR? Exciting developments to be sure, but the list is far, far smaller than the explosion in the Internet makes it first appear.

If anything, the rate of genuinely good new ideas worth learning may actually be slowing down, the opposite of what information overload suggests.

If Good Ideas are Rare, Why is the Internet So Big?

To be fair, the number of good ideas worth learning is still large enough that few can reasonably manage to understand more than the general outline of most of them in their lifetimes. However, this was also true fifty years ago, well before the idea of “information overload” had become popular.

If the explosion of “stuff” on the internet isn’t matched to an explosion in good ideas, then what’s all the stuff?

A cynical answer is to say it’s all noise, that nothing worth knowing appears online and we should all go back to reading the classics.

My own response is simply that for every good idea, there are many, many different ways of expressing it. That includes this very article you’re reading now—my own little take on some of the more fundamental facts around us. Different expressions of ideas can be useful, but they also include considerable redundancy.

As someone who is responsible for his fair share of redundant “stuff” online, I’m happy we live in a world where there are many different ways to teach and express fundamental ideas. I’m happy they can be reassembled and debated in so many different ways to allow interesting conversations.

But this prevalence of content isn’t the same as an overload of information.

What’s the Real Problem?

I think the real problem with the information available is that most people aren’t deeply interested in learning the important ideas. For them, the information represents entertainment, distraction, gossip or fashion. Knowing the deep and useful things isn’t high on the list.

The inverse of that, however, is that if you are really interested in understanding the world, the deluge of redundant manifestations of those ideas is super helpful. If you don’t understand an idea one way, you can read about it from a hundred different perspectives, one of which will likely click with you.

How do you know which ideas are truly important? This is also, largely, a fake problem. The important ideas are the ones that keep showing up, again and again, allowing you to understand the other things you’re learning and doing.

Ideas are important because of their frequency and utility. An idea that keeps being referenced when you’re learning something else is one worth learning on its own. Similarly, if understanding an idea is necessary to do or learn something else it matters more.

When I was doing the MIT Challenge, for instance, I think the Fourier Transform was introduced and explained separately in at least 4-5 classes, so that was a pretty big sign that it was important. Similarly, if you pick a less academic topic such as self-improvement, the terms habits, goals and motivation are going to show up again and again—best to understand these deeply if you want to make progress.

Cherish Good Ideas

If you start reading more, with the intention of really learning deep and useful things, it becomes increasingly obvious how rare good ideas actually are. I’ve written about many, but I’m quite confident I’ve never generated one myself.

Seen from this lens, the problem is not information overload but idea scarcity. When you find something truly deep and useful, explore and savor it fully, even if it requires a little more work at first.

The post Information Overload is a Fake Problem appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 20, 2020

Seven Habits that Seem Lazy (but Actually Let You Get More Done)

In 1850, French economist Claude-Frédéric Bastiat published his famous essay, “Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas” or, “What is seen and what is unseen.” In it, he argues against the “bad economist” who looks only to the initial effect of actions taken, and not their further consequences.

Bastiat uses the example of a broken shop window. To repair the window, the shop owner has to hire a glass maker. Now the glass maker has money, and can use it to buy further things. Thus, the economy has improved, has it not?

But this only notes the seen, the money spent and glass maker employed, and not the unseen, what could have been bought with the money instead. A bad economist reasons from the seen and argues that we ought to break windows to stimulate the economy. The wise economist knows that breaking things makes people worse off.

That breaking windows is counterproductive is hardly surprising. Yet, in our working lives, many of us are exactly the bad economists Bastiat warned against. We focus on being visibly productive, often subtly undermining the unseen ability to do important work.

Consider the person who stays late at the office every night, to show everyone what a “team player” he is. Except, this causes him to sleep less which makes him sluggish. He misses time spent with colleagues, who would have recommended him for projects and promotions. He never has time to think, and thus fails to think of brilliant ideas that would propel him forward. Despite his drudgery, his lack of progress only convinces him that he has failed to work hard enough.

Today, I’d like to consider Bastiat’s question as it applies to our work. What are the unseen factors that influence our productivity so that something that looks lazy actually gets results?

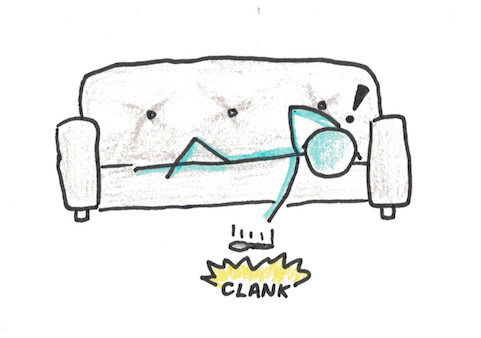

1. Actually getting enough sleep.

Productivity enthusiasts fetishize waking up early. Waking up at 7am isn’t enough. You need to wake up at 6, 5 or even 4:30 in the morning.

We all vary in our natural sleeping set-point, so early-rising might be right for some. But for many others it’s forcing us into an unnatural rhythm that naturally leads to less sleep.

Sleeping is the quintessential example of a productive activity that looks lazy. Not only does sleep consolidate memory, enhance cognition and improve your mood, but its absence is disastrous. Failing to get sufficient sleep, many of us believe we’ve “adapted” but the truth is our cognitive performance continues to decline.

Sleeping well leads to working better.

2. Taking long walks just to think.

Another consequence of prioritizing the seen over the unseen in our work is that we devalue time spent just thinking. Since its not obvious to outsiders what we’re thinking about, it’s often the case that those staring off into space or “taking a break” are seen as slackers.

In truth, long walks just to think are one of the most productive things you can do. Albert Einstein, in dreaming up the ideas behind general relativity did much of his thinking in long walks. Had he been forced to constantly publish mediocre papers instead, to give the appearance of productivity, our entire understanding of the universe would be impoverished for it.

3. Chatting with colleagues about work.

Watercooler gossip is a tell-tale sign of slacking. Except when it isn’t.

In the Enigma of Reason, researchers Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, argue that humans did not evolve to reason well about things in isolation. Our faculties of deduction, logic and insight were developed to win arguments, not to determine the truth.

What this implies, however, is that when you only think about problems on your own, it’s much harder to arrive at the correct solution. Faced with a “sounding board” you leverage your faculties of reason in the way they were designed. As a result, many insights that seem unreachable in isolation are obvious in interaction.

Of course, like all unseen productivity enhancements, this one gets a bad rap because socializing is often not about making productive breakthroughs. Still, setting up time to chat about hard problems with colleagues is rarely a waste.

4. Taking a nap.

Sleep is important. Particularly so in the night when you can enter deeper phases of sleep that enable memory consolidation.

That being so, our lives don’t always permit perfect sleep. Sometimes we’ll find ourselves struggling to stay awake during work, barely making any progress. In those cases, taking a nap should be seen as a productive hack, not wasteful sloth.

A difficulty with taking midday naps is that you oversleep and feel groggy after (not to mention wasting time). Thus, if you’re in a position where napping is an option, you can use the spoon trick. This involves napping with a spoon in your hand raised off the ground. When you slip too deeply into sleep, your muscles will relax, the spoon will drop and the clatter will wake you up.

Coffee naps, where you combine a short nap with a pre-nap coffee can also extend your wakefulness. The combination works especially well because adenosine, which makes you feel sleepy, is removed from receptors following a nap, and the freed receptors can then be “plugged” by caffeine, keeping you awake.

5. Say “No” to most opportunities and tasks.

“If you want something done, give it to a busy person.” Or, so the old saying goes. I actually think this saying conceals a hidden meaning. Busy people are those who have the hardest time saying no to those who make demands on their time. That’s why they’re busy.

I like the approach Nobel-laureate Richard Feynman took. Physics is hard work. As Feynman admits, “To do high, real good physics work you do need absolutely solid lengths of time.” His solution to avoid people interrupting him with busy-work? Tell them he’s lazy and irresponsible:

“I have invented another myth for myself—that I’m irresponsible. I tell everybody, I don’t do anything. If anybody asks me to be on a committee to take care of admissions, no, I’m irresponsible.”

Productivity doesn’t mean doing the most, but getting the most from what you have done.

6. Taking regular vacations.

“If you love what you do, every day is a vacation.” Nice in theory, lousy in practice. Even if you love your job, taking space from the work you do and having your mind elsewhere is essential to break out of the habit patterns that keep you stuck in your work.

In a discussion on travel between journalist Ezra Klein and economist Tyler Cowen, Klein remarked that he often feels exhausted from travel. Cowen responded that he is able to travel so much, because he treats travel with the seriousness most people apply to work. Instead of expecting it to be leisure, he sees it as an opportunity to expand his knowledge.

I agree with Cowen. Travel is not the only way to broaden your mind, but regularly going somewhere new—physically or mentally—is essential to avoid getting stuck in stale habits. Your routines eventually prevent you from discovering creative new solutions. Seeing and discovering new things is essential to prevent becoming inflexible in your thoughts and actions.

7. Stop doing work you hate.

It’s sometimes the most diligent and productive who end up accomplishing the least. That’s because their tolerance for drudgery prevents them from quitting on work that’s unrewarding.

Nearly all people who have accomplished something of value did work that was meaningful and enjoyable to them. No, perhaps not all the time or without effort, but grinding for years at fundamentally unsatisfying work is rarely the recipe for greatness.

To really do work you love, sometimes you need to stop doing work you hate.

These are just my suggestions. Do you have any thoughts on habits or activities that seem lazy but are actually productive? Which would you add to my list? Share your thoughts in the comments!

The post Seven Habits that Seem Lazy (but Actually Let You Get More Done) appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 13, 2020

Too Tired to Do Everything? How to Live Better Without Burning Out

Wake up at 5am. Read a book a week. Exercise every day—but make sure it’s high-intensity or it doesn’t count. Journal. Meditate. Volunteer.

Living well sounds exhausting. Maybe it’s just easier to flop down and watch Netflix?

Productivity guilt happens when you feel overwhelmed by all the things you know you “should” be doing. You don’t do them, but you still have that nagging feeling like you’re wasting time.

If you feel that guilt, I’m partly to blame. I write a lot about how to live better, and sometimes all those suggestions can start to feel more like burdens than helpful advice.

If living well sounds exhausting, what should you do about it? Should you just ignore all that advice as posturing from overachievers? Or should you beat yourself up for not reaching some hypothetical ideal?

Exposing the Hidden Contradictions of Life Advice

Part of the problem is that suggestions are almost always given on their own. So you can read about why exercise, reading, meditating or gratitude journaling are good on their own, but rarely about how they trade off against each other.

After all, you only have a certain number of hours in the day. If you’ve got a busy job, studies or family, at some point you’re simply going to run out of time.

There will always been trade-offs. If you’re meditating for an hour every day, that might cut into your gym routine. Or social life. Or reading habits. Or something else…

In practice, the fewer things you’re trying to stick to at the same time, the less there is room for conflict. If you’re only worrying about exercise, it’s probably not so hard to stick with that and simply reduce the amount of time you waste on obviously trivial things. However, when you start trying to add fifty other suggestions for living well you’ll find they start to conflict with each other.

Prioritizing these different ideas is under-discussed, perhaps because it’s messy, complicated and different people disagree. It’s easy to say “Exercise more!” It’s more controversial to say, “Exercise more and read fewer books,” yet the first does hint at the second, if only implicitly.

What If You Have Time, But You’re Just Too Tired to Do Everything?

Even if your timetable isn’t so compressed that it’s literally impossible to fit some added activity in, sometimes you’re just too tired to do all the stuff you should. As in, you know you could read a book and learn something enlightening, but randomly scrolling Twitter feels like less work.

Is it simply the case that your energy is limited, and if you put in effort in one area of your life, you’re necessarily sucking it away from another area?

This is a common view, but the research shows it’s actually a lot more complicated. Roy Baumeister helped develop the view of ego depletion, which basically means exactly this idea: exerting willpower is hard, it depends on a finite store, and when that store is depleted you succumb to temptations more easily.

Except ego depletion hasn’t stood up as well as a scientific concept after more rigorous replications. Indeed, there’s research that shows that the way you think of your own willpower affects its depletion. If you believe that you’re “energized” by doing hard things, you tend not to get depleted after exerting willpower. If there really were a physical store of energy, then your beliefs about it shouldn’t affect it. Yet they do.

More research is still needed to determine exactly what biological mechanisms go into feeling fatigued, especially when the fatigue is purely mental. However, it’s likely to be a lot more nuanced than simply burning up energy from a fuel reserve.

Two Types of Tired

In my own life, I like to contrast two different types of feeling tired when deciding whether to push forward with more effortful activities or give myself a break.

The first kind of tired is felt mostly as you’re initiating an activity. This is the feeling you have as you think about going to the gym, but it sounds hard and frustrating and maybe you should just watch another episode of The Office first.

However, once you actually get to the gym, your mood changes. Suddenly it’s not so bad and when you get home after you’re glad you went.

The second kind of fatigue persists throughout the activity itself. You’ve decided to read a hard book for fun. Except it’s not really so much fun as it is a slow torture. Your mind darts every fifteen seconds and you struggle with pushing through more than five minutes of it.

The first kind of fatigue doesn’t seem to match up with the energy metaphor much at all. In this case, you think the activity will be exhausting, but when you actually get going, it doesn’t feel so bad. The effort is all in the starting, not the doing.

This is the kind of feeling you want to push through. If you can overcome that initial hiccup to taking action, everything gets much easier.

The second kind of feeling might be something you encourage yourself to do for specific goals, but if your entire life feels that way for weeks at a time, your habits are probably unsustainable.

How to Design a Better Life (Guilt Free)

First, realize that you actually cannot do everything you should. You can’t even do everything you want to do. That’s okay, that’s just the normal constraint of living in a world where time isn’t infinite.

Therefore, it’s totally okay to acknowledge that there’s a trade-off between different pursuits. You might want to meditate an hour every day, but recognize that this will cut into your gym habit. Or you might decide that waking up early is going to cut into your social life.

I won’t decide which you ought to prioritize—that’s for you to choose. I’m not even consistent with how I make this choice. At some points in my life, I’ve prioritized my health and fitness, other times my social life, reading or some other activity. While, in theory, there’s enough time for everything, in practice there are almost always trade-offs.

Second, make a distinction between a lack of inertia and persistent exhaustion from an activity being more hassle than help. If you push yourself to the gym, but feel good after you went, that’s good. On the other hand, if you constantly feel exhausted by everything, you might be pushing yourself towards burn out.

Finally, live well for your own sake, not because somebody told you that you should. Beating yourself up because you don’t reach someone else’s idea of perfection is the best way to make yourself miserable.

The post Too Tired to Do Everything? How to Live Better Without Burning Out appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 6, 2020

Success is Stamina: To Win Means to Keep Playing

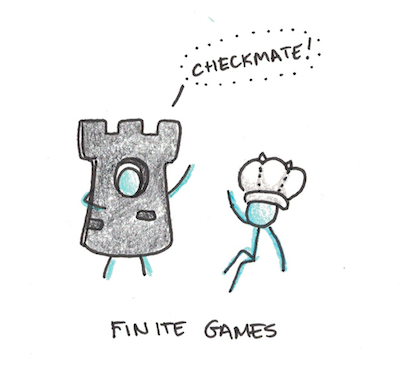

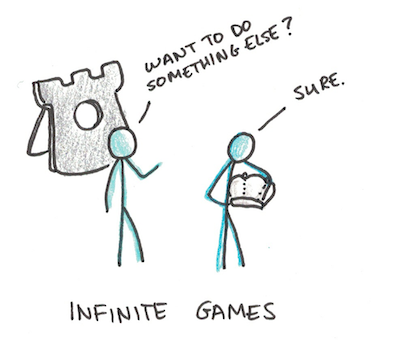

I like James Carse’s distinction between finite and infinite games. A finite game, like chess, is one that you play for awhile and when somebody wins, you stop. An infinite game, like life, is one where the goal is to be able to keep playing. To win at life means to keep living.

Most pursuits in life are infinite games. Business is an infinite game. There’s no point where you rank of all the companies, then decide for all-time which were the winners and losers. All “winning” means in business is the ability to keep playing the game.

Winning an infinite game is always a temporary state of affairs. Consider Jim Collins’ (in)famous book, Good to Great. Many of the companies he had singled out for higher performance failed to remain stellar in the years since. When you’re at the top of a hill, the only direction you can roll is down.

Rethinking Success

While all of us know that life is an infinite game, we often treat success as a process with final winners and losers. We liken it to sports, exams, battles or races—all finite games that end. This loose metaphor misses an important distinction: in life, much of success is simply being able to keep going.

I started writing when I was seventeen. I don’t think my early essays were particularly good, but if I possessed one thing it was stamina. I wrote five to ten essays a week for years, even though the possibility of making a career out of writing seemed distant at best.

In that time, I have met a lot of people who are more talented than I am. Very often they leapfrogged me and went on to greater acclaim. But, strangely, just as often, they would fizzle out. They stopped writing and went on to different things.

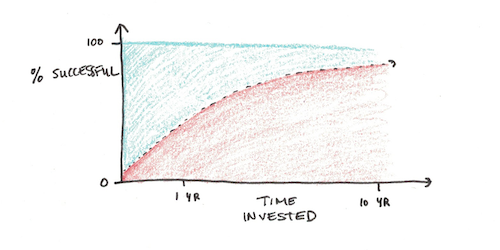

*Totally hypothetical success curve

*Totally hypothetical success curveI can’t judge and say whether their choices were wise. Counterfactuals are really hard to evaluate. Maybe quitting was the right choice for them, I don’t know.

What I can say, however, is that, at least for me, success was largely a function of stamina. When people, starting out now, ask me about how likely it is that they can succeed at starting a business, building a popular blog or writing a book, my inclination is to ask, “How long can you try?”

Patience and Idleness

Of course, the kind of patience that eventually leads to success is not the same as waiting. Simply waiting does nothing.

This is one idea that bothers me about popular notions of 10,000 hours or some other arbitrary time investment needed for success. The fact is that just investing time doesn’t do anything on its own. Even the research on deliberate practice, which inspired the 10,000 Hour Rule, doesn’t suggest that skill is simply a product of time investment. Quite the opposite, it asserts that most of our practice doesn’t count and the time we spend naively trying to improve is often wasted.

No, the kind of patience required for eventual success is an active, self-doubting kind of patience. It’s the kind that puts in enormous amounts of work, looks at that work and questions whether that was the right work to have put in, makes an adjustment and tries again.

Of course, it’s exactly this self-doubt and uncertainty which makes patience very hard. If you knew that success would come in exactly ten years if you just keep doing what you’re doing, then patience would be easy. Stamina is hard because, as with all infinite games, you don’t know how long you’ll be running for or even if you’re running in the right direction.

Build-Up and Breakthroughs

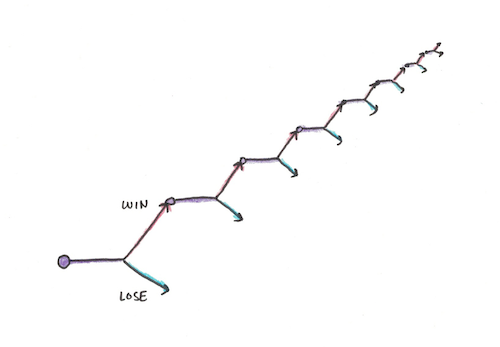

Part of the difficulty of stamina is that success tends to accrue in two different modes: build-up and breakthroughs.

Build-up is the steady accumulation of improvements. This is the stuff that’s easy to see and when patience is (relatively) easy. You see your business grow, month after month. Extrapolate that growth and eventually you’ll reach your destination. You see yourself gaining muscle at the gym, week after week. Eventually you’ll be strong.

Breakthroughs, on the other hand, are like puzzle solving. There’s a lot of effort, which does absolutely nothing, but every once in awhile there’s an insight that results in a discontinuous spurt. Think of trying to open a combination lock that you don’t know the code for—most of your attempts do nothing other than eliminate one of many possible sequences. Try the right code, however, and it opens in one pull.

In most pursuits, success is a mixture of breakthroughs and build-ups.

I remember distinctly a moment, now over a decade ago, when I was trying to grow my website. I could see that it was gaining traffic (build-up), but when I extrapolated the numbers I had so far, it was going to be decades before I was in a position where I could support myself from it.

What was missing from that extrapolation of future build-up, were the breakthroughs. Sudden improvements due to finally finding the right combination to unlock a new level of growth. When I eventually was able to support myself, it came from a single idea that finally worked. I created a monthly subscription program for study skills that proved to be popular enough to let me write full-time.

Stamina or Stubbornness?

It’s clear that, for any pursuit, an increase in your stamina will increase your success. Your health? Don’t let the oscillations in the scale dissuade you—keep exercising. Your business? Keep trying new things and stay solvent as long as possible. Your love life? Don’t let rejection or failure get you down, keep meeting new people and stay positive.

However, life rarely involves a single pursuit. We’re always, implicitly, trading one pursuit against another. Thus, even if those with greater stamina are more successful at one thing, their stubbornness may prevent them from picking a different pursuit where success comes easier.

Consider that, in many university departments, those getting PhDs have effectively zero chance of getting tenure. Stamina abounds, but many would have been happier keeping their intellectual interests a hobby and choosing a field that’s easier to build a career.

Stamina may increase the odds of success, but it also increases the costs of failure. Something you spent a few years at, decided you didn’t like and moved on is a life experience. Spending decades on a dead-end is a disaster. “Just be patient,” is not universally sound advice.

However, while dead-ends and pitfalls abound, it’s also clear that success in most pursuits requires stamina. Especially when success depends on breakthroughs, it’s often the case that one has to work hard for years on faith that everything will eventually pay off. This is difficult to do emotionally, even if the choice to persist is the correct one.

How Can You Increase Your Stamina?

Your stamina is, very often, by design. Lower your burn rate. Decrease your poverty threshold. Work on your pursuits sustainably, rather than in big bursts prone to burnout.

The key to long-distance running is pacing. If your running speed goes slightly higher than your body can effectively sustain, you’ll rapidly become too tired to go on. On the other hand, pick a speed just below that critical threshold and, with the right mindset, you can run for hours (maybe even days).

Similarly, a lot of stamina can be built into your striving directly. Simply set yourself up in a way so that sustaining effort for years is a viable option.

Other elements of stamina are mental. How can you cope with doubt? How can you be patient without becoming complacent? How can you prevent getting distracted by alternative pursuits that seem easier on the surface, but only because you haven’t realized the stamina they also require?

It’s tempting to reduce stamina down to a mantra. “Never give up,” or something like that.

Unfortunately, it’s precisely because giving up sometimes makes sense that stamina is hard. Dead-ends are everywhere and many efforts go nowhere. If you could guarantee that success would come eventually, then you’d only need to wait. But just waiting won’t get you there.

Therefore, I don’t think there are any universal slogans you can adopt that will simultaneously give you patience and release you from the emotional tension of struggling toward an uncertain goal.

The best that has worked for me, has been to ask myself whether I genuinely have better opportunities than this one. Usually the answer is no, so even if my current pursuits eventually fail, it still makes sense to continue down this path. However, even this advice only works if you correctly value your competing opportunities. If you chronically believe the grass is greener on the other side, you’ll keep hopping fences.

Another strategy I’ve found helpful is to focus on the process of pursuit itself, rather than the goal. If you can make that tolerable, even exciting, then whether you eventually reach the mountaintop you’re aiming at is less important. The people who run the farthest usually like running.

Most of all, I think it helps to recognize that life is an infinite game. If you get the opportunity to keep playing, you’ve already won.

The post Success is Stamina: To Win Means to Keep Playing appeared first on Scott H Young.