Scott H. Young's Blog, page 28

November 23, 2020

Are You Missing This Essential Foundation for a Good Life?

Recently, I shared my list of foundational practices—the basic things everyone should do to live better. Of course, my choices are personal. Your list might differ a little from mine.

Most people, however, tended to agree with my choices. Foundational practices should be obvious. If they weren’t, there would be some controversy over how useful they are.

Yet there was one practice that a lot of people admitted to not doing often. People exercised, read, tracked their spending and fenced in their vices… but when it came to this practice the most common response was, “Yeah, I really should start doing that.”

The Missing Practice

This practice was having regular conversations with people smarter than you. Or, if not smarter in all ways, then a bit ahead of you in at least one dimension of life you care about.

Perhaps this omission simply reflects my audience. I attract introverted self-improvement junkies who have no trouble reading ten books a month, but find it hard to strike up a conversation with someone new.

Despite the difficulty, the value of this practice can’t be overstated. I can see at least a few major benefits of making this a part of your routine:

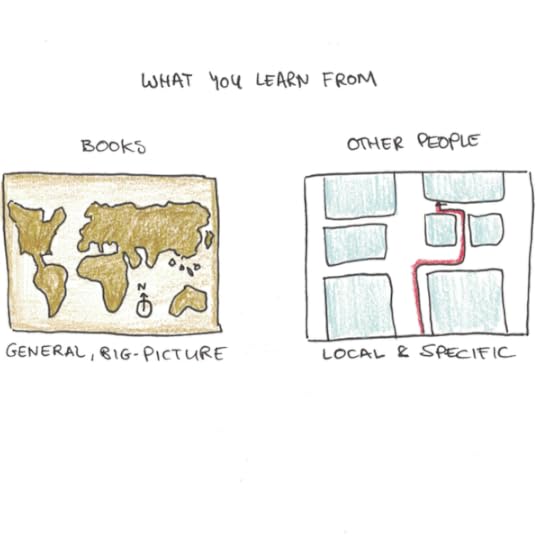

1. Books are general, conversations specific.

One person told me she reads a lot of books which fulfills a lot of the same benefits as talking to others. I agree that books can help greatly, but there are important places where these two practices don’t overlap.

The first is that books tend to offer general advice, but what you need is often highly specific. You don’t just need advice on “success” but exactly who to reach out to in your company to move your career forward. Books offer an atlas, but what you need is often a tour guide.

2. A lot of important knowledge cannot be written down.

What you learn from talking to others is deeper than what you could read from a transcript of the conversation. We know that human beings are uniquely social learners. And we often learn successful practices even when nobody understands how they work.

In one experiment, for instance, researchers had participants design a simple machine. Learning from the trial-and-error designs of others, they quickly made progress. Yet when asked for the theory of why their design worked, most were flat-out wrong. When you interact with people directly (or via Zoom) you not only get methods and theories, but you subtly absorb attitudes, practices and beliefs that impact your results.

3. Access matters (even if it can be overrated).

It’s a cliche to say “It’s not what you know, but who you know.” Obviously, for many professions, this is simply untrue. I’d rather have the surgeon who knows medicine, not just the guy who met a ton of people at his fraternity.

But there is truth in the idea. Opportunities are realized through other people. Even if you knew everything there was to know, you’d still benefit from talking to people since those connections would form the conduits for new possibilities.

An Introvert’s Guide to Having More (and Better) Conversations

For some people this advice is not only obvious, it’s unnecessary. If you’re more extroverted, you probably already talk to lots of people and have many friends who excel in various dimensions.

However, given the number of responses I got from readers, this is clearly a weakness for many. Thus, I think it makes sense to look at what concrete strategies you ought to use to make it easier (especially if meeting people sounds daunting).

Side note: As I write this article, the grips of the pandemic have made meeting people harder for everyone, so it’s not just introverts who are struggling!

Thus, to ensure success with the practice of having one conversation per week with somebody smart, there are a few different tactics to make it work:

1. Schedule calls with people you already know.

The easiest win is simply to be better about following up with people you’ve already met.

I have a friend who is remarkably good at this. He’s not the most extroverted person, nor is he the type that is always making himself the center of attention. However, he does one thing better than almost anyone else I know—he follows up.

That is, when he does meet someone, he gets their contact information and shoots them a friendly email or text a week or so later. If they hit it off, he makes an effort to have a call or coffee.

In the long run, even if he meets the same number of new people, he ends up having far more conversations. He doesn’t need to be pushy—if he messages and doesn’t get a reply, or the person doesn’t seem interested to meet up, he drops it. But the fact is, most people are passive, so even if they would be interested in conversing, they’ll rarely initiate.

2. Ask for introductions.

The next easiest step is to ask to be introduced to people. This is particularly helpful if you’ve already identified someone you’d like to learn from. So if you’re trying to learn more about business, asking if your friends know any entrepreneurs is a good step.

When Vat and I did our no-English language experiment in China, we made heavy use of this. Starting from a few local tutors, we were able to build a network of friends relatively quickly (despite only speaking broken Mandarin) because we asked for introductions. Most people were happy to help and this strategy worked far better than trying to strike up conversations with random people on the street.

3. Reach out to like-minded people.

A final suggestion is that if you want to talk to someone, simply send them an email. It’s amazing to me how often this works. Many of my closest friendships started out this way.

In this way, having a public blog, Medium account or Twitter profile with small amount of content expressing your thoughts and ideas is helpful. This blog has helped me immensely with meeting people simply because if I want to get to know someone, they can quickly check me out and see what I think about things.

However, I also know many people with no public works who have made great use of this strategy, so don’t let being unknown stop you from reaching out.

The Real Reason People Don’t Do This

I started this article by noting that this practice, more than exercise, reading or sleep, tended to be neglected. This is strange because it’s also one of the easier practices. Exercising every weekday requires several hours. Having a conversation each week, including the time to reach out, requires less than an hour.

The obvious reason people don’t do this is that they fear rejection. What if I email someone and they don’t reply? What if I don’t know who to contact?

The easiest way to warm-up, then, is to pick people where you won’t get rejected. People you already know, or ask for introductions directly so you’re not cold-emailing people.

But the real practice is to get comfortable with not getting a response to your outreach efforts. The imagined fear is usually that the person will be angry at your presumption, or that you’ll be humiliated with a scornful reply. This almost never happens. Instead, the most common rejection is simply no reply at all.

Not getting a reply typically means nothing. The person hasn’t given much thought to your request and it doesn’t damage your reputation. Of course, don’t spam people. Don’t send multiple unsolicited requests in a row or endless emails to “follow up” when it’s clear the person isn’t interested.

I understand the trepidation about doing this because I’m hardwired the same way. I also resist doing this, but that’s exactly why I need to push myself to do it more. If you spend all day talking to people, reaching out to an additional person has diminishing benefit. But if you never do this, doing it a little bit can have enormous returns for your life. Thus, the practice is all the more valuable, the harder you find it is to do.

The post Are You Missing This Essential Foundation for a Good Life? appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 16, 2020

Live Chat on the Science of Motivation (and Q&A)

This week I’m going to do a live conversation discussing some of the findings in my recently published Complete Guide to Motivation. The conversation is going to be held at 2pm Pacific Time on Friday, November 20th.

The presentation will be free to attend. It’s not a pitch or warm-up to any kind of product (the guide I’m discussing is also free). I just thought it might be fun to interact with some of you in a live setting.

I’ll talk for about 20-30 minutes, after which we’ll leave the rest of hour for questions. If you’ve wanted to ask me a question about anything, this is a good opportunity to chat.

I’m using YouTube Live for this. All you need to do is follow the link at the scheduled time. I hope to talk to you there!

Any topics or questions you’d like me to address? If you write yours in advance here, I’ll be more able to consider it and give a thoughtful reply on Friday!

The post Live Chat on the Science of Motivation (and Q&A) appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 9, 2020

The Paradox of Effort

Where does the motivation come from to improve your life? At first glance, this seems like a strange question: why wouldn’t you automatically want things to be better? But the good life is hard work, so we often fail to do the things we know would make our lives better.

Cal Newport told me that, while in grad school, he noticed a lot of people became much better students after they had kids. This is paradoxical because children are time-consuming, and thus, it ought to be much harder to succeed academically.

I noticed something similar in myself, when I decided I wanted to run my own business. There were a lot of spillover benefits to other areas of my life, even though they weren’t related to entrepreneurship. I started reading books, exercising regularly and eating healthier, for instance.

The difficulty of the new challenge forces you to take things seriously. Cal’s observation was that, with fearsome time constraints, procrastinating is out of the question. Taking studying seriously pushes you to do better than you might have, absent those constraints. In my case, becoming my own boss was a difficult enough goal that it forced me to build better habits throughout my life.

What’s Your Core Motivator?

It goes without saying that these examples aren’t universal. Plenty of new parents find it harder to succeed in their work and studies, not easier. A lot of people start businesses and don’t find themselves getting into shape.

But the fact that these examples exist at all is interesting. If everyone were rational, then adding extra challenges could only make life harder. The fact that there are counterexamples points to an intriguing feature of our motivational hardwiring.

Much of self-improvement has an activation cost. It’s harder to exercise regularly, read books and work on yourself than to binge watch Netflix all day. But, once you’re already doing those things, it’s easier to keep doing them.

The problem is that a lot of the things we should do to live well just aren’t motivating enough on their own. You know you should do them, but they often slip through the cracks.

However, when you do have a goal that deeply motivates you—becoming your own boss, getting through grad school to build a good life for your family—then that enthusiasm often helps overcome the activation costs in other areas of life. If you’re going to be productive all day and organized, you might as well also start flossing.

Finding the One Reason to Do Everything Else

You have the ability to put in far more effort into things than you normally do. The reason you don’t is that, most of the time, a full effort isn’t necessary.

We think that a full effort will be draining, that we ought to save our energy for when we really need it. Yet, more often than not, the opposite is the case. When we really use our full effort toward a central concern that matters deeply to us, we feel more energized—not less.

The paradox is that life is often easiest when it is hardest. When you’re working on a pursuit that may fail if you don’t take it seriously, you find the energy to take it seriously. And, in doing so, you find the other nagging things in life that needed effort weren’t so hard either.

The key is to find the one thing that will necessitate all the rest.

The post The Paradox of Effort appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 26, 2020

Cal Newport on The Narrow Path to Success, Fatherhood and Challenging Conventional Wisdom

Our podcast has now reached 100 episodes! To mark the occasion, I recorded a conversation with my good friend, Cal Newport, author of the bestsellers Deep Work, Digital Minimalism and So Good They Can’t Ignore You.

·

Some of my favorite parts:

5:45 – What are the biggest misconceptions about becoming an author or academic?

11:45 – What aspiring authors need to know, and how this applies to all careers.

17:00 – The change in Disney movies, what this says about our culture, and why it leads to dissatisfaction.

28:00 – The difference between potential and results (and how this shifts as you age).

35:00 – Unexpected life changes following fatherhood

37:20 – Cal Newport’s best productivity advice.

41:20 – Why Cal doesn’t get invited to give commencement speeches anymore…

50:40 – The intriguing book idea Cal had (but never wrote).

Did You Know About the Podcast?

Quietly, we’ve been releasing new podcast episodes, twice a week, for several months. Our episodes are a mix of shorter episodes I cover from the blog, interviews like this one and discussions on some of my favorite books.

If you enjoy listening to podcasts and want a twice-weekly dose of ideas and inspiration, you can find me on any of the podcasting apps:

Apple podcasts

Google podcasts

Spotify

Stitcher

Overcast

Rate my podcast

Would you like to see more episodes like this? Rating the podcast helps other people find out about it, and helps us host more conversations like this one. I’d love your support to help the podcast grow!

The post Cal Newport on The Narrow Path to Success, Fatherhood and Challenging Conventional Wisdom appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 18, 2020

Learning My Wife’s Native Language – One Month Update (Video)

A month ago, I started learning my wife’s native language, Macedonian. To do that, we’re only speaking Macedonian at home with each other.

Here’s a brief video with subtitles sharing the progress I’ve made so far:

I also recorded a longer lesson with my tutor, Jovan, to show what a typical lesson looks like for me right now (no subtitles):

How Did the Project Go?

Overall I’m quite satisfied with the progress of the project. There’s still more to go—we want to continue the No-English Rule at home for another two months at least. But, given that I continued to work full-time during the project, I’m pleased with the outcome after one month.

In addition to the No English Rule at home, I did a few other things that helped:

Tutoring. Near daily iTalki.com lessons.

Flashcards. My Anki deck at the end of the month had around ~1000 words.

Textbook. I worked on Македонски Јазик, completing 11/16 lessons.

My total time investment in studying (ignoring the daily life conversations with my wife) is difficult to know exactly, as I didn’t study with fixed hours as I have with other projects. Instead, I studied in gaps of time as they appeared in my schedule. Still, I would estimate I spent:

Roughly 30 minutes per day on textbook practice. Perhaps, 15-20 hours total.

I know from iTalki.com that I did 20 one-hour lessons.

Anki tells me I spent 17 hours on flashcards, but this doesn’t include the time to make flashcards. Conservatively, I think ~25 hours would be an over-estimate.

With these estimates, I can say that my overall studying time this month was no more than 65 hours, or ~2 hours per day. Certainly a large time investment if you’re working full-time and have a baby at home, but not anything unattainable for someone suitably dedicated.

Of course, what this omits are the countless hours I spent actually using Macedonian at home in daily life. That’s why I’m such a fan of this approach to language learning, because it allows a disproportionate amount of learning to occur for the actual amount of time you set aside to study on your calendar.

My Plans for Future Progress

We plan on continuing the No English Rule at home for the next two months. I’d like to finish my textbook and continue tutoring whenever possible, but it may end up being less than the first month as work gets busier.

In terms of my ability itself, I want to clean up my spoken language a lot more. I make a lot of basic mistakes with gender, conjugation or simply just cleanly pronouncing some words. That’s acceptable in the beginning, but if I ignore it too long it can create problems later.

I think writing more might be a helpful drill, as would focusing on simple sentence translations. Writing, since you can go slow and edit yourself more easily than with speech. Translations help because you only have to think of how to say something simple, rather than simply what you want to say.

Once my textbook is finished, I’d also like to transition into reading and listening to more native-level media. That’s a bit hard now, but input becomes increasingly important once you’re trying to go beyond basic linguistic abilities and trying to get into a comfortably intermediate position with more specialized vocabulary.

Still, I’m more than happy with where I ended up after one month. It’s easy to obsess over what you still need to do and neglect how far you’ve come. I’ve done more in the past month than in the past five and half years that I’ve been with my wife, and it will now be much easier to progress in the future.

If anyone else wants to attempt a similar project with their spouse, partner, friend or roommate, let me know in the comments. Learning a new language is a great experience. It’s just up to you to take the leap!

The post Learning My Wife’s Native Language – One Month Update (Video) appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 11, 2020

The Hard Way is the Easy Way

In my previous essay, I argued that much of success boils down to a simple maxim: do the real thing and stop doing fake alternatives.

Always start by asking yourself: “How would I do this, if doing it well were all that mattered?”

Now, you might object: You don’t have enough time. You have a job, kids and responsibilities. Doing it well sounds too daunting.

This is okay. The point of this thought experiment isn’t to deny that obstacles exist. Rather, it’s to start with the best plan and make accommodations as needed. What results is usually much closer to the ideal than if you simply start with something that feels easy enough.

How Would You Do It, If Doing It Well Were All That Mattered?

Let’s look at some examples:

You want to learn a language. The best plan is full immersion. You can’t do this completely though, so you make some exceptions for work, friends or family members. In the end, you only spend 60% of your conversation time speaking the new language.

In contrast, imagine you start by asking what’s something easy you can do? Now you end up downloading an app, listening to a podcast or telling yourself you’ll speak it “as much as you can.” The result? Maybe 1% of your conversation time is in the language. Maybe you never use it to communicate at all.

Say you want to start a business. The best plan is to build a prototype immediately of your intended product. You start interviewing prospective clients, getting preorders or contact information. But you can’t do this perfectly—you can’t quit your job yet and you can’t get financing.

The resulting path, however imperfect, is still a hell of a lot better than randomly reading business books or printing business cards or whatever convenient activity would have replaced it.

Maybe you want to get in shape. You figure the ideal path is to plan meals and stick to a precise workout schedule. You have to modify this to fit your life, but it gets you further than just buying a standing desk or telling yourself you really should try to exercise more often.

The Paradox of Difficulty

A pattern in my own life, and one you may have seen as well, is that the hardest things end up becoming the easiest, once you’ve fully committed to them.

Most pursuits have some unavoidable effort. You can either choose to commit that effort, or find ways to pretend it doesn’t exist.

If you choose to commit, you make the pursuit a priority. You put it first in your calendar. You expect frustration, setbacks and obstacles. You’ve made yourself stronger, instead of trying to avoid lifting the weight.

Paradoxically, it’s those who ignore the investment needed that experience the highest costs. It’s hard to hit a target when you’re aiming out of the corner of your eye. Difficulties arise precisely when you expect things to be easy.

How to Commit to the Hard Way

The way forward is simple. It just isn’t easy:

1. Begin with what would work best.

Start with what would work best. Hold the buts and whatabouts for later. Merely asking what the ideal strategy would be doesn’t yet commit you to it. But it forces you to recognize the effort inherent in the path ahead.

Focus on what you’d be doing, not how much. The “what” turns your attention to the real thing. “How much” matters too, but it should come after. While intensity can be scaled, the real thing doesn’t have easy substitutes.

2. Make the best possible to attain.

Starting with what would work, you now ask how you could make it possible.

Maybe the real thing is inaccessible. You want to learn a language, but you’re stuck at home. You want to work in a real firm, but they won’t hire you. You want access to the training ground, but it’s off-limits.

Now is the time for substitutions. Approximating the real thing is tricky, but it’s far better than efforts that don’t even strive for verisimilitude.

You can’t travel, but you aim for immersion at home. You can’t work in the real office, but you train on the tools they use. The training ground is off-limits, so you build your own in your backyard.

3. Turn the hard way into the easy way.

Now, and not a moment sooner, is the time for engineering ease into your efforts.

The timing is critical. Starting with what’s easy, you’ll be tempted to substitute something convenient for something that works. Once you know what needs to be done, however, do everything you can to make it easier to execute.

Smooth friction. Ask for help. Cultivate good habits, systems and routines. Throw every hack, trick or tactic you have at the problem to make the path a little less treacherous.

If You’re Not Willing to Do it Well, Why Be Willing to Do It at All?

The hard way forces a choice: are you willing to invest the effort required to do it right?

As with any real choice, sometimes the answer is no. The cost is too high, other obligations take precedence or you simply don’t care enough. No is always a valid answer. Better to say it now, than let it rot away your resolve over time.

But if your answer is yes, then you know the path. All that’s left is to walk it.

The post The Hard Way is the Easy Way appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 8, 2020

Macedonian Project (Week Three Update)

Nearly a month ago, I decided to embark on a project to learn my wife’s native language, Macedonian. To do this, we’re not speaking English to each other at home. This is a brief update on how that project is going in the third week.

Last week I had mentioned some hiccups. I found juggling the immersion plus my full-time work (and having a new baby) to be more tiring in the second week of the project.

This week, I’m happy to say, has been a lot easier. My conversational range has expanded immensely, beyond just transactional communication. I’m still not weaned off of needing dictionary look-ups for harder topics, but I don’t expect that to come until later.

Dealing with Exhaustion in Ultralearning Projects

The difference between the second and third week illustrates a common theme I’ve found in my projects: things often feel overwhelming, but only temporarily so. Slowing down is better than stopping because the feelings rarely last. Walk a few laps if you have to, but don’t exit the race.

A major difference between this project and previous ones is that I’ve continued working full-time. This has made studying somewhat less consistent, as I’m trying to squeeze it in spare moments unoccupied by work, rather than putting it first in my schedule.

The nice thing about an immersion project, however, is that a lot of the learning takes place in the background of other activities. Eating breakfast with my wife isn’t usually a substitute for studying, but if you’re practicing a new language it can be. If I can stick to the No English Rule, I’m happy to have a more sporadic studying schedule.

At-Home vs Travel Vocabulary

One amusing side-effect of the at-home immersion has been that the order and frequency of words I’ve learned has differed from other languages. Although the core of the language stays the same, my vocabulary leans a lot more on domestic situations, and much less on things outside.

Consider that I still don’t know the Macedonian word for suitcase (which I knew on Day 1 in Spain), but I know the word for diaper (something I’m not sure I ever learned in Spanish). This is a silly example, but it shows how much environment determines what you eventually learn.

Despite obvious gaps, I’m happy that my Macedonian progress hasn’t been like my progress in Spanish or Chinese. I’ve learned what I’ve needed to first, and only learned less practical things later. What’s been practical itself has changed with each language, so my ability in each is unique, rather than merely falling on a line between zero and fluent.

Is Fluency the Wrong Goal?

This experience with Macedonian has made me think more about whether fluency was ever a good goal to have in the first place. It certainly is the most popular goal among language learners, but I hesitate to think that it’s ill-defined.

It’s surprising for some people, for instance, that you can get to a conversational level much, much earlier than you can get to a level where your proficiency is equal to a native. I can usually have conversations on nearly any topic long before I can comfortably watch a movie without subtitles.

To some, fluency is just this—being able to speak without undue hesitation and error. If you can have a conversation without it being a strain for the other party, you’re fluent. But if fluency is seen as the final stage of learning a language, this obviously cannot be right.

Maybe it’s more productive, once conversational stages have been reached, to think of linguistic skills as diverging into more numerous subskills—being able to give lectures, read novels, watch movies, understand internet memes and so on. Thus the goal of “fluency”, seen as an endpoint, necessarily breaks down to, “I want to get good at giving speeches,” or, “I want to be able to appreciate poetry.”

I think the illusion is that because the same words and grammar can appear, in theory, in any of these situations, that there is something proper to be called “fluency” irrespective of the situation it is being used in. Everything I’ve learned on transfer, however, makes me suspicious of this.

My goal with Macedonian is decidedly more modest than I have with Mandarin Chinese. If conversations at home are easy, I’ll consider it a win. I think this framing makes it more achievable than having the expectation that anything less than perfection in all communicative domains is still not good enough.

The post Macedonian Project (Week Three Update) appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 4, 2020

Do the Real Thing

Success largely boils down to a simple distinction. It’s glaringly obvious once you see it, but also easy to find ingenious ways of ignoring it: do the real thing and stop doing fake alternatives.

Consider one person who wrote to me saying she turned down a job working in French. She didn’t feel her French was good enough yet. So instead, she planned to listen to podcasts at home every day until she was ready.

You know what would have helped her get good at French? Working at the job in French.

Working at a job in the language she wanted to speak was the real thing for her. Listening to podcasts at home to prepare was the fake alternative she chose instead.

Or consider another person I spoke with who wanted to get better at writing music. He had come up with a complex analysis project. He was going to do a deep dive into past hits, figuring out what made them great. In all this complexity he ignored the obvious, real thing he should be doing: writing more songs. When I asked how many he had written so far, he said it was just three.

Business owners who spend more time printing business cards than finding clients. Students who create elaborate multicolored folders for their classes instead of sitting down and studying. People trying to get in shape who buy fancy workout gear instead of exercising. Pretend activity instead of the real thing.

I’m not immune to this tendency. If anything, I succumb to it more often than most. I’ve spent months dreaming up elaborate projects that precisely avoid doing the real work. Creativity and intelligence can be an enemy here, as they allow ever more elaborate rationalizations into doing fake work.

Why the Real Thing Matters

The fact that a direct strike on a problem often works better than an oblique attack isn’t surprising. But the problem is even more acute than most people would expect.

There’s an enormous literature about the narrowness of acquired skills. Learn to do X, and then switch to doing Y, and you often take a huge performance hit even if X and Y are superficially similar.

This applies most obviously to formal education. In countless studies, students are found to not be able to perform on tasks that their classes should have prepared them for. Studying economics then not being able to do better on questions of economic reasoning. Taking one psychology class and not having it help when taking a later one. Physics students failing to solve problems that differ slightly from those taught in class.

But the truth is probably deeper than just a failure of our education system. One researcher I spoke with mentioned how this applies even to very basic skills. With practice, for instance, you can get better at discriminating vertical lines. But switch the test to horizontal lines and the benefit of training goes away.

This specificity of training means fake alternatives often accomplish a lot less than you’d naively expect.

The Strategy for Success Looks Obvious

When you examine case studies of people who have had major accomplishments, you expect there to be some trick or shortcut. Some amazing technique they used that others weren’t clever enough to recognize.

More often, however, the strategy used is dead simple: doing the real thing.

Tristan de Montebello went from near-zero speaking experience to a finalist for the World Championship of Public Speaking in seven months. How? By getting on stage and speaking constantly, sometimes as often as twice in a day.

I found many other examples when researching my book:

Eric Barone, who went on to sell millions of copies of his game, overcame his struggles at creating art by making and remaking the art assets for his game dozens of times.

Vat Jaiswal, was struggling to land work as a new architect, until he committed himself to mastering the software and style practiced at actual firms.

Countless polyglots show that being able to speak a language depends, critically, on spending a lot of time speaking it. Playing with apps alone doesn’t count.

Why then, if the way forward is so straight, do we insist on taking detours?

The Real Thing is Hard

Real things require real difficulty. Fake stuff never does.

This doesn’t mean fake work is effortless. Instead, pretend activity always has just enough difficulty to allow you to trick yourself into thinking you’re doing something that matters. But, conveniently, it avoids any of the truly difficult things the real situation would create.

Consider the examples above. My friend’s music analysis project is definitely a lot of work. However, it conveniently misses the real frustration and challenge of struggling to write your own songs. It requires effort, but always in a way that feels doable and safe. Listening to language learning podcasts for hours is mildly strenuous. She can feel like she’s doing “something” even though it probably won’t prepare her for working in French.

Real things have risk. They have the possibility of failure. They have frustration. They force you to confront the possibility that maybe you just aren’t good enough.

Fake activity is great for making yourself feel better, but lousy for actual results.

Rules for Doing the Real Thing

I can think of a few guidelines to try to crystallize the attitude I want to encourage:

1. Nothing is often better than something.

We’re trained to think that something is better than nothing. This is true, but only if it’s a real something. Fake somethings not only fail to create progress, they numb you to the possibility of real striving.

Fill your days with enough fake activity, and you get into the situation where you fail to make meaningful progress on any of your goals, but still feel exhausted at the end of the day.

Doing nothing, in contrast, is restorative. It fosters the urge to do something, rather than draining it away.

2. The hard way is the easy way.

The starting point for any new effort should be to ask yourself, “How would I do this, if doing it well were all that mattered?”

Difficulty is paradoxical. The hardest things often become the easiest once we’re fully committed to them. What’s difficult is the commitment, not the action; the word, not the deed.

Taking the real thing as your starting point, the deviations you must take to overcome obstacles tend to be minor. Taking a fake and convenient substitute as the starting point, and you can often never work back to the original thing that mattered.

3. If you’re not sure what the real thing is, just ask.

Those who have been there before know what the real path is. If you ask them, they can instantly spot the difference between strategies that attack the heart of the problem and fanciful projects that lead nowhere.

In case it’s unclear what you should be working on the solution is simple: ask. Find someone who has been there before. Tell them your plan and ask them if they think it’s direct enough. Forums, Quora, LinkedIn and many other places exist where you can ask the question, so saying you don’t know anyone who has done it before is no longer an excuse.

A Meaningful Life Depends on Doing Real Things

There’s a feeling that goes along with real work. It’s not always positive. It often has fear, frustration or the sense that maybe you’ve bit off more than you can chew.

But doing the real thing matters. Days wasted on fake activity may keep you busy, but they never seem to go anywhere. A life spent on real work may not always be the easiest or most entertaining, but it’s the one that adds up in the end.

The post Do the Real Thing appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 1, 2020

Macedonian Project (Week Two Update)

Two weeks ago I began a new project to learn my wife’s native language, Macedonian. To do that, we’ve been avoiding speaking English at home, to mimic the approach I used previously with my language learning trip.

So far the project has been going quite well. I’m already pretty comfortable with the functional day-to-day communication we need, and I’m slowly shifting into deeper conversations.

Early Bumps in the Road

There have been some challenges, however. One evening this week we decided to take a pause for a couple hours. Taken frequently, breaking like this can halt the project, but I think flexibility is necessary. Even Vat and I had occasional breakdown moments later in the trip (particularly in Korea).

I think having the No English Rule in the background is more successful even if you can’t be perfect with it than the usual alternative which is to speak as much as you can (which ends up being not so much).

One major difference between this project and my previous one is that when Vat and I were in the early phases of learning a language and non-stop speaking to each other was hard/tiring, we could simply withdraw for awhile. That’s not an option for me with my wife and baby, so there’s been a bit more pressure to get to a decently level quickly.

Future Plans

Initially I had wanted to commit only to one month of the immersion at home. This wasn’t out of a belief that one month would be sufficient to learn the language, but simply that I didn’t want to commit to too long a time period in the beginning.

Now, however, I’m leaning towards extending the project another month or two. I’m realizing how my initial timeframe had put pressure on me to study a lot, while also having to keep up with my normal work. Adding time at the end will ease off the pressure a little bit without changing the overall strategy for learning that’s worked well for me in the past.

This, however, points to one of the great advantages of learning a language from home–you aren’t going to be forced to leave the country!

Learning while traveling always requires that there be certain time limits that you have to learn within. Even if you continue after your trip, the original immersion environment you had gotten used to abroad will change. If you’re doing immersion at home, however, it’s easier to learn over a longer period of time, especially once you get yourself established in real conversations.

The post Macedonian Project (Week Two Update) appeared first on Scott H Young.

April 27, 2020

7 Rules for Staying Productive Long-Term

Easily the best habit I’ve ever started was to use a productivity system. The idea is simple: organizing all the stuff you need to do (and how you’re going to do it) prevents a lot of internal struggle to get things done.

There’s a ton of systems out there. Some are elaborate, like Getting Things Done. Others are dead-simple, such as simply using a prioritized daily to-do list. Some require software. Many you can do with just pen and paper.

Being successful with a system long-term is hard. Here are just a few common problems:

You have no idea which system to pick, or when you do pick something you constantly second-guess yourself that you’re “doing it right.”

You get a burst of enthusiasm each time you try it, are productive for about two weeks, then you start to slack off and eventually abandon it.

The system never seems to “fit right” for your life, yet you’re convinced the problem is that you don’t know how to work within it.

The system you’ve chosen feels like a slowly constricting prison you’ve made for yourself, choking off your will to do meaningful work and turning you into a robot.

These problems can be avoided, but it takes a little thinking about what the point of having a system is and what it can and cannot do for you.

Why Use a System at All?

Ultimately, everybody has a system for productivity. There are really only three different kinds:

The system of other people. You simply respond to the pressures put on you by colleagues, clients, bosses or family members. Big deadline tomorrow? I guess you’re working late on it.

The system of feelings and moods. Feeling creative today? You might get a lot of work done. Does that thing that seemed interesting before now seem dull? I guess you’re not working on it. At its best, this can be fun and spontaneous. At its worst it can be soul-crushing to see you never make more than fleeting progress on anything with an ounce of frustration.

A system of your own design. In this case, you create guidelines for yourself that structure your efforts. Moods and outside pressures still matter, but they’re no longer the only guiding factor about what to work on, how much and how often.

Building the habit of a productivity system is about self-consciously creating a buffer between you and temporary emotions or external agents. You still need to respond to deadlines and listen to your emotions, but those aren’t the only things you heed when planning your day.

If your system is going to be liberating rather than suffocating, however, you need to follow a few guidelines:

Rule #1 – Your system needs to fit your work (not the other way around).

Any system is designed using certain assumptions about your work. If those assumptions are wrong, the system may backfire.

Take Weekly/Daily Goals, the system I use most often. The idea is that you have two lists, a weekly to-do list and a daily to-do list. The latter is intended to be fixed—you decide what to work on that day and hold it constant, even if you finish early.

This system works well when you have a bunch of concrete tasks you need to finish that you might procrastinate on, but if you just sat down and did them all in a burst of focus you could probably get them done easily. The goal here is to use the potential reward of a workday finished early to get things done in an effective manner.

This system doesn’t work as well if your tasks are ambiguous and open-ended. It struggles more when your day is mostly meetings occurring at fixed times on your calendar. If your daily goals list just contains one task, “Work on X.” then it isn’t even functioning as a productivity system at all.

Therefore, before you get started with a system, it’s important to ask what the assumptions are that underpin it. What does your work need to look like for this to be effective?

Rule #2 – The system should counterbalance your worst tendencies.

The guiding philosophy behind Getting Things Done is that, without writing down what needs doing, we’re liable to forget. Although the system aims at more than this, the key tendency it’s trying to counteract is simply forgetting what you need to do.

Fixed-schedule productivity counterbalances the tendency to constantly work overtime, having your office hours bleed into your home life. You’re answering emails at midnight, but at the same time, you’re exhausted in the evening and not as sharp when at work.

Maintaining deep work hours suggests the problem is mostly distraction, particularly from tasks that feel like work but aren’t your main source of value.

The Most Important Task method works when you have a few hard tasks that you need to prioritze. It assumes you’ll end up working on convenient, easy tasks, rather than those that really matter. Quadrant systems that focus on important tasks over merely urgent ones, are another tool for prioritizing.

Breaking your day into Pomodoro chunks assumes the problem is that the work feels too large to get started, so you procrastinate. Small chunks with mandatory breaks focus your attention on the next mile marker and not the entire marathon.

These tendencies need not be mutually exclusive. You could, for instance, combine deep work hours with Pomodoro chunks or the Most Important Task method. What matters is that these systems are balancing the problems you’re actually facing. A sales person investing in deep work hours probably doesn’t make sense.

Rule #3 – The system needs a way of dealing with exceptions.

Every system, no matter how complicated, will create situations where it no longer makes sense to follow the guidelines it sets.

What’s needed, then, is a way of handling exceptions to the rules without making so many ad-hoc adjustments that the original system is rendered meaningless. Unfortunately, there’s no way to create a list of such meta-rules since if there were, they could simply be included into the original system.

For instance—let’s say you’re a writer. You have a bunch of tasks on your plate for the day, but all of a sudden you get a really good idea for an essay. You should probably start writing now or you’ll lose your train of thought. What should you do?

There’s no “correct” answer to this situation. For some people, getting enough good ideas for writing may be the major problem in their work. For them, it makes sense to put on hold lower priority work to start writing as soon as inspiration calls. For others, they may waste days chasing ideas rather than doing the boring stuff that needs doing.

In this sense, the “correct” answer is to develop self-awareness. Does this exception to the basic rules I’ve set for myself buffer against an unproductive tendency or support it? If this exception is made into a new rule, would it strengthen or defeat the system I’m trying to create?

This may sound finicky, but I’d argue that true success with systems involves making numerous such slight exceptions which become a part of the system themselves. To use a system means not only to follow its basic guidelines, but develop a skill of handling exceptions to the system that make it more useful, not less.

Rule #4 – A good productivity system shouldn’t “feel” productive.

Okay, this one requires some explanation. In short, the problem with aiming to “feel” productive rather than “being” productive is twofold:

Feelings are defined by relative contrast, not absolute measurement. You feel productive when you’re getting more work done than normal. But if you’re successful with a productivity habit, what’s “normal” should shift. Relying on feeling productive then creates an inescapable treadmill where if you’re not constantly doing better than what feels normal, you feel like a failure.

Feeling of productivity is often tied to a feeling of exertion. This leads to expending a lot of effort in the beginning with a new system, getting a lot done, and then being disappointed when you can’t sustain that.

A good productivity system should, when working properly, feel like nothing at all. It should just be an invisible part of your routine. If it is conspicuous, it’s probably not a habit yet, or it’s creating friction with parts of your life in ways that it shouldn’t.

If you don’t feel more productive, how do you judge your productivity? The obvious answer is that you should get more work done with the system than without it. But even this can be misleading because in the short-term it’s always possible to just work really hard and burn yourself out.

The better, long-term answer for evaluating your system ought to be that when you look back at the last quarter, year or decade with the system, you’ve been making a lot of meaningful accomplishments. If this is happening, then how the system feels on a weekly or daily level is totally irrelevant.

Rule #5 – If your work changes, your system should too.

For some, work will be consistent enough to not need major changes. You simply stick to the same system and you’ll get the results you want.

For me, I’ve found that as what I’m trying to do changes dramatically, I often need very different approaches to work on things:

In college, I often relied on Weekly/Daily Goals. My work was mostly a set of fairly concrete and predictable tasks that needed to be finished to stay on top of things.

During the MIT Challenge, the tasks themselves were larger and more ambiguous. My daily goals would have looked like, “Work on class problems all day.” Setting fixed working hours made more sense here, so I could focus when I needed to, but still give myself time to relax.

During the Year Without English, I had core tasks I set hours for, just as with the MIT Challenge. But I also had dedicated habits for doing small tasks like flashcards or listening to podcasts outside of my normal working rhythms. This helped me capture spare moments in the day.

When writing my book, deep work hours were essential. I still had other work, so I kept to-do lists for those. But setting aside the entire morning for research and writing meant I could get a lot done. Putting this first also kept me from procrastinating by using my other work as an excuse to keep from doing hard research/writing.

When I had to promote my book, my daily schedule looked like Swiss cheese, with up to five podcasts per day. A calendar-driven approach, where I scheduled my tasks made more sense here otherwise it would be hard to decide when was the best time to work on things.

Some features of my system rarely change. I almost always have a calendar and daily to-do list, for instance. But adjusting to a new system when I have different types of projects has been more successful for me than stubbornly trying to fit everything into a single system.

Rule #6 – Always measure against your baseline (not somebody else’s).

If you’re ever evaluating a productivity system, the right measurement to make is “am I getting more done than I was a week/month/year ago?” If you’re, instead, asking yourself, “how close am I to being perfectly productive?” or worse, “how productive am I compared to so-and-so?” you’re going to have a bad time.

The tyranny of ideal productivity is a major problem. I’ve worked with students in my courses whom set up a project successfully and were making consistent progress towards it. When I asked them how they’re doing, however, they complained that they still didn’t think they’re productive enough.

But how much is enough?

There’s certainly being insufficiently productive for your current goals or environment. If I were falling behind in my classes or failing to reach my deadlines, that might be cause for reflection.

On the other hand, there’s a perverse tendency to judge yourself against some ideal benchmark. Comparing yourself against a theoretical possibility, rather than your own past results. If you get more done than you were getting done before, the system is successful. That you’re not able to work for sixteen hours without break cannot be viewed as a failure.

Rule #7 – A system cannot give your work meaning or motivation.

A system can only shape and direct the motivations you already have, it cannot give you ones you don’t already possess.

Work that feels miserable to you doesn’t magically become exciting with the right productivity system. At best, it becomes an endurable chore.

Many failures of productivity are, at their root, deeper problems of meaning and mission in life. If you’re spending your days at a job you hate, if you’re studying a major you were coerced into rather than freely chose, if your dream job has become a nightmare, then no productivity system can fix this.

Productivity systems work better the more natural enthusiasm you have. They work like a lens, magnifying and directing the diffuse energy you already possess. The people, therefore, that tend to succeed with productivity systems already have a meaning and drive for their work. They have ambitions and recognize that getting things done efficiently is necessary for reaching them.

The post 7 Rules for Staying Productive Long-Term appeared first on Scott H Young.