Scott H. Young's Blog, page 24

June 28, 2021

What is Understanding?

We all have an intuition about what it means to understand something. We all know what it’s like to be confused. We know both the pain of memorizing an answer you don’t understand as well as the satisfaction that comes from finally “getting it.” Yet what that intuition points to is hard to pin down.

The impetus to really understand what we’re learning was a central theme in my early writing. While I still agree this is important, I’m less clear what it means. Beyond this satisfying feeling, what does it mean to understand?

Some Understandings of UnderstandingTo sort out this confusion, let’s look at a few possibilities of what understanding might be.

1. Understanding as Connected InformationMy original model of understanding was connected information: To understand something means having many connections between it and related ideas. Analogies assist with understanding by grafting a previous intuition onto a less familiar domain.

In this view, the key to developing understanding is to draw relationships between what you already understand and what you are trying to understand. Analogies, metaphors, visualizations, and associations try to find a fit between new and old knowledge.

This model is a useful starting point, but I think it has some flaws. A major one is simply a bootstrapping problem: If you don’t have some preliminary understanding, it’s very difficult to generate correct analogies.

This bootstrapping problem also suggests a different kind of “direct” understanding of something that precedes attempts to relate it to something else. We can understand many things without intermediating analogies, so it’s also possible that while connection-forming is a useful strategy, it may not fully describe what understanding actually is.

2. Understanding as Flexible ActionA different way of looking at understanding is application: To understand something means to be able to interact with it flexibly. The person who can deal with a wide range of algebra problems “understands” algebra in a way that a person who can only solve stereotyped formulas does not. Understanding physics means being able to deal with novel physics problems. Understanding chess means being able to play well from a variety of different positions.

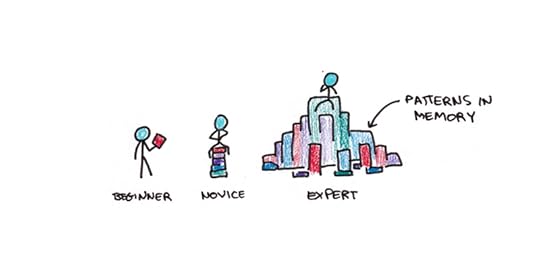

This perspective is bolstered by work in psychology that shows expertise resulting from a greater quantity of stored patterns. De Groot’s work with chess grandmasters found that the strongest players didn’t think further ahead than weaker players.1 Instead, experts seem to rely on having many examples in memory to infer the correct move. The difference between useful understanding and rote memorization may have more to do with the sheer quantity of remembered patterns rather than a qualitative difference in the patterns themselves.

There’s probably truth to this perspective as well, but I suspect it’s incomplete. It doesn’t capture the feeling of insight when a concept “clicks” into place.

3. Understanding as Explanatory AbilityFlexible action may remove cases of rote memorization, but there are many situations where we can behave flexibly, but wouldn’t claim deep understanding.

I tried teaching a friend to tread water years ago. While I feel very comfortable in the water, I found it surprisingly difficult to break down the movement. Flexible action, but no explanatory ability.

Alternatively, we might view explanation, not action, the central principle. The Feynman Technique and other tools aim at self-explanation as the final arbiter for understanding. Unfortunately, explanation isn’t a perfect proxy either, as an explanation can always be pushed deeper.

4. Understanding as Identifying Broad, Abstract PrinciplesFor a fourth perspective, we might view understanding as seeing deeper principles, the broad patterns underlying a case, rather than its superficial details. This view is compatible with the flexible application model but seeks to define understanding in terms of a mental process rather than an outward result.

Research shows that novices tend to view physics problems in terms of superficial details (pulleys, inclined planes). In contrast, experts see the same problems in terms of principles (conservation of energy, momentum).2

There doesn’t seem to be an easy way to instill this kind of abstract appreciation in students. While pointing out principles ought to help, it may be that we need a lot of exposure to problems to view them in this way. For newbies, the abstractions are simply invisible.

5. Understanding as Concrete Mental SimulationInstead of viewing understanding as seeing a specific problem in terms of its abstract principles, we might push in the opposite direction. Another way of understanding is a the ability to visualize or simulate what is happening in a problem concretely in your mind’s eye. These kinds of mental simulations seem particularly relevant for a discipline like physics, where they played a vital role in the feats of Albert Einstein and Richard Feynman.

The idea of simulation struck me when a physics student sent me a homework problem he was struggling with. It was about electrostatic force vectors in a set of four diagrams. The task was to pick which one was different. He had wrestled with it, diagramming each charge’s contribution and adding up the component vectors.

Yet, the answer was not for calculating. Out of the four diagrams, only one wasn’t symmetrical. Symmetrical forces cancel each other. Thus, without rigorously calculating the effect, a quick mental simulation of the forces showed the answer was obviously the imbalanced picture.

In this case, “understanding” math is quite different from simply being good at calculating. In fact, it might be a different ability altogether. This understanding of the math means being able to mentally simulate the reality the equations describe and infer consequences from that simulation. This skill of “understanding” would then intertwine with calculation, but the two are of a completely different sort.

While the parallel skills of performance and understanding seem obvious in math and physics, I suspect they have analogs in most abstract domains. The ability to “see” a problem’s consequences in economics, medicine or chemistry is often a different mental operation from the symbolic activities associated with “solving” the problem.

Practical Implications of Ways of UnderstandingIn the case of philosophical ambiguities—such as the meaning of the words “truth,” “justice,” or “reality”—I prefer the pragmatist approach. It’s less important to define words perfectly than to be able to use them competently. As long as you and I know the difference between a truth and a falsehood, then whether or not the Correspondence Theory of Truth runs into philosophical problems isn’t relevant.

Similarly, I’m interested in the practical consequences of the understandings of understanding. What do the different theories suggest about what we ought to do to foster it?

When viewed together, some useful patterns emerge. Increased exposure to an idea or skill ought to help develop most forms of understanding. It enables us to form more connections, store more patterns, see deeper principles, and create better mental simulations. Rather than repeating the same examples, varying exposure also seems important because understanding is usually defined by dealing with novel problems rather than repeating a past solution.

However, there are differences between the models as well. If understanding depends on mental simulation, it may be a separate ability that needs practice different from symbolic approaches.

Different views of understanding, such as flexible action and explanatory ability, suggest different kinds of practice. One requires building up procedural skill through repeated use, and the other requires crafting more and more articulate theories. These ends overlap, but not entirely. There are definitely cases where you could cultivate one kind of understanding but not the other.

Ultimately, it may simply be that there’s no singular process behind understanding. Instead of seeking a single way of understanding, we must guide our practice by asking ourselves more specific questions about what we want to do with what we learn.

The post What is Understanding? appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 21, 2021

Beware Tractability Bias

Human beings crave progress. That craving distorts what we work on. Vital pursuits with less tangible progress are frequently sidelined for trivialities we can check off a to-do list.

Think of the last time you updated your computer. Just having the progress bar made the wait more bearable. The inching left to right may have been inconsistent. It may have been downright misleading, as the frustration at witnessing it stall forever at exactly 99% can attest.

But imagine how much harder it would be to wait if the progress bar weren’t even there.

Progress itself is good. But it is more easily measured in some pursuits than others. This leads to tractability bias—the tendency to focus on pursuits with more conspicuous progress.1

An example: last week I was working on a new book proposal. Writing the opening chapter was hard. I’d end some days thinking, “Well, at least this time I got to 1500 words before deciding to throw it all in the trash.”

In the same time, I could have easily written three or four essays for this blog. Except, writing a new book has much greater potential than even a brilliant essay. Had I written the essays I would have felt productive. It just would have been on something that mattered much less.2

Sieging the CastleMy friend, Cal Newport, has likened the theorem-proving efforts of a computer scientist to sieging a castle.3 First you try the front gate, and get repelled. Then you try the ramparts on the side. You dig tunnels and construct battering rams. Progress is zero until you finally break through.

Morale is a perennial issue for besieging generals. Frustrations and fatigue mount with each failure. If success doesn’t arrive quickly, many armies will simply abandon the fight. It’s easier to plunder the countryside, even if it will never lead to a lasting conquest.

The choice between easy raids and hard sieges appears in our work as well. The routine tasks to tick off versus the real work that makes your career.

Tractability is Inversely Related to OpportunityTractable tasks are easier. But that also means there is more competition. Paul Graham argues this is a major factor behind the success of companies like Stripe:

For over a decade, every hacker who’d ever had to process payments online knew how painful the experience was. Thousands of people must have known about this problem. And yet when they started startups, they decided to build recipe sites, or aggregators for local events. Why? Why work on problems few care much about and no one will pay for, when you could fix one of the most important components of the world’s infrastructure?

…

Though the idea of fixing payments was right there in plain sight, they never saw it, because their unconscious mind shrank from the complications involved. You’d have to make deals with banks. How do you do that? Plus you’re moving money, so you’re going to have to deal with fraud, and people trying to break into your servers. Plus there are probably all sorts of regulations to comply with. It’s a lot more intimidating to start a startup like this than a recipe site.

A recipe website is tractable. Break it down, code up the features and you’re done. Creating a payment platform is not. But, if you can slog through the difficulties, the space is more valuable because the competition is sharply reduced.

Not all important work is intractable. But it is the intersection of intractability and importance that stymies us. Paying deliberate attention to that overlap matters because we’re more likely to neglect it.

Making the Real Work More TractableIt’s hard to feel progress when sieging a castle. You may have failed in the last attempt, and in doing so learned one more thing that doesn’t work. But how many more failures are still to come? Will breakthrough eventually be forthcoming? There’s no progress bar because the distance is still unknown.

But I think there are efforts we can make in our productivity systems to shift away from the easy satisfaction of checking off to-do items.

One strategy is to elevate the status of your sincere attempts. If your day is measured primarily in words written rather than hours of writing, this naturally pushes to more tractable tasks.

Another is to narrow what counts as the “real” work. I’ve found keeping a deep work tally enormously helpful. It prevents me from counting emailing, calls and other activity in a way that distorts away from more central challenges.

Finally a key to combat tractability bias is simply to stop tracking. If a metric misleads, it may be better to stop paying attention to it. If counting the number of books you read is keeping you from the longer, more important works—stop counting. If tallying up Twitter likes is keeping you from writing deeply-researched prose—stop tallying. If collecting citations is keeping you from writing your thesis—don’t track the total.

Real progress occurs when we hold the maxim that it is better to fail at what matters than to succeed at something trivial.

The post Beware Tractability Bias appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 14, 2021

14 Books On Learning by Doing, Apprenticeship and Transfer

Recently, I embarked on a research project exploring the topics of learning by doing, apprenticeship and transfer. I’ve just finished a big reading binge of a few dozen books loosely related to this topic.

Since I’m fully aware that at most 1% of the material I read will make it into any future writing, I thought I’d highlight some of the more interesting books I’ve read while they’re still fresh in my mind.

Here are some of the books that made me think the most…

1. Democracy and Education by John Dewey

1. Democracy and Education by John DeweyJohn Dewey was one of America’s most prominent public intellectuals a century ago. Today, few people would know him by name (when I mentioned him to a friend, she thought he was Melvil Dewey who came up with the Dewey Decimal system). Yet, as the father of the progressive education movement, his ideas are still being felt.

I won’t even try to summarize Dewey, but an idea that stood out was Dewey’s argument that the division between “higher” education and mere vocational training is nothing more than the philosophical baggage we’ve inherited from a society where aristocratic elite consumed useless arts and the lower classes did all the work.

2. Antifragile by Nassim Nicolas TalebWhen this book was published, I remember reading about a hundred pages of it and then putting it down. I was off-put by Taleb’s pugnacious literary style, in which everyone he disagrees with isn’t just wrong, but also a con artist. Perhaps I’m older and more cynical now, because I found the book a lot more enjoyable the second time around.

Taleb essentially argues that natural systems gain from disorder, whereas artificial inventions often exhibit fragility. He attacks the epistemic overconfidence of expertise, particularly in areas of economics and politics, where elegant mathematical models often have a dubious pairing to reality.

3. Cognition in Practice by Jean LaveDo people use the math they learn in the classroom in real life? Studies of transfer point to the abysmal performance of many skills we were supposed to have learned in school. Jean Lave’s ethnographic research, studying how people use math in their everyday lives, adds an interesting twist to this story.

Following people in the grocery store, she found the math they used in real situations was almost perfectly accurate. However, when the exact same calculations were transposed into a test-like format outside the store, people failed miserably. Lave argues that the picture of school as imparting general purpose cognitive tools to be applied elsewhere is misguided, and that our performance in everyday life is much better than experiments often give credit.

4. Apprenticeship in Early Modern Europe Edited by Maarten Prak and Patrick WallisWhen one thinks of learning by doing, apprenticeship naturally comes to mind. This volume was one of a few books I read on the topic, in this case looking at historical patterns of apprenticeship across Europe.

While I’m still a fan of learning by doing, the book highlighted some of the ways that apprenticeships fall short of an ideal. The tension between a master (who mostly gains from cheap labor) and an apprentice (who wants to one-day become his master’s competitor) creates interesting problems. Still, the authors credit the institution as a major cause in the Great Divergence, by which Europe emerged economically dominant, prior to the Industrial Revolution.

5. The Lean Start-Up by Eric RiesSomehow this book escaped my notice until now. It’s excellent. Ries argues that start-ups, due to the highly uncertain nature of their offering, need a fundamentally different approach to management than bigger firms. But, he argues, it is a management approach (as opposed to the seat-of-your-pants style that often pervades entrepreneurial ventures).

The problem, Ries argues, is that most start-up employees are talented builders. Given them the plan and they’ll make it. Unfortunately, too often, what is made isn’t what the customer actually wants—or the engine of growth the business creates is too slow to survive. Instead, entrepreneurs need to steer towards validated learning, even if it sacrifices big-business notions of efficiency.

What I found particularly interesting about the book is that it’s essentially a conceptual reorganization of what the “real” work of starting a company is. Many think it’s building a product and hoping for the best. Ries argues the real thing is figuring out what customers want.

6. How Innovation Works by Matthew RidleyRidley argues that innovation is more evolution than insight. The vision of the lone genius experiencing a “Eureka!” insight is not only wrong, but it holds back our future innovation through ineffective policies. But this is more than idle speculation, Ridley offers a vast array of stories to back up his thesis.

Ridley argues that, understanding how innovation works, we ought to rid ourselves of the patent system which fails to recognize simultaneous discovery and embroils inventors in costly legal battles. Also we need to recognize the need for learning by doing. Misguided regulations aimed at safety can occasionally backfire, by keeping us stuck with nascent designs that are actually less safe than what might be possible.

7. Laboratory Life by Bruno Latour and Steve WoolgarAn anthropologist spends a few years observing life in a leading biomedical laboratory. Observing how science is actually done, as opposed to how it is often idealized, he finds many common theories of science simply can’t be true. He argues that science, like all knowledge, is socially constructed.

Weeks after reading, I’m still not quite sure whether the thesis is obviously true or total nonsense. On the one hand, science is done by people. Issues of deciding which problems to work on, what evidence really ‘means’, whose work gets celebrated and whose gets ignored obviously matter.

On the other hand science seems to make contact with reality in a way that astrology or divination does not. Trying to understand science while remaining agnostic to its purported subject seems a bit like trying to understand the murmurings of art patrons while sitting in a gallery blindfolded.

Still, the fact that the ideas of the book have stayed in my mind for weeks after means it was definitely worth reading.

8. The Unschooled Mind by Howard GardenerGardener, best known for his theory of multiple intelligences, argues that students don’t arrive at the classroom as blank slates. Indeed, they come with strong prior assumptions about the world that are often wrong! From economics to politics, physics to poetry, students arrive with strong preconceptions that years of schooling often fail to modify.

I’m sympathetic to Gardener, as I believe there are many unintuitive things worth knowing in schools. However, I’m also suspicious of the a priori belief that certain scholastic ways of thinking are necessarily best. Gardener uses the example of students liking poetry that rhymes, being needed to be educated that good poems don’t need to rhyme. But one could also argue that this is simply elite tastes being imposed on the masses.

Much is made of studies showing students have a naively Aristotelian model of physics. This is seen as being simply fallacious, but I suspect it’s a natural byproduct of extensive experience with real world objects. “An object in motion tends to slow down” is physically false by Newton, but it is usually true, given that friction is ubiquitous. I definitely think physics is worth learning, but it also seems wrong to discount the impressive tacit knowledge that human beings have in dealing with the physical world.

However, I largely agree with Gardener that if we want to educate students to appreciate new physics or poetry, we can’t just get them to memorize the right answer—they need to experience real situations where the educated approach is more profitable. Otherwise education risks becoming segregated from the rest of life.

9. Mind over Machine by Hubert Dreyfus and Stuart DreyfusIn a sense, this book is completely outdated. The villain is good old-fashioned artificial intelligence techniques, expert systems and the assumption that all human thinking can be reduced to a simple set of rules. This was, at the time of the writing, the principle application of the computer metaphor to the mind.

Minds aren’t like machines in this way. We don’t reason through rules, consciously or subconsciously, simply because there would be an infinite number of rules to consider. These frame problems plagued artificial intelligence research. Yet deep learning seems to bypass many of these objections by learning in much the way the Dreyfus brothers argue should be done in humans—through pattern matching large libraries of “experiences” not simply observing hard-coded rules.

Still, I enjoyed the book because it represents a line of thinking that was largely derided by prestigious experts at the time, but which now pretty much everyone agrees was correct.

10. Shop Class as Soulcraft by Matthew CrawfordWhy do we denigrate the manual trades as being lower skilled than office work? Why do we encourage people to study hard only to spend their lives doing meaningless bureaucratic tasks from within a cubicle? Maybe those people would enjoy fixing things more?

Crawford’s broad-ranging attack on our cultural bias towards abstract education over hands-on work is an interesting journey. The more I probe into this topic, the more I sympathize with the view that the prestige value associated with many fields of study rests on a questionable pedestal.

Yet, I depart from Crawford in many respects. He blames capitalism for giving us too many conveniences, robbing us of the joys of repairing one’s own car. I tend to be more sympathetic to the economists on this point—a world of self-reliance is a world of unending toil. While non-college work deserve more of our esteem, I’m happy that most of my devices break down so little that I don’t know how to fix them. Progress is good, even if it sometimes has side-effects.

11. Transfer on Trial Edited by Daniel DettermanBeginning with “A Case for the Prosecution” Detterman takes the strong view that education’s lauded goal of teaching wide-ranging, all-purpose skills has utterly failed. After summarizing the evidence, he explains:

“When I began teaching, I thought it was important to make things as hard as possible for students so they would discover the principles themselves. I thought the discovery of principles was a fundamental skill that students needed to learn and transfer to new situations. Now I view education, even graduate education, as the learning of information. … In general, I subscribe to the principle that you should teach people exactly what you want them to learn in a situation as close as possible to the one in which the learning will be applied.” [emphasis mine]

While not all of the contributors to this volume are nearly so pessimistic, I’ve found reading the constellation of studies on transfer helpful for narrowing down my understanding of what learning actually is. What remains clear to me is that the issue of transfer isn’t a peripheral worry, but the central concern if we want to learn and grow.

12. Transfer of Cognitive Skill by John Anderson and Mark SingleySingley and Anderson attempt to provide an answer to the question of “what is actually learned?” when we do things. They formulate their answer in terms of “production systems” which are little IF -> THEN rules applied to the situation. These rules can be extremely specific (e.g. IF you see the variable x next to a constant THEN divide both sides of the equation by the constant) or they can be rather abstract (e.g. IF you see a complicated problem THEN break it into sub-problems).

For practical purposes, the production system approach is the most useful one I’ve read when trying to explain what gets transferred between situations. It accommodates both the fact that actual performance of skill depends on getting many low-level details right, along with the fact that more abstract ideas are useful and can occasionally cross disciplinary boundaries. The system also helps explain why sometimes we fail to transfer ideas that should be obviously useful.

Still, production systems suffer from the same flaws as good old-fashioned AI critiqued by the Dreyfus brothers above. The empirical tests of their system, while suggestive, are also far from proclaiming production systems is how we really think.

13. The Tacit Dimension by Michael PolanyiTacit knowledge, the idea that there are skills we know how to do but can’t explain how we do them, was first introduced by Michael Polanyi in his magnum opus Personal Knowledge. This shorter book revisits the concept, which Polanyi made an essential part of his justification of science.

14. The Craftsman by Richard SennettManipulating objects in the physical world is essential to thinking. Philosopher Richard Sennett covers considerable ground arguing that we need our hands to use our minds. The writing is engaging, covering examples from the perils of computer automated design, to Linux developers and how Julia Childs teaches you how to cook a chicken.

====

Some other books I also enjoyed included Phil Agre’s blend of continental philosophy and computer programming in Computation and Human Experience, Michael Polanyi’s vigorous defense of science in Personal Knowledge, and David Goggins feats of human endurance in Can’t Hurt Me.

The post 14 Books On Learning by Doing, Apprenticeship and Transfer appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 7, 2021

Digging the Well

I recently came across an essay by Tanner Greer about the rise and decline of public intellectuals. Many appear as geniuses for a time, before later becoming a punch line. Why does this happen?

Greer starts with an obvious explanation—genius peaks. As we age, our raw talents decline and we can no longer sustain brilliance. I’d add to this regression to the mean. Chance will allow some the right idea at the right time to make them seem prophetic. But luck fades.

However, toward the end of the essay, Greer offers another explanation. Using Thomas Friedman, the veteran New York Times reporter and author of The World is Flat, as an example, Greer writes:

And this bring my second, sociological explanation into play. There are things that a mind past its optimum can do to optimize what analytic and creative power it still has. But once a great writer has reached the top of their world, they face few incentives to do any of these things.

Consider: Thomas Friedman’s career began as a beat reporter in a war-zone. He spent his time on Lebanese streets talking to real people in the thick of civil war. He was thrown into the deep and forced to swim. The experiences and insights he gained doing so led directly to many of the ideas that would make him famous a decade later.

In what deeps does Friedman now swim?

This suggests an altogether different explanation than simply declining abilities or luck. Creative success is akin to digging a well. There’s much sweat and strain before you can drink a drop. But after, it’s hard to start digging again once the comforts of success start flowing.

Work and Well-Digging

Work and Well-DiggingWhen I first read Greer’s piece, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own life. I’m hardly a public intellectual—just a blogger who likes to doodle. But I see distinct parallels in my own career.

Ten years ago, I was in my peak well-digging years. I embarked on year-long projects with little expectation for a payoff. I was single and childless. My only limit was personal endurance and boldness. Despite not being pursued for money, these projects ended up forming the foundation of my later writing success.

Now I run a business with employees, I have a wife and son. The idea of spending sixty-hours a week on any project, never mind one with uncertain rewards, is a fantasy.

I’ve also grown soft. I’m long from my college days when taking the bus was a splurge (I had a bicycle, after all). I could afford to see my income contract during speculative projects. But I’ve become less daring with a family to support.

Seeing myself mirrored in Greer’s critique, I wonder when my well might run dry (or whether it already has) and what I ought to do to keep digging.

Has the Well Run Dry?Two objections immediately come to mind. The first is simply that there is more to life than being at the bleeding edge. Maybe Thomas Friedman would be a better journalist if he continued to throw himself into war zones, but his life would likely be worse. There’s nothing inherently wrong from shifting from youthful ambition to middle-aged comfort.

The second is that we can’t actually look backward. Comfort breeds complacency, yes. But it offers resources as well. In my own career, trying to repeat earlier adventures would be a mistake. If I attempted the MIT Challenge now, I’d probably only be able to do it half as well for twice the effort. Rather than digging in the old well, it’s time to find new waters.

None of this, however, avoids the conclusion of Greer’s essay: creative accomplishment requires digging deep. The well you dig may change, but there’s no escaping the effort.

What wells did you have to dig to get where you are now? Which of them have already started running dry? What is the unglamorous activity you’d need to do to dig new ones?

The post Digging the Well appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 31, 2021

Make Your Life Better by Doing Less

I recently came across the following Nature article, “People systematically overlook subtractive changes.” From the abstract:

“Here we show that people systematically default to searching for additive transformations, and consequently overlook subtractive transformations. Across eight experiments, participants were less likely to identify advantageous subtractive changes … Defaulting to searches for additive changes may be one reason that people struggle to mitigate overburdened schedules, institutional red tape and damaging effects on the planet.”

This research fits into the theme of books such as Essenialism, The ONE Thing or Hell Yeah or No. When we want to improve life, we think of adding things–new goals, efforts and commitments. Removing things to improve life is often overlooked.

This is something I’ve given a lot of thought to since becoming a father. The best changes I made in the last year tended to come from subtracting something rather than adding new efforts. Quitting social media, for instance, had much better results than I had expected.

Every Yes Implies a NoCal Newport published a similar essay to mine recently. Funnily enough, I had finished writing this prior to seeing his. However, given their overlapping source material and conclusions, I encourage everyone to read Cal’s essay as well.

Logically speaking, since time is a fixed quantity, everything you say yes to implies a no to something else and vice versa. Seen this way, there ought to be no difference between additive and subtractive life changes.

But our minds can’t easily appreciate this non-dual nature of reality. Saying yes subtly squeezes everything else, but rarely in ways we can easily perceive. When saying no, what is left over is enriched, but this additional space is often neglected.

I think there’s a connection between this idea and my current research project. We often spread ourselves so thinly that we find it hard to get to the threshold of effort needed to do the real thing. Many of our hobbies, interests or even professional ambitions get stuck as a consequence.

This is something I definitely sympathize with. I have too many things I want to learn, and old skills I struggle to maintain. Being broadly interested is great, but the downside is very often that you stretch yourself too thin, rarely leaving enough time to delve deep enough to make real progress.

“No” or “Not Right Now”

“No” or “Not Right Now”We tend to think of procrastination as a vice, but it can be a powerful tool to deal with our overloaded lives. The problem is simply that saying “no” to a particular pursuit can be hard. But saying “not right now” works just as well. It prevents the pursuit from taking up time, while leaving open the possibility of change later.

A good friend of mine was encouraging me to take up tennis recently. There’s public tennis court near my apartment and I could see myself really getting into it. But getting good enough to play would require a fair bit of practice, even maybe taking lessons. It’s a nice idea, but not something I have time for now. Saying “not right now” keeps my schedule sane without closing the door on it altogether.

Only Home-Run Projects

Only Home-Run ProjectsIn my work, this attitude has crystalized into a mantra to only take on “home-run” projects. It’s too easy to get sucked into the allure of “small” projects, that have unclear value. Of course, the small projects end up being not-that-small, and the value they were supposed to create fails to materialize.

The point isn’t to take on only big projects, but simply to be much stricter in evaluating which projects to pursue. If something doesn’t either have a significant and near-certain upside, or a potentially enormous and uncertain upside, it probably isn’t worth considering.

An entrepreneur friend of mine told me that he doesn’t work on any project that doesn’t have the potential to increase revenue by at least ten percent. I don’t think of my own projects in purely monetary terms, but I do think this is useful heuristic when evaluating your professional work.

Overwhelmed with EasyPreviously, I’ve asserted that the hard way is often the easy way. Committing to doing something you know will be hard, paradoxically, often results in an easier time than opting for something that seems easy.

I think the issue of subtractive changes helps explain this. When you take on a hard goal, you naturally make room for it. A goal that pretends to be easy doesn’t require those adjustments, so they’re rarely made. Instead, they squeeze down on everything else in your life until those other things start pushing back.

In many cases, I think, we’ve opted for the inverted problem. Instead of clarifying our pursuits into the few, difficult obstacles they represent and deliberately crafting strategies for dealing with them, we’ve opted for a myriad of seemingly easy problems. Except the easy problems end up filling up our lives, leaving little room for what really matters.

The post Make Your Life Better by Doing Less appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 24, 2021

How I Do Research

For the past several years, I’ve been trying to get better at research. I’m far from a master, but I’ve learned some strategies that have helped.

I’ve done smaller research-driven essays, from looking into explore-exploit tradeoffs, how aging affects learning and whether speed reading works. I’ve also worked on longer efforts that had me reading quite a bit of material, like I did for my book or my guide on motivation.

Research is an essential part of thinking for yourself. For if you can’t find and understand other people’s arguments, you tend to get stuck either with what your intuition tells you or with the opinion of just one person who managed to catch your attention.

I’m definitely not an expert researcher, but I thought I’d like to share how I go about it, both to clarify my own thinking and to give some help to those who would like to know how to satisfy their curiosity, but aren’t quite sure how to start.

Setting Up Scope and Topic

Setting Up Scope and TopicUnlike learning from a class, research tends to be open-ended. There’s always another book or paper you can read that potentially has an important insight. You’ll rarely reach a stopping point that will tell you you’re done.

But this feature of research efforts also makes them hard to sustain. Our brains like boxes we can check off the to-do list. Open-ended activity often languishes from a lack of completeness.

I recommend deciding how much time you want to commit in advance. I also advise making the end goal to do something with the information, such as writing an essay, rather than have it remain purely mental. Writing an essay or report forces you to organize your thinking, remember key details and ensure you actually understood what you read.

Beginning Research: Looking for Key Works and KeywordsOnce you have a scope and topic, the next step is to find the expert vocabulary that matches the topic you’re interested in.

Experts divide up the world in ways that don’t always match how ordinary people think about it. If you want to know what experts think about discipline, then, you’ll quickly find that there’s a difference between self-control, self-regulation, vigilance and grit. In some cases, the words represent fine-grained distinctions in ideas. In other cases, they represent different territories, policed by different groups with different experiments and methodologies.

Wikipedia is usually a good starting point, because it tends to bridge the ordinary language way of talking about phenomena and expert concepts and hypotheses. Type your idea into Wikipedia in plain English, and then note the words and concepts used by experts

With keywords in hand, you can start with trying to identify key works. What are the central texts in this field that other experts all agree are important? Which summarize the field so that you can get a birds-eye view without needing to read too many papers?

Literature Review, Meta-Analysis and TextbooksOnce I’ve narrowed down what the keywords are, and possibly found some central papers or authors that everybody cites on the topic, I usually try to find reviews of the field. In particular, look for:

Literature reviews, which attempt a qualitative review of all the papers on a particular topic.Meta-analyses, which try to aggregate effects from many papers to provide a quantitative answer to a question.Textbooks, which being used to teach others tend to present the field in the way experts want new entrants to learn about it.A good way to start with this is simply to go to Google Scholar and type one of the keywords you identified earlier with the words “review” or “meta-analysis” and see what comes up. If I had previously identified “testing effect” as a concept of note from Wikipedia, I might then type in “testing effect review” or “testing effect meta-analysis.”

For textbooks, I often find it helpful to go to Amazon, enter in the keyword I’m looking for and then limit my search for textbooks. I did this for my most recent research project. I wanted to learn about apprenticeship, so I went through and checked all 47-ish pages of textbooks with “apprenticeship” in the title. After reading about two dozen Kindle previews for the most relevant seeming ones, I read a couple books in full.

Whether you should start with review papers or textbooks depends on the scope of the question you want to ask. Textbooks tend to be good for bigger topics, review papers for more specialized ones, although there is some overlap.

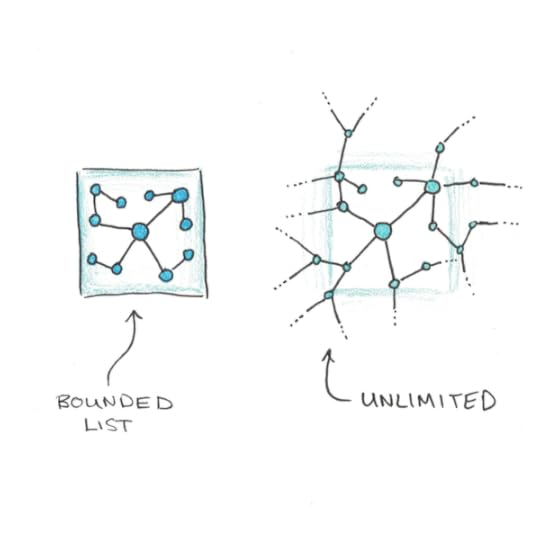

Following the Citation TrailsOnce you have a foothold within a field, the next step is to follow down citation trails. Since any given paper might cite dozens or even hundreds of other papers, this can easily lead to an exponentially growing reading list. Thus, I usually try to limit myself to a few of the most promising ones to start, unless I hit a dead-end.

When following citations, I look for two factors: frequency and relevance. Works that are cited frequently are more central to a field. If I see the same paper, book or author pop up multiple times, I’ll download a paper even if it doesn’t seem central to my original inquiry. Of course, I’ll also follow-up any reference that seems to directly address the question I care about.

This stage forms the bulk of the time spent. In general it’s better to follow a breadth-first rather than depth-first search, since you can easily spend too much time going down one rabbit hole and miss alternate perspectives. But I don’t follow it slavishly—sometimes you’ll dig into a rich vein of research that answers questions you didn’t even know you had. I ended up adding whole chapters to my book simply because the research was too good to leave as a footnote.

How to Read ResearchI once asked Bryan Caplan how he does research, as I admire him as someone to have made me change my mind largely through sheer thoroughness of argument. He said that he reads all of the papers he can, and then when he’s about to write on them, he re-reads them.

Forgetting what you’ve read (or where you’ve read it) is a classic problem in research. Some people have very sophisticated systems for avoiding this, such as Zettlekasten. I don’t find those methods very helpful, but it’s possible that I’m simply inept at them.

Instead, I prefer Caplan’s approach. Read everything you can, including making highlights of sections you think you may need to revisit later. If I finish a book or longer paper, I’ll often make a new document where I’ll pull notes and quotes from my original reading, as well as do my best to summarize what I read from memory. The goal here is partly to practice retrieval and understanding, but also partly to give yourself breadcrumbs so you can find things more easily later.

Some re-reading is probably necessary, though, especially if you’re tackling a big project. My own feeling is that the goal is not to get every fact and detail inside your head, but to have a good map of the area so you know where to look when you need to find it again. With luck, the main findings of the field will stick out, even if you can’t always recall every detail verbatim.

Other Tips and TacticsBeyond this basic approach, a few other tools have been very helpful:

Use Sci-Hub to get access to papers. While I’m normally not a big fan of copyright infringement, the current status-quo hardly makes me sympathetic to academic publishers, who have become largely parasitic on scientific enterprise. Alternatively, emailing authors directly often works to get access to papers, but it tends to slow things down as you follow trails of breadcrumbs.Use Google Books to hunt down notes within your printed books. I used this a lot when writing my last book. If I wanted to find something in, say, my 900-page Van Gogh biography, I could flip through the index, but it was often easier just to search within the book on Google.Map out the key arguments and players. In rare cases, the question you want to ask will have been already settled by science. More typically, you’ll find a wide-variety of different stances argued and defended by different groups. I’ve often found it helpful to map out the key positions and proponents since this is the intellectual terrain where most of the pitched battles of arguments occur.Don’t be afraid to take courses first. Reading in a field is like joining midway through a conversation. Except it’s a conversation that’s been happening for hundreds of years. How much you need to back up and understand the prerequisite topics before you can usefully engage with the material depends on the discipline, but it rarely hurts to take some courses that provide a background in the topic.Experts are surprisingly willing to talk to you. I was surprised how many busy experts took my calls to discuss their work. K. Anders Ericsson was even nice enough to read through an entire draft of my book and give me feedback on places I mentioned deliberate practice.One thing I haven’t addressed is evaluating whether a literature itself is trustworthy. I think answering the question of “what do experts think is true?” is hard enough, even without questioning whether it actually is true. So while my abilities here are meager, How to Read a Paper offers a good intro into evaluating research. Still, with the replicability and generalizability problems inherent in many fields, it’s always worth being on-guard that today’s consensus will end up being tomorrow’s quackery.

Do you do research in your work? What strategies and steps would you add to this? I’d love to hear more, especially to improve my own ability to learn.

The post How I Do Research appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 17, 2021

Rapid Learner is Now Open

About once per year, I offer a new public session of my course, Rapid Learner. This is a six-week program that shows you how to learn better. If you’ve found my essays on the science of learning helpful, or found my learning projects interesting, this course shows you how to do it:

Be sure to check it out before Friday, May 21st at midnight Pacific Time. Then, I’ll be closing registration so the new students can begin.

The post Rapid Learner is Now Open appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 15, 2021

The Key to Find Time for Learning

When I was in my twenties, finding time for learning was easy. Committing to doing the work could be hard, but there was always spare time. Now, as a father and business owner, I can relate to the struggle to find time to learn things.

My to-learn list is long and ever-growing. I have dozens of unread books in my library. I have a tab in my browser saving courses I want to watch. I have many new skills I’d like to learn and dozens more I want to maintain and master.

But, at the end of the week, there may only be few hours to learn. How do you fit it in? Below I’d like to articulate the strategies that have helped me find time to learn more things.

Strategy #1: Only Have One Project

Strategy #1: Only Have One ProjectA simple rule I follow is to only have one project at a time. If you want to learn tennis, painting and programming, pick one. You can always learn something else later, but if you find you lack time for one then you will definitely fail to find time for three.

What makes something a project? This can get a little fuzzy, but my definition would be that a learning effort is a project if it wouldn’t happen more or less automatically without effort. So if you’re an avid tennis player and would probably play a game or two a month regardless, that’s not a project. But if you’re new to the sport and need to practice drills for hours to get good enough to play, that definitely is.

Sometimes when I advise people with multiple pursuits to pick one project, they rebel. “But those other projects also matter to me!” they’ll say. Good. Then do them after you’ve made progress in one.

In practice, sequentially pursuing projects doesn’t limit your breadth. I think the resistance may be more owing to the fact that learning is hard, and by failing to commit to any one project, its easier to fantasize about the idea of learning it. Committing to doing one project first before another prevents this escape, but also allows you to make real progress.

Strategy #2: Make Learning FrictionlessIf you have limited time to learn, you need to make learning as easy as possible to get started. The only exception to this trend is that, in making it easier, you don’t want to eliminate the actual practice you need to get good.

One way you can do this is by setting up your environment so you can get started immediately. If every time you want to practice, you need to spend twenty minutes pulling up equipment, then you’ll never practice unless you’re willing to commit at least an hour. Except a full hour might be hard to find in a busy life, so you never practice.

Some ways you can make learning frictionless are:

Have materials on you at all times. If you’re reading, always carry a book or Kindle. If you want to draw, carry a sketchbook. Download materials on your phone so they’re ready when you are.Set up your working area so starting is instantaneous. If you’re painting, keep your easel out and paints premixed. If you’re programming, keep your window with the project open so you can click over and start coding. If you’re studying for an exam, keep the practice questions open on a desk, ready to start—even if just for ten minutes.Batch all the tedious starting work. Sometimes you need to do something unpleasant and tedious before you can get to the real work of learning. Setting up the programming environment to learn a new language, for instance, is one of the most annoying parts of a new project. Setting aside time to do this specifically will make it easier to take advantage of fifteen minute chunks you find to make progress.Strategy #3: Integrate Learning with Your LifeMany projects fall off our schedule because, ultimately, they don’t align with the other sources of meaning in our life. Something that fits within your existing work, social or family pursuits may require some effort at first, but eventually it becomes something that’s hard not to do.

If you need to learn something for work, for instance, a good starting point is to ask yourself how you can make it mandatory for you to learn it. If you can get assigned a project where the skill is required, then it will be easier to learn than if the learning part needs to be done first, before any responsibilities are assigned.

Similarly, the hobby that integrates with your social life, learning something to do with your kids or applying a skill to make other parts of your life smoother and easier, is a key to making it last. When learning is disconnected from other things we care about, it tends to fall away.

Strategy #4: Remove Time-Wasting AlternativesWhat makes reading hard is that Netflix is always a click away. What makes doing a programming project hard is that you could be playing video games instead. What makes speaking a new language hard is that your native language is also an option.

While we often act as if time itself is the biggest barrier to progress, effort is the more likely culprit. Many people are extraordinarily busy, but then somehow find time to spend hours watching television or playing on their phones. This isn’t to judge, but simply to note that finding time doesn’t help if the problem is fundamentally that it is too effortful to learn.

A useful strategy is to temporarily suspend any of the activities you normally spend time on: television, phones, games and social media. After a month, see which ones you want to reintroduce and keep off the ones you don’t miss. This not only saves time, but it makes the activities involved in learning less effortful by way of contrast.

The Drive to LearnFinding time for learning is, ultimately, a question of motivation. I don’t think it can come about because there’s stuff you feel you should learn, or because you feel guilty for not reading enough books. Instead, I think the motivation to learn has to come from something that excites you instead—the idea of speaking another language, learning a new sport, mastering a difficult topic or being a better person has to interest you enough to make it worth it.

On Monday, I’ll be reopening my six-week learning course, Rapid Learner, for a new session. This course will guide you through strategies for learning more effectively, to make much better use of that limited time!

The post The Key to Find Time for Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 13, 2021

How to Think for Yourself

Our culture celebrates originality and creativity. We want our students to think for themselves, not blindly follow tradition, authority and received opinion. After all, doesn’t science, art and politics depend on us all coming to our own answers?

I definitely support the idea of coming to your own beliefs about things. But the way we do it isn’t how it is often portrayed. Thinking for oneself means, first, grappling with a lot of thoughts of other people. Creativity depends on copied insights. Originality is built from mastery.

Descartes’ Error

Descartes’ ErrorOur confusion about thinking can be traced back to the philosopher Rene Descartes. The Frenchman, while stationed in Dutch-speaking Neuburg an der Donau, decided to withdraw into his room, heated by his stove, so he could think for himself.

From his physical and social isolation, Descartes would work out a new philosophy. He decided to toss aside any of his knowledge that could be faulty. He would work from first principles only on the things he knew from direct experience were undeniably true. This, in turn, led to his formulation, “I think, therefore I am.” Arguing that even if the entire world around him was an illusion, it could not be an illusion that he was, in fact, thinking.

This moment set in motion modern philosophy, and with it many of the long-standing difficulties about knowledge, reality and morality.

Except, it’s possible that Descartes wasn’t quite as isolated as it seems. According to historian David Wootton, a Dutchman by the name of Isaac Beeckman may have suggested some of Descartes initial ideas.1 Descartes bitterly rejected the possible influence on his ideas, but his defensiveness may have had more to do with how it conflicted with his ideal of total introspection in his philosophy.

Thinking for Yourself, Through OthersIf even Descartes’ puritanical quest to reason purely from first principles was influenced by outside opinion, how can we possibly think for ourselves?

The answer, of course, is the same way everyone does. You think for yourself first by learning a lot of the thoughts of other people. Other thoughts and ideas don’t pollute originality and independence, they create the preconditions for it.

[image error]The person who claims to think for himself, yet scorns learning from other sources, invariably is under the hidden influence of a source he doesn’t recognize. The only way to truly think independently is to have enough knowledge to spot the hidden assumptions that underwrite your current views.

Groupthink and ConformityOf course, accumulating knowledge doesn’t always lead to independent thought. We all can point to instances of groupthink, where the more people discuss, the more they form a consensus that turns out to be wrong.

Similarly, schooling is often just as much about obedience as it is about learning. We teach the scientific method, but mostly in the same way as religious scriptures—facts brought to us by authority, rather than truths discovered through experience.

[image error]Yet, in both cases, the problems of conformity and false consensus are solved by… more learning. As you encounter more ideas and arguments, you start to spot the holes in foundations that previously felt unassailable. Reading a single book makes you feel that the author has it all figured out. Reading a dozen quickly shows that he doesn’t.

Thinking and Learning are Two Sides of the Same CoinIf you want to think for yourself, the only path forward is to learn more. Not just from those who have the same opinions you do, but from everyone who disagrees. And not just the average person who disagrees, but the smartest people who object.

If an idea is popular among intelligent people, but strikes you as completely wrong… you’ve probably misunderstood it. This isn’t that every idea believed by smart people is necessarily correct, many of them contradict. But if you can’t see why smart people could believe it, you’ve probably failed to understand the actual argument.

Descartes was wrong. We can’t begin at a position of independent thought, and from that, deduce the truth of the universe. Instead, we begin as captives of the beliefs that permeate our surroundings. We construct our freedom through learning more, not by ignoring the thinking of other people, but by diving straight into it.

This essay is part of a series leading up to a new session of my course, Rapid Learner. If you’re interested in diving deeper into research and strategies to learn more effectively, be sure to sign up.

The post How to Think for Yourself appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 11, 2021

The Science Behind Building General Skills

How do you build general skills? Abilities that not only help you with a narrow problem, but ones that you can apply repeatedly to problems in your life? Many of our goals, whether its becoming a better programmer, a savvier business leader or more original artist are of this type.

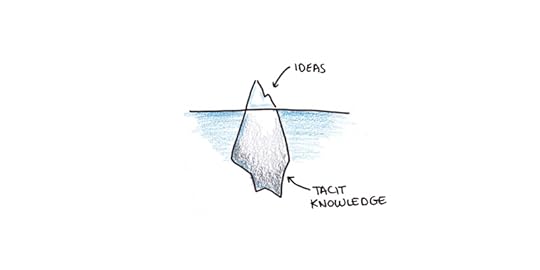

The bad news is that breadth is hard. General skills tend to be built out of many specific ones. Understanding deep ideas can help, but these too often depend on a lot of invisible tacit knowledge to apply correctly.

The good news is that, if you’re prepared to do the work, there’s better ways to learn and study that make breadth more likely.

The Narrowness of Acquired Ability

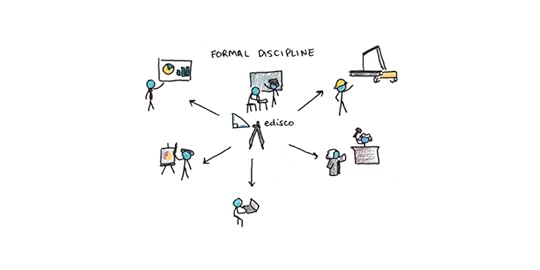

The Narrowness of Acquired AbilityEarlier theories of the mind suggested it was composed of a handful of separate faculties. Things like reason, language and attention. These, it was assumed, were like muscles—being strengthened by any kind of activity, they would lead to better thinking.

This theory of the mind manifested itself in formal discipline theory. This led to views that learning Latin and geometry were important, even if few students would use these skills in their lives, because by their formal character they acted as the ideal dumbbells for mental strength training.

In 1901, Edward Thorndike showed convincingly that this view was false.1 Training on one task didn’t help much with training on dissimilar tasks. He formulated a view, known as identical elements theory, that suggested that in order for training in one skill to apply to another, the two problems must share common elements. General skills, in other words, don’t exist.

Thorndike’s critique of formal discipline was correct. But his replacement theory wasn’t right either. Identical elements assumed it was the surface characteristics of a task that needed to match. A person hearing a problem they previously saw written, therefore, would be unable to solve it. In taking down a false theory of learning, Thorndike ruled out learning altogether.

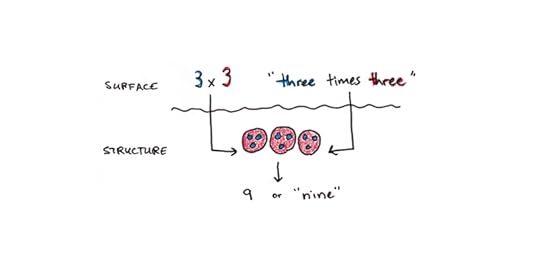

What About Ideas?What Thorndike got wrong was that it had to be only the superficial elements of a task that matched. A number is still a number, whether it’s spoken or written down. Provided a person has the ability to see the correspondence, the problems “three times three” and “3 x 3” are the same, even if they look different.

A more sophisticated argument would then say that problems can transfer to the extent that the mental operations needed to solve them can match. These mental operations are all quite specific, but they can be abstract.

Another way of putting this is that ideas still matter. An idea, as a more abstract, general notion, can influence your thinking on a wider range of problems than a procedure you memorize. Research shows this too, with those being taught the law of large numbers later applying it in different places and contexts.2

Is learning ideas then the road to general skills? This seems to be the reasoning behind programs that teach critical thinking or general problem solving strategies. You might argue my entire work of writing is predicated on this idea, as I’m also hoping to teach general ideas that apply to many cases, rather than just tricks for specific instances.

The Power (and Weakness) of IdeasLearning ideas can help, but it’s also not a silver bullet. There are a few key hurdles that need to be surmounted if a general idea will be generally useful:

We need to be able to recognize the idea in different contexts. This can be hard, especially if the contextual cues that ought to trigger the idea are not obvious. Researchers have found that, without hints, people tend not to apply patterns they learn to one problem to analogous ones in different domains.34 Even the research on teaching statistics found that people tend to apply it more readily when the problem domain suggests randomness or probability.5We need to be able to modify the idea to suit our current purposes. Knowing an idea, like evolution through natural selection, doesn’t automatically mean we can use it for all purposes. It takes a lot of work to apply it to understanding how technology or culture evolves, for instance.We need all the specific skills of implementation. This is another way of saying that ideas are easy and execution is hard. The two differ because to make successful use of an idea requires a mountain of specific skills. Knowing what recursion is and knowing how to apply it to your next programming problem are not the same thing.Ideas help. Without understanding an idea, learning general skills seems next to impossible. Indeed, the reason many investigations into transfer in schools have turned up so badly may be due to the fact that many students (even good ones) don’t really understand what they’re learning.6

Yet there’s a risk in seeing ideas as an answer, when they’re really only the beginning. The easy-to-spot ideas in a field may really just be the tip of an iceberg of invisible tacit knowledge. Wanting skills that float freely of any specific use, we may end up making ideas that are detached from all uses.

How Do General Skills Get Built?

How Do General Skills Get Built?Despite this, general skills do seem to occur. People develop expertise that allows them to solve wide ranges of problems. How does this happen?

A simple answer is that general skills are constructed out of narrow ones. The chess grandmaster has built an enormous library of patterns in chess, this gives her the ability to reason about board positions she’s never seen before, owing to their similarity to past games.7

In my own book, I documented how Richard Feynman, whose intuitive feats in math and physics were often deemed to be magical by his colleagues, nonetheless is an example of this process. His own description of how he solved difficult problems always pointed back to his extensive library of patterns in math and physics.

There seem to be a few keys, then, to acquiring more broadly useful skills:

Breadth comes from specificity. All general skills are built from large libraries of more specific knowledge and procedures. There’s no shortcut to expertise.Deeply understanding ideas helps. While not a panacea, deeply understanding more abstract ideas extends the useful range of your knowledge. But this only works if you really understand it.Visible knowledge is built on invisible skill. The ideas and facts you can easily point to, themselves depend on skills which are often harder to spot. Even the skill of recognizing where an idea applies and modifying it for your purposes are not trivial.Practice in a range of real situations. Because much important learning is tacit, learning general skills means facing a large variety of situations that require their use. When learning is confined to a single domain or context, it will be unlikely to leap beyond that in later application.Ultimately, the generality of the skill you want to learn is itself a question of cost. Sometimes not learning something is okay too, if it helps you get closer to your goals. When learning Chinese, for instance, I decided to learn to recognize characters, but not to handwrite them. To this day, I can’t write from memory, but I’ve read a number of books. It’s often better to begin with specific applications and broaden your skills as you need to, rather than conceive of them in the widest possible terms to start.

This essay is part of a series. To read the first part, go here.

Next week, I’m going to be reopening my course, Rapid Learner, which will offer more ideas and practical suggestions to improve how you learn.

The post The Science Behind Building General Skills appeared first on Scott H Young.