Scott H. Young's Blog, page 23

September 7, 2021

Is Modernity a Myth?

The biggest sin a book can commit is to be boring. A wrong book that makes you think is still worth the journey. With this in mind, I read French philosopher Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern during a recent vacation (you know, for some light summer reading). I found the book fascinating, even if I’m not quite sure I agree with it.

In this book, Latour grapples with our very conception of modernity.

What does it mean to live in a modern society? How are we different from our ancestors and all the supposedly “pre-modern” people around the world today?

Despite being published thirty years ago, We Have Never Been Modern feels timely. Media is fractured, information is exploding, and we’re cajoled to “follow the science” even though few have the skills to figure out what the science actually says. Are we living in a hypermodern time our tribal brains can’t comprehend? Or are we in a post-modern, post-truth society where everything is relative and anything is permitted?

Latour argues that our self-conception is a myth. We’re not living in a post-modern age, he argues, because modernity has never begun.

What Does It Mean to Be Modern?One way to argue that we’re modern is to simply look outside. We fly in planes, splice genes, and talk to people on the other side of the planet instantaneously. In this sense, we’re definitely different from medieval peasants or hunter-gatherers.

But modernity has often implied more than just technology. Pre-modern cultures have beliefs; we moderns have science. Those other cultures freely blend objective facts with socially useful superstitions. We moderns aren’t so confused.

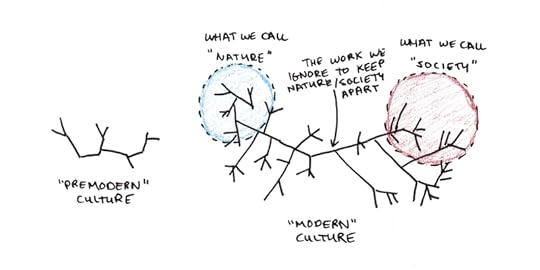

Instead, Latour argues that we never actually left the kind of society studied by anthropologists. An analysis of modern culture should be, in principle, just as possible with modern society as it is for tribes in the jungle. The reason we find it difficult, he argues, is that modernity is based on a paradoxical self-understanding, which he calls the modern constitution.

The Modern ConstitutionA constitution sets the framework for how a government functions. Likewise, we can imagine our own culture’s unwritten constitution as defining the separation of powers, obligations and tacit requirements needed to make our world work.

This modern constitution, Latour argues, is based on a series of self-supporting (and self-contradicting) principles.

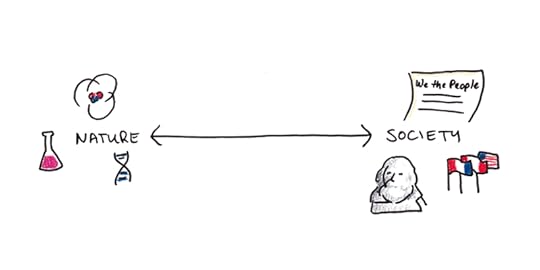

The first principle is the presumed separation between Nature and Society. Science allows us to separate the facts which exist independently of what people think of them. In contrast, democracy and liberalism allow us to construct the interpersonal order however we wish.

Latour traces this division to Robert Boyle and Thomas Hobbes.

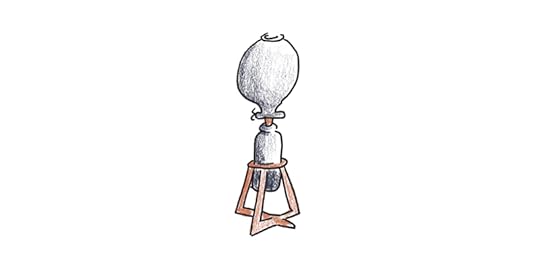

Boyle created an air pump that became a model for scientific investigation. For the first time, instruments witnessed by bystanders could create incontestable facts. This created a foundation for an “objective” reality separate from human subjectivity.

Hobbes, in contrast, imagined a purely constructed social order. In his Leviathan, he argued that citizens would bestow all authority to a single ruler to escape anarchy. Fealty to a king was hardly novel. But what was different was the reason for fealty. Hobbes imagined a political order that was grounded in a social contract, not appeals to God or nature.

Support for absolutist monarchy may have waned, but the idea that society is whatever we agree it should be is an assumption deeply rooted in the modern psyche.

Modernity, Latour asserts, is the product of their stalemated debate. Boyle wanted facts that would speak for themselves. Hobbes imagined a self-generated society independent from material circumstance. Nature and Society get pulled apart.

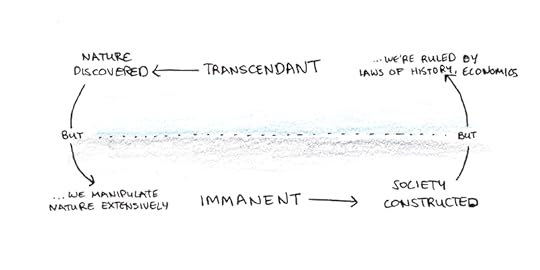

This first distinction leads to others. Nature is transcendent—we do not create it, only discover it. The air pump speaks the truth about the world we cannot argue over. Ignoring, of course, the technical difficulties needed to get it to work, the observers needed to interpret it, and the network of scientific communications to disseminate its universal findings.

Society, in contrast is immanent, it is a phenomenon inherent to humanity and independent of nature. Following Hobbes’ model, Latour argues, we design our political life entirely from scratch. If Nature is wholly outside our grasp, Society is entirely within it. Indeed, for something to be social, it is defined as something we construct by shared agreement.

Of course, these distinctions aren’t stable. Nature is transcendent, but we increasingly gain the power to modify, control and shape it to our desires. Society is immanent, but we increasingly discover iron laws of politics and economics that seem to prevent us from freely choosing its shape.

Latour argues that this absolute separation of transcendent Nature and immanent Society is self-contradictory. It can only be maintained because of an additional, harder-to-see separation in modern society.

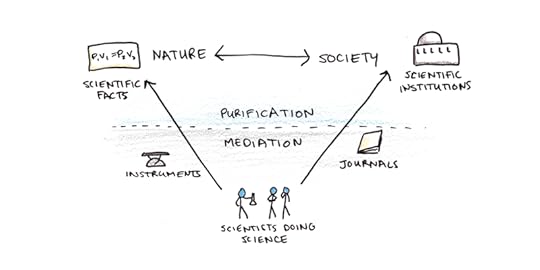

Purification and MediationLatour argues that our entire modern constitution is propped up by a further distinction between purification and mediation.

The world is full of quasi-objects—stubborn phenomena that are neither purely “objective” nor purely “conventional” but awkwardly straddle the line.

Consider a scientific journal article. Nearly everyone recognizes that social processes as well as natural ones constrain its creation—a paper might get ignored because it goes against the favored view of the most eminent theorist in the field. Is that a matter of scientific fact or social process? Neither—it’s somewhere in-between.

Purification is the process of separating nature from society. Separating “science” from the social world of the scientists needed to create it, as well as “democracy” from the various material factors that constrain it.

Mediation is the glue that holds the poles of Nature and Society together. Its the voting machine that tabulates the public will, the journal article that summarizes scientific fact. These factors tend to be ignored in modern discourse, or when they are focused on, it is merely on their ability to transmit objective facts or social agreement, rather than acting as complex agents in their own right.

Consider Boyle’s air pump: it can create a vacuum, something Aristotle thought logically impossible. But it also leaks occasionally. And it’s hard to interpret. How do we know that there’s nothing in the empty chamber? Indeed, mercury, which Boyle used in the experiment, has an associated vapor pressure, so in this case the “purely objective fact” of the vacuum is actually false!

The social process of purification is to tidy up all of this messy work of imperfect instrumentation, theoretical nitpicking, and arguments between experts to leave us with a pure product: a scientific fact. A fact is an entity that erases its own construction and thus is no longer up for debate.

Likewise, Society has similar processes we use to squeeze the ambiguity out of the material considerations needed in democracy—such as enforcing human rights or ensuring fair elections.

Unfortunately, because our “modern constitution” can only deal with pure processes, these hybrid, quasi-objects belonging to neither Nature nor Society must be ignored or treated as empty intermediaries, i.e., they channel a pure essence without contributing anything to the end result.

Latour argues that the dirty work performed by these unacknowledged hybrids is what runs our societies. But because of our commitments to the constitution, we rarely recognize it as such.

When we reunite the work of purification and mediation, we see that the principle difference between our society and earlier ones is scale, not kind. We have created a vastly more complicated network linking all the elements of our science and culture. Still, we have not created a distinct kind of culture that can see “objective reality.”

What Should We Make of This?

What Should We Make of This?As I said from the outset, I find Latour’s arguments interesting, even if I’m not entirely persuaded.

I had similar difficulty with Latour’s take on science in Laboratory Life. On the one hand, he did a good job explaining how all the sociological factors that affect any human endeavor also impact science: Researchers fight for credit. Scientists accept or ignore evidence based on tacit considerations of others’ work. What “counts” as a finding is itself a negotiated stance, with different researchers pushing for different levels of evidence or methodological rigor. All of which is pretty banal and obvious.

Yet, it seemed that Latour extended this argument to say that the fact that sociological factors influence science implies that science is arbitrary. That, with a different set of starting assumptions and political dynamics, we might end up with a totally different kind of science.

This seems crazy to me. Whatever reality is, it certainly constrains the outcomes of our theories and facts at least as much as sociological explanations do.

But maybe Latour isn’t actually saying that? Again, I find it hard to interpret his views here on a continuum from “science is shaped by human concerns in the boring and obvious ways you expect” to “science is totally arbitrary.”

Perhaps I’m finding it difficult to understand Latour’s views here, in part because I’m still committed to the dualism between Nature and Society he argues against. I think the only two options are “science is real” and “science is made up” because I’m still trying to see things only in terms of pure products of Nature or Society, and pretending all the hybrid elements needed to get both to work don’t exist.

Regardless of whether Latour is right or crazy wrong, I’m sure I’ll keep thinking about it. By that standard, We Have Never Been Modern is an excellent book.

The post Is Modernity a Myth? appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 30, 2021

Learning as Investing: 7 Skills That Pay Off in Any Job

It’s common to talk about learning as an investment. Economists talk about human capital, assuming that skills and knowledge, like machines or factories, are primarily things we can use to earn money.

Of all the reasons to learn, solely making money is hardly the best. I spend most of my learning time on things I don’t expect to earn me a penny.

Yet, since we talk about learning as an investment so frequently, I thought it would be interesting to ponder which skills have the best return on investment. If you were a portfolio manager for human capital, let’s say, what would you learn to maximize your return?

First, Some Quibbles…

First, Some Quibbles…The value of knowledge is not universal. For most people, knowing how to sing is not a lucrative skill. And then there’s Beyoncé. Similarly, even if machine learning experts or hedge fund managers can make millions by applying complex math, most people never use calculus outside the classroom.

So the correct, albeit dull, answer to the titular question would mirror the most economically valuable professions.

A more interesting answer would restrict our analysis to skills that are useful in a wide range of professions, abilities that you could add to many lines of work and see a return.

But we can go further. The value investing paradigm argues that the key is finding overlooked opportunities. The best investments aren’t the flashiest, but those that are neglected by everyone else. Invest here, and you can reap bigger returns than by chasing the latest fad.

With these two constraints in mind (i.e., non-profession-specific, underappreciated abilities), here would be my picks for a hypothetical portfolio:

1. Being Really Good at Excel

Everyone wants to be a programmer or AI developer (at least if my newsletter replies are any indication). Excel, in contrast, is boring. But a surprising amount of business activity depends on Excel.

In a previous post, I mentioned a friend who joked that his consulting business was basically just him being good at Excel. After that post was published, I got several emails from people who do the same thing (as well as business owners looking for such people).

Many of the most valuable skills aren’t cutting-edge; instead, they involve being highly skilled with a commonly used tool.

2. Writing Good Emails

Email is the basis for a dizzying amount of our work. My friend, Cal Newport, wrote a whole book about how this results in a “hyperactive hive mind” workflow that ruins our productivity.

Many workplace email threads I’ve seen are sloppy and disorganized which leads to a sea of noise. The bar is set really low here. Being able to organize and express your thoughts in a way that makes action items jump out and reduces back-and-forth is a tremendous asset.

3. Being a Non-Terrible Public Speaker

I have immense respect for good public speakers. Holding an audience’s attention isn’t easy. Doing so while being funny, polite, informative and helpful is an enormous task.

As with email, however, the bar is set quite low here. Being non-terrible as a speaker is enough to make you stand out at conferences and meetings.

At a minimum, you should be able to deliver a talk without reading notes or slides, communicate concisely, and pivot your presentation depending on the needs of your audience. A few months in Toastmasters can make a massive difference if you don’t feel confident speaking.

4. Getting Everything Done You Said You Would

A remarkable amount of economic success just comes down to basic reliability. Did you take on a task or project? Did you finish it on time, or did you need extra reminders and prodding?

Part of this skill is simply being organized and productive. But a lot of it is also about managing expectations. Many people, who feel unable to push back against demands, reluctantly agree to work they’re not sure they can deliver on. Yet this pressured “yes” often backfires and makes them seem less reliable in the future.

Richard Feynman famously got out of extra commitments by claiming to be irresponsible. But most of us aren’t Nobel-level geniuses, so the skill of being dependable is still at a premium for us mortals.

5. Researching Effectively

We tend to associate research with academics and journalists, but finding a comprehensive answer to a question is valuable in any field. Which is the best software to use? What do our competitors do? What do the experts recommend?

Knowing how to do research is hardly automatic. It took me years to figure out how to do systematic research that went beyond simple web searches. Getting answers from other people is itself an art that requires practice.

Even if you can’t be the smartest person in the room, you can learn to access what the smartest people think.

6. Ballparking Numbers

Most of our experience with math in school is finding exact answers to precisely worded questions. This is a shame because very few problems in life are like this. Instead, we more often face vague problems where only some of the numbers needed are known.

The physicist, Enrico Fermi, was famous for his ability to develop a good approximation to such questions. His technique was to start from easier-to-estimate numbers and successively work down to the harder-to-estimate quantities.

To illustrate, try to guess how many piano tuners there are in Chicago. Hard to do, right? But perhaps you could start with the population instead—that’s easy to look up. Then guess how many of those people own pianos. How often would they need to be tuned? How long does it take to tune a piano? If you follow through, you can get remarkably close to the true number.

Practicing the ability to quickly ballpark numbers, to make valid estimates of what things should be, is helpful for any quantitative line of work.

7. Learning New Software Quickly

Getting quickly on top of new software is increasingly a requirement for professions outside of IT. Doctors, teachers, lawyers and engineers constantly face new technical interfaces with their work—if you struggle to learn new software, your core professional skills may be undervalued.

I’ll admit, this isn’t my strong point. While I’m good enough at learning new software, I’m hardly a master. Still, knowing how valuable it is, I’ve made a point of hiring people who have this knack in my own business. Being the go-to person for figuring out new tools can give you a valuable edge over the competition.

Other Valuable SkillsWhich skills have I missed? I ignored some skills because they were too profession-specific (programming is still primarily useful for programmers, ditto machine learning). Others I left out because they seem to be commonly appreciated (leadership has its own shelf in the bookstore).

I imagine there are lots of skills that work well for particular fields. Figuring out what customers want to buy is huge in client-facing roles. Similarly, teaching is a tool that goes way beyond K-12.

What portfolio would you craft? If you had to invest, which skills would give you the greatest yield? I’d love to hear your thoughts…

The post Learning as Investing: 7 Skills That Pay Off in Any Job appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 23, 2021

Why Aren’t There More Apprenticeships?

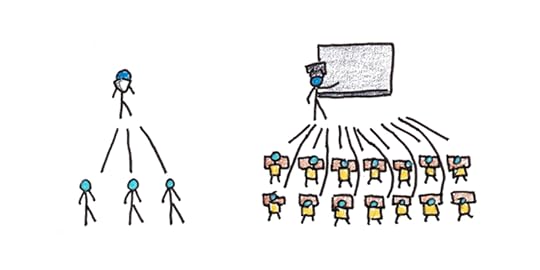

I’ve argued before that we mostly learn by doing. Yet, if this is true, it creates a puzzle: why has school largely replaced apprenticeships as a mode for learning?

The common answer is that apprenticeship works great for smithing and weaving, but modern work is mental. We need years of dedicated training inside the classroom before we can perform as knowledge workers.

I believe this answer is false given that many knowledge-intensive positions employ lengthy apprenticeship-like periods. Doctors must complete a residency; lawyers need to article; and grad school for scientists is effectively an apprenticeship. If apprenticeship was only valuable for manual trades, why would it feature so prominently in elite cognitive work?

If the common answer is wrong, we need to look for other explanations.

Explanation #1: Apprenticeships are Expensive

The most straightforward answer is simple economics. It’s cheaper to sit students in a classroom than to train them on the job. This is Tamar Jacoby’s position writing for The Atlantic when he examines why Germany’s famed apprenticeship program might be hard to replicate. Costs can reach up to $80,000 per student. While the cost of higher education has soared, the fundamentals of classroom instruction remain relatively cheap.

This cost has long been a factor in deterring apprenticeship programs. Economists have long noted that this form of training suffers from a problem of credible commitment. The issue is simple: the master wants cheap labor, the apprentice wants to learn the craft.

This creates two problems: If the apprentice learns too quickly, he can run away with the knowledge inside his head, thus robbing the master of his payment. Conversely, the master may purposefully drag out the apprenticeship to prolong their access to cheap labor.

If schooling is less efficient but cheaper than apprenticing, the cost savings might explain why it has become so prominent. Of course, another explanation is that schools do more to filter than to train.

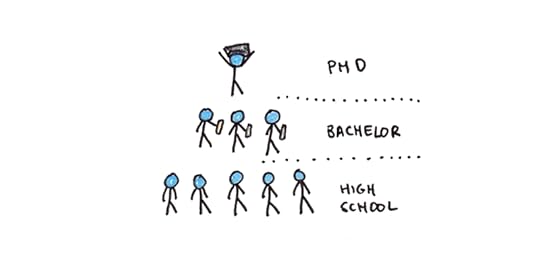

Explanation #2: Education is Mostly Signaling

Education serves two purposes. It teaches students valuable knowledge and skills. It also ranks students by their ability, conscientiousness and ambition.

The view that education is primarily the former is known as human capital theory. The view that education is mostly the latter is known as signaling theory.

If on-the-job training is essential but costly, it makes sense to consider only the best applicants. School, then, can serve an important function even if it mostly teaches useless things. Employers can reduce the risks of apprenticeship by filtering for the students who worked hardest and learned quickest.

But signaling can also devolve into escalating competition. When most people don’t finish high-school, a diploma might be enough to get a job. When everyone has a four-year degree, students may go deeper into debt to get an MA to gain a slight edge over the competition.

Explanation #3: Apprenticeships Have Declined, Learning-by-Doing Has Not

Formal apprenticeship programs may have declined, but learning-by-doing remains commonplace.

Perhaps the best evidence of this is to reflect on your own work experience. How much of what you do day-to-day was learned on the job compared to in school? Even the most stereotypically scholastic professions seem to involve enormous amounts of know-how acquired on the job.

If this is true, then the needed explanation shifts from “how do we learn what we do?” to “why do schools get most of the credit?” I’d suggest that schools often get outsized credit for skills for two reasons:

Schools teach the highest-level, easiest to articulate aspects of a profession. These are often treated in our culture as more important than the more obscure tacit knowledge needed to effectively use them. Learning algebra is lauded, though knowing how to turn real situations into the equations so algebra can actually be performed may be much harder.Schools are institutionalized. Learning-by-doing is not. Thus, to the extent that formal apprenticeships have waned, we have moved our focus to education. You can vote to fund or cut education, but not learning-by-doing, which makes the role of school more salient.From plumbers to particle physicists, most people learn their jobs by training under experienced practitioners. Our mode of learning hasn’t changed in modern times, but we often overlook it.

The post Why Aren’t There More Apprenticeships? appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 19, 2021

I’m 33

Today’s my birthday. Every year I share a birthday post with some personal reflections. Since this is now the fifteenth year I’ve been doing this, I won’t break tradition.

The idea I’ve kept returning to this year is one of consolidation.

Some of this is simply the changes imposed by parenthood. As I wrote previously, becoming a parent involves both a change in constraints and a shift in values. You have less time, but you also want different things than you did when you were single.

The past year, I’ve worked to cut back. Some of those cuts, like getting off social media, were probably for the best. I don’t miss Twitter drama or browsing random Reddit memes.

Other cuts were tougher. I stopped practicing the languages I learned in my Year Without English. For years after my trip, I kept up semi-regular iTalki conversations to keep them sharp. But maintaining fluency is trickier than I had anticipated. Not just because of decay, but the difficulty of keeping them separate.

I still feel some guilt about this pause in practice. But I’ve reconciled myself to more focused practice efforts when the need arises, rather than trying to keep them perpetually sharp. I still listen to and read Chinese, and I get Macedonian listening practice by way of my wife and her family. But I’ve accepted that maintaining my Spanish, Korean, Portuguese and French is not a focus for now, and they will need some brushing up if I’m going to use them at the levels I had previously reached.

In a similar light, I’ve found my hobbies and activities have gotten more focused as well. I’m trimming down to a few essential pursuits, rather than the sprawling interests I previously maintained.

While it would be easy to claim this is simply a lack of time, I don’t think that’s the case. The truth is, this move toward consolidation is one I have been contemplating for a long time.

Getting the Most Out of Life’s “Seasons”My friend Ramit Sethi has a compelling idea of “seasons” in one’s career. The basic idea is that what you want out of your job will change as you get older. Ambitions and a drive to prove oneself may get swapped out with a greater desire for flexibility.

I think something similar is true beyond your work. Every season of life affords opportunities and drawbacks. Living well isn’t just about optimizing for some universal good, but figuring out the best way to live, given your current phase of life.

When I was in my twenties, that meant taking a more expansive view. I wanted to try and do everything. In college, I lived in a dorm, joined student council, went on exchange, and partied a lot. The breadth of experience more than made up for the occasional drain on productivity.

After graduation, I took on ambitious, time-consuming projects. These established my career and also let me explore different possible trajectories for my life. While my path started and ended up at writing, there were times when I considered joining a start-up, living permanently in Asia, becoming a full-time programmer, or getting a PhD. I got to simulate and explore many of these paths, even if they weren’t the one I ended up walking down.

More firmly in my thirties now, I see a different landscape of opportunities. I see the possibility of producing meaningful work in my chosen path. I want to provide a stable life for my family and create the best opportunities for my son.

If the theme of my twenties was broadening the scope of possibilities, I imagine the theme of my thirties will be deepening those that already lie in front of me.

From Public to Private LearningOne way I see this theme of consolidation playing out is my decrease in public learning projects. While I can imagine myself doing a few one-month projects for fun at some point, I doubt I’ll return to the year-long projects of the past.

Ironically, this isn’t because I’ve stopped learning things. In some ways, I have more demanding learning challenges than ever. I’ve read nearly forty books and hundreds of papers for my most recent project in the last four months. I’m pushing myself to go deeper than I have in the past in developing an idea.

The difference is that instead of focusing on learning a new skill from scratch, I’m more interested in learning where the outcome is producing meaningful work. Learning is now the background of my writing rather than my central topic as it once was.

Good Problems to HaveAbove all, I have an incredible feeling of gratitude. This past year has been hard for many.

I am grateful now more than ever that most of my problems in life are nuisances rather than emergencies. I get to think about what kind of work I really want to do and the life I want to focus on, rather than responding to crises. I am grateful for the stability and opportunities that writing has brought me. For that, I owe a lot to the people who happen to like reading my blog and who buy my books and courses.

Regardless of where the next year takes me, I’ll do my best to share what I think is useful. Thank you for coming along with me.

The post I’m 33 appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 9, 2021

Book Recommendation: Uncommon Sense Teaching

Why read a book on the science of instruction?

We are all teachers, even if most of us aren’t professional educators.

Even if you don’t manage a classroom every day, teaching is an essential part of life. At work, you need to give presentations, coach new hires or explain the merits of a proposal to your boss. At home, you want to help your kids grow and thrive. All of this involves teaching.

And teaching is hard. Crossing the chasm that exists between what you know and what you want others to learn is difficult. Try as we might, many of us fail to create meaningful long-term changes in the people we want to help.

Learning From the Best

Learning From the BestBarbara Oakley is a highly awarded professor and the creator of Learning How to Learn, perhaps the most-viewed online course of all time. Her new book, Uncommon Sense Teaching, provides an in-depth guide to the best ways to teach.

Oakley partners with esteemed neuroscientist Terrence Sejnowski and long-time educator Beth Rogowski to provide an approach to teaching grounded in the latest cognitive science research.

I was lucky enough to receive an advance copy of this book, and I heartily recommend it. Whether you’re a traditional educator or simply someone who wants to help others learn better, this is the best summary I know of what works (and what doesn’t).

What Does Science Say About Teaching?Fortunately, there’s a lot of research that can give insight into the best way to teach. While scientific findings can’t replace the art of instructing, they can help you avoid common traps.

Some of my favorite ideas shared in the book included:

Avoiding “Grecian Urn Teaching.” This is the mistake of assuming that getting students to do anything related to the material will accomplish learning goals. The example given is having students make a paper maché urn for a Greek history class. To teach, we need to engage, but we must encourage engagement in ways that impart the skills we care about.Walking both declarative and procedural paths. Our knowledge of facts isn’t the same as our knowledge of skills. The best teachers help us store up ideas we can articulate, and they guide us through activities that will turn them into lasting abilities.Managing slower hikers and faster racers. Student ability varies, as does working memory capacity. Good teachers can structure curricula to keep the quicker students engaged while making sure the slower students don’t fall off. Ultimately slow and steady students may stand on more stable ground because their effort ensures the hard-won knowledge really sticks.Uncommon Sense Teaching is full of practical insights, including walkthroughs and worksheets showing how to take abstract theories and put them into practice. I recommend it for anyone who wants to be a more effective teacher, inside the classroom or outside of it.

What are the best books/resources you’ve learned for teaching? Share your recommendations in the comments.

The post Book Recommendation: Uncommon Sense Teaching appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 3, 2021

Is Life Better When You’re Busy?

Why is everybody so busy? Nearly a century ago, the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted we’d only work fifteen hours a week. Incomes would grow and so would our free time.

Except that hasn’t happened. Income rose, but we kept working long hours. Why?

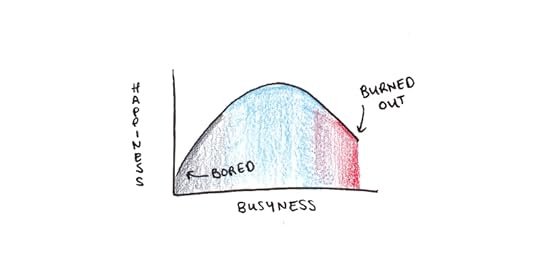

One answer is that people like to be busy. This paper argues that people dread idleness and are generally happier when they’re busy than when there’s nothing to do.

Crucially, however, you need a reason to be busy. Without a justification for activity, people choose idleness even though they’d rather be active. If we keep busy, and need a reason in order to do so, it suggests a lot of our busyness may be self-imposed.

Reasons for Our Collective BusynessWe feel too busy, but there’s evidence that at least some of that is unnecessary. What explains the gap?

I have a few theories:

Busyness as signaling. Busy people are important. Complaints about busyness are like complaints about paying too much in taxes—something that allows you to subtly communicate your status.Busyness as dodging commitment. Claiming busyness is a socially acceptable way to decline social obligations. “I wish I could, but I’m too busy,” is more polite than, “No, your nephew’s piano recital doesn’t interest me very much.”Busyness as self-deception. When you work on things, your goal is always to move toward a state of having less stuff left to do. Since less outstanding tasks is better within the context of your goal, you may incorrectly extend that to assume that having no outstanding tasks in life is ideal.Another plausible explanation is that busyness exists on a spectrum. We may abhor idleness, but being too busy stresses us out. There’s a sweet spot in the middle that suits us, and fine-tuning that amount is tricky.

Finding the Busyness Sweet SpotI feel like I’m happiest when I’m ever-so-slightly too busy. Not so busy that I feel overwhelmed, but enough to feel like there isn’t quite enough time to get everything done.

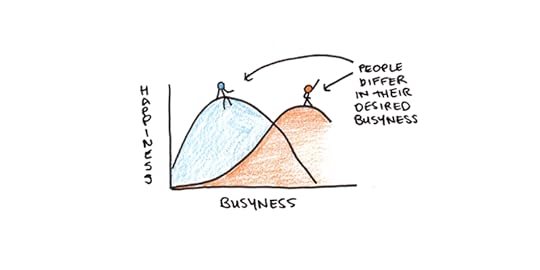

I think for most people, there’s a scale from utterly bored to burned out, with the ideal level of busyness lying somewhere in between:

Observationally, some people seem happier when closer to the “relaxed” end of the spectrum. In contrast, others seem to require more activity to be happy. This difference may even have a biological basis. Different people seem to have their dials set differently for the optimal level of stimulation.

Additionally, you might find yourself outside of this spectrum temporarily. It’s always possible to take on more commitments than you realize and feel busier than is ideal. It’s also possible to have few immediate outlets for activity and feel bored and directionless in life.

There seem to be two different settings in the busyness-happiness calculation: first, what your ideal set point is, and second, whether your temporary situation is above or below this optimal set point.

What are Good Reasons to Be Busy?As the authors of the aforementioned study note: we need a reason to be busy. Even if we’d prefer busyness, we don’t just do things just to do them.

The quality of that reason makes a big difference. A very compelling reason can lead to overcommitment if you’re not careful. But if you don’t have a good reason to be active, it can be hard to find enough to do to get to the optimal level. I tend to vacillate between having an exciting project (that also occasionally stresses me out) and having no project and feeling aimless.

Finding a good project to keep yourself busy can be tricky. Just wanting to fill time doesn’t seem to be a good enough excuse.

Goal-setting and planning are vital because they’re the tools we use to find motivating activities. Making concrete improvements to your life may be secondary to the well-being boost of having a reason to be optimally busy.

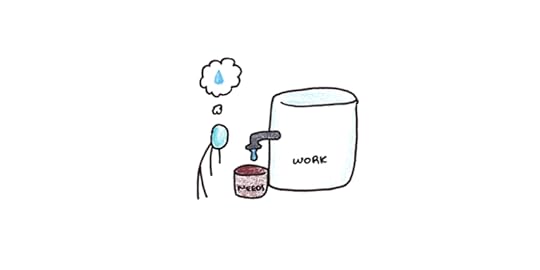

Do You Really Have Too Little Time?Strictly speaking, we all have the same amount of time each day. Nobody has more or less. What feels like a lack of time is, more accurately, a conflict between priorities.

One problematic form of busyness occurs when your activity has low intrinsic enjoyment. If you’re forced to work long hours at a job you hate, then you need to somehow meet your psychological needs in the little time you have left. This can be tricky.

Expectations are another issue. If you intend to work full-time, stay in shape, spend quality time with your kids, and keep up with friends and hobbies, you may find there’s not enough time to do all of those to your desired standard. The result is frustration, even if the hours in the day haven’t actually shrunk.

All of these can make the experience of excessive busyness unpleasant, even if you’re still working with the same twenty-four hours per day as everyone else.

Unconventional Strategies for Optimizing BusynessThere are a few different levers we can pull to optimize the busyness in our lives:

1. Adjust Your Expectations

As I just mentioned, expecting too much from yourself (or too little) is a recipe for stress. Sometimes the key is to take a step back and ask yourself what’s actually realistic. If you’re already at the productivity frontier, perhaps you need to cut yourself some slack.

We rarely feel like we ought to be busier. Instead, this manifests as feeling like we don’t have anything meaningful to work toward. Setting compelling goals can raise expectations and force you to engage in life in ways that make you happier.

2. Find More Satisfying Work, Friends and Hobbies

If you spend a lot of time doing things that don’t satisfy you psychologically, you can feel like you have too little time.

Work can be a major culprit. If you feel like you’re not satisfied with your job, Cal Newport’s book remains my favorite on career satisfaction.

Still, friends and leisure pursuits can also be drains. Do you feel overwhelmingly busy but somehow spend hours binging Netflix or scrolling on your phone each night? Perhaps the problem isn’t a lack of time but a lack of activities that actually meet your needs.

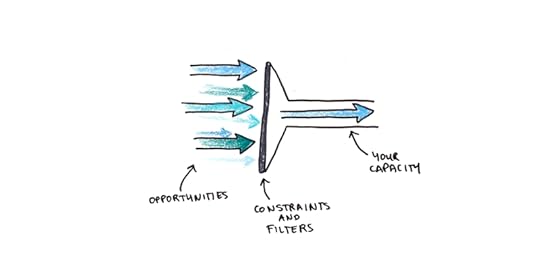

3. Create More Filters and Constraints

Temporarily feeling too busy or bored is often a problem of balancing new opportunities and existing commitments. When the flow of upcoming opportunities is a trickle, we feel restless and bored. When the flow is a torrent, we feel overwhelmed.

Better managing this flow can solve some of the busyness problem. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, tighten up on your constraints so more new opportunities default to “no.” If you’re feeling idle, relax those constraints and start saying “yes” to more speculative opportunities.

Different sources of obligations may need to be managed differently. For instance, while I almost always say no to speaking requests, I usually agree to podcast interviews because the time commitment is much smaller than a prepared speech. Often when we’re overly busy, it’s because a specific source of obligations isn’t being managed correctly.

These strategies tend to be more effective over longer time horizons. Consistently applying the principles above can help you work toward a life of optimal busyness months and years from now. Still, there are fewer remedies for feeling too busy right now. Ultimately, however, finding the right balance of engaging, meaningful activity is one of the best ways we can live better.

The post Is Life Better When You’re Busy? appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 26, 2021

The 10 Best Tools to Stay Mentally Sharp at Work

How can you maintain peak concentration during difficult tasks? (Besides just chugging coffee, of course.)

Staying sharp can be tricky. Even when you desperately need to focus, it can be hard to stop a wandering mind. You might get stuck, unable to push past what ought to be a simple problem. Persisting through these moments of frustration can require a lot of willpower.

Below, I’d like to touch on ten tools I use to stay mentally sharp. While doing so, I’ll shine a light on some of the cognitive science that makes them work.

1. Take “Smart” Breaks

1. Take “Smart” BreaksThere’s nothing wrong with taking a break. Taking your mind off a problem, at least temporarily, can even lead to a breakthrough. When your attention is diffuse, it’s easier to make the longer-range connections you need to solve creative problems.

Checking email or Facebook, however, can make it hard to return to the task at hand. If you need a break, the best strategy is to take “smart” breaks—activities that are unlikely to become an ongoing distraction. Some good ones include:

Briefly meditating or just sitting with your eyes closedGoing for a ten-minute walkStretching or doing push-upsGetting a glass of waterThe idea here is to make the break relaxing, not distracting.

2. Wean Yourself Off Your PhoneWhat makes a difficult task effortful?

One theory says our perception of effort is actually a calculation of opportunity costs. Your brain has a limited capacity for attention-demanding tasks. Focusing on one thing means ignoring something else. It would make sense for there to be a system that discourages getting stuck on low-value activities.

The problem is what counts as “low value.” Sometimes we really need to do something, but it’s not the kind of activity our brain finds naturally rewarding. We need to study, but our brain finds TikTok videos more fun instead.

One way to make hard work less effortful is to reduce the salience of tempting alternatives. If you never work with your phone accessible, the thought of quickly checking social media isn’t nearly as powerful. Creating working spaces or times where distractions aren’t accessible prevents getting derailed and can make the work less effortful as well.

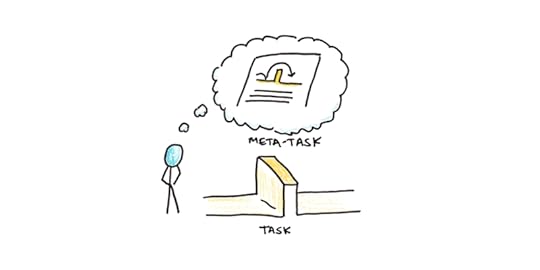

3. Shift to the “Meta” TaskSometimes you get stuck. How can you get out of it?

One trick I like to use I call switching to the “meta” task. Meta comes from the Greek μετα, meaning “after” or “beyond” and indicates a shift to a more abstract layer of a problem. The idea here is if you get stuck in the task itself, you can shift your attention to figuring out why you’re stuck.

Say you’re writing an essay, and you’ve been staring at a blank page for an hour. Switching to the meta task would mean, instead of writing the essay, write about how you don’t know what to write.

This exercise can help you articulate the difficulty you face and find a solution. You might, for instance, recognize that your problem is that you’re worried you’ll write a bad first draft. But then you realize you can always edit it later, so you commit to writing badly and editing later. Alternatively you might recognize that you’re missing a good opening, so you can start writing the middle sections instead. Either way, you’re now un-stuck.

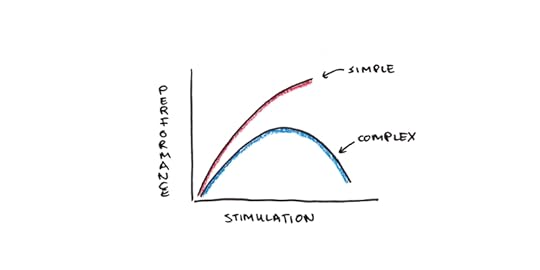

4. Apply the Yerkes-Dodson LawOne of the earliest findings in experimental psychology was the Yerkes-Dodson law, a U-shaped relationship between general arousal and performance. Psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson found that performance suffered when subjects were either too alert or relaxed.

Another finding related optimal arousal to task complexity. Simpler tasks benefited from higher degrees of focused alertness, whereas higher arousal hurt performance for more complex tasks.

What does this mean for your work? One implication is that you need to find the right degree of stimulation to keep you focused. If your attention keeps wandering off, you may work better in a noisier coffee shop than in the library. Conversely, if you’ve already had a third cup of coffee, the library may be better.

Another implication is that more complex, creative work benefits more from a relaxed kind of focus. Even if you’re able to work through simple tasks while under a lot of pressure, lowering your anxiety and stress about a task, say through visualization or meditation, helps with high-performance work.

5. Set Specific, Achievable, Short-Term TargetsEdwin Locke pioneered the study of goal-setting. His research found that specific, challenging goals resulted in higher performance. These did better than “do your best” goals or non-specific targets.

Since then, industrial psychology has generally supported the value of goals in increasing performance. However, there are some caveats:

For complex tasks, a goal-oriented approach may inhibit performance. Maintaining the goal in mind leaves less space in your working memory for exploring the problem. Thus, for novel or frustrating tasks, a playful attitude where you just try things out may be more appropriate.Goals only work if they’re accepted. Giving someone a goal they don’t believe is achievable makes it more likely that they will reject the goal, and thus, it will fail to have an effect.Before any session where you need to focus, clearly spell out what you want to accomplish. Setting a moderately challenging goal you believe you can achieve will help focus your mind in ways that just clocking in cannot.

6. Cultivate an Interruption-Free EnvironmentHow do you stay focused when you constantly get urgent emails from your boss? Your deskmate is loudly typing beside you? Your three-year-old keeps coming to your home office to “ask a quick question”?

The key to improving focus is to negotiate your environment in advance. Most of the time, the people around you would like you to be more productive. The problem is one of communicating what you need and making concessions to keep your relationships smooth.

A boss might be fine with a reply in an hour, provided she knows you haven’t forgotten the new task. Colleagues (and many children) can respect a closed door if they know it means you’re doing deep work. The difficulty is often one of planning the environment ahead of time, not just getting frustrated afterward.

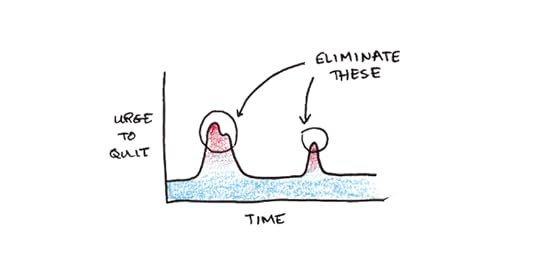

7. Jam Your Quitting TriggersHow do you persist for hours on work that makes you want to quit after only a few minutes? Perhaps it’s working through a difficult assignment, reading a dense manual or finally getting started on a task you’ve been dreading.

One key thing to recognize is that the urge to give up is rarely constant. Even in the most miserable assignment, your actual moment-to-moment mood varies quite a bit. What often happens is that the urge to quit arrives at specific, predictable moments. Identify those moments, and you can use a light touch to defuse them.

Say you need to grind through flashcards to prepare for a test. Every time you get a few wrong in a row, you feel a strong urge to take a break. Instead, set a rule for yourself: I can take a break whenever I get the last one correct. What happens? Now your exit from the task is only after a little positive reinforcement, so it’s harder to simply drop it, and easier to start again later.

Perhaps your problem is with giving up before you begin. Setting a timer for twenty minutes and only letting yourself quit after it dings can keep you in the game long enough to get into a flow. Committing to work for at least twenty minutes is much easier than committing to work for three hours straight, even if it may have a similar effect.

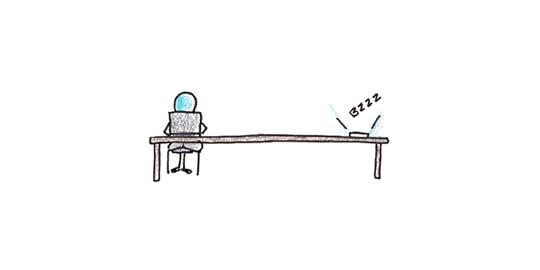

8. Master the Power NapSleep is essential for thinking. With less and less sleep, our mental performance deteriorates. In one study, after losing sleep for multiple nights in a row, subjects thought their fatigue was leveling off, even though their performance kept declining.

While little can replace getting a full night’s sleep, being able to take a nap can help. The key is to avoid getting into the deeper stages of sleep that lead to grogginess later. Roughly twenty minutes is a good length of time for a nap.

As an additional strategy, you can take a coffee nap. Caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors. However, it is less effective if those receptors are already activated. A quick nap can remove some of the adenosine and replace it with caffeine to temporarily improve your mental performance.

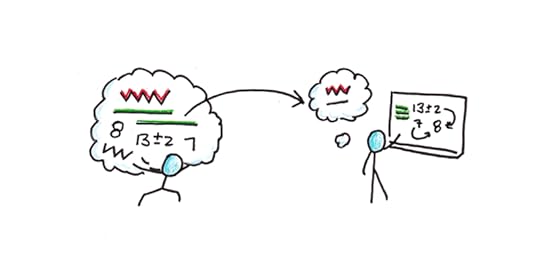

9. Minimize Mental OverheadWorking memory is the psychological concept that corresponds closest to what we think of as mental bandwidth. It’s the things you’re actively thinking about right now. Working memory is in contrast to long-term memory, which is everything you know and remember, whether you’re thinking about it or not.

The critical thing to realize about working memory is that it is limited. George Miller famously pegged the quantity of information as seven, plus or minus two, items. More recent research, however, suggests it may be as low as four items. Compare that to a computer’s RAM, which today can easily store 16,000,000,000 units of information.

One way to cope with limited working memory is to offload what you’re doing onto paper. Writing allows you to externalize your thoughts so you can see new connections. Getting in the habit of regularly writing down your thinking can be a great tool for problem-solving.

10. Don’t Play the Polar Bear GameLet’s play a game. The rules are simple: don’t think about polar bears. Ready, go!

Did you think about polar bears?

Trying to suppress a thought tends to backfire. This effect is known in psychology as ironic processing, originally studied by Daniel Wegner.

Although we recognize the self-defeating nature of the polar bear game, we often slip into the same pattern when it comes to our focus. We attempt a task, notice our mind is wandering and chastise ourselves, “I need to stop daydreaming and work!” Except, this tends to make focusing even harder.

Mindfuness meditation offers a solution. Meditators have long recognized the futility of trying to suppress an unwanted thought. This can be particularly hard when distracting yourself with a different thought isn’t desired either. The solution is to be gentle with yourself. Let the distraction come and go, without getting ruffled.

Some days you’ll feel sharp—the writing will flow, the code will compile and your problems will seem easy. Other days will feel more like a slog. When the latter come, don’t beat yourself up. Just calm your mind and let yourself gently return to the task.

What tricks and tools have you found for getting through tough problems at work? How do you stay sharp? Share your suggestions in the comments!

The post The 10 Best Tools to Stay Mentally Sharp at Work appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 19, 2021

Metrics: Useful or Evil?

Last week I read John Doerr’s Measure What Matters and Jerry Muller’s The Tyranny of Metrics back-to-back. Needless to say, they did not agree.

Measure What Matters is a peppy business book about the importance of setting clear goals and backing them with metrics. Acronyms and buzzwords abound. These sentences, found on page 186, might go down as the most business book-y passage of all time: “Modern recognition is performance-based and horizontal. It crowdsources meritocracy.” The bulk of the book consists of case studies. Doerr argues that, from Bill Gates to Bono, metrics-driven OKRs (objectives and key results) have a life-changing impact.

The Tyranny of Metrics, in contrast, is much more of a downer. It’s a cautionary tale, told not from the manager’s office but from the perspective of the people being managed. Muller argues that a culture of measuring everything is ruining our schools, hospitals, police and politics. When metrics replace judgment, the result is everyone frantically trying to “juke” the numbers. Surgeons avoid high-risk patients to maintain a higher success rate. Schools teach to the test, rather than educate. Police improve crime stats by reporting serious offenses as milder infractions. Instead of “what gets measured, improves,” the slogan of Mulller’s book is, “what gets measured, gets gamed.”

Which Book Was More Convincing?

Which Book Was More Convincing?Reading both of these books was an interesting case in making sense of conflicting advice. Rarely do I get a chance to read books that explicitly contradict one another in such quick succession.

Seen as a debate, Muller’s Tyranny was the more persuasive. But this is a little unfair. Doerr doesn’t make an airtight case because he mostly assumes his readers already believe metrics work. The bulk of the book is spent on getting the details right.

But before I get too meta, let’s dive into the substance of each.

The Defense: A Case for MetricsDoerr’s case is perhaps easier to spell out. Organizations frequently waste effort by pursuing too many conflicting goals. OKRs focus efforts and get everyone on the same page.

By tying goals to measurable results—to metrics—evaluating progress becomes easy. Some companies even use “red” and “green” status lights next to their goals to immediately indicate whether they’re on track or not. As former Yahoo! CEO Marissa Mayer puts it, “it’s not a key result unless it has a number.”

The power of ambitious goals to improve productivity has a long history in industrial psychology. Making the goals public both encourages alignment and makes people accountable for their outcomes.

Doerr, for his part, concedes that it can be problematic when goal-setting becomes an obsession. He mentions the Ford Pinto’s deadly design, where attempts to hit low-cost metrics cost lives and Wells Fargo’s fake account scandal. In both cases, the pressure to measure up to metrics led to ethical pitfalls.

To avoid the potential downsides of metrics, Doerr suggests:

Do not tie metrics to compensation.Be willing to change your metrics if they turn out to measure the wrong thing.When both quality and quantity matter, add more metrics to balance your current ones.Overall, however, Doerr sees metrics as an essential management tool. At the end of the book he helpfully lists some “traps” new adopters of OKRs succumb to. But the list seems more to dispel problems of lukewarm adoption than actual adverse side-effects. The idea that metrics might be gamed isn’t even mentioned.

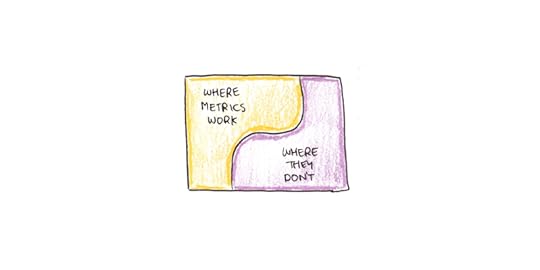

The Prosecution: Do Metrics = Tyranny?Muller isn’t against all measurement. Instead, he’s against what he calls “metric fixation,” the obsession with numbers that leaves no room for qualitative assessment. While this doesn’t leave us with a clear rule separating when metrics work and when they don’t, that’s part of his point. Human judgement, not just data, is needed to make good decisions.

Muller gives a few key arguments:

Tracking many metrics can be costly—and can take away from actual work.When pressured to hit their numbers, people will game the system.Transparency, the need to account for all decisions in terms of public numbers, removes the possibility for professional discretion.Tying metrics to rewards and punishments eliminates the intrinsic motivation that competent professionals have to do their job well.

Muller believes numbers create a deceptive aura of objectivity. It reminds me of a quote I heard once, “Nobody believes a model except the person who built it. Everybody believes the data except the person who collected it.” We tend to think of data as representing objective truth. But it was all categorized, coded, trimmed and tabulated by some guy with a clipboard. Ignoring the qualitative creation of data, we lend it an authority it doesn’t always deserve.

Charities end up worse off from the quest for metrics, Muller argues. Not-for-profit sectors suffer under constant claims for more data, accountability, and transparency because there’s no obvious stopping point. For-profit businesses, however, stop collecting ever-more data when it starts to hurt the bottom line.

Reject, Ignore or Integrate?Faced with such conflicting views and advice, we have a trilemma:

We can reject Doerr’s book as hype.We can reject Muller’s pessimism for failing to offer an alternative.We can try to integrate the two somehow.The first two are the most straightforward answers, and I suspect the approach most would take. Honestly, it’s the approach I typically take. I don’t typically try to reconcile every book written by a doctor with one written by a naturopath—nor do I synthesize every management concept with its Marxist critique. Doing so would be more time-consuming than edifying. Ultimately, we always reject some arguments without a hearing simply because they lie too far outside of our worldview.

In this case, however, I found myself persuaded by both Doerr and Muller. The two books fought valiantly in my mind, even if neither delivered a knockout. That leaves option #3—try to integrate.

Three Strategies of IntegrationThere are several strategies for getting conflicting ideas to gel together. The first is what I’ll call the strategy of non-overlapping magisteria. This is an approach taken by many theologians, to reconcile the transcendence posited by divinity with the seemingly mechanical universe posited by science. If religion and science simply deal with different things, there isn’t any conflict.

In this approach, we accept both arguments are correct but apply in different domains. Muller himself admits he’s not against all measurement, but “metric fixation.” Likewise, Doerr’s title claims we need to “measure what matters”—implying that we ought not to measure the irrelevant. Thus, there appears to be room for compromise.

This strategy might even work. Muller’s critiques focus mostly on not-for-profits, whereas Doerr is concerned with big business (particularly tech). Applying this strategy is complicated a little by both authors claiming the universality of their positions, which would leave us with a stalemate. Neither argument conquers, and we’re left with metrics for tech companies and maybe a little more caution when quantifying police departments.

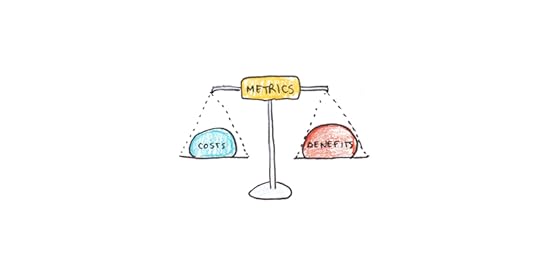

Another strategy is simply to look at trade-offs. Metrics both inspire effort and encourage corruption. They allow for progress on easily quantified goals and may be damaging to more qualitative ones. Like a potent medicine that cures disease and also creates side-effects, each metric needs to be carefully considered in light of the trade-offs.

Trade-offs are a less satisfying answer because they require weighing many possible effects for each individual case. Still, sometimes this assessment is unavoidable. Life is complicated. Why should we expect convenient solutions?

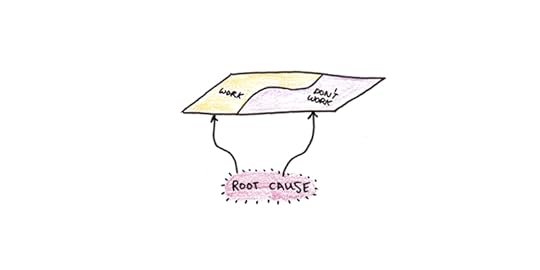

A final strategy is to posit a uniting principle. Maybe the debate about metrics is epiphenomenal to something else. The root cause is deeper and the effects of metrics are merely symptoms.

Muller’s anti-metric examples all point to bureaucratic dysfunction. People try to game their numbers because they’re powerless to push back against them. Doerr’s view assumes that when a metric mismeasures, management is promptly informed, and the strategy is easily adjusted.

This suggests to me that organizations have an internal level of vitality or sickness. Layering goals and metrics on a healthy organization increases effectiveness by aligning people to work toward a shared goal. The same strategy, applied to a sick organization, robs people of the last shreds of autonomy they had to do a job well for its own sake.

Of these three attempts at integration, I’m most inclined to the third, but trade-offs or non-overlapping magisteria might be real too. Culture seems to lurk behind the success or failure of many management approaches in ways that can be difficult to reduce to a particular method or technique. In this sense, metrics are no different from Lean, Agile, Six-Sigma, or any of the other practices du jour. Metrics are a tool for healthy organizations, but get twisted when applied to sickly ones.

The post Metrics: Useful or Evil? appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 13, 2021

What are the Best Arguments Against Doing the Real Thing?

I admire when other authors showcase the best evidence against their position. It’s disappointing to finish a book and find the author ignored a good, well-known rebuttal.

In that spirit, I want to consider some of the best arguments I’ve heard against doing the real thing.

To recap my position: Most learning occurs by doing the thing you want to get good at. Skills are narrower than people think, and transfer is tricky. Practicing the real activity in real projects, real jobs, or for real results is more effective than many substitute or purely preparatory efforts.

The applications of this idea are broad-ranging. Some examples of doing the real thing include:

Taking on projects at work outside your current abilities to advance your career.Pairing study with real-world use through co-op and apprenticeship programs in school.Focus on training what you want to be good at, rather than doing an unrelated activity for the purpose of strengthening mental “muscles.” (e.g. Brain training doesn’t work. Learning programming doesn’t make you a more “logical” thinker. Bilingualism doesn’t make you generally smarter.)Speaking a language instead of tapping through exercises in DuoLingo.Practicing mindfulness in daily life rather than only in seated meditation.Doing homework problems instead of just watching lectures.Here, I’ll be focusing on arguments drawn from cognitive science, instead of practical concerns like convenience or cost. Not because practical considerations don’t matter, but because they’re more apparent. The idea that doing the real thing is harder is obvious; subtle contradictions from a research paper nobody has read are easier to sweep under the rug.

So let’s look under the rug and see what the best arguments I’ve heard against this view are:

1. Discovery Learning Doesn’t Work Very WellPure discovery learning is the idea of not giving instructions at all. Simply present the pupil with the problem situation and let them figure it out for themselves.

Unfortunately, the research seems to be against this.1 Discovery learning is a lot less efficient than telling people what they ought to do and then getting them to do it.

My main takeaway from this research is that instruction matters. If there’s a good method for solving a particular problem, telling students the method is much more effective than leaving them to reinvent it themselves.

This research fits my own experiences. My portrait drawing challenge, for instance, began as pure discovery learning. I would keep drawing portraits until I got better. But my biggest performance gains didn’t come from extra practice; I was taught a better method than what I discovered on my own.

A related issue comes up in language learning. While Vat and I made our best effort to adhere to the “No English Rule” while traveling, this didn’t apply when asking linguistic questions of our tutor. Some language learning purists insist that the student never translate or break immersion, but this always seemed like trying to swim with one hand tied behind your back. If you can easily ask for an explanation and get it, why try to stumble through it?

There are no points for purity, only pragmatism. What matters is that you practice the right skills often and early. There’s no bonus for figuring them out yourself.

2. Cognitive Load Makes Problem Solving InefficientJohn Sweller’s cognitive load theory argues that problem solving is often inefficient.2 His studies showed that students learned to solve algebra problems faster when they were shown lots of examples of solved problems, rather than trying to solve them on their own.3

When we try to solve a specific problem, we need to keep details of our goal and how to reach it in our working memory. This additional cognitive load may interfere with schema acquisition (i.e. learning patterns that may be useful later).

Play may trump problem solving. When working on a problem without a specific goal, the student can try lots of things to figure out what works. In contrast, only one answer is needed to solve a problem with a single goal. A playful, exploratory mindset may map out the patterns of interactions better than a narrowly, solution-oriented perspective.

As an example of this, Sweller asked students to solve some math problems. One group was asked to solve the problems for a particular variable, and the other group was asked to solve for as many variables as they could. The latter group did better later, which Sweller explained in terms of cognitive load.4

These studies reconfirm that being told how to do something is generally more efficient than figuring it out for yourself. Second, they argue that exploratory-style practice may work better than overly rigid problem solving for difficult tasks. I have no quarrel with either statement.

Yet, Sweller’s suggestion to replace all problem solving with worked examples is based on the assumption that we understand what skills are needed to solve the problem.5 This might be fine for algebra with its clearly defined steps, but it seems less applicable to more ambiguous problems. With cooking, for example, we all understand that watching a lot of videos does not make one into a chef.

3. Deliberate Practice Requires More than Just Doing Your JobDeliberate practice is psychologist Anders Ericsson’s theory of expertise. He argues that world-class performers get good through intensive, focused practice sessions.6 These sessions challenge one to build or improve a skill rather than merely “using” it. The quantity of this practice, Ericsson argues, is what separates the best from the rest.

This argument is one I know well. I am a big fan of Ericsson’s work, and he even gave me feedback on my book Ultralearning before it was published. His theory featured strongly in Top Performer, the career course I developed with Cal Newport, and I still reference deliberate practice in my work to this day.

Yet, it was working with students in Top Performer, that I found that the more typical cases often differ from Ericsson’s studies of violinists or chess grandmasters. For someone trying to advance in a big organization, the barrier often isn’t getting a better at the same skill you’ve been doing for twenty years. Instead, progressing in this environment requires developing completely new skills. The programmer becomes a manager. The start-up becomes a big company. New tools and technologies are required for rapid change.

Thus, in some ways, deliberate practice and doing the real thing deal with very different problems. The former suggests you’ve been doing the real thing long enough that you’ve plateaued in your performance and need to make special efforts to get better. The latter argues that you need to find real situations to acquire new, relevant skills to continue your progress.

For what it’s worth, I’ve found that taking on ambitious, real projects that require broader skill upgrades has improved my writing more than drilling specific skills I already have.

4. Theories are Useful, But InvisibleThus far, most of the arguments against doing the real thing could be described as critiques of doing only the real thing. Getting instruction, seeing worked examples, playing instead of problem solving, and even deliberate practice are all activities that naturally dialog with real practice.

Consider, you’re a new programmer and want to get good fast. In my mind, getting a job or working on an open source project is a real activity. It might not be enough, though. You may get stuck because you don’t understand the syntax of a particular function. In this case, reading Stack Overflow code examples is perfectly acceptable. So is watching a video that explains how the function works. These detours may not be direct practice, but they complement direct practice in a way that you’d need a strong ideological commitment to ignore.

While this approach works for specific skills, it may not work if your issue is a failure to understand the broader theory. Suppose the problem you’re having with your code isn’t with a particular function but an overall design pattern. If you’ve never heard of the design pattern, you’re unlikely to rediscover it by chance. However, rarely will your difficulties coding suggest you ought to learn more about the design pattern.

The solution here seems to be to expose yourself to the theory broadly, regardless of your current project. Read books in your field, take classes, and learn theory to glean information that might someday be useful. Since the real situation is unlikely to lead quickly to discovery, or create the cues that a particular theory is needed, this kind of book learning needs to operate in parallel with direct practice.

This hybrid of doing the real thing and explanation feels true to me. It’s a big part of why I like courses and books. I don’t think they can replace direct practice, but neither can direct practice be a complete substitute for studying theory.

Other ArgumentsThis list isn’t exhaustive. Cost and convenience are significant factors, and there’s a trade-off between them and doing the real thing when choosing our approach to learning. Additionally, ill-defined goals make it harder to improve our practice—how do you know what the real thing is if you aren’t even sure what you’re trying to be good at? Dabbling may be a good way of testing one’s own interest in a subject, even if the activities involved don’t contribute much useful practice.

There’s also the difficulty of needing credentials, even if the subjects you study are dissimilar from the work. The “paying your dues” kind of work may be an unavoidable feature of many pursuits. It is fundamentally dissimilar to the end goal, but is needed to signal your commitment.

Despite these difficulties, the deeper I delve into this topic, the more I feel like it has important implications, not just for how we learn things but for everything we pursue.

The post What are the Best Arguments Against Doing the Real Thing? appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 5, 2021

How Becoming a Dad Changed My Thoughts on Productivity

I’ve been writing about productivity for fifteen years. In that time, my life has gone through many changes. I’ve gone to university, graduated, lived abroad, built a business, written a book and gotten married. But easily the biggest shift was the birth of my son, last year.

How I’ve thought about productivity has shifted dramatically. Not just in the obvious ways of having less time and needing to coordinate childcare. But also in deeper ways of what goals are really worth focusing on.

Does Becoming a Parent Make You Wiser, or Just Different?

Does Becoming a Parent Make You Wiser, or Just Different?Becoming a parent is a dramatic shift in perspective. But, not necessarily a privileged one.

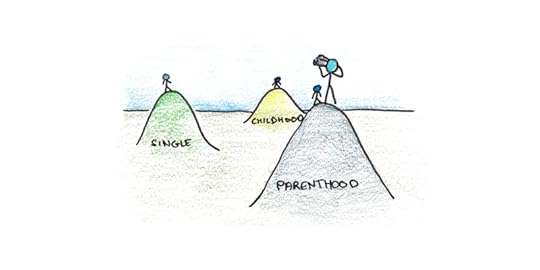

Every stage in life creates unique challenges and opportunities. Current challenges feel acute. Current opportunities feel like priorities. As a result, ones belonging to a past stage of life are often discounted as trivial, simply by virtue of hindsight.

For instance, adults have a hard time taking the problems of kids seriously. You can remember being a child. You may even remember intensely negative experiences. But there’s a whole category of childhood upsets that seem silly to adults. I’m not sure that makes them any less real, just less relatable.

I tend to reject the view that having kids “puts your life in perspective” or some other claim for greater wisdom. It’s probably better to say that having kids gives you a different perspective. My goal in this essay, therefore, isn’t to recant my past views on productivity, but simply to share that new perspective.

Different Constraints vs Different Values

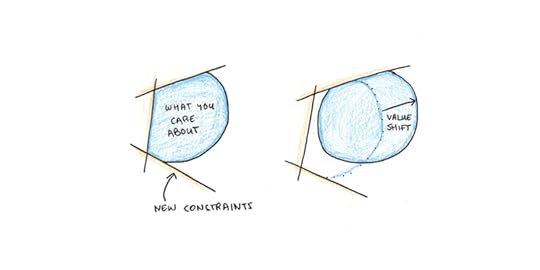

Different Constraints vs Different ValuesPlenty about becoming a parent is imaginable in advance. You have less time. You get fewer hours of sleep. You socialize less. (Although, in the past year, it looks like nearly everyone was doing that last one.)

It’s not always easy to envision how life will be under new constraints, but it is at least imaginable. What’s harder to anticipate is the shift in values. You can imagine losing sleep, but it’s hard to mentally simulate what it will be like not to mind so much.

Much of human behavior is driven by deep, instinctual drives—sex, status, safety, and so on. Even goals that don’t explicitly have anything to do these, often get amplified or diminished to the extent that they indirectly help with those goals. Thus, young people just happen to like being cool and adventurous for their own sake, it just coincidentally assists their dating lives.

Caring for your children is one of these deep, instinctual drives. While it doesn’t replace the ones that you had before, its addition ends up tuning many of the other goals that were suitably “downstream” from your original instincts. Career, socializing, hobbies and exercise all take on subtly different shades of meaning as they filter through these new overarching life priorities.

I suspect this is the reason why there’s a tendency for single people to think parents are boring and parents to see single people as superficial. Each has the internal dials for their basic drives tweaked in a way that renders the others’ life choices perplexing.

How the Meaning of Productivity Changes

How the Meaning of Productivity ChangesThe constraints of parenting make some aspects of work harder and some easier.

The biggest difficulty is simply that overtime is a much costlier strategy when you have kids. In my twenties, when facing a difficult goal, I could always work more as a last resort. These days, my main lever of productivity is carefully choosing what to work on. Since I can’t outwork my competition, I’d better choose my shots wisely.

But being a parent also creates structure. You stop sleeping in, even on weekends. Nights out drinking and extended travel become more difficult, so they interfere less with work. Admittedly, this may be more a feature of my life than others. I’ve always set my own schedule, which is nice, but required more focus to stay productive.

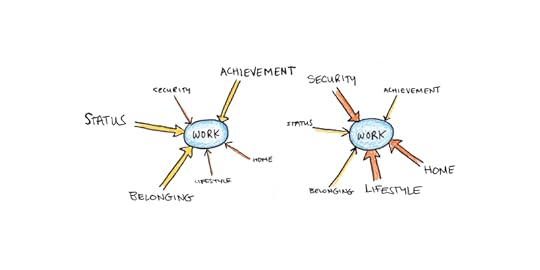

The value shift of parenthood also influences work.

For some, work gets a downgrade in importance. The biggest reason for this is simply time. Kids are a full-time job. Even if you have a supportive partner and childcare, the desire to spend more time with your kids may push you to work less.

For others, work increases in importance. You want to provide for your family, have more living space, invest in their education. Especially if you live in an expensive city, this motivates an ambition that you might have been able to ignore when you were fine sleeping in a small apartment.

Changes in Strategies for Getting Things DoneOn a day-to-day level, I’ve found the strategies I use for work have changed dramatically.

I rented office space. Ironically, after over a decade of working from home, it was in the middle of a global pandemic that I started working in an office. While the original justification was a quiet space to record the podcast, it’s helped me get deep work in too.

Planning has become essential. I used to approach my to-do list with greater spontaneity. This was a good strategy in my twenties, and let me shift according to my mood and energy. If I had a good idea for an essay, I wrote. If I was totally stuck, that was a good time to hit the gym. Now, since I need to coordinate childcare, it’s much better to have a stable routine. If I delayed going to the gym by an hour or two before, that rarely caused major problems. Now, if I miss my slot, it can be really hard to make it up later.

Time is also much more fragmented than it used to be. It’s harder to guarantee long, uninterrupted chunks outside of work. Thus activities that can be picked up for a few minutes and quickly put down again tend to dominate over those that require more depth. Thus, there’s an even greater pull toward checking your phone rather than taking a woodworking class or completing a painting. This greater pull was another reason I felt that going off social media had become necessary.

The biggest change, however, is simply change itself. Children are always changing, and so the way you work around their schedules does as well. Having a son has been the best experience in my life, and I’m sure that it will only become more interesting in the future.

The post How Becoming a Dad Changed My Thoughts on Productivity appeared first on Scott H Young.