Scott H. Young's Blog, page 19

July 25, 2022

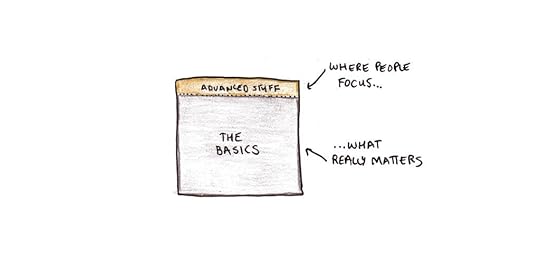

You’re Never Too Good for the Basics

Everyone wants advanced knowledge. But it’s typically the basics that matter most.

Most math is arithmetic, not algebra. Running a business is largely a matter of keeping revenues above costs. Good writing is the product of clear ideas and clean sentences.

I knew someone who was enrolled in a college Spanish class. The class was divided into sixteen weeks, one for each verb conjugation. Most of the time, the most common three or four conjugations are all you really need. What’s the point of studying the pluperfect subjunctive if you can’t speak in the present tense without hesitation?

All skills break down into elemental components–coding has commands, painting has brushstrokes, comedy has jokes. Mastery of the performance results from mastery of the parts.

Obvious, Yet InvisibleAsk yourself what you repeatedly do. What actions do you take every day in your job, your hobbies, your daily life?

We ignore the basics, not because they’re hidden, but because they’re so obvious. We don’t think about how to tie our shoes, drive a car, compose an email or complete routine tasks. Thoughtlessness saves effort but inhibits improvement.

Bringing attention back to the basics doesn’t come automatically. We adjust our habits only when they fail to deliver results.

One way to return to the basics is to change the environment. Skiing down a more difficult slope reveals technique errors not noticeable on groomed runs. Writing for an editor receives pushback you won’t get in your diary. Talking on the phone in a foreign language reveals mistakes you could avoid with body language in person.

Another strategy is to change your goals. When you set a different standard for what you want to produce, your actions must adapt.

Finally, you can find room for improvement by observing and analyzing your work after the fact. Re-read your old code. Videotape your Powerpoint presentations and watch them. Record yourself speaking French and listen to your pronunciation. Our minds operate with a tight mental bottleneck. We can’t simultaneously apply our full bandwidth to performing a skill and also monitor it for improvement. So separate these tasks–examine your mistakes when you’re not in the middle of making them.

What are the basics in your craft? What are you doing to master them?

The post You’re Never Too Good for the Basics appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 18, 2022

Recent Reading: Viking Law, Backgammon Strategy, The History of Alchemy and more…

Viking law, backgammon strategy, how consciousness works, and the history of alchemy. Here’s some of the summer reading I’ve been up to lately!

1. Consciousness and the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene

Dehaene is a leading neuroscientist working to understand the brain events that correspond with our conscious access to information.

This isn’t as mysterious as it sounds. If you flash an image to a person fast enough, they can’t explicitly recall seeing it. Yet those subliminal presentations still enable faster processing of the unseen stimulus when it is presented again. This effect, also known as priming, is just one of a few different strategies neuroscientists can use to provide the exact same stimulus but allow subjects’ conscious awareness to vary. By observing the difference in “aware” versus “unaware” trials, researchers can pin down what happens in the brain when we notice things.

Consciousness results from a cascade. Below-threshold stimuli get partly processed, but their effects are transient and quickly recede into the background. Conscious states, in contrast, get amplified and communicated across diverse areas of the brain, like water bursting from a dam.

2. Mental Models by Philip Johnson-Laird

How do people reason logically? This question has puzzled thinkers for centuries. One proposed answer is that the rules of logic are built into the brain.

Yet, if that were so, why are we so bad at formal deduction? Given that syllogistic reasoning has to be explicitly taught, the idea that there’s a built-in logical “grammar” seems unlikely.

Still, how is it that we do generally reason correctly about situations? Clearly, we’re not totally illogical, even if few of us are Vulcanesque in our reasoning abilities.

Johnson-Laird argues that we reason by setting up models of the questions we’re trying to answer. For example, rather than reasoning on logical sentences themselves, “All humans are mortal, Socrates is human, ergo Socrates is mortal,” we create a mental representation that has some group of people, all of whom are mortal. One of these people is Socrates, and we “see,” by inspection of this model, that Socrates is also mortal.

When we struggle to think logically, Johnson-Laird argues that it is usually because the situation described corresponds to multiple possible models. When this happens, we have to systematically generate and inspect each model. While doable, this is more difficult, and we’re more likely to miss an edge case.

3. The Algebraic Mind by Gary Marcus

Gary Marcus thinks current machine learning algorithms will not lead to human-like intelligence. Coincidentally, I read this book shortly before Marcus and Scott Alexander engaged in a spirited discussion on recent advances in AI.

As I understand it, Marcus’s point is that we know from cognitive psychology that humans can think in terms of abstract rules. For instance, English-speaking toddlers quickly learn that you can add “-s” to most words to make them plural or “-ed” to verbs to use the past tense. This ability is readily generalized beyond examples the child has seen and requires far less input than huge language models.

Neural networks often struggle with abstract rules like this and instead work like a giant lookup table. They can retrieve the “right” answer for given inputs but struggle to extrapolate rules based on past experience. Marcus argues that developing this ability for abstraction in networks will be essential to creating human-like cognition.

4. The Secrets of Alchemy by Lawrence Principe

Reading a book on a failed science may seem like a waste of time. Weren’t alchemists just a bunch of mystics, cranks and crooks? Principe argues persuasively that we ought to take the alchemists more seriously.

Robert Boyle, the father of chemistry, was an alchemist. So was astronomer Tycho Brahe. Isaac Newton spent more time on alchemy than he did on physics. The line between alchemy and chemistry was blurry in the early days of the Scientific Revolution.

I found the discussion of how alchemists communicated, through riddles and allegories, to be fascinating. Compared with our modern, scientific norms of transparent communication and replicable experiments, alchemy seems almost tailor-made to allow misinformation to propagate.

5. The Idea Factory by Jon Gertner

Bell Telephone Laboratories was perhaps the most inventive place to have ever existed. Transistors, cell phones, lasers, fiber optics—and even the theory of information itself—were developed there.

What made the Labs so successful? AT&T was a regulated monopoly. Thus, it faced limited corporate competition, was flush with both cash and constant technical problems, and needed to maintain a do-gooder image to avoid the ire of anti-trust authorities. These factors enabled Bell Labs to employ enormous quantities of engineers and scientists, allow them to work on basic science rather than projects immediately related to turning quarterly profits, and let the early innovations developed there to diffuse widely.

I haven’t seen any comparative studies, but the Bell Labs model seems fundamentally different from the university or government-sponsored models or the industrial labs in the Silicon Valley ecosystem it helped launch.

6. The Math Myth by Andrew Hacker

How important is learning math? Particularly the higher mathematics used by engineers, mathematicians and scientists? Should algebra and calculus be prerequisites for students in fields where they will likely never apply them?

Hacker voices skepticism that universal STEM mastery is what’s needed to educate tomorrow’s workforce. Most people don’t use higher math in their jobs. The decisions about what math we need to teach are generally thrust upon students from a coterie of mathematical elite.

I am sympathetic to Hacker’s view. I believe that knowledge and skills need to be used to be useful. Thus, the idea that people who will never calculate an integral in their professional life must receive high grades in a calculus class to get a degree and then a job seems perverse to me.

In an ideal world, researchers would perform a detailed cognitive task analysis to identify the knowledge and intellectual skills used in a wide variety of professions, avocations, and civic responsibilities. We could then see which skills are the most generally useful and focus on teaching those first, saving the more niche subjects for those who need them for their future specialty or find them interesting.

Instead, it appears to me that broad curricular decisions are made informally. Sometimes this means highly transferrable skills like reading and writing are prioritized. Or foundational knowledge, like what a gene is or how gravity works, is imparted. Yet, equally often, it seems like curricula are picked based on what the highest status people know and love. Math is no exception in this regard.

7. The Creative Vision by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Jacob Getzels

Csikszentmihalyi and Getzels did a longitudinal study of art students. They followed students after graduation and tracked their success throughout their careers. They found that “problem finding,” or the effort spent in finding original problems to ply their craft toward, was correlated with later becoming a successful artist.

My favorite tidbit from this book was that when they asked non-artistic professionals to rate art, the ratings were relatively consistent. Yet, when they asked art experts to rate art, the ratings were all over the place. This seems inconsistent with our usual model of expertise, whereby experience increases experts’ ability to identify higher quality consistently.

8. Complex Problem Solving edited by Robert Sternberg and Peter Frensch

My favorite chapter from this book was by Mary Bryson on problem solving in writing. She observes that, typically, problem solving becomes routine as a person gains more experience. Doctors, programmers, and car mechanics all switch from the deliberate, problem solving process to a fluent, automatic approach to skills with increased practice.

In contrast, writers experience the opposite trajectory. Grade-school writers produce with remarkable fluency. They string together sentences, even though their work is often bad. In comparison, great writers experience notorious bouts of writer’s block as they struggle to produce prose. What’s going on here?

Bryson suggests that the issue is that a writing task can be conceived of as very different problems. Third graders see the problem of writing as “knowledge telling” or simply writing everything you know about a topic until you’ve exhausted that knowledge. Given the same writing prompt, better writers view the problem as one of persuasion, organization, and teaching—all of which are much harder problems to grapple with than simple telling.

I wholeheartedly agree with this assessment. For me, writing today is much, much harder than it was when I started. Yet my early writing was really bad. I think the issue is simply that, as I’ve read and written more, I’ve become much more sensitive to good writing and increasingly aware of how my work often fails to live up to that standard.

9. Seven Games by Oliver Roeder

Checkers, chess, Go, poker, backgammon, Scrabble, and contract bridge, the history of seven games told through the lens of efforts to understand their computational structure.

The book covers the evolution of the games in order of complexity. Checkers, with only a single piece of each type and a simple set of moves, was “solved” not that long ago, and now a perfect strategy is known. This is not so for the other games, each of which introduces new complexity: hidden information, randomness, time dependency and cooperation.

I enjoyed this book, even though many of the topics were familiar to me. A good read if you’re interested in how games work.

10. Legal Systems Very Different From Ours by David Friedman, Peter Leeson, and David Skarbek

How did early Icelanders maintain society without rulers or police? What keeps the Amish society stable—yet separate from American influence? How did pirates enforce order among outlaws? In this fascinating survey, the authors explore what the law looks like when you don’t have police, courts, or even a legal code to uphold.

Friedman and colleagues do a good job presenting alien-seeming legal traditions as rational solutions to coordination problems in different societies. Far from seeing practices like blood money or feuds as barbarism, they argue these practices represent ingenious solutions that work reasonably well in practice.

Feud systems, embodied by the dictum “an eye for an eye,” seem like they would devolve into endless repetitions of revenge. But in practice, Friedman argues, they usually avoided further violence by ensuring fair compensation and thus resolution of conflict. If I started a fight with your brother and took out his eye, I had to pay you an amount so that you’d prefer the money to taking *my* eye. This practice allowed enforcement within clans and close family, who could monitor their members closely, and prevented violence from escalating by allowing ritualized compensation.

The post Recent Reading: Viking Law, Backgammon Strategy, The History of Alchemy and more… appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 12, 2022

Maximize Your Learning Time with These Seven Habits

Time for learning can feel like a luxury. After a long day, it often feels like there isn’t energy for anything other than watching television and falling asleep. Who has time to learn philosophy, French or painting?

Yet our peak experiences come when we expand our thinking. Without learning, life is stale.

Below are seven practices that can help you make the most out of the limited time you have to learn new things. If you make them automatic, you’ll substantially increase the amount of new and interesting stuff you can do—without needing heroic efforts.

1. Always have at least three books with you.A major barrier to reading more books is not having interesting reading material at hand. If you don’t have any books that you’re excited to finish, you can go months without reading a page.

A simple strategy here is simply to always have a good book with you. I suggest you have three: one ebook on your phone (or Kindle), an audiobook, and a physical book.

Audiobooks are good for commuting, exercising or waiting in line. Digital books can be downloaded to your phone and ensure that you have something to read at all times. Hardcover books give you the joy of paper at your fingertips when you get a longer moment to sit down.

Above all, keep the books interesting. If you have more than fifteen minutes and the thought of filling them with reading feels unpleasant, you’re reading the wrong books. Get ones you can enjoy and build the habit of reading first.

2. Keep a course open on your browser tab.In addition to having your three books, find courses that interest you on YouTube and watch them during your computer breaks.

Keeping a course open in a tab in your browser or having a highly visible bookmark gives you access to something interesting to watch whenever you have some downtime at your computer. I have a list of some of my favorite courses here.

As with book recommendations, I suggest starting with more entertaining courses and switching to headier stuff once you’ve built the habit. Crash courses, for instance, are faster and more visually dense than many recorded classroom lectures and thus hold your attention more easily.

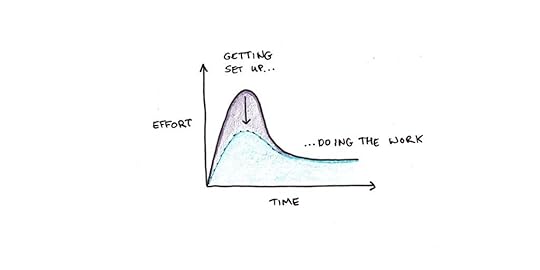

3. Make your projects ready to start.Books and courses aren’t the only way to learn. Hobbies and skills require hands-on experience. Unfortunately, time spent tinkering is often the hardest to fit into a busy life.

One way to maximize your time here is to ensure all your projects are ready to start. If you can manage it, create a dedicated workspace, so all you have to do is sit down and get to work. If you can’t set aside a physical area, organize your materials to keep setup and cleanup time to the bare minimum.

Physical setup is just one aspect of making projects ready to start. The other is getting a project past the “blank canvas” stage, which is often frustrating. A computer program, painting or woodworking project is easier to keep working on once the groundwork has been laid. Getting projects to a level where you can easily putter away at them is pivotal.

4. Take on work projects beyond your current level.Finding completely discretionary free time is hard. If you are busy at work and have kids or other responsibilities, all you might have are fragments of time throughout your day.

Work itself can be a potent source of learning, but we sometimes need to push for it. Generally speaking, clients and employers want consistency, not growth. They want you to work on tasks you’ve already mastered. While many pay lip service to continuous improvement, bottom-line considerations often lean more toward stagnation than growth.

One strategy to inject more learning into your life is to regularly pursue at least one task or project that is speculative. This should be something outside of the range of your current abilities in an area you find interesting. It could be a new technical skill, leadership role, or exploring a different kind of client or industry.

Opportunities for this kind of work vary enormously, but they come only to those who seek them. If you push for learning, you’ll find it.

5. Cultivate friends with shared interests.Intellectual discussion groups have long formed the bedrock for scientific and social progress. Benjamin Franklin’s junto enabled him to discuss educated topics and organize for his community. The loose association of thinkers that made up the Invisible College led to the Scientific Revolution.

Discussion groups can come in many forms. You can be like Franklin, and organize a group among your friends interested in a topic. Alternatively, you can join pre-existing groups on services like Meetup to discuss topics you care about.

In many cases, our difficulties finding time for learning aren’t a literal lack of time—but a lack of a meaningful context for what we learn. We’re social animals. When our activities feel isolating or useless, they’re quickly sacrificed to the pursuits more likely to win us friends or solve practical problems. If you care about learning, build it into your social circle.

6. Fill time fragments with flashcards.Many skills have a forbidding reputation. We find the idea of speaking another language romantic, but the actual act of striking up a conversation in a foreign language terrifying. We want to learn a new programming language, but sitting down and writing code is a complete grind.

A method known as pretraining can break down the difficulty of these pursuits. In this strategy, you first master the basics so that applying the new skill becomes much smoother.

Flashcards are one way to do this kind of pretraining. Memorizing vocabulary, on its own, is not enough to learn to speak another language. But it can give you a foothold so that it becomes much easier to learn (and enjoy) conversations. Similarly, memorizing syntax and commands in a new programming language won’t make you a proficient coder, but it will make completing your next project much easier.

Flashcards have the distinct advantage that you can make them for your phone and practice them during small chunks of downtime. It is hard to learn anything too elaborate in this kind of fragmentary time, but it’s perfect for bite-sized practice.

7. Have a “stretch” book by your bedside.Reading before falling asleep is another great way to expand your learning time. It’s also a time to try reading harder books. Since these are usually works that require some mental effort, they’re also the ones that will more speedily put you to sleep.

Pick a book you’ve always wanted to read, but perhaps have felt intimidated by, and keep it at your bedside. You might want to read a classic work of fiction like Paradise Lost, a challenging nonfiction book or a book with personal significance.

The last moments of the day are also perfect for making a consistent ritual out of reading. The consistency makes it easier to form a habit than the more chaotic background that emerges throughout the day. Ending the day with a book can be a meditative activity to settle the mind before sleep.

What strategies do you use to maximize your learning time in a busy life? Share your ideas and suggestions in the comments!

The post Maximize Your Learning Time with These Seven Habits appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 5, 2022

The 85% Rule for Learning

Learning, it seems, is optimized for both humans and machines when we succeed around 85% of the time. From a recent paper by Wilson, Shenhav, Straccia and Cohen:

In many situations we find that there is a sweet spot in which training is neither too easy nor too hard, and where learning progresses most quickly. […] For all of these stochastic gradient-descent based learning algorithms, we find that the optimal error rate for training is around 15.87% or, conversely, that the optimal training accuracy is about 85%.

If you’re always successful, it’s hard to know what to improve. If you constantly fail, you won’t learn what works. Only when we have a mixture of success and failure can we draw a contrast between good and bad strategies.

These findings agree closely with the 80% success rate found by Barak Rosenshine in his study of successful classrooms, despite coming from a completely different theoretical background:

In a study of fourth-grade mathematics, it was found that 82 percent of students’ answers were correct in the classrooms of the most successful teachers, but the least successful teachers had a success rate of only 73 percent. A high success rate during guided practice also leads to a higher success rate when students are working on problems on their own.

The research also suggests that the optimal success rate for fostering student achievement appears to be about 85 percent. A success rate of 85 percent shows that students are learning the material, and it also shows that the students are challenged.

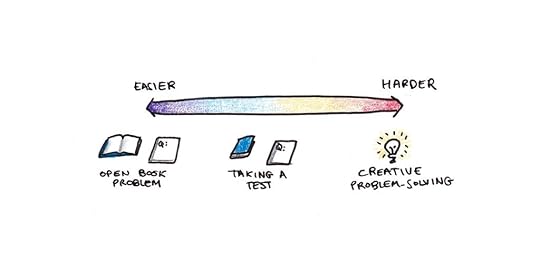

How You Can Apply the 85% RuleImagine you’re studying for a test by doing practice problems. You can apply different amounts of support to calibrate your success rate. The easiest way to solve the problems would be to do them with an open book and worked examples or solutions in front of you. The hardest way to solve the problems would be to work novel problems under test-like conditions with the book closed.

The 85% rule suggests that you should fine-tune the amount of support you use depending on the success rate you’re experiencing. If you’re getting more than one out of every five problems wrong, you might want to add extra help. If you’re getting nearly all the problems right, it’s time to up the difficulty.

In many skills, tasks can be graded on a scale of difficulty. Piano pieces have levels assigned to the challenge they pose. Ski slopes are ranked from green to double black. Language practice can range from simple greetings to rapid-fire debate. The 85% rule suggests growth will be maximized when we practice tasks we can succeed at roughly four-fifths of the time.

The exact percentage may vary between tasks. Reading in a foreign language likely requires understanding closer to 95% of the words to not be maddeningly frustrating. John Pasden has an interesting demonstration of how varying levels of English comprehension feel.

Of course, part of the quantitative ambiguity is that “success” can be defined in various ways. A failure to understand 20% of the words in a text isn’t 80% comprehension, but closer to 10%. Similarly, if you approached skiing so that you crash 20% of the times you go down the mountain, you wouldn’t make it very far without injuries.

Still, I think the rule offers a fairly good heuristic. If you succeed in every attempt, you probably don’t have the difficulty high enough to improve. If you fail most of the time, you will likely make more progress if you start picking smaller, more manageable challenges.

Explanations for the 85% RuleThere are many theories of optimal learning that all point to a sweet spot for difficulty—not too easy, not too hard.

Lev Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development argues that tasks slightly beyond what we can do by ourselves, but can do with assistance from others, maximize learning.

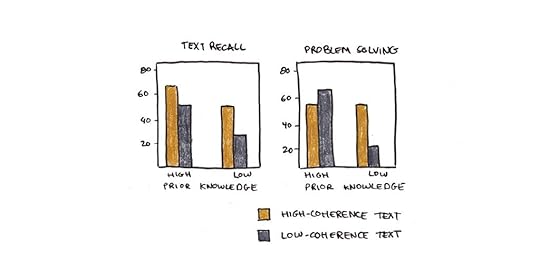

Walter Kintsch’s zone of learnability provides a similar account for text comprehension. In one study, subjects read one of two versions of a text. The first text was written to maximize understandability, with full explanations and subtitles signaling the text’s organization. The second text was written without these aids, requiring students to use inferences to understand the text’s meaning.

In tests asking questions directly from the text, both high and low background knowledge students did better on the coherent text. However, when given a test that required inference or problem solving, the students with higher background knowledge did better than students with less background knowledge when interpreting the less coherent text.

Adapted from Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition by Walter Kintsch

Adapted from Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition by Walter KintschThese results fit a model where, if a text mostly says things you easily understand, you don’t invest much effort into creating a mental model of what the text describes. In those cases, greater difficulty might be beneficial since the struggle it creates forces you to retrieve background knowledge. (This only works, of course, if you have knowledge to retrieve!)1

Anders Ericsson’s model of deliberate practice argues that when skills become automatic, we plateau at levels of ability far below our potential. To counter this, we need to return to the deliberate phase of learning. We can do this by picking harder tasks or setting higher goals for performance.

Robert Eisenberg’s theory of learned industriousness suggests difficulty plays a role in motivation as well. In an experiment, one group of subjects was given hard puzzles to work on. Another group was carefully matched to this group, given an easy puzzle for each question the first group got right, or an impossible question for each one the first group got wrong.

The two groups thus experienced the same success rate, but had very different expectations about the role effort played in success. For the first group, hard work often paid off. For the second group, it never did. On a subsequent puzzle task, members of the first group persisted longer than those in the second group, suggesting that they had learned to work hard at this kind of puzzle.

Learned industriousness suggests that success on hard problems can be good for us, but failure is demotivating. Once again, a difficulty sweet spot emerges where we work on problems we’re likely to succeed at, but are hard enough to encourage effort in the future.

What skills are you working on? What’s your current success rate? Should you be increasing the difficulty or finding ways to reduce frustration? Share your thoughts in the comments.

The post The 85% Rule for Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 28, 2022

The 10 Best Books on Productivity

Productivity forms the backbone of any self-improvement effort. If you can’t organize your time, accomplish your tasks and complete your projects, what chance do you have to reach any other goal you’ve set for yourself?

At the same time, few topics are so frequently misunderstood. Overwork is often equated with productivity. Burnout, stress and exhaustion, it is argued, are all symptoms of our cultural obsession with productivity. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Productivity is about getting more from less. How might you increase the efficiency of your hours, so you don’t need to work late to get all your work done? How can you manage your to-do list stress-free, confident that everything will be done on time? How do you hit your targets without endless grinding?

Below are my picks for the ten best books to help you begin:

1. Getting Things Done by David AllenWhen I started writing online, productivity was virtually synonymous with Getting Things Done. To have a productivity blog meant you were one of Allen’s acolytes, newly converted to the cult of productivity.

The devotion is well-deserved. When recommending books on productivity, I always start with GTD.

The central idea of GTD is that you shouldn’t rely on your memory to keep track of your tasks. By creating a system for capturing, processing and reminding yourself of the work that needs doing, you can save precious mental bandwidth for doing the work, not just thinking about it.

2. Deep Work by Cal NewportLong, unbroken periods of focus are essential to productivity. The reason is simple: the brain was not designed for multitasking. Every time you interrupt a task, you lose focus and must restore the active state of the problem you are working on to your conscious attention. This takes time.

While an inattentive mental state may be okay for emails or Slack chats, it is devastating for complex problems—the most valuable ones to solve.

Unfortunately, our environments have made focus harder than ever. Social media and smartphones offer ever-present temptations for distraction. Open office plans, non-stop Zoom meetings and collaboration over email make scarce the conditions needed for deep work. This is why deliberate efforts to cultivate focus are so important.

3. The Effective Executive by Peter Drucker“Effective executives,” Drucker writes, “do not start with their tasks. They start with their time. And they do not start out with planning. They start by finding out where their time actually goes.”

Drucker, who famously coined the term “knowledge worker,” is responsible for introducing many of the bedrock ideas of productivity. Track where your time goes. Ask what you can contribute. Focus on your strengths. Drucker’s advice remains timeless a half-century after it was written.

4. Work the System by Sam CarpenterSam Carpenter was struggling. He had an unprofitable business and worked eighty-hour work weeks to barely keep up. Like many entrepreneurs, he solved his problems by working more, by grinding, and the problems kept piling up.

Carpenter’s transformation came from shifting his view from doing the work to working on the systems underlying the work. By creating sets of procedures and policies for handling routine work, he greatly diminished the amount of time he spent putting out fires. Eventually, this enabled him to expand his business significantly while putting in a fraction of the work.

5. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen CoveyCovey’s bestseller integrates the ideas of personal character and effectiveness. In Covey’s mind, being effective in one’s work is not merely a product of being rational or efficient. Instead it is taking responsibility for your actions, doing what you say you’ll do, and seeking to understand other people.

Covey sees our development as a continuum from dependence to independence to interdependence. We start out dependent on others and gradually gain self-sufficiency. Being independent isn’t enough, however, as we need to grow to become interdependent with others to become fully mature.

6. Atomic Habits by James ClearHabits are the underpinning of nearly any successful productivity system. Repeated efforts become easier, and consistent actions drive results.

The psychology of habit building can be deceptive. A behavior that requires a lot of willpower today may seem automatic after you’ve done it ten, twenty or a hundred times. Simple routines can often snowball into bigger accomplishments if you consistently put in the work.

Clear’s four rules for habit building (make it obvious, attractive, easy and satisfying) work well for setting up any new working rhythms.

7. Essentialism by Greg McKeownEverything you add to your life pushes out something else. Every thirty minute habit of exercising, meditating or keeping a journal owes its existence, by the simple fact of the 24-hour clock, to thirty minutes previously used for something else.

Every addition requires a subtraction, but this often isn’t obvious. When adding new things, we often don’t explicitly account for what must necessarily be removed. Usually, this means we balance our time on an ad-hoc basis, not by deeper evaluations of what we value.

In Essentialism, McKeown encourages us to think of productivity the other way around. Focus first on eliminating the unnecessary. Keep and protect what is worthwhile, rather than trying to endlessly add more and more.

8. The Checklist Manifesto by Atul GawandeWhen it comes to medical innovations, we tend to think of high-tech implants or exotic pharmaceuticals. However, sometimes more basic interventions can have dramatic effects.

Surgeon Atul Gawande argues that simple checklists can lead to dramatically better patient care, on average, by preventing doctors from accidentally missing important checks and steps.

Gawande concludes that most of us would benefit from creating checklists to track routine tasks where we might forget something. Packing for a camping trip? Use a checklist. Going on an international vacation? Use a checklist. Completing a task at work? Check to make sure you’ve done everything first.

9. The Power of Full Engagement by Jim Loehr and Tony SchwartzWe should treat our work the way athletes treat their training: cycles of focused engagement, followed by rest and recovery. Energy, not time, is our most limiting resource and needs to be optimized if we can be both productive and fulfilled.

Loehr and Schwartz argue in favor of four dimensions for our energy to work:

Physical. The energy we get from sleeping, healthy eating and regular exercise.Mental. Concentration and attentiveness.Emotional. The capacity to manage emotions skillfully and constructively.Spiritual. The energy that comes from having a deep purpose in your work and life.Full Engagement had a lot of influence on my early thinking about productivity. I saw it as an antidote to the tendency to equate productivity with working non-stop, often under conditions that weren’t sustainable.

10. Flow by Mihaly CsikszentmihalyiFlow is the enjoyable state of mental absorption in a task. To be in a state of flow, your activity must be neither too difficult nor too easy. When tasks are too hard, we break out of the autonomous flow state and find the activity frustrating. When tasks are too easy, our mind wanders as the activity does not demand our full concentration.

Flow also offers a unique rationale for productivity. As flow is central to our well-being and happiness, work that can produce a flow state is not just something to get done, but is itself intrinsically valuable.

Not all work can be flow-producing. Some amount of frustration and boredom is inevitable. But, by understanding the factors that produce effortless productivity, we can better craft our working environment and diagnose and recover from the mistakes we make when doing so.

The post The 10 Best Books on Productivity appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 21, 2022

You Should Pay for Tutors

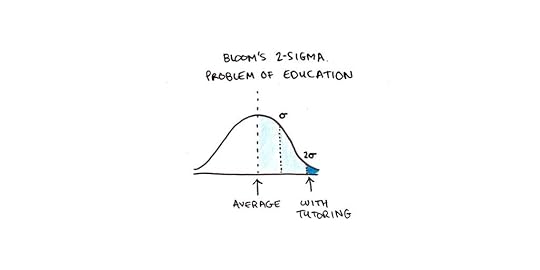

One-on-one tutoring is one of the most effective ways to learn anything. In his famous paper on the “2 sigma problem” in educational research, Benjamin Bloom called for a search for group teaching interventions that approximated the efficacy of tutoring:

However, the most striking of the findings is that under the best learning conditions we can devise (tutoring), the average student is 2 sigma [standard deviations] above the average control student taught under conventional group methods of instruction.

…

This is the “2 sigma” problem. Can researchers and teachers devise teaching-learning conditions that will enable the majority of students under group instruction to attain levels of achievement that can at present be reached only under good tutoring conditions?

Bloom later argues that mastery learning, the idea that students should fully master prerequisite knowledge before moving on to later subjects, comes close to this ideal. However, a simple conclusion can be drawn from this work: tutoring is quite effective, and we all should be using it more.

What is Tutoring Good For?

What is Tutoring Good For?One myth about tutoring is that it is essentially only for “slow” students. This was the response from a reader when I suggested tutoring might be effective for learning academic subjects. He saw tutoring as a response to some kind of deficiency, something for kids who couldn’t properly learn in class and had to use it to catch up.

Some of this myth may simply be an abuse of language. “Tutoring” is what we give to students needing extra help. “Coaching” or “mentoring” is what give to those being groomed for elite performance. Yet there doesn’t seem to be a functional difference between the terms.

Intellectual skills are just as amenable to coaching as are physical ones. Terrence Tao, widely considered to be the most brilliant living mathematician, was tutored heavily from a young age. Here is a photo of him at ten with the legendary Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdos.

Nearly every elite performer in chess, music, medicine, business and elsewhere had enormous quantities of coaching support. Tutoring is far from remedial. Instead, it’s the secret sauce of top performance.

What if I Can’t Afford Tutors?Price is the big objection to tutoring. Admittedly, this can be a real cause for concern. The cost of one-on-one instruction was a major reason Bloom formulated the 2 sigma problem, to see if cheaper means of achieving tutored-levels of efficacy were possible.

Yet, there are many reasons to believe tutoring is underutilized, even for its cost.

For starters, tutoring is often free. Many universities have free tutoring services available. Be sure to check if your school offers academic assistance. You’ve already paid for it with your tuition, so a failure to use it can’t be blamed on a lack of resources.

Even if your school doesn’t have free tutoring programs, most classes have office hours with professors or teaching assistants where you can ask questions. This is a great opportunity to maximize the value of your studying time so that you can clear up misconceptions and confusion.

Finally, tutoring needn’t be extensive to be valuable. If you’re an organized student and study well independently, you can still use tutoring for the problems you can’t get through on your own. I argue in favor of the Feynman Technique to work through difficult conceptual hurdles and find the holes in your understanding. Still, even here, you need to get clear explanations once you’ve identified those questions. Tutoring is an excellent way to do this.

Tutoring, Beyond SchoolProfessionals could use more tutoring than they realize. Having access to high-quality feedback on your work is essential for growth. Yet most of us labor away with minimal guidance or development.

About a year ago, I decided to start working with an editor when writing blog posts. I came to this decision after having worked with one when writing my book. Beyond correcting typos and fixing sentences, I found that working with an editor made a big improvement in the quality of my writing.

Yet I think we avoid tutoring in our working lives for much the same reason we avoid it as students. Help is what the poor performers need. I know what I’m doing, so why bother?

As I grow older, I’ve become increasingly convinced that the attitude required for learning is not confidence but humility. We stop learning not because we don’t believe we can learn but because we think we already know what is best.

The post You Should Pay for Tutors appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 14, 2022

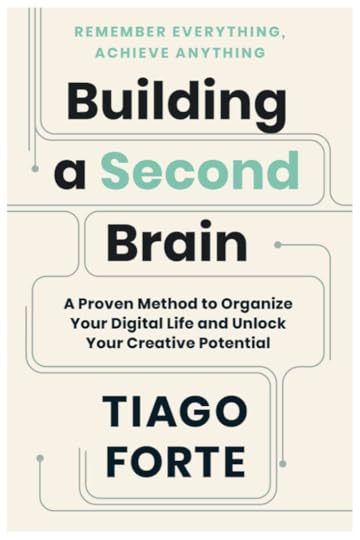

Interview: Building a Second Brain with Tiago Forte

How often have you read a book, taken a course or listened to a podcast and . . . promptly forgotten everything the minute you switch your attention to something else?

Being able to retain what you learn is a central difficulty in our era of information abundance. Too many great ideas get wasted, simply because we forget them when we might need them.

Tiago Forte’s new book, Building a Second Brain, details one strategy for dealing with this problem: taking better notes. I recently sat down with Tiago to record an interview about his methodology, which he has been refining for years through his popular website and courses.

Building a Second Brain is a great complement to Ultralearning. Given the overwhelming learning challenges we all face, we need every tool at our disposal to master it.

Watch on YouTube.Listen to the full interview on my podcast.Read the transcript as a PDF.Highlights from Our Conversation

Watch on YouTube.Listen to the full interview on my podcast.Read the transcript as a PDF.Highlights from Our ConversationOn the importance of recognizing when an item on your to-do list is really a project:

Tiago: People really underestimate how much what they think is ‘a single task’ is really ‘a project’ . . .

If there’s anything that is stuck, that you just can’t seem to get started, you can’t seem to make progress on, it’s very likely that thing is not a ‘task,’ it’s a ‘project.’ And once you realize it’s a project, you have to step back and create some structure.

Why you need a system for organizing your creative work. Just sitting and waiting for inspiration won’t work:

Tiago: I just can’t sit down every day at a ‘blank’ anything; a blank desk, a blank screen, a blank canvas, and invent how I am going to approach my work that day. I need a process. I need a system. And what CODE does is it gives me steps. C = Capture more information, O = Organize the information, D = Distill the information, E = Express information.

How to collect the right amount of information:

Tiago: For note-taking, when you collect everything, you might as well collect nothing. When you try to save all the knowledge, you end up not having any knowledge that’s accessible. If you save everything you end up just creating a huge amount of work for your future self to organize, distill and review and boil down that to its essence.

The importance of completing projects:

Tiago: What makes the biggest difference to people’s lives, their careers and their businesses is “completed creative projects.” To me, that is the unit of progress that is most relevant in today’s modern world.

Building a Second Brain is a well-written useful book, and I highly recommend people check it out!

The post Interview: Building a Second Brain with Tiago Forte appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 9, 2022

No, You Haven’t Forgotten Everything

If I made you take the final exam for a class you studied a decade ago, would you pass?

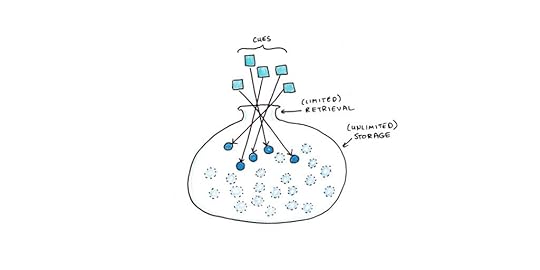

The unfortunate truth is that, except for knowledge we actively use in daily life, much of what we learn is beyond our powers of recall. But that doesn’t mean it has been erased from our memories.

Why We ForgetEarly theories of forgetting were based on decay. These theories assume unused memories fade with time like the yellowing of a photograph. The idea has some intuitive plausibility. Physical atrophy withers the body, so why not the delicate connections that store our thoughts?

Yet, the theory of decay is not the whole story. As psychologist Robert Bjork comments:

“Thorndike’s original law of disuse, of course, stands as one of the most thoroughly discredited of the various ‘laws’ psychologists have put forward over the years—which is a considerable distinction.”

Interference from other memories is another major factor in forgetting. Retrieving a memory is an active process. You need to search for a specific memory based on cues you have consciously accessible. As you acquire more memories, more and more of them become associated with familiar cues. It becomes harder and harder to retrieve any particular memory.

This may seem like a defect, but it’s actually a feature. Memory is only useful if we retrieve the right memories at the right times. Recalling the right memory requires both retrieving the correct option and suppressing all competing alternatives. Otherwise, our waking life would be a dreamlike flood of irrelevant and dissociated thoughts—hardly a sound basis to make intelligent decisions.

Forgetting Can Be Good for Learning

Forgetting Can Be Good for LearningThe adaptability of memory goes further. If a memory turns out to be surprisingly useful—i.e., we retrieve it despite barely remembering it and find it to be the answer we want—the memory becomes much easier to recall than if it was easy to retrieve.

This is the basis behind Robert Bjork’s concept of desirable difficulties. We benefit more from remembering something when the cues that bring up that memory are weaker. Thus testing beats re-reading for studying, spaced practice beats cramming and mixing up problem sequences is better than doing them in batches.

This desirable difficulty isn’t a design flaw. It underpins a highly sophisticated selective recall strategy. If information is only relevant given highly predictable stimuli, that itself is a signal not to retrieve the stored memory in other contexts. Useful retrieval in contexts where the cue is not obvious suggests the memory needs to be more broadly accessible.

Another implication of this theory is that storage and retrieval become dissociated. A memory could be highly learned, and thus well-remembered, but unretrievable. You could detect this by giving another learning trial, in which case the memory becomes learned much faster a second time.

The Power of RelearningAfter years of absence from studying a topic, it’s common to feel you’ve forgotten everything. Forgetting can be embarrassing or frustrating as you realize that you can no longer do things you had previously mastered. Yet is this correct?

Research on memory suggests otherwise. Relearning tends to be much faster than initial learning. And thus, even in extreme cases where the entire class seems unfamiliar, you still acquire the skills faster in a second passage.

I’ve experienced this with many of the skills I’ve learned. It can be painful to attempt a conversation in a language I haven’t practiced for months. I had a similar frustration trying to grasp calculus when I decided to study quantum mechanics after several years of mathematical quiescence. In these cases, there can be a pang of doubt: did I even really learn this in the first place?

Even so, relearning is something to celebrate, not to be embarrassed by. The mistake isn’t having forgotten, but in letting a temporary drop in ability keep you from learning again.

The post No, You Haven’t Forgotten Everything appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 25, 2022

Do You Learn More by Struggling on Hard Problems?

Suppose you’re learning a skill like algebra, programming or drawing. Consider two different strategies for studying:

Examples first. Before you try anything on your own, study examples of how other people solve similar problems.Problems first. Before looking at any examples, try to solve the problem independently. If you fail or don’t get very far, then learn how others approach it.Which strategy works better?

Although this sounds like a simple question, it’s hotly debated. Entire books have been written with researchers on each side arguing which works better. Like me, I’m sure you have some intuitions about this—after all, you’ve spent a lot of time learning things. Which do you think would work better?

Examples First: The Power of Direct Instruction

Examples First: The Power of Direct InstructionThe intuition behind seeing examples first is obvious. Nearly every problem is easier if someone shows you how to solve it first.

Two bodies of research back this up. The first is Direct Instruction (DI), an instructional method developed by Siegfried Engelmann and others. DI starts by breaking complex skills into atomic components and carefully illustrates these components with examples before giving students lots of practice on those pieces. When students fail to learn, DI assumes the problem is usually with the lesson, not the student.

Studies of Direct Instruction are largely positive:

Project Follow Through, the largest-ever educational experiment performed in the United States, compared various teaching programs and found that Direct Instruction performed best.Since then, countless studies find Direct Instruction improves student performance, particularly for weaker students.John Hattie’s Visible Learning, which reviewed over 800 meta-analyses in educational research found that positive effects of Direct Instruction were among the largest of interventions that have been studied systematically.The other significant body of evidence for this approach is cognitive load theory, which I reviewed in-depth here. The worked-example effect finds that novices learn more from studying solutions than solving problems themselves.

The value of examples-first is highest in the beginning phase of learning. As students gain more experience, they benefit more and more from practicing on their own. This “expertise reversal” effect implies that what works best depends highly on the student’s prior experience. For this reason, strategies like Direct Instruction switch from giving examples to providing practice as classes move on.

Problems First: Can Failure Be Productive?The intuition behind solving problems first is also self-evident: how can you learn to solve problems yourself if you are always told exactly how?

Researcher Manu Kapur argues that students learn better if they first experience “productive failure.” The idea here is to have students work in groups on a difficult problem. Not knowing how to solve it, they will most likely fail. After this experience, they are offered examples and instruction and given a chance to try again. Kapur’s research finds productive failure beneficial in a range of experiments.

Along similar lines, Dean Schwartz and John Bransford advocate for students to try to invent a solution before being told the best approach. They argue that such experiences foster greater transfer, by allowing students to experience trying to solve a problem before being taught the best method.

Theoretically, there are a few reasons we might suspect a problems-first approach works better in some cases:

Activation of prior knowledge. If you already have some knowledge of how to solve a problem, directly trying to solve it will force you to try to retrieve that knowledge. This may make integrating a taught solution easier.Conceptual understanding. Seeing a problem first may make it easier to understand the conditions where the solution applies. This may assist later transfer to similar problems in different contexts.Motivation and engagement. Students may tune out if they only study worked examples. In contrast, it’s impossible to solve a problem without cognitively engaging with the material. Active learning has benefits in controlling attention.Which Side is Right? Does It Even Matter?Having read way too much material covering this debate, I can confidently say that I have no idea which approach is better. However, the winner here matters less than some might believe.

For starters, it’s abundantly clear that both practice and instruction are necessary for effective learning. Advocates of Direct Instruction make ample room for practice after seeing examples. Studies that support a problem-first approach still require that the student is eventually shown the correct answer.

Thus, we can immediately rule out extremes. Pure discovery learning, where students are never shown instructions or examples, fails miserably. In a classic example, students who spent considerable time on LOGO programming practice without instruction still did poorly on simple problems. In light of these results, researcher Richard Mayer argues that there should be a “three strikes” rule against unguided learning.

Similarly, learning requires practice. As psychologists Herbert Simon, John Anderson and Lynn Reder remark, “Nothing flies more in the face of the last 20 years of research than the assertion that practice is bad.”

Regardless of the optimal procedure—either see an example, then do practice, or attempt a solution, then see the example—both ingredients are necessary.

Designing Your Practice Loop

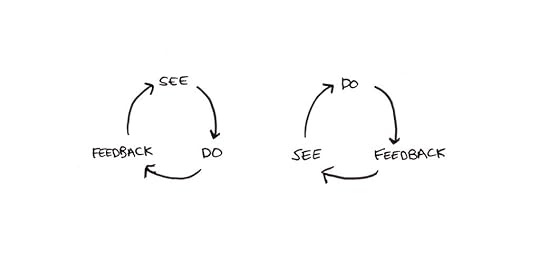

Designing Your Practice LoopRecently, I shared a post where I argued for See->Do->Feedback as the backbone of any learning strategy. I got a few objections from readers who contend that you short-circuit the struggle in solving hard problems when you see examples before attempting a solution. Isn’t such grappling necessary for learning?

The difference between See->Do->Feedback and Do->See->Feedback, however, may not be significant. If the process is indeed a loop, you’re continuously cycling back and forth between seeing examples and trying it for yourself. The timing and sequencing are things you can tweak as you go along.

Early on, struggle may help you get a sense of the problem, but you’re unlikely to arrive at the best answer spontaneously. In that case, difficulty can become undesirable. Even if you can figure out how to solve a problem, you may still benefit from seeing an example. Work in cognitive load theory suggests that studying the “correct” example is beneficial because it helps you learn the general pattern for solving that type of problem.

Later, as the material gets more manageable and you become more comfortable with it, there are increasing benefits to learning by problem solving. You already have more knowledge in your head, so you’ll get the advantages of trying to retrieve that knowledge when formulating a solution. Also, practice is the only way to build fluency in the component skills used in solving the problem.

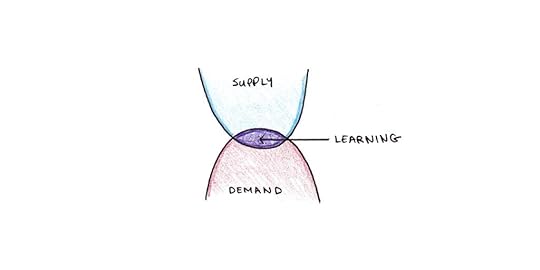

Learning: Supply and DemandI think the constellation of research I’ve reviewed here supports the idea that there are two distinct points of difficulty in learning:

Failures of instruction. When instruction is omitted or insufficient, students struggle.Failures of initiative. Without active engagement by the student, lessons may be wasted.

I like to imagine this as a meeting of supply and demand. For learning to happen, there must be a sufficient supply of knowledge to make successfully acquiring skills possible. At the same time, if there’s no demand to use that knowledge learning is often superficial.

Problems of knowledge supply come when you’re trying to “wing it,” attempting to find reasonable solutions to problems when you don’t feel like you have the right training. In these cases, seeking out good mentors, peers, or even structured classes can be powerful if your aim is more than “good enough.”

Problems of knowledge demand come when you consume information and never use it. Collecting cookbooks instead of making meals. Buying a phrase book rather than speaking a language. Watching videos on YouTube instead of doing the real thing.

The best thing you can do to improve your learning is to have all three ingredients: instruction, practice, and feedback. If you’re lacking one of these, ask yourself how you might seek it out and structure it into your efforts to get better. Only when you have access to all three does it make sense to fine-tune the sequence.

The post Do You Learn More by Struggling on Hard Problems? appeared first on Scott H Young.

May 10, 2022

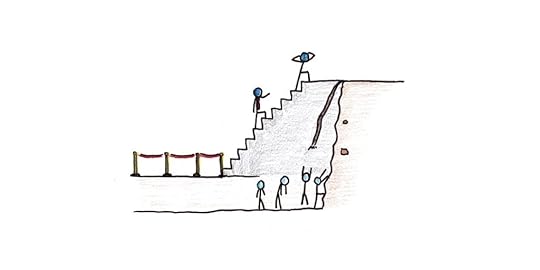

Book Review — Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs

Pedigree is an eye-opening book. Author and sociologist Lauren Rivera looks into the recruitment practices in elite law, banking, and consulting firms. Rivera’s unsettling portrait provides much ammunition for those who would argue that meritocracy is a myth.

In particular, Rivera finds:

Alma mater is all-important. Elite firms draw from “core” and “target” schools. Students from core schools are wooed aggressively by firms. You might squeeze in from a target school if you’re near the top of your class. Everyone else might as well not apply.Extracurriculars matter more than grades. Firms sought out applicants with interesting and impressive leisure activities. Those who had perfect grades but studied too much were “nerds” and generally excluded. Working on the side to pay for college was also penalized as it failed to demonstrate “intrinsic” motivation.Firms prioritized “fit.” Ostensibly, fit refers to the ability of new recruits to integrate smoothly into the corporate culture. In practice, it usually just meant that the applicants were similar, culturally and socially, to the person interviewing them.Minorities were held to a higher standard. Men would often get a pass for math mistakes. In contrast, these were seen as proof of low quantitative ability in women. Black applicants were often rejected for lacking polish, but the same behavior in white applicants was seen as fixable with coaching. Stereotyping could cut both ways; for example, dramatic “rags to riches” stories could be a selling point. Yet, if minority candidates’ performance activated a negative stereotype, it could lead to immediate rejection.Mastery of subtle class signals was essential. Many qualities required applicants to navigate a delicate and hard-to-fake balance between two extremes. They should neither be arrogant nor meek. They should be active conversationalists while never talking over the interviewer. They should tell personal stories but keep them professional. Those socialized into the American upper class strike that balance intuitively, but it can feel unnatural for non-Americans or those from the working class.She concludes that hiring depends much more on signaling class status than cognitive skills. Elites put their thumbs on the scale to help their own. Everyone else gets left out. Yet it is rationalized as simply a neutral quest for finding the best.

Understanding How the Game is Played

Understanding How the Game is PlayedThis portrait mirrored my own experiences attending a decidedly non-elite business school.

I grew up in a small town. My parents were teachers, so we weren’t working class, but most of my friends were.

I chose the same local university my parents attended. I didn’t bother applying to faraway, elite schools. I didn’t know anyone else who did, and I figured the material taught would be essentially the same anyway.

The recruiters Rivera studied would equate this choice with moral failing. Recruiters assumed students always went to the best possible school they could attend because that’s how the game is played. Failure to attend the best possible school was always a sign of either insufficient ability, ambition or both.

Once enrolled, I decided to attend business school. Naively, I thought it would help with starting a business, even though most classes are for middle management jobs.

Again, I made the error Rivera associates with working classes—assuming education is about gaining knowledge rather than signaling your intellectual and class pedigree.

In business school, I witnessed an attenuated version of the class signaling Rivera describes. Many extracurricular activities were seen as more important than classwork, and I overheard more debates about tailoring than academics. Students’ sartorial choices were commented on, and those (usually less affluent) students who wore ill-fitted suits or the wrong tie-shirt combination attracted ridicule.

This isn’t to complain about my school experience as a whole. I had a fun time in college, and later events have certainly been kind to me. Yet Rivera’s description felt uncannily familiar.

How Much Do Skills Matter for Success?Given that my personal history seems to corroborate Rivera’s account, why do I emphasize learning as a path to career improvement? Rivera’s recruiters didn’t seem to think mastery of academic materials mattered much. Elite credentials and upper-class leisure pursuits seemed to matter more.

Even so, there are a few ways to salvage the role of acquired mastery:

Recruiters ignored grades because the students had already crossed a high bar to get into the schools they recruited from. Further scholastic achievement has diminishing returns once you’re already at the top of your class. As one recruiter described the work students did in these firms, “it’s not rocket science.”Professional services rely more on social skills than technical skills. It would be intriguing to pair Rivera’s account with recruitment at elite engineering firms. I suspect mastery of skills would matter more in engineering simply because the skills required for superior performance are much harder to pick up solely on the job.Academic knowledge is overrated. Some skills are best learned in school, but others must be learned through practice. Some of this might be because the latter are highly specific and thus vary from job to job. Some of it might be because the skills are inherently interactional. In these cases, real work experience is required, and academic simulations have limited usefulness.Elite professional service firms seem to operate according to the same principles as luxury handbags. Clients pay exorbitant fees for first-year law associates, not because they’re brilliant legal theorists, but because they lend prestige via their elite schooling and upper class socialization.

While nice, the material properties of the leather Hermés uses to make its handbags is not why they cost tens of thousands of dollars. Similarly, it isn’t the acquired cognitive abilities of students that make them expensive in elite firms. That said, it would be a mistake to conclude that material properties never matter to apparel companies or that skills are unimportant to all employers.

How Do Skills Matter?Despite these qualifications, Rivera makes some key points about the ways skills matter:

Skills and signals are intertwined. Employers can’t see an employee’s productive potential until hiring and training them. Instead they rely on proxies: credentials, interview cases and professional polish. Making improvements in your professional life isn’t merely about acquiring new skills—it’s also about finding effective ways to demonstrate those skills.Acing a job interview and being an ace in your job may have surprisingly little overlap. Most recruitment strategies are informal and imprecise. Countless studies attest to the relative worthlessness of interviewing for predicting employee potential. Employers think they can spot talent, but they’re probably kidding themselves.Cultural know-how matters more than you think. Figuring out the “rules of the game” is difficult, because they’re rarely stated and the best players think they’re obvious. But understanding these rules early can have enormous dividends. Rivera notes one Indian applicant who was stellar, but didn’t realize how important extracurriculars were in American recruiting. Joining intramural groups late in college didn’t count as the intensive commitment that signaled intrinsic motivation to recruiters. She didn’t get the job.All of this, to me, suggests that skills need to be viewed in a proper context. You should have some good reason to think a skill matters before pursuing it to help your career. Knowing the rules of the game you’re playing can help you decide whether a skill investment is likely to pay off.

The Irrelevancy of UnfairnessThe intended reaction to Rivera’s book is one of concern, pessimism and maybe even disgust. It’s hard to read without feeling that the game is rigged, and perhaps we’d all be better off if people had nothing to do with it. It certainly didn’t inspire me to seek a banking job.

But that feeling is somewhat beside the point. Every field has its own structures of success and gatekeepers who throttle access. There will always be some skills that matter and some that don’t. Hidden rules of play are treated as obvious by those who succeed but poorly understood by those outside. Wherever you are, if you want to play, study the game.

The post Book Review — Pedigree: How Elite Students Get Elite Jobs appeared first on Scott H Young.