Scott H. Young's Blog, page 16

February 7, 2023

Learning, Fast and Slow: Do Intensive Learning Projects Work Better Than Slow Ones?

Say you want to learn French. Would you do better if you studied for 100 hours in a year-long course (~2 hours per week) or if those hours were compressed into a month (~20 hours per week)?

Surprisingly, the answer seems to be that more intensive language education programs do better! This appears to be a fairly consistent research finding, in the dozen or so studies where the comparison has been made. From a paper by Raquel Serrano and Carmen Muñoz:

[We] analyze the performance of adult students enrolled in three different types of EFL programs in which the distribution of time varies. The first one, called ‘extensive’, distributes a total of 110 h in 7 months … ‘semi-intensive’, which offers the same number of hours distributed in 3–4 months … intensive course offers 110 h in 5 weeks … The results from our analyses suggest that concentrating the hours of English instruction in shorter periods of time is more beneficial for the students’ learning than distributing them in many months.

The research is surprising because the spacing effect is one of psychology’s most robustly replicated effects. Essentially, when material is presented repeatedly, spread out over time, it results in enhanced memory compared to repeated presentations in short succession.

What’s Going on Here?When I stumbled into this research a couple weeks ago, it surprised me! If any research result felt solid, it was the spacing effect. While the spacing effect and the seeming superiority of intensive language instruction are not necessarily incompatible, they’re definitely in tension.

Here are some speculative explanations for what might be going on:

1. Spacing makes learning harder, sometimes too hard.Spacing is one of the “desirable difficulties” that increases efficacy at the cost of short-term performance difficulties. However, added complexity can sometimes flip the expected benefit of these desirable difficulties.

Contextual interference, for instance, tends to be helpful, but it can backfire for complex skills or poorer students. Similarly, retrieval practice tends to be helpful—unless the person can’t retrieve what they’re trying to remember. These results suggest that the optimal studying technique for complex skills changes over time, starting with massed/blocked/review, and shifting to spaced/interleaved/retrieved presentation.

Given that most people in language classes do not leave with conversational fluency, it may be that the complexity of language learning interferes with the expected benefits of spacing.

2. Spacing of individual items is independent of overall classroom intensiveness.A leading explanation for the spacing effect (although hardly the only one) is that spacing works because massed practice results in deficient processing of repeated information. When you see the same vocabulary word multiple times in a row, you stop paying attention to it. In contrast, when the same word comes up at spaced-out intervals, you attend to it fresh each time since you can’t easily recall it from memory.

It’s possible that in the time frames studied, individual items of vocabulary and grammar are being spaced out just fine in the intensive programs, so the efficiency gains of the extensive schedule are not observed.

3. Intensive classes are more motivating (or attract more motivated students)Perhaps the results aren’t cognitive at all—it might simply be that a more intensive class is more enjoyable, motivating, or results in a better classroom experience. Serrano and Muñoz cite one study that evaluated qualitative performance from intensive/extensive studying schedules and found the intensive classrooms had better group cohesion and motivation. (Then again, this result would also make sense if the students were learning better.)

In arguing for my intensive language immersion bursts, I similarly relied on a non-cognitive argument. I’ve found that the habit of speaking a particular language quickly becomes entrenched when meeting new people, which is often the case when traveling abroad. Since English is widespread, there’s a tendency to default to speaking English even if you study enough to converse in the new language. This motivated the “no English” rule that Vat and I employed while traveling.

4. Perhaps the tests weren’t delayed enough.Alternatively, perhaps this research is just a red herring. Maybe the extensive groups would perform better if the comparison of the intensive/extensive training was five years out. A well-known consequence of the spacing effect is that massed presentations tend to be more effective initially, but their advantage typically fades over time.

Nonetheless, given that we often enroll in a French or Spanish class aiming to be able to have conversations now, rather than mildly better non-conversational ability in half a decade, these research results can’t be ignored.

Rethinking Spacing?As someone who has made a show of taking on big, intensive projects, I have often been at least mildly embarrassed by the dissonance between the time frame of those projects and my repetition of the usual advice to space out studying to perform better.

But perhaps there’s less tension than I originally thought. It appears that studies of actual classroom language learning seem to weigh more in favor of the approach I’ve intuitively preferred—working through an intensive burst to get to semi-conversational and then following that with periodic review, rather than studying in twenty-minute daily sessions from the get-go.

Rather than over-adjust my current advice, two things seem to hold:

Spacing for individual items is still central. Things like flashcards with spaced reviews, programs like Pimsleur or DuoLingo that encourage review of previous units, or even revisiting old classroom exercises are likely beneficial. Spacing should be applied within a studying program, even if the advice for the overall intensity of the schedule is less clear.Intensive projects should be followed by more leisurely maintenance. Even if an intensive burst can get you quickly to proficiency, it probably makes sense to continue to practice at a more leisurely pace for months or years after if you don’t want that proficiency to decline too abruptly.Reading this research has made me curious about the effects of intensive versus extended curricula for other subjects. Do those in programming bootcamps forget more than their college counterparts who spread CS classes over four years? Is an executive MBA worse for management thinking than one taken over a couple years? I don’t have any answers, but I’m curious in light of this unexpected research.

The post Learning, Fast and Slow: Do Intensive Learning Projects Work Better Than Slow Ones? appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 31, 2023

Curated Consumption: A Saner Approach to Online Media

Two years ago, I decided to get off social media.1 Twitter made me anxious, and Reddit and YouTube ate up all my time. Undoubtedly, it was one of the best decisions I’ve made. The problems that pushed me off these platforms have only gotten worse.

However, I’m a profoundly online person. I still spend considerable time reading and watching things online. My entire livelihood is anchored on this blog that I started seventeen years ago. The prospect of spending all my downtime reading paper books by candlelight, while holding a certain romantic appeal, isn’t realistic.

The solution that works for me is to switch from letting an algorithm decide what content you consume to a curated newsfeed.

Why RSS Remains the Best Technology for Online MediaSetting up a curated newsfeed is easy:

Get yourself an RSS Reader. I use Feedly.Add the blogs and websites that you want to follow. This includes social media accounts. RSS works for YouTube, Instagram, Twitter or old-fashioned blogs like this one.Read and enjoy!Instead of an infinite stream of content designed to maximize your gut-level reactions to attention-hijacking thumbnails and rage-inducing headlines, you just read the stuff you’ve subscribed to.

Too much content? Mark it all as read and reset your feed. A seemingly interesting source turns out to be a dud? Unsubscribe. You can even create folders to separate your personal, work or other interests.

Curating is a Little More Work, But Far Saner Than the Status QuoWhy am I suggesting a return to 2005-era technology? Didn’t the market decide that RSS was a failed technology, with Google Reader discontinuing service and companies shifting to attention-consuming algorithmic content feeds?

As with fast food, our impulses are not always our friends when it comes to online content. The things that easily take root in our mental gardens are not generally what we intend to cultivate.

Content curation is only slightly more work than using an algorithm. It requires you to opt into new sources manually. It also requires regular pruning to avoid having too much content. New content is somewhat harder to find (although if you follow a few aggregator blogs, like Marginal Revolution, this isn’t so difficult.)

What’s difficult is weaning yourself off the algorithmic feeds. Modern feeds work perfectly as a Skinner box on a variable reinforcement schedule: the content is mostly junk, but the occasional gem keeps you pecking the button for more. But if you can navigate the transition, a curated feed is a much saner way to consume online content.

The post Curated Consumption: A Saner Approach to Online Media appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 24, 2023

Why Do People (Usually) Learn Less as They Get Older?

I was recently a guest on a podcast where the host asked why people are less interested in learning as they get older.

While there are certainly exceptions, the observation seems valid. Nearly all formal schooling is concentrated in our childhood and early adulthood. Stories of people going back to school in their twilight years are newsworthy precisely because this is rare.

It also fits with my informal observation that people are much more reluctant to pick up new skills or topics as they get older. I learned to downhill ski at thirty, but I only personally know a few people who began much older than I was.

This is a worrying trend. Learning is an integral part of the good life, so if forces make it harder (or less desirable) to learn, it seems like it would be helpful to understand them. Let’s consider three theories, and see what they suggest we can do about defying the trend.

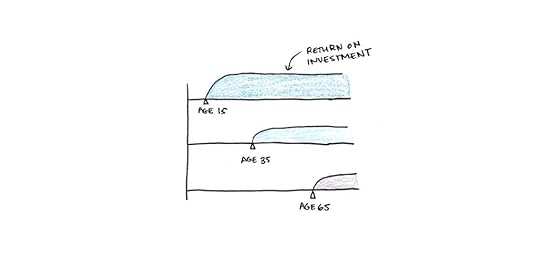

Theory #1: Opportunity Costs and Investment HorizonsThe first explanation is economic: learning is an investment. As you invest in some skills, but not others, you get a greater return from activities where you have considerable training. Thus, your opportunity cost for learning new things increases. Therefore, a failure to learn new things is perfectly rational, even if it can result in inflexibility as we get older.

One way this manifests is the time horizon you have to recoup an investment. A twenty-year-old presumably has forty years for a career to earn back an arduous training period. A fifty-year-old only has ten. Therefore, younger people should be able to make longer, riskier investments than those who need them to pay off quickly.

Another way this can occur is if investment in one skill makes time spent on new skills comparatively less attractive. If I have zero knowledge of programming and accounting but equal potential ability, then the two are roughly the same for me. In contrast, if I have a decade of programming experience, then an hour spent programming will be much more valuable than an hour spent learning accounting. The economy incentivizes specialization, even if we’d prefer to be more well-rounded.

Theory #2: We’re Too BusyAnother explanation for dwindling curiosity is that life gets busier as you get older. I feel this acutely today. When I compare my schedule now, with a toddler at home and a business that employs multiple people, I feel far more time-constrained than when I was in my twenties.

Learning new things takes time. While efficiency can help, the time cost for even well-designed learning may be prohibitive for busy professionals with kids.

Energy may matter even more than time. If you work full-time at a mentally-demanding job and have responsibilities at home, you may not have the energy needed to invest in a cognitively-demanding project. Binge-watching Netflix may not be where you’d ideally like to spend your time, but it makes sense if you feel chronically exhausted.

This also helps explain why there can be a sudden urge to learn after retirement. With kids gone and work stopping, people finally have the time to engage in learning projects they were sidelining during their career.

Theory #3: Older Minds Can’t Learn as WellThe most popular explanation I hear for declining education is that when you’re older, your brain simply can’t absorb new information as quickly.

There is a grain of truth to this. Fluid intelligence peaks in your early twenties and declines afterward. However, the decline is gradual and minimal. The research I’ve seen seems to indicate that it’s only a serious problem in advanced age. Even then, there is high variance, with some people becoming senile and others experiencing few issues.

That said, age is often an advantage to learning. Older people are usually more responsible and organized, which assists in sticking to a project. Also, accumulated knowledge can make learning easier. Your past experience can be a huge benefit when delving deeper into subjects you’ve previously studied or related fields.

Overall, I’m less convinced that age per se is a significant factor, even though it is oft-cited.

How Can We Sustain Learning Lifelong?Given the possible theories, I think there are a few things we can do to continue learning:

Reduce the effort for learning. Always carry a book with you. Set up your environment so learning projects can start and stop on demand. Pick projects that overlap with career, social or parenting goals so you can justify the time investment.Set aside time for experiments. Straightforward calculus suggests that doing what you’re already good at has the best payoff. But you won’t encounter nearly as many opportunities if you never learn anything new. Setting aside time for hobbies you’re bad at, books you know nothing about or skills you’ve never practiced may seem wasteful, but it’s a good practice to avoid getting stuck in a rut.Shift your focus away from skills that involve quick wits to those that rely on accumulated knowledge. The decline in fluid intelligence is overrated as an explainer for learning difficulties. And also, there’s a reason why groundbreaking mathematicians skew younger than historians. Shifting to knowledge-intensive subjects seems like an overall sound strategy.Above all, however, I think losing interest in learning is a choice. For every trend, there are exceptions. With the right attitude, you can be one of them.

The post Why Do People (Usually) Learn Less as They Get Older? appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 17, 2023

How My Views on Learning Have Changed Over Time

I’ve been writing this blog for almost seventeen years. From nearly the beginning, learning has been a central theme. Initially, as a college student, “how to study” was pretty much the only topic I could credibly offer advice on, but my interest in the subject of learning has endured.

However, the disadvantage of such an early start is that my naive opinions are encased in the amber of my archives. While some of my early ideas were outright bad, more often, they contained a mix of useful ideas and unhelpful suggestions.

With this post, I’d like to clarify how my thinking has changed over time. Not to undo my past writing or to claim my current views are final, but to help explain why I changed my mind about some of the things I believed in the past.

Early Views: Holistic Learning and Learn More, Study LessMy first popular writing came from an observation that successful students seem to deeply understand subjects by linking them together. In contrast, less successful students attempt to memorize things by rote. I called the successful strategy “holistic learning,” and my earliest work centered on it.

None of this writing was grounded in research. That isn’t to say all opinions need a citation to be valuable, simply that I wasn’t basing any of my thoughts on a careful review of the scientific literature. Instead, I derived most of my advice from personal experience and reading other popular studying advice.

Having read more deeply now, I often see parallels to my thinking in formal research—even though I relied on none of this research when these topics were central to my advice. Mental models have inspired considerable research. The associative character of memory that fascinated me resembles spreading activation models of declarative memory. My idea about mental constructs is similar to schema theory.

The philosophy I espoused was essentially a version of constructivism—the idea that students construct meaning and ground understanding of abstract ideas in prior knowledge. In this view, it’s the active effort students expend in creating an understanding that leads to learning, an effort often stifled by drills and memorization.

What I Got Wrong in My Early ThinkingSome of the central pieces of advice I gave during this period included:

You should avoid memorizing ideas; instead you should seek to understand them.Concepts can be understood through analogies, mental pictures and diagrams.Connecting ideas together is a central activity of learning.None of these are exactly false, but I wouldn’t make any of them central today. They all suffer from some problems:

Memorizing is often a necessary step to learning complex ideas. Understanding is better than rote memorization alone, but understanding itself relies on memory.Analogies are great learning tools, but they suffer from a bootstrapping problem. It’s hard to notice analogies unless you already understand the deep structure of an idea. Lacking that, attempts to make analogies often result in superficial mnemonics or buggy concepts that can actually mislead! As a result, I now typically advocate people make metaphors when they’re ready, but first, focus on directly understanding an idea through close reading and seeking explanations.Declarative memory is associative, so making connections is a central activity for learning. However, making any old connection is not the most efficient way to learn something. Instead, seeing lots of examples and getting lots of practice questions is probably a better way to make connections while avoiding misapplications of ideas.Overall, the worst advice I gave was discouraging repetitive practice in favor of associative memory. My view on this is the opposite now. I believe associative strategies like mnemonics should be supplementary to retrieval practice, such as flashcards, rather than the reverse. Practice questions should be the cornerstone of studying, not a crutch to be avoided.

While it’s been interesting to see some of my initial intuitions about learning reflected back by Gestalt psychology or Constructivist thinkers, I don’t think I can take too much credit. Instead, I think I based my intuitions about learning on the same observations that inspired both the cultural Zeitgeist that made my early writing popular and also more serious research.

What I missed was that the process good students use is essentially what everyone does when learning subjects they find easy. When you’re learning hard things, and understanding doesn’t come easily, practice and memorization aren’t things to be avoided but essential building blocks toward deeper understanding.

Maturing Thoughts: Learning Projects and UltralearningAfter college, I embarked on a series of learning challenges: MIT’s computer science curriculum, multiple languages, art and more. These culminated in my 2019 book, Ultralearning.

This period spans nearly a decade, and thus my thinking during the MIT Challenge was quite different from when I had finished the research for Ultralearning. But, some consistent themes emerge.

One is the importance of practice. Unlike the conceptual understanding central to my undergraduate education, the cornerstone of my further learning efforts was practice, practice, practice.

During the MIT Challenge, I found practice problems to be the most effective tool for prepping for difficult exams. In my language learning odyssey, I spent nearly all my time practicing through conversations, flashcards and grammar books. With portrait drawing, I based my model of learning almost entirely on repetitive practice, to such an extent that I neglected learning more effective methods until almost halfway through the project.

This emphasis on practice is reflected in the research I did for Ultralearning. I wrote chapters on Directness, drawing upon the extensive research showing that people frequently fail to transfer skills to new areas; Drill, inspired by the work on deliberate practice showing effortful, targeted efforts at improvement are essential; and Retrieval, built on the robust literature showing that memory strengthens more from recall than review.

Mistakes Made in My Maturing ThoughtsHere I think my track record is much better than my early thinking. If I had to go through and edit Ultralearning again, there’s not much I would rewrite.

However, I think my focus on self-directed learning blinded me somewhat to the distinct challenges it poses.

First, I emphasized practice and de-emphasized examples and explanations. Part of this was because students have much less control over the latter. Some classes have tons of practice problems with worked out solutions. Some have almost none. Students generally don’t have much choice over which they have to take.

Second, following my interest in deliberate practice, I tended to view harder learning as more efficient. A cornerstone of the argument in Ultralearning was that greater efficiency came from more strenuous efforts. This view has some support: Bjork’s work on desirable difficulties, retrieval practice and others all lend some suggestion that students slack off to their own detriment.

But while practice is good, examples are too! Watching other people perform a skill, especially with explanations for their decisions, is central to learning well. Similarly, while effortful practice is often necessary, not all effort is worthwhile. I now believe a lot of student struggles are wasteful—failures of instructors to provide thorough examples and explanations rather than a sign that deeper learning is taking place.

Recent Adjustments: Direct Instruction and Cognitive ScienceSince Ultralearning, I’ve delved far deeper into the science of learning. I collaborated with Jakub Jilek, a cognitive science doctoral student, on three research reviews on long-term memory, working memory and self-control. Afterward, I did a solo research project into motivation.

More recently, I’ve done a wide-ranging research project that has exposed me to the main currents in educational and cognitive psychology. Through this effort, I now feel well-versed in the history of different theories, current controversies and the main arguments and research used to support different opinions.

Reading this literature has made me more supportive of Direct Instruction for learning. DI is a teaching philosophy that involves breaking down complex skills into simple concepts and actions, teaching with ample examples and practice. Critics accuse it of being mindless, much like I criticized rote learning in my early days. I now see this as its strength: when learning can occur without requiring exceptional cleverness, far more students will benefit, not just the brightest.

I now believe that practice difficulty comes in different flavors. Some difficulty is due to retrieval—you don’t know which knowledge to bring to a problem. In this case, the research seems to support the idea that moderate difficulty is better. We want problems easy enough that we’re typically successful, but not so easy that we need to rely on hints.

Other kinds of difficulty, however, are probably wasteful. Seeing good examples and explanations appears to involve different learning processes than learning by doing. The latter can not only be frustrating and slow, but it can lead to poorer generalization as well. For the majority of skills, it definitely seems like a lack of good examples is more of a bottleneck to learning than is an overreliance on easy practice.

Similarly, I now view issues of practice realism in a different light. Realistic practice will be more efficient for skills of low-to-moderate cognitive load. But this same realism can make things harder to grasp for high-cognitive load skills, as in many traditional classroom subjects like math, programming or grammar in foreign languages. The right approach is a ramp: for complex skills, start with simplified problems with plenty of feedback and instructions and move onto more realistic applications in more ambiguous settings once the foundation is secure.

With So Many Changes, Why Listen to Me?I’m not an expert. Part of this is an admission that I still have gaps in my knowledge I’m striving to fill (and likely always will). But part of it is that expertise is a social label. Belonging to that social category would require a career change I’m not particularly interested in making right now.

Given my lack of expertise, and my frank admission that my views have changed, it’s worthwhile to ask whether I should be listened to at all. What are the chances that I’m going to turn around ten years from now and deny everything I’ve said today?

After all, if you wanted to understand the psychology of learning, you won’t do much better than John Anderson’s textbook; for memory, there’s Alan Baddeley’s; from a neuroscientific perspective, there’s Stanislas Dehaene; for teaching, there’s Daniel Willingham’s books and essays; and for expertise, there’s Anders Ericsson’s. I’d trust all of them more than me.

However, if I might offer a weak defense of my work, I would argue:

While my views have changed over time, the oscillations are increasingly minor. The transition from my early to mature writing was dramatic. I’d have to completely rewrite Learn More, Study Less to align it with my current views. Ultralearning, however, would only need a few footnotes.I still believe there’s a gap in learning advice that focuses on the learner’s perspective. The vast majority of serious work in this field centers on teachers. This creates a bias that ignores many of the practical interests people have in learning. It also makes it harder to connect this work with the perspective of students. While some works like Peak, Make it Stick, and Learning How to Learn attempt to interpret this research for a lay audience, the majority of educational research centers on educators, not learners.I try to offer encouragement, not scholarship. While I’m ultimately responsible for the quality of the advice I offer, I’d like to think that the projects I’ve done and the attitudes I’ve tried to advocate have encouraged people to learn as much as they have conveyed any research findings.But ultimately, the justification for my work is you! For some reason, people have stuck around reading this blog, despite it being a continual work in progress. Few people get to make a career about learning things, and for that, I owe everyone who listens to me a debt of gratitude.

The post How My Views on Learning Have Changed Over Time appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 10, 2023

The Ten Books that Influenced Me the Most in 2022

Over the last eighteen months, I’ve been reading a lot to prepare for my next book. My notes list 122 books, most of which I read cover-to-cover. Below I’d like to share a few of the ones that influenced my thinking the most.

1. Fear and Courage by S. J. Rachman

People are more resilient than they are often given credit for by most popular media accounts (or psychologists). Exposure to situations that make us anxious tends to diminish fears rather than sensitize us to them.

As a moderately anxious person, I found this book a valuable antidote to the widespread belief that the best way to manage one’s fears is to seek refuge from them.

2. The Atomic Components of Thought by John Anderson and Christian Lebiere

It was hard to pick just one of Anderson’s books, as I read several last year. The theory behind ACT-R has significantly influenced on my thinking about learning, as I wrote about here.

Amassing a wealth of psychological findings, Anderson has spent his career trying to model the basic cognitive processes that underlie our thinking skills. Given the magnitude of the task, it’s likely that ACT-R is wrong about some important details. Nonetheless it offers a powerful lens for understanding thinking.

3. Theory of Instruction by Siegfried Engelmann and Douglas Carnine

Direct Instruction is one of the most successful instructional methods and has withstood rigorous testing. The basic idea is simple: students fail because teachers don’t teach the subject completely. Smart students can fill the gaps, but weaker students fall behind.

Despite the evidence for its efficacy, Direct Instruction remains underused. Critics attack the approach for being overly rigid in its formulation and for teaching mechanical procedures instead of thinking. However, it is precisely these “failings” that make it so successful.

(Greg Ashman’s The Power of Explicit Teaching and Direct Instruction is a good introductory book to understand the debate.)

4. The Idea Factory by Jon Gertner

From lasers to transistors to solar panels, the modern world was invented at Bell Labs. The Labs birthed the theory of information and was first to witness the echo from the Big Bang.

The Labs emerged from a unique combination of institutional influences. The telephone monopoly ensured the company was well-funded and had endless practical problems to work on. The threat of antitrust action forced unusual generosity with patents, which seeded entire new industries.

Sadly, such a rare combination is unlikely to exist today. Universities are often too focused on scholarly prestige to work on the nitty-gritty of getting technologies to function. Companies are too focused on quarterly profits to invest in basic science. Further proof that, far from being the natural state of the world, innovation is the exception.

5. Cultural Literacy by E.D. Hirsch

What’s the point of school? Hirsch argues that a major, underrated function is giving people broad, shallow knowledge of factual matters that allows them to participate in an educated society. Studying Shakespeare or the Peloponnesian War isn’t practically useful and is unlikely to make you smarter. But, this kind of knowledge is necessary to read The New York Times or The Atlantic and, in turn, participate in literate culture.

I agree with Hirsch on a lot of things. Factual knowledge is underrated. Generic “thinking skills” are overrated. If education is to be good for anything, we should care deeply about what content is taught.

Yet a lot of cultural knowledge is mere signaling. Shakespeare is difficult to read, so knowing a lot of it is a sign that you’re smart and well-educated. But, when most people have a passing knowledge of Hamlet or Romeo and Juliet, it doesn’t signal much. Thus those who want to show off their erudition need to find more obscure works or more difficult literature that the less well-read are unlikely to have mastered. In those cases, the personal benefits of education can easily outweigh the societal benefits.

Hirsch is certainly correct that knowledge matters. But that only makes it more important that we find useful things to teach, not less.

6. How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley

Through copious examples, Ridley shows that the process of innovation is not dissimilar to biological evolution. Innovations are often stumbled into rather than explicitly theorized, and progress is the slow accumulation of small improvements.

Ridley makes a good argument that safety regulation can make us less safe in the long run if it inhibits the learning-by-doing needed to improve. He makes the case that nuclear energy would be much safer today had there been fewer regulatory hurdles to its production. Similar arguments can be made that the high regulatory burden placed on healthcare makes us sicker by inhibiting innovation.

7. Self-Insight by David Dunning

Dunning, of the famous Dunning-Kruger effect, has made a career researching our failure to understand ourselves. We have systematic delusions about our knowledge, intelligence, personalities and characters.

Motivated reasoning likely plays a role, but Dunning also argues that our lack of self-awareness is also related to the difficulty of the task. Knowing ourselves is hard because we receive poor feedback about our own nature.

8. Will College Pay Off? by Peter Cappelli

Does going to college make financial sense? Peter Cappelli argues that this question is fiendishly difficult to answer. On average, college graduates undoubtedly earn more. But the merit of any particular educational option varies considerably.

Cappelli argues against the idea that more vocational training is better, finding that while some job categories pay lucratively, there’s a long time lag between training and employment. Also, overly specialized schooling leads to a lottery system where some students get lucky and others don’t when market conditions change as they graduate. Petroleum engineers made a killing…until they didn’t.

While I found Cappelli’s arguments and data persuasive, I took objection to his uncritical stance that traditional education somehow teaches thinking skills. What separates a Wharton education from a community college isn’t the general usefulness of the instruction but the quality of the students and the prestige of the institution.

9. Comprehension by Walter Kintsch

How are you able to understand the word you’re reading right now? Kintsch is one of the world’s foremost experts on the psychology of reading comprehension. He argues persuasively that understanding is a process of generating multiple, conflicting accounts of a situation, which later stabilize into the most likely picture.

Kintsch’s theory belongs to a class of connectionist accounts for thinking, putting him in contrast with ACT-R’s more traditional production rules approach. While the two accounts differ, I suspect both are “true” at some level. Perhaps, like the story of the blind men describing an elephant, both are grasping at different essential features of the elephant of the mind.

10. Greatness by Dean Simonton

Simonton is at the forefront of historiometric analyses of creativity and expertise. In contrast to experiments done in a laboratory, this approach is more biographical—picking out eminent people and then quantifying and aggregating aspects of their thinking processes.

Following this research, Simonton has argued that chance plays a much larger role in creative success than many psychologists have been willing to credit. The most successful creatives are the most prolific, with their success rate remaining remarkably flat throughout their lifetime. This undermines both the view that slowly-accumulating expertise manifests in better performance and the idea that youthful enthusiasm is central to new ideas. Instead, creative success seems to be largely a function of work ethic.

The post The Ten Books that Influenced Me the Most in 2022 appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 3, 2023

The Intermediate Plateau: What Causes It? How Can We Move Beyond It?

I remember having a conversation with my friend Olle Linge about learning Chinese. I had already spent a couple of years studying, and while I could converse and read some books, I still struggled in more complicated situations. My progress had slowed, and I was in an awkward phase where I sometimes felt confident and other times not.

“Yeah, that’s what it’s like from now on,” was Olle’s half-joking reply.

The intermediate plateau contrasts sharply with the beginning phase of immersive language learning. While those early efforts are marked by some intense difficulties, they are also a period of incredible progress. In a narrow window of time, you go from total incompetence to being able to do quite a bit!

In contrast, intermediacy is frustrating. You don’t feel good enough to claim the work of learning is over, but you see diminishing returns from additional study and practice.

The intermediate plateau shows up in almost every field. As a writer for over half my life, I still wish I were better at it. And yet it’s hard to tell whether my efforts are paying off in terms of better prose. Programmers, managers, architects and doctors all have to deal with the difficulty of being neither a beginner nor the best.

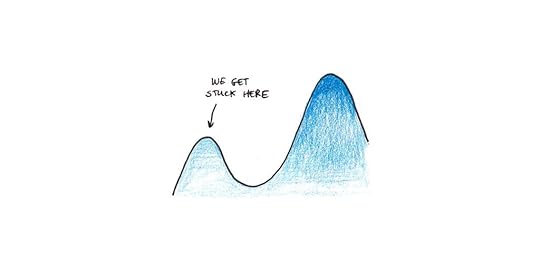

Three Theories for Why We Get StuckI’d like to review three explanations for what causes the intermediate plateau, each having some relevance depending on the skills. Those are:

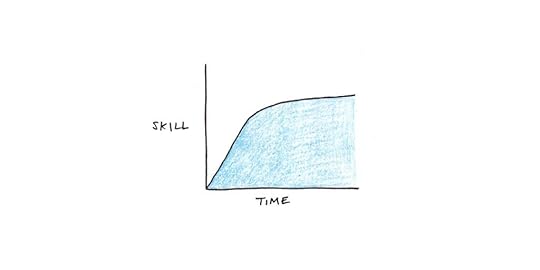

Knowledge grows exponentially with the level of expertise.Progress comes to rely more on unlearning than new learning.Creative problem-solving overtakes (and is harder than!) imitating others.The Exponential Explosion of KnowledgeOne explanation for the intermediate plateau is that skill building is based on knowledge, and knowledge grows exponentially as you progress in a discipline.

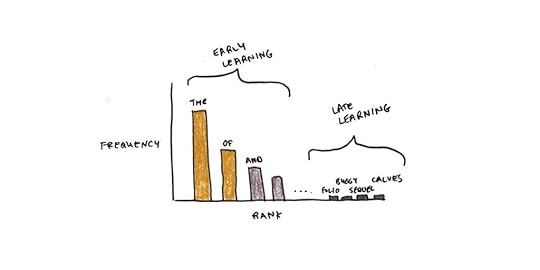

Consider a highly simplified model of language learning, where the only thing that matters are the words you have in your lexicon. According to Zipf’s Law, the usage frequency of a word is roughly proportional to the inverse of its rank in an ordered list of usage frequency.

The most frequently used word in English is “the,” which occurs 7% of the time, about once per 14 words. The second most frequent word is “of,” which occurs 3.5% of the time, about once per 29 words. By this formula, the ten-thousandth most-common word (which apparently is “calves”) would occur roughly 7% x (1 ÷ 10000) = 0.0007% of the time, or about once every 143,000 words.

Each newly learned word takes (roughly) the same amount of mental effort to learn, but the frequency drop-off means that each word contributes less and less to your proficiency.1

In fact, the situation is even worse than this! Knowledge isn’t acquired once and then preserved forever. We often require multiple exposures to learn a word and spaced exposures to sustain it in memory. Because rarer words are used less frequently, they take far longer to become permanent parts of our linguistic repertoire.

Given the rate of forgetting, and the slow accumulation of new words, the intermediate plateau may be the equilibrium point where new learning equals old forgetting. At this level, we forget infrequently-used words as quickly as we learn them, and improvement stops entirely.

Unlearning and Local MaximaThe knowledge-explosion account of the intermediate plateau assumes learning is monotonic. That is, learning is strictly additive—each new word only makes you more proficient, never less.

However, a lot of learning isn’t like this. A person who is learning to type by hunting and pecking on a keyboard further entrenches that method every time they use it. It won’t spontaneously evolve into touch typing, regardless of how much they practice. Similarly, pronunciation often “fossilizes” in language learning, likely because a “good enough” articulation of the language’s phonemes becomes ingrained through repetitive practice and becomes automatic. This makes you more fluent, but it means shaking off a bad accent is even harder than learning new words!

In this account of the intermediate plateau, our lack of progress is due to getting ever-more proficient in mediocre methods. Progress requires interrupting this natural process, fine-tuning our performance, and then rebuilding automaticity on the parts.

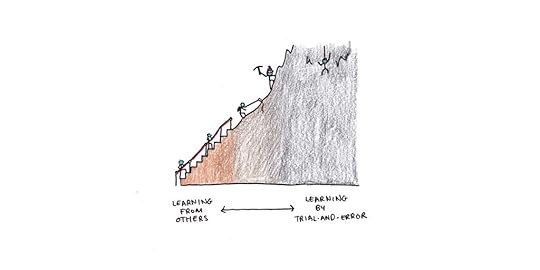

The Copying-Creating BarrierA third reason we get stuck in our progress is that humans are excellent imitators and only lackluster problem-solvers. Crows can figure out how to extract food from a bottle by improvising a metal hook, but only 10% of fifth-graders can do the same.

Anthropologist Joseph Heinrich argues that our capacity to imitate—if one person solves a problem, everyone else can copy their solution—is what truly separates us from other species, not our innate problem-solving abilities. Our ability to stand on the shoulders of the countless generations that have come before us is what enables us to make progress.

Unfortunately, this means there’s a sharp distinction between mastering an old trick and inventing a new one. Learning from others is fast, but it is limited to situations that are routine or allow the easy application of an old principle. New circumstances, in contrast, require an extensive problem-solving search in order to make progress.

The intermediate plateau, by this account, can also be a switch from learning from others, to learning by trial-and-error, with the latter being much slower and more painstaking.

How Can You Move Beyond Intermediacy?Each of the three theories suggests a different potential escape route:

Exponential knowledge requires exponential effort.Unlearning requires deliberate practice.Expert mentorship nurtures creativity.Exponential Effort for Exponentially Growing KnowledgeThe unfortunate fact of mastering a language is that, after gaining basic fluency, further learning requires a disproportionate step-up in effort. The only way to overcome the dwindling usefulness of new vocabulary and the regular atrophy of forgetting is to spend more time in practice. That said, I do suspect there are more efficient ways to do this than simply using the language a lot.

Wordsmiths in a non-native language tend to love collecting new words for their lexicon. I suspect the desire to look words up in the dictionary and memorize their meanings is a trait that leads to better performance than someone who only acquires vocabulary when they have to.

Similarly, reading more advanced literature or attending challenging classes can push one into the frontier of seldom-used words and will increase the the usage frequency of the specialized words. Unfortunately, this also increases cognitive load since comprehensibility declines as you delve deeper into the new vocabulary.

Ultimately, it’s probably a mixture of comprehensible input, which ensures fluency and low-effort practice, and more challenging reading or conversations with easy access to definitions/explanations that will matter.

Unlearning Requires Deliberate PracticeUnlearning to progress in skill development was a theory favored by Anders Ericsson. Building on Fitts and Posner’s influential three-stage model of skill development, he argued that automaticity was a major barrier to improvement.

Fitts and Posner’s model of skill acquisition has three stages:

Cognitive – When you learn the basics of a skill and understand how it works.Associative – When you begin practicing, combining the parts of a skill into larger chunks and weeding out significant mistakes.Autonomous – As errors decline, you perform the skill with less and less conscious effort.The “deliberate” part of deliberate practice refers to both the need for practice sessions outside of work and play, and the mental effort needed to bring the skill out of the automatic state and back to the cognitive/associative state where deliberate effort can be applied.

Essentially, we’re not trying to add to our knowledge so much as weed inefficiencies from our well-learned routines.

Creativity is Enhanced By Expert MentorshipIn problem-solving, we can get further if we see better ways of doing things. Sometimes we get stuck on the intermediate plateau because we have learned everything we can from those around us, and now improvement depends on our own inventiveness. The people who succeed are often those who can find better mentors and, therefore, can continue the relatively efficient learning-from-others path.

Support for the importance of expert mentorship can be seen in the history of scientific accomplishments. Harriet Zuckerman famously analyzed the path of American Nobel laureates. She found that a significant proportion of those who won a Nobel prize were mentored by someone who also won it. Interestingly, most won the prize before their mentor did, so the role of mentorship seems to be much more than just institutional prestige.

Mentorship needn’t be an official relationship. Even having a knowledgeable peer network can help. The more you can learn from others, rather than having to invent on your own, the faster you will progress. Those who are isolated from the help of other people will hit the problem-solving barrier earlier, and thus their progress will slow.

Is Mastery Worth It?Whether it’s extensive (and time-consuming) knowledge acquisition, effortful deliberate practice, or seeking access to elite guidance, mastery doesn’t come easily. In some cases, it’s worth wondering whether it’s necessary.

Despite my focus on learning, I’m firmly in the intermediate camp for all of the skills I’ve spent time on. Intermediacy is nothing to be ashamed of. For many skills, there’s a lot you can do with being “good enough” rather than world-class.

Still, if going beyond your current level is necessary, it’s helpful to think in terms of what is required to get the job done.

The post The Intermediate Plateau: What Causes It? How Can We Move Beyond It? appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 20, 2022

My Best Essays of 2022

I wrote 40 essays in 2022. While far from my most prolific year, I am pleased with how most of them turned out. Thus, to give myself a little writing break over the holidays, I thought I’d share some of my favorites from this year.

Why Don’t We Use the Math We Learn in School? Years after drilling the algorithm for long division, when was the last time you used it? I explore evidence that people are surprisingly bad at the math they ought to know well. I also explain some reasons why math doesn’t seem to play as prominent a role in real life as it probably should.Cognitive Load Theory and Its Applications for Learning. Why do we find some subjects confusing? Why do we struggle to keep up in math or physics classes? I review the major findings of cognitive load theory, which seeks to explain our learning successes (and failures) in terms of how our brains process information.How Do We Learn Complex Skills? Understanding ACT-R Theory. ACT-R is John Anderson’s career-long quest to integrate many diverse findings in cognitive psychology into a single model of the process of thinking and reasoning.How Does Understanding Work? What goes on in our heads when we understand text we’re reading? Construction-Integration suggests we comprehend text by generating multiple interpretations, which then “stabilize” into a coherent picture.Variability, Not Repetition, is the Key to Mastery. Varied examples, contexts, problems and methods all lead to more robust learning than narrow repetition.Cultural Literacy: Does Knowledge Need to Be Deep to Be Useful? I review E.D. Hirsch’s controversial bestseller. Hirsch argues that the shallow, fact-based knowledge we largely forget from our classroom days is far more important than people realize. Schools shouldn’t shy away from teaching these facts, and our society would be better off if we made this aim of education more explicit.Failure is a Lousy Teacher. I refute the commonly-held belief that failure is the key to learning. We gain less information from failures than successes (in most domains). Even “useful” failure it is usually closely followed by success. Failure is also demotivating and can encourage us to overlearn lessons that we would do better to forget.Brain Training Doesn’t Work. We don’t get smarter by strengthening mental muscles. Chess doesn’t help you think strategically, and Sudoku doesn’t make you better at quantitative reasoning. The evidence here is frankly overwhelming, but it’s so at odds with folk psychology that many have a hard time accepting it.I hope everyone has a safe and happy New Year. See you in 2023!

The post My Best Essays of 2022 appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 13, 2022

The Ten-Book Rule for Smarter Thinking

Ten well-chosen books are usually enough to understand the expert consensus on any reasonable question you might have.

At this point, I can imagine the doctors, lawyers and anyone with a PhD cringing at my exceedingly low bar for expertise. But let me unpack that above rule:

The books have to be well-chosen. Any ten random books on a subject won’t converge to the expert wisdom. Even a hundred books won’t if they’re low-quality. I’ll define high-quality books below, but this is an important caveat to remember.Understanding an expert consensus doesn’t make you an expert. Understanding knowledge is a much lower bar than creating knowledge. It’s also a lower bar than successfully applying knowledge to diverse domains. My argument isn’t that ten books would be enough to make you a cardiac surgeon, but they would be enough to understand what most experts think is the right way to do a coronary bypass.There must actually be an expert consensus on the question (or at least, a few dominant viewpoints). You can’t get an expert consensus if experts don’t actually agree on the answer. Similarly, if the question hasn’t been addressed because the fields choose not to represent questions that way, you might be out of luck.A reasonable question is down-to-earth. The highest levels of a field can often formulate questions a novice wouldn’t even think to ask. Understanding string theory or Continental philosophy often requires a much more extensive background of knowledge to even ask reasonable questions. But “why is the sky blue?” or “what is existentialism?” are definitely answerable within ten books. A question is reasonable when it is both something a layperson could readily formulate AND a good answer already exists.Ten books is a substantial threshold in terms of casual interest. It’s much more than perusing a Wikipedia article or an essay. The books in question are not fun, easy-to-digest pop-science. Even at the reasonable pace of a book-per-week, this is about three months of work.

Ten books are considerably less than what it takes to become an expert in anything. But if you want to answer a reasonable question (that meets the criteria above), you can probably get a satisfactory answer just by doing the work.

Given the relatively low bar I claim is needed to understand an expert consensus, why don’t more people do this?

How to Pick the Right Books

The first difficulty people have with this approach to research is that they pick the wrong books.

There are three kinds of books that tend to slow the path to understanding expert consensus, and unfortunately, they’re also the kind that tends to line bookstores and best-seller lists:

Books with “new” ideas. Most ideas are old, even in supposedly cutting-edge fields. If a book is full of novelties, that’s another way of saying it is full of things yet to be widely proven.Books with “useful” ideas. Pragmatism is a virtue, but it often distorts research results. Don’t confuse “what’s the right way to think about this issue?” with “what are practical things I can do about it?”Books with “revolutionary” ideas. Heterodox books that explicitly frame themselves as a paradigm change will make it harder to understand the orthodox perspective.This doesn’t mean the above books aren’t worth reading, just that they don’t count for the “ten” you need to understand an expert consensus. Reading ten self-help books, or ten books about the “new science of X,” or even a controversial best-seller that shows why all the experts are wrong may be fun and interesting, but it will only slowly get you to the general picture experts have about a topic.

What books should you read instead?

I would suggest three types of books, in the following order:

Up-to-date textbooks. Textbooks are one of the most valuable books to read because they are written to represent expert consensus. Even authors with strong heterodox opinions usually present a balanced picture in their authored textbooks.Academic monographs. Monographs tend to be more focused than textbooks, so while you may not get a general survey of the field, you’ll often get closer to the answer you seek via a monograph. If good monographs don’t exist for the question you have in mind, then review articles are often a good substitute.Canonical texts that the field cites as authoritative. I don’t usually start here because, as a novice, identifying these texts and understanding their significance is often tricky without greater context. However, when a particular work is oft-cited in textbooks or monographs, I try to fill in my understanding of it.My claim with the above rule is that if you picked a well-posed question like, “how should I invest in the stock market?”, “what’s the best way to treat anxiety?” or “how do batteries work?” you’d get a good read on the expert consensus by reading those books.

Why Care About the Expert Consensus?Why should we care about the consensus view anyway? Shouldn’t we care about the truth, even if that means turning away from the opinions of a bunch of ivory-tower academics? I think there are good reasons why understanding the modal opinion of experts is still very useful, even if it falls short of knowing the “truth”:

In healthy intellectual fields, “expertise in X” is pretty close to “people who know a lot about X.” Learning the expert consensus is, therefore, a reasonable estimate of the answer to: “if I learned as much as an expert, what opinions would I likely form?” The ten-book rule helps you get close to this estimate.Discourse tends to be grounded in a consensus viewpoint. Therefore, it’s impossible to properly understand a heterodox view without knowing what it seeks to reject. Thus even if you strongly suspect that experts of a particular stripe have the wrong mental model, you still need to learn the consensus ideas and language to understand the alternatives.Knowing the “truth” is problematic; knowing the expert consensus is achievable. Without wading too far into epistemology, there are well-known difficulties in acquiring reliable knowledge about the world. Practically speaking, every discipline has its own standard of evidence and methodological techniques. In contrast, figuring out what experts tend to think is eminently achievable and doesn’t fall into the same quandaries.Engaging in More Research ProjectsIn keeping with my previous post, I think there are two broad ways to learn more about the world: building up from the basics, or learning for specific ends. Both have merit, but after you have mastered the basics, the sheer volume of knowledge explodes, so it helps to ask more pointed questions.

Self-conducted research isn’t without pitfalls. As mentioned above, a major reason people don’t reach the expert consensus after ten books isn’t that their goal was impossible. It’s because they picked the wrong books. Similarly, online sleuthing often leads one further away from reality as bogus sources and “alternative” accounts drown out any reasonable interpretation.

However, I tend to think that these problems have less to do with critical thinking and more to do with motivated reasoning. If you genuinely want to know what experts think about a topic and are willing to read at least ten serious books about it, I would wager you’d be on-target more often than not. All that’s required is to put in the effort and actually want to know the answer.

The post The Ten-Book Rule for Smarter Thinking appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 6, 2022

Good Advice is “Obvious”

Years back, a customer of one of my courses told me that he planned to judge the course based on how “counterintuitive” the advice was.

From the theory of information, this is a reasonable strategy. Information, in this sense, is a measure of surprise. You don’t learn much when someone tells you something you already know. In contrast, ideas that totally change how you think about something are more valuable.

However, from an advice-taking perspective, I think this person was misguided. Not only is good advice typically “obvious,” but a lot of “counterintuitive” advice is actually bad. Somewhat surprisingly, even if advice is obvious, it’s still useful to hear it!

Everything is ObviousOne of my favorite books is Duncan Watts’s Everything is Obvious (Once You Know the Answer). When serious social scientific researchers spend years investigating a question, the lay public often receives the result with a pronouncement of “well, duh!”

Watts argues that this is a psychological illusion. We judge obviousness not by if the information is strictly new—but if it violates our intuitions. Unfortunately, our intuitions are often fuzzy, which makes many scenarios seem plausible.

When investigators painstakingly look into a question and find an “obvious” answer, it may seem like a waste of funds. Except that very often, the opposite conclusion was also plausible! In other words, we actually have learned something from an information-theoretic perspective, but our sloppy intuitions make it seem like we already knew the answer.

The Obviousness of Good AdviceI have been lucky enough to receive a lot of excellent advice. This advice helped me launch a successful business, grow it to a multi-person team and write a best-selling book. Little of that advice was counterintuitive. Instead, it generally crystallized something that had felt like a possibility—but only stood out once articulated by someone who knew more than I did.

One example occurred when I was preparing to market my book, Ultralearning. I had spent nearly a decade working through the ideas, and multiple years going through the process of writing a book. Now the dreaded phase of marketing was beginning, and I wasn’t quite sure how to approach it.

I remember asking James Clear, author of the enormously successful Atomic Habits, to tell me what he did. He told me he had been on 200+ podcasts in the first six months of the book’s launch, including around 80 that were released the first week his book was out. Woah!

By the standard of counterintuitiveness, the idea that “going on a lot of podcasts helps to promote a book” was pretty uninformative. I already “knew” that. But had I not received that advice, I probably would have thought going on a dozen or so podcasts was enough. The advice seems obvious in retrospect, but I would have been wrong had I not heard it.

There Are No Secrets (But You Don’t Already Know The Answer)When I interact with people, I find they often fall into two camps when it comes to advice:

The first group believes in secrets. They think there are special, unheard-of methods and ideas that will cause you to lose weight, earn money or become successful.

The second group believes you already know what to do to succeed. Failure to get ahead, in this case, is either because of a lack of willpower, motivation or talent.

I’d like to argue that both groups are wrong. There is genuinely useful information that people don’t possess. This lack of knowledge—much more than motivation or willpower—keeps them from success in many pursuits.

Yet if you hear “obvious” advice, it doesn’t sound like a great secret. It sounds like the same stuff everybody already knows. Knowledge typically isn’t about discovering secrets. Instead, it’s about figuring out which boring, yet plausible, account of how things work is actually right.

The post Good Advice is “Obvious” appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 28, 2022

Rapid Learner is Now Open for a New Session

About once per year, I offer a new public session of my course, Rapid Learner. This is a six-week program that is designed to make you a better student, professional and lifelong learner. If you’ve found my essays on the science of learning helpful, or found my learning projects interesting, this course shows you how to do it.

Click here to sign up for Rapid Learner.

This is the new edition of the course, which includes 20+ newly recorded lessons, deep dives, walkthroughs and more. If you’re looking to get better at learning difficult things, this course is the place to start.

If you have any questions about the course at all, please email me directly and I’ll do my best to answer them!

Registration will only remain open until midnight on Friday, December 02, 2022 (Pacific time).

The post Rapid Learner is Now Open for a New Session appeared first on Scott H Young.