Scott H. Young's Blog, page 17

November 26, 2022

Why You Need a Learning System

In this lesson series, I’ve talked about why it’s crazy we’ve never been taught how to learn. I’ve discussed how cognitive illusions trick you into using lousy studying methods. I’ve also explained why we get stressed over studying and how to beat it.

Today, however, I want to talk about the importance of having a learning system.

Tips Versus SystemsListen to this articleIf you’ve been following my writing for any length of time, you know I write about learning…a lot. I’ve written hundreds of essays, done in-depth personal projects and reviewed countless research-based books on how learning works.

One part that can be missing from simply following my regular writing is how it all fits together. For instance, perhaps you’re convinced now that retrieval practice works better than review. But how should you actually implement this over the duration of a semester-long course? How should you apply it to learning languages, programming or investing?

Developing a learning system, and not just a collection of tips is essential for a few reasons:

The advice interacts. Retrieval practice is better than review. But guessing your way through problems is less effective than studying the solution. Variable practice leads to better transfer, but not always in the beginning. Advice can’t be considered in isolation, but as part of a broader goal.Practical nitty-gritty often trumps big principles. Deciding to use flashcards to learn words in French is good. But exactly how should you do it? What makes a good flashcard? What makes a bad one? Getting the details wrong can override any noble intentions to learn better.You need to sustain your motivation toward big goals. A lot of learning tips are on the small end—how to remember facts, understand concepts or practice procedures. But ultimately, we don’t care about facts or concepts. We care about things like getting a better job, acing a difficult exam or launching a new business. Being able to see the big picture is essential.Join Me in Building a Learning SystemOn Monday, I’m going to reopen my six-week course, Rapid Learner, for a new session. Unlike my essays (or even my book), this course represents a guided, hands-on experience for developing not just a collection of learning tips, but a learning system. Throughout the course we’ll cover:

How to design a learning project—converting big goals into concrete actions.Developing a productivity system—so you actually get the studying done as you plan, instead of just thinking about it.Refining your practice process—much of the bad learning strategies we use can be fixed through knowing how to practice better.Demystify deep concepts—tools for getting your head around the most complex ideas.Making memories endure—deep dives into mnemonics, metaphors and other strategies to make memories stick.Mastery and lifelong learning—how to go beyond a single project to a lifelong system of learning.The course has guided worksheets, so you won’t just be watching lessons but actively participating in constructing your new system. The community and discussion sections also enable you to work with me and other students on hammering out the details of the learning system you’ll develop.

A small investment in learning now can pay huge dividends later. I hope you’ll consider joining me for the next six weeks as we work to learn better together.

The post Why You Need a Learning System appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 24, 2022

How to Approach Any Exam With Confidence

You know the feeling: sweaty palms, tightness in your chest and the tunnel vision that centers on the exam paper sitting in front of you. You feel like you should know the answers, but you keep forgetting. You glance at the clock and realize you’re falling behind. When the exam finishes you feel awful—you know that you knew more than what you wrote down on the page.

Why do we get test anxiety and how can we approach any exam with confidence?

In the previous two essays in this series (here and here), I’ve already pointed to a key cause: we don’t know how to study effectively.

Cognitive illusions about memory and understanding are pervasive. Often the reason we underperform on exams is because we actually aren’t learning as much as we think we are. Fixing flawed studying strategies is an essential first step.

Yet if you think anxiety makes it harder to perform well, you’re not alone. Research shows that anxiety can lower our working memory capacity by introducing distracting thoughts. This mental bandwidth is essential for cognitive performance, and is one reason why research shows a low level of general arousal is better for complex tasks.

How to Beat Back Test AnxietyListen to this articleUnfortunately, it’s difficult to simply wish away our anxieties. Just because you know you’d perform better without the stress doesn’t mean you can will yourself to relax during exam time.

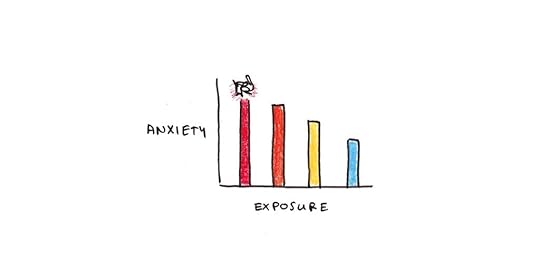

The good news is that there’s a remarkably effective procedure for dealing with excessive anxieties: exposure.

Neuroscientist and anxiety researcher Joseph LeDoux remarks that exposure therapy offers help for dealing with anxiety in around 70% of cases. Other researchers note that it often works as well or better than pharmaceutical interventions.

The basic idea is this: our fears are controlled by primitive evolutionary circuits in our brain. Although the exact process of forming pathological fears is not always well understood, we do have a good idea of what diminishes them. By having direct exposure to the source of your fears, in an environment that is safe, you can reduce their severity.

This means for test anxiety, there’s a few key steps you can take to feel calm on exam day:

Do practice tests under real time pressure. This not only provides exposure, but is also a highly effective studying technique.If possible, do practice tests in the actual testing room. Exposing yourself to the real context makes the transfer of the learned behavior more likely.Visualize the test experience. When realistic exposure isn’t possible, say because there are no practice tests or because the testing environment is inaccessible, visualization can also help.Preparing Your Mind (and Emotions) for LearningLearning well ultimately isn’t just about cognitive tricks for memory and practice. It’s about managing your emotions: staying calm, focused and even excited about learning.

However, just as there are cognitive illusions for what works when studying, we have emotional illusions about how to self-regulate our reactions to stress and difficulty. Instead of facing realistic simulations of our fears, we engage in obsessive behaviors to try to neutralize the stressor mentally. These safety behaviors, however, can actually make the anxiety worse!

By applying effective, research-based techniques, we can make learning more successful and stress-free.

The post How to Approach Any Exam With Confidence appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 22, 2022

Which Matters More: Method or Motivation?

In the previous essay in this series, I complained about how we were never taught how learning works. As a result, we often guess at which methods to use when studying. Sometimes, we guess badly.

To illustrate, here’s a question for you: when studying for a test, which matters more, the method you use, or how motivated you are to learn the material?

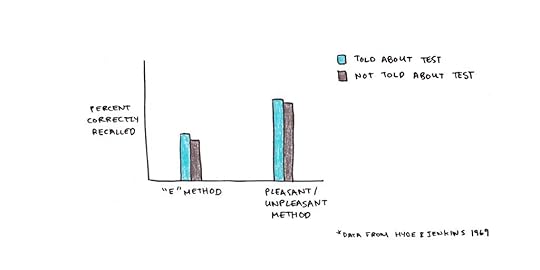

That question is a bit vague, so let’s make it more concrete. Suppose I read out loud to you a list of words. Now imagine I gave you one of two techniques to use: hearing each word and asking whether it contained the letter “e” or asking whether the word felt pleasant or not.

Now suppose I tested you under two conditions: in one condition I told you that immediately after I read the words, I’d test how many you remembered. In the other condition, I didn’t tell you about the test at all, I merely asked you to go through the two different procedures while hearing the words.

Given the two conditions: different methods for learning or different amounts of motivation to study, which do you think made a bigger difference on test performance?

The answer may be surprising: only the method mattered, motivation didn’t matter much at all.

Why We Deceive Ourselves About What Works When LearningListen to this article

Why We Deceive Ourselves About What Works When LearningListen to this articlePerhaps, you might be thinking, this test isn’t a fair one. After all, having lots of motivation often leads to using better studying methods. It also determines how much time you spend studying. After all, if you aren’t motivated, you probably won’t buckle down and learn the material.

This is true. But if the above experiment surprised you, perhaps you should question how “obvious” many other pieces of studying lore are.

In fact, students frequently misjudge the efficacy of their studying. In an experiment by Jeffrey Karpicke and Janell Blunt, they asked students to read a passage and study with one of four different techniques: concept mapping, repeated reading, single reading and free recall. Before being tested, they asked how well they thought they’d do on the test.

The students couldn’t have been more wrong. The ones that used free recall thought they’d perform worst, but actually performed best! Repeated reading (a common studying approach) doesn’t work very well, but it leads to high confidence.

How do we trick ourselves into using methods that don’t work? Psychologist Robert Bjork explains this as a quirk of how our minds work. When we try to assess how well we’ve learned something, we can’t actually see the neural rewiring taking place. Instead, we can only gauge how easy it is to think about the material. This ease is often correlated with learning—think about knowledge of your favorite television show versus knowledge of quantum physics. So the heuristic of substituting ease for learning isn’t always a bad one.

Yet this heuristic works poorly when comparing studying techniques because the methods that feel harder often work better, as indicated in Karpicke and Blunt’s study.

Going Beyond GuessingWe need to go beyond guessing in figuring out what works for learning. This is partly because our intuitions are often deceptive: we substitute ease of processing for depth of learning, and we make motivation all-important—without recognizing that tons of motivation can’t fix a lousy method.

Instead, you need a system. You need to understand how learning works, and how you can make best use of your time to make a difference. If you’re going to spend years of your life learning, you owe it to yourself to invest in a system to learn better.

The post Which Matters More: Method or Motivation? appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 20, 2022

You’ve Never Been Taught How to Learn

Think of all the classes you’ve ever taken in school: math, history, biology, or social studies. Now think about all the classes you took in school for how to learn better. Can you even think of one?

We spend decades of our lives in school. After we graduate, we spend another few decades dealing with a constant bombardment of learning challenges in work and in our personal lives. Yet few of us have been taught the most effective ways to learn new things.

Instead, we’ve mostly been left to figure things out on our own. You find some way to squeak through classes on caffeine and all-night studying sessions. You develop your own personal style of colored highlighters, index cards and rewriting your notes.

Sometimes this ad-hoc method even works. If the class isn’t too hard, or if you’re particularly clever, you can skate by without really questioning your learning methods. Yet, sooner or later, we all encounter a challenge that threatens to break us. We face the class that feels impossible. The new job where we feel perpetually behind.

Faced with a harder challenge, we often feel like we have only two options: double-down on the methods that got us this far, and just work twice as hard, or give up and retreat—never being quite sure if we had it in us to make it.

Why Aren’t Effective Learning Strategies Widely Known?Listen to this articleThinking about it this way, it seems crazy that effective learning strategies aren’t widely taught. It isn’t because they don’t exist. Indeed, research shows that there are tons of methods that we know work well for learning, and they’re often not the ones students use:

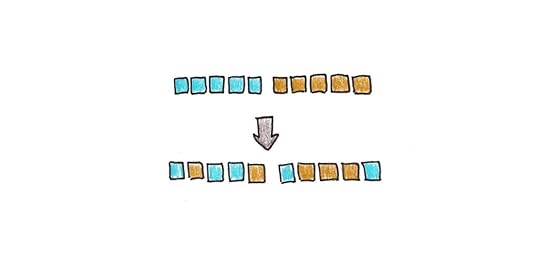

Spacing out reviews works better than cramming.Interleaving studying materials is more efficient than doing one unit at a time.Recall strengthens memory more than review.Self-explanations ensure better understanding and transfer of learning.In contrast, go-to favorites of students are often less effective. Highlighting can be a risky strategy if you want retention. Drawing concept maps isn’t as effective as retrieval practice. Late-night study sessions cut sleep, eliminating essential memory consolidation.

Given the decades we spend studying in school, becoming proficient at our jobs and learning new skills and hobbies, doesn’t it make sense to spend a little time first understanding how learning actually works?

You Need a High-Performance Learning SystemNext week, I’m going to be opening a new session of my popular course, Rapid Learner. Leading up to that course, I’m going to share three lessons drawing upon science and hard-won practical experience for how to learn more effectively.

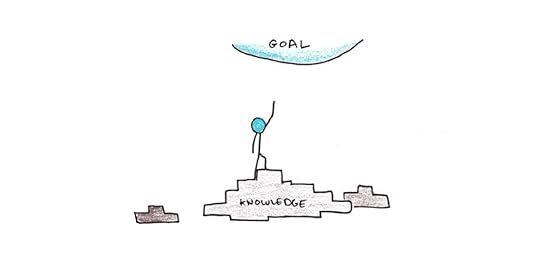

Today, all I want to stress is that you need a coach and a system for learning difficult things. Just as we don’t expect elite athletes to simply guess at the best technique for hitting a tennis serve or sprinting a 100 meter dash, you shouldn’t have to guess at which approaches work best for becoming skilled at the subjects you care about.

The post You’ve Never Been Taught How to Learn appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 9, 2022

Reader Question: What Classes Should I Study to Land a Job?

Reader Talal asks:

I have a question:

Single variable calculus (MIT)Mathematics for computer science (MIT)Harvard CS 50 (Harvard)Intro to algorithms (MIT)Design and analysis of algorithms (MIT)Leetcode practice problemsAre taking these courses enough if I want to get a job at big tech company?

Not being a professional programmer, I’m going to dodge the specifics of Talal’s question. (Although, anyone who does have experience here is welcome to weigh in!)

Instead, I’d like to use this question as a jumping-off point to discuss a broader question. How do you reverse engineer the learning required to achieve a particular outcome (getting a job, passing a test, proficiency in a skill)?

Learning Basics and Learning BackwardsIn general, I think there are two mindsets you can apply to learning:

Start with the basics. In this case, you identify the foundational skills and concepts and work toward broader mastery from the basics.Master a criterion task. Here, you start with the end goal, figure out what you are missing and strive to learn it.Both approaches have merit, but they have different strengths and weaknesses.

Given Talal’s course choices, it seems he may not have a lot of programming experience (or he has programming experience but little formal computer science training). In this case, there’s probably a lot to learn, and proficiency won’t happen overnight.

In this kind of case, I think the strategy of starting with some foundational courses is reasonable, even if those courses alone won’t be sufficient for landing a job. Having some basic idea about how algorithms work, how computers work and how programming generally works is a good idea.

In contrast, if Talal already has a computer science background, taking more and more foundational classes would be unlikely to meet the goal he has in mind. Instead, he would need to work backward. He would need to figure out what specific skills are sought in programming interviews and ensure he has the required competency. If the skills of interviewing and performing on the job are different, he may need to master those too.

Working backward is important because most skills are fairly specific. There isn’t much payoff for practicing skills that differ considerably from the tasks you’re trying to master. Spending your time learning about general programming concepts will be much less efficient than practicing the skills needed to write good code and answer technical interview questions.

When Should You Start with the Basics?Starting with the basics, and ignoring the specific test criteria, is best when cognitive load is high.

Cognitive load refers to how much you need to juggle mentally to understand a new idea. It’s why quantum mechanics classes are hard and why you can’t easily repeat back a sentence spoken to you in an unfamiliar language.

Cognitive load isn’t fixed for a subject—it depends on your prior experience. Familiar patterns don’t use up as much mental bandwidth as unfamiliar ones. This is why learning the tenth word in a new language is much more effortful than learning the 1010th. By the time you get to the latter, the basic patterns of pronunciation and orthography are so familiar that the word “clicks.”

Some subjects intrinsically have a higher cognitive load than others.

Programming, for those without a background in it, is famously high in cognitive load. Everything looks alien and arbitrary. It takes a lot of work to understand what a variable is, what functions are, how pointers work, or why anyone would bother using recursion. You must grasp many individual elements to appreciate a programming design pattern.

In contrast, smaller elements of programming, such as the specific spelling of individual functions, may be low-load—you can pick them up just through regular use.

The higher the cognitive load you’re experiencing, the more it helps to start with basics. Getting an introductory programming book, learning the theory and ideas, and getting lots of practice can make it feel easier.

When Should You Start with the Outcome?Starting with the specific test requirements makes more sense once you have mastered the basics. There are two reasons for this:

1. The knowledge needed to perform explodes beyond the basics.You can have a (simple) conversation with less than a thousand words in a language. But full fluency likely requires fifty times this vocabulary. As you get deeper and deeper into infrequently used words, tailoring which words you learn to the situations you’re likely to encounter begins to pay off.

This is the basic pattern for all skills. The more advanced you get, the more numerous and specialized your knowledge becomes. As it can take a lifetime to master even a subspecialty, it makes sense to work backward from the end goal.

2. Application of knowledge starts to dominate acquisition of knowledge.Abstractly knowing the right answer is rarely enough. You need to be able to retrieve it and apply it to the specific question you face. This, in turn, requires a lot of practice.

Most people who have studied CS would be able to say what a pointer is. But they might struggle to debug a program that has an error in how a pointer is dereferenced. To be useful, you need to be able to retrieve knowledge in the appropriate contexts. That requires practice in situations similar to those you’re likely to encounter.

Fluency in complex skills depends on rapid, automatic access to knowledge. It’s one reason we often make a distinction between knowing about something and being able to perform proficiently in it.

Merging the StrategiesI generally try to do a bit of both when approaching a new learning project.

I often start by looking at the criterion task. If my knowledge is relatively weak, I’ll use that task to assess which broad topics or subjects I need to study. If I am expected to show competence in algorithms, I’ll take a few classes in algorithms.

As I get further along, I spend more and more time focusing on what is needed in the specific situation I’m going to face. Practice questions that are highly similar to those on the test are the best starting point. If those aren’t available, practice that is at least as difficult and covers the kinds of situations you face is probably helpful.

The post Reader Question: What Classes Should I Study to Land a Job? appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 1, 2022

Reader Question: Avoiding “Flashcard Hell” and Finding Enjoyable Studying Strategies

Reader Garrett writes:

I recently received my acceptance letter for medical school. Your content, ideas, and email exchanges helped me so much on this journey. So, I wanted to share that with you and thank you. Ultralearning shaped much of my approach to studying during undergrad.

I want to spell out a problem I am thinking through and see what you think possible solutions might be:

I HATE flashcards. I am not against flashcards because I don’t believe they can be helpful for learning; I hate them because I find doing flashcards to be incredibly boring, tedious, and energy-draining. I don’t know how much you know about the way most medical students are studying these days (it seems like you can’t go on the internet and look up studying content without coming across med-tubers’ videos on the topic), but the majority of students are using premade decks through Anki. The most popular contains around 30,000 cards. After talking with medical students who are using the deck, they report completing 300-600 cards every single day, and this takes them around 1 to 1.5 hours.

Do you have any other ideas about how to deal with topics which are very term heavy without getting lost in flashcard hell?

I found Garrett’s question interesting for two reasons.

First, there’s the issue of flashcards specifically. In this regard, I find myself a lukewarm enthusiast for flashcards. Compared to most people’s default studying strategies, they’re excellent. On the other hand, flashcards are easy to abuse—it’s easy to inadvertently make flashcard decks that won’t transfer well to the subject you’re trying to master.

Second, there’s the broader issue of how to find studying strategies that work for you. I tend to prioritize based on effectiveness because I think the best way to enjoy something is to do it well. A strategy that doesn’t work is rarely fun. Yet, I sympathize with Garrett that sometimes the “optimal” approach can be miserable.

My Mixed Views on FlashcardsIn my studies, I’ve had projects that made heavy use of flashcards and others where I didn’t use them at all. When learning Chinese, for instance, I peaked at around 18,000 flashcards. In contrast, I didn’t use them at all for Spanish. My most recent Macedonian project probably peaked at around 3000 flashcards.

I didn’t use flashcards during the MIT Challenge, and I only made about 20-30 paper flashcards for quantum mechanics to nail down some tricky trigonometric identities. I used them for studying medical neuroscience, but I haven’t used a single one for my recent research project.

Flashcards are easiest to apply when you need to memorize a lot of information that has a cue-response pattern. Thus they’re ideal for learning vocabulary, trivia and laws.

However, flashcards have several pitfalls if you’re not careful:

My view on flashcards is that they’re good supplementary practice. For tasks with a high memory burden, they may even be the bulk of your studying time. Yet, I think they should always be paired with realistic practice—whether that’s having actual conversations in a language, doing practice tests for your certification exams, or using the skill in real life.

What to Do About Effective (but Unenjoyable) Studying Strategies?After discussing some of these points with Garrett, he conceded that (in his view) the quality of the premade medical flashcard decks was relatively high. Thus, the issue was less whether this strategy would work and more whether it was possible to avoid it.

Here, I think it’s useful to keep a few things in mind:

Sometimes a strategy just takes some getting used to. For example, I strongly recommend doing practice tests to prepare for a standardized exam. However, anxiety usually runs high, and people tend to avoid using this strategy at the start. However, if you get in the habit of taking timed practice exams regularly, the anxiety diminishes. The once anxiety-provoking activity becomes routine, and you stop feeling so bad about it. Despite my ambivalence about flashcards, I had no problems using them for four hours a day while in China. Sometimes, you just gotta give it a shot.Understand what the strategy is trying to achieve. If you know the purpose of the strategy, you can replicate it with alternative means. In this case, flashcards are a particularly effective way to get (a) retrieval practice and (b) spaced practice. These are effective studying techniques, but there are other ways to do them. You can do practice problems, for instance, or give yourself recall prompts.Start with a focused approach. As mentioned before, some problems are easiest to solve with flashcards. Vocabulary is a pretty obvious one. But there are fuzzier cases. You can learn a medical diagram through flashcards, or you could print out a blank diagram and fill in the labels without any hints. If you dislike flashcards, I’d start by using them only in the most obvious cases and using alternative strategies where you can.For a competitive learning situation like medical school, the utility of low-efficiency strategies is limited. Like it or not, Garrett will need to pass exams, so there’s a minimum studying-efficiency bar he’ll have to cross to make it.

But for many of us, we’re learning for purposes that aren’t quite so pressing. If you want to learn a language for fun and mainly enjoy watching foreign films, you might not bother with practicing speaking. Similarly, the most rigorous approach to learning to draw probably involves a slow build-up of basic technical skills in increasingly complicated projects. But maybe you just like drawing flowers or faces and want to start there for interest’s sake.

I tend not to talk about optimizing for enjoyment when learning as much as effectiveness. This isn’t because enjoyment is not important, but because I think it is something people can readily do on their own. Only you know what you like to do, so you are the only one who can modify your learning process to suit your own personality and preferences. Learning a lot depends on finding methods that work—and methods you can enjoy and stick with!

The post Reader Question: Avoiding “Flashcard Hell” and Finding Enjoyable Studying Strategies appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 26, 2022

Variability, Not Repetition, is the Key to Mastery

Bruce Lee is reported to have said, “I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.” With all due respect to Mr. Lee, he might have been wrong about this one.

Variability plays an essential and oft-neglected role in mastering complex skills. Considerable research shows that practicing in varied contexts with varied methods and performing with varied task constraints results in more robust learning than simple repetition.

Below, I’d like to review some of the key research supporting the role of variability in learning and suggest how you can apply this to your career and studies.

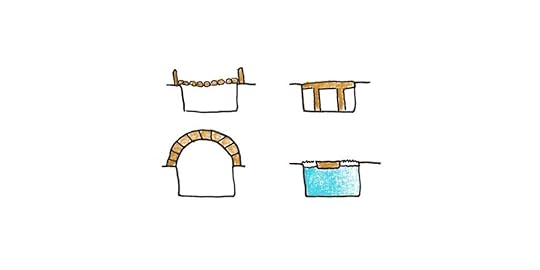

Contextual Interference: Same Method, Variable SituationsContextual interference occurs when you practice the same skill, but vary the situations in which it is called for.

For instance, you could practice your tennis backhand by being served backhand shots repeatedly. Alternatively, your coach could mix things up: serve you backhand shots interspersed with balls that require a forehand shot.

Or imagine preparing for a calculus exam: you could study all the questions that require the chain rule, then all the questions that use the quotient rule. Instead, you might shuffle these questions together so you can’t be sure which technique is needed.

Contextual interference improves the transfer of learning to new situations. There are a few reasons contextual interference works:

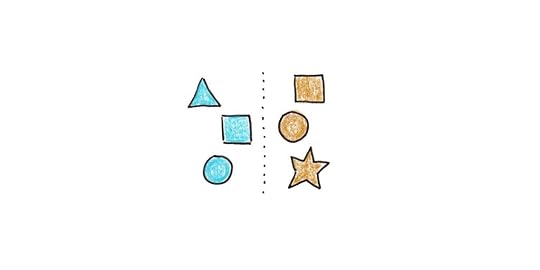

Identifying problems correctly and ensuring the correct technique is associated with the problem. A major difficulty in learning isn’t getting knowledge into your head—but getting it out at the right time. Practice that repeats the same technique in narrow situations may result in skills that aren’t accessible when you need them.Putting similar situations side-by-side helps you compare them. Seeing two problems that look similar, but require different solution methods, makes it more likely that you’ll attend to the key distinction between them.The extra effort needed to retrieve the right response may be desirable. According to psychologist Robert Bjork’s influential theory of memory, more difficult retrieval results in greater memory strengthening than easier retrieval. Thus, more variable practice is likely more efficient practice.Abstracting the Deep Structure: Same Idea, Different ExamplesVariability plays a role in abstracting the deep structure of seemingly different situations. Experts tend to perceive the deep principles of a particular problem. In contrast, novices tend to get distracted by the superficial features.

Physics experts, for instance, tend to look at problems and see “conservation of energy” or “forces must be balanced if an object isn’t moving.” In contrast, novices tend to look at problems and see “it’s one with a pulley” or “it’s an incline-plane problem.”

The exact role of concrete versus abstract representations in thinking is controversial in cognitive psychology.

Some theorists argue that we reason through storing multiple, specific instances of ideas. Others argue that we erase the specifics, leading to generic stereotypes of situations we deal with. Regardless of whether thinking is fundamentally concrete or abstract (or some mixture of both), seeing multiple examples is central to learning.

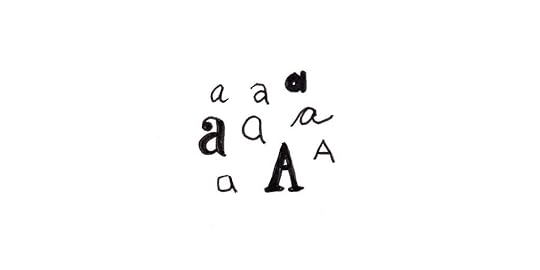

A central principle of the highly-successful teaching strategy, Direct Instruction, is to present students with examples that span the full range of possibilities for a concept. So instead of teaching students to recognize the letter “a” by showing students the exact same letter, we would show “a” in a variety of fonts and typefaces. A student learns that all of these as represent the same “thing” by being exposed to multiple, varying examples:

Ensuring Robust Learning: Same Strategy, Varied Problems

Ensuring Robust Learning: Same Strategy, Varied ProblemsA substantial challenge in learning is that the mind economizes on effort. This means we often fall prey to psychological shortcuts that give us the correct answer, even if they won’t benefit us in future situations.

One study that looked at this required participants to predict a trajectory. Some participants were given a low-variability condition which only involved a few different paths. Other participants were given a high-variability condition which involved a much larger set of different trajectories.

The researchers found that the method participants adopted depended on the variability of the task. When variability was low, participants simply memorized the pattern. In contrast, when variability was high, they simulated the trajectory to find the likely destination.

This result shows that when practice has low variability, we often adopt shortcuts that won’t necessarily generalize to the broader conditions of a task. These effort-saving maneuvers aren’t always conscious, so it’s not simply a matter of laziness. This is one reason I caution students when using flashcards for subjects like mathematics. If you’re not careful, it’s easy to design cards where you memorize the answer (x = 7) and not the method.

Evolving Practice: Same Problems, Varied StrategiesThus far, we’ve discussed variable contexts, examples, or task conditions. But having multiple methods for getting the right answer is also an important part of mastering complex skills.

In contrast to the classical view that experts and novices use a particular method, developmental psychologist Robert Siegler finds that people use multiple methods to come up with answers. In his study of how addition strategies children use evolve, he discovered that most children used at least three techniques. Even college students will use multiple methods for single-digit arithmetic.

Following this data, Siegler proposed the “moderate experience hypothesis.” Strategy variability will be highest when we have some, but not a lot, of experience.

Vimla Patel has documented a similar pattern in the thinking of medical students. Intermediate students, but not novices or experts, show the most elaborations in their reasoning about medical cases.

Siegler argues that this variability is beneficial. First, the “best” strategy depends on the current skill level. Direct retrieval of the correct addition fact (7 + 5 = 12) is easiest—but this strategy only works when we’re confident we know the right answer. Having an assortment of backup methods is helpful in situations when we have lower confidence.

Having multiple strategies for solving a problem is vital when you aren’t yet at the level of mastery. It ensures not only backups you can fall upon when more difficult methods fail, but it gives different reasoning paths to reach the right answer.

Avoiding Local Optima: Same Challenge, Varied Task ConstraintsA classic learning dilemma is avoiding methods that work well enough, but aren’t the best. In this view of learning, progress is like trying to find the highest point in a vast forest. It makes sense to keep climbing until you reach a peak, but getting stuck on a small hill is easy—even if there’s a taller mountain nearby.

Climbing downhill is hard and feels counterproductive. We instinctively avoid changes that make our performance worse than it might otherwise be, even if we suspect it is good for us in the long run.

One way out of this trap is to practice with variable constraints that prevent using the dominant strategy. A rock climber who leans toward explosive, dynamic jumps might explore a new style by climbing with the constraint of pausing for a second before each new hold. A writer who relies on personal stories might make a rule to avoid them for a future essay.

When is Variability Good? Watching Out for Cognitive OverloadMost research supports the benefits of variability in practice. However, less-variable practice is often better for beginners or lower-performing students. The logic here is relatively straightforward—if you can’t perform a method under helpful, simplified conditions, you probably won’t benefit from making things harder.

Having variable methods may also backfire if some of those methods are buggy or flawed. Researchers have found that broken algorithms for basic mathematical procedures lead to difficulty in learning more complex algorithms, such as multi-digit subtraction problems.

These two considerations moderate the extreme stance that all variability is good when learning. Instead, we want to see a slow ramp-up in variability. Learning should start with clear instructions and concrete examples when a skill is new and expand into increasingly broad contexts as we progress.

Applying Variability to LearningGiven this research evidence, how can we apply variability to learn better?

Mix up your problems. If you have to study problems, mix them up so there aren’t clues telling you what strategy you need to apply. Mix together Unit One and Unit Two—and don’t indicate which problems come from which sections.Choose opportunities with greater variability. Management consultants who work for a wide range of clients are more likely to learn broad principles than those who work only with a single firm or industry. Psychologist Gary Klein reports that inner-city firefighters progress much faster than rural firefighters, owing to the more varied firefighting conditions. Choosing jobs with greater variability early in your career may lead to better skill development than narrow specializations.Work with multiple teachers, peers and styles. Learning a language, for instance, benefits from exposure to different speakers, accents and speaking styles. Learning from several teachers is more likely to promote diverse perspectives. Having a variety of peers exposes you to different strategies and is less likely to get you in a rut.Add constraints that force you away from dominant strategies. Performing skills under different constraints forces you to explore wider areas of the problem space. This added variability helps you discover new strategies and kicks you out of ruts that can develop when an easy, but sub-optimal, method is relied on.How can you increase variability to improve your practice efforts? Share your thoughts in the comments!

The post Variability, Not Repetition, is the Key to Mastery appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 18, 2022

Why Didn’t More People Take the MIT Challenge?

Ten years ago, I finished a personal project to try to learn MIT’s computer science curriculum on my own. Strangely enough, the project was both a resounding success and an abject failure.

The project was successful as I largely did what I set out to do. I managed to hew closely to the content in MIT’s undergraduate computer science curriculum. And I managed to pass most of the final exams for the courses. While there’s plenty of room for critiquing aspects of my self-grading or workarounds for missing materials, there’s no question I learned a lot.

However, the project was a complete failure in terms of what I imagined would come from it. At the time I took on the project, I genuinely believed the coming wave of free online courses would transform higher education. After all, if someone can acquire the skills taught in a degree program for a fraction of the cost and with far greater flexibility, that’s a competitive alternative to college.

Despite that, I only know of a handful of people who have completed something broadly similar. Why?

What Explains the Lack of Follow-Up to the MIT Challenge?Why have we not seen an explosion of online education substituting for on-campus credentials in the ten years since this project finished? Let’s look at a few possibilities…

1. The MIT Challenge is unrealistically hard for most people.Most of the attention I got for the challenge was my decision to do it in twelve months. This choice branded me as a studying whiz, but it wasn’t the central motivation for the challenge. Instead, I found it compelling that I could learn the entire CS curriculum from one of the best engineering and technology schools on the planet without leaving my bedroom.

The kind of self-paced, online education I pursued during the MIT Challenge is more flexible than traditional schooling, not less. Thus, while I accelerated the pace to push myself, I could always slow it down if I wanted to.

Finally, I don’t buy that I’m particularly brilliant for succeeding with my project. I’m not more clever than the average MIT student, for instance. Going through the curriculum faster was only possible because of the enhanced flexibility the online format offered. I would have struggled to do the same in a brick-and-mortar institution.

Thus, even though this is the part most people fixate on, I don’t think the perceived difficulty of the MIT Challenge has much to do with why it isn’t more popular.

2. Online education doesn’t work as well as in-class learning.The world got an unexpected test of online learning when the COVID-19 pandemic started. Schools were shuttered. Classes ran on Zoom. Harried parents juggled working from home and trying to keep kids on task. The lesson many have drawn from this experience that there’s something important missing in online education that can only take place in a physical classroom.

I’m deeply skeptical of this explanation.

The COVID-19 pandemic isn’t a good experiment for online learning. Most teachers were ill-prepared to transition to an online-only environment. As a result, Zoom classes combine the inefficiencies of sitting through lectures in an auditorium with the lack of supervision of at-home studying.

While it’s certainly possible that group discussions, feedback from teachers, accountability on deadlines and a physical change of environment have positive impacts on learning, none of these were impossible to implement in online learning. After all, if online self-education really did provide a meaningful substitute for an academic degree, why wouldn’t we see local study groups or on-demand tutors offering their services?

3. Education is Mostly Signaling, and Students (Rightfully) Shouldn’t Care Much About Learning.Another explanation is that the primary value of school is signaling—it shows that you have the smarts, work ethic and conformity to do well—rather than building useful skills.

Bryan Caplan has made a spirited defense of school as signaling in his book, The Case Against Education. He argues that what is taught in school isn’t particularly useful on the job. Instead, schooling provides a mechanism for figuring out who has the talent, ambition and obedience to learn on the job successfully.

There’s likely some truth to the signaling hypothesis. And the effect of signaling is likely much higher for prestigious institutions. Having an MIT degree is probably more valuable than having an MIT education.

However, this explanation can be taken too far. While I do suspect the Harvard history major who eventually becomes a CEO is likely not drawing directly upon academic skills to run a company, it seems a much weaker case to argue that a computer science education is irrelevant for success in professional programming.

Programming is also an outlier because the need for credentials is weaker than in many other technical professions. Lawyers, architects, doctors, and accountants are all required to submit to regulatory authorities to practice their craft. On the other hand, coders, web designers and data scientists have largely been spared the trend of making credentials a prerequisite to practice.

I agree with Caplan that signaling probably plays a significant role in education. Yet, I think the case for signaling is weaker with technical skills that match their professional application and for professions without onerous licensing requirements that make self-education impossible.

Why I’m Still an Online Education OptimistUltimately, the real explanation for the slow adoption of alternatives to higher education may not be so different from the adoption of any new technology. Multiple criteria must be fulfilled for any technology to become broadly popular.

For online learning, I believe there’s a few:

Better materials. Right now, online education is dominated by 1) material from brick-and-mortar institutions (which isn’t well-designed for the online format and can make taking classes difficult) and 2) edutainment courses which are flashy and exciting but often lack rigor.Better credentials. My MIT Challenge was lax in proving I learned what I said I did. I self-administered and graded exams and programming projects. At the time, I felt like I was on the frontier, that institutions themselves would do this within a few years both to ensure exacting standards and prevent cheating. While there is a crop of new online degrees and certificates, it remains to be seen whether they measure up.More job-relevant skills. Elite education is purposely impractical. As I wrote immediately after the MIT Challenge, I wouldn’t have followed that exact course if my short-term goal had been to get a programming job. Too much focus on theory, too little focus on application. Yet, a decade later, I rarely write any code, but I use a lot of the foundational ideas taught in the MIT coursework to understand other fields. Thus, while I think online education providers need to offer people more immediately practical skills, I’m still grateful for the benefits of a deeper education.Thus, while critics of online education specifically, and education generally, make some compelling points, I’m still an optimist about the possibilities. Learning anything, anywhere, for the cost of an internet connection is still an idea worth believing in.

I’m probably never going to do another project like the MIT Challenge. I’m busier and less bold than I was a decade ago. Yet, I still make a point of refreshing through MIT’s OpenCourseWare catalog every few months to see if there are any new courses to watch. Perhaps the slower, less boastful approach I follow today won’t get me as many new subscribers, but I’m enjoying it all the same.

The post Why Didn’t More People Take the MIT Challenge? first appeared on Scott H Young.

The post Why Didn’t More People Take the MIT Challenge? appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 11, 2022

Recent Reading: 7 Books on the Science of Learning

How does the mind work? Why do the best writers get the most writer’s block? Is the process of evolution the key to understanding the development of thought? Here are some selections from my recent reading.

1. How Can the Human Mind Occur in the Physical Universe? by John Anderson

Given the title, you might be expecting this question to be rhetorical. As in, “How could we possibly understand something as mystical and limitless as the human mind?” Instead, Anderson offers a sincere answer to the question of, as Allen Newell put it, “how the gears clank and pistons go” in the human mind.

Anderson considers three dead-ends visited by psychology (two of which he stumbled down himself):

Ignoring the brain. Herbert Simon and Allen Newell spearheaded this classic approach. Early information-processing theories waved away the question of how functions are implemented in the human brain. This led to theories that were similar to serial computers—but biologically implausible.Ignoring the mind. Another idea, eliminative connectionism, assumed we could infer higher-order mental processes from the behavior (or presumed behavior) of networks of individual neurons. To their credit, computational neural networks have worked well as pattern-associators. Still, Anderson argues these networks only model unreasonably small slices of human behavior. Understanding the mind requires integrating human intentions, memory and step-by-step thinking processes.Ignore the mechanism. Another dead-end is to start by assuming that the brain needs to adapt to the real world and then infer cognition based on those constraints. While Bayesian analysis can match the statistical patterns of memory, this path ultimately dodges the question of how memory actually works in the brain.Anderson’s answer is ACT-R, his long-developing theory that I’ve previously reviewed. His research has attempted to synthesize the contributions of many different fields of psychology to present a reasonable model of how humans think. While some may scoff at the possibility of answering the question itself, Anderson’s attempt comes as close as any to unraveling the enigma.

2. Toward a General Theory of Expertise edited by Anders Ericsson and Jacqui Smith

What makes experts better than beginners? What changes in the mind to allow a grandmaster to pick the right chess move, a doctor to diagnose the right illness or a tennis pro to hit a perfect backhand shot?

The study of expertise has produce a host of replicable findings about differences in expert performance:

Novices reason backward, experts reason forward. Backward reasoning is a process of successive goal-setting, where you start with your final goal and work backward to intermediate steps you need to take. Forward reasoning, starts from where you are and moves automatically to the end. Studies find that experts usually do more forward reasoning, characteristic of routine actions, and novices engage in the effortful backward reasoning of problem-solving.Novices see arbitrary pieces, experts perceive meaningful chunks. Experts see complex patterns of information that allow them to reconstruct what they’ve seen without difficulty. Novices, instead, see a bewildering array of component parts they struggle to make sense of.Novices rely on weak methods, experts use strong methods. Weak methods are the general-purpose tools we use when encountering novel situations. These include heuristics like hill-climbing (keep changing things in a direction closer to the solution) and trial-and-error. Strong methods are domain-specific methods that deal with particular problems.While a host of expert-novice differences have been studied, we know comparatively less about how novices become experts.

3. The Psychology of Written Composition by Marlene Scardamalia and Carl Bereiter

The standard picture of expertise is that experts reason automatically and fluently, moving from problems to solutions in a straight line. In contrast, novices stumble through effortful problem-solving, hitting dead-ends as they work towards the answer.

Writing defies this picture.

Instead, Scardamalia and Bereiter observe that new writers exhibit surprising fluency. Novice writers frequently begin writing immediately, almost as quickly as they can put pencil to paper. In one investigation, children were astonished when told that experienced writers sometimes spend as much as fifteen minutes thinking about what they’ll say before writing.

In contrast, experts are slow, plodding, effortful problem-solvers. They frequently get stuck, experience writer’s block and struggle with writing. Despite this, they produce far better prose.

Why does writing defy the normal rules of expertise? Scardamalia and Bereiter’s answer is that novices and experts use different processes for writing.

They find that novices use what they call a “knowledge-telling strategy.”

A novice tries to recall as many ideas as possible that fit the topic and the conventions of the writing format. When given a writing prompt such as “Should students be able to choose what they study?” children try to generate sentences that fit both with the topic of scholastic choice, as well as the overall format of an opinion essay.

In contrast, they argue that experienced writers use a more elaborate process they call a “knowledge transformation strategy.”

The expert is working simultaneously in two problem spaces. The first is one of rhetorical issues (e.g., will my audience find this convincing?), and the second concerns content issues (e.g., what do I believe about this?). This back-and-forth process is effortful, but it results in better writing than is achieved by novices.

I found this book fascinating, both for providing insight into my own writing process and for offering validation for my observation that writing has gotten harder for me as I’ve gotten (hopefully) better at it.

4. How We Learn to Move by Rob Gray

How do people get good at athletic skills? The classic answer is through repetition. By repeating the correct technique over and over, we eventually perfect our golf swing, running stride, or jump shot.

Gray argues against this view, arguing that not only does repetition not work, it isn’t even possible! Instead, he argues that motor skills are a dynamic, adaptive system. We need variability in our movement and practice to avoid injury and fine-tune our motor coordination.

I’ll admit, motor skills are a lacuna in my general knowledge of skill development. So it’s hard for me to judge how mainstream Gray’s views are. Nonetheless, I found his ideas plausible, especially given how difficult it is for people to understand their own body movements.

5. Parallel Distributed Processing by David E. Rumelhart and James L. McClelland

Parallel distributed processing, or connectionism, is the idea that we need to understand how the brain is organized to understand thinking. PDP is considered a landmark book in launching the serious study of computational neural networks.

A few general ideas proposed by PDP include:

Distributed representations. Rather than represent memories or ideas through single “tokens” or units, connectionism stresses mental representations extended over many neurons. In this way, the coding for the memory of your grandmother, high-school chemistry teacher or Brad Pitt isn’t a single neuron somewhere in your brain but a diffuse pattern of activation over countless units. This distributed representation allows for robustness, but it has drawbacks. The question of how these networks can encode relational properties (e.g., “the dog bit the man” vs “the man bit the dog”) vexes cognitive scientists and machine learning researchers alike.Thinking as “relaxation.” A challenge of real-world thinking is that it often involves drawing inferences under many ambiguous constraints. Serial information-processing models often result in an explosion of possibilities, which makes them impractical for commonsense reasoning. Connectionist networks avoid this difficulty by having possibilities compete with each other for expression. As incompatible ideas suppress each other, eventually the most likely option emerges. Relaxation of this kind is a major part of Walter Kintsch’s Construction-Integration theory, which I reviewed here.Learning through error correction. Training distributed representations is done via back-propagation, where errors are used to adjust the weights of aspects of the neural network into an optimal configuration.This book sat on my shelf for years before I finally gave it a read. My current view is that connectionism provides a better approximation of the intuitive/sensory/low-level aspects of thinking, and symbol manipulation is a better approximation of the rational/cognitive/high-level aspects of thinking.

6. Emerging Minds by Robert Siegler

Child development has long been characterized by a staircase metaphor of progress. Influential Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget observed that children of different ages used characteristically different approaches to thinking. This tradition has continued into the information processing age, with theorists such as Robbie Case arguing that these correspond to discrete increases in working memory capacity. Staircase thinking also occurs in “theory” theories, which propose that young children have different representations of physics, psychology or the outside world than their more mature counterparts.

Siegler argues that the staircase metaphor is wrong. Instead, he argues, the field has systematically overlooked variability in cognitive development. Instead of a single way of thinking, what is impressive about people is how many different ways we have of thinking. Children often exhibit several methods for solving a problem and don’t inevitably use the best one.

This variability has consequences. Siegler argues for an evolutionary approach to thinking. Just as species aren’t neatly ordered on a ladder of creation, nor are human mental abilities explained by the staircase metaphor. Instead, a wide variety of methods compete and adapt for application through repeated exposure.

Siegler has conducted extensive investigations of how children approach problems of addition. He finds that the strategies children use evolve over time. They begin by counting from both numbers, then move on to counting from the larger number, then retrieving the answer directly from memory. However, this transformation doesn’t occur suddenly. Children use multiple methods whose frequency changes over time as they learn new tricks and memorize the answers.

I haven’t read enough developmental psychology to say whether Siegler’s book represents a new consensus or a heterodox view. Still, I find his idea interesting for suggesting that learning skills may involve acquiring completely different procedures at different stages of growth.

7. On Problem Solving by Karl Duncker

Decades before Newell and Simon’s book on problem solving, Duncker wrote a tight little academic monograph investigating the thinking people used when solving problems.

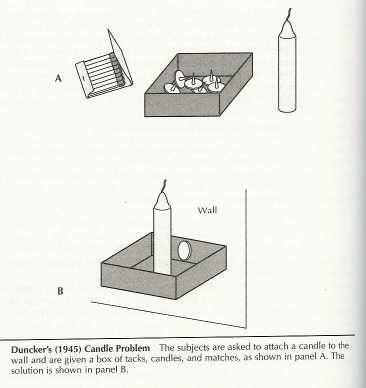

It’s from this book that the concept of functional fixedness appears. This is the idea that in seeing an object as having a particular function, you are less able to see it in an alternative function.

The classic experiment is his task asking subjects to fix candles to a wall, provided a box of tacks. If you put the box separately, most subjects recognize it as a suitable platform and fix the box to the wall before resting a candle on top. In contrast, if you put the tacks or candles inside the box, subjects view the box as a container and thus very few solve the problem.

I’m fascinated by Gestalt psychology. Despite being an extinct lineage in the evolution of scientific psychology, work by Gestaltists presaged much of the cognitive revolution. The Gestaltists were mostly German, and the rise of Hitler forced many of them to relocate to America, where they faced a less favorable environment to their brand of psychology. If Thomas Kuhn was right, and scientific paradigms are incommensurate (and, to a certain extent, arbitrary), I wonder if twenty-first century psychology might have looked very different had history played out differently.

Additionally, my friend Barbara Oakley has a new course focused on online teaching. If you’re a teacher, professor, or just an online video-maker, this course is a guide to the practical nitty-gritty of running a course—and also digs into the scientific details behind successful teaching.

The post Recent Reading: 7 Books on the Science of Learning first appeared on Scott H Young.

The post Recent Reading: 7 Books on the Science of Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 27, 2022

Building Confidence in Communication: Interview with Tristan de Montebello

Few skills matter more than effective communication. Yet soft skills are often the hardest to master. To get some tips, I interviewed my good friend, Tristan de Montebello.

Readers of Ultralearning will remember Tristan became a finalist for the World Championship of Public Speaking after a seven-month intensive project. Since the book has come out, Tristan has built a coaching practice around helping people be more confident communicators.

In our interview, we share the story of how he got good at public speaking, as well as the methods he’s found most successful in his coaching practice to make people more confident communicators.

Check out the full interview:

Listen to the full episode as a podcastWatch the full conversation on YouTubeHere are some of my favorite parts…

Why it’s important to “stay in character”Turn on confidence like a switch

The easiest thing to change right now, without any training is the concept of staying in character. … Next time you speak, you bring forth your confident self. It’s just a mindset shift.

Staying in character means, if I fumble, I don’t go, “oh, sorry, sorry, sorry.” If I think I’m losing everybody, I don’t say, “You probably don’t understand what I’m saying.” Just take a breath, you re-route and you keep going.

The important difference between skillset and mindset

You think people are looking at you, that they’re really paying attention to every single word you’re saying, every single movement you’re making. That’s simply not the case.

People are not listening to your words, not really. They’re kind of making up a story in their own mind. As I’m speaking to you, Scott, you’re probably thinking about this podcast, “hey, are we going too long? Do I need to re-route this? What’s a good next question?” You might be thinking about your audio and tech setup. Your mind keeps going back-and-forth.

If you realize that, the details that are so evident to yourself don’t really matter. If you can take that out of the equation, suddenly you can turn your confidence on.

Confidence is just a switch, and you can gain 30-40% more confidence just by deciding, “I’m going to be more confident.” We prove this all the time in our workshops where we get people to speak and then we say, “Okay, do it again, but this time be more confident.”

The biggest shift we discovered was that people’s skillset was usually much higher than their mindset. Everybody has been speaking since they were thirteen to fourteen months old. We’ve been training all our lives. We all feel comfortable speaking to someone in the world: our partner, our friend, our mom.

We already know how to speak, to tell stories, we already know most of the basics of speaking. The real problem is not only have we not experimented with that under pressure, but we don’t believe we can do it under pressure or in a different environment, because we’ve never really been there.

All of our practice is around putting you in a safe environment, where there’s no real failure because everybody is in it with you, and you’re just getting a ton of reps, under pressure. We just have a bunch of games where we tweak different things—throw random words at you, we make you complete sentences, we force you to take very long pauses in the middle of your speaking.

Put all of that together, and get enough reps in, and all of a sudden you feel more comfortable outside of this world. I start feeling more comfortable in my team meetings, I speak up a bit more in my group of friends, these little incremental shifts start happening.

If you’re interested in improving your speaking skills or getting rid of your speaking anxiety, you can learn more about Ultraspeaking here. They have a free version of their product which draws on Tristan’s learnings from his journey to the finals of the World Championship of Public Speaking.

The post Building Confidence in Communication: Interview with Tristan de Montebello appeared first on Scott H Young.