Scott H. Young's Blog, page 13

August 29, 2023

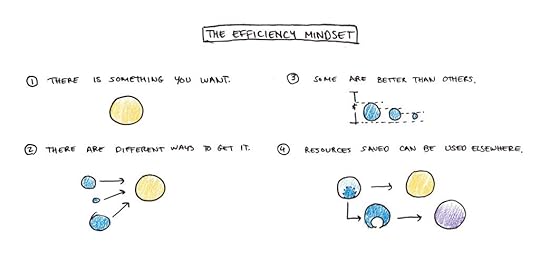

The Efficiency Mindset

Our deepest beliefs are often girded by assumptions we rarely articulate. The mindset of efficiency is one of mine.

The assumptions of this mindset are essentially:

There are things we want.We can take actions to get the things we want.Some actions are more efficient than others—i.e., they will get more of what we seek for less time, effort, money, etc.The resources we save by being more efficient can be spent on other things we want.

To consider a concrete example, think of a task like studying for an exam:

There is something you want: to pass the exam and learn the material.There are actions you can take to get what you want: studying.Some actions are more efficient than others: some methods of studying result in more learning than others.If you use more efficient methods to save time studying for the exam, you can put that time toward other activities you enjoy.The efficiency mindset applies broadly because these assumptions apply to many things. But it’s also important to note where they break down.

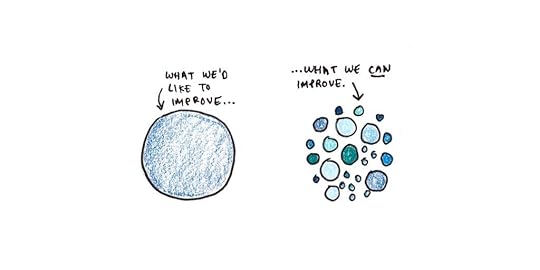

Where Does the Efficiency Mindset Break Down?A common criticism of the efficiency mindset is rooted in an overly-narrow interpretation of assumption #1, the things you want.

Consider speed reading a novel. This is “efficient” in the sense that you’re getting through the book in less time. But is that really what you want?

Much of the value in reading a novel comes from enjoying the plot, dwelling in the world of the characters, or pondering the book’s deeper meanings.

When efficiency often fails, it is usually because we’ve adopted an overly restrictive, incomplete, or inaccurate view of what’s valuable about the activity.

While this is a wrinkle in applying the efficiency mindset, it’s not a compelling argument against it. If you incorporate all the things you value, appropriately weighted, then the efficiency mindset still works. It’s essential to include things like “enjoyment” and other often-overlooked values when considering the efficiency of reading novels.

The real failure of efficiency isn’t an overly narrow conception of what we desire, but when assumption #4, that you can reinvest resources saved by being more efficient, breaks down.

When Working Harder Only Creates More WorkCentral to the efficiency mindset is the idea that the time or resources saved through efficiency are fungible. You need to be able to take the time, money or effort saved on doing one thing and apply that to something else. If you can’t reinvest the resources, doing things more efficiently doesn’t pay off.

As a teenager, I worked at a video rental store one summer. Being more efficient working at the store was kind of pointless. The boss would exhort employees to spend idle time cleaning the shelves or tidying the display racks, but people seldom did. When the store wasn’t busy, we just lounged around. When there were tasks to be done, nobody was in a hurry to finish them quickly.

The fact that nobody (except maybe the manager) thought about efficiency made total sense. Working harder didn’t pay off. Our hours were set, we earned minimum wage, and there weren’t performance bonuses for extra effort. Nobody was angling for a promotion or hoping to move up the video-rental corporate ladder. If you finished your work early, there was only more busy work. You didn’t get to do anything more interesting with the time saved.

Additionally, in that environment, working more efficiently was socially costly. Hanging out with the other staff was the only glimmer of joy in an otherwise mindless job, so if you became the person who got everything done with speed, you made your other coworkers look bad.

I’m sure management’s perspective was that we were all just lazy. We were paid to be there and work, so why didn’t we work as hard as possible? But from our perspective, as long as we met our actual job requirements, there was no reason to be any more efficient.

I sometimes think about those days because my current life is worlds apart. I’m my own boss, and my income, free time and personal success depend entirely on my efficiency. However, I’m also aware that if you’re used to environments with no reason to be efficient, “efficiency” is just a byword for what the boss wants you to do.

Efficiency is a Novel ConceptI mention that experience because across different cultures and social organizations throughout human time, I think the situations where it paid to be efficient were relatively rare.

I can’t find the source now, but I recall reading a book where Western researchers came to investigate a remote tribe that engaged in some subsistence agriculture. The tribespeople surveyed often complained about being hungry, wanting more food. But, to the investigator’s eyes, they seemed, well … kinda lazy. They didn’t do what seemed obvious to the anthropologists, simply growing more crops so they’d have more to eat.

The authors claimed this had to do with the social organization they lived in. Supposing you did grow a surplus of food, you could eat as much as you want. But in the close-knit band you lived in, sharing was required. So distant relatives who were hungry would complain to you to give them some of your food. The industrious subsistence farmer wouldn’t have much incentive to work hard since any surplus would likely be taken away.

As this is beginning to sound like a cloaked libertarian allegory, I think it’s worth pointing out that even in societies with strong social welfare states and progressive redistribution policies, we still get to keep most of the fruits of our labor.

Instead, the point I’m trying to make is that the benefits of efficiency are a rather unusual feature of modern societies and that, at most points in time, we were probably like the “lazy” subsistence farmers who couldn’t see the point of being more efficient. If efficiency seems unnatural to us, it might be because, throughout our evolutionary history, working really hard to generate surplus wasn’t often a sound strategy.

Are You Lazy, Or Is It Your Workplace?Most environments we work in exist on a spectrum. At one end are the dead-end video rental jobs or tribal subsistence farmers where the idea of efficiency is alien and unrewarding. At another extreme are the scenarios where efficiency is obsessed over because any gains are personal rewards.

Work cultures exist on a spectrum too. I previously discussed an interesting description of Japanese office culture, which appears to prize working extreme hours at the office (with the result that employees are often terribly inefficient). On the other extreme are results-only work environments, where pay is exclusively based on performance (but that performance can be difficult to track and assess fairly).

I suspect that when productivity feels like a chore rather than an opportunity, it’s less because we’re intrinsically lazy and more because our environment makes us that way.

The post The Efficiency Mindset appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 19, 2023

I’m 35

Today is my birthday. In keeping with a tradition I’ve now done for half of my life, this post reflects on my life over the last year and my thoughts on the year ahead.

The last year was a big one. I celebrated the birth of my second child, Julia. I finished the manuscript for my second book, Get Better at Anything, which will be published in the spring of 2024. We also spent our first year in our new house, having moved in shortly before my last birthday.

Finishing a book while having a new baby kept me busy. The first few months were a kind of synchronized chaos. I got used to the rhythm of waking up, getting my toddler to daycare, going to the office to write all day, coming home, cooking, cleaning, and getting my son to bed before passing out myself for a handful of hours of intermittent sleep.1

In spite of all that, I found myself less stressed this year than I was the previous year. Reality rarely reflects our anticipations of it. Doing the work was less stressful than imagining it—especially as I wrote more chapters and felt increasingly confident about how it was shaping up.

By May, I had handed in my manuscript and Julia hit her three-month milestone, leading to a relatively relaxed summer. I’ve been taking Fridays off to spend more time at home with my kids. I even managed to do some painting and sketching—something that had been on hiatus for a few years.

Plans for Next Year

Plans for Next YearAside from publishing the book, I have a few things I want to work on next year.

One is to do more of my weekly writing ahead of schedule. While I find essay writing enjoyable, the task has grown since my more informal days years ago. Now, each piece goes through multiple edits, I often do illustrations, and we record podcast and YouTube versions.

The weekly essay writing of the blog isn’t a full-time job, but it’s not trivial either. It tends to absorb a lot of time. This effect is compounded by having kids—even weekends at home can feel incredibly busy. Thus, one experiment I have for the next year is to batch more of my writing so I can deliberately cultivate some longer stretches to work on new projects.

Another goal is to travel more. Between the pandemic and having two small kids, I haven’t traveled as much as I’d like. But I agree with Tyler Cowen, who sees travel as an essential part of his work, not just leisure. Writing for a worldwide audience is hard if you’re always stuck at home.

Finally, I’d like to rebuild some exercise habits that atrophied in the last year. Firmly in my thirties now, I feel there are greater costs to my health and energy levels from having bad habits compared to when I was younger. Since busyness is ever present, just going to the gym “when I have time” is chronically insufficient.

The Path AheadFiguring out what I want to do with my life has never been a single decision. Instead, it’s always been a constant back-and-forth of pursuing new directions and recommitting to old ones.

One struggle I’ve had professionally has been navigating to a more mature phase of my work. When writing Ultralearning, I knew I was documenting a phase of my life that was nearing a close. I will never stop learning new things, but my life was already shifting away from that style of big, bold, public-facing projects. While I have zero regrets about those earlier efforts, I don’t really have the desire to try to repeatedly one-up myself or iterate endless variations of the same challenge.

After Ultralearning, I considered the path of being a serial author. The success of my first book gave me the opportunity to write another. While I’m pleased with how the book ended up, the difficulty of the writing process makes me hesitant of planning to churn out a new book ever year or two.

Going back to do a Ph.D. has also been an option I’ve toyed around with for years. Given that much of my writing has come to rely on academic research, my own lack of credentials may put a limit on my reach at some point. But I’ve also found the bureaucracy and specialization of academia somewhat alienating, so at this point, I’m happy being a dilettante.

Ultimately, the path I end up taking will probably not be entirely premeditated. Instead, it will be a by-product of smaller experiments—writing things I like to read and working on projects I think are interesting. I’m forever grateful for the luxury of being able to take risks like this—something I owe to the readers who have continued to follow my work!

The post I’m 35 appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 8, 2023

7 Expert Opinions I Agree With (That Most People Don’t)

Recently, I wrote a defense of the uncontroversial-within-cognitive-science-but-widely-disbelieved idea that the mind is a computer.

That post got me thinking about other ideas that are broadly accepted amongst the expert communities that study them, but not among the general population.1

I agreed with some of the following ideas before I read much about them; for these, the expert consensus reinforced my prior worldview. But for most, I had to be persuaded. Many ideas are genuinely surprising, and one needs to be confronted with a lot of evidence before changing their mind about it.

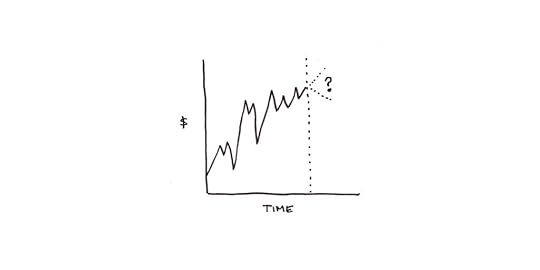

1. Markets are mostly efficient. Most people, most of the time, cannot “beat” the market.The efficient market hypothesis argues that the price of widely-traded securities, like stocks, reflects an aggregation of all available information about them. This means investors can’t spot “deals” or “overpriced” assets and use that knowledge to outperform the average market return (without taking on more risk).

The mechanism underlying this is simple: Suppose you did have information that an asset was mispriced. You’d be incentivized to buy or short the asset, expecting a better return than the current market would dictate. But this action causes the asset’s price to adjust in the opposite direction, moving it closer to the “correct” value. Taken as a whole, the very action of investors trying to beat the market is what makes it so difficult to beat.

Asset bubbles and stock market crashes are not good evidence against this view. (Of all the people who “predicted” a bubble/crash, how many made money from their prediction?) Nor is that friend you know who seemingly made fantastic returns from crypto/real estate/penny stocks/etc. (That’s usually explained by them taking on more risk, and thus having a higher risk premium, and getting lucky.)

The obvious consequence is that for most retail investors, it’s best to put their money in broad-based index funds to get the benefits of diversification and earn the average market return with few fees.

2. Intelligence is real, important, largely heritable, and not particularly changeable.This is one that I fought accepting for years. It goes against my beliefs in the value of self-cultivation, practice and learning. However, the evidence is overwhelming:

Intelligence is one of the most scientifically valid psychometric measurements (far more so than personality, including the dubious Myers Briggs).It is positively correlated with many other things we want in life (including happiness, longevity and income!).It shows strong heritability, with the g-factor maybe being as much as 85% heritable.Finally, few interventions reliably improve IQ, with a possible exception for more education (although it’s not clear this improves g).

I don’t like trotting this argument out. I find it much more appealing to believe in a world where IQ tests don’t measure anything, or they don’t measure anything important, or that any differences are due to education and environment, or that you could improve your intelligence through hard work.

That said, I do think there’s a silver lining here. While your general intelligence may not be easy to change, there’s ample evidence that gaining knowledge and skills improves your ability to do all sorts of tasks. Practically speaking, the best way to become smarter is to learn a lot of stuff and cultivate a lot of skills. Since knowledge and skills are more specific than general intelligence, that may be less than we desire, but it still matters a lot.

3. Learning styles aren’t real. There’s no such thing as being a “kinesthetic,” “visual,” or “auditory” learner.I’ve had multiple interviews for my book, Ultralearning, where the host asks me to talk about learning styles. And I always have to, ever so gently, explain that they don’t exist.

The theory of learning styles is an eminently testable hypothesis:

Give people a survey or test to see what their learning style is.Teach the same subject in different ways (diagrams, verbal description, physical model) that either correspond with or go against a person’s style.See whether they perform better when teaching matches their learning style and worse when it doesn’t.Careful experiments don’t find the performance enhancements one would expect based on the theory. Ergo, learning styles isn’t a good theory.

I think part of why this idea survives is that (a) people love the psychological equivalent of horoscopes—this may be why Myers Briggs is so popular despite a lack of scientific support for it as a theory. And, (b) that some people are simply better at visualizing, listening or more dexterous is a truism that seems quite similar to learning styles. But just because you’re better at basketball than math doesn’t mean you’ll learn calculus better if the teacher tries to explain it in terms of three-pointers.

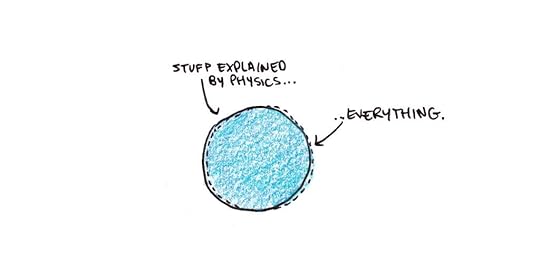

4. The world around us is explained entirely by physics.Sean Carroll articulates a basic physicist worldview that quantum mechanics and the physics described by the Standard Model essentially explain everything around us.

The remaining controversies of physics, from string theory to supersymmetry, are primarily theoretical issues only relevant at extremely high energies. For everyday life at room temperature, the physics we already know does remarkably well at making predictions.

True, knowing the Standard Model doesn’t help us predict most of the big things we care about—even calculating the effects of interactions between a few particles can be intractable. But, in principle, everything from democratic governance to the beauty of sunsets is contained in those equations.

5. People are overweight because they eat too much. It is also really hard to stop.The calorie-in, calorie-out model is, thermodynamically speaking, correct. People who are overweight would lose weight if they ate less.

Yet, this is really difficult to do. As I discuss with neuroscientist and obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet, your brain has specific neural circuitry designed to avoid starvation and, by extension, any rapid weight-loss. When you lose a lot of body fat, your hunger levels increase to encourage you to bring it back up.

This is hardly a radical view, but it’s strongly opposed by a particularly noisy segment of online opinion that either tries to explain weight in terms of something other than calories or, conceding that, seems to assert that the problem is simply a matter of applying a little effort.

One reason I’m optimistic about the new class of weight-loss drugs is simply that, as a society, we’re probably heavier than is optimally healthy, and most interventions based on willpower don’t work.

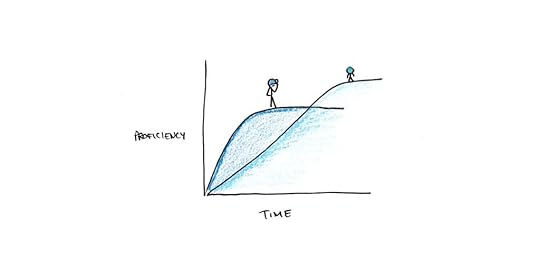

6. Children don’t learn languages faster than adults, but they do reach higher levels of mastery.Common wisdom says if you’re going to learn a language, learn it early. Children regularly become fluent in their home and classroom language, indistinguishable from native speakers; adults rarely do.

But even if children eventually surpass the attainments of adults in pronunciation and syntax, it’s not true that children learn faster. Studies routinely find that, given the same form of instruction/immersion, older learners tend to become proficient in a language more quickly than children do—adults simply plateau at a non-native level of ability, given continued practice.

I take this as evidence that language learning proceeds through both a fast, explicit channel and a slow, implicit channel. Adults and older children may have a more fully developed fast channel, but perhaps have deficiencies in the slow channel that prevent completely native-like acquisition.

This implies that if you want your child to be completely bilingual, it helps to start early. But that probably requires non-trivial amounts of immersive time in the second language. If they’re only going to a weekly class the way most adults learn, then there may be no special benefit to starting extremely young and maybe even an advantage to starting older.

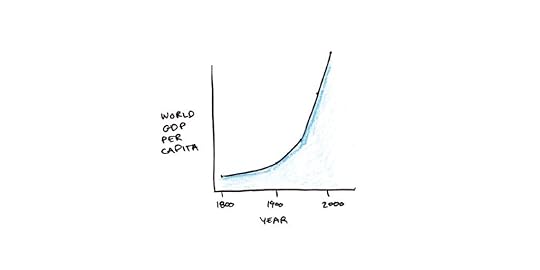

7. We’re better off than our grandparents. We’re vastly better off than our ancestors.Economic pessimism is fashionable.

Everyone I talk to likes to point out various ways that the current generation (at least in North America, where I reside) has it worse than our parents did: houses and college degrees costs cost more, and it is harder to support a family on a single earner’s paycheck.

But pretty much every economic indicator is positive. Even the indicators that pessimistic pundits like to complain about are largely from areas where wages have been stagnant, or inequality has been rising rather than genuine decline.

The world we live in today is wealthier than that of our parents, and fantastically wealthier than it was a century ago. Economic progress is not everything, but it matters a great deal.

This isn’t a call to stop striving and rest on our laurels; many problems in society still require fixing. But a narrative that begins by denying the material progress that has genuinely been made distorts the task ahead of us.

The post 7 Expert Opinions I Agree With (That Most People Don’t) appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 1, 2023

Why I’m Not More Popular

Recently, when I was a guest on a podcast, the host asked me why my book wasn’t more popular. She thought it belonged in the same class as mega-bestsellers like Atomic Habits or Deep Work, and was surprised it wasn’t in the same league for popularity.

While it’s deeply flattering to be told your work is underrated, I think some people’s surprise that a moderately-popular thing isn’t super popular stems from a cognitive illusion.

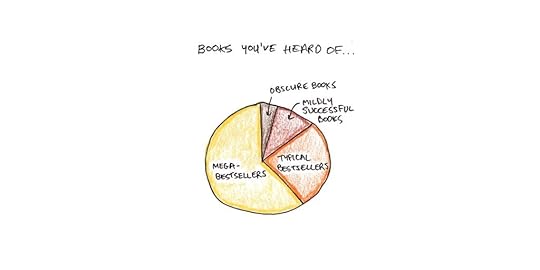

Why Bestsellers Seem CommonTry to imagine every book you’ve ever read, seen or heard about. How many books would that be?

Maybe 1000?

It’s probably not more than 10,000 unless you’re an avid bibliophile or work in publishing.

Now try to guess how many books are actually written. For published books, estimates range from 500,000 to one million books are published every year. Including self-published books, and it’s closer to four million. The Library of Congress has 32 million cataloged books, which is an undercount of every book ever written.

That means every book you’ve heard about, let alone read, makes up less than 0.00003% of all the books that exist!

Furthermore, the books you’ve heard about are not a randomly-selected sample. the likelihood you’ve heard of a book corresponds fairly closely with its popularity in the general marketplace. The average traditionally-published book typically sells a few thousand copies in its lifetime. In contrast, mega-bestsellers sell tens of millions.

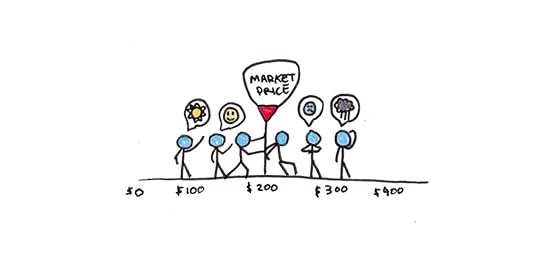

Thus the picture the average reader gets of the market looks like this:

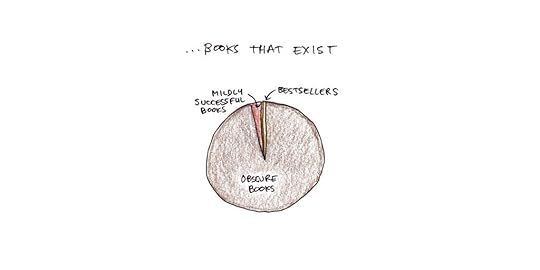

But the reality of publishing is actually this:

The handful of people who (ever-so-kindly) think I’m underrated are probably thinking of a dozen or so popular books of the same genre. Owing to the biases mentioned above, these examples are disproportionately drawn from the pool of enormously successful books. They notice that my book is less successful than that elite cohort and find it surprising.

These people are missing the hundreds of thousands of books similar to mine in quality (or better!) that they’ve never heard of because they aren’t bestsellers!

This analysis applies to any kind of creative work. We watch famous YouTubers with millions of subscribers and ignore the vast majority who have less than a thousand. We hear about research done by elite scientists from Harvard and MIT, but not work by ordinary academics. Music, movies, journalism, athletics and countless other fields suffer from the same distortion.

I’m intensely grateful to have achieved a place where people buy my book and I get invited to be on podcasts. Most people don’t get this much, even those whose work deserves it.

What About Quality? Don’t Better Books Sell More?Of course, books that become bestsellers aren’t entirely random. I’ve been envious of James Clear’s writing ability since before he wrote Atomic Habits, so it wasn’t surprising to me when his book became a major hit. He’s a thoughtful and engaging writer.

While there are snobs who argue that a book’s popularity is a sign of low quality, I think this take reflects particular tastes rather than describing a general feature of the mass market.1

However, even if you try to argue that popularity is perfectly correlated with underlying writing quality, the two scales differ by orders of magnitude.

If writing quality exists on a scale from 1 to 100, book sales range from zero to tens of millions.2Thus, even in a world where writing quality perfectly predicts sales, it is still unfair. Those who are ever-so-slightly better can reap hundreds or thousands of times the rewards.

Almost no one believes that a book’s quality is perfectly predictive of its success. Books succeed in part because of quality, but also because of random factors that neither the author nor an outside observer could easily predict. Those who become phenomenal bestsellers are often just as surprised as anyone that their book has taken off.

What Level of Success Should You Expect?At its heart, this suggests a rather pessimistic downgrading of our ability to succeed in fields like book publishing. If we’re greatly exaggerating the proportion of books that become bestsellers, we’re implicitly overestimating our odds of success.

I think there is some truth to this.

Success at an extreme level is usually the overlap of many competing factors, only some of which are in your control. If your personal definition of success or happiness depends on being in a rarefied elite, this analysis should chasten you to the reality of that goal.

Even if you’re pursuing more modest success, however, thinking this way can help you do better. When success is much rarer than you think, you need to pay close attention to what works, work hard to master the fundamental skills of your craft, and ensure you’re committed to making it work.

Having achieved modest popularity, I’m thankful for everyone who enjoys my work. Whether you think my work is underrated or overrated, I’m endlessly grateful for the opportunity to write about things I find interesting for a living.

The post Why I’m Not More Popular appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 25, 2023

The Mind is a Computer

In my recent call for questions, a reader asked me a version of Peter Thiel’s now-famous interview question: what important truth do few people agree with you on?

I had a hard time answering this because, for the most part, I’m an intellectual conformist. I read what experts think and generally agree with their consensus.

While intellectual conformity may sound cowardly, I’d argue it’s actually a kind of virtue. My professional incentives align with being contrarian rather than dryly repeating whatever Wikipedia says on a topic.

I usually agree with experts because experts are regular people who have learned a lot about a topic. If regular people tend to coalesce around a certain worldview after hearing all the evidence, it’s probably because that worldview is more likely to be correct!1

A side-effect of this habit is that conforming to experts’ thinking sometimes puts you wildly out of step with most other people.

Non-expert opinions often sharply diverge from how experts see a subject. So when you read a lot about a topic, and your opinion converges with the typical expert view, it can diverge from the commonsense view of reality.2

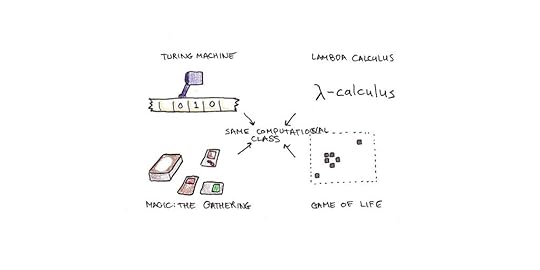

Consider the idea that the mind is a kind of computer.

This is the central assumption of cognitive science and represents an orthodox view within psychology and neuroscience. There are caveats and dissenters, to be sure. Still, faith in the information-processing paradigm of the mind is far more prevalent among people who spend their entire lives studying it than the average person on the street.

Why the Mind is a Kind of ComputerThe classic rhetorical trick amongst skeptics of this view is to point out the history of analogies for the brain. The ancient Greeks saw the mind as a chariot pulled by horses of reason and emotion. René Descartes viewed the brain as a system of hydraulics. Every age, it is argued, has fumbled for the best metaphor for the brain and ours is no different. Just as the idea that pressurized fluids manage the brain seems silly today, so will a future era see the computer analogy as quaint.

But there is good reason to think the computer analogy is different.

This is not because brains are literally similar to a laptop. Instead, it is because computer science has discovered that computation is a relatively abstract property, and many completely different physical devices share the same constraints and powers.

Alan Turing and Alonzo Church each independently discovered that the former’s Turing Machine, a hypothetical instrument that followed instructions on an infinite ticker tape, and the latter’s Lambda Calculus, a mathematical language, were formally equivalent. Since then, many seemingly unrelated systems have been proved formally equivalent—from Conway’s Game of Life to the Magic: The Gathering card game.

The extended Church-Turing thesis argues that this isn’t a coincidence. Any physical device, whether a brain, laptop or quantum computer, broadly has the same powers and constraints.3

Saying computers are “just a metaphor” for the mind is misleading because it restricts computers to the Von Neumann architecture used in silicon computers today. But the abstract concept of a physical device that processes information is much broader and more powerful. The heart differs from a bicycle pump, but is obviously a member of the abstract class of “pumping machines.” In the same way, the brain is quite different from a laptop, but they’re both members of the abstract class of “information-processing machines.”

The point isn’t to elide any difference between the digital computers we manufacture and the biological computers we’re born with. Instead, it’s to recognize that if you wanted to understand the heart but were somehow philosophically opposed to thinking of it as a kind of pump, you would have a hard time making sense of how it works.

But What Kind of Computer?Saying the brain is a kind of computer is like saying bacteria and people are both organisms. The latter is also uncontroversial within biology today, even though the idea would have seemed fantastical two-hundred years ago. At the same time, bacteria and people are different.

Clearly, the brain differs in many ways from the transistor-based computers we are familiar with:

The brain is far more complicated. The human brain has ~100 billion neurons. Each individual neuron has sophisticated computational properties that can require a supercomputer to model. While a bacteria and a human differ in more than just size, the scale of things is a significant distinction. Bigger is different.The brain is massively parallel and interconnected, having as many as a quadrillion synapses. Modern computers have a serial architecture where computation goes through a central processing unit.4 In contrast, brains distribute the calculations across the entire neural network. This difference changes the algorithms that can be used, which is why human thinking is qualitatively different from computer code.Bodies have sensory inputs and motor outputs that interact with our environment. The human brain has billions of sensory cells and billions of motor effectors, each of which engages in feedback loops with the environment. This is a major contrast with most human-built computer systems which are essentially detached from the world except for small windows of input and output.These differences aren’t trivial. But, just as a single bacterium and a human being are both organisms, I think it’s worth stressing that even these great differences don’t alter the fundamental truth that the mind is a type of computer.

What About Meaning, Emotions and Subjectivity?Within psychology and neuroscience, the dominant controversies are over what kind of computer the mind is rather than whether or not it computes. But I think the more typical objection to this viewpoint from people outside those fields is a humanistic one. Essentially, the objections are:

Computers are logical; humans are emotional. The cognitive scientist would counter that emotions are a kind of computation. Motivation, attention, fear, happiness and curiosity are all important functional properties. While the nature of the algorithm isn’t transparent to us via introspection, this is broadly true of all of our cognitive processes.Computers aren’t sentient; humans have consciousness. I agree with Daniel Dennett that philosophical ideas like qualia, p-zombies or the impossibility of knowing what it is like to be a bat are misleading intuitions. The “hard” problem of consciousness-as-subjectivity is a confusion, not a genuine puzzle. In contrast, while the “easy” problem is still unsolved, there’s been considerable headway in explaining how consciousness-as-awareness works.Computers are rule-governed; human thinking is holistic. Hubert Dreyfus famously made this argument against the computer analogy back when the serial-computer model was more prevalent in artificial intelligence. However, I think the “what kind of computer?” framework above largely resolves this issue. Presumably, the brain’s sheer quantity of processors and enormous parallel activity explain the powers (and limitations) of intuition and holistic thinking.Who are we to think we can “understand” the soul? The final objection is simply an appeal to mysticism. I’m not principally against this—if you’d prefer to dwell in the mystery of life rather than try to figure things out, that’s a reasonable choice. But obviously, it’s the antithesis of the aims of science.We know less about how the mind works than we know about, say, microbiology. But, just as vitalism was proved false and life really is just chemistry, I’m convinced the mind really is just a computer and that the ongoing scientific project of figuring out how it works is one of the most exciting pursuits of our time.

The post The Mind is a Computer appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 18, 2023

Reader Mailbag (Part II): Overcoming Procrastination, the Input Hypothesis, Time Management and Motor Skills

Two weeks ago, I asked the audience to send me their questions. The response was great, so I decided to split my responses over two posts. You can see last week’s answers here, where I talked about Range, learning styles, nootropics and the value of learning things you’re doomed to forget.

Some questions have been lightly edited, and questions that multiple people asked have been merged into single questions.

Q: How can I overcome procrastination?

(multiple readers)

The research on procrastination indicates that we mainly fail to buckle down and get to work (or our studies) because we find the task unpleasant, and putting it off is more immediately rewarding than getting to work.

This seems a pretty banal observation, but it’s important to note what it excludes. The research does not, for instance, find that perfectionism is strongly associated with procrastination (something widely believed). Nor is anxiety clearly associated with more procrastination (if you’re anxious, you might even work harder!).

In terms of overcoming procrastination, I think this is why developing a productivity system—some kind of guiding framework that tells you what to work on and when—is so valuable. Over time, if you stick to the system, the decision of what to work on gets delegated to that system, and you learn to abide by it. That alone eliminates a lot of excessive procrastination.

However, I think it’s also important to point out that procrastination is often useful! Our motivational hardware is designed to balance many competing interests and needs. A person pathologically incapable of procrastinating would also likely be willing to stick out working on a lot of tedious, low-value tasks.

While we want to keep our procrastination to an adaptive (rather than maladaptive) level, you should also embrace some of it as your motivational system functioning properly.

Q: What do you think of Stephen Krashen’s Input Hypothesis?

(multiple readers)

Krashen’s Input Hypothesis is an influential (and controversial) language learning theory arguing that exposure to lots of language you can understand is both necessary and sufficient to achieve completely fluency in a language.

Additionally, Krashen has argued for a distinction between learning a language and acquiring a language, arguing that languages cannot be practiced (thus, there’s no value in encouraging people to speak a language), nor can they be taught (thus, there’s no value in explaining grammar or correcting people’s mistakes).

Judging from the sidelines, I’m somewhat baffled by the theory’s popularity. Consider:

For most skills, instruction tends to outperform unguided learning. The literature reviews for language learning show… the same thing? Yet this evidence is dismissed by proponents of Krashen’s view as evidencing “learning” and not “acquisition.”People in input-only learning environments tend not to acquire native-level productive fluency in a language. This suggests that the speaking part of immersive learning isn’t superfluous.Adults and adolescents over the age of 10-14 rarely achieve completely native proficiency in a language, despite decades of full-time exposure. Krashen’s theory attributes this to an “affective filter” that prevents pure input from working its magic. It seems implausible to me that this can explain the near-universal success of six-year-olds in acquiring their native language but exceedingly rare odds of twenty-six-year-olds in achieving native-level pronunciation and grammar.We already have a good idea of how we acquire implicit, fluent knowledge in other skills. Why would those same laws of skill acquisition not also apply to language learning? Even if there are language-specific mechanisms, it seems likely that adult language learners can also benefit from skill-learning systems.Outside of academic circles, Krashen’s theory mainly influences language learners who prefer to read and listen as their primary method for learning instead of practicing conversation.

Despite my preferred approach, I’m not against such approaches. Given that opportunities to speak a foreign language can be limited, you probably can go quite far just by reading and listening a lot. Even so, I think some speaking practice and formal instruction are also helpful for most learners.

Q: I find myself struggling with anxiety/depression, and it makes it harder to work on my key goals. What should I do?

(multiple readers)

My first suggestion in all these situations is that if you’re struggling with obsessive, negative thoughts, seek therapy if you can, particularly therapists that work with cognitive-behavioral therapy, as it tends to have the greatest empirical support.

CBT tends to perform similarly to pharmaceutical treatments (which also seem to work well, so many people benefit from both). The basic idea behind CBT is that we can get into recurring patterns of thinking, feeling and action that mutually reinforce.

For instance, a person with social anxiety might have unpleasant feelings about going to a party. This triggers vivid imaginings about what might go wrong (maybe they say the wrong thing and embarrass themselves). The anxiety builds until they cancel the invitation and stay home. That causes some momentary relief, but it reinforces the thought and behavior patterns that led to that avoidance and entrenches the anxiety further.

Learning to notice and disable those patterns can be a major step to reducing their grip on you. If you cannot access therapy, I recommend reading more about cognitive-behavioral approaches so you can get the gist of what the work might look like.

Still, I’m not a clinical psychologist, so what I say is not medical advice and ought to be taken with a grain of salt.

Q: What do you think is a more effective approach: managing your day by tasks or managing your day by time/schedule?

– Tavan

I used to be a wholehearted advocate of the task-based approach: Make a daily to-do list and work on it until it’s finished.

The benefit of the task-based method is that it focuses on getting work done. I find it works well when you have a bunch of predictable tasks that need doing, there’s no pressing need to “do more” toward your projects, and you may have a strong urge to procrastinate. Ending when your tasks are done creates an incentive to get everything done so you can enjoy the rest of your day.

However, this approach can struggle when the projects you’re working on are open-ended, or the tasks you’re trying to work on are hard to predict in advance. In those cases, I rely on a fixed-schedule approach to productivity.

I think the issue of productivity systems is that there probably isn’t a good universal system. Instead, different approaches work better or worse, given your typical tasks and goals. As a college student, I found the task-based system worked well. But I find it breaks down in other environments. Similarly, Cal Newport’s time-blocking system works well when you’re intensely busy and have many appointments on your calendar, but it may feel like overkill if you can get your work done without it.

Q: I am curious to learn more about how blocking eyes might affect motor skill learning. A piano player or tennis player that do drills blindfolded or with one eye covered.

– Ola

I’m not sure! My understanding of the motor skills literature is somewhat weaker than other aspects of educational psychology.

I know that when I was learning to touch type, we taped a sheet of paper at the top of the keyboard and typed underneath to prevent us from looking at the keys. That encourages you to look at the document you’re transcribing and memorize the key positions directly. However, many other skills seem innately coupled to a visual/kinesthetic feedback loop, so doing it blindfolded would likely cause performance to deteriorate for an unclear purpose (I wouldn’t ski down a mountain blindfolded, for instance).

I can say that introducing novel constraints is often a good way to “shift” a motor pattern into a new equilibrium that would be hard to achieve through conscious effort alone. There’s interesting research showing that people tend to acquire movement skills better when they focus their attention on the goal of a movement rather than the movement itself. This suggests clever constraints may be beneficial to shift you out of a bad habit.

_ _ _

Thanks to everyone who submitted a question to the reader mailbag. I had lots of fun discussing everything with readers. Hopefully, we can do it again soon!

The post Reader Mailbag (Part II): Overcoming Procrastination, the Input Hypothesis, Time Management and Motor Skills appeared first on Scott H Young.

July 12, 2023

Reader Mailbag: Range, Learning Styles, Nootropics and the Value of Learning Things You’re Doomed to Forget

Last week, I sent out a call for questions to subscribers to my newsletter. I got many good ones, so I decided to split my responses into two separate posts.

Some questions have been lightly edited, and I merged similar questions that a few people asked. Chatting with readers is always fun—hopefully, we can make this a regular feature!

Q: From the bits of work I’ve read of yours, you seem to be an advocate of focused, targeted, and possibly quite isolated (individual study) learning. Also, learning things that generally have answers—technical maths-based subjects, languages, etc.

Have you read Range by David Epstein?

What’s your view on learning through trial and error, experiment, sense-making of existing past experiences that were not targeted but they happen to already be a part of you—(constructing them into your own personal specialism)?

-Jim

Range is a funny book for me because, in some ways, I’m the epitome of its thesis. I’ve learned a great deal of unrelated things and done a lot of random self-exploration. I write a blog about learning, in part because I’m too fickle to stick to any one thing and master it completely.

That said, I think there are some broad empirical findings from educational and cognitive psychology that we need to keep in mind:

Students tend to learn better in more guided and structured programs. Despite their appeal, unstructured, discovery-based approaches tend to underperform against more direct teaching methods unless you’re stacking the deck in their favor. That doesn’t mean learning through discovery is useless; simply that the effectiveness of learning through pure discovery doesn’t have the evidence base people often claim it does.Transfer between unrelated skills tends to be fairly low. Learning tons of random things might have some benefit, but given the almost complete lack of “far” transfer in carefully controlled studies, I would say that the burden of proof is upon the person claiming transfer is large rather than the reverse.Ill-defined skills (I think that’s what you’re talking about when you’re contrasting it to learning things that have an “answer”), I don’t believe are different from well-defined skills. Indeed, a lot of what learning is is making a skill well-defined. If you don’t know anything, the problem space is huge, and you are unsure of tons of possibilities. As you learn more, you find better ways to represent problems and better ways to solve them.I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being a generalist and learning lots of things. Life’s about more than optimizing for a singular goal.

Q: Do you have any tips or strategies to learn more efficiently from books you read?

-Issam

I think the most important thing is just to read more. Reading more improves your fluency and background knowledge, which increases your reading rate. People really underrate how much reading a lot improves your reading speed.

Q: What about learning styles? Is being a “visual learner,” etc., a real thing?

-Chip

Probably not.

Daniel Willingham has a great summary of the evidence against the idea that people have learning styles. To be a true “style,” it should mean that people learn better when information is presented in their preferred modality. Studies generally don’t find increased learning gains from tailoring information in this way.

Q: How many things can we learn at one time? Should we just pick one thing and get to a certain level and then move on to others, or can we learn multiple things at the same time? Does it overload our brain, or is it capable of handling so much new info?

-Charitha

You can definitely learn multiple things in the same timeframe. Most of primary and secondary schooling is based on this. I tend to discourage multiple, concurrent self-directed learning projects because most people overestimate what they can accomplish and end up with several weak projects instead of one effective one. But there’s no cognitive reason preventing it.

I think learning highly similar subjects in tandem can create issues. I’ve never attempted to learn two new languages simultaneously, although I recommend practicing multiple languages in close succession for maintenance.

Q: Do you have any supplements that you swear by for focus and productivity?

-Gareth

Caffeine? Honestly, not really anything.

I’m not convinced about nootropics as something that could plausibly work with no downsides. For nootropics to make sense, you’d have to believe that the brain could work better than it does, but the internal dials dictating its performance are simply set suboptimally. But why would evolution build a brain like this? If turning a dial could increase performance with no downside, evolution would have done so already.

My guess is that the true learning/focus enhancers will either have clear downside risks (e.g., amphetamines), or they’ll be targeted toward a particular deficiency/disability but not effective for the general population. I’d be happy to be proved wrong here, but I’d need to see a lot of good evidence first.

Q: I know some French as I lived in Quebec but left 30 years ago. What is the fastest way to learn it again in preparation for a trip to France in a few months?

-Harisch

Book some tutoring time with iTalki and try chatting again.

For relearning, most of the issue is low fluency and self-confidence. It’s less work since the knowledge is probably already in your head—it’s just not as automatic. A few lessons should help you feel more fluent, which will also help with confidence which can be a big part of speaking a language.

Q: If you had to do the MIT Challenge all over again knowing what you know now about the scientific literature on learning, productivity, etc., what would you have done differently and why?

-Jeff

I initially dreamt up the MIT Challenge as, “I wonder if you could learn all the CS courses MIT teaches?” and then further, “I wonder if I personally could do it in 12 months if I just focused on the exams.” As such, it was somewhat contrived since the aim was passing exams rather than acquiring the skill for a particular purpose. I’ve said as much over the years, but the project would have looked entirely different if my end goal had been landing a programming job, launching a start-up, or becoming a researcher.

In terms of what I know now, there are a few things I can see as weaknesses that could have been remedied with a different approach. I passed a lot of exams by having a decent conceptual understanding. Still, my procedural knowledge of algebra/calculus was weak, which led to me struggling with the physics-based classes with a lot of math to wade through to compute the answer. If I did this project over, I’d do massive drills to build up that fluency, maybe as a prerequisite project to starting the challenge itself.

Similarly, while I did the programming projects, the MIT CS degree was light on actual programming. It was a lot more theory and math. That’s fine, but if I had intended to land a programming gig right after, I’d have spent a couple months going deep on a particular language, ensuring I could fluently implement a lot of ideas I had covered.

Overall, I’m not sure I would have changed much about how I studied. The timeframe constraints didn’t leave much wiggle room to do things wildly differently. But if I had the broader goal of learning programming or computer science, I could imagine a lot of different approaches that might have better results for some purposes.

Q: Why do I enjoy reading nonfiction since most is forgotten? Why do we test high-school students on content “finals” when we know most of the material will be forgotten?

-Rob

Things are forgotten, but they often still influence us in an impressionistic way. I often find my beliefs have been shifted in a direction even though I no longer recall the exact source of the argument. Some of what reading books does is shift your intuitions about situations in ways that don’t always leave a trace back to their source.

_ _ _

That’s it for this week. Next week, I’ll tackle some more questions including overcoming procrastination, my thoughts on the contentious input hypothesis in language learning, motor skills and more!

The post Reader Mailbag: Range, Learning Styles, Nootropics and the Value of Learning Things You’re Doomed to Forget appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 27, 2023

Eight of My Unanswered Questions About the Best Way to Learn

I spend a lot of time thinking about how we learn.

I’ve read hundreds of books and articles on the subject and written scores of essays—and a book!—attempting to summarize and synthesize expert perspectives on the best way to do that. Yet there’s still a ton I don’t know!

Today, instead of offering answers, I’d like to pose some questions I still have. I’ll frame each question in terms of a specific topic, but each likely speaks to a broader issue that impacts other skills and subjects.

My Unanswered Questions1. When learning a broad subject, like history, how much time should be spent on retrieval practice versus new reading?I’ve written before about the value of retrieval practice over re-reading. Give students an essay to read, and they learn more when they practice free recall of the essay’s contents than if they re-read it again.

But the research here focuses on re-reading the same essay again. What about reading a different source? If you’re studying a broad topic like history, do you learn more from retrieval activities or reading many other books and sources?

2. Is it better to first watch a foreign language film with subtitles or without?Say you’re watching a film in a language you are learning. You aren’t to the point where you can understand what’s happening from the first viewing. If you’re going to watch more than once, should you watch with subtitles on the first or second viewing?

The argument for the first viewing would be that you’d understand the plot and thus could better assimilate language on the second viewing. The argument for the second viewing is that you’d attend to the words better and process them for meaning.

3. Should you start by struggling on challenging math problems or simply view the instructions?This isn’t just my question—it’s a hotly debated area of educational research. Manu Kapur’s productive failure experiments argue in favor of presenting difficult-to-solve problems first. In contrast, others’ experiments on cognitive load theory argue in favor of starting with explicit instructions.

Both theories support problem-solving as you gain expertise, as it provides needed practice. But the question is whether beginners, who are unlikely to know the correct solution beforehand, benefit more from problem-first or examples-first approaches.

4. How many words in a new language should you study via flashcards?I’m a big fan of learning vocabulary with flashcards. At my peak, I had around 16,000 cards for Mandarin and several thousand for Korean and Macedonian.

Memorizing the central meaning of a word is much faster to do via flashcards than incidental exposure. Yet a flashcard only teaches you part of what you need to know about a word. You can’t get a feel for when the word is likely to show up or what words it goes with, and you need practice to recognize and use it in context.

My hypothesis is that flashcards are useful—but only to a point. Common words are good to learn, as are some uncommon ones. But how far should you go? The most common 100, 1000, or 9000 words? Should you focus on single, core meanings or quiz yourself on variations (e.g., one card for “divide” versus cards for “divide,” “division,” “divisive,” etc.)

Learning a new word incidentally is almost always slower than learning it deliberately. Still, it has the added advantage of the complete context, plus additional practice on the other words in the context. At some point, learning words “in context” will probably become more efficient than rote memorization. The question is where this trade-off point occurs.

5. If you’re learning to ski or snowboard, do you learn faster if you stick to the easy slopes and perfect your technique or take on the steepest slope you can comfortably manage?For cognitive skills, there’s support for getting the method “right” from the beginning. If you learn a mathematics algorithm incorrectly, there are few opportunities to self-correct that knowledge later.

However, there seem to be different schools of thought for physical skills. One school would argue for perfecting the “correct” technique before moving on. This is the view that sloppy technique is hard to fix later, so it should be mastered before taking on harder challenges.

Another school would argue that once you’ve intellectually understood the technique, you benefit more from practicing in difficult/varied situations rather than trying to perfect it in an easier setting. Yet those complex settings likely to introduce errors and thus lead to long-term headaches.

6. How useful is learning academic computer science for a successful programmer?This question has been on my mind since my MIT Challenge. On the one hand, knowledge of number theory, analysis of algorithms and logic play a role in programming practice. On the other hand, who has ever sat down to prove the complexity class for a problem before they begin working on it?

This question of the relationship between academic theory and practical skills shows up in many fields. Opinions on academic relevance range from, “Of course, you need to learn that!” to, “Nobody has ever used this on the job.”

Possible answers include:

It helps, but mostly with advanced work, not entry-level work.It helps by making the practical skills “make sense,” assisting with future learning.It doesn’t help much with programming, but it helps you land a job.It’s less efficient than simply learning programming directly.7. Do you gain greater chess proficiency by playing slower or faster games?Say you want to increase your chess score rapidly. Should you focus on longer games, where there is more time to think for each move, or faster games, which have less time to think, but you end up seeing more board positions for each hour spent playing.

I suspect both ends have an extreme where learning benefits break down. Spending a year per game, or spending less than a second per move, is probably not efficient. But where does the optimal point sit in between?

While this question matters for chess, of course, definitively answering it would say a lot about other skills which can be done at varying “speeds” and have trade-offs between depth of analysis and quantity of exposure.

8. If you want to paint in a “loose” style, should you first learn to paint with “tight” control?Similar to playing chess fast and slow is the question of cultivating an artistic style. Suppose you want to paint in a “loose” or “painterly” fashion. Would it make sense to learn with greater control first and then loosen up as you gain experience, or should you paint relatively loose from the start?

The argument for starting with greater control is that much of what we like in skillful, loose painting styles is that the artist can communicate much with an economy of movement and brushstrokes. Beginners can’t do that, so they’re better off learning the fundamentals and loosening up as they get better.

An analogy for this might be math: An experienced mathematician can simply shout out the answer to a complex question, whereas a beginner would need to do the calculations ploddingly by hand to get that same answer. We would never expect just shouting out an answer to be a way for a beginner to gain the expert’s knowledge.

The argument for starting looser is that the skill of controlled painting is different from looser works. So stylistically, an early focus on control may make it harder to develop a successful, loose style later.

What are Some of Your Unanswered Questions?Those were some of my unanswered questions—what about yours? What are you unsure about in the process of learning? Do you have any opinions about the questions I’ve posed–share your thoughts!

The post Eight of My Unanswered Questions About the Best Way to Learn appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 20, 2023

When are Minimal Habits Useful for Learning?

In last week’s essay, I wrote about the problem of being overly patient in learning.

In particular, I singled out learning projects based on simple, minimal habits—say, learning a language by spending five minutes a day on Duolingo, or writing one page of a novel every week.

To recap:

While popular, this approach limits the types of activities you can do, often eliminating the most efficient kinds of practice. The long time frame makes it hard to tell if you are making progress and hard to adjust your approach accordingly. Finally, while setting up easy habits can be a good stepping stone into a difficult behavior, for many, the five-minute-per-day routine becomes a destination rather than a warm-up.While the minimal-habit approach has problems, I should note that there are problems with intensive projects too! Intensive projects are hard to schedule, challenging to execute and may lack sufficient spacing for long-term retention.

The best approach isn’t to steadfastly stick to a particular format for working on a goal but to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each. So, today I’d like to explore what sorts of learning minimal habits are actually useful for.

What are Minimal Habits Good For?The minimal-habit approach to learning, provided you can sustain it over long periods, has two key advantages: spacing and convenience.

Spacing refers to the spacing effect, a well-studied phenomenon. We retain information better when there are longer intervals between when we are exposed to it than when the same amount of exposure happens over a shorter amount of time. Thus, seeing a vocabulary item ten times over ten days will result in more durable memory than seeing it ten times in one hour. By drawing out learning over very long timeframes, minimal habits can potentially take advantage of the spacing effect and, thus, result in more durable memories than crammed schedules.

The second advantage of minimal habits is that they’re convenient. As I mentioned in the previous essay, it feels mean to discourage people from cultivating minimal habits since the alternative is often to do nothing. Life is busy, learning is hard, and sometimes you only have ten minutes to spare.1

Given these two advantages, I think it’s worth examining what types of learning aims might be appropriate for a simple, minimal habit spread over a very long time.

When Should Minimal Habits Work?Based on my mental model of minimal habits, I would expect them to work when the practice activity has low cognitive load and can be fit into a small space of time.

The basic idea behind cognitive load theory is that information must make its way through a narrow bottleneck of conscious experience for learning to occur. Complex subjects and skills, those with many pieces of information that must all be put together before you can understand them, create a high cognitive load. This is one reason why learning mathematics and physics is difficult.

However, cognitive load isn’t constant for a subject! As you learn, your brain uses mechanisms, such as chunking or retrieval cues, to minimize the burden on your working memory. For example, when you first learn to read, it has a very high cognitive load because you must work to recognize each letter. But eventually, the cognitive load of reading becomes low as you automatically recognize words and sentences.

New learning varies in its demands on working memory. Some skills and concepts are intrinsically higher in cognitive load since they have many new, interacting parts. In contrast, other ideas are essentially isolated from each other and can be learned one at a time.

Consider learning to calculate quantum-mechanical orbitals in chemistry versus memorizing masses on the periodic table. The former has a lot of pieces of information that all need to be used simultaneously to perform the calculation. In contrast, the memorization task involves (mostly) unrelated facts.

In light of this, flashcards might help you memorize the periodic masses, but they wouldn’t work well for learning to solve the differential equations to find electron orbitals. The kinds of problems in the calculation task require that you “load” a lot of information into short-term memory so that, for all but the most seasoned chemists, the effective practice activity would look more like a problem set that you must focus on for some time.

Minimal habits are probably better for maintaining knowledge and fluency than moving to a new skill frontier. Continued, repetitive practice spaced over time is ideal for boosting fluency, but it’s less effective for making deliberate adjustments in the presence of corrective feedback.

Thus, a low-key daily writing habit will probably make writing easier, but it may not help you reach a substantially higher level of proficiency. The latter would presumably require deliberate practice constraints that force you to use styles or structures that don’t come automatically and require a certain amount of focus and effort (and likely some outside feedback). This is difficult, or impossible, to sustain as a minimal habit.

The other constraint on minimal habits is that the practice activity needs to fit—and be effective—in a sliver of time each day. Thus downhill skiing, for instance, probably can’t be made into a minimal habit by most people since it requires a lengthy trip up a snowy mountain before you can get some runs in. Many skills are difficult to practice minimally because no relevant kind of practice will fit into that timeframe.

Some Examples of Where Minimal Habits Might WorkI’ve used minimal habits in the past—both effectively and ineffectively. The theory articulated above spells out where I think they work (and where they fail). In particular, I think minimal habits might work well for:

Broad subject knowledge. Daily blog reading, educational YouTube videos or skimming a relevant subreddit will not produce expertise. Still, it can give you good coverage of the main ideas, even if you’d need serious practice to become proficient in using them.Flashcards and memorizing isolated facts. Things that can be made into atomic, independent pieces of quickly-testable knowledge are also good candidates. I’ve successfully used fragments of time to learn a lot of vocabulary, and it can be good for maintaining knowledge, too.Fluency and maintaining established skills. Keeping effort minimal can help build fluency with material, a non-trivial part of eventual mastery.In contrast, I expect minimal habits to be poorly suited to situations requiring deliberate practice; learning new, complex skills; or when effective practice is not possible within the time/effort constraints demanded by the minimal habit.

It’s important to note that the patient/impatient distinction is often dwarfed by the larger consideration of time actually spent learning. According to some reasonable estimates, mastery of a language can take 500-2000 hours of classroom time. If you were to follow the five-minutes-per-day approach with a “hard” language, like Mandarin, that would mean almost seventy years before you hit that threshold! If you don’t actually practice enough, even the most efficient learning strategy won’t get you there.

The post When are Minimal Habits Useful for Learning? appeared first on Scott H Young.

June 13, 2023

The Problem with Being Too Patient

Mastery is often associated with patience. After all, getting good at things takes a long time, and only those who are in it for the long haul can expect to reach the pinnacle of their craft.

Given that common association, I found it interesting to hear the opposite perspective from Butch Harmon, Tiger Wood’s coach during the best years of his golfing career:

Those golfers who insist on being patient and letting the game come to them rarely play up to their potential. They play well, maybe win a time or two, but they never reach the great heights their talents dictate. The players who want to learn, get better, and win right now—this second, no waiting—are the ones who exceed their natural abilities and become the game’s great overachievers.

Harmon later goes on to explain why Tiger was one of the least-patient people he had ever met:

When Tiger wants to do something with his golf swing, he wants it done now. No phasing it in and no long-term planning. Once he decides to make a change, he makes it fully and immediately. Then he works himself ragged until he perfects it, exhibiting little or no patience along the way.

In Harmon’s view, patience was often wishful thinking: the hope of future proficiency preventing you from really working today at what you want to improve.

The Five-Minutes-Per-Day Problem and Learning Hard ThingsHarmon’s quote made me think about a phenomenon I’ve often seen in self-improvement circles. It is the idea that what matters most for learning is doing a tiny bit of something, every day, over a long period of time.

This approach is exemplified by the language learner who plans to become fluent in a language by playing on Duolingo for five minutes a day, the would-be novelist who commits to writing one page a week, or the aspiring photographer taking one picture a day.

It feels mean to be discouraging of this approach. After all, most people do nothing toward their aspirations, so doing something, even a little bit, is better than nothing. Isn’t it?

However, I can’t help but feel that this approach is akin to the wishful thinking exemplified by Harmon’s “patient” golfers—people who used the slowness of eventual mastery to dodge the demanding work of learning.

The Logic of Minimal HabitsAt this point, it’s probably helpful to revisit why this approach is so popular in self-improvement circles. Atomic Habits, a fantastic best-seller written by my friend James Clear, is one of the most obvious proponents of the “start small” approach to self-improvement.

The logic of habit-building is compelling:

Starting is hard.Small habits are easier to commit to.Once you start, it’s easier to ramp up and do more.Thus, the logic goes, the person who does ten minutes a day on Duolingo is building momentum for a larger habit of practicing speaking with people. By lowering the bar for entry, they begin the self-improvement process, while having high expectations may have made it too hard to get started.

Phrased this way, the logic of minimal habits is undeniable. I think it’s an important behavioral technique for getting started with anything, especially when the thing you’re trying to do feels unpleasant. I have used this approach to get back into exercising when I haven’t felt like doing so. I would never criticize someone for starting with smaller, enjoyable habits to break into something they find frustrating or unpleasant but want the outcomes of.

My concern is with #3. Theoretically, it’s easy to ramp up and do more once you’ve started. But in practice, the minimal habit often becomes the destination, not a warm-up for something bigger. And I’m skeptical that such “patient” approaches to practice will reliably result in substantial improvements.

How Effective is the “Patient” Approach to Mastery?I’m not aware of any research that specifically pits “five-minutes-per-day” habits against more typical curricula for skills people want to master. The costs and difficulties of longitudinal studies mean that empirical research is generally somewhat scant over extended time frames.

The spacing effect in psychology would seem to support the slower, patient approach. Memories tend to be more durable when there are longer intervals between reviewing information than when the same review is massed together (as when cramming for a test). However, real-world studies of language learning tend to find the opposite, finding that more intensive curricula have the edge over more stretched-out approaches.

My guess is that which approach is more effective, whether five minutes daily or intensive bursts, depends on the exact nature of the skill being learned, the practice activities used, and the knowledge the learner begins with. I suspect that complex skills favor a more intensive approach, whereas broad, knowledge-based subjects tend to favor a more patient approach.1

However this kind of analysis is probably beside the point because, in general, the sorts of things people do for learning when they opt for a five-minute daily habit are categorically different from those they would do in a typical classroom setting or as part of a focused learning project.

Here, “patient” approaches suffer from several serious drawbacks:

Limited time constrains the types of practice you can do. In five minutes a day, you can complete an exercise on Duolingo, but meaningful conversation practice needs more time. Watching a video of someone painting can be done in five minutes, but replicating that painting yourself takes more time.A focus on “sustainability” avoids necessary effort. When you pick activities designed to be sustainable over months or years, there’s a bias against picking anything too effortful or time-consuming. This eliminates a lot of the intense, deliberate practice needed to achieve mastery.Long timeframes make it harder to tell if you’re making progress. Improvement is evident when you’re learning a lot over a few months. If you’re not making progress, you change your approach. When improvement is something expected to occur years in the future, how do you know if you’re actually getting better at the underlying skill?For these reasons, I’m skeptical of many of the proposed plans I’ve heard from readers to achieve mastery via simple, long-term habits.

Mastery is Slow—and ImpatientIn his research on deliberate practice, Anders Ericsson articulated the view of mastery that most closely corresponds with my own. He argued that mastery is a slow process, and also an impatient one:

Mastery is slow because it takes a long time. No, my book is not an exception to this. I do think it’s possible to learn more efficiently, and that effectively-designed projects can help people accomplish more than they think possible. But genuine mastery (not just relatively quick intermediacy) requires a long time, and nothing I’ve worked on is an exception to that rule.Mastery is impatient because the work required is deliberate, effortful and striving. Deliberate practice was Ericsson’s term to describe the kind of learning efforts put in by elite performers in chess, music and athletics. It clearly describes Tiger Woods, Harmon’s most famous student.I believe this is true even if you don’t aspire to world-class greatness. Even getting “good enough” requires a level of commitment that’s difficult to reach with minimal habits alone.

The post The Problem with Being Too Patient appeared first on Scott H Young.