Scott H. Young's Blog, page 11

January 2, 2024

5 Ways to Make Studying Fun (Without Sacrificing Effectiveness)

Learning requires focus. The reason is simple:

Learning is a process of building long-term memories. You form long-term memories of what you pay attention to.Attention is limited. You can’t pay attention to multiple things at once.But just because learning demands our focus doesn’t mean it can’t be enjoyable. Many activities put strenuous demands on our attention but we enjoy doing them anyway: video games, sports, puzzles and more.

The opportunity cost theory of effort helps to explain the discrepancy. According to this theory, because our attention is limited, the motivational circuitry in our brain is constantly evaluating if what we’re paying attention to is a good use of this limited resource. Think of it like a busy manager trying to decide which jobs to put her limited staff on.

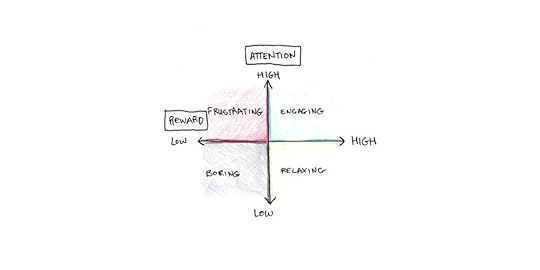

It feels effortful to do an activity that demands a lot of attention but doesn’t offer much reward. We may feel bored or amused by an activity that demands little attention, but it won’t feel hard. In contrast, it feels engaging to do an activity that demands a lot of attention and is highly rewarding.

According to the principles outlined above, effective learning can’t happen in the low-attention conditions. Subliminal learning is not a real thing. But we can make learning more fun by increasing the reward dimension. If learning is more consistently rewarding, it will be more engaging rather than dull or frustrating.

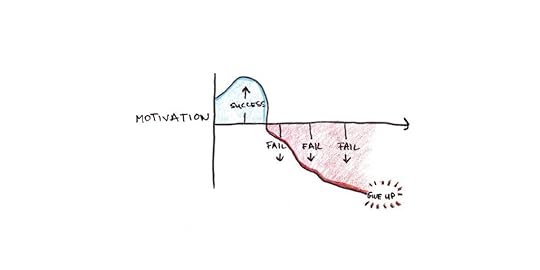

Five Ways to Make Learning More Fun1. Keep your success rate high—aim for 85% correct.The experience of learning is a flow of tiny joys and frustrations. Consider going through flashcards: As you go through them, you probably experience mild bumps of interest whenever you get a card right, and mild dips of frustration whenever you get one wrong.

How much fun you have doing flashcards depends a great deal on the overall path of that flow. If you get too many cards wrong in a row, you will find the task more straining as the motivational centers in your brain look for other distractions. Conversely, if you easily get them all correct, the task may not require much attention—causing you to feel bored and distracted. Your attention has spare capacity that might be deployed elsewhere.

The key to enjoyable studying, then, is to set yourself up so that you’re getting most of the answers correct, but not so many that you start disengaging.

How can you control the difficulty of the activity? One way is to put the tasks on a sliding scale of difficulty. There are a few ways you can do that:

Open book to closed book. The easiest form of practice is to work a problem with a nearly-identical example in front of you. The hardest is to solve a novel problem without access to any reference material. When studying, adjust your reference material to get to the sweet spot of mostly success with occasional failure. Work from simple to complex problems. A complex problem has multiple components that must be done correctly to get the answer right. So, one way to increase your success rate is to split complex problems into simpler parts. Alternatively, if the simple parts are too easy, you can tackle more complex problems that command your full attention.Change the standard you set for yourself. For problems with degrees of success, rather than simple right or wrong answers, you can adjust the difficulty by changing the standard you set.Adjusting the timing. Performing under time pressure can increase the difficulty. Similarly, relaxing time pressure can make a task easier.Our ability to completely change the motivational flow of rewards within our studying is often limited. Thus, it’s unlikely that we’ll be able to take full advantage of video game designers’ tools to make studying as compelling as learning to play a new game. But, we can dial down the frustration in subtle ways to shift a draining task into an interesting one.

2. Reward yourself frequently.Extrinsic rewards have a complicated history in psychology. Research has shown that explicit rewards can sometimes crowd out intrinsic motivation—if you pay someone to do a task, they may enjoy it less or stop doing it altogether when they stop being paid to do it, even if it is a task they might gladly do without being paid.

But, it would be a mistake to infer from this that we ought never to use extrinsic rewards. Some tasks will never invite much intrinsic interest, and rewards can be a powerful lever to make these tasks engaging, if not interesting.

A simple reward mechanism might be giving yourself a candy every time you finish a problem from your homework set. Another might be giving yourself “points” that you put on a tally whenever you succeed with a flashcard or read a section of your textbook.

Because extrinsic rewards can crowd out intrinsic motivation, avoid using them when the aim is to build motivation to perform an activity without rewards. But, if the studying activity itself is merely a necessary stepping stone to something genuinely more rewarding, liberally applying rewards can make the activity more enjoyable.

3. Eliminate temptations and distractions.The opportunity cost theory of effort has an important implication: how much effort we perceive a a task requires depends on the implicit alternatives we have available to us. The strain of studying isn’t merely a property of that task; it’s also influenced by every other possible thing we could do in that moment with our limited attention.

Unfortunately, our attention environment has become saturated with low-demand, variable reward mechanisms. Social media provides a low-effort ping of enjoyment when we occasionally find something funny or amusing. Our phones offer a constant possibility for distraction.

Clearing our our attention environments is a good first step to making studying more enjoyable. Staying on task is easier when you don’t have your phone, computer, friends or television nearby. If you make studying this way a habit, focusing becomes easier since the distractions themselves are not available.

4. Smooth unnecessary friction.Looking through the motivational lens again, we can see that the environment creates many micro-rewards and punishments that are not directly related to the task.

Consider getting set up to study. Maybe you need to find your book. And your desk is messy, so you need to clean it. And the chair isn’t comfortable, so you need to find a new one. And the fan is making an annoying sound in the other room … and so on.

Frictions are the little snags that make a task more effortful to perform. Reducing these barriers to get in the flow can make studying more fun. Since they’re external to the attention demands of learning itself, they’re also something you can improve without sacrificing effectiveness.

5. Make studying more meaningful.Thus far, every suggestion I’ve made involves a task’s superficial rewards and punishments: Success rate, extrinsic rewards, external temptations and frictions. Getting these under control is essential since they’re the easiest to adjust directly.

But what we really enjoy in an activity isn’t just the shallow blips of pleasure and pain we feel while doing it. Instead, it’s the meaning that we give the activity and the meanings we experience while performing it.

Much of studying and learning is boring because it doesn’t feel meaningful. We can’t see the point of what we’re trying to learn. There’s no tangible connection to anything we want to do, achieve, understand or perform in our lives. As a result, there’s only a chore, drained of color, that has to be done.

Increasing meaning isn’t always easy for a few reasons:

The importance of a piece of knowledge or method depends on its relation to other knowledge. Thus, we tend to find subjects more interesting as we learn more about them, as new information is built in a richer context. But this creates a Catch-22 in that we need to expend effort learning about something before we can appreciate learning it.Cognitive load may make meaningless drills necessary. Sometimes, the projects we find meaningful are too difficult to succeed at. We want to make the next Google, but the only program we can write is “Hello World.” We want to paint like Da Vinci, but can’t get beyond stick figures. Building up from fundamentals is often necessary, even if it isn’t always fun—thus, superficial tricks for boosting motivation may be an important tool for this phase of learning.The meaningful context is far away. We’re learning French, but our trip to France isn’t for months. We’re learning statistics, but our career as a data scientist is years off. In these cases, there’s a genuine motivation to learn, but distance from the desired outcome makes it impotent to drive the interest in the task itself. Researchers find that temporal delay is a central factor in procrastination.But even if we can’t always make studying deeply meaningful, we can make efforts to increase the meaning we get from it:

Read more on the background of the skills and knowledge you’re trying to learn. Getting more context can make what you’re learning make more sense—and be more engaging.Alternate between meaningful activities and the drills that support them. Doing real programming projects, having real conversations in another language, or doing real chemistry experiments—even badly—can provide a motivational backdrop for the necessary building blocks of learning.Find friends and forums for people interested in the skill. Social bonds can make an otherwise abstract task into something fascinating. Community can make learning compelling._ _ _

What strategies do you use for making learning fun? Share your thoughts in the comments!

The post 5 Ways to Make Studying Fun (Without Sacrificing Effectiveness) appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 26, 2023

My 10 Most Popular Essays of 2023

This year was a busy one for me! I finished writing my second book, Get Better at Anything, which will be published in May. My wife and I also welcomed our second child, Julia. Oh, and I published 51 new essays!

Below are some of the most popular essays I published last year, in case you missed any!

10 Ways You Can Use ChatGPT to Learn Better – A compilation of some reader recommendations for how they use ChatGPT to study better.The Key to Sustainable Productivity – In order to become more productive, you have to worry less about feeling productive and more about creating systems that allow you to get more done.7 Expert Opinions I Agree With (That Most People Don’t) – Following my essay, The Mind is a Computer, I cover seven other popular-among-experts-but-widely-disbelieved opinions I agree with!Ten Great Books on How to Learn Better – My pick for the best ten books on learning how to learn better!The Intermediate Plateau: What Causes It? How Can We Move Beyond It? – Why do we stop improving? I discuss the research behind why skills stagnate and how to move past it.How My Views on Learning Have Changed Over Time – I’ve been writing about learning for over half my life—this essay charts some of my earliest musings to my more research-informed current stance, trying to share some of the key turning points in my thinking.Self-Efficacy: The Key to Understanding What Motivates You – What is self-efficacy and the three most important takeaways to succeed with challenging goalsLearning, Fast and Slow: Do Intensive Learning Projects Work Better Than Slow Ones? – Combining the two approaches: Why intensive projects should be followed by more leisurely maintenance.The Simple Rule for Achieving Ambitious Goals – The trick for most ambitious pursuits, I’m afraid, is simply doing the obvious thing much, much more than most other people are willing to do—and accepting that it may hurt at times.Are We Losing the Ability to Read Books? – A Gallup poll shows we’re reading fewer books each year. Is this a trend to be worried about?See you next year!

The post My 10 Most Popular Essays of 2023 appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 19, 2023

The 10 Best Books I Read in 2023

The past year was good for my reading. I finished around 40-50 books, and there were plenty more that I started but did not finish. (Not finishing books is a good thing!)

Below are some of my favorites I read this year:

1. Why Knowledge Matters by E.D. Hirsch

I previously reviewed Hirsch’s controversial 1988 bestseller, Cultural Literacy. In this 2016 book, Hirsch presents a sweeping curriculum change in French schools as evidence that misguided educational theories are undermining our children’s learning.

Hirsch argues that schools have been seduced by three intuitively appealing but ultimately unsound ideas:

A focus on skills over knowledge. Schools spend more time on reading comprehension “skills” such as “finding the main idea” or “close reading” of texts. But the science suggests these skills don’t really exist beyond what can be taught with a few hours of practice. Being a good reader relies on having a lot of background knowledge, which is deemphasized in skills-based curricula.A focus on the individual over the community. The skill-based focus arises because there is no definitive curriculum or canon for language arts. We’ve abandoned the idea that education ought to teach students a core set of commonly held knowledge, to the detriment of disadvantaged students, Hirsch contends.A focus on natural development over education. The idea that education ought to be “natural” has roots as far back as Rousseau. But Hirsch argues it is a mistake—that our nature is cultural, and so a failure to teach a shared culture has harmed students who don’t have access to that culture in their home environment.Hirsch’s remedy is “domain immersion,” or, to put it another way, teaching knowledge about the world. What knowledge? Hirsch is open here, but he argues that all students ought to be taught whatever knowledge is expected to be known by members of educated society.

2. Psych by Paul Bloom

You don’t need to learn the history of physics to understand physics. While learning more about Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect or Maxwell’s studies of electromagnetism can be edifying, you don’t need to know about them to learn the physics these experiments proved. The underlying theory is all that’s required to understand physics.

Psychology isn’t like this. There’s no deep undercurrent of theory that ties everything together. Instead, the picture of psychology as a discipline is like a pointillist painting, where you can squint to see the totality only through reference to thousands of tiny dots.

Despite having read a few bookshelves worth of academic psychology texts, I enjoyed Yale professor Paul Bloom’s survey of the field. Because understanding psychology cannot be divorced from understanding its history, I enjoyed Bloom’s birds-eye view of the field from the past to the present day.

3. How We Reason by Philip Johnson-Laird

We reason by creating mental models of the world. That may not sound surprising, but it has plenty of interesting implications for understanding how we think.

I had read Johnson-Laird’s original work, Mental Models, last year. It was nice to see an in-depth follow-up on how the theory has developed in the subsequent two decades.

In a future post, I’m going to have a full summary of Johnson-Laird’s book, and what the theory implies.

4. Creativity in Science by Dean Simonton

Creativity is a tricky subject to study. Experimentalists tend to focus on relatively mundane acts of creativity, such as divergent thinking or alternative uses for everyday objects. But this approach is far removed from the great insights of artists, scientists and inventors we typically laud as creative. Theoreticians, in contrast, spend time creating computer simulations of creative thought—often reducing creativity to mechanical problem-solving.

Psychologist Dean Simonton’s work in this field is unusual due to his largely historical focus on creativity. Instead of gathering data from experiments or simulations, he has studied data sets drawn from the works and biographies of creative individuals.

This book surveys theories of creativity, contrasting four competing explanations: expertise, genius, society, and chance, in offering a model for how creativity works. Simonton’s work provides a nice hybrid between the purely anecdotal work of biographers and the data-driven work of experimental scientists.

5. Cognitive Behavior Therapy by Judith Beck

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is considered the gold standard for psychological therapy. I recently reviewed Beck’s book, which is written as a practical guide for therapists implementing CBT.

While CBT is undoubtedly effective, it’s unclear exactly what the active ingredient is. The classic theory focuses on the cognitive (or “C”) part, namely that depressed/anxious people suffer from distorted beliefs, and these cognitive failures tend to form self-sustaining patterns.

However, some critics argue that these flawed beliefs may be caused by overactive emotional circuitry that operates outside of consciousness. Pure exposure therapy, for instance, tends to do roughly as well as exposure-plus-cognitive therapy for anxiety disorders. If this is true, then it may be the “B” or behavior change component that is more directly responsible for patient results.

6. How Languages are Learned by Patsy Lightbown and Nina Spada

Reading summaries of domain-specific research is part of my goal to deepen my understanding of the science of learning. While plenty of books offer theories on learning, in general, it helps to gird those takeaways with more detailed work from different fields.

To that end, I read a few different books from the field of second language acquisition (SLA) over the summer, and even wrote a review of How Languages are Learned.

Language learning occupies an unusual place in learning theory. People learn their native languages with few failures and little instruction. Yet, most people struggle to learn foreign languages in school (and many immigrant adults fail to learn the language of their adoptive country). General-purpose learning theories, like cognitive load theory, draw a sharp distinction between skills we innately acquire and those that require schooling. So where do second languages fit into that scheme?

On the one hand, SLA research is fascinating and contains many unexpected findings. On the other hand, SLA seems even less amenable to a clear scientific consensus about what works than mathematics or reading, which are themselves beset by eternal controversies. Still, as someone who has spent years learning languages, it was fascinating to dive deeper into how it works!

7. The Science of Learning Physics by José Mestre and Jennifer Docktor

Along with languages, physics is another subject where many students conspicuously fail. Teaching students to think like physicists is a fiendishly difficult goal. Even students who ace exams often revert to folk theories when presented with real-life problems.

Mestre and Docktor tackle this challenge by reviewing the large body of literature on learning physics. I plan on writing a full review of their book, which I found to be a helpful summary.

8. The Republic by Plato

My interests are mainly contemporary, so I haven’t spent a lot of time reading the classics. I’d usually rather read a psychology textbook from the 21st century than try to parse out the (probably wrong) theories of philosophers who didn’t have access to experimental science.

But recently, I’ve been reconsidering this viewpoint. Objectively speaking, the classics aren’t likely to be the best source on any particular topic, but their longevity has embedded them into the background culture of all subsequent discussions.

To my surprise, I really enjoyed The Republic. It is both well-written and weird, which puts it above many other famous philosophical books that are too obscure to be easily read.

9. Social Learning Theory by Albert Bandura

Social Learning Theory is a difficult book to summarize, but it has profoundly impacted my thinking. Self-efficacy, which I’ve covered in-depth here, is just one of the big ideas.

Another big idea is the importance of learning from others. Behaviorists tended to view all actions as resulting from the reward-punishment contingencies associated with taking that action. Bandura helped shape the now-prevailing view in which reward contingencies shape motivation, but not learning beyond deciding what to pay attention to. In this view, motivation shapes which activites we choose to do, but knowledge—mostly gained from other people—shapes what our effective choices are.

10. Beginning to Read by Marilyn Jager Adams

Phonics is a hot topic these days, with prominent coverage in the New York Times and elsewhere. The push to follow the “science of reading” has attracted attention beyond the usual interest in niche educational topics.

There is an accumulation of evidence that systematic phonics instruction (where kids are taught and drilled on the sound-spelling correspondences in print) is superior to whole-language or “balanced” methods. This evidence has often been ignored, but now there is a stronger push towards phonics.

Given the topic’s newsworthiness, you’d expect the “science of reading” to be relatively new. But this controversy has been settled for decades. Jeanne Chall’s influential summary Learning to Read: The Great Debate was published in 1967! Marilyn Jager Adams’s extensive review of the literature concluded essentially the same thing in 1994.

In some ways, reading about the debate has made me more pessimistic about science-driven solutions in many areas of life. If experts can collect clear evidence that a particular approach is more effective, but that evidence is essentially ignored in practice for decades, it makes me less hopeful about other social reforms where the data points one way, but intuitions point in the other.

The post The 10 Best Books I Read in 2023 appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 12, 2023

6 Strategies for Learning New Things (When You Have Kids)

Learning things takes time and energy—two things that are in short supply when you have kids to take care of after working all day.

The biggest shift in how I approach learning things has come from having kids. Previously, I had ample free time to study whatever I was interested in—the primary constraint was whether I was interested enough to invest the time.

Now, I have two children. They’re wonderful, but as any other parent of small kids can readily attest, your work no longer ends when you’re done with your job for the day. Combine this with frequently interrupted sleep, and the result is that you have far less time and energy for learning hard things than before.

Today, I’d like to discuss some of the strategies I’ve found most helpful for continuing to learn a lot, even as a busy parent. Even if you don’t have kids, you might find some of these strategies useful for fitting learning into your busy life!

1. Make use of your fractured time.

I’m a big advocate for deep work. These focused sessions of productivity, without distraction or interruption, allow you to perform difficult cognitive work.

However, long stretches where you’re guaranteed not to be interrupted are unusual when you have small children. A nap might last two hours—or fifteen minutes. Free time is haphazard and unpredictable. This is hardly a recipe for getting a lot of deep work done.

Some learning tasks do require long stretches of focus. But others are more easily fractionated. Those slivers of time can really add up if you know how to take advantage of them.

For instance, shortly after my son was born, I started learning my wife’s native language, Macedonian. To help, I made a few thousand flashcards to help memorize common vocabulary. While I couldn’t guarantee long stretches to practice, keeping flashcards on my phone allowed me to learn a lot in the random slices I did encounter.

2. Make projects ready to start—and ready to stop.

Short chunks of time can make learning difficult, but another difficulty is unpredictability. You might feel reluctant to start reading a book, watching a class or working on a hands-on project if you’re not sure if you have five minutes or two hours.

A factor that has helped me resolve this problem has been making projects ready to start. The fewer barriers you have before starting work, the easier it is to rack up learning time.

This strategy helped me a lot with learning to paint. It has been a hobby I’ve enjoyed since before having kids, but I usually worked in longer sessions. The effort of getting everything set up, only to potentially have to put it all away immediately after, made it unrewarding, and I stopped painting. The fix was to have a dedicated space where I could start or stop with little effort.

Even if you don’t have extra space for your projects, you can make them more ready to start. Supplies you need can be put into a box, ready to use, so that you can take them out and get to work. Lectures you’re watching can be left open in a tab on your computer, rather than need to be navigated back to and re-loaded from the class website. Digital projects can be kept open on a second virtual desktop.

When large chunks of time aren’t guaranteed, the best way to ensure more time is spent actually doing something is to make the cost of getting started as low as possible.

3. Find overlap with your other goals.

Another strategy I’ve found helpful is looking for opportunities to learn things within the scope of other goals I have.

For instance, if I’m interested in learning something, I might try to see how I can make it relevant for work—perhaps relating it to an essay topic. Learning a physical activity combines learning with exercise, and finding a project you can do with your friends or partner lets you spend more time socializing.

The idea here is that a learning project that serves two different functions will be easier to fit into your schedule than trying to accomplish two goals separately. Today, I start by seeking out projects with this kind of overlap since I know I can devote more time to them.

4. Learn with your kids.

Depending on how old your kids are, finding a project you can do with them can be a great way to both learn and spend time with them.

Sports, art, languages, or even just learning facts about sharks or dinosaurs are all things you can try to find overlap with what your kids want and need to learn. Spending time learning together is also a good way to show your kids that learning doesn’t need to stop when you’re finished with school. The best way to instill a mindset of lifelong learning is to demonstrate that behavior yourself.

5. Don’t wait for conditions to be perfect.

One of my favorite stories from Scottish polymath (and mother of five) Mary Somerville was when an acquaintance told her she ought to study botany. Taking up the suggestion, she decided to spend an hour a day learning about it while nursing her child!

While it’s undoubtedly true that learning works best when you can give yourself a quiet, undistracted space and long stretches of time to focus, sometimes those expectations aren’t realistic.

When my son was born, I remember waking up every 2-3 hours to help my wife with feeding and changing. We tried to keep the room dark, but I might be awake for 20-30 minutes while he fed. I used that time to listen to Herbert Dreyfus’s class recordings on Heidegger.

Similarly, my wife began doing Pimsleur’s 30-minute daily French lessons during our son’s morning stroller nap.

I don’t recommend this kind of multitasking for any learning activity where the cognitive load is high. Still, those slow moments can often be good for listening to an audiobook or watching an instructional video.

6. Let your kids teach you.

Perhaps the most important thing you learn when becoming a parent is about your kids themselves.

The rate of learning among kids is incredible. Children acquire dozens of new words per day. They learn to sit up, crawl, stand, walk, run and jump. Incessant whys may frustrate at times, but they’re also how kids learn the innumerable things we take for granted as adults.

The best way to keep learning when you have kids, therefore, is to pay attention to the learning your kids are already doing. From simple things you learned so long ago as to take for granted, all the way to helping with homework lessons you barely remember having learned yourself, raising kids is a continuous learning experience.

Learning has always been a central part of my life. Having kids enriches far more than it detracts from a life spent learning new things.

The post 6 Strategies for Learning New Things (When You Have Kids) appeared first on Scott H Young.

December 5, 2023

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: How to Change Your Mind

Psychoanalysis, pioneered by Sigmund Freud, dominates popular impressions of therapy. Patients lying down on long couches while an analyst dissects their dreams for evidence of repressed childhood trauma make for great television, but does it actually work?

In the late 1950s, Aaron Beck, a practicing psychoanalyst, decided to test a key concept of Freudian theory. Psychoanalysts explained depression as a masochistic drive—hostility turned inward toward the self. If that were so, Beck would expect those themes to show up in patients’ dreams.

However, when he scrutinized these dreams, he didn’t find masochistic imagery. In fact, his patients had fewer hostile images. Instead, he found themes of loss and rejection.

This failure of Freudian theory triggered Beck to question his entire discipline’s assumptions. If the theory’s basic tenets couldn’t be demonstrated in experiments, how useful was psychoanalysis?

Cognitive therapy was born out of this failure. In the decades since Beck’s pioneering work, this mode of therapy has proven one of the most effective practices for treating depression, anxiety and many other psychological afflictions. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) often outperforms pharmaceutical drugs alone, and it has become the gold standard for psychotherapy.

What is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy?The basic premise of CBT is that distorted thinking causes psychological distress and dysfunctional behaviors.

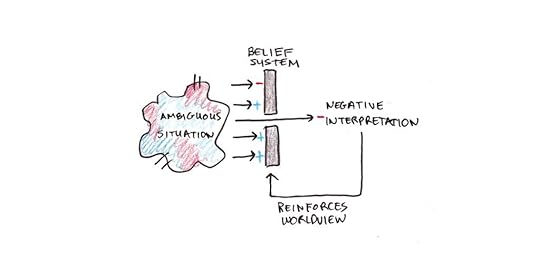

In this model, our beliefs cause us to interpret ambiguous situations in particular ways. These interpretations give rise to automatic thoughts, verbalizations and images that rise to the level of consciousness. Those thoughts, in turn, produce emotional reactions and behaviors.

For example, imagine a depressed person who has a belief that she is incompetent. When she receives a negative performance review at work, it triggers the automatic thought, “I’m such a failure. I can’t do anything right.” The thought then causes her to feel more depressed, further sapping her motivation to work.

Beliefs, thoughts, emotions and actions can all be mutually reinforcing.

Even if the feedback is a mix of good and bad, the depressive person interprets it in a negative light, triggering automatic thoughts of failure that further depress her mood and make it harder for her to work. This further entrenches the original belief, making similar interpretations more likely in the future.

CBT encourages people to notice and question their automatic thoughts. Then, they use reasoning and experimentation to test their beliefs and adopt more realistic ones. This process leads to healthier thinking, feeling and behavior.

Recognizing Disordered ThinkingAutomatic thoughts arise spontaneously, and we have no control over their content. The aim of CBT is not to deny these thoughts; it is to notice them and subject them to scrutiny.

In a leading practitioner’s guide to CBT, Judith Beck (Aaron Beck’s daughter and disciple) lists a number of disordered thinking patterns people who suffer from psychological distress frequently engage in:

All-or-nothing thinking, e.g., “I’m either a winner or a loser.”Catastrophizing, e.g., “If my partner leaves me, I won’t be able to live.”Ignoring evidence for positive interpretations, e.g., “I only passed the test because I got lucky.”Emotional reasoning, e.g., “I feel like a failure, so I must be one.”Labeling, e.g., “I’m a loser.”Magnification/minimization, e.g., “A mixed review means I’m incompetent. Positive reviews don’t mean anything.”Mental filter, e.g., “Because one person at the party didn’t like me, I must be a loser.” (Even if other people did like you.)Mind-reading, e.g., “She thinks I’m an idiot.”Overgeneralization, e.g., “I messed up the recipe. I can’t do anything right.”Personalization, e.g., “Susan canceled our plans because she hates me.” (Ignoring that she might have had another reason.)Imperative thinking, e.g., “I should never make mistakes.”Tunnel vision, e.g., “He’s such an idiot. He can’t do anything right.”One of the central tenets of CBT is not to flatly deny these statements. Indeed, they’re often partially true, and it’s that grain of truth that allows them to take deep root in our minds.

Instead, the therapist encourages patients to begin to notice these automatic thoughts. Then, through a process of Socratic questioning, the patient assesses their validity. Patients are asked to give reasons why a belief might be true, and also offer reasons it might not be.

A friend not replying to a text message might trigger the thought, “She doesn’t like me. Nobody likes me.” But considering other possibilities, “Maybe she is busy?” or remembering that she helped you move last year and invited you to a party recently, can help you to question the validity of that belief.

Action Plans: The “B” in CBTWhile cognitive therapy was initially formulated to focus on disordered thinking, it has since merged with behavior therapy, which focuses on the dysfunctional actions people take.

Consider anxiety. A socially anxious person starts to feel anxious when asked to present at work. All month, he sweats over the proposed presentation, finally asking his boss to find someone else to do it.

Avoiding his anxiety, however, has two major consequences:

The relief he feels in not having to do the presentation reinforces his behavior. Like a rat rewarded for pressing a lever, the motivational part of his brain is encouraged to find ways to avoid presenting in the future.By not presenting, he never gets to see if his feelings about presenting were accurate. He may have believed he would have been humiliated, but he’ll never get disconfirming evidence that such an outcome was unlikely.Action plans and behavioral experiments designed to test the validity of beliefs are central to CBT. These are especially important for depressed patients, whose illness makes even doing simple chores or self-care incredibly difficult. By taking small actions, you pry open a gap between the self-sustaining feedback loop depressive thoughts and inaction generate.

Does CBT Work if You Don’t Have Depression or Anxiety?One thing that struck me while reading the research on CBT was how much of it seems relevant to healthy psychological functioning, in general, and not just extreme cases of anxiety or depression.

If you squint at it, a lot of the advice in CBT reads like something straight out of a self-help book: take action, even if you don’t feel like it; visualize your intentions; set goals; exercise; and build habits to strengthen your motivation. That might be because CBT is simply common sense (if so, then it’s surprising it’s not more widely adopted). But I also suspect that CBT-informed theories and language have leaked out into the broader culture. Anyone reading therapy-adjacent popular books will end up absorbing some of it.

Reading the categories of disordered thinking, I was struck by how often I could think of examples in my own thoughts: Reflexively blaming a lack of reply from a friend on a broken relationship (rather than busyness) or emphasizing the few critical emails I get over the overwhelming majority of positive ones. I don’t think of myself as depressed or anxious, but I can see the parallels between my thinking at times and those of Beck’s patients.

What’s The Active Ingredient in CBT? The C or the B?As mentioned above, CBT, as a whole, is one of the most effective forms of therapy. It is the gold standard for a reason.

But CBT isn’t a specific technique. Instead, it’s a framework for thinking about psychological problems that incorporates many different methods. Exposure, mindfulness, hypothesis testing, self-acceptance, problem-solving, goal-setting and other ideas all fall into the CBT umbrella.

Thus, which elements of CBT underpin its effectiveness is still an open question. One debate concerns whether the active ingredient in CBT is the work of belief change—the noticing of automatic thoughts and subjecting them to a kind of rational analysis, or if it is direct behavioral change that makes CBT so effective.

Research on exposure therapy for phobias, PTSD, and anxiety, for instance, has found that exposure alone performs roughly as well as exposure plus cognitive therapy. Talking about why you shouldn’t be afraid may not be as important as simply exposing yourself to your fears and letting them subside.

Similarly, while depressive patients get stuck in disordered patterns of thinking, they also get stuck in patterns of dysfunctional behavior. Staying in bed all day, not exercising and failing to keep up with basic life tasks can make depression worse. Perhaps the value of CBT lies more in its ability to push people to take action, even if they still feel lousy.

Can You Self-Administer CBT?Another question that percolated in my mind while reading about CBT was whether it is relevant to self-improvement. Nearly all of the research conducted has taken place in the context of formal therapy. While I did see some research involving informal or self-conducted CBT, it’s too scanty to deserve the same evidence-based label that therapist-conducted CBT deserves.

It’s a worthwhile question to ask because there’s a particular challenge in questioning your own beliefs. Socratic dialog with a therapist can help you uncover specific, maladaptive thought patterns and beliefs. In contrast, there is something almost paradoxical about questioning sincerely held beliefs; if you already knew a belief was false, you wouldn’t hold it in the first place.

Behavior change may be a more valuable locus of change for self-directed improvement. It escapes the rational belief paradox above, and behavioral experiments can expose you to new evidence that undermines flawed beliefs.

Still, given the cost and difficulty of obtaining mental health support and the fact that many people’s difficulties do not rise to the level of a clinical disorder, I think understanding the framework CBT presents can help us live happier and more productive lives.

_ _ _

Further Reading:

Cognitive Behavior Therapy by Judith BeckExposure Therapy for Anxiety by Jonathan Abramowitz, Brett Deacon and Stephen WhitesideA comprehensive review of the efficacy of CBT across various disorders.Comparing traditional CBT to “new wave” treatments (including mindfulness).A critique of the importance of belief change (versus behavior change). And a rebuttal.The post Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: How to Change Your Mind appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 28, 2023

How to Learn Anything Easily

A core belief of mine is that (almost) anyone can learn (almost) anything, provided they go about it the right way.

Surprisingly, this is not a widespread belief. Instead, I think most people tacitly believe that some skills or subjects are simply beyond their mental abilities to learn. Maybe they’re “not a math person.” Perhaps they aren’t linguistically talented, musical, artistic or athletic. In short, people have a view of themselves like this:

I’m not here to deny talent or intelligence. Some people will learn things faster and more easily than others.

But I concur with psychologist John Carroll who argued that the difference between students isn’t in their potential to learn particular things, but in how fast they can learn them. In short, some people learn quickly, and some people learn more slowly, but they could all reach the same destination if given the proper support:

Why I Believe in Universal Learnability

Why I Believe in Universal LearnabilityThis belief of mine isn’t just a feel-good tenet of faith. There’s strong evidence that talent impacts learning rate, not eventual attainment:

1. The strong impact of prior knowledge on skills.One of the best predictors of learning achievement is prior knowledge of the subject. This makes sense—if you know more, you have less new material to learn, and you’re better able to understand and integrate new knowledge.

In a famous experiment, researchers gave students a text narrating a baseball game and tested them to see how much of it they could remember. The authors found that reading ability didn’t matter so much, but knowledge of baseball did. Indeed, subjects who were poor readers (a kind of proxy for lower general aptitude) but had a lot of baseball knowledge did better than good readers without it.

Some psychologists have argued that all acquired abilities are really knowledge in disguise. This theory seems more plausible if we expand the definition of knowledge to include procedural skills and implicit beliefs, not just book knowledge.

If it is true that most of our cognitive abilities are grounded in acquired knowledge, the argument for a skill or subject not being learnable is, essentially, an argument that certain kinds of knowledge fundamentally aren’t learnable for some people.

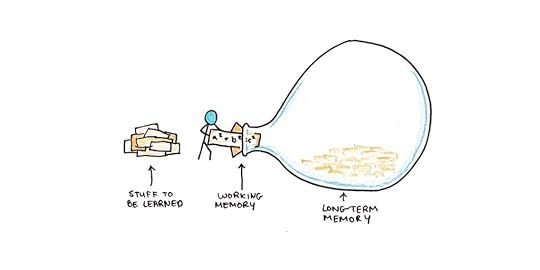

2. Working memory load changes in response to changes in expertise.A well-documented finding is that fluid intelligence, the ability to reason and think flexibly, is closely correlated with working memory capacity. While the exact relationship between the two is still debated, one explanation for the tight link is that greater working memory capacity facilitates intelligence by allowing one to hold more things in mind simultaneously.

Another finding from the research on expertise is that experts can hold more information at one time than novices. This appears to be a specific skill associated with training, rather than a transformation of their general capacity. Theories of how experts are able to do this vary—chunking theories argue that experts manage to compress information into elaborate patterns, and retrieval cue theories argue that experts use long-term memory storage to keep track of the task. Perhaps both are correct.

This means that, in subjects where you have sufficient experience and training, you’re effectively much smarter.

3. “Universal” skills are culturally specific and vary in time.In the Middle Ages, literacy was a rare talent reserved for a priestly caste. If you lived then, there would likely be an assumption that reading was something most people couldn’t learn. Yet today, literacy is near-universal.

Which skills and subjects are considered learnable is primarily a function of their importance in society. Most people learn to read because reading is central to functioning in our society, so we give adequate time and training to budding readers. In contrast, learning to hunt, to name flora and fauna, or to speak multiple languages are skills previous societies regularly mastered that we don’t broadly emphasize today.

Of course, within a given culture, some people will be better readers, hunters or language learners than others. Some will find it easier, and some will find it harder.

My point is that there is much more variance between different cultures than within a single culture when it comes to which abilities are considered “universal.” This is consistent with the idea that nearly anything is potentially learnable by the vast majority of people, if it is given sufficient priority.

Why Do We Feel Some Things Are Impossible to Learn?If almost everything is potentially learnable by nearly anyone, why does it not feel this way?

I suspect there are a few common reasons that make learning harder than it needs to be:

1. We judge relative proficiency, not absolute potential.Again, I believe that talent and prior experience drive our learning rate more than our learning potential. But we mostly measure rate of acquisition, not ultimate attainment, in schools. Because of this, we end up selecting for talent, rather than total potential.

Some of this is probably wise. Nobody can learn everything, so it’s good to figure out which things you have more aptitude for. Resources for learning are also limited, so perhaps, for some esoteric skills, we should reserve those training slots only for the most talented.

But some of this is probably wasteful. I’m a big believer in mastery learning, whose central philosophy is that students who don’t immediately succeed with a skill ought to be spotted early and given extra explanations and practice to catch up. Too often, we punish early learning stumbles rather than help those students succeed.

2. We fail to sufficiently explain and break down complex skills and subjects.Another reason some subjects seem hard to learn is that they’re not fully taught. The knowledge students need to fully understand the problem is skipped over to keep up the pace in teaching the class. The result is that some students can cross the gap and others cannot, making some subjects practically unlearnable for many students, even if they could learn it, in principle.

If you’re struggling with a subject, the safest assumption to make is that you’re missing the knowledge and component skills needed to make it easy. Those skills may take time to build—sometimes too much to keep up with a challenging class and still pass—but they’re buildable if you put in the time.

Learning anything can be made easier if we take the time to break it down and build up from the parts.

3. Our motivational hardwiring encourages us to find our niche.We’re often motivated to pursue relative strengths rather than absolute ability. One study suggests that part of the gap in STEM participation between men and women is not, as is commonly suggested, due to men being better than women at math. Instead, a possible culprit is women being better than men at English—people choose to major in their best fields, which may unwittingly push women away from more lucrative career opportunities in STEM fields.

Sometimes this is adaptive. We focus on our strengths and avoid our weaknesses. But it can also be misleading because we may label ourselves “unartistic” or “numerically challenged” when our abilities are sufficient; they just aren’t quite as good as some of our other skills.

In this way, our belief that we’re only good at certain things may be reinforced when the reality is that we have the potential to learn almost anything—just at different rates.

How to Make Learning Easy (or at Least Easier)All of this suggests a path for making learning easier. When you’re struggling with a subject, focus on background knowledge. Filling in any gaps in that background knowledge will expand your ability to juggle new information, give you stronger “hooks” to latch new knowledge onto and effectively make you smarter in the field of your choice. It may take more time, but it doesn’t have to be frustratingly difficult.

The post How to Learn Anything Easily appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 21, 2023

The 15 People Who Have Most Influenced My Thinking (Part II)

Last week, I started discussing the fifteen thinkers who have most influenced my perspectives on learning, starting with the cognitive scientists who have given me my basic mental models for how learning actually works.

Today, I’d like to focus on a more eclectic mix of thinkers who have informed my understanding outside the narrow confines of cognitive science.

To read the first part, covering influences one through seven, click here.

8. Jean LaveA major tension in my thinking is the relationship between academic skills and real-world competency.

On the one hand, I value learning and education and spend a lot of time trying to learn academic skills and subjects. I believe skills underlie a lot of professional success; thus, our ability to learn well directly contributes to our material well-being.

On the other hand, there are valid critiques of schooling. Bryan Caplan has made the case that much of the value of formal education is signaling—that academic skills and knowledge are unimportant for doing good work. Other writers have argued from survey evidence that many employers seem not to care so much about academic skills in hiring, preferring work experience instead.

In this debate, I’ve found Jean Lave’s anthropological work fascinating. Beginning with a study of West African tailors, she observed that most became competent in their craft with little direct instruction. This encouraged her to adopt the view that learning is social, not cognitive. By this paradigm, learning doesn’t take place primarily in our heads; instead, it’s a cultural activity we participate in.

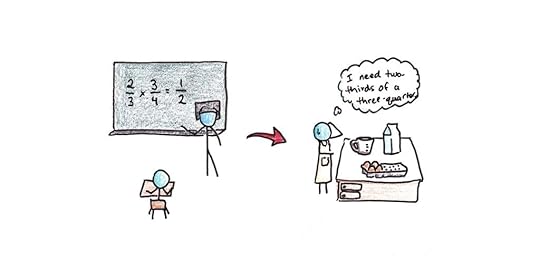

Another provocative book by Lave follows everyday people as they use math in their lives. She found that they rarely followed classroom algorithms but performed competently nonetheless. One of her most interesting findings was that many people struggled to get the right answer to math problems when they were framed as classroom problems—despite correctly solving the same problems “in the field.”

I don’t agree with all of Lave’s thinking. For one, she steadfastly rejects cognitive explanations of learning, which are central to my perspective. Second, she seems to reject the didactic style of instruction, which I believe is more effective.

However, I find Lave’s work intriguing because it covers a topic that is rarely discussed elsewhere—how learned skills apply to real life. There are many experiments on how skill development works, but far fewer careful studies show what kinds of knowledge and skills people use in practice. This results in a plethora of ideas on how to enhance learning, and a paucity of ideas on which skills are most worth learning.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

Situated Learning — This slim volume covers her philosophy of pedagogy, inspired by apprenticeship.Cognition in Practice — Her “real-world math” book covers the fascinating (and controversial) research on how people use math in everyday life.9. Albert BanduraAlbert Bandura has influenced my thinking in two crucial ways.

The first is his concept of self-efficacy, which I’ve explained in detail here. His idea was that motivation isn’t simply the rational calculation of expected benefits, but is influenced by our beliefs that we can (or can’t) execute the required actions. Many people know they need to overcome their fears, apply for a new job, seek out friends or start exercising, but fail to do so if they maintain low self-efficacy for the actions they need to take.

The second is his social learning theory, the idea that most of what we know how to do comes from observing other people, not trial-and-error on our own. Behaviorists centered their explanations of human actions around reinforcement and punishment, which overlooks that humans are a social, cultural species. We may use reinforcement to guide our choices, but we mostly figure out how to do anything by watching other people.

In some ways, any description of Bandura’s ideas does a disservice to the quality of his thinking. That self-confidence matters for motivation, or that it’s easier to learn when you’re shown how to do something, are hardly radical ideas. But his writing also lucidly and intelligently defuses other plausible, competing theories that would reject these commonsense premises.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

Social Learning Theory — Bandura’s excellent book.Self-Efficacy — His paper on the concept has been cited 100,000+ times.10. Barbara OakleyThe first person on this list I can call a personal friend, Barbara Oakley has been an inspiration and influence to me ever since the first session of her wildly popular course, Learning How to Learn.

Oakley has written several excellent books on learning and teaching. Her writing builds upon the work of Sweller and others, but she also draws on a lot of neuroscientific research in informing her advice on the right way to learn and study.

More than anything, Oakley is one of the nicest and most helpful people I’ve met in all my years of writing. She is encouraging to a fault and a big believer in the power of people to change how they learn. She did it herself, earning a PhD in engineering, despite being someone who didn’t initially feel she was good at math.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

Learning How to Learn — Her mega-popular Coursera course, taught alongside eminent neuroscientist Terrence Sejnowski.A Mind for Numbers — An excellent book on the research behind learning math and technical subjects.11. Benny LewisAs I document in my book, Ultralearning, Benny Lewis was the biggest influence on my embarking on aggressive, public, self-directed learning projects.

I met him during a moment of difficulty. I was living in France, and my French was coming along poorly. His “fluent in three months” challenges were an inspiration, and also a source of envy. His approach on deep communicative immersion, overcoming fear and social resistance to speaking a new language, assisted my French. It also became the bedrock for Vat and my later approach in learning languages during our yearlong adventure.

Some people have criticized Benny for the claim imputed by his website, that a person can become fluent in only three months. Fluency is a vague term, and it’s possible to define it in ways where this claim is achievable (e.g., when the aim is fluid speaking/listening for easy conversations) or unachievable (e.g., when the aim is native-like proficiency in all situations). But I think these criticisms miss the point—to me, the title was never a promise but an aspiration, something to strive to reach, even if we don’t always get there.

If you’re interested in learning more, I can’t recommend anything more highly than Benny’s website.

12. Cal NewportCal Newport has been a close friend and mentor for almost as long as I’ve been writing this blog. We’ve also been frequent collaborators on course projects, such as Top Performer and Life of Focus.

Cal started with student-oriented advice books, the best of which is How to Become a Straight-A Student. Cal Newport, himself an accomplished student from elite schools, wanted to dig deep into how some students were able to ace their exams without grinding study routines.

Cal’s answer combines good studying advice with a large dose of good organization and productivity skills. I suspect many students with previously haphazard studying habits (and poor grades) can point to Cal’s book as the inspiration for their transformation into diligent and successful students.

Knowing how to study effectively, and having a system to do so consistently, is more important than raw intelligence for most skills and subjects. While inborn smarts will always give some a leg up, getting organized and studying properly has to be the first step if you’re struggling with school.

For learning, I highly recommend Cal’s student-oriented trilogy:

How to Win at College, How to Become a Straight-A Student and How to Be a High School Superstar.13. Daniel WillinghamDaniel Willingham is one of my go-to sources for evaluating the evidence on studying and learning strategies. He was one of the authors of an impressive monograph that reviewed the evidence behind ten popular learning strategies. His blog delves into educational research and breaks it down for a lay audience. Finally, he’s written some excellent books on learning and education.

A key theme of Willingham’s work is the importance of knowledge to learning. A common, and misguided, critique of schooling is that it only teaches facts—we need to teach students how to think! Except knowledge is what we think with, and smarter thinking requires having more knowledge and experience.

Another maxim from Willingham that has guided my thinking is “memory is the residue of thought.” What we remember and learn is a function of what we were thinking about and paying attention to during learning.

Many educational practices result in worse learning outcomes because they don’t focus students’ attention on the knowledge and processes needed to build skills. For example, students in science classes may spend hours decorating posters about a topic rather than drilling into the concepts underlying that topic.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend:

Why Don’t Students Like School? — Seven principles of good learning, drawn from research.When Can You Trust the Experts? — Questioning the often poor state of educational research, trying to delineate what sorts of science are trustworthy and which aren’t.Improving Students’ Learning — A paper he collaborated on, reviewing ten different learning techniques and the evidence for and against them.His online essays.14. Siegfried EngelmannDirect Instruction is a system of teaching developed by Engelmann and his colleagues in the 1960s. In Project Follow Through, the largest-scale educational experiment ever conducted, Direct Instruction was the most successful program for helping students learn. Since then, countless studies have found Direct Instruction to be successful, particularly with weaker students.

Much of our educational system blames failures to learn on students. They aren’t smart, diligent or attentive enough. Direct Instruction flips this mindset and argues that a failure to learn must always begin with examining the quality of the instruction given. Only if the instruction itself is complete and flawless should we begin to impugn students’ abilities or motivation to learn.

The idea behind Direct Instruction is that skills need to be broken down into their atomic parts, with each part drilled systematically before being built into complex performances. So, learning to read begins systematically with learning to recognize individual letters, learning their sounds, blending their sounds together to create words, and then finally putting them into sentences.

Direct Instruction is often used as a by-word for traditional schooling, and all the negative stereotypes it evokes. However, as I read through Engelmann’s Theory of Instruction, the thing that struck me most was that I don’t recall ever having taking a class taught this way in my entire life!

If you want to read more, I highly recommend Engelmann’s excellent book, Theory of Instruction.

15. Richard FeynmanI’ve read a ton of biographies. While I usually find them interesting, I rarely find myself drawn to emulate the person I’m reading. Famous figures appear heroic from a distance, but they often prove tragic figures when their lives are dissected in detail.

Richard Feynman is different. His attitude and approach to science and learning continue to be a source of inspiration for me today. His unending curiosity, irreverence to authority, and constant hunger to seek a deeper understanding of things have been a guiding star for me most of my adult life.

He is also, perhaps, the source of one of my biggest mistakes as a writer. Shortly after reading his autobiography for the first time, I decided to call a self-explanation technique I had been using “The Feynman Technique.” My memory of the book was hazy, and I remembered him doing something similar in a section of the book.

Something about the usefulness of self-explanations and the association with the illustrious physicist caught on. Countless other explanations of the technique emerged, repeating and strengthening the assertion that Feynman had done precisely this to learn physics.

While I had thought it fairly harmless to name the technique after my intellectual hero, I now see this was a big mistake. My sloppiness as a young writer fabricated a bit of historical trivia that now lives perpetually on the internet. Indeed, it was so successful that my role in naming and associating the technique with Feynman has been completely obscured.

Despite Richard Feynman probably never using the exact technique I named after him, he has always inspired me by his quest to seek a deeper understanding of ideas. In popular media, cleverness is often portrayed as inscrutability.

Feynman showed that true cleverness is simplicity—understanding is the process of making a confusing idea seem painfully obvious, not wrapping it in extra sophistication.

Final ReflectionsPart of living a life devoted to learning is expecting that new ideas may change your mind. After all, if you already know everything, what’s the point in learning new things?

I fully expect the list of who most influences my thinking will be different ten years from now. Not only will new research be published that will overturn some old findings or cast prior concepts in a new light, but I’ll finally make my way to reading thinkers and scholars I’ve missed thus far.

All I can promise is that as I learn more, I’ll continue to share my thinking with you!

The post The 15 People Who Have Most Influenced My Thinking (Part II) appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 14, 2023

The 15 People Who Most Influenced My Thinking About Learning (Part I)

No one develops their worldview in a vacuum. It is a product of your interactions with everyone you read, listen and talk to. I’m certainly no exception.

I’ve benefited greatly from the ideas of other people. But often, those thinkers’ ideas aren’t neatly encapsulated in a single, easy-to-read book. Today, I’d like to share some of the people who have influenced my thinking the most.

To keep the list manageable, I’d like to focus on the people who have most greatly influenced my thoughts on learning. Perhaps I’ll write a later post for more general influences, but today, I’m sharing some of the people who have taught me the most about the subject I spend the majority of my time thinking about!

1. Anders EricssonSide Note: As I was writing this, the resulting essay turned out to be quite long (4000+ words). Thus, I’m splitting it into two parts. This first part covers more of my influences from cognitive science, and the second part covers more personal ones.

Anders Ericsson was a psychologist best known for his work on deliberate practice. This is the theory that world-class performance—in music, athletics, chess and many other domains—is best explained by large quantities of focused practice.

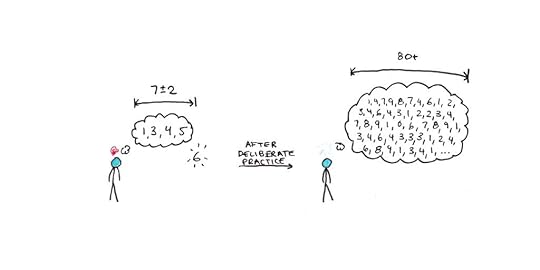

Ericsson’s research into practice began with a longitudinal study, where an individual subject repeatedly practiced a short-term memory task to remember strings of digits after hearing them only once. Famously, most people who do this test can successfully recall between five to nine digits. But, after considerable practice, this highly-trained subject could successfully recall over eighty digits. This breakthrough inspired a lifetime of work exploring how focused training and effort could lift the limits of human performance.

Professionally, Ericsson’s work was central in Cal Newport and my thinking when designing our course, Top Performer. His focus on the value of strenuous practice sessions has been a major factor in my own learning projects.

Personally, I think Ericsson’s work has shaped a fundamental belief of mine that practice and study can ameliorate most differences in skilled performance. While the outside world often prefers people who are effortlessly clever, I’ve come to admire more those whose abilities have emerged after painstaking work.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

Peak – Ericsson’s book, co-authored with journalist Robert Pool, aimed at a non-academic audience.The Role of Deliberate Practice – Ericsson’s highly-cited paper, written with Ralf Krampe and Clemens Tesch-Römer, introducing the concept of deliberate practice.Toward a General Theory of Expertise – Of all Ericsson’s edited volumes, I found this the most interesting in reviewing the state of theories of how expert performance works.2. John SwellerSome people persuade you immediately to their point of view. Others, you fight vehemently until you finally surrender to the weight of their arguments and admit they were right. For me, John Sweller was the latter.

My introduction to his work came from his studies that showed, contrary to my prior assumption, that you don’t necessarily learn more from solving a problem yourself rather than having it be taught to you directly.

Sweller formulated cognitive load theory, which I reviewed in-depth here. The gist of it is that constraints on working memory form the primary bottleneck to learning skills we haven’t evolved to acquire automatically.

A key finding of cognitive load theory is that students with low prior experience with a skill benefit more from observing examples and explanations than from trying to figure out things on their own. This is often true, even if the student might successfully solve the problems they’re provided.

Reading Sweller, and other cognitive load theorists’ work, helped me realize that the majority of knowledge we need to perform complex skills comes from others and that barriers that make it harder to learn from others, such as poor explanations, omitted mental steps, or excessive reliance on figuring things out for yourself, are often the largest initial barrier in learning.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory in Action – Authored by Oliver Lovell, this book best explains Sweller’s work and its importance to instructors and teachers.Why Minimal Guidance Doesn’t Work – This paper sharply critiques the pervasive belief that students benefit when left to figure problems out independently rather than being explicitly taught.The Power of Explicit Teaching and Direct Instruction – Authored by Greg Ashman, one of Sweller’s students, this book is an easy-to-read summary of the evidence supporting cognitive load theory. While no one argument on its own provides a knockout of opponents, the weight of evidence across multiple fields is difficult to refute.3. Robert BjorkRobert Bjork is a cognitive psychologist best known for his theory of desirable difficulties.

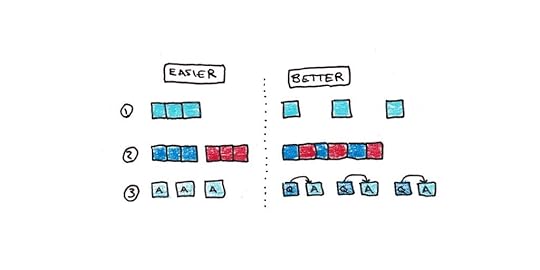

The basic idea behind desirable difficulties is that certain interventions can make training seem less successful because students perform more poorly tests immediately after the intervention. Yet, in the long term, those interventions can create skills and memories that are more durable or widely applicable to other situations than more immediately effective ones.

Some key desirable difficulties include:

Spacing. Spreading studying out over time reduces immediate performance, but enhances long-term memory. Cramming may have a better short-term result, but it is less efficient for learning.Retrieval. Recalling a memory strengthens it more than reviewing does. Variability. Practicing multiple examples, skills or problem-types in the same session slows learning but results in more transfer of that learning to new skills, longer retention, or both.

Another common finding in Bjork’s work is that students fail to appreciate the value of desirable difficulties.

Students, even those who go through the protocol and learn more under the more challenging task constraints, tend to rate the easier practice as better. I’ve argued that this illusion is a critical reason many students engage in endless review sessions rather than practice tests, which require recalling the material.

Clearly, there’s tension between desirable difficulties (which argues retrieval works better than review) and cognitive load theory (which argues examples are better than problem-solving efforts for novices). I might write a future post digging into the debates, but it seems fairly clear that both seeing examples and retrieval practice are important for learning complex skills.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

A New Theory of Disuse – Bjork’s paper, co-authored with Elizabeth Bjork, argues that our memories have both retrieval and storage strengths—implying that memories can be well-learned but temporarily inaccessible when we don’t practice them.Self-Regulated Learning – A good summary of desirable difficulties and our frequent failure to appreciate them in our own training.4. Michelene ChiMichelene Chi’s best-known work is her study of physics experts and novices. When asked to categorize problems by type, Chi found that experts could correctly sort the problems by the fundamental physics principle involved in the solution. In contrast, novices focused on superficial features of the problem, such as whether it involved a ramp or pulley.

A frustration of many teachers is that novices, even after taking multiple classes, often reason about problems in a superficial way. When we teach physics or economics, we don’t want students just to be able to handle textbook problems—we want them to apply these abstract concepts to other domains.

Still, this appears to be the natural trajectory of developing expertise. Abstract concepts, which allow you to navigate superficially different problems that have a common underlying principle, require many different examples and experiences to generalize. With only a few explanations and problem sets, most classes don’t provide an opportunity to reach this level of generalization.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

Categorization and Representation of Physics Problems by Experts and Novices – Her classic paper with Robert Glaser and Paul Feltovich.Eliciting Self-Explanations Improves Understanding – Exploring how student-led explanations of problems can assist in deeper understanding.5. Herbert SimonHerbert Simon was an impressive polymath. He helped launch the field of artificial intelligence, defined a new paradigm for the psychology of complex skills, wrote a classic book on administrative theory, and even won a Nobel prize in economics for his theory of bounded rationality.

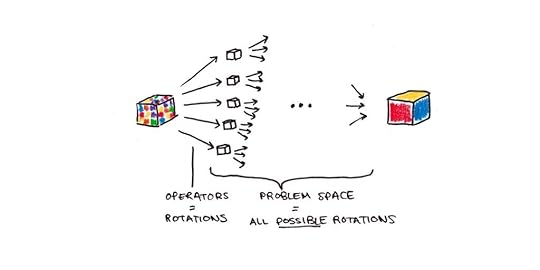

His theory of problem-solving has influenced me the most. According to this theory, the way we solve problems is:

We form some mental representation of the problem. This creates a problem space that has:Our current state.Some way of checking whether we’ve reached a satisfactory solution.Methods for changing from the current state to a new state.We apply those methods in a searching process, looking for a state that satisfies the solution.

The vast majority of problems we face in life have enormous problem spaces. The principal way we deal with this difficulty is by applying strong methods, primarily learned from other people, to cut the size of the problem space down dramatically.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

Human Problem Solving – His landmark book, with Allen Newell. Read my review here.Perception in Chess – A classic paper authored with William Chase, arguing that chess expertise depends on accumulating perceptual “chunks.” They estimate that a chess expert may have tens of thousands of these perceptual units in memory, comparable to the number of words a fluent speaker knows in a language.6. John AndersonMost psychological theories are narrow in scope. A scientist devises an experimental paradigm, discovers an interesting effect, and then a flurry of research follows attempting to explain, refute or delineate its boundary conditions.

John Anderson’s career-spanning work with ACT-R is different. Instead of trying to explain a single psychological quirk, he has attempted to build a computer simulation that would model the entire mental process of skill acquisition—from how people comprehend examples and instructions to what changes in their minds as they gain more practice.

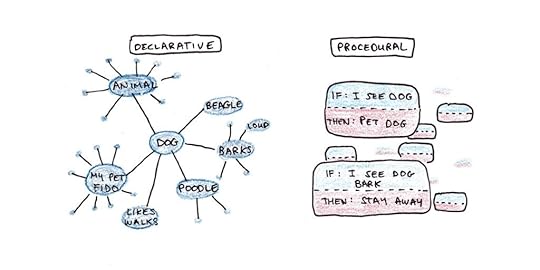

I’ve reviewed Anderson’s theory here, but the basic idea is that cognitive skills consist of two parts: declarative and procedural memory. Declarative memory is for facts and examples, and it works associatively. Procedural memory consists of production rules that trigger when certain conditions are met. Skill learning is a process of, first, acquiring declarative memories that explain and guide the skill, and then converting those to production rules that can trigger automatically.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

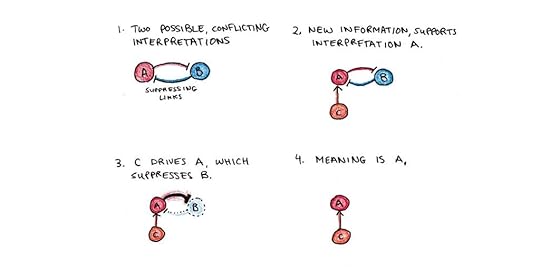

The Transfer of Cognitive Skill – Co-written with Mark Singley, this was an early demonstration of the theory, it also has an excellent overview of the research on skill transfer— how practice in one skill influences another.The Atomic Components of Thought – Co-written Christian Lebiere, this is a full description of the ACT-R theory and what it implies for skill development.How Can the Human Mind Occur in the Physical Universe? – Anderson’s last book explains the motivation for developing a complete cognitive architecture—a complete view of how the mind works—rather than just analyzing a particular psychological phenomenon.7. Walter KintschWalter Kintsch was an expert on the psychology of reading comprehension. He developed the Construction-Integration theory of comprehension, which argued that when we read something, we:

Form multiple, conflicting representations of the text.These conflicting representations inhibit each other so that only the most likely option emerges into consciousness.In addition to a literal understanding of the text, we form a situation model that allows us to make inferences not explicitly mentioned in the text.

I’ve reviewed the full theory here. While Kintsch focused on reading comprehension, his theory of comprehension could also be applied to other intellectual skills and domains of expertise.

Here are some recommendations if you want to read more:

Comprehension – Kintsch’s book outlining the Construction-Integration theory.Learning from texts: Effects of prior knowledge and text coherence – An interesting study showing that, for higher-knowledge students, a less well-organized text resulted in more learning than a better-organized text.Long-Term Working Memory – Co-authored with Anders Ericsson, another major influence of mine, this paper explains their theory of how experts can bypass the well-documented working memory limitation when performing skilled tasks._ _ _

That’s it for today. In the second part, I’ll round out a few more of my academic influences, popular writers, and individuals who have shaped my thinking about learning.

The post The 15 People Who Most Influenced My Thinking About Learning (Part I) appeared first on Scott H Young.

November 7, 2023

Reader Mailbag: ChatGPT-Induced Ignorance, Language Learning, Flashcards and More

Last week, I asked readers of my newsletter to send me questions they had about life and learning. You sent a ton of great questions! I picked some of the most interesting/useful ones to answer today.

Reader questions are in block quotes, my responses are not.

Q: The introduction of the calculator made generations less reliant on mental arithmetic, and continues to do so. Computers and the internet age made researching easy. Since we have apps like Waze, we don’t bother to learn how to navigate to places. And now you have AI on the scene.

I know technologists will make the case that technology can and will be used to make us better, but I can’t help wondering that there is a huge risk to us given how AI especially can make us “soft” as learners. It’s just too easy to make ChatGPT do your “thinking” for you, and for a lot of people that might be good enough. What do you think?

-Kislay

I have two thoughts on this. First, whenever people worry about new technology making us mentally soft, I always think back to Socrates decrying the spread of writing as undermining the ability to memorize. And, you know what—he was right! Ancient Greeks had fantastic systems for memorizing speeches and poetry that we seldom use today.

But the broader point is that as new technology has automated some cognitive functions, it has opened room for different ones. Books may have made memorizing speeches less relevant, but they also greatly expanded the breadth and depth of knowledge a person could access.

As a teenager, I recall reading think pieces about the pernicious effects of Google and Wikipedia on our ability to learn things. But those things are great for learning! I can now learn something about almost any topic nearly instantly. I recently wanted to learn more about the science of burnout for an essay and was immediately given a summary of the latest research from Wikipedia. That’s a major improvement just since my adolescence, never mind generations who had to rely on paper encyclopedias.

So, I tend to be less worried about AI undermining education than others.

My second thought, however, is that sometimes this great boost in readily available knowledge encourages people to suggest the opposite: that because of these technologies, we won’t need to learn things. I do think certain kinds of skills may become obsolete, but not all of them. The calculator eliminated the need for slide rules, but we still need to understand arithmetic to use a calculator. It takes knowledge to learn knowledge, so I’m highly skeptical of claims that LLMs or ChatGPT will reduce the demand for education.

Q: Some people claim that they can increase their reading speed and can read a book in 2 or 3 days. What are your thoughts on that?

-Mark

I’ve covered the research on speed reading here. Spoiler alert: speed reading is just a strategic kind of skimming. It may be helpful for some things, but ridiculous speeds invariably result in comprehension loss.

But I can also say I regularly read books in 2-3 days, and I don’t think you need speed reading for that. Reading lots of books is largely about just sitting down and reading continuously for enough time to get through it. Similarly, you don’t need to be a speed-tv-watcher to binge an entire Netflix series over a weekend … you just need to watch a lot of television.