Scott H. Young's Blog, page 10

March 5, 2024

The Paradox of Productivity

What if being productive doesn’t mean feeling productive?

A paradox of productivity is that the things that feel productive—working incessantly, checking off lots of tasks, feeling strained and drained—are often not what produces important accomplishments; in fact, these things can get in the way.

Recently, two of my friends have written books which argue versions of this thesis. The first is Ali Abdaal’s Feel Good Productivity. Ali’s central idea is that we’re at our most productive when we’re happy. In the moment, grinding ourselves into exhaustion may seem like a necessary trade-off. We might be miserable, but it’s a crucial sacrifice on the altar of our ambitions. Ali argues this is a delusion. Burning ourselves out doesn’t just make us unhappy—it also makes us get less done.

The second book, Slow Productivity, written by my longtime friend and collaborator, Cal Newport, comes out this week. (I was lucky enough to get an advance copy.)

Slow Productivity builds on the ideas Cal developed in Deep Work, Digital Minimalism and A World Without Email. Cal argues that we aren’t good at measuring the productivity of knowledge workers. As a result, we tend use how visibly busy workers are as a proxy for their productivity. This pseudo-productivity makes workers feel harried, but all this busyness doesn’t lead to doing excellent work.

Drawing on dozens of well-researched case studies, Slow Productivity makes the argument for a different understanding of productivity. It is less centered on checking off items on a to-do list, and more focused on doing work that will build a legacy.

Cal proposes three principles to make this work:

Feeling Productive Versus Being Productive

1. Do fewer things.

2. Work at a natural pace.

3. Obsess over quality.

I admit, I was a little nervous to begin reading Slow Productivity. Cal and I have worked together for years, and we rarely have significant divergences in our viewpoints.

However, in my upcoming book, Get Better at Anything, I dedicate an entire chapter to reviewing psychologist Dean Simonton’s work on creativity, which finds a surprisingly tight relationship between creative quantity and quality. On the face of it, the idea that we should do fewer things and obsess over quality seems to contradict the idea that those who have the most hits are the ones who took a lot of shots.

But a careful reading of Slow Productivity indicates there is less contradiction than one might think. Cal’s opening story is of the author John McPhee, spending a leisurely eight months doing in-depth research for a magazine piece, lying on a picnic table as he contemplates how it will all come together.

Yet John McPhee also wrote twenty-nine books and won a Pulitzer Prize! He could just as easily have been an example of Simonton’s maxim that the most successful creatives are typically prolific.

Lazing under a tree contemplating your work feels unproductive. Yet, paradoxically, this loafing is the habit of someone who is incredibly productive—measured by both critical acclaim and volume of work.

While I hesitate to put myself alongside McPhee as an example, I’ve observed this paradox of productivity in my own work. The times I have felt the least “productive” in the ordinary to-do list sense of the word have driven my biggest career leaps.

When I undertook my MIT Challenge, it was an intense project that had no direct connection to my actual work. Several friends and colleagues actively dissuaded me from taking it on since the project seemed to them a complete waste of time. I did it anyway. At the time, it looked like I was taking a sabbatical to work on an eccentric, ambitious, and perhaps pointless project.

In retrospect, it looks like a fantastic bit of self-promotion for someone who writes about efficient learning. But, during the project, relatively few people paid attention to it, and the time it required forced me to cut back to the absolute bone every activity that was paying my bills. The year I worked on the project, I earned far less than the previous year, which had been a relatively “normal” one for my business selling ebooks and courses.

Many efforts that ultimately lead to giant leaps in your creative work seem fantastically unproductive. They require you to scale back your “normal” work drastically. They cause you to lose clients and turn down contracts. For the outside world obsessed with visible busyness, it looks like you’re just wasting time.

But true productivity, measured in terms of one’s lifetime accomplishments, works on a different rhythm than the daily to-do list.

The post The Paradox of Productivity appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 27, 2024

My Simple Habit for Smarter Book Reading

A single habit has improved the quality of my book reading more than anything else: reading rebuttals.

To explain, let me first give some context.

I’ve long enjoyed reading big-idea books in science, business or self-improvement. These books range from mega-bestsellers (The Tipping Point; Guns, Germs and Steel) to the relatively obscure (The Enigma of Reason; How Asia Works).

In most cases, I don’t have deep expertise in the topic I’m reading about. The research literature the authors cite is unfamiliar to me. I don’t know whether the proposed idea is a near-consensus opinion or some quirky theory held by a fringe minority.

As a result, reading big-idea books can lead to a common pattern:

You know nothing about a topic, X, and have few or no strong preconceived ideas.You read an author with a bold proclamation, Y, which they claim is the right way to think about X. They support this claim with fancy citations, graphs, and impressive rejoinders to objections you hadn’t even considered.You leave convinced that Y is the right way to think about X. Someone points out some of the flaws in Y. Maybe you read a different book about all the reasons Y is the wrong way to think about X!Now you feel hoodwinked. That original author, who proposed Y, had tricked you! What seemed obvious no longer does, and you’re unsure what to believe.If you’ve been through this cycle a few times, it’s hard not to become cynical. What’s the point of reading books if you frequently end up getting suckered in by bad ideas? How can you learn new things without getting seduced by misleading arguments?

Why “Critical Thinking” Doesn’t WorkThe classic advice for dealing with this problem is that we need to become better “critical thinkers.” There are many different versions of this advice, but some of them include:

We should insist on high-quality evidence. Randomized controlled trials with preregistered designs! Careful econometric methods to distinguish correlation from causation! Large sample sizes! Except such high-quality evidence often doesn’t exist. Even when it does, aggregating it can be difficult—authors frequently cite an excellent study that supports their conclusion, while ignoring equally good research that does not.We should point out invalid arguments and logical fallacies. Other critical thinking advocates argue that we should read carefully and note reasoning mistakes. Was that an ad hominem attack? Did the author beg the question in the conclusion? This approach sounds smart, but it assumes all arguments are reached through deduction and laid out as a syllogism. However, most reasoning is inductive (and abductive) rather than deductive. At the same time, many fallacies of logical deduction are still good heuristics for other forms of reasoning (is it ad hominem to accept the word of a credentialed scientist specializing in the topic over a random internet weirdo?), this approach is not a cure-all for wrong thinking. We should invest effort to think deeply about ideas and decide for ourselves what to think. In this view, there’s no method at all. Critical thinking is simply being smart about ideas and not letting sloppy ones trick you. Unfortunately, when reading a book, we’ve already set ourselves up to lose—the author has spent years thinking through an argument we’ve never even considered before. They’ve planned their rhetorical moves well in advance, while we must improvise counterarguments while reading.I don’t believe critical thinking is a skill at all. Instead, most of what we refer to as critical thinking is simply knowing more about the topic being discussed. Experts can spot the fallacies in certain arguments because they’ve steeped themselves in the history of ideas and debates in the field for years. Newcomers have not, and therefore cannot.

But therein lies our difficulty: how do you read a book like an expert without actually being one?

Why Reading “Hostile” Book Reviews is the Key to Smarter ReadingGenerating a thoughtful rebuttal to a well-presented idea is hard. It requires a lot of expertise and mental effort, more than most of us are willing or able to expend on a book we bought because it looked interesting.

Instead, the best solution is to seek out the best counterarguments available. These arguments are typically made by competing experts within the same field. What do those experts say is wrong with the book’s idea?

It may sound like reading a rebuttal would simply be an undoing of the original book’s thesis. If you read a book and then then read its rebuttal, wouldn’t you just be left with a confusing mess?

But in practice, it usually doesn’t work this way. Most books you read don’t present a singular thesis; rather, they present an enormous collection of ideas and their implications. When you read rebuttals, they invariably zoom in on a few weak points in the author’s argument.

In fact, reading rebuttals can often bolster your appreciation of the original idea because you come to know which parts are conceded by even its most strident critics. When even your opponents admit that you’re right about something, it’s a strong sign that at least that part of your idea is correct.

More importantly, reading thoughtful rebuttals outsources the expertise and extensive thinking required to find the flaws in big ideas to someone qualified to find them. Invariably, someone who has spent their entire life reading and thinking about a topic will do a better job noticing what’s wrong with an idea than you will.

How to Use This Strategy to Think BetterMy preferred source for this type of rebuttal is scholarly book reviews. These tend to be written by experts in the field, whereas journalistic book reviews are often written by a non-expert (although this isn’t always true; be sure to check the byline). To find these scholarly reviews, simply go to Google Scholar and type “Name of Book” and “review” to find some examples.

If this fails, another strategy is to find the book itself on Google Scholar and click “cited by” to find something that discusses the book rather than simply references it. If many authors have cited that particular book, you can search for reviews or critiques within the articles that have cited the original work.

What about books that don’t have reviews? Or the reviews don’t seem to dig deep into the idea itself? In that case, I try to find the academic terms that refer to the sets of ideas the author discusses. Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel looks at geographic or environmental determinism. Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works looks at industrial policy, land reform, and infant industry protection.

Finding the technical terms that refer to the ideas in the book can help you find critiques of those ideas, even if those rebuttals are not aimed at a particular book. Pretty much any idea you can think of has a name, and once you know its name, you can find people who agree and disagree with it.

ChatGPT and LLMs can be useful here. Asking an LLM, “What are the most frequently cited objections to opinion X?” doesn’t guarantee an accurate summary of the literature. But it can give you a starting point by introducing you to some jargon you can search for later.

Doesn’t This Greatly Increase Your Reading Time?Not really. Most books are a few hundred pages. A book review can be as little as a couple of pages. Even reading a few reviews for a given book shouldn’t add more than 10% to your overall reading time.

Accepting the Imperfection of Most IdeasOne shift that occurs when you regularly engage in this practice is that you realize that there are few arguments without good counterarguments, and few ideas without noticeable flaws. Tyler Cowen’s first law is essentially correct.

But I think accepting that most arguments are imperfect, that even true ideas have persuasive rebuttals, is an essential step to becoming a better thinker. It helps avoid wild swings of fervent belief followed by disillusion and encourages you to see issues from multiple perspectives.

The best habit to improve your reading is to ask after every impassioned argument, “What’s the rebuttal?”

The post My Simple Habit for Smarter Book Reading appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 13, 2024

The 6 Causes of Burnout (and How to Avoid It)

Burnout is miserable. You feel exhausted, but you still need to keep showing up to the job, day after day. Whatever fire you had for your work has now fizzled out—making you wonder whether you should quit and start over.

Why does burnout happen, and how can we avoid it?Christina Maslach is one of the world’s leading experts on burnout. In the 1980s, Maslach and her colleagues developed one of the first psychological assessments for burnout. In the subsequent four decades, she has built a career investigating the causes of burnout.

Burnout is More than Just Being TiredMaslach’s research finds that burnout is more than being tired or overworked. Instead, burnout is a combination of three different factors:

Exhaustion. Extreme fatigue is the first, and most prominent, symptom of burnout. This fatigue is what most people associate with burnout, and it often sets the stage for the other two symptoms.Cynicism. Early studies of burnout looked at healthcare workers. To cope with job stress, burned-out doctors and nurses stopped treating patients like people, which was called “depersonalization” in the literature. As burnout research expanded to other jobs, researchers observed that this same phenomenon of emotional distancing and cynicism was associated with burnout regardless of the field studied.Ineffectiveness. In addition to being tired and cynical, burned-out workers feel like they can’t do anything about it. Feeling helpless, you might feel like you can’t do much but try to endure.Exhaustion alone is bad enough, but adding the other two factors can make burnout a pernicious force. Burned-out healthcare workers have been associated with higher mortality rates, and burned-out police officers report more violent force used against civilians.1

What Causes Burnout?Maslach argues that we’ve adopted an unhealthy perspective regarding burnout in the workplace. Burnout is seen as an individual issue, in which some people simply can’t cope with the stresses and demands of the job.

Maslach illustrates the problem with this approach through the analogy of sending a canary into a coal mine. Colorless, odorless carbon monoxide and other toxic gases can build up deep underground, so miners used to bring canaries, which are particularly sensitive to the effects of these gasses, down into the mines with them. If the canary started to wobble on its perch, workers knew to leave before it was too late.

Treating burnout as a purely individual problem, Maslach argues, is like dealing with dying canaries by trying to find more robust birds who will last longer down in the tunnels—it misses the point entirely. Instead of trying to toughen up the canaries, we ought to be working to fix the elements that make our work environment toxic.

Similarly, Maslach argues against the medicalization of burnout. Some researchers have chosen to treat burnout as a kind of mental illness, like depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. While this may be done with the good intention of getting burned-out workers access to health resources set aside for mental illness, it also perpetuates the idea that the problem is inherent to the workers—rather than the interaction between workers and their environment.

Instead of the individual model, Maslach argues that burnout can be understood as a mismatch between six different elements of the work environment:

1. Workload.The most obvious condition for burnout is working too much. When workplace demands exceed our resources for coping with them, exhaustion sets in. If left unchecked, this can lead to cynicism and ineffectiveness as we are unable to cope with the demands.

It’s not the occasional burst of intense work that causes problems, but sustained overwork without respite. Organizations that operate in perpetual “crisis mode” or post-downsizing roles where one person is expected to do a job that actually requires multiple people can create chronic conditions of overwork that lead to burnout.

2. Control.It’s not just how much work you have that matters for burnout, but your ability to take control of it. Maslach found in her research that people with high workloads, who also had a high degree of autonomy for managing that work, were less likely to be burned out.

Instead, those who have a lot of work to do, and little say in how the work is done, are more susceptible to burnout. Being given little flexibility in performing work, especially when the constraints do not seem well-justified, can make an otherwise bearable workload feel unmanageable.

3. Reward.Too much work for too little pay can exacerbate feelings of burnout. But Maslach argues that rewards go far beyond just getting enough money. (Although that’s important, too!)

Instead, the intrinsic rewards and recognition for a job well done can matter more than the amount written on your paycheck. Showing up to work every day, doing your best, and feeling like nobody cares is a recipe for burnout.

4. Community.Workplaces aren’t just about efficiency. Our relationships with colleagues and bosses can make a huge difference—both positive and negative—about our feelings for the job. Good friends can make a tedious job bearable. In contrast, bullying and hostility can make a “dream job” miserable.

Burned-out people, in turn, are not much fun to be around. They’re more likely to lash out, be mean, unhelpful or emotionally unavailable. This implies, Maslach contends, that burnout can be contagious. Another reason for treating burnout as an issue beyond the individual is that even if not all employees show signs of extreme burnout, those who do may contribute to a toxic community that worsens working conditions for others involved.

5. Fairness.When people don’t feel like the rules and rewards of work are fair, it can exacerbate cynicism and accelerate burnout.

Interestingly, Maslach has found that workers care more that the processes are fair than that the outcomes are perfectly equitable. In one case, a company she worked with tried to fix issues of perceived unfairness by giving people more money. However, this approach didn’t work because workers were upset that the rewards were given arbitrarily.

You can probably feel this yourself in workplaces where getting ahead feels like it’s “all politics” or where favoritism and nepotism seem to rule over transparent and fair procedures.

6. Values.A final mismatch can occur when the values of the person working the job do not correspond to the values expressed in doing the work. A nurse might have gone into healthcare to treat sick patients, but the management mostly cares about increasing revenues. A researcher might have gone into academia with the dream of advancing science, but feels disgusted by constant pressure to churn out grant applications to fund their work.

How to Avoid Burnout

How to Avoid BurnoutIf burnout results from the relationship between work and worker, rather than a purely individual problem, we need to look at both sides of the equation if we want to avoid burnout.

Unfortunately, Maslach notes, this can be difficult. Many organizations insist on treating cases of burnout as problems with those individuals rather than seeing them as warning signs that the workplace is becoming toxic.

That said, there are a few ways we can manage burnout better:

Take time off. Vacations and sabbaticals are the most commonly suggested ways of dealing with burnout. If the main issue is a demanding workload, temporarily slowing down may be necessary to recover your energy. However, while time off may help with exhaustion, it likely isn’t enough to deal with feelings of cynicism or ineffectiveness about the work.Learn new skills. A lack of needed workplace training can exacerbate burnout when you are required to keep up with workplace demands that you lack the skills to meet. Learning skills for doing the work, skills for managing your time and commitments, and social and emotional skills for dealing with stressful situations and people can help you cope better with demanding environments.Realize you’re not alone. Workplaces stigmatize burnout, so workers struggling with it are often reluctant to express their feelings. But this can create a situation where burned-out workers are unaware of how many others at their workplace feel similarly, causing workers to feel alone in their burnout even when it is widespread.Finally, if you don’t feel like you can manage your exhaustion, it may be a good time to quit. If the problem is not just you, but the environment, even the best coping strategies may only go so far. Like the canary in the coal mine, burnout can be a critical signal to get out, not just to toughen up to a toxic environment!

The post The 6 Causes of Burnout (and How to Avoid It) appeared first on Scott H Young.

February 6, 2024

Does Everyone Learn at the Same Rate? An Intriguing Experiment

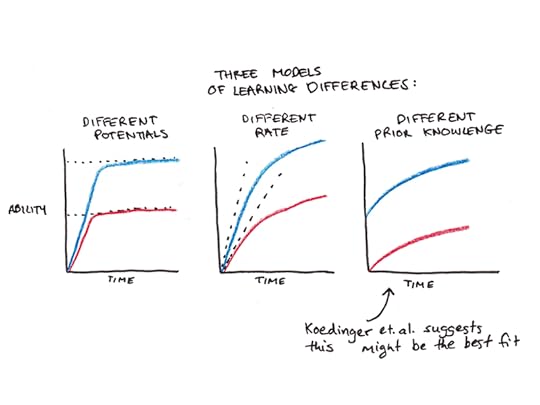

Recently, I wrote a defense of psychologist John Carroll’s claim that what separated stronger and weaker students wasn’t a fundamental difference in learning potential, but a difference in learning rate. Some people learn faster and others more slowly, but provided the right environment, essentially anyone can learn anything.

In arguing that, I primarily wanted to dispute the common belief that talent sets hard limits on the skill and knowledge you can eventually develop. Not everyone could become a doctor, physicist or artist, the reasoning goes, because some people will hit a limit on how much they can learn.

However, in arguing that the primary difference between students was learning rate, I may have also been committing an error!

A recent paper I encountered suggests that the rate of learning among students doesn’t actually differ all that much. Instead, what differs mostly between students is their prior knowledge.1

“An Astonishing Regularity”

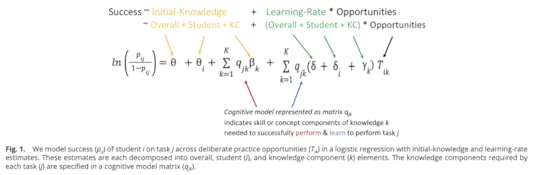

“An Astonishing Regularity”The paper, “An astonishing regularity in student learning rate,” was authored by Kenneth Koedinger and colleagues. They observed over 6000 students engaged in online courses in math, science, and language learning, ranging from elementary school to college.

By delivering the material through online courses, the authors could carefully track which lessons, quizzes and tests the students took.

The authors then broke down what students were learning into knowledge components, and created a model that defined the individual factors responsible for learning each topic.

The model breaks what students learn into prior knowledge inferred from their performance on test items before instruction begins, and a measure of new learning. The actual details of the model are a little technical, so if you’re interested, you can read the paper or see this footnote.2

Immediately, the authors observed that students enter classes with substantial differences in prior knowledge. The average pre-instruction performance was 65%, with more poorly performing students at 55% and better performing students at 75%.

This difference in prior knowledge translated to differing volumes of practice needed to achieve mastery, which the authors defined as an 80% probability of success. Strong students needed roughly 4 opportunities to master a given knowledge component, whereas weaker students required more than 13. A dramatic difference!

However, the rate of learning between strong and weaker students was surprisingly uniform. Both groups improved at the same rate—achieving roughly a 2.5% increase in accuracy per learning opportunity. It was simply that the better students started with more knowledge, so they didn’t have as far to go to reach mastery.

While the authors did find a slight divergence in learning rates, it was dwarfed by the impact of prior knowledge. According to this model, students required an average of seven practice exposures per knowledge element to achieve mastery. When the level of prior knowledge was equalized between “fast” and “slow” learners, the “slow” learners only needed one additional practice opportunity to equal the rate of the “fast” learners.

If All Learners are Equally Fast, Why Do Some Have So Much More Knowledge?This result surprised me, but it wasn’t the first time I have encountered this claim. Graham Nuthall made a similar observation in his extensive research in New Zealand classrooms, finding that students required roughly five opportunities to learn a given piece of knowledge, and the rate did not vary between students—although prior knowledge did.

Still, it raises an obvious question: if learning rates are equal, why do some students enter classes with so much more prior knowledge? Some possibilities:

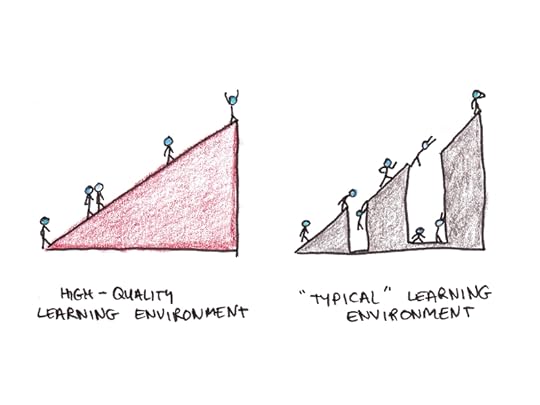

Some students have backgrounds outside of school that expose them to greater knowledge. One of the famous results of early vocabulary learning is that children from affluent backgrounds are exposed to far more words than those from poor and working-class socioeconomic backgrounds. Some students might be more diligent, curious and attentive. The authors note that their learning model fits the data much better when you count learning opportunities, not calendar time elapsed. Thus, if a student gets far more learning opportunities within the same class (by paying attention to lectures, doing the homework, etc.) than a classmate, they will have dramatically different overall learning rates, even if their learning rate per opportunity is the same.Perhaps learning rate is uniform only in high-quality learning environments. A common finding throughout educational research is that lower aptitude students benefit from more guidance, explicit instruction and increased support. It might be the case that learning rates diverge for less learner-friendly environments than the one studied here.

Another possibility is that small differences in learning rates tend to compound over time. Those who learn faster (or were given more favorable early learning environments) might seek out more learning and practice opportunities, resulting in bigger and bigger differences accumulated over time.

In reading research, Keith Stanovich was one of the first to propose this Matthew effect for reading ability. Those with a little bit of extra ability in reading find it easier and more enjoyable to read, get more practice, and further entrench their ability.

Still, a countervailing piece of evidence to this view is the fact that the heritability of academic ability tends to increase as we get older. Teenagers’ genes are more predictive of their intelligence than younger children’s genes are. That kind of pattern doesn’t make sense if we believe large gaps in academic ability are simply due to positive feedback loops—that would suggest those who, through random factors, were above their predicted potential would continue to entrench their advantage, rather than regress to the mean.

Those remaining questions aside, I found Koedinger’s paper fascinating, both for providing a provocative hypothesis regarding learning, and their effort to systematically model the knowledge components involved in learning, offering a finer-grained analysis than many experiments that rely only on a few tests.

The post Does Everyone Learn at the Same Rate? An Intriguing Experiment appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 30, 2024

The Science of Learning Physics

Physics is a notoriously difficult subject. The math is complicated, the principles are subtle and even when students pass the final exam, they still frequently fail simple conceptual questions designed to test whether they really understood anything.

Given this difficulty, it makes sense that we should strive for more effective ways to teach and learn physics. Jennifer Docktor and José Mestre provide an elegant summary of the relevant research on evidence-based instructional practices in their book, The Science of Learning Physics.

Why is Physics So Hard to Learn?While learning the math underpinning physics isn’t easy, Docktor and Mestre argue that conceptual reasoning is what students struggle to master.

We are born into a physical world; thus nature has endowed us with intuitions for dealing with physical objects. Unfortunately, these intuitions don’t align with the deeper laws of physics discovered by scientists.

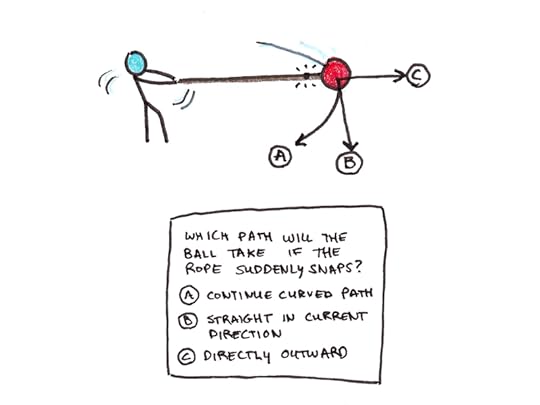

Most people reason like Aristotle—we think objects stop moving when we stop applying force, that the force on a ball thrown directly up changes continuously, or that when two objects collide, the bigger one exerts a greater force on the smaller one. Instead, we’d like them to reason like Newton (and eventually Einstein)—objects in motion stay in motion without an external force, the force on a ball thrown up is constant (it’s just gravity), and every action causes an equal and opposite reaction.

A common assumption is that the ball will continue on a curved path (A) before straightening out. In fact, it will continue in the direction of its current motion if no force is applied to it as in (B).

A common assumption is that the ball will continue on a curved path (A) before straightening out. In fact, it will continue in the direction of its current motion if no force is applied to it as in (B).A semester of college physics isn’t enough to overcome this failure to reason properly about physics. Instead, Docktor and Mestre argue for a knowledge-in-pieces view of building knowledge of physics. In this account, students don’t overcome their misconceptions simply by being taught the correct solution. Instead they acquire an accurate understanding piecemeal, sometimes exhibiting correct reasoning and other times falling back on naive intuitions.

Developing conceptual reasoning is different from merely being able to solve textbook problems, as it’s possible to memorize how to solve a problem without understanding why the process works.

How Do Physicists Think About Physics?Physics classes aim to produce more expert-like reasoning about physical problems. To that end, psychologists have devoted considerable time to studying expert-novice differences in many fields, including physics.

These studies take a snapshot comparing the reasoning patterns exhibited by domain experts (in this case, physicists) and novices (usually people who have taken an undergraduate class or two).

Some of the common findings from this line of research include:

Experts see principles, while novices see surface features. Asked to categorize physics problems, experts organize them based on the fundamental principle involved. Novices, in contrast, focus on surface features, like whether the problem involves a ramp or a pulley.Experts reason forward, while novices reason backward. Experts start from the “givens” of a problem and pick the right formulas to apply to get the intermediate quantities needed to solve a problem. Novices, in contrast, start with the goal and try to find equations to solve for the goal, working backward. This latter approach is more mentally demanding, which is one reason physics problems are so hard for beginners.Experts spend more time studying a problem, while novices rush to calculations right away. While experts generally solve problems faster than novices, proportionally, they spend more time trying to understand the problem before doing any computations. Novices, lacking the ability to categorize the problem by general principles, tend to rush to crunching numbers, hoping it will lead to a solution.One way to understand these differences is that experts have sophisticated schemas, or organizing patterns, that cause them to perceive problems in terms of the principle underlying their solution. Novices, who lack these patterns, tend to “plug-and-chug” numbers into available formulas or use direct analogy to remembered problems of the same type.

Can the Deep Ideas of Physics Be Taught Better?Docktor and Mestre are optimistic that there are better ways of teaching physics than the typical approach, in which a professor lectures to an audience, perhaps occasionally showing an example or derivation, and assigns homework problem sets.

One strategy that the authors believe shows promise is in making explicit the reasoning process that goes into solving a physics problem. Instructors, whose schemas make the next “correct” move in a physics problem obvious (to them), tend to focus on demonstrating the underlying math, rather than why a particular equation needs to be used.

If teachers can instead model the entire problem-solving process—not just the algebraic steps, but the conceptual reasoning that allows them to decide whether a problem is one of conservation of momentum or energy—students will hopefully clue in on the expert mode of reasoning sooner than might be expected by simply doing hundreds of problems.

Once multiple principles have been introduced, it may be wise to focus on teaching and practicing how to categorize problems. Since this is such an essential feature of expert problem-solving, physics students would do better if they spent more time practicing how to distinguish problem types, not merely solving them.

The authors also strongly advocate for active learning. Active learning involves the student in constructing knowledge, not merely passively receiving it. Active approaches typically advocate for problem-solving, hands-on experimentation and exploration, and frequent testing and feedback in the learning process.

Some strategies for implementing active learning that receive some evidence in support include:

Frequent testing and retrieval practice. Students tend to prefer reading their notes, but they learn more from attempting to solve problems.Interleaving examples with testing. This can help offset some of the cognitive load problems of pure problem-solving while still encouraging active practice among students.Desirable difficulties. Spacing, retrieval, and interleaving different examples side-by-side have all been shown to enhance learning, even though students tend not to realize their effectiveness.Flipped classrooms. Instead of an in-person lecture and take-home problem sets, video lectures are given for homework, and students work on their problem sets in the classroom, where peers and teachers can offer feedback and help.Clicker questions and pair-and-share. Interrupting the flow of the lecture for brief quizzes both encourages learning and informs teachers of when their explanations aren’t hitting the mark.Self-explanations. Students who try to explain worked examples or their own solutions understand the problems better than those who don’t.Some Final ThoughtsOverall, I enjoyed this book, and given its slim size, I highly recommend it to anyone who has to teach or learn physics. I suspect many of the same ideas would apply to any STEM-based subject, although certainly, the challenges of learning organic chemistry or molecular biology differ somewhat from classical mechanics.

My only concern with the book was that it largely sidestepped controversies over the empirical status of educational theories. In a prominent paper, Lin Zhang, John Sweller, Paul Kirschner, and William Cobern argue that the support for problem-based, inquiry and other pedagogical innovations has been overstated. They argue that many of the experiments that support reform approaches have altered many aspects of instruction at once. In contrast, carefully controlled studies aimed at assessing the efficacy of individual components of those instructional strategies have often not supported their use.

For instance, problem-based learning is a popular approach to active learning, arguing that students should be taught less and spend more time actively solving problems. However, Sweller’s research has found that novices learn faster and perform better after studying examples than solving the problems for themselves. Similarly, inquiry-based approaches, which model the learning process on how expert physicists do science, may be less effective than direct instruction.

My takeaway from the ongoing controversies is that active learning should not be confused with unguided learning. It’s important for students to think actively, try to understand deep concepts and see the broader context in which textbook problems are situated. But, it also seems clear that student activities cannot be a substitute for thorough and explicit teaching.

For a physics student, it seems clear that ample practice and examples are important. But we should also be focused on understanding why certain problems are solved the way they are—not just mindlessly inserting equations but stepping back to ask which principles are at work (and hopefully getting feedback from peers or teachers) to see if our intuitions are correct.

The post The Science of Learning Physics appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 23, 2024

The 10,000-Hour Rule is a Myth

Few ideas about learning are as well-known as the 10,000-hour rule, popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his 2004 bestseller, Outliers, where he argued that it takes roughly that long to master a skill.

The basis for Gladwell’s rule was Anders Ericsson’s 1993 paper arguing that large quantities of deliberate practice could explain world-class skill levels. Before that, psychologist John Hayes’s research on elite composers, artists and poets found roughly ten years were necessary to produce master-level works.

As with many popularizations of academic research, the public understanding of the rule is at odds with the actual research used to generate it.

What the 10,000-Hour Rule Gets Wrong About the ResearchThe most common misunderstanding of the 10,000-hour rule was the assumption that time spent simply using the skill was what ultimately mattered.

Clearly, this is absurd. Anyone who performs a skill as their full-time job will eventually accumulate ten thousand hours of sustained use. Yet very few musicians, artists, athletes or chess players perform at a truly world-class level. Consider an example from classical music: Tens of thousands of violinists play full-time in professional orchestras, yet there is only a handful of violin virtuosos. The rarity of world-class performance implies that just doing something a lot cannot be sufficient.

Ericsson argued that it wasn’t just any practice that led to mastery, deliberate practice was the key. That meant strenuous training under the helpful eye of an experienced coach. Just playing music wasn’t enough, it was necessary to practice the challenging sections repeatedly, with a skilled coach offering guidance on exactly what to pay attention to in order to improve.

This isn’t a subtle distinction. A popular view of skill development is that extensive practice assists learning by making mental actions increasingly automatic. Thus, you learn to read by first painstakingly recognizing the letters, then identifying them easily, until finally, you’re not even aware you’re recognizing the letters at all—you simply read the text.

But automaticity can also be a curse. When a skill is completely fluent, you aren’t able to consciously monitor your performance and make necessary adjustments. Deliberate practice is an effortful activity designed to bring elements of skills back under intentional control to override automatic habits.

But Is the Underlying Research Even True?Ericsson’s research argued deliberate practice, not just doing something a lot, was what counted towards the ten thousand hours. But is that even true?

Ericsson’s research has faced at least two lines of critique over the years since it has become well known.

The first critique concerns Ericsson’s emphasis on practice over talent. In his view, if large quantities of effortful practice could explain world-class performance, why do we need the residual concept of talent? However, other psychologists disagree, arguing that learning rates often differ between individuals in ways that can’t be explained simply by practice alone.

I think the safest interpretation of the research to date is that natural ability and deliberate practice interact. Nobody becomes world-class without practice, but even ideal coaching and practice conditions will not result in everyone learning at an identical rate. Since world-class performance is at an extreme end of a distribution, the result is that most exceptional people are both extremely talented and incredibly hard-working. Those who are merely one or the other don’t make the cut.

(As a practical matter, this is primarily an issue for elite levels of skills. I think practice tends to matter more for skills you want to be “decent” at because it’s easier to compensate for lack of talent by working harder. But if everyone is working their hardest, as we would expect in the elite of a field, then hard work necessarily plays a smaller role in accounting for the differences.)

Another critique argues that quantity of practice doesn’t actually account for much of the variance in elite performance across fields. This survey finds that practice volume explains only a paltry 18% of the variance in chess performance, 23% in music, and a dismal 1% in professional attainment.

Ericsson has mounted counterarguments to both of these attacks. My understanding of his position on talent is that most abilities are modifiable through sufficient practice (never arguing everyone will learn equally fast). He has also written a rebuttal to the finding that deliberate practice doesn’t explain much by arguing that the studies reviewed mix deliberate practice and time spent simply using the skill.1

My view is that the deliberate practice hypothesis is a compelling and useful mental model for approaching skill development, but both innate ability and factors outside of practice likely also play a role. Reality is complicated. Go figure.

A Deeper, Commonsense Critique of 10,000 Hours Being Necessary for MasteryBut, to me, all of this is beside the point. The 10,000-hour rule cannot be a rule of learning simply because it describes a social phenomenon, not a cognitive one. Let me explain.

A world-class performer in a field isn’t defined by some objective level of skill but by how they compare to other practitioners. Being ranked as an elite chess player isn’t based on some objective measure of chess ability; rather it’s an implicit comparison to all other chess players.

Ericsson himself cites evidence that musicians have gotten better over the centuries, as instruction has begun earlier and more successful teaching and practice approaches have developed. 2

He cites songs considered unplayable by their composers, which have since been performed by increasingly adroit performers.

Similar advances in human performance can be seen across many fields, from athletics to chess to video games. Since objective levels of ability have risen over time, the bar for what constitutes “elite” performance is continuously rising.

Because world-class performance is a social comparison, the quantity of practice (or talent) needed to achieve it depends entirely on how much other people invest in the skill. A more competitive field, all else being equal, requires more time to master simply because there are more people who have invested large quantities of deliberate practice time.

Consider two fields, one with 100 performers and another with 100,000 performers. Suppose that practice time in the field follows some regular distribution, and practice is the sole variable explaining attainment. To be in the top ten (10%) for the first field will necessarily require a lot less practice than to be in the top ten (0.01%) for the second, simply because the latter is a much more rarefied group.

Of course, practice probably isn’t the only variable for attainment. Additionally, some fields encourage many people to devote their entire lives to pursuing excellence, whereas, other fields aren’t highly valued in our society, so nobody invests much time trying to get good at them outside of a few obsessive enthusiasts.

Thus, the real formula for world-class talent would need to consider:

How many people practice in the field.The distribution of deliberate practice quantity by people in the field. (Some fields may inspire more devotion than others.)The cut-off for being considered “world-class” or “elite” in performance.The relative contribution of practice and other variables (e.g., random chance, innate talent, political favoritism, etc.) to success.For skills where there are consistent returns to practice, large quantities of practitioners who generally practice a lot, and a high bar for being considered “world-class,” the amount of practice needed to achieve mastery would likely be a lot more than 10,000 hours.

In contrast, for skills that rely mostly on talent or luck, have few practitioners, little devotion to practice, and modest thresholds for success, the amount of practice needed to reach elite levels might be quite modest.

Implications for MasteryTo summarize:

The 10,000-hour rule only applies to deliberate practice, not just using the skill a lot.Talent probably matters, even if practice does, too.The amount of variance explained by practice in different fields likely varies, but it’s certainly not 100%.“Elite” or “world-class” are social comparisons. Thus, reaching them implicitly requires you to do more than your competitors. Fields with fewer performers, less devotion and lower returns to continued practice will see elite performers with less training.

While I’ve long been a fan of the research the 10,000-hour rule was built upon, I’m skeptical that the rule itself provides much practical value in the pursuit of mastery.

The post The 10,000-Hour Rule is a Myth appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 15, 2024

Life of Focus Is Now Open for a New Session

Life of Focus, the three-month training program I co-instruct with Cal Newport (author of Deep Work), is now open for a new session. We will be holding registration until Friday, January 19th, 2024 (midnight, Pacific time).

This course aims to help you achieve greater levels of depth in your work and life. How would it feel to have more time and energy for the things that really matter to you?

We split the course into three, one-month challenges. Each challenge is a guided effort to help you establish and test new routines, alongside specific lessons to deal with issues you might face. Those challenges are:

Month 1: Establishing deep work hours. We all know we could get a lot more done with less stress if we had more time for deep work, but actually achieving this regularly can be tricky. The first month focuses on finding and making the subtle changes you need to get in more deep work—without working overtime.Month 2: Conducting a digital declutter. Technology can be great, but it can also make us miserable. Having endless distraction within arm’s reach, it’s hard to engage in meaningful hobbies and have deeper interactions with our friends and family. This month helps you cultivate a more deliberate attitude to the digital tools in your personal life.Month 3: Taking on a deep project. In the final month, we’ll reinvest the time we’ve created at work and at home in a project that engages you in something meaningful. This can be learning something new or actually creating something instead of just passively consuming. Lessons will help you learn how to integrate deep hobbies into your busy life.Life of Focus may be the most popular course we’ve run—and one in which students have reported some of the strongest results. This is because Life of Focus is action oriented—not just consuming information, but making sure you form lasting changes to your life.

Registration is open now. If you’re interested, click below. Registration is only open until Friday:

www.life-of-focus-course.comThe post Life of Focus Is Now Open for a New Session appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 13, 2024

Why Build a Life of Focus?

This is the last warm-up lesson before Cal Newport and I reopen our popular course, Life of Focus. During the three months of the course, we’ll guide you through structured exercises designed to increase the quality of your time spent at work—and at home.

The quality of your life is determined by what you choose to pay attention to.

Attention determines your work. It determines whether you make strides on meaningful, challenging projects, or waste your hours on frivolous tasks. It determines whether you get everything done in a timely manner, leaving your evenings free, or feel compelled to push work into nights and weekends to get things done.

Attention determines your mood. It determines whether you feel inspired and engaged to help those around you or spend your days afraid or angry at the things you cannot change.

Attention determines your relationships. It determines whether you cultivate deeper relationships with the people who matter most or are checked out and distant.

Attention determines your experience.Ultimately, our lives boil down to the things we pay attention to. We direct the narrow window of our minds toward some things and not others, and our lives are a series of choices about which things we focus on.

Unfortunately, attention is also largely automatic. We don’t usually make a deliberate choice about what to pay attention to. Instead, our attention is driven by instincts that evolved over millions of years, in an environment that barely resembles our modern life—instincts that are sometimes counterproductive in our modern world.

Building a life of focus isn’t about eliminating entertainment, focusing excessively on personal productivity or adopting a monomaniacal obsession. Instead, it’s more basic: it’s about reclaiming some of our attention and aiming it at the things we choose, rather than the things that have been chosen for us.

In work, a life of focus means that you deliberately decide what matters, not just checking off the to-do list, but doing the work that will become your legacy.

At home, a life of focus means you cultivate attention for the people and activities that enrich your life, and leave out the stuff that leaves you feeling empty, anxious or angry.

In your mind, a life of focus means you learn and build, rather than just passively consume.

_ _ _

Next week, Cal Newport and I will be reopening our course, Life of Focus. The course is a three-month program designed to help you reclaim your attention. In the first month, we’ll increase our capacity for deep work—the sustained attention and engagement needed to do what matters. In the second month, we’ll do a digital declutter, rethinking our relationship with social media and electronic devices, learning and keeping what enriches our lives and leaving out what doesn’t. Finally, in the third month, we’ll tackle a project to learn or build something valuable to us—we’ll use the time and energy we’ve gained to engage deeply in something we can be proud of.

Life of Focus is our most popular course for a reason. I hope to see you in the course, and we can start building a life of focus together!

The post Why Build a Life of Focus? appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 11, 2024

Decide Your Next Decade

Next week, Cal Newport and I are opening a new session of our popular course, Life of Focus. This three-month course has helped thousands of people struggling with distraction become more focused in their work, life and mind—so they can pay attention to what matters most. This week, we’re sharing lessons drawn from the course. If you missed the first two lessons, you can find them here and here.

What could you do in the next ten years if you knew you could focus on anything you chose?

Would you learn multiple languages? Get in incredible shape? Build a business? Become a star performer in your field, or invest wisely and retire early? What kind of life could you make for yourself?

We’re not used to thinking in terms of the next decade. For most of us, our horizon of concern is defined by our current problems: getting through the current project at work, graduating from our degree program, responding to daily stresses and frustrations.

The idea of proactively envisioning the next decade can seem overwhelming. But there’s a benefit to thinking longer. Ten years is long enough to accomplish many serious ambitions: truly mastering a skill, building a company from the ground up, reaching the apex of your career, or completely transforming your habits.

What Could You Do in a Decade?

What Could You Do in a Decade?I find it useful, as an exercise, to imagine what I might be able to do in the next ten years. The point of the exercise is not to meticulously or exhaustively plan out the years of your life—even dogged pursuits of a singular ambition usually require more flexibility than that. Instead, the point is to try to remind yourself of what you’re interested in and passionate about to find the “why” of focus in your life.

The next time you have fifteen minutes today, sit down with a blank piece of paper and write down what you would like to imagine your life could be like in ten years:

What kind of work do you do?What are your relationships like with friends and family?What skills have you mastered?What are you doing for fun?For the things you wrote down on your list that aren’t part of your life now, write down what you would need to focus on over the next ten years to make that a reality. If your future self is fluent in a language, what kind of practice would you need to do to get there? If you have a successful business, what types of projects would you have to complete to launch one?

Tomorrow and the Days AfterImagining how you’d like the next ten years of your life to be, and then asking yourself what a reasonable investment of energy would look like to accomplish those things, leads to an obvious follow-up question: how does the daily life needed to reach those ambitions compare to what you’re doing now?

There will always be a gap between our highest pursuits and our everyday reality. But being mindful of that gap is one of the best motivators to make change. It may be hard to hit a distant target, but as the motivational speaker Zig Ziglar remarked, “If you aim at nothing, you will hit it every time.”

I’m curious to hear your goals for the next decade of your life, and what you think is the gap between your current actions and what you’d need to do to reach them. Share your thoughts in a comment on the original essay!

Next week, Cal Newport and I will reopen our course, Life of Focus, for a new session. If you want to become more focused in your life and work—paying more attention to what matters—our three-month program may be the perfect first step.

The post Decide Your Next Decade appeared first on Scott H Young.

January 9, 2024

The Psychology Behind Why You Can’t Put Down Your Phone

Next week, Cal Newport and I are holding a new session of our popular course, Life of Focus. The course is a three-month program designed to help you become more focused in your work, life and mind—so you can pay attention to what matters most. This week, we’ll be sharing lessons drawn from the course. You can read the first lesson here.

The iPhone is less than two decades old. Yet the psychology behind why it is so hard to put your phone down has been understood for almost a century.

In 1898, the great psychologist Edward Thorndike proposed one of the first rules of behavior: The Law of Effect. Stated simply, rewarded actions tend to increase.

Just as a rat that gets rewarded with food when it pushes a lever tends to push the lever more often, every time we check our phones and get a viscerally rewarding stimulus, it strengthens our habit of phone-checking.

Given this relationship, a reasonable assumption would be that the more consistently an action is rewarded, the more durable the behavior will be. We might expect that a rat that gets a pellet every time it pushes a lever would push the lever consistently. Likewise, we might assume that a burst of entertainment every time we open our phones ought to make us thoroughly obsessed with them.

Except, this isn’t what early behaviorist psychologists discovered. Instead, unpredictable rewards tend to result in far more durable behavior. The rat that only sometimes gets a food pellet will persist in pushing the lever long after the machine stops dispensing pellets. The human being who only sometimes sees an interesting bit of news will keep refreshing her feed long after there ceases to be anything new or interesting.

Explaining Compulsive Phone-Checking

Explaining Compulsive Phone-CheckingWhy should unpredictable rewards be more robust than consistent ones? One explanation is adaptive: if I pull the lever and it reliably gives a treat, not getting a treat might indicate the resource has run out. In contrast, if treats only arrive some of the time, a steady period without rewards might just be a streak of bad luck.

This psychological quirk helps explain why slot machines are so addictive—and why social media algorithms compel us to check our phones, even though most of their content isn’t particularly interesting. The last twenty times may have been a dud, but maybe this next time …

Unfortunately, this law of behavior makes kicking our wasteful social media habits much harder. Just as a compulsive gambler keeps pulling the arm on a slot machine long after it has become clear the game is a losing bet, we continue checking our phones even when the value we get is far less than the price of constant distraction.

Kicking Digital CompulsionsIn the second month of Cal Newport and my course, Life of Focus, we guide students through a digital declutter. For one month, you restrict non-mandatory social media and device usage. While one month isn’t enough to eliminate all the behavioral reinforcement built over years of phone-checking, it is long enough to provide some psychological distance that can help you evaluate which tools and services really are worth keeping—and which ones you don’t miss at all.

Next, we cultivate a more deliberate and conscious form of consumption. We help our students selectively bring back the tools, devices, websites and services they find useful—with carefully constructed guard rails so they won’t take over their lives.

If you’ve ever wished you could read more books, be more present with your family, or avoid the daily onslaught of negativity so many services seem to push, curated consumption is a saner way to deal with your online media.

_ _ _

If you found this lesson helpful, you should join Cal Newport and my course, Life of Focus, for our next session, starting on Monday!

The post The Psychology Behind Why You Can’t Put Down Your Phone appeared first on Scott H Young.