Scott H. Young's Blog, page 12

October 17, 2023

My #1 Rule for Writing

I’ve written a lot of stuff: over 1600 articles, five books (ten if you include those originally published directly to the blog), countless video scripts, email newsletters and more.

Quantity, of course, is no guarantee of quality. There are still many things I would like to improve about my writing. Hopefully, given a few more decades of practice, I’ll be able to do so. But, by this point, I can at least claim to have some experience.

Given my history, budding writers occasionally ask me for tips. My usual reply is to write a lot. Write—and publish—one hundred essays before you start to scrutinize your work. The thought of publishing something (even just online) is paralyzing to most new writers, so overcoming that hurdle is bigger than finessing your prose.

But supposing you’re writing regularly, what should you write about?

Write What You Like to ReadThe only rule I’ve ever kept for myself as a writer is to strive to write the kinds of things I enjoy reading. Writing for yourself may sound narcissistic, but it’s closer to the opposite. If you don’t care about what you’re writing, why should anyone else?

Writing for yourself can be harder than it sounds. For one, what we like to read is generally smarter, wittier, more imaginative and thought-provoking than what we feel capable of producing. Especially in the beginning, taste typically outpaces proficiency.

A second difficulty with writing for oneself is that, for non-fiction at least, we enjoy reading about things we don’t already know. And we also dislike writers who don’t know what they’re talking about. Thus, writing what you like to read requires scrutinizing the ideas and knowledge you take for granted: How would you judge this writing if you didn’t already know everything it discusses?

Writing what you like to read leads to better prose. Do you hate rhetorical questions? Don’t use them.1 Do you like it when writers open with a story, or do you wish they would just get to the evidence for their argument? Do you like short sentences? Or are florid descriptions elaborating the subject in meticulous detail more to your liking?

There isn’t a “correct” answer. Write what you like to read. There are no rules in writing other than this.

It can take some reflection to figure out what kind of writing you like. First impressions can be misleading. I’ve done exercises where I study writing I like. Often, what I thought I liked about a piece of writing turns out not to be there at all. Upon re-reading an author I admired for the depth of his research, I found that the book contained only a handful of citations.

Only when you really start examining why some writing appeals to you do you have any hope of recreating it in your own work.

The Perils of Writing for Someone ElseWriters don’t always have a choice about how they are to write. Publications have house styles. Corporate gigs expect you to match the boilerplate. Scientific journals expect your research papers to conform to a particular template.

Thus, the advice to write what you like to read must always be viewed within the constraints of the place you choose to publish. However, even within those sometimes confining shackles, you can identify writing you enjoy and writing you don’t.

Our ability to simulate the thought processes of others is worse than we typically think. “I don’t like this, but so-and-so will” is not only condescending, it’s almost always false. People may like different writing styles than you do, but it is rare to reverse engineer that appeal without also enjoying it yourself.

The joy of writing isn’t making tons of money or having people laud your work—those things are rare enough to frustrate even the best writers. Instead, it’s the satisfaction that comes from writing something that you think is good. Write what you like to read, and regardless of what others think, you’ll have something you can be proud of.

The post My #1 Rule for Writing appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 10, 2023

Self-Efficacy: The Key to Understanding What Motivates You

If I could recommend only one concept to learn from the psychology of motivation, it would be Albert Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy helps explain many puzzles of our motivation:

Why do we give up on our fitness plan, even though we know we need to be healthier? Why do we waste time on our phones instead of studying when the exam date looms close? Why do we sometimes feel excited to take on a new challenge but other times shrink away?Understanding self-efficacy can also help us build our motivation. But to appreciate the theory, we need to step back and take a look at an earlier, simpler theory of motivation that self-efficacy was intended to correct.

Rational Expectations: Motivation for RobotsRational expectations was a prominent theory of motivation, independently proposed by both Edward Tolman and Kurt Lewin in the first half of the twentieth century.

It proposes that our subjective feeling of motivation is an unconscious calculation of the benefits and costs we’d experience from taking an action. Put mathematically:

Motivation = Benefits x Probability – Costs

To use a concrete example, according to rational expectations, the motivation I feel for exercising would come from the benefit I expect to achieve (getting in shape), multiplied by the chance that exercising leads to that benefit, minus the costs of effort of sticking to my fitness program.

As implied by its name, rational expectations are, well, rational. This theory suggests that whenever we don’t feel motivated, it’s simply because we’ve judged another option to be more valuable for us. Accordingly, if we failed to exercise and sat around watching Netflix instead, we valued keeping up on our shows more than having a beach body. No mystery at all.

Rational expectations isn’t a terrible theory—it’s probably a pretty good approximation of why we’re motivated in many cases. But it’s also the kind of motivational theory we’d expect of a robot, rather than a human being—it assumes we perfectly weigh the options and always make the right choice.

Motivation for Humans: Self-Efficacy IntervenesAlbert Bandura theorized that what was missing from rational expectations was an intervening step. It isn’t enough to have expectations about the outcomes of our actions; we must also have expectations about our ability to take those actions.

Consider our exercising example again. Bandura argued it isn’t enough to look at our expectations about outcomes (the chance that exercising will improve our fitness). We must also examine our expectations about our ability to take action (whether we believe we can stick to our exercise program). The former may be high enough to justify the cost, but we’ll be stuck with low motivation if the latter is low.

Bandura articulated it in the following way:

Self-efficacy helps to explain why, even when we want an outcome, we might not work toward it:

It’s not just our desire to graduate, but our belief that we are capable of learning the material.It’s not just our desire to own a business, but our belief that we can make it successful.It’s not just our desire to have a relationship, but our belief that we can ask someone out without being rejected.Bandura’s theory improved on rational expectations because it argued that wanting an outcome isn’t enough to motivate you into action; you must also be confident in your ability to take the actions required to reach that outcome.

Common Confusions About Self-EfficacyBefore I explain some of the implications of self-efficacy, I want to clarify what self-efficacy is not:

Self-efficacy is not self-esteem. Self-esteem is how you value yourself. Self-efficacy is your belief that you can succeed in taking a particular course of action. You can believe you’re wonderful while also believing you’re incapable of learning quantum mechanics.Self-efficacy is not self-concept. Self-concept is how you think about yourself. Self-efficacy is about how you think about your ability to perform a given set of actions.Self-efficacy is not confidence. As Bandura explains, “Confidence is a nondescript term that refers to strength of belief but does not necessarily specify what the certainty is about. I can be supremely confident that I will fail at an endeavor.”Self-efficacy may be an academic theory, but we all have some experience with the concept. We can recall situations where we felt assured of our abilities, and others where we seriously doubted we could succeed. We know first-hand the consequences these beliefs had on our motivation.

Bandura’s contribution goes beyond merely labeling this common experience and suggests important implications for understanding our motivation.

What Causes Self-EfficacyBandura’s research found that there are four major moderators for self-efficacy.

The first two were weak moderators—they could have small effects, but they weren’t reliable:

Bodily arousal. Think of the sweaty palms and racing heart that accompany stage fright or the queasiness that comes before a big exam. These can make it harder to perform, even if you otherwise would be able to in a relaxed state.Verbal persuasion. The crowd cheering as you finish a race. A teacher telling you that you can do it. Simple affirmations that you can or can’t do something can influence self-efficacy, but the impact is unreliable.In contrast to these weaker effects, Bandura identified two more consistent sources of self-efficacy:

Vicarious experience. Witnessing someone perform the task increases self-efficacy. Firstly, this works by giving us a way to learn an effective strategy: If I watch someone solve a puzzle, I can copy their approach to get the same result. There is also a motivational piece: If I see another spider-phobic person touch a tarantula, I might gain courage to do so as well.Personal mastery. Personally experiencing success with a task (or something like it) is the most powerful tool improving self-efficacy. I’ll feel more confident I can run a marathon after I’ve run a half-marathon. I’ll feel more confident I can be a software developer after I’ve aced my intro programming class.It’s likely that people with strong self-efficacy, and thus, high degrees of motivation to work on ambitious goals, have had plenty of both vicarious and personal mastery experiences.

Non-Obvious Implications of Self-EfficacyWhile the feeling of self-efficacy is something we all know, the implications of the theory are not always obvious.

Here are a few important corollaries of the theory:

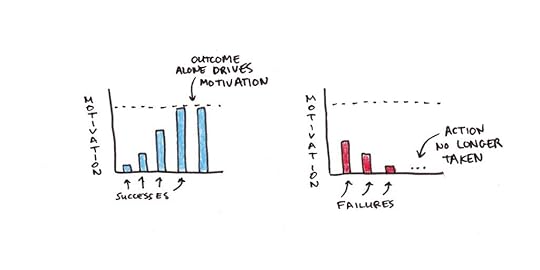

1. Motivation builds from success.Because personal mastery is crucial in building self-efficacy, a long string of failures at the beginning of an endeavor is more likely to demotivate than build grit.

Does this mean that the best way to motivate is to experience only success? Not quite. As Bandura himself puts it:

Performance accomplishments provide the most dependable source of efficacy expectations because they are based on one’s own personal experiences. Successes raise mastery expectations; repeated failures lower them, especially if mishaps occur early in the course of events. After strong efficacy expectations are developed through repeated success, the negative impact of occasional failures is likely to be reduced. Indeed occasional failures that are later overcome by determined effort can strengthen self-motivated persistence through experience that even the most difficult of obstacles can be mastered by sustained effort. The effects of failure on personal efficacy therefore partly depend on the timing and the total pattern of experiences in which they occur. Once established, efficacy expectancies tend to generalize to related situations.

If you have low self-efficacy, it helps to build a foundation of success. Once you have established a basic level of confidence, mixing challenges with occasional setbacks helps make that self-efficacy more robust. You’ll learn that you can succeed, even in the face of momentary difficulties.

2. The confidence spiral can go up—or down.The mathematics of self-efficacy form a positive feedback loop. Consider:

You have some self-efficacy, which enables you to take action and achieve a result.Success from taking the action increases your self-efficacy.Next time, you are more motivated to take the previous action.Repeat.Eventually, your motivation would plateau at the level implied by the rational expectations theory (which is one reason why even some tasks we’re supremely confident in, like washing dishes, don’t inspire ecstatic motivation).

Conversely, motivation can also crash as we experience lowered self-efficacy:

You have some self-efficacy, and take action, but you fail to follow up or fully complete the action.Not achieving the desired result decreases your perceived self-efficacy.Next time, you have less motivation to take the previous action.Repeat.This motivation spiral plateaus at total inhibition to take the desired action. The effect is familiar to anyone who has tried a new pursuit a few times, stumbled, and then found it difficult or aversive to attack the problem again. Low self-efficacy can be a trap we stumble into.

3. Learn from Others, Succeed Yourself.

3. Learn from Others, Succeed Yourself.Self-efficacy was only a part of Bandura’s broader social learning theory. In it, he argued that most of what we know comes from other people, and we learn how to do most things by witnessing the behavior of others—not through our own trial-and-error.

This suggests that a critical way to build self-efficacy is to closely study people who are successful in the pursuit you care about—see how they do it until you understand the actions they’re taking and why. Their success isn’t a mystery; it’s a logical outcome of the series of decisions they have made and actions they have taken.

If you combine this careful study approach with taking the same actions yourself, you’re using the two most powerful levers Bandura identified to increase your self-efficacy and, thus, your motivation for working on challenging goals.

Sources:

Bandura, Albert. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1997.

Bandura, Albert. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1977.

The post Self-Efficacy: The Key to Understanding What Motivates You appeared first on Scott H Young.

October 3, 2023

18 Life Lessons I’d Give My 18-Year-Old Self

I started writing this blog when I was a few months shy of 18 years old. Since I’m now twice as old as I was when I started, I thought I’d take some time to reflect on advice I wish I could have given my younger self.

1. You’ll have more dating success if you strive to be relaxed rather than confident.

1. You’ll have more dating success if you strive to be relaxed rather than confident.Most dating advice for young men is terrible. One of the most misunderstood is the recommendation to “act confident.” Pretending to be confident when you’re not usually makes you look like a jerk or a buffoon. In contrast, genuinely confident people tend to be relaxed.

2. Make friends with the exchange students.People who deliberately choose to live abroad for a year are more interesting, on average, than those who are closed to such experiences. Exchange students also tend to be looking to make friends. (This also is a good way to get more opportunities to apply lesson #3.)

3. Say yes to invitations to visit a friend in their home country whenever possible.Being shown around by a local is vastly better than being a tourist. This is doubly true if you make friends with people from non-touristy places.

4. Learn how to cook.I spent too many years eating terrible food because I didn’t know how to make good meals. The remedy is to find recipes online and follow them to the letter. Eventually you can improvise once you’ve learned the basics.

5. Optimize for experience, not grades, in college.My biggest mistake in university was choosing to take classes in English, not French, during my year abroad. I was worried I wouldn’t keep up academically, so I chose the easier option. I didn’t realize I was also missing out on the best way to learn the language.

6. Go to more parties, but drink less.Drinking has strongly diminishing returns for enjoyment, and hangovers are not fun. Thus, if you’re going to partake, pick a strict cutoff and stop when you hit that amount. You’ll enjoy more parties with fewer headaches.

7. Learn to separate challenging situations from toxic ones, and don’t feel guilty abandoning the latter.You won’t regret sticking to hard challenges, but you’ll regret burning yourself out in situations where your values don’t align with what you’re being asked to work on.

8. Learn to recognize assholes and refuse to deal with them.Assholes often seem cool, successful or important. In the short term, it often feels like you should just put up with their personalities to further your goals. But in the long-term, you’ll almost always regret not cutting them loose sooner.

9. Never date a person you wouldn’t also be friends with.It’s easy to overlook personality differences when enthralled by a person’s more superficial characteristics. But those relationships rarely work out. My wife and I, who have now been together for nine years, were just friends for eight years before that.

10. Avoid premature optimization.When you’re young and broke, a job that pays a lot of money (to you) can be very attractive. Unfortunately, if that job doesn’t help you build skills you’ll care about when you’re middle-aged, you may be better off declining the opportunity for a lower-paying job that does. While you need money to live, resist the temptation to cash in early.

11. It’s okay to be (a little) weirder as an adult.High school enforces an unusually high degree of conformity. In high school, even “weird” kids tend to conform to a particular clique rather than be genuinely interesting. Outside of high school, however, there are fewer penalties for being a little different, and there is more potential upside as there is a larger pool of potential friends whose interests may overlap with yours.

12. Don’t waste your electives on “easy” classes.Depending on your major, you may only have a handful of classes that you can choose for yourself. Don’t waste these! Take interesting classes from different departments rather than the easy-A class that teaches you Microsoft Word.

13. Spend less time on your computer and more time at in-person events.It’s even better if those events have nothing to do with your current friends or interests. Bulk-positive randomness is a powerful force, but it can’t move you if you stay inside your dorm room.

14. Ask yourself what a more extraverted version of you would do, and then do that.Introversion is great when you’re settled into a job and family life. But when you’re young, exploring the maximum possible options for your future is important, so striving to be a more extraverted version of yourself is generally desirable.

15. Travel as much as you can.Yes, traveling can be expensive. But you’ll never be able to travel as cheaply, or have as many interesting experiences, as you can when you’re young.

16. Press your clothes, comb your hair and wash your face.I’ll admit my appearance has never been something I’ve thought a lot about. But getting the basics right is usually not too onerous, and they matter a lot more for how people see you than how much money you spend on your clothes or how much you work out at the gym.

17. Don’t be so dogmatic.I’ve softened in many ways as I’ve gotten older. While youthful intensity about beliefs, goals or projects can be incredibly valuable, it can also get in the way of having new experiences. It’s better to avoid being too rigid when you don’t yet know which ideas of yours really ought to be inviolable.

18. Call your parents more often.Since becoming a father, I’ve come to appreciate my own parents in a way that would have been difficult to understand as an eighteen-year-old. While it’s easy to get absorbed in your own new experiences of adulthood, it’s worth taking some time to keep up the relationships that have been with you all your life.

What advice would you give your younger self? Any agreements/disagreements with my list? Share your thoughts in the comments!

The post 18 Life Lessons I’d Give My 18-Year-Old Self appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 26, 2023

The Simple Rule for Achieving Ambitious Goals

Economist Bryan Caplan has advice for those who want to succeed at ambitious goals:

When I see the contrast between people who succeed and fail, I generally witness a similar gap in effort. During my eight years in college, I spent many thousands of hours reading about economics, politics, and philosophy. Since high school, I’ve spent over ten thousand hours writing. When young people ask me, “How can I be like you?“ my first thought is, again, do ten times as much.

Ten times as much of what, exactly? The answer is usually: Whatever you already think the crucial ingredient is. “Why can’t I get ahead in my career? I strive to study and emulate my role models.” Great idea; you just need to multiply your effort by a factor a ten. “How can I save my marriage? I’m really trying to make my spouse happy.” Again, great idea. You just need to multiply your effort by a factor of ten.

The 10x Rule has helped me personally.

When I was gearing up to promote my book, Ultralearning, I asked for advice from James Clear, author of the mega best-seller, Atomic Habits. I knew podcasts were important for promotion, but I figured a dozen would suffice.

I asked James how many podcasts he went on. He told me he recorded 80 before the book launched and 200-300 in the first six months after its release.

Doing ten times as much of what you think works doesn’t sound like mind-blowing advice. But it’s startling to me how often the solution to whatever life problem you’re facing is simply doing more to solve it.

Do the Obvious Thing FirstZvi Mowshowitz writes about data collected on dating from singles who want to be in a relationship. From this group, the most typical number of dates they had been on in the past year was one.

Zvi elaborates:

I am not saying that dating is easy or that I found it to be easy. I will go ahead and say it is not once-a-year level hard for most people to find worthwhile first dates.

What I especially find curious is that one is the most popular response rather than zero. It would make sense to me that the answer is frequently zero dates, because you are not trying and aren’t ‘date ready’ in various senses. What’s super weird is that the vast majority did go on the one first date, but mostly they didn’t go on a second, and only half of those went on a third. It is as if people are capable of getting a date, then they go on one and recoil in ‘oh no not that again’ horror for about a year, then repeat the cycle? Or their friends set them up every year or so because it’s been too long, or something? None of that makes sense to me.

If you’re lonely and want to be in a relationship, the solution is obvious: get out, meet more people, ask them on dates and brush yourself off when you face rejection or heartbreak. Worrying about your height, weight, looks, or bank account is a distraction if you won’t surmount the basic hurdle of putting yourself in more potentially-romantic contact with other people.

I could draw a similar lesson from my language learning experiences: the best techniques don’t matter if you’re not using the language enough. The secret to Vat and my success with the No English Rule wasn’t exceptional talent or some magic of immersion. It’s because when you commit to only speaking in the language you’re learning, you end up practicing 10x as much.

Becoming a better writer is another example. I occasionally get emails from people who have started new blogs and want critiques of their writing. Invariably, they’ve written a handful of posts. I believe you shouldn’t worry about technique until you’ve written at least one hundred essays. If you’re not doing that much, finessing the method is pointless. I was at least a thousand essays in before my writing career took off, and I suspect I’m not an outlier.

The Trick is Not Minding That It HurtsIn a scene in Lawrence of Arabia, the titular T. E. Lawrence lights a cigarette and puts out the match by rubbing it between his fingers. Shortly after, another man attempts the same trick:

Man: Oh! [burning his fingers] It damn well hurts!

Lawrence: Certainly it does.

Man: Well what’s the trick then?

Lawrence: The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.

The trick for most ambitious pursuits, I’m afraid, is simply doing the obvious thing much, much more than most other people are willing to do—and not minding that it’s hard at times.

The post The Simple Rule for Achieving Ambitious Goals appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 18, 2023

Top Performer Is Now Open

Top Performer is the course Cal Newport and I teach for helping you deeply understand what drives success in your career, and then gives you the strategy for getting really good at those skills. We hold sessions quite infrequently, and right now we’re opening registration for another one.

If you’d like to learn more about the course, how it works and whether it’s right for you, see the registration page here.

Everything you need to know about the course is in that link above, but here’s a quick summary of what we teach:

Research — We give you the tools to figure out how any career works and what skills you need to develop to reach the next level. This works for people early in their careers, still trying to figure out what they want to do. It also works for people who have already advanced in their careers and need to know what it will take to reach the next level.Practice — We break down methods for translating the important research in mastery of deliberate practice to knowledge work. In particular, we teach you how to set up effective projects that will allow you to quickly build new skills and master ones that matter for your career.Deep Work — Cal and I run through our productivity approaches with a focus on how you can maximize the amount of deep, important things you do every day.Mastery — How can you set up long-term career habits to continually push your career forward. This includes how to assess your career capital, set long-term goals and stay focused on the big picture instead of getting bogged down in the day-to-day difficulties.If you have any questions about the course, our team members will be happy to answer them here: support@scotthyoung.zendesk.com

Keep in mind, registration will be shutting down Sep 22, 2023 – Friday at midnight Pacific Time, so if you’d like to join, you’ll need to act before then.

The post Top Performer Is Now Open appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 16, 2023

The Key to Building Rare and Valuable Skills

In the last three lessons, I’ve discussed the importance of focusing on the career capital that drives people’s success, the logic of supply and demand that explains why rare and valuable skills matter so much, and the crucial importance of correctly identifying the path forward so you don’t burn yourself out working on the wrong things.

Today, I’d like to shift and talk about how you can get good at the skills you need to flourish in your career.

Anders Ericsson and the Legacy of Deliberate PracticeFew psychologists contributed more to the study of expertise than Anders Ericsson. His work studying world-class performance began with a simple memory study.

Digit-span tasks have long been a staple in cognitive psychology research. These are simple tasks where a subject is presented with a list of numbers and then asked to recall as many as they can remember. A famous finding from this type of task is that most people can recall between five and nine digits.

Typically, subjects get little practice on this task. Ericsson, however, worked with a single subject and repeated the same task over many sessions. The result? The subject’s digit span exploded—he could recall over 100 digits at the end of their long training sessions.

In this particular subject’s case, he invented a mnemonic system using running times (he was an avid runner) to recall far more digits than his memory would typically allow.

This experience led Ericsson to a long career studying the effects of large quantities of focused practice on human performance. Experts of all stripes, from doctors to musicians, can achieve things that would overwhelm the minds of novices through these sustained efforts.

Ericsson’s research was a crucial inspiration for Cal Newport and me when we began working on Top Performer. Given the connection between world-class skills and an excellent career, we were interested in seeing how this model of deliberate practice could apply outside of the laboratory, tennis court, or music conservatory—how it could apply to professional areas where such practice efforts weren’t the norm.

Applying Deliberate Practice to the OfficeThere are three basic ingredients to acquire any complex skill:

You need to understand how the skill works. This mostly comes from learning from other people’s examples, so you’re not reinventing the wheel and are using current best practices.You need a lot of practice. Practice lets you perform skills more quickly and automatically. Ericsson’s obsession with deliberate practice stemmed from the seeming removal of a hard psychological limit on human performance, just by practicing a lot. You need corrective feedback. Understanding how a skill works and doing it a lot is generally insufficient to get extremely good—corrective feedback that identifies what you’re doing wrong and offers a replacement is usually needed to continue to improve.Ericsson’s definition of deliberate practice involves focused training sessions away from the demands of productive work. In these sessions, you would pay attention to a key aspect of your performance. Coaching would almost always be required because, otherwise, it’s hard to get adequate corrective feedback.

Such a definition of deliberate practice makes a lot of sense in tightly controlled, high-performance domains such as chess, music or athletics. But what do you do to get better when your job is, as one former Top Performer student put it, “to basically answer emails all day?”

Designing a Deliberate Practice ProjectProfessional skills in real environments are not the same as highly-controlled variables in laboratory studies. Thus, when building rare and valuable career skills, getting the exact kind of deliberate practice Ericsson identified as crucial for world-class skill development is often difficult.

At the same time, we need to avoid the trap of simply accumulating seniority if we want to accelerate our careers. Many practitioners, even ones with years of experience, aren’t exceptionally proficient. Despite years of experience, their skills can stop progressing if they lack a suitable training environment.

Cal and my solution to this dilemma in Top Performer was to guide students in designing a deliberate practice project. This type of project combines a few elements:

It should be focused and specific—not just routine work, but something “extra” that will force your skills to a higher level.You should have an opportunity to study from examples to see how the best do it. Figuring out everything on your own is slow, so a good project begins with a clear picture of how the skill you’re trying to improve works.You should be able to get clear feedback that can drive your progress.Designing a good project is not trivial. You need to find something that is a good fit for the career capital you want to develop. Then, you need to focus your project so that improvement is possible—while keeping it relevant to your working life. Finally, you need to do the work. Each step has its challenges.

However, as we’ve seen with past cohorts from Top Performer, students can succeed with these kinds of projects, and their newly developed skills help them make strides in their work. Students have used projects to land new jobs, get promotions and raises, and become better at their professional craft.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this lesson series drawn from our course, Top Performer. In the full eight-week program, we go into much more detail on how to build a career you love. I hope you’ll consider joining us for our next session!

The post The Key to Building Rare and Valuable Skills appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 14, 2023

Before You Burn Yourself Out Working, Do This

In the previous two lessons, I shared why you should pay attention to successful people’s career capital rather than their personal quirks when trying to emulate their achievements. Next, I applied the economic model of supply and demand to understand why some people are able to negotiate great career perks—money, autonomy, flexibility—while others are not.

Career capital, particularly rare and valuable skills, is the starting point for finding work you love. But how do you get them?

A tempting answer is simply to work hard. While it’s true that success requires hard work and most successful people tend to be hard workers, working hard does not guarantee success.

While it’s nearly impossible to build rare and valuable skills without hard work, tons of people work hard but still don’t have great career capital. As a result, despite their great work ethic, they don’t get the same perks that true top performers do.

Cal and My First Lesson from 8+ Years of Top Performer

Cal and My First Lesson from 8+ Years of Top PerformerYou avoid this trap by building skills that result in useful career capital, so the nuts and bolts of how to build these skills were on Cal Newport’s and my mind as we began working on the first iterations of our course, Top Performer.

We already had an idea about how people build skills—Anders Ericsson, the psychologist who pioneered the concept of deliberate practice, spent decades studying the mental efforts needed to master difficult skills. Focused practice sessions, particularly under the supervision of a coach, can make all the difference in whether your skills will grow or stagnate.

However, when we ran our first sessions for the course, we noticed something different: Most people had no idea which skills they needed to build!

Worse, many people seemed to gravitate towards skills tangential to what really would make a difference. People seemed keen to improve skills that were fun to work on—an effortful project (but not too hard) so they could feel they were doing something to improve, but they weren’t working on what mattered most.

There’s nothing wrong with learning things for fun. But this approach can be counterproductive if your aim is to build career capital. You can spend months improving a skill that isn’t directly related to what employers, clients or customers really want.

There are No Short-Cuts, But Plenty of Dead-EndsRealizing that many people were heading down dead-ends with their deliberate practice efforts, Cal and I adjusted our next iteration of the course: Before getting into intensive skill-building work, we had the students research how their career path actually worked. Once they understood this, they better understood which projects would move them in the right direction—and which ones were a waste of time.

Doing this kind of research is tricky. Most of what you need to know is too specific to be written down in a book or article, so a trip to the library or a web search often comes up short. Instead, you need to talk to people. Yet talking to people who’ve achieved success can be equally frustrating! Even people who have amassed a surprisingly specific set of skills often shrink back to generic platitudes about the value of hard work when asked how they did it.

However, doing this research properly is essential. Knowing the path before you start walking it helps you avoid common traps people fall into when building their career:

Getting a master’s degree that nobody cares about.Working on technical skills when you need people skills.Not finding the right way to present your skills on your resume.Not recognizing which jobs are career-building opportunities and which are dead-ends.After working with many students over the years, Cal and I found that the best people to talk to for this advice are 2 to 3 steps ahead of you in the career direction you’re considering. These people have recently moved up, so their information is up-to-date and fresh in their mind.

Once you find and contact these people, you need to get them to tell you how they got where they are—which is surprisingly diffcult. Early on, Cal and I found that our students were simply asking those people for advice. While this seems like the obvious move, it almost never works. Instead of asking directly, you need to act like a journalist covering the story of this person’s career transition—figure out the where, when, what and why of how they made the career leap you’re currently contemplating.

These two actions, finding people 2 or 3 steps ahead of you in your career and interviewing them to figure out exactly what they did (not just the advice they want to share), help you narrow down which elements of your career capital you need to invest in and which you can ignore going forward.

In the next and final lesson, I’ll share my thoughts on moving beyond identifying valuable skills to actually getting good at them. After that, Cal and I will be opening Top Performer for a new session. If the ideas I’ve been sharing have resonated with you, I think you’ll enjoy the full course where we put them into practice.

The post Before You Burn Yourself Out Working, Do This appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 12, 2023

The Simple Economic Theory That Explains Whether You’ll Have a Great Career

In the last lesson, I explained why focusing on irrelevant details obscures the true driver of professional success: career capital.

But the connection between career capital and a great career isn’t always obvious. Why does the owner of a car dealership tend to make more than a nurse or a teacher? Why would most people struggle to make a living as an artist, but the guy who put a taxidermied shark in a tank is worth nearly half a billion dollars?

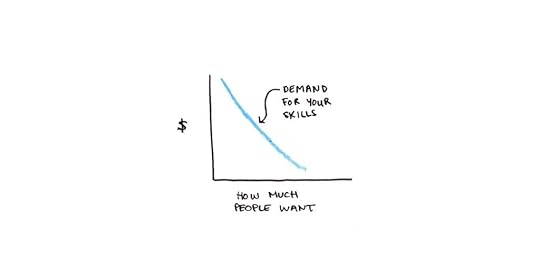

The basic answer of whether you’ll have a great career can be understood in terms of the simple economic concept of supply and demand.

Supply-and-Demand Thinking Applied to Your Working LifeLet’s start with demand.

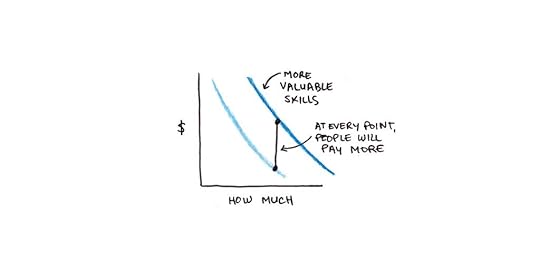

Economists draw a downward-sloping curve to represent how much of something people want for a given price. The vertical axis is how much something costs, and the horizontal axis is how many people are willing to pay for the thing at each price. All else being equal, fewer people are willing (or able) to pay for something when the price is higher.

This curve can be a useful way to think about the value you offer to other people. In the job market, your career capital is valuable if people are willing to pay more for it. A higher-value set of career capital can be represented by the demand curve shifting to the right—more people want someone with your career capital for any particular price.

But demand isn’t the whole story. Water is essential for life, diamonds are not. But water is cheap because the supply of water is plentiful, and diamonds are expensive because the supply of diamonds is scarce.

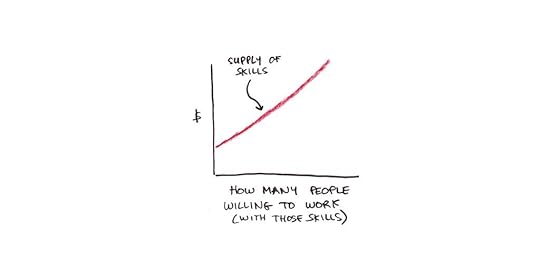

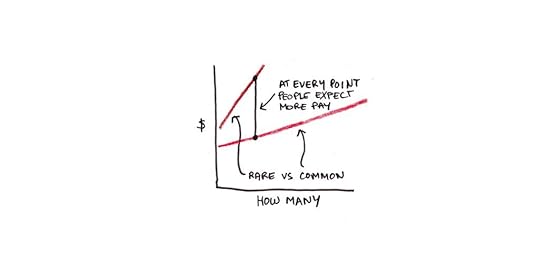

Similarly, the supply curve for your career can be envisioned as the number of people who are willing to supply that career capital (the horizontal axis) for a particular wage (the vertical axis). As the price goes up, more people are willing to supply those skills, connections, reputation and other assets that people want.

The supply curve can also be a measure of the scarcity of your particular career capital. Teachers and nurses earn less than many car dealership owners because there are more people who have the career assets to teach children or work as nurses than own big lots that can sell lots of cars.

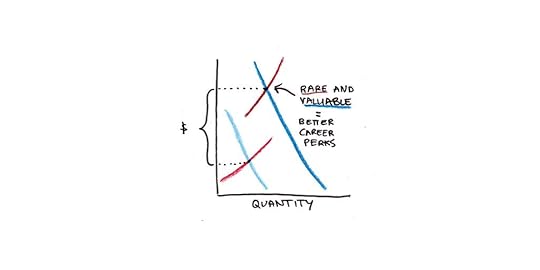

In a normally functioning market, the intersection between the demand and supply curves reflects the price and quantity sold of a given product. If demand is high and the supply is low, the price goes up.

In a career context, the return on your career capital depends on how many people value it, and how many others can supply it. This means to have a good career position, you need assets that are both rare and valuable.

This thinking applies beyond just how much money you make. The person with rare and valuable career assets can, of course, parlay that into a higher income. But those same assets also serve as a negotiating point for anything else you might want: vacation time, interesting projects, professional autonomy, and more. A career you love and a career that pays well may not always be the same thing, but they’re both made possible with rare and valuable career capital.

As a mental model, I find supply-and-demand thinking incredibly useful, but it ignores a lot of important factors. Price caps, monopsonistic employers, professional guilds restricting membership, and more all complicate this basic model. However, it’s still a good baseline for thinking about the kind of career you can have.

Building Rare and Valuable SkillsAs discussed in the previous lesson, skills are often the best starting point for building career capital. Reputation and connections tend to follow, not precede, excellent work, so the best place to start is building the skills that support doing excellent work.

This view reframes the question from how to build a valuable career to: How do you acquire rare and valuable skills?

This was the opening question Cal and I posed when we first started building our course, Top Performer. In the coming two lessons, I’ll share two major findings from working on this issue with thousands of students over nearly a decade. We’re setting up for a new session, starting next week. If you’re interested in building the career capital that actually drives a great career, I hope you’ll join us.

The post The Simple Economic Theory That Explains Whether You’ll Have a Great Career appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 10, 2023

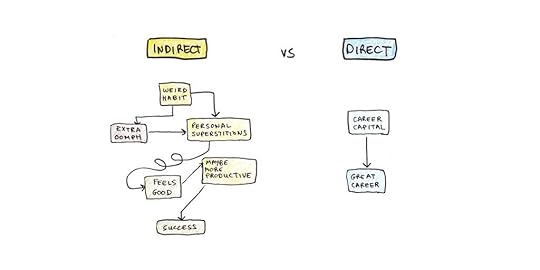

Who Cares What Warren Buffett Eats for Lunch?

A pet peeve of mine is self-help advice that obsesses over irrelevant personality quirks rather than the true drivers of a person’s success.

Hedge fund billionaire Ray Dalio meditates forty minutes per day. Tim Ferriss wrote his bestselling books between 10 pm and 5 am. Warren Buffett famously drinks five cans of Coca-Cola every day.And so on …There isn’t any secret diet, exercise, meditation or journaling exercise that will make you successful. Warren Buffett isn’t rich because of his junk food diet; he’s rich because he is an incredibly skilled investor who has worked continuously for nearly eight decades.

What Really Drives Successful CareersLook, there’s nothing wrong with daily meditation, finding your most productive time to work or drinking colas. (Okay, maybe that last one isn’t so great … )

Instead, my misgiving with this kind of advice is that it’s focused on behaviors that are, at best, indirectly related to a person’s career success. Maybe Ray Dalio is right, and meditation makes him more productive—or maybe he’s just really good at being a hedge fund manager.

A better way to analyze the drivers of success among top performers is to examine their career capital. These are the assets they have that directly produce value for their employers, clients or customers:

Skills. If you can do work few other people can, or you can do it better than most people, you have a powerful bargaining chip when looking for work. People with rare and valuable skills can set off bidding wars in negotiations, whereas people with mediocre levels of common skills usually cannot.Connections. Relationships can also be an asset. A journalist with a long career can often get a book deal, not only because she’s spent years honing her writing skills, but also because she knows tons of people throughout the publishing industry who can talk about her book. Reputation. How do you choose which products to buy? Chances are you don’t buy each possible option and test them at home before returning all but your favorite. Instead of relying on reviews, you pick brands that are high-quality for their price range and ask people you know. The same is true when people hire you.Career capital explains success in a way that incidental habits cannot. While it’s easy to find examples of people who attribute their success to a particular behavioral quirk, it’s also easy to find plenty of cases where people with the same behavior don’t achieve such success.

In contrast, if someone has a successful career, they’re virtually guaranteed to have a lot of career capital.

How to Build Career CapitalCareer capital comes in different flavors, and we’ve already discussed three: skills, connections and reputation.

Among these assets, skill tends to come first.1

Connections are nice if you’re born into a wealthy family, or went to an elite private school and have a great network. But if you don’t, knocking on the doors of random successful people, hoping they’ll be your friend and help you out, is not a strategy most people can pull off.

More commonly, connections follow from doing good work. When you make a name for yourself as being excellent at what you do, people will want to get to know you.

Similarly, reputation often matters more than raw ability. But, as with connections, reputation is a natural by-product of doing excellent work. Reputation follows skill, not the other way around.

Skills also have the benefit of being trainable. While good looks, family money or famous friends may be valuable career assets, they’re not always accessible if you don’t stumble into them.

Anyone can improve their portfolio of skills that can improve their career.

Come Build Career Capital with Cal Newport and Me in Top PerformerFor the last eight years, Cal Newport and I have been running a private course, Top Performer, helping people cultivate rare and valuable skills for their work. If you’re interested in building the assets that actually drive success in your career (and ignoring the things that don’t), we’d love for you to join our next session, beginning next week.

The post Who Cares What Warren Buffett Eats for Lunch? appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 29, 2023

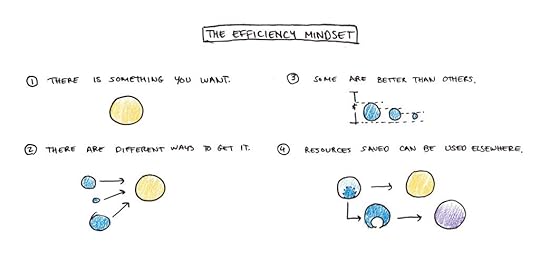

The Efficiency Mindset

Our deepest beliefs are often girded by assumptions we rarely articulate. The mindset of efficiency is one of mine.

The assumptions of this mindset are essentially:

There are things we want.We can take actions to get the things we want.Some actions are more efficient than others—i.e., they will get more of what we seek for less time, effort, money, etc.The resources we save by being more efficient can be spent on other things we want.

To consider a concrete example, think of a task like studying for an exam:

There is something you want: to pass the exam and learn the material.There are actions you can take to get what you want: studying.Some actions are more efficient than others: some methods of studying result in more learning than others.If you use more efficient methods to save time studying for the exam, you can put that time toward other activities you enjoy.The efficiency mindset applies broadly because these assumptions apply to many things. But it’s also important to note where they break down.

Where Does the Efficiency Mindset Break Down?A common criticism of the efficiency mindset is rooted in an overly-narrow interpretation of assumption #1, the things you want.

Consider speed reading a novel. This is “efficient” in the sense that you’re getting through the book in less time. But is that really what you want?

Much of the value in reading a novel comes from enjoying the plot, dwelling in the world of the characters, or pondering the book’s deeper meanings.

When efficiency often fails, it is usually because we’ve adopted an overly restrictive, incomplete, or inaccurate view of what’s valuable about the activity.

While this is a wrinkle in applying the efficiency mindset, it’s not a compelling argument against it. If you incorporate all the things you value, appropriately weighted, then the efficiency mindset still works. It’s essential to include things like “enjoyment” and other often-overlooked values when considering the efficiency of reading novels.

The real failure of efficiency isn’t an overly narrow conception of what we desire, but when assumption #4, that you can reinvest resources saved by being more efficient, breaks down.

When Working Harder Only Creates More WorkCentral to the efficiency mindset is the idea that the time or resources saved through efficiency are fungible. You need to be able to take the time, money or effort saved on doing one thing and apply that to something else. If you can’t reinvest the resources, doing things more efficiently doesn’t pay off.

As a teenager, I worked at a video rental store one summer. Being more efficient working at the store was kind of pointless. The boss would exhort employees to spend idle time cleaning the shelves or tidying the display racks, but people seldom did. When the store wasn’t busy, we just lounged around. When there were tasks to be done, nobody was in a hurry to finish them quickly.

The fact that nobody (except maybe the manager) thought about efficiency made total sense. Working harder didn’t pay off. Our hours were set, we earned minimum wage, and there weren’t performance bonuses for extra effort. Nobody was angling for a promotion or hoping to move up the video-rental corporate ladder. If you finished your work early, there was only more busy work. You didn’t get to do anything more interesting with the time saved.

Additionally, in that environment, working more efficiently was socially costly. Hanging out with the other staff was the only glimmer of joy in an otherwise mindless job, so if you became the person who got everything done with speed, you made your other coworkers look bad.

I’m sure management’s perspective was that we were all just lazy. We were paid to be there and work, so why didn’t we work as hard as possible? But from our perspective, as long as we met our actual job requirements, there was no reason to be any more efficient.

I sometimes think about those days because my current life is worlds apart. I’m my own boss, and my income, free time and personal success depend entirely on my efficiency. However, I’m also aware that if you’re used to environments with no reason to be efficient, “efficiency” is just a byword for what the boss wants you to do.

Efficiency is a Novel ConceptI mention that experience because across different cultures and social organizations throughout human time, I think the situations where it paid to be efficient were relatively rare.

I can’t find the source now, but I recall reading a book where Western researchers came to investigate a remote tribe that engaged in some subsistence agriculture. The tribespeople surveyed often complained about being hungry, wanting more food. But, to the investigator’s eyes, they seemed, well … kinda lazy. They didn’t do what seemed obvious to the anthropologists, simply growing more crops so they’d have more to eat.

The authors claimed this had to do with the social organization they lived in. Supposing you did grow a surplus of food, you could eat as much as you want. But in the close-knit band you lived in, sharing was required. So distant relatives who were hungry would complain to you to give them some of your food. The industrious subsistence farmer wouldn’t have much incentive to work hard since any surplus would likely be taken away.

As this is beginning to sound like a cloaked libertarian allegory, I think it’s worth pointing out that even in societies with strong social welfare states and progressive redistribution policies, we still get to keep most of the fruits of our labor.

Instead, the point I’m trying to make is that the benefits of efficiency are a rather unusual feature of modern societies and that, at most points in time, we were probably like the “lazy” subsistence farmers who couldn’t see the point of being more efficient. If efficiency seems unnatural to us, it might be because, throughout our evolutionary history, working really hard to generate surplus wasn’t often a sound strategy.

Are You Lazy, Or Is It Your Workplace?Most environments we work in exist on a spectrum. At one end are the dead-end video rental jobs or tribal subsistence farmers where the idea of efficiency is alien and unrewarding. At another extreme are the scenarios where efficiency is obsessed over because any gains are personal rewards.

Work cultures exist on a spectrum too. I previously discussed an interesting description of Japanese office culture, which appears to prize working extreme hours at the office (with the result that employees are often terribly inefficient). On the other extreme are results-only work environments, where pay is exclusively based on performance (but that performance can be difficult to track and assess fairly).

I suspect that when productivity feels like a chore rather than an opportunity, it’s less because we’re intrinsically lazy and more because our environment makes us that way.

The post The Efficiency Mindset appeared first on Scott H Young.