Scott H. Young's Blog, page 18

September 19, 2022

Ten Mental Models for Learning

A mental model is a general idea that can be used to explain many different phenomena. Supply and demand in economics, natural selection in biology, recursion in computer science, or proof by induction in mathematics—these models are everywhere once you know to look for them.

Just as understanding supply and demand helps you reason about economics problems, understanding mental models of learning will make it easier to think about learning problems.

Unfortunately, learning is rarely taught as a class on its own—meaning most of these mental models are known only to specialists. In this essay, I’d like to share the ten that have influenced me the most, along with references to dig deeper in case you’d like to know more.

1. Problem solving is search.Herbert Simon and Allen Newell launched the study of problem solving with their landmark book, Human Problem Solving. In it, they argued that people solve problems by searching through a problem space.

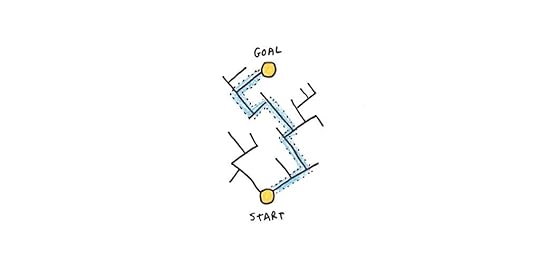

A problem space is like a maze: you know where you are now, you’d know if you’ve reached the exit, but you don’t know how to get there. Along the way, you’re constrained in your movements by the maze’s walls.

Problem spaces can also be abstract. Solving a Rubik’s cube, for instance, means moving through a large problem space of configurations—the scrambled cube is your start, the cube with each color segregated to a single side is the exit, and the twists and turns define the “walls” of the problem space.

Real-life problems are typically more expansive than mazes or Rubik’s cubes—the start state, end state and exact moves are often not clear-cut. But searching through the space of possibilities is still a good characterization of what people do when solving unfamiliar problems—meaning when they don’t yet have a method or memory that guides them directly to the answer.

One implication of this model is that, without prior knowledge, most problems are really difficult to solve. A Rubik’s cube has over forty-three quintillion configurations—a big space to search in if you aren’t clever about it. Learning is the process of acquiring patterns and methods to cut down on brute-force searching.

2. Memory strengthens by retrieval.Retrieving knowledge strengthens memory more than seeing something for a second time does. Testing knowledge isn’t just a way of measuring what you know—it actively improves your memory. In fact, testing is one of the best study techniques researchers have discovered.

Why is retrieval so helpful? One way to think of it is that the brain economizes effort by remembering only those things that are likely to prove useful. If you always have an answer at hand, there’s no need to encode it in memory. In contrast, the difficulty associated with retrieval is a strong signal that you need to remember.

Retrieval only works if there is something to retrieve. This is why we need books, teachers and classes. When memory fails, we fall back on problem-solving search which, depending on the size of the problem space, may fail utterly to give us a correct answer. However, once we’ve seen the answer, we’ll learn more by retrieving it than by repeatedly viewing it.

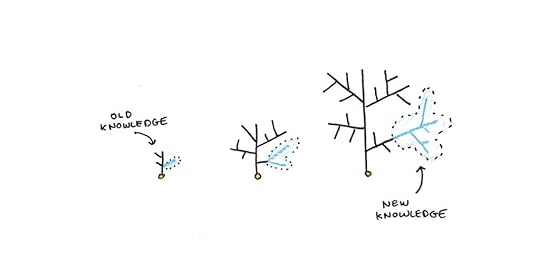

3. Knowledge grows exponentially.How much you’re able to learn depends on what you already know. Research finds that the amount of knowledge retained from a text depends on prior knowledge of the topic. This effect can even outweigh general intelligence in some situations.

As you learn new things, you integrate them into what you already know. This integration provides more hooks for you to recall that information later. However, when you know little about a topic, you have fewer hooks to put new information on. This makes the information easier to forget. Like a crystal growing from a seed, future learning is much easier once a foundation is established.

This process has limits, of course, or knowledge would accelerate indefinitely. Still, it’s good to keep in mind because the early phases of learning are often the hardest and can give a misleading impression of future difficulty within a field.

4. Creativity is mostly copying.Few subjects are so misunderstood as creativity. We tend to imbue creative individuals with a near-magical aura, but creativity is much more mundane in practice.

In an impressive review of significant inventions, Matt Ridley argues that innovation results from an evolutionary process. Rather than springing into the world fully-formed, new invention is essentially the random mutation of old ideas. When those ideas prove useful, they expand to fill a new niche.

Evidence for this view comes from the phenomenon of near-simultaneous innovations. Numerous times in history, multiple, unconnected people have developed the same innovation, which suggests that these inventions were somehow “nearby” in the space of possibilities right before their discovery.

Even in fine art, the importance of copying has been neglected. Yes, many revolutions in art were explicit rejections of past trends. But the revolutionaries themselves were, almost without exception, steeped in the tradition they rebelled against. Rebelling against any convention requires awareness of that convention.

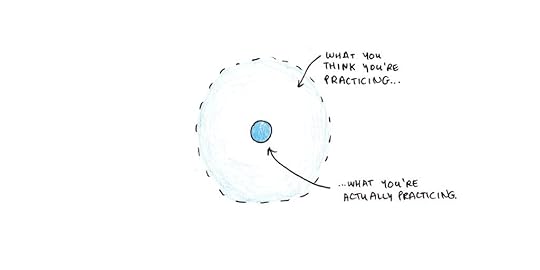

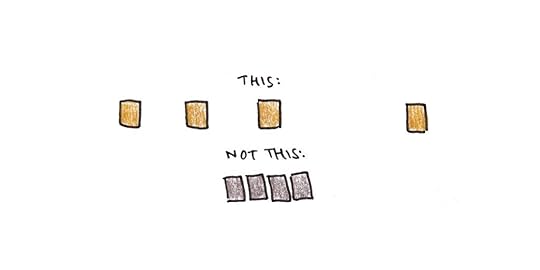

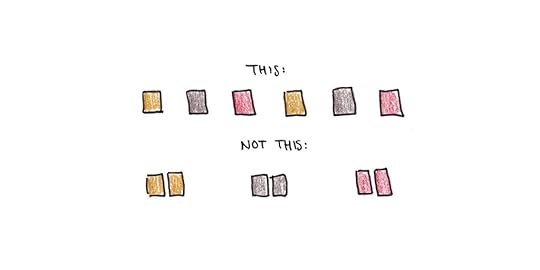

5. Skills are specific.Transfer refers to enhanced abilities in one task after practice or training in a different task. In research on transfer, a typical pattern shows up:

Practice at a task makes you better at it.Practice at a task helps with similar tasks (usually ones that overlap in procedures or knowledge).Practice at one task helps little with unrelated tasks, even if they seem to require the same broad abilities like “memory,” “critical thinking” or “intelligence.”

It’s hard to make exact predictions about transfer because they depend on knowing both exactly how the human mind works and the structure of all knowledge. However, in more restricted domains, John Anderson has found that productions—IF-THEN rules that operate on knowledge—form a fairly good match for the amount of transfer observed in intellectual skills.

While skills may be specific, breadth creates generality. For instance, learning a word in a foreign language is only helpful when using or hearing that word. But if you know many words, you can say a lot of different things.

Similarly, knowing one idea may matter little, but mastering many can give enormous power. Every extra year of education improves IQ by 1-5 points, in part because the breadth of knowledge taught in school overlaps with that needed in real life (and on intelligence tests).

If you want to be smarter, there are no shortcuts—you’ll have to learn a lot. But the converse is also true. Learning a lot makes you more intelligent than you might predict.

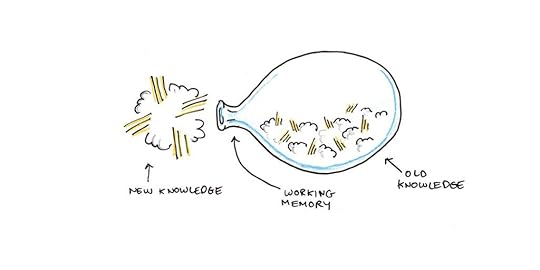

6. Mental bandwidth is extremely limited.We can only keep a few things in mind at any one time. George Miller initially pegged the number at seven, plus or minus two items. But more recent work has suggested the number is closer to four things.

This incredibly narrow space is the bottleneck through which all learning, every idea, memory and experience must flow if it is going to become a part of our long-term experience. Subliminal learning doesn’t work. If you aren’t paying attention, you’re not learning.

The primary way we can be more efficient with learning is to ensure the things that flow through the bottleneck are useful. Devoting bandwidth to irrelevant elements may slow us down.

Since the 1980s, cognitive load theory has been used to explain how interventions optimize (or limit) learning based on our limited mental bandwidth. This research finds:

Problem solving may be counterproductive for beginners. Novices do better when shown worked examples (solutions) instead.Materials should be designed to avoid needing to flip between pages or parts of a diagram to understand the material.Redundant information impedes learning.Complex ideas can be learned more easily when presented first in parts.7. Success is the best teacher.We learn more from success than failure. The reason is that problem spaces are typically large, and most solutions are wrong. Knowing what works cuts down the possibilities dramatically, whereas experiencing failure only tells you one specific strategy doesn’t work.

A good rule is to aim for a roughly 85% success rate when learning. You can do this by calibrating the difficulty of your practice (open vs. closed book, with vs. without a tutor, simple vs. complex problems) or by seeking extra training and assistance when falling below this threshold. If you succeed above this threshold, you’re probably not seeking hard enough problems—and are practicing routines instead of learning new skills.

8. We reason through examples.How people can think logically is an age-old puzzle. Since Kant, we’ve known that logic can’t be acquired from experience. Somehow, we must already know the rules of logic, or an illogical mind could never have invented them. But if that is so, why do we so often fail at the kinds of problems logicians invent?

In 1983, Philip Johnson-Laird proposed a solution: we reason by constructing a mental model of the situation.

To test a syllogism like “All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal,” we imagine a collection of men, all of whom are mortal, and imagine that Socrates is one of them. We deduce the syllogism is true through this examination.

Johnson-Laird suggested that this mental-model based reasoning also explains our logical deficits. We struggle most with logical statements that require us to examine multiple models. The more models that need constructing and reviewing, the more likely we will make mistakes.

Related research by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky shows that this example-based reasoning can lead us to mistake our fluency in recalling examples for the actual probability of an event or pattern. For instance, we might think more words fit the pattern K _ _ _ than _ _ K _ because it is easier to think of examples in the first category (e.g., KITE, KALE, KILL) than the second (e.g., TAKE, BIKE, NUKE).

Reasoning through examples has several implications:

Learning is often faster through examples than abstract descriptions.To learn a general pattern, we need many examples.We must watch out when making broad inferences based on a few examples. (Are you sure you’ve considered all the possible cases?)9. Knowledge becomes invisible with experience.Skills become increasingly automated through practice. This reduces our conscious awareness of the skill, making it require less of our precious working memory capacity to perform. Think of driving a car: at first, using the blinkers and the brakes was painfully deliberate. After years of driving, you barely think about it.

The increased automation of skills has drawbacks, however. One is that it becomes much harder to teach a skill to someone else. When knowledge becomes tacit, it becomes harder to make explicit how you make a decision. Experts frequently underestimate the importance of “basic” skills because, having long been automated, they don’t seem to factor much into their daily decision-making.

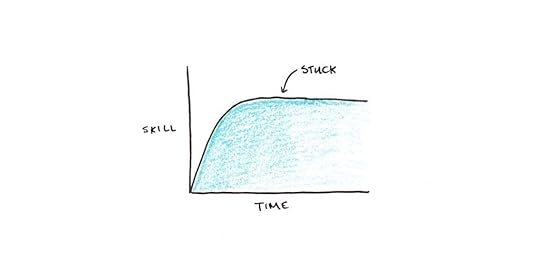

Another drawback is that automated skills are less open to conscious control. This can lead to plateaus in progress when you keep doing something the way you’ve always done it, even when that is no longer appropriate. Seeking more difficult challenges becomes vital because these bump you out of automaticity and force you to try better solutions.

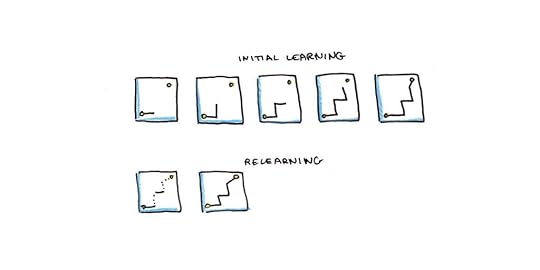

10. Relearning is relatively fast.After years spent in school, how many of us could still pass the final exams we needed to graduate? Faced with classroom questions, many adults sheepishly admit they recall little.

Forgetting is the unavoidable fate of any skill we don’t use regularly. Hermann Ebbinghaus found that knowledge tapers off at an exponential rate—most quickly at the beginning, slowing down as time elapses.

Yet there is a silver lining. Relearning is usually much faster than initial learning. Some of this can be understood as a threshold problem. Imagine memory strength ranges between 0 and 100. Under some threshold, say 35, a memory is inaccessible. Thus if a memory dropped from 36 to 34 in strength, you would forget what you had known. But even a little boost from relearning would repair the memory enough to recall it. In contrast a new memory (starting at zero) would require much more work.

Connectionist models, inspired by human neural networks, offer another argument for the potency of relearning. In these models, a computational neural network may take hundreds of iterations to reach the optimal point. And if you “jiggle” the connections in this network, it forgets the right answer and responds no better than if by chance. However, as with the threshold explanation above, the network relearns the optimal response much faster the second time.1

Relearning is a nuisance, especially since struggling with previously easy problems can be discouraging. Yet it’s no reason not to learn deeply and broadly—even forgotten knowledge can be revived much faster than starting from scratch.

What are the learning challenges you’re facing? Can you apply one of these mental models to see it in a new light? What would the implications be for tackling a skill or subject you find difficult? Share your thoughts in the comments!

The post Ten Mental Models for Learning appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 13, 2022

Brain Training Doesn’t Work

Will mastering chess make you more strategic? Does playing Sudoku speed up your mind? Do brain teasers help you think more logically?

Sadly the answer is: probably not.

From a 2016 review by Simons et al.:

“[W]e find extensive evidence that brain-training interventions improve performance on the trained tasks, less evidence that such interventions improve performance on closely related tasks, and little evidence that training enhances performance on distantly related tasks or that training improves everyday cognitive performance.”

Another study tracked participants over two years of working memory training. They found that the training had no impact on measured intelligence. The authors concluded, “These results question the utility and validity of [working memory] training as means of improving cognitive ability.”

Likewise, Giovanni Sala and Fernand Gobet performed a meta-analysis on whether studying chess and music affects academic or cognitive skills. They found only minimal effects. Some studies supported benefits from training, but the higher quality the study, the weaker the effect. Summarizing their review, the authors remark that, “this pattern of results casts serious doubt on the effectiveness of chess, music and working memory training.”

It’s easy to see why people are attracted to the idea of brain training. Intelligence is associated with nearly every positive life outcome people experience. A procedure that increases intelligence with only a small amount of daily effort would be life-altering.

Brain training also makes sense if you hold a false (but seductive) view of the mind—the idea that the mind is like a muscle.

The Mind-Muscle Myth

The Mind-Muscle MythThe idea that the mind is like a muscle has a long history. In his famous treatise on education, John Dewey linked the belief to the English philosopher John Locke. But it’s likely much older. The idea is so deeply interwoven in our folk psychology that few people even question it.

The mind-muscle metaphor goes something like this:

Muscles improve through training.Strengthening your biceps by lifting dumbbells, for instance, will make you stronger at lifting groceries, luggage or rocks.Mental abilities improve through training.Therefore, strengthening your mind through puzzles, for instance, will make you smarter in business, school and life.Items 1-3 are unproblematic. It’s #4 that gives the mind-muscle metaphor its appeal. It’s also where the analogy breaks down. Unfortunately, training on specific tasks doesn’t make you generally better at many different things.

The earliest takedown of the mind-muscle metaphor dates to Edward Thorndike. In 1901, he began a series of studies that showed practice on quite similar tasks didn’t lead to improvement in unrelated tasks. Thorndike interpreted his results in terms of identical elements: post training, performance improves on tasks that overlap in the stimulus or response required, but not beyond this.

Summarizing his view, Thorndike wrote, “the mind is so specialized that we alter human nature in small spots.”

Psychology has progressed considerably since Thorndike’s day. Yet the idea that skills are specific is a consistent finding in psychological research. In their 1989 monograph, The Transfer of Cognitive Skill, John Anderson and Mark Singley argued for what amounts to an updated version of Thorndike’s identical elements model. Skills transfer to the extent that the knowledge and procedures used between tasks are the same. If skills rely on different methods or ideas, training in one won’t help with another.

Thorndike’s identical elements model, and modern theories such as Anderson’s ACT-R, show why brain training doesn’t work. But are there any other ways to get smarter?

Does Education Boost Intelligence?Brain-training fails because it focuses on a very narrow kind of task. Judging a good chess position and good business decision don’t use the same procedure. Thus learning strategy in chess doesn’t make you more strategic or effective in business.

Education doesn’t necessarily suffer the same shortcoming because it aims to impart a much broader set of skills. Algebra might only be suitable for problems that use algebra, according to the identical elements model. But there are lots of problems you can solve with algebra! Similarly, learning to read may not transfer (directly) to other skills, but reading can be a gateway to acquiring knowledge in practically any field.

Stuart Ritchie reviewed studies on the impact of additional years of education. He found that an extra year of schooling was typically associated with 1-5 more IQ points. These studies often rely on a quasi-experimental design. The authors studied situations where a sudden, unexpected change in policy resulted in some people getting more education than others. Testing people just before and after the cutoff let them tease out the effect of education without a formal experiment.

The optimistic take on this research would be that education improves general thinking by equipping people with diverse cognitive tools. This breadth has power. Even if a particular task is only helped by a subset of school training, many years of schooling make an overlap between skills and tasks increasingly likely.

The pessimistic stance would be that education trains you at narrow tricks that work for passing tests—sitting still for a prolonged period, guessing well when you don’t know the answer, watching out for trick questions, etc.—and these tricks also help on IQ tests.

Applications for an Identical Elements View of LearningMy perspective is that the only way to become smarter is by learning. The basic units of learning are specific, but when added together, these specific chunks can become impressive proficiency.

A concrete analogy would be language learning. Fluency isn’t a muscle you improve. It results from knowing many words, grammar, and pronunciations and using that knowledge quickly and unhesitatingly. It can be impressive to watch someone at a mastery level converse in a language you struggle with. Still, there is nothing more to it than this—if you knew everything she did, you too would be fluent.

Similarly, intelligence in real life is about having the vocabulary of methods and knowledge to deal with a wide variety of problems. Each unit of learning may seem unimpressive on its own, but combine enough of those units, and the accumulation is wisdom.

But to achieve this possibility, we must let go of the false promise that broad-ranging skills can come from practice on narrow tasks. Brain training is a dead-end, but learning is timeless.

The post Brain Training Doesn’t Work appeared first on Scott H Young.

September 6, 2022

Failure is a Lousy Teacher

It’s a common opinion that we learn more from failure than success.

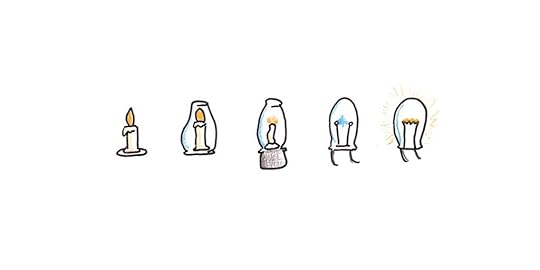

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible,” says Harvard Business Review. Learning from failure “fosters creativity” and helps you “become more resilient,” according to another essay. When Thomas Edison was asked if he was disappointed with his lack of results in finding a workable lightbulb filament, he replied, “I have gotten a lot of results! I know several thousand things that won’t work.”

Here, though, the feel-good opinion is wrong.

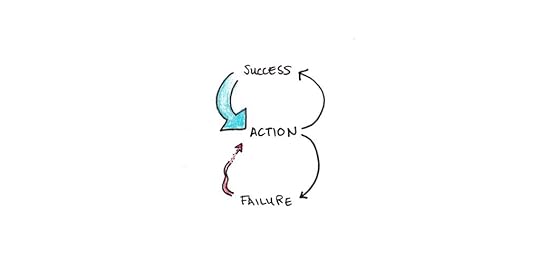

We generally don’t learn more from failure than success. In cases where there is value in mistakes, failure is followed quickly by success, rather than prolonged struggle. The reason is simple math.

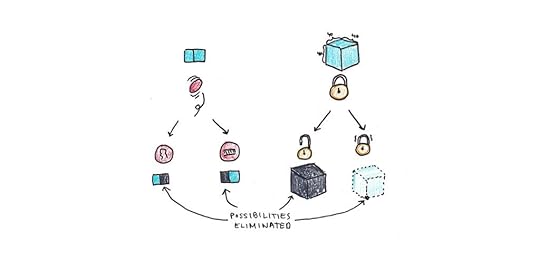

Success, Failure and Information TheoryThat we generally learn more from success than failure is evident from the principles of information theory.

Information theory was developed in the 1940s by mathematician Claude Shannon. The basic idea is that information is the reduction of uncertainty. Consider flipping a coin. Before I flip, there is an equal chance the outcome will be heads or tails. After the flip, I know only one of those results occurred—this halving of uncertainty results in one bit of information I didn’t have before.

The information gained from flipping a coin is symmetrical. Heads and tails are equally likely, so I learn the same amount from experiencing either event.

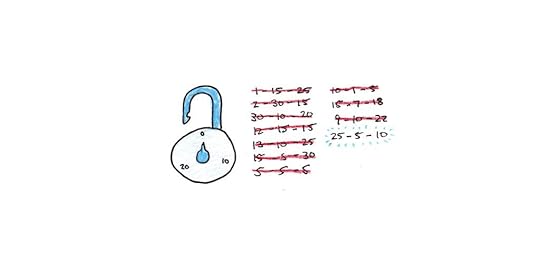

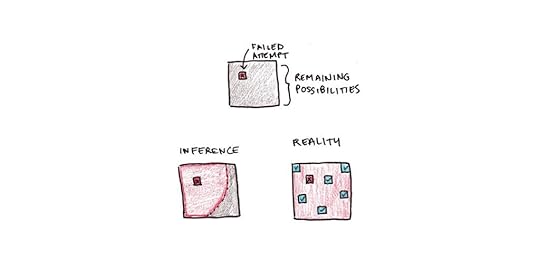

This doesn’t hold if one outcome is far more likely than another. If I try to open a 40-number combination lock with a random, 3-digit code, my chance of opening it is only one in 64,000. Failure here only reduces the space of possibilities by one—hardly any information at all. In contrast, if I had opened the lock successfully, I would have eliminated any remaining uncertainty.

In the combination-lock example, success teaches you far, far more than failure.

Running a business is like finding a combination that opens a lock. You need the right mixture of product, team, marketing, and customer needs to have a successful outcome. Failure is more likely than success—most products and businesses underperform or fail outright. Thus, you gain exponentially more information about what works when you find a hit than you do with a misfire.

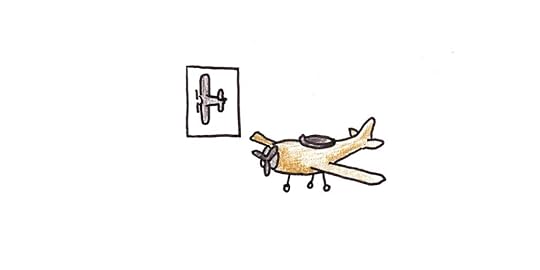

In contrast, failure can be highly instructive in some domains. Plane crashes happen rarely, so when one does occur, much potential information can be gleaned about the source of the disaster. Our knowledge of piloting is so advanced that successful takeoffs and landings don’t reduce uncertainty by much at all.

Of course, this doesn’t mean a pilot learns to fly by crashing a lot. When you start flying a plane, most settings of the controls would result in a crash if unfixed. It’s simply that, society as a whole benefits from thorough investigation of plane crashes because trained pilots rarely have such severe mistakes.

Most domains of learning are like the novice pilot, entrepreneur or combination-lock. There are far fewer conditions that enable success than those that allow for failure. Thus, learning what works imparts far more information than learning what doesn’t work.

Despite Edison’s optimism, his learning process would have ended immediately had he started with tungsten instead of trying out thousands of materials that ultimately didn’t work.

Studies on productive failure and learning from errors find benefits to making mistakes in learning—if those mistakes are promptly corrected. When a successful example or corrective feedback immediately follows every failure, the information difference between success and failure is eliminated.

Outside a classroom, failure is seldom followed by a lesson telling you exactly how you should have done it.

What About Emotions? Failure Discourages EffortPerhaps I’m being too coolly rational in my analysis here. Don’t emotions factor into learning as well? Isn’t failure a great teacher emotionally, even if it doesn’t provide informative lessons?

Here too, the boon of learning from failure is overstated.

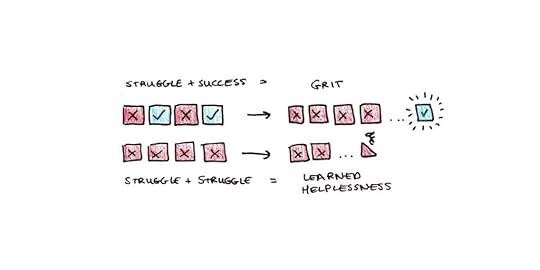

Failure is discouraging. Experiencing consistent failure lowers motivation. In extreme cases, it can lead to learned helplessness, and you stop trying even when success is plausible.

Success, in contrast, is motivating. It builds self-efficacy and confidence, which are related to greater motivation in learning. If you experience success in early mathematics, it boosts your confidence when attempting higher mathematics, so you’re more likely to persist when you experience setbacks.

What about grit and perseverance? They matter, but it’s important not to confuse the right way to process failures (persistence) with the idea that failure itself makes us better.

Grit comes from the belief that, despite current failures, success will be forthcoming. Where does such a belief come from? I’d argue that it comes from a background of confidence, either from your own past successes or from witnessing or learning from others’ successes.

The idea that failure is inherently character-building seems dubious to me. Repeated failure requires—but it doesn’t build—grit. It’s experiencing success after persisting through failure that reinforces perseverance.

Only taking on easy problems doesn’t impart grit. But neither does consistent failure on hard problems. It’s taking on challenging problems AND succeeding in them that matters.

Overlearning from FailuresMaybe you think I’ve missed the point.

The point isn’t that failure is inherently valuable—either emotionally or informationally—but that we can’t always control when we experience failure. Thus we should adopt a positive attitude towards it.

In this case, I agree. Failure and mistakes are often unavoidable. To the extent that we can have a healthy attitude, I think leaning toward perseverance is generally wise. (Although persisting in doomed projects is an underappreciated problem.)

However, there’s another danger of advice like this—we can easily overlearn from failures.

Many failures are like our combination-lock example: the specific thing we tried didn’t work. It would be disastrous to infer, after guessing 20-12-32, that the actual code couldn’t contain any of those numbers, any even numbers, or any middle-low-high sequence. Those “lessons” are overeager attempts to gain more information from the failure than is actually there.

Similarly, we can easily over-infer from our circumstances when we experience a business failure, a lousy relationship or a bad job. The actual reasons for our failure may be specific. Yet we extrapolate those to anything that resembles the original condition. A partner that cheated on you, for instance, might convince you that all partners are potentially unfaithful.

In many cases, the healthy attitude to failure is to move on. Keep a mental note of any patterns surrounding your failed exercise, but don’t expect definitive lessons about what works to emerge when success is relatively infrequent.

Planning for SuccessOverall, we learn more from success than failure. Success is both more informative and motivating. When struggle is helpful, it tends to be followed by success.

Of course, success isn’t something we can guarantee. Our ignorance about what makes something successful is what makes success informative in the first place.

Even so, we can take steps to build toward success:

Build successes in small increments. If you’ve never succeeded at a year-long project, try a month-long project. If your month-long efforts have fizzled, try a weekend. If you’ve never written a book, start with an essay. If you haven’t launched a company, try finding a single client.Pick challenges where success is likely, but not certain. The 85% rule for learning suggests we aim for roughly five successes (and one failure) out of every six attempts. The exact percentage is less critical than the suggestion that succeeding most of the time is our aim. If we’re failing much more than this, our expectations are out of whack, our projects are too difficult, or we haven’t gotten the training to do what we’re attempting.Learn the hard lessons from others first. When failure is likely, begin by learning as much as you can about what works by studying others’ success. The more you understand what the “success pattern” looks like for a particular endeavor, the less you’ll need to learn through trial and error.When you do fail, keep moving. Catastrophic, unexpected failures do offer lessons for introspection. But run-of-the-mill failures often don’t. Overinterpretting the lessons of failure can be just as bad as, or worse than, not learning anything from it. When failure is the status-quo, the best thing to do in the face of failure is to keep trying.Experiencing failure can build some valuable character traits: compassion, humility and gratitude. In this sense, failures are not wasted experiences. And when we do encounter them, it’s probably best to see them in a positive light.

But, we should avoid exaggerating this silver lining into believing that the best path to success is a string of failures, especially when we can choose an alternative route.

The post Failure is a Lousy Teacher appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 29, 2022

Top Performer Is Now Open

Top Performer is the course Cal Newport and I teach for helping you deeply understand what drives success in your career, and then gives you the strategy for getting really good at those skills. We hold sessions quite infrequently, and right now we’re opening registration for another one.

If you’d like to learn more about the course, how it works and whether it’s right for you, see the registration page here.

Everything you need to know about the course is in that link above, but here’s a quick summary of what we teach:

Research — We give you the tools to figure out how any career works and what skills you need to develop to reach the next level. This works for people early in their careers, still trying to figure out what they want to do. It also works for people who have already advanced in their careers and need to know what it will take to reach the next level.Practice — We break down methods for translating the important research in mastery of deliberate practice to knowledge work. In particular, we teach you how to set up effective projects that will allow you to quickly build new skills and master ones that matter for your career.Deep Work — Cal and I run through our productivity approaches with a focus on how you can maximize the amount of deep, important things you do every day.Mastery — How can you set up long-term career habits to continually push your career forward. This includes how to assess your career capital, set long-term goals and stay focused on the big picture instead of getting bogged down in the day-to-day difficulties.If you have any questions about the course, our team members will be happy to answer them here: support@scotthyoung.zendesk.com

Keep in mind, registration will be shutting down Sep 02, 2022 – Friday at midnight Pacific Time, so if you’d like to join, you’ll need to act before then.

The post Top Performer Is Now Open appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 27, 2022

What Work Matters?

This is the last lesson in a four-part series about career improvement. On Monday, Cal Newport and I will open a new session of our eight-week class, Top Performer. In case you missed them, here are the first, second and third lessons.

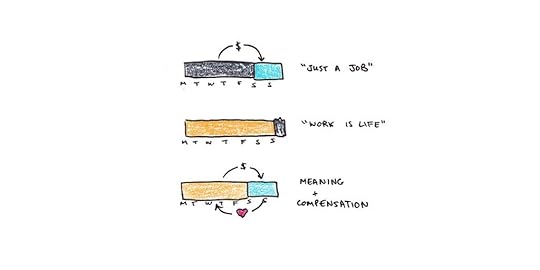

When it comes to work, there are a lot of different philosophies.

One is the “it’s just a job” school of thought. This viewpoint argues that work is just what you do to pay the bills, and your leisure time is what really counts.

A variation of this belief is the idea of early retirement. According to this view, work will always be drudgery, so you should try to get it over with as quickly as possible.

I don’t mean to be unfair to these viewpoints. A lot of jobs do suck. And financial independence, if you can pull it off, is certainly something to aspire to.

Yet, like it or not, work is a major part of our lives. Even if you can retire early, you’re still left with the question of what to do with those hours. A non-stop vacation sounds appealing—until you’re sitting around at 2pm on a Wednesday, all your friends are at work, and you’re left wondering what to do with your time.

Another philosophy is that work should be your “passion.” This camp argues that you should be obsessed with work and constantly driven to achieve your life’s purpose.

Although a few of us will find work so purpose-infused that we can devote our entire lives to it, this approach is unrealistic for many. Most of us will still want time for friends, family and the occasional vacation. We’d also prefer our work pays well enough that we’re not starving for the sake of chasing our passion.

My view of work seeks to moderate between these two extremes. Work is neither the sole purpose of life nor is it merely toil to be eliminated. Instead, the goal is balance. Work should be satisfying and meaningful. And work should pay well enough, and leave enough time, so that we can enjoy all the other things we value in life.

How Do You Find Meaningful Work that Pays Well?Listen to this article

How Do You Find Meaningful Work that Pays Well?Listen to this articleCareer satisfaction comes from finding work we can do well, for people we care about, in a setting where we have enough independence to make our own decisions.

There are many places where you can find this. It is a myth that we’re each born with a singular, inbuilt passion or purpose that we need to discover. Instead, building a successful career is primarily a matter of building up a collection of career capital that lets you do meaningful work and get paid for it.

Skills are the foundation of your career capital. If you have rare and valuable skills, you can start building a resume, portfolio of accomplishments, and network of allies who will champion your career.

Once you’ve built some career capital, you need to use it to negotiate the kind of lifestyle you want. Avoid the trap of spending it the way someone else wants you to, or failing to negotiate at all and accepting much less than you are worth. It can take courage and vision to avoid these pitfalls, but these negotiations are only possible if you have the career capital to begin with.

Building career capital, in turn, depends on understanding how skills work. The assumption that steady, uniform progress naturally accumulates with experience is wrong. Growth often spikes and stalls, depending on how much deliberate practice we extract from the environment. It depends on identifying which skills actually matter—and which don’t. Finally, it depends on consistently putting in the work of making progress rather than sporadic bursts that fizzle out before achieving anything of value.

Constructing a Vision for Your CareerBecoming a top performer doesn’t happen by accident. You need to construct a vision for what your career will look like, both in terms of the kind of job you’d like to have, as well as the career capital you’ll need to cultivate in order to get it.

For the last homework, write below about the kind of career you’d like to have, as well as the gap you see between what you’re doing now and where you’d like to be. There’s no shame in noticing the two aren’t the same, or that you have a long path ahead of you. In contrast, you may realize you’re closer than you think. Either way, developing this vision is an essential first step.

On Monday, Cal Newport and I will open Top Performer for a new session. If the ideas in these four lessons piqued your interest, consider joining the 5000+ professionals who have taken our eight-week course. Learn to stop spinning your wheels and work on the projects that help you build the career—and life—you dream of. With over fifty lessons, interactive worksheets, and a long-standing community, it’s a great place to make your vision into a reality.

The post What Work Matters? appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 25, 2022

Why People Stop Improving

This is the third lesson in Cal Newport and my week-long series on career improvement. Next week, we are opening our popular Top Performer course for a new session. Check out the first and second lesson here, in case you missed them.

The 10,000-hour rule, the idea that it takes about that long to get really good at anything, became popular after Malcolm Gladwell cited it in his 2008 bestseller, Outliers.

But does the research actually show that all we need is ten-thousand hours of practice to get really good? Not quite…

Anders Ericsson’s work on deliberate practice was the basis for Gladwell’s reporting on the 10,000-hour rule. Yet, Ericsson’s research doesn’t suggest that simply doing something a lot leads to reliable improvement. Instead, he found that stagnation—not progress—is typical and most people plateau far below their potential.

Violinists who went on to become concert players and those who became music teachers, for instance, did not differ significantly in the number of hours spent playing. However, the top performers spent far more time engaged in difficult, skill-pushing work, while the average players spent more time listening to music and playing songs.1

Similarly, research in medicine does not suggest that doctors get steadily better as they treat more patients. In fact, more experience might make doctors worse! They often become less effective as more time elapses since their medical school training.2

Ericsson found that the difference between growth and stagnation was a process he called deliberate practice. He defined this as practice under the guidance of a coach, along with immediate feedback about performance. Without this, performance stalls.

Coaching + Feedback = ImprovementListen to this article

Coaching + Feedback = ImprovementListen to this articleCoaching is often necessary because the performing and observing one’s own performance can rarely be done simultaneously.

In dynamic skills, like sports or surgery, self-observation competes for limited mental resources needed for performance—which is why we’re warned about overthinking. A coach acts as an outside observer to notice what we’re incapable of seeing.

Even in skills that permit reflection, like writing or mathematics, improvement depends on being pointed to the knowledge and methods you lack. By definition, these can’t be the things you already know, so a coach or tutor can step in to provide them for you.

Feedback is necessary because high performance depends on the subtle tuning of our skills. This tuning process requires reinforcement based on timely, accurate feedback from the environment.

How to Structure Your Improvement EnvironmentMaking improvements in your work is easier said than done. While it’s easy to picture coaching for a golf swing or a chess play, it’s harder to envision it for leading a team meeting or pitching a client.

Indeed, the difficulty of managing the day-to-day concerns of the work was one reason Anders Ericsson drew a sharp distinction between performance and practice. It’s impossible to focus on improvement and learning when your entire attention is devoted to doing the job.

Yet, there’s also a risk of focusing your improvement efforts on something completely detached from your work. Unless you’re certain you’ve isolated the exact skill that needs improving, it’s easy to work on things that are irrelevant to your career capital. You can spend hours memorizing syntax, even though that isn’t what makes programmers excellent. You can perfect your public speaking, even though being good at listening attentively is more useful for leadership.

How do you make progress?

In Top Performer, Cal Newport and I argue that the key is creating—and executing—a deliberate practice project. This project should push your skills. It should be on the edge of your comfort level, forcing you to raise the level of your craft or acquire a new ability. At the same time, it should be designed to ensure you can get quick feedback and guidance, so you’re not flailing around aimlessly.

Today’s HomeworkDesigning a good project takes some serious thinking—especially if it’s a project you’ll actually do, not just daydream about. The starting point to any good project is to generate some ideas.

In the comments, write down one activity you could do that would improve an important skill in your career.

In the last lesson, I’ll dig deep into why we should care about career improvement in the first place. If you are ready to invest in strategic projects that will help you level up in your career, Cal Newport and I are opening a new session of Top Performer on Monday.

The post Why People Stop Improving appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 23, 2022

How to Find Your Next Step

This is the second lesson in our week-long series on building a better career. Next week, Cal Newport and I are opening our course Top Performer for a new session. Here’s the first lesson, in case you missed it.

The first two weeks of Top Performer focus on how to do good research. This might seem like a funny place to start a career course: shouldn’t we be polishing our resumes or going to networking events?

We thought the same thing at first. Our earliest sessions of Top Performer skipped over this phase because we assumed most people already knew what they needed to improve.

Boy, were we wrong.

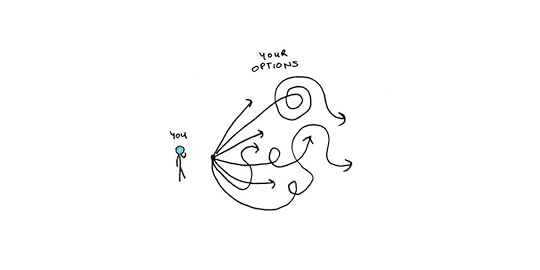

It turned out that the most people’s obstacles have nothing to do with how to design a project or practice efficiently. Instead, the most common struggle is not knowing what to get good at!

Struggles we saw came in three different types:

The first group either had no idea what they should be working on or had the unhelpfully broad “everything” in their list of skills to master or improve.The second group had a clear idea of what they wanted to improve—but it wasn’t closely related to career capital. For a skill to be valuable as career capital, it must enhance the value of your work in a way that the people who pay you can see. If a skill doesn’t do that, it isn’t career capital. Unfortunately, many early students focused on projects they found interesting, even when their contribution to career capital was questionable.The third group had no idea what kind of career they even wanted, so identifying a useful skill to improve was impossible.The Power of Doing Good ResearchKnowing how to do good research solves all three of these problems.

Research helps you parse out which skills have actually helped people advance on a career path you find interesting. Instead of misplacing your effort by learning skills that don’t contribute to your career capital, you can focus on mastering the skills that will make you a top performer in your job.

Research can even be a starting point to recognizing what kind of career you want in the first place. Most people who don’t know what they want to pursue haven’t encountered a compelling vision for what their career could be. The solution here is to find people with career capital similar to yours and see what kinds of careers they have—this can help you figure out which direction you prefer.

How to Do Good ResearchIf research is so important, how do you do it?

The simple answer is that you find people 2-3 steps ahead of you in their careers, and you sit them down and ask them what they did. Not what they think works. Not for advice. But what they actually did.

This process of asking questions helps you chart out their career trajectory. It doesn’t tell you which skills were directly responsible, but it helps you observe the pathway people have followed so you can find a way onto it yourself.

One interview alone doesn’t usually say much. But if you do three, five or a dozen, you start to notice patterns. Not only in the path people follow, but what they fixate on. Generally, the stuff top performers find obvious will be more valuable to you than the opinions they want to share from their soapbox. These “obvious” things are usually the most certain bets for replicating their success.

In Top Performer, we delve into how to do effective research, including detailed lessons on how to find people to interview, how to extract the most useful advice from them, and more. If you’re serious about your career, it’s worth the time to do it properly.

Today’s HomeworkBefore you can find someone to interview, it helps to identify your next step. What would a person 2-3 steps ahead of your current career position look like? Write down your answer in the comments and let us know.

A few tips on this:

It’s 2-3 steps, not twenty. A best-selling author is too far away if you haven’t yet published a single essay.The person should be in your career trajectory, broadly speaking. Picking someone who is generally famous or influential isn’t nearly as helpful as choosing someone who is a bit more advanced than you in your specific area.If you’re thinking of completely switching fields or aren’t sure where to work, look for people who have gotten a foothold into a career you’re interested in. Since first step would be getting a similar foothold, they will often give you more relevant advice than will those at the top.In the next lesson, I’ll talk about the science behind deliberate practice, why improvement typically stagnates for skills, and what you can do about it. If you want to learn how to engage with experts and discern what truly matters in your career, Cal Newport and I are opening Top Performer for a new session on Monday!

The post How to Find Your Next Step appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 21, 2022

The Key to Career Progress

This is the first of four lessons drawn from Cal Newport and my course, Top Performer. Next week, we are reopening the course to a new group of professionals who want to excel in their careers.

How do you find work you truly love? Not just work that pays well, but work that keeps your interest and is genuinely compelling?

The most common answer to this question revolves around choice. A great career comes from following your passion. That means sitting down, thinking about what you really love to do, and then finding the courage to chase your dreams.

The only problem is… most of us don’t have passions that neatly correspond to job titles. As Cal Newport argues in his book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, the innate passions people seldom lead to viable or compelling careers. You might have a passion for collecting stamps, but pursuing it full-time is hardly a reasonable career path.

A better way to think about this question is in terms of career capital.

Career capital is what you bring to the table for your clients, customers and employers. If you have something valuable to offer, you have more options for bargaining for something good in return.

Consider the careers of two different writers. One has best-selling books and is in demand as a speaker. Another has trouble getting freelance work published. Both are doing the same work, but the first author has more career capital. That means she not only makes more money, but she also has more leverage for other choices. She can be pickier about which projects she works on—and take more time off from writing too.

The importance of career capital holds true across professions. The programmer who is more productive can better negotiate promotions, vacation time or which projects they work on. The accountant with specialized expertise can bill more and take fewer clients. The designer with a popular portfolio can choose which projects to take on.

What is Career Capital?Listen to this article

What is Career Capital?Listen to this articleThere are different kinds of career capital:

CredentialsReputationContacts and friendsAssetsSkillsIn Top Performer, Cal Newport and I focus on rare and valuable skills as the primary ingredient in a successful career. This isn’t because having a good network, resume or assets is unimportant, but simply because those things tend to come more easily when you build on a base of valuable skills.

Consider our writer again. It’s hard to build a reputation, an audience or a deep network of media contacts if your writing isn’t outstanding. In contrast, if you’re an excellent writer, those other things will naturally accumulate as your career progresses.

Skills are a good starting point for building career capital because they are easier to bootstrap than the other options. You may not be able to find a powerful friend to boost your career if you don’t already have one. But you can always get better at the work you do—and use that to start building more powerful friends.

How Do I Build Rare and Valuable Skills?There are two steps to building valuable skills:

Figure out which skills are actually useful.Create structured opportunities to get good at them.We cover both these steps in detail in Top Performer.

You need to talk to people who have made the kinds of moves in their careers that you want to emulate. From that, you can work backward to figure out what skills are required to progress further on that path.

Sometimes the skill you need isn’t obvious. Many engineers think they must master increasingly esoteric programming languages to advance their careers. But in their research, they often discover that being really good at running team meetings is actually more important for promotions.

Just identifying a critical skill isn’t enough. To get good at that skill, you need to find the right opportunities to improve. Unfortunately, most people don’t get much better through experience alone. To make progress, we need to apply deliberate practice, a process of structured practice sessions combined with feedback.

Today’s HomeworkIn the comments below:

Write out one piece of valuable career capital you think you already possess. Share one thing you think you might need to move forward.While getting exact answers to these questions takes some work, this exercise helps you to start thinking about your skills and advancement in terms of career capital.

That’s it for today! In two days, I’ll share how to find the breakthrough projects that will move your career forward. If you are interested in building up your career capital, Top Performer opens for a new session on Monday.

The post The Key to Career Progress appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 19, 2022

I’m 34

Today is my birthday. For the last seventeen years, I’ve been sharing a birthday post with personal reflections, and I’ll continue the tradition today.

My wife and I did our part in contributing to inflation by buying a house this year. Timing-wise it could have been a little better. We made our offer right before the market fell—yet before we cashed out our investments for the downpayment. That, on top of the general ridiculousness of our local real-estate market, made the experience a little stressful.

That said, it feels nice to move into a place that we own. I’ve lived in small apartments in downtown Vancouver for over a decade. While it was fun while I was in my twenties, it started to feel a bit cramped with a growing family. On top of the extra space, it’s nice not to worry that we might need to move again in a few years.

Writing ChallengesThe past year was a difficult one for me creatively. Almost a year ago, I pitched a follow-up book to Ultralearning to my publisher. Shortly after, I found out the research I had wanted to use to support the book looked unreliable. This put me in an awkward position of having a book deal but not being entirely sure what to write.

Fortunately, my publisher graciously gave me an extra six months to organize an alternative. Still, the overall experience was frustrating as creating a book that’s true, useful, interesting and which I’m capable of writing can be quite tricky.

Nearly a year later, I have the beginnings of a book I’m happy with, but the writing is still challenging. I’m cautiously optimistic that I will be able to write a good follow-on book to Ultralearning, but it will still be a lot of work.

Reading Way Too Many BooksA positive side-effect of my writing headaches was that I ended up doing way more research. This is the fun part of writing a book.

I dug much deeper into foundational cognitive science than I would normally for an advice book. Foundational stuff tends to be both dense and somewhat removed from practice. At the same time, I’ve come to appreciate it as a tool for evaluating advice.

It’s hard to judge if an approach makes sense without having some theoretical underpinnings. This is especially true in an area like learning, where a lot of the empirical research is fairly poor, so you get mushy “everything works” research as well as biting “nothing works” rejoinders.

I did write three longer articles surveying ACT-R theory, cognitive load theory, and Construction-Integration. I also read a lot on situated learning, Direct Instruction, connectionism, constructivism, apprenticeship, and educational theory. I’m still far from an expert, but I feel like I understand the basic positions of the different camps, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of their arguments.

I always enjoy learning, so this part was fun, although it would have been a little less stressful if I hadn’t been doing most of it while also under a book deadline. In the future, I’ll be sure to separate exploratory and foundational learning from the targeted research I need to do to produce tangible output.

Evolving My Thinking About LearningGoing deeper into these foundational topics also shifted my beliefs about learning in a few different ways.

One major shift was recognizing the importance of having examples to learn from. I think I downplayed this a little too much in Ultralearning, as I mostly took it for granted that you’d be able to find examples. I had no trouble finding examples for the classes I took during the MIT Challenge. And finding word lists and grammar explanations for languages is easy. In both cases, it’s doing the actual practice that’s hard.

However, my deep dive into the research on cognitive load theory and direct instruction suggests that a lack of examples is actually a significant bottleneck to proficiency. People fail to learn complex skills like programming, painting or calculus because nobody breaks it down enough for them to get a foothold. Instead, they flop around trying to figure things out in a way that’s often inefficient and frustrating.

I’ve also updated my views on cognitive science. I started studying the subject when the deep learning craze was in full swing, so I tended to see older, symbol-processing approaches as an anachronism. Didn’t neuroscientists show that the people who thought the mind was like a serial computer were simply wrong? Isn’t learning just the result of complex neural networks, trained via backpropagation and reinforcement learning?

Going through the research, I now see that the two views are more complementary than I had previously realized. While at the low level, many computational neural processes resemble the kinds of machine learning algorithms used by Google and DeepMind, conscious thought is probably both serial and symbolic.

By symbolic, I don’t mean that the brain is literally moving little tokens that represent things around in the brain, but simply that we can learn patterns with variables in them. If I understand the pattern, “1 -> 1”, “2 -> 2”, and “3 -> 3”, I easily generalize that to “4 -> 4” or “2000 -> 2000”. This generalization requires the representation of knowledge to be more like “x -> x” than a simple memorization of fixed patterns.

So, the prior course of my thinking was closer to constructivism for education (skill learning is mostly doing, not reading or watching) and eliminative connectionism for cognition (learning is just neural weights, there’s nothing like rules or variables in the head). Now my views are closer to direct instruction (looping between examples and practice) and the vision of cognition espoused in theories like ACT-R.

Future PlansThe next several months will be a real push to finish my book on deadline. I could probably spend my whole life just reading books and thinking about them. Still, I’ve read enough in this area that I’m (hopefully) confident it’s time to assemble it into a book.

I’ll probably share more about the book as it gets closer. I haven’t yet landed on a title, but the core idea is related to the “see, do, feedback” posts I’ve written. I generally prefer books that are dense with ideas, and I expect the finished edition will try to explain what I’ve learned about how people get good at things in a way that complements my previous book, Ultralearning.

While I’m optimistic about the writing, I’m also aware it will probably be a bit stressful. Before becoming a father, I used to handle intensive projects by pouring on extra time. That’s now a lot costlier, so I need to be efficient—and clear-eyed about what things I can’t do—if I’m going to reach the finish line on time.

The past year definitely had more stresses than I would like, and it seems likely to repeat in the coming year. I’m not sure there’s a profound insight here; most of the stress is simply due to projects evolving in ways I didn’t expect when I committed to them. However, it may also be that I’m sticking to a success script that worked for me in my twenties when it needs some editing for the next phase of my life.

Despite these difficulties, I’m incredibly grateful. Being able to spend my time learning things and (hopefully) sharing them in a way that other people find useful and interesting is a profound privilege. At times, I feel a bit guilty for being stressed out, recognizing that I’ve already got my dream job. Of course, this is only possible because of readers like you. So thanks for listening to me for another year. Hopefully you’ve enjoyed the writing!

The post I’m 34 appeared first on Scott H Young.

August 2, 2022

Practice Made Perfect: The 10 Keys to Optimize Improvement

Getting good at anything requires a lot of practice–but not all practice is equal. Just doing something a lot doesn’t ensure you’ll master it.

Consider the person who hunts and pecks on the keyboard. Practice will help him go faster and make fewer mistakes, but no amount of pecking at the keyboard will turn him into a touch typer. Similarly, second language learners typically stall: their pronunciation and grammar often have noticeable errors, even when they have lived for decades in a country where they are immersed in the language.

Practice doesn’t make perfect, but permanent.

How can you optimize your rate of improvement? Considerable research has explored the mechanisms that underlie skill development. In this essay, I’d like to suggest a few strategies to improve your practice efforts.

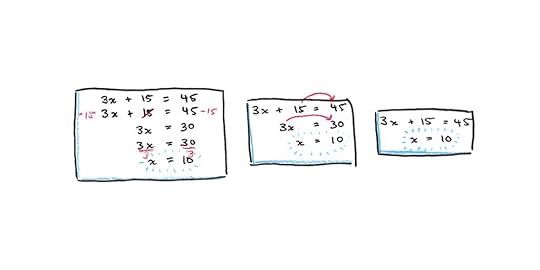

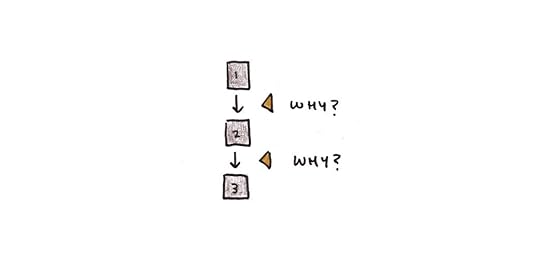

1. Start with ExamplesResearchers draw a distinction between practice and problem solving. Practice means using a known method or procedure. Problem solving refers to the process you use when you don’t know what the correct method is.

Problem solving has a few drawbacks. The most obvious is that you might not figure out the best method on your own. In that case, you may end up practicing a poor strategy and have difficulty correcting it later.

A subtler difficulty with problem solving is that it may distract you from learning the underlying patterns of the problem. Say you’re trying to solve a Rubik’s cube by twisting around the shapes randomly to try to get a pattern. In this case, even if you stumble upon a helpful technique, you might not notice it because your attention is directed entirely at completing the goal.1

One remedy for this problem is to start by studying worked examples or demonstrations of how to solve the problem. This can help you understand the best methods to solve a problem before trying it yourself.

2. Retrieve, Don’t RereadRetrieval practice is the process of testing yourself with a closed book. It lets you check your knowledge, and it is one of the most effective ways to learn.

Free recall is the simplest way to practice retrieval. After a lesson, give yourself a blank piece of paper and try to remember everything you can. When you finish, go back and see what you missed.

Flashcards are another way to practice retrieval. If a complex skill has hard-to-memorize parts, breaking those off as flashcards can ease your working memory burden.

Practice questions and mock tests can also be good resources for drilling down knowledge.

A tension exists between the benefits of retrieval and studying examples. If the pattern for solving a problem is in your memory, retrieval practice suggests you’re better off solving the problem on your own, without help. On the other hand, if the relevant pattern isn’t in your memory, you will have to default to search processes, which can be slow and make it harder to acquire the needed patterns.

You can resolve this problem by alternating between attempting a problem yourself and reviewing the solution. With more experience, shift your emphasis to problem solving and work on challenging problems for longer before checking the solution.

3. Spread Out Your SessionsCramming is bad. This isn’t because it doesn’t work—every student knows that a night of hard studying can make a difference right before a test. The peril is that what is crammed is soon forgotten.

The spacing effect refers to the benefit of spreading studying sessions out over time. The same fact, procedure or problem done five times takes the same amount of total studying time whether you do it in succession or spread out over five days. But the latter will result in much more durable memories.

For factual knowledge, spacing can be accomplished easily with flashcards. Spaced repetition systems make use of the spacing effect in timing when to review each card.

For other skills, the best way to benefit from spacing is to mix in practice of older skills while learning new ones. A ten minute review practice to work on previous material before moving onto new skills can make a huge difference.

4. Mix Up Your PracticeYour brain is a prediction machine. Behind the scenes, it is constantly trying to determine what knowledge might be useful. This is incredibly advantageous, but it can create problems for practice.

One such problem comes from blocking, i.e., when you practice the same skill repeatedly in predictable blocks. This happens when you do all the problems from Unit 1, followed by Unit 2, or when you drill your tennis backhand exclusively, followed by your forehand stroke. With such predictability, your brain learns to easily predict problems of a certain type and makes knowledge for solving them more available.

Yet, problems don’t come in neat packages divided by units in real life! This is why we need to mix up our practice. If we don’t know what type of problem we’re solving before we attempt it, we can only rely on the features of the problem itself. This alone makes our practice more closely approximate the real thing.

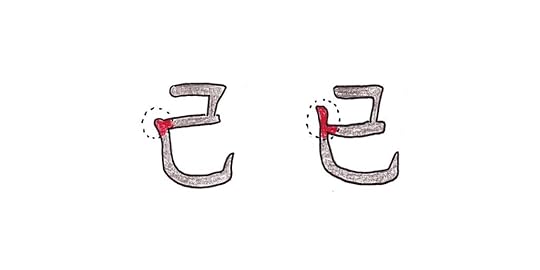

5. Put Confusing Examples Side-by-SideWhenever you make a mistake, it’s important to figure out why. One place mistakes are common is when very similar situations or cues require different responses. You might mix up the Chinese characters 己 and 已, confuse coronal for sagittal planes, or not be sure when you should code with a for-loop or a while-loop.

Any time you face this type of mix-up, put the examples side-by-side so you can see what distinguishes them. If you’re not sure, ask someone who knows so they can point you in the right direction. The worst thing to do is simply hope that the confusion will sort itself out through repetition.

6. Use Self-ExplanationsWhen learning a new method or problem-solving procedure, always walk through and explain each step to yourself. Repeated drills can help you memorize material but don’t always facilitate understanding. So when the format of the question changes slightly, you might not be able to adjust.

Effective practice is built on understanding. If you see a step that doesn’t seem well-motivated, try to explain it yourself. Failing that, seek out someone else to tell you why you need to do it that way.

7. Analyze Your Past PerformanceFor skills at the limits of your abilities, it’s impossible to monitor your performance and simultaneously improve it. The fix is to record yourself performing the skill and review it after.

Videotaping yourself while performing complex skills is a powerful tool for analysis. For skills like public speaking, martial arts or running a race, you can’t see yourself as an outsider would. This can lead to misperceptions about how you’re performing a skill. For instance, you might think you’re speaking slowly, but you’re actually talking too fast!

The other advantage of watching a recording of yourself is that you can focus all of your precious mental bandwidth on performing the task and only later analyze the effort.

8. Use the 85% Rule for Sliding DifficultyHow hard should you make your practice questions? The 85% Rule is an effective heuristic for choosing the difficulty of tasks that have a clear correct/incorrect distinction. If you can adjust the difficulty smoothly, you can fine-tune it to pick a level that’s not too hard or too easy. You are in the right ballpark when you are correct about 85% of the time.

Consider trying to listen to someone speaking in a foreign language to improve your ability to hear pronunciation. If you do drills with recorded sentences, you might want to pick questions where you hear correctly around 85% of the time. Less than that, and you’re likely making the task too difficult, thus making learning less efficient (and more frustrating).

For skills with lumpier difficulty gradients (such as physics problems) or where the metric for success is unclear (as with writing an essay), the 85% rule is more of a rough heuristic than a precise number. But you can still use the idea of fine-tuning difficulty so you’re succeeding most (but not all) of the time.

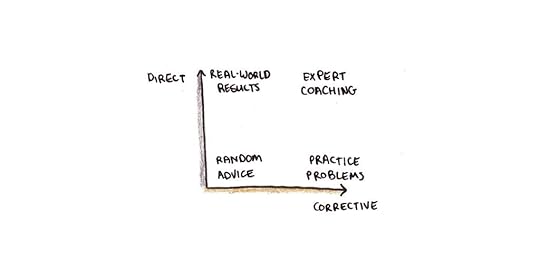

9. Improve Your FeedbackFeedback comes from different sources and has different qualities.

First, we can evaluate the source. Sources range from direct to indirect. Direct feedback is related to the result you’re trying to achieve—say sales for a product launch, bug-free code, or hitting a home run. You either achieve the result, or you don’t. Indirect feedback comes from other people and is a commentary on your performance rather than its outcomes.

In general, direct feedback is more accurate than indirect feedback, assuming you’re clear about what “reality” you’re trying to influence. If your goal is to be a better programmer to get a promotion, then writing code that pleases your boss may be the “real” feedback, not the speed or efficiency of your software.

However, direct feedback often isn’t constructive. It doesn’t tell you what you did right or wrong, and it can’t suggest methods for improvement. This is where indirect feedback can be more helpful.

Ideally, you should seek out both. Direct feedback gives you a valid measure of your success. Indirect feedback gives you tools and knowledge to make improvements.

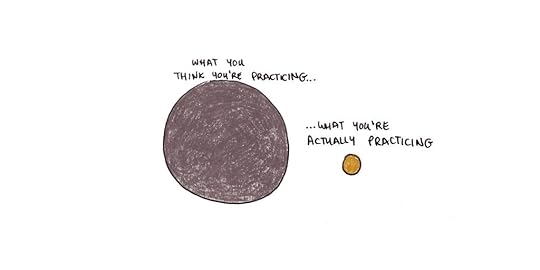

10. Match Your Practice to Real LifeNaively, we often view the mind like a muscle—give it training, and it improves. This is true, but our improvements are much more specific than the muscle analogy implies. Practice at one task transfers far less than we think to unrelated tasks.

If you want to improve your practice efforts, get really clear on what you’re trying to get good at. Are you learning a language to have conversations? Travel? Read literature? Watch movies? Some basics will overlap in each of these, but the exact skills needed will differ for each. Tons of practice ordering food at a restaurant won’t help much in reading a comic book.

Academic skills often have well-defined standards for achievement. Studying for a test can be measured fairly accurately against the tests you take in class. But real-life skills are often murkier. Is being a successful entrepreneur largely a matter of knowing business theory? Accounting? Finance? Marketing?

The more ambiguous the skill, the more critical it is to move back and forth between deliberate practice and doing the real thing. The former is often needed to make improvements, but the latter is essential for figuring out what approach is required in the first place.

What practice activities do you do to get better every day? Share your thoughts in the comments.

The post Practice Made Perfect: The 10 Keys to Optimize Improvement appeared first on Scott H Young.