Damian Shiels's Blog, page 34

October 13, 2015

Grieving for an Emigrant Son: The Story of the Finnertys of Galway City

This week I will be continuing my county-specific examinations of the Irish experience of the American Civil War, when I give a lecture in Galway City Museum on the impact of the conflict on the Tribesmen (and women!). I come across large numbers of Galway people in my research, and have little doubt that the American Civil War saw more Galwaymen in uniform than any other conflict in history. I decided to take a special look at one of these men and his family this week, particularly as they lived very close to where I will be speaking on Thursday. The letters this Galway soldier wrote home more than 150 years ago are transcribed below for the first time. The family story they reveal takes us from Galway to Liverpool, and via Canada and Illinois, before ultimately culminating in Vicksburg, Mississippi. It is a form of emigrant story now largely forgotten in Galway, but one that would have been familiar to many thousands of the county’s people in the 19th century.

Eyre Square, Galway City in 1903. This would have been an area the Finnertys knew well (Library of Congress)

Bridget Ridge and John Finnerty were married in the parish of St. Nicholas in Galway City on 14th January 1826. Their son, James, was baptised in the same place on 2nd July 1835. It is unclear how many siblings James had, but they included at least one sister. At some point over the years that followed the family decided their future lay away from the City of the Tribes. John Finnerty took them to England, where they would eventually set up home in Birkenhead. There they were surrounded by many other Irish emigrants, including at least some of Bridget’s Ridge family relations. James spent long enough in England to develop friendships, but in the 1850s the young Galwegian decided to strike out for North America. He may be the 19-year-old ‘James Feenerty’ recorded as arriving in New York from Liverpool aboard the De Witt Clinton on 19th November 1853. (1)

Whatever his date of arrival, by late 1858 James was in Grove Mills, Canada West (modern day Ontario). On 7th September that year he took the opportunity to write back to his parents and sister in Birkenhead, letting them know he was ok. Clearly not a regular writer, James admitted to his family that things were not going quite as he had hoped in his new home. He described how he had suffered from ‘the rumetism’ both that spring and the spring before, and that ‘times is very hard’, particularly due to the price of essentials. Still, if his health was spared he hoped to be able to go home for a visit, though he later wrote ‘I will send you my likeness in my next letter if I can, for I fear that I shall not see you.’ James’s family were obviously suffering from the sense of loss that remains familiar to many split by emigration, as he felt it necessary to tell those at home: ‘I am sorry to see that you are greaving for me…’ One wonders how many homes in Ireland and the United Kingdom had to make do with similar likenesses from America. (2)

It does not seem likely that James managed a visit home. Nearly four years after writing from Canada he was across the border in Chicago, Illinois. On 15th August 1862 he took the decision to enlist in the Union army, becoming a private in Company B of the 72nd Illinois Infantry, often called the ‘First Chicago Board of Trade Regiment.’ At the time James was recorded as a 26-years-old painter (he was 27), was some 5 feet 6 inches in height and had dark hair, grey eyes and a light complexion. It seems that James had been in the employ of English-born painter Francis Rigby in Chicago’s Second Ward (based on a review of the 1860 Census), but had decided he had better prospects in the army. The day before he joined-up he wrote this letter to his mother:

Chicago August 14th 1862

Dear Mother,

I hope you will excuse me for not writing before now as I have been moveing about for I have left Mr. Rigby thinking that I can better myself. I was very sorry to hear of my fathers death on the 18 of March last. How is Bridget getting along and likewise yourself, please write back as soon as you can and I will try and save you a little money.I dont know how things are going on with you in England but they are pretty hard here. I am glad to say I am in good health as stout as ever let me know [how] James Ridge and his mother and sisters are. I suppose you are living in the old place yet. Now dear mother be sure and answer this as soon as you can and send your directions so that my letter can find you. Give my love to Bridget and James Ridges family and receive the same yourself,

I remain your loving son,

James Finerty.

Patriotic letterhead on one of James Finnerty’s wartime letters (Fold3/National Archives)

James seems to have continued his habit of erratic correspondence, having not written home since hearing of the death of his father in Birkenhead a few months previously. This may at least be partially due to the fact that James appears to have been illiterate– the 1858 letter from Canada and the 1862 one from Chicago are in different hands. Despite saying that he was seeking to ‘better himself’ (a common theme in letters from men explaining their decision to enlist) it appears that he may not have told his mother that he intended to do this by becoming a soldier. (3)

By early September James was on the march to Kentucky. His regiment participated in a number of expeditions that October, before being ordered to Tennessee in November. James was at Holly Springs, Mississippi when he next wrote to England, this time to a Mrs. Bailey. In the letter James describes the fate of Cheshire native James Harrison, a 30-year-old who had also listed his pre-war profession as painter, and had enlisted on the same day as James. It seems probable the two had known each other (and perhaps worked together) prior to their service.

Holly Springs Nov the 30) 1862

Mrs Bailey,

This letter finds me in good health hopeing that yours is the same and im sorry to say that Harrison died on the 25 day of Oct he lay sick in the tent with Typhoid Fever 2 weeks till he got so sick that I could take care of him no longer and then he was sent to the hospital were he lay 3 days and I was with him when he died and stoped with him till we laid him out he was buryed next day. Me and Becker made up his accounts and sent the bill includeing the 50$ that he had in the Illinois Saving Bank that is all he had, it was all sent to Becker to be sent home to his father. While we were in Columbus our company was sent on an expedition down to Tennessee, your letter came when I was down there and I did not have time to answer it till now. We left Columbus a week ago Thursday for Lagrange, we left the latter place 3 days ago and we are now 8 or 10 miles south of Holly Spring Miss. Before we left Lagrange there were issued rations for 85000 men and that whole army is in motion, ready to meet the enemy and he is not far off, for they left Holly Springs the day before we got there. It would do you good to see the whole army in squad and companies before there camp fires at night for we have no tents with us, nothing but our blankets and the woods for shelter. It is a grand panorama to see and we enjoy ourselves first rate, a deal better than you would think we would I tell you. There is an awful sight of troops here in the west, the river is literally black with troops Roseincrans [Rosecrans] has a very large army so has Grant and we are with the latter in Quimby [Quinby’s] division. Our whole regiment is out on picket duty today and I think ther[e] is a battle going on about 10 miles from us judgeing from the cannonadeing that we hear and I do not know how soon we may [be] called into it also. I send my best respects to Eliza and the Duke and also to Dick and Dave also to Mr. Rigby and famly and also to sesesh Bill this is all I have to write at presant direct your letter to me,

Co B 72 Reg in Quimby Division by Cairo Ill

Yours truly,

James Finerty. (4)

Siege of Vicksburg by Kurz and Allison c. 1888 (Library of Congress)

As things transpired, the 72nd Illinois were not engaged in battle that November and eventually returned to the vicinity of Memphis, Tennessee. However, they were to be involved in Grant’s efforts to capture Vicksburg in the months that followed. It was as a part of that campaign that James’s regiment fought their first major engagement at Champion Hill, Mississippi on 16th May 1863. But there were bloodier times ahead. On 22nd May 1863 Ulysses S. Grant launched an assault all along the Rebel line at Vicksburg. The 72nd Illinois, as part of the Army of the Tennessee’s 2nd Brigade, 6th Division of the 17th Corps, were in the front ranks. On that fateful morning, the regiment’s Brigadier, General Thomas E.G. Ransom, moved his men forward at about 10am. Under the cover of sharpshooters, they had to scramble through ravines ‘filled with fallen timber and canebrakes’ as they struggled to make headway towards the Rebel entrenchments. Getting to within 60 yards of the works, Ransom massed the men for the final assault. But the Confederates were ready for them. The Yankee charge was met with a ‘continuous blaze of musketry’ poured into their ranks, while Rebel artillery, which enfiladed the line, ‘threw…shot and shell…with deadly effect.’ Although some of Ransom’s men managed to cling desperately to the Confederate works for a few minutes, they were unable to gain a foothold. Grant’s assault failed, and it proved costly to the Illinoisans. Ransom’s brigade lost 476 casualties, 100 of them from the 72nd. Among them was Galway’s James Finnerty. (5)

We don’t know how Bridget Finnerty discovered her son was dead. Perhaps she was sent a letter by one of James’s comrades or officers. Often such communications sought to soften the blow as to precisely how a loved one had died, attempting to downplay the horrors that modern war could inflict. Unfortunately, in Bridget’s case, we know that she discovered exactly how her son lost his life. Although she may have been comforted by the fact his end had come instantly, his fate must nevertheless have shaken her to the core. That she learned graphic detail of his fate is demonstrated in her pension file. Included within it is a newspaper clipping listing the casualties of the 72nd Illinois at Vicksburg. James’s name has been marked with ink where he is mentioned, twice. The second entry was included because of how he died– ‘literally blown in pieces by a shell.’ Though she would never see her son again, 50-year-old Bridget did receive a pension based on his service. From her home in 13 Elden Place, Birkenhead, she relied heavily on the U.S. Consul in Liverpool to help her secure it. The consul wrote to Washington to relate that Mrs. Finnerty was one of ‘many poor persons here who have lost sons or husbands in the war’, demonstrating just what a toll the American Civil War was having on British communities. He described Bridget as a ‘miserably poor widow’ who was among those who were too illiterate to write to the pension bureau herself, and too poor to get anyone to do it for them. Thankfully, and largely as a result of the Consul’s efforts, Bridget Finnerty’s dependent mother’s claim was approved. (6)

The newspaper clipping which Bridget Finnerty included in her pension application. The line which describes the horrible fate that befell her son was marked to prove he had died in battle (Fold3/National Archives)

* I have added minor formatting to these letters for the benefit of readers, but none of the content has been altered in any way. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) James Finnerty Dependent Mother’s File, New York Passenger Lists; (2) James Finnerty Dependent Mother’s File; (3) Illinois Muster Roll Database, James Finnerty Dependent Mother’s File; (4) Adjutant General 72nd Illinois History, Illinois Muster Roll Database, James Finnerty Dependent Mother’s File; (5) Official Records: 297-99; (6) James Finnerty Dependent Mother’s File;

References & Further Reading

James Finnerty Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC31621

Illinois Civil War Muster Roll Database

72nd Illinois Infantry Regiment History

New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Year: 1853; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 134; Line: 5; List Number: 1176

1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Year: 1860; Census Place: Chicago Ward 2, Cook, Illinois; Roll: M653_164; Page: 472; Image: 474; Family History Library Film: 803164

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 24, Part 2. Report of Brig. Gen. Thomas E.G. Ransom, U.S. Army, commanding Second Brigade, Sixth Division, including operations since April 26.

Vicksburg National Military Park

Civil War Trust Vicksburg Battle & Siege Page

Filed under: Battle of Vicksburg, Galway, Illinois Tagged: 72nd Illinois Infantry, Canadian Irish, Galway American Civil War, Galway Emigration, Illinois Irish, Irish American Civil War, Liverpool Irish, Siege of Vicksburg

October 9, 2015

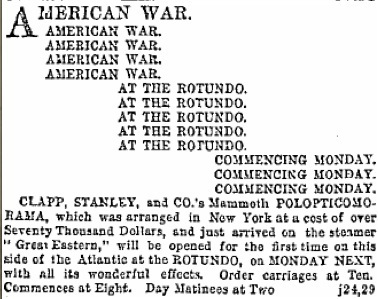

The ‘Polopticomorama’: Bringing the American Civil War to Life in Irish Theatres, 1863

When Mathew Brady exhibited his photographic images of the dead of the Battle of Antietam in New York in 1862, throngs went to see the exhibition. The shocking sight of the dead of the conflict caused the New York Times to remark that if Brady ‘has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.’ Brady’s exposition is by the far the most famous of the Civil War, but it was only one example of an entire industry that revolved around people’s fascination with the fighting. That industry was based on two simple premises– that those at home wanted to get a sense of what the war was really like, and that they were willing to pay for it. Although the photographs of the Civil War are the most enduring legacy of this enterprise, these early ‘immersive experiences’ came in a number of forms. This post relates research I have been carrying out into a remarkable traveling American Civil War experience that sought to bring an interpretation of the fighting to audiences of the Home Front. It is of interest to this site because its creators recognised that they could procure a global audience. In 1863, they crossed the Atlantic to tap into huge interest in the war in Ireland– thousands of people in Dublin, Cork and Limerick, flocked to be a part of it. (1)

Confederate dead in the Bloody Lane at Antietam (the position the Irish Brigade attacked). Exposed by Alexander Gardner, it was images such as this exhibited by Mathew Brady that caused such a sensation in 1862 New York (Library of Congress)

In the summer of 1863, Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s great steam ship the SS Great Eastern arrived in Ireland. Among the cargo unloaded from her hold were the components of a most unusual attraction, which would soon be wowing audiences up and down the island. The exhibition, which arrived ‘in charge of a couple of Yankees,’ boasted that prerequisite for a must-see show, an ‘unpronounceable name.’ It was also figured to be ‘of special and intense interest to Ireland’ due to its subject matter. The brainchild of Clapp, Stanley & Co. of New York, the exquisitely titled ‘Polopticomorama’ had an ambitious aim– to bring the sights and sounds of the ongoing American Civil War to an Irish audience. (2)

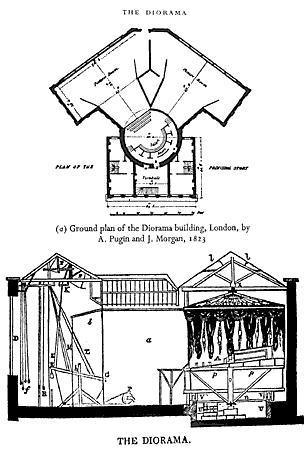

The foundations upon which Clapp, Stanley & Co.’s production drew were the moving panorama and the diorama. Intended to be immersive experiences, these forms of entertainment were hugely popular with 19th century audiences. The moving panoramas were giant painted scenes, designed to take viewers on virtual tours of famous locations, such as the Mississippi River. As the panorama moved forward, a narrator would describe the unfolding scene to the crowd. To get an idea of how these panoramas worked you can view a portion of the c. 1850 Panorama of the Monumental Grandeur of the Mississippi Valley (incidentally painted by Irish artist John J. Egan) on a video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art by clicking here. However, the central component of the Polopticomorama that visited Ireland in 1863 was the diorama. Invented in the 1820s by Louis Daugerre (himself a panorama painter and later inventor of the daguerreotype photography process), the diorama’s principal element were large pictures painted on both sides of a translucent material, onto which light was manipulated to create an illusion of three-dimensions, moving images and changing atmospheric conditions. These dioramas were displayed in specially constructed areas (one short-lived example was to be found on Great Brunswick Street, now Pearse Street, Dublin between 1826 and 1828) though by the 1860s they appear to have been more adaptable. But what seems to have been particularly special about Clapp and Stanley’s American Civil War Polopticomrama was the addition of layered elements, including the use of chemicals, to enhance this immersive experience. It certainly made a lasting impression on the show’s Irish audiences. (3)

The SS Great Eastern, which brought the Polopticomorama to Ireland (Memorial University Libraries)

The Polopticomorama seems to have started life in New York in 1863. The principal artist was Minard Lewis, who was originally from Maryland. Lewis had a long history of panorama painting, having worked with Massachusetts painter Truman C. Bartholomew during the 1850s on Revolutionary-War panoramas such as the Battle of Bunker Hill and the burning of Charleston. He had joined the California gold rush in 1849, and the sketches he produced would also later form part of a panorama based on that experience. Minard’s pre-war work also made it to Europe, where it appeared in the Cyclorama von Nordamerika which was displayed in Vienna. By 1860 he was living in New York, which is where he presumably struck up his association with Clapp, Stanley & Co. The Polopticomorama, which depending on reports cost between £20,000 sterling and $70,000 dollars to produce, was being displayed from at least early 1863 in locations such as New York, Pittsburgh, Trenton and Baltimore. Just prior to its unveiling in Ireland, the Dublin Freeman’s Journal shared an American account of the show to whet its readers appetite:

…language fails to describe the sensation produced upon the mind as one gazes upon these terrible battle scenes, where death and destruction fall on every hand, and remembers that it is our own friends and relations who are thus engaged in this deadly strife. And so life-like are the paintings, that one instinctively turns the ear to catch the sound of some familiar voice, and the eye hurriedly scans the features of the passing throng in the hope to recognise some well-known face. The illusion is made so perfect by the aid of mechanical effect, that nothing is left to imagination. The flash of powder and roar of the artillery are distinctly seen and heard as though the audience were on the actual field of battle. (4)

Plan of the Diorama Building, London, 1823 (Almanach des Spectacles, 1823)

The Polopticomorama aimed to show viewers the ‘horrors of the battlefield’ in ‘life-like vividness.’ They were to hear the thunder of the cannon, and see the fire and smoke of the opposing forces. In order to do this the showmen made use of ‘extensive and intricate machinery, mechanical appliances, chemical effects and ingenious dioramic accompaniments’ so that the audience could ‘almost imagine themselves actual spectators of the sublime and stirring scenes represented.’ As with the panoramas, a key feature of the Polopticomorama was a narrative lecture describing the key events. The Polopticomorama appears to have spent a brief period in England before arriving in Dublin in July 1863. American Civil War themed entertainment had the potential to be big business in Ireland. Although perhaps not something that is commonly recognised today, Ireland had an almost insatiable appetite for information on the war. As one newspaper reported, the Polopticomorama promised to be a success because ‘all Irishmen and Irishwomen are interested in this great contest, for even if they have not friends or relatives upon American soil, they must at least feel interested in the great cause of humanity involved in the issues of this tremendous contest.’ (5)

The first Irish venue for the Polopticomorama was the Concert Room of Dublin’s Rotundo. After the opening performance the Freeman’s Journal told Dubliners what they could expect:

The exhibition opens with a view of Washington, Georgetown, and Longbridge, the perfect authenticity of which, as well as all the other scenes represented, is vouched for by the proprietors of the work, which is on the most extensive scale of any similar exhibition ever produced here. The bombardment of Fort Sumter is a very vivid scene of scenic portraiture, and, indeed, the views throughout are depicted with considerable artistic skill, independently of their truthfulness as memorials of the great events which have such a deep and abiding interest for the civilzed world. The other pictures which attract particular attention are the battle of Bull’s Run, burning vessels in Gosport Navy Yard, riots in the city of Baltimore, bombardment of Port Royal, and the representation of the Battle of Antietam. The grand war tableau, with which the second section of the exhibition closes, is also highly interesting, from the fact of its containing a series of “life portraits” of the leading generals of the northern armies. The third section comprises a grand moving diorama of the battle in Hampton Roads, in which the celebrated Merrimac bears a conspicuous part. The different scenes are explained in an intelligent descriptive lecture. (6)

Advertisement for the Polopticomorama in the Daily Ohio Statesman, 11th July 1864 (Daily Ohio Statesman)

The Polopticomorama had a matinée and an evening performance, with advertisements helpfully telling perspective visitors what time they should order their carriages to take them home (the duration was in the region of two hours). Tickets for the show could be bought at establishments such as Bussell’s, Moses’s and Pigot’s. What is particularly striking about performances such as this is the ingenuity employed to attract as many customers as possible, and also to encourage repeat visits. Children were a particular target market. A special offer advertisement told how children would be entertained for as little as 3d, while the educational value of the experience was also highlighted. One report related that children who visited the Polopticomorama in Dublin were ‘made to understand their lessons more readily’ through the use of illustrated books. Indeed, aside altogether from the entertainment value, the writer felt that ‘more information about the American War can be obtained in a few hours at Messrs. Clapp and Stanley’s exhibition at the Rotundo than could be acquired from books in as many months.’ Such was the excitement surrounding the Polopticomorama that the Lord Lieutenant himself had a private viewing with his ADC and Assistant Private Secretary at the Rotundo on 15th August. Never ones to miss a promotional trick, from then on the show was advertised in the papers as ‘under the immediate patronage of His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant.’ The company was determined to keep the show fresh, and as such new scenes were consistently being painted to keep pace with events at the front. After a month on show at the Rotundo it was announced that the management were now in a position to present a new diorama, which had just arrived aboard the ship Persia, and which made the exhibition one-third larger. Indeed the speed with which they could follow with the major events of the war was remarkable– when touring Wisconsin in April 1864 the proprietors boasted that all the major incidents were included, ‘down to Kilpatrick’s Raid,’ a Union cavalry operation against Richmond that had occurred only a matter of weeks previously. (7)

George Howard, 7th Earl of Carlisle and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who visited the Polopticomorama in 1863 (National Portrait Gallery)

After a tremendously successful run in Dublin, the Polopticomorama readied itself for a move to Cork. In order to drum up some enthusiasm before opening night, coloured engravings of the war were ‘profusely scattered throughout the city.’ The first Cork performance was on the 24th August, with the venue the Theatre Royal on Georges Street (now Oliver Plunkett Street). Doors opened at 1.30 and 7.30, with admission prices ranging from 2s 6d, to 1s 6d, to 6d. As in Dublin, it was a huge success. The theatre was ‘crowded nightly’ with the audiences ‘perfectly carried away with enthusiasm.’ It was recommended that you go early if you entertained hopes of getting a seat. The journalists in Cork were just as impressed as their counterparts in the capital. A writer with the Cork Examiner related that ‘the main feature…is the introduction of flashes of light and puffs of smoke to represent the firing of cannon and the explosion of shells. This effect is introduced into several views of sieges and sea fights, in the Merrimac scene it shows the destruction of two Federal frigates, the contending vessels are made to move over the water while keeping up a vigorous fire at each other, and an almost perfect illusion is produced. The portrayal of the Hampton Roads fight was clearly impressive. One Cork writer remarked they had ‘seldom seen anything to equal this in its way for ingenuity and effectiveness. Ships move about, discharge guns, pour forth volumes of flame and smoke, and advance and retreat and manoeuvre, as if they were real vessels engaged in a real conflict.’ The Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier commented on the ‘masterly performance of some popular airs on the piano’ which added to the drama, concluding that the Polopticomorama was ‘a very unusual treat, well worth seeing, and none should be without seeing it.’ As in Dublin, promoters were keen to accentuate the educational value of the show. Nearly 2,000 children attended a special matinée juvinale performance on 1st September. Different techniques were used to keep people interested in attending; a military band was added to the show for the second last night of the Cork run, while prizes were often also given away to the crowd. Descriptions of some of these ‘valuable presents’ have left us the names of some of those who went to see the Polopticomorama. Mrs. Smith of Matthew Tower on the Lower Road won a ‘beautiful rosewood dressing case’, while Mrs. Bradbier of No.2, French’s Quay, came away with 112 lbs of flour. Catherine Leary of Blackrock got a reversible inlaid miniature pin, a Mr. Edge procured a ‘valuable locket’ and Mr. Burgess of the Citizen Steamers’ Company pocketed an emerald and opal brooch. (8)

The Rotundo in Dublin, which later formed part of the Ambassador (William Murphy)

The next venue on the Polopticomorama’s circuit was Limerick’s Theatre Royal, where it opened on the 7th September 1863. The plaudits kept coming– the Tipperary Vindicator called the show ‘the most splendid work of panoramic art that it has ever been our good fortune to witness.’ It is not clear when the performance left Ireland, but it looks to have stopped off in England once more before re-crossing the Atlantic. 1864 seems to find it touring locations such as Ohio, Wisconsin and Indiana. The Polopticomorama was clearly not unique during the Civil War; a review of contemporary newspapers uncovers many other similar shows, such as Josiah Perham’s ‘Mirror of the Rebellion’ which was to be found in Massachusetts in 1863 (this may also have been the original title of the Clapp & Stanley show) and the ‘Polopticomorama’ of Randolph, Carey & Co. which was touring Illinois in 1864 (it is unclear if this was an associated show, or was simply cashing in on the Clapp, Stanley & Co. success). (9)

Theatre Royal Cork in 1867 (Illustrated London News)

There is some evidence to suggest that not everybody in Ireland agreed with the particularly Federal slant with which the show presented the war. Despite being overwhelmingly positive in the main, the Freeman’s Journal did add that ‘some of the pictures are, perhaps, a little too highly coloured and taken from a Federal point of view.’ The most interesting postscript in this regard though is surely the legal action taken by one Mr. Harold Preston. Preston had filled in as the show’s narrator for a week during the Dublin run in the Rotundo, as the usual lecturer, Mr. Gardiner, had fallen ill. However, Gardiner subsequently refused to pay his substitute, stating that ‘Mr. Preston was incompetent to lecture on the scenes in the Polopticomorama, and often represented as Confederate victories battles which were won by the Federals.’ Whether Preston did this as a result of his own political leanings or through ignorance of the facts is unclear, but in any event the court found in his favour, and ordered he be paid the £2 10s owed to him.(10)

Despite the presence of similar shows in America, there was surely nothing to match the Polopticomorama in Ireland during the war years. Even if some had reservations about its Union-oriented focus, the crowds that swarmed to see the Polopticomrama were, as one Irish paper put it, marks of ‘the absorbing interest felt by all classes in the American war.’ The Polopticomorama presented a unique opportunity for Irish people to learn about the conflict even as the battles still raged. One wonders how many of the visitors attending had family members who were engaged in the deadly actions it depicted. For some it must surely have been an emotional experience. (11)

Advertisement for the Polopticomorama in the Freeman’s Journal (Freeman’s Journal)

(1) New York Times 20th October 1862; (2) Freeman’s Journal 25th July 1863, Cork Examiner 21st August 1863; (3) John J. Egan Panorama, The Diorama in Great Britain Part 1, The Diorama in Great Britain Part 2; (4) Palmquist & Kailbourn 2000: 369, Cork Examiner 19th August 1863, Pittsburgh Daily Post 6th April 1863, New York Herald 20th March 1863, Baltimore Sun 20th April 1863, Trenton State Gazette 24th April 1863, Freeman’s Journal 24th July 1863; (5) Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser 22nd July 1863, Baltimore Sun 20th April 1863, Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 29th August 1863; (6) The Freeman’s Journal 28th July 1863; (7) Freeman’s Journal 10th August 1863, Freeman’s Journal 1st August 1863, Freeman’s Journal 8th August 1863, Evening Freeman 15th August 1863, Freeman’s Journal 18th August 1863; Milwaukee Sentinel 11th April 1864; (8) Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 24th August 1863, Cork Examiner 19th August 1863, Cork Examiner 26th August 1863, Cork Examiner 29th August 1863, Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 25th August 1863, Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 2nd September 1863, Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 4th September 1863, Cork Examiner 28th August 1863, Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 29th August 1863; (9) Tipperary Vindicator 8th September 1863, Cheshire Observer 19th December 1863, Milwaukee Sentinel 11th April 1864, The Highland Weekly News 14th April 1864, Weekly Racine Advocate 27th April 1864, Fort Wayne Daily Gazette 23rd May 1864, Plain Dealer 10th June 1864, Daily Ohio Statesman 7th July 1864, Boston Herald 18th September 1863, New York Herald 30th March 1863, The Pantagraph 9th February 1864; (10) Freeman’s Journal 8th August 1863, Cork Examiner 9th September 1863; (11) Cork Examiner 28th August 1863;

References

Baltimore Sun

Boston Herald

Cheshire Observer

Cork Examiner

Daily Ohio Statesman

Evening Freeman

Fort Wayne Daily Gazette

Freeman’s Journal

Highland Weekly News

Milwaukee Sentinel

New York Herald

Pittsburgh Daily Post

Plain Dealer

Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier

The Pantagraph

Tipperary Vindicator

Trenton State Gazette

Weekly Racine Advocate

Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser

Peter E. Palmquist & Thomas R. Kailbourn 2000. Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary 1840- 1865.

R. Derek Wood. 1993. ‘The Diorama in Great Britain in the 1820s’ in History of Photography 17, 3, Autumn 1993, pp. 284-295. Online version accessed here.

John J. Eagan Panorama at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Filed under: Cork, Dublin, Limerick, Research Tagged: American Civil War Theatre, Dublin Rotundo, Irish American Civil War, Moving Panorama, Polopticomorama, Theatre in 1860s Ireland, Theatre Royal Cork, Theatre Royal Limerick

October 4, 2015

‘In This Song I Will Make Mention of the Sons of Erin’: Researching Irish Songs from the American Civil War

From early in the American Civil War songs began to emerge focusing on aspects of the Irish experience of the conflict. Many of these tunes remain familiar to us today, but beyond their often rousing lyrics, what were they originally intended to convey? To explore this further I am delighted to welcome a guest post from an expert in the area, friend of the site Catherine Bateson of the University of Edinburgh. Catherine is one of a number of scholars undertaking research into the Irish and other diasporas at Edinburgh; it is also the home of Professor Enda Delaney, author of the important paper Directions in Historiography: Our Island Story? Towards a Transnational History of Late Modern Ireland which has been referenced a number of times on this site, and is a must read for anyone interested in why subjects such as Irish involvement in the American Civil War are not major topics of study in Ireland.* Catherine is engaged in PhD research under the supervision of Professor Delaney, on the topic of American Civil War Songs and Irish American Sentiments. She has kindly agreed to share some of her initial findings with us– it may be that some readers have information that will assist Catherine in this important research.

You, Soldiers brave, pray pay attention: gentle folks, grand condescention,

While in this song I will make mention of the sons of Erin;

Whose brave behavior do excel what pen can write or tongue can tell

The Sixty-Ninth, you know well, are gallant sons of Erin. (1)

So begins The Gallant Sons of Erin, a ballad dedicated to the 69th New York Infantry. It is one of several 69th New York-related songs which comprise an ever-growing collection of song sheets written, produced and circulated by and about the Irish who fought in the American Civil War. The approximately 100 songs I have found and started researching form the foundation of my doctoral research at the University of Edinburgh, which focuses on the sentiments expressed in Irish-related songs from the Civil War and how these ballads, lyrics and the music used to sing them form part of an Irish cultural diaspora in mid-nineteenth century America. They reveal what the war meant to the Irish involved and the impact participation had on the relationship between Irish, American and, ultimately, Irish American identity in the 1860s.

The Gallant Sons of Erin (Library of Congress)

While interning with the British Library’s American collection to produce an online gallery exhibition about Britain and the American Civil War, I came across a beautiful songster scrapbook – a collection of song sheets printed during the Civil War that sing the story of the conflict. This included two dozen or so songs referring to Irish involvement in the war. I spent much time trying to work out the contradictory sentiments they expressed: lyrics were simultaneously pro-Union/nationalist and anti-secessionist, extolling Irish and American patriotism (by which I mean two distinctive identities, not ‘Irish-American’), and demonstrated a will to fight, even songs written in 1862/1863 when the war sacrifice of Irishmen started to have an impact within military and civilian circles.

My doctoral study focuses on two areas articulated in these Irish American Civil War songs. The first part examines the opinions and feelings songs expressed. By looking at the subject matters, songwriters, and the performers who wrote lyrics and sang them, a clearer picture of wartime sentiment articulation can be created and added to contemporary Irish and Irish American accounts and memoirs. So far, I’ve determined there are three main sentiments these songs extoll, with a myriad of other views and attitudes developed from these core sentimental roots. They are:

Songs praising the bravery of the Irish and their service in battle

These make up the bulk of songs I’ve found in archives, which has meant I’ve become well versed in the more military aspects of the conflict! (2) Many relate to the Irish Brigade and the 69th New York Infantry Regiment in particular, such as The Boys of the Irish Brigade and New War Song of the 69th Regiment, written in honour of the 69th New York’s role during the First Battle of Bull Run. Most of the songs I’ve come across recount Irish Union Army service, which is to be expected given the statistical dominance of the Irish in the north east/New York City fighting for the Union. (3)

Songs with lyrics extolling the military service of Irish officers

Closely related to the theme above, many lyrics and songs are dedications to the Union Army’s most well-known Irish generals – Michael Corcoran and Thomas Francis Meagher. Corcoran regularly received his own titled song dedications, for example Return of General Corcoran of the Glorious 69th and Corcoran’s Ball!;

Meagher makes an appearance in the Battle of Bull-Run as the Captain…[with] Irish blood of fame, Who wore the Harp and Shamrock upon the Battle-plain.(4)

Songs about the conflict from soldiers’ point of view

For example, the haunting ballad Pat Murphy of Meagher’s Brigade describes the eponymous Pat – a dashing young blade – waiting on the night before battle…With his pipe in his mouth…And a song he was lilting quite gaily…he sang of the Sprig of Shillaly.(5)

Pat Murphy of Meagher’s Brigade (The British Library)

Aside from the military aspects songs expressed, lyrics also sang of home-front concerns – the perennial No Irish Need Apply motif forms the subtext of several verses, alongside continual anti-nativist rebuttals, though these are few and far between. Most lyrics extoll the continuance of Wild Geese spirit and the legacy of our famed Fathers on the plains of Waterloo. (6) There’s also a fairly strong presence of Irish nationalist sentiment, though it’s too early in my research to say how closely connected this is to the development of Fenianism in 1860s America, and an apparent deep love and patriotism for America, be that Union and the Confederate States. My most recent focus for instance has been on the constant repetition and lyrical connections between the symbolism of the Stars and Stripes in Civil War Irish songs and the green banners of Erin carried by many Irish-connected regiments. As one Irish Brigade ballad articulated: Now Erin’s Green flag is blended Along with the Red, White and Blue. (7)

The Irish Brigade (The British Library)

Such sentiments connect to the second part of my doctoral research: how Irish Civil War songs and the music their lyrics were often set to reveal the maintenance of an Irish cultural diaspora in mid-nineteenth century American culture. In essence, I’m trying to establish two histories: the first of the songs themselves, ie. the lyrics sung, and the second being the history of Irish music dissemination in America, ie. the tunes. This is not just ethnic-Irish related. Several of the songs I look at are set to Scottish, Scots-Irish and American (English) tunes, so I also evaluate the way in with Irish music became American in much the same way Irish soldiers were said to become Americanized during the war. (8) This side of my research extends beyond songs pertaining to the Irish experience. One of the main sources I’ve been focusing on is the Confederate rallying song The Bonnie Blue Flag – a (Confederate) American song, written by a songwriter of Scots-Irish descent, Harry Macarthy, and set to the tune of the Irish ballad The Irish Jaunting Car. The song spread around America, North and South, carrying with in an Irish tune that would have been identified as American. Trying to determine why Macarthy, with his own intriguing ethnic-Irish connections to this song, used The Irish Jaunting Car tune for his Bonnie Blue Flag provides an example of the research I’m conducting into the authors of many of these musical pieces connected to the Irish in the war.

Tying the two strands of my research together is the dissemination of these songs throughout Irish and American military and civilian communities. Letters such as Patrick Kelly’s, which Damian has displayed on this site, provide excellent examples of the way in which soldiers communicated musical practices and sharing with the home-front. (9) Such examples, amidst the thousands of pages of correspondence and memoirs, are not that common: music and song singing was so universal in the nineteenth century that, ironically for such a noisy topic, it does not appear regularly in primary sources. Michael Corcoran’s memoir and letters have become personal favourites, as he writes about the daily activity of song composition while in Confederate captivity. (10) The task of finding soldiers and civilians talking about this subject is almost beyond the scope of my studies (for now). Thus I’d like to gather all the readers of this blog site and those interested in the role of the Irish in the American Civil War to keep their eyes peeled for any music/song references in primary sources, be they Irish-related or from others speaking about Irish culture. I have more than enough songs to be occupying my research needs at present, but any sources like Kelly’s would be gratefully received if passed on.

Hopefully I’ll be able to update you all soon with more of my research findings and arguments! You can follow the progress of this via my Twitter – from time to time I quote some of the best and most amusing lyrics I find, as well as lines relating to certain key anniversaries of Irish military involvement in the conflict. If anything, my research is already recalling a forgotten voice and unique articulation of sentiments about immigration, nationhood, patriotism and identity that has been unheard for one hundred and fifty years, revealing that the whole scope of the Irish experience of the American Civil War can be read and heard in these songs.

*For those interested in reading Professor Delaney’s paper, you can find it in Irish Historical Studies 148, November 2011.

(1) A mini-dissertation spoiler: every lyric I’ve come across strongly supports the suggestion this process of ‘becoming American’ was happening during the war. The songs are an intriguing way in which this was articulated – but I’ll save that for another blog post further along in my research.

(2) On this issue I’m also looking at how Welsh, Scottish and German soldiers in the Civil War engaged with this practice and cultivated their own ethnic music cultural diasporas during the conflict in comparison to the Irish.

(3) The Captivity of General Corcoran, p. 30.

(4) Glorious 69th, British Library, http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/uscivilwar/highlights/songsters/glorious69th.html.

(5) The Irish Brigade, British Library, http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/uscivilwar/highlights/songsters/theirishbrigade.html.

(6) Being a cultural/social historian of the American Civil War before I started by PhD meant I used to gloss over regimental structures and numbers and battle details – I’m happy to say I’ve quickly learned they actually do matter!

(7) I must add the small qualification here that I haven’t really begun researching the Irish in the Confederacy in much detail yet – that’s my priority for the next stage of my PhD research.

(8) Battle of Bull-Run – dedicated to the 69th Regiment, N.Y.S.M., R.L. Wright Irish Emigrant Ballads and Songs (1975), p. 447.

(9) Pat Murphy of Meagher’s Brigade, published by Horace Partridge, Boston, British Library, http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/uscivilwar/highlights/songsters/patmurphyofmeaghers.html. The song has several title variations, including Pat Murphy of the Irish Brigade.

(10) The Gallant Sons of Erin, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/item/amss003406/. The song sheet used to quote from this song actually dedicates the ballad to the 69th New York State Militia, but the lyrics and stories the verses sing relate to the infantry regiment.

Filed under: 69th New York, Guest Post, Research Tagged: 69th New York Songs, Bonnie Blue Flag, Catherine Bateson, Irish American Civil War, Irish Music of the Civil War, The Gallant Sons of Erin, The Irish Brigade, University of Edinburgh

October 1, 2015

Recruited Straight Off The Boat? On The Trail of Emigrant Soldiers From the Ship Great Western

The medical images of Civil War soldiers taken towards the end of the war are undeniably compelling. Friend of the site Brendan Hamilton has previously explored the story of one of these men in a guest post, which you can read here. It was while researching another wounded Irishman that Brendan uncovered an extraordinary link between him and a number of other emigrant Union soldiers who all shared something in common– they had arrived in New York on the same day, in the same ship. This prompted him to carry out extensive research into these men and their fate, which Brendan shares with us in detail below. In addition to this, I was able to uncover some details as to the men’s origins and emigration. What emerges is a remarkable story which takes us from the manufacturing centres of Northern England to New York, via the Liverpool docks, on the trail of potential illegal recruitment into the Federal army.

The medical image taken of Robert Jenkins after his wounding in 1865, only months after arriving in America (National Museum of Health & Medicine)

The image above is 19-year-old Private Robert Jenkins of Company E, 64th New York Volunteer Infantry. Private Jenkins was wounded in the face at the Battle of Jones’ Farm, during the Petersburg Campaign of the American Civil War. The description that accompanies this remarkable photograph from the National Museum of Health and Medicine notes that the ball entered Robert’s face to the left of his nose, exiting through his cheek.* Robert Jenkins was an Irish immigrant who enlisted in the U.S. Army on 14th January, 1865, relatively late in the war. At Jones’ Farm, his regiment was sent to provide support to the 69th New York and the 28th Massachusetts of the famous Irish Brigade. The latter two units had run out of ammunition and required the 64th to hold their position while they awaited resupply. Jenkins received this wound while helping fellow Irishmen in combat on foreign soil, soil that he himself had only set foot on less than three months prior. (1)

In fact, Jenkins enlisted on the very same day he stepped off the docks in New York City. In researching this man’s past, I stumbled over something quite amazing— a ship manifest revealing that at least 33 European men traveled together to the United States from the port of Liverpool and immediately enlisted in the Union Army. Below is a spreadsheet of recruits who enlisted in the 64th New York Infantry, 10th New York Cavalry, and several other units on or soon after 14th January, 1865. The information is from their muster roll abstracts. All are recorded as having enlisted either in New York City or Brooklyn, and all appear to match men who arrived in New York on the Great Western on that very same day. All of these men but one (Bartholomew Early) appear on the last two pages of the manifest (a portion of which is reproduced below), listed with other men of military age. They appear to have been deliberately recorded in a separate section of the manifest, even though they were not all quartered on the same part of the ship. According to the muster rolls, thirteen were natives of Ireland, ten from England, four from Germany, three from France, one from Scotland, and one from Wales. (2)

Name

Age

Birthplace

Occupation

Unit

Enlisted

Fate

Bornholtz (or Barnholtz), Herman

18

Germany

Painter

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Brown, Joseph

23

England

Wood turner

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Bruce, Andrew

30

Scotland

Laborer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Brian (or O’Brian), Thomas

30

Ireland

Laborer

Co. H

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Davis, James

26

Wales

Laborer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Fries, Carl (or Friez, Charles)

32

Germany

Soldier

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Jordan, Patrick

21

Ireland

Laborer

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Hawkins, James

21

England

Servant

Co. B

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Hastings, Patrick

20

Limerick, Ireland

Miller

Co. E

14-Jan

Wounded, 25 March, Discharged

Hoben, John

21

Ireland

Baker

Co. H

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Holloway, Harry

27

England

Galvanizer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Jenkins, Robert

19

Ireland

Tailor

Co. E

14-Jan

Wounded, 25 March, Discharged

Jones, George

23

London, England

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Kanarens (or Canarns), Alfred

23

England

Laborer

Co. G

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Kirker, William

18

Ireland

Moulder

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Mackin, John

25

Ireland

Bricklayer

Co. H

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Mayhew, Harvey

20

London, England

Gunmaker

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Muller, Conrad

24

Germany

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Salter, William

22

Germany

Clerk

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Scott, Walter

22

Ireland

Clerk

Co. G

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Smith, John

27

Ireland

Servant

Co. A

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Watters (or Waters), Thomas

29

England

Servant

Co. A

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Wells, John

24

England

Laborer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Winter (or Winters), John

32

England

Engineer

Co. A

14-Jan

Died 31 January near Petersburg

Wood, James

35

England

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Wood, Harvey (or Henry)

20

Ireland

Baker

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Bulens (or Bulins), Joseph

28

France

Laborer

10 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Transferred 1 NY Prov. Cav.

Ismael, Bizen

20

France

Baker

10 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Transferred 1 NY Prov. Cav.

Ward, James

30

Ireland

Laborer

10 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Transferred 1 NY Prov. Cav. (Awaiting trial)

Early, Bartholomew

18

Ireland

48 NY Inf.

19-Jan

Deserted 6 August

Hickey, Michael

30

Ireland

48 NY Inf.

19-Jan

Wounded, 21 February, Wilmington

Morgan, John

34

6 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Deserted 24 May

Gerard, Prosper J

23

Reims, France

14 US Inf.

23-Jan

Unknown

Table 1. Union soldiers traced to the Great Western.

What is the story behind these men’s service? To uncover this we must first look at the main drivers in the Union recruitment system by January 1865. The enrollment act of 3rd March, 1863, which instituted a policy of conscription into the Union Army, allowed draftees to be exempt if they either paid $300 or provided a substitute to serve in their stead. As a result, prospective substitutes were often offered hundreds of dollars to join the Union Army. Private substitute brokers sprung up in major Northern cities, facilitating such recruitment and raking in profit on commissions. In addition to the money to be made by signing up as a substitute, bounties, a form of signing bonus, were also offered to further encourage new recruits. These could be as high as $1,500. The value of these bounties was often dictated by the need of a particular area to provide sufficient numbers of volunteers to reach their volunteer quota and thus stave off the draft. Clearly, the need for new recruits was severe, and European immigrants offered an attractive solution. We know that the Federal government rarely if ever– as is depicted in the film Gangs of New York and discussed here– engaged in direct dockside recruitment. The notion of directly recruiting recently arrived immigrants at Castle Garden was debated but (at least publicly) rejected by the New York Commissioners of Emigration in July of 1864. However, potential new recruits did not have to travel far if they wanted to enlist. Added to that, substitute brokers and other agents seeking to make money out of potential enlistees operated in close proximity to the port of arrival. In 1865 the New York Times reported on the ‘swarm of bounty swindlers who infest our public-thoroughfares.’ New York based British diplomat Joseph Burnley spoke of the ‘rascalities and swindling practices of the bounty brokers…the distance from the Emigration Depot to this office is about 400 yards, and the number of recruiting and enlisting rooms and booths within that distance is about 7 or 8, with printed notices in both German and English. In the neighbourhood of these booths and rooms brokers and runners swarm; and the unhappy emigrants who land here are necessarily obliged to run the gauntlet of these mantraps and harpies.’ Is it possible that the Great Western immigrants, including Robert Jenkins, were assailed shortly after their arrival in New York, ultimately induced to enlist en-masse by one of these brokers? (3)

Bounty brokers on the look out for substitutes (Library of Congress)

To discover the origin of Robert Jenkins and the other men’s enlistment we must return to Liverpool in 1864. It was there on 15th November that some 200 men arrived in the port to board the Great Western as steerage passengers. The majority, reportedly ‘destitute and half-starved’, had come from different manufacturing districts of Lancashire and were joined by some Irish and Germans at the quayside. However, as was the case in Irish port cities, Confederate agents were ever watchful of such groups. These agents soon discovered that the men’s passage to New York had been paid by an American, reportedly with a view to having them work in a New York glass works owned by Messrs. Bliss, Ward and Rosevelt. The Southern emissaries didn’t believe this for a minute, reportedly telling the men that they were being duped, and would be forced into enlisting the Union army. Apparently this caused around 50 of the men to refuse to embark, but the rest boarded the Great Western regardless. Those men who didn’t go aboard were found accommodation in the local workhouse, some of them saying they had been entrapped. A Confederate attorney in Liverpool, Mr. Hull, reported a breach of the Foreign Enlistment Act to the British authorities, who then refused to clear the Great Western to sail. Indeed, on 17th November British custom agents and police even boarded the vessel with the support of the ship’s Captain, questioned the men aboard, and asked if any of them wanted to leave– apparently only four of the men decided to disembark. One prospective passenger reportedly said that ‘they were determined to go to America or some other country, and not to be left destitute in England any longer’ while another said he was ‘not going back to be put in jail to pick oakum.’ One report stated that there was a German on the ship ‘dressed in a kind of military uniform’ who appeared to exercise authority over the passengers, along with a man from Stalybridge who was addressed as ‘Sergeant.’ After a considerable time held in port, the lack of evidence eventually meant the Great Western was allowed to sail, and she departed for New York with the majority of the steerage passengers aboard. (4)

Were Robert Jenkins and his fellow passengers induced to enlist, having thought they were going to a glassworks, or had they known all along they were to become soldiers? It is unlikely we will ever know with absolute certainty, but the balance of evidence suggests that they intended to join the military. The fact that 50 of the men decided not to go aboard the Great Western when they were approached by Confederate agents suggests not all of them were very keen, but it is of note that the majority still chose to travel even after they had become aware of what might lie in store. Interestingly two of those who stayed in Liverpool reportedly gave affidavits saying they had been promised commissions in the Federal army. It was certainly not the only time this type of event occurred. A previous post on the site examined a similar incident with men from Ireland. When the Great Western arrived in New York, the local newspapers were quick to pick up on the story. The 24th January 1865 New York Times noted that 93 men had arrived on the vessel having ‘left England with the purpose of enlisting in the army.’ Apparently only 42 were deemed physically fit enough to be accepted, though unscrupulous bounty-brokers reportedly succeeded in getting a few others through the process. Many others commented on the arrival of the men. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of 4th February 1865 stated that the men had been taken over from England to join the army by a man called Shaw. Leslie’s noted that although the men were supposedly ‘glassblowers’, none of them held that profession, and ‘all of them well understood the errand they were coming on, which was to enlist in the army of the United States.‘ If the report is to be believed Shaw was ultimately disappointed:

‘On arriving in this country the men soon found out, through the runners and harpies that continually prowl around Castle Garden, that they could obtain more than the sum promised by Shaw, and repudiating the fact that for several weeks he had supported them and paid their passages, stood ready to sell themselves to the highest bidder. The bidder was not long wanting, and appeared in the shape of a New York County Supervisor, who offered the men $650 cash each to enlist as substitutes.’ (5)

An extract of the manifest from the Ship Great Western, showing Robert Jenkins and some of the other men who enlisted when they landed in New York (Ancestry.com)

The Leslie’s account may be close to the truth of what happened. The muster roll abstracts for six of the recruits describe them as substitutes. Given their apparent poor circumstances, the prospect of a potential financial windfall, and the fact that military service sped up the naturalization process, it is little wonder that the Great Western passengers found American military service enticing. Many of them went on to defy popular notions of late war substitutes and bounty men during their military service, as all but one of those thus far identified appear to have been honorably discharged or, in the case of John Winter, died in service. In fact, six of them were even promoted to the rank of corporal during their tenure and at least two were wounded in battle. There is nothing here to indicate that these men were shirkers, ‘bounty jumpers,’ or had any serious intention of deserting. (6)

We are still investigating these men, and we welcome anyone who has any further information to share. In the meantime, here are some details about a few of these off-the-boat soldiers. Robert Jenkins survived his wound and heeded the call to ‘go West, young man.’ He appears on an 1897 register of veterans in the U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers as having checked in to the Sawtelle, California Veterans Home suffering from dyspepsia and rheumatism. He is single, his occupation, ‘railroader’ and his residence subsequent to his discharge, Glenn’s Ferry, Idaho. Jenkins is listed in subsequent censuses living at the Sawtelle Veteran’s Home in California through at least 1920. He died in 1931 and was buried at Los Angeles National Cemetery. Patrick Hastings, a native of Limerick, served beside Jenkins in Company E of the 64th, and was likewise wounded at Jones’ Farm. Hastings made a career out of soldiering and served in no less than four regiments of the U.S. Regular Army following the Civil War. Subsequent records suggest he may have been as young as sixteen when he enlisted in the 64th New York. He died in 1920 and was buried in Leavenworth National Cemetery in Leavenworth, Kansas. Census records indicate that Henry C. (or Harvey) Mayhew returned to his native England after the Civil War. An ancestry.com profile for him created by Nicolas Jouault indicates that his birthplace was St Pancras, England and demonstrates via census records that he was living in England again by 1871. (7)

Immigrants in Castle Garden, New York in 1866 (Library of Congress)

* The original caption for the photograph erroneously records that Robert Jenkins was a member of the 6th New York Infantry. The 6th were no longer in service by 1865, and no Robert Jenkins is recorded on their muster rolls.

**This Great Western is not to be confused with Brunel’s famous SS Great Western which was broken up in the 1850s. The vessel discussed here was a packet ship built in New York for the Black Ball Line in 1851. To add to potential confusion, the U.S. Navy also had the U.S.S. Great Western in service at this time.

(1) National Museum of Health and Medicine, Official Records: 302-3; (2) New York Passenger Lists 1820-1957, New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts 1861-1900; (3) Moffat 1965, New York Times 24th January 1865, Barnes & Barnes 2005: 251; (4) Wilding to Seward in Papers Relating to Foreign Affairs 1865: 32-36, Frank Leslie Illustrated Newspaper 4th February 1865, New York Times 24th January 1865; (5) Barnes & Barnes 2005: 251, New York Times 24th January 1865, Frank Leslie Illustrated Newspaper 4th February 1865; (6) New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts 1861-1900; (7) National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers 1866-1938, United States Federal Census, U.S. Civil War Pension Index, U.S. Army Register of Enlistments 1798-1914, Nicolas Jouault Website;

References

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 4th February 1865. Town Gossip.

National Archives and Records Administration. U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2000.

National Museum of Health and Medicine CP0980, Robert Jenkins.

New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 [database on-line]. Year: 1865; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 248; Line: 40; List Number: 31; via Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

New York State Archives, Cultural Education Center, Albany, New York; New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900; Archive Collection #: 13775-83; Box #: 249; Roll #: 1121-1122; via Ancestry.com. New York, Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

New York Times 24th January 1865. The Draft: Number of Enlistments. Running Men Out of the City. Protection of Soldiers’ Bounties. Substitutes. Fraudulent Enlistments. The County Volunteer Committee. Kings County Quota. The Quota Under the Last Call.

Official Records of the War of Rebellion Series 1, Volume 51, Part 1. Report of Maj. Theodore Tyrer, Sixty-fourth New York Infantry, of operations March 25.

United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006.

U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

U.S. Department of State 1865. Papers relating to foreign affairs, accompanying the annual message of the president to the first session thirty-ninth congress. Correspondence: Great Britain. No. 390 Mr Wilding to Mr. Seward, United States Consulate, Liverpool, November 18, 1864. pp. 32-36

U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Barnes, James J. Barnes & Barnes,Patience P. 2005. The American Civil War Trough British Eyes: Dispatches from British Diplomats, Volume 3, February 1863- December 1865.

Moffat, William C., Jr. 1965. Soldiers’ Pay. Cincinnati Civil War Roundtable.

Filed under: Battle of Jones' Farm, Guest Post, Recruitment Tagged: 10th New York Cavalry, 64th New York Infantry, Civil War Conscription, Civil War Substitutes, Federal Draft, Foreign Enlistment Act, Illegal Recruitment, Irish American Civil War

Recruited Straight Off The Boat? On The Trail of Emigrant Soldiers From the SS Great Western

The medical images of Civil War soldiers taken towards the end of the war are undeniably compelling. Friend of the site Brendan Hamilton has previously explored the story of one of these men in a guest post, which you can read here. It was while researching another wounded Irishman that Brendan uncovered an extraordinary link between him and a number of other emigrant Union soldiers who all shared something in common– they had arrived in New York on the same day, in the same ship. This prompted him to carry out extensive research into these men and their fate, which Brendan shares with us in detail below. In addition to this, I was able to uncover some details as to the men’s origins and emigration. What emerges is a remarkable story which takes us from the manufacturing centres of Northern England to New York, via the Liverpool docks, on the trail of potential illegal recruitment into the Federal army.

The medical image taken of Robert Jenkins after his wounding in 1865, only months after arriving in America (National Museum of Health & Medicine)

The image above is 19-year-old Private Robert Jenkins of Company E, 64th New York Volunteer Infantry. Private Jenkins was wounded in the face at the Battle of Jones’ Farm, during the Petersburg Campaign of the American Civil War. The description that accompanies this remarkable photograph from the National Museum of Health and Medicine notes that the ball entered Robert’s face to the left of his nose, exiting through his cheek.* Robert Jenkins was an Irish immigrant who enlisted in the U.S. Army on 14th January, 1865, relatively late in the war. At Jones’ Farm, his regiment was sent to provide support to the 69th New York and the 28th Massachusetts of the famous Irish Brigade. The latter two units had run out of ammunition and required the 64th to hold their position while they awaited resupply. Jenkins received this wound while helping fellow Irishmen in combat on foreign soil, soil that he himself had only set foot on less than three months prior. (1)

In fact, Jenkins enlisted on the very same day he stepped off the docks in New York City. In researching this man’s past, I stumbled over something quite amazing— a ship manifest revealing that at least 33 European men traveled together to the United States from the port of Liverpool and immediately enlisted in the Union Army. Below is a spreadsheet of recruits who enlisted in the 64th New York Infantry, 10th New York Cavalry, and several other units on or soon after 14th January, 1865. The information is from their muster roll abstracts. All are recorded as having enlisted either in New York City or Brooklyn, and all appear to match men who arrived in New York on the Great Western on that very same day. All of these men but one (Bartholomew Early) appear on the last two pages of the manifest (a portion of which is reproduced below), listed with other men of military age. They appear to have been deliberately recorded in a separate section of the manifest, even though they were not all quartered on the same part of the ship. According to the muster rolls, thirteen were natives of Ireland, ten from England, four from Germany, three from France, one from Scotland, and one from Wales. (2)

Name

Age

Birthplace

Occupation

Unit

Enlisted

Fate

Bornholtz (or Barnholtz), Herman

18

Germany

Painter

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Brown, Joseph

23

England

Wood turner

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Bruce, Andrew

30

Scotland

Laborer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Brian (or O’Brian), Thomas

30

Ireland

Laborer

Co. H

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Davis, James

26

Wales

Laborer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Fries, Carl (or Friez, Charles)

32

Germany

Soldier

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Jordan, Patrick

21

Ireland

Laborer

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Hawkins, James

21

England

Servant

Co. B

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Hastings, Patrick

20

Limerick, Ireland

Miller

Co. E

14-Jan

Wounded, 25 March, Discharged

Hoben, John

21

Ireland

Baker

Co. H

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Holloway, Harry

27

England

Galvanizer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Jenkins, Robert

19

Ireland

Tailor

Co. E

14-Jan

Wounded, 25 March, Discharged

Jones, George

23

London, England

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Kanarens (or Canarns), Alfred

23

England

Laborer

Co. G

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Kirker, William

18

Ireland

Moulder

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Mackin, John

25

Ireland

Bricklayer

Co. H

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Mayhew, Harvey

20

London, England

Gunmaker

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Muller, Conrad

24

Germany

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Salter, William

22

Germany

Clerk

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Scott, Walter

22

Ireland

Clerk

Co. G

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Smith, John

27

Ireland

Servant

Co. A

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Watters (or Waters), Thomas

29

England

Servant

Co. A

14-Jan

Mustered Out (in hospital)

Wells, John

24

England

Laborer

Co. D

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Winter (or Winters), John

32

England

Engineer

Co. A

14-Jan

Died 31 January near Petersburg

Wood, James

35

England

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Wood, Harvey (or Henry)

20

Ireland

Baker

Co. E

14-Jan

Mustered Out

Bulens (or Bulins), Joseph

28

France

Laborer

10 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Transferred 1 NY Prov. Cav.

Ismael, Bizen

20

France

Baker

10 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Transferred 1 NY Prov. Cav.

Ward, James

30

Ireland

Laborer

10 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Transferred 1 NY Prov. Cav. (Awaiting trial)

Early, Bartholomew

18

Ireland

48 NY Inf.

19-Jan

Deserted 6 August

Hickey, Michael

30

Ireland

48 NY Inf.

19-Jan

Wounded, 21 February, Wilmington

Morgan, John

34

6 NY Cav.

14-Jan

Deserted 24 May

Gerard, Prosper J

23

Reims, France

14 US Inf.

23-Jan

Unknown

Table 1. Union soldiers traced to the Great Western.

What is the story behind these men’s service? To uncover this we must first look at the main drivers in the Union recruitment system by January 1865. The enrollment act of 3rd March, 1863, which instituted a policy of conscription into the Union Army, allowed draftees to be exempt if they either paid $300 or provided a substitute to serve in their stead. As a result, prospective substitutes were often offered hundreds of dollars to join the Union Army. Private substitute brokers sprung up in major Northern cities, facilitating such recruitment and raking in profit on commissions. In addition to the money to be made by signing up as a substitute, bounties, a form of signing bonus, were also offered to further encourage new recruits. These could be as high as $1,500. The value of these bounties was often dictated by the need of a particular area to provide sufficient numbers of volunteers to reach their volunteer quota and thus stave off the draft. Clearly, the need for new recruits was severe, and European immigrants offered an attractive solution. We know that the Federal government rarely if ever– as is depicted in the film Gangs of New York and discussed here– engaged in direct dockside recruitment. The notion of directly recruiting recently arrived immigrants at Castle Garden was debated but (at least publicly) rejected by the New York Commissioners of Emigration in July of 1864. However, potential new recruits did not have to travel far if they wanted to enlist. Added to that, substitute brokers and other agents seeking to make money out of potential enlistees operated in close proximity to the port of arrival. In 1865 the New York Times reported on the ‘swarm of bounty swindlers who infest our public-thoroughfares.’ New York based British diplomat Joseph Burnley spoke of the ‘rascalities and swindling practices of the bounty brokers…the distance from the Emigration Depot to this office is about 400 yards, and the number of recruiting and enlisting rooms and booths within that distance is about 7 or 8, with printed notices in both German and English. In the neighbourhood of these booths and rooms brokers and runners swarm; and the unhappy emigrants who land here are necessarily obliged to run the gauntlet of these mantraps and harpies.’ Is it possible that the Great Western immigrants, including Robert Jenkins, were assailed shortly after their arrival in New York, ultimately induced to enlist en-masse by one of these brokers? (3)

Bounty brokers on the look out for substitutes (Library of Congress)

To discover the origin of Robert Jenkins and the other men’s enlistment we must return to Liverpool in 1864. It was there on 15th November that some 200 men arrived in the port to board the Great Western as steerage passengers. The majority, reportedly ‘destitute and half-starved’, had come from different manufacturing districts of Lancashire and were joined by some Irish and Germans at the quayside. However, as was the case in Irish port cities, Confederate agents were ever watchful of such groups. These agents soon discovered that the men’s passage to New York had been paid by an American, reportedly with a view to having them work in a New York glass works owned by Messrs. Bliss, Ward and Rosevelt. The Southern emissaries didn’t believe this for a minute, reportedly telling the men that they were being duped, and would be forced into enlisting the Union army. Apparently this caused around 50 of the men to refuse to embark, but the rest boarded the Great Western regardless. Those men who didn’t go aboard were found accommodation in the local workhouse, some of them saying they had been entrapped. A Confederate attorney in Liverpool, Mr. Hull, reported a breach of the Foreign Enlistment Act to the British authorities, who then refused to clear the Great Western to sail. Indeed, on 17th November British custom agents and police even boarded the vessel with the support of the ship’s Captain, questioned the men aboard, and asked if any of them wanted to leave– apparently only four of the men decided to disembark. One prospective passenger reportedly said that ‘they were determined to go to America or some other country, and not to be left destitute in England any longer’ while another said he was ‘not going back to be put in jail to pick oakum.’ One report stated that there was a German on the ship ‘dressed in a kind of military uniform’ who appeared to exercise authority over the passengers, along with a man from Stalybridge who was addressed as ‘Sergeant.’ After a considerable time held in port, the lack of evidence eventually meant the Great Western was allowed to sail, and she departed for New York with the majority of the steerage passengers aboard. (4)