Damian Shiels's Blog, page 38

April 6, 2015

‘Killed At The Surrender': The Journey of Two Irishmen to Their Deaths at Sailor’s Creek

There is something particularly poignant about those who lose their lives in the final throes of a conflict– deaths that come when the soldiers themselves are aware the end is in sight. In many cases, the timing of such deaths must have made it even more difficult for those at home to accept. 150 years ago today, at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, Virginia, yet more names were added to the butcher’s bill of the Civil War. Among them were Irishmen James McFadden and Thomas Brennan. The circumstances which led these two men to their fate could not have been more different; one had chosen to be there, the other had not been given a choice. Each of their stories had elements which must have accentuated the grief felt by those they left behind.

Massmount, Fanad, Co. Donegal, where James McFadden was married. Interestingly this isloated church and graveyard is also the final resting place of a number of my own direct ancestors. (Google)

James McFadden was from the Fanad peninsula in Co. Donegal. On 3rd December 1850 he had married Anna Duffy in the picturesque rural setting of Massmount Chapel. Sometime later the couple emigrated to the United States, where they made their home among large numbers of other Donegal Irish in the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. If the couple did have any children, none survived into adulthood. When war came in 1861 James was an early volunteer. He mustered into Company G of the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry, a 3-month-unit, on 21st April. When the opportunity came to re-enlist in the regiment for three years service he did so, becoming a private in Company F on 2nd August. The 23rd Pennsylvania were one of the colourfully uniformed zouave units, and over the course of the next three years James marched with them onto battlefields like Seven Pines, Chantilly, Second Fredericksburg, Salem Church, Gettysburg and eventually the Overland Campaign. The Donegal man was wounded at the Battle of Cold Harbor in 1864, but was soon able to return to active duty. The 23rd Pennsylvania mustered out on 8th September 1864 having completed its service, but James didn’t go home with them. He had re-enlisted as a veteran, and along with the other men who had done so, was transferred to see out the remainder of his term in the ranks of the 82nd Pennsylvania Infantry, becoming a Corporal in Company E. (1)

In April 1865, as the Federals pursued Robert E. Lee’s Confederates following the fall of Richmond, the 82nd Pennsylvania was part of Horation G. Wright’s Sixth Corps. On 6th April they found themselves forming part of a Union line of battle at the Hillsman Farm sector of the Sailor’s Creek battlefield. Facing Rebels of Ewell’s Corps across Little Sailor’s Creek, they struggled through a ‘deep difficult swamp’ and ‘almost impenetrable undergrowth and forest’ to the attack, in the process taking a severe flanking fire from the Confederate lines. Changing front, the 82nd were able to engage the enemy and play their role in what would ultimately be a major Union victory. However, they sustained heavy losses– 19 men had been killed and a further 80 wounded. James McFadden was among them. He had survived almost four years of continual service only to fall just as the war was coming to an end. His loss would have been hard on Anna back in Philadelphia. When she wrote to the pension bureau with a query in 1888, Mary noted that her husband had ‘went all through the war, and was killed at the surrender of Richmond.’ That he had survived so much, only to be taken right at the end was clearly tough to take. (2)

Soldiers of the 23rd Pennsylvania Infantry playing cards (History of the Twenty Third Regiment)

The circumstances by which Thomas Brennan found himself at Sailor’s Creek on 6th April were very different to his fellow countryman. Unlike James McFadden, we don’t know where in Ireland Thomas was from. He had married fellow Irish emigrant Mary Grant at the St. Vincent de Paul Church in Minersville, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania on 13th May 1855. They went on to have a number of children, John (born c. 1856), Thomas (born c. 1858), Margaret (born c. 1860) and Patrick (born c. 1863). As has been examined in a recent post, Schuylkill County was home to a large community of Irish coal miners who were not afraid to challenge– sometimes violently– the authority of both their employers and the government during the war. Schuylkill had seen some of the most determined resistance to the draft witnessed anywhere in the north. Like the majority of Irish in the area, Thomas was a miner. The 1860 Census found the then 30-year-old and his 29-year-old wife living in the strongly Irish Cass Township in Schuylkill with their children. There is every chance that Thomas was just as opposed to the draft as many of his Irish miner colleagues; indeed he may even have participated in some of the widespread resistance to it. (3)

The authorities had such difficulty in drawing up a list of the men eligible for the draft in Schuylkill County that eventually officials were sent in backed by troops to seize the payroll of mine operators and get the miner’s details. Whether Thomas Brennan had given his information willingly or had them taken forcibly is unknown. Either way, his name was pulled in the draft at Pottsville and he was enlisted into Company A of the 99th Pennsylvania Infantry on 19th July 1864. On the 6th April 1865 the 99th Pennsylvania, part of Humphreys’ Second Corps, found themselves facing elements of Gordon’s Confederate Corps at the Lockett Farm sector of the Sailor’s Creek battlefield. Throughout the day they had conducted a series of charges against Confederate skirmish lines. Their brigade captured over 1300 enemy troops during their advance, also taking artillery and battleflags. It proved to be the last day on which the 99th Pennsylvania Infantry would lose men to combat during the American Civil War– and one of them was the coal miner Thomas Brennan. Mary Brennan lived in Schuylkill County for the rest of her life, dying there on 18th April 1903. Her husband had died in the final days of a conflict that he may well have felt little investment in. Did Mary harbour any resentment as a result? (4)

The circumstances which led James McFadden and Thomas Brennan to Sailor’s Creek were very different. One had been a volunteer from the war’s early days, fighting for the Union for the full four years of the conflict. The other had been drafted from an area renowned for it’s anti-draft sentiment, and was ordered to the front to help prosecute the war in it’s final months. The family’s of both would have had cause to feel aggrieved at their loss so close to the end of the dying. They would certainly not have been alone.

The Surrender of Ewell’s Corps at Sailor’s Creek by Alfred Waud (Library of Congress)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) James McFadden Widow’s Pension File, Survivors Association 1904: 22, 224; (2) Official Records: 949, James McFadden Widow’s Pension File; (3) Thomas Brennan Widow’s Pension File, 1860 Federal Census; (4) Kenny 1998: 91, Official Records: 783-4, Michael Brennan Widow’s Pension File;

8p.22, 224

References & Further Reading

Thomas Brennan Widow’s Pension File WC64214.

James McFadden Widow’s Pension File WC71212.

1860 US Federal Census.

Kenny, Kevin 1998. Making Sense of the Molly Maguires.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Volume 46, Part 1. Report of Col. Isaac C. Bassett, Eighty-Second Pennsylvania Infantry.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Volume 46, Part 1. Report of Col. Russell B. Shepherd, First Maine Heavy Artillery, commanding First Brigade.

Survivors Association Twenty Third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. 1904. History of the Twenty Third Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Birney’s Zouaves.

Civil War Trust Battle of Sailor’s Creek Page

Sailor’s Creek Battlefield State Park

Filed under: Battle of Sailor's Creek, Battle of Sayler's Creek, Donegal, Pennsylvania Tagged: 99th Pensylvania Infantry, Appomattox Campaign, Battle of Sailor's Creek, Birney's Zouaves, Donegal Veterans, Draft Resistance, Draft Schuylkill County, Irish American Civil War

April 4, 2015

‘The Next War': The New York Irish-American Looks Towards John Bull, April 1865

150 years ago this month the American Civil War seemed on the verge of ending. The fall of Richmond on 3rd April appeared to have hammered a final nail in the coffin of the Confederate cause. When the New York Irish-American Weekly came out on Saturday 8th April, they printed a piece entitled ‘The End of the War’, which predicted imminent victory. Revealing their strong Democratic affiliations, they also cautioned on the need for a reconciliatory peace with the soon to be former Confederacy. It is often noted that many Irish-Americans displayed ‘dual allegiance’ to both the United States and Ireland. This outlook is clearly apparent in another of the articles in the 8th April issue, entitled ‘The “Next War.”‘ Even as the Civil War continued, the Irish-American turned its gaze across the Atlantic towards ‘John Bull’, advising that America embark on ‘the next war’– to bring down Great Britain.

THE END OF THE WAR

The most skeptical doubter of the eventual triumph of the national arms must be convinced by this, that the end of the rebellion which has for four years convulsed our once happy land with the destructive throes of civil war, cannot be far distant. In view of the recent victories of our forces, the capture of the rebel Capital, and the cutting off of the remnant of the Confederate armies from most of the sources of supply necessary to their maintenance, as fighting organizations, it is taking a very moderate estimate of the probabilities of the military situation, to suppose that, before the recurrence of the third anniversary of the first battle of the attempted revolution, all organized resistance will have ceased within the land, and the “Stars and Stripes” shall once more wave in undisputed sway throughout the length and breadth of the Republic.

But, even this is not the end of the war. It is now, above all former periods, that wise statesmanship and patriotic counsels are needed, not merely to bring a disastrous struggle to a termination, but to replace the country in the position of strength and stability it occupied before the passions and ambition of unscrupulous politicians plunged it into the sea of troubles in which so much of that which is most valuable to a young nation has been lost. In bringing back the seceded States into the Union, no one who truly loves the Republic, or appreciates the genius of her institutions, can desire that a single drawback should be permitted to mar the happiness of so blest a reunion. We trust, therefore, that the rumor, that President Lincoln is about to mark his sense of the national importance of our late successes by the issue of a proclamation of amnesty, is true; and that, when the struggle ceases, we shall receive back once more, not mere wasted fields or subjugated populations, but those component parts of our nationality, that, however they may have been estranged for a time, still share in the sovereign character of the American people, and will yet constitute an element of renewed and augmented strength, from the mutual respect which the bitter lessons of the past four years, at least, have inculcated. (1)

‘The Fenian Banner’, 1866 (Library of Congress)

THE “NEXT WAR”

Our domestic broil, thank God, is almost at an end; and within our bordered the blessings of peace will, ere long, be experienced. But we are not, therefore, amongst the anxious inculcators of “peace.” On the contrary, we take this opportunity to declare, in advance, in favor of “the next war.” There is a certain party “over the way” with whom we have an account to settle. It has been running longer than some people imagine; but the last four years have added so many and such heavy items to the bill, that it cannot hold over any longer. We “go in,” then, for bringing John Bull “square up to the rack,” and exacting restitution and retribution to the last iota. If any of our volunteers should be tried of fighting (which we doubt, with such a chance at the old pirate ahead), we will guarantee that no “draft” will be needed to fill their places. For a dash at John Bull they are ready, on both sides of the Atlantic, half a million of the finest fighting material under the sun,– the same that has given to the Union so many heroic defenders. Let America but say the word and the “Union Jack,” the red flag of oppression and spoliation, goes down– at once and forever– before the banner of Freedom. (2)

(1) New York Irish American Weekly 8th April 1865; (2) Ibid.;

References

New York Irish American Weekly 8th April 1865. The End of the War

New York Irish American Weekly 8th April 1865. The “Next War”

Filed under: Discussion and Debate Tagged: Fenian Movement, Irish American Civil War, Irish American Weekly, Irish in the Union Army, Irish Revoluntionaries, John Bull, New York Irish, Reconstruction

April 1, 2015

The Madigans: Famine Survival, Emigration & Obligation in 19th Century Ireland & America

Each pension file contains fragments of one Irish family’s story. They are rarely complete, but nonetheless they often offer us rare insight into aspects of the 19th century Irish emigrant experience. Few match the breadth of the story told in the Madigan pension file. That family’s words and letters take us from the Great Famine in Rattoo, Co. Kerry to New York and Ohio and ultimately to the first battlefield of the American Civil War. From there we journey from neighbourhoods as diverse as the Five Points and Tralee, where those unable to take the emigrant boat still counted on those who had made new lives across the Atlantic.

I frequently make reference to the fact that many of the Irish impacted by the American Civil War were Famine-era emigrants. Despite this, among the hundreds of Irish pension files I have examined, the Famine has only been directly referenced twice. Although we know that the Great Famine was the ultimate reason behind why many emigrated, that fact was an irrelevant detail when it came to the process of securing a government pension– and so it goes unmentioned. The file relating to Kerry native Thomas Madigan is typical in this respect; the word ‘Famine’ is nowhere among the 39 pages of documents contained within it. However, examination of this remarkable file suggests that the Madigans had not only suffered as a result of the Famine, but that members of their immediate family had not survived it.

The Madigan story begins in the north Co. Kerry parish of Rattoo on 21st November 1835. That was the day that James Madigan and Mary Costello were married by the Reverend F. Collins in front of witnesses Thomas Lovit and William Loughlin. We know that the couple had at least three children who survived to adulthood– Thomas (born c. 1840), James (born c. 1841) and Catherine (born c. 1845). Many years later, Mary revealed that her husband James had died in Kerry in March of 1847. That year became known in Ireland as ‘Black ’47’, the period that witnessed the peak of the Famine calamity. Mary never related how her husband died, but a family friend recounted that the illness that killed James was dropsy. It is this piece of information that suggests that James was a Famine victim. Of the nutritional deficiency diseases which caused large numbers of deaths during the Famine, starvation and marasmus were the most common, but they were followed by dropsy– an oedema or accumulation of fluid in the body, often caused by malnutrition. (1)

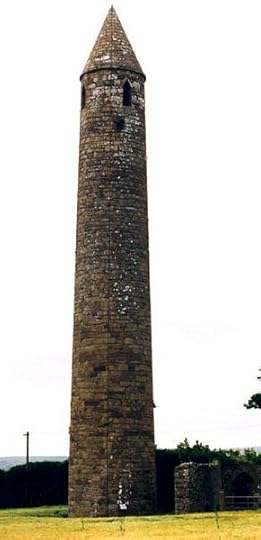

Rattoo Round Tower, Co Kerry, a site the Madigans were undoubtedly familiar with. (Anne Burgess)

Catherine Madigan later remembered that the family emigrated to America around the year 1850, when she was about 5 years-old. No doubt they were relieved to escape the difficult conditions life had brought them in Co. Kerry. Catherine’s widowed mother Mary married again in December of 1853, wedding a man called Maurice Kennedy. The family moved to Columbus Ohio, and another child, Maurice Jr., was born there on 16th November 1854. But all was not well in the Kennedy household. Having taken her family out of Famine-ravaged Ireland, Mary now had to deal with yet another trial– a violent husband. Maurice Kennedy was described as a ‘habitual drunkard and man of bad character’ who was frequently being arrested for disturbing the peace. Mary’s daughter Catherine felt forced to leave the household due to the ‘ill-treatment of her mother.’ Finally, after six years of marriage, enduring constant ‘ill-treatment and brutality’, Mary could take no more and decided to ‘seek the protection of her children.’ In 1859 her son Thomas, who had stayed in New York and was working as a tin-smith, sent the money his mother needed to flee Columbus and Maurice’s violence. Mary never heard from her second husband again. She would later hear rumours that he had died of yellow fever in New Orleans around 1860. (2)

Back in New York, Mary’s son Thomas set his mother up with a place to live and got her established with furniture and the other necessaries of life. No doubt due to the abusive nature of the relationship, Mary, encouraged by family and friends, stopped using the Kennedy name of her second husband, and reverted to being called Mary Madigan. One can only imagine the emotional scarring that her life experiences up to this juncture had caused. As 1861 approached, Mary was living with Thomas (and presumably Maurice Jr.) at 207 Mott St. in Manhattan. Despite having left Ireland as a boy, Thomas had clearly maintained an interest in Ireland; he was a member of the 69th New York State Militia, an overwhelmingly Irish militia organisation. In 1860 its commander Michael Corcoran achieved notoriety for refusing to parade the regiment on the occasion of the visit of the Prince of Wales. Given the impact of the Famine on Thomas Madigan’s family, one imagines this was a decision he most likely agreed with. (3)

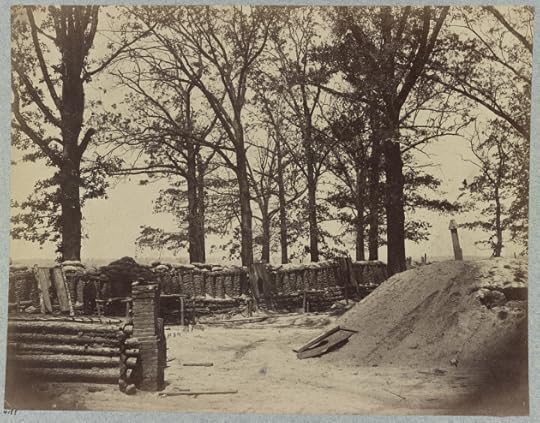

Officers of the 69th New York State Militia pose beside one of the guns in Fort Corcoran prior to the Battle of Bull Run. Thomas Madigan wrote home to his mother from here. (Library of Congress)

When war came in April 1861, the 69th New York State Militia answered the call for three months service, and headed to Washington D.C. Thomas enrolled for three months service on 20th April, and by the 21st of May he and the regiment were occupied in the construction Fort Seward (later officially named Fort Corcoran) on Arlington Heights. There, Thomas took the opportunity to write to his mother:

Fort Seward May 21 1861

Arlington Heights, Va

My dear mother

I take this opportunity of sending these few lines hoping that they may reach you in good health as I am at present. When [sic.] we took up our position on Arlington Heights and know [sic.] we are building a fort to be called Fort Seward it will be a large one and it will overlook the river Potomack and the City of Washington and if the enemy had it they could destroy Washington and Georgetown without losing a man. Dear Mother we are in the center of the enemy and in the enemys state. To day we were sworn [?] in and we expect to be home marching up Broadway about the 9 or 10 of August

But remains your affectionate son till death

Thomas Madigan

Company I 69 Regt

NYSM (4)

Precisely two months after the letter, on 21st July 1861, the 69th New York State Militia were engaged in the first major battle of the war at Bull Run, Virginia (read the 69th’s after action report and find out all about the battle on the Bull Runnings site here). The fight ended in defeat for the Union. As soldiers– and numerous civilian spectators– fled back towards Washington D.C., many Federal wounded were left on the field. Among them was Thomas Madigan, felled by a bullet to the leg in what was his first battle. Thomas’s limb was amputated, probably by northern surgeons who had volunteered to stay behind with their charges. Meanwhile, back in New York confusion reigned as reports filtered through of the reverse. Newspapers tried to report the losses to those at home, but the fate of many of those who had been captured remained unclear. On 12th August a number of Union surgeons were paroled, and they carried with them into Union lines lists of wounded men still in Confederate hands. The New York Irish-American printed the list in its 24th August issue; one of the names that appeared was Thomas Madigan. The list recorded that he was in Centreville, but by then he had been moved to St. Mark’s Hospital in Richmond. By the time his name was printed in the Irish-American he was already dead, having passed away on 21st August. The 69th New York had returned to New York on 27th July, nearly two weeks before Thomas’s predicted date. Unfortunately he never got an opportunity to go ‘marching up Broadway’ with his comrades. (5)

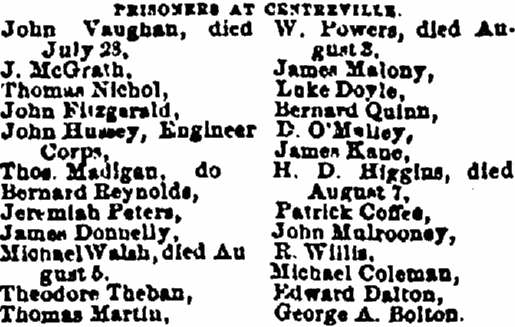

Thomas Madigan’s name on a list of 69th New York prisoners at Centreville, published in the New York Irish-American (GenealogyBank)

Before Thomas had left for the front he had made sure that his mother was set up with regular relief payments, supplied by the City of New York. His death demonstrates just how much of a ‘second trauma’ the American Civil War could be for Famine emigrants. By 1861, Mary had endured the loss of her first husband to Famine, had escaped the clutches of an abusive second husband, and then experienced the death of the son who had facilitated that escape. One wonders as to her thoughts when her other son James decided to enlist in the 158th New York Infantry– part of ‘Spinola’s Brigade’. The 21-year-old became a private in Company K on 12th August 1862, and thankfully survived to muster out with his company at Richmond on 30th June 1865. (6)

The laws which entitled Mary to a dependent mother’s pension had not been in place when Thomas died, and Mary had initially thought that because he was one of the Militia ‘three month men’ (as opposed to a three-year volunteer) that she would not be entitled to any payments. She started her pension application process in August 1862, when she was recorded as being 50 years of age. She was then living at 16 Mulberry Street in the notorious Five Points slum district of Manhattan. It was an area teeming with fellow Irish immigrants, many of them from her native Kerry. (7)

Mulberry Bend, Five Points, New York in 1896. Mary Madigan lived close to here in 1863 (Jacob Riis)

Mary had made a crucial error in her application, one that would be a factor in delaying her pension approval for many years. She recorded her name as Mary Madigan rather than Mary Kennedy. Cruelly, the name of her second-husband, a name she had discarded, had come back to haunt her. The pension bureau sought clarifications as to why she had not used it, and wanted information as to the whereabouts and fate of Maurice Kennedy. In addition, they wanted proof of her marriage to James Madigan in Co. Kerry. In order to obtain that proof she wrote to one of her Costello siblings back in Ireland. The response she received illustrates how those who had succeeded in emigrating, no matter what their circumstances, were looked upon for aid by those still at home. Although it is not clear from the letter if the correspondent was Mary’s brother or sister, what is apparent is that the letter writer had helped to fund the journey of another family member, ‘Jimmy’, to the United States. Interestingly, it seems Jimmy had also then become a soldier in the Union Army. Despite having revealed news of Tom’s death, Mary’s sibling doesn’t hesitate to chide Mary for having made ‘faithful promises but slow performances’:

Tralee March 31st 1863

Dear Sister I received your letter of the 17th I was sorry to heare of the death of poor tom may the lord have mercy on his soul- Dear sister when I heard your letter was at the causeway [Causeway, Co. Kerry] I went for it but could not get the lines you required untill now [the proof of Mary’s marriage]. Dear Sister you should suceed in getting this money I hope you wont forget poor Thomas soul get masses said for him and pray him constant as he went so suddenly. Dear Sister I had to leave Mr Masons a long time ago in bad health which was a grate loss to me and to set down and spend what I earned during the time I was with them. Dear Sister I am sorry I ever sent you Jimmy or lost the few to him that I did [the few pounds] to be the manes [means] of sending him to the war, I would want what I lost to him verry badley now myself for I am getting into bad health every day I am laid up at present with a scurvey in my feet and I fear I will have to leave my p[l]ace in concequence of them. I have a very good place at present if I could keep it I am living with Mr George Hillard of Mc Cinall [?]. Dear Sister I thought I would have got some assistance from you and Jimmy before now ye have made as I thought faithfull primisses [promises] but slow performances.

Dear Sister I hope you wont forget sending me some money for I feare I will want it very soon in concequence of my health which will cause me to leave my place. If it was the will of God to leave me my health I could do without from any one and as it not I crave you assistance may the Holy will of God be done in all things, Amen.

Catherine Brien will be going to America and she will tell you all about me direct your letter George Hillard Esq. Madgestrar Tralee Dea place. (8)

By the time the war concluded Mary was living with her daughter Catherine. She would eventually have her pension application granted on 25th July 1868. With the award the Madigan story once again fades back into obscurity. However, their remarkable pension file provides us with insight into one family’s arduous journey from Famine ravaged Ireland to an America which, at least initially, did not prove to be the promised land. Uniquely, it also offers a glimpse back across the Atlantic, towards the obligations that many Irish emigrants had towards those that had been left behind.

The Return of the 69th New York after the Battle of Bull Run, 1861, by Louis Lang. Thomas Madigan had been anticipating such a homecoming before Bull Run (New York Historical Society)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Thomas Madigan Dependent Mother’s File, Kennedy et .al. 1999: 104; (2) Thomas Madigan Dependent Mother’s File; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid., New York Irish American 24th August 1861; (6) Thomas Madigan Dependent Mother’s File, New York AG: 415; (7) Thomas Madigan Dependent Mother’s File, Anbinder 2002: 48, 98; (8) Thomas Madigan Dependent Mother’s File;

References

Thomas Madigan Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC116873.

New York Irish American Weekly 24th August 1861. Federal Prisoners at Richmond and Manassas.

New York Adjutant General Roster of the 159th New York Infantry.

Anbinder, Tyler 2002. Five Points.

Kennedy Liam, Ell Paul S., Crwaford E.M. & Clarkson L.A. 1999. Mapping the Great Irish Famine; A Survey of the Famine Decades.

Manassas National Battlefield Park

Civil War Trust Battle of Bull Run Page

Filed under: 69th New York, Battle of Bull Run, Irish Brigade, Kerry, New York Tagged: 69th New York State Militia, Battle of Bull Run, Five Points New York, Irish American Civil War, Kerry American Civil War, Kerry Veterans, New York Irish, New York Irish-American

March 27, 2015

‘As Good A Chance to Escape As Any Other': A Cork Soldier’s Aid to His Family in Ireland, 1864

Occasionally, I am asked why any Irish impacted by the American Civil War should be remembered in Ireland. After all, the argument goes, these people left our shores, and they weren’t fighting for ‘Ireland.’ In response, I usually point out that many were Famine-era emigrants, who often felt they had little choice but to leave. There are many other reasons for remembrance, but perhaps one of the most persuasive is that these emigrants tended not to forget those at home. Whether we realise it or not, the ancestors of many in Ireland today benefited greatly from something that Irish emigrants to America sent back- money. One such emigrant was a man named Thomas Bowler from Youghal, Co. Cork. His decision to enlist in the Irish Brigade was almost certainly borne from a desire to help his wife and child, more than 3,000 miles away across the Atlantic.

I have previously highlighted the substantial donations made by Union soldiers to Irish relief funds; as we discovered, many of those who gave to such causes were themselves killed within a matter of months. Money was also sent home from the front to family members, be they in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, or Ireland. Many of the dollars that traveled back to Ireland during the Civil War did so because of the efforts of the Irish Emigrant Society. Founded as a charitable organisation in 1841 to assist new arrivals from Ireland, it provided important advice to newcomers on where to go, what to do, and what to avoid. The Society also facilitated the sending of money orders and prepaid passenger tickets from New York to family back in Ireland. In 1850 members of the Society petitioned for a bank charter, and on 10th April that year the ‘Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank’ was born. Its founders envisioned it serving a dual role, in ‘furnishing the means of safe remittances to the distressed people of Ireland and of distributing in charities whatever of profits may arise therefrom’ and of ‘affording our people a safe deposit for their hard earnings.’ In 1850 alone, the modern equivalent of $4.6 million was sent back to Ireland via the Society. (1)

Irish emigrants sending money back to Ireland from the Emigrants Savings Bank in 1880 (Library of Congress)

The Emigrant Savings Bank was still going strong in 1864. Many men of the Irish Brigade (and indeed other units) put aside money in the bank that Spring. Some were veterans, but many others were new recruits, brought into the Brigade to refill its depleted ranks. All of them knew that a major campaign was coming. One of them was Captain (soon to be Major) Thomas Touhy of the 63rd New York, who had money deposited on 8th March. He left instructions on who was to receive it in the event of his death- he would be mortally wounded at The Wilderness two months later. Thomas McAndrew, who had enlisted in the 69th New York in November 1863, had his money put away in the Bank on 16th April. Like Major Touhy he was wounded less than a month later at The Wilderness, but survived to see the end of the war. 21-year-old Thomas Blake was not as lucky. He made his deposit on the 9th April, the same day he mustered into the 88th New York. By the 12th June he was dead, succumbing to disease in Washington D.C. (2)

Another Irish Brigade soldier who was making plans with his money that April was Thomas Bowler. The 35-year-old was also a new soldier, having enlisted in Brooklyn on 26th February 1864. For some reason Thomas chose to join-up under an alias, using his mother’s maiden name of Murphy. It was under this name that he would be recorded in the 69th New York. Thomas was not among those supporting a family in America. Instead, his wife Ellen (née Hubbert) and 6-year-old daughter Abigail were living on the other side of the Atlantic, in Youghal, Co. Cork. It is probable that Thomas was paving the way for his family to join him; it was common for one family member to travel to America in advance of the others, raising the money so that the rest could follow. Thomas may well have hoped that the large financial incentives on offer for enlistment in the Spring of 1864 would hasten that process for his family. However, Thomas’s next problem was how to get the money home to Ireland. Unable to get to the Emigrants Saving Bank himself, he entrusted his money to the regimental chaplain, who saw that it got to the bank in New York. Thomas used Youghal broker Thomas Curtin as an intermediary to get the money to Ellen. Curtin can be found in an 1867 street directory, which lists him as a Ship-Broker on Grattan Street, Youghal. As April wore on and signs grew that the campaign was about to commence, Thomas became anxious to learn if the money he had sent had arrived in Ireland. On 17th April he wrote this letter back to Ellen in Youghal:

Camp Near Brandy Station

April 17th 1864

My Dear Ellen

I sent some time ago through through [sic.] the priest attending this regiment 80 dollars which will I trust bring you 10 pounds of your money I sent it to Thos. Curtin broker in Youghal I hope you will have no difficulty in getting it. I hope you will not neglect answering it as soon as you receive it as it is natural to suppose that any man who sends so large a sum feels uneasy until such time as he receives an answer to it. I like soldiering very well, I do not know the moment we will go to the field of battle their will [be] great fighting this summer but of course I have as good a chance to escape as any other man. I am enlisted for three years or during the war. If it was over in the morning I would be discharged, but their is only a very poor chance of that but God is good and merciful. When you are writing let me know how all the neighbours are. I have no more to say but remain your affecttionate Husband Thomas Bowler.

Let me know how the child is getting on and all other things also let me know how is my brothers and sisters.

Address your letter

Thomas Murphy Company A

69th Regt N.Y.V. 1st Division 2nd Army Corps Washington D C

also let me know how is James Coughlan (3)

Just over two weeks after this letter was written- on 4th May 1864- the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan river to commence the Overland Campaign. Thomas was right about the ‘great fighting’ that the summer would bring. The first major battle was at The Wilderness, where the Irish Brigade were among those units engaged on the 5th and 6th May. Their Corps Commander, Winfield Scott Hancock, would remark of the Brigade’s actions on the 5th that ‘although four-fifths of its numbers were recruits, it behaved with great steadiness and gallantry, losing largely in killed and wounded.’ (4)

Irish Emigrant Society notice sent to Ellen Bowler in Youghal regarding her husband’s payment (National Archives/Fold3)

There would be little pause over the coming weeks of hard fighting to draw breadth. Back in Youghal, Ellen grew concerned when she heard no news from Thomas. The weeks turned into months, and eventually even the war itself ended. Still Ellen was unsure as to Thomas’s fate. Then, in 1866, a man called Michael Carroll traveled from New York to Youghal to visit his family. He met Ellen there, and told her that he had heard Thomas had been wounded in the war and died in hospital. A few months after that, a Mrs. Meaney in New York wrote to her sister in Youghal, one Mrs. Ahearne. In the letter Mrs. Meaney stated that ‘Mrs Bowler husband Tom Bowler was dead…he died in hospital of wounds received in action.’ In her application for a pension Ellen stated her husband’s death had occurred after the 17th April. She knew this because that was the date of Thomas’s last letter to her, the last word she ever had from him. Despite what friends said, there is no evidence to suggest that Thomas had died in hospital of wounds. He was reported missing in action on 7th May 1864, following the Battle of the Wilderness. Two weeks after his final letter to his wife, Thomas had entered the woods of Virginia for what was his first battle, and it would seem he never reemerged. (5)

Ellen’s pension was finally approved more than four years after her husband’s death, on 14th April 1868. In a postscript to their story, Thomas’s little girl Abigail would seek a continuation of the pension many years later. Now going by the name Alice, and using her married surname of Lynch, she wrote from Youghal to the Commissioner of Pensions on 29th August 1890. She stated how her father was ‘killed in one of the bloody battles of the war’ and how she was the ‘only child of the man who lost his life in the service of the United States leaving [her] an orphan unprovided for.’ She also cited her own ill-health and destitution as reasons she should receive payment, before signing off as ‘Alice Lynch, otherwise Bowler, otherwise Murphy.’ Her application seems to have been refused. The 1911 Census of Ireland records Alice as a 56-year-old charwoman living on Cork Lane, Youghal, with her two sons, Thomas (a fisherman) and Daniel (a farm labourer). Her family story poignantly highlights the efforts that many Irish soldiers went to in an effort to provide for their families. If Thomas Bowler had avoided death in The Wilderness of Northern Virginia, his little girl may well have been giving her name to a census enumerator in New York in 1910, rather than in Youghal in 1911. (6)

The Emigrant Savings Bank was still going strong in the 20th century. This 1912 photo shows the bank of the same site (51 Chambers Street) from which Thomas Bowler’s money had been sent in 1864 (Library of Congress)

*None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Casey 2006: 306-8; (2) Emigrants Saving Bank Transfer, Signature and Test Books, New York AG Rosters: 63rd, 69th, 88th New York; (3) Thomas Bowler Widow’s Pension File, Henry & Coughlan 1867: 340; (4) Thomas Bowler Widow’s Pension File, Official Records: 320; (5) Thomas Bowler Widow’s Pension File; (6) Thomas Bowler Widow’s Pension File, 1911 Census of Ireland;

References & Further Reading

Thomas Bowler Widow’s Pension File WC115828.

Emigrant Savings Bank Records, New York Public Library (accessed via ancestry.com).

Henry & Coughlan 1867. General Directory of Cork.

Marion R. Casey 2006. ‘Refractive History: Memory and the Founders of the Emigrant Savings Back’, in J.J. Lee & Marion R. Casey (eds.) Making the Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States, 302-331.

New York Adjutant General 1901. Roster of the 63rd New York.

New York Adjutant General 1901. Roster of the 69th New York.

New York Adjutant General 1901. Roster of the 88th New York.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 36, Part 1. Reports of Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, U.S. Army, commanding Second Army Corps, with statement of guns captured and lost from May 3 to November 1, and list of colors captured and lost from May 4 to November 1.

Civil War Trust Battle of the Wilderness Page

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park

Filed under: 63rd New York, 69th New York, 88th New York, Battle of The Wilderness, Cork, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 69th New York, Cork War Veterans, Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Wilderness, Irish Emigrant Society, New York Irish, Youghal History

March 25, 2015

‘I Trust the Almighty Will Spare Me My Life': Charles Traynor & the Battle of Skinner’s Farm, 25th March 1865

In March 1865, Charles Traynor wrote home to his mother Catharine in New York. A veteran of some of the most famed Irish Brigade actions of the war, he was still at the front as the conflict began to enter its final days. ‘I trust the Almythy will spear me my life’ he confided to her. A few days later, the Confederates launched a ferocious attack against Fort Stedman on the Petersburg lines. As part of the Union response, Charles and the 69th New York were ordered to advance on the enemy at a place called Skinner’s Farm- events which unfolded 150 years ago today. (1)

The interior of Fort Stedman, Petersburg, 1865. The object of the main Confederate assault on 25th March. Events here on the Union right would lead to the 69th New York being ordered forward on the left of the line, at Skinner’s Farm (Library of Congress)

Irish bricklayer Charles Traynor enlisted as a 34-year-old in New York City on 16th August 1862. A little over a month later, as a private in Company K of the 69th New York , he was wounded assaulting the Sunken Road at the Battle of Antietam. The following June he was transferred to Company A, but at some juncture in 1864 he was assigned to the 18th Regiment of the Veteran Reserve Corps. He was serving with these men in Washington D.C. on 1st November that year, when he wrote home to his mother. It was the week before President Abraham Lincoln took on the Democratic candidate and former commander of the Army of the Potomac, George McClellan, in the Presidential election. ‘Little Mac’ was immensely popular among the majority of Irish troops, and Charles was clearly hoping for his victory at the polls. Aside from politics, the soldier also found the time to complain about the food:

Washington City

November 1st 1864

My Dear Mother I received yours of the 28 of last month. I am happy to find you are well as also all my sisters and brother and their families. I do not get any of your letters only the above date[d]. I would have wrote sooner only we were moveing from place to place and are not settled yet I think. I have no particular news only about the election which will be a hard contest. I hope Little Mc will be the man. I was mustered for pay and as soon as [I] get it will send you some. I must let you know how we are treated as to our rations we are halfe starved not halfe as much as we had one year ago. I have to buy part of my grub, for I cannot eat what is isued to us. Now for breakfast one pint of coffee one cut of bread 1/3 of a loafe and about 4 oz. of poarke, for dinner sometimes poarke and the same quantity of bread. Sup[p]er coffee and 1/3 of a loafe. Only fresh meat once a week and then about 6 ounces but in the mean time I am in good health thank God. You will let Barney know Tom McMahon [enlisted aged 36 in 1861] of the 69th Co. K. is in this Regt. with me and will be going home by next Saturday his time is out he will call to see Barney and you. We are mates together. Now I will conclude by sending you my love hopeing you will enjoy good health till I return also my love to all my sisters and Barney, William Wallace and family,

Write soon,

Your Aff. Son

Charles Traynor

Co. B. 18th Regt. V.R. Corps

Washington D.C. (2)

If Charles had remained in the rear with the 18th Veteran Reserve Corps his prospects of making it through the war would have been bright. That wasn’t to be. He returned to the 69th New York and the front on 5th December 1864, eventually becoming a Corporal in Company F. As the Union continued to press the Confederate positions around Petersburg into 1865, Charles took the opportunity to write home on 13th March. It is clear from the different hand writing in both letters that someone wrote them for him; the use of language and spelling differences between the two examples is also suggestive of a different pen. In this letter Charles seems to indicate that he thought the war might not go on much longer- apparently he could have received a furlough to visit New York, but thought it wasn’t worth doing it until he could go home for good:

Camp Near Petersburg Va.

March 13th 1865

My Dear Mother

I write to you a few lines hoping the[y] will find yous all in good health as I am in at present thank God. I received your letter on the 8th and was glad to hear of yous all been well, Dear Mother. I got 4 months pay and sent you 40 dollors by Adams Express. I hope you have got it before this. I could have got a furlow if I had aplyed for one but I thought it as good to never mind going home untill I go home all together. I trust the Almythy will spear [spare] me my life. The duty is hard enough here we expect to have a moove shortly, give my best love to my brother and sisters and to Mr. Wallice and family. Write soone. Nomore at present from your

Loving Son

Charles Traynor (3)

Twelve days after Charles wrote this letter- on 25th March 1865- the Confederates made their final concerted effort to break through the Union lines at Petersburg. They focused that assault against Fort Stedman on the eastern portion of the line, but despite some initial success, they were eventually repulsed. In response, Union forces further west, including Second Corps units, pressed the right of the Confederate line. That afternoon the 69th New York Infantry were ordered into the woods near Skinner’s Farm (sometimes called Skinner’s House), where they engaged Confederates pickets in what became a sustained firefight. By the time they were relieved a few hours later, they had suffered 94 casualties, nine of whom were killed outright. Corporal Charles Traynor was among the latter, felled by a gunshot wound to the left breast. Having survived some of the bloodiest encounters of the conflict, and having hoped that he would be spared, he ultimately died in the American Civil War’s final days- 150 years ago today. (4)

Lieutenant-Colonel James J. Smith and officers of the 69th New York, an image exposed just a few weeks after the Battle of Skinner’s Farm (Library of Congress)

*The letters above had little punctuation in their original form. Punctuation has been added in this post for ease of modern reading- if you would like to see the original transcription please contact me. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

(1) Charles Trainor Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) New York Adjutant General 1901: 340, Charles Trainor Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (3) Charles Trainor Dependent Mother’s Pension File (4) Official Records: 200-1;

References & Further Reading

Charles Trainor Dependent Mother Pension File WC88894.

New York Adjutant General 1901. Roster of the 69th New York Infantry.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 46, Part 1. Report of Lieut. Col. James J. Smith, Sity-ninth New York Infantry, of operations March 25.

Petersburg National Battlefield

Civil War Trust Battle of Fort Stedman Page

Filed under: 69th New York, Battle of Petersburg, Irish Brigade, New York Tagged: 69th New York Infantry, Battle of Fort Stedman, Battle of Skinner's Farm, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade, Letters of Union Soldiers, New York Irish, Siege of Petersburg

March 24, 2015

Coal Mining, Draft Rioting & The Molly Maguires: From Laois to Schuylkill with the Delaney Family

The Widow’s Pension Files often offer us the opportunity to explore the wider Irish emigrant experience through the lense of a single family. Such is the case with Private Thomas Delaney of the 19th Pennsylvania Cavalry. His family’s story allows us to travel with them, as they journeyed from the coalfields of pre-Famine Laois to the coalfields of 1850s Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. It allows us to follow them through the ups and downs of their personal narrative, even as the township where they lived played centre stage to a wider national narrative of labour organisation, draft resistance and the rise of the Molly Maguires. Ultimately, it ends by taking us from the Pennsylvania Coal Region to a hospital bed in Illinois, as a father hears news from his son.

Mining coal three miles underground in Pennsylvania, c. 1895 (Library of Congress)

Thomas and Catharine Delaney were married by the Reverend Father Grace in Rathaspick, Co. Laois in 1824. Their part of Ireland was known for one particular trade- coal mining. In 1837 an account of Rathaspick’s coal mines and the conditions in which the miner’s worked was recorded:

Here [Rathaspick] are the extensive coal mines of Doonane, worked by a company; they are drained by a steam engine, and supply stone coal to all parts of the surrounding country, which is principally conveyed by carriers. There are about five other works in the same range: the shafts are first sunk through clay, then succeeds a hard green rock, and next slaty strata, in contact with which is the coal: it is worked on either side by regular gangs, each member having a specific duty: the number of each gang is about thirty, and when the pit is double worked there are sixty; each crew works ten hours, but they are particularly observant of every kind of holiday. (1)

Although not stated anywhere, we know from Thomas’s subsequent history that he almost certainly spent decades as a miner in Rathaspick. Through their years in Ireland he and Catharine went on to have twelve children, eight of whom (four boys and four girls) survived to adulthood. Then, in 1854, the couple decided to take their family to America. When they arrived, they didn’t settle among the Irish of urban New York or Philadelphia. Instead they made for rural Pennsylvania, bound for a specific county in the eastern part of the state. Their final destination was Schuylkill County, at the heart of Pennsylvania’s Coal Region. (2)

When the Delaneys arrived in Schuylkill County, they were joining large numbers of their fellow Irish who were working the anthracite coal mines scattered throughout the area. Indeed, a large proportion of the Irish miners in 1850s Schuylkill had emigrated from the coalfields around Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny- only five miles from Rathaspick. As a result, the Delaneys were surrounded by former neighbours and work colleagues who they knew from home. (3)

Almost immediately upon arrival Thomas Delaney went to work in the industry he had come to know so well. He became a miner extracting coal from the Black Heath vein, but within two years of the family’s arrival they already faced a major setback. An explosion in the mine blinded Thomas in one eye, leaving him with only partial sight in the other. Although he was still able to work, Thomas’s capacity to provide for his family would increasingly diminish over the following years. (4)

Minersville, Schuylkill County, as it appeared in 1889. It is a town the Delaney’s knew well (Wikipedia)

The 1860 Census finds the family in the largely Irish Cass Township, Schuylkill County; Thomas and his eldest boys are all recorded as miners. One of the younger boys, Thomas Jr. (recorded as 15 in 1860) was just setting out on his mining career. Sometime that year he started work in the nearby Forestville mine. He joined some 1,590 miners who called Cass Township home in 1860, in a location that has been described as ‘the most turbulent area in the anthracite region throughout the 1860s.’ It would become a notorious location during the Civil War. Part of the reason for this was the fact that the miners were not afraid to organise themselves in order to achieve what they viewed as their working entitlements. This was nothing new; it was likely a propensity for organising themselves that Samuel Lewis was alluding to when he noted in 1837 that the Rathaspick miners were ‘particularly observant of every kind of holiday.’ (5)

By 1862 the miners in Cass Township were fed up, and many went on strike in search of higher wages. The Militia were called in to restart the mine pumps, but were forced to withdraw when they were attacked by rioters. Eventually over 200 troops had to be summoned to quell the situation. Not long afterwards, the Militia Act of 17th July, 1862 authorised the implementation of state drafts to supply the Union with men. Again, Cass Township responded. Up to 1,000 miners marched to a nearby town, where they stopped a train load of draftees heading towards Harrisburg- troops were again needed to quieten the area. The miners were just as angry with their employers as they were with the draft. In December 1862, up to 200 armed men from Cass Township attacked the Phoenix Colliery, beating up a number of men connected with the mine’s operations. The following March, when enrolling officers arrived in Schuylkill to record the names of men in the area for the Enrollment Act draft, they were driven off. One of the officers recalled how ‘it was uncomfortably warm, as the Irish had congregated, and, as we found, were determined to resist, and did by giving us four shots from a revolver (luckily none hitting us).’ Disturbances continued in the region throughout much of the war, and although they were by no means restricted to the Irish community, the Irish were frequently singled out as those culpable. Often exaggerated and almost hysterical reports were being sent to Washington. In July 1863 Brigadier-General Whipple reported that ‘The miners of Cass Township, near Pottsville, have organized to resist the draft, the number of 2,500 or 3,000 armed men.’ He also claimed they were drilling every evening, had artillery, and were commanded by returned soldiers. Eventually, the Provost Marshal sent officials backed with troops to seize the payrolls of mine operators, so their employees name’s could be added to the draft. The events in the 1860s saw the continued rise in Schuylkill County of a secret organisation known as the Molly Maguires, who would dramatically leap to prominence in the 1870s (read more about the Molly Maguires here). (6)

A Coffin Notice allegedly created by the Molly Maguires in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania in 1875 (Wikipedia)

The Delaneys from Rathaspick found themselves in the midst of these turbulent times. We don’t know what their views were, but it would seem likely that they shared many of the concerns of their fellow miners regarding their employers and the draft. Either way, they would have borne witness to life in one of the most agitated areas of the Union during the Civil War. But they also had problems of a more personal nature to consider during this time- chief among them was the death of Catharine Delaney, who passed away on 14th March 1862 in Minersville. Then, after four years in Forestville Coal Company, Thomas Jr. was enrolled in the Union army at Philadelphia on 15th October 1863. The young man became a Private in Company F of the newly formed 19th Pennsylvania Cavalry. That December he and his comrades were moved to Union City, Tennessee. In January 1864 Thomas Jr. was on picket duty in what were bitterly cold conditions. The weather took a severe toll on the men, freezing one of them to death. Both of Thomas’s feet were badly frozen and he was sent to hospital in Mound City, Illinois, his military career seemingly over. That February he wrote home:

U.S. General Hospital

Mound City Feb 9/64

Dear Father,

I now think it near time that I would let you hear from me and how I am. I am here in the hospital with me feet pretty badly frozen, other ways my health is good and I trust in God these few lines will find you in the enjoyment of good health. Let me know how the times are and how you are getting along, let me know if the work is brisk or not and if it is steady. Let me know when you heard from Dennis how he is getting along. We had pretty bad times of it down here and there was a great [number] of the soldiers badly frozen one man of our regiment was froze to death. The Regt has now started on an expedition which is to do some thing great. let me know how is Catherine and Patrick and James Given them my best love and I want you to send me Katys likeness. I dont know what they will do with me here as yet they may discharge me or probably send me to the Invalid Corps. I have not received any pay yet but I expect it about the middle of next month and when I get it I will send it to you. I want you to write to me as soon as you receive this letter.

I will send you all my money except what I want for tobbacco. Give my love to brothers and sisters and all inquiring friends and accept of the same yourself ,No more at present but remains your,

Affectionate Son

Thomas Delaney

PS let me know if John is home yet When you write direct your letter as follows

Thomas Delaney

U.S. General Hospital

Mound City Illinois

Ward J Bed No 17

write soon (7)

The Sisters of the Holy Cross, based in Indiana, served as nurses in the Mound City hospital during the Civil War. Located in a series of warehouses, each warehouse was designated as a ward, with 20 or 30 men assigned to each. On 22nd March 1864, Sister Mary Anne of the Order sat down to write the following letter back to Pennsylvania:

U.S. Genl. Hospital

Mound City Illinois

March 22d 1864

Mr Thomas Delany

Respected Sir,

It is my painful duty to inform you of the death of your son Mr Thomas Delany of the 19th Pa. Cav. which sad event took place in this hospital at four o clock on yesterday afternoon.

It must be a great consolation to you to hear that he died a happy and a holy death. He received all the rites of the church and was fortified by the sacraments in his last moments. He used to speak of you in the most affectionate manner and says it was you that taught him how to say prayers and his catechism. I send you a lock of his hair in memory of him. May his dear soul rest in grace amen. If you write to Dr. H. Wardner the surgeon in charge of Mound City Hospital he will send you his money or any other effects he may have had.

yours very resp.

Sister Mary Anne

A sister of the Holy Cross (8)

64-year-old Thomas Delaney senior was living in Philadelphia in 1867 when he started the process of applying for a pension based on his deceased son’s service. He claimed that all his sons had served in the Union army (it is unclear if this was true or not) and were all now laborers and mechanics. All his children bar his youngest daughter (14-year-old Catharine) were now married. It seems he had left the mining life in Schuylkill County behind, but was living in extreme poverty. His family’s story in America was interwoven with some of the most turbulent years in 19th century Pennsylvanian history, but, more importantly for Thomas, these years were also a period of personal loss, of both his wife of four decades and a beloved son. (9)

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

Mound City National Cemetery. Thomas Delaney Jr. is buried in Plot E 0 3646 (Wikipedia)

(1) Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File, Lewis Topographical Dictionary; (2) Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File; (3) Kenny 1998: 69; (4) Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File; (5) 1860 US Census, Kenny 1998: 86, Lewis Topographical Dictionary; (6) Kenny 1998: 87, 89, 91, 93, Murdock 1971: 44; (7) Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File; (8) Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File, Schmidt 2010: 45-7; (9) Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File;

References

1860 U.S. Federal Census.

Thomas Delaney Widow’s Pension File WC116097.

Kenny, Kevin 1998. Making Sense of the Molly Maguires.

Lewis, Samuel 1837. Topographical Dictionary of Ireland.

Murdock, Eugene C. 1971. One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North.

Schmidt, James M. 2010. Notre Dame and the Civil War: Marching Onward to Victory.

Filed under: Kilkenny, Laois, Pennsylvania Tagged: 19th Pennsylvania Cavalry, Coal Mining Laois, Coal Mining Pennsylvania, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Pennsylvania, Irish Secret Organisations, Molly Maguires, Schyulkill Irish

March 22, 2015

Speaking Ill Of The Dead: Eulogies & Enmity For An Irish Brigade Soldier

On 18th October 1862 the New York Irish-American published an article on the ‘gallant fellows’ of the Irish Brigade who had recently given their lives at the carnage of Antietam. One of them was Tullamore native Lieutenant John Conway, who had fallen in the ranks of the 69th New York Infantry. The paper described Conway as a ‘noble’ man, whose memory should be cherished. Remembering the dead of the American Civil War in such heroic terms is something that we still do today. However, it is occasionally worth reminding ourselves that these were flesh and blood people, with their own flaws and foibles. Just as they were loved by some, they could be disliked by others. Less than two weeks before the Irish-American’s eulogy, John Conway’s brother-in-law, Charles Brady, had written to his sister regarding the soldier’s death. Unlike the newspaper, Charles did not seem particularly sorry to hear of John’s passing. (1)

Antietam Battlefield. The Confederates held the Sunken Lane to the left of the image, with the Irish Brigade advancing from right to left across the field. It was in the vicinity of this field that John Conway died (Damian Shiels)

John Conway had emigrated to the United States from Tullamore, Co. Offaly around the year 1840. On 7th January 1846 he had been married to Catherine Brady in Auburn, New York, by Father O’Flaherty. The couple, who had no children, appear to have tried their hand at farming before heading to Brooklyn. There they entered the employment of Henry C. Bowen, a successful New York merchant. Bowen was the Internal Revenue Collector for the Third District (Brooklyn), but was also a prominent abolitionist. He had founded The Independent in 1848, a congregational antislavery weekly that at one point was edited by Henry Ward Beecher. John worked as Henry Bowen’s gardener while Catherine served the family as a nurse. The Offaly man was around 36 years old when he became a Lieutenant in Company K of the 69th New York in 1861. At the time he was described as 5 feet 10 inches in height, with a dark complexion, dark eyes and black hair. 34-year-old Catherine was still in the Bowen’s employ when she learned that the Battle of Antietam had made her a widow. (2)

John Conway’s body was brought back from Maryland together with that of Patrick Clooney, one of the most famed officers in the Brigade’s history. Their remains were ‘conveyed in handsome metallic coffins’, and taken to the headquarters of the Brigade at 596 Broadway where they were laid in state. John Conway had clearly been a good soldier. The Irish-American reported that he had:

‘served with distinction and honor on every battle-field to the hour of his death; when, like many of his brave companions, he was struck down, on the 17th of September, at Antietam, leading his command to the charge. Courteous, affable, loving and truly brave- he was as much beloved in social life by all who knew him, as in camp by his fellow-officers, who esteemed him as a “noble fellow,” and mourn him to-day as an irreparable loss. Aged but thirty-six years, his young life is another sacrifice of Ireland for America, in the annals of which, as a staunch and trusty soldier, the name of John Conway should be cherished.’ (3)

Henry C. Bowen’s newspaper ‘The Independent’, as it appeared in 1919 (Wikipedia)

Catherine Conway was living with the Bowens at 76 Willow Street in Brooklyn in 1862. She needed to prove her marriage to John in order to become eligible for a pension, so she asked her brother, Charles Brady, to travel to Auburn to see if he could get evidence of the marriage. Charles was a farmer living in Skaneateles, Onondaga County. When he wrote back, Charles took the opportunity to offer his own form of consolation to his sister. His letter makes it clear that John’s ‘bad actions’ had severely damaged Charles’s opinion of him. Charles did not even feel it was worth Catherine trying to get John’s body home, although as reported by the Irish-American this is something that would subsequently take place.Charles also made sure to tell his sister to avoid the ‘low Irish’ who might lead her astray, and encouraged her to stay living with the Bowens:

Dear Sister

I received your letter the third. We were very sorry to hear of John deaths [sic.], I don’t blame you to feel bad but still he was so cruel to you, but I suppose nature comples [compels] you to feel so. Dear Sister I don’t think he ever used you like a husband when you lived up on the lake [presumably Lake Skaneateles] on the farm, you know when you had to go out and milk all the cows and he would be away playing cards, and since yous went east by all accounts he was but worse and after he went away Mother wrote to me and told me that he never left you a dollar after selling all his things. When he was up here he had plenty of money spending around the taverns and was out at Auburn at two Irish dances but I will forgive him and I hope God will for all his bad actions. Dear Sister there had been many a good husband left their wives and children which falls on the field of battle and their family’s must feel reconcilise [reconciled] now. Dear Sister you have know [sic.] trouble but yourself and as the Almighty gives you health you aught to be well satisfied and also you aught to feel happy to think you are living with such kind folks that takes so much interest in you. Dear Sister now I am going to give you advice to keep away from all the low Irish and not be led away by them, you may think they are for your good they will bring you to ruin. Dear Sister I hope you will remain with the family you are living with and be said by then the advice you get from them will be for your good. Dear Sister I went out to Auburn yesterday to see about your marriage lines the priest that is there now his name is Mr Creaton [?] he is the third priest since you were married. This priest can’t find the record that priest had that married you, that shows how correct they are about keeping the record. This priest says as long as yous lived man and wife for so many years and there is plenty of witnesses for that. Dear Sister if you will live with this family my wife or myself will go down to see you the latter part of the winter for I know you have got a good home with them. Dear Sister I think it is so foolish to think to get John [‘s] body home for they can’t tell one from the other after they are three days under the sand. Them that are advising you for that are doing you wrong you take advice from Mr Hodge and not from them, for he knows all about such business. If there is anything coming to you he will get it for you, if you get anything put in the bank for old age. Myself and family joins with me in sending their love to you. I have no more to say at present but remain your affectionate brother,

Charles Brady.

Skaneateles Oct the 5 1862. (4)

It transpired that the priest that had married John and Catherine, Father O’Flaherty, had returned to Ireland. However, statements from family members and Henry C. Bowen were enough to prove the marriage and secure Catherine’s pension. It would later be increased by special act. Catherine’s opinion of her husband goes unrecorded, but it likely sat somewhere between the glorified memorialisation exhibited by the Irish-American and the extremely low opinion of him held by her brother Charles. Catherine received a pension based on John’s service until her own death in 1905. She was buried with her fallen husband at St. Patrick’s Cemetery, in Aurora, New York. (5)

Report to the Senate supporting an increase in Catherine Conway’s pension (Fold3/NARA)

*The letter above had little punctuation in its original form. Punctuation has been added in this post for ease of modern reading- if you would like to see the original transcription please contact me. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

** I would like to acknowledge Lyndsey Clark, Sharon Greene-Douglas, Robin Heaney, Tadhg Williams, Robert A. Mosher, Craig Swain, Joe Maghe, David Gleeson, Harry Smeltzer, Iain Banks, Don Caughey and Joseph Bilby for assisting with the transcription of the Charles Brady letter.

(1) New York Irish American Weekly 18th October 1862; (2) John Conway Widow’s Pension File, McPherson 1975: 25; (3) New York Irish American Weekly 18th October 1862; (4) 1860 Census, John Conway Widow’s Pension File; (5) John Conway Widow’s Pension File;

References & Further Reading

John Conway Widow’s Pension File WC2415

1860 U.S. Federal Census

New York Irish American Weekly 18th October 1862. The Dead of the Brigade.

McPherson, James M. 1975. The Abolitionist Legacy. From Reconstruction to the NAACP.

Civil War Trust Battle of Antietam Page

Filed under: 69th New York, Battle of Antietam, Irish Brigade, New York, Offaly Tagged: 69th New York Infantry, Bloody Lane Antietam, Civil War Memory, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Antietam, Irish in New York, Irish in Onondaga, Offaly Veterans

March 18, 2015

Selling ‘Ireland’ and Forgetting the ‘Irish’? Some Thoughts on the Taoiseach’s St. Patrick’s Day Speech

This week Ireland’s Taoiseach, Enda Kenny, visited America for St. Patrick’s Day. Each March, our small country enjoys exceptional treatment on the other side of the Atlantic, treatment which includes a meeting with the President of the United States at The White House. Ireland’s relationship with the U.S. is the envy of other small countries. That relationship is almost entirely based on the affinity that many Americans hold for Ireland as a result of their own ancestry. In other words, Ireland has its past emigrants to thank for the extraordinary access and coverage we enjoy annually in one the world’s largest nations. It seems to me, however, that in our eagerness to use these opportunities to sell ‘Ireland’, we are consistently forgetting to remember the ‘Irish.’

An Taoiseach Enda Kenny with President Barack Obama in The White House (Wikipedia)

As might be expected, Ireland uses the opportunity presented every March to ‘sell Ireland’ as a country to the United States and to Irish-Americans. There is nothing wrong with this. However, I am increasingly concerned that ‘selling Ireland’ is now in danger of becoming the driver behind nearly all our interactions with the diaspora. Official Government visits abroad make constant efforts to tell everyone why they should visit Ireland, and remind them of events (or anniversaries) which are being promoted and highlighted in order to encourage tourism. However, all too often the concentration on ‘Ireland’ is myopic in its intensity. Rarely in our engagement with the diaspora do we seek to include or remember the ‘Irish.’

To remember the ‘Irish’ as opposed to simply ‘Ireland’ is to include all those Irish who made new homes around the globe- the very genesis of the diaspora itself. We can count ourselves somewhat fortunate that the desire for many among the diaspora to support our country is so strong that this focus on ‘Ireland’ rather than the ‘Irish’ tends to go largely unnoticed. However, it remains to be seen if this is something that will hold true in the future. It is my view that the speech delivered by the Taoiseach at The White House is a clear demonstration of this focus on ‘Ireland’ over the ‘Irish.’

On Tuesday, the Taoiseach took the opportunity to reference three anniversaries- two centenaries and a sesquicentennial:

‘In Ireland, we are in a decade of commemorations, marking the hundredth anniversary of the tumultuous events that resulted in our independence. Next year we will commemorate the anniversary of the 1916 Rising in Ireland and around the globe, including a major festival here in Washington at the Kennedy Center. This year is also the 150th anniversary of the birth of the great poet WB Yeats. We will be marking that in many events throughout the year in Ireland, here in the US and around the world.’

The Irish Times coverage of the event noted that the poems chosen by Ireland for the presentation to President Obama were selected to ‘acknowledge the first World War and next year’s centenary of the 1916 Rising, as well as Yeats 2015, the year-long celebration of the poet’s 150th anniversary.’ All three of these anniversaries are strongly ‘Ireland’ focused. One could ask, was there any other anniversaries that it might have been appropriate to mention?

The Taoiseach’s speech was delivered in the United States, in the year of the 150th anniversary of the conclusion of the American Civil War. This is a conflict in which tens of thousands of Irish emigrants lost their lives; many of them being part of the emigrant wave who were among those who laid the foundations for the development of that special relationship which the Taoiseach was in Washington to celebrate. But our focus was on the 150th anniversary of the birth of one our (admittedly greatest) poets.

As regular readers are painfully aware, I (and others) have spent many years attempting to get the Irish Government to do something to acknowledge the impact of the American Civil War on Irish emigrants. After many disappointments, finally, last November, the Minister for Arts, Heritage & the Gaeltacht made specific reference to the impact of the American Civil War on the Irish at a speech in Tulane University, New Orleans. With renewed encouragement, a number of highly respected historians and I wrote a letter to the Department in the hopes that some small event might now be possible. After all, here is a conflict that impacted Irish people at a similar scale to World War One. Unfortunately, after almost three months, we have yet to receive a response (you can read more about these efforts at Professor David Gleeson’s blog here), though we remain hopeful something positive may yet come from it.

That the 150th anniversary of a war that led to the deaths of tens of thousands of Irishmen once again fails to draw a mention from the Irish Government does not surprise me quite so much as the decision to specifically mention the 150th anniversary of the birth of W.B.Yeats in this setting. It is difficult not to draw the conclusion that the anniversaries chosen for mention were done so explicitly to ‘sell Ireland.’ The 150th anniversary of the birth of W.B. Yeats has thus far received significant financial support from Government, and is the focus of considerable attention from a number of State bodies. Yeats was indeed one of our greatest poets, and deserves attention. In contrast, the 150th anniversary of one of the biggest tragedy’s in the history of the Irish diaspora (and indeed the Famine diaspora) has thus far received no financial support and no acknowledgement beyond the Minister’s reference in New Orleans. To mention one to the exclusion of the other in the United States, on the final occasion in which the anniversary could be marked by the Taoiseach in America, was for me disappointing. If Ireland really does have a genuine affection for the history, heritage and experiences of our global diaspora, perhaps it is time we begin to mix our efforts to promote Ireland with a more keen awareness of the global experiences of the Irish people. What do you think?

Filed under: Discussion and Debate Tagged: Irish American Civil War, Irish American Heritage, Irish American History, Irish Diaspora, President Barack Obama, St. Patrick's Day, Taoiseach Enda Kenny, Taoiseach White House

March 17, 2015

‘Quite A Merry Time': A Union Irish Soldier Describes His Last St. Patrick’s Day, 1863

On 17th March 1863 David O’Keefe, a cabinet-maker from Co. Cork, celebrated St. Patrick’s Day in Virginia. Some six months previously David had left his adopted home of Reading, Massachusetts, to join the Irish soldiers of the 9th Massachusetts Infantry at the front. He wasn’t a young man- by the time he enlisted he was 44-years-old. The Corkman had taken his wife and young family out of Ireland at the time of the Famine, and now, a decade later, was fighting for the Union. A few days after the festivities, David dictated a letter describing the St. Patrick’s Day events. It would prove to be the last time he celebrated the feast of the patron saint. His letters home are published here for the first time since they were written in 1863. (1)

The 9th Massachusetts Celebrate Mass in 1861 (Library of Congress)

David O’Keefe had married his wife Catharine in Co. Cork in 1842. The couple had two sons, both of whom were born in Ireland. The eldest, David Jr., was born around 1843, with Cornelius following in 1846. By 1853 they had joined tens of thousands of other Irish Famine emigrants in Massachusetts, but despite escaping the ravages of Ireland they still faced hardship. On 20th June 1853 they lost seven-year-old Cornelius to scarlet fever- the young boy was buried in Dorchester. By the 1860s the O’Keefes were living in Reading, where they were part of a community that included many of their old neighbours from Cork. Every day David walked 12 miles from his home to the Boston workshop where he was employed. Friends remembered how he ‘would do more work at his trade than most of the men who worked with him.’ Then, on 12th August 1862, David decided to put aside cabinet-making and don Union blue. (2)