Damian Shiels's Blog, page 40

January 5, 2015

The #ForgottenIrish of Co. Sligo

The latest #ForgottenIrish story looking at Co. Sligo is now available on Storify. It is the sixth county to be examined, joining Cork, Kerry, Donegal, Galway and Cavan, with Dublin to follow shortly. Storify also has a piece looking at Civil War Pensioners in Ireland. If you would like to read the Sligo Storify you can do so by clicking here.

Filed under: Digital Arts and Humanities, Sligo Tagged: Civil War Pension Files, Digital Arts & Humanities, Forgotten Irish, General Michael Corcoran, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, Sligo American Civil War

December 29, 2014

Robert Fisk on the Irish in the American Civil War

Since I started writing about the Irish in the American Civil War I have had some interesting readers. One of the more unusual has to be Cher, who reportedly read my book on the topic. Yesterday I discovered that the award-winning, internationally renowned journalist Robert Fisk wrote a piece for the English Independent newspaper entitled A timely reminder of the bloody anniversary we all forgot, which you can read here. The column deals with the American Civil War, and particularly the extent of Irish involvement. The inspiration for Fisk’s piece came from a short article called Ireland’s Forgotten Great War which I wrote for An Cosantóir, the excellent magazine of the Irish Defence Forces. Although Fisk is not Irish, he has a longstanding interest in Irish history and politics and so is a subscriber to the magazine, which he has delivered to his home in Beirut, Lebanon. It goes to show you never know who will be reading what you write! Hopefully Fisk’s piece will add further fuel to the growing clamour for the Irish State to take some action in 2015 to appropriately remember her people’s involvement in the American Civil War.

‘Pity the Nation’, Robert Fisk’s award-winning book on the war in Lebanon

Filed under: Media Tagged: An Cosantoir, Battle of Cedar Creek, Irish American Civil War, Irish Civil War Veterans, Irish Defence Forces Magazine, Irish Diaspora, Pity the Nation, Robert Fisk

December 28, 2014

An Appearance on C-Span’s American History TV

I recently shared the full text of my Keynote Address which I was privileged to deliver at the 2014 Tennessee Civil War Sesquicentennial Signature Event in The Factory, Franklin last November. The event was organised to mark the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Franklin. In the Keynote I discussed the life, legacy and death of Patrick Cleburne, along with the stories of a number of other Irishmen who were involved in the engagement. C-Span were in attendance to record proceedings, and they recently broadcast the full address of c. 50 minutes. For anyone interested, it is now available to view on their website which you can access through this link or by clicking on the image below.

Patrick Cleburne & The Battle of Franklin- American History TV

Filed under: Cork, Tennessee Tagged: American History TV, Battle of Franklin, C-Span, Irish American Civil War, Irish emigration, Irish Generals, Irish in Tennessee, Patrick Cleburne

December 24, 2014

Stuck for Last Minute Christmas Gift Ideas? Some Suggestions & Advice From 150 Years Ago

Today is Christmas Eve, and for many of us that means a final dash to the shops as we seek out those last few gifts. If you are struggling for ideas, why not take some of the suggestions and advice offered to readers of the New York Irish-American, 150 years ago in December 1864. Remember, nothing says I love you like a Clothes Wringer!

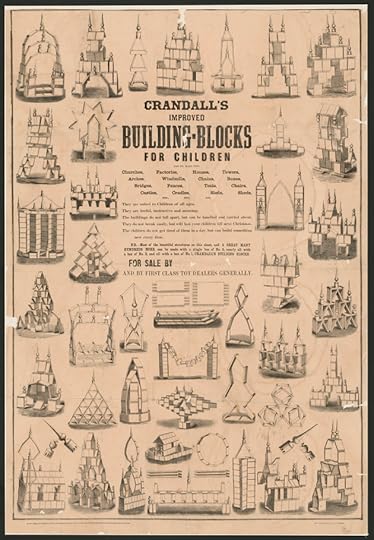

‘Something useful and diverting': Crandall’s Building Blocks for Children c. 1867 (Library of Congress)

A HOLIDAY PRESENT.- What shall it be?- For the child, something suited to the sex, useful and diverting- not for the moment only, then to be cast aside- but that will link year with year, and mark and improve the character. For an adult of either sex the variety is endless, suiting the infinity of circumstances. The mother and head of a family has learned to prize most what lightens the household burden and betokens affectionate sympathy: a Baby-Tender, a Washer, Wringer, or a Wheeler & Wilson Sewing Machine.- The first are winning their way to public favor; the last is old and well tried. There is no question of its utility and suitableness as a present of affection and charity. Its low-toned voice will prove a sweet reminder of friendship and effective sympathy, and mingle with the hymn of thankfulness. Try it for your wife, or the widow toiling for the support of her children. (1)

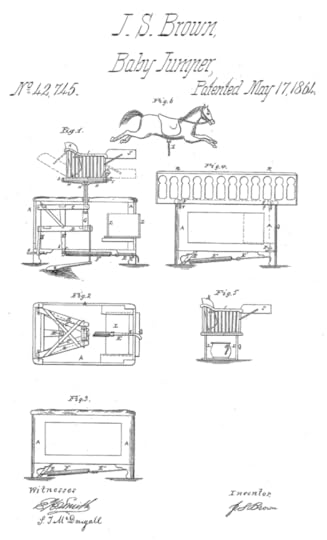

‘Winning their way to public favor': The original 1864 patent drawings for Dr. Brown’s ‘Baby Tender’ or ‘Baby Jumper’. It had a spring to provide and up-and-down motion for the child. The drawings show the different fittings that could be placed on it, from a chair, to a cot and even a hobby-horse (Google Patents)

Many thanks to everyone for reading and contributing to the Irish in the American Civil War site in 2014, and wishing you all a Merry Christmas and New Year.

‘A sweet reminder of friendship and effective sympathy': A woman enjoying her new sewing-machine, c. 1853 (Library of Congress)

(1) New York Irish-American 31st December 1864

References

New York Irish-American 31st December 1864. A Holiday Present. What shall it be?

Filed under: New York Tagged: 19th century Christmas, Brown's Baby Tender, Crandall's Building Blocks, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish emigration, New York Irish-American, Wheeler & Wilson Sewing Machine

December 23, 2014

‘Strange Soil Your Doom': Advice on How to Prepare for Emigration in 1863

In the Spring of 1863 the Reverend John Dwyer of Dublin penned a series of three letters to the New York Irish-American newspaper. Entitled ‘Hints to Irish Emigrants’, each was themed to provide advice for different stages of the emigrant’s journey from Ireland to America- what to do before you left, what to do while on the voyage, and what to do upon your arrival. Unsurprisingly, there is a strong religious flavour to the advice; neither do the letters leave the reader in any doubt as to Dwyer’s views on who and what was causing Irish emigration. But the letters also provide practical suggestions, such as what food to pack and what to expect of your new life. They demonstrate how common chain-emigration was, and also allude to the risks that female emigrants faced on their journey.

Irish Emigrants Leaving Caherciveen, Co. Kerry for America (Library of Congress)

The Streets Are Not Paved With Gold. The first letter was published on 7th February 1863. In it Reverend Dwyer discusses his views on how English misrule has led to sustained emigration, and cautions prospective emigrants to be sure that the people sending for them from America are trustworthy. He reminds those considering emigration just how tough it will be to make it a success. They should prepare themselves spiritually for the journey, and also make efforts to remain temperate:

Having for many years studied and learned from various sources that appertained to the prosperity, or, destroyed the prospects of Ireland’s children, banished from their parent homes by tyranny and misrule, I deemed it important to publish in a few letters a portion of my information, for the benefit of the emigrants and their sorrowing friends. I shall simply state what is to be done before leaving; what on the voyage, what on arriving, and how prosperity may be secured in obtaining a situation and learning how to keep it. For several months I have made this a special study, both in Ireland and America; and hence I feel confident that every one anxious about their friends, will read with satisfaction my remarks, or statement of facts, as they tend so much to the spiritual and temporal advantage of any and all leaving the land of their birth, and the hallowed martyr soil of saints. What is to be done before leaving? If you cannot remain at home, ascertain who sends for you, and from what motives, and for what occupation. Relations have sent for relations very near to them, and misery and destitution were the reward of the long voyage. Trust not flesh and blood, without a due inquiry, either when urged to leave home, or when you reach the foreign shore. Ascertain through some clergyman or trustworthy person what is the occupation of the party who writes for you, lest you fall into a snare. This advice is more particularly intended for young females emigrating without a faithful and virtuous protector. Next, remember this: the streets are not paved with gold. Hard, hard work, and real industry, you must place before you if you desire to succeed. A large and wealthy city is not a sudden fortune for you. You must work up the hill, or you will fall down. Many have been mistaken, thinking to themselves, “my fortune is made, for I am going abroad.” No such thing. No work no pay. All must work and persevere in watchfulness. Many were ruined by not knowing or not following these suggestions. As to your spiritual preparation, remember you will not have too much time to attend to your religious duties, and hence, learn all you can before you emigrate. False notions of liberty in a free country gradually undermine humility, docility and obedience, and hence a good stock of humility and docility will be a strong shield for your spiritual and temporal welfare. Learn virtuous neatness, but put under foot all notions of vanity and showy dress. These have been the cause of ruin to so many, who, if modest and retiring, would be highly respected, and would rarely, if ever, be out of situation. Secure the Sacrament of the Soldier of Christ to stand firm for your religion, and let Confirmation guard you against the enemies of the Church. Some weeks before departure fortify your souls with Confession and Communion. When on the wide and stormy ocean, then, indeed, you will wish to have a priest. On my passage from Ireland to America, oh! how anxious were the emigrants to confess with all the fervor of their heart and soul. You may not have a priest. A wealthy Catholic said some time ago he would give thousands of pounds to confess to a priest when in the midst of a terrific storm. Provide in time for the dangers of land and sea. Be resolved to be temperate. How many here might be happy and comfortable if they were moderate, and more, they could have sent home a deal of money.

Keep God always before your eyes, and in your hearts, and remember you know not how thousands of temptations may crowd upon you. Pray fervently and often, “Father of Mercy”-“lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil”- “our eyes from sinful objects, our ears from evil discourses, all our sences from every poisonous breath of sin.”

I remain your affectionate countryman,

JOHN DWYER. (1)

On Board an Emigrant Ship (Library of Congress)

Female Emigrants, Cling to Each Other, and Protect Each Other. Reverend Dwyer’s second letter, published on 21st February 1863 and written in New York, offered advice with respects to the voyage, much of it practical suggestions with regard to foodstuffs. It is particularly focused on how women might avoid ‘insult’ while on the journey, suggesting that the harassment and assault of female emigrants during their passage was an all too common occurrence:

New York, Feb. 12, ’63

In my first letter I stated what was to be done before you were driven from your native soil, to your hoped for better condition on a foreign shore, away from petty tyrants, or absentee, or penniless, or screwing landlord, or all combined together. Who does not know that every bad landlord in unfortunate Ireland may, if he so wishes, suck the blood of every tenant? Then their spies and creatures. Some landlords of Ireland have forgotten the 5th, 6th and 7th commands of God. 1st, not to murder, 2d, not to commit adultery, or make others do the same; and 3d, not to drive people to steal; yet in their pride they force into temptation; but pray to God for patience and resistance against all their temptations.

Oh, mercy, mercy on our land,

So poison’d by the triple hand

Of Saxon, demon, landlord brand.

You leave your home, not at my suggestion, but forced by cattle dealers and bad landlords. Then, what are you to do before you start, and on your journey?

1st. Be guarded against a dangerous error and temptation- that notion of a foreign land, that weeping and parting from friends, easily led into every dramshop, where your future prospects in life may be entirely destroyed. On such occasions, pray, “Lord, deliver us from false friends.” Beware of overkindness- that will destroy you. Be calm, steady, and sober, and face your journey with God and a clear conscience.

2d. What are you to bring with you? Bring what you can, just as if you knew not what you were to get on board. The company will supply you according to agreement, but that will not do for your private demands. Tea, coffee, biscuits made of good flour, and well baked, and also a supply of soda powders, will make the journey pleasant and healthful, and enable you to save money. Some nice salt butter, and buttered eggs, would be very good. Bring with you what will enable you to steer clear of difficulties, just as if you were a cabin passenger. No cabin or steerage passenger should travel without their own private resources. You will feel the want of milk; if you have eggs, they will do; if you have not, boil some fresh milk, before leaving, with good sugar; let it cool, and bottle it air-tight. As to loose money, the less you have the better, unless for necessary expenses, or to make some purchase.

3d. Bring with you what will enable you to keep clear of all men’s compliments. Here, in America, no man dare insult a female, and would to God we could say the same of every other country. Female emigrants, cling to each other, and protect each other, for if you do this, you need not fear a second insult, and if repeated, you can easily tell one of the leading officers on board. We hear very few complaints from Germans, French, or others, of being insulted, and this because they cling to each other and protect each other. I have seen it myself, and have been told by priests, travellers, and seamen, young females will not be insulted a second time if they mind themselves and apply to proper quarters on board vessel. Mind yourselves and God will guard you.

4th. When you go aboard, do something useful. Make your berth comfortable and clean, and beware of taking too much mixed food, & c. Turn to the fresh breeze, and keep in the open air as much as possible, if you want to escape sea-sickness. Sew, knit, and chat amongst yourselves, and thus the voyage will be pleasant and useful. Have a supply of good books- and amongst them, Irish and English catechisms, such as you have learned. Labor keeps out vice.

Your affectionate countryman,

JOHN DWYER. (2)

Immigrants landing at Castle Garden, New York (Library of Congress)

Strange Soil Your Doom. The final letter was published on 28th February 1863 and relates to the emigrant’s arrival in New York’s Castle Garden, which served as America’s first official immigration centre from 1855 to 1890. It cautions people not to forget those they left behind as they marvel at the wonder of their new surroundings. It also alludes to the dangers of those who would seek to prey on new arrivals, and cautions that you should avoid ‘tract distributors.’ The importance of quickly locating your friends in this new country is also highlighted:

New York, Feb. 24, ’63

Having briefly suggested in my two former letters what you were to do on leaving home, and what during your voyage, I must now speak of your arrival on a foreign shore. On seeing (as you imagine) a land of promise flowing with milk and honey, after tossing on the ocean, you may exult and forget, in your joy for the hour, friends left at home, and perhaps even a father or a mother in the dismal workhouse. Then, indeed, you should be wide awake, and watch and pray most fervently,- then you must cling to your good angel for protection and only rely on those you are quite sure of. Even relations and former friends are to be measured with a discerning eye.- This observation was made by persons long residing in a foreign land. What were emigrants before now passing from Ireland to England to stop there for a few days? The history is a sad one, and I need say no more. Till public shame forced the authorities to appoint proper agents, there was but little protection for female honor, and unless trustworthy and responsible persons are appointed for you, emigrants, to every part of the globe, is there not great risk of scandal, and, perhaps, ruin. The duty of such agents- be they Catholic chaplains or steady laymen- would be to look after you on board, and protect you when you land. If you can discover assured protection you know your course. No man of propriety would trust his daughter to a mixture of unknown strangers. I hope in God the various companies will take notice of these remarks, and if it has been an oversight for the past, I am sure they will consider the matter for the future.

Before leaving, dear emigrants, you must watch yourselves. On the voyage remember your pious home, and on arrival do not forget Saints Patrick and Bridget- their virtues and their crowns. There is but one place here affording State protection, and that is in New York. Castle Garden is appropriated for the safety of all emigrants arriving in the State of New York, but otherwise you have no claim on Castle Garden. I have gone frequently to that establishment to see the newly arrived emigrants, and to receive information from the officers and emigrants of many countries, so as to communicate what may have been written before, but what never reached you. You may meet there tract distributors, but a deaf ear is a very silent reprimand. If they annoy you, tell the officers. Have your direction and papers ready, and means also, to go at once to your friends. I have seen some who either lost or forgot their direction, and what were they to do? Some came expecting to meet a brother or father, and did not find them. Follow these hints, and the officers of Castle Garden will do their duty. They are paid officers of high integrity, with the feelings of a brother for every emigrant placed under their protection. They ask nothing from you but to allow them to act as well-instructed parents to their dear children, to save you from all harm. Through them you can procure situations. You need not be long idle if you follow your instructions. Go nowhere without their knowledge. Leave your luggage in their hands.

You left your home from tyrant gloom,

To brave the land and sea;

Strange soil your doom, strange soil your tomb,

But God is full of mercy.

May God bless you and your protectors.

Your affectionate countryman,

John Dwyer. (3)

Registering Emigrants at Castle Garden (Library of Congress)

(1) Irish-American 7th February 1863; (2) Irish-American 21st February 1863; (3) Irish-American 28th February 1863;

References

New York Irish-American 7th February 1863. Hints to Irish Emigrants. By the Rev. J. Dwyer, Dublin.

New York Irish-American 21st February 1863. Hints to Irish Emigrants. Second Letter from Rev. J. Dwyer.

New York Irish-American 28th February 1863. Hints to Irish Emigrants. Third Letter from the Rev. J. Dwyer.

Filed under: Dublin, New York Tagged: 19th Century Emigration, Castle Garden, Hints for Irish Emigrants, Irish American Civil War, Irish Diaspora, Irish Immigration, New York Irish, Preparing for Emigration

December 18, 2014

‘In the Midst of Sorrow': An Irish-American Sailor’s Fate, Christmas Eve, 1864

The Christmas period tended to be a tough one for working-class New Yorkers in the 1860s. The seasonality of many laboring jobs and an increased cost of living caused by heightened fuel consumption saw many families struggle. Between 1861 and 1865 many had the added burden of worrying about a loved-one at the front. This was no different for elderly Irish couple Francis and Jane Duffy, who made their home among the East 12th Street community in Manhattan. Unfortunately for them, Christmas 1864 was one that they would remember for all the wrong reasons. (1)

St. James’ Church, New York, where Francis and Jane Duffy were married (Wikipedia)

Pre-Famine Irish emigrants Francis and Jane Duffy had married at St. James’ Roman Catholic Church on 10th December 1843. Their first-born child James was born 10 months later, on 11th October 1844. He was baptised two days afterwards at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in the Lower East Side. We don’t know too much about the family’s life in the years that followed, other than the fact that they became a fixture of life on East 12th Street over the course of the following two decades. As the 1850s progressed, increased age combined with years of physical labor began to catch up with Francis. Rheumatism and worsening deafness meant that he had to reduce the hours he worked, a slack taken up by his son James. By the summer of 1864, Francis had ceased working entirely. James, now 20-years-old, was earning up to $10 per week and giving much of that to pay to provide food and clothing for his parents, as well as to pay their rent at 259 East 12th Street. (2)

St. Mary’s Church, New York, where James Duffy was baptised (Wikipedia)

Whatever his motivation- it would seem most likely that it was regular pay- James Duffy entered the New York Naval Rendezvous on 1st March 1864 and enlisted in the Union Navy. His lack of previous maritime experience meant that he was assigned the rank of Landsman. The new recruit, who had signed on for one year, was described as being 21-years-of-age and 5 feet 7 1/2 inches tall, with a fair complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. The young Irish-American was assigned to U.S.S. Ticonderoga, a sloop-of-war that spent time that summer hunting the Confederate raider C.S.S. Florida before joining the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron off Wilmington, North Carolina towards years end. (3)

The Ticonderoga was there because the Federals had determined to close-off the South’s last major Atlantic port at Wilmington- but to do this they first had to neutralise the formidable Fort Fisher, which commanded the Cape Fear river. The task of taking Fort Fisher was to be a combined army and navy operation under the command of Major-General Benjamin Butler and Rear-Admiral David D. Porter respectively. When a plan to destroy part of the fort by detonating a ship packed with explosives beside it failed, Porter’s fleet began a large-scale bombardment of the Confederate positions. On Christmas Eve 1864, one of the vessels that began pouring thousands of shells into Fort Fisher was James Duffy’s U.S.S. Ticonderoga.

U.S.S. Ticonderoga, April 1864 (Naval Historical Center)

The Ticonderoga‘s Captain, Charles Steedman, gave the order to commence firing at Fort Fisher shortly after 2.30pm on 24th December. Landsman James Duffy was assisting with the operation of one of the ship’s 100 pounder Parrott Rifles. At around 3.15pm, some 45 minutes into the action, Acting Lieutenant Louis G. Vassallo was standing at the gun breach, in the act of sighting the weapon, when suddenly it erupted into fragments, sending huge shards red-hot metal flying about the ship. Vassallo somehow survived, albeit with severe facial injuries. Many of his comrades were not so lucky. It is probable that James Duffy never knew much about the explosion- the ship surgeon would later recall that the young man’s ‘head and arm was blown off’ by the violence of the blast. A total of 8 sailors were killed and 12 wounded when the barrel burst, many of them Irish. The occurrence was an all too common one during naval bombardment, and the fate of the men threatened to demoralise the other sailors. Captain Steedman recalled how it had a ‘depressing effect’ on the rest of the Ticonderoga’s compliment. As shocked crewmen looked on, sand was scattered about the deck to absorb the blood of James and the other victims. Then Coxswain William Shipman, who was commanding a nearby gun, shouted encouragement to the remaining gunners: ‘Go ahead, boys; this is only the fortunes of war!’ With that the others shook themselves from their shock and recommenced firing at Fort Fisher. Shipman would later receive a Medal of Honor for his inspirational actions. (4)

The Fort Fisher expedition leaving the Chesapeake, December 1864 (Library of Congress)

The efforts of the U.S.S. Ticonderoga and the others vessels had little impact on Fort Fisher that December, and a half-hearted and abortive effort by Butler to assault the position with his ground forces on Christmas Day ended in withdrawal before any serious combat had taken place. It would be the middle of January before a second engagement would finally secure the fort. In the intervening period, Captain Steedman sat down, on 31st December, to write the following to Francis Duffy:

U.S.S. Ticonderoga

Off Beaufort N.C.

December 31st 1864

My Dear Sir,

It becomes my painful duty to inform you of the death of your son Francis Duffy who was killed on the 24th Instant by the accidental twisting of a gun during the attack upon Fort Fisher. In the midst of sorrow- comfort and strength cometh only from Above yet it is gratifying to know that he died while gallantly performing his duty in battle.

I am, Dear Sir,

Your Obed. Servt

Chas Steedman

Captain

Mr. Frances Duffey

259 E. 12th St

New York (5)

Jane Duffy immediately applied for a dependent mother’s pension based on her son’s fate. The couple appear to have consistently sought to remain on or near East 12th Street and the community they knew so well, though they were more than prepared to move around within that area. Not long after their son’s death the couple moved from No. 259 to No. 525 East 12th Street. Friends and neighbours came forward to give statements on their behalf, such as John Brennan of No. 530 East 12th Street, and Patrick McFadden of No. 549 East 12th Street, who both stated they had been neighbours of the Duffy’s for twenty years. Jane’s pension application was successful, and the couple, who’s only property was the few pieces of furniture they moved around with them, had some measure of security once again. (6)

A damaged Confederate gun in Fort Fisher (Library of Congress)

Jane eventually passed away on 5th March 1877. Francis, who was now more or less completely deaf and in his late seventies, had to rush to secure the transfer of the pension to him as a dependent father. Within a week of his wife’s death he was making a new statement with regard to his son’s naval service and his own physical condition. His address was now No. 522 East 13th Street- although those who gave statements on his behalf included yet another East 12th Street resident, Thomas Jones of No. 407. (7)

Thankfully Francis was granted his pension from the date of his wife’s death. It is not clear how long he lived to enjoy it. Christmas Eve 1864 had seen the Irish couple lose their first-born child in awful circumstances, an event that plunged them into severe financial uncertainty. Their dependent parent’s pension file gives us an insight into just how vital a child’s support could be to parents, particularly if they were elderly and infirm. It also demonstrates how Irish and other communities based around areas such as East 12th Street could rally to support of their own. (7)

An unidentified Union Sailor (Library of Congress)

(1) Widow Certificate; (2) Ibid.; (3) Naval Weekly Returns, Widow Certificate; (4) ORN: 327-8, Fonvielle 2001: 137-8; (5) Widow Certificate; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid.; (8) Ibid.;

References

James T. Duffy Navy Widow Certificate #2247

Naval Enlistment Weekly Returns

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Volume 11. Report of Captain Steedman, U.S. Navy, commanding U.S.S. Ticonderoga

Fonvielle, Chris Eugene 2001.The Wilmington Campaign: Last Departing Rays of Hope

Filed under: Battle of Fort Fisher, Navy, New York Tagged: Captain Charles Steedman, East 12th Street, First Battle of Fort Fisher, Irish American Civil War, Irish in the Union Navy, Irish of New York, Jack Tars, USS Ticonderoga

December 14, 2014

Reporting the War in Irish Newspapers: Correspondence from the Petersburg Front

A constant stream of information about the American Civil War made its way to Ireland between 1861 and 1865. This came in forms such as family letters home, but it was also a hot topic for Irish newspapers. Some, such as James Roche’s strongly pro-Union Galway-American (later printed in Dublin as the United Irishman and Galway American) focused on the conflict more than others. Another was the Irish People, the organ of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the sister organisation to the American Fenian Brotherhood. These Irish newspapers even circulated among Federal troops at the front, and some contributed letters to its pages. The letter below, written by First Sergeant Robert O’Driscoll, demonstrates not only how quickly news could cross the Atlantic, but also highlights the dual concerns of many Irish-American Fenians in the Union military. (1)

‘Freedom to Ireland’, an 1866 Irish patriotic lithographic by Currier & Ives, 1866 (Wikipedia)

The doings of the Fenian Brotherhood in the Army of the Potomac have been discussed on the site in the past (see Michael Kane’s guest post here). The Fenian Brotherhood and Irish Republican Brotherhood were revolutionary organisations that were committed to bringing about an Irish Republic. In the early war years, many Fenians had viewed the conflict between North and South as an ideal opportunity for their members to gain much-needed military experience, hoping it would enable them to return home and foment rebellion from a position of strength. In Ireland, IRB leader James Stephens depended on the contributions of American Fenians (headed by John O’Mahony in New York) to sustain the organisation at home. In 1863 Stephens decided to establish a newspaper, the Irish People, to help finance the IRB and to serve as its mouthpiece.(2)

The newspaper secured premises on 12 Parliament Street in Dublin, and produced its first issue on 28th November 1863. Although it did not take the staunchly pro-Union stance of the Galway-American (which Stephens disliked, particularly as he saw it as promoting emigration to America), news of the American Civil War was nonetheless a key theme for the publication. The paper was produced in 16 pages, with each page three columns in width; of these two full columns were consistently dedicated to the war raging in America. Subscribing to the newspaper became a way for Fenians in America to show their support for the cause, and by April 1865 some 600 subscriptions had been taken out in the United States. Eventually the Government in Ireland moved to suppress the newspaper, raiding its offices and shutting it down on 15th September 1865. (3)

The Irish People of 6th August 1864 carried the below letter, written by First Sergeant Robert J. O’Driscoll of Company D, 88th New York Infantry, Irish Brigade. O’Driscoll gives an account of the Brigade’s participation in the Overland Campaign and the initial assaults around Petersburg. Aside from his chronicle of the campaign, the Irishman also has interesting things to say about Fenian involvement in the Union army. It is worth noting that the letter appeared in the Dublin paper less than a month after it had left the Petersburg trenches. As for the writer himself, Robert J. O’Driscoll was 27-years-old when he enlisted as a private in Company D on 29th March 1864. His rise through the ranks would continue beyond First Sergeant; he was promoted to Second Lieutenant on 13th October 1864. He would never realise his dream of returning to Ireland to fight for its liberation- Robert was killed in action outside Petersburg- just over three months after he wrote this letter- on 17th October 1864. (4)

James Stephens, leader of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (National Archives)

TO THE EDITOR OF THE IRISH PEOPLE.

Camp before Petersburg, July 10, 1864,

8tth Regt. N.Y.V., Irish Brigade.

DEAR SIR- On yesterday I had the pleasure of receiving for the first time a copy of your honest journal, dated June 6. I cannot tell why this is so, being a half-yearly subscriber. I can assure you this is the first copy I have seen since the commencement of our present campaign, and only by chance did I get a peep at this. I need not tell you with what pleasure I read its contents, and glad did I feel at the Cork prisoners being so nobly sustained. We expect the paymaster round in a few days to visit us: should he do so, I will see what can be done in our brigade for my old neighbours.

Sir, thinking that, perhaps, something from the brigade may not be unwelcome to you or your readers, I give you a few words:- On the 3d of May, on which memorable morning the Irish Brigade, mustering about 2,000 effective men, struck tents and, under command of Colonel Smith,* of the 1st Delaware Regiment, crossed the Rapidan river, thereby commencing our march to Richmond. Ah, sir, this road to Richmond is a rough and dark one to journey upon; one now dyed with some of the best American and Irish blood. To describe the numerous engagements which our brigade participated in, from the 3rd of May until now, is more than my time and, probably, your valuable space would admit of. On the morning of the 5th we commenced the battle of the Wilderness, where the carnage so horrible that the recollection of it causes the strongest of us to shudder.

We were more or less engaged up the evening of the 11th, when we though we would be relieved, our ranks being rather thinned, and being dreadfully fatigued we were ordered to lie down in a meadow; we had scarcely done so when “fall in” was whispered in our ears by our commanding officers. Jumping up we were surprised to be in front of our enemies, our skirmishers steadily advancing. It being not yet day, we could not form an idea where we were advancing upon; however, we were not kept long in suspense, for whiz, whiz, came the grape and canister into our midst, when the order was given to “fix bayonets, charge.” As day broke, we found in our front a battery of forty-two pieces of rifled cannon, with Johnson’s division of 8,000 men, who were waiting for reinforcements to come up to attack us. When we advanced, some of our boys sung out, stop your firing, do you want to murder your own men? They stopped immediately, we closing upon them. I will leave you to judge of their surprise, as line after line of our corps, Hancock’s, fell pell-mell on their almost impregnable works. Those at the outward works fought desperately, but being out-numbered, they had to give way. Their rear guard advanced, and tried hard to drive us from the works, and until our fellows opened the captured cannon upon them we did not succeed in taking General Johnson with 8,000 prisoners. Often since have I heard them sing out across the Confederate lines. “Well, Yank, you had it soft at Spotsylvania, but look out next time.” We were then relieved of Colonel Smith, and handed over to Colonel R. Burns, of the 28th Mass., who commanded us through the battles of North Anna and Tullapatomy Creek, when on the 3rd June he fell mortally wounded, leading the brigade against a battery at Coal Harbour, where we suffered a gallant defeat. The Corcoran Legion suffered heavily too in this charge. Coal Harbour is ten miles E.N.E. from Richmond. Colonel P. Kelly had now taken command of us, having been detained up to this in New York on special duty. Being ordered again to march, we arrived at daybreak on the morning of the 16th of June in front of the now famous city of Petersburg, where we had temporary rest until the 3rd p.m. when we were ordered to advance in front, and throw up breastworks preparatory to a grand charge, which was to come off at six o’clock the same afternoon. Under a pretty smart fire from the enemy, our “boys” succeeded in finishing their works, wearied out by constant marching and fighting we laid down on our stony pillows, trying to snatch a moment’s slumber, but were doomed to disappointment. At a distance of nine hundred yards, and in an oblique direction lay the rebels in a line of strong intrenchments, supported by heavy artillery, together with a large force of concealed infantry, who, the moment we showed ourselves gave us an uncomfortably warm reception. To storm the enemy at the point of the bayonet was our duty. Our brave fellows were well aware of the task before them- to run nine hundred yards through thickly brambled ground, under a cross-fire from an obstinate foe, before we could grapple with him, was no pleasant sensation; yet jokes were passing round as merrily as if we were preparing for a visit to Ireland.

At six o’clock, p.m., Colonel P. Kelly gave the order, “Attention, Battalion! Fix bayonets! Forward! Charge!” Colonel D.F. Bourke first leaped the works, when the rebels opened a withering fire upon us, which nearly stunned us. How any one of us escaped is a miracle. It was here our veteran Captain D.F. Bourke proved the soldier. Cool and self-possessed, he called, “Halt! Close up!’ which our poor shattered regiment immediately did. “Forward! Charge!’ On, on we continued, every step costing us the lives of dozens of our bravest comrades, before we reached the enemy. General Hancock, seeing our condition, sent forward Birney’s “command” to support us. We succeeded in driving the enemy from his position- but at what a sacrifice of human lives! Our gallant Colonel P. Kelly fell in the early part of the fight, which was an irreparable loss to us, while our remaining officers were all more or less maimed, amongst whom were Captain D.F. Bourke, with our veterans, Captains O’Driscoll and O’Shea, and Lieutenant Sweeney. The gallant 69th, 63rd, 116th P.A., with the 28th Mass., suffered similarly with outs. For the nest three days we were partially engaged, when we were ordered to take up our position inside our outside entrenchments, there to enjoy, as best we may, that rest so long and so anxiously looked for. I fear our stay here will be but short. Since I commenced to write this our waggons are ordered to fall back ten miles to the rere, a sure signal that a storm is brewing.

On yesterday I strayed over to the Corcoran “Boys,” to enquire how my Fenian Brothers were getting along, I met our friend Captain Welply, in splendid fighting condition, and as zealous as ever in the old cause. [Welply was later killed in action at Ream’s Station]

He, with Captain O’Rourke, are heart and soul for our deal old land, and they are well aided by the entire legion. It is remarked by all that when a daring act is performed by any one, the boy is sure to be a Fenian. I remember once, and often heard it repeated in America, that here was a splendid school for Irishmen to become soldiers. True, but can poor Ireland afford to pay so dearly for her military knowledge, when at such training we lose men like Corcoran, Brennan, William O’Shea, young Mitchel, with thousands of splendid true men. Then, in God’s name, it is time poor Ireland should cease patronising such schools. Oh, yes, Irishmen, no matter how ardent you may be for military fame, I implore you to suppress “for a time” your noble feelings, and, in the words of Mr. O’Mahony, “remain doing garrison duty in Ireland until we get the order to push forward to relieve you. That such an order may be soon and sudden, is the fervent prayer of all my countrymen in the American army, and you, sir, I presume, are aware of that fact.- Yours sincerely,

ROBERT J. O’DRISCOLL,

1st Sergeant, Co. D., 88th Regt., N.Y.V.,

Irish Brigade. (5)

Parliament Street in Dublin, looking towards City Hall. This is where First Sergeant O’Driscoll’s letter from Petersburg arrived to the newspaper offices in 1864 (Wikipedia)

*Thomas Alfred Smyth from Ballyhooly, Co. Cork. A Fenian himself, he would become the last Union General to be mortally wounded in combat, dying in April 1865.

(1) Ramon 2007: 141-2; (2) Ibid; (3) Ibid: 146-7, 159; (4) New York Adjutant-General, Irish People 6th August 1864, Ramon 2007: 178; (5) Irish People 6th August 1864.

References

New York Adjutant-General 1893. Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York, Volume 31

The Irish People Saturday 6th August 1864. To The Editor Of The Irish People.

Ramon, Marta 2007. A Provisional Dictator: James Stephens and the Fenian Movement.

Filed under: 88th New York, Battle of Petersburg, Fenians, Irish Brigade Tagged: Fenian Movement, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Petersburg, Irish Nationalism in America, Irish People Newspaper, Irish Republican Brotherhood, James Stephens, John O'Mahony

December 13, 2014

‘In Account Of We Being Irish': A New Irish Brigade Letter After Fredericksburg

As some readers will be aware I am currently working on a long-term project identifying and transcribing the letters of Irish and Irish-American soldiers contained within the Civil War Widows & Dependents Pension Files. This work has already identified large numbers of previously unpublished letters of Irish soldiers, which I intend to prepare for ultimate publication. One of the most interesting I have come across so far are those written by a soldier of the Irish Brigade after Fredericksburg. Given that today is the 152nd anniversary of that engagement, I thought I would share it here for the first time. It was written by Tipperary native William Dwyer of the 63rd New York, more than a month after the battle. He had written other letters (now lost) to his mother that December, but it is clear from his January 1863 correspondence that the action was still having a deep emotional impact on him. William was also clearly angry that the Brigade were not being sent home to refit, something which he attributed to anti-Irish prejudice. Although he survived Fredericksburg, William ultimately succumbed to disease at City Point, Virginia on 12th July 1864.

The Stone Wall at the base of Marye’s Heights, Fredericksburg, the target of the Irish Brigade Assault (Library of Congress)

Camp near Falmouth Va

January 23d 1863

Dear Mother,

I take the opportunity of writing these few lines to you hoping to find you and my sisters in good health as this leaves me in at present thank God for it. Dear Mother I am sending you forty dollars $40 now we got paid on yesterday and all we got was four months pay $52 dollars and I am sending you 40 and we expect to get pa[i]d the other two next month. The[y] owed us seven months and gave us only four. I owed the sutler three dollars for tobbacco and I gave the priest one dollar so Dear Mother I will send you twenty more when we get paid again. We have log houses built for the winter for our selves but we dont know how long we will be left in them we expect to leaves them every day. Dear Mother tell Julia Greene that I have not see Mike since the Battle of Fredericksburgh only once and let me know if he is moved away because his Regt expected to got to Washington he was camped 8 miles from me when I seen him last. Dear Mother I wrote an answer to you on the 31st of December last and I got no answer from you yet and I had no way of writing sooner untill I got paid and you might write to me any how even since if you did not get or not. Dear Mother it is very cold out here and on Christmas day it snowed terrible and I was on picket on the banks of the Rappahannock River all day and night with only half a dozen hard crackers and a piece of raw pork for the Day and night.

Dear Mother we are expecting an other fight in Fredericksburgh some of these days but I dont want to see any more for to see all the men that fell there on the 13th of decr last it was heart rending sight to see them falling all around me.

Tell Mrs Smith that Johnny Mc Gowan is well and in go[o]d health and Tommy Trainors mother also he is well and in good health. Dear Mother we thought surely that our brigade was going home to New York that time but we were kept back and would not be let go in account of we being Irish. In the three old Regts we have only 250 for duty when we ought to have 3000 men for duty so we thought when we were so small that we would be sent home to fill up but who ever lives after the next battle can go home because it is little will be left of us.

No more at present,

From you aff son

William Dwyer

63d Regt N.Y. Vol

Co H Irish Brigade

Washington D.C.

Or elsewhere

Answer this as soon as you can I never got the box that you said uncle Charley sent me if he sent whiskey in it it was all broke box and all kept.

Give my best respect to uncle Charley uncle James aunt Mary and children the two Mrs Kells Mary McAlamey Mrs Delany Mrs Gallaher and their families

James Lodge and family

Also to Pat Fogarty

Jer Fitzpatrick

The Camp of the 110th Pennsylvania, Falmouth, Winter 1862. William Dwyer wrote home from a similar camp in Falmouth (Library of Congress)

The fact that William felt the brigade was being kept at the front because they were Irish is an interesting one. It feeds into a belief, current after the carnage of 1862, that the Irish were being used as cannon fodder by prejudiced ‘Know Nothing’ officers. There is no evidence to substantiate this claim, but it is interesting to consider just how widespread this view may have been among Irish Brigade soldiers in early 1863. The extreme mental trauma they had experienced by participating in the 13th December charge must have exacerbated many of their reactions to later news that they would not be going home. William wrote a second letter three days after the first, in which he outlines how his mother, thinking the brigade had returned to New York, had ‘run down to the Battery’ (the Battery was on Manhattan) to meet him. It also demonstrated that he was a man of faith, which must have done something to sustain him during his experiences:

Camp Near Falmouth Va

January 26th 1863

My Dear Mother,

I received your welcomed letter this day which gave my great pleasure to hear that you and my sisters are in good health as this leaves me in at present thank god for it. Dear Mother tell Mrs Fay that Tom her husband was here with me and Johnny Mc Gown for about half an hour and he was telling that their pontoon bridges was stuck in the mud and they were two days trying to get them out he is in good health and he was telling me that Mike Greene was well and in good health. Tell Maggie that General McClellan has left us and General Burnside has taken his place and tell her that the[y] will put us in to fight if there was only ten of us left in the Brigade all we have now is 250 men out of 3000 in the three old Regts. Dear Mother I did laugh when I heard that you run down to the Battery to look for me we were so sure that we would be going home that time we thought it was all right. We are hear Falmouth Virginia we have plenty of clothes and we have built log houses for ourselves so we expect to winter here for awhile but dont know ho[w] long after that. If I had any way of getting or ink I would write to you although I did[n’t] get any answer to the other tell Mrs Smith that Johnny McGown sent 30 dollars last week by Adams Express.

Dear Mother Father Dillon left us last augst at Harrisons Landing and he is with Corcorans Legion and I am glad that my mother is getting the Relief yet and I dont get any of the papers you sent me send me an other one and if I dont get that one I will tell you to stop sending any more. I dont want anything as yet the next letter you send send me a scapular and fix it so as it dont be any weight in the letter you will get them to buy in any Catholic Book Store and you can get it blessed by the priest. The one I got from Father Dillon it is all wore and I lost the part that goes down my back he gave every one of us one when he was leaving us if you can get one from the sisters get it. Dear Mother you can keep the five dollars I am glad that you dont want for any thing I sent you forty dollars last week by adams express and as soon as you get it let me know. Is Julia living in the country yet. No more at present,

Your aff son

William Dwyer

63d Regt N.Y. Vol.

Co H Irish Brigade

Washington D.C.

or else where

Give my best Respects to

Maggie Kells Pat Fogarty

Mary Hays Jerry Fitzpatrick

Lizzy Curran James Curran

Margt Curran

Mary Curran

Also to Mick Curran two Mrs Kells

Mary McAlanney

and their families

*The letters above have no punctuation in their original form. Punctuation has been added in this post for ease of modern reading- if you would like to see the original transcription please contact me. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References

William Dwyer Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC103233

Filed under: 63rd New York, Battle of Fredericksburg, Irish Brigade, New York, Tipperary Tagged: Anti-Irish Prejudice, Battle of Fredericksburg, Battlefield Trauma, Impacts of Battle, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Fredericksburg, Know-Nothings, Tipperary Veterans

December 11, 2014

The Civil War Letters of Captain James Fleming, Part 3: With Hawkins’ Zouaves at Hatteras Inlet

In the third instalment of letters from James Fleming of Antrim (Find Part 1 here and Part 2 here), we join the young Irish officer of the 9th New York “Hawkins’ Zouaves” at Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina. These three letters span November 1861 to January 1862. In the first of them James talks of his many countrymen in the 9th- ‘Americans at heart’- and tells his mother how the landscape reminds him of the coast of Larne. The second deals with his prospects of dying in the conflict, although James assures his mother that ‘the ball is not made yet to take my life’. The last of the series recounts the warmth of the weather even in winter, as James clearly grows weary of life at Hatteras and longs to move on.

A Hatteras Landscape (Charles Johnson, The Long Roll)

Camp Wool Hatteras Inlet

North Carolina

Novb 18th 1861

Lieut Jas H Flemming

9th Regt of N Y Zouaves

Fort Monroe

Virginia

My Dear Father Mother

I received your last letter of Sept which gave me great pleasure to receive also to hear that you are all well as thank God this leaves me at present in good health as I have stood this climate very well as its very trying on the health as the most of our officers are sick and a great many of our men but we have got orders to keep ourselves in readiness to start by the next beat but where our destination will be is yet a secret but will be able to let you know before I send this letter. I believe that we will rejoin our Brigade again at New Port News under General Phelps as our boys calls him Dady our Regiment is comprised of young men from 17 years to 25 I may say not one older all fine young fellows. When we left New Port News the General P. Said that he would let them have the 7th & 2nd & through them in the 1st if they would only let him keep his boys that is what he calls us but they thought there was work to do and so the 9th had to go, you mention that you do not see our regiment mentioned in any of the papers. I will send you a paper by the next boat if it mentions us as we are called the Crack Regiment of the Volunteers which I believe we are but I am only afraid that we will not have a chance of showing the world what the 9th can do. Recollect Dr Mother that they are not all Americans by birth, as I have a great many of my own countrymen only Americans at heart which we find in this struggle to be the real men. There was a great naval expedition past here for a few days ago composed of about 80 gun boats and 18,000 men they have taken one very strong place, Beaufort, and are at present bombarding Charleston if you recollect that is where the fighting commenced Fort Sumter Charleston Harbour. We are waiting patiently to hear of them being successful if they can so the half of the fighting will be over as we have only them to whip them on the Potomic which will end the fights. Dear Mother you mention in your last about them opening letters etc, such is not the case I have got all your papers letters etc which I think you sent. They open Boxes sent to the men to prevent them from getting liquor and they are opened by a man appointed out of the Regt for that purpose, but I think that they are wise particular in forwarding letters & papers more than they were before the war so you need not be afraid to send me anything in the way of papers as it gives me great pleasure to receive anything in the shape of papers from home. I sent you a paper by the last boat which I hope you got tho do not allow any letters or communications of any kind to go south nor none from the south here, but I hope that the communication will be open soon again. I said I would let you know where we are going by this letter but we have not changed our camp yet but will during next week.

Dear Mother I have nothing of any consequence to write this mail but I hope I will have something of more importance to write in my next. I got Anny’s letter and would have replyed by this mail but have not much time tell her I will write her a long letter soon and am glad to hear the family are so well. I hope she makes a kind Mammy to the young Rankins give her my warmest respects and a kiss to each of the children also to her sister and mother not forgetting old Mrs Rankin & sister also any of the old friends in Larne. I am very glad to hear that Alex & Nancy are getting along so well give them my best respects. as I sit here writing when I lift my head & look out the Pamlico Sound meets my view reminding me of the old coast at Larne but then there’s another object which meets my gaze which I would not see at Larne, that is our camp & muskets stacked along our Company that looks rather warlike, and then the sound of distant guns lets you know of something going on only wishing to join in the strife at the taking of Beaufort the other day we heard the reposts of the cannon all day long & that is about 50 miles from where we are camped. They say its a great sight to see them bombarding one of these places. The Rebels are getting a little frightened at the yankies as they call us as if our correspondents lets us know how they are getting along we will have a grand [illegible] shortly which I hope it will be about Christmas as I am always fond of shooting about that time and think New Years Day [illegible] place here for visiting and so we expect to spend our New Years Day in either Charleston Baltimore or some camp southern city.

Dear Mother I must now conclude hoping to hear from you soon again, and if its God will that anything should occur to me you will get word of it right away but I hope with the grace of God to come through this with flying colours but intend doing my duty to the last. Give my kind love to my Brothers I will write Harry in a few days. I got a letter from Malcolm & write by the next mail & was glad to hear that they were well. Kind love to Father & yourself & may God Bless you all & the sincere prayer of your son

James

Camp Wool, where James Fleming was writing from (Charles Johnson, The Long Roll)

Hatteras Inlet

North Carolina

Jany 7th 1862

My Dear Father & Mother

I received your letter the morning of 11th Decb which gives me great comfort to know that you are all well as thank god this leaves me at present enjoying good health our regiment is still encamped at this place and likely to be for some time as yet and so you make your mind quite easy concerning me while I remain on this island as there will never be any fighting here there is nothing of any consequence going on at present our army is advancing as I mentioned in my last which I wrote about 2 weeks ago. We may have to leave this place on a forward movement which we are longing for as the army at present is getting quite impatient and only longing to drive the enemy out of the field which we can do I think with very little loss on our side. I will write a few lines to Jas Kelly as soon as I have time as I am glad that he is to be found assisting to defend his adopted Country. I have wrote Anny by the same post and stated that I was writing to you. I have first got a letter from Mary Ann by the same mail which fetched yours. She states that they are all well she said that she had wrote to you some time shortly which I hope you have received at this time. I have received two boxes of underclothes etc from her. I always write to her for anything of that sort Dr mother you want to know what I have done with my clothes & books. My clothes I sold the most of and my books I gave away I fetched one suit of clothes out with me and you would have had a laugh at me trying to get them on me they would not look at fiting me so I had to throw them aside. I believe that Mary Ann got some of my things which she keeps to my return. Dr mother give my kind love to my Brothers when you see them tell them to always write me & I will answer when I have time. I am glad that my Father is so stout and always able to run about as I hope that the time is not far distant when I will have the pleasure of seeing you all and also Mary Ann may accompany me home but in the present disturbed state of the Country the safest plan is to help to see her righted again which I hope will be before a great time. Dr mother if its Gods will that I should fall I will do so doing my duty which I hope will be a consolation for you to think that it was not the assasins stall or the murderers ball which will reach me at a time perhaps when I am not thinking of the like as I can say that upon the field I dread not death as I think if I had any choice give me the field fighting for my Country as I think I will never be shot in the back at any rate, as this is only mere supposition on my part as I think that the ball is not made yet to take my life or yet to scar any body. For now I must conclude kind love to my uncle as I hear that he is still with you write soon from your affectionate son

Jas H Flemming

A Hawkins’ Zouave at Camp Wool, Hatteras (Charles Johnson, The Long Roll)

Hatteras Inlet

Camp Wool

Jany 29th 1862

My Dear Father Mother

I send you a few lines of this boat as I may not have a chance of writing for 2 or 3 weeks again hoping this will find you all enjoying that great Blessing good health as thank God this leaves me at present as healthy and well as ever I was. I wrote you by the last mail which I hope you have got before this time. You can see by my address that I am still on Hatteras but I sincerely hope that we will have the pleasure of leaving here before long. Always address my letters the same as usual. You can see its now about the worst of the winter season with you and here I am about in my pants & shirt and always quite warm the only things that we have to dread here is the heavy dew that fall during the nights but thank goodness they have never had any effect on me for so far.

Dr mother give my kind love to my Brothers as I am expecting some letters from them soon. I hope that they are all enjoying good health and succeeding in all their undertakings tell Harry to write soon & let me know how Andy & he has succeeded during last summer or if they made any thing by the ferries and how Malcolm is getting along I am expecting a letter every mail from him but I suppose that he is like Alex has not time to write. I had a letter from Mary Ann they are all well. I must soon finish with kind love to all. How’s Thos & Nancy getting along. I am sorry that he is not succeeding better than what he has done but I hope that he will improve yet. How is my uncle getting along I suppose that he is still stoping with you. I wrote a long letter to Anny by the last mail at the same time I wrote yours I hope that she got it alright.

Dear Mother I wrote you this note some 10 days ago but our mail was stopped and as it goes out this morning I embrace the opportunity of sending this as I hope sincerely that another letter from home will not find one on Hatteras as I am tired of it. I must soon finish with kind love to my friends and may God bless you and father.

In the prayer of your

Son James (1)

A Hawkins’ Zouave at Sundown, Hatteras (Charles Johnson, The Long Roll)

(1) Louise Brown Transcription

*The next letters will join James in March 1862, when he has finally moved on from Hatteras to Roanoke Island. Note that some punctuation has been added to the letters above for ease of reading. Sincere thanks are due to Louise Brown for sharing these letters of her ancestor, which she has also transcribed, with readers of Irish in the American Civil War.

*I am grateful to Michael Zatarga, a researcher of the 9th New York, for drawing my attention to Swedish-born Charles Johnson’s The Long Roll, from which the image of Camp Wool is drawn. The account makes frequent mention of Fleming, who Johnson was fond of.

Further Reading

Johnson, Charles 1911. The Long Roll. Being a Journal of the Civil War, as set down during the years 1861-1863 by Charles F. Johnson, sometime of Hawkins Zouaves.

Filed under: Antrim, New York Tagged: 16th New York Cavalry, 9th New York Infantry, Antrim Veterans, Hatteras Inlet, Hawkins' Zouaves, Irish American Civil War, North Carolina American Civil War, Northern Ireland Veterans

December 6, 2014

‘Debilitated By Having Borne 13 Children': An Irish Emigrant Recounts Her Family Story, 1871

In May 1871 an elderly Monaghan woman, ‘infirm and broken in body’, came into Chicago from her ‘Irish Shanty’ on the open prairie outside the city. Possessing little other than ‘her scanty wardrobe’, she had come to meet her attorney. It was not her first visit. Earlier that year, she had dictated the story of her family and their hardships in extraordinary detail, part of a process she hoped would help her secure a pension based on her son’s Civil War service. By May that pension had still not materialised. She now sat in tears in the attorney’s office, as her husband lay on his deathbed in the family shanty. Jane had not made the trip lightly.

Illinois Prairie Grass, from which the Murphy Family made their livelihood (Robert Lawton)

Jane’s attorney was moved to immediately write a letter on her behalf as a result of this second visit:

Chicago, May 18, 1871

Dr. Trevitt,

Dear Sir,

For special reasons, I ask that Jane Murphy’s claim, No. 194,826, as dependent mother of Michael Murphy, deceased Private, Co. G, 90th Illinois Vol. may be taken up out of it’s regular order and disposed of.

She is in my office today; debilitated by having borne 13 children, by prolapsus uteri, and by a 6 inch tumor on back of her neck; and in tears, having walked four miles, from her shanty home on the open prairie, to see about her pension.

She reports that her husband has been, for about two months, unable to leave his shanty, by reason of ill health from induration of the liver and chronic inflamation of the stomach, and is in a dying condition.

Their invalid son James is confined at home with white swelling of the knee, and helpless.

The additional evidence that I have today forward to the Pension Office by the mail that takes this letter, makes a strong, meritorious, urgent claim, and discloses a special emergency and need of her pension.

Very Respectfully,

On behalf of Mrs Jane Murphy

J.W. Boyden, Her Atty.

Jane Murphy’s family made their living from the prairie grass that surrounded their shanty, a few miles west of Chicago. With her husband suffering from long-term illness, the family looked to their son Michael to help with their support. He did this by cutting prairie grass and bringing it to market in Chicago where he sold it as hay, and by growing vegetables. When war came, Michael enlisted in the 90th Illinois Infantry, ‘Chicago’s Irish Legion.’ Upon joining up the Monaghan man gave $25 of his bounty money to his mother, and during the rest of his service sent another $90 home. That all ended on 25th November 1863, when Michael was killed in action at the Battle of Missionary Ridge, Tennessee. As part of her application, Jane included the only letter she had remaining that Michael had written to her:

Head Quarters 90th Reg. Ill. Inf.

Camp Sherman Sept. 15th 1863

Dear Mother,

I received your letter on the 7th inst and I am sorry to hear that you are not well. I am also sorry that I cannot send you any money as there is no signs of us been paid for some time- Dear Mother I am surprised at you not mentioning my Father or Brother James in your letters and I wish you to let me know in your answer to this how they are- I am glad to hear of your receiving the money I sent you last March- I was very sorry to hear of John & Charles Hudsons death, also of Mrs Floods death. Let me know what Regiment Jas O Donnell is in and what place and if Mr Kenney gets any word from John- Enclosed find my likeness and I would like to have yours and Annes likeness by Leut Duffy or Sargt Mc Namara that is going to Chicago- Let my Father know that I will send him money by next Christmas anyhow. Patrick Smith [who was also a native of Monaghan] sends his best Respects to you all and he enjoys as well as me good health

I remain your

loving son

Michael Murphy

Jane also included a number of Physician’s reports in her application, which elaborated on the situation that she and her husband Patrick found themselves in. She had difficulty proving that Patrick was unable to work, as he could not be examined by a Pension Agency Surgeon. On 18th May 1871 it was outlined how he ‘has not been out of his shanty, two months past, is in a dying condition, and cannot be brought safely 4 miles to be examined by a Pension Surgeon in Chicago, and has no money to pay the Board or any member of it to go out examine him.’ The original Physician’s affidavit had been prepared on 13th March 1871. He recorded that Jane was ‘about 57 years old; has a fibrous tumor on the back of her neck, about six inches in diameter; also, prolapsus uteri, or falling of the womb; is and has long been a confirmed invalid and disabled from supporting herself by manual labor, for at least 10 years last past.’ He further noted that Patrick was ‘about 65 years old, and is and long has been disabled from supporting himself by manual labor, by reason of induration of the liver, chronic inflamation of the stomach and general debility, and is and long has been incapable of supporting his wife.’ He added that the couple had ‘long lived out on the open prairie, on a small patch of ground, west of the settled portion of the City; and by a recent act of the Legislature, the land in their vicinity has been nominally included within the City Limits. Their means of support have been the raising of vegetables, keeping a cow, and cutting wild prairie grass or hay, and selling this wild hay, that costs only the cutting and hauling into the city, which brings a few dollars per ton in open city market.’

In further support of their application, one Physician described the couple as ‘poor, worthy old people’, and their son Michael as a ‘large, stout, industrious young man, the prop of their declining years.’ The pension was eventually approved, payable to 975 West Madison Street, Chicago. Patrick Murphy did not live to benefit from it. It transpired that he was suffering from stomach cancer- the Irishman passed away on 12th July 1871.

The pension application process that the Murphys went through has left us with significant documentation about their lives. However, one of the submissions stands out to provide a window in the life of nineteenth century Irish emigrants; that is the statement of Jane Murphy herself. Unusually for such affidavits, it is written in the first person, as Jane charted her life from her 1830 marriage in Monaghan through to the death of her son in Tennessee. Along the way she outlined the circumstances and fate of each of her 13 children. Jane Murphy endured great hardship during her life. Her voice resonates to us across more than 140 years:

…I was married, December 25, 1830, in Ireland, to my husband Patrick Murphy, I have never owned any property, except my wearing apparel, and have had no other means of support than my own labor when in health; my husband’s labor when he was able to work, and the labor of our two sons, James and Michael Murphy.

I have given birth to thirteen children: John, the oldest, in 1851, left me in Ireland and emigrated to America, probably to some Southern state, and I have never, since 1851, seen, or heard from him. James, the second, emigrated with me in 1853, has always lived with me, unmarried, has done nothing, by reason of pulmonary consumption, during ten years past, more than enough to pay for his board at home and clothes.

Mary came, in 1851, with John to America; worked as house servant till her marriage, about 1858, to Thomas Hudson; has had 7 children and neither she, nor her husband have contributed to my support, nor can they, having all they can do to support their family. Ann, my 4th, is unmarried, consumptive, works out as house servant; does and con do nothing towards my support; nor can Catherine, my 5th, nor her husband, John Whalen, who live in Texas, at Houston, nor are they able to contribute to my support. Michael, my 7th, was the soldier, born in October, 1842, and was killed, when 21 years and 1 month old. Peter, my 8th, was born and died in Ireland in 1846. Patrick, my 9th, died in 1864, at 16 years of age. Another Peter, born in 1850, died Feby 14, 1868, and was my 10th, Jane, my 11th, born in 1853, has lived in Texas with Catherine since she was 14 years old [where the sisters worked as dressmakers]. Francis, my 12th, born in 1858, and Robert, my 13th and last, both live at home, but are both too young to contribute towards my support. My husband and James and Michael helped support me by keeping a cow and raising a few vegetables, but chiefly by cutting and hauling prairie grass, or hay to Chicago hay market, when they were well.

Michael Murphy was always large and stout for his years. He left off going to school, in 1855, when almost 13 years old. During the seven years thereafter, till his enlistment in October 1862, Michael lived at home, worked in the garden, tool care of the cow, but earned his money by sales of prairie hay in Chicago market, hauled, and cut or mowed by himself, assisted by his father and brother James; at from 50 to 60 loads annually, for $2 to $4 per load, All his earnings were applied to the support of the family, including myself; as well as $25 Bounty he gave to me at enlistment and $90 sent home to me of his pay; and $200 Bounty received after his death by his father; who has no property except a prairie lot, shanty, cow house, old furniture & clothing, all worth not over five hundred dollars.

*This file was brought to my attention by friend Jackie Budell, who first brought it to my attention and made this post possible.

References & Further Reading

Michael Murphy Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC153520

Illinois Civil War Muster and Descriptive Rolls Database

Swan, James B. 2009. Chicago’s Irish Legion: The 90th Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War

Robert Lawton Image of Prairie Grass

Filed under: Battle of Missionary Ridge, Illinois, Monaghan Tagged: 90th Illinois Infantry, Battle of Misionary Ridge, Chicago Irish, Chicago Irish Shanty, Chicago Prairie Grass, Chicago's Irish Legion, Illinois Irish, Irish American Civil War