Damian Shiels's Blog, page 37

June 22, 2015

‘Induced to Enlist': The Last Letter Home of an Irish Draft Substitute in 1864

There is sometimes a perception that large numbers of Union troops– particularly in the latter months of the war– had been drafted into the Federal military. This was not the case. Of the c. 776,829 men whose names were drawn during the four Civil War drafts, only about 46,347 men (a little under 6%) ever seem to have actually worn Union blue. Of those who did not, more than 315,000 of those whose names came up were exempted, while over 160,000 simply failed to report in the first place. Tens of thousands chose to pay to commute their service, while in excess of 73,000 men furnished a substitute to take their place. Many Irishmen elected to serve as substitutes in the war’s later years, and in the majority of cases they were supplied by often unscrupulous middlemen– substitute brokers.* One such substitute was John McKeown. Some details as to how John became a substitute survive, as does the letter he wrote home to his wife from the front, just hours before the commencement of the 1864 Overland Campaign. (1)

Irish couple John McKeown and Margaret Christy were married in Philadelphia on 28th December 1863. John, who worked as a sawyer, was 21-years-old on his wedding day, nine years the junior of his 30-year-old wife. Their life together would be a short one. In February of 1864, Margaret remembered that her husband was induced to go to Pottsville. She didn’t see him for the next three days, but when they were eventually reunited Margaret remembered that John was ‘…in the Barracks at the corner of 23rd and Wood St. Philadelphia. He there told me that he had gone to Pottsville Pa. in company with a man named Billy Parker, who had paid him a small sum of money and induced him to enlist, while he was intoxicated with liquor. He further told me that his name had been placed on the Company rolls as John Carroll, and that it has been so entered by advice of the said Billy Parker.’ John gave his wife no explanation as to why he enlisted under an alias, but another friend would later claim that it was because McKeown was acting as a substitute for a drafted man whose name was Carroll. (2)

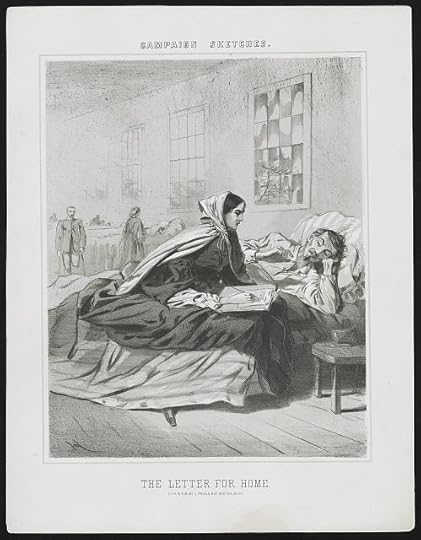

John wrote to his wife from the camp of the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry on 3rd May 1864. The movement of the Army of the Potomac that would commence the bloody Overland Campaign would begin the following day. That this advance was imminent is apparent from John’s letter, which relates that the shantys in which the men had been living had been knocked down. The young Irishman was evidently not an eager soldier, and speaks of his longing to get home to his new bride. Interestingly he claims that many others feel the same, and that desertion was commonplace. John describes some of the relatively rudimentary training he received before the anticipated ‘very big battle‘ of the summer. Clearly too there had been some falling out between John and his family, particularly his father– perhaps over either his marriage or his enlistment as a substitute. However, what is most apparent is John’s very deep affection for his wife. (3)

Bounty Brokers Looking for Substitutes (Library of Congress)

Phila May the 3d 1864Dear wife I am going to send you these few lines to let you [k]no[w] I am in good health and I hope for to find you in the same. Dear Marget I have sent you a letter before this and I got a letter from you the next day which I was very glad to see. Marget we have nocked our shantys down and we dont [k]no[w] when we are to leave here. I do think very long for to get home for I have enough of this place the most of the men would like to get home the[y] are sorry for re enlisted again the[y] wish the[y] were home if the[y] wore the[y] say the[y] would not be lying in a hard bed. A good many of the men has deserted some of them has been catched and has got there hair shaved as white as snow and drumed around the camps and the benits [?] after there and then sent away.

The[y] say that we are going to have a very big battle this summer bigger than ever the[y] seen yet the[y] say it will put an end to the war. The[y] have tried us with our guns out in the field we were shooting at barrels we had 3 shots a piece I nocked the barrell down twice 3 hundred yards distance our Company is allowed the best in the Reegiment. I cannot tell exactly the time I will get home now unto after this battle but I hope you will get along to I do see you and I will do the best I can for you. Let me [k]no[w] if you got that letter from your folks yet we do not here any word about the letters stoping down here I hope it so the[y] dosent stop the mail for if the[y] would the men would all go away home as soon as the[y] would here it was stoped. Dear Marget do not fret yourself for I hope in God nothing will happen on me unto we meet together I [k]no[w] it is a very long time to wait to get seeing other but you will have to do the best you can. I do wiry [worry] myself very bad here for it is such a wile [wild] place not a house near you.

I do not care about there [their] box if my father had a sent one to me I believe I would a got it. Dear wife do not mind sending any box for a while yet I have been mustered in for another pay I do expect to get paid the middle of this month I have heard them say so. I will send you what I can for I have the best rite to send it to you are good to me since I left you and you shall get all my money. I have got the plug of tobacco in your last letter. I would like very much I was at home I would like to see Mis Nancy and Susan and Marget and I am glad that you and her is good friends. I send my best respects to her and Susan and Marget and if God spares me my health I will see them all and I am glad to here that Miss’s Nancy is well and all the girls I do not forget them. It is all lies that I sent money to my father if I did I would tell you about do not believe what you here. Let me [k]no[w] how little Johnn is doing I would like to see Johnn but poor felow I am far away from him. I send my love to you and him in the warmest manner.

So no more at present but remains your affectionate Husband John McKeown. Direct to 71 PA Co G 2d Corps 2d division Washington D.C. or elsewhere. (4)

Within a couple of days of this letter John was feeling the full brunt of battle, as Grant and Lee clashed for the first time in the Battle of the Wilderness. He would barely have time to catch his breadth before the next engagement, at Spotsylvania Court House. John’s ultimate fate is unclear; the regimental roster records his death in action at Spotsylvania on 11th May, while according to his wife he was wounded around the 15th and died in Fredericksburg as a result on the 19th. Regardless, it seems likely that this letter was John’s last to his wife. Margaret applied for a widow’s pension from her home at 623 South 15th Street in Philadelphia, but would struggle to prove her husband’s service due to his adoption of an alias; it would be some years before her efforts proved successful. (5)

‘Wanted A Substitute’ A Wartime Sheet Music Cover (Library of Congress)

(1) Murdock 1971: 356, McKeown Pension File; (2) McKeown Pension File; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.; (5) Bates 1869: 818, McKeown Pension File;*Beyond those drafted, many (including large numbers of Irishmen) chose to avail of substantial bounties in different localities to volunteer, as districts attempted to furnish enough men to avoid the draft. Many journeyed to those areas paying the most bounty money in order to obtain a hoped for windfall. This was another area in which brokers were extremely prominent.

**Punctuation and paragraph formatting has been added to the original letter for ease of reading. None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

John McKeown Widow’s Pension File WC105113.

Bates, Samuel P. 1869. History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865. Volume 2.

Murdock, Eugence C. 1971. One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North.

Fredericksburg & Spotslyvania National Military Park

Civil War Trust Battle of Spotsylvania Court House Page

Filed under: Battle of Spotsylvania, Pennsylvania Tagged: 71st Pennsylvania, Battle of Spotsylvania, California Brigade, Civil War Draft, Civil War Widow's Pension Files, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Pennsylvania, Substitute Brokers

June 14, 2015

Irish Hunger and Migration: Myth, Memory and Memorialization

This time last year I had the opportunity to speak at the Ulster-American Heritage Symposium in Athens, Georgia. It was the second element of what was a two-part conference held in 2014 (the first part having taken place in Quinnipiac University, Connecticut) to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the biennial symposium, which explores Ulster’s connections with the United States. Quinnipiac University is home to Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute, and they took the decision to publish proceedings from the two events. The resultant book was launched at Quinnipiac last week, and I am delighted to have had an opportunity to contribute a paper to it. My effort focuses on what the American Civil War pension files might tell us about the Ulster experience of emigration in the 19th century. This is the first of a couple of upcoming academic papers on my pension file research that should be published this year, hopefully presaging my book on Irish stories from the files, the manuscript for which is currently nearing completion.

Irish Hunger and Migration: Myth, Memory and Memorialization is edited by Dr. Patrick Fitzgerald (Mellon Centre for Migration Studies), Professor Christine Kinealy (Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute, Quinnipiac University) and Dr. Gerard Moran (European School, Lacken, Brussels). The volume covers a range of topics, including a number of relevance to those interested in the Irish experience of the American Civil War. The full Table of Contents is below, and if you are interested in picking up a copy you can do so by contacting the Great Hunger Institute– more details are available here.

Irish Hunger and Migration: Myth, Memory and Memorialization

Leaving for St. Christopher: Early Irish Migration to the New World 1630-60

Nini Rodgers (Honorary Senior Research Fellow, School of History and Anthropology, Queen’s Univeristy, Belfast, Northern Ireland)

Irish Hunger, Migration and Denomination, 1550-1850

Patrick Fitzgerald (Lecturer and Development Officer, Mellon Centre for Migration Studies, Ulster-American Folk Park, Omagh, Northern Ireland)

Famine and Place Names in Ireland

Kay Muhr (Senior Researcher of the Northern Ireland Place-Name Project, 1987-2010)

“This Great Agony of the Empire”: The Great Famine in Ulster

Christine Kinealy (Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute, Quinnipiac University, Connecticut)

A Tale of Two Famines: Famine Memory in Nova Scotia, Canada

Mark G. McGowan (Professor of History, University of Toronto)

The Wreck of the Brig St. john and Its Commemoration, 1849-2014

Catherine B. Shannon (Professor Emerita of History, Westfield State University, Massachusetts)

Memories of the Great Famine in Irish North-American Fiction, 1855-70

Marguerite Corporaal (Associate Professor of English Literature, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands)

French-Canadian and Irish Memories of Montreal’s Famine Migration in 1847

Jason King (Irish Research Council Postdoctoral Researcher, Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway)

The Society of Friends and Famine Relief in Ireland and Finland, c. 1845-57

Andrew G. Newby (Senior Visiting Research Fellow, Modern European History Research Centre, University of Oxford, England)

From Great Famine to Forgotten Famine: The Crisis of 1879-81

Gerard Moran (Coordinator of History, European School, Lacken, Brussels, Belgium)

“Remember that your Blood is Pure Scotch-Irish”: Ulster Americans and the Confederate States of America

David T. Gleeson (Professor of American History, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, England)

The Long Arm of War: Exploring the 19th-Century Ulster Emigrant Experience through American Civil War Pension Files

Damian Shiels

The Irish Hunger Memorial at Battery Park City: Mayo as Metaphor

Maureen Murphy (Professor of Teacher Education, Hofstra University, New York)

“Dealing with the Past” in Northern Ireland: Famine, Diaspora and the Influence of A.T.Q. Stewart

Brian Lambkin (Founding Director, Mellon Centre for Migration Studies, Ulster-American Folk Park, Omagh, Northern Ireland)

Filed under: Connecticut, Publication Tagged: American Civil War Pension Files, Ireland's Great Hunger Institute, Irish American Civil War, Irish Famine Studies, Mellon Centre for Migration Studies, Quinnipiac University, Ulster American Civil War, Ulster-American Symposium

June 2, 2015

Day of American Civil War Talks at Hay Festival Kells

I have long bemoaned the fact that across the years of the American Civil War sesquicentennial there has been no Irish conference or series of talks on the Irish experience of the American Civil War. Thankfully that is set to change this year. I am delighted to say that the prestigious Hay Festival in Kells, Co. Meath is dedicating one day of their programme to the Irish in the American Civil War. It promises to be a day to remember for all of those interested in the Irish diaspora, Irish emigration or the 200,000 Irishmen who participated in this conflict. The day-long series of 45 minute lectures will take place on the Carmel Naughton Stage in Kells Church of Ireland on Thursday 25th June. The full line up (which I am honoured to be a part of) can be found below, and you can purchase your tickets here. I hope to see some of you there!

10am: Damian Shiels

Damian Shiels is author of the definitive and highly influential work The Irish in the American Civil War.

11am: Glen Gendzel

American historian Glen Gendzel talks about the story of California in the American Civil War.

12pm: Robert Doyle

Robert Doyle tells the story of Carlow-born Civil War veteran Myles Keogh on the anniversary of his death at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

2pm: Myles Dungan

The presenter of the RTÉ Radio 1 History Show will highlight the life of Oldcastle Civil War veteran, the author and journalist Charles Halpine, and his hilarious creation Myles O’Reilly.

3pm: Tom Bartlett

Thomas Bartlett of Aberdeen University talks about President Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War.

4pm: David Gleeson

David Gleeson (The Green and the Gray) looks at the Irish who fought for the Confederate States of America between 1861 and 1865.

Filed under: Events, Meath Tagged: Hay Festival American Civil War, Hay Festival Kells, Irish American Civil War, Meath Veterans, Myles Dungan, Myles Walter Keogh, Professor David Gleeson, Professor Tom Bartlett

June 1, 2015

The Civil War Letters of Captain James Fleming, Part 4: With Hawkins’ Zouaves at Roanoke

The fourth instalment of letters from James Fleming of Antrim (Find Part 1 here, Part 2 here and Part 3 here) joins the 9th New York in North Carolina with the Burnside expedition of 1862. In the first letter, James provides a detailed description of his part in the Battle of Roanoke Island on 8th February that year. He also responds to his mother’s contention that the Rebels are ‘fighting for their homes.’ His second letter references the Battle of Camden (South Mills) and relates how James feels the war is ‘pretty near over.’ The final letter in this group is perhaps the most interesting. James supplies vivid descriptions of everything from the island’s biting insects to it’s snuff-spitting women. He also provides an intriguing passage referencing the exploits of Meagher’s Irish Brigade. James and Meagher came from different traditions in Ireland, but it is clear that James identified himself very closely with his ‘own countrymen.’ He also makes reference to the United Kingdom’s perceived closeness to the Confederacy in early 1862, and how they needed to be cautious, as the Irish in the Northern States still remembered the Famine: ‘I hope that England will not be so foolish as put her nose into the quarrel in the States at present as the Irish of America have not forgot how English law treated or what caused them to leave their native soil.’

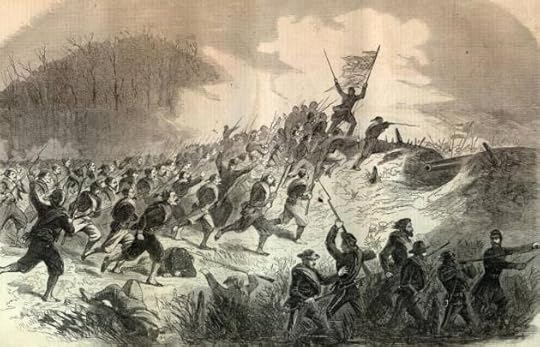

The Charge of Hawkins’ Zouaves at Roanoke Island (Harper’s Weekly)

Roanoak Island

Camp Reno

March 30th 1862

My Dear Father & Mother

I received your welcome letter some time since which gave me great comfort to learn that you were all in perfect health as thank God this leaves me enjoying better health than is possible for a soldier to expect. I am stout healthy & strong as you must know that a soldiers life is less or more exposed to all matters.

Dr mother you wish to know how I live, well I believe I gave you at one time the list of my hours but I live well. I generally keep one servant a man which does my cooking cleaning up my quarters etc. I send my washing to the nearest washerwoman that I can find thats if there is any women around if not I make my servant act in that capacity which you see is a man of all work. My quarters consist of a wood shanty plenty of room for a table two bunks at the one end, one for the Captain and the other for my self also its well ventilated the only difficulty is when it rains it generally rains inside as well as outside but still I am comfortable. You say that I cannot complain. Dear mother you say that the Rebels are fighting for their homes such is not the case they are fighting to separate this great union which never can be done but I suppose before this reaches you you will have heard of what our army has done since last I wrote you. We have been victorious in a great many battles lately. I had my hand tied since last I wrote you. I suppose you may of heard of the gallant charge of Hawkins Zouaves and carrying a masked battery at the point of the Bayonet. I am proud to say I was one of the officers that cheered my men on. If some of my young friends could only see the ground that we had to charge over they would dread to try it without an enemy in their front. I was several times into the middle in water & mud but forward was the cry we carried the day, with only 11 men wounded & 2 officers slightly did not get a single man shot. This was the second day of the fight the 1st day was with the gun boats unto they had to retire for darkness.Only a short time before dark the signal was hoisted to land the troop which we done under the cover of 2 gun boats and darkness. About 2 o’clock in the morning we had about 11,000 men landed we had about 400 yds to walk through mud knee deep. We bivouaked in a large corn field so you can imagine what sort of a sight that number of men was sitting around their fires waiting with patience the coming of the day. The rain all night fell in torrents at daylight we heard firing in our ears. The report was that we were attacked every man grasped his piece determined to punish the rebels for that nights suffering, but it was a false alarm the order was then given to march upon the enemy which we did this was about 7 o’clock am.They had to march about 3 miles before we reached them and as our regiment was held as the reserve we did not get up until 11 o’clock when our side was suffering severely as they had been ordered to charge but refused doing so. As soon as our regiment got within sight of that Battery such another cheer you never heard the like of as their comes the Zouaves we were about 20 minutes under their fire when we received the order to charge and in 15 minutes our stars & stripes was floating over that rebel battery and the rebels flying in every direction. We then pursued taking over 3,500 prisoners and the next morning Roanoak Island was ours one of their strongholds. I received an extra Bar on my shoulder for that days work that was on the 8th of Feby and since that time we are stationed here its a very nice place a great improvement upon Hatteras. You can see how a soldier has to like something for 3 nights I had not off a stich of my clothes the first night I wrapped my blanket which I always carry around me and lay down but soon got rather wet to lay so I walked around the 3rd night was dry I lay this night upon a board one end which I warmed at the camp fire & stitched myself with my blanket around. I got a good sleep that night for 3 hours which satisfied me but I may say that during that time my clothes had not dry [Letter ends, incomplete] (1)

In The Long Roll, Charles Johnson recalled James Fleming in the charge upon the battery at Roanoake, providing an insight into the Irishman’s singularity of purpose during the fight. In the midst of the assault, the regiment’s Major fell into the battery’s defensive ditch and was unable to extricate himself. Johnson remembered that ‘as he [the Major] was floundering and spluttering this way, our Lieutenant Flemming, a six-footer, cleared the ditch with a bound, not hearing or heeding the Major, who frantically called on him to help him out. He afterward explained in my hearing, “Lord, Major, I would not have helped me own father up then.”‘ (2)

Roanoke Island Battleground (The Long Roll)

Camp Reno

Roanoak Island

N C

May 1st 1862

My Dear Father & Mother

I have just received yours of the 23rd March which gives me great pleasure to find you all well and thank God this leaves me at present enjoying good health. We are posted on this Island since the fight which you got the description of. I have been in another one rather warm work but come out victorious once more it was on Easter Saturday & Sunday we started on Friday night and marched about 35 miles meeting the enemy about 2 o’clock on Saturday giving them a good thrashing and returning Saturday night. The fight was severe and our march was long and very tiresome but such is war. On the 4th of this month I will be one year the time is slipping along and I trust to god that it will get along as well the 2nd year. I got promoted after the fight here. Dr mother you must not worry yourself so much concerning me as I am quite safe and I question very much whether our Regiment will ever be engaged in another fight as I think that the war is pretty near over as we have whipped the Rebels in every fight for so far unless Bull Run, and that was only a retreat. I am very glad to hear that my Brothers are doing so well and hope they will continue to do so give them my kind love when you see them. I am not sure whether it was to you or Harry that I wrote my last but I will write a long letter to Harry or Andy next week. Tell Alex that I do not get his papers I have not got a paper from him in some time. I am glad to hear that Agnes & he are doing so well also that Thos had settled, how is he getting along at Muckamore. You say Father & you have suffered from sickness this winter I have escaped winter for one year as I have not seen any scarce cold enough to wear an overcoat and at present quite warm we have a very long day and beautiful weather as this is the most pleasant part of the year and I hope to providence that you and Father has quite recovered again. I suppose that Sarah Jane is a fine girl by this time I send her a kiss–

Dear Mother I have not much more to say. I get letters regular from Mary Ann they are all well she stated in her last that Aunt Mattie & Thos were going home this summer and I wish them a safe passage. Give my love to all my old friends Mrs R & sister & mother also Mr W Rankin & sister and the rest of my acquaintances. Good bye for the present from your very affectionate son

James

The Charge of Hawkins’ Zouaves at Camden (The Long Roll)

Roanoak Island

July 6th 1862

My Dear Father & Mother

Once more I am enabled to embrace the opportunity of writing to you. I received yours of June 4th which gave me great pleasure to know that you are all enjoying that blessing good health as thank God this leaves me at present quite well in fact I never had better health in my life as a soldiers life agrees well with me. We are still in Garrison on Roanoak Island and has very good times not much duty to perform the only annoyance that we have is the muskatoes fleas & woodticks resembling something of a ship lice. We got them off the bushes when we go in the woods and they hang on you like a Bull dog they will continue biting to they get completely under the skin and then they die so you must cut them out if not removed before they get that length so that is the only thing that we have seen in the shape of an enemy in 3 months. So even that vermin like the Rebels I think the hand of providence is against for we have had 3 or 4 very cold days which have removed them from our paths. Colder than it has been for many years. So I sincerely hope by the time you receive this that the last blow will be struck and the Rebels swept out of the United States as we are whipping them some place every day their deserters and prisoners that we take may not to be released as they have neither provisions or clothing they are getting well disheartend. We are sending all of our force to Richmond as all the Regt in this Dept are under marching orders so Dear mother its most likely the next letter I will write you will be from the Rebel Capitol the stronghold of secession we have not got any positive orders but we expect them and suppose its there that we are going. I am proud to inform you that a Brigade of my own Countrymen have distinguished themselves bravely in the different battles they got highly complimented and the general was heard to say with a few more Brigades of such men the war would not last long as it was said by some jealous [?] American when our gallant 69th Irish Regt went out they were only fit to dig trenches but we have proved during the war who is the best defenders of our old flag the Stars & Stripes.There never were troops known to fight better than my own countrymen. I hope that England will not be so foolish as put her nose into the quarrel in the States at present as the Irish of America have not forgot how English law treated or what caused them to leave their native soil. Dear mother I might give you more news concerning my stay and acquaintances upon this Island but pen & ink could scarcely do them justice. I will give you the instance of their Customs the ladies and that is chewing snuff they carry a small brush about the length of your finger that they dip in the snuff and fill their gums full of snuff and then they leave the stick in their mouth with the one end sticking out and so their spit is something resembling what you will see an old tobacco chewer ejecting out of his mouth– and so a great many other customs equally obnoxious to an outside observer but when I pay you a visit I will make you all laugh concerning some of the Country inhabitants customs. Dr mother I am glad to learn from your last that my Brothers are doing so well but I always thought that Andy would be a saving old man I suppose that he would get married but afraid of the expense that the wife would cost. It gives me great pleasure to know that Harry is continuing so well as I hope that he will always be so give them my kind love when you see any of them. I have not write to any of them in some time but will do so soon. I am glad to hear that Thos & Nancy are getting along smoothly and I suppose that Alex & Agnes are doing their best to make a fortune before they die. I heard that she only allowed him to drink one glass of punch in the day, does she still keep him upon his allowance tell her that I said there would be more virtue in two before retiring for the night. I am glad that Sarah and her man is getting along so well as I hope that she may prosper give her my kind love tell her that I have the little piece of poetry that she gave me before I left. Does Malcolm or Mary Ann ever come down to see you or what family has she now. I suppose they are doing well and enjoying the good things of the earth. Now for my old Larne friends hoping that god in his goodness has showered down the good things of earth and his blessing upon them all and that they are happy give them my kind regards as if mentioned separately. I had a letter from Mary Ann a few days ago all enjoying good health also one from Thos Moffat they are all well. I am afraid that it would cost too much for them to go home I expected to have had the pleasure of seeing them before this time but was disappointed. Dr mother since I commenced to write I hear that we are not going to Richmond but merely out upon a recoignance through the country for one week or so if I don’t write again before I start I will as soon as I return. I must now finish did the little bush grow with my father that I sent him – & may god bless you & father the prayer of your son

James (1)

Bivouac of Burnside’s Army, Roanoke Island (The Long Roll)

(1) Louise Brown Transcription; (2) Johnson 1911: 100-1

*The next letters in the series will join James and his regiment in Virginia during the Autumn of 1862. Note that some punctuation has been added to the letters above for ease of reading. Sincere thanks are due to Louise Brown for sharing these letters of her ancestor, which she has also transcribed, with readers of Irish in the American Civil War.

*I am grateful to Michael Zatarga, a researcher of the 9th New York, for drawing my attention to Swedish-born Charles Johnson’s The Long Roll. The account makes frequent mention of Fleming, who Johnson was fond of.

Filed under: Antrim, Battle of Roanoke Island, New York Tagged: 9th New York Infantry, Antrim Veterans, Battle of Roanoke Island, Burnside Expedition, Captain James Fleming, Hawkins' Zouaves, Irish American Civil War, Northern Ireland Veterans

May 23, 2015

‘I Will Sing the Song of Companionship': Peter Doyle– Former Confederate, Walt Whitman’s Muse & Lover

I am very pleased today to have a guest post from historian Liam Hogan. Liam has spent many years exploring this history of Limerick City and County, research that has seen the production of resources such as this site, which examines Limerick 100 years ago, and this interactive map that illustrates the locations where Limerick men died in the First World War. Liam is currently engaged in a detailed examination of the history of Irish slave ownership. Today he shares research he has been carrying out into Peter Doyle– Limerick emigrant, Confederate veteran, and ‘intimate friend’ of famed American poet Walt Whitman:

As Ireland has just debated and voted on a same-sex marriage referendum, it seems like an appropriate time to remember Peter Doyle, an immigrant from Limerick who fought on the Confederate side during the American Civil War and afterwards witnessed the assassination of President Lincoln. But his fame has been ensured because he was also Walt Whitman’s lover and muse for many years.

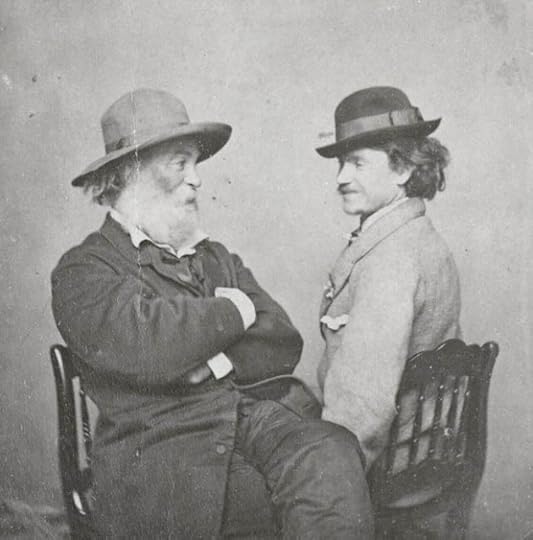

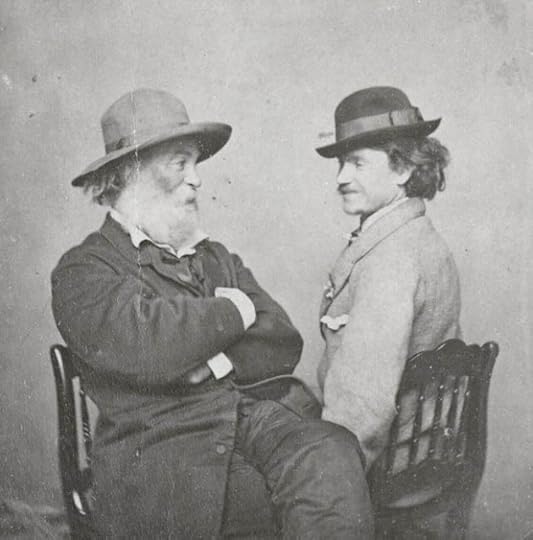

“Walt Whitman and Peter Doyle” (c. 1869) Source: Ohio Wesleyan University, Bayley Collection. Public Domain.

Early Life

Each of us inevitable;

Each of us limitless—each of us with his or her right upon the earth.

– Whitman, Salut au Monde, 11

Peter Doyle was born in St. John’s parish in Limerick City in early June 1843. (1) His parents were Peter Doyle Snr and Catherine Nash, and Peter was their sixth child. In 1852, in the immediate wake of the Great Famine, the Doyle family decided to emigrate to the United States. Peter was just eight years old. Their migration followed an unbearably sad trend as the population of Limerick dropped by over 20 percent between 1841 and 1851. It is not known if this cataclysmic time claimed the lives of two of Peter’s sisters Elizabeth and Mary. They were not aboard the ship and Doyle’s biographer Martin G. Murray did not find evidence that they rejoined their family at a later stage. This voyage was a fraught one and their ship, the William Patten, was nearly lost at sea during a brutal storm.

The Doyle family settled in Alexandria, Virginia where Peter Snr was likely employed as a blacksmith. About six years later they moved to Richmond due to the economic downturn which led to some foundries closing in Alexandria. In Richmond, Peter Snr worked at the Tredegar Iron Works alongside many Irish and German Immigrants as well as African American slaves. (2) The company used slave labour to break a strike in 1847 and from then on they continued to use enslaved persons to reduce their overall operating costs. This foundry became an important supplier of munitions to Confederate forces during the Civil War, furnishing over 1,000 artillery pieces. (3) One wonders what these enslaved persons felt as they were forced to assist in making these weapons, which were used to ensure that they, and their descendants, would be chattel slaves forever more. A review of the Richmond Dispatch informs us that some of the slaves working at the foundry were tortured after stealing some firewood and that at least nine others ran away. (4) This number included an African American named Edmund; like Peter Snr he was also a blacksmith, but instead of being paid for his labour he was hired out to the Tredegar Iron Works on behalf of his owner.

ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD. – Ranaway, about the 15th May, my negro man EDMUND; about 32 years of age; bright mulatto; about 5 feet 8 inches high; a blacksmith; was hired to Jos. R. Anderson; he is very round shouldered, and stands back on his legs when walking; walks very fast, and stammers slightly when talking; when last seen he was on Shockoe Hill. I will give the above reward if delivered to A. Y. STOKES & CO., Richmond, or delivered in jail, so I can get him.

WM. ROBINSON

Danville, Va.

(from the Richmond Dispatch 9/2/1862)

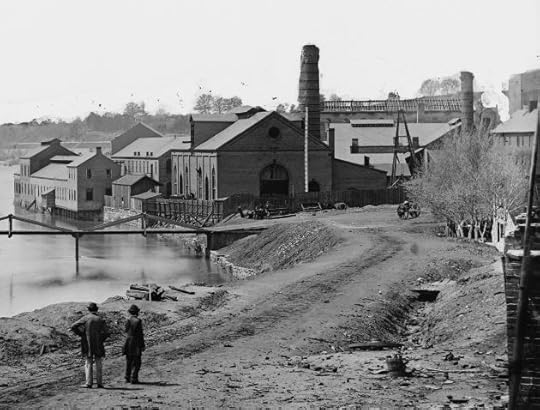

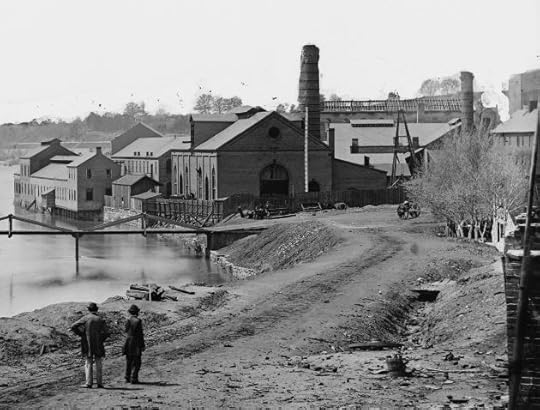

“Photograph of the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia after its fall” (April 1865) Source: Library of Congress. Public Domain

Doyle’s role during the American Civil War

“It was not a quadrille in a ballroom.”

– Whitman, Memoranda

Peter enlisted with the Richmond Fayette Artillery in April 1861 when he was seventeen years old, serving alongside ten other Irish-born men. (5) Doyle’s seventeen month involvement with this light artillery battalion included the Siege of Yorktown, the Battle of Seven Pines, and the Seven Days Campaign. His military experience culminated in the bloodiest single-day battle in American history at Antietam on the 17 September 1862. He was injured in this battle and sent back to hospital in Richmond to receive treatment.

“Photograph taken by Alexander Gardner of the field at Antietam, American Civil War. Confederate dead by a fence at the Hagerstown Turnpike, looking north.” (1 Sep 1862) Source: Library of Congress. Public Domain. Note: Coincidentally, fighting with the Union forces that same day was George Washington Whitman, Walt Whitman’s brother.

While there he successfully sought a discharge based on a string “of truths and half-truths” and he never returned to the field of battle. Interviewed by Richard Maurice Bucke over thirty years later, Doyle spoke very little about his military service or how he ended up in Washington D.C. in 1863.*(6) Whether he was still traumatised by the experience or just blocked it out, we do not know. Murray contends that Doyle’s motivation for seeking a discharge was due to a “combination of war weariness and illness.” (7) According to Murray, Doyle’s battalion had “engaged in arguably the most demanding series of battles fought during the war” which included the aforementioned bloodbath at Antietam. His illness, while not specified, was clearly a serious one as “even after [he] received his discharge, his service record continues to show him as spending time in military hospitals.” When fully recovered he clearly had enough of the war and fled North where was apprehended by Union forces who imprisoned him in Washington D.C. as an unauthorised “insurgent.” Doyle pleaded that he was a British subject and a refugee from the South. He was released on 11 May 1863 after swearing an oath not to aid the Confederacy. So began his new life in Washington D.C.

Witnessing Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

But before moving on to discuss Doyle and Whitman’s relationship, I must include Doyle’s first hand account of a seismic moment in American history. When interviewed by Bucke in 1895, Doyle revealed that he was indeed present in Ford’s Theatre when President Lincoln was assassinated by the Southern white supremacist, John Wilkes Booth.

“Walt was not at the theatre the night Lincoln was shot. It was me he got all that from in the book they are almost my words. I heard that the President and his wife would be present and made up my mind to go. There was a great crowd in the building. I got into the second gallery. There was nothing extraordinary in the performance. I saw everything on the stage and was in a good position to see the President’s box. I heard the pistol shot. I had no idea what it was, what it meant—it was sort of muffled. I really knew nothing of what had occurred until Mrs. Lincoln leaned out of the box and cried, “The President is shot!” I needn’t tell you what I felt then, or saw. It is all put down in Walt’s piece—that piece is exactly right. I saw Booth on the cushion of the box, saw him jump over, saw him catch his foot, which turned, saw him fall on the stage. He got up on his feet, cried out something which I could not hear for the hub-hub and disappeared. I suppose I lingered almost the last person.” (8)

Doyle was certain that his account of that night directly influenced Whitman’s description of Lincoln’s death as featured in his Memoranda During the War. (9) Murray contends that while Doyle may have not inspired the Drum Taps war poems directly “he at least reinforced the feelings underlying them.”(10)

Doyle’s relationship with Walt Whitman

“All I have to say is – to say nothing – only a good smacking kiss, & many of them…” - Whitman to Doyle, The Correspondence, 2:110

Peter Doyle had settled down in Washington D.C. and worked as a horse-car conductor. It was in 1865 while driving one of theses cars that Doyle first met Whitman. He recounted the genesis of their relationship to Bucke.

“You ask where I first met him? It is a curious story. We felt to each other at once. I was a conductor. The night was very stormy, he had been over to see Burroughs before he came down to take the car the storm was awful. Walt had his blanket it was thrown round his shoulders he seemed like an old sea-captain. He was the only passenger, it was a lonely night, so I thought I would go in and talk with him. Something in me made me do it and something in him drew me that way. He used to say there was something in me had the same effect on him. Anyway, I went into the car. We were familiar at once I put my hand on his knee we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip in fact went all the way back with me…[…]…From that time on we were the biggest sort of friends…[…]…Walt rode with me often often at noon, always at night. He rode round with me on the last trip sometimes rode for several trips. Everybody knew him.” (11)

For the next eight years Whitman and Doyle were lovers. Clearly the couple were infatuated with each other and they expressed themselves by writing a torrent of letters whenever they were apart. Doyle’s collection of these letters were published by Bucke in 1895. They are fascinating to read; instead of exhibiting his usual literary flair, Whitman’s correspondence with Doyle was often plain, direct, passionate and uninhibited. Henry James noted that they celebrated “the beauty of the natural”. From a distance the two men appear to be opposites, the intellectual and the labourer. Yet these letters make that assumption appear frivolous, for they reveal the common ground of mutual affection that existed between these two men; and the words themselves revel in life at its most unassuming.

Considering the level of prejudice that existed in the nineteenth century around same-sex relations, Murray rightfully argues that Doyle “deserves considerable credit for the courage he showed in agreeing to the publication of this revealing correspondence.” (12) Low and behold, Peter was apparently seen as the “black sheep” in his extended family from the moment the book appeared in print.

In my view the most affecting passage of the Doyle interview is when he explains why he could not be at Whitman’s side as the end neared. He had personally nursed Whitman during his bout of illness in 1873 (this was just before the poet left Washington for good) but now the old man was in a different place, with a whole host of different attendants. An entourage of sorts. The intimacy was now broken, but the love remained.

“Towards the end I saw very little of Walt, but he continued to write me. He never altered his manner toward me; here are a few more recent postal cards, you will see that they show the same old love. I know he wondered why I saw so little of him the three or four years before he died, but when I explained it to him he understood. Nevertheless, I am sorry for it now. The obstacles were too small to have made the difference I allowed. It was only this: In the old days I had always open doors to Walt going, coming, staying, as I chose. Now, I had to run the gauntlet of Mrs. Davis and a nurse and what not. Somehow, I could not do it. It seemed as if things were not as they should have been. Then I had a mad impulse to go over and nurse him. I was his proper nurse he understood me I understood him. We loved each other deeply, but there were things preventing that, too. I saw them. I should have gone to see him, at least, in spite of everything. I know it now, I did not know it then, but it is all right. Walt realised I never swerved from him, he knows it now, that is enough.” (13)

You will be glad to know that this final sentiment was not wishful thinking on Doyle’s part. It was confirmed in a sense in 1888, when Whitman was bed bound and severely ill. He was reminiscing on his dearest companion by reading some of ‘Pete’s’ letters. They evidently still brought a smile to his face. Whitman turned to his chronicler and told him that he believed Doyle encapsulated “the real Irish character, the higher samples of it, […] how noble, tenacious, loyal, they are!” (14)

Peter Doyle died on the 19 April 1907 in Philadelphia aged 63.

Dedicated to Sean and Kieran

Congressional Cemetery, Washington D.C., where Pete was buried following his death in 1907 (Library of Congress)

Notes:

If you wish to read a detailed biography of Peter Doyle upon which this blog has relied, look no further than Martin G. Murray’s paper which can be accessed here http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/anc.00155.html

Limerick readers should note that The Collegians by Gerald Griffin was one of Walt Whitman’s favourite novels. He said “it was a beautiful study of Irish life, Irish characters…[…]…some of the few novels I have read stick to me like gum arabic – won’t let go. The Collegians was one of them..”

*Doyles service record contains the affidavit he supplied regarding his British citizenship, in which he related that he only came to Richmond from Washington D.C. in 1860. This affidavit seems to have been questioned by Confederate authorities, and given what we know of Doyle’s life, it appears he may have been deliberately untruthful in an effort to secure his exemption.

Citations

Murray, 1994 (2) Bucke, 1897 (3) Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 1976 (4) Civil War Richmond, 2008 (5) Murray (6) Bucke (7) Murray (8) Bucke (9) Whitman, 1875 (10) Murray (11) Bucke, p.23 (12) Murray (13) Bucke, p. 32 (14) Krieg, introduction

References & Further Reading

Bucke, Richard Maurice, Whitman, Walt. Calamus: A Series of Letters Written During the Years 1868–1880 by Walt Whitman to a Young Friend (Peter Doyle), 1897.

Civil War Richmond, Information about the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, VA during the Civil War URL: http://www.mdgorman.com/Other_Sites/tredegar_iron_works.htm, 2008

Krieg, Johann P. Whitman and the Irish, 2000.

Murray, Martin G. “Pete the Great: A Biography of Peter Doyle”, Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 12 (Summer 1994), pp. 1-51

Pollak, Vivian R. The Erotic Whitman, 2000.

Le Master, J.R., Kummings, Donald K.(ed), The Routledge Encyclopaedia of Walt Whitman, 2013.

Virginia Department of Historic Resources, ”Tredegar Iron Works National Historic Landmark nomination”, 1976 http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/Richmond/127-0186_TredegarIronWorks_1976_Nomination_NHL.pdf

Whitman, Walt. Memoranda During The War: and Death of Abraham Lincoln, 1875.

Filed under: Guest Post, Limerick Tagged: American Poetry, Irish American Civil War, Irish Confederates, Limerick Emigrants, Peter Doyle and Walt Whitman, Sexuality in the 19th Century, Walt Whitman Letters, Walt Whitman Sexuality

‘I Will Sing the Song of Companionship': Limerick’s Peter Doyle, the Former Confederate Who Became Walt Whitman’s Muse & Lover

I am very pleased today to have a guest post from historian Liam Hogan. Liam has spent may years exploring this history of Limerick City and County, research that has seen the production of resources such as this site, which examines Limerick 100 years ago, and this interactive map that illustrates the locations where Limerick men died in the First World War. Liam is currently engaged in a detailed examination of the history of Irish slave ownership. Today he shares research he has been carrying out into Peter Doyle– Limerick emigrant, Confederate veteran, and ‘intimate friend’ of famed American poet Walt Whitman:

As Ireland has just debated and voted on a same-sex marriage referendum, it seems like an appropriate time to remember Peter Doyle, an immigrant from Limerick who fought on the Confederate side during the American Civil War and afterwards witnessed the assassination of President Lincoln. But his fame has been ensured because he was also Walt Whitman’s lover and muse for many years.

“Walt Whitman and Peter Doyle” (c. 1869) Source: Ohio Wesleyan University, Bayley Collection. Public Domain.

Early Life

Each of us inevitable;

Each of us limitless—each of us with his or her right upon the earth.

– Whitman, Salut au Monde, 11

Peter Doyle was born in St. John’s parish in Limerick City in early June 1843. (1) His parents were Peter Doyle Snr and Catherine Nash, and Peter was their sixth child. In 1852, in the immediate wake of the Great Famine, the Doyle family decided to emigrate to the United States. Peter was just eight years old. Their migration followed an unbearably sad trend as the population of Limerick dropped by over 20 percent between 1841 and 1851. It is not known if this cataclysmic time claimed the lives of two of Peter’s sisters Elizabeth and Mary. They were not aboard the ship and Doyle’s biographer Martin G. Murray did not find evidence that they rejoined their family at a later stage. This voyage was a fraught one and their ship, the William Patten, was nearly lost at sea during a brutal storm.

The Doyle family settled in Alexandria, Virginia where Peter Snr was likely employed as a blacksmith. About six years later they moved to Richmond due to the economic downturn which led to some foundries closing in Alexandria. In Richmond, Peter Snr worked at the Tredegar Iron Works alongside many Irish and German Immigrants as well as African American slaves. (2) The company used slave labour to break a strike in 1847 and from then on they continued to use enslaved persons to reduce their overall operating costs. This foundry became an important supplier of munitions to Confederate forces during the Civil War, furnishing over 1,000 artillery pieces. (3) One wonders what these enslaved persons felt as they were forced to assist in making these weapons, which were used to ensure that they, and their descendants, would be chattel slaves forever more. A review of the Richmond Dispatch informs us that some of the slaves working at the foundry were tortured after stealing some firewood and that at least nine others ran away. (4) This number included an African American named Edmund; like Peter Snr he was also a blacksmith, but instead of being paid for his labour he was hired out to the Tredegar Iron Works on behalf of his owner.

ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD. – Ranaway, about the 15th May, my negro man EDMUND; about 32 years of age; bright mulatto; about 5 feet 8 inches high; a blacksmith; was hired to Jos. R. Anderson; he is very round shouldered, and stands back on his legs when walking; walks very fast, and stammers slightly when talking; when last seen he was on Shockoe Hill. I will give the above reward if delivered to A. Y. STOKES & CO., Richmond, or delivered in jail, so I can get him.

WM. ROBINSON

Danville, Va.

(from the Richmond Dispatch 9/2/1862)

“Photograph of the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia after its fall” (April 1865) Source: Library of Congress. Public Domain

Doyle’s role during the American Civil War

“It was not a quadrille in a ballroom.”

– Whitman, Memoranda

Peter enlisted with the Richmond Fayette Artillery in April 1861 when he was seventeen years old, serving alongside ten other Irish-born men. (5) Doyle’s seventeen month involvement with this light artillery battalion included the Siege of Yorktown, the Battle of Seven Pines, and the Seven Days Campaign. His military experience culminated in the bloodiest single-day battle in American history at Antietam on the 17 September 1862. He was injured in this battle and sent back to hospital in Richmond to receive treatment.

“Photograph taken by Alexander Gardner of the field at Antietam, American Civil War. Confederate dead by a fence at the Hagerstown Turnpike, looking north.” (1 Sep 1862) Source: Library of Congress. Public Domain. Note: Coincidentally, fighting with the Union forces that same day was George Washington Whitman, Walt Whitman’s brother.

While there he successfully sought a discharge based on a string “of truths and half-truths” and he never returned to the field of battle. Interviewed by Richard Maurice Bucke over thirty years later, Doyle spoke very little about his military service or how he ended up in Washington D.C. in 1863.*(6) Whether he was still traumatised by the experience or just blocked it out, we do not know. Murray contends that Doyle’s motivation for seeking a discharge was due to a “combination of war weariness and illness.” (7) According to Murray, Doyle’s battalion had “engaged in arguably the most demanding series of battles fought during the war” which included the aforementioned bloodbath at Antietam. His illness, while not specified, was clearly a serious one as “even after [he] received his discharge, his service record continues to show him as spending time in military hospitals.” When fully recovered he clearly had enough of the war and fled North where was apprehended by Union forces who imprisoned him in Washington D.C. as an unauthorised “insurgent.” Doyle pleaded that he was a British subject and a refugee from the South. He was released on 11 May 1863 after swearing an oath not to aid the Confederacy. So began his new life in Washington D.C.

Witnessing Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

But before moving on to discuss Doyle and Whitman’s relationship, I must include Doyle’s first hand account of a seismic moment in American history. When interviewed by Bucke in 1895, Doyle revealed that he was indeed present in Ford’s Theatre when President Lincoln was assassinated by the Southern white supremacist, John Wilkes Booth.

“Walt was not at the theatre the night Lincoln was shot. It was me he got all that from in the book they are almost my words. I heard that the President and his wife would be present and made up my mind to go. There was a great crowd in the building. I got into the second gallery. There was nothing extraordinary in the performance. I saw everything on the stage and was in a good position to see the President’s box. I heard the pistol shot. I had no idea what it was, what it meant—it was sort of muffled. I really knew nothing of what had occurred until Mrs. Lincoln leaned out of the box and cried, “The President is shot!” I needn’t tell you what I felt then, or saw. It is all put down in Walt’s piece—that piece is exactly right. I saw Booth on the cushion of the box, saw him jump over, saw him catch his foot, which turned, saw him fall on the stage. He got up on his feet, cried out something which I could not hear for the hub-hub and disappeared. I suppose I lingered almost the last person.” (8)

Doyle was certain that his account of that night directly influenced Whitman’s description of Lincoln’s death as featured in his Memoranda During the War. (9) Murray contends that while Doyle may have not inspired the Drum Taps war poems directly “he at least reinforced the feelings underlying them.”(10)

Doyle’s relationship with Walt Whitman

“All I have to say is – to say nothing – only a good smacking kiss, & many of them…” - Whitman to Doyle, The Correspondence, 2:110

Peter Doyle had settled down in Washington D.C. and worked as a horse-car conductor. It was in 1865 while driving one of theses cars that Doyle first met Whitman. He recounted the genesis of their relationship to Bucke.

“You ask where I first met him? It is a curious story. We felt to each other at once. I was a conductor. The night was very stormy, he had been over to see Burroughs before he came down to take the car the storm was awful. Walt had his blanket it was thrown round his shoulders he seemed like an old sea-captain. He was the only passenger, it was a lonely night, so I thought I would go in and talk with him. Something in me made me do it and something in him drew me that way. He used to say there was something in me had the same effect on him. Anyway, I went into the car. We were familiar at once I put my hand on his knee we understood. He did not get out at the end of the trip in fact went all the way back with me…[…]…From that time on we were the biggest sort of friends…[…]…Walt rode with me often often at noon, always at night. He rode round with me on the last trip sometimes rode for several trips. Everybody knew him.” (11)

For the next eight years Whitman and Doyle were lovers. Clearly the couple were infatuated with each other and they expressed themselves by writing a torrent of letters whenever they were apart. Doyle’s collection of these letters were published by Bucke in 1895. They are fascinating to read; instead of exhibiting his usual literary flair, Whitman’s correspondence with Doyle was often plain, direct, passionate and uninhibited. Henry James noted that they celebrated “the beauty of the natural”. From a distance the two men appear to be opposites, the intellectual and the labourer. Yet these letters make that assumption appear frivolous, for they reveal the common ground of mutual affection that existed between these two men; and the words themselves revel in life at its most unassuming.

Considering the level of prejudice that existed in the nineteenth century around same-sex relations, Murray rightfully argues that Doyle “deserves considerable credit for the courage he showed in agreeing to the publication of this revealing correspondence.” (12) Low and behold, Peter was apparently seen as the “black sheep” in his extended family from the moment the book appeared in print.

In my view the most affecting passage of the Doyle interview is when he explains why he could not be at Whitman’s side as the end neared. He had personally nursed Whitman during his bout of illness in 1873 (this was just before the poet left Washington for good) but now the old man was in a different place, with a whole host of different attendants. An entourage of sorts. The intimacy was now broken, but the love remained.

“Towards the end I saw very little of Walt, but he continued to write me. He never altered his manner toward me; here are a few more recent postal cards, you will see that they show the same old love. I know he wondered why I saw so little of him the three or four years before he died, but when I explained it to him he understood. Nevertheless, I am sorry for it now. The obstacles were too small to have made the difference I allowed. It was only this: In the old days I had always open doors to Walt going, coming, staying, as I chose. Now, I had to run the gauntlet of Mrs. Davis and a nurse and what not. Somehow, I could not do it. It seemed as if things were not as they should have been. Then I had a mad impulse to go over and nurse him. I was his proper nurse he understood me I understood him. We loved each other deeply, but there were things preventing that, too. I saw them. I should have gone to see him, at least, in spite of everything. I know it now, I did not know it then, but it is all right. Walt realised I never swerved from him, he knows it now, that is enough.” (13)

You will be glad to know that this final sentiment was not wishful thinking on Doyle’s part. It was confirmed in a sense in 1888, when Whitman was bed bound and severely ill. He was reminiscing on his dearest companion by reading some of ‘Pete’s’ letters. They evidently still brought a smile to his face. Whitman turned to his chronicler and told him that he believed Doyle encapsulated “the real Irish character, the higher samples of it, […] how noble, tenacious, loyal, they are!” (14)

Peter Doyle died on the 19 April 1907 in Philadelphia aged 63.

Dedicated to Sean and Kieran

Congressional Cemetery, Washington D.C., where Pete was buried following his death in 1907 (Library of Congress)

Notes:

If you wish to read a detailed biography of Peter Doyle upon which this blog has relied, look no further than Martin G. Murray’s paper which can be accessed here http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/anc.00155.html

Limerick readers should note that The Collegians by Gerald Griffin was one of Walt Whitman’s favourite novels. He said “it was a beautiful study of Irish life, Irish characters…[…]…some of the few novels I have read stick to me like gum arabic – won’t let go. The Collegians was one of them..”

*Doyles service record contains the affidavit he supplied regarding his British citizenship, in which he related that he only came to Richmond from Washington D.C. in 1860. This affidavit seems to have been questioned by Confederate authorities, and given what we know of Doyle’s life, it appears he may have been deliberately untruthful in an effort to secure his exemption.

Citations

Murray, 1994 (2) Bucke, 1897 (3) Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 1976 (4) Civil War Richmond, 2008 (5) Murray (6) Bucke (7) Murray (8) Bucke (9) Whitman, 1875 (10) Murray (11) Bucke, p.23 (12) Murray (13) Bucke, p. 32 (14) Krieg, introduction

References & Further Reading

Bucke, Richard Maurice, Whitman, Walt. Calamus: A Series of Letters Written During the Years 1868–1880 by Walt Whitman to a Young Friend (Peter Doyle), 1897.

Civil War Richmond, Information about the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, VA during the Civil War URL: http://www.mdgorman.com/Other_Sites/tredegar_iron_works.htm, 2008

Krieg, Johann P. Whitman and the Irish, 2000.

Murray, Martin G. “Pete the Great: A Biography of Peter Doyle”, Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 12 (Summer 1994), pp. 1-51

Pollak, Vivian R. The Erotic Whitman, 2000.

Le Master, J.R., Kummings, Donald K.(ed), The Routledge Encyclopaedia of Walt Whitman, 2013.

Virginia Department of Historic Resources, ”Tredegar Iron Works National Historic Landmark nomination”, 1976 http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/registers/Cities/Richmond/127-0186_TredegarIronWorks_1976_Nomination_NHL.pdf

Whitman, Walt. Memoranda During The War: and Death of Abraham Lincoln, 1875.

Filed under: Guest Post, Limerick Tagged: American Poetry, Irish American Civil War, Irish Confederates, Limerick Emigrants, Peter Doyle and Walt Whitman, Sexuality in the 19th Century, Walt Whitman Letters, Walt Whitman Sexuality

May 6, 2015

New Ballymote Monument to Irish of the American Civil War

Towards the end of April I received notification that a new monument dedicated to Irish soldiers of the American Civil War is being unveiled in Ballymote, Co. Sligo next weekend. This is a positive step in what has been, up to this point, extremely disappointing engagement in Ireland with the history and heritage of her diaspora. Hopefully following this move the Government will be inspired to make a small effort towards appropriately remembering the hundreds of thousands of Irish emigrants impacted by the war on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the conflict’s end. The Taoiseach has been invited to unveil the statue this coming Saturday, May 9th, in the presence of the U.S. Ambassador to Ireland. More details on the event are contained within the Press Release below (where it is good to see my recent estimate of 200,000 Irish taking hold!).

The new Ballymote Monument

MONUMENT TO THE MEMORY OF IRISH SOLDIERS WHO SERVED AND DIED DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR TO BE UNVEILED- PERRY

Fine Gael TD for Sligo/North Leitrim, John Perry, has today (Wednesday) announced that a new national monument dedicated to the honour and lasting memory of Irish emigrants and people of Irish heritage who served and died during the American Civil War, will be unveiled at Ballymote, Co. Sligo.

The ceremony is scheduled for Saturday May 9th, the 150th anniversary of the day that President Johnson officially declared a cessation of military actions, marking an end to the American Civil War. The proposed monument takes the form of a statue of a soldier on horseback upon a stone plinth. The monument will bear an inscription paying tribute to the many thousands of Irish who fought and died. The Memorial Site is located adjacent to Ireland’s National Monument to the 69th Regiment, and Brigadier General, Michael Corcoran. The official unveiling will be performed by An Taoiseach, Enda Kenny, TD. The ceremony is scheduled to begin at 14.45.

Commenting on the project, Deputy Perry said that “The 150th Anniversary of the ending of the American Civil War is a suitable occasion to mark the Irish contribution to the United States at a significant point in its history.”

“When the American Civil War started, the recent Irish famine emigrants together with earlier emigrants of Irish heritage answered the call to arms. At least 200,000 Irish soldiers served in the armies of the North and the South; the significant majority of them serving in the Union Army.”

“With the unveiling of this new monument to commemorate the Irish contribution during the American Civil War, we enhance public understanding of the prominent contribution made by people that left Ireland and served in the War on both sides and we broaden our links to the wider Irish American community.”

“We shared with the citizens of the United States in one of its most painful periods. The bonds of heritage and shared history that join our two countries together run very deeply. In unveiling and dedicating a monument to recognise the Irish participation in the American Civil War, we remember all those brave Irish soldiers and the sacrifice they made in the interests of their adopted homeland.”

Filed under: Memory Tagged: 69th New York, Ballymote Memorial, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Irish American Civil War, Irish American Civil War Memorial, John Perry TD, Michael Corcoran, Sligo in the Civil War

Edward Wellington Boate: The Andersonville POW Who Came to the Defence of Henry Wirz

Waterford’s Edward Wellington Boate belongs to the large cohort of Irish journalists who ended up fighting, or in someway participating, in the American Civil War. His story is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating. A member of the Tammany regiment, the 42nd New York, his capture and incarceration as a POW set him on a path that would eventually see him not only rail against the Lincoln administration, but also come to the support of the loathed Andersonville Commander Henry Wirz. It was an association from which his reputation would never recover. Friend of the site James Doherty has researched Boate’s story and shares his work with us in the guest post below.

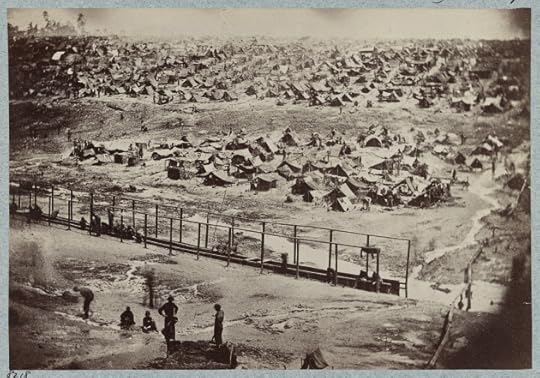

Andersonville as it appeared on 17th August 1864 (Library of Congress)

Edward Wellington Boate was born in Waterford in 1822. He came from a relatively well to do family, with his father working as a Land Waiter (a type of customs official) who would later rise to the position of Port Surveyor. In his early life Boate would pursue a career as a journalist working for the Waterford Chronicle and Wexford Guardian. He married Henrietta Bruce O’Neill in Wexford in 1849 and later moved to London, where he acted as the foreign correspondent for the Wexford Guardian. His career continued to prosper in England, where he worked for the Times as a Parliamentary correspondent and also spent time in the Passport Office. (1)

Sometime around 1861 Boate and his family (by now he had two children) moved to the United States, where he again pursued a career as a journalist. His reasons for joining the army are unknown, but perhaps he felt that he wanted to part of the news rather than just reporting on it.

In the summer of 1863 he joined the 42nd New York Volunteers, a strongly democratic regiment organised by the Tammany Society. Interestingly the Waterford man had joined the Union army using an alias; he enlisted under the name of Edward W Bates. Soldiers fought under aliases for many reasons, some due to previous desertion from other units or armies, some in order to escape past events. In the case of Boate we can only guess. Perhaps due to his background and unusual surname, he wanted to choose a more common name to fit in with the rest of his unit? (2)

Unfortunately for Boate his military career in the field did not last long. He first saw action at the Battle of Bristoe Station on 14th October 1863, a one-sided affair where a blunder by Confederate General A.P Hill saw Southern troops attack a well defended Union position. In the action the Confederacy lost over 1400 men dead wounded or captured whereas Union casualties ran to just over 500. (3)

Sketch of the Battle of Bristoe Station by Alfred Waud. Edward Wellington Boate was captured at the engagement (Library of Congress)

One of the captured Federal troops was Edward Wellington Boate. He was initially sent to the Confederate prison camp at Belle Isle and was later transferred to Camp Sumter at Andersonville, Georgia. Andersonville prison camp was built 18 months before the end of the Civil War to hold Union Army prisoners captured by Confederate forces. Located deep behind Confederate lines, the 26.5-acre site was designed for a maximum of 10,000 men. At its most crowded, it held more than 32,000– many of them wounded and starving, living in horrific conditions with rampant disease, contaminated water, and only minimal shelter from the elements. In the prison’s 14 months of existence, some 45,000 Union prisoners arrived there; of those, 12,920 died and were buried in the prison cemetery. (4)

The horrendous conditions in the camp and the causes of these conditions would become a central theme in the rest of Edward Wellington Boate’s life. Even today the topic is controversial; while the conditions suffered in the camp are not disputed, the causes behind them most certainly are. Some believe that the Confederate authorities could and should have done more for the prisoners. On the other hand others argue that the appalling conditions were a direct result of the Union blockade of Southern ports, and that the guards in camps like Andersonville were little better off than the prisoners.

Edward Wellington Boate fell firmly into the latter camp and argued strongly after the war that conditions in Andersonville were a direct consequence of the actions of his own Federal government. After his release Boate published an article in the New York News that was a damning indictment of the government of President Abraham Lincoln:

‘But our men were great sufferers, and deaths were alarmingly on the increase. The Confederate doctors were, as I have already said, themselves startled and alarmed at the progress of disease and death. But they seemed powerless to check it…We were often a fortnight without being able to get medicine. They had no quinine for fever and ague; they had no opium for diarrhea and dysentery.

Our government made medicine a contraband of war, and wherever they found medicine on a blockade runner, it was confiscated, a policy which indicated, on the part of our rulers, both ignorance and barbaric cruelty; for, although no amount of medicine would save many of our men who have laid their bones in Georgia, I am as certain as I am of my own existence, that hundreds of men died, who, if we had the right sort and proper quantity of medicine, would have been living today and restored to their families.

Why, the Confederate authorities were suffering many a privation at Andersonville. The surgeons who were in attendance upon the sick had not decent hose or stockings; their shoes and boots being in many instances so patched, that the original leather out of which they had been manufactured had become invisible.’ (5)

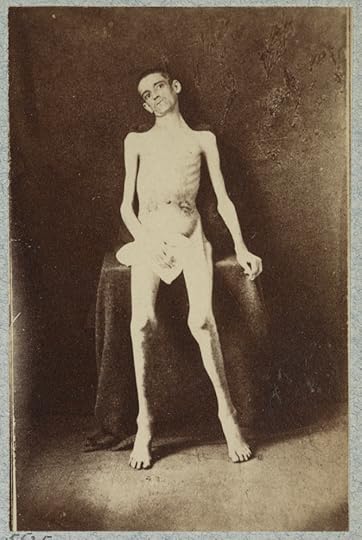

One of the famed photos of emaciated Union prisoners, showing the hardships many of them faced. Although often associated with Andersonville, the majority of these soldiers had been incarcerated at Belle Isle. Research by the NPS has identified this as William Smith of the 8th Kenctucky, who had been captured at Chickamauga (Library of Congress)

In addition to blaming the Union government for the conditions in the camp, Boate went a step further. He defended the character of the Andersonville commandant Henry Wirz, who would go on to be charged with war crimes after the American Civil War:

‘Let me refer to Captain Wirz, the Commandant of the prison, who was generally regarded as being very harsh. But his position should be considered. He was a mere keeper of prisoners – a work which can never be popular…Between the jailer and the jailed, there could not and never can be any peculiar love; but, under a rough exterior, more often assumed then left, this Captain Wirz was as kind – hearted a man as I ever met.’ (6)

As if the conditions in Andersonville had not been bad enough, a criminal group of prisoners called the ‘Andersonville Raiders’ terrorised other members of the prison population. They preyed on the weak and new prison entrants. Estimates vary, but the strength of the Raiders was probably around one hundred men. As they grew bolder and more violent a prison police force was formed (with the permission of Commandant Wirz) which resolved to deal with the Raiders.

Between the 29th June and 1st July 1864 the prison police force violently confronted the Raiders. They seized their leaders (which included a number of Irish), who were placed outside the stockade walls for their own protection. Some of the Raiders received summary justice as they were forced to run a gauntlet receiving kicks and blows from their vengeful fellow prisoners. Six of the main gang leaders were placed on trial (by their fellow prisoners) and hanged for their crimes. They rest today in a separate area of the prison cemetery. The trial of the Raiders was recorded (due to his clerical skills) by Edward Wellington Boate. (7)

Shortly after the trial of the ‘Andersonville Raiders’ was concluded Boate was chosen by Commandant Wirz to be part of a delegation that would be allowed leave the prison and travel north to meet with President Lincoln. The purpose of this delegation was to appeal for better conditions in the prison and a wholesale prisoner exchange. Boate was one of twenty-one men allowed to make the journey, and on the 7th August 1864 that were to be exchanged with a similar number of Confederate troops. Six of this group were to then meet the President bearing a petition that appealed for the Union authorities to allow supplies through to Andersonville and also calling for wholesale prisoner exchange. Boate fell ill before reaching Washington and passed the petition to another member of the delegation. The group never got to meet President Lincoln and the circumstances behind this failed envoy mission would be hotly debated hotly after the war. (8)

Although his delegation was unsuccessful Boate did not have to wait too long to see the prisoners of Andersonville released. When the Union forces under General Sherman occupied Atlanta in September 1864 it put Union troops within striking range of the camp. The Confederate forces moved the main body of prisoners to different locations out of range of the Union Cavalry. However even when the war entered its dying days Andersonville continued to operate, albeit on a smaller scale, and remained open until April 1865.

The Union forces did not waste time when it came to Commandant Wirz. He was arrested in May 1865 and his trial for the alleged needless deaths of Union prisoners began on the 23rd August 1865. By this stage Edward Wellington Boate had publicly expressed his misgivings on how President Lincoln’s government had handled the issue of the prison camps– soon he would be called as a witness for the defence in the trial of former gaoler Henry Wirz.

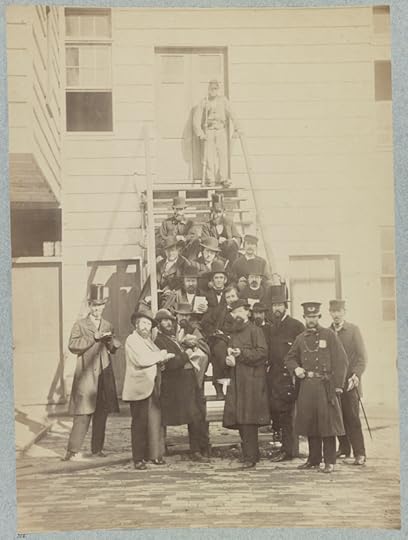

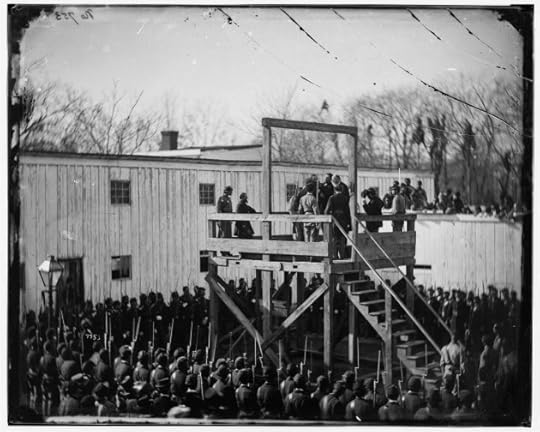

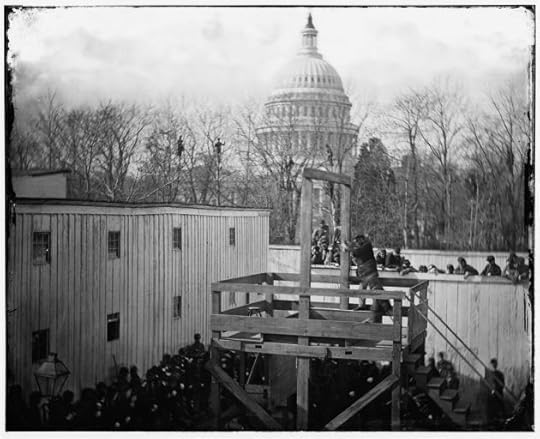

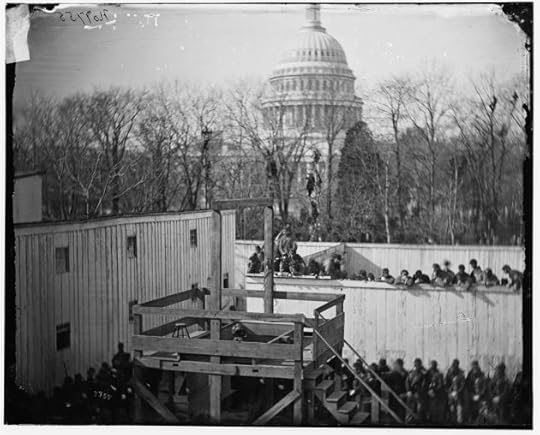

News reporters viewing the execution of the sentence against Henry Wirz (Library of Congress)

The trial of Henry Wirz was recorded in detail and Boate’s testimony was hotly contested. Boate attested that the conditions in the camp had been nearly as difficult for the guards as they were for the prisoners, and also testified as to the good character of Henry Wirz. A highly contentious part of Boate’s testimony revolved around the failed humanitarian mission and the fact that Union authorities wouldn’t meet his delegation. By the time of the trial the original petition had disappeared and the Union authorities denied ever receiving it. Wirz’s defence argued that the existence of the delegation and the refusal of the Union authorities to meet with them proved that Henry Wirz was not solely responsible for the horrors of Andersonville. This was simply too much for the prosecution Judge Advocate. He stated:

To prove, in this unheard-of way, a fact which can scarcely be believed of a man whose name and fame are so unstained and so unimpeachable as that of President Lincoln. That this committee were refused a conference with the late President upon a subject of this kind is improbable, and I may say preposterous.This court must not allow a slandel (sic.) of that kind against the memory of so great and good a man as President Lincoln to be repeated by this witness who has no knowledge of the facts. (9)

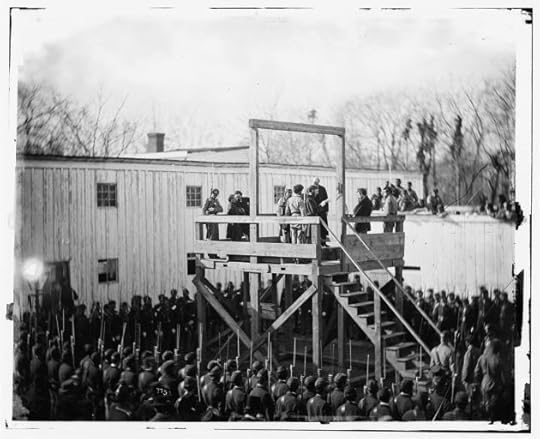

Alexander Gardner captured a series of images of Henry Wirz’s execution in Washington D.C. on 10th November 1865. Here the Death Warrant is being read to Wirz on the Scaffold (Library of Congress)

Boate’s testimony was wide-ranging and covered incidents of alleged cruelty to prisoners, the issue of the ‘Andersonville Raiders’, availability of medicine and offers made by Union soldiers to join the Confederate Army amongst other topics. But despite this and the best efforts of his defence team Henry Wirz was convicted. The findings of the court run into pages but the paragraph below gives an idea of the mood of the military tribunal, which found Wirz guilty of conspiring to:

Impair and injure the health and to destroy the lives, by subjecting to torture. and great suffering, by coufining (sic) in unhealthy and unwholesome quarters, by exposing, to the inclemency of winter and to the burning suns of summer, by compelling the use of impure water, and by furnishing insufficient and unwholesome food, of large numbers of federal prisoners. (10)

On the 10th of November 1865 Henry Wirz faced his sentence– death by hanging. The event was widely covered by the media. Newspapers like the Washington-based Evening Star devoted a copious amount of coverage to the execution. Their coverage followed the event in minute detail, even publishing copies of Wirz’s last letters. (11)

Adjusting the rope for the execution of Wirz (Library of Congress)

Edward Wellington Boate was scathing in his criticism of the Union authorities. He believed that the Naval blockade and the refusal to exchange prisoners were the two main contributory factors that led to the poor conditions in Andersonville. To a prisoner in the camp these issues may have appeared simply remedied; offer a wholesale prisoner exchange and make medical supplies exempt from the naval blockade. However, in the interest of balance it is worth noting that prisoner exchange had operated earlier in the war. In the early days of the conflict exchanges happened on an ad hoc basis between opposing commanders. In 1862 the Dix- Hill Cartel (named after the two opposing generals who signed it) agreement came into effect. This went into great detail in relation to the workings of any exchange. The Cartel offered a scale of equivalencies, such as a captain is worth 15 privates etc. The deal also agreed two locations for exchange. By June 1863 the Cartel agreement had all but collapsed. Mutual distrust in addition to the refusal of the confederacy to recognise escaped slaves as prisoners of war and the disparity in numbers (the Union held nearly twice as many prisoners as the Confederacy) were all items of contention. However exchanges did occur sporadically throughout the duration of the conflict.

The other key issue that Boate blamed on the Union was the lack of medical supplies getting through the blockade. The naval blockade only existed on paper at the start of the conflict, but the Union rapidly expanded their navy and soon had effectively sealed Confederate access to imports. Allowing blockade runners through with medical supplies would be difficult to police. Would the blockade runners allow their boats be boarded for inspection? In addition, how would the authorities guarantee that the medicine would ever reach the camps and not end up in the parlours of the wealthy in Richmond?

A soldier springs the trapdoor, with men looking on from the trees beyond (Library of Congress)