Damian Shiels's Blog, page 33

January 11, 2016

Paddy Bawn Brosnan & the American Civil War: The Famed Gaelic Footballer’s Links to Kerry’s Greatest Conflict

On 14th September 1947, New York witnessed a unique sporting occasion. In front of more than 130,000 people at the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, the Gaelic footballers of Kerry and Cavan did battle in what remains the only All-Ireland Football Championship Final ever to be held outside of Ireland. Among the men who donned the green and gold of Kerry that day was Paddy Bawn Brosnan of Dingle. Even in the annals of Ireland’s most famed footballing county, Paddy Bawn Brosnan remains special. Paddy had captained Kerry in 1944 when they lost the All-Ireland to Roscommon, and had taken home winner’s medals in 1940, 1941 and 1946. The New York match of 1947 was aimed at bringing this major event to the huge Irish-American community in the United States, 100 years after the Famine which had led so many to emigrate. But Paddy Bawn Brosnan had a special connection to New York and America. Indeed, had it not been for events that had taken place in a Prisoner of War camp in Georgia more than 80 years previously, it is unlikely that he would have ever had an opportunity to pull on the Kingdom’s colours.

Footage of Cavan v Kerry from the Polo Grounds, Manhattan in 1947. You can access an RTE Radio 1 documentary on the background to the historic game by clicking here.

Over recent years I have given many lectures around the country highlighting the extent of Irish involvement in the American Civil War. Many take the form of county-focused talks, using specific local individuals to illustrate just how major an event this was in Irish history. Interestingly, it is common for at least one attendee to have a known link to an ancestor who served in the Civil War– indicative both of the impact this conflict had on Irish people, and of the fact that not all 19th century emigration was permanent. Last July I gave just such a talk to Dingle Historical Society in Co. Kerry, and was fortunate to be contacted by local man Mossy Donegan. Mossy not only knew his own connections to the conflict, but through extensive research had obtained copies of many of the historical files associated with those links. It is a familial story he shares with Paddy Bawn Brosnan, and it is as a result of Mossy’s endeavours that it can be related here.

What then was Paddy Bawn Brosnan’s connection to the American Civil War? It is a narrative that directly involves his Grandmother, but can be traced back even further, to the marriage of Paddy Bawn’s Great-Grandparents (and Mossy’s Great-Great-Grandparents) Daniel Dowd and Mary Murphy. A few years shy of a century before Paddy Bawn took the field at the Polo Grounds, Father Eugene O’Sullivan married Daniel and Mary in Dingle Roman Catholic Church on 29th October 1853, A year later, on 8th October 1854, they celebrated the birth of their first child, Edward. At some point shortly after that, the Dowds decided their future lay across the Atlantic, and became just three of the more than 54,000 people who emigrated from Kerry between 1851 and 1860. (1)

Denny Lyne, Paddy Bawn Brosnan, J J Nerney and Eddie Boland in action during the 1946 All Ireland Final between Kerry and Roscommon (The Kerryman)

Denny Lyne, Paddy Bawn Brosnan, J J Nerney and Eddie Boland in action during the 1946 All Ireland Final between Kerry and Roscommon (The Kerryman)

The favoured destination for Irish emigrants was New York, and that is where the young Dowd family arrived in the mid-1850s. A second child– a daughter Bridget– was born there about 1856. Bridget, or Biddy as she became known, came into the world on Long Island, and was Paddy Bawn Brosnan’s grandmother. If the Dowd family story had followed that of the majority of Irish immigrants to the United States in this period, Biddy Dowd would never have seen Ireland again, and Paddy Bawn Brosnan would never have been born. But seismic events intervened. By the 1860s the family had settled in Buffalo, where Daniel made the decision that changed all their lives forever, when on 6th September 1862 he enlisted in the Union army. (2)

In 1862 Daniel Dowd became one of the c. 200,000 Irish-born men who would serve during the American Civil War. He was joined in the ranks by thousands of Kerrymen; there is little doubt that it was this conflict that saw more Kerrymen fight, and more Kerrymen die, than any other war in history. The Dingle native had decided not to join just any unit. Instead he enlisted in the 155th New York Infantry, one of the regiments that would form part of Corcoran’s Irish Legion. Its leader Brigadier-General Michael Corcoran from Carrowkeel, Co. Sligo was a noted Fenian, and many supporters of the cause of Ireland specifically chose to join his brigade. Whether Daniel was one of them, or simply wanted to serve close to his fellow Irishmen, remains unknown. (3)

Soldiers of the 170th New York Infantry, one of the other regiments of Corcoran’s Irish Legion, during the Civil War (Library of Congress)

Daniel was mustered in as a private in Company I of the 155th New York at Newport News, Virginia on 19th November 1862. He was recorded as a 29 year old laborer who was 5 feet 5 inches in height, with a fair complexion, gray eyes and light hair. His surname was one that caused considerable confusion for recorders at the time. Sometimes recorded as Doud or Doody, Daniel was placed on the regimental roster as ‘Daniel Dout.’ It wasn’t long before he got his first taste of action in the Civil War, as in January his regiment was engaged the Battle of Deserted House, Virginia. Though only a mere skirmish in comparison to what the Legion would endure in 1864, it nonetheless must have had quite an impact on Daniel and the men of the 155th. (4)

Private Daniel Dowd spent the next year in Virginia with his unit. On 17th December 1863 he found himself guarding a railroad bridge, part of a detachment of some 50 men of the Legion that were protecting the Orange & Alexandria line at Sangster’s Station. At a little after 6pm that evening they were set upon by a body of Confederate cavalry, who threatened to overrun them as they sought to burn the bridge. The Rebels attacked on a number of occasions, eventually getting around the flanks and rear of the Irishmen, succeeding in setting fire to their tents and forcing them into a retreat. Cut off, the detachment would normally have looked to their telegraph operator to call for reinforcements, but he was apparently so drunk he was unable to use his equipment. General Corcoran and the remainder of the Legion only learned of the attack around 8.30pm, when a local Unionist came to inform them of events. The relief force eventually re-established a connection with the detachment, but although the bridge was saved, a number of men had been captured. Among them was Dingle-native Daniel Dowd. (5)

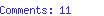

We have scant details of Daniel’s life as a prisoner-of-war, but initially he was likely held near Richmond. At some point in the spring or early summer of 1864 he was moved to the recently opened– and soon to be notorious– Camp Sumter, Georgia. Better known as Andersonville, between February 1864 and the close of the war almost 13,000 prisoners lost their lives in the unsheltered compound. Disease, much of it caused by malnutrition, was rife. On 3rd July 1864 Daniel was admitted to the camp hospital suffering from Chronic Diarrhoea. He must have been in an extremely severe state at the time, as he did not live through the day. Following the conflict his grave was identified, and today forms part of Andersonville National Cemetery, where he rests in Grave 2809. (6)

Andersonville as it appeared on 17th August 1864, a little over a month after Daniel died (Library of Congress)

Shorn of her main support, the now widowed Mary decided to leave America behind and retrace her steps to Dingle, presumably to be close to family who could provide assistance. She returned to her home town with Edward and Biddy in tow; Edward must have had little or no-memory of Kerry, while Biddy was experiencing Ireland for the very first time. In 1869 Mary, now 45-years-old, went in search of a U.S. widow’s pension based on Daniel’s service to help support the children. Now living on the Strand, Dingle, she compiled information about her marriage and her children’s birth to send to Washington D.C. as part of her application. Unfortunately, the variant spellings of her husband’s name came back to haunt her. In the marriage record, Daniel’s surname had been written as ‘Doody’, sufficiently different from the ‘Dout’ recorded on the regimental roster to raise suspicions that this was not the same man. To compound matters there was also no available documentation relating to Biddy’s birth. Although the Commissioner of Emigration had written to every Catholic parish in Long Island in order to locate it, he met with no success. The combination of these two issues, together with the difficulty in dealing with the Washington authorities at such a remove, meant that Mary’s pension wasn’t granted. Her failure to provide the additional evidence requested meant that her claim was classified as ‘abandoned.’ Mary never fully gave up fully on the process; the last entry in her file is a letter she had written in the 1890s. Addressed from Waterside, Dingle on 4th July 1892, it was sent to the Secretary of the Claim Agent Office at the White House in Washington D.C.:

Sir,

I beg to state that I Mary Dowd now living here and aged about 65 am the widow of Daniel Dowd who served as a soldier in the late American war of 1863, and died a Prisoner of War in Richmond Prison Virginia [actually in Andersonville, Georgia]. Said Daniel Dowd served in the Army of the North. After his death, I deposited the necessary documents to prove my title to pension, in the hands of a Mr. Daniel McGillycuddy Solicitor Tralee, with the view to place them before the authorities in Washington , and he on 27th December 1873, forwarded the same to a Mr. Walsh a Claim Agent, for the purpose of lodging same. Since, I have not received a reply to my solicitor’s letters or received any pay nor pension or acknowledgement of claim.

I also learn that my husband at his death had in his possession £100, which he left to Father Mc Coiney who prepared him for death, in trust for me, and which sum never reached me.

I know no other course better, than apply to you, resting assured that you will cause my just claim to be sifted out, when justice will be measured to a poor Irish widow who is now working hard to maintain a long family. (7)

Daniel and Mary’s American born daughter Biddy in later life in Dingle (Mossy Donegan)

As was common at the time, Mary was illiterate– the letter was written for her by her solicitor McGillycuddy, and she made her mark with an ‘X’. It seems unlikely she ever received any monies as a result of it. Her American-born daughter Biddy grew to adulthood in Ireland. Her home had become Dingle, Co. Kerry rather than Buffalo, New York entirely as a result of her father’s death in a Prisoner of War camp more than 6,000 km from Ireland. Daniel’s fateful Civil War service also meant his daughter married and started a family in Ireland rather than America. Biddy’s husband was a fisherman, Patrick Johnson, and together the couple had seven children. One of them, Ellie, was Paddy Bawn Brosnan’s mother. Biddy died in 1945 and is buried in St. James’s Church in Dingle. Unlike her father’s resting place in Andersonville, it is not marked with a headstone. (8)

The American Civil War had a long-lasting, inter-generational impact on tens of thousands of Irish people, both in Ireland and the United States. Had it not been for the Confederate decision to launch an attack at Sangster’s Station in Virginia in 1863, or Daniel’s incarceration in Georgia in 1864, it is unlikely that Paddy Bawn Brosnan would ever have been born. The story of the footballing legend’s family is evidence of the often unrecognised impact of what was the largest conflict in Kerry people’s history. One wonders did Paddy Bawn reflect on his own grandmother’s New York story as he made his own journey across the Atlantic to take part in that historic sporting occasion only two years after her death in 1947.

Another image of Biddy, taken with some of the younger generations of her family. Without the events of the American Civil War, she would likely have never returned to Dingle, and Paddy Bawn Brosnan would never have been born (Mossy Donegan)

*This post would not have been possible without the extensive research of Mossy Donegan. Mossy not only ordered his Great-Great-Grandmother’s unsuccessful pension application from Washington D.C. but also obtained Daniel’s service record. All the family history relating to the Brosnans in Dingle and Paddy Bawn’s connection to Biddy was provided by Mossy, and I am grateful to him for sharing their story with us.

**Thanks to Donal Nolan and The Kerryman for permission to use the image of the 1946 Final, which originally appeared on the Terrace Talk website here. Also thanks to Kay Caball for Donal’s contact details.

(1) Daniel Dowd Widow’s Pension Application, Miller 1988: 570; (2) Daniel Dowd Service Record; (3) Daniel Dowd Service Record, 155th New York Roster; (4) Ibid., New York Civil War Muster Roll; (5) Official Records: 982-984, Daniel Dowd Widow’s Pension Application, Daniel Dowd Service Record, U.S. Register of Deaths of Volunteers, Records of Federal POWs Confined at Andersonville; (7) Daniel Dowd Widow’s Pension Application; (8) Daniel Dowd Widow’s Pension Application;

References & Further Reading

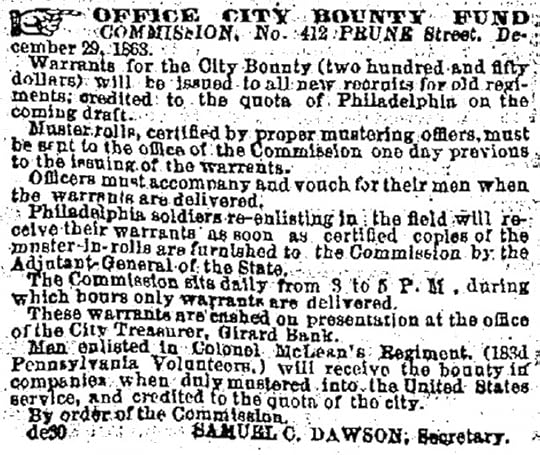

Daniel Dowd Widow’s Pension Application 180,808.

Daniel Dowd Service Record.

Roster of the 155th New York Infantry.

Daniel Dowd Find A Grave Entry.

New York State Archives, Cultural Education Center, Albany, New York; New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900; Archive Collection #: 13775-83; Box #: 607; Roll #: 263 [Original scan, accessed via ancestry.com].

Selected Records of the War Department Commissary General of Prisoners Relating to Federal Prisoners of War Confined at Andersonville, GA, 1864-65; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1303, 6 rolls); Records of the Commissary General of Prisoners, Record Group 249; National Archives, Washington, D.C. [Original scan, accessed via ancestry.com].

Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, compiled 1861–1865. ARC ID: 656639. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917. Record Group 94. National Archives at Washington, D.C. [Original scan, accessed via ancestry.com].

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 29, Part 1. December 17, 183 – Skirmish at Sangster’s Station, Va. Reports.

Miller, Kerby A. 1988. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America.

Filed under: 155th New York, Corcoran's Irish Legion, Kerry Tagged: All Ireland Final New York, American Civil War Veterans, Andersonville POWs, Irish American Civil War, Irish in New York, Kerry in America, Paddy Bawn Brosnan, Polo Grounds

January 4, 2016

Photographs of Wounded Irishmen from the American Civil War

The sometimes captivating, sometimes horrifying images of wounded soldiers taken in Washington D.C.’s Harewood Hospital in 1865 have featured in a number of posts on this site (see Looking into the Face of a Dying Irish Soldier, One of Our Brave Men Twice Wounded: An Image of Corporal William Kelleher, 125th New York Infantry and Recruited Straight off the Boat? On the Trail of Emigrant Soldiers from the Ship Great Western). These are far from the only Irishmen to feature in this remarkable collection. I decided to take a look at another four images of New York Irishmen, to see what could be uncovered about their stories and their injuries through looking at them via a range of sources.

Surgeons and Hospital Stewards at Harewood Hospital, Washington D.C. (Library of Congress)

Thomas Barry (Berry)

Thomas was born in Ireland in 1842. He was a 22-year-old laborer when he decided to enlist, becoming a substitute for Thomas Davies. He joined up in Poughkeepsie, New York on 8th August 1864 and was described as 5 feet 8 inches in height, with blue eyes, brown hair and a dark complexion. Serving as a private in Company E of the 61st New York Volunteer Infantry, he spent his service with the Army of the Potomac outside of Petersburg, Virginia. He was shot in the left hand during the Confederate attack on Fort Stedman on 25th March 1865, a wound which caused him to be admitted to Harewood General Hospital in Washington D.C. on 1st April, where the image below was exposed. The second metacarpal bone and one of his fingers had been amputated on the field (bilateral flap) prior to his arrival. On admission into the hospital he was described as being in a good constitutional state, and was reportedly doing well when he was transferred to the U.S.A. General Hospital in Philadelphia on 8th April 1865. Thomas filed for an invalid pension dated from 13th June 1865, which was granted. I have yet to locate a further record of him.

Thomas Barry (National Museum of Health & Medicine CP 0960)

Martin Burke

Martin was from Co. Sligo and was a career-soldier, having enlisted in the 1st United States Infantry on 11th September 1858. He served with them in the Western Theater until his term of service expired on 11th September 1863. He was 27-years-old when he joined the 15th New York Heavy artillery only six days later, on 17th September. Mustering in as a Corporal in Company K, Martin was described as 5 feet 5 1/2 inches tall, with blue eyes, brown hair and a ruddy complexion. He was promoted to Sergeant on 1st December 1863. On 25th June 1864 he was wounded in front of Petersburg, necessitating the amputation of his left arm at the upper third, a surgery which was performed at Lincoln Hospital in Washington. He had been in a good constitutional state when that operation had been performed, but an infection set into his arm which spread through his chest. His stump became gangrenous and there was a considerable amount of dead tissue shedding from it. A further operation saw the complete removal of the shaft at the shoulder joint on 29th March 1865. Still not out of the woods, the bone became necrotic nine months after the amputation and several abscesses formed on the stump. Martin was admitted to Harewood General Hospital on 13th September 1865 when this image was exposed. When the photograph was taken he was still in good health, but several fistulous openings which were discharging pus remained. He was being treated with disinfectant, astringtent lotions and the liberal use of internal iron. Martin sought and received an invalid pension on 4th January 1866. He was recorded as dying on 12th April 1900.

Martin Burke (National Museum of Health & Medicine CP1099)

Timothy Deasey

Timothy was born in Cork on 13th April 1847. The 1860 U.S. Federal Census records him living with his family in Manheim, Herkimer County, New York. His 35-year-old father John was a day-laborer, his mother Mary (née Tobin) was 38. Timothy was then recorded as 12-years-old; he had an older brother Owen (14), and younger siblings Thomas (9), John (5), Michael (3) and Ellen (2). As the youngest three children had all been born in New York, it suggests the family emigrated in the early 1850s. Timothy was recorded as a 17-year-old Carder when he enlisted in Little Falls, New York on 26th July 1862– he was clearly significantly younger than this. He was described as 5 feet 5 inches in height, with grey eyes, dark brown hair and a fair complexion. The Cork youth mustered in as a private in Company H of the 121st New York Infantry. He was confirmed as being present at battles such as Winchester, Fisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek. Timothy was injured in the action at Fort Stedman, Petersburg on 25th March 1865, receiving a gunshot wound to the hand which fractured his right carpus and meta-carpus. He was admitted to Harewood General Hospital in Washington on 2nd April 1865, having first been treated at City Point, Virginia. When this image was exposed he was suffering from severe inflammation of his wounds, causing great swelling of his arm and hand which gradually subsided. His treatment was supported by a simple dressing, and by the 26th May his wound was nearly healed, though he did have to live with a permanent deformity. Timothy filed an invalid pension claim which was granted dating from 14th August 1865 and seems to have returned to live in Herkimer County, where he is recorded on the 1890 Veterans Schedule. His widow would later claim a pension based on his service after his death, until her own passing in Little Falls on 1st February 1913.

Timothy Deasey (National Museum of Health & Medicine CP1001)

John Devlin

John was a 22-years-old laborer when he enlisted in Albany on 19th September 1864. He had blue eyes, brown hair, a dark complexion and was 5 feet 6 inches in height. He became a private in Company I of the 91st New York Infantry and was admitted to Harewood General Hospital in Washington on 12th September 1865. His left thigh had been amputated in the middle-third following a shell wound. The operation had been performed on the field using Teale’s method (quadrilateral flaps) by an unknown surgeon and anesthetist. Shell fragments had also severely wounded him on the left nipple and fractured his thumb, index and middle finger of the left hand, causing them to also be amputated on the field– the thumb at the first phalanx and the middle finger at the metacarpo phalangeal articulation (by bilatoral flaps). The index finger had been considerably deformed by contraction of the muscle. When admitted John was in a very good constitutional state and his wound had entirely healed. He remarked that he had been in perfect health at the time of his wounding. He responded well to treatment, which consisted of simple dressings and a nourishing supporting diet. Shortly after this image was exposed he was to be fitted with an artificial limb and he was discharged from the service on 30th September 1865. John applied for an invalid pension on 11th October 1865 which was granted. He entered the Eastern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Veterans in Togus, Maine on 21st July 1869, and was discharged from there on 3rd January 1870. He applied for readmission on 9th December that year, but his refusal to comply with the conditions of the Board of Management meant he was discharged on 2nd April 1872. By 1890 he appears to have been living in Albany, and his widow subsequently received a pension based on his service.

John Devlin (National Museum of Health & Medicine CP1098)

References

Thomas Barry CP 0960 National Museum of Health and Medicine

Martin Burke CP 1099 National Museum of Health and Medicine

Timothy Deasey CP1001 National Museum of Health and Medicine

John Devlin CP1098 National Museum of Health and Medicine

U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938 [Ancestry, database on-line]. Original data: Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1749, 282 rolls); Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Town Clerks´ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca 1861-1865 [Ancestry, database on-line]. New York State Archives; Albany, New York; ; Collection Number: (N-Ar)13774; Box Number: 18; Roll Number: 11.

Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914 [Ancestry, database on-line]. (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, 81 rolls); Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917, Record Group 94; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

1860 United States Federal Census [Ancestry, database on-line]. Original data: 1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration.

1890 Veterans Schedules [Ancestry, database on-line]. Original data: Special Schedules of the Eleventh Census (1890) Enumerating Union Veterans and Widows of Union Veterans of the Civil War; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M123, 118 rolls); Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

New York, Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900 [Ancestry, database on-line]. Original data: Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts of New York State Volunteers, United States Sharpshooters, and United States Colored Troops [ca. 1861-1900]. (microfilm, 1185 rolls).Albany, New York: New York State Archives.

New York State Military Museum Rosters.

Filed under: Battle of Fort Stedman, Battle of Petersburg, Photography Tagged: Battle of Fort Stedman, Civil War Surgical Phoography, Harewood Hospital, Irish American Civil War, Irish in the Union Army, National Museum of Health & Medicine, Photographs of Irish Soldiers, Siege of Petersburg

December 20, 2015

Analysing 19th Century Emigration, A Case Study: Dissecting One Irishman’s Letter Home

As regular readers are aware, I have long been an advocate of the need to study the thousands of Irish-American letters contained within the Civil War Widows & Dependent Pension Files. This unique resource offers insights into 19th Century Irish emigration that do not exist anywhere else. Their value to Irish, as well as American, history reaches far beyond our understanding of the Irish experience of the conflict itself. They have much to tell us about multiple facets of Irish life, both in Ireland and America. In order to demonstrate this potential, I have broken down one Irish letter into its component parts, in an effort to highlight just how invaluable these primary sources can be for those interested in Irish emigrants.

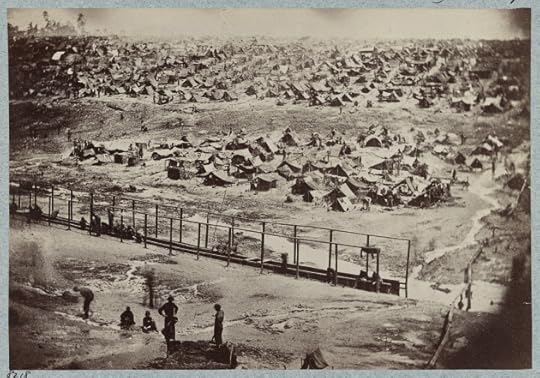

The envelope which contained Peter Finegan’s letter to his parents, which is analysed below (Fold3.com/NARA)

On 13th December 1862, 21 year-old immigrant Private Peter Finegan of the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, Irish Brigade, marched out of the town of Fredericksburg and towards Marye’s Heights. What happened to the regiment next is well documented. It was Peter’s first battle, and we are left to ponder what went through his mind as he advanced through the deadly blizzard of fire that engulfed him. It seems probable he made it past the long-range artillery fire that first gouged red trails of savagery through the Brigade’s ranks, but he was not so lucky when it came to the Rebel infantry. As the Northerners advanced, the Confederates behind the stone wall rose to pour a curtain of lead into their foe. Peter’s Captain remembering seeing the young Irishman being struck four times by bullets, inflicting wounds which ended his life. Just over 10 weeks before his death, Peter had written to his parents from his base in Fairfax Court House. In 1866, in an effort to secure a pension based on their son’s service, Peter’s mother and father included that letter in their application, where it has remained in their file ever since. (1)

Head quarters 116 Reg P. V.

Camp Bardwell, Sep 29th 1862

Dear Father & Mother

I Rec’d your kind and welcome letter about a week ago which gave me much pleasure to hear from you and I would have wrote before this only waiting for the Captain to come from the City of Philadelphia with the money so to day I send you’s $40 dollars by Adams Express Company as soon as you receive the money write to me without delay and let me know for I have the receipt for it and if you dont get it they will have it to pay when you get this letter go right away to Charles Hughes and you will get the money I’m sorry I could not send it sooner for I think by the times you were in need of it and you’s will never want while I can get any thing to help you’s along only dont be worrying yourselves about me I am all right thank God. (2)

This first element of Peter’s letter follows the general norms of what we expect from Irish letters of this period. By far the most common form sees the writer express a wish that those at home are in good health, before then stating that they themselves are well, e.g.: ‘I hope this letter finds you well as this leaves me at present thanks be to God.’ The letter immediately contains the detail which led to its inclusion in the pension application– a reference to $40 Peter was sending by Adams Express, thereby proving (as was required by the Pension Bureau) that he financially supported his parents. The Adams Express Company played a vital role for all troops at the front, and it is frequently referenced in their letters. Another common sentiment expressed in soldier’s letters is for family not to worry themselves about their welfare, and also of their determination to provide for their dependents. (3)

I was at the Holy Sacrifice of Mass this morning it was read in Camp and I think we will have mass every morning now from this out. He hears confessions every night so it gives us all a chance to go and he says he will be with us on the Battle Field so that is a great consolation to us… (4)

The letter continues with reference to Peter’s Catholic religion, which was clearly important to him and his family. Many Irish soldier’s correspondence carry references to the importance of their faith, with family often sending scapulars for the men to wear. Those Catholic Irish troops in designated Irish regiments, such as the 116th Pennsylvania, generally had significantly better access to Catholic chaplains than those that served in non-ethnic units. (5)

…so Father & Mother the only thing I as[k] of you both is not to worry about me I know I done wrong in leaving you both at the ending of your days but I hope you will forgive me and with the help of God I hope I will live to see yous in your little Home together once more and then I will take some of your advice but there is no use crying about spilt milk… (6)

Peter clearly felt guilty at leaving his parents alone in Pennsylvania. He felt this way due to a factor common among even large emigrant families– Peter was his mother and father’s main support in their old age. Particularly for those reliant on unskilled labouring, illness and infirmity posed the greatest threats to their ability to support themselves. Peter’s father, Peter Senior, had been a day-laborer, but in 1861 feebleness brought on by age (he was then in his late 60s) meant he couldn’t find work. This left Peter Senior and his wife Mary facing the very real prospect of destitution. With no property, and personal belongings valued only at $50, they needed another source of income. Today we would be surprised that this might have been the case, given that Peter Senior and Mary had six living adult children. Apart from Peter, the couple had two other sons and three daughters. Why did they not provide more assistance? The obligation fell on Peter not because his siblings were unprepared to help their parents, but because they were unable to afford it. All of them were married with families of their own; for many poorer emigrants, responsibilities to spouses and children often left nothing for ageing parents. In extreme cases older people could find themselves reliant on public charity, despite having a number of living children. Peter’s parents were spared this fate prior to 1862, as their unmarried son continued to live with them (seemingly along with their grandson), bringing in $6 a week between 1859 and 1862 by driving a wagon for a local business and using his earnings to buy food and fuel for them. (7)

…you’s can tell Miles wife that I want to know in the next letter if she lives in the same place yet for I will write to her and whoever writes letters for yous I dont want such talking about affairs as was in the other I know wright from wrong so its no use talking about it now Ive got enough to tend to although I can get anything I want from the men because I play the fiddle for them at night and we have plenty of fun Joe Benn’s son from Phila is out here in the same Regiment with me… (8)

Here Peter makes direct reference to another reality for the majority of 19th century Irish emigrants– the fact that many were illiterate. However, illiteracy did not prevent written communication. Hundreds of thousands of letters where both sender and recipient were illiterate travelled between Irish communities in the United States, and between Irish emigrants in America and those at home in Ireland. This was facilitated by the use of intermediaries who would both write letters that were dictated to them and read out letters that were received. These intermediaries were often other family members or neighbours, and in the case of soldiers literate men within the Company. One implication of this was that these 19th century letters represented a more communal experience than we associate with modern written correspondence. In the recent past (at least prior to the digital age) letter writing often carried it with it an implicit understanding of being a largely private communication between two individuals. But this only became possible when literacy reached levels which allowed the majority of people to correspond directly. For letters like that of Peter Finegan and the bulk of other 19th century Irish emigrants, we must instead imagine the letter as a more public experience, with the words being read out in front of a number of friends and family members. The degree of trust which had to be placed in the intermediary charged with writing/reading these letters was also important, particularly when they were non-family members dealing with potentially sensitive issues. In the above passage this was clearly a concern for Peter, as he asked his parents not to discuss personal affairs when he didn’t know who was writing their letters for them (it seems from the correspondence that Peter’s parents were also extremely concerned about his well-being having enlisted). (9)

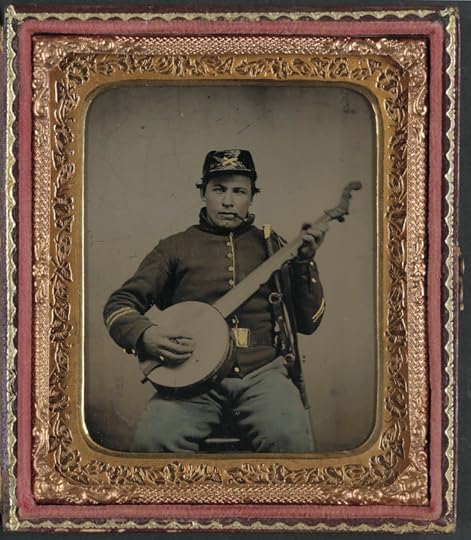

A further element in this passage refers to the popularity Peter enjoyed within the ranks due to his ability to play the fiddle, highlighting the importance of music among members of the Irish community (and indeed American society in general). Interestingly Peter also implies that his ability to play the instrument conferred on him economic benefit from those around him: ‘I can get anything I want from the men,’ demonstrating that such a skill could provide valuable supplementary benefits for those able to master it. (10)

…when you’s write to me let me know how Terence is getting along and wife and family and all the other Finegan’s as their is so many of them I have not time to mention all as I have to go on Guard at 12 O’Clock tell O’Neills to send me Johny’s directions in this letter so I can write to him let me know how Joe Sanders is getting along if he wants ditching their is plenty of it down in old Virginia to be done we are stationed at Fair Fax Court House where their was a great many hard battles fought As for William Kerns family I suppose their alone poor folks Willie Kerns wrote a letter to Tom O’Brian and he did not think worth while to mention me in it so it is the same on this side let me know how James O’Neill and wife and also the old couple and Bridget Dunleavy and family Mrs Harley and Mrs McNamara [?] and Burns family and Miles not forgetting old uncle Barney Rose Ann Mary and all…(11)

Practically all the many hundreds of letters I have read from Irish emigrants in the 1850s and 1860s conclude with a similar roll-call of requests, seeking to discover how local friends and family were faring, and often requesting that best wishes be sent to an array of individuals. Despite appearances, this was more than simply perfunctory; many letters indicate that there was an obligation to ask after certain friends and relations. This can be seen in letters which express apologies for omitting individuals from the list, and also in examples such as this from Peter, where he has clearly taken offence at not having been mentioned in a letter written by Willie Kerns to Tom O’Brian. Clearly insulted, he says ‘so it is the same on this side’ as he explicitly does not want to know how Willie is getting on. In putting this in the letter, it is apparent that Peter intends for Willie Kerns to hear that he was angered at being omitted. Such a degree of chagrin at not being included in a letter’s acknowledgements is far from uncommon in Irish emigrant letters. (12)

The passage also sees Peter refer directly to other members of his family, of which there were ‘so many’ in the community where he lived. That community was Chester County, Pennsylvania, most specifically the town of West Chester, where there were indeed ‘many’ Finnegans. Aside from Peter and his parents, the 1860 Census records his relations Terence (39), a day-laborer with his wife Catharine and their six children (Real Estate: $0, Personal Estate: $50); Patrick (30), a day-laborer with his wife Bridget and their three children (Real Estate: $800, Personal Estate: $300); Michael (29), a day laborer with his wife Alice and their three children (Real Estate: $700, Personal Estate: $50); and James (28), a merchant with his wife Mary and daughter (Real Estate: $3700, Personal Estate: $3000). In addition Peter’s uncle Barney (35) lived in nearby West Bradford, where he made his living as a farmer with his wife Catherine and their three children (Real Estate: $3000, Personal Estate: $200). Another potential relative Peter (28) lived in Phoenixville with his wife Bridget and their two children (Real Estate: $0, Personal Estate: $50). It is unfortunately not possible to identify many of the female Finnegans with certainty in the 1860 Census due to the adoption of their husband’s surnames, but many undoubtedly also lived in the area. In every single instance cited above both parents had been born in Ireland, while all the children had been born in Pennsylvania. The Finnegans represent a classic case of chain migration, which saw members of one family (or local community) emigrate to the same area over time, usually following in the footsteps of relatives who had blazed the trail, in this instance to Chester County. As can be seen from the estates that some of the Finnegans possessed in 1860– namely James, the West Chester merchant and Barney, the West Bradford farmer– a number of them had already made a success of life in America. Escaping life as a day-laborer appeared to be the key to developing an increased quality of life, as the 1850 Census records both James and Barney prior to their success, working as laborers in West Chester. (13)

So it seems likely that Peter Finnerty and his family settled in West Chester because they already had family there. But what drove them to leave? The potential answer lies in the date of their arrival in the United States. The records suggest that they are the Finnerty family which arrived in Philadelphia aboard the packet ship Saranak from Liverpool on 18th May 1847. The family do not appear to have been the only Finnertys aboard. The manifest lists 45-year-old laborer Peter Finegan, his wife ‘Mrs. Finnegan’, 16-year-old Judith, 16-year-old Matthew, 12-year-old Rose, 8-year-old Mary, 6-year-old Peter (almost certainly the author of this letter, who died at Fredericksburg), 20-year-old Patrick, 18-year-old Mary, 15-year-old Peggy and 19-year-old Michael. It is probably no coincidence that they all arrived in America at the height of the Great Irish Famine, and it is also very likely they knew they were going to West Chester before they left Ireland. The 1850 Census records Peter living with his parents in the town at that date, and most of the other Finnegans were already in place at that date. (14)

Aside from the Finnegans mentioned in Peter’s letter, the other named individuals also serve to provide us with an insight into Irish life in America. The overwhelming majority of them were Irish-born, indicating that the Irish in West Chester formed a distinct close-knit community in this period. The Willie Kerns who Peter chastised in his letter was Pennsylvania-born, but his father William (a day-laborer) and mother Mary were of Irish birth; Tom O’Brian was a Pennsylvania-born clerk, but lived and worked with Peter’s merchant relation James Finnegan; all the James O’Neills recorded in West Chester in 1860 were Irish-born; the Dunleavys were Irish-born; Mrs. Harley was the wife of Peter’s one time employer, who were Irish-born emigrants with a carpet-weaving and bottling business. Ancestry.com lists 4,757 people as having been recorded on the 1860 Census in West Chester. Slightly over 10% of them, some 480 people, were recorded as being born in Ireland, far outnumbering any other emigrant group in the town. It is likely that the addition of the American-born children of Irish emigrants to this number would at least double this overall percentage, making the Irish community of West Chester a very significant minority. (15)

…no more at present but remains your son Peter Finegan

I am the same Pete as I always was and will be till I get shot at missed [?]–

Direct your letter to Fair Fax Court House Virginia Va Washington 116 Reg P.V. Col Dennis Heenan for Peter Finegan Co. K Capt J. O’Neill Commanding

Dont forget write as soon as you get this without delay (16)

The final section of Peter’s letter again hints at the concern his parents expressed at him joining the army. He felt it necessary to reassure them that he was the same person he had always been. Perhaps his parents were not strong supporters of the war, and there is at least a suggestion that they were worried the experience of conflict might change their son. They never did have the chance to find out, as after only three and a half months the four Rebel bullets that buried themselves in Peter’s body on Marye’s Heights ended his life. Today the letter that he left behind from the war that claimed his life, along with those of thousands of other doomed Irish-Americans, offer us a unique opportunity to examine the experiences of those who left Ireland in the greatest emigrant wave ever to depart these shores.

(1) Peter Finegan Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (2) Ibid.; (3) Ibid.; (4) Ibid.; (5) Ibid.; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid., 1860 Federal Census; (8) Peter Finegan Dependent Mother’s Pension File; (9) Ibid.; (10) Ibid.; (11) Ibid.; (12) Ibid.; (13) Ibid., 1860 Federal Census, 1850 Federal Census; (14) Peter Finegan Dependent Mother’s Pension File, Philadelphia Passenger Lists, 1850 Federal Census; (15) Peter Finegan Dependent Mother’s Pension File, 1860 Federal Census; (16)Peter Finegan Dependent Mother’s Pension File;

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

Peter Finegan Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC 138689.

1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. West Chester, Chester, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1094. (Original scans accessed via Ancestry.com).

1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration.West Bradford, Chester, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1091. (Original scans accessed via Ancestry.com).

1860 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. Phoenixville, Chester, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1092. (Original scans accessed via Ancestry.com).

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C.(Original scans accessed via Ancestry.com).

The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Records of the United States Customs Service, 1745-1997; Record Group Number: 36; Series: M425; Roll: 064. (Original scans accessed via Ancestry.com).

Civil War Trust Battle of Fredericksburg Page.

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Filed under: 116th Pennsylvania, Battle of Fredericksburg, Irish Brigade Tagged: Dependent Pension Files, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Fredericksburg, Irish Emigrant Letters, Irish Emigration Primary Sources, Irish in America, Irish in Pennsylvania, Widow's Pension Files

December 10, 2015

‘Our Pickets Were Gobbled’: Assessing the Mass Capture of the 69th New York, Petersburg, 1864

On 30th October 1864 the famed 69th New York Infantry suffered one of it’s most embarrassing moments of the war, when a large number of its men were captured having barely fired a shot. In the latest post I have used a number of sources to explore this event, seeking to uncover details about those men captured– who they were, how long they had served, what became of them. In an effort to consider why this mass-capture occurred, the post also examines how veteran soldiers defined ‘old’ and ‘new’ men, and provides detail on a number of the 69th POWs who decided to take up arms for the Confederacy.

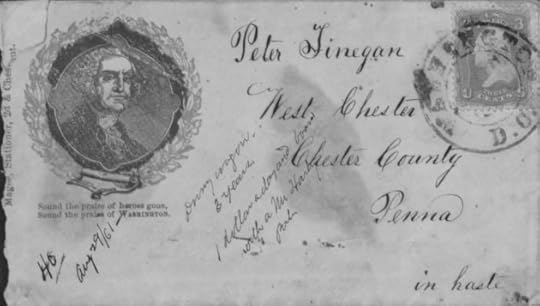

The 69th New York were positioned in this sector of the line on 30th October 1864, in front of Fort Davis. Extract from a map drawn by Brevet Colonel Michler for Jarratt’s Hotel, Petersburg.

In the widow’s and dependent pension file research I conduct into Irish soldiers in the American Civil War, one year that crops up again and again– 1864. Grant’s strategy of applying relentless pressure in both the Eastern and Western Theaters was ultimately a war-winning one for the Union, but it carried with it a staggering human cost. From an Irish perspective, I find the period of 1864-5 by far the most intriguing of the conflict. It was a year that appears (though there is a need for significant analysis in this area) to see a large number of first-time Irish soldiers enlisting to take advantage of the major economic incentives available for service. It was also a year that saw the effective destruction of many of the old ‘green flag’ ethnic units, notably those serving in the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps. Losses, combat fatigue and high troop turnover meant that few of the famed regiments and brigades from 1861 and 1862 that continued their service escaped without blots on their military record. In the East, engagements such as Ream’s Station (see here) and Second Deep Bottom were testament to the failing fighting strength of many such units. The Irish Brigade was no exception. By mid-June 1864, the Brigade, which had already received an infusion of new men before the Overland Campaign commenced, was so reduced in numbers that it was effectively broken-up, with the core New York regiments forming part of what became known as the ‘Consolidated Brigade’ of the First Division, Second Corps. It was as part of this Consolidated Brigade that the 69th New York suffered perhaps it’s greatest embarrassment of the war– the mass capture of large numbers of it’s troops while on picket duty outside Petersburg on 30th October 1864.

The events of the evening of 30th October 1864 have long held an interest for me, as they suggest the almost complete disintegration of the 69th New York as an effective front-line unit. But just what men made up the 69th New York at the time? How many were recent recruits? how many were substitutes? where were they from? In order to look into this I have analysed both the roster of the 69th New York and the New York Civil War Muster Roll extracts to build a picture of the men captured and their fate. But first it is appropriate to explore the events of the 30th October themselves, an evening when so many of the 69th fell into Rebel hands.

The 30th October found members of the Consolidated Brigade holding a portion of the line around Fort Davis and Fort Sedgwick. The previous evening, elements of the division had launched sorties against the Confederate line; a sally by the 148th Pennsylvania had been followed around 8.30pm that evening with a raid by the 88th New York, as Lieutenant Colonel Denis Burke led 130 men against the Rebel picket line in an area known as the Chimneys, opposite Fort Sedgwick. It may have been these probes that elicited the Confederate response the following evening. The next night both the 69th New York and 111th New York of the Consolidated Brigade were on picket duty. Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Husk of the 111th was in overall command of the picket detail, and reported that some of the men were talking across the lines to the Rebels, an activity which he ordered stopped immediately. Then, sometime between 7 and 8pm, the Rebels silently sent out a force of around 150-200 men to try and snare their opponents. As they crawled flat on the grass towards their target, few of them could have expected the dramatic success which their operation would achieve. (1)

Second Lieutenant Esek W. Hoff of the 111th New York was sitting by his fire at Post No. 1 of his regiment’s picket line when he heard a group of men approaching from the adjacent positions, held by the 69th New York. Presuming it to be his relief, he got his men ready to move out. Stepping aside to let the fresh troops past, Hoff noticed the men’s blue caps and light blue overcoats, but something seemed amiss; the trousers their relief were wearing were gray. Realising his mistake, Hoff dashed off to tell Lieutenant Colonel Husk that Confederates had penetrated the line and were capturing his men. Crucially, Hoff failed to alert Post No. 2 of the intruders’ identity, thereby sealing their fate, as the Rebels swept on down the line. Each picket post in succession mistook the enemy for their relief, until nearly all of the 111th New York’s picket had been ‘gobbled.’ The Confederate strategy had seen them penetrate the Yankee picket line in the 69th New York’s sector, before fanning out left and right to gather up as many prisoners as they could (for an intriguing analysis of this action, see Brett Schulte’s post at Beyond the Crater here). The unfortunate Lieutenant Hoff and the men of the 111th New York had fallen foul of one wing of this thrust– the 69th New York were faring little better against the other. (2)

As Esek Hoff was experiencing what was likely his worst day of the war nearby, Co. Wexford’s Lieutenant Murtha Murphy of the 69th New York was overseeing his portion of the picket line opposite Fort Davis. He recalled how the left of that line rested on an ‘almost impassable’ swamp, which broke his connection with the pickets beyond, while his right connected with the 63rd New York. Murphy’s pickets had orders to fire at intervals of five minutes, which they did for much of the evening, until his Sergeant caught sight of a group of men advancing towards their position from the left front. As with Lieutenant Hoff, the Sergeant assumed the men were their relief, but just to be sure he hailed them. Receiving no answer, Murphy’s men opened fire, which the Rebels answered. They could hear other pickets of the 69th running through the brush off to their left, not realising at the time that they had all been captured and were being herded to Confederate lines. As the firing continued, a sharpshooter from the 3rd Division eventually arrived, informing Murphy that all the men to his left had either been captured or had run away, leaving their muskets behind them in the trenches. When they counted the cost of the evening’s events, the scale of the disaster became clear. For negligible loss, the Confederates had captured 247 men– 82 soldiers of the 111th New York and 1 officer and 164 men of the 69th. (3)

The investigation was immediate. Hoff and other officers on the line were arrested, though ultimately no charges seem to have been brought. Colonel McDougall of the 111th New York pointed to the previous desertion of ten men of the 69th New York to the enemy while serving on this portion of the line as an indication that the Rebels had learned details of their dispositions. This was a view endorsed by Brigadier-General Miles, who thought that ‘deserters from the Sixty-ninth were rebels and informed the enemy of the position of our line.’ Intriguingly, Lieutenant Robert Milliken, commanding the 69th, included in his report a breakdown of the ‘new’ and ‘old’ soldiers of the regiment on the line that night. Of the total, he said they broke down into ‘New men (recruits recently arrived), 190; old soldiers, 40; total, 230. Old commissioned officers, 2; acting lieutenants, 3; total, 5. Of this number 1 old commissioned officer and the 3 acting lieutenants, with 141 new men and 23 old men, were captured.’ (4)

One of the questions I was keen to answer was what constituted a ‘new’ man and who were regarded as ‘old’ men. Was the distinction one of pre-1864 enlistments, or did it literally refer to those soldiers who had joined the regiment in previous days? But firstly I wanted to examine the question of deserters potentially providing information to the enemy. Analysing the unit roster for details of those who deserted the regiment during the month of October revealed 12 men, listed in Table 1 below, though give the often partial nature of these records this is almost certainly not a comprehensive list.

NAME

RANK

AGE

CO.

ENLIST.

MUSTER

SUB.

OCCUP.

NATVITY

DESERTION

NOTES

Hughes, Charles

Pte.

D

01/10/64

Peterson, Peter

Pte.

24

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Sailor

Sweden

04/10/64

Reynolds, Michael

Pte.

20

None

Jamaica

08/10/64

Sailor

England

08/10/64

In NY

Kenny, Patrick

Pte.

20

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Yes

Farmer

Ireland

10/10/64

Simmons, George

Pte.

24

C

Brooklyn

19/01/64

Sailor

New York

10/10/64

Kelly, James

Pte.

22

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Laborer

Canada

10/10/64

From camp

Dorman, Thomas

Pte.

19

H

New York City

03/09/64

20/10/64

Riley, Peter

Pte.

18

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Printer

Ireland

24/10/64

From hospital

Heffernan, John

Pte.

29

I

Tarrytown

15/09/64

Boatfitter

Ireland

26/10/64

On picket

Malloy, William

Pte.

39

I

Jamaica

08/09/64

26/10/64

On picket

Howard, George

Pte.

30

C

New York City

15/07/64

Bookkeeper

Canada

?/10/64

Clarke, Francis

Pte.

24

F

Wheatfield

21/09/64

?/10/64

From camp

Table 1. Deserters from the 69th New York in October 1864, Ordered by Date of Desertion. Details drawn from 69th New York Roster & New York Muster Roll Extracts. Co. = Company, Enlist. = Enlistment, Sub. = Confirmed Substitute, Occup. = Occupation.

As can be seen from their desertion dates and locations, the majority of these deserters could not have informed the Rebels about the picket dispositions, but two of them could: John Heffernan and William Malloy. Both of these soldiers deserted while on picket duty with Company I on the 26th October, and both had been in the regiment only a matter of days. None of these October deserters were pre-1864 enlistees, and at least five of them had served less than two months. These men were taking a terrible risk by trying to escape service. Only a month previously, on 26th September, 36-year-old Canadian-born farmer John Nichols had deserted from Company A, only four days after mustering in. A substitute, he was shown no mercy– on the 10th March 1865 was executed by hanging. (5)

NAME

RANK

AGE

CO.

ENLISTMENT

MUSTER

SUB.

OCCUPATION

NATIVITY

FATE

Abbott, James H.

Pte

19

H

Plattsburgh

25/08/64

Yes

Farmer

New York

Acorn, Jr., John

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Farmer

New York

Died POW Salisbury

Arnold, Martin

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Colier

New York

Bauer, Andrew

Pte

22

H

Brooklyn

03/09/64

Blenin, John

Pte

H

03/09/64

Died POW Florence

Bowers, George

Pte

H

Schenectady

03/09/64

Brearton, John

Pte

29

F

Tompkinsville

20/09/64

Boatman

Ireland

Burns, Dennis

Pte

22

I

Schenectady

23/09/64

Laborer

Ireland

Enlisted with Confederates

Callahan, James

Pte

30

H

Brooklyn

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Cleary, John

Pte

20

F

Jamaica

27/09/64

Laborer

Ireland

Cole, Franklin

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Farmer

New York

Died POW Salisbury

Connelly, John

Pte

32

C

Jamaica

23/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Costello, Thomas

Pte

27

I

New York City

07/09/64

Mason

Ireland

Cox, Henry

Pte

19

F

New York City

27/09/64

Cooper

Barbados

Cross, Francis

Pte

27

H

Troy

03/09/64

Moulder

Canada

Confederate Oath of Allegiance

Darling, William

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

New York

Died POW Salisbury

Denick, John

Pte

24

H

New York City

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Germany

Diedly, Johan A.

Pte

20

H

Tarrytown

03/09/64

Yes

Cabinet Maker

Germany

Eck, Michael J.

Pte

25

H

Troy

03/09/64

Yes

Farmer

Germany

Fogg, Jacob

Pte

23

H

Troy

03/09/64

Yes

Germany

Freeman, John

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

New York

Fusia, Frederick

Pte

27

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

New York

Groppe, Francis

Pte

34

I

Tompkinsville

17/09/64

Farmer

Germany

Healy, William

Pte

19

I

Tompkinsville

06/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Canada

Holt, William

Pte

25

E

Tarrytown

03/09/64

Yes

Sailor

Germany

Howard, John H.

Pte

29

K

New York City

20/09/64

Yes

Laborer

England

Jordon, Charles M.

Cpl

34

H

Troy

03/09/64

Kearney, Patrick

Pte

32

I

New York City

14/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Kearnes, John

Pte

20

C

New York City

20/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Kennedy, Patrick

Pte

23

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Furnace Man

Ireland

Kundegg, Heinrich

Pte

20

H

Harts Island

03/09/64

Lawrence, Charles

Pte

18

E

Troy

03/09/64

Yes

Butcher

New York

Lindner, John G.

Pte

43

I

Tompkinsville

16/09/64

Cap Maker

Germany

Died POW Salisbury

Long, Joseph

Pte

38

C

New York City

27/09/64

Yes

Teamster

Canada

Died POW Salisbury

Lynch, Thomas J.

Cpl

26

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Canada

Marsh, William

Pte

38

H

Schenectady

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Virginia

McCawley, Owen

Pte

39

K

New York City

19/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

McGilvery, William

Pte

35

I

Tompkinsville

13/09/64

Seaman

Canada

Moran, James

Cpl

21

H

Tarrytown

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Murphy, Thomas

Pte

31

I

Jamaica

02/09/64

Laborer

Ireland

Died POW Salisbury

Muzzy, Daniel

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Farmer

New York

O’Brien, Bernard

Pte

26

K

New York City

20/09/64

Yes

Watch-Maker

Ireland

O’Brien, Jeremiah

Pte

37

K

Jamaica

19/09/64

Carpenter

Ireland

Penslow, Robert

Pte

18

I

New York City

06/09/64

Bartender

New York

Perry, Robert

Pte

25

C

Tarrytown

23/09/64

Enlisted with Confederates

Read, George

Pte

24

I

Tompkinsville

17/09/64

Cigar Maker

Germany

Enlisted with Confederates

Renzie, Michael

Cpl

18

H

Schenectady

03/09/64

Robinson, John

Pte

21

I

Schenectady

02/09/64

Laborer

Ireland

Roche, James

Pte

38

C

Jamaica

22/09/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Scott, John

Cpl

35

H

Troy

03/09/64

Yes

Gardener

Scotland

Shannon, John

Pte

26

K

New York City

20/09/64

Boilermaker

Ireland

Sickles, John H.

Pte

18

H

Kingston

03/09/64

Smith, Clinton G.

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Laborer

New York

Died POW Salisbury

Smith, Levi

Pte

35

I

Jamaica

13/09/64

Farmer

New Hamps.

Enlisted with Confederates

Taylor, Adny

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Farmer

New York

Taylor, Levi

Pte

18

H

Plattsburgh

03/09/64

Yes

Farmer

New York

Tembrockhaus, Gerhard

Pte

21

H

New York City

03/09/64

Died POW Salisbury

Van Guilder, Longer

Pte

18

H

Troy

03/09/64

Wesler, Andrew

Pte

28

I

New York City

14/09/64

Yes

Coalman

France

Enlisted with Confederates

White, Robert

Pte

22

C

Jamaica

20/09/64

Plumber

Ireland

Williams, Richard

Pte

20

I

Tompkinsville

12/09/64

Laborer

Ireland

Enlisted with Confederates

Bartst, Jacob

Pte

20

C

Jamaica

10/10/64

Cigar Maker

Germany

Braddock, Thomas

Pte

19

K

Brooklyn

10/10/64

Machinist

England

Denny, Patrick

Pte

21

K

New York City

13/10/64

No detail

Gannon, Thomas

Pte

38

C

New York City

13/10/64

Tailor

Ireland

Died POW Salisbury

Haire, Frank

Pte

23

K

Jamaica

13/10/64

Carriage Maker

Ireland

Died Disease After Release

Johnston, John R.

Pte

19

C

New York City

12/10/64

Sailor

New York

McCabe, Patrick

Pte

19

K

New York City

11/10/64

Clerk

Ireland

Morrison, Edward

Pte

28

C

Jamaica

13/10/64

Tailor

Ireland

Murray, Edward L.

Pte

22

G

Jamaica

03/10/64

Student

New York

Died POW Salisbury

Murray, Patrick

Pte

22

C

Jamaica

11/10/64

Laborer

Ireland

O’Callaghan, Edward

Pte

22

K

Tarrytown

14/10/64

Shoemaker

Ireland

Died POW Salisbury

O’Day, Patrick

Pte

24

C

Kingston

07/10/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Redfield, Charles

Pte

38

C

Tarrytown

11/10/64

Soldier

Germany

Reilley, John J.

Cpl

30

C

New York City

07/10/64

Wheelwright

New York

Smith, Michael

Pte

20

K

New York City

11/10/64

Laborer

Canada

Stanton, William

Pte

29

C

Tarrytown

13/10/64

Butcher

Ireland

Died Disease After Release

Cranney, John

Pte

37

F

New York City

11/11/62

Shoemaker

Ireland

Vaugh, Jacob

Pte

H

Vendry, George

Pte

H

Brady, Charles

Pte

30

K

New York City

23/05/64

Tailor

Ireland

Died POW Salisbury

Clampett, Patrick

Pte

19

K

New York City

29/03/64

Druggist

Ireland

Enlisted Steward, U.S. Army

Greever, Anthony

Pte

25

K

Brooklyn

19/03/64

Hughes, Michael

Pte

23

G

New York City

19/03/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Johnston, Robert

Pte

27

K

New York City

29/03/64

Kane, Eugene

Pte

19

C

New York City

07/03/64

Clerk

Ireland

Leahy, William

Pte

20

K

New York City

10/03/64

Ireland

KIA 25 March 1865, Petersburg

Richmond, Peter

Pte

19

C

New York City

12/03/64

Died POW Salisbury

Slattery, John

Pte

38

K

New York City

31/03/64

Laborer

Ireland

Died POW Salisbury

Traynor, Patrick

Sgt

27

K

New York City

19/03/64

Laborer

Ireland

Quinn, Michael

Cpl

19

C

Brooklyn

01/06/64

Died POW Salisbury

Decker, Andrew

Pte

25

C

New York City

20/07/64

Yes

Farmer

Germany

Irwin, Richard

Cpl

36

C

New York City

22/07/64

Yes

Druggist

Ireland

Enlisted with Confederates

Koteba, Joseph

Pte

19

C

New York City

15/07/64

McConnell, Joseph

Pte

28

B

New York City

20/07/64

Bamford, Samuel

Pte

21

C

Brooklyn

20/01/64

Barton, Lewis

Pte

18

G

New York City

21/01/64

Gunsmith

New York

Bower, Henry

Pte

18

G

New York City

22/01/64

Laborer

Germany

Bushay, Thomas

Pte

20

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Sailor

England

Farmer, Robert

Cpl

22

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Carpenter

Ireland

Died POW Salisbury

Harney, Matthew

Pte

33

G

New York City

27/01/64

Tailor

Ireland

McMahon, John

Pte

22

G

New York City

18/01/64

Died Disease After Release

Miller, Henry

Pte

19

G

Brooklyn

21/01/64

Laborer

New York

Murphy, Daniel

Pte

19

G

New York City

28/01/64

Scotland

Roe, Allan

Pte

23

C

Brooklyn

28/01/64

Sailor

England

Furnished a Substitute

Schuitzen, Joseph

Pte

25

G

New York City

19/01/64

Butcher

New York

Hutchinson, Elijah

Pte

19

G

New York City

01/02/64

Painter

New York

Died POW Salisbury

Tucker, William

Cpl

19

G

New York City

12/02/64

Iron Moulder

Ireland

McGrath, Thomas

Sgt

20

C

New York City

27/12/61

Baker

Ireland

Mustered 1st Lieutenant

Reilly, John

Pte

19

F

New York City

20/12/61

Archabald, William J.

Pte

19

F

Avon

31/08/64

Brennen, William

Pte

21

G

New York City

18/08/64

Painter

New York

Devin, Alexander

Pte

27

G

Poughkeepsie

17/08/64

Laborer

Ireland

Digan, Bernard

Pte

38

G

New York City

19/08/64

Yes

Laborer

Ireland

Garrett, Sidney

Pte

19

D

Malone

24/08/64

Morrow, Jacob

Pte

H

Schenectady

30/08/64

Quigley, James B.

Pte

22

I

New York City

27/08/64

Laborer

Ireland

Renuer, Antoine

Pte

27

E

Troy

27/08/64

Laborer

Austria

White, William E.

Pte

28

G

New York City

08/08/64

Yes

Carpenter

England

Patchern, George

2nd Lt

26

E

New York City

12/08/62

Clerk

New York

Table 2. Members of the 69th New York captured on picket at Petersburg, 30th October 1864.Details drawn from 69th New York Roster & New York Muster Roll Extracts. Co. = Company, Sub. = Confirmed Substitute.

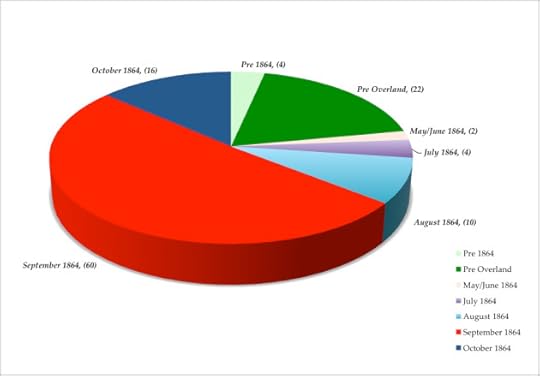

What then of the men who were captured on 30th October? I was able to identify 120 of them, and their details are available in Table 2 above. What is immediately apparent is that Milliken’s term ‘new men’ referred to those who had just arrived. If a soldier had been in the ranks since the start of the Overland Campaign, he was deemed an ‘old soldier.’ As we can see in Chart 1, only four of the men I identified as captured were pre-1864 enlistees, with a further 22 having joined up prior to the commencement of the Overland Campaign. The vast bulk (including all bar one of the soldiers clearly identifiable as substitutes) had mustered in during the campaign. 86 of the soldiers had only been with the regiment since August– 60 of them having entered the regiment in September. They were undoubtedly on the whole brand new men, with limited training and experience. A total of 39 of the men were confirmed substitutes, and again the vast majority– 32– had arrived in September. Another substitute had arrived in October, but only one of the substitutes identified had come prior to July. (6)

Chart 1. 69th New York Soldiers Captured on 30th October 1864 by Muster Date (click to enlarge).

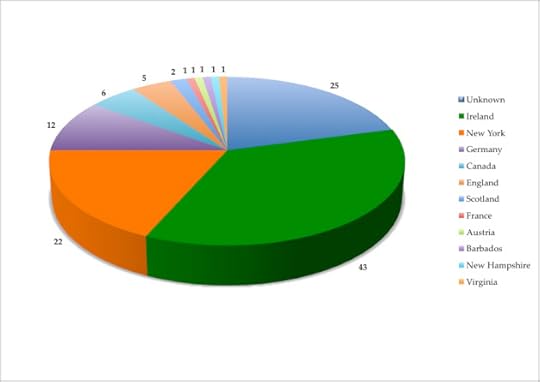

Among the other interesting details to emerge were the professions of the men. Unsurprisingly laborers dominated (33), followed by farmers (10). Those captured were largely young, with 34 being teenagers and a further 73 under the age of 25. Only 24 of the men were identified as over 30 years-of-age. Chart 2 below illustrates the nativity of the soldiers. Despite the influx of new recruits, it is interesting to observe that Irish nativity still accounted for the majority of 1864 enlistees; the number known to be born in Ireland (43) is almost double the number of men identified as being born in New York (22). For 25 of the men no nativity was recorded, and there were 12 Germans, 6 Canadians and 5 English among the number. (7)

Chart 2. Nativity of 69th New York Soldiers Captured at Petersburg on 30th October 1864 (click to enlarge)

What became of these men once they had been captured on that fateful night? 18 of them were reported has having died as Prisoners of War, the vast bulk in Salisbury, North Carolina. It is likely that some of the other men whose fate went unrecorded met a similar end. A further three men succumbed to disease shortly after their exchange. One returned to the 69th only to be killed in action on 25th March 1865. At least eight of the men sought to escape the horrors of prison life by making a bargain with the Confederates. One of the men was recorded as taking an Oath of Allegiance to the Confederacy (he was subsequently pardoned) while seven more enlisted in the Confederate army. Of these eight men, one was a July enlistee in the 69th but all the others had mustered in during September. I examined the Confederate Service Records for details of where these Galvanized Rebels served (see below). They all joined either the 1st or 2nd Battalions of the ‘Foreign Legion Infantry’, units specifically formed from among Federal prisoners and which supposedly targeted emigrant Yankees.

8th Battalion Confederate Infantry (2nd Foreign Legion Infantry)

Robert Perry, Company D, enlisted on 10th December 1864 at Florence

George Reed, Company B, enlisted on 10th December 1864 at Florence

Andrew Wesler, Company B, enlisted on 10th December 1864 at Florence, recaptured by General Stoneman and released in Nashville on 6th July 1865

Richard Irwin, Company F, enlisted on 13th December 1864 at Salisbury

Tucker’s Regiment Confederate Infantry (1st Foreign Legion Infantry)

Lewis (Levi) Smith, Company I, enlisted on 1st December 1864 at Salisbury

Richard Williams, Company E, enlisted on 7th November 1864 at Salisbury

I could find no record of Francis Cross’s service in the Confederate military (8)

The events of the 30th October 1864 were a major embarrassment to the 69th New York. Analysis of the records of the men captured demonstrates just how much the 69th had been impacted by 1864. As we have seen before on the site (for example here) many 1864 recruits who had joined the Irish Brigade before the Overland Campaign developed their own esprit de corps, and clearly by the autumn of 1864 they were considered old soldiers by many of the volunteers of 1861 and 1862 as well. The huge influx of recruits in September had transformed the regiment, and indeed in many respects it bore no resemblance to the formation that had taken the field in The Wilderness the previous May. But two days after the debacle of 30th October there was better news for the men of the old Brigade. On 1st November 1864, after much effort, Colonel Robert Nugent took command of a newly reconstituted Irish Brigade. He told the troops that ‘In assuming command of the old Irish Brigade, it gives me much satisfaction to know that, although fearfully decimated by the casualties of a campaign, in which its officers and soldiers endured, with a cheerfulness unsurpassed, unusual dangers, hardships, and privations, they still maintain their old reputation for bravery and patriotism. The record of the brigade has been a bright one; it has proved its fidelity to the Union by its courage and sacrifices on many a battle-field. Never has a regimental color of the organization graced the halls of its enemies. Let the spirit that animates the officers and men of the present be that which will shall strive to emulate the deeds of the old brigade.’ (9)

(1) Official Records: 254, Official Records: 258-9, Official Records: 255-6; (2) Official Records: 255-6, 257-8; (3) Official Records: 256, Official Records: 255, Official Records: 257; (4) Official Records: 255, Official Records: 257; (5) 69th New York Roster, New York Muster Roll Extracts; (6) Ibid.; (7) Ibid.; (8) Confederate Service Records; (9) Official Records: 476-7;

References & Further Reading

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Headquarters First Division, Second Army Corps, October 30, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Headquarters First Division, Second Army Corps, November 2, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Hdqrs. Third Brigade, First Division, Second Corps, November 1, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Hdqrs. Third Brigade, First Division, Second Corps, Before Petersburg, November 1, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Headquarters Sixty-Ninth New York Volunteers, October 31, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Camp of the Sixty-Ninth Regt. New York Vet. Vols., October 31, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 1. Headquarters 111th New York Volunteers, October 31, 1864.

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 42, Part 3. General Orders, No. 1. Hdqrs. 2d Brig., 1st Div., 2d A.

Confederate Service Records.

Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts of New York State Volunteers, United States Sharpshooters, and United States Colored Troops [ca. 1861-1900]. (microfilm, 1185 rolls).Albany, New York: New York State Archives. Ancestry.com. New York, Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900 [database on-line].

New York Adjutant General 1901. Roster of the 69th New York Infantry.

Civil War Trust Battle of Petersburg Page.

Petersburg National Battlefield.

The Siege of Petersburg Online.

Filed under: 69th New York, Battle of Petersburg, Irish Brigade, Resources Tagged: 69th New York, Civil War Pickets, Galvanized Rebels, Irish American Civil War, Irish Brigade Petersburg, Irish Desertion, Irish Substitutes, Salisbury POW

December 6, 2015

‘Slavery, At Last, Is At An End’: Reporting on the Ratification of the 13th Amendment in Ireland