Damian Shiels's Blog, page 32

March 5, 2016

‘We Have No Interest…in the Claim”: A Cork City Affidavit After A Death at Malvern Hill

The majority of posts on the site relate to information contained within the Widows and Dependents Pension Files. These files can contain dozens of different types of documents, ranging from military records to soldier’s letters. But the bulk of the social data is contained within the affidavits of family, friends, employers and others, which were submitted to prove certain aspects of the applicants claim, such as their dependency on a the soldier. In order to tell the story of a particular file in a coherent fashion, my normal process is to read all the documents contained within it, extracting the detail necessary to present the information in narrative form. I have never reproduced the complete text of one of these affidavits, but recently came across one given in Cork City, Ireland, which I believe stands on its own merit. It may interest readers to see how these affidavits can appear in their full form.

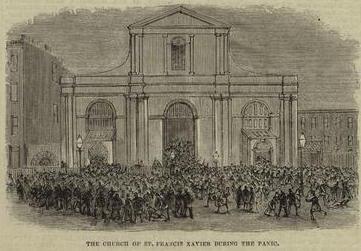

Officers and men of the 9th Massachusetts (Library of Congress)

The affidavit was provided before a magistrate in Cork, Ireland by David Kelly, a labourer, and David Crowley, a land steward. They gave their statements in early 1866 and the resulting document was duly signed off by the U.S. Consul in Queenstown (now Cobh), Edwin G. Eastman, before being sent to the United States. The two men were giving their accounts in support of 63-year-old Hanorah Mulcahy, a resident of Cork City, who was seeking a dependent mother’s pension. The affidavit is somewhat atypical in that it provides such a range of detail regarding Hanorah’s children, and is also unusually long. However it retains a narrative form all its own, providing insights into the impact of emigration on this elderly Cork woman and detail on the life of her son both before and after his departure. Her boy was David Mulcahy, who had supported his mother and ill sister in Cork by working at Guy Brothers Printers on Patrick Street, the city’s main thoroughfare. He appears to have emigrated around 1858/9, after which he had become a currier, joining thousands of other Irish emigrants in Massachusetts who worked in the leather industry. He was recorded as 22-years-old when he enlisted in the Union Army from South Danvers, Massachusetts on 11th June 1861. Two days later he mustered in as a private to Company I, 9th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, an ethnic Irish regiment. David was wounded in action at the Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia on 1st July 1861, dying of his injuries almost two weeks later while on a transport boat at Harrison’s Landing (the date of his death is variously recorded as the 11th, 13th or 14th July). Hanorah’s pension application was eventually granted, though it was not approved until 18th January 1869, backdated to the date of her son’s death. (1)

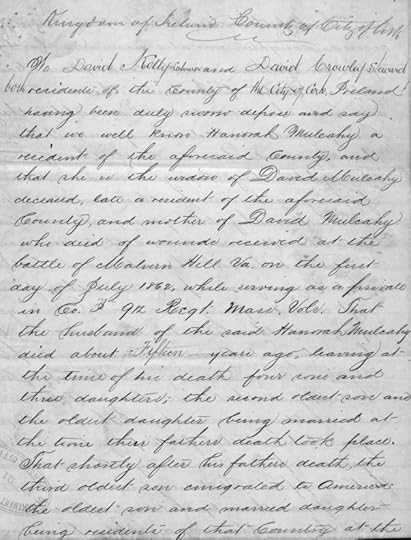

The first page of the David Kelly & David Crowley affidavit in the Mulcahy Pension File (Fold3/NARA)

Kingdom of Ireland: County of City of Cork

We David Kelly labourer and David Crowley steward both residents of Cork City both residents of the County of the City of Cork, Ireland having been duly sworn depose and say that we well know Hanorah Mulcahy a resident of the aforesaid County, and that she is the widow of David Mulcahy deceased, late a resident of the aforesaid County, and mother of David Mulcahy who died of wounds received at the battle of Malvern Hill Va. on the first day of July 1862, while serving as a private in Co. “A” 9th Regt. Mass. Vols. That the husband of the said Hanorah Mulcahy died about fifteen years ago, leaving at the time of his death four sons and three daughters; the second oldest son and the oldest daughter being married at the time their fathers death took place. That shortly after his fathers death, the third oldest son emigrated to America, the oldest son and married daughter being residents of the Country at the time their fathers death took place. That the second daughter was also married shortly after her fathers death took place, leaving still residents of Ireland the second oldest son, and the second oldest daughter they being married, and the youngest son the aforesaid David and the youngest daughter, they being unmarried and keeping a home for their mother. That David Mulcahy the youngest son aforesaid and who afterwards emigrated to America and was killed at the aforesaid battle while serving as a private in the aforesaid regt. and company was about eighteen years of age at the tome his third brother left home to go to America; and was employed as a printer in the Printing Establishment of Messrs Guy Brothers in Patrick Street in the City of Cork his salary at that time being about twelve shillings a week which he always gave to his mother for to pay house rent, groceries, provisions or any other articles necessary for her support.

70 Patrick Street in Cork, the address of David’s employment in the city prior to his emigration, as it appears today.

That his youngest sister who with himself was the only children who resided with their mother was a sickly person and on account of sickness was frequently compelled to leave off working and for that reason was of not help towards her mothers support; her earnings on an average being insufficient to support herself, and compelling her to be partly dependent on the said David for her support his mother, as she received no help from her other children, the oldest son being in America and was shortly after his fathers death married, and was unable to do any thing towards the support of the said Hanorah Mulcahy as he was a poor laboring man and had a family to support. That the oldest daughter was a resident of America also, and was unable to help her said mother as she was a poor widow with a young child to support; the third son doing nothing towards his mothers support as he enlisted in the U.S. service shortly after arriving there and his mother heard nothing from him for a number of years he being a man of unsteady habits. That the second oldest son and the second oldest daughter were married and still reside in Ireland unable to do any thing whatever towards the support of the said Hanorah, they being poor people and compelled to work very industriously to support themselves and their families. That the said Hanorah Mulcahy was wholly dependent upon her said son David Mulcahy who was late a private in the aforesaid Company and Regt. for her support; she receiving no aid from any of her other sons or daughters except the aforesaid youngest daughter who instead of being a help to the said David towards the support of her mother was herself partly dependent upon him on account of the aforesaid reasons.

An advertisement for Guy Brothers Printers in Cork from the time David Mulcahy worked there, dated 14th January 1857. David worked in the Patrick Street Warehouse (Cork Advertising Gazette)

That about eight years ago the said David Mulcahy emigrated to America and went to work at the curring [currying, part of the leather industry] business at Reading, Mass; he being employed at the printing business at the time he left home to go to America he being then about eighteen years of age and receiving a salary of about twelve shillings a week which he always gave to his said mother for their support, appropriating none of said salary to his own use he being a young man of very steady and industrious habits and doing all in his power to keep his poor mother and feeble sister off the charity of the town. That on arriving in America aforesaid and going to work at the curring business he received a salary amounting to about five or six dollars a week. That after his departure from home his mother was in very destitute circumstances; her youngest daughter the aforesaid sickly person doing all in her power to keep her mother out of the poor house until she would receive some aid from her son David. That about five months after his arrival in the U.S. the said David sent his mother about three pounds; his mother at the time of receiving the same being about to give up her little home and enter the poor house. That the said money enabled the said Hanorah to support herself, and still keep her little house for herself and her sickly daughter until she received more aid from said son David who continued to send his mother all he could possibly spare from his earnings after paying his board, and clothing himself, in sums of two and three pounds about every four or five months until his enlistment in the aforesaid Regt. and Company in the year 1861.

The Malvern Hill Battlefield. David Mulcahy and the 9th Massachusetts fought in the vicinity of these guns, with the Confederate attack moving towards the camera (Damian Shiels)

That up to the time of his enlistment in the aforesaid company and Regt. he had sent his mother about sixteen or eighteen pounds for her support; he receiving at the time of his enlistment a salary of about eight dollars a week, his salary having been increased gradually as he became more acquainted with the business at which he was employed. That the first time he received his pay after his enlistment he sent his mother three pounds and about six pounds after he received his pay the third time, which was the last money she received from him before his death which took place on the day and year above mentioned. That after his death the said Hanorah Mulcahy made application for the arrearages of pay due her; and at the same time the brothers and sister of the said David made application for the bounty money due on account of the services and death of the said David and received something over one hundred dollars in payment for said bounty and arrearages, the son and daughter in America appropriating no part of said bounty money to their own use but gave the whole amount of their shares to the said Hanorah for her support. That the youngest sister aforesaid died shortly after the news of her brothers death was received. That the said Hanorah Mulcahy now lives in a small room depending upon said bounty and arrearages for her support of which there is but a few pounds left, she being too old to earn enough to support herself and receiving no aid in any manner from the others of her aforesaid children and in possession of no real estate or any other property except a little clothing and a few housekeeping articles and the few pounds left of the said bounty and arrearages.

That we have no interest in the said Hanorah’s claim for a pension.

David Crowley Land Steward

David Kelly Labourer

Kingdom of Ireland County of Cork (2)

(1) Dependent Mother’s Pension File, Civil War Service Record, MacNamara 1899, Register of Deaths of Volunteers; (2) Dependent Mother’s Pension File;

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

David Mulcahy Dependent Mother’s Pension File WC81876.

David Mulcahy Civil War Service Record.

Cork Advertising Gazette 14th January 1857.

Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, compiled 1861–1865. ARC ID: 656639. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917. Record Group 94. National Archives at Washington, D.C. [Original scans accessed on ancestry.com].

MacNanmara, Daniel George. 1899. The History of the Ninth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Civil War Trust Battle of Malvern Hill Page.

Richmond National Battlefield Park.

Filed under: 9th Massachusetts, Battle of Malvern Hill, Cork, Massachusetts Tagged: 9th Massachusetts Infantry, Battle of Malvern Hill, Cork and America, Dependent Mother's Pensions, Guy Printers Cork, Irish American Civil War, Irish in Leather Trade, Irish in Massachusetts

March 3, 2016

Imagining the Horrors of Death: An Irishwoman Learns of Her Husband’s Death at Gettysburg

The battlefields of the American Civil War claimed thousands of Irish Famine emigrants. The families of some were fortunate, in that comrades took the time to write to them of their loved one’s final moments. But these letters did not always spare grieving relatives the gruesome imagery of war. Thankful as they must have been to receive them, one wonders to what extent the imagined final moments of husbands, sons and brothers were replayed and visualized in the minds of those left behind. Such may well have been the case for Mary Clark, from Co. Westmeath, when she received word on how her husband had lost his life on the slopes of Culp’s Hill, Gettysburg.

John Clark and Mary Farrell were married in Co. Westmeath on 31st December 1848. At the time John was around 23, Mary around 21. They were among the hundreds of thousands of Irish people who left the country during the Famine-era to head for a new life in the United States. It was in New York that they started their family, and the couple would eventually go on to have five children; Michael (b. 11th March 1854), John (b. 25th January 1856), Catharine (b. 1st February 1858), Mary (b. 5th January 1860) and Ellen (b. 27th December 1861). All bar one of the children were baptized in New York’s St. Francis Xavier’s Church on 16th Street in Manhattan. John and Mary are recorded on the 1855 Census with their one-year-old Michael, living in the 15th Ward. At that time John was employed as a laborer. By the outbreak of the Civil War, their home was 148 West 18th Street; John was by now working as a hostler. (1)

The part of West 18th Street on which the Clarks lived, as it appears on Google Street View.

John Clark was 35-years-old when he mustered in as a private in New York on 24th August 1861. He became a member of Company B of the 65th New York Infantry, the “1st U.S. Chausseurs” on 1st September that year. John was described as 5 feet 6 inches in height, with dark brown eyes, a dark complexion and dark hair. When he marched off to war Mary was 5 months pregnant with the couple’s fifth child, Ellen, who would be born that December. It is unclear if John ever had an opportunity to see her. A little more than a year and a half later he and the 65th New York– part of Shaler’s 1st Brigade, 3rd Division of the 6th Corps– marched onto the Gettysburg battlefield. On the evening of the 2nd July the regiment was held in reserve on the left, but at 8am on 3rd they were ordered to the army’s extreme right. Their function was to support General Geary’s position on Culp’s Hill. As the Confederates attacked, John and his comrades were directed to form a reserve, and duly “took a sheltered position in rear of a piece of woods, beyond which the action was then progressing.” The 65th New York would never be called forward into direct combat from this location, near where its monument stands on the Gettysburg battlefield today. As a result, the unit’s Gettysburg casualties were extremely light. But no matter where you are positioned, battlefields are deadly places. So it proved for John Clark, who met a grisly on Culp’s Hill as he awaited his orders to advance. His fate was described in two letters written to Mary by men of the regiment. (2)

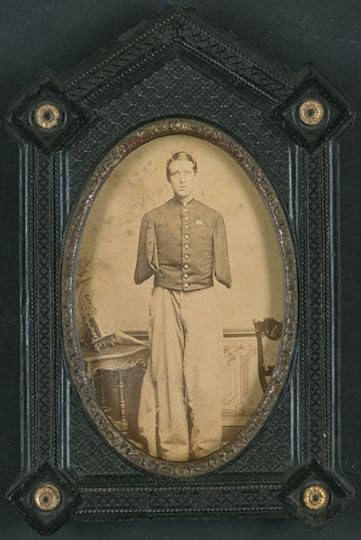

A young soldier dressed in Chausseur uniform, possibly a member of the 65th New York (Library of Congress)

Camp 1st U.S. Chasseurs

Near Warrenton D.C.

July 30th 1863

Mrs Mary Clark

Madam,

Owing to the absence of the officer in command of Co “B” I will endeavor to answer your letter regarding you husbands death. Corporal John Clark Co “B” 1st U.S. Chausseurs was struck with a piece of shell on the morning of the 3d day of July at 11 o’clock. The regiment was laying down awaiting the order to advance to the front when a shell exploded over the Reg’t killing him and wounding another man by his side.

One of his comrades carried him off the field to the Hospital and if he said any thing to him I cant say as he was wounded soon after and while on his way to join his Company and no word has been heard from him.

John’s own officer is now in New York for conscripts with his Head quarters at 274 Canal Street in the store of the Water Furnace Company. I will write him a letter and give him you direction so he can call and see you if he has time.

You would do well to call and see him and he probably may assist you in getting the relief money.

I came out in the same Company with your husband as a Sergeant and I have had good chances of knowing the man and I but speak the feelings of all his comrades in saying that a better soldier, companion or friend was not to be found in the Regiment and all his comrades deeply sympathize with you in the loss of such a husband– If there is anything his comrades can do they wish me to say they are at your service and if any further information is needed I will cheerfully grant it.

Believe me Madam,

A sincere friend of you late husband & one who sincerely sympathizes with you in your loss,

Respectfully,

Your Obed’t Ser’t

Adjutant William J. Haverly

1st U.S. Chausseurs (3)

William J. Haverly was 26-years-old when he was enrolled as a Sergeant in Company B on 3rd August 1861. He was discharged for disability holding the rank of Captain on 15th November 1864. (4)

274 Canal Street, the site of Brown’s Water Furnace Company, as it appears today. It is likely that Mary Clark visited Lieutenant Raymond here in 1863 to find out more about her husband’s death at Gettysburg. Promoted Captain to date from 1st July 1863, Raymond was dismissed on 7th March 1864 for being absent without leave.

The second letter was sent by Louis Thirion, a Pennsylvania-born jeweler, who had enlisted at the age of 29 in Company H on 20th August 1861. (5)

Camp near Warrenton Va

July 31st 1863

To Mrs Mary Clark

Dear Madame,

It is with regret I announce to you that your husband was killed in the Battle of Gettysburg the 3rd of July at about 11 O’clock. He lingered for about 4 hours when death put an end to his sufferings. He was universally beloved in the regiment, but more particularly in our company where he was better known. By his death the regiment loses the services of one whose place it will be difficult to fill. In passing this tribute to his memory I but re-echo the sentiments of the entire command. I sincerely sympathize with you in the irreparable loss you have sustained, whereby you have lost a kind husband, and your children an affectionate father. May his soul rest in peace. Our Lieutenant whose is name is George S. Raymond is in your city detailed to bring on conscripts. I think you will find him at the Howard House or somewhere in that vicinity. He can give you more information than I possibly can give you on paper.

Your husband was laying on his back calmly talking of the “Union” when a fragment of a shell struck him nearly taking both legs off.

Wishing your sorrows may be alleviated by the consolation of knowing he died a glorious death.

I remain,

Your Obedient Servant,

Serg’t Louis Thirion Co ‘B’

65th N.Y.S.V. 1st Brigade 3d Division

6th Corps Washington D.C.

Although a Sergeant when he wrote this letter, Louis was returned to the ranks in June 1864. He mustered out on 17th July 1865. (6)

It is apparent from both letters that the Westmeath man was very popular among the regiment. Evidently Mary, having learned of John’s death, had written seeking further details regarding his demise. It is not hard to imagine her turning over the image of her husband’s horrifying and agonising final hours in her mind. Although Thirion in particular gave her explicit detail as to how John had been wounded, it is interesting to note that the Sergeant also related that John had been “calmly talking of the Union” when he was struck. Whether this was the truth, or whether he added it to provide more meaning for his sacrifice, is unknown, but Thirion’s hope that Mary would be consoled by John’s “glorious death” implies it may well have been the latter. John Clark’s body was identified and he was buried in the New York plot at Gettysburg National Cemetery. How Mary fared with her five young children goes unrecorded, but it is notable that when she applied for an increase to her pension in 1865 based on her minor children, only four were listed– the absent child was the couple’s fifth, their young daughter Ellen, who had been born when her father had marched away to war. (7)

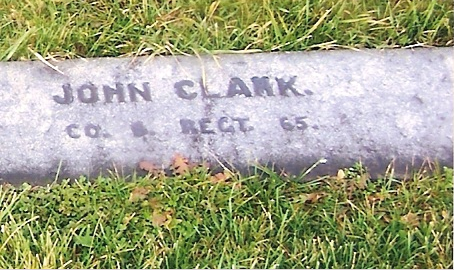

John Clark’s memorial in Gettysburg National Cemetery (Photo: Pat Callahan, Find A Grave)

(1) John Clark Widow’s Pension File, 1855 New York Census; (2) 65th New York Roster: 477, John Clark Widow’s Pension File, Official Records: 680-1, Pfanz 1993: 324; (3) John Clark Widow’s Pension File; (4) 65th New York Roster: 558; (5) New York Muster Roll Abstracts; (6) 65th New York Roster: 717, New York Muster Roll Abstracts; (7) John Clark Widow’s Pension File;

* None of my work on pensions would be possible without the exceptional effort currently taking place in the National Archives to digitize this material and make it available online via Fold3. A team from NARA supported by volunteers are consistently adding to this treasure trove of historical information. To learn more about their work you can watch a video by clicking here.

References & Further Reading

John Clark Widow’s Pension File WC50400.

Census of the state of New York, for 1855. Microfilm. New York State Archives, Albany, New York.[Original page scans accessed via ancestry.com].

Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts of New York State Volunteers, United States Sharpshooters, and United States Colored Troops [ca. 1861-1900]. (microfilm, 1185 rolls). Albany, New York: New York State Archives.[Original scans accessed via ancestry.com].

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion Series 1, Volume 27, Part 1. Reports of Brig. Gen. Alexander Shaler, U.S. Army. commanding First Brigade , Third Division.

Pfanz, Harry W. 1993. Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill & Cemetery Hill.

New York Adjutant General. Roster of the 65th New York Volunteer Infantry.

Corporal John Clark Find A Grave Memorial.

Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “New York City:the fatal panic, on the evening of March 8th, in the Church of St. Francis Xavier, Sixteenth Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed March 3, 2016.

Pat Callahan Find A Grave Contributor.

Gettysburg National Military Park.

Civil War Trust Battle of Gettysburg Page.

Filed under: Battle of Gettysburg, New York, Westmeath Tagged: 65th New York Infantry, Civil War Condolence Letters, Irish American Civil War, Irish at Gettysburg, Irish in New York, Westmeath & America, Westmeath Emigrants, Widow's Pension Files

February 23, 2016

Union Rebels: Civil War Veterans & the Fenian Campaign in Britain & Ireland, 1866-1868

In Part 2 of the guest series on the participation of American Civil War veterans in the operations of the Fenian Movement, James Doherty takes a look at events such as the suspension of Habeas Corpus, the creation of the “Manchester Martyrs” the Temple Bar shootings and the Clerkenwell Bombing. Virtually every major Fenian incident that took place in Britain and Ireland during the late 1860s involved a number of men who had fought for the Union during the Civil War– as we will discover below.

The first part of this article looked at the phenomenon of how the American Civil War acted as a breeding ground for militant Irish Nationalism and examined the failed gun-running expedition carried out by Fenians in 1867. The wide scale rebellion that the Fenians were planning to supply never materialised, but subsequent events would show that the threat from their movement was far from over. Ireland in 1867 was a tense and dangerous place– skirmishes had occurred between police and Fenians and there was sightings of mysterious boats lurking off the Irish coast. Fenian cells, or circles as they were known, existed in most Irish and many British towns and cities. Rumours persisted of the existence of “Fenian Fire” a substance like naphtha that was to be used in incendiary attacks on government buildings. Large numbers of returning veterans of the Civil War added to this already dangerous milieu. The term Fenian Fever* was adopted by the popular media as fears of insurrection or large scale attacks created a level of panic. The British authorities governing Ireland were anxious, to put it mildly. (1)

Officers of the 15th New York Engineers during the Civil War. Prominent Fenian Ricard O’Sullivan Burke (discussed below) served as an officer in this regiment (Library of Congress)

Draconian measures were introduced to help maintain law and order and to prevent further attempts at rebellion. Habeas Corpus (the legal requirement to bring a detained person before a judge or court) was suspended which meant that people could be arrested and imprisoned indefinitely based solely on suspicion. Between February 1866 and March 1867 seven hundred and seventy seven men were arrested under these emergency powers. Interestingly, out of this group of internees over a hundred were released under condition that they leave for America, indicating where many had originated. The Waterford News complained of a “police reign of terror” and noted how transatlantic American passengers feared to disembark at Cobh for fear of arrest. Responding to the rumoured existence of “Fenian Fire” the British authorities ordered sand to be spread on the floors of public buildings in an attempt to hinder arson attacks and recruited thousands more police constables. (2)

The closing months of 1867 would witness a series of events that involved veterans of the Civil War and would show both how dangerous and unpredictable the Fenian movement could be. Earlier that year, after the failed Irish rebellion, many of the Fenian leadership had been rounded up. Two of its leaders, Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy, escaped capture and travelled from Ireland to Britain to reorganise the movement there. Kelly had served as captain in the 10th Ohio Volunteer Infantry and Deasy as first lieutenant in the 9th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, units which both had significant Fenian elements. The Fenian movement in Britain and Ireland was in a state of flux. The rebellion had been a failure, the movement had been infiltrated by informers and many of its best men where in prison. Thomas Kelly was acting head of the Fenian operation in Ireland and Britain and set about the task of reinvigorating the organisation so that it could once more work towards its goal of an independent Ireland.

In September 1867 Kelly held a key meeting, where in addition to consolidating some of the depleted Fenian circles he was elected as the undisputed head of the movement. Over 150 Fenian delegates attended the meeting which was chaired by Captain James Murphy (late of the 9th Massachusetts) and Ricard O’Sullivan Burke. O’Sullivan Burke was the Fenian agent who had met the Erin’s Hope gun running expedition on the Irish coast and was now based in Manchester. O’Sullivan Burke was a larger than life character who had travelled the world and had also served in the Civil War with the 15th New York Engineers. He was now an arms procurer for the Fenian movement. (3)

On the night of 11th of September, when Kelly and Deasy left a Fenian safe house in the Smithfield Market area of Manchester, a Policeman stepped from the shadows and ordered both men to halt. The constable had no idea that these were two of the most wanted men in the British Empire, but had arrested them under the vagrancy act as he suspected them of burglary. They both gave false names and were several days in custody before their true identity was confirmed. (4)

Memorial to the Manchester Martyrs in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin (Damian Shiels)

The men’s capture was a major set-back for the Fenians, which had occurred just as Kelly was breathing life back into the organisation. The local Fenian leadership under O’Sullivan Burke and Edward O’Meagher Condon plotted to free the two prize captives. Condon was yet another veteran, having served in the 164th New York Infantry, and he immediately began surveillance on the magistrates court where Kelly and Deasy were due to appear. (5)

On the afternoon of the 18th of September the two Fenians, along with three other prisoners, left the Bridge Street Magistrates Court headed for the old city gaol at Belle Vue. They were being held in a horse-drawn “Black Maria” police van; six police rode on top with another officer– Sergeant Brett– travelled inside. All of the police were unarmed. When the van approached the Hyde Road Bridge a group of thirty to forty Fenians emerged, using sticks and stones to attack the police and threatening to open fire. The six police on top fled, leaving only the officer locked inside the van, who also had the keys. Threats were made and the brave Sergeant Brett reportedly replied “I’ll do my duty till the last”. It is believed an attempt was made to shoot the lock off, but the bullet passed through the keyhole, killing Sergeant Brett instantly. Another prisoner passed out the keys to the rescuers and Kelly and Deasy made their escape. However, due in part to the actions of Sergeant Brett, the escape had taken much longer than anticipated. A large hostile crowd had gathered and scuffles had broken out. Guards from the nearby prison also started to arrive and join in the melee. Although the two prisoners escaped, many rank and file Fenians and the raid leader Condon were arrested. Over the next few days, and amidst scenes of anti- Irish hysteria, anyone suspected of having Fenian links was rounded up. Between fresh suspects and those arrested at the scene 28 men were brought forward for trial. Five of them were sentenced to hang. (6)

Two out of the five were Civil War veterans. In addition to the aforementioned Condon, another of the condemned men, Michael O’Brien, had served in Battery E, 5th New Jersey Light Artillery. One of the five, Thomas Maguire, was released due lack of evidence and thanks to the intercession of senior American diplomats Condon’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. The remaining three men– Michael O’Brien, William Philip Allen and Michael Larkin– were hanged amidst tight security on 23rd November 1867. Their names were immediately immortalised by the Irish nationalist movement as the “Manchester Martyrs.” Whilst events in Manchester unfolded Fenian violence flared in Dublin. The movement was well aware of how badly infiltrated their ranks were, and rumours persisted of a shooting circle– a team of assassins sent from America to eradicate informers. The Dublin Metropolitan Police were an unarmed force, but, somewhat ironically, in the winter of 1867 many had resorted to carrying weapons seized from the Fenians earlier in the year. On 31st October (Halloween night) Constable John Kenna approached a suspicious looking character on a dark unlit street in the Temple Bar area of Dublin. The suspect turned suddenly towards Kenna and shot him in the chest, wounding him fatally. Moments later a second constable rushing to Kenna’s aid was shot and seriously wounded. Something akin to panic gripped officialdom; first there was the escape of the Fenian chiefs Kelly and Deasy (who had by now surfaced to a heroes welcome in New York) and now police officers had been gunned down on the streets of Dublin. A major police operation soon swung into action as the establishment demanded a response. Once again the Fenians were informed upon, and a Patrick Lennon was identified as the leader of the so called “shooting circle”. (7)

Patrick Lennon was one of the hard men of the Fenian movement. His military career began in the British army where he saw action during the Indian Mutiny. He ran from the army but was caught and branded with the letter “D” for deserter. Lennon would later travel to the States where he supposedly served in a New York cavalry regiment. After the war Lennon flitted over and back between Britain and Ireland conducting Fenian business, and proved to be an elusive target. His luck ran out on the evening of the 8th January 1868, when he was apprehended by two detectives. Ominously he was carrying a list of the home addresses of senior administration officials in Ireland. Although he gave a false name, he was quickly identified through his branded scar. Over the next few days the newspapers were alive with the news of the capture of the notorious Fenian triggerman. At his trial, Lennon proudly admitted to being a member of the Fenian movement, but denied any involvement in the murder of Constable Kenna in Temple Bar. His murder trial collapsed due to lack of evidence, but he received 15 years hard labour for Fenian membership. At his trial an unrepentant Lennon stated his hope that the British Monarchy would collapse before his sentence expired, and avowed that he would gladly take up the Fenian cause again. (8)

Portraits remembering the Manchester Martyrs. American Civil War veteran Michael O’Brien is at left (Library of Congress)

In the winter of 1867 support for the Fenians ran high. Their PR machine had made a victory out of the failed Erin’s Hope expedition, portraying it as a David v Goliath type mission. The execution of the Manchester Martyrs triggered great resentment and anger within Ireland and the global Irish diaspora. As far away as New Zealand mock funeral processions were carried out in Irish communities. However, this surge in public sentiment would prove fleeting. (9)

The Fenian arms agent Ricard O’Sullivan Burke had been a constant in nearly all the Fenian “outrages” of 1867. On the 20th of November Burke was arrested in London and remanded to Clerkenwell prison. Once inside he started to plan his own escape. He smuggled out a note requesting that a hole be blown in the wall of the prison whilst he was out of his cell exercising. The escape plan went disastrously wrong. On Thursday the 12th of December the Fenians placed a gunpowder keg against the wall of the prison, but it failed to ignite. Unperturbed, they returned the next morning and tried again. The explosive was vastly overpowered and caused terrible loss of life and destruction in the streets surrounding the prison. Burke was fortunate that he had been ordered to exercise in a different part of the prison, as no one in the exercise yard would have survived. The escape attempt failed and Burke was sentenced to fifteen years hard labour. (10)

Eight men were arrested for the botched Clerkenwell bombing, but only one– Michael Barrett– was ever convicted, and that was on questionable evidence. In what was to be the last public execution of the Fenians he was hanged on the 26th May 1868. The bomb had ripped through a row of tenement houses behind the gaol causing twelve deaths and fifty injuries. Unlike the Fenians hanged for the rescue of Deasy and Kelly, the reckless nature of the Clerkenwell bombing ensured that Barrett didn’t enter the Fenian lexicon as a martyr. (11)

1867 marked the high water mark for militant Fenianism and its trans-Atlantic connection. Public support for the organisation had peaked after the hanging of the Manchester Martyrs but had sharply declined after the Clerkenwell bombing. The failed rebellion and the subsequent chaotic events that followed both in Britain and Ireland led the Fenian leadership to withdraw from the pursuit of violent rebellion and work towards influencing public policy in America around the issue of Irish independence. However, Fenian violence would return again in the in the 1880s, when a series of public buildings were bombed in what became known as the “Dynamite War.” (12)

One of the most interesting characters in the dramatic events of 1867 was Ricard O’Sullivan Burke. After his plot to rescue himself from prison failed, he faced a lengthy sentence in the harsh conditions of the Victorian prison system. In just three years it was reported that he was broken both mentally and physically. After pleas for clemency he was released in 1871 and returned to the America. After his release, the enigmatic O’Sullivan Burke quickly perked up and acted as an engineer to the Fenian movement. He was heavily involved in plans in the 1880s to develop the “Fenian Ram” a submarine designed by the Irish man John Holland that (it was hoped) would help to end British supremacy at sea. His adventures weren’t over; in 1881 Burke eloped with a girl half his age. He died at the age of 84, having remained committed to the Fenian cause all his life. (13)

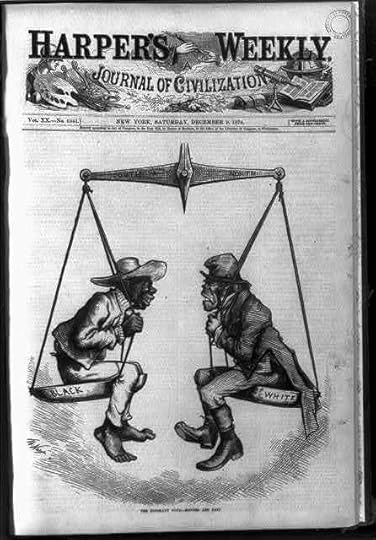

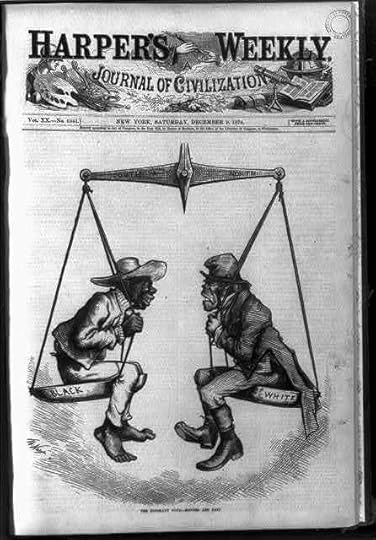

“The Fenian Guy Fawkes” a caricature carried in Punch Magazine, December 1867, and reflective of the anxiety being caused by Fenian operations (Punch)

*The term was first used in America in 1866 to describe the panic caused by the Fenian Raids into Canada, but by 1867 was being widely used by the media.

(1) Beiner 2014; (2) British Parliamentary Papers, The Waterford News, Beiner 2014; (3) O’Neill 2012, Kane 2002; (4) O’Neill 2012; (5) Ibid.; (6) Ibid; (7) Ibid., Kane 2002; (8) Ibid, Sydney Morning Herald, The New Zealand Press; (9) Ibid; (10) The New Zealand Press, Feniangraves.net; (11) Staniforth 2012; (12) Ibid.; (13) Dictionary of Irish Biography;

References

The Waterford News 14th February 1868.

Sydney Morning Herald 3rd April 1868.

The New Zealand Press 9th October 1909.

Enhanced British Parliamentary Papers On Ireland. Return of Number of Persons in Custody in Ireland under Habeas Corpus Suspension Act released from Imprisonment, and Number arrested, February 1866-67.

Beiner, Guy. 2014. “Fenianism and Martyrdom– Terrorism Nexus in Ireland before Independence” in Dominic Janes & Alex Houen (eds.) Martyrdom and Terrorism.

Kane, Michael H. 2002. “American Soldiers in Ireland, 1865-67” in The Irish Sword: The Journal of the Military History Society of Ireland, Vol. 23, No. 91, pp. 103-140

Kennerk, Barry 2010. Shadow of the Brotherhood: The Temple Bar Shootings.

O’Neill, Joseph 2012. The Manchester Martyrs.

Staniforth, Andrew 2012. The Routledge Companion to UK Counter-Terrorism.

Filed under: Discussion and Debate, Guest Post Tagged: Civil War Fenians, Clerkenwell Bombing, Fenians in America, Irish American Civil War, Manchester Martyrs, Ricard O'Sullivan Burke, Suspension of Habeas Corpus, Temple Bar Shootings

February 14, 2016

“Their Cries Were Most Agonizing”: An Irish-American’s Overland Account, from The Wilderness to Petersburg

Between 11th June and 9th July 1864, the New York Irish American Weekly ran a series of letters from a young man to his brother back in New York. Taken together, they offer a highly detailed account of his experiences with the 147th New York Infantry during the Overland Campaign. Written on almost a day-by-day basis, they describe the campaign from its opening clash at the The Wilderness all the way through the 18th June assault at Petersburg.

The author of the letters was Irish-American Thomas W. Kearney. He enlisted in the 147th New York– an Oswego County regiment– at Richland on 26th March 1864 and mustered in as a private in Company K. The 20-year-old had been born in New York City, and was described as 5 feet 6 1/2 inches tall with hazel eyes, black hair and a light complexion. In civilian life, Thomas had been a clerk, which goes some way towards explaining his degree of literacy. His account of the Overland Campaign appeared across three letters written to his brother from the front, which were published in the New York Irish American Weekly. Given his position within the army, Thomas seems to have had a lot to say with respect to wider army operations; perhaps his professional skills were put to use by some of the officers of the regiment, thereby giving him access to more information. The letters themselves slip in and out of diary form, suggesting Thomas was keeping daily notes, but was also returning to expand on specific areas of his text. Although he describes a number of actions, by far the most powerful account deals with the 147th New York’s participation in the assault at Petersburg on 18th June, which is to be found in his final letter. Much of Thomas’s life both before and after his time in the regiment remains unclear. He may have had prior military service, but he disappears from the records in January 1865. At some point during that month he took the decision to desert from the army while on furlough. Whether he did so because he had grown tired or disillusioned with the fight, or because of personal, family or some other reason is unknown. If any readers have any further detail to add to the picture of Thomas Kearney’s life I would be glad to hear from them.

Wadsworth’s division in action during the Battle of The Wilderness (Library of Congress)

The first letter is the most extensive of the three, and deals with the fighting from The Wilderness through to Laurel Hill and Spotsylvania, ending on 18th May– it was published on 11th June:

BIVOUAC ON FIELD, NEAR SPOTTSYLVANIA COURT HOUSE, VA., MAY 17, 1864.

Dear Brother– Thinking a brief account of our present campaign would prove a little interesting to you and some of the friends, I herewith send it. We started on the march from Culpepper, Va., on the 3d instant, as 12 1/2 o’clock at night, marching all night until 10 o’clock, A.M., when we crossed the Rapidan at Germania Ford, and continued marching until we came to Gold Mine, where we encamped for the night. On Thursday, May 5th, we marched up the road to the right about two miles, where we formed in line of battle and marched to the west towards Mine Run. We had not gone far before we met the rebels in the woods in two lines of battle marching to meet us. Here our battle opened; our line and the rebels fired at about the same time. After each fire of the first line of the rebels, they lay down and let the second line fire; thereby keeping a continuous fire upon us all the time, which proved very destructive to our regiment. Our Colonel (Miller) fell here mortally wounded, while rallying his men on the left of his regiment. This place was called “the Wilderness” and true enough it was a wilderness. Col. Miller acquitted himself on this occasion very creditably. No officer in the army of the Potomac could display more courage and bravery than he did that day. The losing of such a brave and gallant officer threw gloom over the whole regiment. Meanwhile, the right of the regiment was manoeuvred by Lieut.-Col. Harney with great coolness and bravery. Company K (our company) was the second in line, forming the 1st division. The casualties in our company were very heavy. Our 1st Lieutenant, Hamblin, was wounded in both arms– one broken below the elbow, and the other having a flesh wound [A 32-year-old farmer from Oswego County, he died of his wounds on 25th June]. Our killed, wounded and missing, on the first day, were twenty-one men; the company went in with 57 guns, and came out with 28. After being under such a destructive fire for some time, we received ordered to fall back, but not until the rebels were close upon us. Much credit is due to Capt. Dempsey, for a braver and cooler officer or better soldier there can not be found in our army [37-year-old Captain Joseph Dempsey was from Ireland and was a speculator in Oswego before the war; he would survive his service]. As the rebels were within hailing distance of us one of our corporals called out to him that he was wounded; and Capt. D. immediately went to his rescue, regardless of his own life; and while in the act of assisting the poor wounded man, one of his sergeants fell mortally wounded in the head. Meanwhile the rebels had been advancing. They were but a few yards from the Captain when we called out to him from behind, for God’s sake to come on or he would be taken prisoner. He turned, saw the rebels and how he was situated, and what few men he had, order to fire; but at that time the rebels let fly a volley from the left, which compelled him to fall back. The Captain then fired a gun, and the rebels perceiving where the smoke issued from, poured in a deadly volley. I thought our Captain Joe was not more; but thanks to kind Providence, who saved him that time, and he immediately fell back and rallied his men on the clearing in line of battle. It is my opinion that our division had to stand before a whole division of rebels; and what was more, there was not event the slightest reserve to fall back on.

About 5 P.M., the whole division again formed in line of battle, and marched in the woods to the east, the line running north and south. We charged the rebels in the woods for the purpose of getting possession of the road leading to Spottsylvania Court House. We drove them steadily before us until dark. At the break of day, we were ordered to move forward, which we did, and drove them three quarters of a mile out of the woods. When we came to the edge of the woods, we saw Gen. Wadsworth (Our Division General) riding up and down the line (between our’s and the rebels’ fire), hat in hand, cheering on his men. Our boys gave him three hearty cheers, and moved forward on the double-quick across a clearing about fifteen yard wide, which brought us on to a pine thicket. We fired a volley through the thicket, and in return received a terrible charge of grape and canister, which mowed down men and trees like so many scythes. It seems the rebels had a masked battery about four rods off, which they opened on us when they got us near enough to them. At this charge Gen. Wadsworth was killed. We were then ordered to fall back slowly. Part of our brigade went south east through the woods, and getting possession of the Spottsylvania road, commenced throwing up breastworks: and soon after the Second Corps came up and did likewise.

In the afternoon about 4 P.M., the rebels charged our breastworks in from of the Second Corps, and planting their colors on their works, captured two stands of colors. Gen. Rice, commanding our brigade, ordered his men to charge the rebels, which they did, and recaptured the colors, and jumping over the breastworks after the rebels, killed and wounded many. One of the rebel prisoners we captured said that the charge in which Gen. Wadsworth was killed was led by Lee in person. Our line of battle now extended from the Rapidan, on our right, to about four miles on the plank road leading to Spottsylvania Court House. On this day we were reinforced by the arrival of the Ninth Corps, which immediately went into action and commenced throwing up breastworks. This day our company lost two men by being wounded; and a chum of mine from Oswego, named Dennis Deegan, is missing yet [a 20-year-old Irishman and former sailor, Deegan was captured at The Wilderness, but survived to be paroled in April 1865]. The next day being the third day of the fight, our brigade was ordered to the right to assist the Sixth and Ninth Corps; but nothing of much importance transpired while we laid here. About 5 P.M. we were relieved, and marched back to Gold Mine about 8 P.M. We then marched to the left, towards Spottsylvania Court House, about 15 miles– marching all night without any rest. We were the head of the column of the Fifth Corps. We marched onward for miles, till we came up with the cavalry, and they reported the enemy in force about a mile ahead. We stopped about an hour and got breakfast– that is, a collation of coffee and “hard tack.” We then again started on and went towards the foe. The rebels had felled trees across the road to prevent our progress, and soon with a desultory fire opened upon us; but we drove them before us about two miles, when we came to a place called Petersburg, where is a large clearing. Here they opened on us with a deadly fire of shell. Here our Brigadier-General Rice, showed himself a very brave and Christian man. He spoke very coolly, and said to us– “Follow me, men, and God will protect us!” We did so up a small hollow, and went into a small piece of woods and formed in line of battle, and marched on the rebel line and were engaged very hotly for about three hours, when we drove them from their position. One man of our company was wounded with a piece od shell in the hand: Co. A had 2 men killed. The regiment here experienced a heavy loss; our men and officers fought like tigers, and got great praise from the other regiments in our brigade, as the lone on our right gave way, comprising the 3d brigade of Pennsylvania Bucktails, which was afterwards sent to the rear. The same night the rebels made a very heavy charge on our left, but it was repulsed with a heavy loss by a part of our corps and the Sixth on our right. A heavy cannonading closed the ball of the fourth day.

The fifth day, armed with shovels and picks, we threw up more breastworks, and threw out a heavy line of skirmishers. There was beavy firing all along the lines, but the heaviest was on the left, with the 6th corps, where Gen. Sedgwick got killed; and it was reported that we took a great many prisoners. In our company we lost one man this day. We slept on our arms all night, and the rebels made two bold assaults, but were as boldly repulsed.

The sixth day, about 11, a.m., heavy firing began on our right and left, but they were only feints to break our centre. The rebels massed their troops to carry our works; but we sent two lines of battle forward in the woods to meet them, and compelled them to fall back. In this charge we had hard fighting for two hours. Lieut. Col. Harney was wounded in the face by a piece of shell, and was compelled to leave the field, but returned and resumed command the next day [29-year-old George Harney would survive his service to muster out with the regiment]. About 5, p.m., the same day, we formed four lines of battle in the woods for the purpose of charging the rebels’ works, and the 2d corps was to do the same on our left; the 147th (our Regiment) was in the third line, with bayonets fixed, but did not move far before the enemy perceiving our motive opened upon us with grape and shell. There were pine trees, a foot in diameter, cleanly cut across with the shell, and the woods fairly rained with grape shot, but yet, by all appearances, our loss was small. By some reason or other, the corps on our right failed to move forward, and after firing four or five volleys, darkness set in, and we fell back to our rifle pits. Gen. Rice was killed in this engagement; he was wounded in the thigh and shattered to the hip. He was carried to the hospital, about two miles to the rear, where he died two hours after amputation. The officers and men under his command regret his loss very deeply, as he was beloved and esteemed by all our company. This day we lost three men wounded; and our old war-horse of a Captain, was wounded, or at least hit twice with a shell; but be never left the field; the boys call him Fighting Joe; he is a regular warrior. There was heavy skirmishing all along the lines during the whole night, and it was reported that Burnside had captured 2,000 prisoners, and twenty-three pieces of cannon. We laid on our arms all night, as the heavy skirmishing continued.

The seventh day brought heavy cannonading for about an hour all along the lines in the forenoon. We kept the enemy busy in our front, while we erected more breastworks, and planted more cannon, which kept up a fire through the night. This ended the seventh day of strife of any note. Col. Harney came back from the hospital, and resumed command of the Regiment, which pleased the officers and men very much, as they repose great confidence in him.

The eighth day, before daylight, we were ordered to pack up and move to get in line, the 2d corps on our right being moved to the left. The morning was very dull, wet, and foggy. As soon as daylight appeared, the cannonading opened. Our Brigade moved forward out of the breastworks and attacked the enemy. The musketry was very heavy on both sides, and the shelling very hot. Our company, in this engagement, lost several men in killed and wounded; a lieutenant, named Browne, lost a leg here, and was amputated above the knee. The 2d corps made a charge on the Rebels breastworks, and carried them with 4,000 prisoners, four generals, and fifteen pieces of cannon. They belonged to Johnson’s Division, Ewell’s Corps. We were ordered up; but it was merely to support the 2d and 6th corps. We are now lying in the Rebel rifle pits, which we took from them. The evening’s loss this day, in killed, wounded, and prisoners, must have been very heavy. We have used a great deal of artillery.

May 13th, 2, a.m., we have just been relieved from the intrenchments. We had to keep a heavy fire on the enemy all night, to prevent them from advancing on our works, as we were not properly prepared for them. When we got relieved, it was raining, but you may bet your pile we could lie down and sleep, too, if it was all mud. Only imagine a man having no rest for nine days and nights, and you will jump at the conclusion that he can sleep it it is a mud hole. 11, a.m., same day, everything is quiet along the lines. Burnside has gone further on the left about seven miles, and on their flank. Where we are now, is on the rebels’ right flank, so you can perceive that it is turned, and, consequently, leaves us in possession of the Fredericksburg road, and also the Bowling Green road. 4, p.m., same day (13th), there was an ordered read to us, conveying the happy tidings that Gen. Lee was driven from the line of the Rapidan, and that we had captured 8,000 rebel prisoners, and complimenting the troops highly for the work they so nobly performed. Nothing of much note transpired during the day. We are at work now making more and stronger breastworks inside our old lines. 10, p.m., same day, we marched from the right to the left, a distance of twelve miles. Lee’s army is in the shape of a wedge. On the 13th, our line of battle faced the south-west, and on the 14th, the north-west; we had a very muddy march all night, the mud being over a foot deep, and the little runs were so high that we were compelled to ford them, being three feet deep. Here we relieved Burnside’s corps; the Rebs were in force on our front on a high position near the Spottsylvania Court House, throwing up earthworks and mounting guns, so we set to work throwing up breastworks also, as we anticipated they would charge us, to get possession of our works, and the road running parallel with the railroad, so we extended our lines six miles further to the left, and towards the south; the railroad is in our rear about four miles; our communication is open to Belle Plains.

This being the tenth day of battle, we kept up a heavy cannonading all day on the rebels. They held possession of a high eminence in our front about half a mile off. We charged on and drove them from it, but they charged and shelled in the afternoon and drove us back; but just before dark we formed in lone of battle and advanced at the same time, opening on them with shell, and succeeded in retaking the place. The rebels ran into the cellar of a house that was there, for safety, which some rebel General had for Headquarters. We got thirty fine horses in the barn already saddled which they had no time to take away before we were on them.

May 15, 2 p.m. Everything is pretty quite along the lines to-day. There was some cannonading on our right. The men on our left were busy all night making breast works; so that they can hold the place without much force. There was a reinforcement of convalescent soldiers, numbering 7,000 men came in to-day from the different hospitals through the country. It was Brigaded and officered by a good many from the old Irish Brigade. Some of the men were of our regiment who had been wounded at Gettysburg battle; and when they heard that our regiment was so near them they made a bolt and joined us. It is rumored that we are reinforced by 30,000 men. The weather is dark and threatening heavy rain. our cavalry are all out toward Richmond. The rebels moved last night; but when daylight came they found, to their great surprise, the Second Corps in their front.

May 16th and 17th. There has nothing of any account transpired along the lines.

May 18th. Quite a brisk cannonading commenced this morning and lasted about one hour. On our right two divisions of the old Third Corps charged and took two rows of the rebel rifle pits. All quiet the rest of the day. May 19. To-day all quiet. Our Division are the only troops now on the right of the Third Corps, and Burnside’s Ninth Corps went away in some other direction. We were engaged fighting already for twelve days– fighting eight battles, commencing at the battle of the Wilderness, and ending at the battle of Laurel Hill.– I remain your affectionate brother.

THOS. KEARNEY,

Co. K, 147th N.Y. Vols., Warren’s Corps, Wadsworth’s Division, Rice’s Brigade.

“Spot where Gen. Wadsworth, USA, fell. Shattered tree struck by same shell that killed his horse” (Library of Congress)

Thomas’s next letter takes up the campaign from the crossing of the North Anna to end of the fighting at Cold Harbor, and was published on 2nd July:

LETTER FROM THE 147TH N.Y. VOLS.

BIVOUAC ON CHICKAHOMINY RIVER, NEW KENT COUNTY, VA.

June 10th, 1864.

Dear Brother– The last account of our army movements that I sent you, was up to the 20th of May. Nothing of any importance transpired until the 23d, when we crossed the North Anna River at Jerico’s Ford, where our corps (the Fifth), under the command of Major-General Warren, crossed about 5 P.M. The 1st and 4th divisions of this corps were compelled to wade the river, as the pontoons had not arrived. Having crossed the river, we formed line of battle and marched forward about half a mile, in the direction of a piece of woods, where the enemy had their troops massed for the purpose of driving our force into the river, and making another Ball’s bluff affair– but were foiled in their murderous attempt. The 1st brigade, 4th division of the 5th corps, were thrown out as skirmishers, and moved forward through the woods until they met the enemy, who drove them back through the woods. Meanwhile, the 2d brigade, commanded by Col. Hoffman of the 56th Pa. Vols., were drawn up in line of battle about a hundred yards from the woods, the line running parallel with the woods. This brigade was assisted by Battery H, 1st N.Y. Artillery. On the enemy emerging from the woods about twenty yards, Col. Hoffman gave the order to fire; at the same time the artillery worked their guns handsomely, pouring into the enemy a deadly fire of grape and cannister. This engagement was hotly contested for about thirty minutes, when the enemy was compelled to fall back; at the same time an aid rode forward and notified Col. Hoffman that the enemy were endeavoring to flank him on his right. He immediately changed direction of his brigade to the right, at the same time firing, and moved forward in line of battle, steadily driving the enemy before him over half a mile, in the direction of the Virginia Central Railroad, until darkness settling in, he was ordered to halt, by Major-Gen. Warren, and throw up breastworks– Major-Gen. laying out the breastworks in person. Much credit is due Col. Hoffman for the gallant manner in which he manoeuvred his brigade on this occasion. Owing to his tact and skill, he was the means of saving the day and preserving many a life. His brigade is composed of the following regiments:- 56th Pa. Vols., 147th N.Y.V., 76th N.Y.V., and 95th N.Y.V. In this action, this brigade captured 370 prisoners, principally South Carolina troops.

On the 24th, the Second Corps, under command of Major General Hancock, crossed at Island Ford; and the Sixth Corps, commanded by Gen. Wright, crossed at this point, and moved down the river about a mile and a half to the left, where the army head quarters were established.

On the 25th, the Fifth Corps moved to the left wing of the army, about four miles down the river, and threw up two lines of breastworks.

On the 26th and 27th, heavy skirmishing continued along the lines. The 2d brigade, 4th division of the 5th corps, lost 35 men while skirmishing. We recrossed the river on the night of the 27th, about 11 P.M., and marched north-east about four miles, where we received three days’ rations. We marched from there for the Pamunky River. On the 20th, we crossed the Pamunky River; and on the morning of the 30th, we moved forward, passing the 6th and 9th corps, where they were well entrenched in breastworks. About 4 P.M., we bivouacked in a field about a hundred yards from the resting place of the celebrated patriot, Patrick Henry [this would seem to be an error]. Next day, the 31st, our brigade was reinforced by two regiments, the 46th N.Y. and 3d Del. Towards evening, orders came for the 2d brigade to move forward and relieve Gen. Lockwood’s brigade, which was exhausted, having been under fire from 11 A.M. until 4 1/2 P.M. It was then ordered that a heavy line of skirmishers of 140 men and 3 commissioned officers, detailed from the different regiments of the 2d brigade, should move forward and relieve the skirmishers of Gen. Lockwood, which was done in a gallant and skillful manner by Capt. Dempsey, 147th N.Y., commanding the entire skirmishing party. I would say that much credit is due Captain Dempsey for the brave manner in which he advanced his skirmish line on this occasion. His cool, brave manner is proof of his good soldierly qualities. The casualties were very light, losing only two men, by being wounded, on his whole skirmish line, while we took upwards of 200 prisoners from some of the crack regiments of Virginia. The enemy perceiving what sad havoc our skirmish line had made among them, opened upon them with grape and shell, at the same time sending a very heavy skirmish line forward for the purpose of dislodging our skirmishers; but Capt. Dempsey having received orders from Major-Gen. Warren to hold the left of the skirmish line at all hazards, directed his men to fire on the enemy’s advancing line, which they did, killing and wounding 37 and taking 9 more prisoners. The enemy’s skirmishers, in falling back, had to abandon their arms and equipments in order to save their lives. That night our skirmish line advanced and threw up breast works about fifty yards from the enemy. Next morning the enemy fell back towards Mechanicsville, and our whole army moved forward and entrenched themselves, where there were two days heavy fighting on our right and left, Our left extended to Coal Harbor, where the Second Corps fought splendidly. Yours,

TOM.

The pontoon bridge across the North Anna at Jericho Mills, where the 5th Corps crossed on 23rd May. Taken by Irish photographer Timothy O’Sullivan (Library of Congress)

The last letter in the sequence carries the campaign from Cold Harbor to Petersburg on 19th June. It was published on 9th July:

LETTER FROM THE 147TH N.Y. VOl. RIFLES.

BIVOUAC NEAR PETERSBURG,

June 24th, 1864.

Dear Brother– Nothing of any importance has transpired since I last wrote, with the exception of leaving the Chickahominy and going towards Petersburg.

June 15th. In my last letter I mentioned the death of Col. Miller; but to-day I am happy to announce the glad tidings received in camp of the existence of our gallant Colonel.

Junr 16th. We embarked on board transports at Wilcox’s Landing, and crossed the James River about half-past 10 o’clock, a.m.; we then halted until about 2 p.m., when we again took up our route, marching steady all that day and night, until about 3, a.m., when we rested for the night.

June 17th. About 6, a.m., our Regiment (the 147th N.Y.) were sent on picket guarding the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad. At 4, p.m., we were relieved and drawn in; we were then drawn up in line of battle, and commenced throwing up breastworks, where we remained quiet all night.

June 18th. The next morning we advanced our lines over the two outer lines of the enemy’s works surrounding Petersburg, which they had evacuated during the night. We continued advancing through a piece of woods, crossing the railroad, and coming out into an open clearing. Here we were met by shot and shell from the enemy, decimating our ranks fearfully, and compelling us to move by the right flank, which gave us a slight protection from so deadly a fire. Here we lay still for half-an-hour, when we were ordered to fix bayonets, move forward, and take the line of works that the enemy then occupied, and from which they were continually firing on our lines. This was about half-past 2, p.m. The ground over which our men had to advance deserved notice, as we were in such a position while charging, that the enemy had the decided advantage of keeping our men in view, and continually pouring volley after volley of musketry, together with shell, grape and canister, which proved very destructive to our ranks. The sight was indeed heart-rending, to see so many brave fellows fall; yet, regardless of the danger of those terrible missiles, we continued moving forward, all the time closing up the vacancy made by the fall of our comrades, until we cam to within about one hundred yards of the enemy’s works, when our ranks becoming so thinned, and the fire of the enemy so destructive, the line was compelled to fall back, with the exception of a part of our Regiment, who, fortunately, were a little in the advance, and partly under cover of a small knoll. Seeing that this would give us a slight protection, and also perceiving the terrible slaughter the enemy were making on our men while falling back, we were ordered to lie down. As this afforded us but a partial protection from the fire of the enemy, it was surprising to see the men lower themselves into the earth by means of natural entrenching tools, in the shape of their hands and feet. Meantime our men, while lying in this position, were suffering profusely from the intense heat of the sun. Here we had a clear view of the field of battle in our rear. The ground was literally strewn with our dead and wounded, and to make the picture more striking, every now and then a few, not believing themselves secure enough, and endeavoring to secure for themselves a more safe position, would be seen to rise, but only to meet the fate of their fallen comrades. It was most distressing, indeed, to hear the groans of our dying comrades, crying for help, which it was not in our power to give them. Their cries were most agonizing. After lying in this position for nearly an hour, awaiting with great anxiety the darkness of the coming night, the enemy perceiving our situation, determined on capturing a few “live Yankees;” but in this attempt they were foiled, for our men, perceiving their intention, immediately poured a few volleys into their advancing columns, compelling them to fall back into their works. We then remained quiet, until about 9 p.m., when we fell back under cover of the night, and after partaking of a small collation of “coffee and hard tack,” which the boys were greatly in need of, as they had no opportunity to eat since the night before, we advanced up to within about two hundred yards of the enemy’s works, where we immediately intrenched ourselves, and how hold possession. This charge was the greatest that our Brigade ever participated in during the present campaign, and was led, in gallant style, by Col. Hoffman, of the 56th Pa. Vols., commanding the Brigade (2d). He is an able and efficient officer. The casualties in our Regiment were very heavy. Our Brigade (the 2d) sustained a very severe loss.

June 19th, and up to the present date, being the 24th, we still continue to occupy the same position. Our men are in a very perilous situation, not being able to leave their rifle pits through the day, except at the risk of their lives. We are continually firing out of the pits at each other. On the 19th, our flag was completely riddle with bullets, having no less than sixty-five bullet holes through it. From the 19th up to the present date, from the effects of firing out of the pits, we have lost as many men, on an average daily, as we did during the recent battles. The men are obliged to do their cooking, draw rations, & c. during the night. Much credit is due to the officers and members of the 147th N.Y. Vols. for the gallant way in which they conducted themselves on this occasion. The men are in good spirits, and feel confident of success.

TOM.

Co. K, 147th N.Y. Vols., 2d Brig., 4th Div., 5th Corps

Sergeant Alfred Stratton of the 147th New York was one of the men of Thomas’s regiment wounded in the 18th June assault at Petersburg, losing both his arms (Library of Congress)

References & Further Reading

1860 U.S. Federal Census.

Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts of New York State Volunteers, United States Sharpshooters, and United States Colored Troops [ca. 1861-1900]. (microfilm, 1185 rolls). Albany, New York: New York State Archives.

New York Adjutant General. Roster of the 147th New York Infantry.

New York Irish American Weekly 11th June 1864. Twelve Days Fighting. From The Wilderness to Laurel Hill.

New York Irish American Weekly 2nd July 1864. The Virginia Campaign.

New York Irish American Weekly 9th July 1864. The Virginia Campaign.

Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Richmond National Battlefield Park.

Petersburg National Battlefield.

The Siege of Petersburg Online.

Filed under: Battle of Cold Harbor, Battle of North Anna, Battle of Petersburg, Battle of Spotsylvania, Battle of The Wilderness Tagged: 147th New York Infantry, Eye Witness Accounts, Irish American Civil War, Irish American Military, New York Irish American Weekly, Overland Campaign Account, Second Battle of Petersburg, Soldiers Letters Home

February 5, 2016

“The Blacks Fought Like Hell”: Racism & Racist Violence in the Words & Actions of Two Union Irish Cavalrymen

This month is Black History Month in the United States. To mark that occasion, I wanted to once again explore an aspect of the often-fraught relationship between Irish-Americans and African-Americans during the Civil War era. It is a topic we return to regularly on the site (e.g. see here, here, here and here). The concept for this post arose from a recent discovery I made during my work on the letters of Irish soldiers contained within the Widows & Dependents Pension Files. Among the correspondence I identified was that of a Limerick man in the 10th Illinois Cavalry, which vividly demonstrate his views on African-Americans soldiers both before and after the 1863 Battle of Milliken’s Bend, in which black troops participated. Any examination of the 10th Illinois Cavalry quickly highlights the racial-conflict that occurred during the unit’s stationing at Milliken’s Bend. One particularly unsavory violent rampage by a soldier of the regiment stands out in the historic analysis; it was perpetrated by another Irishman, John O’Brien from Co. Cork. In an effort to explore, and begin to assess, the potential origins of his aggressive attitude towards African-Americans, I decided to examine his background, his emigration and his ante-bellum experiences to see what questions it might raise about his subsequent actions. It should be noted that this post contains unfiltered contemporary quotations that contain extremely racist language and sentiments, which may cause offense to some readers.

African-American troops in action at Milliken’s Bend, 1863 (Theodore Davis)

On 19th February 1863, 23-year-old Private Dan Dillon, from Ballyegran, Co. Limerick, wrote home to his mother. Dan was then serving in Company D of the 10th Illinois Cavalry, and was growing increasingly frustrated at the irregularity of his pay. In venting his frustration, he also offered his opinion regarding emancipation, and the prospect that he and his comrades might soon have to fight beside African-American soldiers:

Dear mother I mane to in form you that the war will be soon be at an end and we will all have a chance to go home without deserting the[y] ar[e] only giving us 2 months pay insted of 8 months and the cry is amongh the troops down here that if the[y] dont pay us more regular than what the[y] are the[y] will lay there arms down and left the damned abelinesets [abolitionists] and nigers fight themselves and see what the[y] can do there is great dissatifaction among the troops here for the half of them wont fight to free negroes nor fight with them if ever the[y] put a negro in the field with our armey every Black son of a Bich of them will get killed as soon & sure as the[y] come there sow the[y] stand a poor shoe [chance?] if ever the[y] get among the illinoise Boys of there lives (1)

Dan Dillon left little room for doubt about his views. His was an opinion shared by large numbers of Union troops, and by large numbers of Irish emigrants. Many, if not most, of the men in the 10th Illinois Cavalry would have agreed with him. Indeed, the unit itself developed something of a reputation with respect to their attitudes towards African-Americans, feelings which became heightened when elements of the regiment were stationed at Milliken’s Bend in Louisiana. In May 1863, during Grant’s Vicksburg campaign, it was decided that an “African Brigade” was to be formed there, largely drawn from former slaves who occupied the contraband camps located at the post. Already there had been problems between the white troops quartered there and the African-Americans; the latter, living in awful conditions, were regularly subjected to abuse- both physical and verbal- from the Union troops, many of whom were described as having “vicious and degraded” attitudes towards the former slaves. While the majority of white soldiers eventually moved on towards Vicksburg, the men of the 10th Illinois Cavalry stayed at Milliken’s Bend. Apparently many of them voiced their displeasure at appearing to form part of the “Negro Brigade.” A major incident seemed almost inevitable, and when it occurred, it was an Irishman of the 10th Illinois who was at its centre. (2)

On Saturday, 30th May 1863, two troopers of the 10th Illinois Cavalry drank themselves into a near stupor in one of the sutler’s tents. When they had their fill they stumbled out into the afternoon sun and made their way towards the area where the African-Americans were camped. Passing through the base of the newly formed 1st Mississippi Volunteer Infantry (African Descent), they came across Private Henry Lee of that regiment, who had been tied to a tree as punishment for a misdemeanour. Shouting “what is this damned nigger doing tied up here”, one of the men successfully landed a kick in the prisoner’s stomach. The two then staggered on towards a shack, where Lizzie Briggs and her 10-year-old daughter were staying with another freedwoman and a boy of around twelve or fourteen. Upon entering the hut, one of the soldier’s tried to lead the young girl away, but was so weakened by his drunken state that he was unable to wrest the girl from Lizzie’s grip. He apparently then picked up a hatchet, roaring “You damned niggers think you are free, and you are not as well off as you were with the Secesh! If you say a word I’ll mash your damned mouth!”. Turning next on the boy, the men rained down kicks on him, with the main instigator going so far as to grind his heel into the child’s eye, destroying it. The two then focused on the other woman occupying the shack; they attempted to strip her clothes away and rape her, but she successfully escaped. The savage rampage only came to an end when help was fetched, and an officer of the 57th Ohio succeeded in arresting one of the men. His name was John O’Brien. (3)

The Meeting of Friends. Caricature depicting Governor Horatio Seymour and Irish Draft Rioters in New York in 1863, with an African-American being lynched in the background (Library of Congress)

Allegedly John O’Brien had been the chief perpetrator; it was supposedly him who had tried to lead the girl away, and him who had assaulted the young boy. The incident gained notoriety not for his actions, but for those of Colonel Isaac Shepard, the abolitionist officer who was responsible for the recruitment of the 1st Mississippi (African Descent). Sickened by the constant assaults on the African-Americans for whom he was responsible, Shepard decided to make an example of O’Brien. He had the man restrained, and ordered a number of black soldiers to whip him with some berry bush branches. By all accounts the injuries inflicted on the Irishman was not serious- rather Shepard had wanted to make an example of him. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the realities of race relations in 1863, the case became potentially incendiary not because of O’Brien’s shocking actions, but due to the punishment meted out on him- having a white man whipped by black soldiers. An Inquiry resulted, and was out of necessity closely followed by Ulysses S. Grant. Although Shepard was cleared, it was felt necessary to avoid publication of the details, lest both white and black troops become incensed. Indeed, no further actions appear to have been taken against O’Brien. It is not the focus of this post to explore the inquiry or its fallout; those interesting in learning more can check out the Further Reading section below. Rather, I want to focus specifically on John O’Brien, the man who carried out the brutal assault. What can we learn of his background and history, and what questions, if any, do they raise for us when seeking to gain a better understanding of Irish racism towards African-Americans in the 1860s? (4)

Only one soldier served in the 10th Illinois Cavalry under the name John O’Brien. The Illinois Muster Roll Database records that he initially enlisted aged 22 in Springfield, Illinois in October 1861. An Irish-born farmer, he first mustered into Company F, but was transferred to Company A in January 1862. The Milliken’s Bend affair did not prevent him from staying on in the army; he re-enlisted as a veteran volunteer in January 1864 and served through to the war’s conclusion. Following the war the soldier went to live in Ballston Spa, New York. There he settled down, married and had a family. He and his wife Bridget would eventually have five children, Edward, William, Lizzie, August and John. The 1890 Veterans Schedule confirms his service as a private in Company A of the 10th Illinois Cavalry from June 1861 to April 1865, and his residency in Ballston Spa. By 1930 the widower was living with his daughter Lizzie; the old veteran eventually passed away on 3rd December 1930. However, it is in John O’Brien’s ante-bellum experiences that we are most interested here, and for that we must turn to his pension file, revealing some of the story of his life prior to the service which brought him to Milliken’s Bend in 1863. (5)